Abstract

The global landscape of migration has evolved significantly, with international migrants tripling since 1970, reaching approximately 281 million by 2020. This rise includes a notable surge in forcibly displaced individuals due to conflicts, wars, and human rights violations. Additionally, climate change is reshaping migration patterns by environmental degradation and extreme weather events, with projections indicating that 143 million individuals may be uprooted by climate catastrophes over the next three decades. In this context, migrants experience chronic stress due to the uncertainties of their journey, exposure to trauma, and changes in living conditions, possibly exacerbating health issues, including through impairment of the gut microbiome. Our study focuses on the characterization—by 16 S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing—of intestinal microbiome in 79 asylum seekers newly arrived in Italy from African countries through their comparison with publicly available datasets of worldwide populations encompassing different origin and lifestyle. This microbiological surveillance, conducted as cross-sectional sampling over one year, aimed to provides some glimpses on how the forced migration journey and the associated stressors affect refugees’ gut microbiome composition. Our findings suggest significant deviations in the gut microbiome composition of refugees compared to traditional rural populations, possibly driven by stressors such a psychological trauma and dietary changes. The loss of microbial diversity may increase susceptibility to health issues, highlighting the need for targeted public health strategies for refugee populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to the World Migration Report, the number of migrants has increased more than threefold since 19701,2. An average of 21.5 million people has been forcibly displaced each year since 2008 and, over the next 30 years, 143 million people are predicted to be uprooted, according to the 2022 U.N.’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report (https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/). In this scenario, it is crucial to assess the impact of migration events on the health and wellbeing of the people involved. Migrants frequently experience chronic stress due to the uncertainties of their journey, exposure to trauma, and changes in their living conditions3. Among others, migration fluxes might be associated with a relevant impact on the gut-associated microbiome, a key modulator of human health, due to complex and multifactorial causes. In particular, chronic exposure to migration-related stressors, psychological trauma, and changes in food supply and dietary habits have been hypothesized to disrupt gut microbiota balance, possibly exacerbating health issues in the short term1,4,5,6,7. These changes might compromise key gut health-promoting functions, for example, by reducing short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) production and/or increasing susceptibility to infectious diseases, also through a compromised barrier effect8. In the long run, it has been shown that changes in lifestyle, food supply, exposure to medications, access to health care services, and cultural and socio-economic conditions in immigrant populations lead to a progressive change in gut microbiome composition and function, with a consequent transition towards a more westernized configuration within the first year after migration9,10. However, studies of migrant populations worldwide remain limited, particularly for refugees.

Like Europe, and especially Mediterranean countries, Italy is currently facing a substantial refugee movement, particularly from several African countries with low socioeconomic levels in search of better work opportunities. Data indicate that, in 2024, Italy welcomed the highest number of sea arrivals in Southern Europe, with a total of 41,617 people arriving by sea (https://www.unhcr.org/europe/sites/europe/files/2024-10/bi-annual-fact-sheet-2024-09-italy.pdf). However, due to limited access to official health data, information on the health status of migrant populations arriving in Italy is still scarce11.

In this context, we aimed to provide insights into the gut microbiome structure of asylum seekers newly arrived in Italy from African countries through a one-year cross-sectional microbiological surveillance study conducted during 2022–2023. In particular, we investigated deviations in the gut microbiome composition of refugees compared to traditional rural populations, resulting in the loss of sensitive microbial taxa prevalent in non-industrialized populations that might increase susceptibility to health issues. Our study thus provides new insights into how the migration journey and related stressors affect refugees’ gut health, which could inform public health strategies for refugee populations.

Ethical statement

The present study was performed following the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki in 1975, revised in 2013 and all the procedures performed in this study meet the national and international guidelines. A written informed consent was obtained from every patient before the study and patients were completely anonymized by the researchers. Ethical approval was approved with the number 85-CE-2024 by Policlinico Foggia Ethical Committee. Included samples were obtained according to standard diagnostic and therapeutic protocols for the management of gastrointestinal infections. All the authors ensure that this study is HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, 1996) compliant. The researchers followed every mandatory (health and safety) procedure.

Materials and methods

Sample collection, processing and 16S rRNA gene amplification and sequencing

Seventy-nine individuals who arrived during the period April 2022-May 2023 and were temporarily admitted to asylum seeker centre Borgo Mezzanone, Foggia, Italy, were selected for the gut microbiome profiling using 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing.

Microbiological screening was offered free of charge to all consecutive newly arrived asylum seekers who arrived in Italy crossing the Mediterranean Sea within the previous 7 days. Stool samples were collected during routine health examinations and immediately sent to the Microbiology and Virology Unit of Foggia Policlinic, Foggia, Italy, to be processed as described below. According to internal procedures, each individual was interviewed with the support of mediators speaking the refugee’s native language in order to collect personal data (age and gender), when possible. While we aimed to sample the largest possible number of newly arrived refugees, no formal sample size calculation was performed. This decision was influenced by the significant cultural barriers and extreme difficulty encountered in obtaining fecal samples from this population. Consequently, we collected a single specimen from each participant.

Microbial DNA was extracted from faecal samples (approximately 200 mg) using the QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and then eluted in 200 μL of TE buffer. Extracted DNA was processed for 16S rRNA gene amplification and sequencing for prokaryotic community characterization. Library preparation was performed following the Illumina 16S Metagenomic Sequencing Library Preparation protocol (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). The V3–V4 hypervariable regions of the 16S rRNA gene were PCR-amplified in a 50μL final volume containing 25 ng of microbial DNA, 2X KAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMix (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) and 200 nmol/L of 341F (5’- CCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG-3′) and 785R (5′-GACTACHVGGGTATCTAATCC-3′) primers with Illumina adapter overhang sequences12. The PCR thermocycling protocol consisted of 3 min at 95 °C, 25 cycles of 30 s at 95 °C, 30 s at 55 °C and 30 s at 72 °C, and a final 5-min extension step at 72 °C13. PCR products were then purified with Agencourt AMPure XP magnetic beads (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA). Indexed libraries were prepared by limited-cycle PCR, using Nextera technology (Illumina), and cleaned up as described above. Libraries were quantified using the Qubit 3.0 fluorimeter (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA), normalized to 4 nM and pooled. The sample pool was denatured with 0.2 N NaOH and diluted to a final concentration of 4.5 pM with a 20% PhiX control. Sequencing was performed on an Illumina MiSeq platform using a 2 × 250 bp paired-end protocol, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Illumina).

Bioinformatics and statistical analysis

For 16S rRNA gene analysis, raw sequences from all individuals were processed using a pipeline combining PANDAseq14 and QIIME 215. High-quality reads were retained using the “fastq_filter” function of the USEARCH11 algorithm16 and clustered into amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) using DADA217. Taxonomy was assigned using the VSEARCH classifier18 and the SILVA database (2020, v138.1 release) as a reference19. All sequences assigned to eukaryotes or unassigned were discarded. Overall, a total of 637,063 high-quality reads (mean ± standard deviation: 8,382 ± 2,621) was obtained, resulting in a total of 3401 amplicon sequence variants (ASVs).

16S rRNA gene sequences of the gut microbiome associated with worldwide populations, characterized by different subsistence strategies (i.e., rural and urban, including a cohort of Italian individuals), were downloaded from publicly available datasets20,21,22,23,24,25. The 16S data from the samples analyzed in Rampelli et al.26 were produced in the context of the “HARVEST” project and published at PRJEB85423. Sequences were subjected to direct read mapping with Kraken2 (v2.1.2)27 and the resulting report was processed through the Bracken (v 2.6.2)28 pipeline with default option to obtain taxonomic tables at the genus level. Both Kraken2 and Bracken were used with SILVA database (2020, v138.1 release) as a reference19. Bracken outputs were then merged to obtain a single taxonomic table, which was subsequently merged with the genus-level taxonomic table of the original refugee dataset produced in this study.

All statistical analyses were performed using R software (R Core Team; www.r-project.org), v. 4.3.2, with the package “vegan” (https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan)29. Alpha diversity was calculated at the genus level using the function “diversity” of the vegan package, with the metrics “Shannon index”, “Simpson”, “Inverted Simpson” and “Observed genera”. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to assess significant differences in alpha diversity and genus-level relative abundance between groups. Beta diversity was estimated by computing Bray–Curtis distances at the genus level, and data separation in the Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) was tested using a permutation test with pseudo-F ratio (function “adonis” in the vegan package). P-values, when necessary, were corrected for multiple testing using the Benjamini–Hochberg method, with a false discovery rate (FDR) ≤ 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Linear discriminant analysis (LDA) Effect Size (LEfSe)30 was performed to identify discriminant bacterial genera. Only microbial taxa with LDA score threshold of ± 2 (on a log10 scale) and p-value ≤ 0.05 were retained.

Results

Gut microbiome profile of refugees in the global scenario

A total of 79 refugees (74 males and 5 females, mean age 26 ± 7 years) were profiled for the gut microbiome using 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing. A total of 637,063 sequences (mean ± standard deviation: 8,382 ± 2,621) and 3,401 ASVs were obtained.

The gut microbiome composition of refugees was compared with publicly available sequences from worldwide populations encompassing different subsistence strategies (rural and urban)20,21,22,23,24,25,26. Specifically, we selected 15 Nigerian individuals, of which three rural and 12 urban25, 18 rural Nzime, 26 rural Baka26 and 8 rural Pigmy individuals21 from Cameroon, 29 urban Canadian and 24 rural Inuit Canadian24, 24 rural Tunapuco and 20 rural Matses individuals from Peru22, 42 urban USA individuals from Norman and 38 urban Native Americans23, 27 rural Hadza from Tanzania and 16 urban Italians20. As expected, subsistence type was a major driver of the gut microbiome variation among the studied populations, as shown in the PCoA plot (permutation test with pseudo-F ratio, p-value ≤ 0.001) (Fig. 1a). Indeed, when considering the population distribution, we observed a significant segregation according to lifestyle, namely rural populations (150 subjetcs) and urbanized populations (137 subjects), and refugee status (79 subjects), regardless of geographical origin (p-value ≤ 0.001), with the centroid of the refugees’ group clustering closer to the rural group (Fig. 1b). Interestingly, the alpha diversity of the refugees’ gut microbiome was lower than that of rural populations (Wilcoxon rank-sum test corrected with FDR, p-values ≤ 0.05 for all metrics), but mostly comparable to that of urban populations (p-values ≤ 0.05 for Simpson, Inverted Simpson and Observed genera, but p-value ≥ 0.05 for Shannon metric) (Fig. 2).

Gut microbiome structure of different populations worldwide, including refugees. (a) A significant segregation was found in the Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) based on Bray–Curtis distances between the gut microbiome profiles of individual populations worldwide, including urban and rural populations whose sequences are publicly available17,18,19,20,21,22,23, and refugees from the present study (permutation test with pseudo-F ratio, p-value ≤ 0.001). C&A = Cheyenne and Arapaho. (b) Same populations as in panel “(a)”, grouped by subsistence type, namely rural populations, urban populations, and refugees. A significant segregation as found in the Bray–Curtis-based PCoA regardless of geographical origin (p-value ≤ 0.001). The first and second principal components (PCoA1 and PCoA2) are plotted and the percentage of variance in the dataset explained by each axis is shown. Color legend in the figure.

Gut microbiome diversity of refugees compared to urban and rural populations worldwide. Boxplots of alpha diversity calculated at the genus level using the metrics “Shannon”, “Simpson”, “Inverted Simpson” and “Observed genera” in the three groups (rural populations, urban populations, refugees). Significant p-values are indicated in the figure (p-values ≤ 0.001***, p-values ≤ 0.05*) (Wilcoxon rank-sum test corrected with FDR).

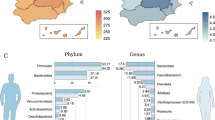

We identified significantly discriminant genera amongst the three groups taken into account (i.e. rural, urban, refugee) through LEfSe analysis (LDA score threshold of ± 2 and p-value ≤ 0.05) (Fig. 3). The urban group was mainly discriminated by Faecalibacterium, Blautia, Bifidobacterium, Bacteroides and Akkermansia (LDA score > 4); the rural group by Treponema, Bacillus, Ruminobacter, Butyrivibrio, and Roseburia (LDA score > 3); the refugee group by Prevotella, Escherichia-Shigella and Alloprevotella (LDA score > 4), but also Klebsiella (LDA score > 3). Interestingly, some compositional features of the refugee gut microbiome, particularly Prevotella and Alloprevotella, but also Succinivibrio, Streptococcus, and Ruminococcus, were shared with the gut microbiome of rural populations (Wilcoxon rank-sum test corrected with FDR, p-values > 0.05) (Supplementary Table 1).

Discriminant genera of the gut microbiome of refugees, rural and urban populations. Linear discriminant analysis (LDA) Effect Size (LEfSe) score of discriminating gut genera of the gut microbiome of the three groups (rural populations, urban populations, refugees). Only taxa with LDA score threshold of ± 2 and p-value ≤ 0.05 are shown.

Gut microbiome profile of refugees compared to the Italian cohort

Finally, we specifically compared the gut microbiome of refugees with that of the population of relocation, i.e. Italians. The Italian cohort comprised 16 urban living Italian adults from Bologna, Italy (5 males and 11 females, mean age 32 ± 5 years)20. The two groups significantly segregated in the PCoA plot (permutation test with pseudo-F ratio, p-value ≤ 0.001) (Fig. 4a) and differed in alpha diversity, which was lower in the refugees (Wilcoxon rank-sum test corrected with FDR, p-values ≤ 0.01 for all the metrics) (Fig. 4b).

Gut microbiome structure of refugees compared to the Italian cohort. (a) A significantly segregation was found in the Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) based on Bray–Curtis distances between the gut microbiome profiles of refugees and Italians17 (permutation test with pseudo-F ratio, p-value ≤ 0.001). The first and second principal components (PCoA1 and PCoA2) are plotted and the percentage of variance in the dataset explained by each axis is shown. Color legend in figure. (b) Boxplots of alpha diversity calculated at the genus level using the metrics “Shannon”, “Simpson”, “Inverted Simpson” and “Observed genera”. Significant p-values are indicated in the figure (p-values ≤ 0.001***, p-values ≤ 0.01**) (Wilcoxon rank-sum test corrected with FDR).

Confirming the previous findings, the refugee group exhibited a significantly higher relative abundance of Prevotella and Alloprevotella (LDA score > 3 and p-value ≤ 0.05) (Fig. 5). On the other hand, the Italian cohort was characterized by significant higher levels of Faecalibacterium, Bifidobacterium and Blautia as observed in the urban group above.

Discussion and conclusions

In the present study we provide insights into the potential impact of the challenging journey experienced by newly arrived African asylum seekers on their gut microbiome health, highlighting concerns about the risks to gut health in this vulnerable group. Through a one-year cross-sectional microbiological surveillance conducted from 2022 to 2023, we analyzed the gut microbiomes of 79 individuals using 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing and compared them to those of rural and urban populations worldwide and to the population of relocation (i.e. Italy). Our results showed refugees gut microbiome segregating distinctly from the one of rural and urban populations, and with refugees’ alpha diversity being significantly lower than that of rural populations, showing a peculiar configuration in opportunistic taxa increase. Given the known migration routes from Africa to Europe, which involve individuals from Sub-Saharan Africa (ISTAT https://www.istat.it/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/REPORT-CITTADINI-NON-COMUNITARI_Anno-2023.pdf; UNHCR https://data.unhcr.org/en/situations/europe-sea-arrivals/location/24521; ISPI https://www.ispionline.it/it/pubblicazione/africa-occidentale-le-migrazioni-infra-ed-extra-regionali-135619), where the majority of the population resides in rural areas (IPCC report 2022, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009325844), it is plausible to speculate that a significant portion of the analyzed refugee population may have originated from rural settings. In particular, the refugee gut microbiome retained taxa that are typically prevalent in non-industrialized populations and are diminished or absent in industrialized societies (i.e., VANISH taxa). These include Prevotella, Alloprevotella, Succinivibrio, Streptococcus, and Ruminococcus, which are often associated with high-fiber diets25,31,32,33. On the other hand, the refugee gut microbiome was depleted of other VANISH taxa typical of rural populations, such as Treponema, which aids in the breakdown of complex plant polysaccharides20, Ruminobacter, able to thrive on fibrous plant material1, and Butyrivibrio and Roseburia, known for the production of SCFAs, particularly butyrate, which is linked to beneficial anti-inflammatory effects34,35. This loss of VANISH taxa in the gut microbial composition of the refugee cohort compared to rural populations might be an early indicator of the very strong impact of migration-related stressors and potentially impact refugees’ health. Indeed, migration-related stressors have been shown to lead to dysbiosis, characterized by a decrease in alpha diversity and an increase in potentially harmful bacteria1. Supporting this, we also observed that the refugee group was discriminated by opportunistic pathogens, such as Escherichia-Shigella and Klebsiella, which could increase systematic inflammation and susceptibility to infections36,37,38,39,40.

In conclusion, our research revealed a significant deviation of the refugee gut microbiome from that of rural populations, with a loss of diversity of particularly sensitive VANISH taxa and an enrichment in pathobionts. Given that refugees were likely originating from rural areas, this alteration was possibly driven by stressors related to the migration journey, including chronic stress, psychological trauma, and shifts in food supply and dietary habits. These migration-related compositional changes could potentially increase the risk of dysbiosis, with an emergence of pathogenic taxa emergence, thus exacerbating the already precarious health conditions of asylum seekers individuals.

Data availability

High-quality reads from the present study were deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) under the project accession number PRJEB85422.

References

Parizadeh, M. & Arrieta, M. C. The global human gut microbiome: genes, lifestyles, and diet. Trends Mol. Med. 29(10), 789–801 (2023).

Upadhyay, R. K. Markers for global climate change and its impact on social, biological and ecological systems: A review. Am. J. Clim. Chang. 9(03), 159 (2020).

Ryan, D., Dooley, B. & Benson, C. Theoretical perspectives on post-migration adaptation and psychological well-being among refugees: Towards a resource-based model. J. Refug. Stud. 21(1), 1–18 (2008).

Fuzail, M. A. et al. Microbiome research potential for developing holistic approaches to improve refugee health. J. Glob. Health Rep. 5, e2021094 (2021).

Kang, J. et al. Diet quality mediates the relationship between chronic stress and inflammation in patients with metabolic syndrome. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 40, 10–1097 (2024).

Yi, B. et al. Influences of large sets of environmental exposures on immune responses in healthy adult men. Sci. Rep. 5(1), 13367 (2015).

Beurel, E. Stress in the microbiome-immune crosstalk. Gut microbes 16(1), 2327409 (2024).

Karl, J. P. et al. Effects of psychological, environmental and physical stressors on the gut microbiota. Front. Microbiol. 9, 372026 (2018).

Vangay, P. et al. US immigration westernizes the human gut microbiome. Cell 175(4), 962–972 (2018).

Shanahan, F., Ghosh, T. S. & O’Toole, P. W. Human microbiome variance is underestimated. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 73, 102288 (2023).

Sulekova, L. F. et al. Occurrence of intestinal parasites among asylum seekers in Italy: a cross-sectional study. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 27, 46–52 (2019).

Klindworth, A. et al. Evaluation of general 16S ribosomal RNA gene PCR primers for classical and next-generation sequencing-based diversity studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 41(1), e1–e1 (2013).

Turroni, S. et al. Fecal metabolome of the Hadza hunter-gatherers: a host-microbiome integrative view. Sci. Rep. 6(1), 32826 (2016).

Masella, A. P., Bartram, A. K., Truszkowski, J. M., Brown, D. G. & Neufeld, J. D. PANDAseq: Paired-end assembler for illumina sequences. BMC Bioinform. 13, 1–7 (2012).

Bolyen, E. et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 37(8), 852–857 (2019).

Edgar, R. C. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics 26(19), 2460–2461 (2010).

Callahan, B. J. et al. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 13(7), 581–583 (2016).

Rognes, T., Flouri, T., Nichols, B., Quince, C. & Mahé, F. VSEARCH: a versatile open source tool for metagenomics. PeerJ 4, e2584 (2016).

Quast, C. et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 41(D1), D590–D596 (2012).

Schnorr, S. L. et al. Gut microbiome of the Hadza hunter-gatherers. Nat. Commun. 5(1), 3654 (2014).

Morton, E. R. et al. Variation in rural African gut microbiota is strongly correlated with colonization by Entamoeba and subsistence. PLoS Genet. 11(11), e1005658 (2015).

Obregon-Tito, A. J. et al. Subsistence strategies in traditional societies distinguish gut microbiomes. Nat. Commun. 6(1), 6505 (2015).

Sankaranarayanan, K. et al. Gut microbiome diversity among Cheyenne and Arapaho individuals from western Oklahoma. Curr. Biol. 25(24), 3161–3169 (2015).

Girard, C., Tromas, N., Amyot, M. & Shapiro, B. J. Gut microbiome of the canadian arctic Inuit. Msphere 2(1), 10–1128 (2017).

Ayeni, F. A. et al. Infant and adult gut microbiome and metabolome in rural Bassa and urban settlers from Nigeria. Cell Rep. 23(10), 3056–3067 (2018).

Rampelli, S. et al. The gut microbiome of Baka forager-horticulturalists from Cameroon is optimized for wild plant foods. Iscience 27(3), 109211 (2024).

Wood, D. E., Lu, J. & Langmead, B. Improved metagenomic analysis with Kraken 2. Genome Biol. 20, 1–13 (2019).

Lu, J., Breitwieser, F. P., Thielen, P. & Salzberg, S. L. Bracken: Estimating species abundance in metagenomics data. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 3, e104 (2017).

Oksanen, J. Vegan: ecological diversity. R Project 368, 1–11 (2013).

Segata, N. et al. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 12, 1–18 (2011).

De Filippo, C. et al. Impact of diet in shaping gut microbiota revealed by a comparative study in children from Europe and rural Africa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 107(33), 14691–14696 (2010).

Sonnenburg, J. L. & Sonnenburg, E. D. Vulnerability of the industrialized microbiota. Science 366(6464), eaaw9255 (2019).

Carter, M. M. et al. Ultra-deep sequencing of Hadza hunter-gatherers recovers vanishing gut microbes. Cell 186(14), 3111–3124 (2023).

Cresci, G. A. & Bawden, E. Gut microbiome: what we do and don’t know. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 30(6), 734–746 (2015).

Dehingia, M. et al. Gut bacterial diversity of the tribes of India and comparison with the worldwide data. Sci. Rep. 5(1), 18563 (2015).

Hu, J. et al. Correlation between altered gut microbiota and elevated inflammation markers in patients with Crohn’s disease. Front. Immunol. 13, 947313 (2022).

Zhao, J. et al. Expansion of Escherichia-Shigella in gut is associated with the onset and response to immunosuppressive therapy of IgA nephropathy. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 33(12), 2276–2292 (2022).

Calderon-Gonzalez, R. et al. Modelling the gastrointestinal carriage of Klebsiella pneumoniae infections. MBio 14(1), e03121-e3122 (2023).

Singh, S. B., Carroll-Portillo, A. & Lin, H. C. Desulfovibrio in the gut: the enemy within?. Microorganisms 11(7), 1772 (2023).

Vornhagen, J., Rao, K. & Bachman, M. A. Gut community structure as a risk factor for infection in Klebsiella pneumoniae-colonized patients. Msystems 9(8), e00786-e824 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. We are very grateful to all the staff of the Microbiology and Virology Unit of Foggia Policlinic, Foggia, Italy, for their collaboration in collecting the samples.

Funding

The authors declare that no specific funding was used for this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: G.P and M.M. Investigation: M.M. Data curation: G.P. and S.R. Formal analysis: G.P. Methodology: G.P. and M.M. Resources: M.C. Writing, original draft: G.P. and M.M. Writing, review and editing: M.M., D.S., S.T., S.R. and M.C. Supervision: M.C.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Palladino, G., Marangi, M., Scicchitano, D. et al. Gut microbiome structure in asylum seekers newly arrived in Italy from Africa. Sci Rep 15, 40596 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24250-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24250-x