Abstract

Umbonium vestiarium is a prevalent benthic species in many tropical regions and is highly sensitive to environmental changes. Investigating the effects of low temperatures on its behavior and physiology is critical for understanding the ecological and environmental consequences of cold-water discharges associated with the Hybrid Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion (H-OTEC) system. Although assessing the ecological impact of cooling emissions from H-OTEC system is important, research on this subject remains limited. This study examined live specimens of U. vestiarium collected from the coast of Port Dickson, Malaysia. The organisms were grouped and cultured at temperatures of 10 °C, 16 °C, 23 °C, and 28 °C, with 30 individuals in each group. Behavioral (feeding, clinging, spreading, hiding, and crawling) and physiological (Chl-a consumption rate, respiration rate, body temperature, and gut passage rate) observations were conducted on all specimens across these temperature conditions. The statistical analysis revealed that within the experimental temperature range, low temperatures had an inhibitory effect on the survival of U. vestiarium. At 10 °C, the snails exhibited early mortality and a low final survival rate. At 16 °C, the snails remained in a prolonged resting state, while at 23 °C, they displayed pronounced behaviors such as retraction, hiding, and clinging. The highest levels of behavioral and physiological activity were observed at 28 °C. Additionally, body temperature and respiration rate increased significantly with rising water temperatures, while gut passage time showed an inverse relationship. Except at 23 °C, chlorophyll-a (Chl-a) consumption rates also increased markedly with higher water temperatures. The results of this study demonstrated that temperature significantly influenced the survival, behavior, and physiological responses of U. vestiarium under controlled laboratory conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

To mitigate the environmental impact of fossil fuel power plants, Malaysia is actively pursuing clean and sustainable energy alternatives. Given its unique geographical advantages, Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion (OTEC) system have emerged as a highly promising energy source for the country1. Port Dickson, located in Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia, is renowned for its warm and calm waters, making it an ideal location for OTEC operations2. These favorable conditions allow for the construction of OTEC facilities in close proximity to the coast. Malaysia’s first Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion (OTEC) plant, a 1.0 MW Hybrid OTEC (H-OTEC) facility, was completed in 2023 at the International Institute of Aquaculture and Aquatic Sciences (I-AQUAS), Universiti Putra Malaysia. This Hybrid Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion (H-OTEC) power plant extracts 28.5 tons per hour of artificially chilled seawater to condense the working fluid, such as ammonia. Warm surface water, pumped into the vicinity of the plant, is used to evaporate the working fluid. To optimize energy efficiency, the used artificially chilled seawater (7.4 ~ 11.3 °C) is discharged near the sea surface. However, the large volumes of cold discharge may significantly disrupt the marine ecosystem, necessitating an assessment of these impacts3,4.

Currently, research on the impact of OTEC cold emissions on marine ecology predominantly focuses on phytoplankton and fish3,5. In contrast, studies examining the effects of temperature reductions caused by OTEC cold emissions on marine benthic organisms are limited, and the potential impacts remain unclear. Lamadrid-Rose and Boehlert (1988) found that cold discharge inhibited the growth and development of eggs and larvae of tropical benthic fish, potentially resulting in significant mortality6. Reid et al. (2022) demonstrated that fish acclimated to a narrow thermal range, such as 15–20 °C, can experience cold shock when suddenly exposed to temperatures 5–10 °C lower than their acclimation temperature. In many species, acute drops exceeding 6–10 °C within hours can elicit physiological stress responses—such as increased ventilation rate, loss of equilibrium, and reduced swimming performance—and may lead to mortality if the cold exposure is prolonged (e.g., 4 days)4. In contrast, Giraud et al. (2019) found that the low temperatures associated with cold-water discharge from OTEC system had a negligible effect on phytoplankton production3. However, low temperatures have been shown to impact metabolic rates7, growth rates8,9, and food consumption rates10 in benthic organisms. A year-long field investigation conducted near the Port Dickson H-OTEC Pilot Plant (July 2023–May 2024) revealed that cold-water discharge is continuous and exerts a significant, lasting influence on benthic community structure, diversity, and abundance. Among macrobenthic assemblages, Umbonium vestiarium contributed most strongly to the observed impacts11.

Umbonium spp. (Trochidae), commonly known as button snails, display distinct ecological and evolutionary characteristics as sedentary, deposit, and suspension feeders12. Notably, Umbonium vestiarium was the only known filter-feeding gastropod possessing both inhalant and exhalant siphons13. U. vestiarium constitutes a key component of the macrobenthos. For example, on the beaches of Penang Island, Malaysia, it represented approximately 99% of the abundance of macrofauna and was the main food source for predators such as naticid gastropods and starfish14, playing an important role in coastal ecosystems15. The narrow habitat requirements16 and broad distribution of U. vestiarium, whose optimal temperature range is between 24.8 °C and 29.3 °C17,18, make it highly susceptible to both natural and anthropogenic disturbances19. Therefore, U. vestiarium has been utilized as a key species in several ecological studies14,15,19. Current research on the behavior of U. vestiarium has primarily focused on the influence of environmental factors, with findings indicating that the species tends to aggregate and migrate toward the shore in sandy environments20. Additionally, studies have shown that its reproduction and shoreward migration are seasonally influenced, with spawning mainly from March to August and peak recruitment between March and May. Settlement began at the lowest shore levels in early spring, and juveniles reaching 5–6 mm by June migrated upshore to higher sand flats, forming dense adult populations in the upper shore zones21. However, there is a paucity of research addressing the effects of specific physical and chemical parameters on its behavior (Fig. 1).

Global distribution of Umbonium vestiarium17.

Although U. vestiarium is a prevalent benthic organism in tropical and subtropical regions14,21,22, there is limited information regarding the effects of temperature on its feeding behavior. This study investigates the impact of temperature variation on the physiology and behavior of U. vestiarium, a marine gastropod mollusk from Port Dickson, under controlled laboratory conditions, to elucidate how exposure to colder water—such as that potentially released by Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion (OTEC) system—may affect this species. We hypothesized that reduced temperatures would suppress physiology activity and alter behavioral patterns, and we expected to observe measurable declines in food consumption rates, respiration rate alongside increased refuge-seeking or reduced mobility at lower temperatures.

Materials and methods

Collection of Umbonium vestiarium (Linnaeus, 1758)23 sample and preparation of culture medium

Umbonium vestiarium used in the study were collected during low tide in August, 2024 from the vicinity of the H-OTEC pilot plant discharge port in the coastal waters of Port Dickson, Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia (2°27’57.4"N 101°50’54.6"E), an area exposed to cold-water discharge for one month before sampling. They were placed in sealed bags with seawater, filling approximately one-quarter of the bag’s volume, and then stored in an insulated box with ice packs. The snails were transported to the laboratory within 24 h. Considering that U. vestiarium is a filter-feeding benthic organism, its primary food source is microalgae. For this experiment, the snails were fed with Thalassiosira sp. (diatoms), sourced from the microalgae laboratory at I-AQUAS, as diatoms are the most abundant microalgae at the collection site24. Thalassiosira sp. was cultured using Conway medium25 prepared with Port Dickson seawater, which was filtered through a 0.22 μm membrane filter (Sigma-Aldrich), at a dilution ratio of 1:1000. All chemicals utilized in this study were of analytical grade and were procured from Sigma-Aldrich. The physicochemical properties of seawater from Port Dickson used in the experiment were measured and are presented in Table 1.

The sand used in the study was collected from the habitat of the snail, transported to the laboratory, and dried in an oven at 120 °C for 12 h to minimize experimental errors caused by algae and organic matter. After drying and cooling, the sand was passed through a 1 mm sieve to remove any benthic organisms collected with the sand26, thereby reducing potential interference with the experiment. Chlorophyll-a and pheophytin-a were not detected in the dried sand, and the total organic matter (TOM) was 1.28 ± 0.43%.

Experimental design and procedures

The seawater temperature along the Port Dickson coast remains relatively stable throughout the year, ranging from 27.1 °C to 29.4 °C27. The cold-water discharge temperature of the H-OTEC system varies between 7.4 °C and 11.3 °C. During the cold discharge process, a temperature monitoring module (Pt100, XunYan) was used to measure water temperature at different distances from the discharge port. The temperature distribution was recorded over time, and after approximately 100 s, the temperature influence range and temperature differences reached a steady state, maintaining long-term stability thereafter. The observed temperature range was between 8.6 °C and 28.0 °C (Fig. 2). This study investigated the behavioral and physiological responses of Umbonium vestiarium under experimental conditions of 10 °C, 16 °C, 23 °C, and 28 °C.

Acclimation

A total of 120 healthy and active U. vestiarium (Trochidae) samples (30 snails collected at 0.5 m, 2.0 m, 4.5 m, and 10.0 m from the discharge point, respectively), with a mean shell size of 6–8 mm, were selected, representing fully grown individuals based on the typical adult size range reported for this species in the study area13,21. The snails were washed with filtered seawater and then treated with a 0.1% KMnO₄ solution to prevent pathogen infection28. They were then divided into four groups according to their collection distance from the discharge point, with 30 individuals allocated to each group. Each group was placed in a separate aquarium containing 4 L of filtered seawater. All aquaria were initially set at 28 °C, and the aquaria with snails collected at 10.0 m maintained at this temperature. To provide U. vestiarium sufficient time for physiological and behavioral acclimation while avoiding acute thermal shock29,30, the water temperature in three aquaria was independently reduced by 6 °C every 6 hours until the target temperatures of 23 °C (4.5 m samples), 16 °C (2.0 m samples), and 10 °C (0.5 m samples) were reached. Additionally, the water was changed daily, and the snails were fed 40 ml of Thalassiosira sp. with a density of 3.0 × 106 cells·ml⁻¹31. Once the target temperature was reached, the snails were allowed to acclimate to the laboratory conditions, including food and temperature. Various behavioral and physiological indicators were monitored daily from the first day of temperature adaptation until no significant changes were observed after 3 days. Consequently, the experiment began on the fifth day to minimize potential experimental errors resulting from abrupt environmental fluctuations32,33. The lighting cycle was set to 12 h of light and 12 h of darkness. Following the acclimation period, the snails were starved for 2 days to ensure their guts were empty before beginning the experiment.

Physiological and behavioral observation experiment on U. vestiarium

For each of the four experimental temperatures, six feeding arenas were established: three experimental enclosures containing snails and three control enclosures without snails. Each experimental feeding arena housed 10 snails for the feeding experiments. Each feeding arena consisted of a 1-liter beaker with a 3 cm deep sand layer at the bottom, sufficient for the snails to bury themselves. After soaking the beakers with filtered seawater, 500 ml of filtered seawater was added to each beaker, along with 5 ml of Thalassiosira sp. (3.0 × 10⁶ cells·ml⁻¹). Snails in each experimental beaker were observed and recorded for 2 min every half hour, from 9:30 am to 9:30 pm daily. This observation protocol was consistently implemented over a 5-day period. In the experiments involving the 10 °C, 16 °C, 23 °C, and 28 °C groups, behavioral observations were conducted for a total of 4 h per arena (with snails), amounting to an overall observation time of 48 h. During nighttime observations (after 7:00 pm), the light was briefly activated to facilitate visibility. During the five-day continuous experiment, the used seawater was removed daily, and feces on the sand surface were scraped off. Filtered seawater and Thalassiosira sp. were then added to replace the seawater, ensuring consistent initial chlorophyll-a and dissolved oxygen concentrations in all beakers. The oxygen meter was calibrated for each temperature treatment. Following each seawater renewal and the measurement of initial indicators, the beaker’s mouth was securely sealed with plastic wrap exclusively during respirometry measurements to prevent atmospheric oxygen from diffusing into the water.

At the end of the experiment, the maximum shell diameter of the snails was measured to the nearest 0.05 mm using a digital caliper. Residual water was removed from snails with retracted feet by gently blotting them with soft absorbent paper towels, following the non-destructive weighing method described by Palmer (1982)34. The snails remained on the paper towels until their shells were visibly dry (approximately 20–40 min). They were then weighed on an analytical balance, with their wet weight recorded to the nearest 0.0001 g.

Recording of activity

Based on the total records from the observation period, various activity variables were calculated. The time spent feeding (TF, %) was determined as the proportion of time spent feeding relative to the total observation time, with values averaged for all snails in each beaker. Similarly, the time spent clinging (TL, %), spreading (TS, %), hiding (TB, %), and crawling (TC, %) were calculated in the same way.

To facilitate the identification of various activities, feeding behavior was indicated by the inhalant siphon extending from the shell opening13. Clinging behavior was defined as the snail attaching firmly to the surface of the beaker without significant movement. Spreading behavior involved the snail extending its foot or body to explore the surrounding environment. Hiding behavior was characterized by more than half of the snail’s body surface area being buried in the sand layer. Crawling behavior was identified as movement across the surface of the beaker or substrate. If a snail was retracted such that its cover was at or below the level of the shell opening, or if it remained in a resting state—without displacement or morphological changes (e.g., at the bottom with its foot extended)—for three consecutive observation periods (3 h), it was considered inactive. Being in a hidden state was also classified as inactive. Any other state of the snails was considered active. Observations were conducted for 2 min at 30-minute intervals on the first day of the experiment to record the first appearance of feces in each beaker. All behavioral processes of U. vestiarium were systematically recorded using a video camera (Canon 700D).

Analysis of Chl-a

There is a strong correlation between the Chl-a content of phytoplankton and its concentration for cells of the same size class35. To minimize interference from suspended sand particles, this study measured Chl-a concentration instead of directly counting algal cells. Seawater samples (200 ml) were collected from each beaker at 0 and 24 h, filtered through 0.22 μm membranes, and extracted with 90% acetone following the standard protocol of Bao and Leng (2005)36. After overnight extraction at 4 °C, the absorbance of the extracts was measured at 665 nm and 649 nm using a DR 2700 Portable Spectrophotometer (Hach Company). A calibration curve was established using Chl-a standards (1–50 µg·L⁻¹), and the Chl-a concentration (mg·L⁻¹) was calculated using the formula described by Bao and Leng (2005)36.

The equation for the algae Chl-a consumption rate (mg·L⁻¹·ind⁻¹·d⁻¹) was37:

Where Cexp,24 is the Chl-a content of the experimental group at 24 h, Cexp,0 is the Chl-a content of the experimental group at 0 h, Cctrl,24 is the Chl-a content of the control group at 24 h, and Cctrl,0 is the Chl-a content of the control group at 0 h. N refers to the number of snails per beaker.

Measurement of respiration rate and body temperature

The surface temperature (°C) of each U. vestiarium was measured hourly from a distance of 5 cm by G320 infrared thermometer (distance-to-spot ratio: 12:1). Dissolved oxygen content (mg·L⁻¹) in each beaker was measured at 0 and 24 h in every experiment using the YSI Model 52 Dissolved Oxygen Meter (Xylem Inc.). The equation for the respiration rate (mg·L⁻¹·ind⁻¹·d⁻¹) was:

where Cexp,24 is the dissolved oxygen content of the experimental group at 24 h, and Cexp,0 is the dissolved oxygen content of the experimental group at 0 h. N refers to the number of snails per beaker.

The Temperature Coefficient (Q10) is a measure used to express the sensitivity of biological or chemical processes – food consumption rate, oxygen consumption rate, and gut passage rate – to a 10 °C temperature change38. The formula for Q10 is:

Where R1 represents the rate of the process at temperature T1, and R2 represents the rate of the process at temperature T2. When calculating Q10 for gut passage times, note that the process rate can be expressed as the inverse of time (1/time).

Analytical methods

The physiological index, including body temperature, Chl-a consumption rate, respiration rate, and gut passage rate, was assessed for normality and homogeneity of variance using normality plots and Levene’s test. All physiological variables met the assumptions of normality and homogeneity. One-way ANOVA was then conducted to examine whether these indices differed significantly among temperature treatments. When significant differences were detected, Student–Newman–Keuls (SNK) multiple comparison tests were applied to identify pairwise differences between temperature groups.

As the behavioral indices of snails did not meet parametric assumptions, nonparametric tests (Kruskal-Wallis) were used to analyze significant differences in behavioral activities among the groups. When significant differences between median values were detected, Dunn’s Test was employed to assess differences between temperature groups.

The study evaluated the effects of temperature on physiological and behavioral indicators of benthic organisms across four temperature groups (10 °C, 16 °C, 23 °C, and 28 °C). The response variables analyzed included body temperature, Chl-a consumption rate, respiration rate, gut passage rate, feeding, clinging, spreading, hiding, and crawling rate. Organism size (e.g., shell length) was included as a covariate, and tank identity was incorporated as a random effect to account for non-independence of individuals within the same tank and to control for tank-specific variability in the statistical estimation. The general formula for the mixed-effects model was:

To reduce multicollinearity among predictors and enhance the interpretability, stability, and reliability of the model, the standardized temperature (temp-scaled) was utilized in this study39,40. It was calculated using the formula: temp-scaled = [temp − mean(temp)]/sd (temp); Similarly, the standardized size was employed, computed as: size-scaled = [size − mean(size)]/sd (size).

The fitdistrplus package was used to fit the data to multiple distributions (e.g., normal, Gamma). When ΔAIC (difference) > 5, the model with the lower AIC was strongly preferred41. The mixed-effects model biplot presents a grey shaded area representing the 95% confidence interval around the fitted line. The equation in the top left corner represents the model fit, while R² denotes the coefficient of determination, indicating the model’s explanatory power. The formula is conducted with the activity index as the dependent variable (Y) and standardized temperature (temp-scaled) as the independent variable (X).

Principal component analysis (PCA) was used to integrate the physiological and behavioral responses of U. vestiarium across temperature treatments. All variables were log₁₀(x + 1) transformed before PCA analysis.

Additionally, the Mann-Whitney U test was conducted to compare various behavioral activity indices of U. vestiarium between day and night. No significant differences were found in behavioral activities between day and night (U = 17 ~ 60, N 1 = N 2 = 15, P = 0.1 ~ 0.89). Consequently, the daytime and nighttime data for behavioral activity indices were combined for analysis.

All Figures and analyses were generated in R v4.4.2, and all statistical analyses were conducted with a significance threshold of P < 0.05.

Results

Survival of U. vestiarium in varied temperature conditions

A one-way ANOVA analysis revealed no significant differences in mean size or wet weight among the experimental groups (size: F11,108=0.54, p = 0.87; wet weight: F11,108=1.03, p = 0.43). The mean shell diameter ranged from 6.905 to 7.18 mm, while the mean wet weight ranged from 0.0916 to 0.1061 g.

In this study, U. vestiarium exhibited significant mortality at 10 °C, with half of the snails dying within 2 h and all snails succumbing within 5 h. In the other groups, at 16 °C and 28 °C, only 2 snails died in total throughout the experiment, resulting in high survival rates of 9 to 10 snails out of 10 in each temperature group.

Temperature effects on the behavioral activity of U. vestiarium

This study examined the proportion of time spent on various behaviors of Umbonium vestiarium under different temperature conditions: 10 °C, 16 °C, 23 °C, and 28 °C (Fig. 3). Significant differences were observed in the behavioral time proportions among the four temperature groups. Specifically, the Kruskal-Wallis test revealed significant variations in crawling (H = 10.85, P < 0.05), feeding (H = 38.02, P < 0.001), spreading (H = 51.19, P < 0.001), hiding (H = 43.66, P < 0.001), and clinging (H = 14.26, P < 0.001).

Crawling time constituted a large proportion of activity in the 28 °C and 23 °C groups, whereas it was notably lower in the 16 °C and 10 °C groups, with the 10 °C group exhibiting almost negligible crawling. Statistical analysis revealed a significant difference in crawling time between the 28 °C and 10 °C groups (p < 0.05), while no significant differences were found between the 28 °C and 23 °C groups or the 28 °C and 16 °C groups. Feeding time was similarly high across the 28 °C, 23 °C, and 16 °C groups, but significantly lower in the 10 °C group. The difference in feeding time between the 10 °C group and the other three groups (28 °C, 23 °C, 16 °C) was significant (p < 0.001).

Effect of Temperature on (a) Crawling, (b) Feeding, (c) Spreading, (d) Hiding, and (e) Clinging of Umbonium vestiarium under experimental conditions. In the boxplots, the box borders denote the interquartile range (IQR), with the horizontal line within the box indicating the median value. The upper and lower whiskers extend to 1.5 times the IQR beyond the upper and lower quartiles, respectively. Statistical significance is denoted by asterisks: * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001 (Kruskal-Wallis test, Dunn’s test).

The analysis of crawling and spreading activity revealed that both the linear (temp-scaled, p < 0.001) and quadratic (I(temp-scaled²), p < 0.001) terms were highly significant, while size was not a significant predictor (p > 0.05) (supplementary material Table 1, 3 S). Those activities exhibited a distinct peak at approximately 28 °C (Fig. 4a, c). For feeding rate, the linear (p < 0.01) and quadratic (p < 0.05) terms were significant, whereas size was not significant (supplementary material Table 2 S). Feeding activity increased sharply with temperature, reaching its maximum at 21 °C, followed by a decline beyond this point (Fig. 4b). In terms of hiding activity, the linear term was not significant (p > 0.05), but the quadratic term was highly significant (p < 0.001), with size again not significant (supplementary material Table 4 S). Hiding activity displayed a parabolic pattern, peaking at an optimal temperature of 19.1 °C. Finally, clinging activity showed significant effects for both the linear (p < 0.001) and quadratic (p < 0.01) terms, while size was not significant (supplementary material Table 5 S). The optimal temperature for clinging activity was determined to be 24.0 °C.

Effect of temperature on (a) crawling, (b) feeding, (c) spreading, (d) hiding, and (e) clinging of U. vestiarium under experimental conditions. The black dots represent the observed values of behavioral activity at different treatment temperatures. The blue line (regression curve) depicts the predicted relationship between standardized temperature and behavioral activity, modeled using a generalized linear mixed-effects model (GLMM).

Relationship of respiration rate, feeding rate, and gut passage time to temperature

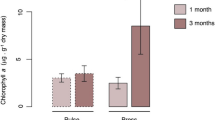

Figure 5 showed the physiological activity of Umbonium vestiarium at different temperatures (10 °C, 16 °C, 23 °C, and 28 °C). All one-way ANOVA tests yielded p < 0.001, with effect sizes (η²) of 0.98 for body temperature, 0.91 for gut passage time, 0.94 for chlorophyll-a consumption rate, and 0.95 for respiration rate.

Figure 5a illustrated a significant decline in body temperature as environmental temperature decreased. Figure 5(b) showed a significant increase in gut passage time from 28 °C to 16 °C, with the warmest environment (28 °C) producing the shortest gut passage time. In contrast, the cooler condition (16 °C) resulted in the longest gut passage time. Notably, at 10 °C, U. vestiarium exhibited no excretion.

Predicted relationships (log-transformed) between water temperature and (a) body temperature (°C), (b) gut passage times (h), (c) Chl-a consumption rate (mg·L⁻¹·ind⁻¹·d⁻¹), and (d) respiration rate (mg·L⁻¹·ind⁻¹·d⁻¹) for U. vestiarium across experimental temperatures, based on three replicates per temperature condition. Curves were fitted to individual data points; the model-estimated relationship is shown as a blue line with its 95% confidence band (grey). The black dots represent the mean values of physiological activity at different treatment temperatures. Different letters on each dot indicate significant differences as determined by the Student-Newman-Keuls (SNK) post hoc multiple comparison test.

Figure 5(c) revealed that the Chl-a consumption rate reaches its peak at 23 °C. As the temperature deviated from this optimum, the consumption rate declined sharply, with the lowest rates observed at the coldest temperature (10 °C). Figure 5(d) showed that respiration rate was highest at 28 °C and decreased significantly with declining temperature, reaching its lowest level at 10 °C.

The analysis of Chl-a consumption rate and gut passage rate indicated that both the linear term (temp-scaled, p < 0.001) and the quadratic term (I(temp-scaled²), p < 0.001) were highly significant, while size was not a significant factor (supplementary material Table 6, 7 S). The optimal temperature for Chl-a consumption rate was calculated to be 22.6 °C, whereas the optimal temperature for the gut passage rate was 28 °C (Fig. 5). In contrast, body temperature and respiration rate showed that only the linear term was highly significant, with size having no significant effects (supplementary material Table 8, 9 S; Fig. 5).

The results indicated that U. vestiarium exhibited a Q₁₀ value of 2.115 for the food consumption rate and 1.771 for the gut passage rate (Table 2). Compared to reported Q₁₀ values in other gastropod species, U. vestiarium displayed lower thermal sensitivity in food consumption than T. aureotincta (3.768) and T. funebralis (southern, 2.724), but higher than T. brunnea (1.542) and T. funebralis (northern, 1.000). For gut passage rate, U. vestiarium had a higher Q₁₀ than T. aureotincta (0.759), T. brunnea (1.042), T. funebralis (southern, 1.000), and T. funebralis (northern, 1.054). In terms of oxygen consumption, U. vestiarium (2.125) exhibited slightly higher temperature sensitivity than Trochus maculatus (1.9).

Relationship of respiration rate, feeding rate, and gut passage time to temperature

This study combined all physiological (Chl-a consumption rate, gut passage time, body temperature, respiration rate) and behavioral (crawling, feeding, spreading, hiding, clinging) responses of U. vestiarium into a multivariate analysis using principal component analysis (PCA). The first principal component (46.7%) primarily reflects variation in respiration rate, body temperature, feeding activity, and Chl-a consumption, while the second principal component (20.2%) is driven mainly by spreading, hiding, and clinging behaviors (Fig. 6).

The loadings indicate that PC1 was most strongly influenced by respiration rate (0.447), body temperature (0.435), feeding time (0.412), Chl-a consumption rate (0.406), and gut passage time (0.342). PC2 was mainly driven by spreading time (0.628), hiding time (0.554), Chl-a consumption rate (0.342), and clinging time (0.320).

Discussion

Given Malaysia’s commitment to achieving carbon neutrality by 205043 and its considerable potential for ocean thermal energy conversion (OTEC) development1, there is a notable gap in research concerning the effects of cold-water emissions from such projects on marine ecosystems.

The abundance of U. vestiarium in the marine environment is influenced by various environmental factors, including wave activity21,44, salinity45, and tides22. Among these, temperature stands out as the dominant factor affecting the abundance and community structure of benthic organisms, particularly under the influence of cold and thermal emissions from power plants46. Temperature also plays a key role in the growth and development of Umbonium ap.47. However, no standardized regulations currently exist for controlling the temperature of cold discharge from OTEC system3. Investigating the effects of temperature variations on the behavior and physiology of U. vestiarium is essential for assessing the ecological impacts of cold emissions from OTEC system and for informing the development of effective mitigation strategies.

Temperature effects on the behavioral activity of U. vestiarium

This study found that U. vestiarium exhibited higher feeding activity between 16 °C and 28 °C, with significantly reduced activity in colder conditions. Similar trends have been observed in other species, such as T. brunnea and Pomacea canaliculata, where feeding rates decline at lower temperatures10,42. In U. vestiarium, hiding and clinging behaviors increased as temperatures dropped below 28 °C, likely reflecting thermodynamic constraints on activity under thermal stress. These patterns align with observations from other studies. On Penang Island, U. vestiarium dominated fine-sand habitats with sediment temperatures of 28.86–31.4 °C, under less favorable thermal conditions, U. vestiarium often increased refuge use or relocated along the shore48, Likewise, Echinolittorina malaccana reduced oxygen consumption and heart rate via metabolic down-regulation during thermal stress22.

Temperature also affected movement-related behaviors. Between 16 °C and 23 °C, U. vestiarium displayed opposing trends in spreading behavior versus hiding and wall-attaching, likely due to metabolic shifts in response to temperature variations. Warmer conditions increased energy demands, promoting more active behaviors, while colder environments favored energy conservation strategies49,50. Additionally, crawling behavior was significantly higher between 23 °C and 28 °C, consistent with findings in other benthic species51. These results highlight the critical role of temperature in shaping behavioral responses and ecological interactions in U. vestiarium.

Relationship of respiration rate, feeding rate, and gut passage time to temperature

U. vestiarium depends on external environmental conditions to regulate its body heat, meaning its body temperature and metabolic activities are directly influenced by surrounding water temperatures52. Additionally, the study observed a positive relationship between water temperature and intestinal passage rate in U. vestiarium, where lower temperatures were associated with delayed excretion. This reduction in excretion may be attributed to the decreased metabolic rate of benthic organisms at lower temperatures, as noted by Robinson et al. (1983)53.

The thermal sensitivities of U. vestiarium’s food consumption rate, and respiration rate are all greater than 2 (Table 2), indicating positive thermal sensitivity—that is, these physiological processes accelerate with increasing temperature54. In biological systems, Q₁₀ values around 2 are typically indicative of enhanced metabolic and digestive activity in response to rising temperature55. However, the thermal sensitivity of U. vestiarium’s gut passage rate is lower than that of its food consumption rate and respiration rate. This difference arises because, in ectotherms like snails, metabolic rate and respiration rate are highly sensitive to temperature fluctuations47,56. Elevated temperatures substantially increase metabolic demands, resulting in greater respiration rate57. In contrast, the processes governing gut passage—such as the physical movement of food through the intestine (peristalsis) and enzymatic activity—are less influenced by temperature. Consequently, the efficiency of the digestive system, as reflected in intestinal transit rates, exhibits a lower thermal sensitivity46,58.

This study also found that U. vestiarium exhibited the highest efficiency in consuming chlorophyll-a (Chl-a) at approximately 23 °C, with feeding activity significantly reduced at both extremely high and low temperatures. This suggests that U. vestiarium is most efficient at consuming Chl-a at moderate temperatures, while extreme temperatures have an inhibitory effect on its metabolism59. Similar results were reported by Miyata & Nakatsubo (2024), who observed that feeding rates increased with temperature between 15 °C and 25 °C but declined at temperatures above 25 °C10. Furthermore, the study demonstrated that the oxygen consumption rate of U. vestiarium decreased significantly with falling temperatures, consistent with previous research showing that the respiration rate of gastropods generally increases with rising temperatures within an optimal range10,60.

The ecological and management consequences of temperature effects on the behavioral and physiological of U. vestiarium

This multivariate analysis demonstrates that temperature variation drives coordinated shifts in both behavioral and physiological traits. Warmer conditions (23–28 °C) enhance foraging activity, respiration rates, and mobility, reflecting elevated metabolic performance. In contrast, colder environments (< 16 °C) trigger stress-associated behaviors, such as increased clinging and hiding, coupled with reduced feeding and suppressed metabolic activity. Over time, these thermally induced changes in individual performance may translate into altered population dynamics and shifts in benthic community structure61.

As key consumers and decomposers in marine ecosystems14, U. vestiarium exhibits heightened sensitivity to temperature changes within the cold discharge gradients of H-OTEC operations. This pronounced thermal sensitivity makes U. vestiarium a valuable indicator species for assessing and monitoring the impacts of cold-water discharges11. Such discharges can trigger changes in the abundance and behavior of key species, such as primary consumers and predators, which may cascade through food webs, resulting in altered trophic interactions and potential ecosystem instability.

Based on the findings of this study, strategies can be implemented to maintain water temperatures near the outlet within the range of 23–28 °C, mitigating the ecological impacts of H-OTEC cold water discharge. Regular monitoring of water temperatures is crucial to ensure they remain within the optimal range for key species, such as U. vestiarium62. Additional strategies include designing the discharge system to enhance the dispersion of cold water, thereby minimizing localized cooling effects63,64.

Conclusion

This study provides the comprehensive assessment of the behavioral and physiological responses of U. vestiarium (Trochidae) under four temperature conditions (10 °C, 16 °C, 23 °C, and 28 °C), highlighting the species’ thermal sensitivity. Temperature strongly influenced behavior, metabolism, and feeding, with optimal activity occurring within the 23–28 °C range and the highest performance at 28 °C. In contrast, colder conditions (< 16 °C) induced stress-related behaviors (e.g., clinging, hiding) and suppressed metabolic activity, potentially leading to population declines.

Determining thermal performance curves—and the apparent behavioral and physiological optimal temperature—for U. vestiarium could inform monitoring thresholds for local cooling near the outfall. However, we did not quantify molecular stress biomarkers (e.g., heat-shock proteins HSP70/HSP90) due to technical constraints, and the experiments focused on a single species. Accordingly, long-term, multi-species benthic monitoring near the outfall remains necessary.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from figshare under the DOI: **https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28148696.v3**. The data are publicly available and can be accessed without restriction. The dataset is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

References

Thirugnana, S. T. et al. Estimation of ocean thermal energy conversion resources in the East of Malaysia. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 9 (1), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse9010022 (2020).

Jaafar, A. B., Husain, M. K. A. & Ariffin, A. Research and Development Activities of Ocean Thermal Energy-Driven Development in Malaysia. In Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion (OTEC)-Past, Present, and Progress. IntechOpen. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.90610 (2020).

Giraud, M. et al. Potential effects of deep seawater discharge by an ocean thermal energy conversion plant on the marine microorganisms in oligotrophic waters. Sci. Total Environ. 693, 133491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.07.297 (2019).

Reid, C. H. et al. An updated review of cold shock and cold stress in fish. J. Fish Biol. 100 (5), 1102–1137. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfb.15037 (2022).

Rau, G. H. & Baird, J. R. Negative-CO2-emissions ocean thermal energy conversion. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 95, 265–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2018.07.027 (2018).

Lamadrid-Rose, Y. & Boehlert, G. W. Effects of cold shock on egg, larval, and juvenile stages of tropical fishes: potential impacts of ocean thermal energy conversion. Mar. Environ. Res. 25 (3), 175–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/0141-1136(88)90002-5 (1988).

Staikou, A. et al. Activities of antioxidant enzymes and Hsp levels in response to elevated temperature in land snail species with varied latitudinal distribution. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B: Biochem. Mol. Biol. 269, 110908. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpb.2023.110908 (2024).

Rosen, R. et al. Evidence for cercarial development of Proterometra macrostoma (Digenea: Azygiidae) within the snail intermediate Host, elimia semicarinata, under simulated winter temperature conditions. Comp. Parasitol. 91 (1), 55–59. https://doi.org/10.1654/COPA-D-24-00001 (2024).

Morelli, S. et al. The influence of temperature on the larval development of Aelurostrongylus abstrusus in the land snail Cornu aspersum. Pathogens 10 (8), 960. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens10080960 (2021).

Miyata, Y. & Nakatsubo, T. Temperature dependence of feeding activity in the invasive freshwater snail Pomacea canaliculata: implications for its response to climate warming. Landscape Ecol. Eng. 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11355-024-00619-4 (2024).

Leng, Q., Mohamat-Yusuff, F., Mohamed, K. N., Zainordin, N. S. & Hassan, Z. Evaluation of macro and meiobenthic community structure and distribution in the hybrid ocean thermal energy conversion discharge area of Port Dickson. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 25233. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10723-6 (2025).

Noda, T., Nakao, S. & Goshima, S. Life history of the temperate subtidal gastropod umbonium costatum. Mar. Biol. 122, 73–78. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00349279 (1995).

Fretter, V. Umbonium vestiarium, a filter-feeding trochid. J. Zool. 177 (4), 541–552. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7998.1975.tb02258.x (1975).

Berry, A. J. Umbonium vestiarium (L.) (Gastropoda, Trochacea) as the food source for naticid gastropods and a starfish on a Malaysian sandy shore. J. Molluscan Stud. 50 (1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.mollus.a065838 (1984).

Obligar, P. I., Contreras, E. E. & Bunda, R. Abundance, Frequency, economic valuation and polymorphism of Umbonium vestiarium in Pilar Bay: Basis for environmental and economic policy making. 29 (2) (2021).

Ong, B. & Krishnan, S. Changes in the macrobenthos community of a sand flat after erosion. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 40 (1), 21–33 (1995).

Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF). Umbonium vestiarium (Linnaeus, 1758). https://www.gbif.org/species/4358247 (2024).

Kaschner, K. et al. AquaMaps: Predicted range maps for aquatic species (World wide web electronic publication, Version, 8, 2016). https://www.aquamaps.org/

Sivadas, S., Ingole, B. S. & Sen, A. Some ecological aspects and potential threats to an intertidal gastropod, Umbonium vestiarium. http://drs.nio.org/drs/handle/2264/4201 (2012).

Hüttel, M. Active aggregation and downshore migration in the trochid snail umbonium vestiarium (L.) on a tropical sand flat. Ophelia 26 (1), 221–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/0272-7714(95)90010-1 (1986).

Berry, A. J. Reproductive cycles, egg production and recruitment in the Indo-Pacific intertidal gastropod Umbonium vestiarium (L.). Estuarine Coastal. Shelf Sci. 24 (5), 711–723. https://doi.org/10.1016/0272-7714(87)90109-0 (1987).

Halim, S. S. A., Shuib, S., Talib, A. & Yahya, K. Species composition, richness, and distribution of molluscs from intertidal areas at Penang Island, Malaysia. Songklanakarin J. Sci. Technol. 41 (1), 165–173. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/333249828 (2019).

Linnaeus, C. Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis [The system of nature through the three kingdoms of nature, according to classes, orders, genera, species, with characters, differences, synonyms, places]. 1(10) [iii], Impensis Direct. Laurentii Salvii (1758).

Phang, S. M. et al. Checklist of microalgae collected from different habitats in Peninsular Malaysia for selection of algal biofuel feedstocks. Malaysian J. Sci. 34 (2), 141–167. https://doi.org/10.22452/mjs.vol34no2.2 (2015).

Lananan, F., Jusoh, A., Ali, N. A., Lam, S. S. & Endut, A. Effect of Conway medium and f/2 medium on the growth of six genera of South China sea marine microalgae. Bioresour. Technol. 141, 75–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2013.03.006 (2013).

Isha, I. B., Adib, M. R. M. & Daud, M. E. Composition of particle size at Regency Beach, Port Dickson. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 498(1), 012070. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/498/1/012070 (2020).

Weather Spark. Climate and Average Weather Year Round in Port Dickson - Average Monthly Rainfall in Port Dickson (Dickson-Malaysia-Year-Round, 2024). https://weatherspark.com/y/113802/Average-Weather-in-Port-

Dhara, K. & Guhathakurta, H. Toicity of Neem (Azadirachta indica a, juss) leaf extracts on fresh water snail, Bellamya bengalensis (Lamarck, 1882). BIOINFOLET-A quarterly. J. Life Sci. 18 (1a), 35–39 (2021).

Mora, C. & Maya, M. F. Effect of the rate of temperature increase of the dynamic method on the heat tolerance of fishes. J. Therm. Biol. 31 (4), 337–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtherbio.2006.01.005 (2006).

Harada, K., Ohashi, S., Fujii, A. & Tamaki, A. Embryonic and larval development of the trochid gastropod Umbonium moniliferum reared in the laboratory. Venus (Journal Malacological Soc. Japan). 63 (3–4), 135–143. https://doi.org/10.18941/venus.63.3-4_135 (2005).

Whyte, J. N. Biochemical composition and energy content of six species of phytoplankton used in mariculture of bivalves. Aquaculture 60 (3–4), 231–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/0044-8486(87)90290-0 (1987).

Obernier, J. A. & Baldwin, R. L. Establishing an appropriate period of acclimatization following transportation of laboratory animals. ILAR J. 47 (4), 364–369. https://doi.org/10.1093/ilar.47.4.364 (2006).

Maxwell, A. R., Castell, N. J., Brockhurst, J. K., Hutchinson, E. K. & Izzi, J. M. Determination of an acclimation period for swine in biomedical research. J. Am. Assoc. Lab. Anim. Sci. 63 (6), 651–654. https://doi.org/10.30802/AALAS-JAALAS-24-047 (2024).

Palmer, A. R. Growth in marine gastropods. A non-destructive technique for independently measuring shell and body weight. Malacologia 23 (1), 63–74 (1982).

Font-Muñoz, J. S., Jordi, A., Angles, S. & Basterretxea, G. Estimation of phytoplankton size structure in coastal waters using simultaneous laser diffraction and fluorescence measurements. J. Plankton Res. 37 (4), 740–751. https://doi.org/10.1093/plankt/fbv041 (2015).

Bao, W. K. & Leng, L. Determination methods for photosynthetic pigment content of bryophyte with special relation of extracting solvents. Chin. J. Appl. Environ. Biol. 11 (2), 235–237. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2010.1414 (2005).

Cronin, G. & Hay, M. E. Induction of seaweed chemical defenses by amphipod grazing. Ecology 77 (8), 2287–2301. https://doi.org/10.2307/2265731 (1996).

Minuti, J. J., Corra, C. A., Helmuth, B. S. & Russell, B. D. Increased thermal sensitivity of a tropical marine gastropod under combined CO2 and temperature stress. Front. Mar. Sci. 8, 643377. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2021.643377 (2021).

Lüdtke, O. & Robitzsch, A. On standardizing within-person effects: potential problems of global standardization. Front. Psychol. 10, 1505. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01505 (2019).

Schielzeth, H. Simple means to improve the interpretability of regression coefficients. Methods Ecol. Evol. 1 (2), 103–113. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2041-210X.2010.00012.x (2010).

Burnham, K. P. & Anderson, D. R. Multimodel inference: Understanding AIC and BIC in model selection. Sociol. Methods Res. 33 (2), 261–304. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124104268644 (2004).

Yee, E. H. & Murray, S. N. Effects of temperature on activity, food consumption rates, and gut passage times of seaweed-eating Tegula species (Trochidae) from California. Mar. Biol. 145, 895–903. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-004-1379-6 (2004).

The Edge Malaysia. 12MP: Malaysia committed to becoming carbon-neutral nation by 2050, says PM. The Edge Malaysia. https://theedgemalaysia.com/article/12mp-malaysia-committed-becoming-carbonneutral-nation-2050-says-pm (2021).

Berry, A. J. & bin Othman, Z. An annual cycle of recruitment, growth and production in a Malaysian population of the trochacean gastropod Umbonium vestiarium (L.). Estuarine Coastal. Shelf Sci. 17 (3), 357–363. https://doi.org/10.1016/0272-7714(83)90027-6 (1983).

Sivadas, S., Gregory, A. & Ingole, B. How vulnerable is Indian Coast to oil spills? Impact of MV ocean Seraya oil spill. Curr. Sci., 504–512. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24102611 (2008).

Leng, Q., Mohamat-Yusuff, F., Mohamed, K. N., Zainordin, N. S. & Hassan, M. Z. Impacts of thermal and cold discharge from power plants on marine benthos and its mitigation measures: a systematic review. Front. Mar. Sci. 11, 1465289. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2024.1465289 (2024).

Ohata, S. On the spawning and early development of the sand snail Umbonium (Suchium) giganteum. Bull. Chiba Prefectural Fisheries Res. Cent. 1, 45–47 (2002).

Marshall, D. J. & McQuaid, C. D. Warming reduces metabolic rate in marine snails: adaptation to fluctuating high temperatures challenges the metabolic theory of ecology. Proc. Royal Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 278 (1703), 281–288. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2010.1414 (2011).

Saeedi, H., Warren, D. & Brandt, A. The environmental drivers of benthic fauna diversity and community composition. Front. Mar. Sci. 9, 804019. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2022.804019 (2022).

Tsikopoulou, I., Nasi, F. & Bremner, J. The importance of Understanding benthic ecosystem functioning. Front. Mar. Sci. 11, 1470915. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2024.1470915 (2024).

Bae, M. J., Chon, T. S. & Park, Y. S. Modeling behavior control of golden Apple snails at different temperatures. Ecol. Model. 306, 86–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2014.10.020 (2015).

Bullock, T. H. Compensation for temperature in the metabolism and activity of poikilotherms. Biol. Rev. 30 (3), 311–342. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-185X.1955.tb01211.x (1955).

Robinson, W. R., Peters, R. H. & Zimmermann, J. The effects of body size and temperature on metabolic rate of organisms. Can. J. Zool. 61 (2), 281–288. https://doi.org/10.1139/z83-037 (1983).

Litmer, A. R. A current knowledge gap and documented patterns in body Temperature, food Consumption, daily Activity, and growth rate in lizards. Ichthyol. Herpetology. 112 (3), 489–501. https://doi.org/10.1643/h2023078 (2024).

Ito, E., Ikemoto, Y. & Yoshioka, T. Thermodynamic implications of high Q10 of ThermoTRP channels in living cells. Biophysics 11, 33–38. https://doi.org/10.2142/biophysics.11.33 (2015).

Zimmermann, S., Gärtner, U., Ferreira, G. S., Köhler, H. R. & Wharam, D. Thermal impact and the relevance of body size and activity on the oxygen consumption of a terrestrial Snail, Theba Pisana (Helicidae) at high ambient temperatures. Animals 14 (2), 261. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani14020261 (2024).

Hermaniuk, A., van de Pol, I. L. & Verberk, W. C. Are acute and acclimated thermal effects on metabolic rate modulated by cell size? A comparison between diploid and triploid zebrafish larvae. J. Exp. Biol. 224 (1), jeb227124. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.227124 (2021).

Van Damme, R., Bauwens, D. & Verheyen, R. F. The Thermal Dependence of Feeding behaviour, Food Consumption and gut-passage time in the Lizard Lacerta Vivipara Jacquin 507–517 (Functional Ecology, 1991).

Verberk, W. C. et al. Can respiratory physiology predict thermal niches? Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1365 (1), 73–88. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.12876 (2016).

Sidorov, A. V. Effect of acute temperature change on lung respiration of the mollusc Lymnaea stagnalis. J. Therm. Biol. 30 (2), 163–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtherbio.2004.10.002 (2005).

Hiddink, J. G., Burrows, M. T. & García Molinos, J. Temperature tracking by North sea benthic invertebrates in response to climate change. Glob. Change Biol. 21 (1), 117–129. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12726 (2015).

Çetin, Y. & Adem, A. C. I. R. Decontamination applications in primary circuit equipment of nuclear power plants. Int. J. Energy Stud. 7 (2), 195–216. https://doi.org/10.58559/ijes.1178889 (2022).

Comfort, C. M. & Vega, L. Environmental assessment for ocean thermal energy conversion in Hawaii: Available data and a protocol for baseline monitoring. In OCEANS’11 MTS/IEEE KONA, 1–8 (IEEE, 2011). https://doi.org/10.23919/OCEANS.2011.6107210.

Wang, X., Grishchenko, D. & Kudinov, P. Development of Effective Momentum Model for Steam Injection Through Multi-Hole Spargers: Unit Cell Model. In International Conference on Nuclear Engineering (Vol. 85277, p. V004T14A084). American Society of Mechanical Engineers. https://doi.org/10.1115/ICONE28-65751 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Mr. Mohd Fakhrulddin Ismail, Research Officer, Podeshin I-AQUAS Microalgae Laboratory, who contributed Thalassiosira sp. Furthermore, the authors would like to thank University Putra Malaysia (UPM) for their support through a scientific start-up scholarship (GP-IPS/2023/9768600) for the project. Special thanks are extended to the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST), the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), and the Ministry of Higher Education Malaysia (MoHE) for their generous support through the Science and Technology Research Partnership for Sustainable Development (SATREPS) Program. This initiative, titled “Development of Advanced Hybrid Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion (OTEC) Technology for a Low Carbon Society and Sustainable Energy System: First Experimental OTEC Plant of Malaysia,” has been a cornerstone in facilitating the progress of this research.

Funding

Ferdaus Mohamat Yusuff reports financial support was provided by Science and Technology Research Partnership for Sustainable Development. Ferdaus Mohamat Yusuff reports financial support was provided by Malaysia Ministry of Higher Education. Other authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ferdaus Mohamat Yusuff: Conceptualization, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Writing-Review and EditingQingxue Leng: Methodology, Writing - Original Draft, Writing- Reviewing and EditingKhairul Nizam Mohamed: Methodology, Writing-Reviewing and EditingNazatul Syadia Zainordin: Visualization, Investigation, ValidationMohd Zafri Hassan: Data curation, Writing-Review and EditingSathiabama T. Thirugnana: Data curation, Writing-ReviewShamsul Sarip: Visualization, Writing-Review.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Leng, Q., Yusuff, F.M., Mohamed, K.N. et al. Behavioral and physiological responses of Umbonium vestiarium to temperature variation from cold-water discharge of H-OTEC system. Sci Rep 15, 40159 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23909-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23909-9