Abstract

Mechanical ventilation was frequently conducted in late preterm and term newborn infants because of their severity of neonatal respiratory distress syndrome (NRDS), but the level of positive end expiratory pressure (PEEP) used was not explicit. This study aimed to investigate the efficacy and safety of higher-PEEP in the treatment of NRDS in these infants. Initially, 80 newborn late preterm and term infants diagnosed with NRDS were enrolled, a total of 26 infants were excluded because they were not within the gestational age range of 34+ 0 to 39+ 6 weeks or did not receive mechanical ventilation. Of 54 eligible infants, 6 were excluded: 3 for pre-existing pneumothorax before mechanical ventilation, 1 for hospital transfer, 1 for withdrawal of treatment, and 1 for misdiagnosis with transient tachypnea. Ultimately, 48 infants remained. Following a simple randomization procedure, 23 were assigned to higher-PEEP group and 25 to the control group. The duration of mechanical ventilation was regarded as the primary outcome. We also collected and analyzed data of other clinical factors. We found that higher-PEEP group had significantly shorter durations of mechanical ventilation (P = 0.008) and oxygen inhalation (P = 0.002) compared to the control. Additionally, the fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) (P = 0.001) and oxygenation index (OI) (P = 0.048) at 24 h after birth were lower in higher-PEEP group compared to the control. Furthermore, higher-PEEP group had a shorter duration of hospitalization (P = 0.033). However, no significant differences were observed in the comparisons of complications between the two groups. In summary, higher PEEP could reduce the duration of mechanical ventilation by preserving adequate functional residual capacity, without increasing rates of adverse effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

NRDS was a common disease in preterm infants, primarily due to lung immaturity and insufficient pulmonary surfactants. The late preterm infants (born at gestational age of 34 to 36+ 6 weeks) and term infants still had certain morbidity, mainly due to prematurity, gestational diabetes mellitus and cesarean section, and frequently presented with more severe conditions, requiring mechanical ventilation and repeat surfactants. Traditional mechanical ventilation protocols were effective but might cause lung injury. Some scholars observed that pediatricians tended to use low levels of PEEP and inherently accepted higher FiO2, although such practices might lead to worse outcomes1. In the treatment of mechanical ventilation in NRDS, peak inspiratory pressure (PIP) and FiO2 were preferentially increased because of small tidal volume (VT) and impaired oxygenation function, but the optimal PEEP remained uncertain.

The commonly used levels for PEEP were 3–9 cmH2O2. Some clinical evidences suggested that PEEP levels ≥ 5 cmH2O during mechanical ventilation might be beneficial by preserving functional residual capacity (FRC) and preventing lung collapse3. PEEP levels were dynamically adjusted between 6 and 8 cmH2O in clinical practice. But we observed that the levels of PEEP at 6–8 cmH2O often failed to maintain early stabilization in late preterm and term newborn infants needing mechanical ventilation, some cases exhibiting rapid deterioration, necessitating higher PIP and FiO2 to compensate for inadequate gas exchange. This compensatory strategy, however, risked exacerbating alveolar hyperoxia injury, barotrauma, and atelectrauma (cyclic collapse-reopening injury).

Given that PEEP primarily served to maintain FRC, we hypothesized that there might be a critical PEEP threshold that effectively maintained lung inflation during the expiratory phase in mechanically ventilated NRDS cases with markedly reduced FRC, without harming the immature lung. Clinical evidence showed that higher PEEP had already been adopted in delivery room resuscitation and post-extubation non-invasive respiratory support4. So, we conducted the present study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of higher PEEP levels in late preterm infants and term infants.

Results

Initially, 80 newborn late preterm and term infants diagnosed with NRDS were enrolled, a total of 26 infants were excluded because they were not within the gestational age range of 34+ 0 to 39+ 6 weeks or did not receive mechanical ventilation. All parents of the remaining 54 infants provided written informed consent before the allocation. Of 54 eligible infants, 6 were excluded: 3 for pre-existing pneumothorax before mechanical ventilation, 1 for hospital transfer, 1 for withdrawal of treatment, and 1 for misdiagnosis with transient tachypnea. Ultimately, 48 infants remained. Following a simple randomization procedure, 23 were assigned to higher-PEEP group and 25 to the control group. Twins or multiples were individually randomized (Fig. 1). All these late preterm and term newborn infants developed respiratory distress within 6 to 12 h after birth and were enrolled within 12 h after birth.

A comparison between the two groups showed no difference in the perinatal factors and demographic characteristics of the late preterm and term infants, shown in Table 1. The SNAPPE-II score (Score for Neonatal Acute Physiology with Perinatal Extension II) assessed disease severity by scoring six physiological parameters based on their most abnormal values during the first 12 h after admission. The six components were mean blood pressure, temperature, ratio of arterial oxygen partial pressure to fractional inspired oxygen (PaO2/ FiO2 ratio), serum pH, urine output, multiple seizures. These components provided a quantitative measure of the infant’s acute physiological stability. As shown in Table 2, there was no difference in SNAPPE-II score between the two groups (P = 0.983). Upon comparing PEEP, PIP, MAP, FiO2, and OI between the two groups after initiation of mechanical ventilation (i.e., prior to PEEP adjustment), no significant intergroup differences were observed.

In the control group, three neonates were switched to high-frequency oscillatory ventilation (HFOV) due to worsening status. Their durations of conventional mechanical ventilation were 16, 18, and 22 h, respectively. After transitioning to HFOV, both MAP and FiO2 were increased compared to previous settings and maintained at higher parameters beyond 24 h.

Reduced duration of mechanical ventilation in higher-PEEP group

As shown in Fig. 2; Table 2, higher-PEEP group had significantly shorter duration of mechanical ventilation compared to the control (P = 0.008). However, there was no significant difference in the duration of non-invasive ventilation between two groups (P = 0.608). Further analysis revealed that the duration of oxygen inhalation also differed significantly (P = 0.002), consistent with the observed differences in mechanical ventilation duration.

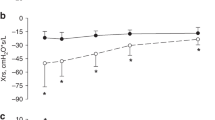

Increased PEEP, PIP and mean airway pressure (MAP) in higher-PEEP group

During the mechanical ventilation, higher-PEEP group exhibited significantly higher PEEP (P < 0.001), PIP (P = 0.005), unsurprisingly, and MAP (P = 0.010) at 24 h after birth during the clinical climax compared to the control (Fig. 3A-C); but the ΔP (driving pressure, PIP minus PEEP) was not significantly different (P = 0.881; Fig. 3D).

Reduced FiO2 and OI in higher-PEEP group

Interestingly, the FiO2 at 24 h after birth was markedly lower in higher-PEEP group (P = 0.001; Fig. 4A). When comparing the OI at 24 h after birth, we observed that higher-PEEP group had lower OI than the control (P = 0.048; Fig. 4B), suggesting improved oxygenation efficiency.

Reduced duration of hospitalization in higher-PEEP group

Furthermore, the duration of hospitalization was shorter in higher-PEEP group (P = 0.033; Fig. 5).

Comparisons of complications between two groups

We observed the clinical outcomes of both groups and found that higher-PEEP group exhibited fewer cases of moderate to severe pulmonary hypertension, though this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.292). In higher-PEEP group, three cases of moderate to severe pulmonary hypertension were identified by routine bedside echocardiography. None of these cases presented with a significant upper-lower limb oxygen saturation gradient, and their OI values did not reach the threshold for initiating vasoactive drug therapy. In the control group, seven cases of moderate to severe pulmonary hypertension were observed; one of these progressed to persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn and required treatment with inhaled nitric oxide, while the other six did not receive vasoactive drug therapy. Pulmonary hemorrhage occurred in one infant in the control, while no case was observed in higher-PEEP group. Both groups had one case of pneumothorax each; however, higher-PEEP group’s case was mild and required no intervention, whereas the control group’s case necessitated chest tube drainage. Encouragingly, no intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) occurred in higher-PEEP group, while the control had three cases of Grade I-II IVH, though this difference also lacked statistical significance. Furthermore, neither group experienced periventricular leukomalacia (PVL), retinopathy of prematurity (ROP), hemodynamically significant patent ductus arteriosus (hsPDA), neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC), late-onset sepsis, and ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) (Table 3).

Discussion

NRDS was a common disease in newborn infants, often requiring respiratory support due to its severity, posing significant challenges for neonatologists. Regarding the severe cases, conventional mechanical ventilation combined with surfactant therapy remained the most widely used approach. Modern ventilation strategies emphasized not only gas exchange efficacy but also lung protection.

The NRDS of late preterm and term newborn infants often required invasive mechanical ventilation and repeated doses of surfactants. These infants often exhibited better respiratory muscle compensation, the early diagnosis and treatment of NRDS in this population tended to occur later compared to preterm infants of lower gestational ages. By the time symptoms worsened, significant pulmonary collapse and exudation were often already evident, with a higher incidence of pulmonary hypertension or pneumothorax5, posing significant challenges in respiratory support. Moreover, or neonates born via cesarean section who develop NRDS, lung exudation was often very severe. The plasma proteins exuded into the alveoli further inhibit pulmonary surfactant activity. The duration of pulmonary surfactant efficacy might be shorter in these cases, potentially necessitating multiple doses6.

In this study, according to the treatment protocol of local clinicians, corticosteroids such as dexamethasone or betamethasone were not routinely administered prenatally for neonates delivered after 34 weeks’ gestation, as the use of antenatal steroids beyond 34 weeks of gestation remained controversial7. Additionally, the high cesarean section rates (78.3% in higher-PEEP group and 88.0% in the control) might further increase the risk of NRDS. We speculated that the development of NRDS was mainly due to prematurity, gestational diabetes mellitus and cesarean section.

Although it was widely recognized that optimal PEEP, lower VT, and reduced PIP were essential for improving ventilation and minimizing lung injury, there was still no consensus on the ideal PEEP level for late preterm and term infants. During the management of NRDS in late preterm and term infants, we also found that the PEEP levels at 6–8 cmH2O were frequently proved inadequate, necessitating higher PIP or FiO2 to achieve sufficient oxygenation, which could also cause lung injury8. To better maintain FRC, we increased PEEP levels to 8.5–11 cmH2O in clinical practice and evaluated the efficacy and safety of higher PEEP levels. Our primary outcome was the duration of mechanical ventilation, which showed a significant decrease in higher-PEEP group. Other improvements were also observed in outcomes such as the shorter duration of oxygen inhalation and hospitalization, and lower OI and FiO2. at 24 h after birth during the clinical climax compared to the control. However, no significant differences were observed in the comparisons of complications between the two groups.

Ultimately, 48 infants remained, 23 were assigned to higher-PEEP group and 25 to the control group. All these late preterm and term newborn infants developed respiratory distress within 6 to 12 h after birth and were enrolled within 12 h after birth. We compared the SNAPPE-II score and found no difference between the two groups. Upon comparing PEEP, PIP, MAP, FiO2, and OI between the two groups after initiation of mechanical ventilation (i.e., prior to PEEP adjustment), no significant intergroup differences were observed. The lack of statistical significance in these parameters was expected, as the initial ventilator settings for infants in both groups were highly similar at the time of enrollment, as defined in our intervention protocols.

During mechanical ventilation, PEEP served as a continuous airflow that helped to maintain alveolar stability and FRC, stabilize the chest wall and upper airway, decrease pulmonary resistance and reduce alveolar edema, thus improving VT and oxygenation, minimizing atelectasis, and reducing obstructive apnea9. When PEEP levels were inadequate, insufficient FRC and oxygenation could conduct persistent alveolar exudation, edema, hypoxia, and acidosis, further damaging pulmonary capillaries and leading to clinical complications, including persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn, gastrointestinal disorder, and cerebral injury10.

Given that the key pathophysiological mechanisms underlying NRDS progression were suboptimal FRC and reduced lung compliance, optimal PEEP was considered as the primary parameter of ventilator, which could also enhance alveolar gas reserve while expanding the exchange area between the respiratory membrane and capillaries, thereby prolonging gas exchange duration and opportunities, and it thinned the respiratory membrane and counteracted capillary exudation, ultimately enhancing ventilation efficiency and oxygenation. We considered whether a higher PEEP could be adopted to maintain near-physiological FRC, thereby reducing dependence on other parameters. In clinical practice, we routinely analyzed the inflection point on the pressure-volume curve to determine optimal PEEP. Notably, in severe NRDS cases characterized by markedly flattened P-V loops, the lower inflection point consistently demonstrated a rightward shift (higher pressure range), indicating increased alveolar recruitment pressure requirements. But the dentification of optimal PEEP levels was difficult.

Clinically, when using non-invasive ventilation to treat NRDS, the PEEP was often set higher than 8 cmH2O11. Another study in preterm lambs demonstrated that dynamic PEEP levels of 14–20 cmH2O in mechanical ventilation minimized lung injury compared to lower PEEP. Moreover, higher PEEP caused minimal cardiopulmonary interference, likely due to the use of lower ΔP at the same VT12. One study showed that sustained inflation and dynamic PEEP up to 15 cmH2O significantly decreased the intubation, surfactant administration in the delivery room, mechanical ventilation and its mean duration < 72 h of life, administration of a 2nd dose of surfactant, postnatal corticosteroids, and the rate of bronchopulmonary dysplasia13. Results from animal studies further suggested that using higher PEEP levels (8–12 cmH2O) in mechanical ventilation improved gas exchange and avoided lung collapse when compared to lower levels of PEEP14. This was precisely why we investigated the applicability of higher PEEP levels (8.5–11 cmH2O) in NRDS management.

In this study, we set PEEP levels at 6–8 cmH2O in the control and 8.5–11 cmH2O in higher-PEEP group, respectively. The lower limit of 8.5 cmH2O for higher-PEEP group was chosen because some patients did not require excessively high PEEP according to the clinical status. Both groups maintained their respective PEEP levels for at least 24 h, ensuring that all late preterm and term newborn infants received adequate pressure support before reaching the clinical climax of NRDS. Higher-PEEP group exhibited significantly higher PEEP, PIP, unsurprisingly, and MAP at 24 h after birth during the clinical climax compared to the control. The promising findings in this research were that we have identified not only significantly shorter duration of mechanical ventilation and oxygen inhalation, but also lower levels of FiO2, and OI in higher-PEEP group. Furthermore, the duration of hospitalization was shorter in higher-PEEP group, further supporting the potential benefits of higher PEEP ventilation strategy. Scholars also demonstrated that the use of higher MAP was safe and there was no more airleak15.

For newborn infants, the use of higher PEEP levels should be approached with caution due to the risk of air leak. However, we found that the control group developed one pneumothorax case necessitating closed thoracic drainage, whereas higher-PEEP group had only one mild pneumothorax case managed conservatively without intervention. Air leak primarily resulted from excessive alveolar volume, which occurred mainly due to pulmonary hyperinflation or uneven gas distribution10. Their FRC and lung compliance improved during treatment but never fully normalized to physiological levels despite receiving higher PEEP and surfactants. Consequently, their FRC never exceeded the normal range during the expiratory phase. Additionally, none of the late preterm and term newborn infants achieved excessive VT because of our strict VT control (4–6 ml/kg). When addressing uneven ventilation, we needed to focus the gas flow between the well-aerated alveoli and the collapsed alveoli.

As we all know, the greater the FRC of alveoli, the higher their compliance and the lower the distending pressure required during inspiration. In contrast, collapsed alveoli demanded substantially greater pressure to generate equivalent VT. Under the same inspiratory ΔP, alveoli with bette FRC tended to expand more easily, while those with poor FRC collapsed, leading to uneven ventilation, thus consequent atelectasis and hyperinflation. During this process, the delivered VT was consistently inadequate, necessitating increased respiratory effort by the infants to compensate. This compensatory mechanism further resulted in alveolar overdistension in regions with better FRC, ultimately precipitating air leak16. These could explain our clinical observations. In our study, we excluded three newborn infants because they had already developed pneumothorax prior to mechanical ventilation, who either received no PEEP or inadequate PEEP during non-invasive ventilation.

Conversely, optimal PEEP could recruit more alveoli for ventilation, thereby reducing atelectasis and pulmonary hyperinflation, which to some extent mitigated uneven alveolar gas distribution. Surfactant also exhibited comparable therapeutic effects, it was proved that surfactant use was associated with a significant decrease in risk of air leak17. In our study, all cases were treated with surfactants at the initiation of mechanical ventilation, and there was no difference in the dosage of surfactant between two groups. In a study investigating the optimal PEEP selection for non-invasive ventilation after extubation in extremely preterm infants, researchers found that higher PEEP (9–11 cmH2O) reduced the reintubation rate within a week post-extubation without increasing pneumothorax and gastrointestinal perforation4.

The above pathophysiological mechanisms indicated that higher-PEEP group would be expected to demonstrate a reduced ΔP for a given VT compared to the control group. But we noticed that there was no significant difference in ΔP between the two groups, which might be related to the clinicians’ practice. Our target VT range was 4–6 cmH2O rather than a specific fixed value. As was well known, VT was directly related to ΔP. In a trial of preterm lambs, while maintaining a constant PEEP levels, the 30 cmH2O ΔP strategy resulted in quicker aeration but higher VT (> 8 ml/kg) and lung injury compared with ΔP 20 cmH2O group; and the single PEEP without tidal inflation group resulted in the least lung injury8. These findings suggested that high ΔP and the resulting large VT were the main causes of lung injury. In a large-scale clinical randomized trial of 3562 patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome, researchers frequently employed PEEP settings higher than 10 cmH2O, they found that ΔP was the ventilation variable that best stratified risk. Decreases in ΔP owing to changes in ventilator settings were strongly associated with increased survival, and reducing ΔP and increasing PEEP was associated with increased survival18. Some scholars also demonstrated that limiting ΔP and mechanical power required reducing VT and increasing PEEP, decreasing lung injury1. In an experimental animal study, researchers found that the gene expression of markers of early lung injury were inversely related to magnitude of PEEP, being lowest in the higher PEEP group (20 cmH2O dynamic); PEEP levels had no impact on lung injury in the dependent lung19. Although our higher-PEEP group did not demonstrate a significant reduction in ΔP compared to the control group, the mere increase in PEEP levels without a corresponding rise in ΔP did not exacerbate lung injury.

We also observed no significant differences in the comparison of clinical complications between the two groups, suggesting that higher PEEP maintained favorable FRC without compromising hemodynamics. We observed that higher-PEEP group exhibited fewer cases of moderate to severe pulmonary hypertension, though this difference was not statistically significant. There was no case of pulmonary hemorrhage in higher-PEEP group, but that occurred in one infant in the control. Encouragingly, no IVH occurred in higher-PEEP group, while the control had three cases of Grade I-II IVH, though this difference also lacked statistical significance.

Notably, in the control group, three infants were switched to HFOV by the attending physicians for safety reasons due to disease progression when their MAP already exceeded 15 cmH2O. Their durations of conventional mechanical ventilation were 16, 18, and 22 h, respectively. After transitioning to HFOV, both MAP and FiO2 were increased compared to previous settings and maintained at higher parameters beyond 24 h. As a standard practice, the MAP during HFOV was typically higher than in conventional ventilation, yielding superior clinical outcomes. Some scholars argued that the primary advantage of high-frequency ventilation laid in their ability to maintain a higher MAP, which promoted alveolar recruitment and stabilization throughout the respiratory cycle20. Similarly, in conventional ventilation, increasing PEEP could achieve comparable effects by reopening collapsed alveoli, mainly the poorly-aerated alveoli, left lung and gravity-dependent lung regions8. Despite reclassifying their data under the control group for analysis, this adjustment inherently narrowed the observed differences when compared with higher-PEEP group.

In summary, we have observed the safety and efficacy of 8.5–11 cmH2O PEEP levels in treating NRDS of late preterm and term newborn infants, with no increased incidence of the complications, providing evidence for future clinical practice. Higher-PEEP ventilation might emerge as a novel therapeutic strategy, mitigating ventilator-associated complications. Further researches were needed to establish evidence-based PEEP guidelines for the vulnerable population.

As the limitations of our study: (1) this was not a multi-center study, and the sample size was small, thus limiting the statistical power of our results; (2) the management of NRDS and the adjustment of ventilator parameters were closely influenced by the individual experience of local physicians; (3) no bronchoalveolar lavage studies were performed, precluding direct measurement of alveolar injury; (4) no genetic research data related to pulmonary injury and metabolism were available. As a pilot study, our next step will be to enlarge the study cohort and further investigate the genomics and metabolomics in higher-PEEP group.

Methods

Study design and participants

This study was a prospective, randomized controlled trial conducted in level III NICU of The Affiliated Suqian Hospital of Xuzhou Medical University from April 2025 to August 2025.

When these late preterm and term newborn infants developed respiratory distress within 6 to 12 h after birth, we performed both radiographic and lung ultrasound examinations on them in the NICU. The inclusion criteria were: (1) NRDS diagnosed by chest radiography or lung ultrasound; (2) at gestation age of 34+ 0 to 39+ 6 weeks; (3) requirement of mechanical ventilation: ① requiring FiO2 > 0.4 on non-invasive ventilation; ② persistent or worsening respiratory acidosis, typically defined as: pH < 7.20–7.25, PaCO2 > 60–65 mmHg (8.0–8.7 kPa); ③ increased work of breathing with significant symptoms of respiratory distress despite optimal non-invasive support; ④ recurrent apnea or respiratory pauses requiring ventilation with bag and mask. The exclusion criteria were: (1) chromosomal abnormalities; (2) congenital malformations affecting respiratory function; (3) history of severe adverse perinatal conditions, such as intrauterine distress, severe birth asphyxia, severe intrauterine infection, congenital pneumonia, and meconium aspiration syndrome (gestational diabetes mellitus excluded); (4) pneumothorax occurring prior to mechanical ventilation; (5) missing of guardian informed consent.

Intervention protocols

Control group

Initial ventilation mode and parameter settings: synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation (SIMV) + pressure support ventilation (PSV); FiO2: adjusted dynamically to maintain target arterial oxygen saturation (SaO2) between 91% and 95% (measured via right wrist probe); inspiratory time: 0.35–0.4 s; respiratory rate: 30–50 breaths/min; VT: 4.0–6.0 ml/kg; PIP: adjusted to maintain VT and target arterial carbon dioxide partial pressure (PaCO2) between 35 and 55 mmHg; PEEP: adjustable within 6–8 cmH2O for ≥ 24 h, after 24 h, PEEP could be adjusted within the assigned range or reduced at clinician discretion. Clinicians were aware of group assignments and aimed to wean ventilator early.

Extubation criteria: spontaneous breathing with adequate chest rise and resolved respiratory distress; normal arterial blood gas values; MAP ≤ 8 cmH2O; FiO2 ≤ 30%; respiratory rate ≤ 20 breaths/min.

Post-extubation support: nasal continuous positive airway pressure (PEEP ≤ 6 cmH2O), hood oxygen therapy (FiO2 ≤ 30%), or room air.

Reintubation: Performed if extubation failed (criteria identical to initial intubation indications), with PEEP adjusted based on clinical status.

Higher-PEEP group

Initial ventilation mode and parameter settings: SIMV + PSV; FiO2: adjusted dynamically to maintain target SaO2 between 91% and 95% (measured via right wrist probe); inspiratory time: 0.35–0.4 s; respiratory rate: 30–50 breaths/min; VT: 4.0–6.0 ml/kg; PIP: adjusted to maintain VT and target PaCO2 between 35 and 55 mmHg; PEEP: initial setting at 7 cmH2O, gradually increased to 9 cmH2O over 2 h (to avoid rapid lung inflation injury), adjusted between 8.5 and 11 cmH2O according to lung inflation confirmed via radiographic examination, clinician-adjusted, and maintained for ≥ 24 h; after 24 h, PEEP could be adjusted within the assigned range or reduced at clinician discretion. Clinicians were aware of group assignments and aimed to wean ventilator early.

Extubation criteria: identical to the control group.

Post-Extubation support: identical to the control group.

Reintubation: identical to the control group.

Surfactant application strategy

For NRDS requiring mechanical ventilation, the surfactant was administered immediately after endotracheal intubation. The surfactant in this study was calf pulmonary surfactant (a bovine surfactant product marketed as Kelisu in China). The initial dose was administered at a range of 70 to 100 mg/kg. If there was no significant improvement after the initial dose or if the condition worsened again after initial improvement, a reassessment was conducted. Based on clinical manifestations and lung imaging, if the NRDS was still judged to be severe, repeat surfactant administration was considered, with a dosage equal to the initial dose. The interval between doses was generally 6 to 12 h.

Equipment and adjuncts

All endotracheal intubations were performed via the oral route. The invasive ventilators were Dräger V500 or V300 (Drägerwerk AG & Co. KGaA, Lübeck, Germany). The non-invasive ventilators were Comen NV8 (Shenzhen Comen Medical Instruments Co., Ltd., Guangdong Province, China), and the size of nasal prong was determined by infant weight. Routine phenobarbital sodium was treated during intubation, and additional phenobarbital sodium or midazolam was used for patient-ventilator asynchrony. No caffeine citrate was used. The administration of repeated dose of surfactant was based on persistent clinical, radiological, and symptomatic evidence of NRDS.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the duration of mechanical ventilation (hour). We also collected the data of OI at 24 h after birth during the clinical climax, calculated as (MAP×FiO2 × 100)/PaO2, and cumulative dosage of surfactant (mg/kg). Furthermore, the other ventilation parameters, non-invasive ventilation duration, oxygen hood therapy duration, clinical complications, and length of hospitalization were collected and analyzed.

Experimental deviation

In the control group, three infants were switched to HFOV by the attending physicians for safety reasons due to disease progression when their MAP already exceeded 15 cmH2O. Their durations of conventional mechanical ventilation were 16, 18, and 22 h, respectively. After transitioning to HFOV, both MAP and FiO2 were increased compared to previous settings and maintained at higher parameters beyond 24 h; and the dose of surfactant they received showed no significant difference compared to other infants whose MAP exceeded 15 cmH2O.

Data analysis

All analyses were performed based on the intention-to-treat principle, with preterm infants retained in their originally assigned groups for all outcome assessments. Clinical data from both groups were analyzed according to case report forms. Collected data underwent completeness checks to address any gaps, followed by dual independent entry into SPSS 26 software. Post-entry, all datasets were subjected to logical validation. Continuous variables were analyzed using parametric tests (t-test) or non-parametric tests (Wilcoxon rank-sum test), while categorical variables were assessed via Pearson’s chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests. These methods were employed to compare intergroup differences, therapeutic efficacy, and safety outcomes. The ethics committee of The Affiliated Suqian Hospital of Xuzhou Medical University conducted independent safety analyses for preterm infants, and all statistical evaluations were prospectively planned prior to data interrogation. This trial was registered with the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry on 20/08/2025, number ChiCTR2500107900.

Data availability

The raw data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Kneyber, M. C. J. Driving pressure and mechanical power: the return of physiology in pediatric mechanical ventilation. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 22, 927–929. https://doi.org/10.1097/pcc.0000000000002829 (2021).

Schulzke, S. M. & Stoecklin, B. Von Ungern-Sternberg, B. Update on ventilatory management of extremely preterm infants—A neonatal intensive care unit perspective. Pediatr. Anesth. 32, 363–371. https://doi.org/10.1111/pan.14369 (2021).

Owen, L. S., Manley, B. J., Davis, P. G. & Doyle, L. W. The evolution of modern respiratory care for preterm infants. Lancet 389, 1649–1659. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(17)30312-4 (2017).

Kidman, A. M. et al. Higher versus lower nasal continuous positive airway pressure for extubation of extremely preterm infants in Australia (ECLAT): a multicentre, randomised, superiority trial. Lancet Child. Adolesc. Health. 7, 844–851. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(23)00235-3 (2023).

Sweet, D. G. et al. European consensus guidelines on the management of respiratory distress syndrome: 2022 update. Neonatology 120, 3–23. https://doi.org/10.1159/000528914 (2023).

Liu, J., Liu, G., Wu, H. & Li, Z. Efficacy study of pulmonary surfactant combined with assisted ventilation for acute respiratory distress syndrome management of term neonates. Experimental Therapeutic Med. 14, 2608–2612. https://doi.org/10.3892/etm.2017.4839 (2017).

Ninan, K. et al. The proportions of term or late preterm births after exposure to early antenatal corticosteroids, and outcomes: systematic review and meta-analysis of 1.6 million infants. Bmj https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2023-076035 (2023).

Tingay, D. G. et al. Inflating pressure and not expiratory pressure initiates lung injury at birth in preterm lambs. Am. J. Respir. Crit Care Med. 208, 589–599. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.202301-0104OC (2023).

Madar, J. et al. European resuscitation Council guidelines 2021: newborn resuscitation and support of transition of infants at birth. Resuscitation 161, 291–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.02.014 (2021).

Williams, E. E. & Greenough, A. Lung protection during mechanical ventilation in the premature infant. Clin. Perinatol. 48, 869–880. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clp.2021.08.006 (2021).

Lemyre, B. et al. Nasal intermittent positive pressure ventilation (NIPPV) versus nasal continuous positive airway pressure (NCPAP) for preterm neonates after extubation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.. 2023 https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003212.pub4 (2023).

Tingay, D. G. et al. Gradual aeration at birth is more lung protective than a sustained inflation in preterm lambs. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 200, 608–616. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201807-1397OC (2019).

Kanaan, Z. et al. Feasibility of combining two individualized lung recruitment maneuvers at birth for very low gestational age infants: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Pediatr. 20 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-020-02055-3 (2020).

Mulrooney, N. et al. Surfactant and physiologic responses of preterm lambs to continuous positive airway pressure. Am. J. Respir. Crit Care Med. 171, 488–493. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200406-774OC (2005).

Zhu, X. et al. Noninvasive High-Frequency oscillatory ventilation vs nasal continuous positive airway pressure vs nasal intermittent positive pressure ventilation as postextubation support for preterm neonates in China. JAMA Pediatr. 176 https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.0710 (2022).

Donda, K., Babu, S., Rastogi, D. & Rastogi, S. Risk factors for pneumothorax and its association with ventilation in neonates. Am. J. Perinatol. 41, e1531–e1538. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0043-1768070 (2023).

Ramaswamy, V. V., Abiramalatha, T., Bandyopadhyay, T., Boyle, E. & Roehr, C. C. Surfactant therapy in late preterm and term neonates with respiratory distress syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed 107, 393–397. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2021-322890 (2021).

Amato, M. B. P. et al. Driving pressure and survival in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 372, 747–755. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1410639 (2015).

Tingay, D. G. et al. Dynamic positive end-expiratory pressure strategies using time and pressure recruitment at birth reduce early expression of lung injury in preterm lambs. Am J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol 323, L464–L472. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajplung.00047.2022 (2022).

Ackermann, B. W., Klotz, D., Hentschel, R., Thome, U. H. & van Kaam, A. H. High-frequency ventilation in preterm infants and neonates. Pediatr. Res. 93, 1810–1818. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-021-01639-8 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We sincerely appreciate the invaluable assistance provided by the hospital staff in conducting this study.

Funding

The study was supported by Suqian Sci&Tech Program (Grant no. Z2024102).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Each author has met the authorship requirements. Tao Ning and Huaiyu Yan conceptualized and designed the study. Tao Ning, Qiong Xue, Pingli Wang, Xudong Zhang, and Xiaoxue Shan participated in the clinical management of patients, collected the clinical data and analyzed the data. Qiong Xue Liuqing Yang, Mei Yuan, Chang Dong, and Song Liu carried out the formal analysis of the data, checked the data reliability and interpreted the data. Tao Ning drafted the initial manuscript. Suyue Zhu and Huaiyu Yan reviewed and revised the initial manuscript. Huaiyu Yan critically reviewed the last draft of the manuscript. All authors were involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content and final approval of the version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics declarations

The study adhered to ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and obtained approval from the ethics committee of The Affiliated Suqian Hospital of Xuzhou Medical University (2025-052-01). All parents provided written informed consent before the study began.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ning, T., Xue, Q., Wang, P. et al. Higher PEEP reduces duration of mechanical ventilation in neonatal respiratory distress syndrome of late preterm and term newborn infants. Sci Rep 15, 40501 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24335-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24335-7