Abstract

In response to the global push for net-zero emissions, the automotive industry faces challenges from the environmental impact of traditional oil-based shock absorbers, as vehicle production in Europe consumes around 9000–9500 tons of hydraulic oil annually. Our research introduces an innovative shock-absorber that employs a Heterogeneous Lyophobic System (HLS) to replace hydraulic oil with a nonwetting liquid (NWL) and hydrophobic nanoporous materials (PMs). This system not only eliminates oil use but also enables the tuneability of the vehicle shock-absorber’s performance. By focusing on the dynamic intrusion/extrusion process, we developed a CFD-coupled model demonstrating how the adjustment of damping characteristics can be achieved, catering to a broad spectrum of vehicular requirements. The core of this study lies in its ability to simulate the patterns of intrusion and extrusion, including complete, partial cycles, and double-step cycles, thereby demonstrating both the practical applicability and theoretical foundation of using such mechanisms in shock-absorber design. With a strong correlation between experimental and simulation data, the current study not only underpins the accuracy of the developed theoretical and CFD models but also allows for the customisation of the shock-absorber performance under assorted conditions, laying a solid groundwork for future technological advancements in this field. Overall, this work provides a practical modelling framework that can guide the industrial design of next-generation sustainable shock-absorbers and broader adaptive damping systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The quest for a net-zero society has become a global imperative, driven by the urgent need to combat climate change and mitigate its extensive impacts. In the transportation sector, car shock-absorbers typically rely on oil-based systems. According to data from the past five years, Europe produces between 17 and 18 million vehicles each year1. Considering each vehicle is equipped with four shock-absorbers and each shock-absorber requires 150 ml of hydraulic oil, this results in an annual consumption of about 9000–9500 tons of oil. Recycling this substantial volume of oil presents considerable challenges due to issues like contamination, chemical degradation, cost constraints, the need for specialised equipment, and regulatory compliance2,3. Addressing these sustainability challenges, we have developed a new type of shock-absorber that achieves damping without the use of hydraulic oil.

Recent progress in tunable dampers has mainly focused on magnetorheological (MR) systems and electronic valve control. MR dampers adjust fluid viscosity under a magnetic field, offering rapid response but requiring continuous power and specialised fluids. Electronic valve dampers regulate flow through actuated valves, providing adaptive performance but depending on complex electronics. In contrast, the present study introduces a passive, design-stage tunable shock absorber based on nanoporous materials and non-wetting liquids. Its damping behaviour is tailored through material selection, requiring no sensors, control units, or power input, offering a simpler and more sustainable alternative.

The energy dissipation principle explored in this work is based on a Heterogeneous Lyophobic System (HLS), which is attributed to the intrusion-extrusion behaviour of a non-wetting liquid (NWL) such as water interacting with hydrophobic porous material (PM, grafted silica, in this case)4,5,6,7,8,9,10. As shown in this work, such principle, not only allows virtually oil-free shock-absorbing, but also offers a high degree of tunability by exploiting nanoporous materials of different characteristics in a single device. Moreover, such shock-absorber can harvest both heat from environment and mechanical energy from vibrations, converting these into electricity through triboelectrification6,11,12,13, thus serving as a regenerative shock absorber14,15,16. This breakthrough has the potential to dramatically reduce the environmental impact of the automotive industry while pushing forward the boundaries of green technology in transportation. While recent advances in HLS research (see Table 1) have explored sophisticated porous frameworks, e.g. MOFs and ZIFs, with tunable intrusion and separation behaviour17,18,19 to enhance performance, the present study is a computational investigation of a foundational silica–water HLS, serving as a baseline platform rather than presenting a materials innovation.

As a first step towards HLS-based regenerative shock absorber, in this work, we developed and validated a CFD model that captures the performance and tunability of the shock absorber based on water intrusion-extrusion cycle into-from grafted nanoporous silica20,21,22. The CFD model was created using COMSOL Multiphysics 6.1 software focusing on the internal structure of the developed shock-absorber prototype with dual working chambers and corresponding buffer sacs23,24,25. Its effectiveness and the accuracy of the CFD modelling were verified by conducting comparisons with actual experimental results, ensuring the model’s reliability and applicability. The validated CFD modelling, integral to the broader electro-intrusion project5, guides the dimensional optimisation of the regenerative shock-absorber, ultimately to complete the puzzle by merging theory with practical application.

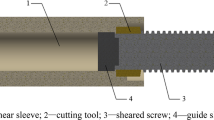

Design and operation

An assembly drawing for the shock-absorber prototype is shown in Fig. 1, schematic conceptual diagram can be found in20. A hollowed piston rod 1 situated inside a cylinder 3. The rod is divided by piston head 2, into two internal chambers 1–1 and 1–2, where mixture of PM and NWL are filled inside. Capsules 5–1 and 5–2 contain the PMs from spreading into the working chambers 7–1 and 7–2. At the top of the prototype, the working chambers connect to a compensation chamber 8, through two check valves 9–1 and 9–2, whose closure is adjustable by two corresponding screw throttles 10–1 and 10–2. Details about how the check valves work can be found in supplementary materials. Hydraulic fluid, i.e. water in this study, is filled outside the capsules in the closed space formed by components 6–1, 6–2, 7–1, 7–2, and 8. The upper and bottom mounts 12 and 13 are the screws that connect the wheel and vehicle body when the suspension is practically installed.

Schematic diagram of (a) the HLS-based shock-absorber and (b) corresponding liquid flow paths, reproduced from20.

The initial position of piston head (No.2 component) is set to a balance position at the centre, although the piston can move along its available range. For instance, during the process as the piston moves to the right from the balance position, the flow of hydraulic fluid is impeded by the throttling mechanism while passing through the restricted gap controlled by screw 10–2. The obstruction effect becomes significant as the velocity raises, which causes increased pressure in chambers 1–2 and 7–2 (marked as red in Fig. 1(b). The intrusion process starts when the pressure in 7–2 exceeds the threshold. By contrast, the pressure in chambers 1–1 and 7–1, remains unchanged in this duration because of the open check valve 9–1, which allows the liquid to flow smoothly back to internal chamber 7–1 from compensation chamber 8. Therefore, the pressure in chambers 1–1 and 7–1, remains close to the ambient pressure p0 (marked as blue in Fig. 1(b). When the piston returns (leftwards) after reaching the right end, check valve 9–1 closes promptly. The evolution of the fluidic pression in chambers 1–1 and 7–1, is the same as what occurred in chambers 1–2 and 7–2 during the piston’s rightward motion. Meanwhile, for the right-hand side, check valve 9–2 stays closed for a period because positive pressure still presents in chamber 7–2. The pressure gradually decreases along with the piston moves towards left and, momentarily, falls below the extrusion critical pressure thus initiating the extrusion process. Then, valve 9–2 opens when the pressure in chamber 7–2 approaches to p0.

Modelling methods

The detailed methodology related to CFD-coupled modelling is introduced in this section. To maintain the minimal consumption of computational resource, a simplified 2D symmetric model is created based on the prototype of the HLS-based shock-absorber Fig. (1). Three simplified measures have been adopted in modelling: (i) The buffer tank is omitted, leaving two open boundaries where an ambient pressure condition is applied. (ii) Specific boundary conditions are implemented to imitate the valve functionality as in actual operation rather than considering the intricate valve structure. The operation of the check valves is briefly summarised here, while their detailed structural description is provided in the Supplementary Material (Figure S3). (iii) The model focuses on fluid domain only. Three coupling physical phenomena have been simulated in the modelling: the thermodynamic properties of HLS during intrusion and extrusion process; the dynamic behaviour of the fluid flow domain in the prototype shock-absorber; and the evolution of mechanical stress caused by the movement of the piston and the on/off action of check valves.

A semi-empirical macroscopic approach was employed to investigate the intrusion and extrusion mechanism occurring at the interfaces of PMs and NWL. The HLS, including the PMs, NWL, and the capsule, was regarded as a homogenous continuum medium that can be described by a specific set of the dynamic parameters. According to our previous work26, the thermodynamic state of HLS can be described by the following equations:

or

where, vpore is the volume of the pores for per unit mass of solid particles, pi,e is the intrusion/extrusion pressure, D is the dispersion of the values of pi,e, vb is the total body volume consisting of liquid (vl) and solid (vs) phases, and C is a constant that is related to the initial state of pressure p0 and temperature T0.

These parameters of Eq. (1) can be determined by experiments for specific PMs and NWL. Based on our previous experimental approaches, the temperature at the surface of device increased less than 7 °C during the test of 260 cycles20. Thus, the current model is considered as an isothermal system, and the temperature-related terms from the constitutive equation (Eq. (1b)) are neglected. Hence, the expression for the overall volume variation of HLS can be written as:

where ∆v is solely dependent on the gauge pressure of the HLS. On the RHS of Eq. (2), the first term represents the volume variation upon NWL intrusion into or extrusion from the micropores of PMs, and the second term accounts for the compressibility of the HLS capsule, non-wetting liquid and nanoporous material.

To integrate the Eq. (2) into the numerical simulation, an apparent density concept for the HLS is introduced. Figure 2 illustrates the overall volume changes during intrusion/extrusion at the macroscopic scale. NWL in terms of ml is mixed with PMs (ms) within a closed chamber. For the initial phase (Fig. 2a), the volume of HLS is V = V0 when the pressure is at zero pascal, and the initial apparent density equals \({\rho }_{0}=\frac{{m}_{l}+{m}_{s}}{{V}_{0}}\). As the piston moves downwards (or upwards), water is intruded into (or extruded out from) the pores of the PMs. Therefore, the apparent density of HLS (ρapp) can be derived as Eq. (3):

where mR is the mass ratio of PMs to HLS, ∆v has already given by Eq. (2).

Consequently, the general governing equations for representing the fluid flow velocity field (u) can be written as:

Continuous equation

and Navier–Stokes equations for laminar flow:

where μ represent the dynamic viscosity of HLS; F represents the item of force resulting from the displacement of the piston.

Additional technical details about building the simulation, in terms of moving mesh model (Section S1), boundary conditions (Section S2), check valve operation (Section S3), and verification of laminar flow condition (Section S4), are provided in the Supplementary Materials. A key assumption in the present model is that the working fluid behaves as a Newtonian liquid. Although literature reports non-Newtonian behaviours in fluid dampers, its influence is considered negligible in the proposed configuration for two reasons. First, in conventional dampers the primary energy dissipation mechanism relies on viscous shear across an annular thin gap between the piston rod and the cylindrical wall, where high shear rates make non-Newtonian behaviour significant. In contrast, the current design eliminates such annular gap structures and implements check valves as flow restrictors. Therefore, reversible compressibility and convective transport, rather than irreversible viscous dissipation, govern the fluid behaviour in this model; Second, the working fluid is a novel PM–NWL mixture with a moderate concentration (~ 43 wt% or ~ 26 vol%) in place of highly viscous silicone oils (e.g. 500,000 cSt). Silica suspensions have been reported to behave nearly Newtonian at solid volume fractions below ~ 30 vol%27. To verify this assumption, additional simulations are performed using a non-Newtonian viscosity model and compared against the Newtonian reference case, as detailed in Section S4.

Results and discussion

Thermodynamic description of HLS

The parameters defined in Eq. (2) are first estimated by the experimental data for HLS, which are extracted from20. Theoretically, an isotherm intrusion-extrusion cycle consisting of four segments, in terms of isochoric compression, isobaric intrusion (upper horizon), isochoric expansion, and isobaric extrusion (lower horizon), would form a rectangle loop in the p–v diagram as illustrated in Fig. 3a inclusive. The point ‘pint’ (or ‘pext’) represents the criterion for the beginning of the intrusion (or extrusion) process. However, in practical terms (circled data sequence and red solid curves in Fig. 3a), because the sizes of pores are not uniform and both PMs and NWL are deformable, four segments may not be strict straight lines but rather curves that includes smooth transient zones. Consequently, the criterion ‘pint’ (or ‘pext’) can only serve as a reference threshold for intrusion (or extrusion). Instead, the actual intrusion (or extrusion) process takes place within a pressure range above and below this ‘threshold’. The experimental data in Fig. 3a elaborates the p − v isotherm diagram of the HLS consist of silica gel—water at 25 °C. From the origin of the coordinate, the slope of the inclined line which corresponds to the pressure rise due to compression is determined by (dvb/dp). During the following intrusion process, the state of HLS along the upper curve as the increase of both pressure p and absolute volume difference |Δv|. The maximum can be read as 45 MPa and 0.55 cm3/g approximately, which corresponds to the full intrusion process. After that, the state of HLS returns to the origin of coordinates along a pressure drop route followed by the extrusion process (lower curve). The volume of pores per gram of solid, vpore, is represented by the horizontal distance between the two inclined lines. The values for those parameters which derived from experimental results20,21 are given in Table 2.

Under real-world working conditions, vehicle shock absorbers may not reach the maximum pressure of 45 MPa (or the maximum volume difference of 0.55 cm3/g) with every cycle. As a result, full intrusion (or extrusion) on each compression (or extension) is not always achieved. For instance, if the wheel hit a large protrusion on the road which makes the shock-absorber reaching the instant working scenario of X0 = 30 mm (amplitude), f = 3 Hz (frequency), the peak pressure of the hydraulic fluid would be approximate 22 MPa only. It means that the pressure increases follow the upper curve (intrusion), when reaches 22 MPa, the pressure drops down following another parallel route back to origin, see incomplete cycle routes shown in Fig. 3b. These parallel incomplete extrusion routes can be regarded as the shift leftwards of the full extrusion route. To quantitatively describe such a shift of the extrusion curve, we defined a parameter called the intrusion rate: χ = vpore,int/vpore which denotes to the ratio of the intruded porous volume to the overall volume of pores. In Fig. 3b, as the parameter χ varies from 1 to 0, the extrusion route moves horizontally closer to the intrusion curve, while the enclosed loop area gradually reduced. The value of χ is significantly dependent on both the amplitude of the piston X0 and the instant frequency f. For example, with an amplitude of X0 = 30 mm and a frequency of f = 3 Hz, the estimated value of χ is 0.79. However, the value of χ drops to just 0.1 when X0 and f are reduced to 20 mm and 1 Hz, respectively.

Alternating pressure in dual working chambers

According to the structural design of the shock-absorber shown in Fig. 1 and the explanation of the operational concept which has introduced in section “Design and operation”, the pressure inside the working chambers (7–1 and 7–2) are swinging while the shock-absorber in its periodic working condition, as shown in Fig. 4a. The x-axis charts the sequence of time (0.7 s), encompassing two cycles of piston movement with the operation conditions at X0 = 30 mm and f = 3 Hz.

(a) Alternating pressure in the chambers (7–1 and 7–2). (b) Differential pressure between the chambers (7–1 and 7–2). These two data from these two sub-figures are based on the same condition of amplitude (X0 = 30 mm) and frequency (f = 3 Hz). The Stage I and II are precisely aligned on their respective x-axes, ensuring exact temporal consistency between the two stages across these two sub-diagrams.

Specifically focusing on the half cycle of the pressure data from chamber 7–1 (solid curve in Fig. 4a), it can be further divided into two stages: Stage I (hatching shadow area) starts at a pressure of 14 MPa corresponding to the start of intrusion process. It ends at the peak pressure of 21.5 MPa corresponding to the terminate of the intrusion process. Then, the pressure drops following incomplete cycle routes from the peak to 3 MPa (pext) in the Stage II (stippled shadow area). Neither intrusion nor extrusion occurs in chamber 7–1 during this stage, corresponding to the “pressure drop” segment illustrated in Fig. 3a inclusive. After the Stage II, extrusion process starts in chamber 7–1 until the pressure further drops to zero. For the pressure data from chamber 7–2 (dash-dot curve in Fig. 4a), it decreases from 3 MPa to zero in the Stage I (hatching shadow area) which corresponds to the extrusion process. Similarly, neither intrusion nor extrusion occurs in chamber 7–2 during the Stage II (stippled shadow area). Stage I and Stage II respectively occupies 65% and 35% of the half cycle. The subsequent half cycle mirrors the pattern described above, but with the evolutions of the two chambers reversed.

Figure 4b depicts the relationship between the differential pressure across the two working chambers (7–1 and 7–2) and the simple harmonic displacement of the piston, synchronized with time. As a concise comparison, both the modelling (red solid curve) and experimental data (circle data sequence) are highly agreed, evidenced by an R-squared value of 0.929. This demonstrates strong consistency and confidently validates the model. Due to the presence of the intrusion/extrusion process, there is a phase difference between the variance of differential pressure (Δp) and the piston’s position (X) over time. The peaks of differential pressure |Δp|max precedes the moment when the piston head reaches its maximum displacement (± X0). When Δp is zero, the piston is positioned at two-thirds of the amplitude away from its equilibrium position. In the Stage I (hatching shadow area), the piston travels from a position of X = − 20 mm to X = 30 mm, achieving a total displacement of 50 mm. During this phase, the differential pressure (Δp) climbs from 14 MPa to its peak at 21.5 MPa, only 7.5 MPa in pressure increase. This is attributed to the intrusion of liquid into the micropores of the PMs, which effectively absorbs the compressive energy from piston movement, thereby reducing the rate of the pressure increase in the chamber 7–1. Stage II presents a different scenario, where neither intrusion nor extrusion takes place. Here, a trend opposite to Stage I is observed between piston displacement and differential pressure. In this stage, differential pressure (Δp) undergoes a substantial drop of 33 MPa from its peak, falling to − 11.5 MPa, a result of decreasing pressure in the chamber 7–1 and increasing pressure in the chamber 7–2. Simultaneously, as the piston slows down approaching the limit, it exhibits a modest displacement of just 11 mm.

Damping performance of the shock-absorber

Hysteresis loop diagram, expressed as the circular behaviour of force–displacement, is commonly used to evaluate the performance of a shock-absorber, in terms of the damping characteristics and the energy dissipation during its operation. Based on the simulation model built for the HLS shock-absorber presented in this study, such hysteresis loops have been generated as red curves in Fig. 5a, under various working scenarios with the amplitude of piston X0 ranging from 10 to 40 mm and the frequency f at 1 and 1.5 Hz. Corresponding experimental data with same working scenarios that captured from literature20, have been also plotted as black data sequences for comparison. The outermost circles, illustrated in black squared marks (X0 = 40 mm and f = 1 Hz), demonstrate the peak hydraulic force at 78 daN from experimental results, and 70 daN from modelling. Similarly, the peak hydraulic force for X0 = 30, 20, 10 mm are respectively read as 71, 68, and 36 daN from experiments, and 67, 63, and 31 daN from numerical simulation. The results from simulation and experiment are well aligned in the first and second quadrants of the hysteresis loop, which approximately represents half of the cycle in the operation of the shock absorber. The mismatch between experimental and simulation data in the other two quadrants is because the experimental curves present obviously asymmetric feature. To achieve the same amplitude, the piston head experiences a higher force when compressing the lower working chamber (7–2 in Fig. 1) than when extending from it. As the piston approaches its lowest positions (X = − 40, − 30, − 20 mm), the experimental peak hydraulic forces reach − 98, − 80, and − 75 daN, respectively, representing increases of 26%, 13%, and 10% compared with the peak values measured during the opposite motion (X = 40, 30, 20 mm) at a frequency of 1 Hz. This asymmetry likely originates from two reasons: (1) the two working chambers (7–1 and 7–2 shown in Fig. 1) within the prototype shock-absorber not being identical due to variations in manufacturing; (2) an inherent systematic force caused by gravity during experimental operations when the shock-absorber is vertically installed. However, due to the limitations of the present model, these explanations remain speculative and require further investigation.

Comparison of results from simulation and experimental data in terms of (a) Hysteresis loop diagram under conditions of X0 = 10, 20, 30, 40 mm, and frequencies f = 1 and 1.5 Hz. The simulation results exhibit symmetry about the origin, whereas the experimental loops show slight asymmetry, mainly due to chamber non-uniformity and measurement effects. (b) Force–velocity diagram under condition of X0 = 30 mm. The experimental data are extracted from20.

The curve labelled 1 − 2 − 3 within a single loop in Fig. 5a represents a half cycle of the piston’s harmonic motion, with segments 1 − 2 and 2 − 3 denoting Stage I and Stage II, respectively. For the scenarios with amplitudes of 20, 30, and 40 mm and a frequency of 1 Hz, both curves from experimental and modelling results exhibit a ‘plateau region’ in segment 1 − 2, which indicates the feature of intrusion process. For a given frequency, a decrease in amplitude results in a narrower plateau region. During the process of reducing the amplitude from 40 to 30, the width of the plateau region decreased from 44 mm (ranging from X = − 6 mm to X = 38 mm), to 29 mm (ranging from X = − 1 mm to X = 28 mm). However, as the amplitude further decreases, the width of the plateau region can hardly be identified when the amplitude X0 = 20 mm. The intrusion/extrusion process has vanished for the scenario with X0 = 10 mm, f = 1.5 Hz.

To evaluate the damping characteristic of the shock-absorber, in terms of the relationship between the damping force exerted by the shock-absorber and the velocity of the piston movement, a force–velocity diagram has been plotted in Fig. 5b. The dimensionless force on the vertical axis denoted as F/F0, indicates the ratio between the maximum force F and the critical force F0, where the critical force is defined as the turning point at which intrusion occurs in one chamber, corresponding to the pint theoretically. Figure 5b compares the curves plotted based on simulation (red solid line) and experimental data (circled marks), under the condition of amplitude X0 = 30 mm. In experiments, the critical force F0 is measured at 70 daN approximately at the piston velocity of uc,exp = 0.08 m/s. Those values generated from modelling are at F0 = 66 daN, and uc,sim = 0.066 m/s, respectively.

The damping characteristic graph illustrated in Fig. 5b can be divided into two regions by the critical piston velocity, for instance 0.08 m/s. In the low-velocity region, e.g. u < 0.08 m/s, both the experimental and simulation curves exhibit a soar with the increase of piston velocity. At microscale, the fluid pressure generated by the piston’s slow motion is insufficient to overcome the hydrophobic repulsion at the NWL-PM interface, preventing the NWL from entering the micropores of the PMs. Thus, the HLS exhibits similar properties to regular hydraulic oil or water with the nearly incompressible mechanical property. As the piston velocity further increases, e.g. u > 0.08 m/s, the instant force F surpasses the critical threshold F0, thereby initiating the intrusion process. From this point forward (high-velocity region), the NWL can intrude into the micropores of the PMs via their hydrophobic interfaces. Consequently, the mechanical energy of compression drives the intrusion process, leading to triboelectrification at the solid–liquid interface inside the micropores/channels and, thereby, generating electricity4. In this high velocity region, the dimensionless force F/F0 is less sensitive to the change of the piston velocity u, because the mechanical force resulted from the piston’s compression is effectively released as the NWL intrudes into pores through the interface, rather than being accumulated within the liquid bulk. Quantitatively, the slope of both the experimental and simulation curves in the low-velocity region is calculated to be 12.5. This is over 40 times greater than the slope of the experimental curve in the high-velocity region, and over 96 times greater than that of the simulation curve in the same high-velocity region.

In the high-velocity region, there’s a noticeable difference between the simulation and experimental curves, likely due to the friction and/or inertial force present in the actual movement of the piston, which is not accounted for in the simulation model. Consequently, in the experiments, a greater force is required to achieve the same piston velocity as in the simulations. Overall, the above results validate the CFD model against experimental data and highlight its limitations, such as asymmetry in the experimental hysteresis loops and the absence of frictional effects in the simulation. Building upon this validated framework, we next consider a more speculative perspective on industrial application through a double-step intrusion/extrusion approach.

Speculative industrial application: double-step intrusion/extrusion

The primary function of a suspension system is to isolate the vehicle from road disturbances while maintaining stability. A passive suspension will always be a trade-off between the two. Typical characteristics expected are soft damping with high speed improving comfort (ride on highways) and high damping with low speed improving handling (cornering reducing roll angle or breaking reducing pitch). The results in previous sections demonstrate realistic damping behaviours achievable with shock-absorbers with HLS system, highlighting how these can be fine-tuned based on the material characteristics. It could be interesting from an industrial point of view: by tuning the composition of a mix of PMs (with different size of micropores) capable of producing varying levels of intrusion/extrusion pressures, it’s possible to achieve a single shock-absorber that integrates both soft and hard damping characteristics, automatically switching between them based on operating conditions. Practically, such tuneability enhances the shock-absorber to meet specific requirement on the damping performance goals. Consequently, this adjustment reflects mathematically as modifications in Eq. (2). For instance, a double-step of intrusion/extrusion can be written as the equation shown in Eq. (6) below:

where vpore and vpore2 represent two types of PMs with different volume of the pores for per unit mass. pi,e and pi,e2 are the individual intrusion/extrusion pressures of the two types of PMs respectively. Thus, incorporating the second type of PMs into the HLS mixture can tune the shock-absorber’s dynamic performance through changing the shape of the hysteresis loop, in terms of damping force vs. piston displacement. Figure 6 compares one single loop (same one from Fig. 5a, parameters from Table 2) and two double-step loops with different parameters (displayed in Table 3). The parameters used in the first step of the two double-step loops are the same as those in the single-step loop. The second step utilises narrower range between the intrusion and extrusion pressures (pint − pext). This adjustment flattens the middle of the originally almond-shaped hysteresis loop, transforming it into a peanut-shaped double-step loop in the performance of the shock absorber. This transformation is consistent with the context of ‘soft damping with high speed’. This enhancement, if implemented in vehicles, will significantly improve ride quality and stability under high-speed conditions, effectively absorbing impacts and reducing vibrations. Consequently, this tailored shock absorber performance not only extends the longevity of vehicle components but also enhances passenger comfort during a wide range of driving scenarios.

It’s worth to noting that, the feasibility of the double-step tuning is subject to practical materials challenges, such as mixture stability, particle interactions, and packing effects, which are not considered in the present CFD model. These aspects warrant a dedicated study as future work.

Conclusion

This study has successfully demonstrated the feasibility of a shock-absorber for vehicles that leverages the dynamic interaction between nonwetting liquids and hydrophobic nano-porous materials through an intrusion/extrusion process, enabling tuneable damping performance. Through simulating the intrinsic principles governing this process and a comprehensive investigation into the patterns of the intrusion/extrusion interactions, including full or incomplete intrusion/extrusion cycles, this work has proved the theoretical underpinnings and practical applications of utilising this mechanism in the design of effective damping systems. The comparison between experimental data from a patented prototype shock absorber and simulation data highly agrees, as evidenced by an R-squared value of 0.929, further reinforcing the validity and accuracy of our theoretical and CFD models. The performance of shock-absorber, in terms of hysteresis loop and damping characteristics, have also been thoroughly investigated. Considering the practical requirements of shock absorbers (e.g., the shape and thresholds of the hysteresis loop), our developed simulation model serves as a tool that allows for the customisation of shock absorber performance by adjusting the proportions of various porous materials in the Heterogeneous Lyophobic System (HLS). This enables us to meet the diverse and customized needs of shock absorbers. It highlights the robustness and potential of the developed simulation model and methodologies in predicting and designing the behaviour of the shock-absorber under various conditions, providing a solid foundation for future advancements in this technology. These results provide guidance for the industrial translation of HLS-based dampers into automotive suspension design, while also opening new avenues for future research on advanced porous materials and durability under dynamic loading.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

International organization of motor vehicle manufacturers. World motor vehicle production n.d. (accessed April 18, 2024).

Parashar V, Thakur C. Challenges, Opportunities, and strategies for effective petroleum hydrocarbon waste management 67–90 (2023)

Moses, K. K., Aliyu, A., Hamza, A. & Mohammed-Dabo, I. A. Recycling of waste lubricating oil: A review of the recycling technologies with a focus on catalytic cracking, techno-economic and life cycle assessments. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 11, 111273 (2023).

Grosu, Y. et al. Mechanical, thermal, and electrical energy storage in a single working body: Electrification and thermal effects upon pressure-induced water intrusion-extrusion in nanoporous solids. ACS Appl. Mater. Interface. 9, 7044–7049 (2017).

European Commission. Simultaneous transformation of ambient heat and undesired vibrations into electricity via nanotriboelectrification during non-wetting liquid intrusion-extrusion into-from nanopores | Electro-Intrusion | Project | Fact sheet | H2020 | CORDIS | European Com n.d. https://www.electro-intrusion.eu/en/about (accessed March 18, 2024).

Lowe, A. et al. Effect of flexibility and nanotriboelectrification on the dynamic reversibility of water intrusion into nanopores: Pressure-transmitting fluid with frequency-dependent dissipation capability. ACS Appl. Mater. Interface. 11, 40842–40849 (2019).

Amabili, M. et al. Pore morphology determines spontaneous liquid extrusion from nanopores. ACS Nano 13, 1728–1738 (2019).

Zajdel, P. et al. Turning molecular springs into nano-shock absorbers: The effect of macroscopic morphology and crystal size on the dynamic hysteresis of water intrusion-extrusion into-from hydrophobic nanopores. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 26699–26713 (2022).

Zhao, W., Li, L., Grosu, Y. & Ding, Y. Adaptive MPPT: Boosting efficiency in heterogeneous power scenarios. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 67, 103843 (2024).

Weng, M. et al. Hydrophobic and antimicrobial polyimide based composite phase change materials with thermal energy storage capacity, applied as multifunctional construction material. Eng. Sci. 19, 301–311 (2022).

Le Donne, A. et al. Intrusion and extrusion of liquids in highly confining media: Bridging fundamental research to applications. Adv. Phys. X 7, 2052353 (2022).

Giacomello, A., Casciola, C. M., Grosu, Y. & Meloni, S. Liquid intrusion in and extrusion from non-wettable nanopores for technological applications. Eur. Phys. J B 948(94), 1–24 (2021).

Zala, A. & Patel, H. Dendrimer enhanced fingerprint and explosive detection: A critical review. Eng. Sci. 20, 1–13 (2022).

Abdelrahman, M. et al. Energy regenerative shock absorber based on a slotted link conversion mechanism for application in the electrical bus to power the low wattages devices. Appl. Energy 347, 121409 (2023).

Ali, A. et al. A review of energy harvesting from regenerative shock absorber from 2000 to 2021: Advancements, emerging applications, and technical challenges. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 303(30), 5371–5406 (2022).

Kingmaneerat A, Ratniyomchai T, Saikong W, Techawatcharapaikul C, Kulworawanichpong T. Reducing hydrogen consumption by using regenerative braking energy for hydrogen fuel-cell electric bus vehicles. (2024) 33 1334-.

Amayuelas, E. et al. Fluorinated nanosized zeolitic-imidazolate frameworks as potential devices for mechanical energy storage. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 16, 46374–46383 (2024).

Amayuelas, E. et al. Effect of linker hybridization on the wetting of hydrophobic metal-organic frameworks. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 383, 113423 (2025).

Donne A Le, Littlefair JD, Amayuelas E, Tortora M, Sharma SK, Mor J, et al. Tuning flexibility in MOFs: How stiffening and substitution control molecular intrusion and separation. J. Mater Chem A :In press (2025).

Eroshenko, V. A., Piatiletov, I., Coiffard, L. & Stoudenets, V. A new paradigm of mechanical energy dissipation. Part 2: Experimental investigation and effectiveness of a novel car damper. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part D J. Automob. Eng. 221, 301–312 (2007).

Eroshenko, V. A. & Lazarev, Y. F. Rheology and dynamics of repulsive clathrates. J. Appl. Mech. Tech. Phys. 53, 98–112 (2012).

Eroshenko, V. A. A new paradigm of mechanical energy dissipation. Part 1: Theoretical aspects and practical solutions. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part D J. Automob. Eng. 221, 285–300. https://doi.org/10.1243/09544070D01505 (2007).

Eroshenko V. Heterogeneous structure for accumulating or dissipating energy, methods of using such a structure and associated devices. 08/849128, 2000.

Eroshenko V. Damper with high dissipating power. AU761074B2, 2003.

Eroshenko V. Virtually oil-free shock absorber having high dissipative capacity. US8925697B2, 2011.

Grosu, Y., Faik, A., Nedelec, J. M. & Grolier, J. P. Reversible wetting in nanopores for thermal expansivity control: From extreme dilatation to unprecedented negative thermal expansion. J. Phys. Chem. C 121, 11499–11507 (2017).

Chen, S., Øye, G. & Sjöblom, J. Rheological properties of aqueous silica particle suspensions. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 26, 495–501 (2005).

Funding

This work is primarily funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No. 101017858. This work is also part of the grant RYC2021-032445-I funded by MICIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by the European Union NextGeneration EU/PRTR.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S. Y. and W. Z. contributes equally, both wrote the main manuscript, perform the investigation, and prepared figures. Y. M. conducted the simulation work. V. S. and L. L. provided design resources and reviewed the manuscript. M. A. S. provided resources and reviewed the manuscript. Y. G. provided fundings and reviewed the manuscript. Y. D. provided funding, supervision, and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All co-authors certify that the submission is original unpublished work and is not under review elsewhere.

Consent for publication

All authors agree to the publication of this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, S., Zhao, W., Maksum, Y. et al. Modelling and validation of shock absorption with tunable performance through liquid intrusion–extrusion cycles. Sci Rep 15, 39927 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23782-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23782-6