Abstract

This study evaluates the accuracy and reliability of six large language models (LLMs)—three Chinese (Doubao, Kimi, DeepSeek) and three international (ChatGPT-4o, Gemini 2.0 Pro, Grok3)—in radiology, using simulated questions from the 2025 Chinese Radiology Attending Physician Qualification Examination (CRAPQE). Analysis covered 400 CRAPQE-simulated questions, spanning various formats (A1, A2–A4, B, C-type) and modalities (text-only, image-based). Expert radiologists scored responses against official answer keys. Performance comparisons within and between Chinese and international LLM groups assessed overall, unit-specific, question-type-specific, and modality-specific accuracy. All LLMs passed the CRAPQE simulation, showing proficiency comparable to a radiology attending. Chinese LLMs achieved a higher mean accuracy (87.2%) than international LLMs (80.4%, P < 0.05), excelling in text-only and A1-type questions (P < 0.05). DeepSeek (91.6%) and Doubao (89.5%) outperformed Kimi (80.5%, P < 0.0167), while international LLMs showed no significant differences (P > 0.05). All models surpassed the passing threshold on image-based questions but performed worse than on text questions, with no group difference (P > 0.05). This pioneering comparison highlights the potential of LLMs in radiology, with Chinese models outperforming their international counterparts, likely due to localized training, providing evidence to guide the development of medical AI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, breakthroughs in artificial intelligence (AI) technologies, particularly large language models (LLMs), have revolutionized the information acquisition and processing paradigm in natural language processing, sparking widespread interest in their potential applications within medicine. As exemplified by ChatGPT and Gemini, general-purpose LLMs have demonstrated exceptional capabilities across critical tasks, including text generation, knowledge-based question answering, and language translation1,2. Specifically, GPT-4o, developed by OpenAI, represents an advanced Transformer-based large language model that leverages vast natural language datasets to learn linguistic rules and patterns, enabling the generation of high-quality responses tailored to specific inputs3. Similarly, Gemini 2.0 Pro, introduced by Google DeepMind, is renowned for its robust multimodal input capabilities, effectively processing diverse data types such as text and images, offering enhanced flexibility and accuracy in addressing complex problems4. Additionally, Grok3, released by xAI—an AI company founded by Elon Musk—has garnered significant attention for its superior reasoning abilities, deep search functionalities, and agent-like intelligence5. The exploration of these cutting-edge LLMs in medical applications has gained considerable momentum, with expectations that they will enhance learning efficiency and optimize knowledge acquisition in scenarios such as clinical decision support, medical literature interpretation, electronic health record generation, and medical education6,7.

Parallel to the advancements in international mainstream LLMs, Chinese LLMs have also experienced rapid development in recent years, giving rise to a series of domestically developed models with distinctive strengths. For instance, DeepSeek, developed by the DeepSeek team, excels in reasoning and multimodal processing for Chinese-language tasks8. Doubao, launched by ByteDance, is distinguished by its robust Chinese language comprehension and generation capabilities, achieving leading performance across multiple Chinese-language benchmarks9. Meanwhile, Kimi, developed by the Moonshot AI team, specializes in long-text processing and complex question-answering10. Although these Chinese models demonstrate remarkable language understanding and generation abilities within Chinese contexts, their performance in highly specialized medical scenarios—particularly in terms of accuracy, stability, and multimodal processing—remains underexplored, lacking systematic and comprehensive evaluations.

In the realm of medical education, the application of LLMs has emerged as a focal point of contemporary research. Existing studies have demonstrated the practical utility of LLMs, such as ChatGPT, in examinations and training across various medical subspecialties, including dentistry11, neurosurgery12, and orthopedics13. Compared to traditional pedagogical approaches, LLMs provide systematic foundational knowledge, integrate clinical experience, evidence-based medical insights, and the latest research findings, and construct a multidimensional knowledge support framework. Through real-time question answering, scenario simulation, and adaptive feedback, LLMs offer medical students and clinicians a more interactive and personalized learning experience, significantly enhancing learning efficiency and clinical reasoning skills14,15.

However, radiology, as a highly specialized medical discipline characterized by the tight integration of textual and visual information, poses unique challenges to AI models due to the complexity of its knowledge system, demanding advanced capabilities in language comprehension, domain-specific expertise, and image processing16,17,18. While preliminary studies have explored the potential of LLMs in medical question answering and clinical reasoning, a significant gap remains in multidimensional and systematic evaluations of their capabilities in the specific radiology domain, particularly concerning image-based questions, multimodal task processing, and the comprehension of specialized question types.

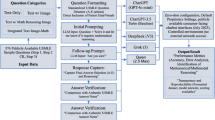

To address this gap, the present study aims to systematically evaluate the performance of mainstream Chinese and international LLMs in radiology using simulated test questions from the 2025 Chinese Radiology Attending Physician Qualification Examination (CRAPQE) in China as a standardized benchmark. This examination, a critical milestone in the professional development of Chinese physicians, represents the competency standards required for intermediate technical positions, providing a reliable and authoritative framework for evaluation due to its rigor and professionalism. The study includes three Chinese LLMs (Doubao, Kimi, DeepSeek) and three international mainstream LLMs (ChatGPT-4o, Gemini 2.0 Pro, Grok3). The evaluation focuses on two key dimensions: first, analyzing the performance differences among Chinese LLMs and international LLMs in terms of overall accuracy, performance across different sections, and performance on various question types (including text-based and image-based questions); second, comparing the average accuracy of Chinese LLMs with that of international LLMs. This study is the first to systematically compare mainstream Chinese and international LLMs in a real-world medical examination setting using the high-standard CRAPQE framework. Furthermore, this study comprehensively assesses the models’ capabilities in handling multimodal medical tasks by incorporating text- and image-based questions. The findings of this study are expected to provide critical empirical evidence to guide the application of LLMs in medical education, intelligent tutoring, and clinical decision support while offering valuable insights for the optimization and evaluation strategies of future medical AI systems.

Materials and methods

Examination dataset

This study utilized simulated test questions from the 2025 CRAPQE as a standardized testing dataset. The simulated examination paper was meticulously designed by authoritative institutions and expert panels, adhering to the official examination syllabus, question types, and difficulty standards, to comprehensively evaluate the professional knowledge and practical competencies of radiology physicians. The examination paper consisted of four main sections: Unit 1 (Basic Knowledge), Unit 2 (Related Professional Knowledge), Unit 3 (Specialized Knowledge), and Unit 4 (Professional Practical Skills). Each section comprised 100 multiple-choice questions, totaling 400 questions. According to the scoring criteria of the Chinese Attending Physician Qualification Examination, each question was worth 1 point, and candidates were required to achieve a score of at least 60 points in each section to pass the examination.

Regarding question types, the dataset encompassed a variety of standard formats in the CRAPQE, including:

-

A1-type questions: Single-sentence best-choice questions.

-

A2-4-type questions: Case summary best-choice questions, with A2-type being single-stem questions and A3-4-type being shared-stem questions.

-

B-type questions: Single-choice questions with shared answer options.

-

C-type questions: Case analysis multiple-choice questions (allowing multiple correct answers).

Furthermore, all questions were explicitly categorized into two major types: purely text-based questions (335 questions) and image recognition and analysis questions (65 questions), to facilitate the evaluation of multimodal capabilities. To provide readers with a better understanding of the question format and difficulty, representative examples (paraphrased to respect copyright) are provided in Table 1.

To establish the significance of this dataset as a benchmark, it is important to understand the context of the CRAPQE. The CRAPQE is a core component of China’s health professional technical qualification examination system, designed to comprehensively evaluate physicians’ professional theoretical knowledge and clinical practice competencies within radiology. The examination content is extensive, covering foundational knowledge (e.g., principles of X-ray, CT, MRI imaging, interventional radiology, medical contrast agents, and sectional anatomy), related professional knowledge (involving the cross-application of imaging technology and pathophysiology), specialized knowledge (focusing on imaging diagnosis of various systemic diseases such as nervous system, chest, bone and joint), and professional practice capability (assessing clinical problem-solving through case analysis, emphasizing the close integration of imaging and clinical aspects). With tens of thousands of annual candidates, the examination typically maintains an overall pass rate of only 30%. This low pass rate underscores the CRAPQE’s exceptionally high professional threshold and stringent assessment standards, positioning it as a mandatory pathway for radiologists to advance to intermediate professional titles, directly influencing their remuneration and scope of practice. Therefore, the rigor of this examination not only ensures that radiologists possess standardized competencies in imaging diagnosis, interventional therapy, and equipment application but also plays a critical role in enhancing the quality of clinical services and safeguarding patient safety, consequently establishing it as a highly challenging and representative benchmark for evaluating LLMs’ medical professional aptitude.

Large language model selection and configuration

A total of six mainstream LLMs were selected for evaluation in this study, comprising three internationally leading and three Chinese domestic models. All models were tested using their latest stable versions available during the experimental period:

International models

-

ChatGPT-4o (OpenAI, version: latest-20250129).

-

Gemini 2.0 Pro (Google DeepMind, version: exp-02–05).

-

Grok3 (xAI, version: preview-02–24).

Chinese models

-

Doubao (ByteDance, version: 1.5pro).

-

Kimi (Moonshot AI, version: 1.5).

-

DeepSeek (DeepSeek, version: R1).

Access to all LLMs was established via their official online chat interfaces or Application Programming Interface endpoints. To simulate typical user interaction and ensure a standardized basis for comparison, the default settings for all models, as provided by their respective developers, were employed. Parameters such as Temperature, Top-p, and Max Tokens were not manually adjusted, as these options were either unavailable through the public-facing interfaces or were maintained at their default, optimized values to reflect intended real-world performance. Furthermore, to preclude the possibility of models retrieving answers from the internet, network connectivity was turned off for all models during testing. This measure guaranteed that all responses were generated exclusively from the models’ internal training data. It is noteworthy that during the evaluation, both the Grok-3 and DeepSeek models explicitly indicated an inability to process image inputs. Consequently, these two models were excluded from the assessment of image recognition and analysis tasks, and their performance on image-based queries was not recorded.

Testing protocol

Standardized input prompts and testing procedures were established for all LLMs to ensure consistency and reproducibility. Each model was tested independently to eliminate potential biases arising from inter-model interactions.

Initial Context Prompt: At the beginning of each test session, the following initial prompt was provided to the LLMs to define their role and task: “You are a radiology physician preparing for the Qualification Examination for Attending Physicians in Radiation Medicine. The examination consists of multiple-choice questions. Below, I will provide the questions individually, and you must select the correct answer(s).”

Question input

To simulate a real-world application scenario within the Chinese medical context, all questions and prompts were presented to all LLMs in their original Simplified Chinese format.

-

Text Component: The full-text content (including the question stem and all answer options) was copied and pasted into the model’s dialogue interface for each question.

-

Image Component: For image recognition and analysis questions, relevant medical images (e.g., X-rays, CT scans, MRIs) were uploaded as attachments in PNG format.

Question-type-specific prompts

To guide the models in generating clear and format-appropriate responses, the following prompts were appended based on the question type.

-

Single-Choice Questions (A1, A2-4, B-type): “This is a single-choice question. Please select the most correct answer.”

-

Multiple-Choice Questions (C-type): “This is a multiple-choice question. Please select all correct answers.”

These prompts were designed to explicitly inform the models of the required answer format and guide their decision-making process for single-choice versus multiple-choice questions.

Evaluation metrics and methods

An attending radiologist with 8 years of clinical experience independently reviewed each response generated by the LLMs. The model’s answers were compared against the official answers, with responses that fully matched the official answers receiving 1 point, and those that did not receiving 0 points. As the evaluation is based on direct comparison with definitive answers, the process is objective, and a single expert is deemed sufficient to ensure the accuracy of the scoring. Accuracy was the percentage of correctly answered questions relative to the total number of questions or the number of questions within a specific category.

The LLMs were divided into two groups: Chinese LLMs (Doubao, Kimi, DeepSeek) and international LLMs (ChatGPT-4o, Gemini 2.0 Pro, Grok3). Performance comparisons were conducted within each group (intra-group comparisons) and between the two groups (inter-group comparisons). The evaluation dimensions included:

-

Overall Accuracy: Assessing the models’ performance across all questions.

-

Section-Specific Accuracy: Analyzing the models’ accuracy across the four examination sections (Units 1–4).

-

Question-Type-Specific Accuracy: Evaluating the models’ performance on different question types (A1, A2-4, B, C).

-

Text vs. Image Question Accuracy: Calculate the models’ accuracy separately for text-based and image recognition and analysis questions.

Statistical analysis

Data collection and preliminary processing were performed using Microsoft Excel 16 (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA). Accuracy and scoring rates were expressed as percentages. All charts and graphs were generated using Microsoft Excel 16 to enhance the clarity and readability of the results.

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 23 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The chi-square test was employed to compare categorical data (e.g., proportions of correct answers) across different LLMs, examination sections, and question types. The statistical significance level was set at P < 0.05. Bonferroni correction was applied to all pairwise comparisons to control for multiple comparison errors, adjusting the significance threshold to P < 0.0167.

Results

Among the six LLMs evaluated, ChatGPT-4o, Gemini 2.0 Pro, Doubao, and Kimi successfully responded to all 400 simulated questions from the Qualification Examination for Attending Physicians in Radiation Medicine. However, Grok3 and DeepSeek, due to their inability to process the 65 image recognition-related questions, were evaluated solely on the remaining 335 text-based questions.

Performance of international LLMs

The overall accuracy rates of the international LLMs were as follows: ChatGPT-4o achieved 79.3%, Gemini 2.0 Pro achieved 81.5%, and Grok3 achieved 80.3%. Chi-square (χ²) tests revealed no statistically significant differences in overall accuracy among these three models (P > 0.05). Table 2; Figs. 1, 2 and 3 provide detailed accuracy rates for these three non-Chinese LLMs across different examination sections, question types, and text-based versus image-based questions. Intra-group pairwise comparisons across these subcategories showed no statistically significant differences (P > 0.05), indicating consistent performance across all evaluated dimensions among the international LLMs.

Performance of Chinese LLMs

The overall accuracy rates of the Chinese LLMs exhibited significant variation: Doubao achieved 89.5%, Kimi achieved 80.5%, and DeepSeek achieved the highest accuracy at 91.6%. Chi-square tests confirmed statistically significant differences in overall accuracy among these three models (P < 0.05). Further intra-group pairwise comparisons, adjusted using the Bonferroni correction, demonstrated that the overall accuracy of both Doubao and DeepSeek was significantly higher than that of Kimi’s (P < 0.0167).

Table 3; Figs. 1, 2 and 3 present detailed accuracy rates for the three Chinese LLMs across different examination sections, question types, and text-based versus image-based questions. In intra-group pairwise comparisons across examination sections, both Doubao and DeepSeek outperformed Kimi significantly in Units 2 and 3 (P < 0.05), while no significant differences were observed between Doubao and DeepSeek (P > 0.05). Regarding question types, intra-group pairwise comparisons revealed that Doubao and DeepSeek achieved significantly higher accuracy than Kimi on A1-type and B-type questions (P < 0.05), with no significant differences observed between Doubao and DeepSeek (P > 0.05). Notably, in comparisons of accuracy on text-based versus image-based questions, no statistically significant differences were found among the Chinese LLMs (P > 0.05), suggesting comparable capabilities in handling questions of different modalities (Figs. 1 and 2).

Comparative analysis of Chinese vs. International LLMs

As shown in Table 4; Figs. 1, 2 and 3, the overall mean accuracy of the Chinese LLMs was 87.2%, significantly higher than that of the international LLMs, which averaged 80.4% (χ² test, P < 0.05). Although the accuracy of the Chinese LLMs was higher than that of the international LLMs in each examination section, these section-specific differences did not reach statistical significance (P > 0.05).

Regarding question modalities, the Chinese LLMs achieved a mean accuracy of 88.8% on text-based questions, significantly surpassing that of international LLMs (P < 0.05). However, on image-based questions, the mean accuracy of the Chinese LLMs (72.3%) was only marginally higher than that of the international LLMs (70%), with no statistically significant difference observed (P > 0.05). Further performance analysis across question types revealed that the Chinese LLMs significantly outperformed the international LLMs on A1-type questions (P < 0.05). In contrast, no statistically significant differences were observed between the two groups on A2–A4-type, B-type, or C-type questions (P > 0.05).

Comparison of the performance of the LLMs for different units of the CRAPQE simulation questions. The bar graph illustrates the accuracy of the six LLMs in answering various units of questions in the CRAPQE simulation questions. LLMs, Large Language Models; CRAPQE, Chinese Radiology Attending Physician Qualification Examination.

Comparison of the performance of LLMs for different question types in the CRAPQE simulation questions. The bar graph illustrates the accuracy of the six LLMs in responding to various types of questions in the CRAPQE simulation. LLMs, Large Language Models; CRAPQE, Chinese Radiology Attending Physician Qualification Examination.

Discussion

This study systematically compared the performance of LLMs developed in the Chinese linguistic environment (Doubao, Kimi, and DeepSeek) and international LLMs (ChatGPT-4o, Gemini 2.0 Pro, Grok3) on simulated questions from the CRAPQE. Our investigation primarily focused on assessing the accuracy and reliability of LLMs in answering radiology-specific questions. Encouragingly, all tested LLMs demonstrated proficiency to pass the examination, indicating their attainment of the professional proficiency required of a radiology attending physician. Specifically, Chinese LLMs exhibited substantially higher overall average accuracy, text-only question accuracy, and A1-type question accuracy than international LLMs. Furthermore, within the Chinese LLMs group, both Doubao and DeepSeek substantially outperformed Kimi in terms of overall answer accuracy, as well as accuracy in ‘Related Professional Knowledge’ (Unit 2), ‘Specialized Knowledge’ (Unit 3), ‘Single-statement best-answer multiple-choice questions’ (A1-type), and ‘Common-answer single-choice questions’ (B-type). Crucially, this study marks the inaugural cross-comparative evaluation of multiple leading international and indigenous Chinese LLMs in the highly specialized field of radiology, providing significant empirical insights for integrating AI into radiological clinical practice and education.

The CRAPQE is a core component of China’s health professional technical qualification examination system, designed to comprehensively evaluate physicians’ professional theoretical knowledge and clinical practice competencies within radiology. The examination content is extensive, covering foundational knowledge (e.g., principles of X-ray, CT, MRI imaging, interventional radiology, medical contrast agents, and sectional anatomy), related professional knowledge (involving the cross-application of imaging technology and pathophysiology), specialized knowledge (focusing on imaging diagnosis of various systemic diseases such as nervous system, chest, bone and joint), and professional practice capability (assessing clinical problem-solving through case analysis, emphasizing the close integration of imaging and clinical aspects). With tens of thousands of annual candidates, the examination typically maintains an overall pass rate of only 30%. This low pass rate underscores the CRAPQE’s exceptionally high professional threshold and stringent assessment standards, positioning it as a mandatory pathway for radiologists to advance to intermediate professional titles, directly influencing their remuneration and scope of practice. Therefore, the rigor of this examination not only ensures that radiologists possess standardized competencies in imaging diagnosis, interventional therapy, and equipment application but also plays a critical role in enhancing the quality of clinical services and safeguarding patient safety, consequently establishing it as a highly challenging and representative benchmark for evaluating LLMs’ medical professional aptitude.

The finding that Chinese LLMs demonstrated substantially higher overall accuracy than international LLMs in this study differs from previous research. For example, a study comparing GPT-4o and DeepSeek-R1 on the Polish infectious disease specialty examination found that both DeepSeek-R1 (73.85%) and GPT-4o (71.43%) were capable of passing the exam (accuracy above 60%). However, there was no statistical difference in their accuracy19. The observed discrepancy may stem from several interacting factors. Firstly, the language of the input questions likely plays a pivotal role. While previous attempts to translate Chinese physician licensing examination questions into English for ChatGPT did not yield substantial accuracy improvements20, another study reported a 5% accuracy increase when questions were professionally translated, suggesting that the quality of translation can profoundly influence outcomes21. As our experiment was conducted entirely in Chinese, the superior performance of Chinese LLMs is likely a synergistic effect of both linguistic proficiency and domain-specific knowledge. On one hand, Chinese LLMs possess a native advantage in processing the nuances of Chinese medical terminology, syntax, and question structures commonly found in domestic examinations. On the other hand, their training curricula likely integrate extensive localized data relevant to the Chinese healthcare system, including China-specific clinical guidelines, epidemiological data, medical education paradigms, and regulatory frameworks, conferring an inherent knowledge advantage. International LLMs, primarily trained on English-centric medical databases, may lack comprehensive coverage of this localized context22. Our study design does not allow for a definitive separation of these two effects, which would require a separate experiment with professionally translated questions. However, it highlights the critical importance of localized training data for high-stakes, region-specific applications.

This study further elucidated that LLMs consistently achieved higher average accuracy on purely textual questions than on image recognition questions. Intriguingly, no statistically significant difference was observed between the Chinese and international LLM groups for image recognition questions. This disparity suggests that textual question performance depends more on a model’s linguistic comprehension and the cultural depth of its training data. In contrast, image questions primarily challenge its visual understanding and multimodal fusion capabilities7,23. Nakaura et al. (2024) evaluated models such as GPT-4o, Claude 3 Opus, and Gemini 1.5 Pro on the Japanese Board of Diagnostic Radiology examination (covering both text and image questions), finding that despite exhibiting some answering capability, none of these models reached the 60% passing threshold24. Furthermore, the introduction of image information did not substantially improve overall accuracy across models, underscoring the prevalent limitations of LLMs in medical image processing during that period24. Conversely, our study reveals that while the performance of Chinese and international LLMs on image questions still lags behind that on text questions, their accuracy rates have surpassed the 60% passing benchmark. This signifies a substantial improvement in the current LLMs’ medical image recognition capabilities, attributable to the continuous evolution of model architectures and advancements in multimodal processing. Regarding individual model performance, Doubao demonstrated higher accuracy than Kimi on image recognition questions within the Chinese LLM group, while ChatGPT-4o outperformed Gemini 2.0 Pro among international LLMs. This further hints at a potential advantage for these models in image comprehension tasks. Concurrently, a previous study evaluating GPT-4 V and Gemini Pro’s image recognition abilities using Japanese National Dental Examination questions, despite showing no statistically substantial difference, reported a slight edge for GPT-4 V over Gemini, which resonates with ChatGPT-4o’s observed relative advantage in image-based questions in our study23.

In summary, despite notable advancements in LLMs’ image-processing capabilities compared to their predecessors, their overall performance on image-based questions lags behind their performance on textual questions. This persistent gap underscores the current limitations of LLMs in specialized image analysis, particularly within medical imaging interpretation. Future research should prioritize enhancing models’ visual feature extraction capabilities and strengthening image-text semantic linkage mechanisms to facilitate higher levels of clinical assistance and truly integrated multimodal understanding.

Concerning specific question typologies, a study assessing the answer rate differences of eight LLMs (Gemini 1.5, Gemini 2, ChatGPT-4o, ChatGPT-4, ChatGPT-o1, Copilot, Claude 3.5, DeepSeek) on oral pathology multiple-choice questions found that ChatGPT-o1 achieved the highest overall accuracy among all models, and for knowledge-based questions, both ChatGPT-o1 and DeepSeek demonstrated higher accuracy25. In the present study, Chinese LLMs demonstrated substantially higher accuracy on A1-type questions (single-statement best-answer multiple-choice questions, primarily focused on foundational knowledge) compared to international LLMs. This likely reflects the superior ability of Chinese models in knowledge recall, pattern matching, and efficient knowledge retrieval within the Chinese linguistic context, particularly for fundamental radiological concepts. Furthermore, our results showed no statistically significant difference in accuracy between international and Chinese LLMs on case-summary best-answer multiple-choice questions (A2-A4 type) and case-analysis questions (C-type). This may suggest that international LLMs are comparable to Chinese LLMs in simulating clinical reasoning for case analysis questions.

This study also revealed internal performance discrepancies among Chinese LLMs. The overall accuracy of Doubao (89.5%) and DeepSeek (91.6%) was substantially higher than that of Kimi (80.5%). This advantage could be attributed to the larger model scale and parameter count of the former two, conferring a more decisive advantage in professional reasoning. While Kimi performs competently in general Chinese Q&A, its design objectives may be more inclined towards daily conversational and lighter tasks, potentially leading to less depth in specialized knowledge coverage compared to Doubao and DeepSeek. Marcaccini et al. tested ChatGPT-4o, Claude, and Kimi’s ability to analyze burn images and generate clinical descriptions and management plans, finding that ChatGPT-4o performed best in image recognition descriptions, comparable to expert plastic surgeons. At the same time, Kimi received relatively lower scores, although all three performed similarly in management plan generation26. In the current study, DeepSeek and Doubao demonstrated stronger logical reasoning and semantic analysis capabilities when handling A1 and B-type questions, suggesting higher adaptability to single-choice and common-answer question formats. Although Kimi’s accuracy on these two question types (above 75.6%) surpassed the passing threshold (60%), it was substantially lower than that of other LLMs, indicating that its reasoning capabilities on specific question types still require further optimization. In Unit 2 (Related Professional Knowledge) and Unit 3 (Specialized Knowledge), Doubao and DeepSeek’s accuracy was substantially higher than Kimi’s, further confirming the former two’s comprehensive mastery of imaging-related knowledge, possibly due to broader data coverage or stronger knowledge retrieval mechanisms. Notably, Doubao and DeepSeek showed no statistically substantial differences across all comparison dimensions (including overall accuracy, different units, and different question types). This likely reflects a convergence in their performance, suggesting that they may have adopted similar medical data and learning strategies during training, leading to similar optimization levels in task performance. Additionally, the difficulty of the examination tasks in this study may not have been sufficient to differentiate the upper limits of their capabilities.

Previous research has focused mainly on the performance of different ChatGPT versions across various specialized medical examinations27,28,29. Our prior study has already demonstrated that, compared to GPT-4 and GPT-3.5, GPT-4o exhibited superior overall accuracy, complex problem-solving abilities, and multi-unit assessment performance in the Chinese National Medical Licensing Examination29. However, that preliminary study did not conduct a cross-model comparison of GPT-4o with other commercially available LLMs to comprehensively delineate the strengths and performance differences among various models. Sau et al. evaluated the answer accuracy of GPT-4o and Gemini on an image-based question bank for the neurosurgery board examination, reporting that GPT-4o’s overall accuracy was 51.45%, substantially outperforming Gemini (39.58%)30. In contrast, in the present study, the three international LLMs—ChatGPT-4o (79.3%), Gemini 2.0 Pro (81.5%), and Grok3 (80.3%)—all demonstrated high accuracy in the CRAPQE simulated examination. However, their overall accuracy and accuracy differences across different units and question types were not statistically substantial. This could be attributed to these international LLMs utilizing similar global general medical data during training, such as publicly available medical literature, textbooks, clinical guidelines, and online medical resources. Such data may exhibit high consistency in the breadth and depth of medical knowledge, resulting in convergence in their medical knowledge coverage. Furthermore, they likely employ similar Transformer-based deep learning model architectures that confer comparable reasoning and language generation capabilities for natural language tasks, resulting in minimal performance differences in examination tasks.

Limitations

First, the development of large language models is progressing at an exceptionally rapid pace, and the results presented in this paper reflect the state of the technology as of March 2025. A related challenge is the potential temporal bias arising from the differing knowledge cutoff dates of the models. The 2025 CRAPQE simulation questions are designed to reflect the latest medical knowledge and clinical guidelines. Some of this information may have been released after the training data cutoff for certain LLMs, which could place them at a disadvantage. The inherent asynchrony between the testing materials and the models’ knowledge is a key factor to consider when interpreting the results. Meanwhile, the performance of these models is likely to be further improved and enhanced in the future. For instance, during the testing period of this study, Grok3 and DeepSeek lacked image recognition and analysis capabilities. Thus, only text-only questions were administered to these two models. This limitation might have influenced the comparability of overall accuracy. However, recognizing the study’s objective to conduct a cross-sectional comparison of model performance at a specific time, we did not undertake supplementary testing with newer versions to maintain consistency in experimental design. Second, the exclusive reliance on simulated questions from the 2025 CRAPQE limits the external generalizability of our findings. Future research should consider incorporating a more diversified range of medical examination datasets to enhance the broad applicability of model evaluations. Third, this study primarily utilized accuracy as the core evaluation metric and did not delve into the logical reasoning pathways or specific error typologies during model responses. Future endeavors should continue to explore a broader testing scope, more comprehensive evaluation metrics, and optimized model designs to advance the deeper application of LLMs in the medical domain.

Conclusion

LLMs demonstrate substantial potential in comprehending and applying radiological knowledge. Chinese LLMs exhibited outstanding performance within the Chinese testing environment, likely correlating with integrating more localized medical content in their training data. While international LLMs exhibited slightly lower overall accuracy than their Chinese counterparts, they still demonstrated strong adaptability in cross-linguistic and cross-cultural contexts. These significant findings not only furnish invaluable empirical evidence for applying LLMs in medical education, examination assistance, and clinical decision support but also offer critical data support for model developers and medical educators. Future research should further explore a broader testing scope, more comprehensive evaluation metrics, and optimized model designs to continuously propel the profound application and development of LLMs in the medical field.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Liu, J., Wang, C. & Liu, S. Utility of ChatGPT in clinical practice. J. Med. Internet Res. 25, e48568. https://doi.org/10.2196/48568 (2023). Published 2023 Jun 28.

Chen, Y. Q. et al. Application of large Language models in Drug-Induced osteotoxicity prediction. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 65 (7), 3370–3379. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jcim.5c00275 (2025).

Varghese, J., Chapiro, J. & ChatGPT The transformative influence of generative AI on science and healthcare. J. Hepatol. 80 (6), 977–980. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2023.07.028 (2024).

Roos, J., Martin, R. & Kaczmarczyk, R. Evaluating Bard Gemini Pro and GPT-4 Vision Against Student Performance in Medical Visual Question Answering: Comparative Case Study [published correction appears in JMIR Form Res. ;9:e71664. doi: 10.2196/71664.]. JMIR Form Res. 2024;8:e57592. Published 2024 Dec 17. (2025). https://doi.org/10.2196/57592

Jiao, C. et al. Diagnostic performance of publicly available large Language models in corneal diseases: A comparison with human specialists. Diagnostics (Basel). 15 (10), 1221. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15101221 (2025). Published 2025 May 13.

Shen, Y. et al. Multimodal large Language models in radiology: principles, applications, and potential. Abdom. Radiol. (NY). 50 (6), 2745–2757. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00261-024-04708-8 (2025).

Liu, M. et al. Evaluating the effectiveness of advanced large Language models in medical knowledge: A comparative study using Japanese National medical examination. Int. J. Med. Inf. 193, 105673. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2024.105673 (2025).

Sandmann, S. et al. Benchmark evaluation of deepseek large Language models in clinical decision-making. Nat. Med. Published Online April. 23 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-025-03727-2 (2025).

Xiong, Y. T. et al. Evaluating the performance of large Language models (LLMs) in answering and analyzing the Chinese dental licensing examination. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 29 (2), 332–340. https://doi.org/10.1111/eje.13073 (2025).

Ren, Y. et al. Evaluating the performance of large Language models in health education for patients with ankylosing spondylitis/spondyloarthritis: a cross-sectional, single-blind study in China. BMJ Open. 15 (3), e097528. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2024-097528 (2025). Published 2025 Mar 21.

Jaworski, A. et al. GPT-4o vs. Human candidates: performance analysis in the Polish final dentistry examination. Cureus 16 (9), e68813. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.68813 (2024). Published 2024 Sep 6.

Schubert, M. C., Wick, W. & Venkataramani, V. Performance of large Language models on a neurology Board-Style examination [published correction appears in. JAMA Netw. Open. 7 (1), e240194. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.0194 (2024).

Kung, J. E., Marshall, C., Gauthier, C., Gonzalez, T. A. & Jackson, J. B. 3 Evaluating ChatGPT performance on the orthopaedic In-Training examination. JB JS Open. Access. 8 (3). https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.OA.23.00056 (2023). e23.00056. Published 2023 September 8.

Wu, Z., Li, S. & Zhao, X. The application of ChatGPT in medical education: prospects and challenges. Int. J. Surg. 111 (1), 1652–1653. https://doi.org/10.1097/JS9.0000000000001887 (2025). Published 2025 January 1.

Tsang, R. Practical applications of ChatGPT in undergraduate medical education. J. Med. Educ. Curric. Dev. 10, 23821205231178449. https://doi.org/10.1177/23821205231178449 (2023). Published 2023 May 24.

Bradshaw, T. J. et al. Large Language models and large multimodal models in medical imaging: A primer for physicians. J. Nucl. Med. 66 (2), 173–182. https://doi.org/10.2967/jnumed.124.268072 (2025). Published 2025 Feb 3.

Bhayana, R. Chatbots and large Language models in radiology: A practical primer for clinical and research applications. Radiology 310 (1), e232756. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.232756 (2024).

Currie, G. et al. ChatGPT in medical imaging higher education. Radiography (Lond). 29 (4), 792–799. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radi.2023.05.011 (2023).

Błecha, Z. et al. Performance of GPT-4o and DeepSeek-R1 in the Polish infectious diseases specialty exam. Cureus 17 (4), e82870. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.82870 (2025). Published 2025 Apr 23.

Fang, C. et al. How does ChatGPT-4 preform on non-English national medical licensing examination? An evaluation in Chinese language. PLOS Digit Health. ;2(12):e0000397. Published 2023 December 1. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pdig.0000397

Tong, W. et al. Artificial intelligence in global health equity: an evaluation and discussion on the application of ChatGPT, in the Chinese National Medical Licensing Examination. Front Med (Lausanne). ;10:1237432. Published 2023 October 19. (2023). https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2023.1237432

Normile, D. Chinese firm’s large Language model makes a Splash. Science 387 (6731), 238. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adv9836 (2025).

Fukuda, H. et al. Evaluating the image recognition capabilities of GPT-4V and gemini pro in the Japanese National dental examination. J. Dent. Sci. 20 (1), 368–372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jds.2024.06.015 (2025).

Nakaura, T. et al. Performance of multimodal large Language models in Japanese diagnostic radiology board examinations (2021–2023). Acad. Radiol. 32 (5), 2394–2401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acra.2024.10.035 (2025).

Yilmaz, B. E., Gokkurt Yilmaz, B. N. & Ozbey, F. Artificial intelligence performance in answering multiple-choice oral pathology questions: a comparative analysis. BMC Oral Health. 25 (1), 573. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-025-05926-2 (2025). Published 2025 Apr 15.

Marcaccini, G. et al. Management of burns: Multi-Center assessment comparing AI models and experienced plastic surgeons. J. Clin. Med. 14 (9), 3078. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14093078 (2025). Published 2025 Apr 29.

Ali, R. et al. Performance of ChatGPT and GPT-4 on neurosurgery written board examinations. Neurosurgery 93 (6), 1353–1365. https://doi.org/10.1227/neu.0000000000002632 (2023).

Ishida, K., Arisaka, N. & Fujii, K. Analysis of responses of GPT-4 V to the Japanese National clinical engineer licensing examination. J. Med. Syst. 48 (1), 83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-024-02103-w (2024). Published 2024 Sep 11.

Luo, D. et al. Evaluating the performance of GPT-3.5, GPT-4, and GPT-4o in the Chinese National medical licensing examination. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 14119. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98949-2 (2025). Published 2025 Apr 23.

Sau, S. et al. Accuracy and quality of ChatGPT-4o and Google Gemini performance on image-based neurosurgery board questions. Neurosurg Rev. ;48(1):320. Published 2025 Mar 25. (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-025-03472-7

Acknowledgements

All authors read and approved the submitted version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Clinical Key Specialty Construction Project and also supported by Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation general project (ZR2021MH304), the Shandong Traditional Chinese Medicine Science and Technology Project (M-2022081), the Shandong Traditional Chinese Medicine Science and Technology Project (M-2022080), and the Shandong Provincial Medical and Health Plan (2019WS214).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DL and ML wrote the manuscript. ML and DL were responsible for data collection, testing, and recording. ML, HZ, XW, and QG were responsible for data evaluation, statistical analysis, and icon-making. DL, HZ, XW, NK, ZZ, and TY were responsible for reviewing and editing. DL, NK, TY, and ZZ guided the manuscript’s design, revision, and submission.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Conflict of interest

This study received no funding. All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Luo, D., Liu, M., Zhang, H. et al. Comparative performance of Chinese and international large language models on the Chinese radiology attending physician qualification examination. Sci Rep 15, 39379 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23973-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23973-1