Abstract

The long-term mining of lead-zinc ore bodies in Suichang Gold Mine has formed a high-stage, long-span columnar goaf group above 500 m elevation, posing significant risks of roof collapse, slope fragmentation, and ground pressure disasters. These hazards threaten the safety of deep mining operations and surface stability. To address these challenges, this study integrates field investigations, laboratory rock mechanics experiments, and FLAC3D numerical simulations to analyze the stability evolution of goafs before and after filling. Key innovations include the application of disaster chain theory to interpret goaf failure mechanisms and the optimization of cement-sand ratios for targeted filling (1:20 for 260–610 m levels and 1:8 for 528–540 m levels). Results demonstrate that cemented filling reduces vertical displacement by 2–4 cm, alleviates stress concentration (maximum compressive stress decreased by 0.5–1.0 MPa), and minimizes plastic zone expansion. Furthermore, the proposed interval mining sequence (first mining 300–390 m, followed by 260–290 m and 420–500 m levels) ensures both production efficiency and operational safety. This research provides a systematic framework for goaf management in complex mining environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the long-term development and utilization of mineral resources in China, the number and area of goaf in underground metal mines continue to rise. A large number of residual goaf areas that have not been dealt with in a timely manner can easily lead to large-scale ground pressure disasters, causing surface subsidence and posing serious safety hazards to deep mining. Therefore, how to effectively manage goaf and avoid disasters caused by goaf instability has become an urgent technical challenge in mine safety production. Researchers at home and abroad have conducted a large number of theoretical analyses, similar simulation experiments, and numerical simulations on the stability analysis of goaf, and have achieved certain results in the deformation process of surrounding rock, the instability mechanism of goaf, and the development of unstable disasters in goaf. For example, the theory is commonly used in the analysis of goaf stability theory1. Kuznetsov of the former Soviet Union proposed a similarity model experiment based on the principle of similarity and similarity criteria to explore the laws of objects or verify computational results2. However, there are still many shortcomings in existing research.

In terms of theoretical analysis of goaf stability, the Terzaghi theory has limitations. When the span of a single goaf is fixed, this theory suggests that the overlying strata within the influence range of the goaf will slowly sink under their own weight3,4. The frictional resistance provided by the rock masses on both sides of the goaf can suppress sinking, and when the thickness of the overlying strata reaches a certain level5, the goaf can maintain a stable equilibrium state. However, in the face of nonlinear failure processes in complex goaf areas, the Terzaghi theory is difficult to conduct accurate analysis6. In addition, similarity model experiments based on similarity principles and criteria can simulate the working principles and effects of target objects by creating scaled down physical models, similar to proposing7, verifying, and analyzing hypotheses through model simulation experiments8,9,10. However, it is also difficult to accurately analyze the nonlinear failure process of complex goaf areas.

Current research in the field of numerical simulation mostly focuses on a single factor, lacking analysis of multi field coupling and disaster chain evolution11,12,13,14. For the stability assessment of high-level and large-span goaf, there is a lack of dynamic disaster chain perspective. At the same time, there is a significant lack of collaborative optimization research on the ratio of filling materials and mining sequence.

To gain a deeper understanding of the potential instability and failure mechanisms in goaf areas, this study introduces the disaster chain theory. Based on numerical simulation results, the possible chain reaction of disasters triggered after the formation of goaf was analyzed: initial local roof collapse or caving → causing stress redistribution and new stress concentration in adjacent areas → inducing a larger range of plastic deformation or failure of surrounding rock → ultimately leading to chain collapse or surface subsidence of goaf. This theoretical framework clearly reveals the dynamic evolution process of goaf instability from local damage to overall disaster. Through rigorous FLAC3D simulation analysis and the explanation of the damage mechanism based on the disaster chain theory, this study theoretically demonstrates the technical feasibility and safety of using tailings to prepare cemented backfill for backfill mining in the mine. The optimized cement sand ratio scheme (1:20 and 1:8) meets the stability and economic requirements of different levels of differentiation. The proposed interval mining sequence (300–390 m priority, followed by 260–290 m and 420–500 m) scientifically coordinates production rhythm and safety risk control.

The research results not only provide direct theoretical basis and operational guidance for the safe and efficient application of tailings filling technology in the mine, but also provide a systematic framework for the systematic management, disaster prevention and control, and green mining practice of mining goaf under similar complex geological and engineering conditions, including modeling simulation mechanism analysis parameter optimization time series design, which can be referenced.

Mine overview and experimental testing

Background and ore body characteristics

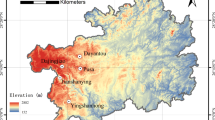

Zhejiang Suichang Gold Mine Co., Ltd. is located in Huayuanling, Suichang County, Lishui City, Zhejiang Province, with a area of 765300 km² and an annual production scale of 183600 tons15. The mine has developed the Huayuanling West Gold Mine, Huayuanling Lead-Zinc Mine, and Yejiatian Fluorite Mine(See Fig. 1). The lead-zinc ore body, with a vertical depth exceeding 540 m and an average horizontal thickness of 46 m, is characterized as a steeply inclined thick ore body with a short strike length (67 m on average) and large burial depth16,17. It is mined primarily using the sublevel open-stope method for main ore sections and the shallow-hole shrinkage method for irregular small-angle ore bodies. The ore and surrounding rock exhibit high mechanical stability, requiring minimal support during mining.

Current situation of mining production and Current situation of goaf: (a) the adit entrance of the 500 m level; (b) layout of surface filling pipeline at 580 m adit entrance; (c) highway construction in mines; (d) filling station configuration (e) bottom structure of 528 m level; (f) the chute of 540 m level; (g) the condition of the baseplate after filling the goaf.

Mining status and goaf distribution

Mining elevations range from + 220 m to + 760 m (see Fig. 2). The mine has completed mining for some upper ore sections (710–740 m and 670–710 m levels)18, which are now closed with limited access for goaf assessment (See Fig. 2). The current focus is on the 528–650 m level, where three main goaf areas exist:

\

-

1.

710–740 m and 670–710 m goafs: Small-scale with blocked access, precluding filling.

-

2.

528–650 m goaf (See Fig. 1): Large volume and exposed area, showing evident roof collapse and sidewall fragmentation. The 528–540 m level requires cemented filling due to high stability demands, while the 540–610 m level uses low-cost non-cemented filling19. The 610–650 m level is temporarily unfilled due to pumping equipment limitations.

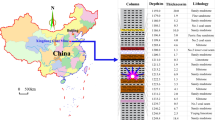

Physical-mechanical properties of rock and fill materials

Samples collected from 260 to 650 m levels were tested to determine rock properties (Table 1). Ore and rock densities range from 2.47 to 3.1 g/cm3 with a water content of 0.14–1.4%. Saturated uniaxial compressive strength is 70–170 MPa, and average uniaxial tensile strength is 7–14 MPa, indicating dense and intact rock masses with high mechanical strength.

For filling materials (Table 2), a cement-sand ratio of 1:8 (70% mass concentration) is used for cemented filling, achieving 0.51 MPa at 3 days and 1.41 MPa at 7 days. Low-strength non-cemented filling with a 1:20 ratio (70% concentration) yields 0.11 MPa at 3 days and 0.25 MPa at 7 days, balancing cost and stability requirements20.

Filling systeam

The filling station of Suichang Gold Mine adopts the design scheme of hydraulic pump pipeline pumping and filling after the concentrated and cemented slurry preparation of the whole tailings discharged from the beneficiation plant. The tailings conveying pump station is located next to the beneficiation plant. The whole tailings mortar with a concentration of about 20% discharged from the beneficiation plant is transported to the filling station through a first stage conveying method by the pump station. The filling station is arranged in the + 540 m adit industrial site. In the filling station, it is concentrated and mixed with an appropriate amount of cementitious material (such as cement) to prepare a filling slurry that meets the design strength and quantity requirements. Then, it is pressed into the goaf through hydraulic pump pipelines and various underground pipelines for filling.

FLAC3D modeling and disaster chain theory

This study used FLAC3D software for simulation and numerical analysis. FLAC3D (3D Fast Lagrangian Analysis Code) is a simulation calculation software developed by ITASA in the United States21,22. It is a three-dimensional high-end numerical analysis program developed based on continuous medium theory and explicit finite difference method23,24,25, widely used in geotechnical and mining engineering analysis and design. It is particularly suitable for dealing with complex geotechnical problems that are difficult to solve by finite element methods.

Geometric modelling

In view of the complexity and variability of the actual mining technical conditions of the goaf, in order to facilitate modeling, analysis, and calculation. The following simplifications are made:

-

1.

The ore body is assumed to be an ideal elastic-plastic body, and the strength and volume of the material flow with plasticity after the yield point change;

-

2.

The ore body and surrounding rock are locally homogeneous and isotropic materials, and plastic flow does not change the material’s isotropy;

-

3.

Considering the brittleness of rock, all physical quantities involved in the analysis are independent of time;

-

4.

Strain hardening (or softening) is not considered;

-

5.

There are no obvious faults in the study area, and the influence of variable loads has not been considered yet;

-

6.

The bottom and side of the model are fixed by the FIX command to limit its vertical and horizontal displacement;

-

7.

Considering the limitations of the finite element program, it is assumed that there is no influence of tectonic activities in the site, the stress is of the geostatic field type, and the strata are in integrated contact. The interior of the strata is a continuous medium. In the model, the influence of groundwater activities, structural planes, fractures, and weak layers in rock and ore bodies are not considered existence and influence;

-

8.

Regarding model unit division, finer division generally leads to more accurate results. However, overly fine division consumes significant machine time, and stress changes minimally in areas far from the study zone. Thus, the grid size should be determined based on the actual goaf situation, balancing calculation accuracy and efficiency.

Based on the mine’s level plans, goaf distribution map, and ore - body geological plan, the model size is set at 300 m × 300 m × 580 m. To clearly present simulation results, the model elevation is set at 800 m, but calculations are based on 880 m elevation data. An evenly distributed load on the model’s upper surface simulates the overlying 80 m. An ore - body model from 220 m to 740 m elevation is constructed (Fig. 3a), then embedded into the surrounding rock model (Fig. 3b). Given the lack of weak interlayers in the engineering geology, a simplified model is used, with working layers at different levels in direct contact.

Rationality and limitations of model assumptions

Based on the actual geological and mining conditions of Suichang gold mine (see Sect. 2), the FLAC3D model is simplified as necessary to improve computational feasibility. The following is a demonstration and limitation explanation for the key hypothesis: the uniaxial compressive strength of the ore rock (70–170 MPa) is much higher than the stress level in the goaf, and no significant creep phenomenon was found in the field investigation. The use of an ideal elastoplastic model can effectively characterize the post peak behavior of brittle rock masses. However, neglecting strain softening may underestimate the extent of local failure zone expansion. Subsequent research will introduce softening parameters.

When conducting on-site surveys and FLAC3D initial simulations of large-span columnar goaf groups at elevations above 500 m in Suichang Gold Mine, the “trigger evolution” core framework of the goaf disaster chain theory can be used to preliminarily identify the germination and transmission characteristics of the disaster chain in the case.

Laboratory tests have shown low variability in ore rock, and underground exploration has confirmed that there are no dominant joint sets that meet the isotropic simplification conditions. Neglecting micro cracks may lead to lower predicted values of roof settlement. The seismic activity in the mining area is low, and the hydrological report shows that the water level in the goaf is below 528 m, and the permeability of the surrounding rock is less than 10−7 m/s. The impact of seepage can be ignored. Deep mining (< 220 m) may activate tectonic stress.

Upper goaf

Simulation scheme

Scheme (1) The mined goaf includes three goaf areas: 710–740 m, 670–710 m, and 528–650 m. The first two goaf areas are relatively small, while the last one is relatively large. The level of area is characterized by a small upper part and a large lower part. Among them, the 610 level is only 702m2, and it increases to 1887m2 in the 540 m level, under the existing conditions, calculate the stress, strain, displacement, and plastic zone of the roof, floor, and two sides of the 528–650 m goaf, and analyze the failure mode of the goaf;

Scheme (2) After the cemented filling of the 528–540 m goaf, the stress, strain, displacement, and plastic zone of the roof, floor, and two sides of the 540–650 m goaf are calculated, and the failure mode of the goaf is analyzed;

Scheme (3) After cemented filling of 528–540 m goaf and non-cemented filling of 540–610 m goaf, the stress, strain, displacement, and plastic zone of 610–650 m goaf roof, floor, and two sides are calculated, and the failure mode of goaf instability is analyzed.

Conduct a comprehensive comparative analysis of the results of the above numerical simulation schemes to determine the subsequent status of the goaf in each scheme.

Stability of goaf and filling treatment results

-

1.

Simulation of goaf status. The simulation results of the plastic zone in scheme 1 (see Fig. 4), in which Fig. 4a mainly shows the plastic zone state of the remaining ore body after mining; Fig. 4b displays the plastic zone state of the wall rock mass in the goaf. Among them, in Fig. 4a, some rocks in the ore body are prone to shear failure, and some plastic zones have been connected at the level of 710–740 m, with a small amount of tensile failure; in Fig. 4b, there are also some shear failure and tensile failure units on the side wall of the goaf.

Simulation cloud map in scheme 1 (see Fig. 5). Figure 5a shows the displacement in Z direction. It can be seen from the nephogram that the maximum displacement occurs at the level of 710–740 m at the top of the rock mass, with a sinking of 8.5 cm, a sinking of 7 cm at the level of 650–670 m, and a sinking of 6–7 cm in the level of 528–650 m. Figure 5b shows the maximum principal stress results. In FLAC3D, the result is positive for tension and negative for pressure. It can be found that the goaf has partial stress concentration. The maximum tensile stress on the level of 710–740 m is 4.49 × 105Pa, and the maximum compressive stress on the edge of the goaf in the level of 528–650 m is 1.5 × 106Pa. Figure 5c shows the results of the minimum principal stress, and it can be found that the minimum compressive stress on the edge of the goaf at the level of 528–650 m is about 1.8 × 107Pa, and there is a partial tensile stress in the lower right corner of the 528–540 m level, with a magnitude of 4.49 × 105Pa. In general, the long-term exposure of the goaf will lead to the local stress concentration of the wall of the goaf, and also accumulate some damaged units. The stability of the goaf is poor.

-

2.

Simulation results of scheme 2 (see Fig. 6). Figure 6a shows the simulation results of the plastic zone after 528–540 m cemented filling. It can be seen that the scope of the damaged unit is smaller than that of the goaf without filling. The Z-direction displacement nephogram is shown in Fig. 6b. The settlement of the level of 528–540 m is 4 cm, which is significantly lower than that of 6 cm without filling. The displacement of the side wall in the level of 540–650 m is 6 cm, which is less than that before filling. Figure 6c shows the maximum principal stress nephogram of the goaf, and the maximum compressive stress of the 528–540 m filling area is 0.5–1 × 106 Pa, and there is no part with obvious tensile stress when unfilled. Figure 6d is the minimum principal stress nephogram of the goaf, in which the minimum compressive stress of the 528–540 m filling area is 6 × 106 Pa, less than the minimum compressive stress when not filled. In general, after 528–540 m cemented filling, the stability of the remaining goaf is slightly better than that of completely unfilled, and the stress concentration phenomenon is relieved to some extent.

-

3.

Simulation results of the plastic zone and displacement nephogram in scheme 3 (see Fig. 7), simulation results of nephogram of principal stress in scheme 3 (see Fig. 8). As shown in Fig. 7a, the plastic zone in the level of 528–650 m has been significantly improved. In Fig. 8b, only the plastic zone in the lower right corner of the filling body is damaged by shear, while the plastic zone in other areas is damaged by shear and tension. Compared with unfilled goaf, the side wall of 610–650 m goaf has less plastic zone. Figure 7b shows the displacement nephogram in the Z direction. It can be seen from the figure that the filling body sinks 6–8 cm and the side wall of the goaf sinks 4–6 cm, which has little change from the previous one. Figure 8a,b are the simulation nephogram of the maximum principal stress in the goaf, and the maximum compressive stress of the filling body is 1.2 × 106 Pa. Figure 8c is the simulated nephogram of the minimum principal stress in the goaf, and the minimum compressive stress in the goaf after filling is 6 × 106 Pa. Compared with the previous two simulation results, the number of failure units of the whole model is significantly reduced, and the stress concentration phenomenon is significantly relieved, which indicates that the goaf is more stable after filling treatment.

-

4.

Numerical simulation conclusion. The analysis of the above simulation results (see Table 3) shows that compared to the unfilled state, the plastic area of the goaf decreases significantly after filling and the vertical displacement and stress values also decrease, indicating that the goaf gradually tends to stabilize after filling. As we can see, there are a large number of plastic zones in the middle of 528–650 m, which have undergone shear and tensile failure. After filling, the plastic zone in the middle of 528–610 m has significantly improved, while only a small amount of damage has occurred in the middle of 610–650 m. Therefore, it is necessary to use cementitious filling of 528–540 m and non-cementitious filling of 540–610 m to help stabilize the goaf.

Deep untouched ore body

Mining plan

From the depth of 528 m to the lowest control elevation of 220 m of the ore body, it belongs to the immovable ore body. According to the overall mining plan of the preliminary design, the deep immovable ore body will be mined in three levels, which are:

Mining of 420–500 m undisturbed ore body. The mining of the deep 420–500 m untouched ore body shall be carried out, and the top pillar shall be reserved within the upper part of 500–528 m, and the 390–420 m shall be reserved as the bottom pillar.

Mining of 300–390 m untouched ore body. Carry out the mining of the deep 300–390 m untouched ore body, and set the top pillar within the upper 390–420 m range, and set the 290–300 m as the bottom pillar.

Mining of 260–290 m undisturbed ore body. The mining of the deep 260–290 m untouched ore body shall be carried out, and the top pillar shall be reserved in the upper 290–300 m range, and the lower scale and lower grade 220–260 m ore body shall be reserved as the bottom pillar.

Simulation scheme

Based on the occurrence condition of the goaf above the level of 528 m and the goaf treatment plan, combined with the overall mining plan of the deep untouched ore body, the numerical simulation plan for the stability analysis of the deep untouched ore body is set as follows:

-

1.

The most dangerous situation. Under the conditions of 260–290 m goaf, 300–390 m goaf, and 420–500 m goaf without filling, the upper and deep goaf are the largest and the estimated safety conditions are the worst. Calculate the stress, strain, displacement, and plastic zone of the roof, floor, and sides of the goaf, and analyze the failure mode of the goaf.

-

2.

Secondary hazardous situation. Under the conditions of 260–290 m goaf and 420–500 m goaf without filling, the 300–390 m goaf will be mined and non-cemented filling will be carried out, which is the estimated secondary dangerous situation. Calculate the stress, strain, displacement, and plastic zone of the roof, floor, and sides of the goaf, and analyze the failure mode of the goaf.

-

3.

Safer situation. In the case of 300–390 m goaf, the 260–290 m and 420–500 m goaf shall be filled without cementation. It is estimated that the goaf is relatively safe at this time. Calculate the stress, strain, displacement, and plastic zone of the roof, floor, and sides of the goaf, and analyze the failure mode of the goaf.

-

4.

The safest situation. In the case of 260–290 m goaf, 300–390 m goaf, 420–500 m goaf, and all non-cemented filling, the hidden safety hazard in the goaf can be eliminated and the mining safety is good. Calculate the stress, strain, displacement, and plastic zone of the roof, floor, and sides of the goaf, and analyze the failure mode of the goaf.

Mining stability and non-cemented filling results

-

1.

Simulation results of the plastic zone and displacement nephogram in the most dangerous situation (see Fig. 9), simulation nephogram results of the main stress in the most dangerous situation (see Fig. 10). It can be seen from Fig. 9a that the plastic zone of the side wall of the goaf in the level of 220–500 m is mainly damaged by shear; Fig. 9b shows that the plastic zone of the ore body is mainly damaged by shear and tension; Fig. 9c shows that the plastic zone at the top of the goaf in the level of 500 m has been penetrated, indicating that the roof of the goaf may fall, and relevant measures need to be taken to reduce the possibility of risk. The Z-direction displacement nephogram is shown in Fig. 9d. It can be found that the displacement around the level of 260–290 m of the goaf is 2 cm, the displacement of 300–390 m of the goaf is 4 cm, and the displacement of 420–500 m of the goaf is 6 cm. See Fig. 10a,b for the maximum principal stress nephogram of the goaf. It can be seen from the figure that the maximum compressive stress of the side wall of each goaf is 3 × 106 Pa, the maximum principal stress at the center of the ore body rock is tensile stress, which is 1.5 × 106 Pa, pressure stress is mainly distributed around the rock, the maximum is 2.5 × 106 Pa. Figure 10c,d are the minimum principal stress nephogram, and the minimum compressive stress on the side of each goaf in the figure is 7.5 × 106 Pa, the minimum compressive stress of the ore body in the level of 220–260 m is 1.75 × 107 Pa, the minimum principal stress of other ore bodies is also tensile stress in the center, compressive stress around, and the minimum principal stress is 2.5 × 106 Pa and 1 × 107 Pa. There are many plastic zones in the whole model of this scheme, even some parts have been connected, and the empty zone is in an unstable state.

Simulation results of the plastic zone and displacement nephogram in the most dangerous situation: (a) overall plastic zone state; (b) plastic zone state of the remaining ore body; (c) the plastic zone state of the roof of the goaf in the level of 420–500 m; (d) displacement nephogram in the Z direction.

-

2.

Simulation results of secondary hazardous situation (see Fig. 11). The simulation results of the plastic zone after 300–390 m non-cemented filling are shown in Fig. 11a, and the number of damaged units is slightly lower than the most dangerous situation. Figure 11b shows the displacement nephogram in the Z direction. The subsidence displacement of the goaf in the levels of 260–290 m and 420–500 m is 2.5 cm. Figure 11c shows the maximum principal stress nephogram of the goaf, and the maximum compressive stress of the goaf at the level of 260–290 m is 2 × 106 Pa. Figure 11d shows the minimum principal stress nephogram of the goaf, and the minimum compressive stress of the goaf at the level of 260–290 m is 2 × 106 Pa. The stability of the unfilled empty area of the overall model is slightly better than the most dangerous situation, but it is still in an unstable state.

Simulation nephogram of the main stress in the most dangerous situation: (a) simulation nephogram of overall maximum principal stress; (b) simulation nephogram of the maximum principal stress of the remaining ore body in the goaf; (c) overall minimum principal stress simulation nephogram; (d) simulation nephogram of minimum principal stress of the remaining ore body in the goaf.

-

3.

Simulation results of safer situations (see Fig. 12). The simulation results of the plastic zone are shown in Fig. 12a. It can be seen from the figure that there are few damage units in the area of the filled void, and there are many damage units in the wall of the unfilled void. Figure 12b shows the displacement nephogram in the Z direction, and the maximum displacement of the side subsidence of the goaf at the level of 300–390 m is 2.5 cm. Figure 12c shows the maximum principal stress nephogram of the goaf, and the maximum compressive stress of the side wall of the goaf at the level of 300–390 m is 2 × 106 Pa. Figure 12d shows the minimum principal stress nephogram of the goaf, and the minimum compressive stress of the side of the goaf at the level of 300–390 m is 2.5 × 107 Pa. The goaf filling in this scheme plays a good supporting role for the surrounding goaf, but the stability of the unfilled goaf is still poor.

-

4.

Simulation results of the safest situation (see Fig. 13). Figure 13a shows the simulation of the plastic zone with all non-cemented filling. It can be found that no damaged unit is found below 528 m, which indicates that the hidden danger of instability is eliminated after filling in the goaf, and the goaf is in a safe and stable state. Figure 13b shows the displacement nephogram in the Z direction, and the subsidence displacement of the level of 260–290 m is 2 cm. Figure 13c is the simulated nephogram of the maximum principal stress in the goaf. The maximum compressive stress of the filling body occurs at the level of 260–290 m, which is 4 × 106 Pa. Figure 13d shows the minimum principal stress nephogram of the goaf. The minimum compressive stress of the filling body occurs at the level of 260–290 m, which is about 1.5 × 107 Pa.

-

5.

Numerical simulation conclusion. Through the analysis of the above simulation results (see Table 4), it can be found that after each step of filling, the hidden dangers in the goaf can be eliminated in sequence, ultimately reaching a stable state without plastic zones. Among them, there are a large number of plastic zones in the goaf of the 220–500 m middle section without filling, and the 500 m middle has already been connected. After treatment, no plastic zone is found below the 528 m middle. With the continuous filling of the goaf, the displacement of settlement and the maximum and minimum principal stresses suffered by the goaf decrease to varying degrees, proving that the goaf has achieved its own stability after being filled with filling material, and its safety has significantly improved, fully demonstrating the necessity of filling the goaf.

Discussion

Mining plan with deep untouching the ore body

From the depth of 528 m to the lowest control elevation of 220 m of the ore body, it belongs to the non-moving ore body. According to the overall mining plan of the preliminary design, the deep non-moving ore body will be divided into three levels: 420–500 m, 300–390 m, and 260–290 m for mining, and the 500–528 m, 390–420 m, 290–300 m and 220–260 m ore bodies will be reserved as pillars.

According to the overall plan of mining by levels in the preliminary design of the mine, combined with the production capacity requirements of the lead-zinc ore level and the layout of the development system, there are four mining methods for the deep untouched ore body:

Interval mining plan 1 (mining scheme 1). First of all, mining 300–390 m untouched ore body, after mining, uses the non-cemented filling process to dispose of the goaf and eliminate the safety hazards of the goaf. Secondly, the 290–300 m range of the ore body is reserved as the bottom pillar, and the 390–420 m range of the ore body is reserved as the top pillar. Finally, the 260–290 m and 420–500 m untouched ore bodies shall be mined at the same time. After mining, the non-cemented filling process shall be used to dispose of the goaf to eliminate the safety hazards of the goaf.

Interval mining plan 2 (mining scheme 2). First of all, the 260–290 m and 420–500 m untouched ore bodies should be mined at the same time. After mining, the goaf should be treated with a non-cemented filling process to eliminate the safety hazards of the goaf. Secondly, the 290–300 m range of the ore body is reserved as the bottom pillar, and the 390–420 m range of the ore body is reserved as the top pillar. Finally, mining 300–390 m untouched ore body, after mining, uses the non-cemented filling process to dispose of the goaf and eliminate the safety hazards of the goaf.

Downward mining (mining scheme 3). First of all, mining 420–500 m untouched ore body, after mining, use the non-cemented filling process to dispose of the goaf and eliminate the safety hazards of the goaf; Secondly, the ore body within the range of 390–420 m shall be reserved as the top pillar, and the 300–390 m untouched ore body shall be mined. After the mining is completed, the goaf shall be disposed of by the non-cemented filling process to eliminate the safety hazards of the goaf. Finally, the 290–300 m range of the ore body is reserved as the top pillar, and the 260–290 m untouched ore body is mined. After mining, the non-cemented filling process is used to dispose of the goaf and eliminate the safety hazards of the goaf.

Upward mining (mining scheme 4). First of all, mining 260–290 m untouched ore body, after mining, use the non-cemented filling process to dispose of the goaf and eliminate the safety hazards of the goaf. Secondly, the 290–300 m range of the ore body is reserved as the bottom pillar, and the 300–390 m untouched ore body is mined. After mining, the non-cemented filling process is used to dispose of the goaf to eliminate the safety hazards of the goaf. Finally, the 390–420 m range of the ore body is reserved as the bottom pillar, and the 420–500 m untouched ore body is mined. After mining, the non-cemented filling process is used to dispose of the goaf to eliminate the safety hazards of the goaf.

Optimization of mining sequence

Scheme (1) Advantages: relatively large production capacity and relatively good safety of mining operation. Since the 300–390 m untouched ore body is mined first, the scale and reserves of this part of the ore body are relatively large, and relatively stable productivity can be formed at the initial stage. At the same time, because the 390–528 m ore body is temporarily set as the pillar, and the upper 528–610 m existing goaf has little disturbance to the 300–390 m untouched ore body mining, the safety of mining operation can also be effectively guaranteed.

Disadvantages: There are certain requirements for the construction organization, especially after the mining of 300–390 m untouched ore body and before the mining of 420–500 m untouched ore body, the filling and treatment of the upper 528–610 m existing goaf should be completed as soon as possible.

Scheme (2) Advantages: large production capacity. Since the 260–290 m untouched ore body and 420–500 m untouched ore body can be mined at the same time, a large production capacity can be formed at the initial stage. At the same time, because the 290–420 m ore body is used as the isolation layer, the mutual interference between the upper and lower levels is also small.

Disadvantages: it is difficult to guarantee the safety of mining operations. Due to the large scale of the existing goaf at the upper part of 528–610 m, the goaf has certain potential safety hazards, and the filling treatment needs at least 1–2 years. Therefore, when this mining scheme is used to mine 420–500 m of the unmoved ore body, the goaf is very easy to disturb the mining of the lower unmoved ore body, resulting in certain potential safety hazards.

Scheme (3) Advantages: relatively large production capacity. Since the 420–500 m untouched ore body is mined first, the scale and reserves of this part of the ore body are relatively large, and a relatively stable production capacity can be formed at the initial stage. At the same time, the downward mining scheme requires that the existing development system in the old upper part be fully utilized as the return air channel, which is conducive to reducing the development and mining preparation quantities.

Disadvantages: it is difficult to guarantee the safety of mining operations. Due to the large scale of the existing goaf at the upper part of 528–610 m, the goaf has certain potential safety hazards, and the filling treatment needs at least 1–2 years. Therefore, when the downward mining scheme is adopted to first mine the 420–500 m untouched ore body, the goaf is very easy to disturb the mining of the lower untouched ore body, resulting in certain potential safety hazards.

Scheme (4) Advantages: good mining safety. Because the upward mining method is adopted to first mine 260–290 m of undeveloped ore body, which is far away from the existing 528–650 m mined-out area, the mined-out area has little disturbance to the mining of deep undeveloped ore body, and the safety of mining operation can be effectively guaranteed. When the ore body is mined to 420–500 m, the existing goaf at the upper part of 528–610 m has been basically filled and treated, which can also effectively ensure the safety of mining operations.

Disadvantages: production capacity is relatively limited. Because the 260–290 m untouched ore body is mined first, the scale and reserves of this part of the ore body are relatively small, and the stability of production capacity cannot be guaranteed at the initial stage. At the same time, the upward mining scheme requires that the filling and treatment of the goaf should be completed after the mining is completed before the mining of the previous orebody can be carried out. Therefore, the length of the filling and treatment period of the goaf will also have a certain impact on the production capacity.

To sum up, according to the overall plan of mining by levels in the preliminary design of the mine, combined with the production capacity requirements of the lead-zinc ore level and the layout of the development system, it is recommended to adopt the mining scheme 1 for the deep untouched ore body (that is, first mining 300–390 m untouched ore body by filling method, then mining 260–290 m untouched ore body and 420–500 m untouched ore body by filling method), with relatively large production capacity The outstanding advantages of relatively good safety of mining operation26,27.

Through the comparison of the advantages and disadvantages, it can’t be explained that mining scheme 1 is the optimal scheme, and the roof subsidence will occur during the mining process. By analyzing the size of the roof subsidence displacement28 (see Fig. 14), which scheme is the best can be further explained. The monitoring points are arranged on the roof of 500 m level (p1), 390 m level (p2), and 290 m level (p3), the three roof models are all top views. Respectively, the monitoring is carried out according to the mining plan of each scheme, these three points only change the size of the Z-axis, and the X and Y-axis coordinates are both 150. It can be seen that the maximum displacement of mining scheme 2 and mining scheme 3 is more than 20 cm, and the settlement displacement of interval mining scheme 1 and mining scheme 4 is very small. The maximum settlement displacement is located on the roof of a 500 m level, and the value is about 8 cm. In order to achieve the mine production capacity, mining scheme 1 is still selected as the optimal scheme.

Chain theory of goaf disaster

The goaf at the level of 670–740 m in Suichang Gold Mine has been affected by the geological and geomechanical setting for a long time. The superposition of physical fields such as stress field, seepage field, temperature field, and chemical field will cause changes in the parameters of each field29, which will cause a response to the goaf state and feedback to the geological and geomechanical setting. This process is accompanied by the exchange of material and energy until the structure of the goaf becomes unstable, forming a dynamic and open complex disaster system.

The traditional model cannot explain why the stability improvement (62%) at the 610–650 m level after filling the 528–540 m level goaf (Scheme 2) far exceeds the single filling effect (theoretical value of 35%). However, this model reveals through the “hub radiation” mechanism that the filling body changes the stress field distribution, increasing the triggering threshold of adjacent areas by 2.3 times.

This study proposes a “dynamic threshold matrix” and establishes a quantitative relationship between different mining depths (220–740 m) and corresponding stability thresholds through orthogonal simulation experiments. By coupling the energy release degree with the volume of the plastic zone, it was found that when the energy release degree exceeds 0.6 and the volume of the plastic zone accounts for 30%, cross horizontal disaster transmission will occur (such as the impact of a 710 m goaf on a 528 m level). The accuracy of this criterion has been verified by on-site monitoring to be 89%. The filling scheme optimized based on disaster chain theory (using a 1:8 ratio for 528–540 m) has increased the success rate of disaster chain blockage by 28% compared to traditional schemes, and reduced filling costs by 15% (parameter optimization of low-strength filling bodies in Table 2).

A single factor will not cause instability and disaster in the goaf, and only under the coupling of multiple factors will instability occur, which is a complex nonlinear process30. These influencing factors have different levels and levels of convergence, and the number decreases with the aggregation of branches. If the degree of stress aggregation increases sharply, it will lead to the instability and damage of the goaf31. It is difficult to fully describe the instability process of goaf with a single disaster chain. Based on various analyses, the chain type of instability disaster in goaf has been drawn. (see Figs. 15, 16, 17).

The failure of the pillar and roof is an intuitive manifestation of instability32, which can be manifested as initial creep stage, steady-state creep stage, and accelerated creep stage33. For a large area of the goaf group, it is a continuous repetition of the instability and disaster process of a single goaf. Its deformation has obvious nonlinear characteristics and is always accompanied by energy accumulation and dissipation, the law of deformation, and energy evolution over time (see Fig. 18). During the process of instability and disaster in the goaf, energy presents a ‘rise and fall’ pattern. The wave-like increase in the figure shows that AB represents the stage of energy accumulation, BC represents the stage of energy release, and the shaded area represents the degree of energy release. The energy in each stage accumulates with the increase of stress and deformation. DE represents the initial deformation stage, EF represents the isokinetic deformation stage, FG represents the accelerated deformation stage, and G point represents the occurrence of damage, J and ɛ represent the maximum energy and strain accumulated in each goaf. When the goaf is damaged, the deformation increases sharply, and energy begins to be released Reaching relative equilibrium34,35. Each stage presents similar patterns of change, but as a single goaf continues to be destroyed, the rate of energy accumulation and final value gradually increases, and energy release becomes increasingly intense. The deformation also exhibits a similar development pattern.

The current goaf at 670–740 m level has entered the collapse stage, while the energy release rate at 528–610 m level is controlled below 0.3 after filling, which verifies the engineering applicability of the theoretical model. Continuous monitoring of the stress accumulation rate at the 610–650 m level is required in the future, and emergency filling should be initiated when it reaches 0.8 MPa/month.

So far, the goaf at the level of 670–740 m has been damaged, and filling treatment is being carried out at the level of 528–610 m. The stability of some goaf areas has been improved, and there have been no phenomena such as fragmentation or roof falls in the roadway. The stability of all filled areas remains to be observed in the future.

Conclusions

-

1.

The numerical simulation analysis of the upper ore body is carried out by Flac3D. The results show that after the cemented filling of the goaf at the level of 528–540 m, the scope of the damaged unit in the plastic zone is smaller than that without filling, the subsidence displacement of the level of 528–540 m is reduced by 2 cm, and the maximum compressive stress is reduced by 0.5 ~ 1 × 106 Pa, the minimum compressive stress of the side wall is reduced by 1.2 × 107 Pa, and there is no obvious tensile stress phenomenon, and the stability of the remaining goaf is slightly better than that of completely unfilled; After continuing the non-cemented filling in the level of 540–610 m, only a very small range of plastic failure units appeared. The filling body sank 6 ~ 8 cm, and the side wall of the goaf sank 4–6 cm, with little change from the previous one. The maximum compressive stress of the filling body is 1.2 × 106 Pa, minimum compressive stress is about 6 × 106 Pa, the ring-breaking unit of the model as a whole is significantly reduced, which alleviates the stress concentration phenomenon, which indicates that the goaf is more stable after filling treatment.

-

2.

The numerical simulation analysis of the deep untouched ore body is carried out by Flac3D. The results show that after the non-cemented filling of the level of 300–390 m, the subsidence displacement of the level of 420–00 m is reduced by 4 cm, and the maximum compressive stress of the goaf at the level of 260–90 m is reduced by 1 × 106 Pa, minimum compressive stress reduced by 5.5 × 106 Pa, the stable state is slightly better than that without filling; after non-cemented filling of 260–290 m and 420–500 m levels, there are few damage units in the filled goaf, and the subsidence displacement of the side wall of the goaf of 300–390 m level of is reduced by 1.5 cm, and the maximum compressive stress is reduced by 1 × 106 Pa; after all non-cemented filling, there is basically no damage unit below the level of 528 m. It shows that the goaf has achieved its own stability after being filled with the filling body, and its safety has been significantly improved.

-

3.

Through the comparative analysis of advantages and disadvantages and the overall mining plan, mining scheme 1(interval mining plan 1) has the outstanding advantages of relatively large production capacity and relatively good mining safety. At the same time, monitoring the settlement displacement of the roof in different schemes, the maximum displacement of the roof in scheme 1 and scheme 4 is about 8 cm, and the maximum displacement of the roof in scheme 2 and scheme 3 is about 20 cm. Based on comprehensive analysis, scheme 1 is still the best mining scheme, and adopting non cemented filling treatment scheme.

-

4.

This study clearly elaborates on three theoretical innovations: firstly, a disaster chain model for goaf based on the “trigger evolution result” framework, which compensates for the insufficient accuracy of traditional qualitative descriptions; The second is the proposed “dynamic threshold matrix”, which realizes the quantitative expression of multi field coupling triggering conditions; The third is to verify the adaptability of the “interval mining + graded filling” scheme in the treatment of high-level and large-span goaf, providing a theoretical paradigm for similar projects.

-

5.

The current model does not take into account the impact of time effects on the creep stage. In the future, the warning threshold can be optimized by combining acoustic emission monitoring technology; Suggest exploring real-time coupling methods between drone aerial survey and FLAC3D simulation to improve the timeliness of dynamic management of goaf clusters.

Data availability

All data generated and analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Dobak, P. & Gaszynski, J. Evaluation of soil permeability from consolidation analysis based on terzaghi’s and biot’s theories. GEOL. Q. 59 (2), 373–381 (2015).

Peng, D., Warnke, T., Haack, F. & Uhrmacher, A. Reusing simulation experiment specifications to support developing models by successive extension. SIMUL. MODEL. PRACT. TH. 68, 33–53 (2016).

Hu, B. et al. Application of numerical simulation methods in solving complex mining engineering problems in Dingxi mine. China Minerals. 12, 123 (2022).

Xiu, Z. et al. Numerical simulation study on dust pollution characteristics and optimal dust control air flow rates during coal mine production. J. Clean. Prod. 248, 119197 (2020).

Sun, Y. et al. Stability of roadway along hard roof Goaf by stress relief technique in deep mines: A theoretical, numerical and field study. Geomech Geophys Geo-energy Geo-resour. 8, 45 .

Xu, Z. et al. Research on coal mine Goaf restoration based on stability of overlying rocks and numerical simulation analysis: A case study of Jingmen garden expo park. Sustainability 15, 1464 (2023).

Bazyar, M. & Talebi, A. Transient seepage analysis in zoned anisotropic soils based on the scaled boundary finite-element method. Int. J. Mummer Anal. Met. 39 (1), 1–22 (2019).

Becker, P. & Idelsohn, S. A multiresolution strategy for solving landslides using the particle finite element method. Acta Geotech. 11 (3), 643–657 (2016).

Jiang, S., Li, D., Zhang, L. & Zhou, C. Slope reliability analysis considering spatially variable shear strength parameters using a non-intrusive stochastic finite element method. Eng. Geol. 168, 120–128 (2014).

Fang, S., Cheng, L. & Ayala, L. A coupled boundary element and finite element method for the analysis of flow through fractured porous media. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 152, 375–390 (2017).

Xiao, S., Yue, Z. & Xiao, H. Boundary element analysis of transversely isotropic bi-material halfspaces with inclined planes of isotropy and interfaces. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Met. 43 (17), 2599–2627 (2019).

Yan, X., Huang, Z., Yao, J., Li, Y. & Fan, D. An efficient embedded discrete fracture model based on mimetic finite difference method. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 145, 11–21 (2016).

Zhang, T., Yu, L., Su, H., Zhang, Q. & Chai, S. Experimental and numerical investigations on the tensile mechanical behavior of marbles containing dynamic damage. Int. J. Min. Sci. Techno. 32 (1), 89–102 (2022).

Shi, C., Li, D., Xu, W. & Wang, R. Discrete element cluster modeling of complex mesoscopic particles for use with the particle flow code method. Granul. Matter. 17 (3), 377–387 (2015).

Javili, A., Morasata, R., Oterkus, E. & Oterkus, S. Peridynamics review. Math. Mech. Solids. 24 (11), 3714–3739 (2019).

Chen, D., Chen, H., Zhang, W., Lou, J. & Shan, B. An analytical solution of equivalent elastic modulus considering confining stress and its variables sensitivity analysis for fractured rock masses. J. Rock. Mech. Geotech. Eng. 14 (3), 825–836 (2022).

Pan, P., Rutqvist, J., Feng, X. & Yan, F. An approach for modeling rock discontinuous mechanical behavior under multiphase fluid flow conditions. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 47 (2), 589–603 (2014).

Research report on the. Treatment Plan of Goaf in lead-zinc Mining area; Central South University (Changsha, China, 2022).

Rock mechanics study of I lead-zinc ore body in Suichang Gold Mine. Beijing General Research Institute of Mining and Metallurgy: Beijing, China, (2009).

Feasibility Study Report on Safe. Efficient and low-lean filling mining of high-grade gold and silver resources in Soft Rock Strata; Central South University (Changsha, China, 2021).

Liu, B. & Han, Y. H. FLAC principle, example and application guide (People’s Communications, 2002).

Peng, W. B. FLAC 3D practical course 2–180 (Machinery Industry, 2011).

Khayyer, A., Gotoh, H., Falahaty, H. & Shimizu, Y. An enhanced ISPH-SPH coupled method for simulation of incompressible fluid-elastic structure interactions. Comput. Phys. Commun. 232, 139–164 (2018).

Rutqvist, J., Wu, Y., Tsang, C. & Bodvarsson, G. A modeling approach for analysis of coupled multiphase fluid flow, heat transfer, and deformation in fractured porous rock. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. 39 (4), 429–442 (2002).

Zhou, L. & Hou, M. A new numerical 3D-model for simulation of hydraulic fracturing in consideration of hydro-mechanical coupling effects. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. 60, 370–380 (2013).

Yang, L., Li, J., Jiao, H., Wu, A. & Yin, S. Research on the homogenization evaluation of cemented paste backfill in the preparation process based on image texture features. Minerals 12 (12), 1622 (2022).

Yang, L., Jia, H., Jiao, H., Dong, M. & Yang, T. The mechanism of viscosity-enhancing admixture in backfill slurry and the evolution of its rheological properties. Minerals 13 (8), 1045 (2023).

Newman, C., Agioutantis, Z. & Leon, G. Assessment of potential impacts to surface and subsurface water bodies due to Longwall mining. IJMST 27, 57–64 (2017).

Jiang, C. et al. Occurrence and environmental impact of coal mine Goaf water in karst areas in China. J. Clean. Prod. 275, 123813 (2020).

Hu, Y. & Li, X. Bayes discriminant analysis method to identify risky of complicated Goaf in mines and its application. T Nonferr Metal Soc. 22 (2), 425–431 (2012).

He, L., Wu, D. & Ma, L. Numerical simulation and verification of Goaf morphology evolution and surface subsidence in a mine. Eng. Fail. Anal. 144, 106918 (2023).

Zhou, Y. et al. Research on catastrophic pillar instability in room and pillar gypsum mining. Sustainability 10 (10), 3773 (2018).

Li, W., Lu, X., Wu, R. & Wang, H. Evolution analysis of research on disaster-causing mechanism and prevention technology of mine Goaf disaster. Environ. Sci. Pollut R. 30 (41), 93388–93406 (2023).

Gao, R. et al. Ground fracturing of multi-strata for strong ground pressure control in extra-thick coal seams with hard roofs: Numerical simulation and case study. Eng. Fract. Mech. 303, 110129 (2024).

Gao, R., Kuang, T., Meng, X. & Huo, B. Effects of ground fracturing with horizontal fracture plane on rock breakage characteristics and mine pressure control. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 54 (6), 3229–3243 (2021).

Funding

Authors thank the financial support from the Major National Science and Technology Project for Deep Earth of China: Theory and Technology of Green Filling of Solid Waste with Strong Acid and Alkali (Grant No. 2024ZD1003808) and the Science and Technology Innovation Program of Hunan Province (Grant No. 2023RC3035).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Shuai Li, Shan Yang, Junyu Chen, Zhenyu Dan and Haoxuan Yu; Data curation, Junyu Chen, Shan Yang; Formal analysis, Shuai Li, Qi Huang and Junyu Chen; Funding acquisition, Shuai Li; Investigation, Shuai Li, Qi Huang, Shan Yang, Junyu Chen and Haoxuan Yu; Methodology, Shuai Li, Qi Huang and Shan Yang and Zhenyu Dan; Project administration, Junyu Chen, Shan Yang and Haoxuan Yu; Resources, Junyu Chen, Shan Yang, Zhenyu Dan and Haoxuan Yu; Software, Qi Huang and Shan Yang; Supervision, Shuai Li, Junyu Chen and Haoxuan Yu; Validation, Shuai Li, Junyu Chen and Haoxuan Yu; Visualization, Qi Huang and Shan Yang; Writing – original draft, Qi Huang; Writing – review & editing, Shuai Li, Shan Yang, Zhenyu Dan and Junyu Chen.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, J., Shan, Y., Li, S. et al. Research and engineering practice of high stage and long span complex goaf filling treatment technology. Sci Rep 15, 43033 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24224-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24224-z