Abstract

This study analyzes the \((2+1)\)-dimensional Boussinesq equation, a fundamental model in coastal and ocean engineering for describing the propagation of long waves in shallow water. Understanding the nonlinear wave structures of this equation is essential for predicting energy localization, wave stability, and extreme events such as rogue waves. To this end, the Hirota bilinear method is employed to derive explicit \(\mathbb {N}\)-soliton solutions, explicitly classifying them into bright and dark types according to parameter criteria. Breather solutions in different planes are constructed using the complex conjugate approach, while the long-wave limit method is applied to obtain first- and second-order lump waves, representing rationally localized structures. Furthermore, four hybrid solutions combining solitons, lumps, and breathers are developed, and their interaction dynamics (e.g. soliton–soliton and soliton–lump collisions) are systematically analyzed. The interactions are shown to be elastic, and all structures retain their identities after collision. A novel contribution of this work is the use of a bidirectional scatter plot technique to compare the behaviors of these solutions across parameter ranges, providing a unified framework for identifying conditions under which different solutions exhibit similar dynamics. The results demonstrate several practical insights: for example, lump solutions preserve their localization over time, modeling stable energy concentrations, while soliton–breather interactions capture oscillatory instabilities relevant for predicting extreme wave events. These contributions extend beyond previous studies by offering both a systematic taxonomy of nonlinear wave structures and a diagnostic tool for engineers to evaluate wave interactions under varying oceanic conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A NLEE is a mathematical and physical model that characterizes temporal evolution in nonlinear systems and remains a key area of interest in nonlinear science. These models are essential in tackling problems in various domains such as image processing1, neuroscience2, fluid dynamics3, and data science4, among others. A key area of research in mathematics, physics, and other disciplines is the development of exact solutions for NLEEs. Achieving these exact solutions aids in the exploration of nonlinear phenomena in nature and provides a scientific explanation for these phenomena. Over time, various scientific and efficient methods have been introduced to derive these exact solutions, including bilinear5, unified solver approach6, LWL7, generalized Kudryashov8, modified F-expansion9, Darboux transform10, trial function11, and \(\phi ^6\) model expansion12.

The soliton, breather, and lump solutions13 represent distinct types of exact solutions that hold significant research value in various domains, including Bose–Einstein condensates14, marine physics15, among others. The interaction of these exact solutions leads to a more intricate solution structure, illustrating the complex movement patterns observed in natural systems. In recent years, the study of interaction phenomena has gained increasing attention from researchers as a significant topic in NLEEs. Solitons serve as a fundamental and ideal framework for exploring various nonlinear localized waves, offering a valuable approach to studying nonlinear wave interactions due to their inherent particle-like behavior during propagation. In an integral system, solitons with different velocities retain their original shape and velocity after interaction, with their fundamental physical properties remaining unchanged. In the literature, multi-wave solitons are rarely explored, making them a hot research topic due to their ability to reveal more complex wave behaviors16. Beyond solitons, breather solutions to NLEEs serve as intriguing examples for exploring nonlinear wave interactions due to their distinctive self-oscillatory characteristics and complex synchronization behaviors. Given these properties, phase-sensitive breather interactions have garnered significant attention in recent studies17.

Lump waves, introduced by Petviashvili18, are characterized as specific types of rational function for NLEEs and exhibit spatial localization in all directions. These types of characterized solutions for NLEEs, as discussed above, remain relatively scarce in the literature. There is a significant need to explore additional solutions to uncover the yet unknown behaviors of NLMs. Motivated by this, the focus is on deriving new and novel multi-wave solitons, as well as lump, breather, and interaction solutions for the (2+1)-dimensional Boussinesq equation introduced by Wazwaz19.

Here, \(\delta _1,\delta _2\), and \(\delta _3\) are nonzero parameters, where the coefficients \(\delta _1\), and \(\delta _2\) are associated with the vertical extent of the fluid and the characteristic speed of extended waves in shallow water. The Boussinesq equation was originally proposed by Boussinesq in 1871 to model the transmission of extended waves in shallow water20. Over time, various extensions of this equation have been developed by different researchers. More recently, Wazwaz introduced several forms of the Boussinesq equation in different dimensions. In this study, the focus is on its analysis in (2 + 1) dimensions. Equation (1) describes the propagation of gravity waves across the water surface, particularly focusing on the head-on interaction of oblique waves. Equation (1) has gained significant attention in various fields due to its consideration of nonlinearities and dispersion. Its applications include:

-

It is used in models related to tsunami waves and other hydrodynamic phenomena.

-

It is explored in studies involving free-surface dynamics.

-

It is used to model magnetoacoustic waves in plasmas containing iron ions.

-

It is applied in the study of wave propagation through elastic rods.

Literature review

Various researchers have applied different techniques to analyze the various forms of the Boussinesq equation across multiple dimensions. Wazwaz and Kaur19 investigated Eq. (1) by examining its complete integrability via the Painlevé test. They derived multiple soliton solutions using a simplified Hirota’s method. Additionally, the exponential expansion method was applied, leading to soliton solutions with complex spatial structures. In Ref21., Zhao studied the fractional (3 + 1)-dimensional Boussinesq equation, extracting its soliton solutions and analyzing its chaotic behavior. The chaotic characteristics were confirmed through the evolution trends over time and the calculation of Lyapunov exponents. The polynomial method was also employed to derive various solutions, including trigonometric, Jacobi elliptic, and other forms. Silambarasan and Nisar22 analyzed the Eq. (1) and used the Jacobi elliptic function approach to obtain doubly periodic solutions. They demonstrated the degeneration of these solutions into non-topological solitons. Khalid et al.23 explored the (2 + 1) dimensional Boussinesq equation, employing the extended G-expansion method to derive soliton solutions.

Research gap

Despite significant progress in understanding the soliton dynamics within the Boussinesq equation, there is still a notable gap in exploring alternative solutions in this area. A survey of previous research on Eq. (1) reveals that the Hirota bilinear method has not yet been employed to derive multi-solitons. Furthermore, 1st and 2nd order breather waves, along with lump waves, derived using the LWL method, remain unexplored in the existing literature. Moreover, there has been no research conducted on interaction solutions that combine solitons, breather, and lump waves. Although considerable effort has been directed at examining solitary waves under various conditions, no research has examined the intersection or overlap among the two solutions. Investigating this interaction and similarity could offer valuable insight into the system by pinpointing the conditions under which two distinct solutions behave identically, an aspect that serves as the central focus of this research.

Motivation and key contributions

The motivation of this study stems from two factors: (i) the increasing importance of investigating nonlinear wave models such as the Boussinesq-type equations that admit a wide range of localized structures, and (ii) the limitations of existing analytical schemes that are typically restricted to single soliton solutions. Recent contributions have applied several improved analytical techniques, such as the improved modified extended tanh-function method24, the extended mapping approach25, and the Exp-function based schemes26. Likewise, studies employing generalized mapping and related algebraic approaches have been successfully used to construct single-soliton profiles in fractional and higher-dimensional models, including the fractional Klein–Fock–Gordon equation27, stochastic NLSE28 and the Nizhnik-Novikov-Veselov equation29. These works confirm the utility of such methods, but demonstrate that they are primarily tailored for single-soliton solutions.

In contrast, the Hirota bilinear approach adopted in this paper provides a systematic framework to derive not only one-soliton but also general multi-soliton solutions in closed form. This advantage makes it particularly suitable for investigating higher-order nonlinear wave dynamics. Building upon this framework, we further apply the LWL technique to generate first- and second-order lump solutions and the CCA to extract breather solutions. Moreover, we extend the analysis to hybrid interactions involving solitons, lumps, and breathers, which are rarely addressed in the above-mentioned schemes. Finally, the overlapping behavior of distinct solutions is systematically explored through a bidirectional scatter-plot (data mapping) approach, providing an additional diagnostic for identifying regions of similarity in solution structures.

The key contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

-

Derivation of multi-soliton solutions (1-, 2-, 3-, and 4-soliton cases) using the Hirota bilinear method, whereas earlier approaches such as the improved tanh-function, Sardar sub-equation, and Exp-function methods are generally limited to single soliton construction.

-

Construction of first- and second-order lump solutions through the LWL approach, which is more efficient than direct algebraic techniques for higher-order rational solutions.

-

Extraction of breather solutions (first and second orders) by the CCA, which have not been previously reported for this equation.

-

Exploration of hybrid interaction solutions, considering two different scenarios:

-

Case 1: \(\mathbb {N}=3\)

For \(\mathbb {N}=3\), two kinds of interaction solutions are constructed:

-

* (i) 1-soliton with a 1st-order lump,

-

* (ii) 1-soliton with a 1st-order breather.

-

-

Case 2: \(\mathbb {N}=4\)

For \(\mathbb {N}=4\), two types of interaction solutions are obtained:

-

* (i) 2-soliton with a 1st-order lump,

-

* (ii) 2-soliton with a 1st-order breather.

-

-

-

Introduction of a bidirectional scatter-plot (data mapping) framework to examine overlapping behaviors between different solution classes.

Taken together, these contributions extend the scope of existing methods by providing a unified study that incorporates multi-solitons, lumps, breathers, their hybrid interactions, and overlapping behaviors for the specific Boussinesq-type equation introduced in Ref19.. This not only distinguishes our work from earlier studies, but also establishes a comprehensive analytical and comparative framework for future research.

Layout of the paper

The remainder of this manuscript is structured as follows. Sections "Overview of the hirota bilinear method" and "N-Soliton Solutions of Eq. (1)" introduce the Hirota bilinear method and \(\mathbb {N}\)-soliton solutions. Section "Breather solutions of Eq. (1)" investigates the first- and second-order breather waves of Eq. (1). Section "Lump solutions of Eq. (1)" is devoted to lump wave solutions, while Sect. "Interaction dynamics of Eq. (1)" explores four distinct interaction patterns. In Sect. "Physical interpretation of results", the physical interpretations of the obtained results are discussed. Section "Analysis of solution overlaps" highlights the overlaps among different solutions through the bidirectional scatter plot method. Section "Comparative study with existing literature" provides a comparison between the present study and the existing literature. Section "Conclusion" concludes the paper, while Sect. "Future work" outlines potential future research directions. The overall layout of the paper is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Overview of the hirota bilinear method

The Hirota bilinear method is a direct and systematic technique to obtain exact multi-soliton solutions of NLEEs. The central idea is to transform the original PDE into a bilinear form through an appropriate dependent variable transformation, after which perturbation expansions can be systematically applied to generate soliton solutions. Its key steps are as follows:

\({\textbf {Step 1:}}\) Suppose a NLEE is given in the form

Through a dependent variable transformation

where \(\mathbb {K}\) represents a nonzero real constant. Equation (3) is converted into a bilinear form

where Q is a polynomial in the Hirota bilinear operators \(\mathbb {D}_x, \mathbb {D}_y, \mathbb {D}_t, \dots\). Here, \(\Upsilon =\Upsilon (x,y,t)\) is a real-valued function, and \(\mathbb {D}\) refers to Hirota’s bilinear operator, which is defined as

It can also be described as

In this case, p, q, and r are nonnegative integers. The function \(\Upsilon\) is chosen to be a perturbation expansion.

\({\textbf {Step 2:}}\) To construct soliton solutions, a perturbative expansion of the form

is introduced, where \(\varepsilon\) is a small parameter.

\(\bullet\) For the one-soliton case, at the lowest order, we take

which leads to the dispersion relation between \(\beta _1, \gamma _1\) and \(\omega _1\).

\(\bullet\) For the two-soliton case, the form is chosen as

where \(\eta _{12}\) is a constant determined by substituting into the bilinear equation.

\(\bullet\) For the three-soliton case, the construction becomes

\(\bullet\) In general, the \(\mathbb {N}\)-soliton solution can be written as

where \(\zeta _{i}=\beta _i x+\gamma _i y- \omega _i t+\zeta _i^{0}\). Here, \(\alpha _i \in \{0,1\}\) are binary parameters, and the summation is carried out over all possible \(2^{\mathbb {N}}\) combinations of \((\alpha _1,\alpha _2,\dots ,\alpha _\mathbb {N})\). This compact notation is widely used in the bilinear method to represent the exponential structure of the \(\mathbb {N}\)-soliton solution. The coefficients \(\zeta _i\) denote the linear phase variables, while \(\eta _{ij}\) account for pairwise interactions between solitons. The key steps of the proposed method are illustrated in Fig. 2.

\(\mathbb {N}\)-soliton solutions of Eq. (1)

In this part, the \(\mathbb {N}\)-soliton solutions of Eq. (1) will be extracted using the Hirota bilinear technique13. The bilinear form corresponding to Eq. (1) is given by

Here, \(\Upsilon =\Upsilon (x,y,t)\) is a real-valued function, and \(\mathbb {D}\) refers to Hirota’s bilinear operator, which is defined in Eq. (5). The function \(\Upsilon\) is chosen to be a perturbation expansion, which is written as

By substituting Eq. (13) in Eq. (12), the resulting system can be obtained for various powers of \(\varepsilon\).

Here \(\mathbb {B}= \bigg (\mathbb {D}_t^{2}- \mathbb {D}_x^{2}-\delta _2 \mathbb {D}_x^{4}+\frac{\delta _3^2}{4} \mathbb {D}_y^{2}+\delta _3 \mathbb {D}_y \mathbb {D}_t\bigg )\). The \(\mathbb {N}\) soliton solutions of Eq. (1) will be derived using the bilinear method. To find these solutions, define the function \(\Upsilon\) as: To derive the multi-soliton solutions, the following ansatz is employed:

The parameters \(\beta _i, \gamma _i, \zeta _i^{0}\) are arbitrary, while \(\omega _i\) represents the wave velocity. By substituting Eq. (15) in Eq. (14b), the value of \(\omega _i\) can be determined as

Thus, the dispersion variable \(\zeta _i\) can be written as

1-soliton solution

In this subsection, the goal is to obtain the 1-wave soliton solutions. For the case where \(\mathbb {N}=1\), Eq. (13) is simplified as follows:

The phase constant \(\zeta _1^{0}\) includes \(\varepsilon\), allowing the soliton solution for Eq. (12) shown in Fig. 3.

Substitution of Eq. (3) and the auxiliary function from Eq. (19) into Eq. (1) yields the expression for \(\mathbb {K}\):

Substituting Eq. (20) in Eq. (3) yields the 1-wave soliton \(\mathcal {H}_{1s}\) of Eq. (1).

Equation (21) represents the 1-soliton solution of the considered model. For \(\delta _1> 0\), this solution corresponds to a bright soliton, characterized by a localized positive peak on a zero background. In contrast, for \(\delta _1 < 0\), Eq. (21) yields a dark soliton, characterized by a localized dip on a finite background.

2-soliton solution

This section focuses on deriving two-wave solutions. For \(\mathbb {N}=2\), Eq. (13) is simplified by truncating and adding the term \(\Upsilon _2=\eta _{12}e^{\zeta _1+\zeta _2}\), where \(\eta _{12}\) is a coupling constant to be determined.

From Eq. (14c), the following form can be derived:

The coupling constant \(\eta _{12}\) is determined by applying Eqs. (22) and (23):

Since \(\varepsilon\) can be absorbed into \(\zeta _i^{0}\) (\(i=1,2\)), the corresponding solution for Eq. (12) is given by

Substituting Eq. (25) together with Eq. (20) in Eq. (3) yields the 2-wave soliton \(\mathcal {H}_{2s}\) for Eq. (1).

Given that

Here \(\zeta _1, \zeta _2\), and \(\eta _{12}\) are defined in Eqs. (22) and (24). The solution (26) is displayed in Fig. 4. Equation (26) represents the 2-soliton solution of the considered model. The nature of this solution depends on the sign of the parameter \(\delta _1\). For \(\delta _1> 0\), the solution corresponds to a bright 2-soliton, and for \(\delta _1 < 0\), the solution represents a dark 2-soliton.

3-soliton solution

This section focuses on deriving three wave solutions. For \(\mathbb {N}=3\), Eq. (13) is simplified by truncating and adding the term \(\Upsilon _3=\kappa _{123}e^{\zeta _1+\zeta _2+\zeta _3}\), where \(\kappa _{123}\) represents coupling constants that have yet to be determined.

The coupling constants \(\eta _{ij}\) are defined as follows:

From Eq. (14d), the value of \(\kappa _{123}\) can be determined as follows:

Since \(\varepsilon\) can be absorbed into \(\zeta _i^{0}\) (\(i=1,2,3\)), the corresponding solution for Eq. (12) is given by

Inserting Eq. (30) together with Eq. (20) in Eq. (3) yields the 3-wave soliton \(\mathcal {H}_{3s}\) of Eq. (1).

where

Here \(\eta _{12}\), \(\eta _{13}\), \(\eta _{23}\), and \(\kappa _{123}\) are defined in Eqs. (28) and (29). The solution (31) is displayed in Fig. 5. Equation (31) represents the 3-soliton solution of the considered model. The nature of this solution depends on the sign of the parameter \(\delta _1\). For \(\delta _1> 0\), the solution corresponds to a bright 3-soliton, and for \(\delta _1 < 0\), the solution represents a dark 3-soliton.

4-soliton solution

This section focuses on deriving four-wave solutions. For \(\mathbb {N}=4\), Eq. (13) is simplified by truncating and adding the term \(\Upsilon _4=\rho _{1234}e^{\zeta _1+\zeta _2+\zeta _3+\zeta _4}\), where \(\rho _{1234}\) represents coupling constants that have yet to be determined.

The coupling constants \(\eta _{ij}\) are defined as follows:

Here, \(\kappa _{ijk}\) are determined in the same manner as in the 3-soliton case:

From Eq. (14e), the value of \(\rho _{1234}\) can be extracted as follows:

Since \(\varepsilon\) can be absorbed into \(\zeta _i^{0}\) (\(i=1,2,3,4\)), the corresponding solution for Eq. (12) is given by

Inserting Eq. (37) together with Eq. (20) in Eq. (3) yields the 4-wave soliton \(\mathcal {H}_{4s}\) of Eq. (1).

where

Here \(\eta _{ik}\), \(1\le i < k \le 4\), \(\kappa _{123}\), \(\kappa _{124}\), \(\kappa _{134}\), \(\kappa _{234}\), and \(\rho _{1234}\) are defined in Eqs. (34)–(36). The solution (38) is displayed in Fig. 6. Equation (38) represents the 4-soliton solution of the considered model. The nature of this solution depends on the sign of the parameter \(\delta _1\). For \(\delta _1> 0\), the solution corresponds to a bright 4-soliton, and for \(\delta _1 < 0\), the solution represents a dark 4-soliton.

Breather solutions of Eq. (1)

In this section, the CCA is utilized to derive breather solutions from \(\mathbb {N}\)-solitons of Eq. (1) in different planes. The mth-breather solution is obtained by applying this approach to the parameters in Eq. (11).

where \(m\in N, i=1,2,...,\mathbb {N}\). Different forms of the breather waves emerge by assigning specific values to explicit expressions.

1st-order breather waves

To obtain the 1st-order breather solution, the following values are assigned:

By inserting the given values into Eq. (25), \(\Upsilon\) is obtained as

Here, \(\zeta _1^{*}\) represents the complex conjugate of \(\zeta _1\), which is defined in Eq. (22). A detailed examination of the obtained solution reveals two distinct breather patterns, categorized according to their visual features.

-

The first-order \(t\)-periodic bright breather solution is derived using the parameter values: \(\beta _1 = 0.1 - I\), \(\beta _2 = 0.1 + I\), \(\gamma _1 = 0.5 - I\), \(\gamma _2 = 0.5 + I\), \(\delta _1 = \delta _2 = \delta _3 = 1\), \(\mathbb {N} = 2\), and \(\zeta _1^{0} = \zeta _2^{0} = 0\). For \(\delta _1 = -1\), a dark breather solution emerges. This solution shows oscillatory behavior along the \(t\)-axis within the \((y, t)\)-plane, while staying spatially confined in the \(y\)-axis (Fig. 7a).

-

The first-order \(x\)-periodic bright breather solution is derived using the parameter values: \(\beta _1 = 0.1 - I\), \(\beta _2 = 0.1 + I\), \(\gamma _1 = 0.5 - I\), \(\gamma _2 = 0.5 + I\), \(\delta _1 = \delta _2 = \delta _3 = 1\), \(\mathbb {N} = 2\), and \(\zeta _1^{0} = \zeta _2^{0} = 0\). For \(\delta _1 = -1\), a dark breather solution emerges. This solution shows oscillatory behavior along the \(x\)-axis within the \((x,y)\)-plane, while staying spatially confined along the \(y\)-axis (see Fig. 7b).

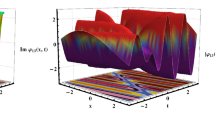

2nd-order breather waves

For \(\mathbb {N}=4\), appropriate parameter selection leads to the derivation of second-order breather solutions. Higher-dimensional breather solutions are expected to display more intricate and impactful dynamic behaviors. The 2nd-order breathers are obtained by setting the parameters as follows:

-

The 2nd-order y-bright and dark breather solutions, obtained with the parameters \(\mathbb {N}=4, \beta _1=0.1-I, \beta _2=0.1+I, \gamma _1=-I, \gamma _2=I, \beta _3=0.2-I, \beta _4=0.2+I, \gamma _3=-2I, \gamma _4=2I, \zeta _1^{0}=\zeta _2^{0}=\zeta _3^{0}=\zeta _4^{0}=0\), form two parallel rows with a periodicity of \(2\pi\) along the y-axis while remaining localized along the x-axis in the (x, y)-plane (see Fig. 8).

Lump solutions of Eq. (1)

This section examines the lump solutions of Eq. (1), a key type of rational solution. Their behavior is analyzed alongside visual representations.

1st-order lump waves

For \(\mathbb {N}=2\) and \(\zeta _1^{0}=\zeta _2^{0}=I\pi\), \(\Upsilon _2\) is given by

Firstly, set the parameters as

in Eq. (11) and taking the limit \(\beta _i\rightarrow 0, (i=1,2)\), the expression for \(\Upsilon\) in Eq. (11) transforms into:

where

By specifying the parameters as

and integrating Eqs. (45) and (46), the first order lump solution of Eq. (1) is obtained as

The first-order lump solution given in Eq. (47) is examined in the (x, y)-plane at different time values. Figure 9a–c display the bright lump profiles at \(t=0\), \(t=2\) and \(t=4\), respectively, while Fig. 9d–f illustrate the corresponding dark lump profiles at the same time levels. At the initial time \(t=0\), the bright lump exhibits a sharp localized peak centered on the (x, y)-plane, whereas the dark lump shows a well-defined localized depression over a constant background. As time progresses to \(t=2\), both bright and dark lumps maintain their spatial localization, with their centers slightly shifted in the plane due to the temporal dependence in Eq. (47). At \(t=4\), bright and dark structures continue to persist without diffusion, demonstrating the robustness of the lump solutions.

The lump profiles evolve with respect to time; however, their localization remains confined to the spatial (x, y)-plane. The temporal parameter governs only the dynamical movement of the structures, while the rational localization characteristic is preserved in both spatial directions. The persistence of these bright and dark lump waves across different time levels reflects their temporal stability and confirms their behavior as spatially localized solutions over a constant background (see Fig. 9).

2nd-order lump waves

For the 2-lump solution, the parameters are set as follows:

then \(\Upsilon _4\) is given as

where \(\chi _i\) and \(\eta _{ij}\) are defined in Eq. (45). By specifying the parameters as

and integrating Eqs. (49) and (48), the 2nd-order lump solution is obtained. Figure 10 illustrates the evolution of second-order lump solutions in the (x, y)-plane at different time levels \(t=0,2,\) and 4. The plots show that the two lump waves move asymptotically and undergo an elastic collision. At \(t=0\), the lumps are initially close, forming a butterfly-shaped structure. As time increases, the waves interact and then gradually separate, preserving their shapes, which highlights the elastic nature of the collision.

Interaction dynamics of Eq. (1)

This section examines four distinct hybrid solutions using the LWL method. Through CCA, interaction solutions are derived that incorporate soliton, breather, and lump waves. MATLAB is utilized to create visual representations, facilitating a detailed analysis of their dynamic properties.

Interaction solutions when \(\mathbb {N}=3\)

A combination of 1-soliton and 1-lump

For \(\mathbb {N}=3\), set \(\zeta _1^{0}=\zeta _2^{0}=\zeta _3^{0}=I\pi\) in Eq. (30) and taking \(\beta _i \rightarrow 0, (i=1,2)\); then \(\Upsilon _3\) can be obtained as

where

Equation (50) is substituted in Eq. (3), followed by the assignment of parameters as

As a result, a hybrid solution in both bright and dark forms is obtained, composed of a 1 soliton and a 1-lump for Eq. (1). From Fig. 11, it is observed that these solutions gradually move toward each other over time. At \(t = 0\) (Fig. 11b and e), the center of the 1st-order lump wave coincides with the soliton. Following their collision, both structures maintain their forms but undergo positional shifts. Specifically, at \(t = 10\) (Fig. 11a and d), the soliton is positioned on the right, whereas at \(t = -10\), it appears on the left (Fig. 11c and f). Despite these positional changes, their forms remain unchanged, confirming that the hybrid solution undergoes an elastic collision.

A combination of 1-soliton and 1-breather

Similarly, by setting particular values for the parameters in Eq. (30) as outlined below:

Insert the function \(\Upsilon _3\) into the Eq. (3), an interaction solution, in both bright and dark forms, consisting of the 1st-order breather and 1-wave soliton, is derived. Initially, at \(t = 0\) (Fig. 12b and e), both solutions overlap at the origin. As time progresses, the soliton shifts position, while maintaining its shape. At \(t = 10\) (Fig. 12a and d), the soliton is positioned on the right side and at \(t = -10\) (Fig. 12c and f), it moves to the left side. Despite these positional changes, the shape of the soliton remains unchanged, confirming the elastic nature of the interaction.

Interaction solutions when \(\mathbb {N}=4\)

A combination of 2-soliton and 1-lump

For \(\mathbb {N} = 4\), we assign \(\zeta _1^{0} = \zeta _2^{0} = \zeta _3^{0} = \zeta _4^{0} = I\pi\) in Eq. (37) and let \(\beta _i \rightarrow 0\), \(( i = 1, 2, 3, 4)\). Consequently, \(\Upsilon _4\) can be written as

where

Inserting Eq. (55) in Eq. (3) and define the parameters as follows:

This results in a hybrid solution in both dark and bright forms, composed of a first-order lump and a 2-soliton for Eq. (1). The interplay of these solutions in the \((x, y)\) plane demonstrates a full collision at \(t = 0\), where the lump and solitons fully overlap, creating a pronounced peak (Fig. 13b and e). As time advances, at \(t = 10\), the soliton starts to move away from the lump in the positional direction, although they continue to interact (Fig. 13a and d). By \(t = -10\) (Fig. 13c and f), the solitons and lump have separated further, the soliton now moving in the negative direction, yet their interaction and shape remain unchanged.

A combination of 2-soliton and 1-breather

In the same way, by assigning particular parametric values in Eq. (37) as

By substituting the function \(\Upsilon _4\) in Eq. (3), an interaction solution, composed of a 1-breather and 2-soliton, is obtained in both bright and dark forms. As shown in Fig. 14, the 1-breather and 2-soliton solutions gradually approach each other over time. At \(t = 0\) (Fig. 14b and e), the center of the 1-breather coincides with the soliton. Following their interaction, at \(t = 4\) and \(t = -4\), both solutions maintain their forms but shift positions in the positive and negative directions with equal amplitudes. These shifts are illustrated in (Fig. 14a and d) for \(t = 4\) and (Fig. 14c and f) for \(t = -4\), confirming that the collision is elastic. Table 1 presents various wave solutions along with their corresponding interaction dynamics.

Physical interpretation of results

In this section, we provide a comprehensive physical interpretation of the obtained solutions, highlighting their qualitative behaviors, interaction properties, and physical importance. The results are discussed sequentially according to the employed analytical techniques: Hirota bilinear method, CCA, the LWL method, and their hybrid interactions. Figures 3 to 14 are explicitly referenced to illustrate the key dynamics.

Hirota bilinear method

Using the Hirota bilinear technique, \(\mathbb {N}\)-soliton solutions of Eq. (1) were constructed.

First-order soliton (Eq. 21). This is a classical exponential solution of \({{\,\textrm{sech}\,}}^2\) type, localized in space. For \(\delta _1> 0\), Eq. (21) gives a bright soliton with a localized positive peak on a zero background. For \(\delta _1 < 0\), it yields a dark soliton, that is, a localized dip on a finite background. The bright and dark cases are shown in Fig. 3a–d, respectively.

Two-soliton solution (Eq. 26). This solution describes the nonlinear superposition of two exponential solitons. Depending on \(\delta _1\), these can be bright–bright, or dark–dark interactions. The collision remains elastic and the solitons recover their original shapes after interaction (Fig. 4).

Higher-order solitons. The three-soliton solution (constructed via Eq. 31) and four-soliton solution (Eq. 38) are likewise exponential solutions of type \({{\,\textrm{sech}\,}}\). Figures 5 and 6 show that even under complex multi-soliton interactions, the collisions are elastic: solitons emerge unchanged apart from phase shifts.

Breather solutions

Applying the CCA, breather solutions are derived. Unlike solitary waves, breathers are periodic in time or space, combining exponential envelopes with oscillatory modulation.

First-order breather This solution represents an exponential soliton pair under conjugate parameters, producing a localized oscillatory structure. Depending on \(\delta _1\), it manifests as a bright breather (pulses on a zero background) or a dark breather (localized dips on a finite background). The periodic time and space breathers are shown in Fig. 7a,b.

Second-order breather Built from higher-order exponential terms, these exhibit two oscillatory rows in parallel (Fig. 8). Such solutions model recurrent energy localization, which is relevant for describing rogue waves and periodic plasma oscillations.

Lump solutions

Applying the LWL reduction leads to rationally localized lump solutions.

First-order lump (Eq. 47). Unlike exponential solitons, this is a rationally decaying solution localized in both x and y. It may appear as a bright lump (positive peak) or dark lump (negative depression), depending on the numerator sign in Eq. (47). Figure 9a–c (bright) and d–f (dark) show the time evolution at \(t=0,2,4\).

Second-order lump Derived by extending Eq. (47), this solution exhibits two interacting lumps. At \(t=0\), they form a butterfly-like pattern, then undergo an elastic collision, preserving their structure after separation (Fig. 10).

Hybrid interactions

Finally, mixed solutions demonstrate the coexistence of different nonlinear excitations.

-

Soliton–lump hybrid. An exponential soliton collides with a rational lump, retaining both structures post-interaction (Fig. 11).

-

Soliton–breather hybrid. The soliton undergoes a positional shift while the breather maintains its oscillation, as in Fig. 12.

-

Two-soliton–one-lump hybrid. Shown in Fig. 13, two exponential solitons interact with a rational lump, all emerging elastically.

-

Two-soliton–one-breather hybrid. Presented in Fig. 14, two exponential solitons and one breather collide elastically, with phase shifts but preserved shapes.

Key insights

The results obtained can be summarized as follows:

-

1.

Bright/dark solitons (Eqs. (21), (26), (31), (38)). Exponential \({{\,\textrm{sech}\,}}^2\)-type solutions, bright for \(\delta _1>0\) and dark for \(\delta _1<0\), with elastic interactions.

-

2.

Breathers (Eq. 42) and higher-order forms). Oscillatory exponential solutions, periodic in t or x, manifesting as bright or dark breathers depending on \(\delta _1\).

-

3.

Lumps (Eq. 47). Rationally localized solutions with algebraic decay; bright or dark, depending on the numerator sign. Elastic interactions are observed in higher-order lumps.

-

4.

Hybrids. Mixed exponential–rational or exponential–oscillatory structures, all demonstrating elastic collisions with preserved identities.

These classifications agree with established soliton taxonomy in nonlinear wave theory30,31, strengthening the physical context of our results. In general, the results reveal that Eq. (1) admits a wide spectrum of nonlinear wave phenomena, each with distinct physical signatures. The ability to obtain soliton, breather, lump, and hybrid solutions underlines the versatility of the system in modeling nonlinear dispersive media.

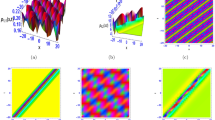

Analysis of solution overlaps

This part presents a detailed comparative analysis of the behaviors of different wave solutions using data points, highlighting their interactions and overlapping features. The purpose is to identify regions in which otherwise distinct solutions exhibit common characteristics, as well as regions in which they diverge.

Two types of solution are considered for this analysis: the Soliton and the Lump. Each solution depends on a specific set of parameters and is evaluated within the designated ranges of the spatial variables \((x,y)\) and the temporal variable \(t\). By systematically varying these coordinates, a collection of data points is generated for each case. The scatter plots then provide a bidirectional comparison, where two solutions are plotted simultaneously with distinct colors. Points in common or overlapping regions indicate that the solutions share similar behavior under specific parameter settings, while separated clusters indicate differences.

-

Solution 1 (bright soliton):

$$\begin{aligned} \mathcal {H}_{1s} = \frac{6 e^{x+y}}{(1 + e^{x+y})^2}, \end{aligned}$$(58)with parameters \(\beta _1 = \gamma _1= \delta _1 = \delta _2 = 1\), \(\delta _3 = 0.2\), and \(t = 2\).

-

Solution 2 (dark soliton):

$$\begin{aligned} \mathcal {H}_{1s} = -\frac{6 e^{x+y}}{(1 + e^{x+y})^2}, \end{aligned}$$(59)with parameters \(\beta _1 = \gamma _1 = \delta _1 = 1\), \(\delta _2 = -1\), \(\delta _3 = 0.2\), and \(t = 2\).

-

Solution 3 (1-Lump):

$$\begin{aligned} \mathcal {H}_{1-Lump} = \frac{-62.9 x^2 + 62.93 y^2 + 190.19}{(2.29 x^2 + 2.29 y^2 + 6.92)^2}, \end{aligned}$$(60)with parameters \(\beta _1 = 0.2 - 1.5I\), \(\beta _2 = 0.2 + 1.5I\), \(\sigma _1 = I\), \(\sigma _2 = -I\), \(\delta _1 = \delta _2 = \delta _3 = 1\), and \(t = 1\).

Spatial variables are varied within the ranges \(x \in [-5, 5]\) and \(y \in [-3, 3]\), while t is fixed according to the solution under study. By evaluating these solutions at discrete values of x, y, data points are generated, which are then compared pairwise in the scatter plots.

The analysis is summarized in Fig. 15, which uses a bidirectional scatter plot technique.

-

Figure 15a: Solution 3 (blue) in Eq. (60) is compared with a second-order Lump (red). Both solutions are evaluated in the (x, y)-plane. For different combinations of x and y, data points are generated that map the behavior of each lump. The results indicate that while the two solutions are distinct, they exhibit strong similarity in the mid-function value range (approximately [0.5, 1.5]), where their data points overlap. This overlap suggests that first- and second-order lumps can produce similar localized structures under specific parameter ranges, while diverging outside this region.

-

Figure 15b: Solution 1 (red) in Eq. (58) is compared to Solution 2 (blue) in Eq. (58). Solution 1 represents a bright soliton, while solution 2 represents a dark soliton. The scatter plot reveals that these two solutions behave as mirror images: the bright soliton has a peak above the baseline, whereas the dark soliton has a trough below it. The overlap occurs only at the origin, confirming that, while their global behaviors are opposite, they retain a localized similarity. This observation highlights the dual nature of soliton solutions where opposite profiles can share a common reference point.

-

Figure 15c: Solution 1 (red, bright soliton) in Eq. (58) is compared to Solution 3 (blue, 1-Lump) in Eq. (60). Here, both the soliton solution and the lump solution are evaluated in the (x, y)-plane. The scatter plot demonstrates that although the two types of solution are structurally different, they exhibit partial overlap in the range [0, 1.5]. This indicates that soliton-type and lump-type solutions can momentarily align in behavior within certain parameter intervals before diverging into their distinct functional forms.

-

Figure 15d: Solution 3 (first-order Lump) is further compared with its bright and dark variants. The scatter plot shows that the bright and dark lumps are symmetric counterparts, much like in the soliton case in Fig. 15b. Their overlap occurs primarily near the origin, where their function values converge. Away from this region, the two lump profiles move in opposite directions, reflecting the bright and dark structures. This localized similarity and global divergence illustrate how lump solutions can bifurcate depending on parameter signs, producing contrasting behaviors that remain correlated at specific points.

Across all subplots, it is observed that the solutions tend to cluster in the middle function value range and near the origin, suggesting that distinct solution types (soliton vs lump, bright vs. dark, first-order vs. higher-order) can share common behaviors in limited regions. As the parameter values or coordinate ranges increase, the solutions begin to diverge, thereby highlighting the transition from correlated to distinct solution behaviors depending on the chosen parameter set.

Comparative study with existing literature

We now compare our results with the work of Wazwaz and Kaur19, who first introduced this form of the Boussinesq equation and examined its soliton structures. While their study focused on integrability and multi-soliton derivations, our work extends the analysis by considering additional solution types and their interactions. The main distinctions are summarized in Table 2.

It should be noted that although various forms of the Boussinesq equation have been studied, the specific form introduced in Ref19. has not previously been investigated in terms of lump, breather, hybrid, or overlap analyses. The present work extends the earlier study by constructing higher-order lumps, breather solutions, and hybrid interactions through the bilinear Hirota framework, and by introducing a bidirectional data-mapping approach to examine overlapping behaviors. These results complement the findings of Ref19. and provide a broader understanding of the solution structures of this equation.

Comparative analysis with recent methods

In addition to the comparison with Wazwaz and Kaur19, our work is also compared to other recent contributions in the field. The summary is provided in Table 3.

Conclusion

This study has explored novel wave solutions and analyzed the complex dynamics of the \((2+1)\)-dimensional Boussinesq equation. By employing the Hirota bilinear approach, explicit \(\mathbb {N}\)-soliton solutions were derived, as demonstrated in Figs. 3–6. Using the CCA, higher-order bright and dark breather waves were constructed, including first-order t-periodic and x-periodic breathers (Fig. 7) and second-order breathers exhibiting more intricate dynamics (Fig. 8).

Lump wave solutions were further obtained through the LWL approach applied to \(\mathbb {N}\)-solitons. Both first- and second-order lumps were explicitly constructed (Figs. 9 and 10), revealing elastic collision phenomena where localized structures interact without loss of identity, though temporarily redistributing energy. For \(\mathbb {N}>2\), the combined use of the LWL method and CCA produced four hybrid classes of solutions, incorporating solitons, lumps, and breathers (Figs. 11 and 14). These hybrid solutions enrich the dynamical spectrum of the model. A complete overview of the solutions is summarized in Table 1.

In addition, a comparative analysis of the soliton and lump waves was performed using a bidirectional scatter plot technique, which enabled quantitative evaluation of similarities across different solution types (Fig. 15). This approach provided a new perspective on nonlinear wave interactions and enhanced the classification of distinct solution behaviors. The methodologies presented here are sufficiently general to be applied to other nonlinear systems, offering a framework for identifying and interpreting complex wave phenomena in higher-dimensional models.

Future work

Several directions can be pursued to extend this research. First, data-driven approaches such as the bilinear neural network framework could be applied to the Boussinesq equation for constructing multi-soliton solutions with enhanced predictive capability. Second, alternative analytical tools, including the generalized logistic approach and the auxiliary equation method, may be explored to uncover additional classes of exact solutions. Third, dynamical systems techniques such as bifurcation and chaos analysis could provide deeper insights into stability, transition, and energy transfer mechanisms.

Moreover, recent studies have begun to address stochastic effects in nonlinear wave models using the IMETFS. For instance, investigations on a (3+1)-dimensional NLSE with cubic–quintic nonlinearity demonstrated how multiplicative noise influences the formation of stochastic solitons of various types, including bright, dark, and singular structures, along with periodic and elliptic solutions35. In another related work, the same analytical framework was applied to a HMGI equation under stochastic perturbations, leading to the construction of diverse exact solutions with direct implications for nonlinear optical wave propagation36. Incorporating such stochastic perspectives and higher-order perturbation terms into the present methodology could provide a more realistic description of soliton dynamics in physical systems.

Finally, extending the methodology to coupled ocean–atmosphere models or validating lump and breather dynamics against experimental or numerical ocean wave data would significantly strengthen the engineering relevance of these findings.

Data availability

All data that support the findings of this study are included within the article.

Abbreviations

- NLEE:

-

Nonlinear evolution equation

- NLM:

-

Nonlinear model

- PDE:

-

Partial differential equation

- NLSE:

-

Nonlinear Schrödinger equation

- CCA:

-

Complex conjugate approach

- LWL:

-

Long-wave limit

- IMETFS:

-

Improved modified extended tanh-function scheme

- GERFM:

-

Generalized exponential rational function method

- HMGI:

-

Higher-order modified Gerdjikov–Ivanov

References

Wu, Q. Research on deep learning image processing technology of second-order partial differential equations. Neural Comput. Appl. 35(3), 2183–2195 (2023).

Gonzalez-Gaxiola, O., Biswas, A., Moraru, L. & Alghamdi, A. A. Solitons in neurosciences by the Laplace-Adomian decomposition scheme. Mathematics 11(5), 1080 (2023).

DiBenedetto, E. & Gianazza, U. Partial Differential Equations (Springer Nature, 2023).

Rudy, S. H., Brunton, S. L., Proctor, J. L. & Kutz, J. N. Data-driven discovery of partial differential equations. Sci. Adv. 3(4), e1602614 (2017).

Yuan, R. R., Shi, Y., Zhao, S. L. & Zhao, J. X. The combined KdV-mKdV equation: Bilinear approach and rational solutions with free multi-parameters. Results Phys. 55, 107188 (2023).

Ganie, A. H., Rahaman, M. S., Aladsani, F. A. & Ullah, M. S. Bifurcation, chaos, and soliton analysis of the Manakov equation. Nonlinear Dyn. 113(9), 9807–9821 (2025).

Ying, L., Li, M. & Shi, Y. New exact solutions and related dynamic behaviors of a (3+ 1)-dimensional generalized Kadomtsev–Petviashvili equation. Nonlinear Dynamics, pp. 1-24 (2024).

Usman, T., Ullah, M. S., Safitri, E. & Ali, M. Z. Soliton outcomes and stability study of the Schrödinger equation with cubic nonlinearity. J. Comput. Nonlinear Dyn. 20(10), 101008 (2025).

Abdalla, M., Roshid, M. M., Ullah, M. S. & Hossain, I. Dynamical analysis, and the effect of fractional parameters on optical soliton solution for Yajima-Oikawa model in short-wave and long-wave. Chaos Solitons Fractals 199, 116697 (2025).

Li, Y., Li, J. & Wang, R. Darboux transformation and soliton solutions for nonlocal Kundu-NLS equation. Nonlinear Dyn. 111(1), 745–751 (2023).

Sucu, N., Ekici, M. & Biswas, A. Stationary optical solitons with nonlinear chromatic dispersion and generalized temporal evolution by extended trial function approach. Chaos Solitons Fractals 147, 110971 (2021).

Ullah, M. S., Ali, M. Z. & Roshid, H. O. Stability analysis, model expansion method, and diverse chaos-detecting tools for the DSKP model. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 13658 (2025).

Kazmi, S. S., Riaz, M. B. & Jhangeer, A. Analyzing N-solitons, breathers, and hybrid interactions: Comparisons of localized wave dynamics through data points. Nonlinear Dyn. 113, 1–30 (2024).

Wang, H., Zhou, Q., Biswas, A. & Liu, W. Localized waves and mixed interaction solutions with dynamical analysis to the Gross-Pitaevskii equation in the Bose-Einstein condensate. Nonlinear Dyn. 106, 841–854 (2021).

Kumar, S., Kumar, A. & Mohan, B. Evolutionary dynamics of solitary wave profiles and abundant analytical solutions to a (3+ 1)-dimensional burgers system in ocean physics and hydrodynamics. J. Ocean Eng. Sci. 8(1), 1–14 (2023).

Wazwaz, A. M. A variety of multiple-soliton solutions for the integrable (4+ 1)-dimensional Fokas equation. Waves Random Complex Media 31(1), 46–56 (2021).

Wu, Y. H., Liu, C., Yang, Z. Y. & Yang, W. L. Breather interaction properties induced by self-steepening and space-time correction. Chin. Phys. Lett. 37(4), 040501 (2020).

Ma, W. X. Lump solutions to the Kadomtsev-Petviashvili equation. Phys. Lett. A 379(36), 1975–1978 (2015).

Wazwaz, A. M. & Kaur, L. New integrable Boussinesq equations of distinct dimensions with diverse variety of soliton solutions. Nonlinear Dyn. 97, 83–94 (2019).

Boussinesq, J. Essai sur la théorie des eaux courantes. Impr. nationale (1877).

Zhao, S. Chaos analysis and traveling wave solutions for fractional (3+ 1)-dimensional Wazwaz Kaur Boussinesq equation with beta derivative. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 23034 (2024).

Silambarasan, R. & Nisar, K. S. Doubly periodic solutions and non-topological solitons of (2+1)-dimension Wazwaz Kaur Boussinesq equation employing Jacobi elliptic function method. Chaos Solitons Fractals 175, 113997 (2023).

Khaliq, S., Ullah, A., Ahmad, S., Akgül, A., Yusuf, A. & Sulaiman, T. A. Some novel analytical solutions of a new extented (2+ 1)-dimensional Boussinesq equation using a novel method. J. Ocean Eng. Sci. (2022).

Hasan, W. M., Ahmed, H. M., Ahmed, A. M., Rezk, H. M. & Rabie, W. B. Exploring highly dispersive optical solitons and modulation instability in nonlinear Schrödinger equations with nonlocal self phase modulation and polarization dispersion. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 27070 (2025).

Mshary, N., Ahmed, H. M. & Rabie, W. B. Fractional solitons in optical twin-core couplers with Kerr law nonlinearity and local m-derivative using modified extended mapping method. Fractal Fract. 8(12), 755 (2024).

Samir, I., Ahmed, H. M., Rabie, W., Abbas, W. & Mostafa, O. Construction optical solitons of generalized nonlinear Schrödinger equation with quintuple power-law nonlinearity using Exp-function, projective Riccati, and new generalized methods. AIMS Math. 10(2), 3392–3407 (2025).

Alam, N., Ullah, M. S., Nofal, T. A., Ahmed, H. M. & Ahmed, K. K. Novel dynamics of the fractional KFG equation through the unified and unified solver schemes with stability and multistability analysis. Nonlinear Eng. 13(1), 20240034 (2024).

Samir, I., Ahmed, K. K., Ahmed, H. M., Emadifar, H. & Rabie, W. B. Extraction of newly soliton wave structure of generalized stochastic NLSE with standard Brownian motion, quintuple power law of nonlinearity and nonlinear chromatic dispersion. Physics Open 21, 100232 (2024).

Alam, N. et al. Bifurcation analysis, chaotic behaviors, and explicit solutions for a fractional two-mode Nizhnik-Novikov-Veselov equation in mathematical physics. AIMS Math. 10(3), 4558–4578 (2025).

Ismail, M. F., Ahmed, H. M. & Rabie, W. B. Construction of exact wave solutions for coupled thermoelasticity theory with temperature dependence using improved modified extended tanh function method. Continuum Mech. Thermodyn. 37(5), 77 (2025).

Hasan, W. M., Rabie, W. B., Ahmed, A. M., Rezk, H. M. & Ahmed, H. M. Construction of new travelling wave solutions and bifurcation analysis for the (2+ 1)-dimensional extended KP-BO equation utilizing the improved modified extended tanh-function method. Int. J. Comput. Math. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207160.2025.2541068 (2025).

Hussein, H. H. et al. Multiple soliton solutions and other travelling wave solutions to new structured (2+ 1)-dimensional integro-partial differential equation using efficient technique. Phys. Scr. 99(10), 105270 (2024).

Murad, M. A. S., Mahmood, S. S., Emadifar, H., Mohammed, W. W. & Ahmed, K. K. Optical soliton solution for dual-mode time-fractional nonlinear Schrödinger equation by generalized exponential rational function method. Results Eng. 27, 105591 (2025).

Hussein, H. H., Ahmed, K. K., Ahmed, H. M., Elsheikh, A. & Alexan, W. Existence of novel analytical soliton solutions in a magneto-electro-elastic annular bar for the longitudinal wave equation. Opt. Quant. Electron. 56(8), 1344 (2024).

Ahmed, K. K. et al. Characterizing stochastic solitons behavior in (3+ 1)-dimensional Schrödinger equation with Cubic-Quintic nonlinearity using improved modified extended tanh-function scheme. Phys. Open 21, 100233 (2024).

Khalifa, A., Ahmed, H. & Ahmed, K. K. Construction of exact solutions for a higher-order stochastic modified Gerdjikov-Ivanov model using the Imetf method. Phys. Scr. https://doi.org/10.1088/1402-4896/ada321 (2024).

Funding

This paper has been produced with the financial support of the European Union under the REFRESH – Research Excellence For Region Sustainability and High-tech Industries project number CZ\(.10.03.01/00/22\_003/0000048\) via the Operational Programme Just Transition.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S.K; methodology, S.S.K, M.B.R; software, S.S.K; validation, S.S.K, M.B.R; formal analysis, S.S.K and M.B.R; investigation, S.S.K, M.B.R; data curation, S.S.K; writing—original draft preparation, S.S.K; writing—review and editing, M.B.R; visualization, S.S.K; supervision, M.B.R; project administration, M.B.R; Funding acquisition, M.B.R.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kazmi, S.S., Riaz, M.B. Comparative analysis of lump, breather, and interaction solutions using a bidirectional data mapping approach. Sci Rep 15, 40242 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24067-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24067-8