Abstract

The prevalence of type 2 diabetes (T2M) has been increasing drastically in recent two decades. One of the main underlying pathophysiology was decreased insulin secretion (ISEC). Even though there were many studies found the related factors affecting ISEC, no study used multiple adaptive regression spline (MARS) to build an equation estimating ISEC. In the present study, we used MARS to estimate hemostasis assessment model of β-cell (HOMA-β) in healthy Taiwanese men. Totally, there were 317 men enrolled. Participants who were taking medications related to metabolic syndrome were excluded. MARS was used to build an equation to estimate HOMA-β. Multiple linear regression (MLR) was taken as a bench mark for comparing the accuracy with MARS. The method with less estimation errors was considered to be more accurate. All the estimation errors were smaller for MARS. This indicated that MARS outperformed MLR. The equation built is shown below. The r2 of this equation was 0.58. By using MARS, we built an equation which could accurately estimate HOMA-β in a healthy Taiwanese men cohort. The most important factor was HB, followed by TB, education level, sport area, GOT, GPT, and BF. This equation has a practical clinical use and could further explore which were the factors that were related to ISEC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is widely considered as an important chronic disease nowadays. The prevalence of T2D has been increasing in recent three decades. There are two direct known causes for this trend. First, improvement of medical care which prolongs the life expectancy of human being. Aging is directly related to occurrence of T2D1. Secondly, the higher percentage of overweight and obese also contribute to this issue2. The International Diabetes Federation published an estimation of prevalence from 2019 to 2030. In 2019, the global prevalence of T2D was 9.3% world-widely. This number will rise to 10.2% by 2030. Moreover, approximately 50% of these patients do not know they have diabetes3. In Taiwan, similar trend was also noted. From 1985 to 1996, the prevalence increased from 4.9% to 9.2% and it is estimated to reach 11.2% in 20304. The cost for taking care of diabetes is composed of three parts; patients with T2D, private and public payers and governments. It has grown from 232 to 966 billion from 2007 to 20215.

From the data of United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study, cardiovascular diseases would be significantly lower in the group of intensive care6. This information indicates that T2D is not a serious disease if controlled well. However, it is still the top 9th cause of death in the world7.

It is a consensus that there are two underlying pathophysiology for T2D; increased insulin resistance (IR) and decreased insulin secretion (ISEC). The course of occurrence of T2D starts from the IR. IR is inherited from the parents8. Because of this derangement, β-cell begins to compensate by increasing ISEC. Averagely, at the age of 45 years old, exhaustion of β-cell starts and blood glucose becomes higher9.

There are many methods proposed to quantify ISEC, from the least to the most complex, such as homeostasis model assessment -insulin secretion (HOMA-β), oral glucose tolerance test, intravenous glucose tolerance test, and hyperglycemic clamp10,11,12,13. Even though other methods are more precise, but they are expensive and labor-intensive. Compared to these methods, HOMA-β only needs fasting plasma glucose and insulin (FPG, FPI) to calculate β-cell functions. The drawbacks of HOMA-β are beyond the scope of the present study.

Many factors were found to be related to β-cell function such as diet, body weight, aging, sleeping pattern, smoking, and liver function14,15,16,17,18. These studies all used traditional statistical methods such as multiple logistic regression and multiple linear regression (MLR). Recently, the advanced development of artificial learning techniques is impressive and these machine learning methods are widely applied in many medical researches. Among these methods, multivariate adaptive regression spline (MARS) could provide a specific equation which is different from other methods commonly being described as ‘black-box’. It could capture non-linear relationships between variables. This unique characteristic makes MARS outperforms than traditional multiple linear regression (MLR) in predicting the dependent variable. Because using MARS in clinical research has just begun and many researchers do not appreciate this method. However, it has been used in many other research fields. For example, in Turkey, the buffalo breeders wanted to measure the body weight of buffalos which is a difficult task and needs heavy equipment’s. To solve this problem, they put information such as tail length, shoulder height, and withers height, et al. into the MARS model and the body weight could be estimated precisely19. In the present study, by using MARS, we were going to build an equation with demographic, biochemistry, and lifestyle data to estimate HOMA-β in group of healthy Taiwanese men.

Methods

Participant selection

Some of the following contexts were published in our previous study20. Data for this study were sourced from the Taiwan MJ cohort, an ongoing prospective cohort of health examinations conducted by the MJ Health Screening Centers in Taiwan. These examinations cover more than 100 important biological indicators, including anthropometric measurements, blood tests, imaging tests, etc. Each participant completed a self-administered questionnaire to collect information of personal and family medical history, current health status, lifestyle, physical exercise, sleep habits, and dietary habits. The data of our study participants were obtained from MJ clinic. At the time when the participants had the health checkup, a general consent forms for future anonymous study were obtained. This database was kept and maintained by the MJ Health Research Foundation. All or part of the data used in this research were authorized by and received from MJ Health Research Foundation (Authorization Code: MJHRF2024003A). Any interpretations or conclusions described in this paper do not represent the views of MJ Health Research Foundation. The present study is a secondary database analysis and does not involve sample collection, so there is no consent form for this research project. For the data collection procedures, please refer to the technical report annually21 and all informed consents were obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardian(s). The present study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Tri-Service General Hospital (IRB No.: A202405007) and all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. As it was a secondary study, only a short review was taken.

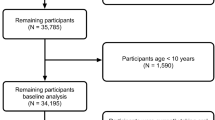

In the beginning, 1533 people were enrolled. After excluding subjects who did not fit our criteria, 317 men were left for further analysis (Fig. 1). The exclusion criteria were:

-

1.

Women.

-

2.

With diagnosis of diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia.

-

3.

With taking medications for metabolic syndrome.

-

4.

With any history of significant medical diseases such as cancer.

Measurements of anthropometry and biochemistry

Part of the following contain was published by our team and it could be referred to20. On the day of examination, a senior nurse recorded the people’s personal history including smoking, alcohol drinking, education level, betel nuts using. Body weight (kilogram) was examined by electronic body weight meter. Systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) were measured using electric sphygmomanometer.

Blood samples were obtained after a 10-hour fasting period. Within one hour of collection, plasma was separated from the blood and stored at -30 degrees Celsius until lipid profile analysis. Total cholesterol and triglyceride (TG) levels were measured using a dry, multilayer analytical slide method, employing the Fuji Dri-Chem 3000 analyzer (Fuji Photo Film, Tokyo, Japan). Serum high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) concentrations were determined through an enzymatic cholesterol assay following dextran sulfate precipitation. Insulin was obtained through chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay (CMIA).

Traditional statistics

Data are represented as means ± standard deviations. The education level was ordinal variables and analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied. Pearson’s correlation was used for analyze the relationships between all the continuous variables and HOMA-β. MLR was performed here and was taken as a bench marker for comparison to Mach-L. To account for multiple testing, we applied the false discovery rate (FDR) correction to correlation analyses. All statistical tests were two-sided, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 10.0 for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Description of the study data set

In this study, Table 1 provides definitions for 28 clinical variables. We gathered the following dependent variables from our study participants: body fat (BF), leukocyte count, hemoglobin level, platelet count, total bilirubin (TB), total protein, albumin, globulin, alkaline phosphatase, Glutamic Oxaloacetic Transaminase (GOT), Glutamic Pyruvic Transaminase (GPT), gamma-glutamyltransferase (γ-GT), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), creatinine, uric acid, triglyceride (TG) level, HDL-C (high-density lipoprotein cholesterol) level, LDL-C (low-density lipoprotein cholesterol) level, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level, C-reactive protein (CRP) level, bone mineral density, educational level, marriage status, drinking area, smoking area, betel nut area, sport area, sleep time SBP and DBP level. Additionally, age and fasting glucose levels were also recorded for each participant. The drinking area was defined as the multiple of total drinking duration, frequency of drinking and the percentage of alcohol. Similarly, the smoking area was the multiple of the duration, frequency of smoking and number of cigarettes. The sport area was the multiple of duration, frequency, and type of the exercise. The sleep time was an ordinal variable as shown in Table 1. Finally, the equation of HOMA-β = (360 X insulin level)/(plasma glucose level-63). The units were U/mL for insulin and mg/dL for glucose, respectively.

Data splitting and external validation

The dataset was first screened to remove rows with missing outcome values (HOMA-β). To evaluate model generalizability, we randomly split the data into a training set (80%) and a test set (20%) using stratified sampling on the target variable. The test set was held out and only used for external validation.

Missing data imputation

Missing values among predictor variables were addressed through median imputation. We applied the preProcess() function from the caret package to the training set to learn median values and then applied the same transformation to the test set. The imputation was restricted to predictors, preserving the integrity of the outcome variable22.

MARS model development and cross-validation

We used MARS implemented via the earth package for flexible, non-parametric modeling23,24. To prevent overfitting and optimize the model’s complexity, we employed 5-fold cross-validation on the training set22. The model was tuned over a grid of:

-

Number of basis functions (nprune): ranging from 2 to 10.

-

Maximum interaction degree (degree): set to 1 (main effects only) The tuning process was performed using the train() function in caret, and the optimal configuration was selected by minimizing the cross-validated Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE). This procedure approximates the Generalized Cross-Validation (GCV) criterion traditionally used in MARS22,23.

Model evaluation and calibration assessment

Once the model was trained, predictions were generated on the independent test set. We assessed model performance using coefficient of determination (R2), RMSE, and Mean Absolute Error (MAE), calculated from the observed versus predicted values25.

To evaluate model calibration, we constructed a calibration plot by plotting predicted values against observed HOMA-β levels in the test set (Fig. 2). A linear regression line was fitted to the points, and an identity line (slope = 1, intercept = 0) was overlaid for reference. Discrepancies between the calibration line and identity line were interpreted as systematic prediction bias26.

Software and reproducibility

All analyses were conducted in R (version 4.0.5) using the caret, earth, ggplot2, and yardstick packages. The complete modeling workflow, including data preprocessing, model training, hyperparameter tuning, prediction, and performance evaluation, was scripted to ensure reproducibility22,24,25,26.

Results

Participant characteristics

In the study, 317 men were included after applying the inclusion criteria, as detailed in the patient selection process. Table 1 showed the means and standard deviations of all our participants. The average age was 36.4 ± 8.81 years, and BF was 24.85 ± 6.2%. HOMA-β, the independent variable, had a mean of 83.84 ± 42.87 100uU/mg.

Anthropometric and biochemical measurements

The anthropometric and biochemical variables collected BF, leukocyte count, hemoglobin level, platelet count, TB, total protein, albumin, globulin, alkaline phosphatase, GOT, GPT, γ-GT, LDH, creatinine, uric acid, TG, level, HDL-C, LDL-C, TSH level, CRP level, bone mineral density, systolic blood pressure SBP, and DBP. Lifestyle factors such as educational level, marriage status, drinking area, smoking area, betel nut area, sport area, and sleep time were also recorded, as described in the methods.

Statistical analysis findings

The r values of correlations between each variable and HOMA-β are shown in Table 2. HOMA-β was positively correlated with SBP, DBP, BF, WBC, HGB, PLT, ALB, ALK, GOT, GPT, GGT, UA, TG, LDL-C, hs-CRP, BMD, and CBN. At the same time, it was negatively correlated with age, TB, and HDL-C. These correlations were analyzed using Pearson’s correlation, with statistical significance set at p < 0.05, as described in the traditional statistics methods. From the FDR, it is noted that the main findings remained significant after FDR adjustment.

Data set characteristics

The dataset comprised 28 clinical variables, as detailed in Table 1. The drinking area was defined as the multiple of total drinking duration, frequency of drinking, and the percentage of alcohol. Similarly, the smoking area was the multiple of the duration, frequency of smoking, and number of cigarettes. The sport area was the multiple of duration, frequency, and type of exercise. Sleep time was recorded as an ordinal variable. The HOMA-β equation used was HOMA-β = (360 × insulin level)/(plasma glucose level-63), with units of U/mL for insulin and mg/dL for glucose.

Data splitting and external validation

The dataset was screened to remove rows with missing HOMA-β values and split into a training set (80%) and a test set (20%) using stratified sampling to ensure representative distribution of the target variable. This strategy enabled robust model development and external validation, with the test set reserved exclusively for validation purposes.

Missing data imputation

Missing values in predictor variables were handled via median imputation, performed using only the training data to prevent information leakage. The imputation model was applied to the test set using the same transformation parameters.

MARS model development and cross-validation

We developed a multivariate adaptive regression splines (MARS) model to predict HOMA-β levels using demographic and biochemical variables. To optimize model performance, we employed 5-fold cross-validation on the training set using the caret package. The number of basis functions (nprune, range: 2–10) and the maximum degree of interaction (degree, 1 or 2) were systematically tuned. Model selection was guided by minimizing the cross-validated root mean squared error (RMSE), which approximates the generalized cross-validation (GCV) criterion used in spline-based methods. In the present study, 16 basis functions were defined, with each indicating a change in the slope of the corresponding variable. For example, for basis function B1 (SBP), when SBP was higher than 102 (e.g., 104), the Max function selected the higher value in (0, 2), resulting in -11.424. When SBP was lower than 102 (e.g., 100), the Max function selected 0, yielding a result of 0. An equation built with these basis functions is shown in Fig. 3.

Model evaluation and calibration

Model performance was evaluated on the unseen test set. The predictive accuracy was quantified using multiple metrics, including R², RMSE, and MAE. The R² was 0.489, indicating that approximately half of the variance in HOMA-β could be explained by the predictors. The RMSE and MAE were 37.69 and 29.90, respectively, reflecting moderate prediction accuracy (Table 3). From Table 4, it was evident that all estimation errors were smaller for MARS compared to MLR, indicating that the MARS model outperformed the MLR model. A calibration plot was generated to assess the agreement between predicted and observed HOMA-β values on the test set (Fig. 2). The calibration curve (blue) deviated from the ideal reference line (red dashed), indicating some degree of systematic underestimation for higher HOMA-β values. However, the overall directionality and alignment support that the model retained meaningful calibration26. The presence of an external test set and independent calibration analysis helps to mitigate concerns related to overfitting and enhances the generalizability of our findings. For risk factors with multiple basis functions, corresponding figures (Figs. 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10) provide clearer insights into their relationships with HOMA-β. Tables 5 show that TB had the highest coefficient, followed by GOT, BF, SBP, DBP, GPT, and LDH.

Software and reproducibility

The analyses were conducted using R (version 4.0.5) with the caret, earth, ggplot2, and yardstick packages, ensuring reproducibility of the findings through a scripted workflow that encompassed data preprocessing, model training, hyperparameter tuning, prediction, and performance evaluation. For transparency and reproducibility, a complete coefficient list and the corresponding spreadsheet/code should be provided as Supplementary Material. It displays the hidden Max function in an Excel file, allowing easy computation of HOMA-β by copying and pasting the contents into an Excel application.

Discussion

In the present study, we used MARS to do two things: (1) Built an equation which could estimate HOMA-β; (2) Identified which were the most relevant factors for HOMA-β. Our results showed that, according to the order of coefficients, the most important factor was TB, followed by GOT, BF, SBP, DBP, GPT and LDH. The r2 of our equation was 0.71 which could be considered quite high and indicated that the equation was relatively accurate in Taiwanese men.

Unlike traditional methods for evaluating insulin secretion—which require specialized procedures like glucose tolerance tests—our MARS-based equation offers a practical alternative using standard clinical variables. By inputting routinely collected data (e.g., TB, liver enzymes, blood pressure, BF) into a simple Excel tool (Supplemental Material), clinicians can estimate HOMA-β without the need for insulin assays. This approach may assist in early detection of β-cell dysfunction and support preventive strategies in primary care.

Indeed, HOMA-β is conventionally calculated from FPG and insulin levels and is relatively straightforward in research settings. However, insulin measurement is not always routinely available in many clinical or community health check-up settings due to cost, lack of standardization across labs, and limited accessibility—especially in primary care or low-resource environments. Our MARS-based model provides an indirect yet practical solution by estimating HOMA-β using easily obtainable variables from standard biochemical and lifestyle data. This may allow broader screening of β-cell function in populations where direct insulin measurements are not feasible.

To our knowledge, little is studied on the relationship between TB and ISEC. In our study, it was selected as the most important factors with the coefficient as high as 58.64 (Fig. 9). For TB, there were two BF which meant that when TB was less than 1.43, the slope was less steep than those with TB higher than 1.48 (22.25 vs. 58.64). Only one study investigated the correlation between C-peptide and bilirubin levels in Korean type 2 diabetes. Chung et al. reported that, after adjusted confounding factors, there were still significant positive relationships between bilirubin level and fasting, post-prandial and δ C-peptide level. Even though non-diabetic men were enrolled, our result was in line with their finding. Since bilirubin is a strong antioxidant, our study might support that TB played a protective role for β-cell27.

In the present study, it is interesting to note that both GOT was the 2nd and GPT was the 6th most important variables in the equation. This result indicated that GOT and GPT plays different and independent roles of ISEC. From Fig. 7, it could be noted that there is a negative relationship between GOT and HOMA-β, which tapers down once level of GOT was greater than 50 U/. As for GPT, even though the relationship between GPT and HOMA-β was less tight, there was always a positive correlation in any level of GPT which was different from GOT (Fig. 8). Liver function has long been shown to be related to ISEC. For example, Bonnet et al. demonstrated that liver enzymes are associated with ISEC by using oral glucose tolerance test to quantify ISEC. In 1,309 participants, increased GPT was associated with higher ISEC. They hypothesized that this was due to the decreased endogenous insulin clearance and hepatic insulin extraction15. As for the reason why GOT and GPT were independently related to HOMA-β is also of interest. Even though both are known to be “liver enzyme”, there are still uniqueness between each other. The main source of GPT is solely from liver, in the same time, GOT could be found in other muscle and related to pancreatitis. They are different in nature from this prospective28. Our result was the first one to explore this relationship.

It is interesting to note that many studies confirmed the fact that BF is positively correlated to ISEC29,30. In our study, the importance of BF was the 3rd one and from Fig. 6, it could be noted that if the BF was less than 29.7%, there was no influence for HOMA-β. However, once the BF was between 29.7 and 31.3%, there was a positive effect which means that if the BF was higher the HOMA-β would be better. But this beneficial influence disappeared and a sharp deterioration HOMA-β was noted when the BF was higher than 31.3%. This finding should be totally naïve which could be understood as that mild to moderate obese might have good impact on ISEC. But severe obesity was related to poorer ISEC. The results of the present study be explained by that the BF are related to every variables aforementioned, either positively and negative18,29,31. Thus, our result showed that, after adjusting all these factors, the “net” relationship between BF and HOMA-β still remained positive when BF was less than 31.3%, but in severe obesity, losing of β-cell function is expected.

Both SBP and DBP were all included in the equation (the 4th and 5th important factors). Similar to GOP and GPT, our results indicated that they were independent factors to affect ISEC. For SBP, the decrease of HOMA-β started when it was higher than 120 mmHg (Fig. 4). On the other hand, the role of DBP was simpler. When DBP was less than 80 mmHg, there was no effects on HOMA-β. But when it was higher than 80 mmHg, there was a positive impact of the DBP on HOMA-β (Fig. 5). In other word, the higher the DBP, the better the ISEC. Our findings were quite interesting. First of all, SBP stands for the highest arterial pressure during the contraction of the heart. SBP is the main force to develop oxygen and nutrition to the organs and it would increase with aging due to the stiffness of blood vessels32. On the other hand, DBP was the lowest BP between two heart beats. The physiological roles of DBP were to maintain adequate blood flow to the tissues. However, these facts could not explain why SBP and DBP had different and independent influences on the ISEC? SBP is well-known to be correlated with insulin resistance, particularly in subjects without diabetes33. The other possibility was that higher SBP could increase blood flow to the β-cell34. Xia et al. demonstrated that, in 615 type 2 diabetes, they also concluded that higher DBP might increase blood flow to pancreas and improve β-cell function34. At present, the roles of SBP and DBP still remain unknown and further studies are needed to elucidate this enigma.

It is interesting to note that LDH was the 7th important variables in our equation. Our result showed that if the LDH was higher than 93 U/L, there was a negative influence of ISEC (Fig. 10). LDH has an important role in insulin secretion. In short, higher LDH could interfere insulin secretion35. Our finding was in line with the major understanding of the role of LDH.

An important strength of our study is the use of an independent test set, which allowed us to evaluate model generalizability beyond the training cohort. The inclusion of a calibration assessment further demonstrated that the MARS model retained meaningful agreement between predicted and observed HOMA-β values, even though some underestimation occurred at higher values. This strengthens confidence in the practical applicability of the model, as calibration has been increasingly recognized as essential for clinical implementation.

Compared to traditional multiple linear regression, our MARS approach consistently yielded smaller estimation errors (RMSE and MAE), indicating superior predictive capacity. This finding highlights the advantage of flexible, spline-based methods in capturing nonlinear relationships between biochemical markers and β-cell function, which are often missed by linear models. The improved performance provides further support for adopting modern machine-learning tools in metabolic research.

Another strength lies in the reproducibility of the modeling framework. By scripting all steps—including preprocessing, imputation, hyperparameter tuning, and validation—our analysis is transparent and can be readily adapted to other cohorts. Moreover, the translation of the final MARS equation into an Excel-compatible tool enhances clinical usability, making the model accessible in everyday practice without specialized software.

Our study has limitations. We fully acknowledge that the cross-sectional nature of our dataset prevents us from making causal inferences about the relationship between risk factors and HOMA-β. To address this limitation, our team is currently working toward initiating a longitudinal follow-up study using the MJ Health cohort, which will allow us to track changes in HOMA-β and related parameters over time. This will help us validate the predictive power of the proposed MARS equation in a dynamic, real-world setting.

Additionally, our current study enrolled only healthy Taiwanese men, which may limit the generalizability of our findings. To mitigate this, we are planning to extend our modeling framework to include female participants in future analyses. This broader inclusion will help test the robustness and transferability of the MARS-based equation across different demographic backgrounds.

Another limitation of this study is the absence of external validation. The current model was developed and evaluated using data solely from healthy Taiwanese men, which may limit its generalizability to other populations. However, our primary aim was to establish a proof-of-concept using MARS to estimate HOMA-β based on routinely collected variables. Given the consistent internal performance metrics and the biological plausibility of the selected predictors, we believe the model provides a solid foundation for future work. Ongoing efforts are underway to apply this equation to external cohorts—including female participants and individuals of different ethnic backgrounds—to assess its broader applicability and predictive robustness.

Finally, the use of a relatively modest sample size (n = 317) could affect model stability. To address this, we employed multiple rounds of cross-validation and robust model evaluation metrics to reduce overfitting and improve reliability. In future work, we aim to increase the sample size by pooling data from additional waves of the MJ cohort and other publicly available datasets.

Conclusion

By using MARS, we built an equation which could accurately estimate HOMA-β with a r2 equaled to 0.71 in healthy Taiwanese men without taking any medications related to metabolic syndrome. The most important factor was TB, GOT, BF, SBP, DBP, GPT and LDH. This equation has a practical clinical use and could further explore which were the factors that were related to ISEC.

Data availability

The data supporting this study’s findings are obtained from the MJ Health Research Foundation. However, due to access restrictions, these data are not publicly available as they were used under authorization for this study. Nevertheless, they can be requested from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and with approval from the MJ Health Research Foundation.

References

Fazeli, P. K., Lee, H. & Steinhauser, M. L. Aging is a powerful risk factor for type 2 diabetes mellitus independent of body mass index. Gerontology 66 (2), 209–210 (2020).

Obesity and Overweight. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (2025).

International Diabetes Federation. Taiwan Country Report. https://diabetesatlas.org/data/en/country/194/tw.html (2019).

Chang, C. J., Lu, F. H., Yang, Y. C., Wu, J. S., Wu, T. J., Chen, M. S., Tai, T.Y. Epidemiologic study of type 2 diabetes in Taiwan. Diabetes Res. Clin. Prac., 50, S49-S59. (2000).

Global Increase in Diabetes Prevalence Imposes a Substantial Health and Economic Burden. JHEOR. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight. (2022).

UKPDS Group. Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). Lancet 352 (9131), 837–853 (1998).

The Top 10 Causes of Death. World Health Organization. (2024)., August 7 https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death

Savage, D. B., Petersen, K. F. & Shulman, G. I. Disordered lipid metabolism and the pathogenesis of insulin resistance. Physiol. Rev. 89 (2), 507–520 (2009).

Aguayo-Mazzucato, C. Functional changes in beta cells during ageing and senescence. Diabetologia 63, 2022–2029 (2020).

Matthews, D. R. et al. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia 28, 412–419 (1985).

Kautzky-Willer, A. et al. Increased insulin sensitivity and secretion in women: A possible explanation for differences in diabetes incidence? Diabetologia 38 (5), 586–592 (1995).

Ward, G. M., Nevill, A. M., Williams, C. & Jones, D. A. The hyperglycemic clamp technique: applications in diabetes research. Metabolism 50 (11), 1239–1244 (2001).

Kjems, L. L., Volund, A., Madsbad, S. & Bergman, R. N. Calculation of insulin sensitivity and beta-cell function from the intravenous glucose tolerance test in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 25 (4), 1390–1401 (2002).

Stern, M. P., Williams, K., Gonzalez-Villalpando, C., Hunt, K. J. & Haffner, S. M. Does the metabolic syndrome improve identification of individuals at risk of type 2 diabetes and/or cardiovascular disease? Diabetes Care. 28 (8), 2280–2284 (2005).

Bonnet, F., Disse, E., Oriol, F., Kearney-Schwartz, A., Ducros, V., Blond, E., Drouin,P. Liver enzymes are associated with insulin secretion in nondiabetic men and women. Diabetes Care, 34(3), 714–720. (2011).

Lim, E. L. et al. Reversal of type 2 diabetes: normalisation of beta cell function in association with decreased pancreas and liver triacylglycerol. Diabetologia 54 (10), 2506–2514 (2011).

Kröger, H. & Leopold, L. Education differences in women’s body weight trajectories: the role of motherhood. PLOS ONE, 15(9), e0236487. (2020).

Lo, B. D. et al. Impact of body weight on hemoglobin increments in adult red blood cell transfusion. Transfusion 61 (5), 1412–1423 (2021).

Türkoğlu, B. & Karabacak, A. Koyunlarda Doğum Ağırlığına Etki Eden Bazı Faktörlerin regresyon Ağacı Yöntemiyle belirlenmesi. Bahri Dağdaş Hayvancılık Araştırma Dergisi. 11 (2), 103–112 (2022).

Tzou, S. J. et al. Comparison between linear regression and four different machine learning methods in selecting risk factors for osteoporosis in a Chinese female aged cohort. J. Chin. Med. Association. 86 (11), 1028–1036 (2023).

MJ Health Research Foundation. The introduction of MJ health database & MJ Health Research Foundation Technical Report, MJHRF-TR-01. http://www.mjhrf.org/upload/user/files/MJHRF-TR-01%20MJ%20Health%20Database.pdf. (2016).

Kuhn, M. Building predictive models in R using the caret package. J. Stat. Softw. 28, 1–26 (2008).

Friedman, J. H. Multivariate adaptive regression splines. Annals Stat. 19 (1), 1–67 (1991).

Milborrow, S. earth: Multivariate adaptive regression splines. R package version 5.3.1. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=earth (2021).

Kuhn, M. & Vaughan, D. yardstick: Tidy Characterizations of Model Performance. R package version 1.3.0. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=yardstick (2024).

Wilkinson, L. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis by WICKHAM (H, 2011).

Chung, H. S., Kim, H. J. & Park, H. K. Association between bilirubin and C-peptide in Korean type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metabolism J. 38 (2), 104–110 (2014).

MedlinePlus. GOT and GPT (Liver enzyme test). https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/003472.htm (2023).

Walton, C., Godsland, I. F., Proudler, A. J., Felton, C. V. & Wynn, V. Effect of body mass index and fat distribution on insulin sensitivity, secretion, and clearance in Nonobese healthy men. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metabolism. 75 (1), 170–175 (1992).

Gagnon, E., Mitchell, P. L. & Arsenault, B. J. Body fat distribution, fasting insulin levels, and insulin secretion: A bidirectional Mendelian randomization study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metabolism. 108 (6), 1308–1317 (2023).

Robinson, D. & Whitehead, T. P. Effect of body mass and other factors on serum liver enzyme levels in men. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 26 (Pt 5), 393–400 (1989).

Homan, T. D., Bordes, S. J., Cichowski, E. & Physiology, P. P. [Updated 2023 Jul 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482408/ (2025).

Quesada, O., Claggett, B., Rodriguez, F., Cai, J., Moncrieft, A. E., Garcia, K.,Bello, N. A. Associations of insulin resistance with systolic and diastolic blood pressure: a study from the HCHS/SOL. Hypertension, 78(3), 716–725. (2021).

Xia, Y. et al. Higher systolic blood pressure is specifically associated with better islet beta-cell function in T2DM patients with high glycemic level. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 21 (1), 283. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-022-01723-1 (2022).

ALCAZAR, O., Lenzen, S. & TIEDGE, M., & Importance of lactate dehydrogenase for the regulation of glycolytic flux and insulin secretion in insulin-producing cells. Biochem. J. 352 (2), 373–380 (2000).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge all subjects who participated in the study.

Funding

This study was funded by Taoyuan Armed Forces General Hospital, grant number TYAFGH_E_113061.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Interpretation of data, Po-Tsai Yeh; Analysis, Dee Pei; Acquisition, Chih-Hsiang Ma; Investigation, Chih-Hsiang Ma, Dee Pei, and Chung-Chi Yang; Validation, Chih-Hsiang Ma, Chung-Chi Yang, and Ta-Wei Chu; Drafted the work– original, Chih-Hsiang Ma; Drafted the work – review & editing, Yao-Jen Liang.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by Institutional Review Board of the Tri-Service General Hospital (IRB No.: IRB No.: A202405007 and date of approval 8 May 2024). Since there were no sample collection from the patients, a short review of the Institutional Review Board was approved and no consent form was needed.

Informed consent statement

Not applicable. Analysis was based on secondary data sourced from MJ Health Research Foundation.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, CH., Yeh, PT., Yang, CC. et al. Estimating homeostasis model assessment for insulin secretion by using multiple adaptive regression spline in healthy Taiwanese men. Sci Rep 15, 40179 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23959-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23959-z