Abstract

The COVID-19 epidemic has posed a considerable challenge to the worldwide economy and public health, underscoring the crucial demand for developing effective antiviral medications. The SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Mpro) is a vital enzyme for antiviral drugs because of its fundamental function in viral reproduction. Nirmatrelvir (PF-07321332), a nitrile-based covalent ligand of Mpro, has garnered significant interest because it demonstrates additive efficacy when co-administered with ritonavir and is known as Paxlovid. Herein, forty-five nirmatrelvir analogs collected from the PubChem database were mined against Mpro utilizing covalent docking computations. Initially, the reliability of the AutoDock4.2.6 software in predicting Mpro-ligand binding modes was validated based on accessible experimental data. Nirmatrelvir analogs with binding scores lower than nirmatrelvir (calc. −13.3 kcal/mol) were advanced for molecular dynamics simulations (MDS), accompanied by binding energy assessments performed via the MM-GBSA approach. Based on MM-GBSA//100 ns MDS, PubChem-162-396-453, PubChem-162-396-449, and PubChem-162-396-448 exhibited superior binding affinities with ΔGbinding values of −49.7, −46.3, and −44.9 kcal/mol, respectively, compared to nirmatrelvir (ΔGbinding = −40.7 kcal/mol). The identified analogs demonstrated significant structural and energetic stability within Mpro throughout 100 ns MDS. Evaluations of their drug-likeness and pharmacokinetic properties disclosed desirable oral bioavailability. The in-silico outcomes suggested that the identified analogs unveiled high potency as Mpro inhibitors, highlighting the necessity for follow-up in-vitro/in-vivo evaluations to assess their efficacy as anti-COVID-19 agents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), a highly transmissible illness caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), was initially identified in Wuhan, China, in December 2019 1,2. The World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a pandemic on 12 March 2020 due to its swift international transmission and associated mortality3. By September 2023, the disease had resulted in over 770 million confirmed cases and approximately 7.7 million deaths worldwide, necessitating the pressing demand for effective prevention and treatment strategies4. SARS-CoV-2 is an enveloped, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus of the beta-coronavirus genus, capable of infecting both animals and humans and causing respiratory complications5. While several vaccines have achieved global dissemination, continued research for identifying antiviral agents to fight COVID-19 is warranted. This necessity arises from the continued emergence of more transmissible or immune-evasive genetic variants, as well as increasing concerns over viral resistance to existing treatments6.

The main protease (Mpro) of SARS-CoV-2 is an essential enzyme participating in viral replication, transcriptional control, and polyprotein processing, thereby representing a significant target for antiviral therapeutic strategies7,8. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, considerable endeavors —both experimental and computational— have focused on drug repurposing to identify compounds with clinical potential against M[pro9–14. Several of these repurposed agents, including lopinavir, remdesivir, umifenovir, favipiravir, and ritonavir, have attracted attention and entered various stages of clinical evaluation for COVID-19 treatment15,16. Recent studies have reported more than 50 non-covalent and covalent Mpro inhibitors; covalent inhibitors usually form bonds with CYS145, while non-covalent inhibitors bind through weaker interactions in the binding pocket17. Among the covalent inhibitors, nirmatrelvir has emerged as one of the most potent and clinically relevant candidates against Mpro18. In December 2021, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) authorized the co-administration of ritonavir and nirmatrelvir as a combination therapy for the treatment of COVID-19 19. These two agents constitute the oral antiviral formulation Paxlovid20. Notably, Paxlovid was the initial orally administered coronavirus-specific Mpro ligand to receive FDA approval21. Nirmatrelvir is structurally derived from a peptidomimetic scaffold based on the inhibitor ML1000 22, in which the α-ketoamide warhead of ML1000 was replaced with a nitrile group, acting as a Michael acceptor targeting the catalytic cysteine of M[pro23. The reversible covalent inhibition mechanism between nirmatrelvir and Mpro involves a nucleophilic attack by the thiol group of CYS145 on the electrophilic nitrile group of nirmatrelvir, leading to the establishment of a thioimidate adduct24,25. Given the ongoing need for effective treatments for SARS-CoV-2 and its evolving variants, this study aims to discover further potent covalent inhibitors targeting Mpro, building on the mechanistic insights provided by nirmatrelvir.

Herein, a library of forty-five nirmatrelvir analogs collected from the PubChem database was investigated as potential Mpro inhibitors employing advanced computational techniques. Initially, nirmatrelvir analogs were screened via reversible covalent docking to assess their docking scores and binding interactions with Mpro. The top-scoring analogs were thereafter subjected to 100 ns molecular dynamics simulations (MDS), and their binding energies were estimated through the application of the MM-GBSA approach. Furthermore, the pharmacokinetic, drug-likeness, and toxicity characteristics were evaluated for the most potent analogs. Figure 1 provides a schematic representation of the in-silico workflow employed for screening nirmatrelvir analogs against Mpro, outlining the key steps in the virtual screening process. Based on these in-silico findings, the identified nirmatrelvir analogs emerged as promising candidates deserving of additional in-vitro/in-vivo studies to combat COVID-19.

Computational methodology

Enzyme preparation

In this study, the high-resolution crystal structure of Mpro (PDB accession code: 7VLP; resolution: 1.50 Å26) was utilized as the structural template for all computational estimations. For enzyme preparation purposes, water molecules, ligand, and ions were excluded. Residue protonation states were carefully determined27, and hydrogen atoms absent in the crystal structure were subsequently introduced using the H++ web server with the following parameters: pH = 7, internal/external dielectric (10/80), and salinity = 0.15.

Covalent inhibitors preparation

To explore potential lead compounds against COVID-19, a systematic scaffold-based search was executed in the PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov), leveraging the chemical core structure of nirmatrelvir as the primary query molecule. A total of one hundred and twenty nirmatrelvir analogs were retrieved in SDF format. After deduplication utilizing the International Chemical Identifier key (InChIKey), a curated set of forty-five analogs was obtained. Omega2 software was employed to generate 3D structures of the collected analogs28,29. Energy minimization for all generated structures was performed utilizing Merck Molecular Force Field 94 (MMFF94S) implemented in the SZYBKI software30. Atomic charges were computed utilizing the Gasteiger-Marsili method31.

Covalent docking

Covalent docking serves as a key computational tool, highlighting the detailed interactions between covalently attached ligands and their protein targets, thus creating new opportunities for structure-based design and improvement32. For reversible covalent docking computations against Mpro, AutoDock4.2.6 software was applied with a flexible side chain configuration to enhance binding site adaptability33. In compliance with the AutoDock4.2.6 protocol, the PDB file of Mpro was converted into the PDBQT file34. The default parameters of docking computations were used, except for the number of genetic algorithm (GA) runs and maximum number of energy evaluations (eval), which were set to 250 and 25,000,000, respectively. The latter changes in docking parameters were adjusted to ensure thorough sampling of the conformational space. A docking grid with dimensions of 40 Å × 40 Å × 40 Å, with a grid spacing of 0.375 Å. The grid box was centered at coordinates (x = −20.111, y = −11.153, and z = 2.684) to encompass the binding site.

Molecular dynamics simulations (MDS)

MDS of the top-scoring nirmatrelvir analogs complexed with Mpro was conducted using the AMBER20 software35. The detailed MDS protocols are described elsewhere36,37,38,39. General AMBER force field (GAFF2) was utilized for the nirmatrelvir analogs parameterization40. Mpro underwent characterization through the AMBER14SB force field, a reliable protein force field41. Acetyl and methylamide groups were employed to cap the CYS145-analog complexes. For the capped CYS145-analogs, geometrical optimization was accomplished at the B3LYP/6-31G* level utilizing Gaussian09 software37. Based on the optimized capped CYS145-analogs, atomic charges were derived utilizing the restrained electrostatic potential (RESP) approach42. Each docked analog-Mpro complex was subsequently solvated within a truncated octahedral box containing TIP3P water molecules, extending 12.0 Å beyond the solute in all directions. To achieve physiological ionic strength, the solvated complexes were neutralized and supplemented with sodium or chloride ions to a final concentration of 0.15 M NaCl. Energy minimization was executed in two stages: an initial 5000 steps using the steepest descent method, accompanied by refinement with the conjugate gradient algorithm. The energetically minimized complexes were incrementally heated up to 310 K throughout 50 ps under constant volume conditions, with a weak positional restraint of 10 kcal.mol−1.Å−2 applied to the protein backbone throughout the heating phase. A 10 ns equilibration phase was then carried out to stabilize the investigated complexes. Production runs were finally conducted under NPT conditions for 25 and 100 ns, with trajectories saved every 10 ps. Electrostatic interactions were treated utilizing the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) approach43, and a 12 Å cutoff was used to model Lennard-Jones interactions. System temperature was maintained at 298 K using a Langevin thermostat (collision frequency of 1.0 ps−1), while pressure control was achieved using a Berendsen barostat with a 2.0 ps relaxation time44. The SHAKE algorithm constrained hydrogen-involving bonds, enabling the use of a 2.0 fs integration timestep45. All MDSs were executed using the PMEMD.CUDA version available in AMBER20 software. Furthermore, visualization of analog-Mpro interactions was implemented using BIOVIA Materials Studio46.

MM-GBSA binding energy

The binding energies (ΔGbinding) of the identified nirmatrelvir analogs bound to Mpro were estimated using the molecular mechanics-generalized Born surface area (MM-GBSA) approach47. The polar solvation energy component was calculated employing the modified GB model with an igb value of 2.0 48. Binding energies were calculated from decorrelated snapshots extracted along the MD trajectories, employing the following equation:

where the G term is:

E MM stands for molecular mechanics (MM) energy in the gas phase, while Gsolv denotes the solvation-free energy. The internal energy term (Eint) accounts for bonded contributions, including bond stretching, angle bending, and dihedral interactions. Electrostatic and van der Waals contributions are denoted by Eele and EvdW, respectively. For all investigated complexes, the entropic contribution was omitted from the binding energy calculations owing to the high computational cost related to its estimation49,50. Previous studies have reported that excluding the entropic term exerts a minimal effect on the MM-GBSA binding energy evaluations51.

Principal component analysis (PCA)

PCA is carried out to evaluate the covariance of atomic movements and the dynamic behaviour of protein loops52. Trajectory processing was performed with the PTRAJ module of the AMBER20 software package, in which water solvent molecules and neutralizing ions were removed. Subsequently, the extracted trajectories were aligned with their corresponding fully optimized conformations to eliminate overall translational and rotational motions. Covariance matrices of the Cα atomic fluctuations were then generated, and the first two principal components (PC1 and PC2) were calculated. PCA was conducted on 10,000 trajectory frames for each Cα atom for both the apo-Mpro and the ligand-bound systems. The first two eigenvectors of the covariance matrices corresponded to the extracted PC1 and PC2.

Physicochemical features

The physicochemical suitability of the identified nirmatrelvir analogs was further evaluated in accordance with Lipinski’s rule of five (Ro5), with molecular descriptors calculated through the Molinspiration platform (http://www.molinspiration.com). This rule is a standard predictor for evaluating the oral bioavailability of drug-like compounds53,54. For each investigated analog, the following molecular features were estimated: molecular weight (MW), H-bond acceptors/donors (HBA/HBD), topological polar surface area (TPSA), and octanol-water partition coefficient (MLogP), providing insights into the potential druggability for these analogs as Mpro inhibitors.

Pharmacokinetic and toxicity characteristics

Utilizing the pkCSM online tool, the ADMET features for the most potent nirmatrelvir analogs were anticipated, covering absorption (A), distribution (D), metabolism (M), excretion (E), and toxicity (T)55. For absorption (A), the Caco-2 permeability and log Kp (skin permeability) were evaluated. Distribution (D) was identified according to the log BB (blood-brain barrier) permeability and VDss (steady-state volume of distribution). Metabolism (M) and excretion (E) were estimated based on CYP3A4 inhibitor/substrate and total clearance, respectively. Eventually, the toxicity (T) was evaluated by considering AMES toxicity factors and skin sensitization predictions.

Results and discussion

Covalent docking assessment

Prior to covalent docking of the assembled nirmatrelvir analogs, the accuracy of the AutoDock4.2.6 software prediction of the nirmatrelvir-Mpro binding mode was evaluated. According to the literature, the RMSD value between the predicted binding pose and the experimentally resolved pose should be less than 2.0 Å56,57. Based on the redocking calculation of nirmatrelvir towards the binding site of Mpro, the estimated RMSD between the experimental and predicted poses was found to be 0.45 Å. Besides, nirmatrelvir unveiled a promising binding affinity towards Mpro, yielding a favorable covalent docking score with a value of −13.3 kcal/mol. The great binding affinity of nirmatrelvir with Mpro was attributed to the exhibition of a reversible covalent bond between the nitrile carbon of nirmatrelvir and the sulfur atom of CYS145 (1.76 Å) (Fig. 2). Additionally, nirmatrelvir had the ability to establish five H-bonds with proximal amino acids inside the binding pocket of Mpro. More precisely, an H-bond was observed between the NH of the pyrrolidine-one ring and the carbonyl of PHE140 (2.81 Å). As well, an H-bond was exhibited between the imine group and the NH of GLY143 (2.76 Å). The NH of N-(cyanomethyl) acetamide established an H-bond with the carbonyl of HIS164 (1.85 Å). Besides, the amide nitrogen and the NH of the pyrrolidine-one ring shared in the establishment of two H-bonds with the carbonyl and the oxygen of GLU166 (1.84 and 2.13 Å, respectively). These findings highlighted the effectiveness of the AutoDock4.2.6 software in predicting the correct binding modes of Mpro inhibitors.

Virtual screening

At the outset of drug discovery, virtual screening is a widely adopted technique for the effective identification of putative bioactive inhibitors in a high-throughput manner58,59. Therefore, forty-five nirmatrelvir analogs were screened against Mpro utilizing a covalent docking technique, with estimated scores listed in Table S1. Among the screened nirmatrelvir analogs, fourteen nirmatrelvir analogs displayed covalent docking scores more favorable (i.e., less) than nirmatrelvir (calc. −13.3 kcal/mol). The 2D and 3D molecular interaction profiles for these top-scoring analogs complexed with Mpro are depicted in Figure S1. Table 1 lists the 2D chemical structures, covalent docking scores, and molecular interactions of the top potent nirmatrelvir analogs. All fourteen analogs exhibited a covalent bond via the interaction of the nitrile carbon of each analog with the sulfur atom of CYS145, as observed from Table 1 and Figure S1, where most selected analogs formed essential H-bonds with critical binding pocket residues, including HIS41, PHE140, ASN142, GLY143, HIS164, and GLU166. In addition to H-bonding, pi-based, vdW, and hydrophobic interactions were also detected between the identified nirmatrelvir analogs and the most fundamental residues within the Mpro binding pocket, further contributing to their binding affinity.

Notably, three promising analogs, namely PubChem-162-396-453, PubChem-162-396-449, and PubChem-162-396-448, were identified based on their favorable MM-GBSA binding energies over a 100 ns MDS, as elaborated in the following sections. Figure 3 illustrates both 2D and 3D molecular interactions of the predicted binding poses of PubChem-162-396-453, PubChem-162-396-449, and PubChem-162-396-448 within the Mpro binding pocket. Importantly, the nitrile carbon of each analog formed a reversible covalent bond with the sulfur atom of CYS145 (1.49, 1.47, and 1.48 Å, respectively) (Fig. 3).

PubChem-162-396-453 exhibited strong binding affinity toward Mpro, as indicated by a covalent docking score of −15.3 kcal/mol, forming six H-bonds with key residues within the Mpro binding pocket (Table 1). Precisely, the NH and carbonyl of the pyrrolidine-2-one ring exhibited two H-bonds with the carbonyl of PHE140 (2.72 Å) and NH of HIS163 (1.99 Å). Besides, the NH of the amide group displayed an H-bond with the carbonyl of HIS164 (1.75 Å). Additionally, three H-bonds were observed between the NH of the 2,2,2-trifluoro-N-methylacetamide group, the carbonyl of (R)-3-amino-4-cyclobutylbutan-2-one, and the NH of the pyrrolidine-2-one ring with the C=O, NH, and C=O of the carboxylate group of the GLU166 residue (1.91, 1.92, and 1.99 Å, respectively).

PubChem-162-396-449 unveiled the second-highest binding affinity towards Mpro, with a covalent docking score of −14.9 kcal/mol. PubChem-162-396-449 formed eight H-bonds with key residues of the Mpro binding pocket (Table 1). Scrutinizing the binding pose highlighted that the C=O exhibited an H-bond with the NH of HIS41 (2.67 Å). The NH of pyrrolidine-dione was involved in forming two H-bonds with the C=O of PHE140 (2.84 Å) and the oxygen atom of GLU166 (1.95 Å) (Fig. 3). The C=O of pyrrolidine-dione displayed an H-bond with the NH of HIS163 (1.97 Å). Besides, the NH of (1R,2S,5S)-6,6-dimethyl-3-azabicyclo[3.1.0]hexane-2-carboxamide exhibited an H-bond with the C=O of HIS164 (2.15 Å) (Fig. 3). The NH of 2,2,2-trifluoro-N-methylacetamide and the hydroxyl group formed two H-bonds with the carbonyl of GLU166 (2.12, 2.29 Å). As well, the C=O group displayed an H-bond with the NH of GLU166 (2.36 Å).

PubChem-162-396-448, also known as nirmatrelvir metabolite M3, mainly acts as an oxidative metabolite and inhibits Mpro with a ki value of 3.0 nM, comparable to that of nirmatrelvir (ki = 3.11 nM)60. PubChem-162-396-448 exhibited a favorable covalent docking score of −14.7 kcal/mol against Mpro, revealing eight H-bonds with adjacent residues within the binding pocket (Table 1). Analyzing the docking pose of PubChem-162-396-448 within the Mpro binding pocket demonstrated that the C=O established an H-bond with the NH of HIS41 (2.67 Å). The NH and C=O of the pyrrolidine-one ring showed two H-bonds with the C=O of PHE140 (2.79 Å) and NH of HIS163 (1.87 Å). The NH of the amide group exhibited an H-bond with the C=O of HIS164 (2.19 Å). The NH of the pyrrolidine-one ring displayed an H-bond with the C=O of GLU166 (2.01 Å). The NH of 2,2,2-trifluoro-N-methylacetamide and the OH group exhibited two H-bonds with the C=O of GLU166 (2.18, 2.35 Å). Besides, the C=O of (1R,5S)-6,6-dimethyl-3-azabicyclo[3.1.0]hexane-3-carbaldehyde established an H-bond with the NH of GLU166 (2.36 Å) (Fig. 3).

Molecular dynamics simulations

To inspect the steadiness and characterize the binding interactions, MDS and binding energy computations were executed on the top-scoring nirmatrelvir analogs bound to Mpro. Consequently, fourteen potent nirmatrelvir analogs with covalent docking scores lower compared to nirmatrelvir (calc. −13.3 kcal/mol) were nominated and advanced for MDS. To minimize computational cost and time, short MDS over 25 ns were conducted for these fourteen analogs complexed with Mpro, and the corresponding binding energies were computed (Table S2). As data registered in Table S2, three out of fourteen analogs demonstrated ∆Gbinding values less than nirmatrelvir (calc. −44.2 kcal/mol). To obtain more accurate estimates of binding energies, the MDS of the three most promising nirmatrelvir analogs bound to Mpro was elongated to 100 ns, followed by MM-GBSA calculations (Fig. 4). It is noteworthy that the estimated binding affinities for the identified analog-Mpro complexes showed no appreciable difference between the 25 and 100 ns MDS. Derived from the computed binding energies over 100 ns MDS, PubChem-162-396-453, PubChem-162-396-449, and PubChem-162-396-448 displayed ∆Gbinding values of −49.7, −46.3, and −44.9 kcal/mol, respectively, compared to nirmatrelvir (calc. −40.7 kcal/mol) against Mpro. Although the in-silico results suggested favorable binding and stability profiles, further experimental validation through in-vitro/in-vivo studies would be necessary to confirm the efficacy and safety of the identified analogs and to support their advancement in the drug discovery pipeline.

To further grasp the predominant interactions of the identified nirmatrelvir analogs with Mpro, the binding energies were subjected to energy decomposition analysis (Fig. 5). Based on the decomposition results, the Eele was observed to be a considerable participant in inhibitor-Mpro binding energy with average values of −83.3, −83.4, −81.8, and −79.4 kcal/mol for PubChem-162-396-453, PubChem-162-396-449, PubChem-162-396-448, and nirmatrelvir complexed with Mpro, respectively. Additionally, ∆EvdW interactions also played a major role in the binding of PubChem-162-396-453, PubChem-162-396-449, PubChem-162-396-448, and nirmatrelvir with Mpro, with average values of −60.1, −58.3, −55.1, and −51.1 kcal/mol, respectively. Upon these outcomes, the Eele is about one and a half times as strong as the EvdW.

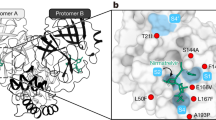

To gain deeper insights into nirmatrelvir analog-Mpro interactions and the role of key binding pocket residues, total ∆Gbinding values were decomposed on a per-residue basis using the MM-GBSA approach (Fig. 6a). The decomposition analysis focused on amino acids with a ∆Gbinding contribution of greater than −0.50 kcal/mol. Key interacting residues, including HIS41, PHE140, ASN142, CYS145, HIS164, MET165, and GLU166 were identified as common contributors in PubChem-162-396-453-, PubChem-162-396-449-, PubChem-162-396-448-, and nirmatrelvir-Mpro complexes. Notably, all complexes exhibited highly similar interaction patterns with these residues, suggesting a conserved binding mode. Among the participating residues, MET165 had the most substantial contribution to ΔGbinding, with values of −3.7, −3.5, −3.4, and −3.3 kcal/mol for PubChem-162-396-453-, PubChem-162-396-449-, PubChem-162-396-448-, and nirmatrelvir-Mpro complexes, respectively (Fig. 6a). The second-largest contributing residue was GLU166, with ∆Gbinding values of −3.0, −2.9, −2.8, and −3.0 kcal/mol for PubChem-162-396-453-, PubChem-162-396-449-, PubChem-162-396-448-, and nirmatrelvir-Mpro complexes, respectively.

Furthermore, the average structures for PubChem-162-396-453, PubChem-162-396-449, PubChem-162-396-448, and nirmatrelvir over the 100 ns MDS were extracted and illustrated in Figure 6b. These average structures maintained a binding pose closely resembling their initial docked configurations, including a covalent bond and multiple H-bonds with key Mpro residues. Notably, an H-bond observed between HIS41 and PubChem-162-396-449 in the docked pose was absent in the 100 ns average structure, highlighting the importance of MDS in accurately capturing nirmatrelvir analog-Mpro interactions and refining initial docking predictions.

Post-MD analyses

The structural integrity and energetic profile for PubChem-162-396-453, PubChem-162-396-449, and PubChem-162-396-448 complexed with Mpro were assessed using a series of post-MD analyses conducted over 100 ns MDS. The results were compared with those of the nirmatrelvir (co-crystallized ligand) bound to Mpro. Post-MD analyses included assessments of binding affinity per-trajectory, root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) and fluctuation (RMSF), distance of center-of-mass (CoM), number of H-bonds, radius of gyration (Rg), and principal component analysis (PCA).

Binding affinity per-trajectory

The overall energetic constancy for PubChem-162-396-453-, PubChem-162-396-449-, PubChem-162-396-448-, and nirmatrelvir-Mpro complexes was estimated over the 100 ns MDS (Fig. 7a). An intriguing aspect of Figure 7a was the general stabilities for PubChem-162-396-453, PubChem-162-396-449, PubChem-162-396-448, and nirmatrelvir bound to Mpro with average ΔGbinding values of −49.7, −46.3, −44.9, and −40.7 kcal/mol, respectively. The most attention-grabbing result of this analysis was that all complexes preserved their stability throughout the simulation period.

Distance of CoM

To further verify the spatial stability of the analog-Mpro complexes, the CoM distance between each analog and CYS145 was calculated over the 100 ns MDS. Figure 7b highlights that PubChem-162-396-453, PubChem-162-396-449, PubChem-162-396-448, and nirmatrelvir remained consistently positioned within the Mpro binding pocket, with average CoM distances of 8.6, 8.5, 8.6, and 8.4 Å, respectively. These findings suggested strong and persistent interactions between the identified analogs and Mpro throughout the simulation time.

RMSD analysis

To track the conformational change for the PubChem-162-396-453-, PubChem-162-396-449-, PubChem-162-396-448-, and nirmatrelvir-Mpro complexes, RMSD analysis was assessed throughout the 100 ns MDS period (Fig. 7c). As presented in Figure 7c, the mean RMSD values were 0.19, 0.17, 0.18, and 0.18 nm for PubChem-162-396-453-, PubChem-162-396-449-, PubChem-162-396-448-, and nirmatrelvir-Mpro complexes, respectively. These consistently low RMSD values indicated minimal structural deviation from the initial conformations, suggesting that the identified analogs remained stably bound to Mpro without significantly disturbing their overall topology.

H-bond numbers

Hydrogen bond interactions between the identified nirmatrelvir analogs and adjacent amino acid residues of Mpro were assessed over 100 ns MDS to determine their stability and persistence (Fig. 8). Intriguingly, PubChem-162-396-453, PubChem-162-396-449, PubChem-162-396-448, and nirmatrelvir maintained the establishment of approximately four H-bonds with the key residues of the Mpro binding pocket during the simulation. These results provided strong evidence for the stabilization of the identified nirmatrelvir analogs within the Mpro binding pocket throughout 100 ns MDS.

RMSF analysis

To assess the structural flexibility of Mpro, the RMSF of the Cα-backbone atoms was evaluated (Fig. 9a). As indicated in Figure 9a, the RMSF values were found to be 0.19, 0.15, 0.15, 0.17, and 0.14 nm for the apo-Mpro, PubChem-162-396-453-Mpro, PubChem-162-396-449-Mpro, PubChem-162-396-448-Mpro, and nirmatrelvir-Mpro, respectively. Besides, the residue-level fluctuations remained low and consistent across all complexes, implying that the Mpro structure was stable and not significantly perturbed by analogs binding throughout the simulation time.

Rg analysis

Rg analysis provides insight into the degree of folding or unfolding of the protein structure in response to analog binding. In order to evaluate the overall compactness of Mpro in both its apo and soaked forms, Rg was gauged over the 100 ns MDS (Fig. 9b). As shown in Figure 9b, the average Rg values for apo-Mpro, PubChem-162-396-453-Mpro, PubChem-162-396-449-Mpro, PubChem-162-396-448-Mpro, and nirmatrelvir-Mpro were consistently around 2.2 nm. These findings suggested that Mpro retained its structural compactness and did not undergo significant conformational expansion or collapse upon analog binding. Overall, the Rg analysis confirmed that Mpro maintained its structural integrity, and the identified nirmatrelvir analogs contributed to the steadiness of the analog-Mpro complexes over simulation time.

PCA analysis

PCA was employed to examine the structural dynamics of both the apo-Mpro and nirmatrelvir analogs-Mpro systems over 100 ns MDS. Due to the high similarity among the nirmatrelvir analogs, PubChem-162-396-453 was chosen for detailed analysis. To better understand the conformational changes during the MDS, a PCA-based clustering method was used to group conformations according to their structural similarities61. Figure 10 illustrates the distribution of motions along the first two principal components (PC1 and PC2) for both apo-Mpro and PubChem-162-396-453-Mpro systems. The scatterplot shows the projection of simulation frames onto the PC1 and PC2 levels, revealing distinct configurational sampling between the two systems. The apo system shows a broader distribution and lower correlation of movements, reflecting the heightened residue flexibility presented in Figure 9a. These observations imply that binding of the identified nirmatrelvir analogs induce significant changes in Mpro dynamics and stabilises distinct conformational states.

Drug-likeness features

In the initial phases of drug discovery, the concept of drug-likeness provides essential guidelines for evaluating the druggability of candidates based on their physicochemical characteristics62. For transparency, the physicochemical properties of the identified nirmatrelvir analogs were estimated utilizing the Molinspiration platform. PubChem-162-396-453, PubChem-162-396-449, PubChem-162-396-448, and nirmatrelvir exhibited lipophilicity (MlogP) values below 5, indicating a favorable hydrophobic balance for oral bioavailability (Fig. 11).

The TPSA values observed for the identified analogs and nirmatrelvir spanned from 131.40 to 168.69 Ų, indicating their conduciveness to efficient oral absorption and transmembrane permeability63. Furthermore, all identified nirmatrelvir analogs had HBA lower than 10, except for PubChem-162-396-449, which possessed 11 HBA. The number of HBD was less than 5 for all identified analogs and nirmatrelvir, aligning with Ro5. The MW was found to be 511.6, 529.5, 515.5, and 499.5 daltons for PubChem-162-396-453, PubChem-162-396-449, PubChem-162-396-448, and nirmatrelvir, respectively. Although some compounds slightly exceed the conventional MW threshold of 500 g/mol, it has been reported that several drugs authorized by the FDA surpass this limit without compromising physicochemical performance64.

Pharmacokinetic characteristics

ADMET profiles for the identified analogs were predicted using the pkCSM server. To thoroughly assess drug absorption, both skin permeability and Caco-2 cell permeability were considered. The predicted skin permeability (log Kp) values for PubChem-162-396-453, PubChem-162-396-449, PubChem-162-396-448, and nirmatrelvir were −3.1, −2.9, −2.9, and −3.2, respectively, which were within acceptable limits and suggested moderate dermal absorption potential (Table 2). In addition, PubChem-162-396-453, PubChem-162-396-449, PubChem-162-396-448, and nirmatrelvir exhibited favorable Caco-2 permeability, with values of 0.21, 0.44, 0.45, and 0.16 cm/s, respectively, indicating efficient intestinal absorption. Distribution characteristics were evaluated through BBB and CNS permeability predictions. The evaluated log BB values for all analogs were ≤ −0.95, which typically suggested limited BBB penetration. Similarly, the predicted log PS (CNS permeability) values were −3.4, −4.2, −4.1, and −3.2 for PubChem-162-396-453, PubChem-162-396-449, PubChem-162-396-448, and nirmatrelvir, respectively. These values indicated poor CNS permeability, consistent with limited distribution to the central nervous system. In terms of metabolism, all identified analogs and nirmatrelvir were predicted to be CYP3A4 substrates but not inhibitors, suggesting a lower likelihood of causing CYP3A4-mediated drug-drug interactions. For excretion, the predicted total drug clearance values were 0.42, 0.39, 0.42, and 0.26 mL/min/kg for PubChem-162-396-453, PubChem-162-396-449, PubChem-162-396-448, and nirmatrelvir, respectively, indicating a moderate rate of elimination from the body. Regarding toxicity, the identified nirmatrelvir analogs were predicted to be non-toxic and non-skin sensitizing, while nirmatrelvir was predicted to be slightly toxic but non-skin sensitizing (Table 2). These findings demonstrated the favorable pharmacokinetics and safety potentiality of the identified nirmatrelvir analogs as promising anti-COVID-19 drug candidates.

Conclusion

As the COVID-19 pandemic landscape evolves, nirmatrelvir stands as a foundational antiviral agent targeting SARS-CoV-2, yet continued efforts in optimizing and discovering new analogs are necessary to address resistance and improve clinical outcomes. In the ongoing study, in-silico techniques were applied to evaluate forty-five nirmatrelvir analogs as potential inhibitors of Mpro. Covalent docking calculations were initially used to screen the selected nirmatrelvir analogs, identifying the most promising candidates according to their anticipated docking scores with Mpro. The top-scoring nirmatrelvir analogs were subsequently subjected to 100 ns MDS, accompanied by binding affinity estimates utilizing the MM-GBSA approach. Among the investigated analogs, PubChem-162-396-453, PubChem-162-396-449, and PubChem-162-396-448 exhibited stronger binding affinities with ΔGbinding values of −49.7, −46.3, and −44.9 kcal/mol, respectively, in comparison with nirmatrelvir (calc. −40.7 kcal/mol). Following MDS, the structural integrity of the identified nirmatrelvir analogs bound to Mpro was displayed through post-MD analyses. Furthermore, physicochemical and ADMET profiling suggested that the identified analogs possess favorable drug-like properties and oral bioavailability. Overall, the in-silico findings highlighted PubChem-162-396-453, PubChem-162-396-449, and PubChem-162-396-448 as promising covalent inhibitors of Mpro, warranting further validation through in-vitro/in-vivo studies as potential COVID-19 therapeutics.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Wang, L., Wang, Y., Ye, D. & Liu, Q. Review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) based on current evidence. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 55, 105948. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105948 (2020).

Cucinotta, D., Vanelli, M. W. H. O. & Declares COVID-19 a pandemic. Acta Biomed. 91, 157–160. https://doi.org/10.23750/abm.v91i1.9397 (2020).

Ciotti, M. et al. The COVID-19 pandemic. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 57, 365–388. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408363.2020.1783198 (2020).

World Health Organization. (2020).

Krishnamoorthy, S., Swain, B., Verma, R. S., Gunthe, S. S. & SARS-CoV, M. E. R. S. C. V. and 2019-nCoV viruses: an overview of origin, evolution, and genetic variations. VirusDisease 31, 411–423, (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13337-020-00632-9

Tu, B., Gao, Y., An, X., Wang, H. & Huang, Y. Localized delivery of nanomedicine and antibodies for combating COVID-19. Acta Pharm. Sin B. 13, 1828–1846. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2022.09.011 (2023).

Anand, K. et al. Structure of coronavirus main proteinase reveals combination of a chymotrypsin fold with an extra alpha-helical domain. EMBO J. 21, 3213–3224. https://doi.org/10.1093/emboj/cdf327 (2002).

Yang, H. et al. The crystal structures of severe acute respiratory syndrome virus main protease and its complex with an inhibitor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 13190–13195, (2003). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1835675100

Ibrahim, M. A. A., Abdelrahman, A. H. M. & Hegazy, M. F. In-silico drug repurposing and molecular dynamics puzzled out potential SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitors. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 39, 5756–5767. https://doi.org/10.1080/07391102.2020.1791958 (2021).

Ibrahim, M. A. A. et al. In silico evaluation of prospective anti-COVID-19 drug candidates as potential SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitors. Protein J. 40, 296–309, (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10930-020-09945-6

Chakraborty, A. et al. Repurposing of antimycobacterium drugs for COVID-19 treatment by targeting SARS CoV-2 main protease: an in-silico perspective. Gene 922, 148553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gene.2024.148553 (2024).

Piplani, S., Singh, P., Petrovsky, N. & Winkler, D. A. Computational repurposing of drugs and natural products against SARS-CoV-2 main protease (M(pro)) as potential COVID-19 therapies. Front. Mol. Biosci. 9, 781039. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmolb.2022.781039 (2022).

Sharma, G. et al. Identification of promising SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitor through molecular docking, dynamics simulation, and ADMET analysis. Sci. Rep. 15, 2830. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86016-9 (2025).

Prada Gori, D. N. et al. Drug repurposing screening validated by experimental assays identifies two clinical drugs targeting SARS-CoV-2 main protease. Front. Drug Discov. 2, 1. https://doi.org/10.3389/fddsv.2022.1082065 (2023).

Pawar, A. Y. Combating devastating COVID-19 by drug repurposing. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 56, 105984. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105984 (2020).

Drozdzal, S. et al. FDA approved drugs with pharmacotherapeutic potential for SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) therapy. Drug Resist. Updat. 53, 100719. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drup.2020.100719 (2020).

Yang, J. et al. Progress in research and development of Temozolomide brain-targeted preparations: a review. J. Drug Target. 31, 119–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/1061186X.2022.2119243 (2023).

Heskin, J. et al. Caution required with use of ritonavir-boosted PF-07321332 in COVID-19 management. Lancet 399, 21–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02657-X (2022).

Administration, U. F. D. Fact sheet for healthcare providers: emergency use authorization for Paxlovid. 5 (2022).

Dawood, A. A. The efficacy of paxlovid against COVID-19 is the result of the tight molecular Docking between M(pro) and antiviral drugs (nirmatrelvir and ritonavir). Adv. Med. Sci. 68, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advms.2022.10.001 (2023).

Halford, B. Pfizer unveils its oral SARS-CoV-2 inhibitor. Chem. Eng. News. 99, 7–7 (2021).

Owen, D. R. et al. An oral SARS-CoV-2 M(pro) inhibitor clinical candidate for the treatment of COVID-19. Science 374, 1586–1593. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abl4784 (2021).

Dos Santos, A. M. et al. Experimental study and computational modelling of Cruzain cysteine protease Inhibition by dipeptidyl nitriles. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 20, 24317–24328. https://doi.org/10.1039/c8cp03320j (2018).

Ramos-Guzman, C. A., Ruiz-Pernia, J. J. & Tunon, I. Computational simulations on the binding and reactivity of a nitrile inhibitor of the SARS-CoV-2 main protease. ChemComm 57, 9096–9099. https://doi.org/10.1039/d1cc03953a (2021).

Joyce, R. P., Hu, V. W. & Wang, J. The history, mechanism, and perspectives of nirmatrelvir (PF-07321332): an orally bioavailable main protease inhibitor used in combination with Ritonavir to reduce COVID-19-related hospitalizations. Med. Chem. Res. 31, 1637–1646. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00044-022-02951-6 (2022).

Li, J. et al. Structural basis of the main proteases of coronavirus bound to drug candidate PF-07321332. J. Virol. 96, e0201321. https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.02013-21 (2022).

Gordon, J. C. et al. H++: a server for estimating pKas and adding missing hydrogens to macromolecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, W368–W371. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gki464 (2005).

OMEGA 4.1.1.0. OpenEye Scientific Software, Santa Fe, NM, USA, (2021).

Hawkins, P. C., Skillman, A. G., Warren, G. L., Ellingson, B. A. & Stahl, M. T. Conformer generation with OMEGA: algorithm and validation using high quality structures from the protein databank and Cambridge structural database. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 50, 572–584. https://doi.org/10.1021/ci100031x (2010).

SZYBKI 2.4.0.0. OpenEye Scientific Software, Santa Fe, NM, USA, (2021).

Gasteiger, J. & Marsili, M. Iterative partial equalization of orbital electronegativity - a rapid access to atomic charges. Tetrahedron 36, 3219–3228. https://doi.org/10.1016/0040-4020(80)80168-2 (1980).

London, N. et al. Covalent Docking of large libraries for the discovery of chemical probes. Nat. Chem. Biol. 10, 1066–1072. https://doi.org/10.1038/nchembio.1666 (2014).

Morris, G. M. et al. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: automated Docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 30, 2785–2791. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.21256 (2009).

Forli, S. et al. Computational protein-ligand Docking and virtual drug screening with the AutoDock suite. Nat. Protoc. 11, 905–919. https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2016.051 (2016).

AMBER. (University of California, San Francisco, 2020). (2020).

Ibrahim, M. A. A. et al. Exploring marine natural products for identifying putative candidates as EBNA1 inhibitors: an insight from molecular docking, molecular dynamics, and DFT computations. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 735, 150856. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2024.150856 (2024).

Ibrahim, M. A. A. et al. Benzothiazinone analogs as Anti-Mycobacterium tuberculosis DprE1 irreversible inhibitors: covalent docking, validation, and molecular dynamics simulations. PLoS One. 19, e0314422. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0314422 (2024).

Abdeljawaad, K. A. A. et al. Potential P-glycoprotein (P-gp) inhibitors from SuperDRUG2 database toward reversing multidrug resistance in cancer treatment: database mining, molecular dynamics, and binding energy estimations. J. Mol. Graph Model. 137, 108997. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmgm.2025.108997 (2025).

Mahmoud, D. G. M., Mekhemer, G. A. H., Hegazy, M. E. F., Al-Fahemi, J. H. & Ibrahim, M. A. A. In-Silico exploration of the streptomedb database for potential irreversible DprE1 inhibitors toward antitubercular treatment. Chemistryopen n/a. 2500237 https://doi.org/10.1002/open.202500237 (2025).

Wang, J., Wolf, R. M., Caldwell, J. W., Kollman, P. A. & Case, D. A. Development and testing of a general amber force field. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1157–1174. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.20035 (2004).

Maier, J. A. et al. ff14SB: improving the accuracy of protein side chain and backbone parameters from ff99SB. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 11, 3696–3713. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00255 (2015).

Cornell, W. D., Cieplak, P., Bayly, C. I. & Kollman, P. A. Application of RESP charges to calculate conformational energies, hydrogen bond energies, and free energies of solvation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 115, 9620–9631. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja00074a030 (2002).

Darden, T., York, D. & Pedersen, L. Particle mesh ewald: AnN⋅log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J. Chem. Phys. 98, 10089–10092. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.464397 (1993).

Berendsen, H. J. C., Postma, J. P. M., van Gunsteren, W. F., DiNola, A. & Haak, J. R. Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath. J. Chem. Phys. 81, 3684–3690. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.448118 (1984).

Miyamoto, S. & Kollman, P. A. Settle - an analytical version of the shake and rattle algorithm for rigid water models. J. Comput. Chem. 13, 952–962. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.540130805 (1992).

Politzer, P. & Murray, J. S. Halogen bonding: an interim discussion. ChemPhysChem 14, 278–294. https://doi.org/10.1002/cphc.201200799 (2013).

Massova, I. & Kollman, P. A. Combined molecular mechanical and continuum solvent approach (MM-PBSA/GBSA) to predict ligand binding. Perspect. Drug Discov. 18, 113–135. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008763014207 (2000).

Onufriev, A., Bashford, D. & Case, D. A. Exploring protein native States and large-scale conformational changes with a modified generalized born model. Proteins 55, 383–394. https://doi.org/10.1002/prot.20033 (2004).

Hou, T., Wang, J., Li, Y. & Wang, W. Assessing the performance of the molecular mechanics/Poisson Boltzmann surface area and molecular mechanics/generalized born surface area methods. II. The accuracy of ranking poses generated from Docking. J. Comput. Chem. 32, 866–877. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.21666 (2011).

Wang, E. et al. End-point binding free energy calculation with MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA: strategies and applications in drug design. Chem. Rev. 119, 9478–9508. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00055 (2019).

Sun, H. et al. Assessing the performance of MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods. 7. Entropy effects on the performance of end-point binding free energy calculation approaches. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 20, 14450–14460. https://doi.org/10.1039/c7cp07623a (2018).

Martìnez, A. M. & Kak, A. C. PCA versus LDA. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 23, 228–233. https://doi.org/10.1109/34.908974 (2001).

Brustle, M. et al. Descriptors, physical properties, and drug-likeness. J. Med. Chem. 45, 3345–3355. https://doi.org/10.1021/jm011027b (2002).

Clark, D. E. & Pickett, S. D. Computational methods for the prediction of ‘drug-likeness’. Drug Discov Today. 5, 49–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1359-6446(99)01451-8 (2000).

Pires, D. E., Blundell, T. L. & Ascher, D. B. PkCSM: predicting Small-Molecule Pharmacokinetic and toxicity properties using Graph-Based signatures. J. Med. Chem. 58, 4066–4072. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00104 (2015).

da Silva Costa, J. et al. Virtual screening and statistical analysis in the design of new caffeine analogues molecules with potential epithelial anticancer activity. Curr. Pharm. Des. 24, 576–594. https://doi.org/10.2174/1381612823666170711112510 (2018).

Hevener, K. E. et al. Validation of molecular Docking programs for virtual screening against dihydropteroate synthase. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 49, 444–460. https://doi.org/10.1021/ci800293n (2009).

McInnes, C. Virtual screening strategies in drug discovery. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 11, 494–502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.08.033 (2007).

Bajorath, F. Integration of virtual and high-throughput screening. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 1, 882–894. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd941 (2002).

Chen, W. et al. Advances and challenges in using nirmatrelvir and its derivatives against SARS-CoV-2 infection. J. Pharm. Anal. 13, 255–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpha.2022.10.005 (2023).

Wolf, A. & Kirschner, K. N. Principal component and clustering analysis on molecular dynamics data of the ribosomal L11.23S subdomain. J. Mol. Model. 19, 539–549. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00894-012-1563-4 (2013).

Bickerton, G. R., Paolini, G. V., Besnard, J., Muresan, S. & Hopkins, A. L. Quantifying the chemical beauty of drugs. Nat. Chem. 4, 90–98. https://doi.org/10.1038/nchem.1243 (2012).

Bakht, M. A., Yar, M. S., Abdel-Hamid, S. G., Qasoumi, A., Samad, A. & S. I. & Molecular properties prediction, synthesis and antimicrobial activity of some newer oxadiazole derivatives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 45, 5862–5869. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmech.2010.07.069 (2010).

Mullard, A. Re-assessing the rule of 5, two decades on. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 17, 777–777. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd.2018.197 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to the Ongoing Research Funding Program, (ORF-2025-691), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The computational work was completed with resources provided by the CompChem Lab (Minia University, Egypt, hpc.compchem.net), Center for High-Performance Computing (Cape Town, South Africa, http://www.chpc.ac.za), and Bibliotheca Alexandrina (http://hpc.bibalex.org).

Funding

N/A.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Mahmoud Ibrahim and Tamer Shoeib; Data curation, Doaa Khaled and Doaa Mahmoud; Formal analysis, Doaa Khaled and Peter Sidhom; Investigation, Doaa Khaled, Doaa Mahmoud and Alaa Abdelrahman; Methodology, Mahmoud Ibrahim and Alaa Abdelrahman; Project administration, Mahmoud Ibrahim, Alaa Abdelrahman, Yanshuo Han, Tamer Shoeib and Ahmad Rady; Resources, Mahmoud Ibrahim, Tamer Shoeib, Badr Aldahmash and Ahmad Rady; Software, Mahmoud Ibrahim; Supervision, Mahmoud Ibrahim and Tamer Shoeib; Visualization, Doaa Khaled, Doaa Mahmoud and Peter Sidhom; Writing – original draft, Doaa Khaled and Doaa Mahmoud; Writing – review & editing, Mahmoud Ibrahim, Alaa Abdelrahman, Peter Sidhom, Yanshuo Han, Tamer Shoeib, Badr Aldahmash and Ahmad Rady. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

N/A.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ibrahim, M.A.A., Khaled, D.M.A., Mahmoud, D.G.M. et al. Insights from integrated covalent docking and molecular dynamics simulations of nirmatrelvir analogs as potential SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors. Sci Rep 15, 39099 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24162-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24162-w