Abstract

The objectibve of this study was to analyze the prevalence, geographic distribution, and trends of myopia among Chinese children aged 7 to 12 years, in order to provide a basis for prevention and management. Data for children aged 7 to 12 years from the Chinese National Survey on Students’ Constitution and Health (1985–2019) and 2019 myopia study for Han Chinese students aged 6 to 12 years were analyzed. The chi-square test and polynomial regression models were used to assess changes in myopia prevalence and predict trends. Data from 1,063,280 children in 30 provinces (excluding Tibet, Hong Kong, Macau) showed a 3.3-fold increase in myopia from 12.69% in 1985 to 41.33% in 2019. Myopia peaked in 2010, then slowed. In 2019, myopia prevalence among Han Chinese children aged 6–12 was 37.54%, higher in urban (40.39%) than rural (34.62%) areas. The eastern region had the highest rate (40.38%). Projections estimate a prevalence of 40.39% in 2025, decreasing to 33.46% by 2030. Rural areas showed a faster increase from 2014 to 2019, with rural rates expected to surpass urban rates by 2022. Myopia prevalence is high among Chinese children aged 7 to 12 years, particularly in rural areas where rates are rising, underscoring the need for targeted prevention strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Myopia is a refractive error of the eye that causes close objects to appear clear and far objects to appear blurry1,2. According to the World Vision Report 2019, at least 2.2 billion people worldwide live with visual impairments. This term encompasses conditions ranging from mild vision loss to blindness, including impairments due to uncorrected refractive error. In the WHO classification, distance vision impairment is defined as presenting visual acuity worse than 6/12 in the better eye, with further categories distinguishing mild, moderate, severe impairment, and blindness. Myopia remains one of the most common causes of visual impairment affecting approximately 312 million people under the age of 19 years worldwide3. If left untreated, myopia can hinder learning and daily activities by making it hard for children to see distant material clearly. Moreover, the eyeball in severe myopia patients tends to be elongated. The shape of the eyeball causes the retina to stretch and thin, making it more prone to detachment and development of glaucoma, especially if the eye pressure is elevated. Since these complications can lead to blindness regular eye check-ups are crucial for early detection and the provision of effective interventions.

The Chinese National Survey on Students’ Constitution and Health (CNSSCH) conducted between 1985 and 2019 has shown that the prevalence of myopia has increased significantly amongst Chinese children and urgent public health interventions are required to reduce this condition, especially in urban areas4,5. Myopia usually occurs due to progressive structural changes in the eyes. Various genetic and environmental factors can lead to the development of myopia. However, in recent years, lifestyle changes such as frequent use of electronic devices, academic pressures, and insufficient outdoor activities may have increased the time spent by children looking at nearby objects, eventually contributing to a sharp increase in the prevalence of this condition among children and adolescents worldwide. Currently, there is no way to reverse myopia, however, the blurry vision caused by these structural changes can be corrected using glasses, contact lenses, or laser surgery. If the changes within the eyeball are detected early enough, it is possible to slow down myopia progression through lifestyle changes6,7.

This study aimed to evaluate the prevalence, geographic distribution, and future trends of myopia amongst Han Chinese children aged 6 to 12 years using data extracted from the CNSSCH and the 2019 myopia survey. The outcomes of this study could be used to inform public health policy and to develop effective health intervention strategies to improve the vision of Chinese children and adolescents as indicated by the Chinese health strategy 2030.

Methods

Data sources

The demographic and vision acuity data of Chinese children was sourced from the CNSSCH reports conducted in 1985, 1991, 1995, 2000, 2004, 2010, 2014, and 2019. The CNSSCH is the largest national survey evaluating the physical fitness and health of Chinese children and adolescents. This survey made use of stratified cluster random sampling to obtain a representative sample of the Chinese population. The study subjects included Han Chinese children aged between 7 to 12 years living in 30 provinces, autonomous regions, and municipalities in China (excluding Tibet, Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan). Additionally, data was also extracted from the 2019 myopia Han Chinese survey of primary school students aged between 6 to 12 years, which is part of the CNSSCH survey. This dataset specifically focused on myopia prevalence and followed the same rigorous testing protocols as the broader CNSSCH survey. The 2019 data collection included standardized vision screening procedures conducted by professional teams across all regions, ensuring the accuracy and reliability of the results. The data were accessed and extracted for research purposes on 15/02/2024.

Vision measurements and myopia definition

Vision measurements were conducted according to standardized CNSSCH protocols by trained personnel, under strict quality control supervision. Visual acuity was measured at a distance of 5 m using a standardized chart, with each 0.1 unit change corresponding to one line on the chart. Children were first tested for uncorrected visual acuity (UCVA). Those with UCVA < 5.0 in either eye underwent a lens test. If vision improved with a negative lens, the eye was classified as myopic, and individual-level myopia prevalence was defined as myopia in at least one eye.

This approach is the official protocol of the CNSSCH and has been consistently applied across all survey years. Although spherical equivalent refraction (diopters) is the gold standard for defining myopia, large-scale national surveys such as the CNSSCH adopt this method because of its feasibility, cost-effectiveness, and operational efficiency in field investigations. Previous evaluations have demonstrated that this approach provides acceptable accuracy for population-level monitoring of myopia prevalence and trends.

Statistical analysis

The children were divided into four groups based on gender (male or female) and living location (urban or rural). Additionally, children aged 7 to 12 were divided into six age groups: 7-year-olds, 8-year-olds, 9-year-olds, 10-year-olds, 11-year-olds, and 12-year-olds. The Mantel–Haenszel trend test was used to calculate the P values for trend values for each group.

Joinpoint regression analysis was performed using the Joinpoint software version 5.1.0 developed by the National Cancer Institute’s Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences in the United States. This software makes use of piecewise regression models to analyze time series data to detect significant shifts in trends such as changes in disease prevalence rates8. Monte Carlo permutation tests were employed to identify the statistically significant number of joinpoints, thereby determining the best-fitting model. The identified joinpoints highlighted the inflection points in the long-term trends of myopia rates. The Annual Percent Change (APC) and the Average Annual Percent Change (AAPC), at the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. The APC measures the rate of change in myopia prevalence per year between two consecutive joinpoints. APC was used to assess trend changes over specific periods for specific joinpoints, while AAPC was used to assess changes over fixed time intervals, regardless of the presence of joinpoints. In the absence of joinpoints, the APC and AAPC values will be the same.

Polynomial regression models (degree 3) were utilized to analyze trends in myopia prevalence from 1985 to 2019, with years serving as the independent variable and myopia prevalence rates as the dependent variable. These models enabled predictions of myopia prevalence rates according to age, gender, and location, for the years 2025 and 2030. To evaluate model performance and avoid overfitting, goodness-of-fit indicators including R2, adjusted R2, Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) were calculated. All statistical analyses were conducted using R version 4.3.3.

The continuous data extracted from the Han Chinese primary school students survey were expressed as mean ± standard deviation, while the categorical data were expressed as rates and composition ratios. The chi-square test was used to identify myopia risk factors.

Except for the Joinpoint regression analysis, all other analyses were performed using the R software version 4.3.3 (R Development Core Team, Vienna, Austria). For all statistical tests, a two-sided p-value below 0.05 was deemed statistically significant.

Ethics statement

This study is based on publicly available, de-identified data obtained from the Chinese National Survey on Students’ Constitution and Health (CNSSCH). All data were anonymized prior to researcher access, and no personally identifiable information was available. In accordance with institutional and national ethical guidelines, the use of such anonymized public data is exempt from ethical review and informed consent requirements.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of the 1985 to 2019 survey participants

The data of 1,063,280 children aged between 7 to 12 years living in 30 provinces in China were extracted from the CNSSCH database. Table 1 indicates the number of children screened during the 8 health surveys conducted between 1985 and 2019. The distribution of age, gender, and location remained relatively similar throughout each survey. Between 1985 to 2019, the prevalence of myopia increased by 3.296 folds from 12.69% to 41.33% (Table 1).

Geographical prevalence of myopia among children aged 6 to 12 years according to the Chinese myopia survey conducted in 2019

In 2019, the prevalence of myopia amongst Chinese children living in urban areas was significantly higher than that observed in rural areas (40.39% versus 34.62%, p < 0.001) (Table 2).

Gender prevalence of myopia among children aged 6 to 12 years according to the Chinese myopia survey conducted in 2019

The prevalence of myopia was also significantly higher in girls when compared to boys (34.94% versus 40.16% P < 0.001) (Table 3).

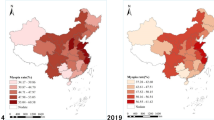

Sociodemographic characteristics of the children in the 2019 Han Chinese Myopia study

A total of 123,301 Han Chinese children participated in the myopia study, of whom 61,820 (50.05%) were boys and 61,481 (49.94%) were girls. The overall myopia prevalence rate in this cohort was 37.54%. The eastern coastal and central-western regions, such as Shandong Province, Zhejiang Province, and Shanghai had the highest prevalence of myopia, while provinces located in the southern and central-western parts of China, such as Hainan Province, Jiangxi Province, and Guizhou Province had the lowest prevalence of myopia (Table 4).

In addition, when applying the official four-region economic classification. The eastern region had the highest myopia prevalence rate at 40.38%, followed by the northeastern region at 36.89%. The myopia prevalence rates in the central and western regions were 35.07% and 36.36%, respectively. There were significant differences in myopia rates among different economic regions (χ2 = 239.964, P < 0.001), with the myopia rate in the eastern coastal region being significantly higher than that in the central and western regions (Table 5).

Changes in the prevalence of myopia between 1985 and 2019

The joinpoint regression analysis showed that from 1985 to 2019, the AAPC in the prevalence of myopia amongst Chinese children aged between 7 to 12 years was 3.61% (95% CI: 3.13–4.33%, P < 0.001) (Fig. 1). During this period, the best-fitting model had a joinpoint in 2010, indicating a change in trend. From 1985 to 2010, the APC in the prevalence of myopia was 4.51% (95% CI: 3.97–6.32%, P < 0.001). After 2010, the APC decreased to 1.16% (95% CI: -0.91–3.27%, P = 0.246).

Both boys and girls living in urban areas showed a joinpoint in 2010, with AAPCs of 2.89% (95% CI: 2.26–3.71%, P < 0.001) and 2.65% (95% CI: 2.21–3.20%, P < 0.001), respectively. After 2010, the APC for boys living in urban areas decreased from 3.82% (95% CI: 2.73–6.01%, P < 0.001) to 0.36% (95% CI: -2.22–3.28%, P = 0.525), while the APC for girls living in urban areas decreased from 3.67% (95% CI: 3.24–4.69%, P < 0.001) to -0.14% (95% CI: -2.01–1.77%, P = 0.972).

Similarly, between 1985 to 2019, both boys and girls living in rural areas showed a joinpoint in 2010, with AAPCs of 5.54% (95% CI: 4.61–7.27%, P < 0.001) and 4.88% (95% CI: 4.09–6.46%, P < 0.001), respectively. After 2010, the APC for boys living in rural areas decreased from 6.45% (95% CI: 3.80–12.45%, P < 0.001) to 2.70% (95% CI: -1.02–6.90%, P = 0.1323), while the APC for girls living in rural areas decreased from 5.87% (95% CI: 3.71–10.99%, P < 0.001) to 2.17% (95% CI: -1.14–5.97%, P = 0.1576).

Time trend analysis evaluating the prevalence of myopia

From 1985 to 2019, the myopia prevalence rate among Chinese children aged 7 to 12 years increased significantly in boys living in both urban (from 16.99% to 41.58%) and rural (from 5.43% to 34.98%) areas. Similarly, an increase in the prevalence of myopia was noted in girls living in urban (from 20.18% to 47.80) and rural (from 7.3% to 40.82%) areas. The increase in the myopia prevalence rate occurred more rapidly in rural areas in both girls (Rural: 5.55 versus Urban: 2.37 folds) and boys (Rural: 6.44 versus Urban: 2.44 folds).

The polynomial regression prediction model showed that by 2022, the myopia prevalence rate is expected to reach 39.48% for boys living in urban areas and 39.02% for boys living in rural areas. Similarly, by 2022 the myopia prevalence rate is also expected to increase for girls living in urban and rural areas up to 45.18% and 44.94%, respectively. After 2022, the overall prevalence of myopia is expected to decrease to 40.39% by 2025 and 33.46% by 2030 (Fig. 2) (Table 6). Moreover, the prevalence of myopia in children living in rural areas is expected to surpass that of children living in urban areas.

The polynomial regression models demonstrated strong explanatory power across all groups. For the overall population, the model achieved an R2 of 0.957 and an adjusted R2 of 0.925, indicating that over 90% of the variance in myopia prevalence was explained. Comparable performance was observed in subgroup analyses, with R2 values of 0.947 for urban boys, 0.952 for urban girls, 0.963 for rural boys, and 0.962 for rural girls. The adequacy of these models was further supported by low information criteria values (overall model: AIC = 45.6, BIC = 45.9), indicating reliable fit without overfitting. These results support the reliability of the fitted models and provide a sound statistical basis for projecting future myopia prevalence trends to 2025 and 2030.

Impact of age on the prevalence of myopia

A slight decrease in the prevalence of myopia was noted between 2014 and 2019 in children aged between 7 and 10 years. The prediction analysis showed that by 2025, the prevalence of myopia is expected to continue to decline in urban areas. Conversely in rural areas, an increase in the prevalence of myopia was noted for all age groups except for children aged between 7 to 8 years. Predictions indicate that by 2025 and 2030, the myopia rates for both boys and girls living in rural areas will continue to rise, especially in the older age groups, and will eventually surpass the prevalence of myopia in urban areas (Figs. 3, 4, 5 and 6).

Discussion

The prevalence of myopia has increased significantly during the past years, especially in Asian countries. Given the impact of myopia on learning and daily activities in children, there is a pressing need to study the prevalence and trends of myopia to develop effective health interventions. The CNSSCH aimed to assess the health status of Chinese children. A total of 8 surveys were conducted between 1985 and 2019. Therefore this study aimed to evaluate the visual acuity data of Chinese children registered in these surveys to determine the prevalence of myopia and predict future trends.

Our findings indicate that from 1985 to 2010, the prevalence of myopia increased. However, a joinpoint was observed in 2010, after which the upward trend slowed, and the prevalence showed a plateau without significant decline. The prevalence of myopia between 2014 and 2019 was higher in children living in urban areas compared to that of children living in rural areas. From 2014 to 2019, the myopia rates among children living in urban areas aged between 7 to 10 years decreased. Our prediction analysis revealed that after 2022, the prevalence of myopia in urban areas is expected to decline further and the prevalence of myopia in rural areas is expected to surpass that of urban areas.

Analysis of the myopia survey amongst Han Chinese students aged between 6 to 12 years conducted in 2019 revealed a prevalence rate of 37.54%. Various lifestyle issues may increase the risk of developing myopia such as excessive use of electronic devices and reading time 2,9,10,11,12. The prevalence of myopia in children living in rural areas was generally higher than that of children living in rural areas. The lifestyle and learning environment of urban students differ from those of rural students13. For example, children living in urban areas are more likely to make use of electronic devices for longer periods, while children living in rural areas are more likely to participate in outdoor activities14. As expected, the highly urbanized eastern coastal and central-western regions showed the highest prevalence of myopia. Since this region in China has higher levels of economic development, children living in this area may have more access to electronic devices, longer study hours, and spend less time outdoors2,9,10,11,12. Conversely, the prevalence of myopia was lower in the more rural Xinjiang, Jiangxi, and Guizhou Provinces. However, in some rural areas, the prevalence of myopia was higher than that of urban areas. For example, children in some rural areas may experience educational pressure and as a result, these children end up spending more time studying indoors, thereby increasing the risk of myopia. In rural areas, there is often a lack of awareness about the importance of vision care, which can result in children not receiving timely eye examinations and necessary treatments. This gap in knowledge means that myopia may be left undetected or untreated for extended periods, leading to more severe vision problems as the condition progresses. Without regular eye check-ups, the early signs of myopia are often missed, delaying crucial interventions that could help manage and slow the progression of the condition.

The prevalence of myopia tends to be lower in boys possibly because Chinese boys tend to prefer outdoor activities while girls are more inclined to engage in reading and studying. As a result, boys tend to spend less time focusing on nearby objects, thereby lowering their risk of developing myopia15,16,17.

Our findings indicate that the growth in the prevalence of myopia slowed down after 2010 in children living in urban areas. However, the same reversal was not observed in rural areas. If current trajectories continue, rural prevalence may surpass urban levels (‘urban–rural reversal’), as suggested by projections. As economic development progresses, the lifestyle of children living in rural areas may converge to match that of children living in urban areas and thus expose them to factors that may lead to an increased risk of developing myopia18. For instance, the "urban–rural reversal" in children’s myopia has already been observed in Hebei, Hubei, and Hunan 15.

Moreover, to curb the continuous increase in the myopia rate among children, China has also introduced a series of myopia prevention and control policies, such as the "Healthy Children Action Plan (2018–2020)" and the "Comprehensive Implementation Plan for Myopia Prevention and Control among Children and Adolescents". These policies may have contributed to the decline in myopia rates among urban boys and girls aged 7–10 years from 2014 to 201918,19,20. Additionally, in 2021, to further promote the prevention and control of myopia among children and adolescents, the Ministry of Education jointly formulated the "Bright Action Plan for Myopia Prevention and Control among Children and Adolescents (2021–2025)". While the introduction of these policies may have led to a reduction in myopia in urban areas, more efforts are required to facilitate the implementation of these policies in rural areas.

Overall our findings indicate that the prevalence of myopia among Han Chinese children tends to vary widely between boys and girls and across regions. In response to this situation, each region should develop myopia prevention and control strategies tailored to local conditions. High-prevalence areas should strengthen the regulation of electronic device usage time, advocate and implement scientifically reasonable eye habits, increase students’ outdoor activity time, improve indoor lighting conditions in schools, and carry out comprehensive vision health education to enhance the eye protection awareness of parents and students. Low-prevalence areas should maintain good living habits and learning environments, while also continuing to learn from the experiences of high-prevalence areas to prevent the increase in myopia rates due to poor eye habits and environmental factors21,22,23.

This study has certain limitations that have to be acknowledged. Since 1985, China has conducted a national student physical fitness and health survey approximately every five years, providing eight rounds of CNSSCH data from 1985 to 2019. As a result, the Joinpoint regression analysis was based on eight data points, which may limit statistical precision. Nevertheless, the CNSSCH is the only nationwide, long-term surveillance dataset available, and its consistency and representativeness across more than three decades provide unique value for evaluating secular trends. Importantly, the CNSSCH is an ongoing program, and the ninth round has already been launched in 2025, which will allow future research to extend and validate our findings.

In addition, from 1985 to 2014, the survey participants were primarily 7-year-old children, with 6-year-olds only included in the 2019 survey. Moreover, the data used in this study comes from cross-sectional surveys, limiting the ability to explore causal relationships. Future research should focus on conducting cohort studies.

Conclusion

The myopia rate among Chinese children aged between 7 to 12 years showed a continuous upward trend from 1985 to 2019. While urban areas showed signs of stabilization after 2010, rural areas continued to experience rising prevalence. These findings underscore the need for targeted and effective preventive strategies to reduce the burden of this condition.

Data availability

The datasets used in this study were obtained from the China National Student Physical Fitness and Health Survey (CNSSCH), which are published in physical volumes but are not available online. These data can be requested from libraries or from the corresponding author.

References

Cheng, H. C., Chang, K., Shen, E., Luo, K. S. & Ying, Y. H. Risk factors and behaviours of schoolchildren with myopia in Taiwan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17(6), 1967 (2020).

Arbaz, A., Kumar, R. & Trivedi, R. Factors influencing the incidence of myopia. J. Ophthalmol. Res. Rev. Rep. 5, 1–5 (2024).

World Health Organization. World report on vision. World Health Organization. [cited 2024 Aug 22]. 160 p. Available from: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/328717 (2019).

Dong, B. et al. Adolescent health and healthy china 2030: A review. J. Adolesc. Health 67(5), S24–S31 (2020).

Bao, Y., Meng, S., Sun, Y., Jie, S. & Lu, L. Healthy china action plan empowers child and adolescent health and wellbeing. Lancet Public Health 4(9), e448 (2019).

Wang, J. et al. Normative value of hyperopia reserve and myopic shift in Chinese children and adolescents aged 3–16 years. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 108(7), 1024–1029 (2024).

Biswas, S. et al. The influence of the environment and lifestyle on myopia. J. Physiol. Anthropol. 43(1), 7 (2024).

Dang, J. et al. Secular trend and projection of overweight and obesity among Chinese children and adolescents aged 7–18 years from 1985–2019: Rural areas are becoming the focus of investment. Chin. Med. J. 138(03), 311–317. https://doi.org/10.1097/CM9.0000000000003123 (2025).

Grzybowski, A., Kanclerz, P., Tsubota, K., Lanca, C. & Saw, S. M. A review on the epidemiology of myopia in school children worldwide. BMC Ophthalmol. 20(1), 27 (2020).

Yu, M. et al. Global risk factor analysis of myopia onset in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 18(9), e0291470 (2023).

Kusumawardhany, R. & Dharianta, R. Factors related to the incidence of myopia in students at the junior high school 2 in mojokerto city. Literasi Kesehat Husada J. Inf. Ilmu Kesehat. 8(2), 45–50 (2024).

Liu, Z. H. et al. Exercise is the dominant factor affecting the development of teenagers’ eyesight—based on the Bayesian model averaging. Front. Public Health 10, 1014227 (2022).

Wang, Q., Bi, H. Y. & Wang, C. F. Familial aggregation and heritability of myopia: A local population survey in Shanxi, China. J. Trop. Med. 2021, 1–7 (2021).

Xiang, F. et al. Increases in the prevalence of reduced visual acuity and myopia in chinese children in guangzhou over the past 20 years. Eye 27(12), 1353–1358 (2013).

Huang, Z., Song, D., Tian, Z., Wang, Y. & Tian, K. Prevalence and associated factors of myopia among adolescents ag ed 12–15 in shandong province, China: A cross-sectional study. [cited 2024 Aug 3]. Available from: https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-4476518/v1 (2024).

Enthoven, C. et al. Gender issues in myopia: A changing paradigm in generations. [cited 2024 Aug 3]. Available from: https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-3324708/v1 (2024).

Xiang, Z. Y. & Zou, H. D. Recent epidemiology study data of myopia. J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 1–12 (2020).

Vision Health Branch of Chinese Association for Student Nutrition and Health Promotion; Public Health Ophthalmology Branch of Chinese Preventive Medicine Association. Chinese expert consensus on comprehensive public health intervention for myopia prevention and control in children and adolescents. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 103(38), 3002–3009 (2023).

Zhu, Z. et al. Interventions recommended for myopia prevention and control among children and adolescents in China: A systematic review. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 107(2), 160–166 (2023).

Morgan, I. G. & Jan, C. L. China turns to school reform to control the myopia epidemic: a narrative review. Asia Pac. J. Ophthalmol. 11(1), 27–35 (2022).

Ang, M. et al. Review: Myopia control strategies recommendations from the 2018 WHO/IAPB/BHVI meeting on myopia. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 104(11), 1482–1487 (2020).

Schaeffel, F. Prävention der myopie. Ophthalmol. 116(6), 509–517 (2019).

Alvarez-Peregrina, C. Prevention and public awareness of myopia. Acta Ophthalmol. 102, aos.16410 (2024).

Funding

This work was supported by the Heilongjiang Province Department of Education’s University Student Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program (Project No. S202310222038), the “Dongji” Academic Team from Jiamusi University (Project No. DJXSTD202405), and the Health Commission of Heilongjiang Province’s Research Plan Project (Project No. 202312120302269).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.C. contributed to the conceptualization and design of the study, developed the methodology, conducted the data analysis, created the software used in the research, and drafted the original manuscript. L.Z. supervised the study, managed the project, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. Y.X. was responsible for data curation and performed the formal analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, X., Xie, Y. & Zhu, L. Trends and predictions of myopia among Chinese children aged 7–12 years from 1985 to 2019. Sci Rep 15, 40250 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24030-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24030-7