Abstract

Chronic wounds are a global burden, which is escalated by diabetes, infections, and antimicrobial resistance. As a result, the combination of traditional herbal remedies with green nanotechnology has gained attention for developing novel and sustainable therapeutic solutions. Despite the promising biological activities of Ehretia rigida (Er), its potential in nanotechnology-driven wound healing remains unexplored. This study investigated the in vitro anti-inflammatory, cytotoxic, and potential wound-healing effects of Er silver nanoparticles (Er-AgNPs). The stability of the Er-AgNPs was tested in various biological media. Anti-inflammatory activity was assessed via inhibition of thermally-induced Bovine serum albumin (BSA) denaturation. Cytotoxicity and wound healing efficacy were evaluated in skin fibroblasts (KMST-6) and keratinocytes (HaCaT) using the Water-Soluble Tetrazolium salt-1 (WST-1) and in vitro scratch assays, respectively. The half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) for protein denaturation was 270.8 µg/ml for Er leaf extract and 532.9 µg/ml for Er-AgNPs, indicating stronger anti-inflammatory properties for the Er leaf extract. Er leaf extract and Er-AgNPs showed negligible cytotoxicity to KMST-6 and HaCat at concentrations < 25 µg/ml. Er-AgNPs promoted wound healing by increasing cell migration and wound closure rates in KMST-6 and HaCaT cells compared to the Er leaf extract alone. In conclusion, this study highlighted the potential of integrating traditional herbal medicine with green nanotechnology to develop innovative and effective solutions for treatment and management, fostering advances in sustainable healthcare.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Wound healing is a natural, intricate, and dynamic process that involves the replacement of damaged and missing tissue layers through the coordinated action of cellular and molecular mechanisms1,2,3. The cellular and molecular signals in the natural wound healing process involve four distinct phases, viz. hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and remodelling3. These phases are driven by the coordinated activities of various specialized cells, such as neutrophils, platelets, fibroblasts, macrophages, and endothelial cells4. In addition, signalling molecules such as cytokines, growth factors, and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) play critical roles in regulating and facilitating these cellular functions throughout the healing process5,6. However, any disruption in these mechanisms can result in impaired healing, excessive inflammation, or chronic wounds. Such conditions present significant clinical challenges, potentially leading to severe infections and increased morbidity and mortality rates3,7. For instance, studies have shown that 1 to 2% of the population in developed countries is affected by chronic wounds during their lifetime7. The economic implications of this issue on the global market have been substantiated by the growing global wound care product market, which is projected to reach $18.7 billion by 20278. Therapeutic strategies often involve the use of absorbent dressings (e.g., films, hydrogels, hydrocolloids, calcium alginates, hydrofibers, and foams), antimicrobial agents (e.g., iodine and silver-based products), anti-inflammatory medications (e.g., diclofenac gel and infliximab), growth factor treatments (e.g., trafermin and becaplermin gel), and techniques such as negative pressure wound therapy to enhance tissue repair1,8. Despite their benefits, these methods have notable limitations. For instance, conventional dressings may not address the underlying cause of chronic wounds, while the use of antimicrobial agents can lead to the development of microbial resistance9. Additionally, systemic therapies, such as growth factor applications, are characterized by limited stability or specificity, highlighting the urgent need for innovative and sustainable advancements in wound care solutions7.

With the advent of nanotechnology, nanomaterials have attracted significant interest in wound healing research due to their active role in promoting skin tissue regeneration10. Nanomaterials at 1–100 nm in at least one dimension provide the benefits of a large surface area-to-volume ratio, improved biocompatibility, enhanced and unique physicochemical properties11. Inorganic or metal-based nanoparticles (NPs) have improved optical, magnetic, and electrical properties. These properties increase their target specificity and drug delivery capabilities, which gives them an added advantage over conventional treatment methods12. More importantly, AgNPs have been highlighted as promising solutions for wound healing, primarily because of their intrinsic antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory capabilities13,14. While a range of methods, including chemical, physical, and biological synthesis, have been established for their synthesis15,16; green synthesis techniques are preferred over conventional methods to avoid the use of hazardous reducing agents and byproducts13. In practice, green synthesis uses natural products from microbes or plant extracts and represents a sustainable and eco-friendly option. Plant extracts are readily available, easy to handle, and a cheap resource compared to the microbial synthesis route. The phytochemicals found in various plant parts, such as roots, leaves, bark, and fruits, reduce the silver ions into AgNPs and also stabilize the NPs, ensuring their stability and functionality13,17.

Plant extract-synthesized AgNPs have several biomedical properties18, of which their antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory effects are crucial in wound healing19. AgNPs synthesized using Rhizophora apiculata leaf extract have demonstrated greater cell migration and wound closure rate compared to the plant extract. These AgNPs exhibited significant anti-inflammatory activity by inhibiting protein denaturation more effectively than the plant extract20. In another study, AgNPs synthesized using the aqueous extract of Ardisia solanacea showed enhanced wound healing capabilities in BJ-5Ta fibroblast cells21. In addition, AgNPs fabricated using Selaginella myosurus inhibited thermally induced protein denaturation, indicating their strong potential as anti-inflammatory and wound healing agents22. These studies and many others highlighted the potential of plant-synthesized AgNPs in the development of innovative wound care therapies.

Since the prehistoric era, the indigenous people of Southern Africa developed deep knowledge and skills necessary to address their medicinal needs through the exploitation of medicinal plants. Ehretia rigida, commonly known as puzzle bush, is a hardy shrub from the Boraginaceae family that is native to South Africa, Botswana, and Namibia, where it is appreciated for its medicinal properties. The herbal concoctions prepared from the leaves, roots, bark, and twigs of this plant are used as traditional medicines to treat a variety of animal and human ailments, including infertility, headache, abdominal pains, chest pains, and skin cuts23,24,25. Our recent study reported the synthesis of AgNPs using Er leaf aqueous extract and their antioxidant and antimicrobial properties26. To further explore the potential of this plant in phytonanotherapy, this study investigated the anti-inflammatory and wound healing effects of Er leaf extract and its phytofabricated AgNPs on normal skin cell lines. Overall, this study has the potential to bridge traditional herbal medicine with green nanotechnology, which could lead to innovative, sustainable, and effective approaches for wound management.

Methodology

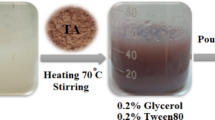

Preparation of Er leaf aqueous extract and Er-AgNPs

The Er leaves with identification number 175/69 were generously provided by the South African National Biodiversity Institute (SANBI) and collected from the Kirstenbosch National Botanical Garden (Cape Town, South Africa). The leaves were thoroughly washed under running tap water, rinsed with distilled water, and oven-dried at 70 °C for 3 days. The Er leaf aqueous extraction and Er-AgNPs synthesis were performed using previously described methods26. Briefly, for the Er-AgNPs synthesis, a 6.25 mg/ml solution of Er leaf aqueous extract was prepared in deionized water (dH2O) and adjusted to pH 11. The solution was then mixed with a 2 mM AgNO3 solution at a ratio of 1:10 and stirred at 750 rpm for 4 h at 50 °C. Characterization of the Er-AgNPs was performed using UV–vis spectrophotometry, dynamic light scattering (DLS), Fourier–transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, and high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HR-TEM).

In vitro stability of Er-AgNPs

The in vitro stability of the Er-AgNPs was performed according to the previous method27, with slight modifications. Er-AgNPs were added to DMEM (Life Technologies, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco; Rockville, MD, USA) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, Mo, USA), 1× DPBS (Sigma-Aldrich), BSA (Sigma-Aldrich), and dH2O, at a ratio of 1:10 in a final volume of 1 ml. The mixtures were incubated at 37 °C. Optical parameters, such as surface plasmon resonance (SPR) peaks and absorbance, were measured using a POLARstar Omega plate reader (BMG-Labtech, Ortenberg, Germany), at 0, 6, 12, 24, and 48 h. Additionally, the particle size distribution and zeta potential were determined using the DLS principle on a Litesizer 500.

Anti-inflammatory activity by BSA denaturation assay

The anti-inflammatory activities of Er leaf extract and Er-AgNPs were determined using the method described by Chahardoli et al.28, with slight modifications. The reaction mixtures consisted of 1% w/v BSA protein separately prepared in Tris-HCl buffer (pH adjusted to 6.5 with 0.1 M HCl), treated with varying concentrations (12.5–400 µg/ml) of Er leaf extract, Er-AgNPs or diclofenac sodium (Sigma-Aldrich). The mixture was first incubated in a water bath at 37 °C for 30 min, and then at 70 °C for 20 min. After cooling to room temperature, the turbidity was measured at 660 nm using the POLARstar Omega plate reader. The control sample consisted of water in place of the treatments. Three independent experiments were performed in triplicate, and the inhibition of BSA denaturation was calculated for the samples using equation (Eq. 1):

Cytotoxicity of Er leaf extract and Er-AgNPs by WST-1 assay

The effects of Er leaf extract and Er-AgNPs were investigated in KMST-6 and HaCaT cells via the WST-1 assay, as previously described29. In brief, the cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin at 37 °C under 5% carbon dioxide and 95% air in a humidified incubator (SL SHEL LAB, Sheldon Manufacturing, Cornelius, OR, USA). For the cell viability assay, the cells were seeded at a density of 1.0 × 105 cells/ml in a 96-well microplate (100 µl/well) and incubated for 24 h. The media was replaced with fresh media containing Er leaf extract or Er-AgNPs at concentrations ranging from 1.56 to 200 µg/ml. Cells treated with 10% DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich) and without treatment were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. The media was removed after 24 h; the cells were then washed twice with Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (1× DPBS). Thereafter, 100 µl of media containing 10% WST-1 Cell Proliferation Reagent (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) was added to each well. The plates were wrapped with foil and incubated at 37 °C for 3 h. The absorbance of the samples was measured at 440 nm and a reference wavelength of 630 nm using a POLARstar Omega plate reader. The percentage of viable cells was calculated via Eq. (2):

Potential wound healing effects of Er leaf extract and Er-AgNPs by scratch assay

Wound healing effects of Er leaf extract and Er-AgNPs on KMST-6 and HaCaT cells were determined using the previously described scratch assay method21. Briefly, KMST-6 and HaCaT cells were seeded in 24-well plates at a density of 2.2 × 105 cells/ml and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. A linear wound was then generated using a sterile 200 µl pipette tip, and the wells were washed with 1× DPBS to remove cellular debris. Thereafter, the cells were treated with 0.00, 1.56, 3.125, or 6.25 µg/ml of Er extract or Er-AgNPs in serum-reduced media (1% FBS). Allantoin (Sigma–Aldrich) was used as the positive control, while cells without treatment were used as the negative control. The degree of wound closure was monitored and photographed using EVOS XL Core Cell Imaging System (Invitrogen, CA, USA) at 10x magnification, at different time intervals (0–48 h) after treatment. The assay was conducted in three replicates. Images were analyzed using ImageJ software v1.54 g (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA), and the percentage of wound closure was determined using Eq. (3):

where W0 = the wound area at 0 h, and Wt = the wound area at ‘t’ hr (calculated at 0, 24, and 48 h).

Statistical analysis

At least three independent experiments were conducted in triplicate, and the data were tested for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Where appropriate, one- or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare different groups. The data comparisons were performed using GraphPad Prism software, version 8.0.1 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). The descriptive data are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) or standard deviation (SD). The differences are considered statistically significant when p < 0.05.

Results and discussion

Physicochemical properties of Er-AgNPs

Er-AgNPs were synthesized using the optimized conditions: 6.25 mg/ml Er leaf extract at pH 11, at a 1:10 ratio with 2 mM AgNO3, 50 °C for 4 h, as described in our previous work26. The Er-AgNPs had a characteristic absorbance peak at 408 nm, a hydrodynamic size of 74.02 ± 0.19 nm, a polydispersity index (PDI) of 0.39 ± 0.05, and a zeta potential of -25.4 ± 6.26 mV. FTIR analysis confirmed the direct involvement of Er biomolecules, such as phenolic compounds, flavonoids, proteins, and saponins, in the reduction of Ag⁺ and stabilization of the Er-AgNPs. HR–TEM showed that the Er-AgNPs were spherical, with core sizes ranging from 6 to 18 nm26.

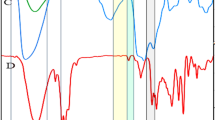

Stability of Er-AgNPs in biological media

Stability is a key parameter that strongly influences the properties and behaviour of colloidal NPs in biological environments. When NPs are stable, their efficacy is improved, and potential side effects are minimized, making them more suitable for use in various biomedical applications30. In this study, the Er-AgNPs were stable in dH₂O (Fig. 1a), as demonstrated by a constant SPR peak at ~ 408 nm throughout the incubation period. This was also accompanied by consistent hydrodynamic diameter (76.12 ± 0.27 to 77.99 ± 0.66 nm) and a moderately negative zeta potential values (–20.86 ± 0.27 to − 24.96 ± 0.08 mV) shown in Fig. 1b, indicating strong colloidal stability. The UV-vis spectra for Er-AgNPs in DPBS (Fig. 1c) suggested that they were also stable. However, Fig. 1d indicated that there were changes in the DLS properties of the Er-AgNPs, where the size of the NPs increased from 54.09 ± 1.78 to 96.63 ± 1.22 nm and zeta potential values decreased from–27.97 ± 1.65 to − 19.50 ± 1.35 mV. This likely implied that the core plasmonic properties of the NPs were stable, but their colloidal stability was gradually declining. Significant changes were observed in the UV-vis spectra and DLS properties of Er-AgNPs in BSA (Figs. 1e, f) and DMEM (Figs. 1g, h). A distinct SPR peak was initially observed around 408 nm in BSA (Fig. 1e), indicating well-dispersed NPs. However, the intensity of the peak steadily decreased over time, accompanied by slight broadening. These changes are attributed to the formation of a protein corona, which may have displaced or masked the Er phytochemicals that could have stabilized the NPs. Furthermore, characteristic reduction in surface charge (–3.56 ± 0.08 to − 1.36 ± 0.12 mV), and an increase in hydrodynamic size (145 ± 7.16 to 184 ± 19.40 nm) were also observed in Fig. 1f. Control samples (media or buffer without Er-AgNPs) did not exhibit any characteristic UV-vis spectra, confirming that the observed spectra in Figs. 1a, c, and e are solely attributable to the presence of Er-AgNPs.

In vitro stability testing of Er-AgNPs in various biological media. Er-AgNPs were incubated for 48 h in ddH2O (a,b), PBS (c,d), BSA (e,f), or DMEM (g,h); and their stability was measured at 6 h intervals between 0 and 24 h, as well as 48 h via UV–vis spectroscopy. Control represents test solutions without Er-AgNPs.

Er-AgNPs incubated in DMEM (Fig. 1g) showed an additional peak around 560 nm, which also appeared in the control, confirming that it originated from components of the medium. Similar to the trend observed in BSA, there was a gradual decrease in the absorption intensity of Er-AgNPs over time. This is likely due to interactions between the NPs and media components such as proteins, amino acids, vitamins, inorganic salts, glucose, and supplements (e.g., FBS and antibiotics). These interactions may have led to the formation of a protein corona that masked the plant-based capping agent, increasing the size. This was further confirmed by the change in its hydrodynamic diameter from 76.89 ± 1.43 to 141.36 ± 5.17 nm (Fig. 1h), while the zeta potential value remained relatively low (–10.86 ± 0.12 to − 10.90 ± 0.13 mV). This phenomenon has been previously reported for green-synthesized NPs incubated in serum-containing media27,29,31.

As illustrated in Table 1, the PDI trends of the Er-AgNPs over the 48-hr incubation period did not demonstrate much variation in various media. In dH₂O, DPBS, and DMEM, PDI values remained below 0.32, indicating narrow size distributions and good dispersion stability. In contrast, BSA exhibited fluctuating and a slight increase in PDI values (0.30–0.36), reflecting a broader particle size distribution. Overall, despite all PDI values remaining below 0.5, the observed decrease in the absorbance peak and lower zeta potential values, particularly in BSA and DMEM, suggested a broader particle size distribution, which is consistent with an increase in protein corona formation in these media over time. This highlighted the significant influence of the surrounding biological milieu on the physicochemical behaviour and surface charge of NPs, which are critical parameters for their performance in biomedical applications.

Anti-inflammatory activity

The in vitro anti-inflammatory activities of Er leaf extract and Er-AgNPs were evaluated using a thermally-induced BSA denaturation assay and compared to the standard anti-inflammatory agent, diclofenac sodium. The results presented in Fig. 2 showed dose-dependent increases in the inhibition of BSA denaturation by all the tested samples. The percentage inhibition by Er leaf extract, Er-AgNPs, and diclofenac sodium at a concentration of 12.5 µg/ml was 24 ± 2.49, 17 ± 0.37, and 37 ± 3.65%, whereas at the highest concentration (400 µg/ml), the percentage inhibitions were 78 ± 0.56, 50 ± 2.01, and 99 ± 0.006%, respectively. The IC50 was 270.8 µg/ml for Er leaf extract, 532.9 µg/ml for the Er-AgNPs, and 56.23 µg/ml for diclofenac sodium. This observation revealed that even though Er-AgNPs had anti-inflammatory activity, the Er leaf extract consistently displayed stronger inhibition. The stronger anti-inflammatory activity of the Er leaf extract may be due to the higher availability of free phytochemicals like flavonoids and tannins, which directly inhibit protein denaturation32. Similarly, a considerable portion of these unbound phytochemicals may have been removed during centrifugation or washing steps of the Er-AgNPs synthesis, leading to loss of their activities33. Furthermore, these compounds may not be involved in the synthesis of Er-AgNPs, reducing their immediate in vitro effect.

The relationship between anti-inflammatory activity and protein denaturation shows the importance of identifying compounds that can modulate inflammatory responses to protect against tissue damage and associated functional impairments34. To this end, previous work has demonstrated that compounds that provide more than 20% inhibition of protein denaturation could be considered potential anti-inflammatory agents35,36. Salve et al.37 synthesized AgNPs using the leaf aqueous extract of Madhuca longifolia and reported that 200 and 400 µg/ml of the NPs produced 23.80 ± 0.41 and 39.48 ± 0.2% inhibition of protein denaturation, respectively. Revathi et al.38 also synthesized AgNPs using an aqueous extract of Dodonaea angustifolia and reported that the leaf extract, AgNPs, and diclofenac sodium had IC50 values of 328.54, 312.45, and 290.45 µg/ml, respectively. Therefore, the observed inhibition of protein denaturation by Er leaf extract and Er-AgNPs is corroborated by these studies and indicates their potential anti-inflammatory activities.

Dose-dependent inhibition of BSA denaturation by Er leaf extract, Er-AgNPs, and diclofenac sodium. Each value presents the mean (n = 6) ± SEM; statistical significance is indicated by # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01, ### p < 0.001and #### p < 0.001for comparison between Er leaf extract and Er-AgNPs, and * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, and **** p < 0.0001 for comparisons between Er leaf extract/Er-AgNPs and standard diclofenac sodium.

Cytotoxic effects of Er leaf extract and Er-AgNPs on normal skin cell lines

The effects of Er leaf extract and Er-AgNPs on the viability of normal skin cells were assessed to evaluate their potential application in biological assays. As shown in Fig. 3a, the viability of KMST-6 cells treated with Er leaf extract (1.56–100 µg/ml) was not significantly different from the untreated cells. The cell viability remained > 85% at all the tested concentrations. These findings indicated that the Er leaf extract had no significant cytotoxic effects on KMST-6 cells. In contrast, concentrations of Er-AgNPs showed biphasic effects on the viability of KMST-6 cells (Fig. 3a), where treatment with Er-AgNPs at 1.56–6.25 µg/ml enhanced cell proliferation, with the percentage of viable cells reaching above 100% and reduced cell viability at concentrations higher than 6.25 µg/ml. Er-AgNPs treatments at 12.5, 25, 50, and 100 µg/ml resulted in viabilities of 73.01 ± 5.98, 62.28 ± 4.26, 61.53 ± 5.69, and 44.23 ± 3.54%, respectively, indicating cytotoxicity. The positive control (10% DMSO) was very toxic to cells, producing 20.80 ± 2.36% cell viability. The calculated IC50 values were > 100 and 67.16 µg/ml for the Er leaf extract and Er-AgNPs, respectively.

Cytotoxic effects of varying concentrations of Er leaf extract and Er-AgNPs on (a) KMST-6, and (b) HaCaT cells. The data are presented as the mean (n = 9) ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA; * p < 0.05, **** p < 0.0001, and ns p ≥ 0.05 for the treatment vs. untreated control.

The results depicted in Fig. 3b demonstrated that treatment of HaCat cells with both Er leaf extract and Er-AgNPs exhibited minimal cytotoxicity at concentrations up to 25 µg/ml, with cell viability remaining above 90%. However, a marked reduction in cell viability was observed when the concentrations exceeded 25 µg/ml for the Er leaf extract and 50 µg/ml for the Er-AgNPs. The treatment with 10% DMSO produced a significant cytotoxicity effect with 3.56 ± 0.54% viable HaCaT cells after 24 h compared to the untreated cells. The IC50 values were > 100 µg/ml for the Er leaf extract and 69.12 µg/ml for the Er-AgNPs. Research has shown that treatment is considered cytotoxic when it can reduce cell viability to ≥ 80%39,40. In the present study, this cytotoxicity threshold was exceeded at concentrations above 6.25 µg/ml for Er-AgNPs in KMST-6 cells, and above 25 µg/ml in HaCaT cells. The observed trend is corroborated by previous studies, which indicated that cytotoxicity of AgNPs in non-cancerous cell lines, such as Chinese Hamster Ovary (epithelial) cells, HaCaT, and KMST-6 cells, was dose-dependent, with a significant impact on cell viability reported at higher concentrations of AgNPs41,42. The non-toxic nature of these treatments to normal human skin cells highlights their potential effectiveness and safety in wound healing43,44.

In vitro wound healing activity

The scratch assay is an in vitro wound healing technique commonly used to study cell proliferation and migration in wound healing processes45. It allows researchers to assess the ability of fibroblasts, keratinocytes, or other cell types to migrate and close a wound area. Previous studies have shown that natural product-derived drugs, such as allantoin, are crucial for regulating fibroblast activity during wound healing46,47. Therefore, using allantoin as a standard in cell migration experiments created a benchmark for comparison47. In this study, allantoin was observed to enhance fibroblast migration into the scratched area in a dose-dependent manner (Figs. 4a and b). However, lower wound closure rates were observed at concentrations above 15 µg/ml. Compared with the untreated control, all the treatments, except for the 50 µg/ml, presented significant increases (p < 0.0001) in cell migration rates (Fig. 4b). Overall, 15 µg/ml was the optimum concentration of allantoin used in the scratch assays, as it resulted in the fastest rate of cell migration and achieved complete wound closure within 48 h.

Evaluation of cell migration by a scratch wound assay in KMST-6 cells treated with various concentrations of allantoin for 0–48 h. (a) Representative images of the scratch wound assay. The yellow lines in the images represent the boundaries of the scratched gap, as evaluated by phase contrast microscopy (magnification × 10). (b) Line graph illustrating the percentage of wound closure over time. The data are presented as means (n = 6) ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical significance was determined by 2-way ANOVA; * p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001, and **** p < 0 0.0001 for the treated vs. untreated control.

Next, the wound healing activities of Er leaf extract and Er-AgNPs were evaluated on KMST-6 cells and compared with those of the positive (allantoin: 15 µg/ml) and negative (untreated: 0 µg/ml) controls. Based on the results shown in Fig. 3, concentrations of 1.56, 3.13, and 6.25 µg/ml were selected for the in vitro scratch assay to further assess their wound healing potential. The results revealed a time-dependent increase in the cell density around the scratched area, restoring the confluency of the cells within 48 h (Fig. 5a). The rate of wound closure was not significantly different (p > 0.05) across all the tested concentrations of Er leaf extract, or at different time points compared with the negative control (Fig. 5b). However, the rate of cell migration was significantly higher in cells treated with allantoin (p < 0.0001) than in those treated with various concentrations of Er leaf extract or the negative control. Treatment with Er-AgNPs enhanced cell migration, leading to faster wound closure compared to both the leaf extract and the untreated control (Fig. 5c). Specifically, when compared with the untreated control, the wound closure rates in the 1.56 µg/ml and 3.13 µg/ml Er-AgNPs groups were significantly higher, with migration rates of 89.77 ± 2.15% and 84.29 ± 3.58%, respectively (Fig. 5d). However, the migration rate was still slightly lower (p < 0.05) than the allantoin-treated cells, which had a 94.72 ± 1.73% wound closure rate after 48 h (Fig. 5b). Overall, while allantoin exhibited the highest wound closure rate, Er-AgNPs demonstrated comparable efficacy, which implied that they could serve as a promising alternative or complementary agent in wound care formulations.

Evaluation of cell migration via a scratch wound assay in KMST-6 cells treated with various concentrations of Er leaf extract or Er-AgNPs and allantoin (15 µg/ml). (a) Representative images of cell migration into the free region following treatment with Er leaf extract. (b) Line graph illustrating the percentage of wound closure over time. (c) Representative images of cell migration into the free region after treatment with Er-AgNPs. (d) Line graph illustrating the percentage of wound closure at the indicated time points. The data are presented as means (n = 9) ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical significance was determined by 2-way ANOVA; * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.005, *** p < 0.001, and **** p < 0.0001 for comparisons between treated and untreated controls.

For the HaCaT cells, the images presented in Fig. 6a clearly show that the treatments, even at the lowest concentration (1.56 µg/ml), revealed an increase in the migration rate compared with the untreated group. The results also revealed a time- and dose-dependent increase in the cell density around the wound area (Fig. 6a). In addition, cell migration was comparable between Er leaf extract (6.25 µg/ml) and allantoin, which had wound closure rates of 93.433 ± 1.52 and 92.69 ± 1.54%, respectively, within 48 h (Fig. 6a). Similar to the KMST-6 cell line, the cells treated with the lowest concentration of Er-AgNPs (1.56 µg/ml) presented the fastest rate of cell migration at the different time points, revealing a wound closure rate of 97.82 ± 0.55% within 48 h. This value was 5% higher than that of allantoin at 93% (Fig. 6b). These findings indicate that Er-AgNPs may be comparable or more effective than allantoin in promoting cell proliferation and migration, which are both critical steps in re-epithelialization during wound healing.

Fibroblasts and keratinocytes are the primary cell types involved in wound closure and are key targets in developing therapeutic interventions. Their proliferation and migration to the wound site are essential for tissue repair and restoration of skin integrity46,48. While plant extracts excel in reducing inflammation, their wound healing ability may be limited by slower release and potential interference with pro-inflammatory responses. AgNPs, however, offer superior antimicrobial activity and tissue regeneration due to their high surface area and membrane-disrupting abilities, making both agents valuable in complementary roles for wound care49. Previous studies have reported on the synthesis of AgNPs from Melia azedarach50, Curcuma longa51, Rhizophora apiculata20, Pluchea indica52, and Cotyledon orbiculata53 and their effects on wound healing. Compared with their respective plant extracts, AgNPs enhanced the migration of both fibroblasts and keratinocytes in scratch wound assays. Therefore, the current findings align with these observations and suggest the potential of Er-AgNPs as effective wound healing agents. In contrast, AgNPs (6.26 µg/ml) biosynthesized from Azadirachta indica did not significantly improve the wound healing rate of lung fibroblasts54. Thus, the results of the current study provide additional scientific evidence supporting the traditional use of Er leaf extract in wound healing23,24,55. Additionally, the rate of wound closure in response to Er leaf extract and Er-AgNPs at lower concentrations further highlighted the efficacy of the experimental treatments in wound healing.

Evaluation of HaCaT cell migration through a scratch wound assay with various concentrations of Er leaf extract and Er-AgNPs treatment for 0, 24, or 48 h using allantoin (15 µg/ml) as the positive control. (a) Representative images of cell migration into the free region with Er leaf extract. (b) Line graph illustrating the percentage of wound closure over time. (c) Representative images of cell migration into the free region after treatment with Er-AgNPs. (d) Line graph illustratings the percentage of wound closure at the indicated time points. The data are presented as means (n = 9) ± standard error of the means (SEM). Statistical significance was determined by 2-way ANOVA; ** p < 0.005, and **** p < 0.0001 for comparisons between treated and untreated controls.

This work provides a strong foundation for the biomedical application of Er-AgNPs by demonstrating their anti-inflammatory activity, cytotoxicity, and potential to accelerate wound closure in human fibroblasts and keratinocytes. The use of two relevant skin cell lines (KMST-6 and HaCaT), along with direct comparisons to the plant extract and allantoin, strengthens the translational value of the in vitro results. However, this study is limited by the lack of mechanistic insights and in vivo validation, as all assessments were conducted in vitro. Although the scratch assay and cytotoxicity studies provide important preliminary data, they do not capture the full complexity of the wound healing process in living organisms. Mechanistic evaluations, such as the use of lipopolysaccharide-induced chronic inflammation models, measurement of inflammatory cytokines, and analysis of gene or protein expression related to re-epithelialization and angiogenesis, were not conducted. Furthermore, the absence of in vivo testing restricts the ability to fully assess the biocompatibility, pharmacodynamics, and therapeutic efficacy of the Er leaf aqueous extract and its AgNPs in a physiological setting.

Conclusion

The Er leaf aqueous extract exhibited stronger anti-inflammatory activity than the Er-AgNPs. While the Er extract did not affect KMST-6 cell viability, Er-AgNPs promoted cell proliferation at concentrations ≤ 6.25 µg/ml, but induced dose-dependent cytotoxicity at higher concentrations. In HaCaT cells, both the Er extract and Er-AgNPs were non-toxic at concentrations below 25 µg/ml. Notably, Er-AgNPs significantly enhanced cell proliferation and migration by accelerating the wound closure when compared to the Er extract in both cell lines. These findings highlighted the promising biomedical potential of combining traditional herbal medicine with green nanotechnology for the development of innovative, sustainable, and effective wound care therapies. Future studies should focus on elucidating the underlying mechanistic pathways, in vivo validation, long-term stability, and in-depth toxicity of the Er-AgNPs, which will be essential for advancing towards clinical application in regenerative medicine and wound care.

Data availability

All data are contained within the article.

References

Tottoli, E. M. et al. Skin wound healing process and new emerging technologies for skin wound care and regeneration. Pharmaceutics 12 (8), 735 (2020).

Wilkinson, H. N. & Hardman, M. J. Wound healing: cellular mechanisms and pathological outcomes. Open. Biology. 10 (9), 200223 (2020).

Yadav, R. et al. Innovative approaches to wound healing: insights into interactive dressings and future directions. J. Mater. Chem. B, (2024).

Fernández-Guarino, M., Hernández-Bule, M. L. & Bacci, S. Cellular and molecular processes in wound healing. Biomedicines 11 (9), 2526 (2023).

Häkkinen, L. et al. Cell and molecular biology of wound healing, in Stem Cell Biology and Tissue Engineering in Dental Sciences. Elsevier. 669–690. (2015).

Peña, O. A. & Martin, P. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of skin wound healing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 1–18. (2024).

Prabhu, A. et al. Transforming wound management: nanomaterials and their clinical impact. Pharmaceutics 15 (5), 1560 (2023).

Kolimi, P. et al. Innovative treatment strategies to accelerate wound healing: trajectory and recent advancements. Cells 11 (15), 2439 (2022).

Yousefian, F. et al. Antimicrobial wound dressings: a concise review for clinicians. Antibiotics 12 (9), 1434 (2023).

Wang, M. et al. Nanomaterials applied in wound healing: Mechanisms, limitations and perspectives. J. Controlled Release. 337, 236–247 (2021).

Kushwaha, A., Goswami, L. & Kim, B. S. Nanomaterial-based Therapy Wound Healing Nanomaterials, 12(4):618. (2022).

Sharda, D., Attri, K. & Choudhury, D. Greener healing: sustainable nanotechnology for advanced wound care. Discover Nano. 19 (1), 1–35 (2024).

Abuzeid, H. M. et al. Green synthesis of nanoparticles and their energy storage, environmental, and biomedical applications. Crystals 13 (11), 1576 (2023).

Paladini, F. & Pollini, M. Antimicrobial silver nanoparticles for wound healing application: progress and future trends. Materials 12 (16), 2540 (2019).

Dhaka, A. et al. A review on biological synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their potential applications. Results Chem. 101108. (2023).

Nguyen, N. P. U. et al. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles: from conventional to ‘modern’methods—a review. Processes 11 (9), 2617 (2023).

Hano, C. & Abbasi, B. H. Plant-based green synthesis of nanoparticles: Production, characterization and applications. Biomolecules 12 (1), 31 (2022).

Simon, S. et al. The antimicrobial activity of biogenic silver nanoparticles synthesized from extracts of red and green European Pear cultivars. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 49 (1), 613–624 (2021).

Oselusi, S. O. et al. Phytonanotherapeutic Applications of Plant Extract-Synthesized Silver Nanoparticles in Wound Healing—a Prospective Overview. BioNanoScience 1–21 (2024).

Alsareii, S. A. et al. Synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from rhizophora apiculata and studies on their wound healing, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and cytotoxic activity. Molecules 27 (19), 6306 (2022).

Mohanta, Y. K. et al. Phyto-assisted synthesis of bio‐functionalised silver nanoparticles and their potential anti‐oxidant, anti‐microbial and wound healing activities. IET Nanobiotechnol. 11 (8), 1027–1034 (2017).

Kedi, P. B. E. et al. Eco-friendly synthesis, characterization, in vitro and in vivo anti-inflammatory activity of silver nanoparticle-mediated selaginella myosurus aqueous extract. Int. J. Nanomed. 8537–8548. (2018).

Maroyi, A. A systematic review on biological and medicinal properties of ehretia rigida (Thunb.) Druce (Ehretiaceae) in Southern Africa. Plant. Sci. Today. 10 (sp2), 74–82 (2023).

Ndhlovu, P. et al. Plant species used for cosmetic and cosmeceutical purposes by the Vhavenda women in Vhembe district Municipality, Limpopo, South Africa. South. Afr. J. Bot. 122, 422–431 (2019).

Jiang, S. et al. Ehretia genus: a comprehensive review of its botany, ethnomedicinal values, phytochemistry, pharmacology, toxicology and clinical studies. Front. Pharmacol. 16, 1526359 (2025).

Oselusi, S. O. et al. Phytofabrication of silver nanoparticles using ehretia rigida leaf aqueous extract, their characterization, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities. Mater. Today Sustain. 29, 101059 (2025).

Salazar, L. et al. Biological effect of organically coated Grias neuberthii and persea Americana silver nanoparticles on HeLa and MCF-7 cancer cell lines. J. Nanatechnol. 2018 (1), 9689131 (2018).

Chahardoli, A. et al. Galbanic acid, a sesquiterpene coumarin as a novel candidate for the biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles: in vitro hemocompatibility, antiproliferative, antibacterial, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory properties. Adv. Powder Technol. 34 (1), 103928 (2023).

Sharma, J. R. et al. Anticancer and drug-sensitizing activities of gold nanoparticles synthesized from cyclopia Genistoides (honeybush) extracts. Appl. Sci. 13 (6), 3973 (2023).

Guerrini, L., Alvarez-Puebla, R. A. & Pazos-Perez, N. Surface modifications of nanoparticles for stability in biological fluids. Materials 11 (7), 1154 (2018).

Barbalinardo, M. et al. Protein Corona mediated uptake and cytotoxicity of silver nanoparticles in mouse embryonic fibroblast. Small 14 (34), 1801219 (2018).

Eker, F. et al. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using plant extracts: A comprehensive review of physicochemical properties and multifunctional applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 26 (13), 6222 (2025).

Rónavári, A. et al. Biological activity of green-synthesized silver nanoparticles depends on the applied natural extracts: a comprehensive study. Int. J. Nanomed., 2017, 871–883 .

Mustafa, A. et al. Anti-inflammatory activity of lauric acid, thiocolchicoside and thiocolchicoside-lauric acid formulation. Bioinformation 19 (11), 1075 (2023).

Fatahillah, R., Fitriyani, D. & Wijayanti, F. Vitro anti-inflammatory activity of extract and fraction seed coat Kebiul (Caesalpinia Bonduc L). Al-Kimia 10 (1), 42–50 (2022).

Gondkar, A. S., Deshmukh, V. K. & Chaudhari, S. R. Synthesis, characterization and in-vitro anti-inflammatory activity of some substituted 1, 2, 3, 4 tetrahydropyrimidine derivatives. Drug Invent. Today 5(3), 175–181 (2013).

Salve, P. et al. An evaluation of antimicrobial, anticancer, anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities of silver nanoparticles synthesized from leaf extract of Madhuca longifolia utilizing quantitative and qualitative methods. Molecules 27 (19), 6404 (2022).

Revathi, N. & Dhanaraj, T. A study on in vitro anti-inflammatory activity of silver nanoparticles synthesized from Dodonaea angustifolia leaf extract. J. Pharmacognosy Phytochemistry. 8 (4), 1878–1881 (2019).

Araujo, L. A. et al. Evaluation of the Antioxidant, photoprotective and wound healing capacity of Guazuma ulmifolia lam. Extracts in L-929 cells exposed to UV-A and UV-B irradiation. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 35 (3), e–20230149 (2024).

Morakul, B. et al. Cannabidiol-loaded nanostructured lipid carriers (NLCs) for dermal delivery: enhancement of photostability, cell viability, and anti-inflammatory activity. Pharmaceutics 15 (2), 537 (2023).

Tyavambiza, C. et al. The cytotoxicity of cotyledon orbiculata aqueous extract and the biogenic silver nanoparticles derived from the extract. Curr. Issues. Mol. Biol. 45 (12), 10109–10120 (2023).

Paknejadi, M. et al. Concentration-and time-dependent cytotoxicity of silver nanoparticles on normal human skin fibroblast cell line. Iran. Red Crescent Med. J. 20 (10), 1–8 (2018).

Ortega-Llamas, L. et al. Cytotoxicity and wound closure evaluation in skin cell lines after treatment with common antiseptics for clinical use. Cells 11 (9), 1395 (2022).

Shalaby, M. A., Anwar, M. M. & Saeed, H. Nanomaterials for application in wound healing: current state-of-the-art and future perspectives. J. Polym. Res. 29 (3), 91 (2022).

Liang, C. C., Park, A. Y. & Guan, J. L. In vitro scratch assay: a convenient and inexpensive method for analysis of cell migration in vitro. Nat. Protoc. 2(2), 329–333 (2007).

Juszczak, A. M. et al. Wound healing properties of Jasione Montana extracts and their main secondary metabolites. Front. Pharmacol. 13, 894233 (2022).

Nezhad-Mokhtari, P. et al. Engineered bioadhesive Self-Healing nanocomposite hydrogel to fight infection and accelerate cutaneous wound healing. Chem. Eng. J. 489, 150992 (2024).

Muniandy, K. et al. In Vitro Wound Healing Potential of Stem Extract of Alternanthera Sessilis Vol. 2018, 3142073 (Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2018). 1.

Nandhini, J., Karthikeyan, E. & Rajeshkumar, S. Nanomaterials for wound healing: current status and futuristic frontier. Biomedical Technol. 6, 26–45 (2024).

Chinnasamy, G., Chandrasekharan, S. & Bhatnagar, S. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles from melia azedarach: enhancement of antibacterial, wound healing, antidiabetic and antioxidant activities. Int. J. Nanomed., :9823–9836. (2019).

Maghimaa, M. & Alharbi, S. A. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from curcuma longa L. and coating on the cotton fabrics for antimicrobial applications and wound healing activity. J. Photochem. Photobiol., B. 204, 111806 (2020).

Chiangnoon, R. et al. Phytochemical analysis, antioxidant, and wound healing activity of pluchea indica L.(Less) branch extract nanoparticles. Molecules 27 (3), 635 (2022).

Tyavambiza, C. et al. The antioxidant and in vitro wound healing activity of cotyledon orbiculata aqueous extract and the synthesized biogenic silver nanoparticles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23 (24), 16094 (2022).

Dutt, Y. et al. Silver nanoparticles phytofabricated through Azadirachta indica: anticancer, apoptotic, and wound-healing properties. Antibiotics 12 (1), 121 (2023).

Fisher, F. et al. South African medicinal plants traditionally used for wound treatment: an ethnobotanical systematic review. Plants 14 (5), 818 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The author SOO extends his appreciation to the South African National Research Foundation (NRF) for his Doctoral Scholarship Award (Reference: MND210616612113). The authors also acknowledge the DSI/Mintek NIC Biolabels Research Node for financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: SOO., and AMM. Methodology and formal analysis: SOO., NRSS., MM., and AMM. Writing-original draft preparation: SOO. Writing- review and editing: NRSS., MM., and AMM. Supervision: AMM., and NRSS. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Oselusi, S.O., Sibuyi, N.R.S., Meyer, M. et al. Anti-inflammatory, cytotoxic, and potential wound healing effects of phytofabricated Ehretia rigida leaf aqueous extract-synthesized silver nanoparticles. Sci Rep 15, 40301 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24111-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24111-7