Abstract

Chronic diseases are highly prevalent among older adults and may be associated with their ability to achieve successful aging, which encompasses five key components: absence of major chronic diseases, freedom from disability, high cognitive function, no depressive symptoms, and active social participation. However, many disease conditions are excluded from conventional definitions of successful aging. This study aims to quantify the predictive effects of multiple chronic diseases on overall successful aging and its five core components, thus providing new evidence to refine aging frameworks. Data were obtained from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) covering the years 2011, 2013, and 2015. Six common chronic diseases not traditionally included in the successful aging definition were selected: hypertension, dyslipidemia, arthritis, kidney disease, liver disease, and digestive disease. Six machine learning models were applied to construct prediction frameworks of successful aging and chronic diseases. The SHapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) and ALE (Accumulated Local Effects) analyses were used to quantify the impact of each chronic disease on the prediction of successful aging, providing both global and individual-level interpretability. Logistic regression was conducted to examine the associations between key diseases identified by SHAP and the five components of successful aging. A total of 4,385 participants were included initially in this study, and a total of 1,104 participants were selected after propensity score matching for subsequent analysis. After hyperparameter tuning with Optuna, the XGBoost model was chosen for model interpretation and prediction (F1 = 0.781, F2 = 0.891, AUC = 0.707, AUPRC = 0.724). SHAP analysis indicated that hypertension, kidney disease, and arthritis were the most influential predictors of successful aging. Additionally, SHAP results highlighted that sleep duration was also among the most important features. Subsequent logistic regression further revealed that, beyond their associations with the disease component, kidney disease and arthritis were significantly linked to depressive symptoms and cognitive function, while hypertension was strongly associated with physical functioning. Our findings highlight that several chronic diseases not traditionally included in successful aging criteria are significantly associated with aging outcomes. Extending the disease spectrum within the definitions of successful aging may enhance individual-level assessment and provide insights for future research on targeted health interventions for the older adults. Furthermore, these findings may help raise awareness of health factors associated with successful aging.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Population aging has emerged as a pressing global public health and socioeconomic challenge these days1,2. China, one of the world’s fastest-aging countries, is projected to enter the stage of severe aging by 2035, with over 400 million individuals aged 60 or above3,4. With the intensifying global population aging, the high prevalence of chronic diseases among the elderly has become a critical health problem5,6. Chronic diseases, such as hypertension, diabetes, asthma, and arthritis, are prevalent among older adults7,8. Aging not only increases the complexity of chronic disease manifestations but also elevates the mortality risk9,10. Recent studies have shown that chronic diseases negatively affect depressive symptoms and social participation among older adults11. For instance, conditions such as hypertension and arthritis are particularly significant, contributing heavily to dysfunction in activities of daily living (ADL) and limitations in social participation12. Furthermore, research indicates that chronic diseases like diabetes, heart disease, and respiratory diseases can lead to emotional distress, anxiety, and depression13. These conditions not only elevate mortality and disability risk but also impair mental health and limit social engagement, thereby affecting quality of life and placing increasing pressure on healthcare and social systems.

In response to the global shift from “living longer” to “aging well”, the concept of successful aging has received growing attention14. Successful aging is a vital indicator of older adults’ overall health, originally introduced by Rowe and Kahn in 1987. They defined it as encompassing five main components: the absence of major diseases, no disabilities, high cognitive function, no depressive symptoms, and active social engagement15. This multidimensional framework offers a comprehensive lens for evaluating late-life health and function. Numerous studies have shown that successful aging is associated with improved life quality, longer functional years, and reduced societal burden16. However, chronic diseases, particularly those commonly seen in aging populations, can compromise multiple dimensions of successful aging by inducing physical decline, cognitive impairment, and emotional distress17. Despite the global rise in aging populations, a meta-analysis of 64 studies found that only 22% of individuals aged ≥ 60 years met the criteria for successful aging, with the absence of major diseases being the least commonly achieved domain (50%)18. Therefore, investigating the factors, especially in the disease domains, that contribute to successful aging is crucial for the development and optimization of aging policies, as well as for improving the quality of life for the elderly and promoting the overall well-being of society19.

While successful aging has been increasingly refined conceptually, the relationship between chronic diseases and successful aging remains underexplored20. Notably, most studies still adopt Rowe and Kahn’s original model to define the “absence of major disease”. Yet this framework was developed decades ago, and may no longer fully capture contemporary public health realities, either in China or globally21,22. Moreover, many common conditions which were not included in the original successful aging model, such as dyslipidemia, arthritis, and kidney disease, are highly prevalent in aging populations and may have a significant impact on physical, cognitive, and social functioning15. To date, few studies have quantified the predictive influence of these previously unrecognized chronic conditions on successful aging or examined their differential impact across the five core components of the concept. Also, prior studies have predominantly relied on traditional statistical approaches, which may fail to fully capture complex, non-linear interactions between multiple chronic conditions and the components of successful aging23. In the context of an increasingly aging population with high multimorbidity prevalence, there is a pressing need for data-driven approaches to identify high-impact chronic conditions that go beyond conventional criteria24.

To address this gap, six categories of chronic diseases which are out of the original definition of successful aging were selected based on data from the CHARLS survey conducted in 2011, 2013, and 2015. Six machine learning models were used to construct predictive models linking chronic disease profiles to successful aging. SHAP values and ALE analysis were applied to quantify the relative contribution of each disease to the model’s predictions. Furthermore, the associations between specific chronic conditions and the five components of successful aging were examined. These findings offer insights into expanding the “absence of major diseases” criterion in the successful aging definition, potentially supporting more inclusive assessments and informing targeted public health interventions.

Methods

Study design

This study employed a cross-sectional design based on data from the 2011, 2013, and 2015 waves of the CHARLS survey.

Study population

The China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) was designed to collect high-quality, nationally representative data on Chinese residents aged 45 years or older, focusing on health status, economic circumstances, and social networks25. The baseline survey was conducted in 2011, with follow-up surveys occurring every two years. The CHARLS study received approval from the Biomedical Ethics Review Board of Peking University (IRB00001052-11015), and respondents provided informed consent for participation and data collection. All data are maintained by the Institute of Social Science Survey of Peking University and are publicly available on the CHARLS project website (http://charls.pku.edu.cn).

The data used in this study were drawn from the 2011 (Wave 1), 2013 (Wave 2), and 2015 (Wave 3) follow-up survey of the CHARLS. The exclusion criteria for the present study were as follows: (1) individuals younger than 60 years old; (2) missing data on six chronic diseases; (3) no information on covariates including age, sex, sleep duration, BMI status, smoking, drinking, marital status, and community status; and (4) lack of successful aging information. Due to the small number of participants with complete longitudinal follow-up, which was insufficient for robust analysis, we excluded them and adopted a cross-sectional framework. The final sample included 1,113 participants in 2011, 1,316 in 2013, and 1,956 in 2015, totaling 4,385 individuals without follow-up during this period (Fig. 1).

Definition of successful aging

Our definition of successful aging is based on Rowe and Kahn’s model, and it includes five key components: (1) Absence of major disease, (2) Freedom from disability, (3) High cognitive function, (4) No depressive symptoms, and (5) Active social participation. Participants were classified as successfully aging only if all five criteria were met15. The operational definitions for each component are as follows:

-

1.

Absence of major diseases: The presence of major diseases in old age was determined by asking participants, "Have you ever been diagnosed by a doctor with any of the following diseases?" The diseases assessed included: cancer, chronic lung disease, diabetes, heart disease, and stroke. Participants who did not report a diagnosis of any of these conditions were classified as having no major diseases26.

-

2.

Freedom from disability: The Activities of Daily Living (ADL) scale was used to assess functional status27. This scale is based on questions such as: "Due to a physical, mental, emotional, or memory issue, do you experience any difficulty with any of the following everyday activities, excluding those you expect to last less than three months?” The activities assessed include dressing, bathing or showering, eating, getting in and out of bed, using the toilet, and controlling urination and bowel movements. Responses to each question were categorized as follows: no difficulty, difficulty but still able to complete, difficulty and need help, and unable to complete. In this study, each ADL response was initially recorded as 0, with scores of 1–4 assigned according to the level of difficulty. ADL scores were then classified into two groups: ADL-independent (ADL score = 0) and ADL-disabled (ADL score ≥ 1)28. Participants were considered free from disability if they were classified as ADL-independent.

-

3.

High cognitive function: Participants were considered to have high cognitive functioning if they scored at or above the median on the Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (TICS). The TICS includes tasks such as recalling ten words immediately and after a delay, repeatedly serial subtraction of seven from 100, naming the days of the week, month, day, year, and season, and drawing specific figures29.

-

4.

No depressive symptoms: Depressive symptoms were measured with the 10-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D 10)30. This scale, which has been validated for use among Chinese older adults, comprises 10 questions with four response options each: (1) rarely or none of the time (< 1 day); (2) some or a little of the time (1–2 days); (3) Occasionally or a moderate amount of the time (3–4 days); (4) Most or all of the time (5–7 days)31. Responses were scored from 0 to 3, resulting in a total score range of 0–30, with lower scores indicating fewer depressive symptoms. A cut-off score of 10 was used, with participants scoring below this threshold categorized as having no depressive symptoms32.

-

5.

Active social participation: Participants were considered socially active if they had participated in any of the following social activities within the month preceding the interview: voluntary or charity work, assisting family, friends, or neighbors, or attending sports, social, or other types of clubs33.

Assessment of chronic diseases in the elderly

The CHARLS surveys (2011, 2013, and 2015) included 14 common chronic diseases observed in older adults, specifically: (1) hypertension, (2) dyslipidemia, (3) diabetes or high blood sugar, (4) cancer or malignant tumors, (5) chronic lung diseases, (6) liver disease, (7) heart attack, (8) stroke, (9) kidney disease, (10) stomach or other digestive disorders, (11) emotional, nervous, or psychiatric problems, (12) memory-related diseases, (13) arthritis or rheumatism, and (14) asthma. For this study, we excluded the five disease categories classified as “major diseases” under the definition of successful aging, as well as asthma due to its strong association with chronic lung diseases. Additionally, due to the limitations inherent in cross-sectional studies and the complexity associated with certain conditions, cancer, and cognitive diseases were also excluded from our analysis34. Ultimately, this study focused on six chronic diseases prevalent among older adults: hypertension, dyslipidemia, liver disease, kidney disease, digestive disease, and arthritis.

Covariates

The CHARLS questionnaire gathers data on demographic characteristics, lifestyle factors, and anthropometric measurements. Previous research has identified several factors associated with successful aging and chronic diseases prevalence in later life, including smoking, alcohol consumption, age, BMI, sex, marital status, and community type26,32. These variables were adjusted for in the present study.

For demographic characteristics, the following variables were included: age (years), gender (male or female), community type (urban or rural), and marital status (married with spouse present, married but not living with spouse temporarily, divorced, separated, widowed, or never married). Lifestyle factors included alcohol consumption (never drinking, drinking less than once a month, or drinking more than once a month) and smoking status (smoking or non-smoking). Health related factors included body mass index (BMI) and sleep duration. BMI was calculated by dividing weight (kg) by height squared (m2) and categorized into four groups: underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (18.5–23.9 kg/m2), overweight (24–27.9 kg/m2), and obese (BMI ≥ 28 kg/m2). Total sleep duration per 24-h period was obtained by summing nighttime sleep and daytime nap durations35.

Statistical analysis and machine learning models

In this study, statistical comparisons between the successful aging and non-successful aging groups were performed using the chi-square test for categorical variables. Continuous variables were analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and presented as mean ± standard deviation.

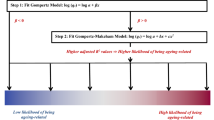

The overall framework for predicting successful aging status is illustrated in Fig. 1. First, to minimize baseline differences between participants with and without successful aging, propensity score matching (PSM) was conducted based on marital status, age, sex, and community type, using the nearest neighbor matching method with a 1:1 ratio and a caliper of 0.2. After matching, a total of 1,104 participants (552 with successful aging and 552 matched controls) were included. The matched dataset was then randomly divided into a training set (80%) and a testing set (20%) for model development and evaluation.

Subsequently, multiple machine learning models were used for training and prediction of successful aging. A total of six well-known models including XGBoost, LightGBM, Random Forest (RF), Gradient Boosting Decision Tree (GBDT), CatBoost and Logistic Regression (LR) were chosen to construct prediction models36. To assess model performance, six commonly used classification metrics were calculated: precision, recall, F1-score, AUC (Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve), AUPRC (Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve), and Brier score (see Supplementary Table 4)37. To optimize model performance, we applied Optuna based on Bayesian optimization for hyperparameter tuning with a predefined search space for each algorithm, embedding this process within a fivefold cross-validation loop on the training set38. For each Optuna trial, performance was assessed by averaging across the CV folds, and the hyperparameters with the best cross-validated results were selected. The final model, trained with these parameters, was then used for downstream interpretation and analysis.

Moreover, this study mainly adopted SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) and ALE (Accumulated Local Effects) interpretation methods to explain the model decision process. SHAP explains feature contributions to individual predictions and can be aggregated for global interpretability, emphasizing feature importance and additive effects39. Representative true positive (TP) and true negative (TN) samples were selected to visualize individual SHAP explanations. In these plots, each feature’s SHAP value reflects its positive or negative impact on the predicted probability of successful aging for that individual. In contrast, ALE estimates the average marginal effect of each feature on model output while accounting for feature interactions, providing a less biased and more robust view of feature influence across the dataset40. ALE plots were used to examine the marginal effects of key features and understand model behavior more comprehensively.

Finally, univariate (Model 0) and multivariate (Model 1) logistic regression were used to explore the deeper relation between main chronic diseases identified by SHAP and successful aging components. Model 1 was adjusted for potential confounders including sleep duration, smoking status, drinking status, and BMI status. The model results were presented as odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Statistical significance was set at 95% (p < 0.05), and all statistical analyses were conducted using R 4.4.1 and Python 3.9. The aplot R package was utilized for figure integration and visualization refinement41.

Results

Baseline characteristics of participants in this study

Participants who did not meet the study design criteria were excluded from the analysis (Fig. 1). A total of 4,385 participants were included in the present study, comprising 552 (12.59%) individuals classified as successful aging and 3,833 (87.41%) as non-successful aging (Table 1).

Compared with the non-successful aging group, individuals in the successful aging group were generally younger, more likely to be female, had longer sleep duration, and were more frequently residing in rural areas. They also had lower proportions of chronic diseases such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, kidney disease, digestive disease, and arthritis, as well as lower rates of smoking and alcohol consumption. Baseline characteristics analysis revealed significant differences between the two groups in term of sleep duration, age, BMI, hypertension, dyslipidemia, kidney disease, digestive disease, arthritis, marital status, community type, smoking, and drinking status (all p < 0.05).

To balance covariates between successful aging and non-successful aging groups, propensity score matching (PSM) was performed based on marital status, age, gender and community type, using nearest-neighbor matching with a 1:1 ratio and a caliper of 0.2. After matching, 1,104 participants were retained, equally divided into two groups. Post-matching analysis (Table 2) indicates that significant differences remain between two groups in sleep duration (p = 0.001), hypertension (p = 0.005), dyslipidemia (p < 0.001), kidney disease (p < 0.001), digestive disease (p = 0.003), and arthritis (p < 0.001). No significant differences were observed in age, BMI, marital status, community type, smoking or drinking status between the two groups, which were significant before PSM analysis.

Development of multiple machine learning approaches for successful aging prediction

Based on the PSM result, 1,104 balanced participants were used to develop machine learning models for predicting successful aging. 80% of the matched participants were randomly assigned to the training set, while the remaining 20% were allocated to the testing set for model validation. A total of six machine learning models were covered in this study, including RF (Random Forest), LR (Logistic Regression), CatBoost, XGBoost, GBDT (Gradient Boosting Decision Tree), and LightGBM. The baseline performance of these models (using default parameters) is shown in Supplementary Table 1. To enhance predictive performance, Optuna was employed for hyperparameters tuning using Bayesian optimization. The model performance on the testing set is shown in Table 3, and the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves of different models are plotted in Fig. 2. Additionally, five-fold cross-validation results for each model are presented in Supplementary Table 2. Overall, XGBoost demonstrated favorable and stable performance across key metrics in the five-fold cross-validation, including the highest recall (0.915 ± 0.048) and F1-score (0.677 ± 0.014), while maintaining a competitive AUC (0.619 ± 0.026) and an acceptable Brier score (0.262 ± 0.006).

After hyperparameter optimization, as shown in Table 3, all models achieved an AUC above 0.64, with four non-linear models (XGBoost, GBDT, LightGBM, and CatBoost) exceeding 0.70. CatBoost yielded the highest AUC of 0.725, followed closely by GBDT (AUC: 0.723) and LightGBM (AUC: 0.712). Random Forest and Logistic Regression showed moderate performance, with AUCs of 0.671 and 0.644, respectively. Despite CatBoost’s perfect recall (1.000), its low precision (0.557) and high Brier score (0.411) suggested potential overfitting.

XGBoost achieved relatively balanced and robust performance, with an F1-score of 0.781, a recall of 0.984, and an AUC of 0.707. It also attained the highest overall accuracy (0.692) and maintained a relatively low Brier score (0.220). Calibration analysis using a reliability diagram showed some miscalibration at lower predicted probabilities, while alignment improved in the mid-to-high range, suggesting overall acceptable probability estimates (Supplementary Fig. 1). In addition, XGBoost is widely used in biomedical prediction tasks and is fully compatible with interpretability methods. For these reasons, XGBoost was selected as the representative model for downstream interpretability analysis and prediction.

SHAP-based interpretation for model results

XGBoost model was selected for SHAP-based interpretation. Firstly, the importance of the input feature is calculated by SHAP and the optimal XGBoost model. As shown in Fig. 3a, feature importance is ranked in descending order. For binary variables, the positive class is used for further explanation. Features such as sleep duration, hypertension, kidney disease, arthritis, and smoking emerged as the most influential predictors of successful aging. Furthermore, the extent to which each feature affects the model’s output is illustrated in Fig. 3b, where the x-axis represents SHAP values.

Global importance of predictors based on XGBoost-SHAP analysis. Positive SHAP values indicate that a feature increases the predicted probability of successful aging, while negative values indicate a decreasing effect. Each dot represents an individual observation, colored according to the actual feature value (red for high, blue for low). The horizontal distance from the SHAP value = 0 axis reflects the magnitude of the feature’s impact on the model prediction. (a) Bar plot ranking features by their mean absolute SHAP values in the successful aging prediction model. (b) Beeswarm plot visualizing both the importance and the directionality of each feature’s effect on successful aging prediction.

As depicted in Fig. 3b, sleep duration exhibited a non-linear effect: while both high and low values clustered near the SHAP baseline (0), extreme SHAP values were associated predominantly with longer durations. For binary health status variables, including hypertension, kidney disease, arthritis, dyslipidemia, digestive disease, liver disease, and smoking, the presence of these conditions (value = 1) was generally associated with negative SHAP values, while their absence (value = 0) was associated with positive SHAP values. This indicates that being free from these chronic conditions positively contributes to the model’s prediction of successful aging. Notably, for dyslipidemia, low values clustered around the SHAP baseline, while high values appeared on the right. This pattern may reflect a weak or non-significant association with the model’s prediction.

Subsequently, individual-level analyses were conducted using SHAP, as shown in Fig. 4. SHAP values reflect how much each feature contributes to the predicted probability of successful aging. For example, “sleep duration = 8 h” in Fig. 4a indicates that this participant’s recorded sleep duration was 8 h. In Fig. 4a, having a history of liver disease decreases the likelihood of successful aging for this individual. The other medical conditions (hypertension, kidney disease, and digestive disease) were absent in this case, and they all promoted successful aging. The feature with the greatest positive influence was the absence of hypertension, which contributed most significantly to the prediction of successful aging, with a SHAP value of 0.14. The model predicted a probability of 0.853 of successful aging for this participant, which was higher than the average expected probability of 0.553. From Fig. 4b, having hypertension, and smoking currently reduced the chance of successful aging. Thus, the predicted successful aging probability for this individual sample was -0.558, which was much lower than the average expectation (E[f(x)] = 0.553). These findings highlight inter-individual variability in how specific factors influence the prediction of successful aging, illustrating the personalized insights gained through SHAP analysis.

SHAP-based instance-level explanation for two randomly selected samples. The X-axis represents the SHAP value. E[f(x)] indicates the expected model output across all samples, and f(x) denotes the predicted value for the given instance. Features in red contribute to increasing the probability of successful aging, while features in blue contribute to decreasing it. Longer arrows and larger SHAP values indicate stronger influence on the prediction. (a) Waterfall plot illustrating the SHAP decomposition for a true positive (TP) sample. (b) Waterfall plot illustrating the SHAP decomposition for a true negative (TN) sample.

ALE-based analysis and deeper insights into successful aging

Based on the SHAP analysis, the four most important features for predicting successful aging were identified, including three medical conditions (hypertension, kidney disease, and arthritis) as well as sleep duration. Among them, the three medical conditions exhibited a typical linear negative relationship with successful aging, indicating that the presence of chronic disease is significantly associated with a reduced probability of successful aging (hypertension: ALE 0.06 to -0.06; arthritis: ALE 0.05 to -0.05; kidney disease: ALE 0.10 to -0.10; Fig. 5a–c).

ALE-based analysis of the effects of the top four important features on model prediction. (a–c) Accumulated Local Effects (ALE) plots demonstrating a negative linear association between three major chronic diseases (kidney disease, arthritis, and hypertension) and the probability of successful aging.

Optimal sleep duration played a significant role in enhancing the likelihood of successful aging, exhibiting a clear non-linear relationship. For sleep duration, the ALE values remained low for durations less than 3 hours. Between 3 and 5 h, the ALE values increased sharply into the positive range, after which they stabilized. From 9 to 11 h, the ALE values showed a pattern of decline–stabilization–incline, followed by a gradual increase and plateau at higher positive values after 11 h (Supplementary Fig. 2). To further characterize the trend between sleep duration and successful aging, the restricted cubic spline (RCS) regression analysis was applied. The RCS curve revealed a significant inverted U-shaped relationship (p-overall < 0.0001, p-nonlinear < 0.0001), with the odds of successful aging increasing with sleep duration up to approximately 7.5 h, after which the odds gradually declined (Supplementary Fig. 3). Consistent with the RCS findings, logistic regression analyses (Supplementary Table 3) showed that, compared to the reference group (6–8 h), sleep durations of ≤ 4 h (OR = 0.190, 95% CI 0.091–0.362), 4–6 h (OR = 0.697, 95% CI 0.492–0.986), and ≥ 10 h (OR = 0.547, 95% CI 0.330–0.894) were significantly associated with reduced odds of successful aging, after adjustment for covariates.

Based on the top three chronic diseases identified by SHAP analysis (hypertension, kidney disease and arthritis), both univariate (Model 0) and multivariate (Model 1) logistic regression were conducted to examine their associations with successful aging and its five core components. All logistic regression analyses were performed based on the matched sample (n = 1104) obtained after PSM, ensuring balanced baseline characteristics between the successful aging and non-successful aging groups. In Model 0, all three medical conditions were significantly associated with lower odds of overall successful aging, absence of major disease, and freedom from disability, with odds ratios of 0.694 (95% CI 0.539–0.891) for hypertension, 0.366 (95% CI 0.208–0.620) for kidney disease, and 0.526 (95% CI 0.409–0.674) for arthritis (all p < 0.01). These associations remained significant in Model 1 after adjusting for sleep duration, smoking, drinking and BMI status. Consistent patterns were observed across subdomains both in Model 0 and Model 1. For example, kidney disease showed strong negative associations with the “No major disease” (OR = 0.342, 95% CI 0.206–0.570), “No disability” (OR = 0.346, 95% CI 0.197–0.630), and “No depressive symptoms” (OR = 3.914, 95% CI 2.267–6.725) components in Model 1. Arthritis was consistently associated with increased risk of disability and cognitive impairment, while hypertension had a modest but significant effect on disease burden and physical function.

Sensitivity and robustness analysis

To assess the robustness of the predictive models, a sensitivity analysis was performed by varying the train/test split ratios and evaluating four key performance metrics (ROC, F1-score, Brier score, and Accuracy) on test sets. Four models with AUC values after hyperparameter tuning exceeding 0.70 (XGBoost, CatBoost, GBDT, and LightGBM) were included in this analysis. As shown in Fig. 6, all models exhibited relatively stable performance across different data splits. Notably, the XGBoost model maintained AUC values mostly above 0.70, with only a few instances falling slightly between 0.68 and 0.70. The F1-score remained consistently around 0.75, accuracy mostly above 0.65, and the Brier score fluctuated narrowly around 0.20. Similar stability trends were observed for CatBoost, GBDT, and LightGBM, with no significant degradation or volatility in predictive metrics across varying partitions (Fig. 6b–d). All in all, the mean AUC and F1-score across all data splits for the XGBoost model were 0.71 and 0.75, respectively, further confirming the robustness of its predictive performance.

Discussion

Among the 1,104 participants included in this study after propensity score matching, the cross-sectional association between six chronic diseases and successful aging status was examined. Specifically, a total of six machine learning approaches were employed in the prediction model. XGBoost demonstrated a relatively balanced predictive performance, achieving a balanced performance across F1 score (0.781), F2 score (0.891), and AUC (0.707). Interpretability analysis using SHAP values identified hypertension, kidney disease, and arthritis as the top negative contributors to successful aging prediction. These diseases are not traditionally included in the “no major diseases” criterion. Finally, multivariate logistic regression further showed that kidney disease and arthritis were significantly associated with depressive symptoms and lower cognitive functioning, while hypertension was strongly related to physical functioning. These are core domains of the successful aging framework.

Most existing studies on successful aging have primarily focused on theoretical reviews or descriptive analyses of its prevalence in specific region42. While these works have contributed to conceptual development, they often relied on early definitions of successful aging, particularly the original Rowe and Kahn model, which emphasizes the absence of major diseases without incorporating region-specific health contexts or ethnic variations. Such static criteria may overlook common but impactful chronic conditions prevalent in certain populations. Moreover, the influence of different diseases on successful aging has rarely been quantitatively assessed, resulting in definitional inconsistencies and potential misclassification over time43. To address these gaps, our study applied the XGBoost algorithm to quantify the importance of major chronic diseases in successful aging. XGBoost is an ensemble learning method known for its robustness and superior performance in handling structured tabular data44. Compared with traditional statistical models, XGBoost effectively captures non-linear interactions and complex feature relationships, which are particularly relevant in aging populations with multimorbidity. By integrating the SHAP method, we further enhanced the interpretability of the model, enabling both global and individual–level understanding of how each chronic condition influences successful aging45.

Importantly, SHAP analysis enabled us to quantify the relative importance of six chronic diseases, none of which are traditionally classified as “major diseases”, in predicting successful aging. The global SHAP summary revealed hypertension, kidney disease, and arthritis as the top negative predictors. Notably, SHAP analysis identified hypertension as the most important chronic condition negatively associated with successful aging, contributing the highest share among all disease-related features. This finding aligns with existing global evidence underscoring the profound burden of hypertension on elderly health. A comprehensive global study stated the largest proportion (30.3%) of the total disease burden in individuals aged over 60 years has surpassed other conditions such as malignancies (15.1%) and chronic respiratory diseases (9.5%)46. Chronic kidney disease ranked second among chronic diseases in our SHAP analysis. Recent national data showed a continuous rise in its prevalence, from 6.7% in 1990 to 10.6% in 2019, highlighting its increasing public health impact among older adults47. Arthritis ranked third in the SHAP results, reflecting its high prevalence worldwide, with an estimated 22.9% of individuals aged 40 years and older affected48. This heavy burden likely manifests across multiple dimensions of aging, thereby reducing the likelihood of achieving successful aging.

Furthermore, logistic regression revealed significant associations between hypertension and “Absence of major diseases” module (OR = 0.366, 95% CI 0.275–0.487) and “Freedom from disability” module (OR = 0.649, 95% CI 0.451–0.938). The relation remained significant after adjusting the model (Table 4). It has been proved that hypertension can greatly increase the risk of various severe cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events, such as coronary artery disease and stroke, thus affecting the disease level of successful aging49. The strong association with the disease component suggests that hypertension may warrant consideration in future discussions on disease-related criteria for successful aging frameworks. Furthermore, the observed link between hypertension and disability is consistent with previous epidemiological findings, which consistently demonstrate that hypertension may contribute to physical disability among older adults50. Hypertension has been associated with increased risk of mobility limitations and difficulties in performing activities of daily living, potentially due to its role in exacerbating cardiovascular complications, stroke, and physical frailty, ultimately limiting functional independence and negatively impacting overall life quality51.

Moreover, kidney disease and arthritis were significantly associated with multiple components of successful aging in logistic models. Beyond their impact on the absence of major disease and disability, these two conditions showed strong links to mental health and cognitive functioning. In the adjusted models, kidney disease was associated with a markedly increased risk of depressive symptoms (OR = 3.914, 95% CI 2.267–6.725) and poorer cognitive status (OR = 0.513, 95% CI 0.311–0.850). Similarly, arthritis was linked to a higher likelihood of depressive symptoms (OR = 2.202, 95% CI 1.595–3.044) and reduced cognitive function (OR = 0.540, 95% CI 0.414–0.703). These findings underscore the broader psychological and neurological burden posed by chronic conditions, suggesting that their inclusion in successful aging assessments may contribute to a more comprehensive and realistic evaluation of aging outcomes52. From both physiological and psychosocial perspectives, kidney disease and arthritis may contribute to impaired mental and cognitive health in older adults53,54. The present findings indicate that individuals with kidney disease were significantly more likely to experience depressive symptoms and cognitive decline. Chronic kidney disease has been previously linked to systemic inflammation, uremic toxin accumulation, and disrupted neuroendocrine function, all of which may negatively impact brain health and emotional regulation55. Additionally, the frequent comorbidities and treatment burdens associated with renal dysfunction, including fatigue and polypharmacy, can lead to increased psychological stress and social withdrawal, thereby exacerbating depressive symptoms56. Similarly, arthritis is a leading cause of chronic pain and physical limitation in older adults, which may contribute to a reduced quality of life and elevated depressive risk57. Long-term pain and restricted mobility not only interfere with daily activities but also diminish opportunities for social engagement and cognitive stimulation, factors known to protect against cognitive decline58. Neurobiological research has also suggested that chronic inflammatory states common in arthritis may play a role in neuronal damage and cognitive impairment59. Besides, at the individual level, former SHAP waterfall plots further illustrated how these features influence model predictions differently across participants. In one true positive case, the model predicted successful aging with high confidence primarily due to the lack of major chronic diseases. It showed that not having hypertension, arthritis, and kidney disease were the dominant drivers contributing positively to the final prediction. In contrast, for one true negative case, the presence of these same diseases resulted in negative SHAP values, thereby lowering the predicted probability of successful aging. Taken together, these findings suggest that chronic conditions such as hypertension, kidney disease, and arthritis are associated with overall health status and may influence the likelihood of achieving successful aging.

In this study, sleep duration emerged as the most influential predictor of successful aging among all examined features, as demonstrated by the SHAP analysis (Fig. 4). Additionally, the ALE analysis revealed a nonlinear and complex association between sleep duration and the predicted probability of successful aging (Supplementary Fig. 2). Both the RCS analysis (Supplementary Fig. 3) and stratified logistic regression (Supplementary Table 3) further supported a nonlinear, inverted U-shaped association between sleep duration and the likelihood of achieving successful aging. Specifically, the odds of successful aging increased with sleep duration up to approximately 7.5 h, after which the odds gradually declined. Stratified analysis showed that individuals with < 4 h, 4–6 h, or ≥ 10 h of sleep had significantly lower odds of successful aging compared to those with 6–8 h of sleep. These findings are consistent with previous studies reporting similar patterns60. For example, a large-scale study demonstrated that compared to individuals with 7–8 h of sleep and no insomnia, those with long sleep duration (≥ 9 h) or insomnia had significantly lower odds of successful aging, and nonlinear dose–response analyses further confirmed an inverted U-shaped relationship between sleep duration and successful aging, with an inflection point around 8 h per day35,61. Collectively, our results and prior evidence suggest that both insufficient and excessive sleep are associated with a reduced likelihood of achieving successful aging in older adults.

In summary, our findings have some strengths and public health implications. Firstly, among the machine learning models evaluated, XGBoost showed comparatively balanced and robust performance across multiple metrics. Specifically, it achieved an F1 score of 0.781, a Recall of 0.984, and an AUC of 0.707. Notably, it also yielded the highest overall accuracy (0.692) and a relatively low Brier score (0.22). Sensitivity analyses further confirmed the model’s stability, showing that XGBoost maintained consistent performance under moderate changes in data composition. In addition, calibration analysis suggested that the model provides reasonably acceptable probability estimates, supporting its potential utility for population-level risk assessment and public health planning (Supplementary Fig. 1). This robustness supports its use as the core predictive model in our subsequent analyses. More importantly, by applying interpretable machine learning methods such as SHAP, we quantitatively evaluated the impact of chronic diseases on successful aging, offering both global and individual-level insights that traditional statistical models often fail to capture. Furthermore, ALE plots revealed complex non-linear relationships, particularly for sleep duration, which would have been obscured in conventional linear modeling. Beyond predictive accuracy, the model also provided meaningful domain-level insights. For example, kidney disease and arthritis were shown to have consistently negative impacts across multiple subdomains of successful aging, such as disease burden, disability, cognition, and depression. These findings provide empirical evidence on the public health relevance of prevalent but under-recognized chronic conditions, which may inform future refinement of successful aging criteria. In refining such criteria, policymakers face a trade-off: stricter definitions capture a smaller group with ideal aging, useful for precision interventions but likely underestimating prevalence, whereas more inclusive definitions identify a broader population for public health planning but at the cost of specificity. Future work should therefore explore alternative definitions and conduct sensitivity analyses to evaluate their impact on prevalence estimates and intervention strategies. Finally, by mapping the associations between specific diseases and the five core components of successful aging, we provided evidence that may inform future research on targeted strategies to support aging populations, especially among individuals with chronic conditions. This work thus offers valuable direction for both individual-level decision-making and population-level public health strategies in aging societies.

This study has several limitations. First, the cross-sectional design limits our ability to draw causal inferences between chronic diseases and successful aging62. Although propensity score matching was used to reduce baseline imbalance, this approach does not address temporality, and the observed associations remain vulnerable to issues such as reverse causality. Therefore, our findings should be interpreted as correlations rather than causal effects, and they should not be taken to imply that modifying these chronic diseases will necessarily lead to improved aging outcomes. Second, key variables such as health status, depression status, and social participation were based on self-reports, which are susceptible to recall and social desirability biases. These biases may lead to misclassification or underreporting of symptoms and behaviors, potentially affecting the observed associations. Third, despite adjusting for a wide range of covariates, the possibility of residual confounding cannot be ruled out. Factors such as early-life adversity, environmental exposures, or unmeasured genetic risks beyond APOE status may still influence the observed associations63. Fourth, while our model identified several major predictors of successful aging, some chronic diseases, including digestive diseases, liver disease, and dyslipidemia, exhibited relatively low SHAP values, suggesting limited contribution in this cohort. These findings should be interpreted with caution, as the predictive impact of these conditions may vary across different populations or study settings. Fifth, our sample selection included only participants who were not followed longitudinally in the CHARLS cohort. While this approach allowed for a consistent cross-sectional analysis, it may introduce selection bias and limit the generalizability of our findings to broader elderly populations. Future longitudinal studies incorporating more objective data sources are warranted to validate and extend these findings.

Conclusion

In this study, we applied interpretable machine learning methods to explore the association between chronic diseases and successful aging in older Chinese adults. Among the models tested, XGBoost was selected for further interpretation and prediction tasks. SHAP interpretation and logistic regression analysis revealed that kidney disease and arthritis were strongly associated with cognitive decline and depressive symptoms, while hypertension was primarily linked to functional limitations and disability. These findings may inform future research and public health discussions on the early identification and management of chronic conditions in aging populations. They also suggest that current definitions of successful aging may warrant reconsideration to better reflect the influence of prevalent chronic diseases.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the website of CHARLS at https://charls.pku.edu.cn/en.

Code availability

The scripts used in the analyses are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Cheng, X. et al. Population ageing and mortality during 1990–2017: A global decomposition analysis. PLoS Med. 17(6), e1003138 (2020).

Rishworth, A. & Elliott, S. J. Global environmental change in an aging world: The role of space, place and scale. Soc. Sci. Med. 227, 128–136 (2019).

The, L. Population ageing in China: Crisis or opportunity?. Lancet 400(10366), 1821 (2022).

Lobanov-Rostovsky, S. et al. Growing old in China in socioeconomic and epidemiological context: Systematic review of social care policy for older people. BMC Public Health 23(1), 1272 (2023).

Global Burden of Disease Study C. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 386(9995), 743–800 (2015).

Adeloye, D. et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of, and risk factors for, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in 2019: A systematic review and modelling analysis. Lancet Respir. Med. 10(5), 447–458 (2022).

Liu, T. et al. Association between sarcopenia and new-onset chronic kidney disease among middle-aged and elder adults: Findings from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study. BMC Geriatr. 24(1), 134 (2024).

Chen, S. et al. The global economic burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease for 204 countries and territories in 2020–50: A health-augmented macroeconomic modelling study. Lancet Glob. Health 11(8), e1183–e1193 (2023).

Dunn, R. M., Busse, P. J. & Wechsler, M. E. Asthma in the elderly and late-onset adult asthma. Allergy 73(2), 284–294 (2018).

Robles, N. R. & Macias, J. F. Hypertension in the elderly. Cardiovasc. Hematol. Agents Med. Chem. 12(3), 136–145 (2015).

Liu, R., He, W. B., Cao, L. J., Wang, L. & Wei, Q. Association between chronic disease and depression among older adults in China: The moderating role of social participation. Public Health 221, 73–78 (2023).

Griffith, L. E. et al. Functional disability and social participation restriction associated with chronic conditions in middle-aged and older adults. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 71(4), 381–389 (2017).

Ma, Y., Xiang, Q., Yan, C., Liao, H. & Wang, J. Relationship between chronic diseases and depression: The mediating effect of pain. BMC Psychiatry 21(1), 436 (2021).

Kim, H. J., Min, J. Y. & Min, K. B. Successful aging and mortality risk: the Korean longitudinal study of aging (2006–2014). J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 20(8), 1013–1020 (2019).

Rowe, J. W. & Kahn, R. L. Human aging: Usual and successful. Science 237(4811), 143–149 (1987).

Friedman, S. M. Lifestyle (medicine) and healthy aging. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 36(4), 645–653 (2020).

Juan, S. M. A. & Adlard, P. A. Ageing and cognition. Subcell Biochem. 91, 107–122 (2019).

Liu, Y. et al. Successful aging rates of global older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 26(6), 105334 (2024).

Brown, A. Economic policy makers need to take health seriously. BMJ 381, 1164 (2023).

Urtamo, A., Jyvakorpi, S. K. & Strandberg, T. E. Definitions of successful ageing: A brief review of a multidimensional concept. Acta Biomed. 90(2), 359–363 (2019).

Maresova, P. et al. Consequences of chronic diseases and other limitations associated with old age: A scoping review. BMC Public Health 19(1), 1431 (2019).

Wieczorek, M. et al. Association between multiple chronic conditions and insufficient health literacy: cross-sectional evidence from a population-based sample of older adults living in Switzerland. BMC Public Health 23(1), 253 (2023).

Okland, I., Gjessing, H. K., Grottum, P. & Eik-Nes, S. H. Biases of traditional term prediction models: Results from different sample-based models evaluated on 41 343 ultrasound examinations. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 36(6), 728–734 (2010).

Sabatini, S. et al. Successful Aging and Subjective Aging: Toward a Framework to Research a Neglected Connection. Gerontologist 65(1), gnae051 (2024).

Zhao, Y., Hu, Y., Smith, J. P., Strauss, J. & Yang, G. Cohort profile: The China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). Int. J. Epidemiol. 43(1), 61–68 (2014).

Luo, H. et al. Association between obesity status and successful aging among older people in China: Evidence from CHARLS. BMC Public Health 20(1), 767 (2020).

Katz, S., Ford, A. B., Moskowitz, R. W., Jackson, B. A. & Jaffe, M. W. Studies of illness in the aged. The index of Adl: A standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA 185, 914–919 (1963).

Pashmdarfard, M. & Azad, A. Assessment tools to evaluate activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) in older adults: A systematic review. Med. J. Islam Repub. Iran. 34, 33 (2020).

Fong, T. G. et al. Telephone interview for cognitive status: Creating a crosswalk with the mini-mental state examination. Alzheimers Dement. 5(6), 492–497 (2009).

Andresen, E. M., Malmgren, J. A., Carter, W. B. & Patrick, D. L. Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale). Am J Prev Med. 10(2), 77–84 (1994).

Lewinsohn, P. M., Seeley, J. R., Roberts, R. E. & Allen, N. B. Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) as a screening instrument for depression among community-residing older adults. Psychol. Aging 12(2), 277–287 (1997).

Qian, J., Li, N. & Ren, X. Obesity and depressive symptoms among Chinese people aged 45 and over. Sci. Rep. 7, 45637 (2017).

Nakagawa, T., Cho, J. & Yeung, D. Y. Successful aging in East Asia: Comparison among China, Korea, and Japan. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 76(Suppl 1), S17–S26 (2021).

Hanahan, D. & Weinberg, R. A. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell 144(5), 646–674 (2011).

Tian, L., Ding, P., Kuang, X., Ai, W. & Shi, H. The association between sleep duration trajectories and successful aging: A population-based cohort study. BMC Public Health 24(1), 3029 (2024).

Greener, J. G., Kandathil, S. M., Moffat, L. & Jones, D. T. A guide to machine learning for biologists. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 23(1), 40–55 (2022).

Rainio, O., Teuho, J. & Klen, R. Evaluation metrics and statistical tests for machine learning. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 6086 (2024).

Shehab, E., Nayel, H. & Taha, M. OPTUNA optimization for predicting chemical respiratory toxicity using ML models. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 39(1), 21 (2025).

Qi, X. et al. Machine learning and SHAP value interpretation for predicting comorbidity of cardiovascular disease and cancer with dietary antioxidants. Redox Biol. 79, 103470 (2025).

Luo, L. et al. Identifying the most critical predictors of workplace violence experienced by junior nurses: An interpretable machine learning perspective. J. Nurs. Manag. 2025, 5578698 (2025).

Xu, S. et al. aplot: Simplifying the creation of complex graphs to visualize associations across diverse data types. Innovation 6, 100958 (2025).

Phelan, E. A. & Larson, E. B. “Successful aging”–where next?. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 50(7), 1306–1308 (2002).

Martin, P. et al. Defining successful aging: A tangible or elusive concept?. Gerontologist 55(1), 14–25 (2015).

Liang, D. et al. Perspective: Global burden of iodine deficiency: Insights and projections to 2050 using XGBoost and SHAP. Adv Nutr. 16(3), 100384 (2025).

Wang, K. et al. Interpretable prediction of 3-year all-cause mortality in patients with heart failure caused by coronary heart disease based on machine learning and SHAP. Comput Biol Med. 137, 104813 (2021).

Prince, M. J. et al. The burden of disease in older people and implications for health policy and practice. Lancet 385(9967), 549–562 (2015).

Li, Y. et al. Temporal trends in prevalence and mortality for chronic kidney disease in China from 1990 to 2019: An analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Clin. Kidney J. 16(2), 312–321 (2023).

Cui, A. et al. Global, regional prevalence, incidence and risk factors of knee osteoarthritis in population-based studies. EClinicalMedicine. 29–30, 100587 (2020).

Doyle, A. E. Hypertension and vascular disease. Am. J. Hypertens. 4(2 Pt 2), 103S-S106 (1991).

Buonacera, A., Stancanelli, B. & Malatino, L. Stroke and hypertension: An appraisal from pathophysiology to clinical practice. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 17(1), 72–84 (2019).

Bauer, U. E., Briss, P. A., Goodman, R. A. & Bowman, B. A. Prevention of chronic disease in the 21st century: Elimination of the leading preventable causes of premature death and disability in the USA. Lancet 384(9937), 45–52 (2014).

Lorenzo, E. C., Kuchel, G. A., Kuo, C. L., Moffitt, T. E. & Diniz, B. S. Major depression and the biological hallmarks of aging. Ageing Res Rev. 83, 101805 (2023).

Carswell, C. et al. Chronic kidney disease and severe mental illness: A scoping review. J. Nephrol. 36(6), 1519–1547 (2023).

Black, P. Caring for stoma patients with arthritis and mental incapacities. Br. J. Community Nurs. 20(10), 487–492 (2015).

Gao, L. et al. STING/ACSL4 axis-dependent ferroptosis and inflammation promote hypertension-associated chronic kidney disease. Mol. Ther. 31(10), 3084–3103 (2023).

Palmer, S. et al. Prevalence of depression in chronic kidney disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Kidney Int. 84(1), 179–191 (2013).

Nerurkar, L., Siebert, S., McInnes, I. B. & Cavanagh, J. Rheumatoid arthritis and depression: An inflammatory perspective. Lancet Psychiatry 6(2), 164–173 (2019).

Bushnell, M. C., Ceko, M. & Low, L. A. Cognitive and emotional control of pain and its disruption in chronic pain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 14(7), 502–511 (2013).

Leigh, S. J. & Morris, M. J. Diet, inflammation and the gut microbiome: Mechanisms for obesity-associated cognitive impairment. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 1866(6), 165767 (2020).

Henry, A. et al. The relationship between sleep duration, cognition and dementia: A Mendelian randomization study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 48(3), 849–860 (2019).

Liu, Y. et al. Healthy sleep without insomnia may go beyond sleep duration for achieving successful aging in Chinese older adults: A cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 25(1), 386 (2025).

Edwards, D. C., Bowes, C. C., Penlington, C. & Durham, J. Temporomandibular disorders and dietary changes: A cross-sectional survey. J. Oral Rehabil. 48(8), 873–879 (2021).

Serrano-Pozo, A., Das, S. & Hyman, B. T. APOE and Alzheimer’s disease: Advances in genetics, pathophysiology, and therapeutic approaches. Lancet Neurol. 20(1), 68–80 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We thank all participants, related workers in questionnaires making, data creating and cleaning, depositors and founders of CHARLS.

Funding

This research is supported by Research on Predicting the Risk of Physical and Mental Comorbidities in Middle-aged and Elderly-Taking Diabetes and Depression and the 13th Five-Year Plan of Guangdong Province for Philosophy and Social Sciences (GD20XGL42).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NH designed the study, analyzed the data, and collaborated in writing paper. Xc X assisted with the study conceptualization and editing of the manuscript. Fy H collaborated in project administration. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All respondents gave informed written consent prior to the interview, and ethical approval for the collection of human subject data was obtained, which was updated annually at the Peking University Institutional Review Board (IRB00001052-11015). No additional ethical approval is required for approved data users. All methods of this study were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

He, N., Xu, X., Wang, H. et al. Revisiting successful aging through a machine learning approach to quantifying the influence of chronic diseases. Sci Rep 15, 40206 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24154-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24154-w