Abstract

This paper introduces a dual-objective control framework for standalone photovoltaic (PV) systems that uniquely integrates maximum power point tracking (MPPT) with precise DC load voltage regulation. Unlike existing approaches that concentrate almost exclusively on power optimization, the proposed system simultaneously ensures both efficient energy harvesting and robust output voltage stability under fluctuating climatic and load conditions. The novelty lies in the design of a reference voltage estimator (RVE)—a sensorless MPPT mechanism that fuses explicit irradiance estimation with a radial basis function neural network—combined with two Lyapunov-based nonlinear controllers supervising a two-stage Boost–Buck converter architecture. This coordinated design enables accurate real-time MPP prediction, finite-time load-side voltage stabilization, and decoupled handling of PV-side and load-side dynamics. The system is implemented through microcontroller-in-the-loop experimentation and validated under diverse and extreme disturbances. Results demonstrate exceptionally low mean absolute errors (0.1253 V for MPPT and 0.0793 V for load regulation) with rapid recovery times (< 3 ms), confirming superior efficiency, reliability, and resilience. This work bridges a critical research gap by experimentally proving that stable voltage regulation can be unified with optimal power harvesting in a single architecture, offering a deployable solution for standalone PV systems in real-world conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction and literature review

The urgent necessity of a rapid transition to environmentally friendly energy sources cannot be overstated; it is the most practical and sustainable approach to ensuring a dependable energy future while concurrently addressing the pressing global climate concerns. Renewable energy sources are implemented to significantly reduce dependence on fossil fuels, thereby reducing greenhouse gas emissions and facilitating the transition to a more sustainable globe. Not only does this transition ensure energy security and resilience, but it also contributes to the realization of global climate objectives, the preservation of ecosystems, and the development of a more sustainable planet for future generations. A renewable energy source that is considered to be particularly robust is solar photovoltaic (PV). The solar PV technology is one of the most thrilling and rapidly expanding in the renewable energy industry. As a result of significant technological advancements1,2, the cost of solar PV systems has been on a steady decline, rendering them increasingly affordable and accessible. This price reduction has facilitated the widespread adoption of solar PV throughout the world. Over the past decade, solar PV has outpaced all other power-generation technologies in terms of installed capacity. As exemplification, latest data from the international renewable energy agency, IRENA (2024), reveals that the global cumulative capacity of solar PV installations surpassed 1418 GW by the end of 2023, cementing its position as a leading force in the renewable energy landscape3. This remarkable growth underscores the transformative potential of solar PV in the transition to a cleaner, more sustainable energy future. Experts strongly argue that, with continued technological advancements and policy support, solar PV has the potential to become the world’s dominant energy source in the coming years4.

Despite the prominence of solar PV energy, there are still several prevailing concerns with its implementation, ranging from the conversion efficiency of a solar cell to the operational efficiency of a PV-connected system. Over the last few years, renewable energy research has been characterized by a perpetual evolving endeavor to enhance the conversion efficiency of the solar cell. In this pursuit, engineers and scientists worldwide are motivated by the objective of optimizing the quantity of sunlight that a solar cell can convert into electrical energy. They investigate innovative solutions, such as the development of multi-junction cells that capture a broader spectrum of sunlight5,6 and the use of cutting-edge materials such as perovskites, which are recognized for their exceptional efficiency potential7. Beyond conversion efficiency, the operation of a PV module in a connected setup, such as a standalone setup, introduces several challenges. One significant issue is that the system may not perform optimally, often due to mismatches in energy delivery and voltage instability from the load side. These constraints arise from factors like the variability of environmental conditions and load demands, which can have a tremendous effect on power delivery and the complexity related to controlling the PV side as well as the load. As a result, the system might fail to deliver the expected performance, compromising both energy efficiency and operational reliability. The issue related to energy mismatch has been intensively pursued under the umbrella of maximum power point tracking (MPPT)8,9,10. Over the last few years, several approaches to MPPT have been understudied. Each MPPT method is unique, has its own specific advantages and limitations, and differs from the others in terms of complexity, number of sensors, and overall performance11. Among the several approaches, the fractional methods such as fractional open circuit, fractional short circuit and pilot cells methods factor out as the most simplest12. However, they encounter several challenges which hinders their efficacy, including their approximate and extreme nature. Alternative algorithms include the perturb and observe (P&O), incremental conductance (INC) which have been extensively investigated13,14,15. These two algorithms are considered as the classical MPPT methods. Several challenges have been identified in the extensive research conducted on classical algorithms. One of these challenges is the trade-off between response speed and steady-state oscillations, which reduces overall efficiency. Under abruptly altering climatic conditions, their performance also suffers. In recent years, there has been a strong emphasis on the development of methods to address these limitations. Many of these methods are either inspired by or built upon P&O/INC, which underscores their foundational role in the field of MPPT.

Table 1 offers a concise summary of the pertinent research in the field of MPPT for PV systems, emphasizing both the most recent developments and the existing constraints. The intense emphasis on MPPT as a critical issue in PV systems is a significant observation from these works. A variety of control strategies and configurations are proposed by numerous authors to address the challenges presented by PV systems under dynamic environmental conditions. These contributions comprise a diverse array of techniques, including variant of the INC and P&O algorithms, such as variable step size INC and P&O methods. Fractional open-circuit voltage and short-circuit current methods, linear interpolation techniques, traditional linear control strategies such as the PI controller, and advanced nonlinear control methods such as sliding mode and backstepping controllers are additional approaches. Further, optimization algorithms (e.g., Particle Swarm Optimization, Genetic Algorithms) and artificial intelligence (AI) techniques (e.g., fuzzy logic and artificial neural networks) have been increasingly implemented to improve the accuracy and efficiency of MPPT in a variety of operating environments. Collectively, these contributions represent substantial advancements in the field, particularly in the enhancement of the responsiveness and dependability of MPPT solutions.

Other contributions to MPPT in standalone PV systems are outlined in high-quality studies that offer valuable insights into both algorithmic innovation and performance metrics.

In16, the authors developed a hybrid MPPT technique combining Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) with neural networks for standalone PV systems. The method achieved high power extraction accuracy and minimized convergence time under fluctuating conditions. The study emphasized MPPT efficiency and RMS-based tracking performance as primary evaluation criteria. In17, an intelligent fuzzy particle swarm optimization was used to dynamically adjust MPPT operating points. The system demonstrated improved response speed and power stability over conventional methods, particularly under non-uniform irradiance. In18, a single-stage hybrid photovoltaic (PV)-fuel cell (FC)-based grid-integrated system with Lyapunov function-based controller was designed to obtain optimal power extraction from hybrid renewable sources without maximum power point tracking (MPPT) application. In19, the authors proposed a hybrid whale optimization algorithm differential evolution (WOADE) as a maximum power point tracking (MPPT) for wind energy conversion systems (WECS) employed for water pumping applications. The control strategy provides rapid and zero oscillation power tracking to achieve the global maximum power point within a limited number of iterations. In20, the authors introduced an improved differential evolution particle swarm optimization (IDEPSO) established photovoltaic (PV) maximum power point tracker (MPPT) for water pumping applications.

In spite of the extensive research and optimization of MPPT, the current literature still contains a critical gap: other equally significant aspects of standalone PV systems have not been adequately addressed. In particular, the stochastic nature of environmental conditions has resulted in underexplored issues regarding voltage instability. The voltage output of a PV system is inherently variable due to fluctuations in temperature and irradiance, making it equally important to maintain stability as it is to optimize power through MPPT. In reality, MPPT guarantees that the system operates at its optimal power point; however, it does not inherently resolve the issue of voltage regulation at the output. When the system is subjected to coupling with other electrical systems or during direct exploitation by the load, this lack of voltage control can result in significant instability. The load may be adversely affected by the absence of sufficient voltage quality control, which can lead to voltage fluctuations, surges, or declines that may diminish the efficacy and lifespan of connected devices. The current corpus of research has primarily concentrated on maximizing power extraction, despite these challenges, without addressing the equally critical need for stable and reliable voltage output. The issue of voltage instability, particularly in the context of standalone PV systems, is largely overlooked, as demonstrated in Table 1. Consequently, in order to guarantee both power optimization and system stability, it is of utmost importance to prioritize the integration of voltage control mechanisms in conjunction with MPPT solutions, thereby resolving a critical void in the current state-of-the-art research.

Motivation

The impetus for this paper is the increasing dependence on standalone PV systems as a critical solution for sustainable energy generation, particularly in regions with restricted or nonexistent access to conventional grid infrastructure. These systems provide a promising alternative to conventional energy sources, thereby promoting energy independence and supporting the global transition to sustainable energy. Nevertheless, the extensive research and optimization of MPPT to enhance power extraction from PV systems have frequently resulted in the neglect of other equally critical aspects of system performance, particularly voltage stability. Voltage instability continues to be a persistent challenge in standalone PV systems. The system’s capacity to provide consistent and reliable power to connected applications can be compromised by these fluctuations, which can result in unpredictable voltage shifts. This problem has the potential to limit the overall efficacy and viability of the PV system by reducing the lifespan of sensitive equipment connected to it, in addition to affecting system efficiency. This emphasizes the necessity of a more comprehensive control strategy that not only optimizes power output through MPPT but also guarantees consistent and dependable voltage delivery to the load. The necessity of addressing the frequently disregarded issue of voltage regulation in standalone PV systems is the pivotal impetus for our research. Our objective is to offer a solution that bridges the gap between power optimization and voltage stability by concentrating on this critical yet underexplored area. This will guarantee that standalone PV systems can operate efficiently and reliably under a variety of environmental conditions.

Proposed solution and contribution

This paper introduces a novel, comprehensive control strategy that is intended to resolve the discerned limitations in previous studies. The strategy is designed to ensure that the voltage delivery to the load is stable and reliable, as well as to maximize power extraction from PV panel through advanced MPPT techniques. Unlike much of the current state-of-the-art research, which focuses primarily on power optimization, this work sets a dual objective: (1) ensuring robust and efficient energy extraction from the PV array, and (2) achieving precise, finite-time regulation of the DC load voltage. We establish resilient nonlinear controllers that supervise a two-stage converter system, which comprises Buck and Boost converters, in order to achieve these objectives. We present a novel Reference Voltage Estimator (RVE) that is integrated into an innovative MPPT solution to accurately predict the maximum power point (MPP) voltage for the first objective. This MPP voltage is subsequently utilized by a Lyapunov-based nonlinear controller to guarantee that the standalone system consistently operates at the optimal MPP, even in dynamic environmental conditions, facilitated by the Boost converter. The Buck converter is simultaneously managed by an additional Lyapunov nonlinear controller to ensure that the voltage at the output side is precisely regulated. A microcontroller-in-the-loop (MIL) experimental framework is used to implement the entire system, which enables practical real-time feedback and control. Under a variety of uncertain climatic and load conditions, a series of rigorous experiments were conducted to assess the MPPT performance and output voltage stability. The findings indicate that the proposed control strategy effectively accomplishes the dual objectives of improving the efficiency, reliability, and overall performance of standalone PV systems by maximizing power output and ensuring constant voltage delivery. This work contributes meaningfully to the field by offering a more holistic solution to the critical issues of both power optimization and voltage stability in PV systems. The key novelties and contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

-

1.

Dual-objective control framework: Simultaneous resolution of two critical problems—Maximum Power Point Tracking (MPPT) and precise DC load voltage regulation—in standalone PV systems.

-

2.

Novel reference voltage estimator (RVE): A sensorless MPPT mechanism that combines an explicit irradiance estimator and a radial basis function (RBF) neural network to accurately predict the MPP voltage using only electrical measurements.

-

3.

Nonlinear Lyapunov-based controllers: Two robust controllers are designed to coordinate a dual-stage DC-DC converter topology (Boost + Buck), ensuring both optimal power extraction and fast, stable output voltage regulation.

-

4.

Real-time implementation: The system is fully validated through Microcontroller-in-the-Loop (MIL) experimentation, highlighting practical viability and deployment readiness.

-

5.

Comprehensive experimental validation: Extensive testing under realistic and extreme operating conditions, including abrupt changes in irradiance, temperature, reference voltage, and load uncertainties.

-

6.

Bridging a major research gap: Unlike most state-of-the-art studies (see Table 1), which focus solely on MPPT, this work offers a holistic, experimentally proven solution that unifies MPPT with load-side voltage regulation in a single control architecture.

Unlike prior works that primarily optimize MPPT while leaving load-side stability as a secondary concern, this paper presents a holistic two-stage control strategy that unifies maximum power extraction with finite-time DC voltage regulation. The originality lies in three aspects: (i) a sensorless Reference Voltage Estimator (RVE) that eliminates costly irradiance sensors while achieving high MPP prediction accuracy, (ii) the coordination of dual Lyapunov-based nonlinear controllers across Boost and Buck converters to achieve decoupled yet synchronized PV-side and load-side objectives, and (iii) the first microcontroller-in-the-loop experimental validation of such an integrated dual-objective PV control scheme. This contribution directly addresses the overlooked challenge of voltage instability in standalone PV systems and establishes a deployable framework that surpasses the capabilities of existing single-focus MPPT systems.

The rest of this paper is outlines as follows: In Section “General description of the system studied and proposed comprehensive control strategy”, a general description of the system under study is prescribed- Section “Reference voltage estimator (RVE) design”, presents the proposed RVE- Section “Nonlinear controller design” the nonlinear controllers’ design- Section “Overall system implementation and MIL setup” is dedicated to the MIL implementation- Section “Experimental results and discussion” presents the results of investigations while Sect “Conclusion” concludes the paper.

General description of the system studied and proposed comprehensive control strategy

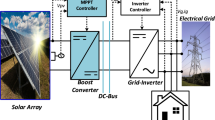

This section interns to provide a general description of the system understudied. It is also aimed at briefly delineating the comprehensive control strategy proposed in this paper. The general structure of the standalone PV system understudy is prescribed in Fig. 1. It consists of a PV panel connected to a load via two DC-DC converters, namely the Boost and Buck converter. Since the former is directly linked to the PV, it allows for control of the power delivered by the PV. While the latter converter, connected to the load, allows for control of the final output. These two converters thus allow to pursue two objectives delineated as follows:

Objective-1: Ensuring robust and efficient energy extraction from the PV array.

Objective-2: Achieving precise, finite-time regulation of the DC load voltage.

Advanced mathematical modeling and nonlinear control techniques are integrated in a synergistic manner to achieve these objectives. On the photovoltaic (PV) side of the autonomous system, a novel Reference Voltage Estimator (RVE) is essential for the precise estimation of the maximum power point (MPP) voltage of the system, denoted as φ. This anticipated MPP voltage is subsequently employed by a nonlinear controller, which directs the PV system to operate at its optimal power point. A neural network model and an explicit irradiance estimator are integrated into the RVE to generate real-time irradiance estimates, which are denoted as \(\:\widehat{G}\). The irradiance estimator is based on the mathematical relationship \(\:F({I}_{pv},\:{V}_{pv},\:T)\), V, where PV current, voltage, and temperature are used as inputs to generate accurate irradiance estimates. The neural network subsequently processes these estimates to approximate the MPP voltage. The proposed RVE system’s primary benefit is its reliance on straightforward, cost-effective measurements of PV current, voltage, and temperature, which eliminates the necessity for expensive irradiance sensors. This RVE accomplishes substantial success by operating independently of such measurements, in contrast to existing MPPT controllers that significantly rely on expensive and intricate irradiance measurement systems. The RVE is a highly innovative and practical contribution to the field of PV system optimization due to its independence. The central coordinator on the PV side, the nonlinear controller-1, is responsible for guiding the system to the MPP voltage, thereby guaranteeing the most efficient energy extraction from the PV array. The MPPT mechanism proposed in this study is fundamentally composed of the RVE and the nonlinear controller-1.

In order to regulate the output voltage of the system, a second nonlinear controller (Nonlinear controller-2) is configured on the load side. Its primary objective is to preserve the output voltage at a predetermined set point, as denoted by Ω, in the face of stochastic fluctuations in environmental conditions, including changes in irradiance (G) and temperature (T), as well as the nonlinear dynamics of the Boost converter. It should be noted that the set point voltage may not always be consistent, as it is contingent upon the given application. The control problem may be further complicated by the fact that the load may experience uncertainties or disturbances. The output voltage of the nonlinear controller-2 is intended to be stable and consistent with the reference voltage, regardless of the presence of external load disturbances and uncertainties. Essentially, this controller is expected to guarantee that the system is capable of sustaining voltage regulation under a variety of operating conditions, thereby improving the overall stability and efficiency of the standalone PV system and delivering dependable performance. In the subsequent discourse, we will provide details into the various subsystems.

Reference voltage estimator (RVE) design

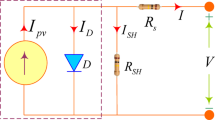

This section is aimed at presenting the design of the RVE proposed in this paper. The RVE is responsible for approximating the MPP voltage by harnessing real time measurements of the PV voltage, current and Temperature. As illustrated in Fig. 1, the RVE employs an explicit irradiance estimator and a NN model. The estimator will be derived by mathematical manipulation of the nonlinear equations of the PV panel model. We resort to the single diode model (SDM) for its good balance between accuracy and complexity38,39. Additionally, it can allow us to formulate an explicit approximator of irradiance. The mathematical equation of a SDM is presented in Eq. (1). Note that the PV modelling equivalent circuit is found in Appendix A, Fig A.

Where \(\:a=n{N}_{s}{K}_{B}T/q\). The terms \(\:{I}_{ph}\),\(\:\:{I}_{s}\) are respectively the photocurrent and the saturation current of the diode. Additionally, \(\:n\) is the diode ideality factor, \({N}_{s}\) is the number of cells, \(\:k\) is the Boltzmann’s constant having the value\(\:1.381\times\:{10}^{-23}\text{J}/\text{K}\), \(\:q\) is the charge constant \(\:q=1.602\times\:{10}^{-19}C\), and \(\:T\) is the temperature of the cell in kelvin. Additionally, the term, \(\:{I}_{ph}\), can be obtained as :

Where G is the actual incident solar irradiance in \(\text{W}/\text{m}^{2}\), \(\:{I}_{ph-ref}\)is the photocurrent at standard test conditions (STC) i.e. \(\:1000\,\text{W}/\text{m}^{2}\) and \(\:25\,^{\circ}\text{C}\), \(\:{K}_{i}\) is the temperature coefficient of short circuit current, \(\:{E}_{g}\) is the band-gap energy which has the reference value \(\:{E}_{g,ref}=1.12\:eV\) for silicon material. Additionally, the variation of the shunt resistance with irradiance G can be modeled mathematically as:

Where \(\:{R}_{p,ref}\) is the shunt resistance at STC, and \(\:{R}_{p}\) is any arbitrary value of the shunt at given irradiance.

We about to show how the irradiance estimator is obtained. If we substitute Eq. (4) into (1), we would have (5)

It should be noted that the term \(\:\widehat{G}\), has been introduced to convey that this manipulation does not yield the actual irradiance, but its estimate. For the purpose of simplicity, we can write establish the following nonlinear functions:

By substituting the above functions into (5) alongside (2) one have: (6)

Through rearrangements, we obtain the following:

Therefore, Eq. (8) is the explicit equation that will allow the RVE to estimate irradiance in real time. Despite the implicit nature of Eq. (1), the above manipulation obtains a straightforward equation for approximating the irradiance. Given that the estimate of irradiance is available, we can build a neural network model tailored for appreciating the MPP voltage. We resort to radial basis function neural network (RBF). Radial Basis Function neural networks provide a versatile and potent method for modeling intricate data. They are well-suited for function approximation due to their capacity to capture non-linear relationships through localized activation functions. The mathematical foundation, specifically the application of Gaussian functions and linear optimization for training, establishes a strong foundation for the effective application and comprehension of RBF networks in a variety of contexts. RBF activation functions are implemented in a three-layer network. The input layer receives the input measurements, processing them with RBF neurons in the hidden layers. The output retunes the approximated MPP voltage. The RBF is a real-world function whose output is contingent upon the distance from a center vector. The Gaussian function can be used to approximate it:

Where \(\:x=[T,\:\widehat{G}]\:\) is the input vector, c is the center of the function and \(\:{\upsigma\:}\) is the standard deviation which controls the function’s width. Each neuron in the hidden layer computes the radial basis function for a given input vector x. The output of the i-th neuron is written as:

The output layer is a linear combination of the hidden layer outputs:

Where \(\:{w}_{i}\) represents the weight connection between the i-th hidden layer and the output, and \(\:{w}_{o}\)represents the output bias. The total number of neurons in the concealed layer is represented by the symbol N. It is worth noting that the RBF neural network chosen has three hidden layers and a neuron structure of (5 5). The Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm was employed to train the model, as indicated in40. It is important to note that the training process was conducted offline, a strategic decision that was made to reduce the system’s complexity during deployment. Offline training enables the computationally intensive components of model development to be managed independently, thereby alleviating the system’s workload during real-time operation. Specially constructed patterns, consisting of over 2000 points of irradiance and temperature were used to train the Neural Network model. The dataset in total consisted of irradiance ranging from 1 to 1000 W/m2 and temperature ranging from 10 to 50 °C. After training, testing and validation, the validated model was found to have a regression value of 0.999 and a mean squared error of a \(\:7\times\:{10}^{-5}\). Therefore, the \(\:\widehat{G}=F\left({I}_{pv},\:{I}_{pv},\:T\right)\), and the NN model together form the RVE. In the next discourse, we present the design of the nonlinear controllers used to coordinate the standalone system.

Nonlinear controller design

This section is aimed at presenting the nonlinear controllers designed to coordinate the standalone system. Due to the strong nonlinear dynamics of the system, we resort to nonlinear control design. The Lyapunov-based design has proven to be an outstanding approach for stabilizing nonlinear systems41,42,43. For the sake of emphasis, we would recall that the control design pursues the two objectives delineated in the previous sections. The first objective is achieved by acting on the Boost converter. While the second is pursued by acting on the Buck converter. A lot of studies has already been done on converter modelling and design, we would not place further emphasis on that. However, we note that the controllers are supposed to maximize the dynamics of the converters. For mathematical simplicity, the dynamics of the converters is derived considering ideal and lossless operation with the assumption of continuous conduction mode44,45,46. In addition, the following assumption is considered:

Assumption I

The overall PV system operates under uniform irradiance conditions such that the influence of partial shading is negligible.

Assumption II

For control design, the converters are assumed to be lossless such that their parasitic influences can be considered negligible.

Assumption III

The converters operate under continuous conduction mode.

The average mathematical model of the boost converter, which allows for continuity in control is presented in Eq. (12) according to44

Where \(\:{x}_{1},\:{x}_{2},\:{x}_{3}\) are the three states of the Boost converter and represent the average values over one period, of the PV voltage, \(\:{V}_{pv},\) inductor current, \(\:{i}_{a}\), and boost output voltage, \(\:{v}_{a}\). Also, \(\:{I}_{pv}\), denotes the PV current, while \(\:{C}_{a},\:{L}_{a}\), represent the Capacitance of the Capacitor at the input of the boost converter, and the Boost inductance respectively. Using the Lyapunov and backstepping technique, we derive the following nonlinear control law for the Boost converter.

Where, \(\:\phi\:\) is the reference voltage provided by the RVE, \(\:{K}_{1},{K}_{2},k\), are control gains. It should be noted that this control approach principally seeks to asymptotically vanish the error between the actual PV voltage and the RVE reference, \(\:{e}_{1}\). The stability of this controller can be proven by Lyapunov law and functions, following the approaches in44,47,48,49. See the appendix section for a rigorous presentation of the overall system’s stability.

On the other hand, the44,45,46. The average mathematical model of the boost converter, which allows for continuity in control is presented in Eq. (12) according to45

Where \(\:{x}_{4},\:{x}_{5}\) are the states of the Buck converter and represent the average values over one period, of the inductor current, \(\:{i}_{b},\) and Buck output voltage, \(\:{v}_{b}\). Also, \(\:{C}_{b},\:{L}_{b}\), represent the Capacitance and Inductance of the Buck converter. The load is resistive and modelled by a resistance, R. Using the Lyapunov and backstepping technique, we derive the following nonlinear control law for the Buck converter

Where, \(\:\varOmega\:\) is the reference voltage, which can either be manually be set by the operator or determined according to a specific application. It is also noted that, \(\:{c}_{1}\) and \(\:{c}_{2}\) are control gains for the Nonlinear controller-2. It can also be noted that this control approach principally seeks to asymptotically vanish the error between the actual output voltage and a set reference, \(\:{z}_{1}\). The stability of this controller can be proven by Lyapunov law and functions, following the approaches in45. Therefore the control law, \(\:{u}_{2}\), is expected to stabilize the output of the standalone system. A rigorous analysis of the overall system’s stability is presented in Appendix B. In the subsequent discourse, we will discuss how the system is implemented.

Overall system implementation and MIL setup

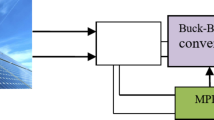

This section aims at comprehensively describing how the proposed system is implemented. We resort to a practical approach termed Microcontroller-in-the-loop (MIL) experimentation. The general structure of the MIL configuration is shown in Fig. 2. In this practical approach, the plant runs on the host computer while the controller is executed on a practical embedded microcontroller board. The link between the host computer is ensured through a specialized communication link. The controller is deployed and executed using C/C + + code. The MIL allows the overall system to run in real time. For the proposed standalone system, we implemented the plant on the host computer while the controllers where executed on an Arduino-Due board (see Fig. 3). The communication link is ensured by serial communication protocol. Additionally, we note that the two controllers were properly discretized before integration into the setup. The control laws, \({u}_{1}, {u}_{2}\), are executed by the Arduino-Due, which will be transmitted through the communication link to the host computer where the Boost and Buck converters are coordinated. Coordination action is received in the form of PWM signals. The PWM of the Boost and Buck converter operates at 300 Hz and 62,500 Hz respectively.

To successfully execute MIL experiments, it is crucial to ensure data type synchronization between the standalone system running on the host computer and the microcontroller. Typically, since the plant operates on a 64-bit architecture (the host computer), the microcontroller should ideally support 64-bit operations to maintain precision and consistency. The Arduino Due, powered by a 32-bit ARM Cortex-M3 processor, is capable of handling 64-bit operations efficiently due to its architecture and configuration.

Experimental results and discussion

Several experiments were performed to assess the standalone system under the coordination of the two nonlinear controllers. The system was investigated under the protocol described in Fig. 3. The following parameters were used in the experiments (Table 2): Boost converter [\(\:{C}_{a}=370\,\text{uF}\:,\:{L}_{a}=0.3\,\text{mH}]\), Buck converter [\(\:{C}_{b}=50\,\text{uF}\:,\:{L}_{b}=15\,\text{mH}]\), Nonlinear Controller-1 [\(\:{K}_{1}=1.375\times\:{10}^{5},\:{K}_{2}=10000,\:k=1000\:]\), Nonlinear Controller-2 [\(\:{c}_{1}=2.8075\times\:{10}^{4},\:{c}_{2}=6.2602\times\:{10}^{4}\:]\). The sampling time of the experimental platform was \(\:1\times\:{10}^{-6}\)s. A 60 W solar panel was consistently used in this study. Its parameters are : [\(R_{s} = 0.0018\Omega ,\:R_{{p,ref}} = 400\Omega ,\:I_{{ph,ref}} = 3.8\:A,\:I_{{s,ref}} = 2.454 \times 10^{{ - 6}} ,\:n = 1.6\). In order to evaluate the attainment of our control objectives, two principal metrics were employed; the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and the Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE). The tracking time, \(\:{T}_{r}\), was also used to record the time taken for convergence to the actual value.

Where \({y}_{a},\) represents the actual variable, \(\:{y}_{b\:}\), denotes the expected variable, while N denotes the number of observations or samples. In order to assess objective-1, we employ the MAE, so that \(\:{y}_{a}\), will be the actual PV voltage and \(\:{y}_{b}\) being the reference voltage provided by the RVE, φ. We note that the outcome of the MAE speaks directly about the power harvesting performance of the system; the closer its value to zero, the more efficient the system is. We will also occasionally use the tracking time to appreciate the convergence performance of the system to the RVE reference. Also, objective-2 will be evaluated by the MAE.

Evaluation of the RVE performance

This section seeks to evaluate the performance of the RVE. We employed the MAE ad well as the MAPE to achieve this evaluation. The actual variable is the estimate of irradiance (\(\:\widehat{G})\), while the expected variable is the true irradiance (G). To achieve this evaluation, the RVE was subjected to two different sets of Random Climatic Patterns (RCP), namely, RCP-1 and RCP-2.

The performance of the RVE for RCP-1 is presented in Figs. 4 and 5, while for RCP-2, the outcomes are presented in Figs. 6 and 7. It can be seen that the estimated irradiance aligns well with the actual irradiance. The approximated MPP voltage aligns also with the actual MPP voltage. We found that under RCP-1, estimator recorded MAE and MAPE of 4.3489 W/m2 and 1. 41%, while the voltage estimation was accurate to an MAE and MAPE of 0.2755 V and 3.0347%. Additionally, under RCP-2, the estimator recorded MAE and MAPE of 4.1901 W/m2 and 1. 3410%, while the voltage estimation was accurate to an MAE and MAPE of 0.2542 and 2.3527%. It cannot be overstated that these values are very close to exceptionally accurate; they are all very close to zero. This shows that the RVE performed outstandingly. Guided by this remarkable performance, the RVE was integrated into the system for subsequent evaluations. It should be noted that the RVE will be considered as the reference of the system; it will be the basis against which the MPPT performance will be evaluated.

Evaluation under stable climatic conditions with a fixed DC load and fixed output reference voltage

The subsection is aimed at presenting and discussion the outcomes of the standalone PV system when it was evaluated under stable climatic conditions, fixed DC load and fixed output reference. The climatic conditions were fixed at standard test condition, G = 1000 W/m2, T = 25 °C. The DC load was fixed 100Ω, while the output reference voltage, Ω = 12 V. The result of this experiment are presented in Fig. 8. It can be seen that the system tracked the reference voltage on the PV side in just 2ms with little or no oscillations at steady-state. On the DC load side, it was found that the system tracked the desired reference load voltage of 12 V in just about 3ms, with no oscillations at steady-state. However, there was an initial overshoot stemming from the strong nonlinear dynamics of the overall system. The MAE on the PV side is found to be 0.2108 V while on the DC side, it was 0.2011 V. This small deviation values indicate that the system operated at effectively at the MPP as well as at the desired reference load voltage.

Evaluation under abrupt changes in climatic condition, abrupt changes in load reference and fixed load voltage

The subsection is aimed at presenting and discussion the outcomes of the standalone PV system when it was evaluated under abruptly changing climatic conditions, fixed DC load and abruptly changing output or DC load reference voltage. Within the operating time range of 0 to 0.05s, G was fixed at G = 1000 W/m2, while the load reference voltage was constantly at Ω = 12 V. At exactly 0.05s, the DC reference was increased to 18 V while G was unaltered. Then finally at 0.1s, G was brought down to G = 100 W/m2. The results of this experiment are presented in Fig. 9. We found the MAE on the PV side to be 0.1653 V while on the load side it was 0.4052 V. On the PV side, it was found that the PV voltage consistently followed the reference in spite of the alterations in irradiance. This shows the effectiveness of the MPPT controller. The challenging conditions caused by transients was effectively handled by the Nonlinear controller-1. It was observed that alterations in the reference voltage did not have a noticeable effect on the PV side. This indicates that the controller on this side can perpetually focus on maximizing power harvesting from the PV module. This is a serious advantage of the two stage controlled circuitry. On the load side, we notice firstly that the in spite of the heavy alterations in G, the Nonlinear controller-2 succeeded in enforcing the reference voltage. A change of reference voltage from 12 V to 18 V introduced a strong underdamped characteristics marked by overshoots in the transient. However, the results show that the controller rapidly adjusted the dynamics of the system; resulting in smooth tracking of the load reference voltage. The outcome of this experiment, as discussed, reveals that the two control objectives were achieved.

Performance under stable G, fixed abruptly changing DC reference voltage, and load uncertainty

The subsection is aimed at presenting and discussion the outcomes of the standalone PV system when it was evaluated under stable climatic conditions, uncertain DC load and abruptly changing output or DC voltage reference. The climatic conditions were fixed at standard test condition, G = 1000 W/m2, T = 25 °C. The reference output voltage was maintained at 12 V until the time of 0.05s when it was changed to 20 V and maintained again until the time of 0.1s when it was changed to 8 V. In this instances of voltage changes, the load was altered from 100 to 30 Ω and then to 120Ω. The results of this experiment are presented in Fig. 10.

It was found that the PV side operation was unaltered in this experiment while the load responded according to the plot in Fig. 10. It was found that the changes in reference voltage and load alterations introduced strong underdamped dynamics in the standalone system; this is a possible explanation for the appearance of overshoots. At 0.05s, when the reference voltage increased from 12 to 20 V and the load resistance changed from 100Ω to 30Ω, it was observed that the actual load voltage deviated from the reference by more than 200%. However, the Nonlinear controller-2 rapidly restored this voltage to the expected reference in just about 2.8 ms after which the load operated perpetually at the reference voltage. At 0.1s, when the reference voltage decreased from 12 to 8 V and the reference load resistance changed from 30Ω to 120Ω, it was observed that the actual load voltage experiences a slight overshoot before rapidly tracing the desired reference voltage in just about 4ms. This outcome indicates that the Nonlinear controller-2 was very robust, effectively achieving objective-1 with an accuracy, measured by MAE of 0.4621 V.

Performance under continually changing G, continually changing output reference voltage and uncertain load

This section evaluates the robustness and adaptability of the proposed standalone PV system under the most realistic and demanding operating conditions—namely, simultaneously changing irradiance (G), temperature (T), output reference voltage (Ω), and uncertain load resistance. This setting simulates the complexity of real-world environments where PV systems are expected to operate reliably.

As shown in Fig. 11, the irradiance begins at 300 W/m² and steadily rises to 1000 W/m² before gradually falling back to 300 W/m², while the temperature varies stochastically between 15 and 40 °C. Simultaneously, the output voltage reference varies dynamically from 12 to 30 V, and the load resistance transitions through three abrupt changes: from 100 Ω (0–0.05 s), to 30 Ω (0.05–0.1 s), and finally to 120 Ω (0.1–0.8 s).

The system’s performance under these highly dynamic and uncertain conditions is illustrated in Figs. 12 and 13, where the actual responses are compared against their respective references.

-

A.

MPPT tracking under variable climatic conditions (Fig. 12).

Figure 12 highlights the effectiveness of the MPPT mechanism. Despite the unpredictable and continuous variations in both irradiance and temperature, the PV voltage closely follows the reference MPP voltage (φ). This indicates that the Reference Voltage Estimator (RVE) and the associated Nonlinear Controller-1 maintain strong coordination, enabling the system to consistently operate at the MPP with high fidelity. Notably:

-

No significant divergence is observed between the actual PV voltage and the reference voltage, even during rapid climatic transitions.

-

The Mean absolute error (MAE) is maintained at a remarkably low value of 0.1253 V, underscoring the accuracy of the MPP tracking algorithm.

-

The MPPT operation remains unaffected by load perturbations, validating the decoupled architecture of the two-stage converter design.

-

B.

Load voltage regulation under uncertainty (Fig. 13).

Figure 13 presents the system’s response on the load side. Here, the most critical challenge lies in handling concurrent changes in load resistance and output reference voltage. The performance reveals the following key insights:

-

Transient overshoots and settling: Sudden changes in reference voltage and load resistance introduce underdamped transient behavior. Despite this, the output voltage converges to the reference within 3 ms, reflecting the finite-time convergence capability of Nonlinear Controller-2.

-

Robust recovery: For instance, when the load drops from 100 Ω to 30 Ω while the reference increases, the controller swiftly suppresses the overshoot and stabilizes the output voltage.

-

Superior accuracy: The MAE on the load side is an impressively low 0.0793 V, confirming high-precision regulation even under coupled disturbances.

-

High disturbance rejection: This experiment strongly affirms the disturbance rejection analysis presented in Appendix A, particularly the system’s resilience under combined reference, climatic, and load perturbations.

-

C.

Critical and conclusive perspective.

The outcomes shown in Figs. 12 and 13 collectively validate the dual-objective control strategy proposed in this paper:

-

1.

Objective 1 (Efficient MPPT): Achieved through close MPP tracking (MAE = 0.1253 V) under time-varying G and T.

-

2.

Objective 2 (Reliable Voltage Regulation): Achieved through prompt stabilization of the load voltage (MAE = 0.0793 V) under changing Ω and R.

These results emphasize the system’s superior coordination, minimal steady-state error, and fast convergence, all of which are critical for deploying PV systems in off-grid or harsh environments. The robustness exhibited here demonstrates the practical readiness of the system for real-time deployment. The control strategies’ precision is underscored by these exceptionally small error values, which also affirm that the system’s design objectives—ensuring reliable MPP tracking and finite-time load voltage regulation—were successfully accomplished. The system’s capacity to operate efficiently under a variety of challenging conditions is emphasized by the results, which satisfies the two objectives of load regulation and stable energy production. It was essential to achieve the robust system performance by coordinating the response between the MPPT controller and the nonlinear control strategies.

Conclusion

This research set out with the clear objective of developing and validating a comprehensive dual-objective control strategy for standalone PV systems: (i) ensuring efficient maximum power point tracking for robust energy harvesting, and (ii) achieving precise and stable load-side voltage regulation under variable environmental and load conditions. Both simulation analyses and microcontroller-in-the-loop experimental results demonstrated that this objective was successfully achieved. Through the integration of the novel Reference Voltage Estimator (RVE) and nonlinear Lyapunov-based controllers within a two-stage (Boost–Buck) architecture, the system consistently operated at the maximum power point while simultaneously regulating the output voltage with high accuracy. The simulation results confirmed the theoretical robustness of the control strategy, while microcontroller-in-the-loop experimentation validated its real-time applicability, resilience to abrupt climatic and load variations, and fast recovery from disturbances. Performance indices—such as mean absolute error (MAE) values of 0.1253 V on the PV side and 0.0793 V on the load side—highlight the precision and reliability of the proposed scheme. In summary, the dual objectives of the study were fully realized, bridging a critical gap in the literature by combining optimum power extraction with reliable voltage regulation in a single framework. The outcomes confirm the practical viability of the system for real-world standalone PV applications, thereby contributing a robust and scalable solution to renewable energy deployment. A future study could investigate the potential for implementing such a control approach for PV-storage connected systems as well as for larger-scale PV installations. Also, while the proposed strategy excels under uniform irradiance, partial shading conditions—characterized by multiple power peaks—require global MPPT techniques. Future work will integrate hybrid algorithms (e.g., combining the RVE with metaheuristic optimization) to address shading-induced challenges, further enhancing the system’s applicability in complex environments.

Data availability

Data Related to this paper can be found in Figshare open access Data repository with the DOI link: 10.6084/m9.figshare.28783733.

References

Hassan, M. U., Nawaz, M. I. & Iqbal, J. Towards autonomous cleaning of photovoltaic modules: Design and realization of a robotic cleaner, in 2017 first Int. Conf. Latest Trends Electr. Eng. Comput. Technol. 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1109/INTELLECT.2017.8277631 (2017).

Iqbal, J. & Khan, Z. H. The potential role of renewable energy sources in robot’s power system: A case study of Pakistan. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 75, 106–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2016.10.055 (2017).

Renewable, I. & Agency, E. Renewable Energy Statistics 2024 Statistiques D ’ Énergie Renouvelable 2024 Estadísticas De Energía (2024).

Victoria, M. et al. Solar photovoltaics is ready to power a sustainable future. Joule 5, 1041–1056. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joule.2021.03.005 (2021).

Hu, H. et al. Triple-junction perovskite–perovskite–silicon solar cells with power conversion efficiency of 24.4%. Energy Environ. Sci. 17, 2800–2814. https://doi.org/10.1039/D3EE03687A (2024).

Yamaguchi, M., Dimroth, F., Geisz, J. F. & Ekins-Daukes, N. J. Multi-junction solar cells paving the way for super high-efficiency. J. Appl. Phys. 129 https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0048653 (2021).

Thakur, A. & Singh, D. Enhancing power conversion efficiency of lead-free perovskite solar cells: A numerical simulation approach. Indian J. Phys. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12648-024-03365-3 (2024).

Siddique, M. A. B., Zhao, D. & Rehman, A. U. Emerging maximum power point control algorithms for PV system: Review, challenges and future trends. Electr. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00202-025-03002-0 (2025).

Bakar Siddique, M. A. et al. Implementation of incremental conductance MPPT algorithm with integral regulator by using boost converter in grid-connected PV array. IETE J. Res. 69, 3822–3835. https://doi.org/10.1080/03772063.2021.1920481 (2023).

Siddique, M. A. B., Zhao, D. & Jamil, H. Forecasting optimal power point of photovoltaic system using reference current based model predictive control strategy under varying climate conditions. Int. J. Control Autom. Syst. 22, 3117–3132. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12555-023-0823-7 (2024).

Tchouani Njomo, A. F., Kenne, G., Douanla, R. M. & Sonfack, L. L. A modified ESC algorithm for MPPT applied to a photovoltaic system under varying environmental conditions. Int. J. Photoenergy 2020, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/1956410 (2020).

Baba, A. O., Liu, G. & Chen, X. Classification and evaluation review of maximum power point tracking methods. Sustain. Futur. 2, 100020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sftr.2020.100020 (2020).

Harrison, A., Nfah, E. M., de Dieu Nguimfack, J., Ndongmo, N. H. Alombah an enhanced P&O MPPT algorithm for PV systems with fast dynamic and steady-state response under real irradiance and temperature conditions. Int. J. Photoenergy 2022, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/6009632 (2022).

Senthilkumar, S. et al. A review on MPPT algorithms for solar pv systems. Int. J. Res. 11. https://doi.org/10.29121/granthaalayah.v11.i3.2023.5086 (2023).

Ahmed, J. & Salam, Z. An improved perturb and observe (P & O) maximum power point tracking (MPPT) algorithm for higher efficiency. 150, 97–108 (2015).

Priyadarshi, N., Padmanaban, S., Holm-Nielsen, J. B., Blaabjerg, F. & Bhaskar, M. S. An experimental estimation of hybrid ANFIS–PSO-Based MPPT for PV grid integration under fluctuating sun irradiance. IEEE Syst. J. 14, 1218–1229. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSYST.2019.2949083 (2020).

Priyadarshi, N., Padmanaban, S., Kiran Maroti, P. & Sharma, A. An extensive practical investigation of FPSO-based MPPT for grid integrated PV system under variable operating conditions with anti-islanding protection. IEEE Syst. J. 13, 1861–1871. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSYST.2018.2817584 (2019).

Priyadarshi, N. et al. A hybrid photovoltaic-fuel cell-based single-stage grid integration with Lyapunov control scheme. IEEE Syst. J. 14, 3334–3342. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSYST.2019.2948899 (2020).

Priyadarshi, N., Bhaskar, M. S., Almakhles, D. A novel hybrid whale optimization algorithm differential evolution algorithm-based maximum power point tracking employed wind energy conversion systems for water pumping applications: Practical realization. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 71, 1641–1652. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIE.2023.3260345 (2024).

Priyadarshi, N., Bhaskar, M. S., Almakhles, D. & Azam, F. A new PV fed high gain boost boost-Cuk converter employed SRM driven water pumping scheme with IDEPSO MPPT. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 40, 2371–2384. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPEL.2024.3459810 (2025).

Fangrui Liu, S. et al. INC MPPT method for PV systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 55, 2622–2628. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIE.2008.920550 (2008).

Jiandong, D., Ma, X., Tuo, S. A variable step size P&O MPPT algorithm for three-phase grid-connected PV systems. In: 2018 China Int. Conf. Electr. Distrib. 1997–2001. https://doi.org/10.1109/CICED.2018.8592040 (2018).

Jain, S., Member, S., Agarwal, V. & Member, S. A new algorithm for rapid tracking of approximate maximum power point in photovoltaic systems. https://doi.org/10.1109/LPEL.2004.828444 (2004).

Mahmod Mohammad, A. N., Mohd Radzi, M. A., Azis, N. & Shafie, S. Atiqi Mohd Zainuri, M. A. An enhanced adaptive perturb and observe technique for efficient maximum power point tracking under partial shading conditions. Appl. Sci. 10, 3912. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10113912 (2020).

Yildirim, M. A. & Nowak-Ocłoń, M. Modified maximum power point tracking algorithm under time-varying solar irradiation. Energies 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13246722 (2020).

Chellakhi, A., Beid, S. E., Abouelmahjoub, Y. & Doubabi, H. An enhanced incremental conductance MPPT approach for PV power optimization: A simulation and experimental study. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13369-024-08804-1 (2024).

Belghiti, H. et al. Performance optimization of photovoltaic system under real Climatic conditions using a novel MPPT approach. Energy Sources Part A Recover. Util. Environ. Eff. 46, 2474–2492. https://doi.org/10.1080/15567036.2024.2308656 (2024).

Hassan, A., Bass, O. & Masoum, M. A. S. An improved genetic algorithm based fractional open circuit voltage MPPT for solar PV systems. Energy Rep. 9, 1535–1548. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egyr.2022.12.088 (2023).

Belghiti, H. et al. Efficient and robust control of a standalone PV-storage system: An integrated single sensor-based nonlinear controller with TSCC-battery management. J. Energy Storage 95, 112630. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2024.112630 (2024).

Anjum, M. B. et al. Maximum power extraction from a standalone photo voltaic system via neuro-adaptive arbitrary order sliding mode control strategy with high gain differentiation. Appl. Sci. 12, 2773. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12062773 (2022).

Cherukuri, S. K. & Rayapudi, S. R. Enhanced grey Wolf optimizer based MPPT algorithm of PV system under partial shaded condition. Int. J. Renew. Energy Dev. 6, 203. https://doi.org/10.14710/ijred.6.3.203-212 (2017).

Baatiah, A. O., Eltamaly, A. M. & Alotaibi, M. A. Improving photovoltaic MPPT performance through PSO dynamic swarm size reduction. Energies 16, 6433. https://doi.org/10.3390/en16186433 (2023).

Elbaksawi, O. et al. Innovative metaheuristic algorithm with comparative analysis of MPPT for 5.5 kW floating photovoltaic system. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 185, 1072–1088. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2024.03.082 (2024).

Harrison, A. et al. Robust nonlinear MPPT controller for PV energy systems using PSO-based integral backstepping and artificial neural network techniques. Int. J. Dyn. Control https://doi.org/10.1007/s40435-023-01274-7 (2023).

Belghiti, H., Kandoussi, K., Harrison, A., Moustaine, F. Z. & Sadek, E. M. Simplified control algorithm for stable and efficient standalone PV systems: An assessment based on real climatic conditions. Comput. Electr. Eng. 120, 109695. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compeleceng.2024.109695 (2024).

Chellakhi, A. et al. Implementation of a low-cost current perturbation-based improved PO MPPT approach using arduino board for photovoltaic systems. E-Prime - Adv. Electr. Eng. Electron. Energy 100807. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prime.2024.100807 (2024).

Saleem, O., Ali, S., Iqbal, J. & Robust, M. P. P. T. Control of stand-alone photovoltaic systems via adaptive self-adjusting fractional order PID controller. Energies 16, 5039. https://doi.org/10.3390/en16135039 (2023).

Henry Alombah, N., Harrison, A., Kamel, S., Bertrand Fotsin, H. & Aurangzeb, M. Development of an efficient and rapid computational solar photovoltaic emulator utilizing an explicit PV model. Sol Energy. 271, 112426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2024.112426 (2024).

Harrison, A., Feudjio, C., Raoul Fotso Mbobda, C. & Alombah, N. H. A new framework for improving MPPT algorithms through search space reduction. Results Eng. 101998. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2024.101998 (2024).

Markopoulos, A. P., Georgiopoulos, S. & Manolakos, D. E. On the use of back propagation and radial basis function neural networks in surface roughness prediction. J. Ind. Eng. Int. 12, 389–400. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40092-016-0146-x (2016).

de Queiroz, M. S., Dawson, D. M., Nagarkatti, S. P. & Zhang, F. Lyapunov-based control of mechanical systems. (Birkhäuser Boston, Boston, MA, 2000). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4612-1352-9

Ballaben, R., Braun, P. & Zaccarian, L. Lyapunov-based avoidance controllers with stabilizing feedback. IEEE Control Syst. Lett. 8, 862–867. https://doi.org/10.1109/LCSYS.2024.3404770 (2024).

Bhunia, M., Subudhi, B. & Ray, P. K. A lyapunov-based adaptive voltage controller for a grid connected PV system. IET Smart Grid. 4, 381–396. https://doi.org/10.1049/stg2.12045 (2021).

Harrison, A., Alombah, N. H., de Dieu Nguimfack Ndongmo, J. A new hybrid MPPT based on incremental conductance-integral backstepping controller applied to a PV system under fast-changing operating conditions. Int. J. Photoenergy 2023, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/9931481 (2023).

Harrison, A. & Alombah, N. H. A new high-performance photovoltaic emulator suitable for simulating and validating maximum power point tracking controllers. Int. J. Photoenergy 2023, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/4225831 (2023).

Harrison, A. & Alombah, N. H. A new piecewise segmentation based solar photovoltaic emulator using artificial neural networks and a nonlinear backstepping controller. Appl. Sol Energy 59, 283–304. https://doi.org/10.3103/S0003701X23600285 (2023).

Arsalan, M. et al. MPPT for photovoltaic system using nonlinear backstepping controller with integral action. Sol Energy 170, 192–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2018.04.061 (2018).

El Myasse, I., Watil, A., El Magri, A. & Harrison, A. Nonlinear control design of three-level neutral-point-clamped-based high-voltage direct current systems for enhanced availability during AC faults with semi-experimental validation. Eng. Proc. 56 https://doi.org/10.3390/ASEC2023-15336 (2023).

Aouadi, C. et al. Nonlinear controller design and stability analysis for single-phase grid-connected photovoltaic systems. Int. Rev. Autom. Control 10, 306–315. https://doi.org/10.15866/ireaco.v10i4.12322 (2017).

Acknowledgment

This research has been funded by Scientific Research Deanship at University of Ha’il - Saudi Arabia through project number (RG-24 014).

Funding

This research has been funded by Scientific Research Deanship at University of Ha’il - Saudi Arabia through project number (RG-24 014).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.A: Methodology, Investigation, Writing-Editing & Review, Funding Acquisition, Project Administration, Resources, Software, simulations. A.H: Conceptualization, Writing-Drafting of Manuscript, Methodology, Investigation, Methodology, Investigation. I.A, A.A, M.A: Methodology, Investigation, Writing-Editing & Review, Project Administration.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Almalaq, A., Harrison, A., Alsaleh, I. et al. Comprehensive control strategy for standalone photovoltaic systems with integrated optimum power harvesting and voltage regulation through microcontroller in the loop experimentation. Sci Rep 15, 38435 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24134-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24134-0