Abstract

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) has been demonstrated to be associated with renal injury. However, the cellular and molecular mechanisms by which chronic intermittent hypoxia (CIH), a hallmark of OSA, contributes to renal injury remain poorly understood. Twelve male Sprague-Dawley rats were randomized into normoxic control (NC) and CIH groups (n = 6 each), with CIH exposure for 12 weeks. Renal injury was evaluated by Hematoxylin and Eosin staining and a modified Jablonski score. Single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) was performed. Data analysis included clustering of cells, differential gene expression analysis, and functional enrichment through Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways. Histopathological analysis revealed renal injury with renal tubular epithelial cell edema, necrosis in the CIH group compared to NC. A total of 42,581 cells (19,655 cells from NC group and 22,926 cells from CIH group) were retained after quality control, with 13 distinct renal cell populations identified. CIH exposure resulted in an increased proportion of podocytes, while mesangial cells were reduced compared to the NC group. CIH exposure altered the transcriptomic landscape, with differentially expressed genes (DEGs) observed across multiple cell types. Functional enrichment analysis indicated that CIH-induced DEGs were associated with suppressed metabolic and signaling pathways in proximal tubule and loop of Henle epithelial cells, activation of apoptotic and sodium reabsorption pathways in distal convoluted tubule cells, and enhanced inflammatory and phagocytic signaling in mononuclear phagocytes. Our study provides a high-resolution atlas of CIH-induced transcriptional changes in the rat kidney. The findings reveal cell type-specific responses and pathways potentially contributing to OSA-associated renal injury, offering novel insights into pathogenesis and potential therapeutic targets for preventing renal damage in OSA patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a prevalent sleep disorder characterized by recurrent episodes of complete or partial upper airway obstruction during sleep, leading to intermittent hypoxia (IH) and sleep fragmentation. OSA has been increasingly linked to systemic complications1,2,3, including kidney injury, particularly chronic kidney disease (CKD)4,5. Chronic intermittent hypoxia (CIH), a hallmark of OSA, is hypothesized to contribute to the development of CKD and other renal pathologies through multiple mechanisms, including oxidative stress, endothelial dysfunction, and hypoxemia-related activation of both the sympathetic nervous system and the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system6,7. Despite the growing recognition of OSA-associated renal damage, the precise cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying these effects remain poorly understood.

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) technology isolates individual cells from tissue or body fluid samples, captures their transcriptomic profiles through unbiased, high-throughput, and high-resolution sequencing, and enables comprehensive data analysis8. This powerful approach not only uncovers unique gene expression changes in individual cells but also facilitates the discovery of entirely novel cell types, signaling pathways, and molecular networks in both health and disease9. However, scRNA-seq requires the use of fresh tissue. Single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) can overcome these problems and represent an alternative to scRNA-seq10. snRNA-seq has emerged as a powerful tool for studying complex or difficult-to-dissociate tissues, including the kidney, by focusing on nuclear RNA11. scRNA-seq and snRNA-seq have been utilized across various species, including humans, animals, and plants, to enhance our understanding of both normal physiological processes and disease models12,13. The application of single-cell technologies in OSA research remains limited14.

In this study, we aim to employ snRNA-seq to elucidate the cellular and molecular responses of rat kidney to CIH. By characterizing the gene expression patterns of individual kidney cell types under CIH conditions, we seek to identify key pathways and cell populations involved in OSA-associated renal damage. Our findings will provide critical insights into the mechanisms of CIH-induced renal damage and may reveal potential therapeutic targets for mitigating kidney complications in OSA patients.

Methods

Animals and subgroups

12 male Sprague-Dawley rats, aged 8 weeks, were obtained from Fujian Medical University’s Laboratory Animal Center. Following one week of acclimatization under standard housing conditions (12:12 h light-dark cycle) with ad libitum access to food and water, the animals were randomly assigned to two experimental groups using a computer-generated randomization scheme: normoxic control group (NC, n = 6) and CIH group (CIH, n = 6). This study was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Fujian Medical University (IACUC FJMU 2022-0031). All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. All methods were also reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines.

IH exposure

Rats in the CIH group were exposed to IH for 12 weeks. The IH protocol was established based on previous study15. Each IH cycle consisted of four phases: (1) reducing oxygen concentration from 21% to 6% over 120 s, (2) maintaining hypoxia (6% O₂) for 30 s, (3) rapidly reoxygenating to 21% over the next 10 s, and (4) sustaining normoxia (21% O₂) for an additional 20 s. The CIH group underwent daily 8-hour IH exposure (08:00–16:00) during the light phase, while NC rats were maintained in room air under identical temporal conditions.

Hematoxylin–Eosin (HE) staining

All kidney specimens were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, followed by dehydration and paraffin embedding. Sections were hematoxylin-stained (20 min) followed by eosin-phloxine counterstaining. Furthermore, sections were mounted in xylene-based medium. Histopathological examination was performed under an Olympus BX50 light microscope (Tokyo, Japan) and evaluated independently by a single board-certified pathologist blinded to the experimental groups to ensure unbiased assessment. Renal injury was assessed using the modified Jablonski scale (0–5): 0 indicates normal renal cells; 1 represents degeneration and necrosis of individual cells; 2 denotes degeneration and necrosis affecting a single kidney tubule; 3 corresponds to degeneration and necrosis adjacent to the proximal convoluted tubule, with surviving cells surrounding the affected tubule; 4 signifies necrosis confined to one-third of the distal convoluted tubule, with a necrotic band extending into the inner cortex; and 5 indicates necrosis involving all segments of the proximal convoluted tubule16.

Nuclei isolation and sorting

Three renal tissue samples were randomly selected from each group using a computer-generated randomization scheme and subsequently subjected to sequencing. Renal tissues were harvested and washed in pre-cooled PBSE (PBS buffer containing 2 mM EGTA). Nuclei isolation was carried out using GEXSCOPE® Nucleus Separation Solution (Singleron Biotechnologies, Nanjing, China), according to the manufacturer’s product manual. Isolated nuclei were resuspended in PBSE to 106 nuclei per 400 µl, filtered through a 40 μm cell strainer, and counted with Trypan blue. To assess nuclei quality, the enriched nuclei were stained with DAPI (1:1,000) (Thermo Fisher Scientific). We used DAPI fluorescence to assess nuclear integrity, ensuring it was greater than 80%. We also confirmed that non-nuclear debris was less than 20% and the nuclei count for each sample exceeded 50,000 before proceeding. Nuclei were considered as DAPI-positive singlets.

SnRNA-seq library preparation

The concentration of single nucleus suspension was adjusted to 3–4 × 105 nuclei/mL in PBS. Single nucleus suspension was then loaded onto a microfluidic chip (GEXSCOPE® snRNA-seq Kit, Singleron Biotechnologies) and snRNA-seq libraries were constructed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Singleron Biotechnologies). The resulting snRNA-seq libraries were sequenced on an Illumina novaseq 6000 instrument with 150 bp paired end reads.

Primary analysis of raw read data

Raw reads were processed to generate gene expression profiles using CeleScope v2.0.7 (Singleron Biotechnologies) with default parameters. Briefly, Barcodes and UMIs were extracted from R1 reads and corrected. Adapter sequences and poly A tails were trimmed from R2 reads and the trimmed R2 reads were aligned against the mRatBN7.2 (rattus_enemebl_111) transcriptome using STARSolo in STAR (v2.7.11a). Key STARsolo parameters included --outFilterMatchNmin 50, while --outFilterMismatchNmax was left at its default value of 10. Successfully assigned reads with the same cell barcode, UMI and gene were grouped together to generate the gene expression matrix for further analysis.

Quality control, dimension-reduction and clustering

Scanpy v1.8.2 was used for quality control, dimensionality reduction and clustering under Python 3.7. For each sample dataset, we filtered expression matrix by the following criteria: (1) cells with gene count less than 200 or with top 2% gene count were excluded; (2) cells with top 2% UMI count were excluded; (3) cells with mitochondrial content > 10% were excluded; (4) genes expressed in less than 5 cells were excluded. After filtering, 42,581 cells were retained for the downstream analyses, with on average 766 genes and 1,157 UMIs per cell. The raw count matrix was normalized by total counts per cell and logarithmically transformed into normalized data matrix. Top 2000 variable genes were selected by setting flavor = ‘seurat’. Principle component analysis (PCA) was performed on the scaled variable gene matrix, and top 20 principle components were used for clustering and dimensional reduction. We used the Harmony algorithm to integrate the data and effectively remove batch effects17. Cells were separated into 24 clusters by using Louvain algorithm and setting resolution parameter at 1.2. Cell clusters were visualized by using Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP). The final UMAP visualization was performed on the batch-corrected dataset, ensuring that any clustering observed reflects genuine biological differences.

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) analysis

To identify DEGs, we used the Seurat FindMarkers function based on Wilcox likelihood-ratio test with default parameters, and selected the genes expressed in more than 10% of the cells in a cluster and with an average log (Fold Change) value greater than 0.25 as DEGs. Benjamini-Hochberg correction was applied to control the false discovery rate (FDR), and genes with adjusted p-values < 0.05 were considered differentially expressed. For the cell type annotation of each cluster, we combined the expression of canonical markers found in the DEGs with knowledge from literatures, and displayed the expression of markers of each cell type with heatmaps/dot plots/violin plots that were generated with Seurat DoHeatmap/DotPlot/Vlnplot function. Doublet cells were identified as expressing markers for different cell types, and removed manually.

Cell type annotation

The cell type identity of each cluster was determined with the expression of canonical markers found in the DEGs using SynEcoSys database. Heatmaps/dot plots/violin plots displaying the expression of markers used to identify each cell type were generated by Seurat v3.1.2 DoHeatmap/DotPlot/Vlnplot.

Pathway enrichment analysis

To investigate the potential functions of DEGs, the Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analysis18,19,20 were used with the “clusterProfiler” R package 3.16.1. Pathways with p_adj value less than 0.05 were considered as significantly enriched. GO gene sets including molecular function (MF), biological process (BP), and cellular component (CC) categories were used as reference.

Statistical analysis

Data are represented as the mean ± standard deviation. The Student’s t test was used to compare the two groups. The statistical significance was considered when p-values less than 0.05. GraphPad Prism version 8.0 was used for the statistical analysis (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, United States).

Results

Effect of CIH on renal histology

To investigate the impact of CIH on renal cellular diversity and transcriptional signatures, a comprehensive study including IH exposure, kidney tissue collection, single-nucleus isolation, sncRNA-seq analysis, and subsequent downstream analyses were conducted. The study scheme was presented in Fig. 1A. Histopathological examination with HE staining showed that NC group had normal morphological architecture of renal tissue, with no significant glomeruli and tubules necrosis. In contrast, CIH group showed renal injury with renal tubular epithelial cell edema, necrosis (Fig. 1B). Renal injury was also assessed using a 0–5 Jablonski scale. Compared with NC group, the renal injury scores in CIH group were significantly elevated (Fig. 1C).

Effect of CIH on renal histology. (A) Experimental design and workflow, including group assignment, single nucleus isolation, sequencing, and data analysis. (B) Representative hematoxylin and eosin staining of kidney sections from control and CIH-exposed rats (Original magnification, ×400; scale bar, 20 μm). (C) Renal injury was evaluated and quantified using the Jablonski scale to assess the extent of histopathological damage (n = 6). Data are shown as the mean ± SD. Statistical significance was determined using an unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

CIH alters the single-cell transcriptomic landscape of the rat kidney

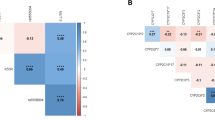

After quality control and filtering, a total of 42,581 cells (19,655 cells from NC group and 22,926 cells from CIH group) were obtained for further analysis. Using UMAP for dimensionality reduction followed by unsupervised clustering, we identified and annotated 13 distinct renal cell populations, including Collecting duct beta-intercalated cells (B_ICs), Collecting duct principal cells (PCs), Kidney loop of Henle epithelial cells (LOH), Proximal tubule cells (PT), Distal convoluted tubule cells (DCT), Podocytes, EpithelialCells_Spp1, EpithelialCells_Nrip3, Endothelial cells (ECs), Mesangial cells (Mesangial Cells), T and NK cells (T and NK), Mononuclear phagocytes (MPs) (Fig. 2A-C). Figure 2D and E display the top 10 and top 3 marker genes with the highest differential expression across all annotated cell types. These results reveal the transcriptional signatures that define and differentiate each of the 13 cell populations. Further comparison of cellular composition revealed treatment-related shifts in specific cell populations. CIH exposure resulted in an increased proportion of podocytes, while mesangial cells were reduced compared to the NC group, suggesting a potential CIH-induced imbalance in renal cell dynamics (Fig. 2F-G).

Overview of the 42,581 single cells isolated from the kidneys of NC and CIH rats (n = 3). (A) UMAP plot of kidney single cells colored by colored by experimental group (NC vs. CIH), illustrating the distribution of cells from each group. (B) UMAP plot of kidney single cells colored by each sample. (C) UMAP plot of kidney single cells colored by distinct cell types (D) Heatmap of the top 10 DEGs among all cell types according to log fold changes. (E) Bubble plot of the top 3 DEGs among all cell types according to log fold changes. (F)The proportion of cell subpopulations in the NC and CIH groups (G) Comparisons of cell subpopulation proportions between NC and CIH groups. Data are shown as the mean ± SD. Statistical significance was determined using an unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

PT and LOH cells

We then explored the effects of CIH on PT and LOH cells. Seven distinct populations were identified from PTs, including PT_Sds, PT_Cgnl1, PT_Ano4, PT_Mageb6b1, PT_Gng7, PT_Zbtb20, PT_Cyp24a1(Fig. 3A, B). CIH treatment was associated with a decrease in the proportions of PT_Cgnl1 and PT_Cyp24a1, accompanied by an increase in PT_Sds, PT_Ano4, PT_Mageb6b1, PT_Gng7 and PT_Zbtb20 (Fig. 3C). The identified DEGs among PT cell subsets are illustrated in Fig. 3D, E. As shown in Fig. 3F, a volcano plot was generated to identify and visualize the DEGs between the CIH and NC groups. The GO and KEGG pathway are listed in Fig. 3G-I. The enriched KEGG pathways about the down-regulated DEGs were related with Carbon metabolism, PPAR signaling pathway, Proximal tubule bicarbonate reclamation, and Peroxisome. LOH cells were clustered into 7 main clusters: LOH_Actg1, LOH_Nrg1, LOH_Itprid2, LOH_Ranbp3l, LOH_Mageb6b1, LOH_Pde10a, MDEpithelialCells (Fig. 4A, B). There were differences in distribution between NC group and CIH group (Fig. 4C). The top DEGs among LOH subsets were visually displayed in Fig. 4D, E. Figure 4F illustrates a volcano plot of the DEGs between the CIH and NC groups. Functional enrichment analysis was performed to elucidate the biological functions (Fig. 4G-I). KEGG pathway analysis revealed that down-regulated DEGs in LOH cell subsets were associated to Fatty acid degradation, Cysteine and methionine metabolism, and IL-17 signaling pathway.

Effects of CIH treatment on PT cell subsets and their associated biological pathways (n = 3). (A) UMAP plot showing distribution of PT subpopulations based on cell type-specific clustering. (B) UMAP plot of PT subpopulations colored by experimental group (NC vs. CIH). (C) The proportion of PT subpopulations in the NC and CIH groups (D) Heatmap of the top 10 DEGs among all cell types according to log fold changes. (E) Violin plot of the top 3 DEGs among all cell types according to log fold changes. (F) Volcano plot of DEGs between CIH and NC groups. (G) GO enrichment analysis of up-regulation pathways of PT cells in CIH vs. NC group. (H) GO enrichment analysis of down-regulation pathways of PT cells in CIH vs. NC group. (I) KEGG enrichment analysis of down-regulation pathways of PT cells in CIH vs. NC group.

Effects of CIH treatment on LOH cell subsets and their associated biological pathways (n = 3). (A) UMAP plot showing distribution of LOH subpopulations based on cell type-specific clustering. (B) UMAP plot of LOH subpopulations colored by experimental group (NC vs. CIH). (C) The proportion of PT subpopulations in the NC and CIH groups (D) Heatmap of the top 10 DEGs among all cell types according to log fold changes. (E) Violin plot of the top 3 DEGs among all cell types according to log fold changes. (F) Volcano plot of DEGs between CIH and NC groups. (G) GO enrichment analysis of up-regulation pathways of LOH cells in CIH vs. NC group. (H) GO enrichment analysis of down-regulation pathways of LOH cells in CIH vs. NC group. (I) KEGG enrichment analysis of down-regulation pathways of PT cells in CIH vs. NC group.

DCT and PC cells

Clustering analysis of DCT cells revealed seven subpopulations, including DCT_Egf, DCT_Rhbg, DCT_Sgpp2, DCT_Rgs3, and DCT_Slc8a1 (Fig. 5A, B). The distribution of clusters was different between NC group and CIH group (Fig. 5C). The most significant DEGs among DCT subsets were visually illustrated in Fig. 5D, E. Volcano plot detailing the DEGs profile between the CIH and NC groups were presented in Fig. 5F. The results of GO and KEGG analysis are shown in Fig. 5G-J. The up-regulated DEGs were related to Apoptosis, Aldosterone-regulated sodium reabsorption, while the down-regulated DEGs were associated with Insulin resistance, Glucagon signaling pathway, AMPK signaling pathway, and Adipocytokine signaling pathway. Five distinct populations were identified from PCs and the proportion varied (Fig. 6A-C). The top DEGs among PCs were visually displayed in Fig. 6D, E. A volcano plot of DEGs between CIH and NC groups were shown in Fig. 6F. Molecular functions, cytological components, biological and KEGG pathways of PCs are shown in Fig. 6G-I. KEGG pathway analysis suggested that down-regulated DEGs were associated to Insulin signaling pathway, Ubiquitin mediated proteolysis, Chemical carcinogenesis - reactive oxygen species, and Regulation of actin cytoskeleton.

Effects of CIH treatment on DCT cell subsets and their associated biological pathways (n = 3). (A) UMAP plot showing distribution of DCT subpopulations based on cell type-specific clustering. (B) UMAP plot of DCT subpopulations colored by experimental group (NC vs. CIH). (C) The proportion of DCT subpopulations in the NC and CIH groups (D) Heatmap of the top 10 DEGs among all cell types according to log fold changes. (E) Violin plot of the top 3 DEGs among all cell types according to log fold changes. (F) Volcano plot of DEGs between CIH and NC groups. (G) GO enrichment analysis of up-regulation pathways of DCT cells in CIH vs. NC group. (H) GO enrichment analysis of down-regulation pathways of DCT cells in CIH vs. NC group. (I) KEGG enrichment analysis of up-regulation pathways of DCT cells in CIH vs. NC group. (J) KEGG enrichment analysis of down-regulation pathways of DCT cells in CIH vs. NC group.

Effects of CIH treatment on PC cell subsets and their associated biological pathways (n = 3). (A) UMAP plot showing distribution of PC subpopulations based on cell type-specific clustering. (B) UMAP plot of PC subpopulations colored by experimental group (NC vs. CIH). (C) The proportion of PC subpopulations in the NC and CIH groups (D) Heatmap of the top 10 DEGs among all cell types according to log fold changes. (E) Violin plot of the top 3 DEGs among all cell types according to log fold changes. (F) Volcano plot of DEGs between CIH and NC groups. (G) GO enrichment analysis of up-regulation pathways of PC cells in CIH vs. NC group. (H) GO enrichment analysis of down-regulation pathways of PC cells in CIH vs. NC group. (I) KEGG enrichment analysis of down-regulation pathways of PC cells in CIH vs. NC group.

MPs

Sub-clustering of MPs revealed four distinct clusters, including BCells, Macrophages, Monocytes, cDCs (Fig. 7A, B). These cell populations distributed differently between NC and CIH group (Fig. 7C). The top DEGs among MPs subsets were visually displayed in Fig. 7D, E. A volcano plot, as depicted in Fig. 7F, was used to identify the DEGs between the CIH and NC groups. An enrichment analyses of MPs were performed (Fig. 7G-J). The up-regulated DEGs were related to Phagosome, Leukocyte transendothelial migration, JAK-STAT signaling pathway, while the down-regulated DEGs were associated with Osteoclast differentiation, B cell receptor signaling pathway.

Effects of CIH treatment on MP cell subsets and their associated biological pathways (n = 3). (A) UMAP plot showing distribution of MP subpopulations based on cell type-specific clustering. (B) UMAP plot of MP subpopulations colored by experimental group (NC vs. CIH). (C) The proportion of MP subpopulations in the NC and CIH groups (D) Heatmap of the top 10 DEGs among all cell types according to log fold changes. (E) Violin plot of the top 3 DEGs among all cell types according to log fold changes. (F) Volcano plot of DEGs between CIH and NC groups. (G) GO enrichment analysis of up-regulation pathways of MP cells in CIH vs. NC group. (H) GO enrichment analysis of down-regulation pathways of MP cells in CIH vs. NC group. (I) KEGG enrichment analysis of up-regulation pathways of MP cells in CIH vs. NC group. (J) KEGG enrichment analysis of down-regulation pathways of MP cells in CIH vs. NC group.

Discussion

In this study, we systematically investigated the impact of CIH on the kidney using snRNA-seq in a rodent model. Histological analysis demonstrated that CIH induced significant renal injury, including tubular epithelial cell edema and necrosis. Transcriptomic profiling revealed 13 distinct renal cell populations and significant shifts in their composition under CIH, notably an increase in podocytes and a reduction in mesangial cells, suggesting disrupted glomerular homeostasis. Subpopulation analysis further revealed distinct cell-type-specific transcriptional alterations across renal cell populations, characterized by suppressed metabolic pathways (e.g., carbon metabolism, fatty acid degradation, cysteine and methionine metabolism) and signaling pathways (e.g., PPAR and IL-17 signaling) in PT and LOH cells, activation of apoptotic and sodium reabsorption pathways in DCT cells, and enhanced inflammatory and phagocytic signaling in MPs. These findings offer a detailed cellular and molecular map of CIH-induced renal injury and provide novel insights into potential therapeutic targets.

Evidence supporting the association between OSA and renal damages is steadily accumulating. A cohort study of 1,295 adults demonstrated that moderate and severe OSA significantly elevated the risk of CKD progression, independent of traditional CKD risk factors21. A meta-analysis of 4,567 individuals demonstrated a significant association between OSA and an elevated risk of early kidney damage22. In our previous analysis of 13,902 subjects from the NHANES dataset, self-reported frequent sleep apnea was found to be an independent risk factor for albuminuria in middle-aged and older adults23. In a cohort study of more than 3 million U.S. veterans, most of whom were male with a mean age of 60.5 years, a diagnosis of incident OSA was associated with an increased risk of CKD and an accelerated decline in kidney function over time, compared with individuals without OSA24. Collectively, these findings underscore a consistent and independent association between OSA and the development or progression of kidney dysfunction across diverse populations.

Several previous animal studies have evaluated the effect of CIH on the kidney. A previous animal study demonstrated that CIH induced morphological damage in the kidneys of growing rats, characterized by tubular epithelial hypertrophy and glomerular dilation. These changes were accompanied by increased HIF-1α expression and decreased antioxidant enzyme levels, suggesting that oxidative stress plays a pivotal role in CIH-induced renal injury25. Another study demonstrated that CIH induced renal injury in mice, characterized by glomerular hypertrophy, mesangial matrix expansion, elevated expression of glomerular growth factors, and increased cellular apoptosis26. Zhang et al.27 demonstrated that CIH accelerated renal apoptosis and autophagy, while telmisartan alleviated these pathological changes, suggesting its potential role in preventing CIH-induced renal impairment in OSA patients. Abuyassin et al.28 demonstrated that administration of α-lipoic acid in mice exposed to CIH effectively reduced renal tubular injury and cellular apoptosis. Additionally, α-lipoic acid treatment alleviated CIH-induced glomerular hypertrophy and decreased urinary albumin excretion. However, these traditional approaches lack cellular resolution and fail to capture the complex heterogeneity of kidney cell populations and their distinct responses to CIH. In contrast, snRNA-seq enables high-resolution profiling of gene expression at the individual cell level, offering a more precise understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying CIH-induced renal injury29.

Our findings revealed that CIH exposure was associated with pronounced alterations in renal parenchymal cells, such as PT and LOH cells. CIH downregulated key metabolic and transport-related pathways, including carbon metabolism, PPAR signaling, and fatty acid degradation. These pathways play essential roles in proximal tubule function: carbon metabolism supports energy production necessary for active solute reabsorption, fatty acid degradation provides ATP for tubular transport processes, and PPAR signaling regulates lipid metabolism and maintains mitochondrial integrity30,31. Consistent with prior animal studies, these alterations likely contribute to impaired mitochondrial function and reduced tubular reabsorption capacity under hypoxic conditions32,33,34.We noted that subpopulations within PT and LOH cells responded differentially to CIH, suggesting functional heterogeneity that may underlie variable vulnerability to hypoxic injury. The upregulation of pathways such as apoptosis and aldosterone-regulated sodium reabsorption in the of DCT indicated an adaptive response to cellular stress and disruptions in sodium handling. This suggested that the renal cells were undergoing stress responses to maintain homeostasis under hypoxic conditions. On the other hand, the downregulation of pathways related to insulin resistance, AMPK signaling, and glucagon signaling implied significant alterations in metabolic regulation, pointing to a disruption of normal energy homeostasis. In PC cells, the association with insulin signaling, ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis, and reactive oxygen species production highlighted the potential metabolic reprogramming in response to CIH. Additionally, the downregulation of DEGs involved in insulin signaling and actin cytoskeleton regulation suggested a compromised cellular response to insulin and potential alterations in cytoskeletal integrity. These factors may contribute to renal dysfunction under CIH conditions. Overall, these findings underscored the metabolic reprogramming occurring in both DCT and PC cells, illustrating a balance between adaptive stress responses and the onset of cellular dysfunction in CIH.

Beyond tubular and glomerular cells, CIH significantly impacted the renal immune microenvironment. We observed increased activation of MPs, with transcriptomic enrichment in pro-inflammatory pathways such as JAK-STAT signaling and leukocyte transendothelial migration. This inflammatory profile aligned with prior studies showing that hypoxia promoted systemic inflammation and immune cell infiltration in the kidney35,36,37. However, our single-cell data allowed us to distinguish subpopulations of macrophages, monocytes, and dendritic cells with distinct responses, which has not been previously reported. Interestingly, downregulation of B cell-related pathways and osteoclast differentiation suggested that CIH not only activated innate immunity but may also suppress or dysregulate adaptive immune responses in the kidney. These findings align with the established role of hypoxia and HIF signaling as key regulators of B cell biology, including B cell development, metabolism, and function38.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to employ a single-cell approach to investigate the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying CIH-induced renal injury. However, several limitations should be noted. First, the findings were based on a rodent model of CIH, which may not fully capture the complexity of human OSA and CKD comorbidities. Second, the analysis focused on transcriptomic data, and did not include protein-level validation or functional assays to confirm cellular behavior. Follow-up studies employing approaches such as gene knockdowns under hypoxic culture conditions are warranted to determine whether the identified DEGs play a causal role in renal injury. Third, while we identified DEGs and pathways, causal relationships between these changes and renal dysfunction require further mechanistic exploration. Fourth, although only three renal tissue samples per group were used, this sample size is typical for early exploratory snRNA-seq studies. While sufficient for preliminary insights, it may not capture full inter-individual variability. Larger sample sizes are needed in future studies to validate these findings and assess transcriptomic diversity under CIH conditions. Fifth, the observed increase in podocyte nuclei accompanied by a reduction in mesangial cell nuclei may partly reflect technical factors, such as variability in nuclear isolation efficiency, rather than true biological proliferation or depletion. The results should therefore be interpreted with caution. Lastly, although the study uncovered key immune alterations, we did not assess systemic immune status or other organs that may interact with the kidney under CIH.

Conclusions

This study provides a comprehensive single-cell transcriptional atlas of the kidney under CIH, revealing profound changes in both renal parenchymal and immune cell compartments. The identification of cell-type-specific injury patterns and immune activation under CIH offers valuable mechanistic insights into how OSA may contribute to renal damage. These findings not only contribute to a better understanding of OSA-related renal injury at the cellular level but also help for developing targeted therapies aimed at mitigating OSA-induced renal dysfunction.

Data availability

The data presented in this study have been deposited in the NCBI SRA database under accession number PRJNA1269744. The processed gene expression data are available in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database under accession number GSE307046. Both datasets are publicly available.

References

Leng, Y., McEvoy, C. T., Allen, I. E. & Yaffe, K. Association of Sleep-Disordered breathing with cognitive function and risk of cognitive impairment: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol. 74, 1237–1245. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.2180 (2017).

Reutrakul, S. & Mokhlesi, B. Obstructive sleep apnea and diabetes: A state of the Art review. Chest 152, 1070–1086. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2017.05.009 (2017).

Floras, J. S. Sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease: an enigmatic risk factor. Circ. Res. 122, 1741–1764. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.310783 (2018).

Lin, C. H., Perger, E. & Lyons, O. D. Obstructive sleep apnea and chronic kidney disease. Curr. Opin. Pulm Med. 24, 549–554. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCP.0000000000000525 (2018).

Umbro, I., Fabiani, V., Fabiani, M. & Angelico, F. Del Ben, M. A systematic review on the association between obstructive sleep apnea and chronic kidney disease. Sleep. Med. Rev. 53, 101337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2020.101337 (2020).

Abuyassin, B., Sharma, K., Ayas, N. T. & Laher, I. Obstructive sleep apnea and kidney disease: A potential bidirectional relationship? J. Clin. Sleep. Med. 11, 915–924. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.4946 (2015).

Lin, C. H., Lurie, R. C. & Lyons, O. D. Sleep apnea and chronic kidney disease: A State-of-the-Art review. Chest 157, 673–685. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2019.09.004 (2020).

Ziegenhain, C. et al. Comparative Analysis of Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Methods. Mol Cell 65, 631–643 e634, (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2017.01.023

Chen, Z. et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing highlights the role of inflammatory cancer-associated fibroblasts in bladder urothelial carcinoma. Nat. Commun. 11, 5077. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-18916-5 (2020).

Minati, M. A., Fages, A., Dauguet, N., Zhu, J. & Jacquemin, P. Optimized nucleus isolation protocol from frozen mouse tissues for single nucleus RNA sequencing application. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 11, 1243863. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2023.1243863 (2023).

Deleersnijder, D. et al. Current methodological challenges of Single-Cell and Single-Nucleus RNA-Sequencing in glomerular diseases. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 32, 1838–1852. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2021020157 (2021).

Kong, S. et al. Single-cell omics: A new direction for functional genetic research in human diseases and animal models. Front. Genet. 13, 1100016. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2022.1100016 (2022).

Bawa, G., Liu, Z., Yu, X., Qin, A. & Sun, X. Single-Cell RNA sequencing for plant research: insights and possible benefits. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23094497 (2022).

Cortese, R. et al. Single-cell RNA-seq uncovers cellular heterogeneity and provides a signature for paediatric sleep Apnoea. Eur. Respir J. 61 https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01465-2022 (2023).

Chen, J. et al. 2-Methoxyestradiol attenuates lung injury induced by chronic intermittent hypoxia via inhibiting the HIF1-alpha/SLC7A11 pathway. Sci. Rep. 15, 17601. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02675-8 (2025).

Islam, C. F. et al. Ischaemia-reperfusion injury in the rat kidney: the effect of preconditioning. Br. J. Urol. 79, 842–847. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1464-410x.1997.00209.x (1997).

Korsunsky, I. et al. Fast, sensitive and accurate integration of single-cell data with harmony. Nat. Methods. 16, 1289–1296. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-019-0619-0 (2019).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Kawashima, M. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG for taxonomy-based analysis of pathways and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D587–D592. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkac963 (2023).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/28.1.27 (2000).

Kanehisa, M. Toward Understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci. 28, 1947–1951. https://doi.org/10.1002/pro.3715 (2019).

Beaudin, A. E. et al. Risk of chronic kidney disease in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep 45 https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsab267 (2022).

Liu, T., Zhan, Y., Wang, Y., Li, Q. & Mao, H. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome and risk of renal impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis with trial sequential analysis. Sleep. Breath. 25, 17–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11325-020-02090-5 (2021).

Chen, L. D. et al. Association between self-reported sleep apnea and albuminuria among middle age and elderly population: results from National health and nutrition examination survey. Med. (Baltim). 104, e41515. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000041515 (2025).

Molnar, M. Z. et al. Association of incident obstructive sleep Apnoea with outcomes in a large cohort of US veterans. Thorax 70, 888–895. https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-206970 (2015).

Poonit, N. D. et al. Chronic intermittent hypoxia exposure induces kidney injury in growing rats. Sleep. Breath. 22, 453–461. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11325-017-1587-1 (2018).

Abuyassin, B., Badran, M., Ayas, N. T. & Laher, I. Intermittent hypoxia causes histological kidney damage and increases growth factor expression in a mouse model of obstructive sleep apnea. PLoS One. 13, e0192084. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0192084 (2018).

Zhang, X. B. et al. Telmisartan attenuates kidney apoptosis and autophagy-related protein expression levels in an intermittent hypoxia mouse model. Sleep. Breath. 23, 341–348. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11325-018-1720-9 (2019).

Abuyassin, B., Badran, M., Ayas, N. T. & Laher, I. The antioxidant alpha-lipoic acid attenuates intermittent hypoxia-related renal injury in a mouse model of sleep apnea. Sleep 42 https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsz066 (2019).

Ma, M. et al. Novel insights into kidney disease: the scRNA-seq and Spatial transcriptomics approaches: a literature review. BMC Nephrol. 26, 181. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-025-04103-5 (2025).

Curthoys, N. P. & Moe, O. W. Proximal tubule function and response to acidosis. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 9, 1627–1638. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.10391012 (2014).

Gao, J. & Gu, Z. The role of peroxisome Proliferator-Activated receptors in kidney diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 13, 832732. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.832732 (2022).

Nourbakhsh, N. & Singh, P. Role of renal oxygenation and mitochondrial function in the pathophysiology of acute kidney injury. Nephron Clin. Pract. 127, 149–152. https://doi.org/10.1159/000363545 (2014).

Schiffer, T. A. & Friederich-Persson, M. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species and kidney hypoxia in the development of diabetic nephropathy. Front. Physiol. 8, 211. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2017.00211 (2017).

Rahbar Saadat, Y., Khatibi, H., Sani, S. M., Zununi Vahed, A., Ardalan, M. & S. & Ischemic tubular injury: Oxygen-sensitive signals and metabolic reprogramming. Inflammopharmacology 31, 1657–1669. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10787-023-01232-x (2023).

Tanaka, S., Portilla, D. & Okusa, M. D. Role of perivascular cells in kidney homeostasis, inflammation, repair and fibrosis. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 19, 721–732. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41581-023-00752-7 (2023).

Basso, P. J., Andrade-Oliveira, V. & Camara, N. O. S. Targeting immune cell metabolism in kidney diseases. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 17, 465–480. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41581-021-00413-7 (2021).

Chen, Y. et al. Hypoxic/Ischemic Inflammation, MicroRNAs and delta-Opioid receptors: Hypoxia/Ischemia-Sensitive Versus-Insensitive organs. Front. Aging Neurosci. 14, 847374. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2022.847374 (2022).

Zhang, J. et al. Hypoxia and hypoxia-inducible factor signals regulate the development, metabolism, and function of B cells. Front. Immunol. 13, 967576. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.967576 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Singleron Biotechnologies for their help with the single-cell RNA sequencing analysis. We sincerely thank Dr. Jiefeng Huang from The First Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University for providing assistance with the animal experiments.

Funding

This work was supported by Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (2022J011474), National Natural Science Foundation of China (82170103), Young people training project from Fujian Province Health Bureau (2022GGA053), Startup Fund for Scientific Research of Fujian Medical University (2024QH1687), and grant PDA202202 for scientific research of Zhangzhou Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LDC supervised and designed this project. JS, WSH, and YNH performed the animal experiment. JS and XBZ prepared samples for scRNA-seq. YPH, ZWH and LL analyzed the scRNA-seq data. YZH performed pathology analysis. YPH and LDC wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Fujian Medical University (IACUC FJMU 2022-0031). All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. All methods are also reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, YP., Huang, ZW., Huang, YZ. et al. Single-nucleus transcriptome profiling provides insights into the pathophysiology of OSA-related renal injury. Sci Rep 15, 36466 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23736-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23736-y