Abstract

The sustainability aspect must be implemented during all the phases of the decision-making phase regarding construction project execution to obtain the full advantages, shorn of conceding the project objective. Cloud computing (CC) has been an appreciated tool for successful and viable building processes in various nations over the past twenty years. CC and its drivers have certainly enhanced the successful and sustainable targets of quality, cost, and time. Conversely, CC adoption by the building industry in Egypt. Hence, the aim of this study is to build a decision support model to back drivers of CC adoption by analyzing the relationship concerning drivers of CC in building business in Egypt. The data was derived from various sources of the literature. A questionnaire survey for quantitative data generation followed this. The data was derived from 106 building practitioners in Egypt. Consequently, the study employed exploratory factor analysis (EFA) to authenticate the findings derived from the survey tool. The results categorized the drivers into three groups: Technology Drivers, Client Support Drivers, and Organization Drivers. Structural equation modeling using partial least squares (PLS-SEM) was then applied to test the relationships and rank their influence. Findings indicate that Technology is the most significant driver of CC adoption (β = 0.378, p < 0.001), followed closely by Client Support (β = 0.372, p < 0.001) and Organization (β = 0.360, p < 0.001). These findings can be used as a baseline or criteria for decision-making concerning improvements in the cost-effectiveness of CC and its proficiency to increase efficacy in the building sector. Therefore, this study adds to the understanding of contemporary construction management and engineering by extending the existing literature on CC adoption derivers and their effects on the building industry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The building industry is pivotal for the growth of developing nations and is reinventing itself by applying innovative techniques and government-supported digital technologies (such as e-governance systems, online permitting, and regulatory IT tools1. The building sector has experienced considerable modifications to meet local and international demands2. In the ever-changing and urbanising world, the apportionment of building projects cannot sufficiently meet the increasing demand3. Additionally, building schemes face frequent delays in their schedule4,5,6. The sector faces various productivity problems resulting from the dearth of implementation of new technologies7,8,9,10.

Moreover, consistent data is essential for implementing all building tasks and enhancing the success of construction activities, as fragmented data hinders progress11. In several developing countries, the building sector does not receive sufficient backing from clients, society, or governmental bodies12. Building projects is a fundamental aspect of community development that reflects the quality of life and overall well-being of a country’s residents13. Building project account for approximately 40% of global energy consumption and contribute nearly one-third of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in both developed and emerging nations14. Nevertheless, in a rapidly urbanizing and constantly evolving world, residential housing supply is unable to adequately meet demand3. Consequently, rapid urbanization is restricting access to affordable housing for low-income earners in both developing and developed countries15. These regions have experienced rapid development, underscoring the crucial role of residential buildings in supporting basic living conditions12. As a result, governments worldwide have prioritized affordable building by introducing a range of supportive building policies."13. Nevertheless, debate persists over the affordability of residential buildings for low-income earners3. Given the challenges of low wages, high unemployment, and sustainability threats, Egypt is regarded as a high-risk market16. This risk is influenced by sharp currency fluctuations, limited knowledge in business decision-making, and restrictions on investment models17. Since 1950, the country has experienced rapid population growth and is now the most populous nation in North Africa18. The risk is driven by significant currency volatility, insufficiently informed business judgment, and constraints on investment models17. Broadly speaking, project delays in Egypt stem from construction finance challenges, unreliable client payments, sudden design alterations, and ineffective building management19. Consequently, the lack of sufficient and appropriate residential projects remains a key challenge for Egyptian policymakers20. Consequntly there is a need for constructing “sustainable buildings” that are environmentally friendly and resource-efficient has been highlighted in the literature21. Wolstenholme, et al.22 further advocate revolutionizing the building field through adopting effective and sustainable building practices. Furthermore, building professionals cannot measure the environmental influences of buildings as they accrue through construction23.

Given these observations, cloud computing (CC) plays a crucial role.Many emerging economies consider cloud computing (CC) to enhance their budgetary process24. This technical approach, cloud computing (CC), needs to be established to implement the concept of performance growth25.CC is concurrent with high-tech advancements, and texts on these tools and their applications is broadly obtainable. Therefore, it might be effectively applied in the design and implementation of the project’s phases26, and it is contended that effective construction practices require modern technologies to be applied to computerise the building activities, resulting in construction activities’ success. Thus, improving the success practices and trisecting the progress of building projects is pertinent. CC can assist in realising the objective of future project accomplishment by offering distant access to processing funds via the Internet using ICT devices and methods globally11. CC is geared toward transforming viable building activities globally into an adaptable method for sustainable budget management through its integral pay-as-go network, scalability, availability and other features27.

The cost-effectiveness will measure the performance of building projects28. The computing system is provided through distributed server systems that assist managers simultaneously29. CC tools can yield high-performing computational supremacy by scrutinising huge volumes of IoT data and offering a priceless vision for policymaking30. CC is a novel approach that allows SMEs to address different sustainability issues, including risk and financial management issues31. It uses facilities as an outcome, reimbursing only for what is essential11. Though the existing texts has highlighted the benefits of CC, little effort has been made to evaluate the CC implementation drivers in third-world nations; its implementation is still insignificant32,33. Many companies still lack adequate knowledge on how CC can influence or enhance their activities34.

Moreover, Fang, et al.35 contended that there are just minute CC applications in the building sector. Additionally, limited literature on specific IT, including CC, provides benefits that improve communication abilities across companies and increase economic effectiveness36. Similarly, Zainon, et al.37 argued that the evolution of CC and its impact on the construction sector requires implementation to tackle construction challenges, and CC can aid in this aspect. Therefore, the key factors influencing CC implementation should be assessed38. This empirical study highlighted the fundamental study enquiry based on the results acquired. Thus, the problem is, what are the most essential drivers required for CC implementation in Egypt’s building sector? Hence, there is a need to explore and examine these drivers39.

Rockart40 classifies the drivers as 'areas where, if satisfactory, then the outcomes will guarantee the company’s economic achievement. Chan, et al.41 and Yu, et al.42 opined that the drivers must be considered as critical organization promptness and accomplishment in various building activities to produce enhancements43. By considering these drivers, a company can influence success positively the success of the development process and, at the same time, mitigate its risks44. This research aimed to ascertain the drivers affecting CC implementation in Egypt’s building industry. Hence, this study attempts to present a new effort to narrow the exiting via a partial least squares (PLS) modelling technique to statistically assess and explore CC implementation drivers.

Further, this research employed the global local context (GLC) method, which highlighted the significance of this research. In addition, it magnifies and signifies the issues assessed. According to Summers45, one-way of marketing a research’s significance is to establish its relevance in general and local contexts. Therefore, the context of ‘developing countries’ and Egypt in particular as a local context for this study is designed to achieve lucidity (i.e., creating the importance). Additionally, this study will assist policymakers in achieving a successful building project by improving efficiency and lessening the costs of CC adoption in developing nations, particularly Egypt, where comparable construction schemes are performed46. Finally, this study is anticipated to assist in providing numerous advantages to different construction specialists, comprising designers, project bidders, and lawmakers47.

The article is structured into several distinct sections to thoroughly investigate the adoption drivers of cloud computing in sustainable building projects within developing countries. The paper progresses through sections on Background to the Research, Methods, Results, Discussion, and finally, Conclusion and Implications. Each section builds logically on the previous one, starting with a detailed look at cloud computing concepts and their relevance to the construction industry. The Methods section outlines the research design and analytical techniques used, followed by the Results, where the study findings are presented. The discussion delves into the implications of these findings, interpreting their significance for industry practices. The paper concludes by summarizing the key contributions and suggesting areas for future research, presenting a well-rounded exploration of how cloud computing can improve sustainable building initiatives in developing countries.

Background to the research

The concept of cloud computing (CC) denotes internet-based tools that store data in servers and deliver software as a service (SaaS) to clients on request38, which has significance for companies and customers48. Therefore, customers could access information from any means, though companies could lease computing resources (such as hardware and software) and storage space from providers of cloud services49. Thus, it is theorized that a valuable approach for firms is to reduce IT, use a smaller space apportioned for energy use, increase delivery efficacy, provide added value, assist in generating employment and lessen the risk related to managing and maintaining the hardware arrangement50,51. Based on the NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology)'s description, CC is a standard that facilitates convenient, omnipresent, on-demand linkage connected to a common network of configurable processing means (e.g., storage, servers, networks, services, and uses) that can be released quickly after provisioning with insignificant organization input or service supplier interchange52.

Subsequently its commencement in 2006, it has evolved as one of the foremost tools that are investigated for utilization by firms globally53. Providers of CC offer the entire IT facilities on request, though payment is made for equipment and processOr amenities54. CC is categorized into three service models: software as a service (SaaS), program as a service (PaaS), and infrastructure as a service (IaaS). The providers of CC give customers on-customers with simple mathematical skills in IaaS38. In contrast to regular hosting services, IaaS offers the capacity to meet the different requirements of many clients48. Cloud computing can be achieved by offering remote access to computing resources over the internet through global information and communication technology systems55,56,57. Furthermore, cloud computing enables remote collaboration, allowing for the creation and real-time storage of development data across cloud networks58,59.

Consequently, it presents considerable flexibility and cost reduction equated to traditional processing tools60. CC suppliers promote their products (i.e., software applications) via the Internet under SaaS48. However, in other conventional IT resolutions, software program installations are needed48. In contrast, inter-service providers control their facilities60; PaaS services offer designers elucidations that are more advanced and explicit compared to traditional computer unit settings48, allowing autonomous software providers and IR experts to develop and establish web applications speedily by means of third-party set-up38. PaaS is an all-inclusive podium for scheming, developing, analyzing and installing a service48. The consumers of PaaS can develop applications using provisioner-aided APIs and software design languages and install the applications instantly onto the cloud server providers61. It comprises Drop and Zoho Box, Google (Drive and Mail), iCloud, Yahoo, Office Live, IBM, and Adobe Creative Cloud as a tool service and platform31,61,62,63,64,65.

Different types of applications comprising genomic data treating, learning and teaching, service areas for medium- and small-sized enterprises, e-learning techniques, manufacturing, amplified actuality, smart cities, emergency recovery, and other fields, including hospitality, forensics, e-government, and administration of human resources and the Internet of Cars, employ CC services66. In recent times, CC has experienced a sudden rise in acceptance all over the world67. Once these potentials are utilized to their maximum potential, they can enhance construction processes in various ways and are central to one another68. Academicians are currently studying how collaboration in cloud services is applicable to developing and integrating data that will produce added value to the latent forte of CC services and systems48.

Object information is storable and read from different podiums through visualization procedures. Therefore, the weight of data processing can be lessened, and the data can be analyzed on the cloud69. Based on this similarity, the presentation stratum can sense equipment in the immediate location and simultaneously submit queries to the sensor and the cloud to the sensor and analyze the data48. Object data is then reposted through data derived from the sensor stratum. Hence, data analysis is scheduled for subsequent activities70.

Consequently, CC allows business organization to concentrate on their fundamental markets, progressions, and produce modernization. The firm’s IT unit can subsequently finance the creative projects with the time, budget, and exertion that could be expended on the IT unit. Therefore, it allows companies to better utilize their valuable and scarce incomes to improve their products and skills31. Cloud computing facilitates this by offering remote access to computing services through information and communication technology systems71,72. Cloud computing (CC) is grouped into three sets: society, private, and mixed clouds59. Clouds are developed inside the firm firewall, so they are inside and can be retrieved by different departments or units73. In the public setting, the cloud is created and formed outside the firm’s firewall74. Lastly, a hybrid cloud is a cloud that unites private and society cloud structures. Many nations mount mixed clouds to obtain the benefits of the society, though still profiting from private cloud data safety74.

The significant structures of the tools comprise on-request self-service, dynamic resources, extensive system entrée, measurable service, and swift tractability or progression52. In 2006, when the phase of CC was initially introduced, it enjoyed a huge investment of about 266.4 billion dollars with a regular annual increase of 17%, with an estimated 60% of all firms anticipated to utilize a subcontracted cloud service provider to mount the network75. Europe and the USA, the effect of cloud implementation has been extensively studied as an essential set-up that allows governments to share, store, and analyze data to improve the available services or establish novel tools and offer new services76,77.

Therefore, it is clear that the adoption of CC has many benefits. However, cloud organizations generally encounter hurdles. For example, in Europe, 'legislation, culture, environment, politics and economy, sense of certainty, scarcity of IT personnel, lack of patient and anxiety’ are considered major barriers78. This research is driven by the need to assess emerging economies such as Egypt to improve understanding of the overall influence of CC. The research was based on the hypothesis that the surroundings play a central role in accepting cloud technology, with nations in the first-world region being at a greater point than the third-world nations79.

Although Europe and the USA have undergone higher levels of implementing CC, various nations in Asia and Africa are in the initial phase of CC adoption79. For instance, Singapore, South Korea, and Japan are moving community amenities into the cloud75 and financing the development of a national cloud structure80. The rise in cloud adoption in private and public sectors shows its wider implementation in these countries48. For example, it has a high-tech cloud structure; South Korea enfolds cloud amenities as an important aspect of the country’s Industry 4.0 plan, though Singapore offers accessible cloud services. However, Egypt has yet to explore cloud technologies fully75. Thus, it can be more thought-provoking to meet community anticipations concerning aptness, easy access to public services, quality, and innovation81,82.

Adopting cloud computing (CC) overpowers this difficulty by lessening the time spent retrieving social amenities, lessening logistical charges, and enhancing service excellence via CC services83. Likewise, it allows timely access to public services from any location through mobile devices. Based on the available literature, CC users consider it an innovation in implementing novel tools and modernization84. Likewise, it can lead to adopting other advanced technologies, including digital renovation in some areas71, as an integrative technology solution85. Additionally, some nations, particularly in Asia, are increasingly implementing cloud tools86 due to the continent’s increasing demand for services to its population87.

Different organizations gradually shift to CC because it provides scalable and dynamic resources via online services88. Thus, CC application in the construction business has experienced considerable innovation for thirty years, as indicated in Table 1. Nevertheless, research on CC’s adoption and application by construction stakeholders is hard, especially in third-world countries11. While earlier research has highlighted the advantages of cloud computing, there has been insufficient focus on how cloud computing is implemented in the construction sector of developing countries11. Consequently, the current study attempts to narrow this gap by searching and assessing the CC drivers and building activities to realize optimal delivery of projects.

Methods

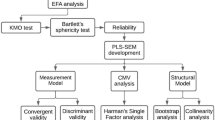

The objective of this research is to increase the Egyptian building business’s effective provision of construction projects by identifying the cloud computing (CC) implementation drivers. Figure 1 outlines the study design. Following a literature review to identify candidate CC implementation drivers, we developed a structured questionnaire to measure these drivers (15 items; five-point Likert scale; see Table 1). The questionnaire captured respondents’ perceptions of the drivers and basic organizational characteristics. We then conducted exploratory factor analysis (PCA with varimax rotation) to validate the construct structure and used partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) to estimate the relationships among the latent constructs and the overall CC implementation drivers

Analysis of construct validity

To categorize the constructs associated with drivers of CC implementation (Table 1), the preceding literature was examined analytically to identify the significant drivers through exploratory factor analysis (EFA) to measure the cogency of the construct by measuring the validity, reliability, and non-dimensionality of each component of the measured constructs (i.e., the analytical models). It is noteworthy that Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was selected compared to some statistical techniques due to its reliability and less complexity conceptually96. An orthogonal varimax rotation was applied to obtain a simpler and more interpretable factor structure by maximizing the variance of squared loadings across factors (i.e., encouraging each item to load highly on one factor and weakly on others). Varimax does not increase factor loadings; rather, it assumes factors are uncorrelated. Inter-factor relationships are modeled explicitly in the subsequent PLS-SEM stage. Oblique rotations such as Promax or Direct Oblimin allow for factor correlations, but varimax was chosen here to maintain orthogonality and simplicity of interpretation97.

Structural equation modelling (analytical approach)

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was carried out to explore and evaluate the drivers of cloud computing (CC)98,99,100,156. This technique was selected since it produces relationships among variables (i.e., observable and non-observable). Therefore, SEM suits the current analysis101,102. This paper employed the PLS-SEM method to create the model and evaluate the CC implementation drivers. This approach has turned out to be a confirmed approach with intricate hypothesis testing approaches103,104,105. It has been argued that PLS-SEM is a popular analysis approach and the most extensively used for analyzing humanities. This method has a broader statistical application that can be applied to evaluate the structural and measurement prototypes106,107. Thus, this technique was applied in this paper since it can be applied to evaluate the data derived from the building engineering participants108,109. Besides, it is a forecast-based assessment technique that can deal with data intricacy110,111,112.

Questionnaire development

The questionnaire was designed to capture both background information and perceptions of cloud computing (CC) adoption drivers. It comprised three parts: the first collected demographic and organizational details of respondents; the second measured the identified CC drivers (summarized in Table 1) using a five-point Likert scale ranging from very low (1) to very high (5), a format widely adopted in prior research109,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120 and the third included an open-ended question, allowing participants to suggest additional drivers they considered relevant but not listed. This structure ensured both standardized measurement and flexibility to capture context-specific insights.

Data collection

This research concentrates on applying cloud computing (CC) adoption drivers to implement building schemes in Egypt efficiently. The data was randomly collected from the study population. The determination of sample size was guided by the population of the study121. Therefore, an appropriate statistical tool was selected to generate the anticipated model based on the size of the sample. Accordingly, SEM was chosen since the size of the sample was deemed adequate to realize the needed goal and offer a different model109. Considering SEM, Yin122 concurred that the size of the sample was above 100; it is deemed appropriate for analysis.

In contrast, many other scientists have opposed the maximization and suggest enhancing the size of the sample123. They contended that it is not time-efficient and economical, though a bigger sample size can be advantageous concerning generalization. The minimum sampling size measured was chosen to attain the needed numerical significance level124,125. The SEM needs an appropriate sampling size to obtain reliable measurements126. Gorsuch127 recommended a minimum of five respondents for every variable (or construct) and 100 respondents for data analysis.

Similarly, the PLS-SEM exploration used in this paper was selected over covariance-based SEM (CB-SEM) since it best fits the study’s structure. PLS-SEM can be applied to avoid astringent hypotheses that form an overall approximation of the overall potential deductions with a minimum sampling size128,129,130,131,132. The sampling size for performing PLS requires between 30-100 participants130,133. A total of 138 questionnaires were distributed, of which 106 valid responses were received and used for analysis (76% response rate)97. The sample obtained met the recommended threshold, which concurred with the required minimum sample size122,127,130,131,133,134. Moreover, the size of the sample used is comparable to that employed in studies using PLS-SEM in construction schemes.

Also, sample-size planning was conducted with GPower (F tests → Linear multiple regression: fixed model, R2 deviation from zero). Assuming a medium effect (f2 = 0.15), α = .05, power (1–β) = .80, and three predictors (Technology, Client Support, Organization) pointing to the endogenous construct, the required minimum sample was N = 77. Our realized sample (N = 106) exceeds this threshold. In addition, the PLS-SEM “10-times rule” (10 × the maximum number of structural paths directed at any endogenous construct) suggests a minimum of 30 cases (3 paths × 10), which is also satisfied. These criteria complement prior guidance on minimum sample sizes for PLS-SEM in construction and management research. It recommends that the collected data is adequate for empirical testing concerning future research135.

Results

Construct model classification

The sampling adequacy was measured using Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO), as summarized in Table 2, indicating an acceptable factor analysis (FA). The KMO = 0.818 revealed that 81.8% of the data acquired was suitable for factor analysis (Table 2). The findings also show that the p-value considered was below 0.05, suggesting that it is suitable for exploratory factor analysis (EFA) with a degree of freedom rate of 105 and an evaluated chi-square of 954.787 for the data employed in this analysis. Conversely, Bartlett’s test was used, and a significant p-value of 0.000 was obtained, suggesting that the correlation is an identity matrix. Likewise, it suggested that the correlation matrix of the variables above (or constructs) has a strong correlation at the 5% level, highlighting the aptness of the EFA application.

Additionally, as indicated by Table 3, the principal component analysis (PCA) showed that the presence of three variables having an eigenvalue >1 explained 25.3%, 24.2%, and 26.33% of the observed variance in the CC application in the building industry. However, the second variable on the screen plot shows a break. The number of components analysis must produce is designated by the curve slope leveling off, as indicated in Fig. 2 and Table 4. The results of factor analysis produced only three abridged components. The finding also showed a Varimax rotation, suggesting the apparent effects of each construct (or variable) on a specific factor, with factor scores exceeding 0.40. Current results concurred with Oke et al.137, who suggested that it is more appropriate to concentrate on factor loadings that surpass the threshold of 0.40 for meaningful interpretation.

The assignment of names to the extracted components (3) is critically important before conducting a thorough interpretation. Current literature offers minimal or no established guidelines for naming components derived from factor analysis. Implicit in this statement is the recognition that the naming process is subjective and shaped by the individual’s perception, background, and level of training/education. Following careful deliberation on the appropriate approach for naming, the following names emerged: Technology Drivers, Client Support Drivers, and Organization Drivers.

Dimension model

For each latent construct, the indicators must agree with each variable141. Generally, external loading indicators of 0.40-7.0 must be considered for deletion if the removal greatly enhances the AVE and composite reliability123. The external loadings for all the variables original dimension models are illustrated in Fig. 3. Thus, all the external loadings were captured. Hair Jr, et al.142 suggested assessing the composite reliability interconsistency via Cronbach alpha limits, which is the thoughtfulness to the number of variables analyzed as suggested. Hair Jr., et al.142 suggest values >0.7 for any study and >0.60 for investigative study143. As indicated in Table 5, all the models met the Cronbach alpha value of 0.70 limits and were acceptable. As specified by143, AVE is a typical procedure for evaluating the convergent cogency of models’ variables with values >0.50, suggesting an adequate convergent validity value. Additionally, Table 5 indicates that each construct passed this measurement. It implies that the analytical constructs engross at least half of the dimension difference144,145.

Discriminant validity (DV) is well explained if the variable differs significantly from the other variables based on the defined standard. Therefore, the variables’ origin DV becomes distinctive and explains why other structures within the model cannot be ascertained133,136. According to the Fornell–Larcker criterion, discriminant validity is established when the square root of the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) for each construct is greater than its correlations with other constructs137. This criterion ensures that each construct shares a stronger relationship with its own indicators than with those of any other construct, thereby demonstrating both internal consistency and conceptual distinctiveness138.

As presented in Table 6, all diagonal values (representing the square roots of AVEs) are higher than the corresponding inter-construct correlations, confirming that discriminant validity has been achieved among the constructs. For instance, the square root of AVE for Client Support Drivers (0.820) exceeds its correlations with Organisation Drivers (0.793) and Technology Drivers (0.770). Similarly, Organisation Drivers (0.780) and Technology Drivers (0.850) each have diagonal values greater than their respective correlations (0.793 and 0.658). Overall, these results indicate that each construct shares more variance with its own indicators than with other constructs in the model, confirming that all three constructs are conceptually independent and exhibit satisfactory discriminant validity based on the Fornell–Larcker criterion.

Structural model

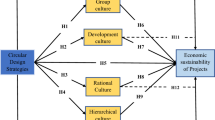

Path analysis is a linear regression method widely applied to examine all dynamic correlations simultaneously139. SEM emphasizes on the general model fit, with presumed path, scale, and important parameter evaluations140. The value between every path indicates the path coefficient, which assesses a variable’s impact level or construct on another variable141. Lastly, the correlation analysis was verified on the tested hypothesis in Fig. 4142.

PLS-SEM assessed CC drivers and their impact on building activities, as illustrated in Fig. 4, based on the postulated model of this study. The implication of the hypothesis in the bootstrapping method was assessed, centered on the model. The main data set derived from random resampling comprises the bootstrapping procedure to yield a novel sample size as the initial data set. The method examines the statistical reliability and validity. Thus, the path error of the path coefficient was determined142. Therefore, the bootstrapping technique is needed as an essential component of the first-order dependent variables, and it was measured.

Consequently, the bootstrap technique is requisite as a major part of all first-order dormant variables, and it was measured. As a result, this study assessed the collinearity of the concept’s dependent variables by assessing the value variable inflation factor (VIF). While dealing with dependent-weighty second-order variables in the assessments, this study applied values of internal VIF to assess the collinearity. The values of VIF for these figures were below 3.5, indicating that these subdomains donate to higher-order variables independently (Table 7). A strong standard path was defined β (external load) for the three first-order constructs (or variables) for drivers of cloud computing, as indicated by Fig. 4. Figure 4 provides a visualization of a structural equation model (SEM) that analyzes the factors driving cloud computing implementation within an organization. It identifies three key latent variables: Technology, Client Support, and Organization, each represented by large blue circles. These variables are defined by various observed indicators, labeled D1 through D15, which likely measure specific aspects pertinent to each category.

In terms of relationships, each latent variable contributes positively to a central construct labeled "Cloud Computing Implementation Drivers," with path coefficients indicating the strength of these relationships. The coefficients are as follows: Technology at 0.378, Client Support at 0.372, and Organization at 0.360, all with p-values of 0.000 (Table 7). These values suggest statistically significant positive influences, indicating that advancements in technology, effective client support, and organizational structure are all crucial and approximately equally influential in driving cloud computing implementation. The coefficient for Technology (0.378) suggests a moderately strong influence on the implementation drivers of cloud computing. This could imply that technological factors such as infrastructure, software, and hardware capabilities within the organization are crucial enablers of cloud adoption. The practical aspect might involve investments in the latest technology or upgrades that support cloud-based operations. Also, the Client Support (0.372) coefficient highlights the importance of customer-oriented processes and support systems in driving cloud implementation. This could involve training customer support teams, developing technical support protocols, and establishing robust helpdesk services specifically tailored to support cloud-based solutions. Finally, the coefficient for organization (0.360) (Table 7) indicates that organizational structures, culture, and policies play a significant role in the adoption of cloud computing. Elements such as leadership support, strategic alignment, and the willingness of staff to embrace new technologies could be critical factors under this variable.The p-values of 0.000 reinforce the statistical significance of these findings, asserting a high level of confidence in the model’s predictions. This analysis helps in understanding how different organizational aspects collectively enhance the adoption and effective implementation of cloud computing technologies.

Discussion

Numerous daily and industrial actions in human settlements depend on strong enclosed setting amenities. Clients’ concern in concurrent internet-based amenities has increased in modern times, as has the courtesy of suitable, speedy, and cost-efficient service distribution143. Cloud Computing (CC) is among those services144. The introduction of CC connotes a significant shift in the pattern in which information technology (IT) amenities are perceived, established, executed, upgraded, mounted, controlled, and funded74. The CC implementation has significantly impacted the IT business and drawn much consideration from IS researchers144. Numerous industries have established cloud centers to offer various amenities (including infrastructure as a service) to industries and partners for supply chains on a metered foundation145.

Similarly, the high-tech revolution has made CC-based sharing the foremost technique for delivering numerical content (including mail, documents, images, videos, gaming and music146). In managing information and communication, control of construction schemes, management of building projects, operational performance of companies, and informed decisions are central. Thus, CC implementation is essential in the building business147.

Our results show that Technology Drivers exert the strongest influence on CC adoption, closely followed by Client Support Drivers and Organisational Drivers (β = 0.378; β = 0.372; β = 0.360; all p < 0.001; see Fig. 4). The narrow spread of coefficients indicates that successful adoption depends on a balanced portfolio of technology readiness, client enablement, and organisational capacity—not technology alone. This pattern aligns with the EFA evidence. Principal component analysis identified three components with eigenvalues > 1 (λ₁ = 7.363; λ₂ = 1.346; λ₃ = 1.173), cumulatively explaining 65.881% of variance (see Table 3). Within this structure, Technology Drivers showed strong factor loadings across items D2, D4, D5, D8, D9, and D15 (see Table 4). To avoid ambiguity, we refer to EFA factor loadings (Table 4) and PLS-SEM outer loadings (see Fig. 3) separately. The measurement model met reliability and convergent-validity thresholds (Cronbach’s α ≥ 0.70; composite reliability ≥ 0.70; AVE ≥ 0.50; see Table 5). Consistent with evidence from Nigeria Oke, et al.55, where PLS-SEM results ranked Platform-tools as the principal enabler of cloud adoption in construction, our Egyptian model identifies Technology as the dominant driver of adoption. However, a salient difference is that Client Support in Egypt is nearly as influential as Technology, underscoring the role of payment security, investment willingness, and client–contractor coordination in converting technical capacity into actual uptake. This alignment-with-difference suggests a unified policy logic for developing-country markets: prioritize scalable platforms and interoperability while simultaneously instituting client-oriented mechanisms (e.g., e-payment standards, contractual CC clauses, and transparency requirements) to realize the full benefits of cloud adoption for sustainable construction.

The three aspects developed by the proposed model are illustrated in the following sections.

Technology drivers

The significance of technology in construction schemes is indisputable. Thus, as established in the literature, technology is unquestionably critical in CC implementation by construction businesses. Established on the PLS-SEM model, the technology aspect has the most significant influence on the drivers of CC implementation, with an outer loading of 0.78 on the ‘technology’ aspect, indicating the strongest influence. Technology boasts uniformly high loadings ranging from 0.738 to 0.821 across indicators D2, D4, D5, D8, D9, and D15. These high values underscore the critical role of technological readiness in cloud computing implementation. Indicators in this category likely cover aspects such as infrastructure robustness, software and hardware adequacy, and technological innovation. The strength and consistency of these loadings suggest that maintaining cutting-edge technological resources is paramount for effective cloud adoption and integration.

Similarly, Gangwar, et al.61 argued that availability and performance drive CC implementation. Furthermore, Gaurangkumar and Minubhai148 posited that there is a mounting requisite to offer solutions that can encourage happiness and trust between operators to implement CC in the projects quickly. Oliveira, et al.90highlight that the cloud computing model facilitates access to all aspects of software development, encompassing design, testing, version control, maintenance, and hosting, all through the internet. Additionally, with Software as a Service (SaaS), users can utilize centrally hosted applications in the cloud via various platforms, such as web browsers or mobile applications, instead of relying on local installations. Kumar et al157. assert that cloud computing can be utilized in multiple capacities within the construction sector, including modeling, structural analysis, cost estimation, planning and monitoring, and procurement processes. Afolabi64indicates that numerous stakeholders in the construction industry utilize services like Gmail or Yahoo Mail to access cloud resources. The significant advantage of cloud computing lies in the rapid data-sharing capabilities among professionals and other participants in the construction field. Moreover, Muhammad Abedi149contends that the adoption of cloud computing will enhance collaboration and coordination among partners, thereby improving operational efficiency within the construction industry. The integration of cloud computing fosters greater flexibility in formulating effective strategies related to revenue generation, efficiency, and overall effectiveness. An enterprise obtains full control over its cloud-stored data throughout its entire life cycle once the data and workloads are securely preserved and analyzed on the platform150. A cross-country lens underscores the importance of contextualizing CC adoption. In Nigeria, for instance, Oke, et al.151 found that adoption was primarily structured around Platform, Communication, Software, and Data Storage tools, with platform-based tools (e.g., Microsoft Azure, Amazon) being the strongest enablers. In contrast, our Egyptian study shows that drivers, rather than tools, dominate adoption priorities. This difference reflects Egypt’s systemic barriers—payment delays, limited client confidence, and organizational inefficiencies—which elevate non-technological drivers such as client trust and organizational readiness. Thus, while Nigerian adoption is tool-centric, Egyptian adoption is driver-centric, offering a richer perspective on how local risks reshape adoption patterns.

Client support drivers

User (or client) support ranked second among the components of the general process. This construct exhibits a wider range of loadings, from 0.560 on D3 to 0.856 on D12, indicating variability in the impact of different facets of client support. The higher loadings seen in D11, D12, and D13 emphasize the importance of quality customer service, reliable technical support, and proactive client engagement in facilitating cloud services. Conversely, the lower loading on D3 points to certain client support elements that may be less critical or effective. Prioritizing enhancements in the areas of client interaction that show the highest loadings can lead to more significant improvements in user satisfaction and service quality. Tehrani and Shirazi31 contended that user (or top administration) backing and the stakeholder’s readiness to partake in CC implementation in the building business considerably influence the acceptance of CC. This aspect constitutes a 0.373 path coefficient. Some stakeholders in construction believe that these variables affect the costs for the user to implement CC technology. Murad and Fatema152 identified cost as a critical problem that has to be considered when assessing whether or not CC services must be applied.

Moreover, the duty, i.e., required conservational guidelines for presenting sustainability principles, must be resolved if the specialists cooperate with the top management and client to ascertain and offer appropriate support (including monetary incentives) to meet these standards. Therefore, top management influences the adoption of CC tools in the company since it can link users with the benefits of CC service, adding value to its vision11.

Organisation drivers

The organization is the third main constituent of CC drivers. Regarding drivers, the path coefficient ‘organization’ is 0.360. The indicators tied to organizational structure and culture show loadings ranging from 0.560 to 0.857, with D5, D6, and D14 demonstrating strong contributions. These elements likely represent internal policies, corporate culture, and organizational readiness for technological advancements, which are crucial for supporting cloud initiatives. The lower loading on D1 suggests some organizational components might not directly influence cloud computing outcomes, indicating a potential area to reevaluate or deprioritize in favor of more impactful activities. The value obtained was comparable to Simamora and Sarmedy153. Similarly, Priyadarshinee154 itemized that the business efficiency in CC might depend on the company’s cloud delivery approach. Moreover, the obligation (i.e., requiring environmental regulations) for implementing sustainability standards will be resolved if the authorities work with the client and upper management to determine and offer appropriate assistance (i.e., monetary rewards) to fulfill those requirements. As a result, top management has an impact on how cloud technology is implemented in a company since it can introduce people to new developments in cloud services, which enhances the company’s vision11. Having the support of upper management could help the ICT division thrive, especially in cloud computing. Because cloud computing will be used to support those activities, this strategy will result in the company’s operations being more in line with its vision and mission71. As a result, the processes will get better. To back up the assertion made by Oliveira, et al90.. Because innovation is one of the most important things that the construction industry needs to keep for resource management105,116,155.

Conclusion and implications

Egypt is grouped under third-world nations and is among the densely populated countries in North and East Africa with a poor ecological standard in the framework of an emerging nation. It is expected to be a stable, diversified, and sustainable country. Additionally, its building industry lacked research on cloud computing (CC) adoption drivers concerning building business. Therefore, this research’s results lay the foundation for CC implementation by the building sector in Egypt. The nation’s building industry could use these findings to implement CC. If implemented, CC would be a valuable policy that reduces construction project costs through CC tools. Cloud computing relies heavily on building activities, and in third-world nations, its application is still at an infant stage. Egypt has faced discrepancies and abnormalities in the worth of large-scale construction schemes. CC can be implemented to moderate those glitches.

The EFA was performed to classify the building undertakings in the Egyptian building sector. The results indicated that these activities could be grouped under five key components: proposal and storage, management, pre-contract phase, communication and assessment, and lastly, back-office events. Additionally, the PLS-SEM technique was applied to explore the drivers of CC concerning the major driver influencing the CC implementation, trailed by the organization, user approval, and business-based factor drivers in the order of significance. Findings from PLS-SEM indicated that CC has the utmost impact on controlling undertakings, monitored by storage and design, pre-contract tasks, communication and estimation, and back-office tasks. The proposed model has revealed that the results are acceptable concerning the potential for improving building activity via adopting CC drivers.

Conversely, top management can supervise the CC means and teams based on the CC drivers’ impact and improve their effective participation by targeting improved construction efficacy. Besides, adopting CC drivers has influenced the success of construction activities, and CC implementation has led to overall project success. Therefore, this study offers important theoretical and managerial contributions and implications to the building sector as follows:

Theoretical contributions

-

i.

Based on the available scholarly background literature, there is a gap concerning adopting CC drivers. Thus, this study has narrowed this gap by exploring the CC implementation drivers in the existing literature.

-

ii.

The proposed model lays the foundation for CC implementation, especially in Egypt and similar developing nations. The study examined the CC implementation drivers through the predicted model. The identified drivers would assist in resolving the present barriers thwarting the adoption of CC by the Egyptian building sector. Hence, the gap in CC theory and practices has been theoretically reduced.

-

iii.

In terms of impact on the scientific basis, this study contributes to construction engineering managers’ understanding of CC drivers and their implementation principles; therefore, the results could serve as a basis for academic research concerning CC technology and implementation drivers in developing countries, particularly Egypt.

-

iv.

The methodological outline offers the researchers a basis for further analysis of CC implementation drivers’ positive and significant impact on the building activities and offers the basis for its application by the building projects.

-

v.

In addition, the results have contributed by defining and identifying additional variables to the theoretical framework, including the CC drivers’ impact on construction schemes.

-

vi.

The construction-based CC and adoption studies concentrated on developed nations and fewer developing countries, including the USA, UK, Australia, China, KSA, and Malaysia. Hence, few researches have been performed on CC implementation in third-world nations, e.g., Egypt. Thus, this study has laid a background for further exploration of this topic in emerging nations by considering the Egyptian building sector’s research background to enhance the sustainability of local building projects and reduce the research gap.

Practical implications

The CC drivers’ reordering can be useful in founding a standard procedure for stakeholders, including project-building parties, by employing CC to achieve a more successful building process in the schemes. Additionally, the rendering might serve as a framework for the effective development of a new model that integrates CC-building participants. Additionally, this study contributes significantly to making managerial decisions, which could have a significant implication in the building sector as follows:

-

i.

It offers a CC adoption catalogue and its associated effects on building schemes. It highlights its competitive advantage and global market sustainability via different CC integrations.

-

ii.

It enables clients, contractors, and consulting companies to assess and choose the finest implementation driver for CC to enhance the construction scheme’s planning, success, and efficiency.

-

iii.

This study presented many implications for experts, owners of projects, and contractors regarding the success of CC implementation in their projects. The study also enables all the concerned participants to achieve the three critical success factors of a scheme concerning quality, cost, and time by implementing CC on building activities, which influences the overall success of building activities.

-

iv.

The findings could guide strategic decisions, especially in prioritizing areas for investment and development. For instance, if an organization is lagging in technological aspects, the model suggests that improvements in this area could significantly impact cloud computing implementation success.

-

v.

Understanding the relative impact of each driver allows for more informed resource allocation. Management might allocate resources not just based on the immediate needs but also considering which investments (technology upgrades, customer service improvements, or organizational restructuring) would yield the most significant boost to cloud implementation efforts.

-

vi.

For organizational factors, developing policies that promote a culture of innovation and technology adoption could be beneficial. Such policies might include training programs, incentives for teams that effectively implement cloud solutions, and creating cross-departmental committees to oversee and guide cloud adoption.

The findings of this study provide actionable insights for industry practitioners and policymakers in Egypt’s construction sector, where cloud computing (CC) adoption remains limited but urgently needed to improve project performance and sustainability. The reordering of CC drivers—Technology, Client Support, and Organization—offers a foundation for a structured procedure that stakeholders can follow to guide digital transformation in building projects.

-

1.

For Managers and Organizations: The results suggest that technological readiness (β = 0.378) has the strongest influence on CC adoption. Egyptian construction firms should prioritize investments in ICT infrastructure, interoperability tools, and scalable digital platforms, as these improvements will yield the most significant impact. Organizational policies should also support digital innovation through training programs, performance-based incentives, and cross-departmental committees dedicated to CC integration.

-

2.

For Clients and Contractors: Client support (β = 0.372) is nearly as critical as technology itself. This highlights the need for building trust and transparency in Egypt’s project environment, where client-payment inconsistencies and financial risks are common. Clients can use the CC adoption catalogue developed in this study to evaluate contractor readiness, while contractors can benchmark their technological and organizational preparedness against industry standards.

-

3.

For Policymakers and Regulators: The findings emphasize that sustainable CC adoption in Egypt requires enabling policies. Regulatory frameworks should incentivize digital investment (e.g., tax credits, subsidies for SMEs) and establish standards for data security, interoperability, and reliable e-payment systems. By providing a stable policy environment, the government can strengthen both client confidence and organizational commitment to CC adoption.

-

4.

For the Construction Industry at Large: This study shows how CC adoption can help stakeholders achieve the three critical success factors of construction projects—quality, cost, and time—while contributing to sustainability goals. The decision support model provided here gives practitioners a structured approach to align CC investments with project efficiency, stakeholder collaboration, and long-term resilience.

Limitations and future research directions

The adoption of cloud computing (CC) in Egypt’s construction sector is likely to significantly evolve over the next 5-10 years. This progression will hinge on various factors, including increased awareness of CC benefits, technological advancements, and a stronger regulatory framework. To support this transition, there is a need for additional research that addresses several key areas:

-

1.

Expanded Geographic Scope: Future studies should expand beyond the initial regional and geographical limitations to include a more diverse range of locations within Egypt. This will help generalize the findings more broadly across different environments and market conditions within the country.

-

2.

Increased Sample Size and Diversity: Increasing the sample size and including a more diverse group of participants, such as small-scale contractors and different types of stakeholders in the construction industry, will enhance the reliability and validity of the research outcomes. This broader participant base should encompass various roles beyond just consultants, contractors, and clients to include policymakers, IT specialists, and project managers.

-

3.

Comprehensive Study of Barriers and Tools: There’s a crucial need for research that not only explores the drivers but also addresses the barriers to CC adoption. Understanding these obstacles—whether technological, financial, or cultural—will be key to developing strategies to overcome them. Additionally, studying the specific tools and applications of CC in construction will provide practical insights for their effective implementation.

-

4.

Impact on Building Activities: Studies should also focus on how CC can transform different building activities, from design and planning to execution and management. Research could explore how CC tools enhance collaboration, data management, and operational efficiency in real-time construction environments.

-

5.

Training and Development Programs: With the requirement for top management support in CC initiatives, future research should explore the development of targeted training and educational programs. These programs would equip both new organizations and their employees with the necessary skills and knowledge to leverage CC technologies effectively.

-

6.

Policy and Regulatory Frameworks: To facilitate a smoother transition and greater adoption of CC, research should guide the creation and refinement of policies and regulations. This would involve collaboration between governmental bodies, industry leaders, and academic institutions to create a conducive environment for CC integration into mainstream construction processes.

-

7.

Comparative Studies: Future research could compare CC adoption drivers across multiple developing countries (e.g., Egypt vs. Jordan or Nigeria) to identify context-specific versus generalizable drivers. This would strengthen external validity and allow benchmarking across markets with similar challenges.

-

8.

The model could be used as a basis for further research to explore how these drivers interact with other potential variables not included in the current model, such as external market conditions or specific industry challenges.

-

9.

Adjustments could be considered if, in future assessments, the balance of influence among the drivers changes due to evolving technological landscapes or shifts in consumer expectations related to cloud services.

-

10.

Longitudinal Designs: To address the limitations of a cross-sectional design, future studies could track CC adoption over several years. This would reveal how drivers evolve with changing technological landscapes, economic stability, and government policies.

-

11.

One limitation of this study is that exploratory factor analysis was conducted using an orthogonal Varimax rotation. While Varimax provides a clear and interpretable structure by assuming uncorrelated factors, oblique rotations such as Promax or Direct Oblimin could allow for factor correlations and may offer additional insights into the interrelationships among drivers. Since inter-construct relationships were modeled explicitly in the subsequent PLS-SEM stage, Varimax was considered appropriate for our analysis. Nevertheless, future studies could explore the use of oblique rotations to further examine correlations among factors at the exploratory stage, thereby complementing the structural modeling approach

By addressing these areas through comprehensive research and strategic initiatives, Egypt’s construction sector can effectively leverage cloud computing to achieve greater efficiency and competitiveness on both a regional and global scale.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Olawumi, T. O., Chan, D. W., Wong, J. K. & Chan, A. P. Barriers to the integration of BIM and sustainability practices in construction projects: A Delphi survey of international experts. J. Build. Eng. 20, 60–71 (2018).

Mousa, A. A Business approach for transformation to sustainable construction: an implementation on a developing country. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 101, 9–19 (2015).

Gan, X. et al. How affordable housing becomes more sustainable? A stakeholder study. J. Clean. Prod. 162, 427–437 (2017).

Kissi, E., Boateng, E., & Adjei-Kumi, T. Strategies for implementing value management in the construction industry of Ghana. In Proceedings of the DII-2015 Conference on Infrastructure Development and Investment Strategies for Africa, 255–267 (2015).

Adeyemi, L.A., & Idoko, M. Developing Local Capacity for Project Management--Key to Social and Business Transformation in developing Countries. 2008: Project Management Institute.

Maceika, A., Bugajev, A. & Šostak, O. R. The modelling of roof installation projects using decision trees and the AHP Method. Sustainability 12(1), 59 (2020).

Acre F, Wyckmans A (2015), "The impact of dwelling renovation on spatial quality: The case of the Arlequin neighbourhood in Grenoble, France". Smart and Sustainable Built Environment, 4(3), 268–309 https://doi.org/10.1108/SASBE-05-2015-0008 (2015).

Parn, E. A., & Edwards, D. Cyber threats confronting the digital built environment: Common data environment vulnerabilities and block chain deterrence. Eng. Construct. Archit. Manage. (2019)

Ghosh, A., Edwards, D. J., & Hosseini, M. R. Patterns and trends in Internet of Things (IoT) research: future applications in the construction industry. Eng. Construct. Archit. Manage. 2020.

Chris Newman, David Edwards, Igor Martek, Joseph Lai, Wellington Didibhuku Thwala, Iain Rillie; Industry 4.0 deployment in the construction industry: a bibliometric literature review and UK-based case study. Smart and Sustainable Built Environment 12 November 2021; 10(4), 557–580. https://doi.org/10.1108/SASBE-02-2020-0016

Oke, A. E., Kineber, A. F., Albukhari, I., Othman, I. & Kingsley, C. Assessment of cloud computing success factors for sustainable construction industry: The case of Nigeria. Buildings 11(2), 36 (2021).

Durdyev, S., Ismail, S., Ihtiyar, A., Bakar, N. F. S. A. & Darko, A. A partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) of barriers to sustainable construction in Malaysia. J. Clean. Prod. 204, 564–572 (2018).

Chan, A. P. & Adabre, M. A. Bridging the gap between sustainable housing and affordable housing: The required critical success criteria (CSC). Build. Environ. 151, 112–125 (2019).

Sbci, U. Buildings and climate change: summary for decision-makers. United Nations Environmental Programme, Sustainable Buildings and Climate Initiative, Paris, 1–62 (2009).

Dezhi, L. et al. Assessing the integrated sustainability of a public rental housing project from the perspective of complex eco-system. Habitat Int. 53, 546–555 (2016).

Barakat, M. S., Naayem, J. H., Baba, S. S., Kanso, F. A., Borgi, S. F., Arabian, G. H., & Nahlawi, F. N. Egypt economic report: Between the recovery of the domestic economy and the burden of external sector challenges. http://www.bankaudigroup.com (2016).

Soliman, M. M. A. I. Risk Management in International Construction Joint Ventures in Egypt (University of Leeds, 2014).

Pingping Luo, Yutong Sun, Shuangtao Wang, Simeng Wang, Jiqiang Lyu, Meimei Zhou, Kenichi Nakagami, Kaoru Takara, Daniel Nover, Historical assessment and future sustainability challenges of Egyptian water resources management, Journal of Cleaner Production, 263, 121154, ISSN 0959-6526, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.12115 (2020).

Abd El-Razek, M., Bassioni, H. & Mobarak, A. Causes of delay in building construction projects in Egypt. J. Construct. Eng. Manage. 134(11), 831–841 (2008).

Khodeir, L. M. & El Ghandour, A. Examining the role of value management in controlling cost overrun [application on residential construction projects in Egypt]. Ain Shams Eng. J. 10(3), 471–479 (2019).

Kineber, A. F., Othman, I., Oke, A. E., Chileshe, N. & Buniya, M. K. Identifying and assessing sustainable value management implementation activities in developing countries: the case of Egypt. Sustainability 12, 9143 (2020).

Wolstenholme, A., et al. Never waste a good crisis: a review of progress since Rethinking Construction and thoughts for our future (2009)

Russell-Smith, S. V. & Lepech, M. D. Cradle-to-gate sustainable target value design: integrating life cycle assessment and construction management for buildings. J. Clean. Prod. 100, 107–115 (2015).

Zhong Fang, Xiang Gao, Chuanwang Sun, Do financial development, urbanization and trade affect environmental quality? Evidence from China, Journal of Cleaner Production, 259, 120892, ISSN 0959-6526, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120892 (2020).

Spychalska-Wojtkiewicz, M. The relation between sustainable development trends and customer value management. Sustainability 12(14), 5496 (2020).

Ganesan, M., Kor, A.-L., Pattinson, C. & Rondeau, E. Green cloud software engineering for big data processing. Sustainability 12(21), 9255 (2020).

Dahiru, A. A. & Abubakar, H. Cloud computing adoption: A cross-continent overview of challenges. Nigerian J. Basic Appl. Sci. 25(1), 23–31 (2017).

Yaseen, Z. M., Ali, Z. H., Salih, S. Q. & Al-Ansari, N. Prediction of risk delay in construction projects using a hybrid artificial intelligence model. Sustainability 12(4), 1514 (2020).

Pańkowska, M., Pyszny, K. & Strzelecki, A. Users’ adoption of sustainable cloud computing solutions. Sustainability 12(23), 9930 (2020).

Ganesan, M. K., Kor, A.-L., Pattinson, C. & Rondeau, E. Green cloud software engineering for big data processing. Sustainability 12, 9255 (2020).

Tehrani, S. R. & Shirazi, F. Factors influencing the adoption of cloud computing by small and medium size enterprises (SMEs). In International Conference on Human Interface and the Management of Information 631–642 (Springer, 2014).

Oke, A. E., Kineber, A. F., Albukhari, I., Othman, I. & Kingsley, C. Assessment of cloud computing success factors for sustainable construction industry: The case of Nigeria. Buildings 11, 36 (2021).

H. Al-Mascati and A. H. Al-Badi, Critical success factors affecting the adoption of cloud computing in oil and gas industry in Oman. In 2016 3rd MEC International Conference on Big Data and Smart City (ICBDSC), 1–7 (IEEE, 2016).

Astri, L. Y. A study literature of critical success factors of cloud computing in organizations. Proc. Comput. Sci. 59, 188–194 (2015).

Fang, Y., Cho, Y. K., Zhang, S. & Perez, E. Case study of BIM and cloud–enabled real-time RFID indoor localization for construction management applications. J. Construct. Eng. Manage. 142(7), 05016003 (2016).

Schniederjans, D. G. & Hales, D. N. Cloud computing and its impact on economic and environmental performance: A transaction cost economics perspective. Decis. Support Syst. 86, 73–82 (2016).

Zainon, N., Rahim, F. A., Salleh, H. The information technology application change trend: Its implications for the construction industry. J. Surv. Construct. Propert. 2(2), 2011.

Priyadarshinee, P., Jha, M. K., Raut, R. D., Kharat, M. G. & Kamble, S. S. To identify the critical success factors for cloud computing adoption by MCDM technique. Int. J. Bus. Inf. Syst. 24(4), 469–510 (2017).

Mohamad-Ramly, Z., Shen, G. Q. & Yu, A. T. Critical success factors for value management workshops in Malaysia. J. Manage. Eng. 31(2), 05014015 (2015).

Rockart, J. F. Chief executives define their own data needs. Harv. Bus. Rev. 57(2), 81–93 (1979).

Chan, A. P., Ho, D. C. & Tam, C. Design and build project success factors: Multivariate analysis. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 127(2), 93–100 (2001).

Yu, A. T., Shen, Q., Kelly, J. & Lin, G. A value management approach to strategic briefing: An exploratory study. Archit. Eng. Design Manage. 2(4), 245–259 (2006).

Saraph, J. V., Benson, P. G. & Schroeder, R. G. An instrument for measuring the critical factors of quality management. Decis. Sci. 20(4), 810–829 (1989).

Hentschel, R., Leyh, C., Baumhauer, T. Critical success factors for the implementation and adoption of cloud services in SMEs. In Proceedings of the 52nd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, 2019.

Summers, J. O. Guidelines for conducting research and publishing in marketing: From conceptualization through the review process. In How to Get Published in the Best Marketing Journals (Edward Elgar Publishing, 2019).

Aghimien DO, Oke AE, Aigbavboa CO (2018), "Barriers to the adoption of value management in developing countries". Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 25(7), 818–834 https://doi.org/10.1108/ECAM-04-2017-0070

Gonzalez-Caceres, A., Bobadilla, A. & Karlshøj, J. Implementing post-occupancy evaluation in social housing complemented with BIM: A case study in Chile. Build. Environ. 158, 260–280 (2019).

Kineber, A. F., Oke, A. E., Alyanbaawi, A., Abubakar, A. S. & Hamed, M. M. J. S. Exploring the cloud computing implementation drivers for sustainable construction projects—a structural equation modeling approach. Sustainability 14(22), 14789 (2022).

Etro, F. The economic impact of cloud computing on business creation, employment and output in Europe. Rev. Bus. Econ. 54(2), 179–208 (2009).

Morton, G., & Alford, T. The economics of cloud computing: Addressing the benefits of infrastructure in the cloud. Booz Allen Hamilton. https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=The%20Economics%20of%20Cloud%20Computing%3A%20Addressing%20the%20Benefits%20of%20Infrastructure%20in%20the%20Cloud.%20White%20Paper&publication_year=2009&author=T.%20Alford&author=G.%20Morton. (2009) accessed on Sep 2025.

Gangahar, M. Government subsidies to micro, small and medium enterprises deploying cloud computing. (accessed 18 May 2017) http://m.dailyhunt.in/news/india/english/theeconomist-epaper-indecono/government+subsidies+to+micro+small+and+medium+enterprises+deploying+cloud+computing-newsid-65499905.

NIST. Final version of NIST cloud computing definition published. (accessed 25 May 2017) https://www.nist.gov/news-events/news/2011/10/final-version-nist-cloud-computingdefinition-published. (2011).

Gartner. Maturity model for enterprise collaboration and social software (accessed 25 April 2014) www.gartner.com/id¼1724649. (2011)

Nuseibeh, H. Adoption of cloud computing in organizations (2011)

Oke, A. E., Kineber, A. F., Alsolami, B. & Kingsley, C. Adoption of cloud computing tools for sustainable construction: A structural equation modelling approach. J. Facil. Manag. 21(3), 334–351 (2023).

Musarat, M. A., Alaloul, W. S., Khan, M. H. F., Ayub, S. & Guy, C. P. L. Evaluating cloud computing in construction projects to avoid project delay. J. Open Innovat. Technol. Market Comple. 10(2), 100296 (2024).

Solanki, A., Sarkar, D. & Kapdi, P. Evaluation of key performance indicators of internet of things and cloud computing for infrastructure projects in gujarat, india through consistent fuzzy preference relations approach. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 24(7), 707–721 (2024).

Oke, A. E., Kineber, A. F., Al-Bukhari, I., Famakin, I. & Kingsley, C. Exploring the benefits of cloud computing for sustainable construction in Nigeria. J. Eng. Design Technol. 21(4), 973–990 (2023).

Solanki, A., Sarkar, D. & Shah, D. Evaluation of factors affecting the effective implementation of Internet of Things and cloud computing in the construction industry through WASPAS and TOPSIS methods. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 24(2), 226–239 (2024).

Low, C., Chen, Y., & Wu, M. Understanding the determinants of cloud computing adoption. Industrial management & data systems, 111(7), 1006-1023. https://doi.org/10.1108/02635571111161262. (2011).

Hemlata Gangwar, Hema Date, R Ramaswamy; Understanding determinants of cloud computing adoption using an integrated TAM-TOE model. Journal of Enterprise Information Management; 28(1), 107–130. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEIM-08-2013-0065. 9 February 2015.

Ali, M., & Miraz, M. H. Cloud computing applications. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Cloud Computing and eGovernance, Vol. 1 (2013)

Chong, A.Y.-L. & Bai, R. Predicting open IOS adoption in SMEs: An integrated SEM-neural network approach. Expert Syst. Appl. 41(1), 221–229 (2014).

Afolabi, A. Rapheal, O., Fagbenle, O., & Mosaku, T. The economics of cloud-based computing technologies in construction project delivery. Int. J. Civ. Eng. Technol. (2017)

Shimba, F. J. Cloud computing: Strategies for cloud computing adoption (LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing, 2010).

Sadeeq, M., Abdulla, A. I., Abdulraheem, A. S. & Ageed, Z. S. Impact of electronic commerce on enterprise business. Technol. Rep. Kansai Univ 62(5), 2365–2378 (2020).

Haji, L. M. et al. Dynamic resource allocation for distributed systems and cloud computing. TEST Eng. Manage. Product. Eng. Rev. 83, 22417–22426 (2020).

Hosseinian-Far, A., Ramachandran, M., & Slack, C. L. Emerging trends in cloud computing, big data, fog computing, IoT and smart living. In Technology for smart futures 29–40 (Springer, 2018).

Ren, J., Guo, H., Xu, C. & Zhang, Y. Serving at the edge: A scalable IoT architecture based on transparent computing. IEEE Network 31(5), 96–105 (2017).

Gravina, R., Alinia, P., Ghasemzadeh, H. & Fortino, G. Multi-sensor fusion in body sensor networks: State-of-the-art and research challenges. Inf. Fusion 35, 68–80 (2017).

Oke, A. E. et al. Barriers to the implementation of cloud computing for sustainable construction in a developing economy. Int. J. Build. Pathol. Adapt. 41(5), 988–1013 (2023).

Aghimien, D., Aigbavboa, C. O., Chan, D. W. & Aghimien, E. I. Determinants of cloud computing deployment in South African construction organisations using structural equation modelling and machine learning technique. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 31(3), 1037–1060 (2024).

Das, R. K., Patnaik, S. & Misro, A. K. Adoption of cloud computing in e-governance. In International Conference on Computer Science and Information Technology 161–172 (Springer, 2011).

Marston, S., Li, Z., Bandyopadhyay, S., Zhang, J. & Ghalsasi, A. Cloud computing—The business perspective. Decis. Support Syst. 51(1), 176–189 (2011).

Raghavan, A., Demircioglu, M. A. & Taeihagh, A. Public health innovation through cloud adoption: A comparative analysis of drivers and barriers in Japan, South Korea, and Singapore. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18(1), 334 (2021).

House, T. W. Federal Cloud Computing Strategy. Available online: https://marketplace.vion.com/order/uploads/VIONMP5/federal-cloud-computing-strategy.pdf (accessed 3 July 2020)

Millard, J. ICT-enabled public sector innovation: trends and prospects. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Theory and Practice of Electronic Governance 77–86 (2013).

Kuiper, E., Van Dam, F., Reiter, A., & Janssen, M. Factors influencing the adoption of and business case for Cloud computing in the public sector. In eChallenges e-2014 Conference Proceedings, 1–10 (IEEE, 2014)

Polyviou, A., & Pouloudi, N. Understanding cloud adoption decisions in the public sector. In 2015 48th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, IEEE, 2085–2094 (2015).

Vu, K., Hartley, K. & Kankanhalli, A. Predictors of cloud computing adoption: A cross-country study. Telematics Informatics 52, 101426 (2020).

Albury, D. Fostering innovation in public services. Public Money Manag 25(1), 51–56 (2005).

Windrum, P., & Koch, P. M. Innovation in public sector services: entrepreneurship, creativity and management (Edward Elgar Publishing, 2008)

Currie, W., & Seddon, J. A cross-country study of cloud computing policy and regulation in healthcare (2014)

Lin, A. & Chen, N.-C. Cloud computing as an innovation: Percepetion, attitude, and adoption. Int. J. Inf. Manage. 32(6), 533–540 (2012).

Willcocks, L. P., Venters, W., & Whitley, E. A. Cloud sourcing and innovation: slow train coming? A composite research study. Strategic Outsourcing: An International Journal, 6(2), 184-202 https://doi.org/10.1108/SO-04-2013-0004. (2013).

Chandrasekaran, A., Kapoor, M., & Sullivan. State of Cloud Computing in the Public Sector–A Strategic analysis of the business case and overview of initiatives across Asia Pacific. Frost, pp. 1–17 (2011)

Haini, S. I. Citizen Centric Impact on Success Factors of Digital Government Maturity in Malaysian Public Sector (2017)

Sharma, R. The impact of virtualization in cloud computing. Int. J. Recent Dev. Eng. Technol. 3(1), 197–202 (2014).

Chong, H.-Y., Wong, J. S. & Wang, X. An explanatory case study on cloud computing applications in the built environment. Autom. Constr. 44, 152–162 (2014).

Oliveira, T., Thomas, M. & Espadanal, M. Assessing the determinants of cloud computing adoption: An analysis of the manufacturing and services sectors. Inf. Manage. 51(5), 497–510 (2014).

Stewart, R. A. & Mohamed, S. Evaluating the value IT adds to the process of project information management in construction. Autom. Constr. 12(4), 407–417 (2003).

Othman, I., Kineber, A., Oke, A., Zayed, T., & Buniya, M. Barriers of value management implementation for building projects in Egyptian construction industry. Ain Shams Eng. J. (2020)

Mohanad K. Buniya, Idris Othman, Riza Yosia Sunindijo, Ahmed Farouk Kineber, Eveline Mussi, Hayroman Ahmad, Barriers to safety program implementation in the construction industry, Ain Shams Engineering Journal, 12(1), Pages 65-72, ISSN 2090-4479, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asej.2020.08.002. (2021).

Olanrewaju, O. I., Kineber, A. F., Chileshe, N. & Edwards, D. J. Modelling the impact of building information modelling (BIM) implementation drivers and awareness on project lifecycle. Sustainability 13(16), 8887 (2021).

Ahmed Farouk Kineber, Idris Othman, Ayodeji Emmanuel Oke, Nicholas Chileshe, Tarek Zayed, Exploring the value management critical success factors for sustainable residential building – A structural equation modelling approach, Journal of Cleaner Production, 293, 2021, 126115, ISSN 0959-6526, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126115.

Field, A. Discovering statistics using SPSS (3. baskı) (Sage Publications, 2009).

Robert, O. K., Dansoh, A. & Ofori-Kuragu, J. K. Reasons for adopting public–private partnership (PPP) for construction projects in Ghana. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 14(4), 227–238 (2014).