Abstract

Accurate identification of urban built-up areas is crucial for monitoring urbanization and promoting sustainable development. To overcome the limitations of single-data-source methods in capturing human activities, this study proposes a novel approach for urban built-up area extraction, based on machine learning techniques, and multi-source data fusion (POI, Luojia-1 nighttime light, and Landsat 8 imagery). First, we construct the POI-Adjusted Luojia-1 Urban Index (PALUI) by combining POI and Luojia-1nighttime light data quantify population distribution patterns. Next, we segment remote sensing indices (NDVI, MNDWI, NDBI) using the triangle threshold algorithm to differentiate vegetation, water, and built-up areas. Finally, a Naive Bayes classifier is used to fuse these features for built-up area extraction. Experiments in Nanchang City show that the proposed method achieves a precision of 0.89 and recall of 0.76, outperforming SVM, Random Forest, U-net, and YOLO11. The PALUI index effectively reduces light overflow issues in nighttime data, while the multi-source fusion strategy improves edge accuracy in complex urban environments. This method offers a reliable solution for high-precision urban mapping.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) emphasize the role of cities as key drivers of economic growth, contributing approximately 60% of global GDP1. Accurate identification of urban built-up areas is therefore essential for urbanization monitoring and sustainable development. However, existing extraction methods often rely on single data sources, which are prone to misclassification in complex urban environments. In recent years, advancements in Earth observation and big data technologies have enabled more sophisticated methods for tracking urbanization. High-resolution remote sensing imagery, nighttime light data, and multi-source datasets are increasingly used to assess urban atmospheric environments, land sustainability and socioeconomic impacts. These approaches play a pivotal role in supporting sustainable urban development.

The automatic identification and extraction of urban built-up areas from high-resolution optical imagery, nighttime light data, and other multi-source datasets have attracted considerable attention in urbanization monitoring, leading to notable progress. Numerous studies have shown that integrating optical, radar, and nighttime light imagery can substantially improve the delineation of built-up areas and support the mapping of complex urban structures2,3,4,5. In particular, the use of high-resolution remote sensing imagery for built-up area extraction has been extensively investigated.

Traditional optical index methods such as NDVI, MNDWI, and NDBI have long been used to delineate urban surfaces6,7,8,9,10. These indices are simple and effective in distinguishing vegetation, water, and impervious surfaces. However, they are limited by spectral confusion in transition zones (e.g., urban–rural fringes), resulting in misclassification and reduced reliability in complex environments11. Recent improvements, such as combining indices with temperature information10 or integrating NDVI with MNDWI and NDBI11, have achieved better performance, yet problems of noise and overlapping spectral signatures persist12.

In addition, nighttime light data has become an essential source for urban built-up area extraction. Early sensors such as DMSP-OLS provided valuable but coarse-resolution insights13,14, while the launch of NPP-VIIRS offered higher radiometric quality15,16,17. However, both suffered from oversaturation and light spillover around bright areas such as airports and roads18,19. To address this, numerous methods were developed, including regression-based calibration15, Sobel and watershed operators14, and multi-source fusion with land cover products13. More recently, the Luojia-1 satellite, with 100–130 m resolution, has provided a significant improvement in monitoring urban structures17,18. Studies have demonstrated its effectiveness in analyzing multi-center urban patterns in the Greater Bay Area17 and reducing blooming effects in complex cityscapes18. Nonetheless, even with Luojia-1, light overflow and resampling errors remain key challenges19.

Crowd-sourced POI (Point of Interest) data have also proven to be a significant resource for urban built-up area extraction. POI data, which captures the descriptive attributes of urban entities, have been widely used to analyze urban built-up areas. Zhou19 and Yu and Ai20 applied kernel density analysis on various POI distribution patterns to identify urban built-up areas, effectively overcoming challenges related to facility point distribution in urban network spaces. These studies also explored the distribution characteristics, image factors, and service functions of POI infrastructure in urban areas. However, due to the limited spatial density of POI data from public sources, it remains challenging to fully capture the spatial distribution characteristics of a city based solely on its spatial location. Liu et al.21 highlighted the high spatial correlation between POI data and nighttime light. By constructing an index relationship for data fusion, they improved the accuracy of urban built-up area extraction22. He et al.23 utilized wavelet transformation to describe urban boundaries and interconnections between cities, using nightlight data, POI, and Tencent migration data to precisely delineate urban boundaries. Additionally, Li et al.24 proposed a comprehensive index combining nighttime light data and POI to assess the accuracy of urban built-up area information. This method enhanced the extraction process by accounting for the connectivity of urban structures, offering a more thorough analysis of urban built-up areas.

Machine learning methods such as Support Vector Machines (SVM) and Random Forest (RF) have also been widely applied in built-up area extraction. These algorithms can handle high-dimensional features and have achieved solid performance in urban classification tasks12,16,26. For example, SVM has been used to integrate multisource data including DMSP-OLS, Landsat, and GlobeLand3012, while RF has been shown effective in handling Sentinel-2 imagery and complex urban infrastructure22. Despite their robustness, these methods often require careful parameter tuning and may face challenges when dealing with heterogeneous and highly imbalanced urban datasets25.

Deep learning approaches such as CNN, U-Net, and their variants have recently achieved remarkable success in building and impervious surface extraction6,7,8,9,25,26,27. Transfer learning with Sentinel-26, improved U-Net architectures7,8, and emerging Transformer-based models25,27 have all delivered high accuracies in urban mapping. However, these approaches require large annotated datasets and substantial computational resources, which constrain their scalability for regional or national studies. Moreover, the “black-box” nature of deep networks limits their interpretability, which is critical for applications in land management and policy support4,26.

In summary, previous studies have made notable progress using optical indices6,7,8,9,10,11,12, NTL data13,14,15,16,17,18,19, POI datasets19,20,21,22,23,24, and deep learning methods6,7,8,9,25,26,27. Yet, the integration of these heterogeneous data sources remains a central challenge, particularly in cities with complex land cover and diverse socioeconomic activity.

To address these challenges, this study proposes a multi-source fusion method that combines Landsat 8-derived indices (NDVI, MNDWI, NDBI), Luojia-1 nighttime light data, and POI datasets. A new POI-Adjusted Luojia-1 Urban Index (PALUI) is constructed to mitigate light spillover and better represent population-driven urban morphology. Furthermore, the Naive Bayes classifier is employed for its computational efficiency, robustness to heterogeneous features, and interpretability, offering a lightweight alternative to resource-intensive deep learning models7,8,26. This design balances accuracy and efficiency, making the approach suitable for large-scale urban monitoring and practical applications in land management.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the study area and datasets. Section 3 presents the methodology, including the construction of the PALUI index, the triangle threshold segmentation, and the Naive Bayes classifier. Section 4 reports and discusses the experimental results. Finally, Sect. 5 concludes the study with a summary of key findings, broader implications, and directions for future research.

Materials

Study area

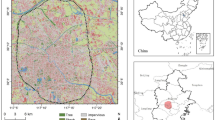

Nanchang, the capital of Jiangxi Province, is a key city in the urban agglomeration along the middle reaches of the Yangtze River and serves as a central hub of the Yangtze River Economic Belt. The city consists of six districts and three counties. With rapid development, Nanchang is accelerating the construction of rail transit and expressway networks, which has led to significant expansion in its built-up area. According to the Nanchang Government, the city’s urbanization rate is projected to reach 78.92% by 2022. Therefore, accurate and effective extraction of Nanchang’s land use data is crucial for the city’s development in urban culture, economy, and transportation. The study area for this research is Nanchang City, as shown in Fig. 1.

Dataset

The data used in this study include Nanchang’s administrative boundaries, Landsat 8 imagery, POI data, and CLCD, as shown in Table 1. All data are open-source and acquired from public platforms, with access URLs provided in Table 1. Landsat 8 is equipped with two sensors: the Operational Land Imager (OLI) and the Thermal Infrared Sensor (TIRS). The OLI provides global land image coverage with a spatial resolution of 30 m in the visible, near-infrared, and short-infrared bands, while the TIRS offers a spatial resolution of 100 m for the thermal infrared band and a 15 m for the panchromatic band. POI data represent urban entities as geolocated spatial points, each containing location and attribute information that describe various functional areas within the city. In this study, we used 178,090 POI data points generated in Nanchang City in July 2022, obtained via the AutoNavi API interface.

Luojia-01 is a satellite that captures nighttime light brightness values with a spatial resolution of 130 m. To account for temporary light sources, such as firelight and lake reflections, three sets of scene data were selected for radiation calibration, atmospheric correction, and mean synthesis to ensure reliability. These data were resampled to a 30 m spatial resolution for further processing. CLCD28 is land cover data published by Wuhan University, with a spatial resolution of 30 m, covering land cover information from 1990 to 2022.

Methods

The flowchart of the methodology used in this paper is shown in Fig. 2, which consists of five main steps: datasets preparation, index construction, threshold segmentation, model training, and classification prediction. Data preprocessing is performed using Google Earth Engine (GEE) to streamline the process. As shown in Fig. 2, the NDVI, MNDWI, and NDBI remote sensing indices are constructed, along with the POI and nighttime light data to generate the POI-Adjusted Luojia-1 Urban Index (PALUI), which is used to describe the population distribution in urban built-up areas. The triangle threshold algorithm is then applied to segment the constructed remote sensing indices, enabling the identification of various ground object distributions. Finally, the SVM, Random Forest, and Naive Bayes classifiers are employed for classification prediction.

Remote sensing index calculation

Calculation of NDVI, NDVI and NDBI index

To extract the built-up areas, the surface target index was calculated for analysis. Based on the spectral characteristics of vegetation, water bodies, buildings, and other features in the study area, the following indices were used: the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI)29, the Modified Normalized Difference Water Index (MNDWI)30, and the Normalized Difference Built-up Index (NDBI)31. The formulas for these indices are as follows:

NDVI could react with plant coverage and growth conditions, MNDWI aims to extract urban water body information, and NDBI could react with built-up area. The above formula represents the near-infrared band, \({\rho _{Red}}\)represents the infrared band, \({\rho _{Green}}\)represents the green band, \({\rho _{MIR}}\)represents the mid-infrared band and \({\rho _{SWIR}}\) represents the shortwave infrared band.

PLUI index calculation

Relying solely on spectral indices such as NDVI, MNDWI, and NDBI for urban built-up area extraction fails to account for the influence of population distribution. In contrast, Point of Interest (POI) data, accessible through Location-Based Services (LBS) platforms like AutoNavi, provide direct insights into human activity patterns by mapping the density and diversity of urban facilities. Studies have shown that POI spatial aggregation strongly correlates with population distribution32,33, enabling the identification of built-up areas beyond spectral signatures. In parallel, nighttime light (NTL) data serves as an additional and independent source of information on anthropogenic intensity and spatial extent. NTL observations capture urban activity patterns in regions where structural boundaries are indistinct34,35. Compared to spectral indices, NTL data are less affected by atmospheric conditions and provide stable, continuous coverage across large spatial extents36,37. By integrating POI and NTL data, the robustness and reliability of urban built-up area delineation can be substantially improved. The complementary nature of POI and NTL allows for a more comprehensive representation of urbanization processes, overcoming the limitations of single data source and enabling more accurate identification of built-up areas across diverse and complex built-up areas.

To establish the connection between POI points and Luojia-01 data, this paper constructs the PALUI index. The calculation formula for the PALUI index is as follows:

Here, \(D{N_i}\) represents the pixel value of the Luojia-01 nighttime light data for the i-th pixel, and the \(PO{I_i}\) represents the POI kernel density value of the i-th pixel. The PALUI index indicates the index value constructed from the relationship between POI kernel density and Luojia-01 nighttime light data.

The kernel density estimation (KDE) is a spatial density analysis method that calculates the spatial smoothness of univariate sample point groups, the kernel density estimation method is described as follows38.

Suppose \(x_{1}\)、 \(x_{2}\)…\(x_{n}\) are sample values, \(p\left( x \right)\) is the density value at a certain point, expressed as shown in Eq. (4).

Here, \(K\left( x \right)\) is called kernel function, in this paper, the \(K\left( x \right)\) is expressed as shown in Eq. (5).

In Eq. (5), N is the number of samples, \({x - x_{k}}\) represents the distance between the estimation point x and the sample point \({x_k}\), h is called bandwidth, and it is a smoothing parameter.

For accuracy comparison, in the proposed method, we resample the Luojia-01 nighttime light data to the 30 m spatial resolution.

Triangular threshold algorithm

The triangular threshold algorithms are commonly used for image processing and segmentation39. It divides an image into two regions: foreground and background. The objective is to find an optimal threshold that effectively separates these two regions. The basic concept of the triangular threshold algorithm involves plotting the pixel gray values in a histogram and drawing a straight line across the histogram to form a triangle40, as shown in Fig. 3. The peak of the triangle represents the point (maxid, max), and the rightmost point of the line is (255, 0). The equation from the peak point to the line L on the right can be expressed by\(Ax+By+C=0\). The distance from the corresponding point in the curve to the line L is:

The above formula\(\left( {{x_0},{y_0}} \right)\) represents the coordinates of the midpoint of the curve. When the d value is the largest, it is the best threshold.

The triangular threshold method demonstrates high efficiency in handling bimodal image distributions, particularly under conditions of low noise and pronounced contrast between foreground and background, enabling rapid and accurate segmentation. In contrast, the Riddler–Calvard and Otsu methods are generally more suitable for complex backgrounds and gray-level distributions, but they involve higher computational complexity and exhibit greater sensitivity to noise1. Previous studies have shown that the histograms of NDVI and MNDWI in experimental regions often display clear bimodal characteristics2,3, which facilitate the straightforward separation of vegetation from non-vegetation areas and water bodies from non-water bodies. Consequently, these indices are well-suited to the triangular threshold approach. By comparison, the NDBI emphasizes the extraction of urbanized areas using red and shortwave infrared (SWIR) bands4. However, the spectral contrast among urban areas, buildings, and other land-cover types is generally less distinct than that between water and non-water or vegetation and non-vegetation, and thus NDBI histograms may not exhibit pronounced bimodality, limiting the applicability of the triangular threshold method in such cases.

Naive-Bayes classification model

The Naive-Bayes classification model is based on Bayes’ theorem and the assumption of independent feature conditions. The maximum posterior probability output is obtained after solving using Bayes’ theorem for a given input41. Its specific algorithm flow is as follows:

Given a set of training datasets \(T = \{(x_{1}, y_{1}), (x_{2}, y_{2}),\ldots,(x_{n}, y_{n})\}\), in \(x_{i} = (x_{i}^{{(1)}}, x_{i}^{{(2)}},\ldots, x_{i}^{{(j)}})\), \(x_{i}^{{(j)}}\) is the j feature of the \(i{\text{-}}th\) sample, \({{\text{a}}_{jl}}\) is the l value that the \(j{\text{-}}th\) feature, j = 1,2,…, n; l = 1, 2, …,\(y_{i} \in \{c_{1},c_{2},\ldots, c_{k}\}\); The final output result is the classification of instances x.

(1) Calculate the prior probability and its conditional probability

\({j=1,2,\ldots, n}, {l=1,2,\ldots, S_{j}}, {k=1,2,\ldots, K}\)

(2) For a given instance \(x_{i}=(x_{i}^{(1)}, x_{i}^{(2)},\ldots, x_{i}^{(n)})^{T}\)

(3) Determine the category of x,

In this study, the Naive Bayes classification model was selected as the classifier primarily due to its efficiency and stability in urban remote sensing classification. Previous studies have shown that Naive Bayes classification model can achieve accuracy comparable to SVM in high-resolution object-based image classification1, and in certain urban texture image tasks it even outperforms SVM while offering higher computational efficiency2. Therefore, Naive Bayes classification model provides a balance between accuracy and reduced model complexity, making it a suitable classification method for this study.

Experimental results

Result analysis based on triangle threshold segmentation method

To verify the accuracy of the triangle threshold segmentation algorithm, the Otsu algorithm42 and Riddler-Calvard algorithm42 were used to evaluate the segmentation results of the three indices. The CLCD dataset originally consisted of 9 categories. Taking into account the geographical location, climate conditions, and built-up areas of Nanchang City, these categories were reclassified into three types: water bodies, built-up areas, and forests12,17. The results are shown in Table 2.

The triangle threshold algorithm demonstrates better segmentation results for NDVI and MNDWI values, as shown in Table 2. However, for NDBI values, the segmentation accuracy differs by 0.02 compared to the Riddler-Calvard algorithm. This discrepancy arises from the difficulty of distinguishing built-up areas from non-built-up areas using the NDBI, where the boundaries are often unclear, resulting in lower segmentation accuracy.

Subfigures a, b, and c in Fig. 4 illustrate the segmentation results for NDVI. Compared to the other two algorithms, the triangle threshold algorithm more effectively distinguishes the boundary distribution of forests and buildings in the area marked by the black circle. This indicates that the algorithm performs better in identifying small vegetation patches within urban environments when extracting built-up areas. The segmentation results are more differentiated in areas with significant contrasts between built-up and non-built-up regions.

Subfigures d, e, and f in Fig. 4 show the segmentation results for MNDWI. In the area marked by the black circle, the triangle threshold algorithm provides a more detailed segmentation of water bodies within the city compared to the other two algorithms. It is particularly effective in identifying long, narrow water bodies in urban areas.

Subfigures g, h, and i in Fig. 4 present the segmentation results for NDBI. The Riddler-Calvard algorithm outperforms the triangle threshold algorithm in identifying built-up areas and distinguishing non-built-up regions from the surrounding built-up areas. Compared to the NDVI, the discrimination of built-up and non-built-up areas is less clear in NDBI. This is due to the fact that, as cities evolve into rural areas, the number of buildings decreases and land use transitions from urban to agricultural land. During this transition, the spectral characteristics of ground objects remain relatively unchanged, leading to poor segmentation results when using the triangular threshold algorithm for NDBI.

Evaluation of PALUI index results

The aggregation of POI points can reflect the population distribution in built-up areas, and kernel density analysis is used to measure the aggregation of these points. The results of kernel density analysis vary with different search radio. A larger search radius produces smoother results, making the description of point aggregation more reliable43. The movement range of urban residents is typically centered around residential areas, with a 300 m radius representing the typical range. For urban residents, a 500 m search radius is considered reasonable. As the scope of activities expands and the research area increases, the kernel density search radius should be adjusted accordingly.

In this study, we use a stepwise range from 300 m to 2000 m for kernel density analysis. As the search radius increases, points with higher local kernel density values gradually merge, and the smoothness of the generated contours improves. The kernel density of POI points in the experimental area was analyzed with search radii of 800 m, 1200 m, and 1600 m. The results are shown in Fig. 5.

When the search radius is 600 m (Fig. 5a), the aggregation of points in the city is clearly visible, with detailed descriptions of aggregation in Honggutan District and Qingshan Lake District. However, aggregation in Jinxian County and Anyi County is insufficiently represented. When the search radius is increased to 1200 m (Fig. 5b), the POI points in the core area of Nanchang City become more concentrated, and the results are smoother. Additionally, the urban distribution in Jinxian County and Anyi County is more clearly defined. Further increasing the search radius to 1600 m (Fig. 5c) enhances the smoothness of the core area, allowing for a more accurate representation of POI aggregation in both the core area of Nanchang City and in Jinxian County and Anyi County.

Different kernel density search radii produce different results, but the PALUI index effectively reflects the distribution of people in various regions through kernel density values. In the context of the urban scale of the experimental area, a search radius for 1600 m for kernel density analysis yield optimal results. The results are then normalized for further analysis, as shown in Fig. 5.

Nighttime light data has the advantage of clearly defining urban development boundaries through pixel brightness values. After preprocessing, pixel brightness in the built-up areas of Nanchang City is higher, and the core area is clearly outlined. However, brighter pixel values are also observed at the airport in the northern part of the city. Relying solely on pixel values from nighttime light data makes it difficult to capture the transition between built-up and non-built-up areas. To address this, kernel density analysis is used in combination with nighttime light data to construct the PALUI index for built-up areas.

As shown in Fig. 5d, by constructing and normalizing the PALUI index to mitigate the influence of stronger light sources, sporadic light sources around roads are effectively removed. The boundary of the city is now more clearly defined. The index values in the core areas of Honggutan District, Qingshan Lake District, East Lake District, West Lake District, and Qingyun Pu District are close to 1, indicating a high concentration of built-up areas.

Analysis of built-up area extraction results based on the Naive-Bayes classification model

To assess the classification accuracy of the Naive-Bayes model, we introduce precision, recall, and F1-score as evaluation metrics44. The calculation formulas are as follows:

In formula (12) and (13), TP represents the correctly predicted positive examples, FP represents the incorrectly predicted positive examples, and FN represents the incorrectly predicted negative examples. At the same time, we also adopted the Kappa coefficient, the Kappa coefficient (k) is used to measure the agreement between classification results and reference data, defined as:

where p0 represents the observed agreement, calculated as the ratio of the sum of diagonal elements in the confusion matrix to the total number of samples, and pe denotes the expected agreement by chance, obtained from the product of row and column marginals of the confusion matrix. A higher k value indicates stronger agreement beyond chance, with k = 1 representing perfect concordance and k = 0 reflecting purely random consistency.

The constructed remote sensing indices are then fed into the Naive Bayes41, SVM12, Random Forest26, U-Net9, and YOLO V1145 models. These models are trained using remote sensing indices, and the results are shown in Table 3.

As shown in Table 3, the Naive Bayes classifier achieved strong performance in classifying non-built-up areas (F1 = 0.86) and built-up areas (F1 = 0.82), with slightly lower accuracy in water body detection (F1 = 0.80). Importantly, it also obtained the highest Kappa coefficient (0.82), indicating the strongest overall agreement with the reference data. Random Forest presented relatively balanced performance across all categories, with F1 scores ranging from 0.75 to 0.84 and a Kappa value of 0.77. SVM attained the highest precision for non-built-up areas (0.92) but with lower recall (0.75), whereas the opposite pattern was observed for built-up areas; its Kappa coefficient (0.78) further confirms its stable but not optimal performance. The U-Net model excelled in water body recognition (F1 = 0.96), and the lowest Kappa value (0.73). YOLOv11 exhibited comparatively weaker performance, with F1 scores below 0.74 for all categories, but its overall agreement was moderate (Kappa = 0.75).Compared to other models, YOLOv11 tends to misclassify complex scenes into a single category under such conditions, which reflects its relatively limited adaptability in semantic segmentation tasks. This limitation may stem from its network architecture, which is primarily optimized for bounding box regression rather than fine-grained modeling of pixel-level semantic information45. As a result, the model demonstrates reduced capability in accurately delineating complex object boundaries in high-variability geospatial contexts.

In Fig. 6, the red areas represent built-up areas, the blue areas represent water bodies, and the yellow areas represent non-built-up areas.

In Sample 1, the red-circled region corresponds to an inner-city water body. The Naive Bayes classifier delineates the water body in a manner that is broadly consistent with the reference satellite image, suggesting a relatively robust ability to separate water features from built-up areas. By contrast, both the U-Net and YOLOv11 models misclassify portions of the surrounding area as built-up regions, indicating a tendency for these deep learning methods to overgeneralize non-water areas in heterogeneous urban–water boundaries. This highlights the challenge of accurately distinguishing mixed pixels and transitional zones between aquatic and urban environments.

In Sample 2, the red-circled region highlights a park area containing both water bodies and vegetation. The SVM and Random Forest classifiers exhibit noticeable errors in delineating the surrounding built-up areas, where portions of vegetation and bare soil are misclassified as built-up areas. In contrast, the Naive Bayes classifier and the U-Net model generate results that are more consistent with the reference imagery, demonstrating a comparatively higher capacity to preserve the spatial integrity of non-built-up classes adjacent to urban features. This difference suggests that traditional machine learning methods are more prone to pixel confusion in heterogeneous urban–green space interfaces, whereas Naive Bayes and deep learning models achieve relatively better discrimination.

In Sample 3, the red-circled region corresponds to an urban park. Compared with the other classifiers, the Naive Bayes method more accurately delineates the built-up areas surrounding the park while retaining a clearer boundary between built-up areas and green spaces. This enables a more detailed depiction of the park’s spatial extent within the urban fabric, highlighting the ability of Naive Bayes to reduce pixel confusion at the interface between vegetation and built-up areas.

In Sample 4, the Naive Bayes classifier again outperforms the other methods in delineating built-up areas and produces more detailed results. Nevertheless, certain misclassifications are observed, including the erroneous labeling of riverbanks and river centers as built-up regions. Moreover, tidal flats formed by erosion are frequently misclassified as urban areas, mainly because the pixel signatures of wet mud and exposed sediments closely resemble those of bare land and built-up areas. These findings underscore the persistent challenge of distinguishing hydrologically dynamic landscapes from urban features using pixel-based information alone.

Conclusions

Using POI data, Luojia-01 nighttime light data, and Landsat 8 data, this paper focuses on Nanchang City as a case study. We employ the triangle threshold segmentation, kernel density analysis, PALUI index, and Naive Bayes classifier to identify built-up areas. Additionally, the Random Forest algorithm and SVM were used for verification and comparison. Based on the experiments, the following conclusions were drawn:

-

(1)

The PALUI index effectively describes the distribution of people and built-up areas within the city. By leveraging POI and nighttime light data, our method offers a more accurate representation of population and built-up area distribution. The optimal search radius of 1600 m yields the most detailed and precise results, and the use of kernel density analysis to construct the PALUI index improves the clarity of urban boundary delineation, advancing urban segmentation techniques.

-

(2)

The triangular threshold algorithm demonstrates superior segmentation results for NDVI and MNDWI, particularly in identifying internal water bodies and complex urban areas. However, the algorithm’s performance for NDBI segmentation is limited due to the inherent challenges posed by urban evolution. This highlights a gap in existing methods, which our approach addresses by incorporating additional data sources.

-

(3)

In classifying ground objects, the Naive Bayes classifier outperforms traditional methods such as SVM and Random Forest, achieving an F1 score of 0.82 for built-up areas. The U-Net model excels in identifying water bodies, with an F1 score of 0.96. YOLOV11’s F1 score for water body recognition is 0.74. YOLOV11 model has the advantage of target detection rather than semantic segmentation, so its effect is not very good compared with Unet models. While the core urban area is accurately identified, challenges remain, such as the misidentification of tidal flats as built-up areas. This highlights an opportunity for further improvement in classification accuracy, an area where our method offers potential for refinement.

Although this study has made some progress in urban built-up area extraction, there are still challenges. Due to data limitations, this study selected only a single region as the experimental area. A dense distribution of water systems characterizes the chosen region and represents a typical waterfront city. Therefore, future research should consider incorporating diverse types of urban regions (e.g., mountainous cities, plain cities, and waterfront cities) further to validate the generalizability and applicability of the proposed method. In addition, the spatial resolution of the nighttime light data used in this study was enhanced through resampling, which may inevitably result in a certain degree of accuracy loss. To improve the reliability of the results and the robustness of the method validation, future work will employ nighttime light data with higher spatial resolution (e.g., SDGSAT-1) for further testing. Moreover, future studies will focus on improving classification accuracy, particularly in complex regions, by incorporating long-term temporal series, leveraging higher-resolution remote sensing data, and integrating advanced deep learning techniques to optimize the feature extraction process.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Guo, H., Chen, F., Sun, Z., Liu, J. & Liang, D. Big Earth data: A practice of sustainability science to achieve the sustainable development goals. Sci. Bull. 66 (11), 1050–1053 (2021).

Wei, D. et al. Extraction and Spatiotemporal analysis of impervious surfaces in Chongqing based on enhanced DeepLabv3+. Sci. Rep. 15, 1234 (2025).

Li, J., Wang, Z., Zhang, Y., Xu, T. & Chen, Q. A method for extracting buildings from remote sensing images based on an improved UNet3 + model. Sci. Rep. 14, 4567 (2024).

Sun, Y., Xu, J., Lin, L., Qiu, Y. & Ma, Q. CG-CFPANet: multisource data fusion for Built-up area extraction using SDGSAT-1 and optical imagery. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 127, 103732 (2024).

Zhang, L., Han, Y., Wang, X., Ma, J. & Shi, Y. Real-complex feature fusion for built-up area extraction from PolSAR data. Remote Sens. Lett. 15 (3), 227–236 (2024).

Bramhe, V. S., Ghosh, S. K. & Garg, P. K. Extraction of built-up areas using convolutional neural networks and transfer learning from sentinel-2 satellite images. Int. Archives Photogrammetry Remote Sens. Spat. Inform. Sci. 42, 79–85 (2018).

Li, W. et al. Deep learning-based classification methods for remote sensing images in urban built-up areas. Ieee Access. 7, 36274–36284 (2019).

Wu, F. et al. Built-up area mapping in China from GF-3 SAR imagery based on the framework of deep learning. Remote Sens. Environ. 262, 112515 (2021).

Zhang, J., Zhang, X., Tan, X. & Yuan, X. Extraction of urban built-up area based on deep learning and multi-sources data fusion—The application of an emerging technology in urban planning. Land 11 (8), 1212 (2022a).

Bhatti, S. S. & Tripathi, N. K. Built-up area extraction using Landsat 8 OLI imagery. GIScience Remote Sens. 51 (4), 445–467 (2014).

Zheng, Y., Tang, L. & Wang, H. An improved approach for monitoring urban built-up areas by combining NPP-VIIRS nighttime light, NDVI, NDWI, and NDBI. J. Clean. Prod. 328, 129488 (2021).

Ma, X. et al. Optimized sample selection in SVM classification by combining with DMSP-OLS, Landsat NDVI and GlobeLand30 products for extracting urban built-up areas. Remote Sens. 9 (3), 236 (2017).

Ma, X., Li, C., Tong, X. & Liu, S. A new fusion approach for extracting urban built-up areas from multisource remotely sensed data. Remote Sens. 11 (21), 2516 (2019).

Yu, B. et al. Urban built-up area extraction from log-transformed NPP-VIIRS nighttime light composite data. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 15 (8), 1279–1283 (2018).

Sun, L., Han, Y., Xie, Z. & Li, R. Neighborhood extremum method of extracting urban built-up area using nighttime lighting data. Geomatics Inform. Sci. Wuhan Univ. 45 (10), 1619–1625 (2020).

Liang, Z., Huang, J., Wei, F., Shen, J. & Li, S. Identifying the Spatial range of urban agglomerations in China based on night light remote sensing and POI data. Geogr. Res. 39 (1), 92–102 (2020).

Zhi, Q., Chen, J., Fu, Y. & Guo, B. The Multi-Center Spatial Structure in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area Urban Agglomeration Based on Luojia1-01 Nighttime Light Data and POI Data. Trop. Geogr., 42(3), 444–456 (2022).

Tang, X., Tang, J., Li, W., Ggao, X. & Song, S. Extraction of Built-up area based on Luojia 1–01 combined with multi source data. Remote Sens. Inform. 38, 78–87 (2023).

Zhou, N. Research on urban Spatial structure based on the dual constraints of geographic environment and POI big data. J. King Saud University-Science. 34 (3), 101887 (2022).

Ai, T. & Yu. W., & The visualization and analysis of POI features under network space supported by kernel density Estimation. Acta Geodaetica Cartogr. Sin. 44 (1), 82 (2015).

Liu, J. et al. Urban nighttime leisure space mapping with nighttime light images and POI data. Remote Sens. 12 (3), 541 (2020).

Zhang, J., Zhang, X., Tan, X. & Yuan, X. A new approach to monitoring urban built-up areas in Kunming and Yuxi from 2012 to 2021: promoting healthy urban development and efficient governance. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 19 (19), 12198 (2022b).

He, X. et al. Delineation of urban agglomeration boundary based on multisource big data fusion—A case study of Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao greater Bay area (GBA). Remote Sens. 13 (9), 1801 (2021).

Li, F., Yan, Q., Zou, Y. & Liu, B. Extraction accuracy of urban built-up area based on nighttime light data and POI: A case study of Luojia 1–01 and NPP/VIIRS nighttime light images. Geomatics Inform. Sci. Wuhan Univ. 46 (6), 825–835 (2021).

Jin, X., Xu, H., Liu, L., Wang, Y. & Zhao, F. High-resolution Building extraction based on multiple attention mechanisms. Front. Earth Sci. 11, 1202512 (2023).

Wang, Y., Lin, S., Li, F. & Xu, L. Automated built-up infrastructure extraction using Sentinel-2 imagery and random forest models. Remote Sens. 15 (12), 3021 (2023).

Liu, M., Guo, X., Zhang, P., Zhao, D. & LMSwin_PNet A Swin Transformer-based local enhancement network for Building extraction. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 62, 1–12 (2024).

Yang, J. & Huang, X. 30 m annual land cover and its dynamics in China from 1990 to 2019. Earth System Science Data Discussions, 1–29 (2021). (2021).

Rouse, J. W. Jr, Haas, R. H., Deering, D. W., Schell, J. A. & Harlan, J. C. Monitoring the vernal advancement and retrogradation (green wave effect) of natural vegetation (No. E75-10354) (1974).

Xu, H. A study on information extraction of water body with the modified normalized difference water index (MNDWI). J. Remote Sensing-Beijing. 9 (5), 589–595 (2005).

Zhang, Y., Odeh, I. O. & Han, C. Bi-temporal characterization of land surface temperature in relation to impervious surface area, NDVI and NDBI, using a sub-pixel image analysis. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 11 (4), 256–264 (2009).

Xue, B. et al. Overview of man-land relationship research based on POI data: Theory, method and application. Geogr. Geo-Inf Sci. 35, 51–60 (2019).

Bingchen, Y., Yuxuan, L. & Gang, C. Urban Spatial structure of Port City in South China sea based on Spatial coupling between nighttime light data and POI. J. Geo-Information Sci. 20 (6), 854–861 (2018).

Elvidge, C. D. et al. Relation between satellite observed visible-near infrared emissions, population, and energy consumption. Int. J. Remote Sens. 18 (6), 1373–1379 (1997).

Li, F., Yan, Q., Bian, Z., Liu, B. & Wu, Z. A POI and LST adjusted NTL urban index for urban built-up area extraction. Sensors 20 (10), 2918 (2020).

Yao, Y., Chen, D., Chen, L., Wang, H. & Guan, Q. A time series of urban extent in China using DSMP/OLS nighttime light data. PLoS One. 13 (5), e0198189 (2018).

Yu, B. L. et al. Nighttime light remote sensing and urban studies: Data, methods, applications, and prospects. Natl. Remote Sens. Bull. 25 (1), 342–364 (2021).

Silverman, B. W. Density Estimation for Statistics and Data Analysis (Routledge, 2018).

Kittler, J. & Illingworth, J. Minimum error thresholding. Pattern Recogn. 19 (1), 41–47 (1986).

Gonzalez, R. C. Digital image processing. Pearson education india (2009).

Lee, P. Bayesian Statistics: an Introduction 1st edn (Wiley, 2012).

Daponte, J. et al. Comparison of thresholding techniques on nanoparticle images. In visual information processing XVI. SPIE 6575, 149–158 (2007, April).

Thurstain-Goodwin, M. & Unwin, D. Defining and delineating the central areas of towns for statistical monitoring using continuous surface representations. Trans. GIS. 4 (4), 305–317 (2000).

Goutte, C. & Gaussier, E. A probabilistic interpretation of precision, recall and F-score, with implication for evaluation. In European conference on information retrieval (pp. 345–359). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg (2005), March.

Diwan, T., Anirudh, G. & Tembhurne, J. V. Object detection using YOLO: Challenges, architectural successors, datasets and applications. Multimedia Tools Appl. 82 (6), 9243–9275 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments on the manuscript, which helped improve the quality of the paper.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.42161064, 42104030), Jiangxi Provincial Natural Science Foundation(20232ACB204032, 20242BAB20129), Ganpo Talent Support Program-Key Disciplinary Academic and Technical Leader Development Project (20243BCE51111), Science and Technology Innovation Project of the Department of Natural Resources of Jiangxi Province(ZRKJ20242620).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Methodology, Bo Liu, Xia Zhong, Yuan Li; Visualization, Ming Liao, Yuefeng Lu; Writing original draft, Bo Liu, Yuan Li, Xia Zhong; Revised the manuscript, Bo Liu, Hua Liu, Yuan Li, Xia Zhong; All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Y., Zhong, X., Liu, H. et al. Urban built-up area extraction using triangle threshold algorithm and Naive Bayes classification model with multidata fusion. Sci Rep 15, 40175 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23986-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23986-w