Abstract

Hybrid machine learning (ML) models exhibit enhanced accuracy relative to both ensemble and individual models. In this study, advanced hybrid ML approaches were employed to create a reliable model for estimating surface chloride concentration (CC) in marine concrete, eliminating the necessity for labour-intensive and expensive physical experiments. The study combined artificial neural networks (ANN) and support vector regression (SVR) with metaheuristic optimization algorithms, specifically grey wolf optimization (GWO) and gorilla troops optimization (GTO), resulting in the development of four innovative hybrid ML models. Additionally, the integration of partial dependence plots and SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) values offered profound insights into the critical variables influencing surface chloride concentration, advancing both the interpretability and precision of the models. These data sets were sourced from a wide range of literature. All the models exhibited strong performance, with SVR-GWO proving to be the optimal selection. Notably, SVR-GWO demonstrated the highest coefficient of determination (R2) of 0.96, highlighting its exceptional forecasting accuracy relative to SVR-GTO (0.95), ANN-GWO (0.92), and ANN-GTO (0.90). Among the features examined, fine aggregate emerges as the most influential, followed by exposure type, exposure time, and chloride content. Additionally, a user interface has been designed to allow users to enter key inputs and seamlessly obtain CC predictions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Concrete is extensively utilized for construction in coastal areas, as demonstrated by the numerous structures situated on or near the coast. In recent decades, there has been a significant rise in the development and utilization of coastal regions, leading to enhanced economic activity and increased employment opportunities. This development has consequently resulted in a growing human population in these areas1. In 2017, around 40% of the global population resided within 100 km of a coastline, as per the United Nations2. As the population continues to grow and people increasingly migrate to coastal regions, this pattern is anticipated to escalate, leading to higher requirements for residential and commercial infrastructure along coastlines. Concrete remains a popular choice for coastal construction due to its widespread availability, durability, cost-effectiveness, and versatility in accommodating diverse architectural designs3.

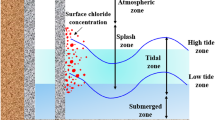

Steel-reinforced concrete structures in marine conditions often deteriorate because of the infiltration of diverse chemical compounds such as carbon dioxide, water, sulfates, and chlorides3. Among these, chloride ions are widely recognized as the primary contributors of steel deterioration in concrete structures situated in coastal areas4,5. This steel corrosion can lead to numerous early structural failures, resulting in significant economic repercussions. The protective coating of reinforcing steel in concrete is usually effective in preventing corrosion due to its stability in the alkaline conditions of concrete. Yet, in coastal regions, chloride ions transported via atmospheric marine aerosols often settle on the exposed surfaces of concrete that are not fully saturated, leading to potential corrosion issues. As chloride ions infiltrate concrete and gather around the steel within it, they can disrupt the protective film, initiating active corrosion that may result in concrete cracking and spalling6. The intricate processes involved in transport often lead to a peak occurrence marked by the highest concentration of chloride at a certain depth within the concrete, increasing the likelihood of corrosion for steel reinforcement bars7. In a 1991 report, the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) noted that around 39 percent of roadway infrastructure exhibited problems related to corrosion in their reinforcing elements. This finding highlighted approximately 134,000 structures that were identified as deteriorated and in need of immediate restoration8. The overall direct expense of corrosion is approximated at $276 billion annually, accounting for 3.1% of the U.S. GDP in 1998. in 1998. This calculation involved assessing 26 industrial sectors where corrosion is prevalent and extrapolating the findings to derive a nationwide estimate9. Different codes, standards, and guidelines for designing durable marine concrete categorize exposure conditions into splash, atmospheric, submerged and tidal zones. Fick’s second law models chloride infiltration in concrete, aiding quantitative evaluation and durability analysis10. The diffusion equation incorporates the surface-exposed chloride level, which signifies the impact levels of chloride exposure on reinforced concrete structures within different environmental classifications11. The surface chloride concentration (CC) is crucial for assessing and designing the durability of marine concrete. It serves as a pivotal parameter in defining the limits for chloride ion transport modelling in marine concrete12.

Various ML methods have been employed across different concrete applications. Advanced neural network models have achieved high predictive accuracy with an R2 value of 0.957 for structural applications13. For estimating the chloride ingress resistance of concrete, support vector machine (SVM), k-nearest neighbors (KNN), random forest (RF), XGBoost, LightGBM, decision tree (DT), and logistic regression, along with other ML models, were utilized. The results reveal that the SVM and XGBoost algorithms outperform other regression prediction algorithms, achieving high R2 of 0.91 and 0.94, respectively. In classification, XGBoost, LightGBM, and RF achieved accuracy scores of 0.97, 0.96, and 0.93, respectively14. Five prominent ML models have been applied to predict concrete strength, with gradient boosting consistently performing best15. KNN, Naive Bayes, SVM, DT, and RF were utilized to estimate the chloride ingress resistance in concrete determined by its constituent materials. In the first scenario, all mix component features are considered, while the second case uses merely a portion. The SVM outperformed other algorithms, achieving 89% accuracy in the first scenario and 88% in the second1. A stacking approach using meta-learners has achieved an R2 score of 0.88, outperforming individual models for estimating flexural strength of concrete16. Several techniques for generating rules were utilized and evaluated to forecast the chloride resistance of concrete that has been enhanced with high calcium fly ash (FA). The rules created by the J48 algorithm from the Weka workbench efficiently categorized high-calcium fly ash-modified concrete and plain concrete into groups of excellent, acceptable, or inadequate chloride resistance based on defined criteria17. A ML modeling framework was employed to estimate the chloride ingress resistance of recycled aggregate concrete (RAC). This framework incorporated various machine learning approaches, encompassing four separate techniques (Gaussian process regression, artificial neural network, DT, and SVM) and two ensemble techniques (gradient boosting and RF). All the ML models in the framework demonstrate strong efficacy in estimating the chloride ingress resistance of RAC (R2 > 0.90)18. Hybrid deep learning model have achieved an average R2 value of 0.96, with finite element integration enhancing cost-efficiency over traditional testing19. Sparrow search algorithm optimized XGBoost demonstrated an R2 of 0.91 for high performance concrete autogenous shrinkage prediction20, while aquila optimizer optimized XGBoost achieved an R2 value of 0.943 in testing for geopolymer concrete21. For high-strength concrete crushing strength estimation, leopard seal optimized XGBoost outperformed other hybrid models22. XGBoost was employed to forecast the chloride migration coefficient (Dnssm) of concrete23. To assess the impact of FA quantity on chloride ion resistance, three distinct ML approaches (DT, RF, gradient boosting regression) are utilized to estimate the overall chloride concentration in concrete at different fly ash admixture levels24. Surface chloride concentrations were forecasted using DT, artificial neural networks (ANN), and gene expression programming (GEP), followed by the identification of the most precise algorithm among them25. Analysing the dispersion patterns of chloride ion concentrations in concrete reinforced with basalt and polypropylene fibres (BPFRC) is crucial for assessing the longevity of concrete constructions subjected to marine conditions. Multiple factors influencing BPFRC were examined, leading to the creation of four models (ANN, particle swarm optimization (PSO)-ANN, SVR, and PSO-SVR models) for BPFRC26. Linear regression, RF regression, DT regression, SVR, XGBoost, gradient boosting, and multi-layer perceptron regression were utilized to predict surface chloride concentration27. Hybrid ML approaches were used to develop forecasting models for coral aggregate concrete subjected to three environmental conditions (tidal region, salt spray area, and underwater zone) to forecast chloride ion concentration28. An LM-based information creation model was proposed to enhance the efficacy of determining CC in reinforced concrete structures29.

Hybrid ML models exhibit enhanced accuracy relative to both ensemble and individual models. In this study, advanced hybrid ML approaches were utilized to create a reliable model for predicting CC in marine concrete, eliminating the necessity for labour-intensive and expensive physical experiments. The study combined SVR and ANN with metaheuristic optimization algorithms, specifically gorilla troops optimization and grey wolf optimization, resulting in the development of four innovative hybrid ML models. Additionally, the integration of partial dependence plots and SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) values offered profound insights into the critical variables influencing surface chloride concentration, advancing both the interpretability and precision of the models. By focusing on interpretability, this study aims to improve the reliability and applicability of ML models in real-world marine concrete scenarios, ultimately contributing to the creation of more durable and effective concrete structures. Furthermore, the study aims to design a user interface that enables users to input key parameters and obtain CC predictions without the need for experiments, enhancing practical applications.

Methodological framework

Database characteristics

The database utilized in this study comprised of 643 sets of experimental records gathered from existing research sources30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49. The predictor variables are silica fume (SF), superplasticizer (SP), blast furnace slag (BFS), coarse aggregate (Coarse agg), ordinary Portland cement (OPC), fly ash (FA), water content (WC), fine aggregate (Fine agg), exposure time (t), water to binder ratio (W/B), chloride ions in seawater (Cl content), and annual mean temperature (T). The target variable is the surface chloride concentration (CC) of marine concrete. Table 1 presents a comprehensive statistical overview of the variables considered for analysis. Additionally, Fig. 1 illustrates box plots for each parameter, providing meaningful observations on the data distribution and facilitating the identification of potential outliers. These visual representations are essential for comprehending dataset characteristics and ensuring the robustness of the subsequent modelling processes.

Correlation heatmaps were utilized to evaluate multicollinearity among the variables. The Pearson correlation matrix (Fig. 2) reveals that the correlation coefficient of CC with WC is 0.48, followed by FA (0.38), and T (0.35). Conversely, the correlation coefficient of CC with Exposure type is − 0.50, followed by Fine agg (− 0.32), and SP (− 0.18). Similarly, the Spearman correlation matrix shows that the correlation coefficient of CC with WC is 0.48, followed by FA (0.39), and T (0.31). Conversely, the correlation coefficient of CC with exposure type is − 0.55. Notably, all correlation coefficients remained below 0.8, indicating no significant issues with multicollinearity among the assessed features.

Std: Standard deviation.

Data preprocessing

Before developing the ML models, the dataset was preprocessed to ensure data quality and enhance model performance50. Missing values were addressed using median imputation, which is robust to extreme values and preserves the distribution of the data. Outliers were detected and removed using the isolation forest algorithm with a contamination rate of 5%, retaining only inliers for analysis. The original dataset contained 642 rows, and after outlier removal, 609 rows remained. The cleaned dataset was then split into training and testing sets with a 70:30 ratio to allow unbiased evaluation of model performance51,52. An additional feature corresponding to environmental conditions was incorporated to represent the exposure conditions of concrete structures (Fig. 3). To ensure all features contributed equally to the learning process, min–max scaling was applied, normalizing feature values to the [0, 1] range, which is suitable for the selected machine learning models (ANN, SVR, and hybrid approaches). Additionally, descriptive statistics for both the training and testing sets were computed to verify the consistency and distribution of the preprocessed data, as presented in Table 2. The split preserved the overall distribution, ensuring that both training and testing sets are representative of the cleaned dataset. These preprocessing steps provided a robust foundation for developing accurate and interpretable models for predicting surface chloride concentration in marine concrete. Additionally, the validation of the training and testing datasets was performed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, with the maximum discrepancy (MD) statistic employed as the primary evaluation measure, as summarized in Table 3. The MD represents the maximum absolute difference between the cumulative distribution functions of the two datasets, where values closer to zero indicate stronger consistency. Overall, most variables exhibited minimal discrepancies, reflecting a high degree of distributional similarity between the training and testing datasets.

Hyperparameter tuning

In the model training phase, 70% of the dataset, amounting to 450 data points, is used, whereas the remaining 30%, consisting of 193 data points, is reserved for testing purposes. The development of hybrid ML models involved careful hyperparameter optimization to enhance predictive accuracy. Sensitivity analyses were conducted for GTO, GWO, SVR, and ANN hyperparameters to determine optimal settings, as summarized in Table 4. Performance was evaluated using R2 and RMSE metrics, and the selected value for each parameter was chosen to maximize predictive accuracy while minimizing computational cost. For SVR, different kernels were tested, with RBF achieving the highest R2, outperforming linear and polynomial kernels (Table 5). These analyses confirm that the selected values achieve stable convergence while maximizing predictive performance. Figure 4 depicts the process flow of model development.

Statistical assessment

Each model is rigorously evaluated using various performance metrics to assess its reliability (Fig. 5), with the indicator equations presented in Eqs. 1–5.

where fi represents the observed value, while gi denotes the estimated value. N is the total number of observations, and Em indicates the feature count. A bar over a letter signifies the mean.

Results and discussions

Regression analysis

Regression analysis is pivotal for evaluating the effectiveness of ML models. The regression slopes obtained for the training and testing phases of the hybrid ML models for predicting surface chloride concentration indicate their predictive performance and generalization ability (Fig. 6). The ANN-GTO model exhibited a regression slope of 0.89 in the training phase and 0.90 during testing, suggesting a consistent predictive capability across both phases. The ANN-GWO model exhibited slightly improved performance, achieving regression slopes of 0.90 in the training process and 0.91 in the testing phase. A more refined predictive strength was observed in the SVR-GTO model, which achieved regression slopes of 0.92 in the training process and 0.93 in the testing, reflecting its enhanced capability to identify the fundamental trends within the data. Notably, the ANN-GWO model demonstrated the highest accuracy, with training and testing regression slopes of 0.93 and 0.95, respectively, highlighting superior generalization and reliability in predicting surface chloride concentration. These findings highlight the efficacy of hybrid ML models, particularly ANN-GWO, in delivering precise and robust predictions. Furthermore, Fig. 7 provides a comprehensive assessment of prediction accuracy through a comparison of actual versus predicted values, including error analysis and 95% confidence intervals.

Statistical assessment

The effectiveness of hybrid ML models for predicting CC was analysed using multiple statistical indicators, as shown in Table 6. In the training phase, the SVR-GWO model demonstrated the highest accuracy with an R2 of 0.95, an RMSE of 0.11, and the lowest MAE of 0.07, indicating superior predictive capability. SVR-GTO followed closely with an R2 of 0.93 and an RMSE of 0.21. Among ANN-based models, ANN-GWO performed better than ANN-GTO, attaining an R2 of 0.90 and an RMSE of 0.23. A similar trend was observed during the testing phase, where SVR-GWO surpassed all other models, attaining an R2 of 0.96 and demonstrating an RMSE of 0.11, showcasing its strong generalization ability. SVR-GTO also exhibited robust predictive performance with an R2 of 0.95 and an RMSE of 0.23. The ANN-GWO model maintained a competitive accuracy (R2 = 0.92), outperforming ANN-GTO (R2 = 0.90). Overall, the results highlight the effectiveness of SVR-based hybrid models, particularly SVR-GWO, in accurately predicting surface chloride concentration (Fig. 8).

K-fold cross validation

In this study, a tenfold cross-validation was employed to ensure robust model evaluation53,54, as illustrated in Figs. 9. The average performance metrics, specifically RMSE and R2 values, were calculated to analyse the reliability of each model (Fig. 10). The RMSE scores for the models were as follows: ANN-GTO (0.9175), ANN-GWO (0.833), SVR-GTO (0.628), and SVR-GWO (0.499). In terms of R-squared values, the models achieved the following results: ANN-GTO (0.915), ANN-GWO (0.923), SVR-GTO (0.941), and SVR-GWO (0.951). Additionally, SVR-GWO demonstrated the best performance with the lowest RMSE (0.50 ± 0.03) and highest R2 (0.95 ± 0.03), indicating accurate and consistent predictions across folds (Table 7). These findings demonstrate that the SVR-GWO model exhibited the best performance, indicating its superior predictive capability in comparison to the other models.

SHAP interpretation

Mean SHAP analysis is presented in Fig. 11 (feature importance rankings) and Fig. 12 (individual and cumulative contributions), with detailed quantitative values provided in Table 8. The SHAP analysis reveals a clear hierarchy of feature importance in predicting the CC of marine concrete. Fine agg emerges as the most influential factor with a mean SHAP value of 0.1867, contributing 30.75% to the model’s explanatory power. The second and third most important features are t (mean SHAP = 0.1079, 17.77% contribution) and exposure type (mean SHAP = 0.1035, 17.05% contribution), respectively. Together, these top three features account for 65.58% of the model’s predictive capability. This quantitative SHAP analysis demonstrates that approximately 81% of the model’s explanatory power can be achieved using only the top five features (Fine agg, t, Exposure type, Cl content, and OPC), providing valuable insights for model simplification and practical implementation in marine concrete chloride prediction applications.

The SHAP summary violin plot (Fig. 13) reveals significant trends regarding the influence of various parameters on predicting CC in marine concrete. Fine agg shows a decreasing SHAP value as its content increases, indicating that while it initially has a strong positive influence, its effectiveness diminishes at higher levels. Similarly, exposure type declines in influence with increased exposure levels, suggesting that extreme conditions may reduce its beneficial effects. In contrast, the parameter t exhibits an increasing SHAP value with higher levels, reflecting its strong positive relationship with the outcome. Cl content also shows a rising SHAP value with greater proportions, highlighting its crucial role in enhancing the outcome. Likewise, parameter T also exhibits an increasing SHAP value as its content rises. Overall, these findings underscore the varying degrees of influence different parameters have on the durability and performance of marine concrete, emphasizing the importance of optimizing their composition for improved outcomes.

PDP interpretation

Partial dependence plots (PDPs) serve as effective visual aids in ML for examining the relationships between predictor variables and the target outcome55,56. These plots illustrate the expected value of the target variable across different levels of a specific predictor, while controlling the effects of other predictors57. By doing so, PDPs provide insights into how changes in a given predictor can influence predictions, facilitating a better understanding of the model’s behavior and the underlying relationships within the data58.

Figure 14 illustrates the PDPs of various parameters affecting CC in marine concrete. CC remains nearly constant with an increase in OPC up to 330 kg/m3, rises sharply between 330 and 340 kg/m3, and then shows a slight decrease beyond 340 kg/m3. GGBS shows a marginal increase in CC, while FA, BFS, SP, and WC exhibit negligible influence, maintaining CC almost constant. Fine agg causes a slight reduction in CC up to 640 kg/m3, followed by a sharp decline between 640 and 660 kg/m3, after which CC stabilizes. Coarse aggregate has little effect up to 860 kg/m3, but CC rises slightly between 1200 and 1220 kg/m3. Regarding service life, CC increases rapidly during the first 10 years and then stabilizes. T shows a slight decline in CC up to 27 °C, followed by a sharp increase between 27–28 °C, after which CC plateaus. Chloride content has little effect overall, except for a rise between 19–20 g/L. Exposure type strongly influences CC, with sharp increases from type 0 to 1 and 1 to 2. These insights highlight the complex nonlinear effects of mix proportions and environmental conditions on chloride penetration, underlining the importance of parameter optimization in concrete mix design to enhance durability in marine environments.

The patterns observed in the SHAP and PDP analyses can be explained through well-established material science concepts. The strong contribution of Fine agg arises from their ability to densify the concrete matrix and block chloride pathways; however, excessive fine content can increase the demand for mixing water, which in turn elevates porosity and reduces resistance to chloride ingress59. The pronounced role of exposure type is consistent with field evidence showing that harsher marine conditions supply more available chlorides, thereby accelerating their penetration into concrete60. The effect of temperature is also notable: higher temperatures enhance ion movement and can speed up hydration reactions, which may initially benefit early-age strength but ultimately increase the rate of chloride diffusion61,62. Similarly, external chloride concentration acts as a driving force for diffusion, with higher levels intensifying chloride transport. By linking these ML-derived insights to underlying physical and chemical processes, the interpretations demonstrate that the observed patterns are not simply data-driven correlations but reflect fundamental mechanisms that govern the durability of marine concrete.

User interface for practical applications

A graphical user interface (GUI) has proven effective in enabling researchers and engineers to make quick, well-informed decisions in real-time for structural applications63,64. This study introduces a user-friendly interface, shown in Fig. 15, that enables users to enter key parameters and generate CC predictions. The interface provides real-time CC predictions with quantified uncertainty (standard deviation 0.06% wt., 95% confidence interval ± 0.12% wt.) in ~ 0.02 s per sample, making it computationally efficient and practical for real-world applications. By removing the necessity for extensive and time-consuming experiments, this tool streamlines the prediction process. Providing fast and precise estimates, the GUI is a pivotal resource for industry professionals and researchers, promoting the effective implementation of advanced ML techniques in construction.

Comparative analysis with prior studies utilizing the identical dataset

Several studies have demonstrated the efficacy of ML techniques in predicting CC in marine concrete, as summarized in Table 9. For example, ensemble ML models have been shown to outperform other conventional approaches in CC prediction1. Similarly, adaptive ensemble models have achieved superior predictive accuracy compared to alternative algorithms2. A conjugate gradient–optimized backpropagation neural network (CG-BP ANN) reported an R2 of 0.913. In the present study, the proposed SVR-GWO hybrid model achieved the highest predictive performance, with an R2 of 0.96, highlighting its improved accuracy relative to previously reported methods.

Conclusion

In this study, advanced hybrid ML approaches were employed to create a reliable model for predicting CC in marine concrete, eliminating the necessity for labour-intensive and expensive physical experiments. The study combined SVR and ANN with metaheuristic optimization algorithms, specifically gorilla troops optimization and grey wolf optimization, resulting in the development of four innovative hybrid ML models. Moreover, the SHAP method was applied to enhance the understanding of model predictions. Furthermore, PDP analysis was conducted to provide further insights. The principal findings from this research are summarized below.

-

All the models exhibited strong performance, with SVR-GWO proving to be the optimal selection. Notably, SVR-GWO demonstrated the highest R2 of 0.96, highlighting its exceptional forecasting accuracy relative to SVR-GTO (0.95), ANN-GWO (0.92), and ANN-GTO (0.90). Additionally, SVR-GWO achieved the lowest RMSE (0.11), indicating its effectiveness in predicting CC with minimal error compared to experimental data.

-

The SHAP scores underscore the notable impact of various parameters on the model’s estimations. Among the features examined, Fine agg emerges as the most influential, followed by exposure type, t, and Cl content. This hierarchy of importance is further validated by the PDPs.

-

The SHAP summary plot distinctly shows a strong negative correlation between Fine agg and CC. It also highlights the negative impact of Exposure type value on CC, while indicating that t and Cl content positively influence CC. These findings offer essential guidance for improving the CC of marine concrete, thereby enhancing its effectiveness and durability in practical applications.

-

A user interface has been designed to allow users to enter key inputs and seamlessly obtain CC predictions.

The findings of the study are crucial for the maintenance and design of marine concrete structures. Utilizing advanced hybrid ML models along with SHAP and PDP analyses provides a robust framework for accurately estimating CC. The superior performance of SVE-GWO and its insights from SHAP and PDP equip engineers with powerful tools to optimize and enhance the durability of marine concrete.

Data availability

The data used in this study were obtained from references[30–49] and are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Abbreviations

- CC:

-

Surface chloride concentration

- FHWA:

-

Federal highway administration

- GDP:

-

Gross domestic product

- ML:

-

Machine learning

- R2 :

-

Coefficient of determination

- SVM:

-

Support vector machine

- KNN:

-

K-nearest neighbors

- RF:

-

Random forest

- XGBoost:

-

Extreme gradient boosting

- LightGBM:

-

Light gradient boosting machine

- DT:

-

Decision tree

- FA:

-

Fly ash

- RAC:

-

Recycled aggregate concrete

- ANN:

-

Artificial neural network

- GEP:

-

Gene expression programming

- BPFRC:

-

Basalt and polypropylene fiber-reinforced concrete

- PSO:

-

Particle swarm optimization

- SVR:

-

Support vector regression

- PDPs:

-

Partial dependence plots

- SHAP:

-

Shapley additive explanations

References

Taffese, W. Z. & Espinosa-Leal, L. Prediction of chloride resistance level of concrete using machine learning for durability and service life assessment of building structures. J. Build. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2022.105146 (2022).

Reimann, L., Vafeidis, A. T. & Honsel, L. E. Population development as a driver of coastal risk: Current trends and future pathways,. Camb. Prism. Coast. Futur. https://doi.org/10.1017/cft.2023.3 (2023).

Liu, J. et al. Atmospheric chloride deposition in field concrete at coastal region. Constr. Build. Mater. 190, 1015–1022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.09.094 (2018).

Liu, J. et al. Understanding the interacted mechanism between carbonation and chloride aerosol attack in ordinary Portland cement concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 95, 217–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2017.02.032 (2017).

Liu, J. C. et al. Influenza vaccination reduces hemorrhagic stroke risk in patients with atrial fibrillation: A population-based cohort study. Int. J. Cardiol. 232, 315–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.12.074 (2017).

Yang, L. F., Cai, R. & Yu, B. Investigation of computational model for surface chloride concentration of concrete in marine atmosphere zone. Ocean Eng. 138, 105–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2017.04.024 (2017).

Bao, J., Wei, J., Zhang, P., Zhuang, Z. & Zhao, T. Experimental and theoretical investigation of chloride ingress into concrete exposed to real marine environment. Cem. Concr. Compos. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2022.104511 (2022).

Andrade, C., Castellote, M. & D’Andrea, R. Measurement of ageing effect on chloride diffusion coefficients in cementitious matrices. J. Nucl. Mater. 412, 209–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnucmat.2010.12.236 (2011).

Koch, G.H., Brongers, M.P., Thompson, N.G., Virmani, Y.P. and Payer, J.H. Corrosion costs and preventive strategies in the United States. Tech rep, U.S. Department of tranportation Federal Highway Administration, CC Technologies Laboratories, Inc. and NACE international, (2002).

Chatterji, S. On the applicability of Fick’s second law to chloride ion migration through portland cement concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 25, 299–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/0008-8846(95)00013-5 (1995).

Cai, R., Yu, M., Hu, Y., Yang, L. & Ma, H. Influence of data acquisition and processing on surface chloride concentration of marine concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.121705 (2021).

Yang, L. F., Wang, L. & Yu, B. Time-varying behavior and its coupling effects with environmental conditions and cementitious material types on surface chloride concentration of marine concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.124578 (2021).

Tipu, R. K., Batra, V., Suman, K. S. & Pandya, V. R. P. Enhancing load capacity prediction of column using eReLU-activated BPNN model. Structures https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2023.105600 (2023).

Hosseinzadeh, M., Mousavi, S. S., Hosseinzadeh, A. & Dehestani, M. An efficient machine learning approach for predicting concrete chloride resistance using a comprehensive dataset. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-42270-3 (2023).

Tipu, R. K., Arora, R. & Kumar, K. Machine learning-based prediction of concrete strength properties with coconut shell as partial aggregate replacement: A sustainable approach in construction engineering, Asian. J. Civ. Eng. 25, 2979–2992. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42107-023-00957-y (2024).

Singh, R., Tipu, R. K., Mir, A. A. & Patel, M. Predictive modelling of flexural strength in recycled aggregate-based concrete: A comprehensive approach with machine learning and global sensitivity analysis. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. - Trans. Civ. Eng. 49, 1089–1114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40996-024-01502-w (2025).

Marks, M., Glinicki, M. A. & Gibas, K. Prediction of the chloride resistance of concrete modified with high calcium fly ash using machine learning. Materials https://doi.org/10.3390/ma8125483 (2015).

Liu, K. H., Zheng, J. K., Pacheco-Torgal, F. & Zhao, X. Y. Innovative modeling framework of chloride resistance of recycled aggregate concrete using ensemble-machine-learning methods. Constr. Build. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.127613 (2022).

Xu, C. et al. Numerical and machine learning models for concentrically and eccentrically loaded CFST columns confined with FRP wraps. Struct. Concr. https://doi.org/10.1002/suco.202400541 (2024).

Hoque, M. A., Shrestha, A., Sapkota, S. C., Ahmed, A. & Paudel, S. Prediction of autogenous shrinkage in ultra-high-performance concrete (UHPC) using hybridized machine learning, Asian. J. Civ. Eng. 26, 649–665. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42107-024-01212-8 (2025).

Chhetri Sapkota, S., Dahal, D., Yadav, A., Dhakal, D. & Paudel, S. Analyzing the behavior of geopolymer concrete with different novel machine-learning algorithms. J. Struct. Des. Constr. Pract. https://doi.org/10.1061/jsdccc.sceng-1724 (2025).

Sapkota, S. C. et al. Optimizing high-strength concrete compressive strength with explainable machine learning. Multiscale Multidiscip. Model. Exp. Des. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41939-025-00737-y (2025).

Taffese, W. Z. & Espinosa-Leal, L. A machine learning method for predicting the chloride migration coefficient of concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.128566 (2022).

Wang, R. et al. Machine learning method to explore the correlation between fly ash content and chloride resistance. Materials (Basel). https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17051192 (2024).

Ahmad, A., Farooq, F., Ostrowski, K. A., Śliwa-Wieczorek, K. & Czarnecki, S. Application of novel machine learning techniques for predicting the surface chloride concentration in concrete containing waste material. Materials https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14092297 (2021).

Sun, Z., Li, Y., Li, Y., Su, L. & He, W. Prediction of chloride ion concentration distribution in basalt-polypropylene fiber reinforced concrete based on optimized machine learning algorithm. Mater. Today Commun. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtcomm.2023.106565 (2023).

Tipu, R. K., Batra, V., Suman, V. R. & Panchal, K. S. P. Predictive modelling of surface chloride concentration in marine concrete structures: A comparative analysis of machine learning approaches, Asian. J. Civ. Eng. 25, 1443–1465. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42107-023-00854-4 (2024).

Lv, W. et al. Hybrid machine learning-based model for predicting chloride ion concentration in coral aggregate concrete and its ethically aligned graphical user interface design. Mater. Today Commun. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtcomm.2023.107053 (2023).

Ma, X. R., Liang, X., Wang, S. & Chen, S. Z. Language model enhanced surface chloride concentration determination for concrete within splash environment based on limited field records. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2024.e03157 (2024).

Costa, A. & Appleton, J. Chloride penetration into concrete in marine environment—Part I: Main parameters affecting chloride penetration. Mater. Struct. Constr. 32, 252–259. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02479594 (1999).

Nanukuttan, S. V., Basheer, L., McCarter, W. J., Robinson, D. J. & Basheer, P. M. Full-scale marine exposure tests on treated and untreated concretes-initial 7-year results. ACI Mater. J. 105(1), 81–87 (2008).

Tran, A. T., Le, T. H. & Nguyen, H. M. Forecast of surface chloride concentration of concrete utilizing ensemble decision tree boosted. J. Sci. Transp. Technol. 2, 44–56. https://doi.org/10.58845/jstt.utt.2022.en57 (2022).

Khanzadeh Moradllo, M., Sadati, S. & Shekarchi, M. Quantifying maximum phenomenon in chloride ion profiles and its influence on service-life prediction of concrete structures exposed to seawater tidal zone—A field oriented study. Constr. Build. Mater. 180, 109–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.05.284 (2018).

Zhang, Y. R., Zhang, Y., Huang, J., Zhuang, H. X. & Zhang, J. Z. Time dependence and similarity analysis of peak value of chloride concentration of concrete under the simulated chloride environment. Constr. Build. Mater. 181, 609–617. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.06.030 (2018).

Wang, Y., Wu, L., Wang, Y., Li, Q. & Xiao, Z. Prediction model of long-term chloride diffusion into plain concrete considering the effect of the heterogeneity of materials exposed to marine tidal zone. Constr. Build. Mater. 159, 297–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.10.083 (2018).

Thomas, M. D. A. & Bamforth, P. B. Modelling chloride diffusion in concrete effect of fly ash and slag. Cem. Concr. Res. 29, 487–495. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0008-8846(98)00192-6 (1999).

Pang, L. & Li, Q. Service life prediction of RC structures in marine environment using long term chloride ingress data: Comparison between exposure trials and real structure surveys. Constr. Build. Mater. 113, 979–987. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.03.156 (2016).

Alizadeh, R. et al. Effect of curing conditions on the service life design of RC structures in the Persian Gulf region. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 20, 2–8. https://doi.org/10.1061/(asce)0899-1561(2008)20:1(2) (2008).

Dousti, A., Rashetnia, R., Ahmadi, B. & Shekarchi, M. Influence of exposure temperature on chloride diffusion in concretes incorporating silica fume or natural zeolite. Constr. Build. Mater. 49, 393–399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2013.08.086 (2013).

Lindvall, A. Chloride ingress data from field and laboratory exposure—Influence of salinity and temperature. Cem. Concr. Compos. 29, 88–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2006.08.004 (2007).

Chalee, W., Jaturapitakkul, C. & Chindaprasirt, P. Predicting the chloride penetration of fly ash concrete in seawater. Mar. Struct. 22, 341–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marstruc.2008.12.001 (2009).

Pack, S. W., Jung, M. S., Song, H. W., Kim, S. H. & Ann, K. Y. Prediction of time dependent chloride transport in concrete structures exposed to a marine environment. Cem. Concr. Res. 40, 302–312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2009.09.023 (2010).

Valipour, M., Pargar, F., Shekarchi, M., Khani, S. & Moradian, M. In situ study of chloride ingress in concretes containing natural zeolite, metakaolin and silica fume exposed to various exposure conditions in a harsh marine environment. Constr. Build. Mater. 46, 63–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2013.03.026 (2013).

O. Markeset, G., & Skjølsvold. Time dependent chloride diffusion coefficient : Field studies of concrete exposed to marine environment in Norway, (2010).

Farahani, A., Taghaddos, H. & Shekarchi, M. Prediction of long-term chloride diffusion in silica fume concrete in a marine environment. Cem. Concr. Compos. 59, 10–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2015.03.006 (2015).

Safehian, M. & Ramezanianpour, A. A. Prediction of RC structure service life from field long term chloride diffusion. Comput. Concr. 15, 589–606. https://doi.org/10.12989/cac.2015.15.4.589 (2015).

Xu, J. & Li, F. Analytical model for load dependence of chloride penetration into concrete. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1061/(asce)mt.1943-5533.0001823 (2017).

Mohammed, T. U. & Hamada, H. Relationship between free chloride and total chloride contents in concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 33, 1487–1490. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0008-8846(03)00065-6 (2003).

Safehian, M. & Ramezanianpour, A. A. Assessment of service life models for determination of chloride penetration into silica fume concrete in the severe marine environmental condition. Constr. Build. Mater. 48, 287–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2013.07.006 (2013).

Wani, S. R. & Suthar, M. Using soft computing to forecast the strength of concrete utilized with sustainable natural fiber reinforced polymer composites, Asian. J. Civ. Eng. 25, 5847–5863. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42107-024-01150-5 (2024).

Wani, S. R. & Suthar, M. A Comparative analysis of the predictive performance of tree-based and artificial neural network approaches for compressive strength of concrete utilising waste. Int. J. Pavement Res. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42947-024-00454-8 (2024).

Wani, S. R. & Suthar, M. Utilizing machine learning approaches within concrete technology offers an intelligent perspective towards sustainability in the construction industry: A comprehensive review. Multiscale Multidiscip. Model. Exp. Des. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41939-024-00601-5 (2025).

Shrestha, A. & Sapkota, S. C. Hybrid machine learning model to predict the mechanical properties of ultra-high-performance concrete (UHPC) with experimental validation, Asian. J. Civ. Eng. 25, 5227–5244. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42107-024-01109-6 (2024).

Sapkota, S. C., Sapkota, S. & Saini, G. Prediction of split tensile strength of recycled aggregate concrete leveraging explainable hybrid XGB with optimization algorithm. Multiscale Multidiscip. Model. Exp. Des. 7, 4343–4359. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41939-024-00480-w (2024).

Friedman, J. H. Greedy function approximation: A gradient boosting machine. Ann. Stat. 29, 1189–1232. https://doi.org/10.1214/aos/1013203451 (2001).

Kashem, A. et al. Hybrid data-driven approaches to predicting the compressive strength of ultra-high-performance concrete using SHAP and PDP analyses. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2024.e02991 (2024).

Goldstein, A., Kapelner, A., Bleich, J. & Pitkin, E. Peeking Inside the black box: Visualizing statistical learning with plots of individual conditional expectation. J. Comput. Graph. Stat. 24(1), 44–65 (2015).

Rajczakowska, M., Szeląg, M., Habermehl-Cwirzen, K., Hedlund, H. & Cwirzen, A. Interpretable machine learning for prediction of post-fire self-healing of concrete. Materials https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16031273 (2023).

Abdelrahman, M. & Xi, Y. The effect of w/c ratio and aggregate volume fraction on chloride penetration in non-saturated concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 191, 260–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.10.013 (2018).

Jiang, H. et al. Durability life evaluation of marine infrastructures built by using carbonated recycled coarse aggregate concrete due to the chloride corrosive environment. Front. Mar. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2024.1357186 (2024).

Dhir, R. K., Jones, M. R. & Elghaly, A. E. PFA concrete: Exposure temperature effects on chloride diffusion. Cem. Concr. Res. 23, 1105–1114. https://doi.org/10.1016/0008-8846(93)90170-E (1993).

Li, D., Yuan Li, L. & Wang, X. Chloride diffusion model for concrete in marine environment with considering binding effect. Mar. Struct. 66, 44–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marstruc.2019.03.004 (2019).

Asif, U., Khan, W. A., Naseem, K. A. & Rizvi, S. A. S. Enhancing the predictive accuracy of marshall design tests using generative adversarial networks and advanced machine learning techniques. Mater. Today Commun. 45, 112379 (2025).

Sapkota, S. C., Yadav, A., Khatri, A., Singh, T. & Dahal, D. Explainable hybridized ensemble machine learning for the prognosis of the compressive strength of recycled plastic-based sustainable concrete with experimental validation. Multiscale Multidiscip. Model. Exp. Des. 7, 6073–6096. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41939-024-00567-4 (2024).

Cai, R. et al. Prediction of surface chloride concentration of marine concrete using ensemble machine learning. Cem. Concr. Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2020.106164 (2020).

Tipu, R. K., Panchal, V. R. & Pandya, K. S. Enhancing chloride concentration prediction in marine concrete using conjugate gradient-optimized backpropagation neural network, Asian. J. Civ. Eng. 25, 637–656. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42107-023-00801-3 (2024).

Funding

No funding was received to support the conduct of this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Irfan Ullah: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Software, Supervision, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. Hisham Alabduljabbar: Funding acquisition, Investigation, Resources, Software. Muhammad Faisal Javed: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Supervision. Abdulaziz Alaskar: Funding acquisition, Investigation, Resources, Software. Waseem Ullah Khan: Conceptualization, Software, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. Furqan Ahmad: Funding acquisition, Investigation, Resources, Software.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ullah, I., Alabduljabbar, H., Javed, M.F. et al. Estimating the surface chloride concentration of marine concrete utilizing advanced hybrid machine learning models. Sci Rep 15, 40442 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23944-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23944-6