Abstract

In Ethiopia, the reduction in perinatal mortality rates is still falling short of national and global targets set for 2030. Additionally, accurate recording is challenging, as many births occur at home. This study aimed to assess the trends and determinants of perinatal mortality using population-based longitudinal data from 2009 to 2016 across three Health and Demographic Surveillance Systems (HDSS) in Ethiopia: Gelgel-Gibe, Dabat, and Kilite-Awlaelo. Data on vital events and pregnancies were continuously collected at these HDSS sites. The study utilized follow-up data from prospective linked pregnancy and birth cohorts from January 2009 to December 31, 2016. Perinatal mortality was defined as deaths occurring from 28 weeks of gestation until six days after birth, measured per 1000 live births. Relevant health, demographic, and socioeconomic data were included in the analysis. Poisson regression was employed to assess factors associated with perinatal mortality. Out of 38,691 pregnancies that led to births, there were 1214 perinatal deaths (456 stillbirths and 758 early neonatal deaths), resulting in a perinatal mortality rate of 31 deaths per 1000 total births. The early neonatal death rate was higher, at 19.6 deaths per 1000 total births, compared to the stillbirth rate of 11.8 per 1000 total births. The perinatal mortality rate declined from 40.6 in 2009 to 29.1 per 1000 total births in 2016, reflecting an average annual rate reduction of 2.4%. Determinants of perinatal mortality included being a male newborn, multiple births, first-time pregnancies (primi-gravidity), lack of antenatal care visits, absence of delivery services, and residing in tropical zones. The primary causes of death were asphyxia, sepsis, and preterm birth. Overall, perinatal mortality rates were high in the three HDSS sites, with slow reductions over time and significant variations between them. Addressing the issue of stillbirths and improving the availability and quality of emergency obstetric care are crucial. Continuous home visits in rural communities to prevent stillbirths and newborn deaths, are also essential.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Perinatal mortality is typically defined and measured in developing countries as occurring death at or after 28 weeks gestation, which includes stillbirths, as well as deaths within the first 6 days after birth referred to as early neonatal deaths1. This period is one of the most critical for the fetus, newborn, and mother. Globally, in 2022, there were 1.9 million stillbirths, and over 50% under-five died within the first week of life2, with a staggering 98% of these deaths occurring in low and middle-income countries (LMICs)1,2. Additionally, 45% of all stillbirths in 2022 occurred during labor and birth (intrapartum stillbirth)2.

Progress in global reduction efforts is slow, with significant under-reporting in LMICs due the lack of strong civil vital registration system. Between 1990 and 2021, the neonatal mortality rate decreased from 37 to 18 deaths per 1000 live births worldwide with the majority (47%) under-five deaths occurring during the neonatal period3. Sub-Saharan Africa is the most severely affected region, where 1 in 13 children die before their fifth birthday4, which is 14 times higher than in high-income countries and it accounts for 65% of global under-five deaths. Inequities in perinatal mortality rates continue to exist among regions and countries, particularly in developing nations2.

Many stillbirths and early neonatal deaths go unreported in most LMICs. Reports indicated that a significant number of stillbirths and more than half of all newborn deaths are not documented due to many deaths occurring at home and other reporting inaccuracies5. Consequently, the exact number and causes of newborn deaths remain unknown, hindering timely and effective actions to to prevent these fatalities. The WHO has initiated various programs, such as "Making Every Baby Count" and the integration of perinatal death surveillance into maternal death surveillance and response strategies2,5,6.

According to a systematic review of a study in 2020 in Ethiopia, the estimated perinatal mortality rate was 51 deaths per 1000 births, with stillbirth rate of 36.9 per 1000 births and an early neonatal mortality rate of 29.5 per 1000 live births7. The magnitude varies across different studies; for instance, Adebe et al. reported a perinatal death rate of 38 per 1000 births8. Most stillbirths and neonatal deaths are preventable. In Ethiopia, factors such as residence, economic status, educational status, age at first birth, and family size are associated with perinatal mortality8. In addition, the lack of maternal healthcare, inadequate care, and poor-quality healthcare during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postnatal periods significantly increase the risk for perinatal mortality, posing ongoing challenges in Ethiopia9,10.

The Ethiopian government has made reducing perinatal death a priority in its Health Sector Transformation Plan and Reproductive Health Strategy for 2016–202011. Additionally, it aimed to lower the neonatal mortality rate from 28 to 10 and the stillbirth rate from 18 to 10 per 1000 births by 2020, as outlined in its National Health Care Quality Strategy12. To address underreporting, Ethiopia revised its maternal death surveillance and response strategy in 2017 to include perinatal deaths13. However, many stillbirths remain unreported, rendering this issue largely invisible despite the significant number of deaths.

Perinatal mortality in Ethiopia remains one of the highest globally, with around 182,000 perinatal deaths reported13 and an average of 258 stillbirths occurring daily in 201514. Additionally, there were 99,000 neonatal deaths in 20183, though these figures were not consistently measured due to timing discrepancies. The Ethiopian DHS 2016 report indicated a perinatal mortality rate of 33 deaths per 1000 pregnancies, reflecting a decrease from 46 per 1000 total births in 20119,15. According to a 2015 UN estimate, Ethiopia experiences approximately 87,000 neonatal deaths and 97,000 stillbirths annually16,17. While Ethiopia has made progress in reducing neonatal mortality from 60 in 1990 to 29 in 20174, the rate slightly increased to 30 in 201910, indicating slow progress compared to 20119. The stillbirth rate remains high at 11.7 per 1000 pregnancies15, compounded by significant underreporting and inconsistent data. Furthermore, poor quality of maternal and newborn care has been identified as a key factor contributing to the elevated rates of stillbirths and neonatal deaths18,19.

Despite the challenges mentioned, there has been little focus on identifying the magnitude, trends, and causes of perinatal mortality in Ethiopia18. Additionally, reliable data on the perinatal period, stillbirths, and early neonatal deaths, particularly from community-based prospective studies, is limited. This study aims to assess the magnitude, trends, causes, and determinants of perinatal mortality across three Health and Demographic Surveillance System (HDSS) sites: Dabat, Kilite-Awlaelo, and Gelgel Gibe in Ethiopia. We utilized a DAG or causal framework for perinatal death, as detailed in the supporting information (Additional file 1).

Methods

Study setting and data source

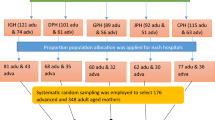

Data were collected from three Health and Demographic Surveillance System (HDSS) sites in Ethiopia: Gelgel-Gibe, Dabat, and Kilite-Awlaelo, all of which are part of the INDEPTH Network20. These HDSS sites represent three major regions of Ethiopia: Oromia, Amhara, and Tigray, located in the southwest, northeast, and northern parts of the country, respectively. They are among the six earliest established HDSS sites within the INDEPTH network in Ethiopia. Gelgel-Gibe HDSS was established in 2005, Dabat HDSS in 1996, and Kilite-Awlaelo HDSS in 2009. In total, the study included 34 Kebeles (the smallest administrative units in Ethiopia), with 10 in Kilite-Awlaelo, 13 in Dabat, and 11 in Gelgel-Gibe. Dabat and Kilite-Awlaelo each had one urban Kebele, while Gelgel-Gibe had three urban Kebeles, resulting in a total of five urban and 29 rural Kebeles. The baseline populations for these HDSS sites were 63,503 in Kilite-Awlaelo, 68,471 in Dabat, and 63,234 in Gelgel-Gibe21.

Study design

Longitudinal data were prospectively collected from the three HDSS databases between January 2009 and December 31, 2016. The study included a total of 38,691 pregnant women aged 15–49 years, from 28 weeks of gestation until six days post-birth, over the eight-year period. This comprised 38,148 singleton pregnancies and 543 multiple pregnancies. Pregnancies resulting in abortion were excluded from the study.

Follow up of study participants and data collection

Pregnant women in the surveillance area were identified and monitored for their pregnancy outcomes, including a follow-up within seven days after birth. Data on newborns, maternal characteristics, and household information were collected for every stillbirth and live birth at each HDSS site. Full-time Kebele-based data collectors continuously gathered this information. Deaths resulting from stillbirths and live births were recorded, and the probable causes of death were determined through reviews of the Verbal Autopsy (VA) by three physicians22. In cases of discrepancies among the reviews, a senior physician conducted an additional review following HDSS protocols. All HDSS utilized a standardized VA questionnaire adapted from WHO23 and the INDEPTH Network20. This study is based on eight years of follow-up data, from January 2009 to December 31, 2016, which is the most recent data available from the three HDSS sites.

Outcome measurements

Measurements related to perinatal death, stillbirth, and early neonatal death were based on WHO standards and ICD-10 criteria5,24. In this study, stillbirth was defined as a pregnancy that ended after 28 weeks with no signs of life, while early neonatal death was defined as the death of a baby within 6 days of birth. Perinatal death encompasses both stillbirths (loss occurring at ≥ 28 completed weeks of gestation) and early neonatal deaths (deaths of live births within the first 6 days of life (0–6 days)). The perinatal mortality rate was calculated as the number of perinatal deaths per 1000 total births5,24.

Data analysis

Data were checked for completeness, and any missing values were addressed before being cleaned and analyzed using STATA software version 14. Descriptive statistics, trend analysis, and rates per 1000 total births were calculated to estimate the magnitude and trends in perinatal mortality, stillbirth, and early neonatal death rates. The perinatal mortality rate, along with a 95% CI, was estimated based on the number of deaths per 1000 total births for each year, including all multiple births. Data from the three HDSS sites were merged after ensuring common variables and value levels across all sites. A new variable, "HDSS," was created to identify data from each HDSS site. The Average Annual Rate of Reduction (AARR) was calculated to quantify the change in perinatal mortality from the baseline year to the most recent year. The average annual percentage change in perinatal mortality was computed using the formula [(a/b)(1/r) − 1] × 10025 where 'a' represents the most recent (2016) perinatal mortality rate, 'b' represents the earliest (2009) perinatal mortality rate, and 'r' is the number of years—set to 7 for this analysis. Factors associated with perinatal mortality, along with a 95% CI, were estimated using the Poisson regression model.

Result

Characteristics of the deaths in HDSS

In this study, a total of 38,691 pregnancies were followed until seven days post-birth across the three HDSS sites in Ethiopia, comprising 38,148 singleton pregnancies and 543 multiple pregnancies. Specifically, 11,465 pregnancies were from Dabat HDSS, 16,768 from Gelgel Gibe, and 10,458 from Kilite-Awlaelo HDSS. Over the eight-year period from 2009 to 2016, there were a total of 1214 perinatal deaths, including 456 stillbirths and 758 early neonatal deaths. The breakdown of deaths was 230 in Dabat HDSS, 705 in Gelgel-Gibe, and 279 in Kilite-Awlaelo.

More than one-fourth of the mothers were aged between 25 and 29 years. The majority of mothers (80.9%) resided in rural areas, and most (62.1%) gave birth at home. There was variation in the rates of home births versus health facility births across the three HDSS sites: 45.4% of mothers in Gelgel-Gibe gave birth at home, compared to 36.2% in Dabat and 18.4% in Kilite-Awlaelo (Table 1).

Perinatal mortality rate (stillbirth and early neonatal death)

In this study, the perinatal mortality rate was 31 deaths per 1000 total births, with the early neonatal death rate being the highest at 19.6 early neonatal deaths per 1000 total births per year. The highest perinatal mortality rate was recorded in Gelgel Gibe HDSS, at 42 perinatal deaths per 1000 total births per year (Table 2).

Trend of perinatal mortality in three HDSS sites

The overall trend of perinatal mortality across the three HDSS sites indicate a reduction overtime, decreasing from 40.6 deaths per 1000 total births in 2009 to 29 deaths per 1000 total births in 2016. The average annual rate of reduction during this period was 2.4% (Table 3). However, the rate of perinatal deaths remains high and inconsistent in its reduction over time, which may be related to data quality issues within the HDSS. From 2009 to 2011, there was a notable decline in perinatal mortality rates across nearly all HDSS sites, falling from 40 to 30 deaths per 1000 total births. However, an upward trend was observed starting in 2011, peaking in 2012 across most HDSS sites. After 2014, the perinatal mortality rate slowly decreased from 31 deaths per 1000 total births in 2014 to 29 deaths per 1000 total births in 2016 (Fig. 1).

The early neonatal death rate was higher than the stillbirth rate. The trend for stillbirth rates did not indicate a rapid reduction across the three HDSS sites. After 2014, the stillbirth rate began to trend upward (Fig. 2).

Perinatal mortality by sex

The perinatal mortality rate was higher among male newborns, at 23.6 deaths per 1000 live births, excluding stillbirths, as data on stillbirth sex are not consistently reported across all HDSS sites in Ethiopia. The highest rate was observed in Gelgel Gibe HDSS, at 30.7 deaths per 1000 live births. There was a significant increase in the mortality rate for male newborns between 2011 and 2013, followed by a notable reduction after 2014. While the overall trend in perinatal mortality decreased for both sexes since 2009, there was an increase in the rate for female newborns from 2015 to 2016 (Additional file 2).

Trend of stillbirth rate in three HDSS sites

The overall rate of stillbirths across the three HDSS sites was 11.8 stillbirths per 1000 total births per year. From 2009 to 2016, the average annual rate of reduction in stillbirths did not show improvement; instead, it increased by 10.6%. The highest stillbirth rate was recorded in Gelgel Gibe (16.5 per 1000), followed by Kilte-Awlaelo (14.7 per 1000) and Dabat (3.1 per 1000). While the trend in stillbirth rates showed a reduction over time, it peaked in 2016 at 14.8 per 1000. However, stillbirth rates continued to rise in Kilite-Awlaelo and Gelgel Gibe HDSS from 2015 to 2016. Notably, there were no reports of stillbirths from Dabat HDSS between 2009 and 2012 (Fig. 3).

Trend of early neonatal death rate in three HDSS sites

The overall rate of early neonatal death across the three HDSS sites was 19.6 deaths per 1000 total births per year. From 2009 to 2016, the average annual reduction in early neonatal mortality was 9.4%. The highest rates were found in Gelgel Gibe (25.5 per 1000), followed by Dabat (16.9 per 1000) and Kilteawlaelo (13 per 1000). While the trend in early neonatal death rates showed a decrease over time, peaking in 2013 at 23.1 per 1000, the rate continued to rise in Dabat HDSS from 2014 to 2016 (Fig. 4).

Causes of perinatal mortality in three HDSS

Regarding the causes of perinatal mortality, those requiring emergency care ranged from 3.5 to 5.3 deaths per 1000 total births across the three HDSS sites. Causes requiring primary care ranged from 2.7 to 3.8 deaths per 1000 total births. Major causes under emergency care included stillbirth, pregnancy and delivery-related asphyxia, sepsis, preterm birth, meningitis, and tetanus. In contrast, causes that necessitate primary care included pneumonia, diarrhea, malnutrition, measles, and cardiac issues (Table 4).

Factor associated with perinatal mortality in three HDSS of Ethiopia

Mothers aged 20–24 years had a 19% lower risk of perinatal death compared to those under 20. Perinatal death rates were 33.7% higher among the Tigrei ethnic group and twice as high among the Oromo and other groups (Gurage, Dawro, and Yem) compared to the Amhara ethnic group. Single mothers faced a 57% higher rate of perinatal death compared to married mothers. Employed mothers experienced 71.3% fewer perinatal deaths than housewives.

In terms of birth location, the rate of perinatal death increased by 85% for mothers who gave birth in communities other than at home or in health facilities. The risk of perinatal death rose by 40% when births were attended by unskilled personnel compared to those assisted by skilled birth attendants. Multi-parous mothers experienced 11.2% fewer perinatal deaths than first-time mothers. Male newborns were at a 47% higher risk of perinatal mortality compared to female newborns. Mothers with triplet or higher pregnancies faced an eightfold increase in the risk of perinatal death compared to those with singleton pregnancies.

The rate of perinatal mortality was 30% lower for mothers living in urban areas compared to those in rural areas. Perinatal death rates were twice as high in Gelgel Gibe and 33% higher in Kilite-Awlaelo compared to Dabat HDSS. Mothers residing in cooler zones experienced 22.6% fewer perinatal deaths than those living in tropical zones. Giving birth at primary health care units (health centers, health posts, and private clinics) was associated with lower perinatal death rates compared to hospitals. The higher mortality rates in hospitals may be attributed to the referral of high-risk mothers and newborns during delivery (Table 5).

Discussion

This study aimed to assess the magnitude, trends, and causes of perinatal mortality in three HDSS sites in Ethiopia over an eight-year period. We found that the perinatal mortality rate was 31 deaths per 1000 total births per year. The rate decreased from 40.6 to 29 deaths per 1000 total births across all HDSS sites over this period. However, in Kilite-Awlaelo, the perinatal mortality increased from 10 deaths per 1000 total births in 2009 to 29 in 2016. Major causes requiring emergency care included stillbirths, premature births, and asphyxia. Determinants of perinatal mortality in Ethiopia included being a male newborn, having multiple births, being a first-time mother, giving birth at home with non-professionals, being single or a housewife, and residing in rural or tropical areas.

Despite some progress in obstetric care, conflict regions in Ethiopia, particularly Tigray, Amhara, Oromia, and Gambela, continue to face significant challenges due to ongoing conflicts lasting over three years26.

The perinatal death rate in this study aligns with the 2016 Ethiopian DHS report, which recorded 33 deaths per 1000 births15. However, our findings are higher than those from studies in Amhara (25 per 1000 births)27, Oromia28, and the 2019 mini-EDHS report (38 per 1000)8 as well as a study in Haramaya (26 per 1000)29. There were inconsistencies in the reduction of perinatal mortality among the three study locations. Gelgel-Gibe HDSS reported a perinatal mortality rate of 42 deaths per 1000 births, while Dabat and Kilite-Awlaelo reported rates of 20 and 26 per 1000 births, respectively. The differences observed between the Oromia study and our findings could stem from the nature of HDSS compared to community-based surveys28, where the likelihood of missed deaths is lower in HDSS. This suggests a high perinatal mortality rate in the Oromia region, consistent with the 2011 Ethiopia DHS report, which indicated 45 deaths per 1000 total births9. Contributing factors may include a higher fertility rate and cultural practices surrounding childbirth in the Oromia region8,9.

In this study, the perinatal mortality rate was lower than in hospital-based studies conducted in Oromia (130 deaths per 1000 total births30 and Hawassa (85 deaths per 1000 total births)31. This lower rate may be attributed to the high number of home deliveries, which increases the denominator and thereby reduces the perinatal mortality rate compared to institutional deliveries. In hospitals, complications from lower-level health facilities can lead to a higher number of deaths (numerator) in relation to total live births (denominator). Consequently, mortality rates in hospitals may be elevated because women often choose to give birth at home or in nearby health centers when complications are absent. Additionally, the higher rates in hospitals may reflect lower-quality maternal health services and the lack of neonatal intensive care units in most facilities in Ethiopia11,18.

The current study revealed a slower reduction in perinatal mortality rates, with inconsistencies across different HDSS sites and ethnic groups. Further research is needed to explore these inconsistencies. This finding aligns with previous studies in Ethiopia that indicated a lack of significant reduction in perinatal mortality32. Improvements in reporting and detecting perinatal deaths, particularly through the maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response program13, may contribute to the observed increase in the absolute number of deaths. It is crucial to continue monitoring these rates, as increased awareness and cultural shifts regarding the reporting of stillbirths and early neonatal deaths are essential. Health education initiatives involving health extension workers, as well as media campaigns through TV and radio, can enhance community awareness. Strengthening the vital registration system in Ethiopia and improving the reporting and detection of perinatal deaths could help to better understand the true magnitude of this issue and inform future interventions.

We found an average annual reduction rate of 2.4% in perinatal mortality from 2009 to 2016. This aligns with the global average annual reduction in neonatal mortality, which was 2.6% from 1990 to 20183. However, this finding is lower than the 4.6% average annual reduction rate for under-five mortality in Ethiopia during the same period3. The discrepancy may be attributed to the different types of mortality involved. While Ethiopia has met its Millennium Development Goal of reducing under-five mortality by two-thirds, it continues to lag in decreasing perinatal, stillbirth, and neonatal mortality rates.

In this study, the total stillbirth rate across the three HDSS sites was 11.8 per 1000 total births, slightly higher than the 9.5 per 1000 reported in six HDSS sites in 2014 (9.5 per 1000 births)18. However, it is lower than rates found in other Ethiopian studies, such as 25.5 per 1000 deliveries)33, a systematic review reporting rates between 60 and 110 per 1000 births32, and a 2015 Lancet study that reported 30 per 1000 total births)11 and a study in Northwest Ethiopia (23.4 per 1000 births)34. Differences in methodology between community-based surveys and HDSS may account for these variations. Additionally, misclassification of stillbirths and early neonatal deaths is common in Ethiopia, as healthcare providers often report early neonatal13 deaths instead of stillbirths. This is because neonatal mortality is a reportable indicator in health facility surveillance, while stillbirths are not11. Consequently, some providers may categorize early neonatal deaths as stillbirths to lessen accountability.

The early neonatal death rate in this study was notably high at 19.6 per 1000 total births per year, consistent with findings from a systematic review in Ethiopia that reported rates between 20 and 34 per 1000 births. However, this rate is higher than the 16.2 per 1000 reported in six HDSS sites in 2014 (16.2 per 1000 births)33. In our findings, the early neonatal death rate surpassed the stillbirth rate, which is supported by the earlier report from six HDSS sites. Our results are also lower than those from a study in Northwest Ethiopia, where the early neonatal death rate was 27.5 per 1000 live births34. These differences may arise from the characteristics of community-based surveys versus HDSS, along with coverage limitations in community surveys that may exclude some live births.

In this study, the main causes of perinatal deaths requiring emergency care were stillbirths, premature births, and birth asphyxia. These findings align with other studies conducted in Ethiopia28,35. This underscores the poor quality of maternal and newborn care in the country. Many premature infants do not receive specialized care, such as kangaroo mother care, and numerous healthcare professionals lack the skills needed to effectively resuscitate asphyxiated newborns. The Federal Ministry of Health of Ethiopia is currently enhancing the training of mid-level health professionals in neonatal nursing, which may help reduce deaths from asphyxia, prematurity, and sepsis. However, it will take time to observe the full impact of this program, particularly at the lower levels of health facilities.

The following limitations should be considered when interpreting the results of this study. In most electronic datasets within the HDSS, the cause of death is often recorded as "other," which presents a limitation. Additionally, the Dabat HDSS site did not report stillbirths from 2009 to 2012, potentially underestimating the stillbirth rate. This lack of reporting may also affect the overall assessment of perinatal mortality in our analysis. Furthermore, the Dabat HDSS site did not provide information on the causes of early neonatal deaths, such as prematurity, complications related to pregnancy or delivery (asphyxia and sepsis), and conditions like tetanus and meningitis occurring within the first week of life. Across all HDSS sites, there were gaps in data for important demographic variables, such as antenatal care visits, highlighting the need for improved data handling and quality assurance in the HDSS in Ethiopia.

The sex of all stillbirths and the causes of stillbirths are not recorded consistently across all HDSS sites. Misclassification between stillbirths and early neonatal deaths may impact the reported figures for both categories in this study. However, this should not affect the overall perinatal mortality rate, as these cases will be counted as either stillbirths or early neonatal deaths. Verbal autopsy (VA) data in the HDSS are recorded separately and have not been integrated into the current HDSS program, complicating data incorporation due to differing identification systems. While each HDSS site attempts to update causes of death data from VA, there are instances where updates are not made due to the existence of two separate systems. Consequently, many causes of death have been categorized as “other” across all HDSS sites. Therefore, we have reported only those causes of death that are included in the HDSS records.

To ensure accuracy, it is essential to link data of verbal autopsy (VA) in the HDSS program software across all sites without delay. The socio-demographic characteristics of the HDSS population have not been consistently updated every five years as per the HDSS schedule. This lack of regular updates may hinder our understanding of how socio-demographic and economic changes influence mortality rates over time. Each HDSS should prioritize updating the socio-demographic data, especially concerning mothers. Additionally, data quality in each HDSS is a concern due to software updates and changes in systems over time. Collaborative efforts are needed to integrate all HDSS sites in Ethiopia, working together to utilize standardized tools and approaches.

Conclusions

The perinatal mortality rate remains high and varies significantly across the three HDSS sites. Progress in reducing perinatal mortality has been slow over time. Major causes of perinatal deaths requiring emergency care include stillbirths, asphyxia, and prematurity, with early neonatal deaths occurring more frequently than stillbirths. There is an urgent need to improve the availability and quality of emergency maternity and newborn services. Factors associated with higher perinatal mortality include multiple pregnancies, male newborns, first-time mothers, births attended by non-health professionals, single motherhood, and residing in tropical zones. Enhanced care and support for cases of prematurity, asphyxia, and stillbirth are essential at health facilities. Implementing effective referral and transportation systems for complicated cases from communities to hospitals, utilizing could significantly reduce perinatal deaths in rural areas.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript. The authors will share raw datasets upon formal request to corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- AARR:

-

Average annual rate of reduction

- HDSS:

-

Health and demographic surveillance system

- VA:

-

Verbal autopsy

References

WHO. Maternal and perinatal health. https://web.archive.org/web/20131203064838/http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/topics/maternal/maternal_perinatal/en/ (Accessed 29 Feb 2024) (WHO, 2024).

IGME, UNICEF, WHO, WBG, UN. Never Forgotten: The situation of stillbirth around the globe: Report of the United Nations Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation, 2022 (United Nations Children’s Fund, 2023).

IGME, UNICEF, WHO, WBG, UN. Levels and Trends in Child Mortality: Report 2022. https://reliefweb.int/report/world/levels-trends-child-mortality-report-2022 (Accessed 20 Oct 2023) (United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), 2023, The World Bank. WHO, 2018).

UNICEF, WHO, WBG, UN. Levels & Trends in Child Mortality, Report 2018. https://www.unicef.org/publications/index_103264.html (Accessed 10 July 2020) (United Nations Children’s Fund).

WHO, Making every baby count: audit and review of stillbirths and neonatal deaths. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/mca-documents/maternal-nb/making-every-baby-count.pdf?Status=Master&sfvrsn=6936f980_2 (Accessed 08 Jan 2018) (WHO, 2016).

Ali, M. M., Bellizzi, S. & Boerma, T. Measuring stillbirth and perinatal mortality rates through household surveys: a population-based analysis using an integrated approach to data quality assessment and adjustment with 157 surveys from 53 countries. Lancet Glob. Health 11, e854–e861 (2023).

Jena, B. H., Biks, G. A., Gelaye, K. A. & Gete, Y. K. Magnitude and trend of perinatal mortality and its relationship with inter-pregnancy interval in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 20, 432. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-03089-2 (2020).

Adebe, K. L. et al. Analysis of regional heterogeneity and determinants of perinatal mortality in Ethiopia: review. Ann. Med. Surg. 85, 902–907 (2023).

Central Statistical Agency [Ethiopia] and ICF International. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey. 2012 https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR255/FR255.pdf (Central Statistical Agency and ICF International, 2011).

Ethiopian Public Health Institute (EPHI) [Ethiopia] and ICF. Ethiopia Mini Demographic and Health Survey 2019: Key Indicators. https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/PR120/PR120.pdf (Accessed 18 June 2020) (EPHI and ICF, 2019).

Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Health. Health Sector Transformation Plan (HSTP): 2015/16 - 2019/20. https://www.globalfinancingfacility.org/sites/gff_new/files/Ethiopia-health-system-transformation-plan.pdf (Accessed 10 Jan 2018) (Ministry of Health, 2015).

Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Health. Ethiopian National Health Care Quality Strategy: Transforming the Quality of Health Care in Ethiopia (2016 - 2020). https://www.academia.edu/35912047/ETHIOPIAN_NATIONAL_HEALTH_CARE_QUALITY_STRATEGY_Transforming_the_Quality_of_Health_Care_in_Ethiopia (Accessed 12 Sept 2018) (2016).

Ethiopian Public Health Institute (EPHI). National Technical Guidance for Maternal and Perinatal Death Surveillance and Response, 2017. https://www.ephi.gov.et/images/pictures/National-Maternal-and-Perinatal-Death-Surveillance-and-Response-guidance-2017.pdf (Accessed 15 Sept 2018) (EPHI).

Lawn, J. E. et al. Ending Preventable Stillbirths Series study group with The Lancet Stillbirth Epidemiology investigator group Stillbirths: rates, risk factors, and acceleration towards 2030. Lancet https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140 (2016).

Central Statistical Agency (CSA) [Ethiopia] and ICF. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2016: Key Indicators Report, 2016. https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR328/FR328.pdf (CSA and ICF).

Blencowe, H. et al. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of stillbirth rates in 2015, with trends from 2000: a systematic analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 4(2), e98-108. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00275-2 (2016).

You, D. et al. Global, regional, and national levels and trends in under-5 mortalities between 1990 and 2015, with scenario-based projections to 2030: a systematic analysis by the UN Inter-Agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation. Lancet 386(10010), 2275–2286. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00120-8 (2015).

Fisseha, G., Berhane, Y., Worku, A. & Terefe, W. Quality of the delivery services in health facilities in Northern Ethiopia. BMC Health Serv. Res. 17(187), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2125-3 (2017).

Save the Children. Ending newborn deaths. Ensuring every baby survives https://www.savethechildren.net/sites/default/files/libraries/ENDING-NEWBORN-DEATHS.pdf (Accessed 20 Feb 2020) (The Save the Children Fund, 2014).

INDEPTH Network, Member HDSSs: Member HDSSs in Africa. Available: http://www.indepth-network.org/member-centres (Accessed 23 Mar 2019).

Health and Demographic Surveillance System Ethiopian Universities Research Centers’ Network. Trends and Causes of Perinatal Death in Ethiopia, 2010–14, Policy Brief Number 2. https://www.healthynewbornnetwork.org/hnn-content/uploads/Policy-Brief-2-1.pdf (2016).

Weldearegawi, B. et al. Emerging chronic non-communicable diseases in rural communities of Northern Ethiopia: evidence using population-based verbal autopsy method in Kilite Awlaelo surveillance site. Health Policy Plan https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czs135 (2013).

WHO. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision (ICD-10) Version for 2010. http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd10/browse/2010/en (Accessed Mar 23, 2019) (2010).

Allanson, E. R. et al. The WHO application of ICD-10 to deaths during the perinatal period (ICD-PM): results from pilot database testing in South Africa and United Kingdom. BJOG 123(12), 2019–2028. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.14244 (2016).

Saleem, S. et al. Trends and determinants of stillbirth in developing countries: results from the Global Network’s Population-Based Birth Registry. Reprod. Health 15(Suppl 1), 100. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-018-0526-3 (2018).

Bendavid, E. et al. The effects of armed conflict on the health of women and children. Lancet 397(10273), 522–532. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00131-8 (2021).

Yirgu, R., Molla, M., Sibley, L. & Gebremariam, A. Perinatal mortality magnitude, determinants and causes in West Gojam: Population-based nested case-control study. PLoS ONE 11(7), e0159390. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0159390 (2016).

Roro, E. M., Sisay, M. M. & Sibley, L. M. Determinants of perinatal mortality among cohorts of pregnant women in three districts of North Showa zone, Oromia Region, Ethiopia: Community based nested case control study. BMC Public Health 18, 888. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5757-2.PMID:30021557.PMCID:PMC6052561 (2018).

Dheresa, M. et al. Perinatal mortality and its predictors in Kersa Health and Demographic Surveillance System, Eastern Ethiopia: population- based prospective study from 2015 to 2020. BMJ Open 12, e054975. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-054975 (2022).

Asheber, G. Perinatal mortality audit at Jimma Hospital, South- Western Ethiopia 1990–1999. Ethiop. J. Health Dev. 14(3), 335–343. https://doi.org/10.4314/ejhd.v14i3.9907 (2000).

Bayou, G. & Berhan, Y. Perinatal mortality and associated risk factors: a case control study. Ethiop. J. Health Sci. 22(3), 153–162 (2012).

Berhan, Y. & Berhan, A. Perinatal mortality trends in Ethiopia: Review. Ethiop. J. Health Sci. (Special Issue), 29–49 (2014).

Berhie, K. A. & Gebresilassie, H. G. Logistic regression analysis on the determinants of stillbirth in Ethiopia. Matern. Health Neonatol. Perinatol. 2, 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40748-016-0038-5 (2016).

Andargie, G., Berhane, Y., Worku, A. & Kebede, Y. Predictors of perinatal mortality in rural population of Northwest Ethiopia: a prospective longitudinal study. BMC Public Health 13, 168. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-168 (2013).

Mengesha, H. G. & Sahle, B. W. Cause of neonatal deaths in Northern Ethiopia: a prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health 17, 62. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3979-8 (2017).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Queen Elizabeth Advanced Scholars Program—Statistical Alliance for Vital Events (QES-SAVE) which was facilitated by the Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto for providing us with the necessary knowledge, skills, and opportunities through the different capacity-building trainings and continuous supervision program throughout the project. We would like to thank the staff of the University of Toronto, Dalla Lana School of Public Health, and the supervisors for guiding, sharing valuable literature, and library, office, and linking us to valuable materials. Finally, we would like to thank, Gelgelgibe, Kilite-Awlaelo, and Dabat HDSS sites for sharing the raw data, and continuous support from data managers.

Funding

No funding was received for this study. The QES scholarship on Statistical Alliance for Vital Events (Save) – Queen Elizabeth Advanced Scholars (QES), organized by Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto provide technical and transportation support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GFA, SF, and PB worked from the inception of the paper, prepared the proposal, designed the methods, participated in the data quality control, cleaned, and merged data, performed analysis and interpretation of the findings, and prepared the manuscript. EDR, FT, and TMY participate in method development and cleaning data, and analysis. GFA and SF prepared the draft manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Mekelle University, College of Health Sciences Institutional Review Board [ERC 1409/2018]. In addition, the proposal is submitted to each HDSS sites and approved. The board members in the three HDSS sites reviewed based on their data sharing policy of each HDSS sites and accepted accordingly. Informed consent was taken from the three HDSS to take the secondary data in accordance with the guidelines and regulations outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. All data were kept confidential and data containing personal identifiers of motherhood are not shared with third parties.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abreha, G.F., Fadel, S.A., Di Ruggiero, E. et al. Trends in perinatal mortality and its determinants in Ethiopia using longitudinal data from the demographic surveillance system (2009–2016). Sci Rep 15, 42573 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23731-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23731-3