Abstract

Soil organic carbon (SOC) is a key indicator of soil health, yet conventional laboratory assays are labor-intensive and costly. This study investigates a rapid and low-cost alternative by using a handheld Nix Spectro 2 Color Sensor, which captured high-resolution color data from air-dried soil samples. These color parameters were used to predict SOC with four data-driven prediction engines: Random Forest (RF), Gradient Boosting Regression (GBR), Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), and an Artificial Neural Network (ANN) and further strengthened them with synthetic data augmentation techniques. A total of 641 surface soil samples collected from six districts in West Bengal, India, were divided into 70% calibration and 30% validation subsets. Synthetic samples were produced using a combination of generative artificial intelligence (AI) techniques [generative adversarial networks (GANs) and Gaussian mixture models (GMM)] and non-parametric/statistical data augmentation methods [k-nearest neighbors (KNN) and bootstrapping] to fill critical gaps in the SOC range (3–14%). Among the baseline models using raw Nix color data, RF achieved the best validation accuracy (R² = 0.71, RMSE = 0.93%). After augmenting the calibration set with 44 GMM-generated samples (3–7% SOC), RF performance rose to R² = 0.77 and RMSE = 0.84%, while bias dropped and coverage across the SOC distribution improved markedly. The incorporation of synthetic data mitigated model bias and enhanced predictive accuracy despite Levene’s test revealing significant variance differences between calibration and validation datasets. The enhanced generalization of the model was attributed to better coverage of the SOC distribution, reducing underrepresented gaps in the dataset. The study highlighted the potential of AI-driven soil monitoring techniques in precision agriculture, demonstrating that integrating the Nix color sensor with synthetic data augmentation, provides a rapid and cost-effective solution for on-site soil assessments. Future research should expand these methodologies to multi-parameter soil assessments, digital soil mapping, and broader applications in sustainable soil management and climate change mitigation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Soil organic carbon (SOC) plays a central role in soil health, influencing soil structure, nutrient cycling, water retention, and overall agricultural productivity1. Accurate prediction and monitoring of SOC are essential for sustainable land management and climate change mitigation, as soils act as significant carbon sinks2. Additionally, SOC plays a key role in regulating various physical, chemical, and biological processes and is directly linked to many soil ecosystem services3,4. Traditional methods for SOC or soil organic matter measurement, such as dry combustion and wet oxidation, are accurate but time-consuming, labor-intensive, and costly5,6,7. Consequently, there is an increasing demand for rapid, non-destructive, and cost-effective techniques to estimate SOC content efficiently.

Recent advancements in proximal soil sensing technologies, such as visible and near-infrared (Vis-NIR) spectroscopy and colorimetry, have shown promise for SOC prediction8,9,10. Among these, the Nix color sensor has emerged as a portable and affordable tool for capturing soil color data, which correlates strongly with SOC content11,12,13,14,15,16,17. Researchers also demonstrated that combining Nix color sensor and portable X-ray fluorescence (XRF) data, along with soil horizon information, enables accurate, eco-friendly prediction of soil organic matter in diverse soils using machine learning models18. Moreover, particularly with moist samples, Nix color sensor, combined with the random forest (RF) model, provided accurate and reliable prediction of soil organic matter in arid and semiarid regions, outperforming linear regression, especially in semiarid areas19. Unlike earlier versions of the Nix sensor, which did not capture spectral data, the advanced Nix Spectro 2 offers over ten times the resolution of a standard colorimeter. This higher resolution minimizes gaps between channels, enabling more precise measurements across the visible spectrum (400–700 nm). The Nix Spectro 2 is a compact, handheld device engineered for accurate color measurement and digital color matching. It operates by illuminating a surface with an internal light source and capturing the reflected light to determine precise color values across multiple color spaces, making it highly versatile for various applications.

Soil color, an important physical property, serves as a diagnostic criterion in Soil Taxonomy20 and a key indicator of soil composition, processes and health21,22. In the visible spectrum, soil color is primarily influenced by organic matter content, mineral composition, and moisture, making it a viable proxy for SOC estimation7,23,24,25. For instance, darker soils often indicate higher organic matter content due to the presence of humic substances, while reddish hues may reflect iron oxide dominance16. However, the accuracy of SOC prediction models often depends on the availability of large and diverse datasets, which are challenging to obtain due to the variability of soil properties across different regions and scales. For instance, Padarian et al.26 compared deep learning models with conventional machine learning approaches, such as Cubist, for predicting SOC using a large dataset. Their findings indicated that the deep learning models performed better with larger datasets but showed reduced accuracy and predictive performance with smaller, localized datasets. Models like RF and Cubist, using soil and environmental data, effectively predicted SOC distributions27. Similarly, support vector machines have been compared to ordinary kriging for SOC prediction, demonstrating their potential to handle complex pedo-geomorphometric data in site-specific management28.

To address this data limitation, a combination of generative artificial intelligence (AI) techniques [generative adversarial networks (GANs) and Gaussian mixture models (GMM)] and non-parametric/statistical data augmentation methods [k-nearest neighbors (KNN) and bootstrapping], have been increasingly employed to generate synthetic data for augmenting existing datasets29,30. These methods can enhance the robustness and generalizability of predictive models by simulating a wider range of soil conditions and properties31. For instance, GANs have been successfully used to generate synthetic spectral data for soil analysis, improving the performance of machine learning models in scenarios with limited training data32. Bai et al.33 used super-resolution lightweight generative adversarial network (SLRGAN) for enhancing soil computed tomography (CT) image quality. Similarly, bootstrapping techniques have been applied to create diverse datasets by resampling and perturbing existing data, thereby reducing overfitting and improving model accuracy34.

This study aimed to enhance SOC prediction accuracy by integrating Nix Spectro 2 color sensor (Nix Sensor Ltd., Ontario, Canada) data with generative AI and non-parametric/statistical data augmentation techniques, including GMMs, KNNs, GANs, and bootstrapping. By utilizing the strengths of Nix Spectro 2 color data and advanced generative techniques, the objective of this study was to develop a robust and scalable framework for SOC estimation that can be applied across diverse agricultural and environmental contexts. The integration not only addresses the data scarcity challenges but also offers a cost-effective and efficient solution for large-scale soil monitoring and management, supporting data-driven decision-making in sustainable and precision agriculture. Enhancing SOC prediction enables better soil fertility assessments, optimized fertilizer application, and improved carbon sequestration strategies, contributing to long-term soil health and climate resilience. The explicit hypothesis of this study was that the integration of high-resolution soil color data from the Nix Spectro 2 sensor with synthetic data augmentation techniques would significantly improve the predictive performance and robustness of SOC estimation models. The novelty of this study lay in combining high-resolution visible color data from the Nix Spectro 2 sensor with multiple generative AI techniques and statistical data augmentation techniques, including GANs, GMM, KNN, and bootstrapping to enhance the accuracy and generalizability of SOC prediction models. This approach was among the first to integrate a low-cost, portable color sensor with synthetic data generation methods to overcome data scarcity, providing a scalable, eco-friendly, and cost-effective solution for soil monitoring across diverse agro-environmental contexts.

Results and discussion

Overview of soil organic carbon content and Nix extracted color parameters

Table 1 summarizes the SOC content across six districts in West Bengal, India. The highest mean SOC content was observed in South 24 Parganas (2.57%), with significant variability [coefficient of variation (CV): 88.22%]. This variation was likely due to the coastal saline soils, which are influenced by tidal activity and experience slow organic matter decomposition under anaerobic conditions35,36. Darjeeling followed with a mean SOC of 2.12%, indicating its rich organic matter content due to favorable climatic and soil conditions in the hilly region37. In contrast, Jhargram (0.62%) and Birbhum (0.65%) had the lowest mean SOC values, indicative of lateritic soils with poor fertility and high weathering38. The alluvial soils of Nadia and East Medinipur showed moderate to high SOC levels (0.80% and 0.90%, respectively), signifying intensive agriculture and application of organic amendments in rice fields39. Notably, the trend of SOC distribution closely aligned with findings reported by Swetha and Chakraborty16. Overall, the variation in SOC across districts highlighted the influence of soil type, climate, and land use on carbon storage40.

The variability in Nix-extracted color parameters across the collected samples reflected significant differences in soil composition, SOC content, and mineralogical properties. L* values ranged from approximately 42.77 to 73.77, with a mean of 57.46, indicating a gradient from darker, organic-rich soils in Darjeeling to lighter, mineral-dominated lateritic soils. The a* and b* values exhibited broad ranges (0.88–9.41 and 9.37–34.16, respectively), capturing changes due to Fe-oxides, organic matter, and soil moisture. Chroma (c), representing color intensity, varied between 9.42 and 34.38, suggesting a mix of light and highly pigmented soils. The hue (h), ranging from 64.43 to 85.00, indicated different dominant color tones across the samples.

The additional color parameters provided further insight into soil reflectance characteristics. The XYZ color space components (X: 0.13–0.36, Z: 0.05–0.22) highlighted differences in brightness and chromaticity, while the sRGB values (R: 114.67–187.00, G: 97.67–157.33, B: 64.33–129.67) captured variations in soil color as perceived in digital imaging. The CMYK values (C: 27.00–48.67, M: 34.00–55.00, Y: 45.00–83.00, K: 1.33–15.67) further emphasized differences in soil pigmentation, with higher K values indicating darker soils and greater organic matter content. Sugita and Marimo41 concluded that soil color is a reliable indicator of SOC variability and the distinct visual differences in the soil matrix color observed in this study likely reflected variations in SOC content.

Prediction model performance using Nix color and spectral data

The performance of four algorithms (RF, GBR, XGBoost, and ANN) in predicting soil SOC using Nix-extracted color and spectral parameters is shown in Table 2. Among all the models tested, the RF model using the color data exhibited the highest predictive accuracy (validation R²=0.71, RMSE = 0.93%, bias = 0.10%, and RPIQ = 1.16). While many of the color variables reported by the Nix sensor can be converted interchangeably using mathematical transformations42, combining all these variables may have supplied enough information to establish decision tree rules in the RF models. Both GBR and XGBoost demonstrated moderate predictive power, with validation coefficients of determination values of 0.64 and 0.66, respectively. Conversely, ANN produced the lowest predictive accuracy (validation R² = 0.60 and validation RMSE = 1.10%). Nevertheless, for spectral data, ANN outperformed the other algorithms, achieving a validation R² of 0.68 and a validation RMSE of 0.98%, indicating that Nix-extracted spectral data can also be used to moderately predict soil SOC content. In contrast, the performance of the RF model declined when using spectral data (validation R² = 0.61, validation RMSE = 1.09%). Notably, the GBR model maintained consistent performance across both datasets (validation R² = 0.64), while the XGBoost algorithm exhibited the weakest predictive ability for spectral data (validation R² = 0.54, validation RMSE = 1.18%). These results corroborated the earlier studies11,12,13,14,15,16,17 exhibiting the usefulness of Nix sensor for soil SOC prediction.

The observed differences in model performance between color and spectral datasets may also be partly attributed to the number of input features and redundancy among them. The color dataset included multiple interrelated color parameters [e.g. CIELAB L*a*b*, c, h, X, Z, sRGB, CMYK], many of which are mathematically convertible, potentially leading to high feature redundancy. While ensemble methods like RF can tolerate such redundancy by randomly selecting subsets of features at each split, models with many trainable parameters such as ANN may be more susceptible to overfitting under such conditions. In contrast, the spectral dataset (400–700 nm, 31 bands) provides more orthogonal, uniformly spaced reflectance data, which may better support gradient-based learning in ANN models. These differences highlight the role of input dimensionality and feature correlation structure in determining model behavior and predictive accuracy. Figure 1 presents the measured SOC vs. Nix-color and spectra-predicted SOC using the RF model using the 30% validation set. In both plots, underestimations were observed for SOC values > 3%, possibly due to the limited number of samples in the higher SOC range. Additionally, an assessment of SOC variance homogeneity between the training and validation sets using Levene’s test revealed a significant difference in variance (Levene’s Statistic: 52.29, p-value: 1.37 × 10⁻¹²). This indicated that the distribution of SOC in the training dataset was not representative of the validation dataset, which could lead to biased model predictions. This variance difference further highlighted the limitations of the original dataset in covering diverse SOC levels, advocating the need for synthetic data augmentation to balance SOC distribution.

Moreover, the bootstrapping results showed that for color data, RF had achieved the highest mean validation R² (0.72) and lowest mean validation RMSE (0.90%), indicating robust predictions, followed by GBR with a mean validation R² of 0.66 and a mean validation RMSE of 0.99%, while XGBoost and ANN had exhibited lower performance (mean validation R² of 0.60 and 0.59, mean validation RMSE of 1.03% and 1.08%, respectively) (Table 3). For spectral data, ANN had outperformed other models with a mean validation R² of 0.70 and a mean validation RMSE of 0.92%, followed closely by GBR (mean validation R² = 0.65, mean validation RMSE = 0.99%), whereas RF and XGBoost had shown weaker performance (mean validation R² of 0.55 and 0.58, mean validation RMSE of 1.15% and 1.10%, respectively). These findings confirmed RF’s superior stability for color data and ANN’s robustness for spectral data, with bootstrapped metrics closely aligned with the original validation results (Table 2), reinforcing the models’ reliability despite data variability and non-linear relationships.

Figure 2 presents the relationship between soil SOC and the color parameters obtained from the Nix sensor, including L*, a*, and b* values. Higher SOC results in darker soil due to the presence of light-absorbing humic substances25, which explained the negative Pearson’s correlation between SOC and b* (yellow component) and the positive association between SOC and Z (dark intensity) and sRGB B (blue intensity). Furthermore, since soils with higher SOC show a shift in color tone towards a darker spectrum, the present study observed a positive Pearson’s correlation between SOC and h. Surprisingly, L* and SOC exhibited a positive Pearson’s correlation, which may possibly be attributed to the presence of some low-SOC, Fe-rich lateritic soils that appeared darker (lower L*) due to Fe-oxide coatings. Comparable trends may arise due to the potential presence of dark-colored parent materials, such as amphiboles or basalt, as observed in previous studies16,43. Another possible reason could be the presence of calcareous or silty soils with high SOC content which can still impart lighter color due to the presence of highly reflective minerals like carbonates and quartz. Indeed, Spielvogel et al.44 showed that the soil lightness can be influenced by several factors apart from SOC. Furthermore, Cardelli et al.45 observed that soil color variations can be influenced by the degree of organic matter decomposition. The negative association between SOC and a* supported the results of Stiglitz et al.11 (r=−0.62), Mikhailova et al.13 (−0.85), Mukhopadhyay et al.15 (−0.77), Mukhopadhyay and Chakraborty14 (r=−0.47), and Swetha and Chakraborty16 (r=−0.62). Figure 3 illustrates the Pearson’s correlation between soil SOC and spectral reflectance (400–700 nm) from the Nix sensor. The Pearson’s correlation coefficient decreased progressively across this range perhaps due to strong organic matter absorption in the blue (400–500 nm) regions, leading to lower reflectance. Notably, Hermansen et al.46 detected peaks near 487, 608, and 649 nm, which were associated with soil SOC content. Contrariwise, at higher wavelengths, reflectance became less sensitive to SOC and was more influenced by Fe-oxides (hematite, goethite) and clay minerals47.

Performance of generative AI algorithms

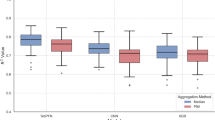

To enhance model robustness and mitigate data limitations, especially in the 3–14% SOC range, synthetic data augmentation was performed using GMM, GANs, KNN, and bootstrapping. The impact of synthetic data on SOC prediction performance was assessed based on R² and RMSE values across different sample sizes and SOC ranges (Figs. 4 and 5). Among the generative AI techniques, GMM-generated 44 filtered samples (5000 sample model, 3–7% SOC model) integrated with the training dataset yielded the highest improvement in model validation performance. The RF model trained on this dataset achieved a validation R² and RMSE of 0.77 and 0.84%, respectively, demonstrating a notable improvement over the best model trained on original color data alone (validation R²=0.71 and RMSE = 0.93%) (Fig. 1). Similarly, KNN generated 64 filtered samples (4000 sample model, 3–9% model) improved the model validation performance (R2 = 0.76, RMSE = 0.85%). The heatmaps of R² and RMSE indicated that synthetic data augmentation contributed to significant performance gains, particularly when SOC ranges were well-represented in the generated data (Figs. 4 and 5). Figure 6 exhibits the measured SOC vs. Nix-extracted soil color predicted SOC using the best GMM model via the RF algorithm.

Heatmap of validation R² values (30% original validation set) across four models (gaussian mixture model (GMM), generative adversarial networks (GANs), k-nearest neighbors (KNN), and bootstrapping), sample sizes, and soil organic carbon (SOC) ranges. Here the model was trained using the 70% calibration + filtered synthetic data.

Heatmap of validation root mean squared error (RMSE) values (30% original validation set) across four models (gaussian mixture model (GMM), generative adversarial networks (GANs), k-nearest neighbors (KNN), and bootstrapping), sample sizes, and soil organic carbon (SOC) ranges. Here the model was trained using the 70% calibration + filtered synthetic data.

Notably, while the addition of GMM or KNN synthetic data with the original 70% calibration set did not increase the SOC variance homogeneity between calibration and validation sets [Levene’s test p-values: 1.16 × 10⁻¹⁷ and 3.79 × 10⁻²⁰ for GMM and KNN-filtered data, respectively], it still enhanced model validation performance for several reasons. Firstly, the original calibration set showed gaps in the SOC range, particularly between 3 and 14%, which was filled by GMM and KNN, making the dataset more representative to the real-world variability. Consequently, the RF model learned from a more continuous and diverse dataset, reducing prediction bias in previously underrepresented regions. This improvement is attributed to the ensemble’s exposure to a broader range of data patterns, enabling it to generalize better across various scenarios. For instance, Liu and Mazumder48 empirically demonstrated that RF could reduce model bias over bagging by uncovering hidden patterns in the data. Moreover, Table 4 presents the impact of synthetic data on skewness and kurtosis, revealing that the original calibration dataset exhibited high skewness (2.80) and kurtosis (8.85), indicating a right-skewed distribution with heavy tails. This trend suggested the presence of outliers and an uneven spread of SOC values in original calibration dataset. After adding 44 GMM-generated samples (5000 sample model, 3–7% SOC), the skewness significantly dropped to −0.61, and kurtosis reduced to 0.75, indicating a more symmetric and balanced distribution with fewer extreme values. The 64 KNN-enhanced dataset (4000 sample model, 3–9% SOC) further reduced skewness (−0.38) and kurtosis (−0.40), making the data even more normally distributed. However, the bootstrap-enhanced dataset (1000 sample model, 3–4% SOC) still retained moderate skewness (0.76) and a relatively high kurtosis (6.59), suggesting that while it improved data distribution to some extent, it did not fully mitigate the heavy tail effect. Overall, the GMM and KNN models were most effective in normalizing data distribution, potentially leading to better model performance and generalization in SOC prediction tasks. Notably, for samples with SOC > 3% in the 30% validation set, the mean relative bias was 5.30% in the original model (70% calibration set) and 4.72% in the augmented model (70% calibration + 44 GMM-filtered samples). This indicated that incorporating synthetic data effectively reduced bias and improved prediction accuracy in the sparse region.

Further, Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) tests were performed to quantitatively assess the similarity between real and synthetic data distributions for key features (e.g., L*, a*, b*, and SOC). The KS statistic measures the maximum distance between cumulative distribution functions, with p-values > 0.05 indicating no significant difference. For GMM (5000 samples, 3–7% SOC)-generated filtered data, KS tests showed high similarity (e.g., KS statistic 0.06, 0.1, 0.15, and 0.07 for L*, a*, b*, and SOC, respectively), confirming that synthetic distributions closely mirrored real ones without amplifying biases.

Practical implications and limitations

This study highlights the practical impact of integrating Nix color sensors with AI-driven synthetic data augmentation for efficient and scalable SOC estimation. By combining generative models such as GMM and statistical data augmentation techniques like KNN with RF, the approach improved prediction accuracy, particularly in areas with limited soil sampling due to logistical or financial constraints. The success of the Nix sensor as a cost-effective, portable alternative to traditional soil testing highlights its potential for on-site assessments, supporting farmers, agronomists, and environmental scientists in soil health monitoring and carbon sequestration efforts.

Synthetic data generation further improved model performance by addressing data scarcity and ensuring a more representative training set, an important advancement for agricultural research and land management. Beyond SOC estimation, this approach can be extended to predicting soil nutrients, moisture content, and other soil properties, thus supporting digital soil mapping for sustainable land use and climate change mitigation. Overall, the integration of Nix sensors, machine learning, and synthetic data augmentation methods offers a transformative, data-driven solution for precision soil monitoring, promoting smarter and more sustainable soil management practices.

A further advantage of the Nix sensor lies in its simplicity of operation and data interpretation compared to traditional analytical platforms such as Vis-NIR, mid infrared (MIR), or XRF. While conventional spectroscopy generates complex, high-dimensional data requiring extensive preprocessing and domain expertise, the Nix sensor directly outputs standardized, easy-to-understand color parameters that can be used immediately for modeling. This makes the system highly accessible to non-specialists and well-suited for rapid, on-site soil assessments in field settings, promoting wider adoption in operational soil health monitoring frameworks.

Despite the promising results obtained in this study, certain limitations exist in the approach that must be addressed for broader applicability. The reference SOC values in this study were obtained with the classical Walkley–Black (WB) wet-oxidation method. Although inexpensive and widely adopted, WB typically oxidises only 60–86% of the total organic carbon, and its repeatability can vary by 5–15% depending on soil type and operator technique. That analytical noise propagates directly into the response variable used for model calibration and validation, placing an upper bound on achievable predictive accuracy. To mitigate this limitation, this study employed ensemble algorithms (RF, XGBoost, GBR) that are known to be more tolerant of label noise. Future work should consider calibrating models against dry-combustion (e.g., LECO) measurements or applying published WB recovery factors (≈ 1.21–1.33) to correct systematic under-oxidation, which could further improve model performance and generalisability. Moreover, the reliance on Nix-extracted color parameters for SOC prediction may limit the model robustness, particularly in soils with similar color characteristics but varying organic matter composition due to variations in parent material, mineralogy, or moisture content. To overcome these limitations, future research could explore hybrid generative models, such as combining GANs with physics-informed data augmentation techniques, to improve the representativeness of synthetic samples. For instance, Subramaniam et al.49 developed a Turbulence Enrichment GAN (TEGAN) that integrates physical constraints into the learning process to enhance turbulence modeling.

Additionally, incorporating multispectral and hyperspectral imaging data alongside Nix-derived color metrics could further improve prediction accuracy by capturing more detailed soil spectral signatures14. Another potential improvement involves employing domain adaptation techniques to align calibration and validation datasets better, reducing variance differences and improving model generalizability. Finally, expanding synthetic data augmentation to incorporate additional essential soil properties could also facilitate the development of comprehensive digital soil mapping frameworks, fostering a more integrated approach to precision agriculture and sustainable land management.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated the potential of integrating Nix color sensor with a combination of generative artificial intelligence (AI) techniques and non-parametric/statistical data augmentation methods to improve SOC prediction. By combining Nix-extracted soil color parameters with machine learning models, particularly RF, the approach provided a cost-effective and scalable alternative to traditional soil testing methods. Among the tested data augmentation approaches, the best-performing models, GMM (5000-sample model, 3–7% SOC) and KNN (4000-sample model, 3–9% SOC) resulted in significant improvements in validation performance. The incorporation of synthetic data reduced model bias and increased the predictive accuracy of SOC estimation. Despite Levene’s test indicating significant variance differences between calibration and validation datasets, the model’s validation performance improved due to the enhanced coverage of SOC distribution, thereby reducing gaps in underrepresented regions. In summary, this study highlighted the practical applicability of AI-driven soil monitoring techniques in precision agriculture. The Nix Spectro 2 color sensor, combined with synthetic data augmentation, offered a rapid and affordable solution for on-site soil assessments, enabling more informed land management and carbon sequestration strategies. Future research should focus on extending these methodologies to multi-parameter soil assessments, digital soil mapping, and broader applications in sustainable land management and climate change mitigation.

Methods

Study site description, soil sampling and processing

A total of 641 surface (0–20 cm depth) soil samples were collected from six districts in West Bengal, India, representing four distinct soil types with varying physical and chemical characteristics50 (Fig. 7). The red and lateritic soils (n = 164), collected from Birbhum and Jhargram districts, originate from weathered Precambrian metamorphic rocks, primarily granite gneisses and schists, with significant laterization due to intense weathering and leaching. These soils are acidic, low in N, but rich in Fe and Al oxides51. Prone to erosion, they require amendments such as lime and organic matter to enhance fertility. This region falls under the tropical wet and dry climate (Aw) in the Köppen classification, characterized by distinct wet and dry seasons52. The Alluvial soils (n = 105), collected from the Gangetic plains of Nadia and East Medinipur districts, are derived from recent Quaternary alluvium deposited by the Ganges River system. These soils are fertile and rich in K but often deficient in N and P, supporting intensive agriculture, particularly rice (Oryza sativa), wheat (Triticum aestivum), and jute (Corchorus olitorius). The region has a humid subtropical climate (Cwa), with hot summers, mild winters, and monsoonal rainfall. Hilly soils (n = 55), collected from the Darjeeling Himalayan region, originate from highly weathered metamorphic rocks of the Lesser Himalayas, predominantly schists and phyllites. These well-drained, slightly acidic soils are rich in organic matter, making them suitable for tea plantations (Camellia sinensis), cardamom (Elettaria cardamomum), and horticultural crops. The area experiences a subtropical highland climate (Cwb), characterized by cool summers, mild winters, and year-round moderate rainfall. Lastly, coastal saline soils (n = 317), collected from the South 24 Parganas district, are formed from Holocene marine and estuarine sediments, heavily influenced by tidal activity and mangrove ecosystems. These highly saline, poorly drained soils are low in essential nutrients, limiting agricultural productivity to salt-tolerant crops such as rice and mangrove vegetation. This region falls under the tropical monsoon climate (Am), marked by high humidity, heavy rainfall, and a distinct monsoon season.

Soil samples were collected during November-December 2019 and 2020 from fallow rice fields using both random and grid sampling (grid size: 5000 m2) with a Garmin e-trex global positioning system device for geolocation17,52, maintaining a minimum distance of 500 m between samples. Four subsamples were collected using a hand trowel to create a composite sample. The samples were subsequently air-dried, ground, and sieved through a 2-mm mesh before being stored in labeled plastic bags for laboratory analysis.

Soil analysis and Nix scanning

In the laboratory, SOC was measured using the chromic acid oxidation method5. Subsequently, the Nix Spectro 2 color sensor (version# F2.0.0; HW H3.2.6; SW S1.0.0; Nix Sensor Ltd., Hamilton, Ontario, Canada) (hereinafter referred to as ‘Nix’) was used to scan air-dried and ground soil samples to collect both color and spectral data across the visible spectrum (400–700 nm). Carvalho et al.53 previously established that dry sample scanning with the Nix sensor out-performs moist sample scanning. Each soil sample was placed in a glass Petri dish, levelled using a metal spatula, and scanned from the top using the Nix sensor (dimensions: 45 mm × 60 mm × 60 mm; Fig. 8). The sensor operated with a 45º:0º ring illumination optical geometry, ensuring accurate reflectance measurements. It utilized a high-color rendering index, broad-spectrum light emitting diode (LED) light source (including white, violet, and ultraviolet (UV) LEDs) to illuminate the sample and capture consistent colorimetric and spectral reflectance data. The measurement port had a diameter of 16 mm, with a 6 mm diameter illumination spot size and a 5 mm diameter measurement aperture for precise scanning.

For each sample, three scans were performed and averaged to minimize variability and improve measurement accuracy. Every 10 samples, the Nix sensor was calibrated using a ceramic reference tile provided by the manufacturer (Figs. 8a and b). This calibration was performed by placing the device on the tile and initiating a scan through the Nix Toolkit mobile application (version 1.8.2) on a Samsung Galaxy F15 5G smartphone. The app’s automated calibration process adjusted the sensor’s internal settings to account for potential drifts in the light source or sensor response due to environmental factors, ensuring consistent measurements across CIEXYZ, CIELAB, LCh, sRGB, and CMYK, and spectral (400–700 nm) data outputs. This recalibration maintained high measurement repeatability (< 0.05 ΔE00 on white at 23 °C) and inter-instrument agreement (0.35 ΔE00 average, 0.7 ΔE00 max.), as specified by the manufacturer.

The CIEXYZ color space, developed by the International Commission on Illumination54, represents color as a linear combination of three primaries (X, Y, Z) based on human vision, where Y indicates luminance. CIELAB (L*a*b*) is a perceptually uniform color space derived from CIEXYZ, where L* represents lightness, a* represents the green–red axis, and b* represents the blue–yellow axis, making it well suited for accurate color differentiation. LCh is a cylindrical transformation of CIELAB, where L represents lightness, C stands for chroma (color intensity), and h denotes hue (angle on the color wheel), offering an in-built way to represent color variations. The sRGB (Standard Red Green Blue) color model is a widely used additive color space used in digital displays such as computer monitors, televisions, and cameras. It defines colors using three primary components: Red (R), Green (G), and Blue (B), which combine in varying intensities to create a broad range of colors. In contrast, the CMYK (Cyan, Magenta, Yellow, Black) is a subtractive color model used in printing, where colors are produced by combining different amounts of ink to absorb specific wavelengths of light, with black (K) added to increase depth and contrast. Each of these color spaces serves specific roles, from digital imaging and printing to precise scientific color measurement.

The USB-C rechargeable Li-polymer battery supported over 1,000 scans per charge, making it suitable for large-scale soil analysis. The spectral and color data obtained from the Nix were subsequently used to predict SOC.

Prediction modelling

To develop predictive models for SOC content, four algorithms: RF, extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost), gradient boosting regression (GBR), and artificial neural network (ANN) were implemented. All analyses were performed using Python version 3.12.1. The entire dataset was randomly split into a calibration set (70%) for model training and a validation set (30%) for performance evaluation. The models were trained separately using Nix-extracted color data and spectral data to evaluate their predictive capabilities.

RF is an ensemble learning method that constructs multiple decision trees during training and aggregates their outputs to enhance prediction accuracy and reduce overfitting55. The RF model was implemented using the RandomForestRegressor from scikit-learn. Hyperparameter tuning was performed using a grid search with 5-fold cross-validation on the 70% training set. The hyperparameter space included: number of estimators (100, 200), maximum tree depth (None, 10, 20, 30), minimum samples per split (2, 5, 10), minimum samples per leaf (1, 2, 4), and bootstrap sampling (True, False). The optimal combination was selected by maximizing the mean R² across the 5 cross-validation folds. The final RF model was retrained on the full training set using the selected parameters and evaluated on the 30% validation set.

XGBoost is an advanced gradient boosting method that incorporates regularization and parallel computing to improve prediction accuracy and prevent overfitting56. XGBoost was implemented using the XGBRegressor from the xgboost Python package with the reg: squarederror objective function. Hyperparameter tuning was carried out using grid search with 5-fold cross-validation on the training set. The parameter space included: number of estimators (100, 300, 500), learning rate (0.01, 0.1, 0.3), maximum tree depth (3, 6, 9), minimum child weight (1, 3, 5), and subsample ratio (0.6, 0.8, 1.0). The best configuration was selected based on the highest average R² across the 5 cross-validation folds. The final model was retrained using the selected parameters on the full training set and tested on the 30% validation set. GBR, another ensemble learning method, builds trees sequentially by correcting the residual errors of previous trees57. The GBR model was implemented using scikit-learn’s GradientBoostingRegressor. Grid search with 5-fold cross-validation was used to identify the best hyperparameters from the following space: number of boosting stages (100, 200, 300), learning rate (0.01, 0.1, 0.2), maximum tree depth (3, 5, 7), minimum samples per split (2, 5, 10), and minimum samples per leaf (1, 2, 4). Model selection was based on the highest mean R² during five-fold cross-validation. The final model was retrained on the full training data and evaluated on the 30% validation set.

Finally, the ANN model was implemented using the MLPRegressor from scikit-learn with a rectified linear unit (ReLU) activation function and the Adam optimizer. The architecture consisted of two hidden layers, and hyperparameters were tuned using grid search with 5-fold cross-validation. The search space included: number of hidden neurons [(100, 50), (200, 100), (300, 150)], learning rate (0.001, 0.01, 0.1), and maximum iterations (500, 1000, 2000). The best configuration was selected based on the highest mean R² from 5-fold cross-validation. The final ANN model was trained on the full training set and validated on the 30% hold-out data.

Prior to modeling, all predictor variables (both color and spectral features) were standardized using z-score normalization via the StandardScaler module in Python’s scikit-learn library. This transformation included mean centering and scaling to unit variance, which is a widely recommended preprocessing step to ensure that all features contribute equally to the learning process, particularly for algorithms like ANN that are sensitive to feature scale. Model performance was assessed using the R², RMSE (Eq. 1), bias (Eq. 2), and the ratio of performance to inter-quartile distance (RPIQ) of the 30% validation set (Eq. 3). To ensure reproducibility of results, a fixed random seed (random_state = 42) was used throughout the modeling pipeline, including calibration–validation splitting and model initialization. This allowed for consistent performance across repeated runs.

In the aforementioned equations, \(\:{y}_{i}\) and \(\:{m}_{i}\) are the actual and predicted values for the i-th observation, n is the total number of samples, and Q1 and Q3 are the first and third quartile of the observed values, respectively. Additionally, Levene’s test was performed to check the homogeneity of variance among calibration and validation sets for SOC14. The test evaluates the null hypothesis that the variances of the groups being compared are equal. In this case, the two groups were the SOC values in the training (70%) and validation (30%) sets. Levene’s test is a robust, non-parametric alternative to Bartlett’s test and is less sensitive to deviations from normality, making it suitable for datasets like SOC that may exhibit skewness or kurtosis. The test calculates the absolute deviations of each observation from its group mean (or median) and then performs an ANOVA on these deviations to determine if group variances are significantly different. A low p-value (typically < 0.05) indicates a rejection of the null hypothesis, suggesting unequal variances across groups.

Furthermore, Bootstrapping was applied to assess the robustness and stability of model predictions on the validation dataset. This non-parametric resampling method estimates the sampling distribution of performance metrics by repeatedly drawing samples with replacement from the observed data. In this analysis, the actual and predicted SOC values from each model (using both color and spectral data) were jointly resampled to form new validation sets of equal size. For each resample, the R² and RMSE were computed. This process was repeated 1000 times to generate empirical distributions of R² and RMSE, from which mean values were derived.

Synthetic data generation

To enhance model robustness and address data scarcity in the 3–14% SOC range, synthetic data were generated using four distinct methods: GMM, GANs, KNN, and bootstrapping applied to the 70% calibration dataset (n = 449). Each method produced synthetic samples comprising both Nix color features (e.g., CIELAB L*a*b*, c, h, X, Z, sRGB, CMYK) and SOC values as a single multivariate vector to preserve their intrinsic relationships, as observed in Fig. 2.

GMM modeled the joint distribution of color features and SOC values as a weighted sum of multivariate Gaussian distributions (Eq. 4)58.

where x is the feature vector (color features and SOC values), Πk is mixing coefficient of the k-th Gaussian component (\(\:\sum\:_{k=1}^{K}{\varPi\:}_{k}=1\)), and N(x | µk, Σk) represents the multivariate Gaussian distribution:

where µk is the mean and Σk is the covariance matrix for component k. A GMM with 10 components was fitted using the Expectation-Maximization algorithm in Python’s scikit-learn library. Synthetic samples were generated by randomly sampling from the learned distribution, producing vectors [color features, SOC]. This joint modeling ensured that correlations, such as the negative correlation between SOC and a* (r=−0.62, Fig. 2), were preserved, and the probabilistic sampling guaranteed unique samples.

Next, GANs were employed to generate high-quality synthetic samples by using deep learning architectures29. The GAN framework consists of two neural networks: a generator [G(z)] and a discriminator [D(x)]. The generator learns to create realistic synthetic data points, while the discriminator evaluates the authenticity of these generated samples. Through an adversarial training process, the generator progressively improves, producing data points that closely resemble real samples. The generator network takes in a random noise vector z∼pz(z) and transforms it into synthetic data xgen (Eq. 6):

Finally, GANs are trained using the following adversarial loss function (Eq. 7):

In this study, GANs were implemented using a multilayer perceptron architecture with a generator (three hidden layers: 128, 64, 32 neurons, ReLU activation) and a discriminator (three hidden layers: 64, 32, 16 neurons, sigmoid activation) in Python’s TensorFlow. The generator took 100-dimensional random noise (z ~ N(0,1)) and produced synthetic vectors [color features, SOC], while the discriminator evaluated their authenticity. The GAN was trained for 10,000 epochs with a learning rate of 0.0002 and Adam optimizer, using a gradient penalty to stabilize training. The adversarial training preserved correlations by mimicking the joint distribution, and the noise input ensured unique samples.

KNN was used as an interpolation-based method for synthetic data generation. This approach involves selecting a set of real training samples and generating synthetic samples by averaging feature values of their nearest neighbors. The algorithm ensures that the generated synthetic samples remain within the natural range of observed values while enhancing data variability. Given a dataset with training samples X = {x1, x2, …, xn}, the synthetic sample xsyn is created as (Eq. 8):

where, K is the number of nearest neighbors, and xi are the K-nearest neighbors of a randomly selected sample. In this study, KNN generated synthetic samples by averaging the feature vectors of K = 5 nearest neighbors (selected via Euclidean distance) of a randomly chosen calibration sample. The calibration data were standardized, and each synthetic sample [color features, SOC] was created by averaging the entire vector of the K neighbors, preserving local correlations.

Bootstrapping resampled the calibration dataset with replacement to create new datasets (Eq. 9), with Gaussian noise (standard deviation = 5% of each feature’s standard deviation) added to enhance diversity. Given a training set X={x1,x2,…,xn}, the bootstrapped dataset X* is obtained by sampling from X with replacement:

Each synthetic sample included color features and SOC, preserving their original correlations. The resampling and noise ensured sufficient uniqueness while maintaining the data’s statistical structure.

For each method, synthetic datasets of 1000, 2000, 3000, 4000, and 5000 samples were generated and filtered to SOC ranges (3–4% to 3–14%). The filtered synthetic samples were concatenated with the 70% calibration dataset to form an augmented training set. The augmented features were standardized using StandardScaler, ensuring consistency with the validation set, which was standardized using the same scaler. An RF model (estimators = 100, random state = 42) was trained on the augmented dataset, and performance was evaluated on the validation set using R² and RMSE metrics. The entire workflow, including synthetic data generation, filtering, training, and evaluation, is illustrated in Fig. 9.

Data availability

The code for synthetic data generation, model training, and evaluation is available in a public GitHub repository: https://github.com/anshumanfs/research-paper-codes/blob/main/rachna-codes/enhancing-soc-estimation-with-generative-ai-and-nix-color-sensor.ipynb. The raw and processed datasets can be requested via the application link https://www.somsubhra.in/external-forms/data-access-request after January 2026. Requests will be reviewed, and data will be shared through secure channels upon approval.

References

Lal, R. Soil carbon sequestration impacts on global climate change and food security. Science 304 (5677), 1623–1627 (2004).

Smith, P. et al. Greenhouse gas mitigation in agriculture. Philosophical Trans. Royal Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 363 (1492), 789–813 (2008).

FAO. Status of the world’s soil resources (SWSR)- main report. (2015). http://www.fao.org/3/a-i5199e.pdf

Lal, R. Restoring soil quality to mitigate soil degradation. Sustainability 7 (5), 5875–5895 (2015).

Walkley, A. & Black, I. A. An examination of the Degtjareff method for determining soil organic matter and a proposed modification of the chromic acid Titration method. Soil. Sci. 37 (1), 29–38 (1934).

Nelson, D. W. & Sommers, L. E. Total carbon, organic carbon and organic matter. Methods soil. Analysis: Part. 3 Chem. Methods. 5, 961–1010 (1996).

Aitkenhead, M. J. et al. Predicting Scottish topsoil organic matter content from colour and environmental factors. Eur. J. Soil. Sci. 66 (1), 112–120 (2015).

Brown, D. J., Shepherd, K. D., Walsh, M. G., Mays, M. D. & Reinsch, T. G. Global soil characterization with VNIR diffuse reflectance spectroscopy. Geoderma 132, 273–290 (2006).

Stenberg, B., Rossel, V., Mouazen, R. A., Wetterlind, J. & A.M. & Visible and near infrared spectroscopy in soil science. Adv. Agron. 107, 163–215 (2010).

Vasques, G. M., Grunwald, S. & Harris, W. G. Spectroscopic models of soil organic carbon in Florida, USA. J. Environ. Qual. 39, 923–934 (2010).

Stiglitz, R., Mikhailova, E., Post, C., Schlautman, M. & Sharp, J. Using an inexpensive color sensor for rapid assessment of soil organic carbon. Geoderma 286, 98–103 (2017).

Stiglitz, R. Y. et al. Predicting soil organic carbon and total nitrogen at the farm scale using quantitative color sensor measurements. Agronomy. 8 (10), 212 (2018).

Mikhailova, E. A. et al. Predicting soil organic carbon and total nitrogen in the Russian Chernozem from depth and wireless color sensor measurements. Eurasian Soil. Sci. 50, 1414–1419 (2017).

Mukhopadhyay, S. & Chakraborty, S. Use of diffuse reflectance spectroscopy and Nix pro color sensor in combination for rapid prediction of soil organic carbon. Comput. Electron. Agric. 176, 105630 (2020).

Mukhopadhyay, S., Chakraborty, S., Bhadoria, P., Li, B. & Weindorf, D. C. Assessment of heavy metal and soil organic carbon by portable X-ray fluorescence spectrometry and NixPro™ sensor in landfill soils of India. Geoderma Reg. 20, e00249 (2020).

Swetha, R. K. & Chakraborty, S. Combination of soil texture with Nix color sensor can improve soil organic carbon prediction. Geoderma 382, 1–11 (2021).

Swetha, R. K. et al. Using Nix color sensor and Munsell soil color variables to classify contrasting soil types and predict soil organic carbon in Eastern India. Comput. Electron. Agric. 199, 107192 (2022).

de Faria, A. J. G. et al. Prediction of soil organic matter content by combining data from Nix Pro™ color sensor and portable X-ray fluorescence spectrometry in tropical soils. Geoderma Reg. 28, e00461 (2022).

Raeesi, M., Zolfaghari, A. A., Yazdani, M. R., Gorji, M. & Sabetizade, M. Prediction of soil organic matter using an inexpensive colour sensor in arid and semiarid areas of Iran. Soil. Res. 57 (3), 276–286 (2019).

Soil Survey Staff. Keys to soil taxonomy (12th Edition) (USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service. (2014).

Buol, S. W., Southard, R. J., Graham, R. C. & McDaniel, P. A. Soil Genesis and Classification (Wiley, 2011).

Simon, T. et al. Predicting the color of sandy soils from Wisconsin, US. Geoderma 361, 114039 (2020).

Van Huyssteen, C. W., Ellis, F. & Lambrechts, J. J. N. The relationship between subsoil colour and degree of wetness in a suite of soils in the Grabouw district, Western cape II. Predicting duration of water saturation and evaluation of colour definitions for colour-defined horizons. South. Afr. J. Plant. Soil. 14 (4), 154–157 (1997).

Sánchez-Marañón, M., Delgado, G., Melgosa, M., Hita, E. & Delgado, R. CIELAB color parameters and their relationship to soil characteristics in mediterranean soils. Eur. J. Soil. Sci. 55 (3), 551–565 (1997).

Viscarra Rossel, R. A., Minasny, B., Roudier, P. & McBratney, A. B. Colour space models for soil science. Geoderma 133 (3–4), 320–337 (2006a).

Padarian, J., Minasny, B. & McBratney, A. B. Using deep learning to predict soil properties from regional spectral data. Geoderma Reg. 16, e00198 (2019).

Kaya, F. et al. Assessing machine learning-based prediction under different agricultural practices for digital mapping of soil organic carbon and available phosphorus. Agriculture 12 (7), 1062 (2022).

De Caires, S. A., Keshavarzi, A., Bottega, E. L. & Kaya, F. Towards site-specific management of soil organic carbon: comparing support vector machine and ordinary kriging approaches based on pedo-geomorphometric factors. Comput. Electron. Agric. 216, 108545 (2024).

Goodfellow, I. et al. Generative adversarial Nets. Adv. Neural. Inf. Process. Syst. 27, 2672–2680 (2014).

Yue, Y., Li, Y., Yi, K. & Wu, Z. Synthetic data approach for classification and regression. In IEEE 29th International Conference on Application-specific Systems, Architectures and Processors (ASAP), IEEE, 1–8 (2018).

Lavanya, V. et al. Digital soil mapping of available phosphorus using a smartphone-integrated RGB imaging device and ascorbic acid extraction method. Smart Agricultural Technol. 9, 100591 (2024).

Jiang, C., Zhao, J., Ding, Y. & Li, G. Vis–NIR spectroscopy combined with GAN data augmentation for predicting soil nutrients in degraded alpine meadows on the Qinghai–Tibet plateau. Sensors 23 (7), 3686 (2023).

Bai, H., Zhou, X., Zhao, Y., Zhao, Y. & Han, Q. Soil CT image quality enhancement via an improved super-resolution reconstruction method based on GAN. Comput. Electron. Agric. 213, 108177 (2023).

Tibshirani, R. J. & Efron, B. An introduction to the bootstrap. Monogr. Stat. Appl. Probab. 57 (1), 1–436 (1993).

Bouillon, S. et al. Mangrove production and carbon sinks: a revision of global budget estimates. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 22 (2), GB2013 (2008).

Alongi, D. M. Carbon cycling and storage in Mangrove forests. Annual Rev. Mar. Sci. 6 (1), 195–219 (2014).

Kijowska-Strugała, M., Baran, A., Szara-Bąk, M., Wiejaczka, L. & Prokop, P. Soil quality under different agricultural land uses as evaluated by chemical, geochemical and ecological indicators in mountains with high rainfall (Darjeeling Himalayas, India). J. Soils Sediments. 22 (12), 3041–3058 (2022).

Ghosh, G. K. Red and lateritic soils and agri-productivity: issues and strategies. J. Indian Soc. Soil Sci. 67 (4), S104–S121 (2019).

Banerjee, B., Aggarwal, P. K., Pathak, H., Singh, A. K. & Chaudhary, A. Dynamics of organic carbon and microbial biomass in alluvial soil with tillage and amendments in rice-wheat systems. Environ. Monit. Assess. 119 (1), 173–189 (2006).

Chakraborty, S. et al. Use of portable X-ray fluorescence spectrometry for classifying soils from different land use land cover systems in India. Geoderma 338, 5–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2018.11.043 (2019).

Sugita, R. & Marumo, Y. Validity of color examination for forensic soil identification. Forensic Sci. Int. 83, 201–210 (1996).

Viscarra Rossel, R. A., Walvoort, D. J. J., McBratney, A. B., Janik, L. J. & Skjemstad, J. O. Visible, near infrared, mid infrared or combined diffuse reflectance spectroscopy for simultaneous assessment of various soil properties. Geoderma 131, 59–75 (2006b).

Schaefer, B. M. & Mcgarity, J. W. Genesis of red and dark brown soils on basaltic parent materials near Armidale, N.S.W., Australia. Geoderma 23 (1), 31–47 (1980).

Spielvogel, S. & Knicker, H. Kögel-Knabner, I. Soil organic matter composition and soil lightness. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 167 (5), 545–555 (2004).

Cardelli, V. et al. Non-saturated soil organic horizon characterization via advanced proximal sensors. Geoderma 288, 130–142 (2017).

Hermansen, C. et al. Visible–near–infrared spectroscopy can predict the clay/organic carbon and mineral fines/organic carbon ratios. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 80 (6), 1486–1495 (2016).

Chakraborty, S. et al. Rapid assessment of regional soil arsenic pollution risk via diffuse reflectance spectroscopy. Geoderma 289, 72–81 (2017).

Liu, B. & Mazumder, R. Randomization can reduce both bias and variance: A case study in random forests. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.12668 (2024).

Subramaniam, A., Wong, M. L., Borker, R. D., Nimmagadda, S. & Lele, S. K. Turbulence enrichment using physics-informed generative adversarial networks. arXiv preprint arXiv01907 (2020). (2020). (2003).

Schoeneberger, P. J., Wysocki, D. A. & Benham, E. C. Field Book for Describing and Sampling Soils (Government Printing Office, 2012).

Chakravarti, P. & Chakravarti, M. S. Soils of West Bengal. State Agricultural Res. Inst. Calcutta 23B (3-4), 93–101 (1957).

Dasgupta, S. et al. Influence of auxiliary soil variables to improve PXRF-based soil fertility evaluation in India. Geoderma Reg. 30, e00557. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geodrs.2022.e00557 (2022).

Carvalho, G. S. et al. Prediction of compost organic matter via color sensor. Waste Manage. 185, 55–63 (2024).

CIE. Colorimetry (3rd Edition). CIE Central Bureau, (2004).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010933404324 (2001).

Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 785–794 (2016).

Friedman, J. H. Greedy function approximation: a gradient boosting machine. Annals Statistics 29 (5), 1189–1232 (2001).

Reynolds, D. A. Gaussian mixture models. Encyclopedia Biometrics. 741, 659–663 (2009).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the IIT Kharagpur AI4ICPS I hub foundation funded AI4SOIL project and AI-Driven AgriSmart Solutions: Digital Soil Health Card (IIT Kharagpur) project for financial assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R. S., M. D., and S. C. conceived and designed the research. R. S. and S. D. collected and integrated the soil laboratory and Nix sensor datasets. R. S., A. N., A. D., S. D., A. B., D.C. W., R. B., and S. C. conducted the modeling, performed statistical analyses, and led the initial manuscript drafting. All authors contributed to result interpretation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Singh, R., De, M., Banerjee, R. et al. Enhancing soil organic carbon estimation with generative AI and Nix color sensor. Sci Rep 15, 40628 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24236-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24236-9