Abstract

Thought problems and attention problems are common in childhood and are important for later-emerging psychological disorders, yet less is known about the early childhood predictors underpinning such problems. We examined whether early childhood theory of mind (ToM) and effortful control (EC) constitute predictors for preadolescent thought and attention problems. We longitudinally tracked 214 children’s ToM and EC, assessed with behavioral tasks, at ages 3 and 6, along with their thought and attention problems at ages 6 and 10, assessed using maternal report. Findings show that poorer ToM at age 6 predicted more severe development of thought problems emerging between ages 6 and 10, and poorer EC at age 6 predicted more attention problems at age 10. These findings reveal the developmental links between ToM, EC, thought problems, and attention problems, offering implications for developmental-psychopathology accounts and highlighting the importance of early childhood predictors on developing thought and attention problems’ symptomology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background: theory of mind and effortful control

Two important abilities that show rapid and substantial development during early childhood are theory of mind1,2 and effortful control3. Theory of mind (ToM) refers to the skills to explain and understand self and others in terms of mental states, including hopes, dreams, intentions, beliefs, and desires4,5. Effortful control refers to a general control component of temperament that governs the child’s capacity to inhibit a dominant response (e.g., grabbing a toy from a peer) and initiate a subdominant response (e.g., asking for a turn to play with the toy). The emergence of ToM and EC in early childhood profoundly influences our later daily lives, social interactions, and mental well-being, including significant impacts on children’s friendships and popularity, engagement in lying and deception, strategies for persuading or arguing with others, skills for regulating emotions, and transition to school6,7.

From a developmental psychopathology perspective, difficulties in ToM and EC contribute to the development and maintenance of mental health problems. For instance, poor ToM has long been found to be one of the most salient developmental markers for autism spectrum disorders (ASD)8,9, and poor EC is associated with a wide range of psychological disorders, including both internalizing and externalizing psychopathology10. Indeed, early difficulties in ToM and EC have long-lasting influences in children’s adjustment, as these factors in early childhood set the stage for subsequent development of various mental health outcomes, consistent with the concept of developmental cascades11, which argues that functioning or problems in one domain could spread to other domains over time through dynamic developmental processes. Given their importance, the present study examines early childhood ToM, EC, and their longitudinal associations with later-emerging mental health problems during preadolescence, with a particular focus on thought problems and attention problems – Do early childhood ToM and EC constitute early childhood predictors for thought and attention problems, with ToM specifically predicting thought problems and EC specifically predicting attention problems?

Thought problems

Thought problems refer to difficulties and differences in thinking and processing information, often seen in various mental health conditions12,13,14. These can manifest as obsessions and compulsions, where children experience persistent, intrusive thoughts and engage in repetitive behaviors. Children with thought problems also might see or hear things that aren’t present or hold beliefs despite evidence to the contrary. Odd or eccentric thoughts are another aspect, characterized by thinking patterns that deviate significantly from normative ideas, often reflecting bizarre or unrealistic concepts. Confusion and disorientation are also critical, indicating challenges in understanding their environment or situation, leading to bewilderment. Additionally, preoccupation with strange ideas and behaviors is a crucial component, where children may intensely focus on peculiar or unrealistic thoughts, impacting their ability to engage in everyday activities.

For young children, some aspects of thought problems are developmentally appropriate, such as having imaginary friends or creative imaginations. However, severe and consistent thought problems influence daily functioning and are common in psychological disorders such as schizophrenia, obsessive-compulsive disorders (OCD), and ASD. Indeed, the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), one of the most widely used tools in clinical and research settings for early identification and intervention of psychological disorders, includes a thought problems subscale covering these more severe aspects. See Table 1, where we show the fifteen items in the CBCL thought problems subscale. This subscale is crucial for detecting, addressing, and supporting children facing severe levels of thought problems and who are at increased risk of related psychological disorders15,16. It is also our study’s focal measure to reflect children’s thought problems.

It is theoretically plausible to assume a link between ToM and thought problems. For example, early on, Frith (1992) hypothesized a link between ToM and thought problems specifically for patients with schizophrenia17. Theoretically, the idea is that patients have difficulties in correctly representing the relationships between their own mental states, others’ mental states, and reality – they equate their subjective representations with others’ minds and objective reality – so they experience thought problems such as delusions. Such ToM difficulties manifest in patients with ASD as well. They fall short of accurately representing other minds, arguably resulting in strange ideas toward other people and a lack of social reciprocity. Also, ToM difficulties may contribute to pathological reasoning seen in patients with OCD, as their obsessional and compulsive symptoms are well related to their interpretations of their own intrusive thoughts, such as thought-action fusion, and beliefs about thought controllability18. Broadly, incorrectly representing others’ mental states might lie behind the tendencies, across a wide range of psychological disorders, to lose interest in social interaction, have disorganized communications, and insistent incorrect beliefs about self and others. Empirical evidence supports these theoretical links between ToM and thought problems, where many studies and meta-analyses with adult patients with schizophrenia19,20, ASD21,22, and OCD23,24 revealed ToM difficulties in these populations. Given its strong theoretical association with thought problems, early childhood ToM may constitute a predictor for preadolescent thought problems.

Attention problems

Attention problems refer to difficulties in sustaining focus, managing impulses, and maintaining organizational skills. These issues can manifest as distractibility, where a child frequently shifts from one activity to another without completing any, or as impulsivity, characterized by acting without thinking, interrupting others, and struggling to wait their turn. Hyperactivity, another aspect of attention problems, involves excessive movement, fidgeting, and an inability to remain still. Additionally, children with attention problems often have difficulty following through on instructions, keeping track of personal items, and avoiding careless mistakes in their work. These symptoms can severely impact a child’s academic performance, social interactions, and daily functioning25.

Attention problems are commonly linked to several psychological disorders, most notably attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). ADHD is characterized by persistent patterns of inattention and/or hyperactivity-impulsivity that are more severe than typically observed in children at a similar developmental level26. Besides ADHD, attention problems can also be present in other conditions such as learning disabilities, anxiety disorders, and ASD. Given the importance and relevance of attention problems across multiple disorders and adjustment outcomes, the CBCL also includes a dedicated subscale for attention problems, which serves as a valuable tool for identifying and measuring these issues in children. We also use it as the focal measure to reflect children’s attention problems. See Table 1 for the items in the CBCL attention problems subscale.

Evidence linking EC and attention problems is well documented. This is because EC is fundamentally linked to attention management, serving as a pivotal conductor of cognitive processes that dictate focus, concentration, and prioritization in goal-directed behavior. Consequently, individuals with poor EC may experience significant attention problems, as seen in conditions such as ADHD. In fact, numerous neuropsychological evidence of ADHD implicates EC differences as the causal mechanisms for the hyperactivity, impulsivity, and most focally, attention problems in ADHD27. Beyond ADHD, the links between EC and attention problems have also been shown widely in other populations, including preterm children28 and children with depressive symptoms29. These strong associations prove straightforward surface validity between EC and attention problems and lead us to hypothesize that early childhood EC can constitute a predictor for preadolescent attention problems.

Research aims

Despite the plausibility of ToM and EC as early childhood predictors, the developmental links between ToM/EC and thought/attention problems remain less studied and relatively indirect in young children from a nonclinical sample. Existing studies focus more on how ToM and EC are linked to internalizing and externalizing symptoms, and often on clinical samples, such as patients with ASD, OCD, ADHD, or schizophrenia16,30,31. Our primary aim is to empirically establish whether early childhood ToM and EC indeed constitute longitudinal predictors for preadolescent thought and attention problems that may serve as markers for a wide range of psychological disorders. We do so by longitudinally measuring children proceeding from preschool into preadolescence. As hypothesized above, we expect that poorer early ToM skills will predict more severe later thought problems, and that poorer early EC skills will predict more severe later attention problems; In addition, we will explore whether other relationships exist, such as early ToM skills predicting later attention problems and early EC skills predicting later thought problems.

To address this primary research aim, it was essential to first characterize the developmental pathway between ToM and EC in our sample. This constitutes a foundational first step for testing our focal hypothesis that ToM and EC follow distinct pathways to different forms of psychopathology. Importantly, this involves engaging with the central theoretical debate on how these two constructs relate over time: the EC-emergence account versus the EC-expression account of ToM development32. Under the emergence account, EC and ToM scaffold each other and contribute to ToM development by enabling children to construct and update representations of others’ mental states. Under the expression account, EC is required to express already well-formed ToM during task performances (e.g., false-belief tasks) by inhibiting one’s own knowledge of reality and maintaining alternate beliefs. Clarifying which account better describes ToM-EC development is informative because it determines the temporal ordering of ToM and EC, as well as the mechanisms by which early cognition may confer risk for later psychopathology32,33. So far, cross-sectional studies have consistently confirmed concurrent connections between ToM and EC, but fewer have tackled their longitudinal trajectories, and those that have report mixed findings, with some showing early EC predicting later ToM, others showing the reverse.

The present study

We addressed these two interconnected aims via longitudinal design tracking more than 200 children tested as 3-, 6-, and 10-year-olds.

Developmental pathway between ToM and EC

For this aim, we used cross-lagged longitudinal analyses for ages 3 and 6 assessments. This allowed us to find which developmental pathway (e.g., ToM at age 3 → EC at age 6, EC at age 3 → ToM at age 6) characterized these children. The identified trajectory then provided the foundation to test the longitudinal relations between ToM/EC and later thought/attention problems.

Longitudinal relations between early childhood ToM/EC and preadolescent thought/attention problems

To measure thought and attention problems in preadolescence, we used the Child Behavior Checklist 6–18 (CBCL 6–18) at ages 6 and 1034. The CBCL includes several subscales, and we specifically focused on the two directly relevant ones: the thought problems subscale and the attention problems subscale.

Methods

Participants

Children were part of an ongoing longitudinal project investigating early behavioral development35. They were 3 years (M = 3.44, SD = 0.16), 6 years (M = 5.77, SD = 0.31), and 10 years (M = 10.52, SD = 0.52) at three waves of data collection. Of 245 children who participated initially, our 214 participants (99 female) were those with at least one wave of data on our focal variables (i.e., ToM and EC) at ages 3 and 6. Most families (95%) were recruited from newspaper announcements and advertisements sent to daycare centers and preschools, with others referred by pediatricians and teachers.

Table 2 shows key descriptive variables for our sample. Children were largely white (85%). Most parents had college educations (78% for fathers; 83% for mothers). Most mothers reported being married, 5% were single, 4% lived with a partner, and 3% were separated or divorced. Annual family income ranged from $10,000 to $100,000, but with a median between $60,000 and $70,000, most children were from lower-middle and middle-class families. Children evidenced good general intelligence on the Vocabulary (scaled score: M = 11.43; SD = 3.54) and Block Design (The Block Design subtest from the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence–Revised36 requires children to reproduce geometric patterns using two-colored blocks within a specified time limit, assessing visuospatial processing, visual–motor coordination, and nonverbal reasoning). (scaled score: M = 10.55; SD = 3.46) subtests of Wechsler’s Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence-Revised36. Indeed, 95% percent were within or above the age-normed typical range (i.e., above percentile rank of 5). See Olson et al. (2005) for more details of the study sample and procedure35. All methods and protocols in the present study were carried out in accordance with APA ethical guidelines and regulations and have been continuously approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Michigan since 1999. Informed consent was obtained from the parents of all families included in the study. Verbal assent was also obtained from the child participants.

Given the mostly White composition of our sample, plus the high educational attainment of most of our parents, it is important to characterize how our sample relates to more normative ones, including the prevalence (or possible over- or under-representation of mental health symptomatology). We calculated this in terms of general mental health problems using the summary T scores of internalizing and externalizing problems at ages 6 and 10 in the CBCL (see also the Measures section). T scores of 65 and below are considered to be in the normal range (below the 95th percentile); T scores of 65 to 70 are considered to be in the borderline range (the 95th to 98th percentile); T scores of 70 and above are considered to be in the clinical range (above the 98th percentile). In our sample, the mean T scores of internalizing problems were 46.59 (SD = 9.09) and 50.30 (SD = 10.40) at ages 6 and 10, respectively; the mean T scores of externalizing problems were 50.98 (SD = 8.90) and 48.70 (SD = 10.55) at ages 6 and 10, respectively. These two general summary scores help establish that our sample represented a normative population and was not skewed towards a clinical population.

Measures

Theory of mind

At age 3 and age 6, ToM was assessed using false-belief explanation and prediction tasks37, which tap whether children can predict and explain a story protagonist’s belief-driven actions. In brief, the tasks involve an object placed at a location and then moved to another location, and a protagonist who sees the first placement but not the movement to the second location. For the prediction tasks, children predicted where the protagonist would look for the object. Children received a score of 2 if they correctly answered both the control question (i.e., “where is the object really?”) and correctly predicted the protagonist’s search based on the protagonist’s false belief (i.e., the first location). Other responses were scored 0. For the explanation tasks, the protagonist further searched for the object in the first location, and children had to explain that action. Children received a score of 2 if they correctly answered the control question and spontaneously explained the protagonist’s false belief underlying the search (e.g., “because he thinks the object is in there”). Children received a score of 1 if they only provided such an explanation when asked, “what does he/she think?” Other responses were scored 0.

At age 3, children received four prediction and four explanation tasks; at age 6, they received three prediction and three explanation tasks. All tasks had structurally parallel story scenarios and have been used successfully in previous studies38,39,40,41,42. A child’s ToM score was a proportion summing their correct responses and dividing by the total possible correct score. If a child was missing one or more tasks, the score was based on the number of tasks they completed (i.e., correct responses divided by completed tasks). Each child’s ToM score was then standardized by subtracting the sample mean and dividing by the sample’s standard deviation, so the resulting scores represent how far above or below the sample average each child scored. These standardized scores were used in the analyses. Internal consistency reliability was good at both age 3 (alpha= 0.7138; and age 6 (alpha= 0.6839;, indicating that all individual ToM tasks consistently measured the same underlying construct of ToM.

Effortful control

At age 3, a six-task toddler-age behavioral battery was administered to index children’s EC43: turtle-rabbit, tower, delay, whisper, tongue, and lab gift tasks35. At age 6, a parallel early school-age behavioral six-task battery was used44: Simon says, Kansas reflectivity/impulsivity scale, walk a line slowly, green–red signs, shapes, and drawing tasks45. All tasks were administered as game-like, and children were reminded of the rules halfway through each task. Please see Appendix S1 for the details of the 12 tasks and their scoring criteria. Fifteen randomly-selected test administrations were videotaped and independently scored at each age, with excellent inter-rater reliability (age 3: mean kappa = 0.95, range = 0.92–0.98; age 6: mean kappa = 0.93, range = 0.91–0.96.91.96), indicating strong agreement between raters/experimenters when coding the same child’s performance. Acceptable internal consistency reliability was also obtained (age 3: alpha= 0.7035; age 6: alpha= 0.5938, indicating that the individual tasks within the EC battery consistently measured the same underlying construct of EC.

For each specific task, each child’s task score was first standardized by subtracting the sample mean and then dividing by the sample’s standard deviation, so the result represents how far above or below the sample average each child scored on that specific task. Then, for each child, the standardized scores for the six tasks at age 3 were further averaged to create a composite score reflecting their overall EC ability at age 3. Similarly, the standardized scores for the six tasks at age 6 were averaged to reflect their overall EC ability at age 6. If a child was missing one or more tasks, the composite scores reflected the mean of the tasks they completed.

Thought problems and attention problems

At ages 6 and 10, mothers rated their child’s behaviors via the CBCL 6–1834, a widely utilized parent-report measure with well-established normative data, excellent reliability and validity. The CBCL asks adults (mothers in our case) to rate target children using a 3-point response scale, from 0 (not true), 1 (somewhat or sometimes true), to 2 (very true or often true) on 120 behavioral items.

More focally, as already explained, we specifically focused on two subscales – thought problems and attention problems – in the syndrome scales of the CBCL. The thought problems subscale includes 15 items, such as “can’t get his/her mind off certain thoughts” and “hears sound or voices that aren’t there.” The attention problems subscale includes 10 items such as “can’t concentrate, can’t pay attention for long” and “can’t sit still, restless, or hyperactive.” See Table 1 for the items in these two subscales. For both subscales, analyses used raw scores, computed by summing the scores for individual items, and no participants had partial missing data on the items in these subscales.

Because the same measures were administered across ages 6 and 10, we could examine not only the age-10 outcome of thought problems and attention problems in preadolescence (i.e., their prevalence/raw scores at age 10) but also the developmental transition into preadolescence (i.e., the difference between ages 6 and 10).

Ethics approval

All methods and protocols in the present study were carried out in accordance with APA ethical guidelines and regulations and have been continuously approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Michigan since 1999.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from the parents of all families included in the study. Verbal assent was also obtained from the child participants.

Results

Developmental pathway between ToM and EC

In our preliminary analyses, to assess the developmental pathway between ToM and EC, we used structural equation modeling (SEM) to examine the cross-lagged relations between ToM and EC at ages 3 and 6. There are four candidate models to compare (Fig. 1A):

-

(1)

A baseline model of no developmental relationship between ToM and EC.

-

(2)

ToM at age 3 predicts EC at age 6 (ToM → EC).

-

(3)

EC at age 3 predicts ToM at age 6 (EC → ToM).

-

(4)

ToM and EC at age 3 are both predictors (ToM ↔ EC).

Given past findings, we hypothesized a priori that the cross-lagged relationships would be positive (e.g., ToM at age 3 should positively predict EC at age 6). Two less relevant parameters, the concurrent covariations between ToM and EC at age 3 as well as ToM and EC at age 6, were estimated separately and fixed in the cross-lagged models. As expected, ToM and EC at age 3 concurrently correlated (standardized coefficient = 0.106, SE = 0.06, z = 1.75, p =.04). Similarly, ToM and EC at age 6 also correlated (standardized coefficient = 0.143, SE = 0.07, z = 1.96, p =.025).

We used full information maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors and scaled Chi-square test statistics, which handle missing data and nonnormality well. For model comparisons, Akaike information criterion (AIC), sample adjusted Bayesian information criterion (SABIC), and robust Chi-square difference tests were jointly used. AIC and SABIC consider both fit and parsimony, where the smallest values indicate the best model. Robust Chi-square difference tests examine whether having one or more additional pathways improves model fit relative to the baseline model. A significant result (p <.05) means that adding additional pathway(s) is preferred. For good model fit, the scaled Chi-square statistic, comparative fit index (CFI), standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) were used. For best fit, the scaled Chi-square statistic should be non-significant, CFI should exceed 0.95, SRMR should be less than 0.08, and RMSEA should be less than 0.06. All model coefficients reported were first standardized and then tested using one-tailed Z tests. The standardized model coefficient represents the expected change, in standard deviation units, in the outcome variable for a one standard deviation increase in the predictor variable, allowing for easy comparisons across variables with different scales. The z-statistic from one-tailed Z tests is obtained by dividing the standardized coefficient by its standard error, and it indicates how many standard errors the coefficient is from zero, with larger values providing stronger evidence against the null hypothesis. We used one-tailed Z tests because we predicted the directions on all pathways (e.g., positive in this case, as shown in Fig. 1A). We performed model comparisons first to select the best model, and then ensured that the chosen model had good model fit, followed by the interpretations of the coefficients.

The ToM → EC model had the smallest AIC (2180.92, all other models > 2182) and SABIC (2182.69, all others > 2184), along with a marginally significant Chi-square difference test result (p =.06). This model had near perfect fit according to the scaled Chi-square statistic, CFI, SRMR, and RMSEA criteria (see Fig. 1B). Thus, this model outperformed the others and explained the data very well (see Table S1 for a complete tabular comparison of the four candidate models). As clear in Fig. 1B, ToM at age 3 positively predicted ToM at age 6 (standardized coefficient = 0.159, SE = 0.07, z = 2.28, p =.01), and EC at age 3 positively predicted EC at age 6 (standardized coefficient = 0.317, SE = 0.06, z = 4.98, p <.001). Most of all, the developmental relationship between ToM and EC demonstrated that ToM at age 3 positively predicted EC at age 6 (standardized coefficient = 0.133, SE = 0.07, z = 1.87, p =.03). That is, a one standard deviation unit increase in ToM at age 3 led to a 0.133 standard deviation unit increase in EC at age 6.

This model, therefore, became the backbone structure for modeling and analyzing our primary analysis integrating ToM-EC development with thought problems and attention problems in preadolescence.

(A) Conceptual visualizations of the four cross-lagged models linking ToM and EC. Our focus is the single-headed arrows, which indicate the directional relationships between variables. Double-headed arrows indicate concurrent covariation between variables (were estimated and reported separately). + indicates that we expected a positive association. (B) The results of the ToM → EC model, which suggests that ToM at age 3 is a predictor of EC at age 6. The numerical values are standardized path coefficients. *p <.05; ***p <.001.

Longitudinal relationship between early childhood ToM/EC and preadolescent Thoughts/Attention problems

Thought problems

For our focal analyses, first, we examined whether ToM and/or EC could predict thought problems, including, as mentioned earlier, examining both an age-10 outcome measure (raw score at age 10) and a developmental change measure (difference score between ages 6 and 10). Thus, we compared a total of eight models, four candidate models for age-10 outcome and four for development, to characterize and test all the possible relationships via SEM. See Appendix S2, Figure S1, and Table S2 for more details of model building and comparisons.

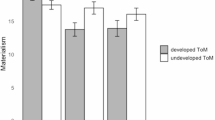

The main results of these analyses are shown in Fig. 2A. The model concerning the developmental change of thought problems between ages 6 and 10 had the best fit, where poorer early childhood ToM (but not poorer EC) was a predictor leading to the increasing development of more severe thought problems from age 6 to 10.

Panel (A) shows the ToM → Thought Problems model, which suggests that only ToM predicts the developmental outcome measure of Thought Problems. Panel (B) shows the results of the EC → Attention Problems model, which suggests that only EC predicts the age-10 outcome of Attention Problems at age 10. The numerical values are the standardized path coefficients. *p <.05.

Attention problems

To examine whether ToM and/or EC could predict attention problems, we implemented the same modeling strategy used for thought problems (for more details, see Appendix S3, Figure S2, and Table S3).

The results of these analyses were straightforward (Fig. 2B): Poorer EC (but not poorer ToM) predicted more severe attention problems. In this case, the model focusing on problems at age 10 (and not the development change between ages 6 and 10) was the best-fit model.

Combined model

Given these findings, we constructed a combined model (Fig. 3A) to summarize our results and again tested it using SEM analyses. The model hypothesizes that the ToM-EC trajectory underlies ToM negatively predicting the development of thought problems between ages 6 and 10, and EC negatively predicting attention problems at age 10. Additionally, the covariation between thought problems and attention problems was also hypothesized because they both concern psychotic symptoms. All these parameters were freely estimated. The SEM procedure and indexes used here followed the same logic as detailed before. Note that because we already identified and confirmed all the effects in the earlier separate models, this final model did not aim to cross-validate those findings (only possible to accomplish with an independent sample). Instead, this combined model simply comprehensively summarizes our results.

Figure 3B shows that this combined model has excellent model fit, with a non-significant chi-square statistic, a perfect CFI, a good SRMR, and near perfect RMSEA. The results echoed that ToM at age 6 negatively predicted the development of thought problems (standardized coefficient = −0.172, SE = 0.08, z = −2.12, p =.02), EC at age 6 negatively predicted attention problems at age 10 (standardized coefficient = −0.17, SE = 0.08, z = −2.16, p =.02), and thought problems development and attention problems at age 10 were positively correlated (standardized coefficient = 0.337, SE = 0.09, z = 3.58, p <.001). Figure 3B further shows all the pathways and the estimated coefficients in the model.

In summary, these results address our primary research aim: demonstrating that, and how, poorer ToM and EC were indeed early predictors of preadolescent thought and attention mental health problems.

The final model with (A) the conceptual visualization with predictions and (B) the results. Single-headed arrows indicate the directional relationships between variables, and double-headed arrows indicate covariation between variables. The numerical values are the standardized path coefficients. *p <.05; ***p <.001.

Discussion

Within developmental psychopathology, identifying early childhood risk mechanisms that impact the development of psychological disorders is a crucial research task. We address this task in the present study by longitudinally tracking children from early childhood to preadolescence and assessing whether ToM and EC were predictors for later thought and attention problems. To be clear, our study was not a confirmatory study based on firm a priori predictions. Instead, it was an exploratory developmental study focused on factors informed mostly by previous findings with adults and clinical samples20,46 and extended such findings to young children in a nonclinical sample to identify developmental links. As theorized in our introduction, we did predict, however, that to the extent significant links emerged, ToM would be more strongly linked to thought problems and EC to attention problems.

Developmentally, ToM and EC indeed were early childhood predictors. Poorer early ToM predicted later thought problems; Poorer early EC predicted increased later attention problems. Our reasoning was that poorer early childhood ToM could signal that a child has difficulties representing the mental states of himself/herself and others. Such accumulated misrepresentations starting early in life could fuel loss of contact with reality and underpin later more severe thought problems. Similarly, poorer early EC indicates childhood problems in consciously controlling impulses and emotions, and extending this into preadolescence would underpin more extensive attention difficulties.

Thus, ToM and EC were distinct predictors with different developmental pathways to psychological adjustment outcomes (i.e., ToM-Thought Problems and EC-Attention Problems). Although our analyses allowed the possibility that ToM might link to attention problems and/or EC might link to thought problems, they did not. The distinct developmental pathways of thought and attention problems may suggest different developmental underpinnings of psychological disorders related to thought and attention problems. Potentially, ToM/EC may help identify various types of psychological symptoms within a disorder. Furthermore, meaningful differentiations of comorbid psychological disorders might be based on these ToM/EC-specific developmental pathways (see, e.g.47, for further thoughts on using ToM/EC for identifying neuropsychological subtypes).

Concerning our ToM-EC examinations, we found that ToM at age 3 predicted EC at age 6, but EC at age 3 did not predict ToM at age 6. Not all ToM-EC studies find this unidirectional relation48,49, but many have50,51. Theoretically, our findings align more closely with the developmental EC-emergence account than the EC-expression account of ToM development, as they indicate that early ToM insights contribute to the subsequent development of ToM itself and also EC (i.e., the ToM → EC pathway), rather than ToM performance merely reflecting expression constrained by EC-dependent task execution (which centers more heavily on the EC → ToM pathway).

More broadly, because early ToM and EC underpin thought and attention problems, our findings are consistent with (1) the neurodevelopmental model of psychological disorders52 and (2) the dimensional view of psychological disorders53. The neurodevelopmental model argues that abnormal neurodevelopmental processes – here, poorer ToM and EC in particular – appear considerably before the onset of any mental health problems (e.g., ADHD, ASD, OCD, psychosis, etc.), which is merely the end stage of extended developmental processes. Likewise, our findings are best interpreted in dimensional rather than categorical views. A dimensional view conceptualizes psychological difficulties as continuous constructs that vary in degree across individuals; in contrast, a categorical view classifies individuals into distinct groups based on the presence or absence of a disorder. Indeed, we considered thought and attention problems continuous constructs with variation measured across numerous items rather than a discrete diagnosis.

A clinical implication deserves mention: ToM and EC might be candidate targets for early screening, particularly for later thought and attention problems, that may suggest potential psychological disorders. Take ADHD as an example, which may be evaluated by our attention problems measure. Early screening helps detect potential risk for later ADHD, and our findings imply that EC difficulties may help identify children at high risk for ADHD. Similarly, children with poorer ToM in early childhood may benefit from early intervention54 aimed at reducing thought problems that may help prevent later related psychological disorders, such as ASD, OCD, or psychosis. Indeed, although many psychological symptoms themselves are difficult to assess or non-apparent in early childhood (e.g., at age 3), measuring precursors, such as EC and ToM, and intervening early is feasible54,55.

Several limitations deserve brief note. First, we offer informative but essentially exploratory evidence revealing ToM/EC mechanisms. Further research would be needed to replicate and extend our findings in a more confirmatory fashion. Moreover, we do not provide data regarding our participants’ later-emerging mental health diagnoses or symptoms. Thus, whether early childhood ToM/EC and preadolescent thought/attention problems can indeed predict later clinical outcomes remains unclear without further research. Relatedly, given that our study is limited to three early waves of measurement, establishment of more extended longitudinal trajectories (e.g., from early childhood, to middle childhood, to preadolescence, to adolescence, and to emerging adulthood) awaits more extended developmental psychopathology research. Also, as shown in Table 2, while our sample was heterogeneous, encompassing children from lower-middle to upper-middle-income families and representative of a medium-size Midwest college town, we cannot make firm generalizations to low-income samples and/or samples with stronger representations of minority children. Future research should include more diverse and nationally representative samples to demonstrate sociodemographic-related specificity, commonality, and generalizability of the developmental links between ToM/EC and thought/attention problems.

Our findings, while consistent and significant, are modest in that standardized coefficients were in the 0.15 to 0.30 range and not more substantial, implying the existence of other relevant factors within the predictive relations. On the one hand, in other studies with older children and adults, many predictors or risk factors correlate with more definitive clinical symptoms, such as adverse life events and affective dysregulations56. These could complement or moderate early predictors, in addition to ToM and EC. On the other hand, in terms of specificity, ToM and EC are consistently found to be crucial contributors or associates of many other mental illnesses, in addition to thought/attention problems, such as internalizing and externalizing symptoms, ADHD, and problem behaviors57. Thus, with our focus on ToM/EC, we do not suggest that other factors are not critical in developing thought/attention problems, and we do not imply that other disorders are not associated with or predicted by ToM or EC deficits. For example, ToM/EC could play a role as mediators/moderators in the pathways between other factors and thought/attention problems. In fact, a recent study found relevant evidence, showing that early childhood trauma could predict ToM impairments in patients with severe thought problems58. Moreover, another theoretically plausible scenario is that ToM and EC could interact in predicting later thought and attention problems. For example, a compensatory relationship might exist, such that strong skills in one domain mitigate the negative effects of weaknesses in the other; or, a synergistic effect may occur, whereby deficits in both domains exacerbate later difficulties to a greater extent than either deficit alone. Future research could examine these potential factors and interactions further to understand the developmental trajectories and early predictors of thought and attention problems more comprehensively.

More importantly, while emphasizing the importance of more comprehensively integrative studies, we call for future studies to jointly consider cognitive (e.g., ToM/EC), along with environmental (e.g., early childhood trauma), genetic (e.g., family history), and neural factors to provide a thorough perspective of developmental psychopathology.

Regardless of these limitations, our findings demonstrate predictive, developmental links between ToM, EC, thought problems, and attention problems. This demonstration has theoretical implications for developmental psychopathology accounts, specifically about early social-cognitive factors in childhood mental health risks. If confirmed and extended, it also has potential practical implications for early childhood screening and intervention efforts.

Data availability

The data are not available to the public as they contain confidential mental health information of participants. Requests for access to portions of the data can be sent to Sheryl L. Olson. The code will also be made available upon request.

References

Yu, C. L. & Wellman, H. M. Young children treat puppets and dolls like real persons in theory of Mind research: A meta-analysis of false-belief Understanding across ages and countries. Cogn. Dev. 63, 101197 (2022).

Yu, C. L. & Wellman, H. M. A meta-analysis of sequences in theory-of-mind understandings: theory of Mind scale findings across different cultural contexts. Dev. Rev. 74, 101162 (2024).

Rothbart, M. K. Temperament and development. In Temperament in Childhood (eds Kohnstamm, G. A. et al.) 187–247 (Wiley, 1989).

Wellman, H. M. Making Minds: How Theory of Mind Develops (Oxford Univ. Press, 2014).

Yu, C. L. & Wellman, H. M. Where do differences in theory of Mind development come from? An agent-based model of social interaction and theory of Mind. Front. Dev. Psychol. 1, 1237033 (2023).

Lecce, S., Caputi, M., Pagnin, A. & Banerjee, R. Theory of Mind and school achievement: the mediating role of social competence. Cogn. Dev. 44, 85–97 (2017).

Neppl, T. K., Jeon, S., Diggs, O. & Donnellan, M. B. Positive parenting, effortful control, and developmental outcomes across early childhood. Dev. Psychol. 56, 444 (2020).

Hoogenhout, M. & Malcolm-Smith, S. Theory of Mind predicts severity level in autism. Autism 21, 242–252 (2017).

Yu, C. L. & Wellman, H. M. All humans have a ‘theory of mind’. Autism Dev. Disord. 53, 2531–2534 (2023).

Santens, E., Claes, L., Dierckx, E. & Dom, G. Effortful control–A transdiagnostic dimension underlying internalizing and externalizing psychopathology. Neuropsychobiology 79, 255–269 (2020).

Masten, A. S. et al. Developmental cascades: linking academic achievement and externalizing and internalizing symptoms over 20 years. Dev. Psychol. 41, 733 (2005).

Diler, R. S. et al. The child behavior checklist (CBCL) and the CBCL-bipolar phenotype are not useful in diagnosing pediatric bipolar disorder. J. Child. Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 19, 23–30 (2009).

Diler, R. S., Uguz, S., Seydaoglu, G. & Avci, A. Mania profile in a community sample of prepubertal children in Turkey. Bipolar Disord. 10, 546–553 (2008).

Ivarsson, T., Melin, K. & Wallin, L. Categorical and dimensional aspects of co-morbidity in obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry. 17, 20–31 (2008).

Hoffmann, W., Weber, L., König, U., Becker, K. & Kamp-Becker, I. The role of the CBCL in the assessment of autism spectrum disorders: an evaluation of symptom profiles and screening characteristics. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 27, 44–53 (2016).

Salcedo, S. et al. Diagnostic efficiency of the CBCL thought problems and DSM-oriented psychotic symptoms scales for pediatric psychotic symptoms. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry. 27, 1491–1498 (2018).

Frith, C. D. The Cognitive Neuropsychology of Schizophrenia (Psychology, 1992).

Janeck, A. S., Calamari, J. E., Riemann, B. C. & Heffelfinger, S. K. Too much thinking about thinking? Metacognitive differences in obsessive–compulsive disorder. J. Anxiety Disord. 17, 181–195 (2003).

Sprong, M., Schothorst, P., Vos, E., Hox, J. & Van Engeland, H. Theory of Mind in schizophrenia: meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry. 191, 5–13 (2007).

Bora, E. & Pantelis, C. Theory of Mind impairments in first-episode psychosis, individuals at ultra-high risk for psychosis and in first-degree relatives of schizophrenia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 144, 31–36 (2013).

Velikonja, T., Fett, A. K. & Velthorst, E. Patterns of nonsocial and social cognitive functioning in adults with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 76, 135–151 (2019).

Oliver, L. D. et al. Social cognitive performance in schizophrenia spectrum disorders compared with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. JAMA Psychiatry. 78, 281–292 (2021).

Bora, E. Social cognition and empathy in adults with obsessive compulsive disorder: a meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 316, 114752 (2022).

Sloover, M., van Est, L. A., Janssen, P. G. & Hilbink, M. Ee, E. A meta-analysis of mentalizing in anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive and related disorders, and trauma and stressor related disorders. J. Anxiety Disord. 92, 102641 (2022). van.

Polderman, T. J., Boomsma, D. I., Bartels, M., Verhulst, F. C. & Huizink A. C. A systematic review of prospective studies on attention problems and academic achievement. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 122, 271–284 (2010).

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of psychological disorders (DSM-5®) (American Psychiatric Pub., 2013).

Barkley, R. A. Behavioral inhibition, sustained attention, and executive functions: constructing a unifying theory of ADHD. Psychol. Bull. 121, 65 (1997).

Aarnoudse-Moens, C. S. H., Weisglas‐Kuperus, N., Duivenvoorden, H. J., Oosterlaan, J. & van Goudoever, J. B. Neonatal and parental predictors of executive function in very preterm children. Acta Paediatr. 102, 282–286 (2013).

Ciuhan, G. C. & Iliescu, D. Depression and learning problems in children: executive function impairments and inattention as mediators. Acta Psychol. 220, 103420 (2021).

Arias, A. A., Rea, M. M., Adler, E. J., Haendel, A. D. & Van Hecke, A. V. Utilizing the child behavior checklist (CBCL) as an autism spectrum disorder preliminary screener and outcome measure for the PEERS® intervention for autistic adolescents. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 52, 2061–2074 (2022).

Atherton, O. E., Lawson, K. M., Ferrer, E. & Robins, R. W. The role of effortful control in the development of ADHD, ODD, and CD symptoms. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 118, 1226 (2020).

Moses, L. J. Executive accounts of theory-of-mind development. Child. Dev. 72, 688–690 (2001).

Wade, M. et al. On the relation between theory of Mind and executive functioning: A developmental cognitive neuroscience perspective. Psychon Bull. Rev. 25, 2119–2140 (2018).

Achenbach, T. M. & Rescorla, L. Manual for the ASEBA school-age Forms & Profiles: an Integrated System of multi-informant Assessment (ASEBA, 2001).

Olson, S. L., Sameroff, A. J., Kerr, D. C. R., Lopez, N. L. & Wellman, H. M. Developmental foundations of externalizing problems in young children: the role of effortful control. Dev. Psychopathol. 17, 25–45 (2005).

Wechsler, D. WPPSI-R: Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence-Revised (Psychological Corporation, 1989).

Bartsch, K. & Wellman, H. Young children’s attribution of action to beliefs and desires. Child. Dev. 60, 946–964 (1989).

Song, J. H., Waller, R., Hyde, L. W. & Olson, S. L. Early callous-unemotional behavior, theory-of-mind, and a fearful/inhibited temperament predict externalizing problems in middle and late childhood. J. Abnorm. Child. Psychol. 44, 1205–1215 (2016).

Lane, J. D., Wellman, H. M., Olson, S. L., LaBounty, J. & Kerr, D. C. R. Theory of Mind and emotion Understanding predict moral development in early childhood. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 28, 871–889 (2010).

Wellman, H. M., Lane, J. D., LaBounty, J. & Olson, S. L. Observant, nonaggressive temperament predicts theory-of‐mind development. Dev. Sci. 14, 319–326 (2011).

Olson, S. L., Lopez-Duran, N., Lunkenheimer, E. S., Chang, H. & Sameroff, A. J. Individual differences in the development of early peer aggression: integrating contributions of self-regulation, theory of mind, and parenting. Dev. Psychopathol. 23, 253–266 (2011).

Olson, S. L., Choe, D. E. & Sameroff, A. J. Trajectories of child externalizing problems between ages 3 and 10 years: contributions of children’s early effortful control, theory of mind, and parenting experiences. Dev. Psychopathol. 29, 1333–1351 (2017).

Kochanska, G., Murray, K., Jacques, T. Y., Koenig, A. L. & Vandegeest, K. A. Inhibitory control in young children and its role in emerging internalization. Child. Dev. 67, 490–507 (1996).

Kochanska, G., Murray, K. & Coy, K. C. Inhibitory control as a contributor to conscience in childhood: from toddler to early school age. Child. Dev. 68, 263–277 (1997).

Choe, D. E., Olson, S. L. & Sameroff, A. J. Effects of early maternal distress and parenting on the development of children’s self-regulation and externalizing behavior. Dev. Psychopathol. 25, 437–453 (2013).

Sitskoorn, M. M., Aleman, A., Ebisch, S. J. H., Appels, M. C. M. & Kahn, R. S. Cognitive deficits in relatives of patients with schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 71, 285–295 (2004).

Bora, E., Veznedarouglu, B. & Vahip, S. Theory of Mind and executive functions in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: A cross-diagnostic latent class analysis for identification of neuropsychological subtypes. Schizophr Res. 176, 500–505 (2016).

Carlson, S. M., Mandell, D. J. & Williams, L. Executive function and theory of mind: stability and prediction from ages 2 to 3. Dev. Psychol. 40, 1105–1122 (2004).

Müller, U., Liebermann-Finestone, D. P., Carpendale, J. I. M., Hammond, S. I. & Bibok, M. B. Knowing Minds, controlling actions: the developmental relations between theory of Mind and executive function from 2 to 4 years of age. J. Exp. Child. Psychol. 111, 331–348 (2012).

McAlister, A. R., Peterson, C. C. & Siblings Theory of mind, and executive functioning in children aged 3–6 years: new longitudinal evidence. Child. Dev. 84, 1442–1458 (2013).

Wade, M., Browne, D. T., Plamondon, A., Daniel, E. & Jenkins, J. M. Cumulative risk disparities in children’s neurocognitive functioning: A developmental cascade model. Dev. Sci. 19, 179–194 (2016).

Rapoport, J. L., Giedd, J. N. & Gogtay, N. Neurodevelopmental model of schizophrenia: update 2012. Mol. Psychiatry. 17, 1228–1238 (2012).

Adam, D. On the spectrum. Nature 496, 416 (2013).

Wellman, H. M. & Peterson, C. C. Deafness, thought bubbles, and theory-of-mind development. Dev. Psychol. 49, 2357–2367 (2013).

Thorell, L. B., Lindqvist, S., Nutley, B., Bohlin, S., Klingberg, T. & G. & Training and transfer effects of executive functions in preschool children. Dev. Sci. 12, 106–113 (2009).

Fusar-Poli, P. et al. Deconstructing vulnerability for psychosis: Meta-analysis of environmental risk factors for psychosis in subjects at ultra high-risk. Eur. Psychiatry. 40, 65–75 (2017).

Korkmaz, B. Theory of Mind and neurodeveloppsychological disorders of childhood. Pediatr. Res. 69, 101–108 (2011).

Kincaid, D. et al. An investigation of associations between experience of childhood trauma and political violence and theory of Mind impairments in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 270, 293–297 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We are deeply grateful to Henry M. Wellman for his invaluable support and insightful feedback during the drafting of this manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Grant R01MH57489 from the National Institute of Mental Health to Sheryl L. Olson and by funds from Oklahoma State University to Chi-Lin Yu.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Chi-Lin Yu: Conceptualization, Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Writing—original Draft, Writing—review and editing. Sujin Lee: Conceptualization, Data Curation, Writing – Review & Editing, Project Administration. Sheryl L. Olson: Methodology, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation, Writing—review and editing, Supervision, Project Administration, Funding Acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, CL., Lee, S. & Olson, S.L. Early childhood theory of mind and effortful control underpin preadolescent thought and attention problems. Sci Rep 15, 40453 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24007-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24007-6