Abstract

The Persistence of SARS-CoV-2 in tissues has been proposed as a driver of prolonged symptoms in long COVID. Pulmonary rehabilitation with exercise training is a well-established intervention for improving symptoms, functional capacity, and inflammation in chronic cardiorespiratory diseases. To investigate whether long COVID is associated with persistent viral or immune-related signals, we analyzed the long RNA profile of circulating extracellular vesicles (EVs) to determine the presence of virus-related transcripts and assess changes in response to exercise training. Fourteen adults with long COVID participated in this single-center pilot clinical trial and completed a 10-week aerobic exercise training program (twenty 1.5 h sessions). Serum-derived EV RNA profiles were analyzed via sequencing at rest (T0) and peak cardiopulmonary exercise testing (T1), before (V2) and after (V24) exercise training. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified (q < 0.05), and pathway activation analysis was performed. Serum EVs carried diverse RNA species, including protein-coding RNAs, long non-coding RNAs, short non-coding RNAs, and pseudogenes, with no virus-related RNAs detected. No significant DEGs were identified at rest between pre- and post-training, nor in response to acute exercise at pre-training. However, following training, 53 DEGs were found at peak exercise (V24T1) compared to rest (V24T0), including three upregulated genes (ANK3, FTO, FCN1) and 50 downregulated genes (TOP 5: MYL9, NRGN, H2AC6, MAP3K7CL, B2M). These genes were primarily involved in inflammation and metabolism. Pathway analysis revealed significant regulation of 100 pathways at post-training compared to pre training, predominantly inactivated, including pathways involved in inflammation (STAT3 signaling) and metabolism (O-linked glycosylation). Acute exercise and exercise training modulated EV-associated gene expression in long COVID, primarily through transcriptional downregulation. Suppression of inflammation- and immune-related genes post-training highlights potential molecular mechanisms underlying symptom improvement and identifies candidate biomarkers of recovery biology in long COVID. Importantly, while exercise training did not substantially alter EV RNA content at rest, it enhanced the body’s ability to mount a dynamic EV-mediated molecular response during exertion, reflecting improved physiological adaptability.

Clinical trial registration number: NCT05398692.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Long COVID, or post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC), is a complex and multifaceted condition characterized by persistent symptoms for months to years following acute COVID-19 infection1. While the mechanisms underlying long COVID remain unclear, accumulating evidence suggests that viral components such as SARS-CoV-2 RNA and antigens can persist in various tissues, including the lung, brain, lymph nodes, plasma, and gastrointestinal tract, for months after infection2,3,4,5. This viral persistence may contribute to chronic inflammation and prolonged symptomatology.

Extracellular vesicles are nanosized lipid-bound particles (30–1000 nm) released by all cells and play an important role in intracellular communication by transporting bioactive cargo including RNA, proteins, and metabolites6. Importantly, EVs have been shown to carry foreign pathogens, viral proteins, and RNA in other infectious diseases, potentially promoting immune activation even in the absence of active viral replication7,8. As the composition of EVs reflects the physiological state of their cells of origin, profiling EV cargo may provide insights into ongoing pathological processes, including persistent viral activity9. Thus, EVs represent a promising, minimally invasive source of candidate biomarkers for long COVID, and may also offer mechanistic insights into ongoing pathological signaling.

Pulmonary rehabilitation with exercise training is a well stablished approach in treatment of chronic respiratory diseases in adults, aiming to alleviate symptoms and improve functional ability. Recent studies, including ours, demonstrate that structured aerobic exercise training improved cardiorespiratory fitness, quality of life, anxiety, depression, brain fog, fatigue and 6-min walk distance (6MWD) in individuals with long COVID from low-severity acute infections10,11,12,13,14,15. While the clinical benefits of exercise are well-documented, the underlying biological mechanisms remain poorly understood.

Regular exercise training is well known to reduce the risk of chronic metabolic and cardiorespiratory diseases, in part through its anti-inflammatory effects16,17,18. These beneficial effects are thought to be mediated by the release of exercise-induced bioactive molecules, known as exerkines, which can enter the circulation and impact immune and metabolic pathways19,20. Notably, many exerkines are packaged into extracellular vesicles (EVs), enabling targeted intercellular communication16. Although the immunoregulatory function of EVs following exercise is in the early stages of discovery21,22,23, emerging evidence suggests that EVs released during exercise can provide multisystemic benefits, influencing targeting tissues such as the liver, CNS, and lungs24,25,26,27. Whether such EV-mediated signaling contributes to symptom improvement in long COVID remains unknown.

In this study, we aimed to determine whether serum EVs from individuals with long COVID carry viral RNA and to assess whether acute exercise or exercise training modulates the EV-associated RNA transcriptome, particularly in relation to immune and inflammatory pathways. By analyzing EV-derived long RNAs at rest and peak exercise, before and after a structured 10-week aerobic exercise training program, we aimed to identify candidate biomarkers of viral persistence and uncover molecular mechanisms underlying exercise-mediated symptom improvement in long COVID. This approach offers new insight into the EV transcriptomic profile in long COVID and its responsiveness to physiological stress, advancing our understanding of recovery biology in this poorly understood condition.

Materials and methods

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of The Lundquist Institute for Biomedical Innovation at Harbor–UCLA Medical Center (Lundquist # 32558-01; ClinicalTrials.Gov Identifier: NCT05398692). Written informed consent was provided and documented prior to participation. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. A detailed description of the study design and methods can be found in our previous publication10.

Study design, enrollment, screening

This single-center pilot clinical trial was conducted from February 2022 to December 2023 at the Lundquist Institute, located at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, California, USA. Inclusion criteria were adults aged 18 years or older with a confirmed COVID-19 infection at least 12 weeks prior to enrollment (documented by PCR or patient report when testing was unavailable) and were experiencing one or more persistent symptoms, such as fatigue, dyspnea, exercise intolerance, post-exertional malaise (PEM), or difficulty breathing, consistent with long COVID definitions proposed CDC and WHO28. Exclusion criteria included inability to complete acceptable pulmonary function tests (PFT) or cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET), oxygen desaturation below 80% during exercise, recent completion of a pulmonary rehabilitation program, concurrent participation in another clinical trial, pregnancy or breastfeeding, recent malignancy, injectable insulin use, HIV, systemic corticosteroid use, or any significant respiratory disease unrelated to long COVID that might increase participation risk.

During the screening visit, informed consent was obtained, followed by a detailed medical history, physical examination, and assessments of vaccine status and smoking history. Vital signs- including resting blood pressure, heart rate, oxygen saturation, and a 12-lead ECG- were recorded. Laboratory tests were performed to ensure participants’ safety, including a complete blood count, renal and liver function tests, and inflammatory markers such as D-dimer, Brain Natriuretic Peptide (ProBNP), Ferritin, C-reactive protein (CRP), and high-sensitivity Troponin to exclude myocarditis. To further evaluate autonomic function, a 10-min NASA lean test was conducted to rule out postural orthostatic hypotension and heart rate dysregulation29.

Pulmonary assessments included pre-bronchodilator spirometry, body plethysmography, and single breath diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO), following ATS/ERS guidelines30,31,32,33. Post-bronchodilator spirometry was conducted 20 min after the inhalation of 4 puffs of albuterol (400 mg). Predicted spirometry values were drawn from NHANES III standards34, with additional reference values for lung volumes35 and DLCO 36. Fourteen out of 21 subjects completed all exercise trials and the study.

Cardiopulmonary exercise test (CPET)

A continuously increasing incremental CPET was performed at 10–20 watts/min, based on individual fitness for each subject, using an electromagnetically braked cycle ergometer (Excalibur Sport PFM, Lode, Groningen, NL, USA). Exercise intolerance was defined by the inability to maintain a pedaling cadence > 50 rpm despite encouragement. Gas exchange and ventilatory parameters were measured breath by breath (Ultima CPX, MGC Diagnostics, St. Paul, MN, USA), with participants breathing through a mouthpiece and wearing a nose clip. Heart rate, rhythm disturbances, and ST-T wave changes were continuously monitored via a 12-lead ECG (Mortara, Milwaukee, WI, USA). Exercise blood pressure (Suntech Tango, Morrisville, NC, USA), and ratings of perceived dyspnea (RPEdyspnea) and leg fatigue (RPElegs) were collected every 2 min using the modified Borg CR-10 scale37. The gas exchange lactate threshold (GE-LAT) was assessed using the V-slope method and corroborated with ventilatory equivalents (VE/VO2 and VE/VCO2) and end-tidal partial pressure responses (PETO2 and PETCO2)38. The dead space to tidal volume ratio (VD/VT) was assessed using transcutaneous PCO2 as a substitute for arterial PCO2 in the mass balance equation (Tosca 500, Radiometer America, Brea, CA, USA)39,40. CPET data were processed and analyzed by Medical Graphics Corporation, BreezeSuite™ 8.4 SP6 Cardiorespiratory Diagnostic Software, 07/10/2018 (www.mgcdiagnostics.com).

Predicted values for exercise variables were obtained from Hansen et al. 41.

Exercise training

Details of the exercise training protocol have been described previously10. Briefly, Following CPET, participants completed a 10-week, twice-weekly on-site aerobic training program, with each session lasting 60 to 90 min and involving first cycle and then treadmill exercise. All sessions were directly supervised. Initial exercise duration was set to 10 min, and participants were assessed for post-exertional malaise (PEM) within 48 h after each session, either at the next visit or by phone. If PEM symptoms appeared or worsened, exercise time and intensity were reduced by 50%. If no PEM was reported, exercise duration was gradually increased, ultimately reaching up to 60 min (combined treadmill and cycle ergometer) by the end of the 10-week training.

Cycle ergometer training began at an intensity equal to 25% of each participant’s initial CPET peak work rate and progressed from constant work rate to interval training as tolerated. Treadmill constant work rate training started at a speed of 1 MPH, 0% incline, and a duration of 5 min, and progressed as individually tolerated. Target perceived exertion ratings (RPE) were set between 3 and 5 during training. Each session included warm-up and cool-down periods, and participants received instruction in breathing techniques to manage dyspnea and anxiety, as well as training with Therabands® (Akron, OH, USA), gentle yoga, stretching, balance exercises, and relaxation techniques. Guidance on nutrition, hydration, and self-care was also provided.

Post-training assessments

The CPET, blood collection, and serum EVs isolation were repeated at the end of the 10-week training program.

Blood collection and isolation of serum EV

Venous blood samples for EV analysis were obtained at rest (time T0) and at peak exercise (time T1) CPET. This occurred both before training (V2) and after exercise training (V24) (Fig. 1A). At each sample collection, 2 mL of blood was collected in a K2-EDTA tube to analyze complete blood count (CBC), and 4 mL of blood was collected for serum isolation and EVs extraction. Serum was separated by centrifugation at 3000 g for 15 min. Next, 250μL serum was mixed with 67 μL ExoQuick ULTRA solution (EQULTRA-20A-1, SBI System Biosciences, Inc.) and incubated for at least 30 min at 4 °C. EVs pellet were resuspended and added to pre-washed ExoQuick ULTRA columns. After serial centrifugations, EVs were collected and stored at -80 °C for batch analyses.

Transcriptome Profiling of Serum-Derived EVs in Long COVID Patients in response to acute exercise and exercise training. (A) study design. (B) particle size and (C) particle concentration at peak acute incremental exercise (green) versus rest (red) before and after exercise training. (D) particles size and distribution in all groups. (E) The percentage counts of different types of expressed RNAs. (F) total RNA count per number of samples. (G) Hierarchical clustering of normalized-filtered expressed RNAs. For all volcano plots (H–K), the x-axis is log2 fold-change and the y-axis is − log10 of the nominal p value; points are colored by nominal significance (p < 0.05), and only genes passing Benjamini–Hochberg correction (FDR < 0.05) are labeled. (H) Peak exercise versus rest before training. (I) Rest post-training versus pre-training. (J) Peak exercise versus rest after training. (K) Peak exercise post-training versus pre-training. DEG: differentially expressed genes, V2: pre-training, V24: post-training, T0: rest, T1: peak exercise.

EVs characterization

Extracellular vesicle size and concentration were measured by Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) (NS300 NanoSight; Malvern Panalytical, Malvern, United Kingdom), calibrated using 200 µM beads. Briefly, EVs were thawed on ice and diluted in PBS so that the counts were within the dynamic range of the instrument at 108 particles/ml. Data was analyzed using NanoSight NTA software v3.40 (https://www.malvernpanalytical.com/en/support/product-support/software/nanosight-nta-software-update-v3-4).

RNA isolation and RNAseq

RNA isolation was carried out with a cell free circulating and exosomal RNA purification kit (Norgen Biotek, 51,000). Briefly, EVs were incubated in lysis buffer with 2-mercaptoethanol and at 60 °C, and nucleic acids were precipitated with ethanol, and captured onto the column. To remove traces of contaminating DNA, samples were treated with DNase I (Norgen Biotek), on-column, followed by washes and elution with RNase free DNase free ultra-pure water. RNA quantity was determined with a fluorometric assay (ThermoFisher, R11490) in 96 well plate format, using the low range standard curve.

Whole transcriptome library preparation was performed using up to 2 ng RNA (Takara Bio, SMARTer Stranded Total RNA-Seq Kit v3—Pico Input Mammalian and SMARTer RNA Unique Dual Index Kits, 634,485, 634,452). To determine if any differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were associated with the SARS-CoV-2 virus, the SARS-CoV-2 reference genome was included in the mapping and annotation for each sample. Strand-specific, dual-indexed libraries were generated with the following parameters: RNA fragmentation at 94 °C for 2 min, 5 cycles of PCR1, and 16 cycles of PCR2. Libraries were quantified using qPCR (Roche, KK4824) and Agilent’s TapeStation 4200 instrument with the D1000 High Sensitivity kit. Equimolar pools were re-quantified via qPCR and TapeStation, spiked with 1% PhiX, and sequenced across lanes of a 10B flow cell on Illumina’s NovaSeq X to 50 million paired-end reads using 300-cycle kits.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), unless indicated otherwise. Statistical significance was set at a threshold of p < 0.05. Data distribution was assessed for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test, histograms, Q-Q plots, and boxplots. Given that this was a pilot study, no formal sample size calculation was performed in advance. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS software (version 24.0; IBM, Chicago, IL, USA). For CPET outcomes, paired t-tests were used to examine pre- and post-training differences in cardiorespiratory and perceptual responses.

For immune cell counts, two-way repeated-measures ANOVAs (acute exercise × training) were used to examine pre- and post-training differences at rest and at peak CPET work rate. Greenhouse–Geisser corrections were applied where necessary, and significant interactions between acute exercise and training were further investigated using paired t-tests and Fisher’s Least Significant Difference (LSD) test.

For RNAseq data analysis, Fastq files sequenced from multiple lanes were combined. Unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) were extracted to eliminate amplification bias, and adapter sequences were trimmed using Cutadapt v4.4 (https://cutadapt.readthedocs.io/en/stable/). Potential contamination was assessed using Fastq Screen v0.15.3 (https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastq_screen/) by comparing sequences against a panel of non-human genomes. Reads were then aligned to the GRCh38 reference genome using STAR v2.7.10b (https://github.com/alexdobin/STAR), and gene-level quantification was performed with FeatureCounts [FeatureCounts from the Subread package (v2.0.6) (https://subread.sourceforge.net/featureCounts.html)]. For downstream analysis, duplicate reads were removed, and genes with fewer than 10 counts in at least half the samples were filtered out. Data normalization and differential expression analysis were conducted in R (v4.4.0) using the DESeq2 (https://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/DESeq2.html) package. DESeq2 implemented a negative-binomial GLM (design = ~ patient + condition) and testing each condition contrast via the Wald test, p values were adjusted for multiple testing by the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure.

Results

Participants/demographics

14 subjects completed exercise training, and their demographics are presented in Table 1. Participating subjects were older (53.5 y ± 11.6), primarily male (57%), and obese (BMI 32.5 ± 8.4). The primary symptoms were brain fog (100%), fatigue (86%), post exertional malaise (57%), exercise intolerance (46%), and dyspnea (36%). The hemoglobin/hematocrit, CRP, Pro-BNP, and troponins were all within normal ranges. Pulmonary function testing results were low normal (~ 90% of predicted for spirometry, lung volumes, and gas transfer).

Exercise training and compliance

The 10-week moderate intensity exercise training intervention was well tolerated. Compliance with on-site visits was 96%. The average amount of exercise time with each visit (outside of warm up and cool down) was 43 min ± 9.

CPET pre- and post-training

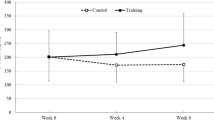

Peak oxygen uptake increased after training by 7.4%, from 1.880 ± 0.69 to 2.03 ± 0.07 L/min. Peak work rate increased by 16% (Table 1).

White blood cell (WBC) numbers

Total WBC and Neutrophils, Monocytes, and Lymphocytes all increased with acute exercise. There did not appear to be any diminution or augmentation of this response post training (Table 2). There was a significant effect of acute exercise on WBC counts (ANOVA, p < 0.05), with the expected increase from rest to peak exercise during CPET (Table 2), however exercise training did not produce any significant change in WBC counts.

EVs size and concentration

NTA analysis revealed no significant changes in particles size and concentration in response to acute exercise and exercise training (p > 0.05) (Fig. 1B–D).

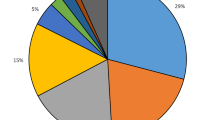

Acute exercise (CPET) at post-training modifies RNA content of serum EVs in LC-Covid patients

To identify any bioactive molecule involved in both long COVID pathogenesis and the effects of exercise training, we focused on the long RNA content of serum EVs. RNA-laden EVs have been shown to play a significant role in respiratory diseases by delivering various RNA molecules such as protein coding and non-coding RNAs42,43,44. EVs enriched RNAs also contribute to the beneficial effects of exercise44,45,46,47,48,49. In the current study, for RNA profiling, a total of 91,372 annotated genes including protein-coding RNAs (avg = 14,317/sample), long non-coding RNAs (lncRNA) (avg = 16,736/sample), short non-coding RNAs (avg = 443/sample), pseudogenes (avg = 2890/sample) and some unknown genes (TEC) (avg = 231/sample) were identified (Fig. 1E). The overall RNA yield distribution from serum-derived EV samples confirmed that most samples contained less than 1.5 ng of total RNA, with the majority falling between 0.8–1.5 ng (Fig. 1F). The number of detected RNA species are almost equal among different timepoints. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in serum EVs of long COVID patients between Rest (T0) and Peak exercise (T1) conditions, as well as between pre- and post-training (V2 vs. V24), were filtered by a q value < 0.05. The q value is an adjusted p value calculated using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure to control the false discovery rate (FDR). The clustering results using all DEGs exhibited crude discrimination between pre- and post-training RNA profiles in long COVID patients (Fig. 1G).

To determine if any DEGs were associated with the SARS-CoV-2 virus, the SARS-CoV-2 reference genome was included in the mapping and annotation for each sample. No transcripts mapping the SARS-CoV-2 genome were identified in any of the samples.

RNA sequencing analysis revealed no significant DEGs at rest between pre- and post-training (V24T0 vs V2T0) based on q values (q < 0.05, Fig. 1I). Similarly, at the pre-training time point (V2T1 vs V2T0), no significant DEGs were identified when comparing peak exercise to rest (q < 0.05, Fig. 1H). However, after training, 53 DEGs were identified at peak exercise (V24T1 vs. V24T0), including three upregulated genes ANK3 (q = 0.0457), FTO (q = 0.0472), and FCN1 (q = 0.0012) and 50 downregulated genes (Table 3, Fig. 1J). Among the top downregulated genes, MYL9 (q = 0.0001), NRGN (q = 0.0042), H2AC6 (q = 0.0042), MAP3K7CL (q = 0.0281), and B2M (q = 0.0012) were notable (Table 3). Also, no DEGs were found at peak exercise between pre- and post-training time points (V24T1 vs V2T1) based on q values (Fig. 1K).

Pathway analysis of EV-RNAs

Using genes passing a nominal p value < 0.05, pathway analysis using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) identified significantly regulated (activated and inactivated) pathways (z-score >|0|) in serum EVs of long COVID patients in response to acute exercise and exercise training. A comparison of resting EV profiles between pre- and post-training (V24T0 vs. V2T0) revealed 100 significantly regulated pathways (based on 398 regulated genes, p < 0.05), including 32 activated and 68 inactivated pathways. The top 50 are shown in Fig. 2A.

Differentially regulated (activated and inactivated) signaling pathways in response to acute exercise and exercise training in serum EVs of long COVID patients. (A) activated (orange) and inactivated (blue) signaling pathways at rest at post-training (V24T0) vs pre-training (V2T0). (B) Differentially regulated pathways at peak exercise at post-training vs pre-training. (C) Differentially regulated pathways at peak exercise (T1) vs rest (T0) at pre-training (D). Differentially regulated pathways at peak exercise (T1) vs rest (T0) at post-training (D). V2: pre-training, V24: post-training, T0: rest, T1: peak exercise.

Among the significantly inactivated pathways at V24T0 compared to V2T0 were the Generic Transcription Pathway (z-score = − 2.646), O-linked glycosylation (z-score = − 2.236), Integrin cell surface interactions (z-score = − 2.236), SUMOylation of DNA damage response and repair proteins (z-score = − 2.236), and Parkinson’s Signaling Pathway (z-score = − 2). In contrast, significantly activated pathways at V24T0 vs. V2T0 included Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone Signaling (z-score = 2.236), Glycation Signaling (z-score = 1.633), AMPK signaling (z-score = 1.134), ERK/MAPK signaling (z-score = 0.447), and Protein Kinase A (PKA) signaling (z-score = 0.378). Notably, some of these pathways (e.g., AMPK, ERK/MAPK, PKA) are known to be activated by exercise and may contribute to exercise training-induced physiological adaptations50,51.

A comparison of peak exercise (T1) EV profiles between pre- and post-training (V24T1 vs. V2T1) identified 45 significantly regulated pathways (based on 189 regulated genes, p < 0.05) in serum EVs, including 12 activated and 33 inactivated pathways. Among the top inactivated pathways were those related to mitochondrial function and metabolism, such as tRNA processing in the mitochondrion (z-score = − 3), oxidative phosphorylation (z-score = − 2.648), mitochondrial RNA degradation (z-score = − 2.648), and respiratory electron transport (z-score = − 2.449). Additionally, immune-related pathways, including Neutrophil Extracellular Trap Signaling (z-score = − 1.414), autophagy (z-score = − 1.342), and IL-8 signaling (z-score = − 1.342), were significantly inactivated (Fig. 2B).

In addition, pathway analysis comparing peak exercise to rest before training (V2T1 vs. V2T0) identified 45 significantly enriched pathways (based on 269 regulated genes, p < 0.05), including 19 activated and 26 inactivated pathways (Fig. 2C). Among the most activated pathways were Processing of Capped Intron-Containing Pre-mRNA (z-score = 2.53), RNA Polymerase II Transcription (z-score = 2.236), RHO GTPases Activate Formins (z-score = 2.236), CDC42 Signaling (z-score = 2), and Mitotic G2-G2/M Phases (z-score = 2). In contrast, numerous immune-related pathways were inactivated during peak exercise (Fig. 2C). The top five inactivated pathways included Insulin Secretion Signaling (z-score = − 2.53), Cellular Effects of Sildenafil (z-score = − 2.236), Hereditary Breast Cancer Signaling (z-score = − 2.236), T Cell Receptor Signaling (z-score = − 2.121), and Autism Signaling (z-score = − 2).

Furthermore, after training, the response to acute exercise (V24T1 vs V24T0) was predominantly characterized by pathway inactivation, with 52 significantly regulated pathways (based on 718 regulated genes, p < 0.05), including 8 activated and 44 strongly inactivated pathways (Fig. 2D). The top activated pathways included Mitochondrial Dysfunction (z-score = 3), Parkinson’s Signaling Pathway (z-score = 2.887), Granzyme A Signaling (z-score = 2.646), RHOGDI Signaling (z-score = 2.236), and HER-2 Signaling in Breast Cancer (z-score = 2). Conversely, pathways related to mitochondrial function, metabolism, and the immune system were predominantly inactivated at peak exercise after training. Among these, the top five inactivated pathways were tRNA Processing in the Mitochondrion (z-score = − 4.123), rRNA Processing (z-score = − 3.873), Mitochondrial RNA Degradation (z-score = − 3.873), Neutrophil Extracellular Trap Signaling (z-score = − 3.464), and Oxidative Phosphorylation (z-score = − 3.464).

Discussion

This study examined the long RNA profiles of circulating EVs in individuals with long COVID to evaluate whether virus-related transcripts could be detected and whether acute exercise or exercise training alters EV-associated RNA profile, particularly involving immune and inflammatory pathways. Our findings provide new insights into the potential role of EV-associated RNAs in the pathophysiology of long COVID. Notably, we demonstrate for the first time that the RNA profile of circulating EVs undergoes significant changes in response to acute exercise following exercise training. Specifically, 53 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified at peak exercise compared to rest, including 3 upregulated and 50 downregulated genes, suggesting adaptations in the acute exercise response following exercise training in individuals with long COVID.

Lack of virus-related RNA in circulating EVs

Recent evidence suggests that EVs may act as carriers of SARS-CoV-2 or viral antigens, enabling viral dissemination and potentially contributing to viral persistence52,53,54. While EVs have been implicated in maintaining chronic infections and facilitating viral establishment in latent infections55,56, direct evidence of SARS-CoV-2 persistence or viral RNA within EVs from long COVID patients remains lacking. In the present study we did not detect any SARS-CoV-2 related RNA in serum EVs across all time points.

EVs as mediators of exercise adaptation

EVs play a crucial role in exercise-induced adaptations by mediating intercellular communication19,24,57. Previous research, particularly in rodent models, has demonstrated that circulating EVs can regulate metabolism46,58, modulate immune responses59, enhance muscle mass60, and promote recovery from myocardial injury61. In humans, EVs have also been linked to improved insulin sensitivity following high-intensity interval training (HIIT)62. Although we did not directly correlate specific EV RNA signatures with clinical outcomes in this study, we previously reported that patients in this cohort showed significant improvements in cardiopulmonary fitness, represented by increases in peak work rate (10.3%) and peak oxygen uptake (7.4%), as well as in patient-reported outcomes, including physical functioning and fatigue (60–63% improvement), depression (− 42%), anxiety (− 29%), and dyspnea (− 10%)10. This could be considered the first study linking exercise-induced EV RNA profiles to physiological adaptations in long COVID patients. However, because this study was a single-arm design without a control group, we cannot distinguish the effects of exercise training from spontaneous recovery or the passage of time. Nonetheless, these findings warrant further mechanistic investigation in controlled studies.

Downregulation of immune-associated genes in circulating EVs

For the first time, we demonstrated that the circulating EV RNA profile changed in response to acute exercise only after training, with a predominant downregulation of gene expression rather than upregulation in long COVID. This widespread downregulation of inflammation-associated genes suggests that exercise training may regulate immune activation in long COVID patients. Among the significantly downregulated genes at peak exercise were those directly (MYL9, NRGN, H2AC6, MAP3K7CL, B2M, CCL5, SNCA) or indirectly (MTND2P28, MT-ND1, MT-ND2, MT-ND3, MTRNR2, MT-RNR1, MT-ATP6) involved in immune activation and inflammation.

MYL9 (Myosin Light Chain 9), one of the most significantly downregulated genes, encodes a surface molecule expressed on activated T cells that serves as a ligand for CD69, a marker of activated immune cells. The interaction between MYL9 and CD69 is essential for the migration of activated T cells into inflammatory lesions and the induction of immune-driven diseases63,64. Moreover, MYL9 has been implicated in microthrombi formation in SARS-CoV-2-induced lung vasculitis, where its elevation correlates with disease severity65. Another strongly downregulated gene, NRGN (Neurogranin), encodes a protein primarily expressed in the brain, which plays a role in synaptic plasticity and neuroinflammation66,67. Notably, elevated NRGN levels have been observed in neuronal-enriched EVs of COVID-19 survivors, where they correlate with markers of neurodegeneration, including amyloid beta, neurofilament light, and total tau68. Other downregulated genes further support the hypothesis that exercise training modulates the immune response to acute exercise in long COVID. H2AC6, a histone variant, interacts with histone deacetylase 6 (HDAC6), a key inflammatory regulator, while B2M (Beta-2-Microglobulin) is essential for antigen presentation via MHC class I molecules69,70,71,72. The suppression of CCL5 (RANTES), a chemokine involved in immune cell recruitment, aligns with findings that its receptor, CCR5, plays a role in SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis. Importantly, blocking CCR5 using leronlimab restored immune homeostasis and reduced IL-6 levels in critically ill COVID-19 patients, suggesting that CCL5 suppression could mitigate prolonged immune activation in long COVID73,74. Furthermore, the downregulation of SNCA (Alpha Synuclein), a key protein in neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s disease, suggests a possible neuroprotective effect of exercise training. Recent evidence indicates that SARS-CoV-2 Spike and Nucleocapsid proteins interact with SNCA, accelerating its aggregation into Lewy body-like pathology, a hallmark of synucleinopathies75,76,77,78.

While 53 genes were differentially regulated in the EVs in response to acute exercise after exercise training, there were no changes in EV RNA profiles at rest (baseline) from pre- to post-training. The lack of DEGs in EV RNA profiles at baseline between pre- and post-training may indicate that the effects of exercise training on circulating EV cargo are context-dependent and may only be uncovered under physiological stress, such as during acute exercise19,79. This suggests that exercise training may not substantially alter resting EV RNA content but rather enhances the body’s ability to elicit a dynamic EV-mediated molecular response when challenged. Such findings align with the concept that exercise training improved physiological adaptability, which may not be detectable under resting conditions but becomes evident during exertion.

To further investigate the biological impact of the EV RNA profiles, we performed an Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) to identify differentially regulated (activated and inactivated) biological pathways influenced by gene expression changes at each time point. IPA was performed using genes identified at a nominal p value < 0.05, we note that many of these genes do not meet BH-adjusted significance thresholds. As such, the pathways identified should be interpreted as exploratory and hypothesis-generating rather than confirmatory. The inclusion of nominally significant genes increases sensitivity but also raises the possibility of overstating certain pathways. Therefore, these results should be viewed in the context of guiding future target validation rather than providing definitive mechanistic conclusions.

Interestingly, across all time points, the majority of pathways were inactivated rather than activated, indicating a general downregulation of molecular processes in response to both exercise training and acute exercise.

At rest after training compared to before training (V24T0 vs. V2T0), top significantly inactivated pathways included those related to transcription regulation (Generic Transcription Pathway), cell trafficking and metabolism (O-linked glycosylation), cellular adhesion and migration (integrin cell surface interactions), and DNA damage repair (SUMOylation of DNA damage response and repair proteins). Additionally, dopaminergic signaling (Parkinson’s Signaling Pathway), immune system activation and inflammation (STAT3 pathway and C-type lectin receptors), and vesicle formation and transport (COPII-mediated vesicle transport) were also significantly inactivated. Notably, 21 (e.g., STAT3, SAPK/JNK, PDGF, and C-type lectin receptor pathways) of the 44 inactivated pathways were directly or indirectly linked to inflammation, suggesting that their inactivation in response to acute exercise after exercise training may represent a beneficial immune-regulatory response. However, whether these pathway changes confer benefits in long COVID patients remains unclear, and with over 100 pathways regulated, further studies are required to determine their physiological significance.

Our findings of decreased inflammation-associated gene expression in circulating EVs- without changes in EV quantity- support the hypothesis that exercise mitigates systemic inflammation in chronic conditions17,80. This aligns with the concept that even an acute bout of exercise, if not prolonged and exhaustive, can transiently suppress pro-inflammatory signals, reflecting its broader anti-inflammatory effects in chronic inflammatory diseases18,21.

Exercise training and mitochondrial adaptations in long COVID

Pathway analysis also revealed distinct patterns of regulated pathways in response to acute exercise before and after training, despite comparable total numbers of regulated pathways. Before training, the top inactivated pathways in response to acute exercise included insulin secretion signaling, hereditary breast cancer signaling, T-cell receptor signaling, and G alpha (i) signaling events. In contrast, after training, the most inactivated pathways were related to mitochondrial function, including tRNA processing in the mitochondrion, rRNA processing, mitochondrial RNA degradation, neutrophil extracellular trap signaling, oxidative phosphorylation, and respiratory electron transport.

These findings align with our earlier observation that mitochondrially encoded genes were significantly downregulated in response to acute exercise following training. Mitochondrial dysfunction has been proposed as a key contributor to post-viral fatigue and systemic inflammation in long COVID81. The concurrent downregulation of mitochondrial pathways and gene expression suggests that, after training, fewer mitochondrial-derived RNAs are released into the extracellular space in response to exercise compared to pre-training. This indicates that a single bout of exercise after exercise training does not elicit an (extra) inflammatory response. While these genes primarily regulate respiratory complexes, they can also be released into the extracellular space via EVs and subsequently enter circulation, where they act as pathogen recognition receptor ligands- known as mitochondrial damage-associated molecular patterns (mtDAMPs)- recognized by macrophages and T cells, triggering ROS production and inflammatory pathways7,82,83,84,85,86,87. The reduced expression of mitochondrial genes post-exercise may reflect a transient shift in mitochondrial dynamics, facilitating mitochondrial repair and stabilization while potentially enhancing energy efficiency and reducing oxidative stress84,88. Given the role of mitochondrial dysfunction in long COVID, our findings suggest that exercise training promotes mitochondrial resilience and adaptation by modulating mitochondrial-related pathways84,88.

Upregulated genes and their potential role in long COVID

Three differentially expressed genes- ANK3, FTO, and FCN1- were significantly upregulated in circulating EVs of long COVID patients at peak exercise after training. ANK3 and FTO are predominantly expressed in the central nervous system, while FCN1 is found in monocytes/macrophages and neutrophils. While ANK3 and FTO help maintain axon initial segment and neuronal excitability (in neurons) and involved in cell signaling, possibly immune synapse formation, and RNA metabolism, especially energy balance (in other cells), mutations in these genes have been linked to psychiatric disorders (bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and autism spectrum disorder), obesity, and COVID-19 outcomes89,90,91,92. Similarly, FCN1, a key component of innate immunity, activates the lectin pathway of the complement system to promote microbial clearance93,94.

While these genes have been associated with acute COVID-19 infection95, their regulation by exercise remains poorly understood. Conflicting findings from preclinical models suggest that exercise may either upregulate or downregulate these genes, highlighting the need for further research96,97. Since Long COVID is frequently associated with neurological symptoms (e.g., brain fog), increased ANK2, FTO and FCN1 in EVs during acute exercise after training may suggest enhanced neuronal remodeling and vesicle-mediated signaling (ANK3), improved metabolic regulation and RNA turnover (FTO), and a shift toward controlled immune activation and resolution pathways (FCN1). Collectively, these changes may reflect a training-induced reprogramming of the systemic response to acute exercise, even in the absence of baseline changes, that potentially contributes to the restoration of homeostatic control across neuro-immune and metabolic-immune axes.

Study limitations

One limitation of this study is the lack of a platelet depletion step during serum preparation. Given that platelets can spontaneously release EVs or become activated ex vivo, they may significantly contribute to the EV RNA profile observed98. This could affect interpretation of EV-associated RNA signals in our study. Another limitation of the present study is that EV characterization was restricted to NTA, which assesses particle size and concentration but does not confirm EV identity or purity. Although complementary validation methods are recommended by the MISEV2023 guidelines99, this was not feasible due to limited sample availability. Furthermore, our study lacked a control group (either healthy individuals or those with prior SARS-CoV-2 infection without long COVID symptoms). Future studies should include healthy controls to better distinguish disease-specific changes from general exercise effects.

Conclusion

While no virus-associated RNA was detected in circulating EVs of long COVID patients, exercise training modulated the EV RNA profile in response to acute exercise, with a predominant downregulation of genes related to immune/inflammatory signaling and mitochondrial function. These findings suggest that EV-associated RNAs may not only serve as potential biomarkers of long COVID recovery but also act as functional mediators of systemic adaptation, highlighting the role of exercise training in reprogramming immune and metabolic responses to physiological stress in this population.

Data availability

Data are available with appropriate requests to the corresponding author.

References

Davis, H. E., McCorkell, L., Vogel, J. M. & Topol, E. J. Long COVID: Major findings, mechanisms and recommendations. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 21, 1740–1534 (2023).

Peluso, M. J. et al. Plasma-based antigen persistence in the post-acute phase of COVID-19. Lancet Infect. Dis. 24(6), e345–e347 (2024).

Proal, A. D. et al. SARS-CoV-2 reservoir in post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC). Nat. Immunol. 24(10), 1616–1627 (2023).

Swank, Z. et al. Persistent circulating severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 spike is associated with post-acute coronavirus disease 2019 sequelae. Clin. Infect. Dis. 76(3), e487–e490 (2023).

Nalbandian, A. et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat Med. 27(4), 601–615 (2021).

Buzas, E. I. The roles of extracellular vesicles in the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 23, 1–15 (2022).

Liao, Z. et al. Extracellular vesicles as carriers for mitochondria: Biological functions and clinical applications. Mitochondrion 78, 101935 (2024).

Chatterjee, S., Kordbacheh, R. & Sin, J. Extracellular vesicles: A novel mode of viral propagation exploited by enveloped and non-enveloped viruses. Microorganisms. 12(2), 274 (2024).

Gandham, S. et al. Technologies and standardization in research on extracellular vesicles. Trends Biotechnol. 38(10), 1066–1098 (2020).

Abbasi, A. et al. A pilot study on the effects of exercise training on cardiorespiratory performance quality of life and immunologic variables in long COVID. J. Clin. Med. 13(18), 5590 (2024).

Daynes, E. et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation for people with persistent symptoms after COVID-19. Chest 166(3), 461–471 (2024).

Gloeckl, R. et al. Practical recommendations for exercise training in patients with long COVID with or without post-exertional malaise: A best practice proposal. Sports Med. Open. 10(1), 47 (2024).

Amro, M., Mohamed, A. & Alawna, M. Effects of increasing aerobic capacity on improving psychological problems seen in patients with COVID-19: a review. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 25(6), 2808–2821 (2021).

Bargaje, M. D. et al. Effectiveness of pulmonary rehabilitation in post-COVID-19 patients: A pre- and post-interventional study. Lung India 41(6), 435–441 (2024).

Garbsch, R. et al. Sex-specific differences of cardiopulmonary fitness and pulmonary function in exercise-based rehabilitation of patients with long-term post-COVID-19 syndrome. BMC Med. 22(1), 446 (2024).

Chow, L. S. et al. Exerkines in health, resilience and disease. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 18(5), 273–289 (2022).

Gleeson, M. et al. The anti-inflammatory effects of exercise: mechanisms and implications for the prevention and treatment of disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 11(9), 607–615 (2011).

Nieman, D. C. & Wentz, L. M. The compelling link between physical activity and the body’s defense system. J. Sport Health Sci. 8(3), 201–217 (2019).

Nederveen, J. P., Warnier, G., Di Carlo, A., Nilsson, M. I. & Tarnopolsky, M. A. Extracellular vesicles and exosomes: Insights from exercise science. Front. Physiol. 11, 604274 (2020).

Le Bihan, M. C. et al. In-depth analysis of the secretome identifies three major independent secretory pathways in differentiating human myoblasts. J. Proteomics. 77, 344–356 (2012).

Catitti G, De Bellis D, Vespa S, Simeone P, Canonico B, Lanuti P. Extracellular Vesicles as Players in the Anti-Inflammatory Inter-Cellular Crosstalk Induced by Exercise Training. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(22).

Sullivan, B. P. et al. Obesity and exercise training alter inflammatory pathway skeletal muscle small extracellular vesicle microRNAs. Exp Physiol. 107(5), 462–475 (2022).

Chong, M. C. et al. Acute exercise-induced release of innate immune proteins via small extracellular vesicles changes with aerobic fitness and age. Acta Physiol. (Oxf). 240, e14095 (2024).

Whitham, M. et al. Extracellular vesicles provide a means for tissue crosstalk during exercise. Cell Metab. 27(1), 237–51.e4 (2018).

Safdar, A., Saleem, A. & Tarnopolsky, M. A. The potential of endurance exercise-derived exosomes to treat metabolic diseases. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 12(9), 504–517 (2016).

Fuller, O. K., Whitham, M., Mathivanan, S. & Febbraio, M. A. The protective effect of exercise in neurodegenerative diseases: The potential role of extracellular vesicles. Cells 9(10), 2182 (2020).

Vanderboom, P. M., Dasari, S., Ruegsegger, G. N., Pataky, M. W., Lucien, F., Heppelmann, C. J. et al. A size-exclusion-based approach for purifying extracellular vesicles from human plasma. Cell Rep. Methods. 1(3) (2021).

Perlis, R. H. et al. Prevalence and correlates of long COVID symptoms among US adults. JAMA Netw. Open. 5(10), e2238804 (2022).

Lee, J. et al. Hemodynamics during the 10-minute NASA lean test: Evidence of circulatory decompensation in a subset of ME/CFS patients. J. Transl. Med. 18(1), 314 (2020).

Miller, M. R. et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur. Respir. J. 26(2), 319–338 (2005).

Macintyre, N. et al. Standardisation of the single-breath determination of carbon monoxide uptake in the lung. Eur. Respir. J. 26(4), 720–735 (2005).

Wanger, J. et al. Standardisation of the measurement of lung volumes. Eur. Respir. J. 26(3), 511–522 (2005).

Graham, B. L., Brusasco, V., Burgos, F., Cooper, B. G., Jensen, R., Kendrick, A. et al. ERS/ATS standards for single-breath carbon monoxide uptake in the lung. Eur. Respir. J. 49(1) (2017).

Hankinson, J. L., Odencrantz, J. R. & Fedan, K. B. Spirometric reference values from a sample of the general U.S. population. Am. J. Respir. Cri.t Care Med. 159(1), 179–187 (1999).

Quanjer, P. H. et al. Lung volumes and forced ventilatory flows. Report Working Party Standardization of Lung Function Tests, European Community for Steel and Coal Official Statement of the European Respiratory Society. Eur. Respir. J. Suppl. 16, 5–40 (1993).

Cotes, J. E., Chinn, D. J. & Miller, M. R. Lung Function: Physiology, Measurement and Application in Medicine (Wiley, 2009).

Borg, G. A. Psychophysical bases of perceived exertion. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 14(5), 377–381 (1982).

Beaver, W. L., Wasserman, K. & Whipp, B. J. A new method for detecting anaerobic threshold by gas exchange. J. Appl. Physiol. 60(6), 2020–2027 (1986).

Cao, M. et al. Transcutaneous PCO(2) for exercise gas exchange efficiency in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. COPD 18(1), 16–25 (2021).

Stringer, W. W. et al. The effect of long-acting dual bronchodilator therapy on exercise tolerance, dynamic hyperinflation, and dead space during constant work rate exercise in COPD. J. Appl. Physiol. 130(6), 2009–2018 (2021).

Wasserman, K., Hansen, J. E., Sue, D. Y., Whipp, B. J. & Froelicher, V. F. Principles of exercise testing and interpretation. J. Cardiopulm. Rehabil. Prev. 7(4), 189 (1987).

Fujita, Y., Kosaka, N., Araya, J., Kuwano, K. & Ochiya, T. Extracellular vesicles in lung microenvironment and pathogenesis. Trends Mol Med. 21(9), 533–542 (2015).

Son, C. J., Carnino, J. M., Lee, H. & Jin, Y. Emerging roles of circular RNA in macrophage activation and inflammatory lung responses. Cells 13(17), 1407 (2024).

Eckhardt, C. M. et al. Extracellular vesicle-encapsulated microRNAs as novel biomarkers of lung health. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 207(1), 50–59 (2023).

Sundar, I. K., Li, D. & Rahman, I. Small RNA-sequence analysis of plasma-derived extracellular vesicle miRNAs in smokers and patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease as circulating biomarkers. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 8(1), 1684816 (2019).

Castaño, C., Mirasierra, M., Vallejo, M., Novials, A. & Párrizas, M. Delivery of muscle-derived exosomal miRNAs induced by HIIT improves insulin sensitivity through down-regulation of hepatic FoxO1 in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 117(48), 30335–30343 (2020).

Burke, B. I. et al. Extracellular vesicle transfer of miR-1 to adipose tissue modifies lipolytic pathways following resistance exercise. JCI Insight. 9, e182589 (2024).

Conkright, W. R. et al. Acute resistance exercise modifies extracellular vesicle miRNAs targeting anabolic gene pathways: A prospective cohort study. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 56(7), 1225–1232 (2024).

Doncheva, A. I. et al. Extracellular vesicles and microRNAs are altered in response to exercise, insulin sensitivity and overweight. Acta Physiol. (Oxf). 236(4), e13862 (2022).

Chen, H. et al. Exercise training maintains cardiovascular health: Signaling pathways involved and potential therapeutics. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 7(1), 306 (2022).

Spaulding, H. R. & Yan, Z. AMPK and the adaptation to exercise. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 84, 209–227 (2022).

Wang, C. et al. Long COVID: The nature of thrombotic sequelae determines the necessity of early anticoagulation. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 12, 861703 (2022).

Peluso, M. J. et al. SARS-CoV-2 and mitochondrial proteins in neural-derived exosomes of COVID-19. Ann. Neurol. 91(6), 772–781 (2022).

Tang, Z., Lu, Y., Dong, J. L., Wu, W. & Li, J. The extracellular vesicles in HIV infection and progression: mechanisms, and theranostic implications. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 12, 1376455 (2024).

Raab-Traub, N. & Dittmer, D. P. Viral effects on the content and function of extracellular vesicles. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 15(9), 559–572 (2017).

Pegtel, D. M. et al. Functional delivery of viral miRNAs via exosomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 107(14), 6328–6333 (2010).

Safdar, A. & Tarnopolsky, M. A. Exosomes as mediators of the systemic adaptations to endurance exercise. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 8(3), a029827 (2018).

Castaño, C., Kalko, S., Novials, A. & Párrizas, M. Obesity-associated exosomal miRNAs modulate glucose and lipid metabolism in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 115(48), 12158–12163 (2018).

Robbins, P. D. & Morelli, A. E. Regulation of immune responses by extracellular vesicles. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 14(3), 195–208 (2014).

Wu, Y. F. et al. Development of a cell-free strategy to recover aged skeletal muscle after disuse. J Physiol. 601(22), 5011–5031 (2023).

Bei, Y. et al. Exercise-induced circulating extracellular vesicles protect against cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury. Basic Res. Cardiol. 112(4), 38 (2017).

Apostolopoulou, M. et al. Metabolic responsiveness to training depends on insulin sensitivity and protein content of exosomes in insulin-resistant males. Sci. Adv. 7(41), eabi9551 (2021).

Nakayama, T. et al. CD4+ T cells in inflammatory diseases: pathogenic T-helper cells and the CD69-Myl9 system. Int. Immunol. 33(12), 699–704 (2021).

Hayashizaki, K. et al. Myosin light chains 9 and 12 are functional ligands for CD69 that regulate airway inflammation. Sci. Immunol. 1(3), eaaf9154 (2016).

Iwamura, C. et al. Elevated Myl9 reflects the Myl9-containing microthrombi in SARS-CoV-2-induced lung exudative vasculitis and predicts COVID-19 severity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 119(33), e2203437119 (2022).

Casaletto, K. B. et al. Neurogranin, a synaptic protein, is associated with memory independent of Alzheimer biomarkers. Neurology 89(17), 1782–1788 (2017).

Hellwig, K. et al. Neurogranin and YKL-40: independent markers of synaptic degeneration and neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 7, 74 (2015).

Sun, B. et al. Characterization and biomarker analyses of post-COVID-19 complications and neurological manifestations. Cells 10(2), 386 (2021).

Ran, J. & Zhou, J. Targeted inhibition of histone deacetylase 6 in inflammatory diseases. Thorac. Cancer. 10(3), 405–412 (2019).

Park, J. K. et al. Inhibition of histone deacetylase 6 suppresses inflammatory responses and invasiveness of fibroblast-like-synoviocytes in inflammatory arthritis. Arthritis. Res. Ther. 23(1), 177 (2021).

Muneshige, K. et al. β2-microglobulin alters the profiles of inflammatory cytokines and of matrix metalloprotease in macrophages derived from the osteoarthritic synovium. Cent. Eur. J. Immunol. 47(4), 332–338 (2022).

Yılmaz, B., Köklü, S., Yüksel, O. & Arslan, S. Serum beta 2-microglobulin as a biomarker in inflammatory bowel disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 20(31), 10916–10920 (2014).

Marques, R. E., Guabiraba, R., Russo, R. C. & Teixeira, M. M. Targeting CCL5 in inflammation. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets. 17(12), 1439–1460 (2013).

Patterson, B. K. et al. CCR5 inhibition in critical COVID-19 patients decreases inflammatory cytokines, increases CD8 T-cells, and decreases SARS-CoV2 RNA in plasma by day 14. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 103, 25–32 (2021).

Mahin, A. et al. Meta-analysis of the serum/plasma proteome identifies significant associations between COVID-19 with Alzheimer’s/Parkinson’s diseases. J. Neurovirol. 30(1), 57–70 (2024).

Massaro Cenere, M. et al. Systemic inflammation accelerates neurodegeneration in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease overexpressing human alpha synuclein. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 10(1), 213 (2024).

Limanaqi, F. et al. Alpha-synuclein dynamics bridge Type-I Interferon response and SARS-CoV-2 replication in peripheral cells. Biol. Res. 57(1), 2 (2024).

Wu, Z., Zhang, X., Huang, Z. & Ma, K. SARS-CoV-2 Proteins Interact with Alpha Synuclein and Induce Lewy Body-like Pathology In Vitro. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23(6), 3394 (2022).

Darragh, I. A. J., O’Driscoll, L. & Egan, B. Exercise training and circulating small extracellular vesicles: Appraisal of methodological approaches and current knowledge. Front Physiol. 12, 738333 (2021).

Lancaster, G. I. & Febbraio, M. A. The immunomodulating role of exercise in metabolic disease. Trends Immunol. 35(6), 262–269 (2014).

Molnar, T. et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in long COVID: Mechanisms, consequences, and potential therapeutic approaches. Geroscience. 46(5), 5267–5286 (2024).

Koupenova, M., Clancy, L., Corkrey, H. A. & Freedman, J. E. Circulating platelets as mediators of immunity, inflammation, and thrombosis. Circ Res. 122(2), 337–351 (2018).

Lee, J. H. et al. Mitochondrial double-stranded RNA in exosome promotes interleukin-17 production through toll-like receptor 3 in alcohol-associated liver injury. Hepatology 72(2), 609–625 (2020).

Hough, K. P. et al. Exosomal transfer of mitochondria from airway myeloid-derived regulatory cells to T cells. Redox Biol. 18, 54–64 (2018).

Riley, J. S. & Tait, S. W. Mitochondrial DNA in inflammation and immunity. EMBO Rep. 21(4), e49799 (2020).

Sriram, K. et al. Regulation of nuclear transcription by mitochondrial RNA in endothelial cells. Elife 13, e86204 (2024).

Di Florio, D. N., Sin, J., Coronado, M. J., Atwal, P. S. & Fairweather, D. Sex differences in inflammation, redox biology, mitochondria and autoimmunity. Redox Biol. 31, 101482 (2020).

Robbins, J. M. & Gerszten, R. E. Exercise, exerkines, and cardiometabolic health: from individual players to a team sport. J. Clin. Invest. 133(13), e168121 (2023).

Hughes, T. et al. Elevated expression of a minor isoform of ANK3 is a risk factor for bipolar disorder. Transl. Psychiatry. 8(1), 210 (2018).

Gerken, T. et al. The obesity-associated FTO gene encodes a 2-oxoglutarate-dependent nucleic acid demethylase. Science 318(5855), 1469–1472 (2007).

Hubacek, J. A., Capkova, N., Bobak, M. & Pikhart, H. Association between FTO polymorphism and COVID-19 mortality among older adults: A population-based cohort study. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 148, 107232 (2024).

Yoon, S., Piguel, N. H. & Penzes, P. Roles and mechanisms of ankyrin-G in neuropsychiatric disorders. Exp. Mol. Med. 54(7), 867–877 (2022).

Endo, Y., Matsushita, M. & Fujita, T. Role of ficolin in innate immunity and its molecular basis. Immunobiology 212(4–5), 371–379 (2007).

Frederiksen, P. D., Thiel, S., Larsen, C. B. & Jensenius, J. C. M-ficolin, an innate immune defence molecule, binds patterns of acetyl groups and activates complement. Scand. J. Immunol. 62(5), 462–473 (2005).

Sheerin, D., Abhimanyu, Wang, X., Johnson, W. E., Coussens, A. Systematic Evaluation of Transcriptomic Disease Risk and Diagnostic Biomarker Overlap Between COVID-19 and Tuberculosis: A Patient-Level Meta-Analysis. medRxiv. 2020.

Liu, S. J. et al. Long-term exercise training down-regulates m(6)A RNA demethylase FTO expression in the hippocampus and hypothalamus: An effective intervention for epigenetic modification. BMC Neurosci. 23(1), 54 (2022).

Sorensen, B., Jones, J. F., Vernon, S. D. & Rajeevan, M. S. Transcriptional control of complement activation in an exercise model of chronic fatigue syndrome. Mol. Med. 15(1–2), 34–42 (2009).

McIlvenna, L. C. et al. Single vesicle analysis reveals the release of tetraspanin positive extracellular vesicles into circulation with high intensity intermittent exercise. J. Physiol. 601(22), 5093–5106 (2023).

Welsh, J. A. et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles (MISEV2023): From basic to advanced approaches. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 13(2), e12404 (2024).

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication included work performed in the Collaborative Sequencing Center at TGen, and the Integrated Mass Spectrometry Shared Resource supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under grant number P30CA033572. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Funding

This study was supported by the Pulmonary Education and Research Foundation and the UCLA David Geffen School of Medicine (DGSoM)-Ventura County Community Foundation (VCCF) Long COVID 19 Research Award.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Asghar Abbasi contributed to conceptualization, methodology, validation, investigation, resources, data curation, writing original draft, writing—review & Editing, visualization, supervision, project administration and funding acquisition. Nathaniel Hansen was involved in formal analysis, data curation, writing—review & editing and visualization of this manuscript. Joanna Palade was involved in formal analysis, data curation, review & editing and visualization of this manuscript. Dorothy Paredes was involved in formal analysis, data curation, review & editing and visualization of this manuscript. Bessie Meechoovet was involved in formal analysis, data curation, review & editing and visualization of this manuscript. Van Keuren-Jensen was involved in methodology, review & editing, visualization of this manuscript. Patrick Pirrotte was involved in methodology, review & editing, and visualization of this manuscript. William W Stringer contributed to conceptualization, methodology, validation, investigation, data curation, writing original draft, writing—review & editing, visualization, supervision of the study and this manuscript, project administration and funding acquisition.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Asghar Abbasi is supported by TRDRP (28FT-0017), NIH (R43HL167289, 2R44HL167289-02, 5R44HL167289-03), and the Johnny Carson Foundation. William Stringer receives research foundation support from the Pulmonary Education and Research Foundation and the UCLA David Geffen School of Medicine (DGSoM)-Ventura County Community Foundation (VCCF) Long COVID 19 Research Award. He reports consulting fees from Verona, Genetech, and Vyaire. He is the co-author of a clinical exercise testing physiology textbook for Lippincott.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abbasi, A., Hansen, N., Palade, J. et al. Serum extracellular vesicle RNA profiles in long COVID: insights from exercise-induced gene modulation. Sci Rep 16, 3469 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23760-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23760-y