Abstract

Point-resolved spectroscopy is commonly used for magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) due to widespread clinical availability, yet its accuracy can be compromised by chemical shift displacement error (CSDE) and sensitivity to magnetic field inhomogeneities, particularly near cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)-rich areas. Semi-localization by adiabatic selective refocusing (sLASER) mitigates these issues through superior voxel localization, reducing susceptibility to CSDE and B1 inhomogeneity. However, direct clinical comparisons between PRESS and sLASER, especially under matched acquisition conditions, remain scarce. This study aimed to directly compare PRESS and sLASER sequences regarding metabolite quantification accuracy and spectral quality in brain regions adjacent to CSF, under identical water suppression scheme. Thirty healthy adult volunteers (17 men; mean age, 40 ± 9.6 years) were recruited between January and July 2023. MRS data were acquired with PRESS and sLASER sequences at the left medial thalamus (near the third ventricle), using identical voxel placement and water suppression scheme of VAPOR. Metabolite concentrations were quantified using LCModel, and spectral quality metrics including residual water peak height, spectral signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), and spectral linewidth were also analyzed. As a result, compared to PRESS, sLASER yielded significantly higher concentration of NAA + NAAG, whereas Gly + mI were significantly lower (all, FDR adjusted q < 0.05). Spectral SNR was significantly higher (+ 24%, P < 0.001), but residual water peak height and spectral linewidth did not differ significantly (P > 0.05). Variability analysis indicated significantly higher coefficient of variation for Glu + Gln with sLASER (P < 0.05). In conclusion, in CSF-adjacent region, sLASER significantly increased spectral SNR but also exhibited greater variability in concentration for specific J-coupled metabolite. Therefore, although sLASER improved certain spectral quality aspects, caution is warranted due to higher variability in metabolite quantifications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In vivo magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) allows non-invasive quantification of brain metabolites by localizing and measuring proton (hydrogen 1 [1H]) signals.1,2 As a complementary technique to structural MR imaging (MRI), MRS has been proven effective in providing clinically relevant information about metabolite levels in both normal and diseased brains, leading to its increasingly frequent use in clinical practice1,3.

The point-resolved spectroscopy (PRESS)—a technique that provides single-shot 3D localization from the intersection of three slices using conventional radio-frequency (RF) pulses for excitation and refocusing—remains the widely utilized MRS method for single-voxel MRS, due to its status as the default sequence on most MRI platforms and longstanding clinical use4. However, PRESS has significant limitations, particularly at high magnetic fields exceeding 3 Tesla (T), primarily due to chemical shift displacement error (CSDE) and susceptibility to magnetic field inhomogeneities4,5,6,7. These factors result in mislocalization of metabolites, notably problematic in regions near cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) such as the ventricles, leading to residual water signals and compromised metabolite quantification accuracy8,9.

To address these limitations, semi-localization by adiabatic selective refocusing (sLASER) was developed, employing adiabatic refocusing pulses that significantly reduce localization errors compared to PRESS4,5, resulting in more accurate spectral acquisition unaffected by B1 inhomogeneity6,10,11,12,13. Despite sLASER’s clear technical advantages, it has not yet been universally adopted in clinical practice. Consequently, direct comparisons of PRESS versus sLASER under equivalent conditions are scarce. Notably, most prior comparisons did not examine how differences in localization error might impact metabolite quantification when both sequences use the same water suppression scheme. This comparison is particularly relevant for voxels placed near CSF-rich regions (e.g., adjacent to a ventricle), where PRESS’s localization error could lead to greater residual water signals and underestimation of metabolite levels.

In the present study, we aimed to directly compare sLASER and PRESS MRS in a brain region adjacent to CSF, using matched acquisition parameters including an identical water suppression module of a variable pulse power and optimized relaxation delay (VAPOR)5,6,14,15. This study design enabled us to isolate the effect of the localization sequence on spectral quality. The purpose of this study was to evaluate whether sLASER could indeed outperform PRESS in terms of metabolite quantification and spectral quality when B0/B1 inhomogeneity is significant and water suppression technique is held constant in normal adult brains.

Methods

Participants

This prospective study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (IRB No. B-2303–819-302). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrollment. Our study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Healthy volunteers without any underlying neurological disease were recruited through hospital advertisements between January and July 2023. Information regarding any history of neurological diseases or current conditions was obtained through self-reports and a review of previous electronic medical records and MRI assessments. The exclusion criteria at the time of enrollment were as follows: (a) those with prior or current neurological and/or psychiatric disease, (b) those who had any contraindication for MRI acquisition, (c) those under the age of 19 years; (d) those who were pregnant; and (e) those who did not consent to participate in this study.

As a result, a total of 30 participants (17 men and 13 women; mean age, 40 ± 9.6 years; age range 30–54 years) were included in this study, and MRS acquisition was performed between May and June 2025.

MRS acquisition

MRS data were acquired using a 3 T MRI scanner (Ingenia Elition, Philips Healthcare, The Netherlands) equipped with a 32-channel phased-array head coil for RF reception.

The PRESS sequence utilized amplitude-modulated refocusing pulses with the following parameters: repetition time (TR) = 2000 ms; echo time (TE) = 144 ms; voxel size = 20 × 20 × 20 mm3; spectral bandwidth = 2000 Hz; number of samples = 2048; and number of signal averages (NSA) = 128. The excitation pulse had a bandwidth of 2136.18 Hz and a duration of 7.55 ms, and the refocusing pulse had a bandwidth of 1250.00 Hz and a duration of 7.35 ms. Gradient spoiling was not applied, and echo acquisition was conducted in half mode. Water suppression was performed using a VAPOR scheme with a suppression window of 100 Hz. The PRESS sequence had a total scan duration of 4 min and 28 s (Fig. 1A).

The sLASER sequence employed adiabatic refocusing pulses with identical acquisition parameters to PRESS: TR = 2000 ms; TE = 144 ms; voxel size = 20 × 20 × 20 mm3; spectral bandwidth = 2000 Hz; number of samples = 2048; and NSA = 128. The excitation pulse had a bandwidth of 2136.18 Hz and a duration of 7.55 ms, and the adiabatic refocusing pulse had a bandwidth of 4063.16 Hz and a duration of 6.40 ms. Strong crusher gradients were not applied, and echo acquisition mode was also set to half. Water suppression in sLASER also utilized the VAPOR scheme with a suppression window of 100 Hz, consistent with PRESS. The total scan time for sLASER was the same as that of PRESS (4 min and 28 s) (Fig. 1B).

Both the PRESS and sLASER sequences were acquired with the “no spoiler gradient” option enabled. This option disables the dedicated crusher gradients that are normally applied between the refocusing pulses, whereas basic spoiler gradients following the 90° excitation pulse and within the VAPOR water suppression module remain present.

To select a volume-of-interest (VOI) of 8 mL in the left medial thalamus, 3D T1-weighted imaging was performed using the following parameters: TR = 6.4 ms; TE = 2.9 ms; slice thickness = 1.5 mm; flip angle = 9º; field-of-view = 240 × 240 mm2; acquisition matrix = 200 × 200. A single voxel was localized by a neuroradiologist (Y.J.B. with 11 years of experience) in the left medial thalamus, targeting a region immediately adjacent to the third ventricle (Fig. 2). This VOI was chosen to evaluate region near ventricle – CSF-rich space, where strong residual water signals and partial volume effects are expected to be a concern.

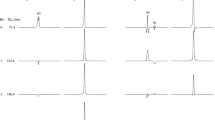

Representative figures of (a) the voxel-of-interest in the left thalamus, TE 144 ms, with the VAPOR water suppression prepulse module applied, (b) PRESS localized spectrum (in vivo), LCModel fitted spectrum (fitted), and fitted residual spectrum (residual; = in vivo—fitted), and (c) sLASER localized spectrum (in vivo), LCModel fitted spectrum (fitted), and fitted residual spectrum (residual; = in vivo—fitted). For the lactate signal (1.3 ppm), which is most directly affected by J-evolution at TE 144 ms, sLASER shows clearer fitting results compared to PRESS. This is attributed to the advantage of sLASER, which exhibits Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill (CPMG) characteristics, enhancing signal-to-noise ratio even at long TE.

MRS processing and quantification

MRS data obtained from PRESS and sLASER sequences were processed and analyzed for quantification using LCModel software (version 6.3-1R)16.Spectral data acquired with water suppression were first imported into jMRUI software (version 7.0)17, where manual frequency and phase correction were performed. Subsequently, an in-house python script was used to encode the corrected data into the Philips raw data format, ensuring compatibility for input into LCModel. Metabolite concentrations were quantified using water scaling.

Considering subtle variations in PRESS and sLASER pulse sequence implementations among different MR vendors, this study utilized MRScloud to construct a basis set specifically optimized for the Philips vendor. Basis spectra were generated via density-matrix simulations incorporating metabolite-specific chemical shifts and J-coupling constants. In particular, sLASER was simulated using GOIA-WURST refocusing pulses (bandwidth: 8 kHz, duration: 4.5 ms, B1: 15 µT)18. Because vendor RF-pulse details are proprietary, exact replication was not feasible. Therefore, GOIA-WURST refocusing pulses implemented in MRSCloud were used as a validated alternative, with minimal expected impact on short-TE quantification6.

The following metabolites were quantified19: Alanine (Ala), Ascorbate (Asc), Aspartate (Asp), Creatine (Cr), Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), Glycerophosphocholine (GPC), Glutathione (GSH), Glutamine (Gln), Glutamate (Glu), Glycine (Gly), Lactate (Lac), N-acetylaspartate (NAA), N-acetylaspartylglutamate (NAAG), Phosphocholine (PCh), Phosphocreatine (PCr), Phosphorylethanolamine (PE), Serine (Ser), Taurine (Tau), myo-Inositol (mI), and scyllo-Inositol (sI). Additionally, composite signals such as total creatine (Cr + PCr), total N-acetylaspartate (NAA + NAAG), combined glutamate and glutamine (Glu + Gln), combined glycine and myo-inositol (Gly + mI), and combined glycerophosphocholine and phosphocholine (GPC + PCh) were reported. All metabolite concentrations were normalized to total creatine (tCr, i.e., Cr + PCr).

Spectral quality evaluation was also performed. Residual water signals were assessed in absolute mode, a method that removes phase information, providing a magnitude-based measurement of residual water peak heights after water suppression. Spectral signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) was determined from the fitted NAA resonance, and spectral linewidth was expressed as the full-width at half maximum (FWHM, Hz) of the same peak. Specifically, SNR was defined as the baseline-corrected height of the NAA-CH₃ peak divided by twice the standard deviation of the noise measured in a metabolite-free region (8–10 ppm), in line with methodological consensus recommendations4.

Spectra failing to meet predefined quality criteria, specifically a spectral linewidth exceeding 0.1 ppm, spectral SNR below 3, or the presence of ghosting artifacts within the chemical shift range of 0.5–4.0 ppm, were excluded from analysis. Metabolite quantifications with Cramér-Rao Lower Bounds (CRLB) exceeding 50% were also excluded. As a result, 10 participants were excluded due to spectra failing to meet predefined quality criteria.

All quantification details, processing steps, and parameters used are comprehensively described in the MRSinMRS checklist provided in the Supplementary Materials.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were performed to compare metabolite concentrations and spectral quality metrics (residual water height, spectral SNR, and spectral linewidth) between the PRESS and sLASER sequences. Metabolites for which more than 50% of values in either sequence were zero or missing were considered unreliable and excluded from the subsequent paired analysis. For the remaining metabolites, zeros were treated as missing values and pair-wise deletion was applied so that each paired t-test included only subjects with non-zero data in both sequences. Additionally, coefficients of variation (CVs) were calculated as a ratio of standard deviation to the mean to assess variability for each metabolite and spectral quality metric. Variance testing was performed using Levene’s test to statistically compare variability between the two techniques. For multiple comparisons, P-values from raw paired t-test were adjusted using the Benjamini–Hochberg false-discovery-rate procedure (FDR; α = 0.05) to limit false-positive findings across multiple variables. P-values under 0.05 were considered statistically significant, and for multiple comparisons, q < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS; version 25.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) and R software (version 4.2.1).

Results

Metabolite concentration comparison between PRESS and sLASER

Representative spectra obtained from both sequences are shown in Fig. 1. After excluding metabolites with more than 50% missing or zero values in either sequence (Ala, Gly, Lac, PCh), 21 metabolites from 20 volunteers were eligible for paired analyses. Then, we included only those metabolites that consistently yielded data from 20 subjects for both the PRESS and sLASER sequences. Table 1 summarizes the results of paired comparisons of metabolite concentrations between PRESS and sLASER. After FDR correction, sLASER yielded significantly higher concentration than PRESS for NAA + NAAG, whereas Gly + mI was significantly lower in sLASER than PRESS (all, q > 0.05). All other metabolites showed no significant differences after adjustment (all, q > 0.05).

Spectral quality comparison between PRESS and sLASER

Compared with PRESS, sLASER produced a significantly higher spectral SNR (P < 0.001) and non-significant downward trends in residual water peak height and linewidth (Table 2 and Fig. 3a-c).

Box-and-whisker plots comparing spectral quality between PRESS and sLASER acquisitions. From left to right, panels display (a) residual water peak height, (b) spectral signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), and (c) spectral linewidth (full-width at half-maximum, ppm). Each box shows the interquartile range, whiskers extend to 1.5 × interquartile range, and the blue horizontal line marks the median. PRESS, point-resolved spectroscopy; sLASER, semi-localization by adiabatic selective refocusing; SNR, signal-to-noise ratio; ppm, parts per million.

Variance testing between PRESS and sLASER

Glu + Gln exhibited significantly higher variability with sLASER (q < 0.05) (Table 3). Variability for the remaining metabolites did not differ between sequences after FDR correction (all, q > 0.05).

For the three spectral quality metrics, no significant variance difference was detected (all, P > 0.05) (Table 4), indicating comparable variability across the sequences.

Discussion

The present comparative study demonstrated that, in voxels near water-rich brain region, the sLASER sequence showed significantly higher concentration for NAA + NAAG and lower concentration of Gly + mI relative to PRESS. The sLASER sequence exhibited significantly higher spectral SNR, but no significant difference in residual water height and spectral linewidth. Lastly, the variability across subjects in concentration of Glu + Gln was significantly greater under sLASER. In summary, sLASER outperformed PRESS in localization and spectral quality, but introduced sequence-dependent differences in metabolite estimates and their variances.

Our findings can support the hypothesis that the sLASER sequence would impact metabolite quantification and improve MRS data quality compared to PRESS, even with identical water suppression method. We hypothesized that the adiabatic pulses and superior localization of sLASER could lead to better spectra with improved water suppression, thereby enabling more enhanced and reliable metabolite quantification, particularly in CSF-adjacent brain region. Indeed, the spectral SNR excluding the residual water signal was higher in sLASER at long TE, which was consistent with previous study20. For instance, Deelchand et al.21 demonstrated that an advanced sLASER protocol at 3 T achieved significantly higher SNR and narrower linewidths than a standard PRESS acquisition. This is presumed to be due to the higher SNR of the NAA signal at 2.01 ppm in sLASER compared to PRESS, attributed to the Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill (CPMG)-like characteristics22. Our study replicated this advantage in brain regions susceptible to residual water signal due to proximity to CSF-filled ventricle. In addition, even though the statistical significance was not validated, the maximum heights of the residual water signal and the variance were also lower with sLASER. This can suggest that the efficiency of VAPOR water suppression, driven by superior localization performance, is more consistently higher in sLASER compared to PRESS. This improvement in data quality can support that sLASER can be a technically superior methodology for brain MRS, as was predicted.

Furthermore, we posited that the sequence differences would not only improve quality but also alter the quantified metabolite concentrations. The sLASER is known to be less affected by the signal loss from chemical shift misregistration and J-modulation, enabling more metabolite spins to contribute to the observed signal6,14. The fact that sLASER yielded higher detected concentration of NAA + NAAG is thus an expected outcome of its higher signal recovery. On the other hand, the concentration of Gly + mI was significantly lower with sLASER. The sLASER sequence employs adiabatic pulse trains with characteristics similar to the CPMG scheme22, which reduces T2* effects allowing signal decay to be primarily dependent on intrinsic T2 relaxation. As a result, uncoupled spins exhibit a relatively higher SNR at longer TE compared to J-coupled spins. Since T2 correction was not applied in our study, metabolite like mI, which has strong J-coupling at 3 T23, may experience more pronounced signal loss compared to uncoupled metabolites such as Cr or PCr. Given that the VOI was positioned adjacent to CSF-rich regions, we speculate that susceptibility-related issues may have contributed significantly to our current findings. Furthermore, although our basis set simulations already incorporate J-modulation, the observed lower Gly + mI/tCr ratio with sLASER is more likely attributable to sequence-dependent factors, including the CPMG-like properties of adiabatic pulses, incomplete suppression of unwanted coherence pathways in the absence of spoiler gradients, and the lack of T2 correction for J-coupled metabolites. Therefore, further detailed simulation and validation are warranted. Taken together, these factors suggest that, paradoxically, sLASER may demand more meticulous sequence optimization than PRESS for reliable metabolite quantification.

Notably, the variability for the concentration of Glu + Gln sum was significantly greater with sLASER. In our study, to minimize the metabolite diffusion effect, data acquisition was performed without applying spoiler or crusher gradients. However, the sLASER sequence inherently employs a greater number of RF pulses for localization compared to PRESS, which increases the number of possible coherence pathways. This complexity may reduce the quantification stability, particularly for metabolites with strong J-coupling, such as mI and Glu24. In the absence of gradient crushers, the suppression of unwanted coherence pathways may be suboptimal, further contributing to signal variability. These findings suggest that sLASER requires more meticulous optimization of the phase cycling scheme, types of RF pulses, and gradient configurations to ensure consistent quantification of J-coupled metabolites.

One important limitation of our study is that no dedicated crusher gradients were applied between the refocusing pulses. This may have resulted in incomplete suppression of unwanted coherence pathways, contributing to increased signal variability, particularly for J-coupled metabolites. Although basic spoilers were still present in the VAPOR water suppression module and immediately after the excitation pulse, the absence of crushers in the localization blocks likely limited coherence pathway suppression in both PRESS and sLASER. This factor may partly explain the greater variability observed under the sLASER condition. Future studies should consider optimizing spoiler gradients and phase cycling schemes to minimize these effects. Another limitation is that the exact vendor RF waveforms could not be replicated in the basis-set simulations due to proprietary constraints. However, the use of validated adiabatic pulses within the correct sLASER timing framework is unlikely to have materially affected metabolite quantification under the present 3 T short-TE conditions6. Moreover, our single-site, single-scanner design with consistent LCModel analysis parameters minimizes potential confounders and supports the robustness of the comparative results between PRESS and sLASER.

The sLASER sequence’s adiabatic refocusing pulses were carefully designed to exceed the adiabatic threshold. Nevertheless, practical implementations may approach this limit due to constraints on pulse duration and TE. Additional pulses in sLASER can introduce potential coherence pathway artifacts and challenges in complete phase cycling, potentially affecting the reliability of J-coupled metabolite quantification.

The significance of our findings can be multifaceted. First, the improvement in spectral quality in vivo MRS using sLASER allows clinicians and researchers to quantify metabolite peaks more confidently, especially in challenging brain regions with high water content or pronounced B₀ inhomogeneity, such as areas adjacent to ventricles or edema-rich tissues, thus extending MRS applicability to clinically significant yet technically difficult regions. Second, our findings demonstrate systematic differences in measured metabolite concentrations between sLASER and PRESS. The consistently higher absolute concentrations measured by sLASER are due to minimal CSDE and improved signal localization. Since the VOI in this study is located close to the CSF, we expect that the metabolite levels are generally underestimated by PRESS. This highlights the importance of cautious interpretation when comparing data across different MRS sequences. Furthermore, this highlights a critical need to reconsider normative values and diagnostic thresholds, as metabolite baselines defined using PRESS may systematically differ from those measured with sLASER. Third, our findings clarify how sLASER affects the measurement of J-coupled metabolites. Although sLASER improves overall metabolite signals, partial J-modulation can introduce variability in strongly coupled metabolites like mI. Our results specifically show increased variability and reduced Gly + mI/tCr ratios, suggesting incomplete refocusing of J-couplings and sequence-dependent signal attenuation. This empirical evidence aligns with recent methodological advancements aimed at fully refocusing J-coupling7, reinforcing the practical importance of accounting for J-coupling dynamics even at clinical field strengths.

Our study has several limitations. First, data collection was limited to healthy adults, which limits analysis of pathological metabolite levels. However, to compare the performance of different sequences, the use of data from healthy adults is considered ideal because they provide a standardized baseline without introducing variability related to pathological conditions. Second, our study used a fixed long TE (144 ms) for both sequences. While this kept TE constant, it might not represent optimal conditions for all metabolites. Yet, we aimed to use long TE solely to reduce the confounding effects caused by the macromolecule baseline contributions, which are prominent in short TE MRS data. According to de Graaf et al.25, major macromolecules typically have very short T2 relaxation times ranging from approximately 30 to 50 ms; thus, utilizing a TE of 144 ms can maximize the T2 decay of these macromolecules, effectively suppressing their signal and minimizing their influence on the measured metabolite signals. Third, the VOIs selected for spectral quantification were defined by a single reader, which may have introduced a potential bias. However, the VOI placements were performed repeatedly by a highly skilled neuroradiologist with 11 years of experience to ensure consistency, reproducibility, and accuracy. Moreover, the anatomical structures selected for measurement were not difficult to identify, which minimized any concerns regarding variability in their placements. Fourth, as previously explained, the absence of dedicated crusher gradients in both PRESS and sLASER may have contributed to the increased variability observed for J-coupled metabolites. Lastly, our investigation focused on a specific CSF-adjacent brain region. This selection, while relevant for examining water suppression performance, our findings may not directly generalize to other voxel locations. However, we strategically selected the area susceptible to water contamination due to proximity to CSF spaces for a robust comparison of the water suppression efficacy and spectral accuracy of the sLASER and PRESS techniques. We believe the present findings will provide a basis for future studies investigating the performance of sLASER in various brain regions, and they may have significant clinical implications for patients with specific neurological conditions.

In conclusion, our results highlight both technical advantages and practical challenges of sLASER compared to PRESS. sLASER provided superior spectral SNR, despite employing the same water suppression scheme, primarily due to improved localization in CSF-adjacent brain regions. However, the sequence yielded different metabolite concentrations and introduced greater variability, particularly in metabolites with strong J-coupling. Therefore, a balanced view that considers both improved localization and increased complexity is essential, necessitating cautious interpretation and careful methodological optimization for clinical application.

Data availability

To conform with the institutional policy, the datasets generated and/or analyzed in this study have not been made publicly available; however, they can be acquired from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Oz, G. et al. Clinical proton MR spectroscopy in central nervous system disorders. Radiology 270, 658–679 (2014).

Tkác, I., Oz, G., Adriany, G., Uğurbil, K. & Gruetter, R. In vivo 1H NMR spectroscopy of the human brain at high magnetic fields: Metabolite quantification at 4T vs. 7T. Magn. Reson. Med. 62, 868–879 (2009).

Dacko, M. & Lange, T. Improved detection of lactate and beta-hydroxybutyrate using MEGA-sLASER at 3 T. NMR Biomed. 32, e4100 (2019).

Wilson, M. et al. Methodological consensus on clinical proton MRS of the brain: Review and recommendations. Magn. Reson. Med. 82, 527–550 (2019).

Öz, G. et al. Advanced single voxel 1 H magnetic resonance spectroscopy techniques in humans: Experts’ consensus recommendations. NMR Biomed. 34, e4236 (2020).

Deelchand, D. K. et al. Across-vendor standardization of semi-LASER for single-voxel MRS at 3T. NMR Biomed 34, e4218 (2021).

Najac, C., Boer, V. O., Kan, H. E., Webb, A. G. & Ronen, I. Improved detection limits of J-coupled neurometabolites in the human brain at 7 T with a J-refocused sLASER sequence. NMR Biomed. 35, e4801 (2022).

Guerrini, L. et al. Impact of cerebrospinal fluid contamination on brain metabolites evaluation with 1H-MR spectroscopy: a single voxel study of the cerebellar vermis in patients with degenerative ataxias. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 30, 11–17 (2009).

Song, Y. et al. Impact of gradient scheme and shimming on out-of-voxel echo artifacts in edited MRS. NMR Biomed. 36, e4839 (2022).

Sourdon, J. et al. Comparison of single-voxel 1H-cardiovascular magnetic resonance spectroscopy techniques for in vivo measurement of myocardial creatine and triglycerides at 3T. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 23, 53 (2021).

Warnking, J. M. & Pike, G. B. Bandwidth-modulated adiabatic RF pulses for uniform selective saturation and inversion. Magn. Reson. Med. 52, 1190–1199 (2004).

Gong, T. et al. Neurometabolic timecourse of healthy aging. Neuroimage 264, 119740 (2022).

Sacolick, L. I., Rothman, D. L. & de Graaf, R. A. Adiabatic refocusing pulses for volume selection in magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging. Magn. Reson. Med. 57, 548–553 (2007).

Scheenen, T. W. J., Klomp, D. W. J., Wijnen, J. P. & Heerschap, A. Short echo time 1H-MRSI of the human brain at 3T with minimal chemical shift displacement errors using adiabatic refocusing pulses. Magn. Reson. Med. 59, 1–6 (2008).

Oz, G. & Tkáč, I. Short-echo, single-shot, full-intensity proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy for neurochemical profiling at 4 T: Validation in the cerebellum and brainstem. Magn. Reson. Med. 65, 901–910 (2011).

Provencher, S. W. Automatic quantitation of localized in vivo 1H spectra with LCModel. NMR Biomed. 14, 260–264 (2001).

Stefan, D. et al. Quantitation of magnetic resonance spectroscopy signals: The jMRUI software package. Meas. Sci. Technol. 20, 104035 (2009).

Hui, S. C. N. et al. MRSCloud: A cloud-based MRS tool for basis set simulation. Magn. Reson. Med. 88, 1994–2004 (2022).

Považan, M. et al. Comparison of multivendor single-voxel MR spectroscopy data acquired in healthy brain at 26 sites. Radiology 295, 171–180 (2020).

Hui, S. C. N. et al. sLASER and PRESS perform similarly at revealing metabolite-age correlations at 3 T. Magn. Reson. Med. 91, 431–442 (2024).

Deelchand, D. K., Kantarci, K. & Öz, G. Improved localization, spectral quality, and repeatability with advanced MRS methodology in the clinical setting. Magn. Reson. Med. 79, 1241–1250 (2018).

Michaeli, S. et al. Proton T2 relaxation study of water, N-acetylaspartate, and creatine in human brain using Hahn and Carr-Purcell spin echoes at 4T and 7T. Magn. Reson. Med. 47, 629–633 (2002).

Kim, H., Wild, J. M. & Allen, P. S. Strategy for the spectral filtering of myo-inositol and other strongly coupled spins. Magn. Reson. Med. 51, 263–272 (2004).

Bodenhausen, G. Reflections of pathways: A short perspective on ‘Selection of coherence transfer pathways in NMR pulse experiments’. J. Magn. Reson. 213, 295–297 (2011).

de Graaf, R. A. et al. High magnetic field water and metabolite proton T1 and T2 relaxation in rat brain in vivo. Magn. Reson. Med. 56, 386–394 (2006).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.co.kr) for English language editing. We also wish to thank the Medical Research Collaborating Center at Seoul National University Bundang Hospital for consultations regarding the statistical analyses.

Funding

Yun Jung Bae has received research funding from the Institute of Information & Communications Technology Planning & Evaluation (IITP) granted by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. RS-2024–00459726, Development of a Quantum Deep Learning System for Radiological Diagnosis Based on Non-Invasive Brain Metabolite Biomarker).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.J.B. and J.H.K. contributed to the overall supervision of the project. Y.J.B. was responsible for funding acquisition. S.K.K., Y.J.B., and Y.A.O. contributed to the conceptualization of the study, data curation, formal analysis, validation, and visualization of the work. S.J.C., S.H.B., L.S., B.S.C., and J.H.K. contributed to the formal analysis, data validation, and visualization of the work. S.K.K. and Y.J.B. wrote the original draft. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, S.K., Oh, Y.A., Bae, Y.J. et al. Comparative analysis of sLASER and PRESS techniques for magnetic resonance spectroscopy of the normal human brain. Sci Rep 15, 40104 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23932-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23932-w