Abstract

Pulmonary Non-tuberculous mycobacteria (pNTM) disease, often associated with underlying lung diseases, refers to a class of diseases in which humans are infected with Non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM), leading to pathological changes in the lungs. It is believed that the regulation of apoptosis by NTM contributes to their persistent infection. However, the roles of apoptosis - related genes in pNTM disease remain unclear. Here, we downloaded the expression profile of GSE205161 from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between pNTM patients and control samples. We then intersected the DEGs with apoptosis - related genes (ARGs). As a result, we obtained fifteen apoptosis - related differentially expressed genes (ARDEGs). Through GO and KEGG pathway analyses, we found that fifteen ARDEGs were primarily enriched in the TNF - mediated signaling pathway, cytokine receptor binding, regulation of JNK cascade, and TNF receptor superfamily binding. Additionally, we identified four key genes (ACTA2, CD180, PIK3R1, TPM4) as biomarkers with moderate potential for diagnosing pNTM disease using the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. By analyzing the RNA regulation networks, we found that arsenic trioxide and doxorubicin could potentially target CASP9, PIK3R1, ACTA2, and BECN1 for treating pNTM disease. The present study provides a basis for investigating biomarkers and potential therapeutic targets for pNTM disease in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) are opportunistic pathogens that can be found in various environments, including soil and tap water1,2. At present, there are over 200 reported NTM strains/subspecies in clinical practice, including Mycobacterium intracellulare, Mycobacterium kansasii, Mycobacterium avium, Mycobacterium abscessus complex, Mycobacterium gordonae, Mycobacterium fortuitum, Mycobacterium cosmeticum, Mycobacterium peregrinum, Mycobacterium simiae, etc. However, a single positive NTM culture alone is not enough to diagnose NTM disease. To make an accurate diagnosis, the guideline recommends considering three factors: multiple isolations of the same bacterium, corresponding clinical symptoms, and radiographic evidence3. NTM disease is a chronic infectious condition that can affect multiple organs in humans, but it primarily targets lung tissue, accounting for approximately 70% to 80% of cases4. Pulmonary Non-tuberculous mycobacteria (pNTM) disease, often present alongside underlying lung diseases, refers to a group of disorders where NTM infects humans and causes pathological changes in the lungs. Since pNTM disease exhibits similar clinical characteristics to tuberculosis and has a high resistance rate to anti-tuberculosis drugs, distinguishing between the two can be challenging5. Hence, the development of new diagnostic methods is crucial for accurately identifying and differentiating pNTM disease.

Apoptosis plays a critical role in maintaining the immune defense system. It not only ensures the homeostasis of the immune system, but also significantly impacts the progression and severity of diseases. Host cells employ apoptosis as a mechanism to protect against pathogens such as bacteria and viruses6. The relationship among pathogens, hosts, and apoptosis is intricate7. Danelishvili et al. made an important discovery regarding the impact of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M. tuberculosis) on cell apoptosis. Highly toxic M. tuberculosis strains may inhibit cell apoptosis to promote their own growth and reproduction within cells, while weakly virulent strains induce significant host cell apoptosis8. They also observed various changes in the expression of pro-apoptotic genes and inhibitors of apoptosis in infected alveolar epithelial cells and macrophages8. These findings suggest that mycobacteria employ different survival strategies depending on the host organism, and that apoptosis plays a crucial role in determining the prognosis of mycobacterial diseases. However, the specific apoptotic genes involved in pNTM disease and their impact on the disease remain unknown.

Next-generation sequencing technology and bioinformatics analysis have been extensively used to investigate differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and their gene networks in pNTM disease. These networks provide comprehensive insights into the regulation of mRNA and the evaluation of drug targets for pNTM disease. It has been observed that NTM can cause persistent infection in patients, but the immune system is unable to eradicate it promptly. One of the main features of the relationship between NTM infection and apoptosis is that it is bidirectional and regulatory9,10. NTM avoids immune clearance by suppressing host cell apoptosis, thereby enhancing its intracellular survival. Simultaneously, NTM has the capacity to induce apoptosis, either as a host defense mechanism or to cause tissue damage. This intricate interaction involves cross-regulation between autophagy and apoptosis, ultimately influencing infection progression and the immune response.Therefore, conducting in-depth bioinformatics analysis to explore apoptosis-related differentially expressed genes (ARDEGs) can assist in the identification of potential diagnostic biomarkers and the exploration of drug targets for pNTM disease. Additionally, a study by Prieto MD et al. provided data on whole - blood gene expression in pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial infection11. The data included 12 patients who progressed to pNTM disease (detected with 7 strains of M. avium complex and 5 strains of M. abscessus complex) and 30 patients who did not progress to pNTM disease (detected with 15 strains of M. avium complex, 7 strains of M. abscessus complex, 3 strains of M. gordonae, 2 strains of M. fortuitum, 1 strain of M. cosmeticum, 1 strain of M. peregrinum, and 1 strain of M. simiae). Those data serve as a valuable resource for further investigation of pNTM disease.

In this study, we utilized the expression profile dataset GSE205161 of cystic fibrosis patients from the GEO database. We extracted apoptosis - related genes (ARGs) from the GeneCards database. Then, we intersected these ARGs with the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) to identify ARDEGs in patients with pNTM disease. Subsequently, we performed Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analyses of the ARDEGs. Furthermore, we investigated various molecular mechanisms, including the protein-protein interaction (PPI) network, mRNA regulatory networks of ARDEGs, ARDEGs-drugs interaction network, and immune infiltration analysis. Ultimately, we pinpointed pivotal diagnostic biomarkers and drug targets for pNTM disease, offering a robust experimental foundation for future research.

Results

Identification of apoptosis-related genes in pNTM disease

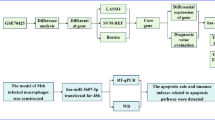

Figure 1 illustrates the identification process of apoptosis-related biomarkers in pNTM disease. We analyzed the expression profiles from GSE205161 to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Subsequently, we intersected these DEGs with apoptosis - related genes (ARGs) and obtained 15 ARDEGs. We then performed GO and KEGG pathway analyses. After that, we constructed protein - protein interaction (PPI) and mRNA regulation networks, conducted immune infiltration analysis using CIBERSORT, and carried out differential expression analysis. Finally, four hub genes (ACTA2, CD180, PIK3R1, TPM4) were identified as potential diagnostic biomarkers for pNTM disease.

Normalization and differential analysis of the NTM dataset

The NTM disease dataset GSE205161 was first normalized using the limma package (This study was exclusively based on the single-batch dataset GSE205161, with no cross-batch integration scenario involved). A total of 42 samples were obtained from the GSE205161 dataset, comprising 30 control samples and 12 pNTM disease group samples. Figure 2A-B demonstrate that after normalizing the expression profile data of pNTM disease, the normalization among samples was significantly reduced and the expression profiles of the GSE205161 dataset became more consistent. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of the expression matrix of the GSE205161 dataset was then conducted to validate the effectiveness of normalization, as shown in Fig. 2C-D.

The limma package was utilized to normalize the data of the pNTM disease patients and control group in order to analyze the differences in gene expression between the two groups. Using the criteria of |logFC| > 0 and P-value < 0.05, we obtained 799 DEGs from a total of 17,186 genes in the GSE205161 dataset. Among these DEGs, there were 357 genes with high expression and 442 genes with low expression in the pNTM disease group compared to the control group, shown in the volcano plot (Fig. 2E). Furthermore, we conducted a venn diagram analysis to identify the overlap between the DEGs and ARGs in the GSE205161 dataset. This analysis identified 15 ARDEGs, as shown in Fig. 2F; Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7. The differential analysis results of these 15 ARDEGs were visualized using a heatmap (Fig. 2G).

Normalization and differential analysis of the NTM dataset. A-B. Boxplot of expression profiles of GSE205161 dataset before normalization (A) and after normalization (B). C-D. PCA plot of GSE205161 before normalization treatment (C) and after normalization treatment (D). (E). Volcano plot of DEGs analysis in pNTM disease group relative to control group of GSE205161 dataset. (F). Venn diagram of obtaining 15 ARDEGs from ARGs and DEGs in GSE205161 dataset. (G). Heatmap of differential analysis of 15 ARDEGs in GSE205161 dataset. PCA: Principal Component Analysis; pNTM disease: pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacteria disease; DEGs: Differentially Expressed Genes; ARGs: apoptosis related genes; ARDEGs: apoptosis related differentially expressed genes.

GO and KEGG analysis of ARDEGs in pNTM disease

Function enrichment analysis was conducted to examine the relationship between pNTM disease and biological pathways, such as molecular function (MF), cellular component (CC), and biological process (BP) with screening criteria of adjusted P - value < 0.05 and FDR value (q-value) < 0.05, which indicated statistical significance. The results, displayed in bubble plots (Fig. 3A; Table 3), demonstrated that the 15 ARDEGs were primarily enriched in GO-MF items such as death receptor binding, tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily binding, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase binding, cytokine receptor binding, and the apoptotic process regulated by cysteine - type endopeptidase inhibitor activity. Furthermore, they were enriched in GO-CC items such as phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase complex, actin filament bundle, stress fiber, actomyosin, and contractile actin filament bundle. Additionally, the 15 ARDEGs were enriched in GO-BP items such as intrinsic apoptotic signaling pathway, extrinsic apoptotic signaling pathway, regulation of apoptotic signaling pathway, TNF-mediated signaling pathway, and regulation of JNK cascade. Network diagrams depicting the pathways of MF, CC, and BP in the GO enrichment analysis were also displayed (Fig. 3B-D).

Moreover, a KEGG enrichment pathway analysis was performed on the 15 ARDEGs (Table 4). The bar graphs (Fig. 3E) showed that the 15 ARDEGs were significantly enriched in Epstein-Barr virus infection, apoptosis, small cell lung cancer, apoptosis-multiple species, and colorectal cancer. The network graph (Fig. 3F) displayed hub genes, such as TRAF1, PI3KR1, and CASP9, which were involved in small cell lung cancer based on the KEGG pathways. These findings suggested that persistent infection in pNTM disease may be associated with the development of lung cancer and warrant further investigation.

GO and KEGG analysis of ARDEGs in pNTM disease. A-D. Bubble plot (A) and circular network diagram (B-D) of GO functional enrichment analysis of ARDEG. E-F. Bar chart (E) and network diagram (F) of KEGG enrichment analysis of ARDEGs. All pathway maps in E-F were adapted from the KEGG PATHWAY database12 (https://www.kegg.jp/kegg/kegg1.html).

GSEA results in pNTM disease dataset

To gain insights into the impact of gene expression levels on pNTM disease, an analysis of all genes and biological processes involved in the GSE205161 dataset was conducted using GSEA. The results, presented in Table 5; Fig. 4, identified the top 5 pathways of DEGs in the GSE205161 dataset. These pathways were visually represented in a ridge plot (Fig. 4A) and predominantly enriched in the IFNA response (Fig. 4B), IFNB1 targets (Fig. 4C), response to LPS with mechanical ventilation (Fig. 4D), STAT3 targets up (Fig. 4E), and STAT5A targets group1 (Fig. 4F) in the pNTM disease group as compared to the control group.

GSVA results of DEGs between disease and control group

To investigate the disparity of hallmark gene sets between the pNTM disease patients and control group, we conducted Gene Set Variation Analysis (GSVA) using the GSE205161 dataset (Fig. 5; Table 6). As shown in Fig. 5, five hallmark gene sets, namely fatty acid metabolism, oxidative phosphorylation, DNA repair, hedgehog signaling, and TGF beta signaling, exhibit significant differences between the two groups (adjusted P - value < 0.05). Notably, the enrichment scores of the hallmark pathways of hedgehog signaling and TGF beta signaling in the pNTM disease group was higher than that of the control group (P.adj < 0.05). Conversely, the control group showed higher enrichment scores for the hallmark pathways of DNA repair, fatty acid metabolism, and oxidative phosphorylation compared to those in the pNTM disease (adjusted P - value < 0.05). Furthermore, the specific results were effectively visualized through a heatmap in Fig. 5A, while Fig. 5B utilized a comparison plot with the Mann-Whitney U test to present the differences between the two groups.

PPI network and mRNA regulation networks of ARDEGs

The STRING database was used to conduct a PPI network analysis for fifteen ARDEGs within the pNTM disease dataset. After we selecting ARDEGs that had connections with other nodes, a total of 10 hub genes (ACTA2, BCL2L11, BECN1, CASP9, CD180, NAIP, PIK3R1, RIPK1, TPM4, TRAF1) were obtained, and a PPI network was constructed (Fig. 6A).

The miRDB database was used to predict target microRNAs (miRNAs) for the 10 hub genes, and the resulting mRNA-miRNA interaction network was visualized using Cytoscape software (Fig. 6B). In this network, sky blue circular blocks represented mRNAs, while green circular blocks represented miRNAs. Analysis of Fig. 6B and Supplementary table S1 revealed that 5 hub genes (ACTA2, BCL2L11, BECN1, PIK3R1, TPM4) and 109 miRNA molecules constituted a total of 119 mRNA-miRNA regulation networks.

The ENCORI database was utilized to predict interactions between the 10 hub genes and RNA binding proteins (RBPs). Only interaction pairs of mRNA-RBP that met specific criteria (clusterNum > 3, clipExpNum > 3) were retained, After this screening step, the resulting mRNA-RBP regulation network was visualized using Cytoscape software (Fig. 6C and Supplementary table S2). In this network, a total of 8 hub genes (ACTA2, BCL2L11, BECN1, CASP9, PIK3R1, RIPK1, TPM4, TRAF1) and 48 RBP molecules constituted 126 mRNA-RBP regulation networks.

Transcription factors (TFs) that bind to the hub genes were identified using the CHIPBase (version 2.0) and hTFtarget databases. The data obtained from these databases was intersected with the 10 hub genes, resulting in the identification of 9 hub genes (ACTA2, BCL2L11, BECN1, CASP9, CD180, PIK3R1, RIPK1, TPM4, TRAF1) that interacted with 122 TFs (Fig. 6D and table S3). In this network, sky blue circular blocks represented mRNAs, while purple circular blocks represented TFs.

Finally, the CTD database was used to identify potential molecular compounds associated with the 10 hub genes. Our results indicated that 66 potential molecular compounds interacted with 9 hub genes (ACTA2, BCL2L11, BECN1, CASP9, NAIP, PIK3R1, RIPK1, TPM4, TRAF1). Specific mRNA-drug interactions were established and shown in Fig. 6E and Supplementary Table S4. In this network, sky blue circular blocks represented mRNAs, while pink circular blocks represented the molecular compounds.

Differential expression analysis of ARDEGs

To thoroughly investigate the differential expression of hub genes in pNTM disease and the control group, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was conducted. This test was used to compare the expression differences of 15 ARDEGs in the GSE205161 dataset, as depicted in Fig. 7A. In total, 4 key genes (ACTA2, CD180, PIK3R1, and TPM4) exhibited statistical significance between the two groups. Next, we evaluated the diagnostic performance of 4 key genes in pNTM disease using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. As illustrated in Fig. 7B-E, the area under the curve (AUC) for the expression of ACTA2, CD180, PIK3R1, and TPM4 was calculated to be 0.758, 0.713, 0.742, and 0.769, respectively. These findings suggest that the 4 key genes (ACTA2, CD180, PIK3R1, and TPM4) possess a certain level of accuracy in diagnosing pNTM disease.

Infiltration analysis of pNTM disease dataset (CIBERSORT)

The correlation between 22 immune cells and the expression profile dataset of GSE205161 in pNTM disease was determined using the CIBERSORT algorithm. Based on the results of immune infiltration analysis, We presented the infiltration results of the 20 immune cells, whose total infiltration abundance in each sample of the GSE205161 dataset was greater than 0, in the form of a bar graph (Fig. 8A). Afterwards, we calculated the correlation between the abundance of these 20 types of immune cell infiltration in the GSE205161 dataset samples. Figure 8B showed that the logarithmic values of positive and negative correlation between the abundance of immune cell infiltration was approximately equal.

Additionally, we assessed the correlation between the abundance of these 20 types of immune cell infiltration and the expression levels of 10 hub genes (ACTA2, BCL2L11, BECN1, CASP9, CD180, NAIP, PIK3R1, RIPK1, TPM4, TRAF1) in the pNTM disease group samples of the GSE205161 dataset. As shown in Fig. 8C, there was a significant positive correlation between immune cells and certain hub genes, such as macrophages M1 and BECN1, NAIP, and TPM4; neutrophils and ACTA2, BCL2L11, BECN1, CASP9, NAIP, and RIPK1; activated CD4 memory T cells and ACTA2, BECN1, CASP9, and NAIP. Conversely, there was a significant negative correlation between immune cells and specific hub genes, such as macrophages M0 and PIK3R1, TRAF1; activated NK cells and ACTA2, BCL2L11, BECN1, CASP9, NAIP, and RIPK1; CD8 T cells and BCL2L11, BECN1, CASP9, and NAIP. Based on the varying expression levels of the four key genes examined in this study, We hypothesize that in pNTM disease, the host may exhibit an anti-inflammatory response by modulating some hub genes to stimulate M1-type monocyte macrophages and NK cells. Conversely, the regulation of neutrophils appears to have a comparatively minor anti-inflammatory impact.

Relationship of immune cell infiltration and hub genes in pNTM disease dataset. (A) Bar graph showing the immune infiltration results in GSE205161 dataset. (B) Display of immune cell infiltration abundance by heatmap analysis in GSE205161 dataset. (C) Display of relationship between hub genes and immune cells infiltration by dot plot.

Discussion

Currently, the major strains causing NTM disease include M.abscessus, M. kansasii, M. avium complex, M. malmoense, M. fortuitum, and M. turtles13. NTM disease is a chronic condition that can affect individuals of any age, although it is more common in older individuals. Most patients with NTM disease also suffer from underlying lung diseases such as cystic pulmonary fibrosis14, bronchiectasis15, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)16. An effective method of distinguishing NTM from M.tuberculosis is by identifying the type of NTM. However, when there is a clinical suspicion of NTM disease, laboratories often fail to culture the specific pathogen, which poses challenges for physicians. Therefore, there is an urgent need to find novel biomarkers that can aid in the diagnosis of NTM disease.

Apoptosis is a genetically regulated process that occurs in both pathological and physiological conditions17,18. It plays a crucial role in maintaining organismal homeostasis by eliminating damaged cells19,20. During infection with intracellular bacteria, host cells strive to limit the growth of the bacteria by inducing cell death pathways such as apoptosis. However, mycobacteria have evolved various strategies to disrupt apoptosis and thereby promote their own intracellular survival21. To investigate the impact of mycobacteria on apoptotic mechanisms, we utilized bioinformatics methods to examine the expression of apoptosis-related genes in patients with pNTM disease. We also analyzed the potential value of these genes and their complex interactions to provide a reference for identifying biomarkers related to NTM disease and developing treatment strategies.

In this study, we used the limma package to identify 799 DEGs with a screening criterion of p < 0.05, which was different from Miguel Dario Prieto et al.‘s study. The main reason was that limma package can detect more DEGs through linear models and empirical bayes methods, while DESeq2 uses a negative binomial distribution model to evaluate the data. When the false discovery rate is strictly controlled, the number of DEGs detected is usually smaller. Moreover we observed significant differences in four key genes (ACTA2, CD180, PIK3R1, TPM4) when comparing the pNTM disease group and control group. The ROC curves showed that the AUCs of these four genes were all above 0.7, suggesting their moderate diagnostic accuracy in diagnosing pNTM disease. CD180, originally detected in B cells, has been confirmed to have high similarity to TLRs and is classified as a member of the TLR family. Fan Z et al. reported that RP105 (CD180) regulated immune cells, leading to the release of inflammatory cytokines and activation of immune cells such as B cells, macrophages, and bone marrow monocytes22. Previous research has also shown that synthetic lipopeptide analogs of the 19 kDa lipoprotein from M. tuberculosis promoted CD180-mediated IL-6 and TNF secretion by macrophages23. Furthermore, Edwards K et al. reported that CD180 could serve as a therapeutic target and prognostic biomarker for various diseases24. In our study, we observed a decrease in CD180 expression in pNTM group by using the Wilcoxon signed - rank test, suggesting that NTM may exploit CD180 to inhibit cytokine secretion and maintain its sustained survival in vivo.

PIK3R1, which is an essential component of PI3K, encodes p85α25. Various signaling molecules need to interact with p85α subunits, which then leads to the activation of PI3K. Activated PI3K subsequently activates Akt to exert biological functions. FAN Z et al. reported that IL-1β mediated increase in miR-155 expression could inhibit PIK3R1 expression, thereby inhibiting PI3K/AKT expression and enhancing apoptosis26. Etna Marilena et al. found that M.tuberculosis significantly induced high expression of miR-15527. We speculate that M.tuberculosis may inhibit PIK3R1 expression by inducing miR-155 and this speculation needs further investigation. In our study, our results showed that PIK3R1 expression was more upregulated in pNTM group than that of control group, which may be related to the different virulence of NTM and M.tuberculosis.

TPM4 is a key member of the TPM family, responsible for maintaining cytoskeleton stability in non-muscle cells and facilitating contraction in smooth and skeletal muscle cells. Extensive research has been carried out on the role of TPM4 in the field of cancer, revealing that its overexpression promotes the proliferation of gastric cancer AGS cells and inhibits apoptosis28. Furthermore, TPM4 expression is positively correlated with immune infiltration by macrophages, NK cells, and neutrophils, implying its involvement not only in tumor progression but also in inflammatory responses.

ACTA2 is predominantly expressed in vascular smooth muscle cells, where it plays a pivotal role in promoting vascular motility and contraction. Mutations in the ACTA2 gene are known to cause various diffuse vasculopathies29. However, its involvement in infectious diseases has been scarcely reported. Therefore, further investigations are warranted to elucidate the precise function of ACTA2 in pNTM disease for a better understanding of the pathogenesis and potential therapeutic targets of pNTM disease.

GO and KEGG results indicated that 15 ARDEGs were primarily associated with tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily binding, cytokine receptor binding, and tumour necrosis factor-mediated signalling pathways. In the GSEA results, inflammatory signalling of IFNA and IFNB1 was found to be involved in pNTM disease. These pathways were associated with inflammatory reaction of M. intracellulare30,31. IFNA and IFNB1 could induce the expression of IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs) to restrict infection. Lande R et al. reported that M. tuberculosis-infected DC cells release Interferons α/β, which induce CXCL10 expression, subsequently recruiting effector cells to participate in tuberculosis granuloma formation32. Prabhakar S et al. found that type I interferon could serve as a prognostic marker for chemotherapy in monitoring M. tuberculosis patients33. In the GSVA results, we observed a higher enrichment score for TGF-β signalling in the pNTM disease group, which was consistent with the existing literature that the host-produced TGF-β inhibits M. intracellular survival through the ERK1/2 pathway in pNTM disease34, moreover, we also observed a lower enrichment score for fatty acid metabolism and oxidative phosphorylation in the pNTM disease group. It was hypothesized that NTM infection could potentially reprogram the host’s energy metabolism, leading to metabolic remodeling. Previous studies showed that NTM infection could significantly alter the metabolic status of host cells, especially immune cells such as macrophages, including the regulation of multiple energy metabolism processes such as fatty acid metabolism, oxidative phosphorylation, and glycolysis35,36. This process not only impacts the efficiency of pathogen clearance but also has a strong correlation with the intensity of the immune response and apoptosis.

As is widely recognized, miRNAs play critical roles in the regulation of mRNA. However, the connections between hub genes and miRNAs in pNTM disease remain unclear. Hence, it is essential to construct regulatory networks for miRNA-mRNA interactions in order to investigate potential molecular mechanisms. Our findings revealed that hsa-miR-222-3P and hsa-miR-221-3p were targeted by PIK3R1 and BCL2L11, respectively. Additionally, hsa-miR-20a/b-5p, hsa-miR-93-5p, hsa-miR216b-5p, hsa-miR-17-5p, hsa-miR-519d-3p, and hsa-miR-106a/b-5p were connected to BECN1 and BCL2L11, indicating their potential significance in pNTM disease. Literature reported that miRNA-221 could target PIK3R1 to hinder vasculogenesis in vivo in a zebrafish model37 and miRNA-221/222-BCL2L11 axis played a vital role in the regulation of apoptosis38,39. Aguilo N et al. discovered that apoptosis induced by mycobacterium was inhibited by transfection with BCL2L11 (BIM) siRNA40. More recently, Luo S et al. found that BCL2L11 recruited BECN1 to microtubules, inhibiting autophagy by connecting DYNLL1 and BECN141. These findings suggest that BCL2L11 may have an important role in regulating apoptosis and autophagy. In the results of mRNA-drug interactions, we found several molecular compounds or drugs, such as arsenic trioxide, and doxorubicin, targeting CASP9, PIK3R1, ACTA2, and BECN1 in pNTM disease. Arsenic trioxide is clinically used in the treatment of glioma42 and lung cancer43. We require experiments to further assess the therapeutic efficacy of arsenic trioxide in treating pNTM disease. Doxorubicin has been demonstrated to be an inhibitor of Mtb DnaG primase which promoted bacterial DNA replication44,45. However, the evaluation of doxorubicin in pNTM disease requires further experimental verification. Furthermore, the analysis of immune cell infiltration and apoptosis gene expression uncovered the important role of apoptosis in NTM disease. In patients with pNTM disease, we observed that: (1) upregulated expression of the anti-apoptotic gene TPM4 was positively correlated with M1 macrophage infiltration; (2) increased PI3KR1 expression showed a negative correlation with M0 macrophage infiltration; and (3) downregulated expression of the pro-apoptotic gene ACTA2 was positively associated with neutrophils and CD4 + T cell infiltration but negatively correlated with NK cell infiltration. These findings collectively suggest that dysregulation of these apoptosis-related genes may facilitate NTM immune evasion.

There are certain limitations in this study. Firstly, the relatively small sample size in pNTM disease may have influenced the results, and the expression level of ARDEGs needs to be further validated using RT-PCR; secondly, NTM is an opportunistic pathogen, cases of NTM disease are relatively rare in clinical practice. Even if NTM is cultured positive in clinical laboratory, it may still be a colonizing bacterium in the respiratory tract, which is of little significance. Moreover, we do not analyze our data in comparison with other related studies because these datasets have differences in chip platforms, species types, and other aspects, which may present challenges for direct comparative analysis.Nevertheless, the present study offers a direction for investigating biomarkers and potential therapeutic targets for pNTM disease in the future.

In conclusion, We have successfully identified four key genes (ACTA2, CD180, PIK3R1, TPM4) that show moderate potential to serve as biomarkers for the diagnosis of the pNTM disease. Additionally, CASP9, PIK3R1, ACTA2, and BECN1 may serve as valuable therapeutic targets for the treatment of pNTM disease. This study significantly contributes to our understanding of the significance of diagnosing and treating pNTM disease.

Materials and methods

Data download

The dataset GSE20516111, which contains the expression profiles of cystic fibrosis (CF) patients, was obtained from Homo sapiens and downloaded from the GEO database46. This was achieved using the GEOquery R package47. As shown in Table 1, the GSE205161 dataset consists of high-throughput sequencing expression profiles of human whole blood samples, with some individuals exhibiting NTM infection while others serve as the control group without NTM disease. The dataset includes a total of 42 samples, including 12 patients with pNTM disease and 30 matched controls. The data platform used for this study was the GPL24676 Illumina NovaSeq 6000 (Homo sapiens).

The GPL platform - specific annotation files were used to annotate the probe names in the datasets. The subsequent analysis integrated the expression profile data of 12 pNTM patient samples, along with their corresponding 30 matched controls from the GSE205161 dataset.

The GeneCards database48 (https://www.GeneCards.org/) provides comprehensive information about human genes, including ARGs. In our study, we used the term “apoptosis” as the search keyword and only included ARGs with protein -coding designation and a Relevance score > 10. A total of 179 ARGs were identified from the GeneCards database. Furthermore, Using ‘apoptosis’ as the search keyword, we obtained BROCKE_APOPTOSIS_REVERSED_BY_IL6 and BIOCARTA_PTEN_PATHWAY from the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB)49. In the reference gene set, there were 162 ARGs. After merging and removing duplicates, a total of 325 ARGs were identified. Detailed information can be found in Table 2.

DEGs and ARDEGs identification of pNTM disease

We initially normalized the dataset GSE205161 using the limma package50 for further analysis.After that, we identified DEGs based on the screening criteria of | logFC | >0 and P-value < 0.05 within various groups in the GSE205161 dataset. DEGs with logFC < 0 and P-value < 0.05 were categorized as down-regulated genes, while DEGs with logFC > 0 and P-value < 0.05 were classified as up-regulated genes.

To obtain ARDEGs associated with pNTM disease, Our initial step was to intersect differentially expressed genes (DEGs) from the GSE205161 dataset and construct a Venn diagram. Then, the DEGs were intersected with ARGs to obtain ARDEGs. Finally, we used the ggplot2 R package to generate a volcano plot and the heatmap R package to create a heatmap, enabling visualization of the DEGs results.

ROC curve

The ROC curve51 is a comprehensive indicator that reflects the continuous variables of sensitivity and specificity, demonstrating the interrelationship between the two groups. A higher area under the ROC curve (AUC) value indicates superior diagnostic performance. An AUC value ranging from 0.5 to 0.7 suggests low accuracy, while a value of 0.7 to 0.9 denotes moderate accuracy. An AUC value above 0.9 indicates high accuracy. In this study, the ROC curve of ARDEGs in the pNTM disease dataset was plotted using the pROC package in R. The AUC was then calculated to evaluate the diagnostic efficacy of ARDEGs expression in pNTM disease.

GO and KEGG enrichment analysis of ARDEGs in pNTM disease

GO analysis is a widely used method for conducting comprehensive functional enrichment studies on a large scale, which encompasses biological process (BP), molecular function (MF), and cellular component (CC)52. KEGG, a database that houses extensive information on diseases, genomes, drugs, and biological pathways, was utilized53. The clusterprofiler R package was employed to conduct GO annotation analysis on the ARDEGs, adhering to a set of screening criteria, namely a P-adj < 0.05 and FDR value (q-value) < 0.05, with these values considered statistically significant54. The Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) method was employed for P-value correction to control the false discovery rate.

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)

GSEA is used to assess the tendency of gene distribution in a pre-defined gene set within a gene list ranked based on their correlation with the phenotype55. This enables the determination of the contribution of these genes to the phenotype. In this study, the genes from the GSE205161 dataset were divided into two categories based on positive and negative logFC values. Subsequently, the clusterProfiler package was employed to perform enrichment analysis on all DEGs within the positive and negative logFC values. The parameters used in this GSEA were as follows: 2023 seeds, 1000 counts, where each gene set contained a minimum of 10 genes and a maximum of 500 genes. The Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) method was utilized to correct the P-values. The c2.all.v2022.1.Hs.syndromes.gmt gene set, meeting the filtering criteria of P adj < 0.05 and FDR value (q-value) < 0.25, was retrieved from MsigDB.

Gene set variation analysis (GSVA)

GSVA is a non - parametric and unsupervised method. It is used to evaluate the enrichment of gene sets in the sample - derived transcriptome. This is achieved by transforming the matrix of gene expression levels across samples into gene sets across samples. The primary objective is to ascertain whether distinct biological pathways exhibit enrichment across the samples. In order to conduct GSVA analysis on the gene expression matrix of the GSE205161 dataset comparing the pNTM disease group and the control group, we searched MSigDB49 to acquire the “h.all.V7.4.Symbols.gmt” reference gene set. Using this reference gene set, we calculated the enriched pathways in the GSVA enrichment analysis results, which indicate the functional differences between the two groups. We considered an adjusted P - value < 0.05 to be statistically significant.

PPI networks of ARDEGs

PPI networks are formed by the interactions between individual proteins, which enable proteins to participate in various life processes such as gene expression regulation, biological signal transmission, and cell cycle regulation56. Understanding how proteins function in biological systems is crucial for comprehending protein-protein functional links and mechanisms of biological signal transduction. The STRING database serves as a valuable resource for studying protein interactions, encompassing both predicted and experimentally-validated protein interactions57. In this study, We constructed PPI networks using the STRING database, employing a minimum required interaction score of medium confidence (0.400) for the screened ARDEGs. Additionally, We employed Cytoscape (version 3.9.1)58 to visualize the PPI network model and subsequently identified these ARDEGs as key genes associated with pNTM disease.

Construction of the interaction network of ARDEGs-miRNA/RBP/TF and ARDEGs-drugs

We utilized the miRDB database59 to predict miRNAs interacting with hub genes. Subsequently, we constructed the ARDEGs - miRNA interaction network by filtering data with a target score > 80, which was obtained from the miRDB database.

The ENCORI database60 provides a diverse range of visual interfaces for exploring the targets of miRNAs. Within this database, the interactions of miRNA-ncRNA, RBP-mRNA, miRNA-mRNA, ncRNA-RNA, RNA-RNA, and RBP-ncRNA are based on degradome sequencing data (for plant) and CLIP-seq. Additionally, we used the ENCORI database to predict RBPs, with clusternum > 3 and clipexnum > 3 as the screening criteria, and mapped the mRNA-RBP interaction network.

The CHIPBase database (version 3.0) is composed of thousands of binding motif matrices and their associated binding sites, which have been identified from ChIP-seq data. This database has predicted millions of transcription factors (TFs) involved in gene regulation. We identified TFs binding to hub genes using the ChIPBase database (version 3.0)61 and the hTFtarget database62. The resulting data were visualized using the Cytoscape software.

Furthermore, we predicted small molecule compounds or drugs interacting with hub genes using the Comparative Toxicogenomics Database (CTD)63. The results of the mRNA-drugs interaction network have been displayed using the Cytoscape software.

Immune infiltration analysis (CIBERSORT)

CIBERSORT64 is an algorithm used for analyzing immune infiltration, which provides estimates of the composition and abundance of immune cells within mixed cell populations. This is accomplished through linear support vector regression for deconvoluting transcriptome expression matrices. In our study, we selected data with an immune cell enrichment score greater than zero using the CIBERSORT package. Additionally, we combined the data with the LM22 feature gene matrix65 to obtain specific results related to immune cell infiltration abundance in the pNTM disease dataset. To assess the correlation between various immune cells in samples from the pNTM disease dataset, we employed the Pearson algorithm and visualized the results using the ggplot2 R package. Furthermore, we calculated the correlation between immune cells and hub genes in different groups and presented these findings using the ggplot2 R package.

Statistical analysis

R software was employed for data analysis in this study. Continuous variables were reported as means ± standard deviations of the samples. The Wilcoxon rank sum test was employed to compare the differences between the two groups. Unless explicitly stated, we calculated the correlation coefficient for all results involving different molecules using Spearman’s correlation analysis. A significance level of P < 0.05 was adopted as the criterion for statistical significance.

Data availability

This study analyzed publicly accessible datasets, which include GeneCards (https://www.GeneCards.org/), MSigDB (https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/msigdb/), miRDB (https://mirdb.org/), ENCORI (https://starbase.sysu.edu.cn/), CHIPBase (https://rna.sysu.edu.cn/chipbase/), hTFtarget (http://bioinfo.life.hust.edu.cn/hTFtarget), Comparative Toxicogenomics Database (CTD, http://ctdbase.org/) and the GSE205161 datasets from Gene Expression Omnibus(GEO, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query). All the analyzed data were included in article and supplementary material.

References

Halstrom, S. et al. Environmental mycobacteria as a cause of human infection. Int. J. Mycobacteriol. 4, 81–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmyco.2015.03.002 (2015).

Davalos, A. F. et al. Identification of nontuberculous mycobacteria in drinking water in Cali, Colombia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 18 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168451 (2021).

Daley, C. L. et al. Winthrop, treatment of nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease: an official ATS/ERS/ESCMID/IDSA clinical practice guideline. Eur. Respir J. 56 https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00535-2020 (2020).

Sharma, S. K. et al. Epidemiology, diagnosis & treatment of non-tuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Indian J. Med. Res. 152 (3), 185–226. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_902_20 (2020).

Das, S. et al. Clinical presentations of nontuberculous mycobacteria as suspected and drug-resistant tuberculosis: experience from a tertiary care center in Eastern India. Int. J. Mycobacteriol. 11, 167–174. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijmy.ijmy_68_22 (2022).

Gao, J. et al. When ferroptosis Meets pathogenic infections. Trends Microbiol. 31, 468–479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tim.2022.11.006 (2023).

Scordo, J. M. et al. Alveolar epithelial cells in Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection: active players or innocent bystanders? J. Innate Immun. 8, 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1159/000439275 (2016).

Danelishvili, L. et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection causes different levels of apoptosis and necrosis in human macrophages and alveolar epithelial cells. Cell. Microbiol. 5, 649–660. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1462-5822.2003.00312.x (2003).

Sousa, S. et al. Nontuberculous mycobacteria persistence in a cell model mimicking alveolar macrophages. Microorganisms 7 https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms7050113 (2019).

Whang, J. et al. Mycobacterium abscessus glycopeptidolipids inhibit macrophage apoptosis and bacterial spreading by targeting mitochondrial Cyclophilin D. Cell. Death Dis. 8, e3012. https://doi.org/10.1038/cddis.2017.420 (2017).

Prieto, M. D. et al. Whole blood RNA-seq demonstrates an increased host immune response in individuals with cystic fibrosis who develop nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease. PLoS One. 17, e0278296. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0278296 (2022).

Kanehisa, M. et al. KEGG: biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucleic Acids Res. 53 (D1), D672–D677. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkae909 (2025).

Liu, Q. et al. Clinical characteristics of patients with non-tuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease: a seven-year follow-up study conducted in a certain tertiary hospital in Beijing. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 13, 1205225. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2023.1205225 (2023).

Martiniano, S. L. et al. Nontuberculous mycobacterial infections in cystic fibrosis. Clin. Chest Med. 43, 697–716. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccm.2022.06.010 (2022).

Aksamit, T. R. et al. Adult patients with bronchiectasis: a first look at the US bronchiectasis research registry. Chest 151, 982–992. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2016.10.055 (2017).

Yeh, J. J. et al. Nontuberculosis Mycobacterium disease is a risk factor for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a nationwide cohort study. Lung 192, 403–411. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00408-014-9574-9 (2014).

Lu, H. et al. Polystyrene microplastics mediate cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, and autophagy in the G2/M phase through ROS in grass carp kidney cells. Environ. Toxicol. 39, 1923–1935. https://doi.org/10.1002/tox.24068 (2024).

Hou, L. et al. A new insight into fluoride induces cardiotoxicity in chickens: involving the regulation of PERK/IRE1/ATF6 pathway and heat shock proteins. Toxicology 501, 153688. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tox.2023.153688 (2024).

Li, J. et al. Polystyrene microplastics mediate inflammatory responses in the chicken thymus by Nrf2/NF-κB pathway and trigger autophagy and apoptosis. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 100, 104136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.etap.2023.104136 (2023).

Roberts, J. Z. et al. The role of ubiquitination in apoptosis and necroptosis. Cell. Death Differ. 29, 272–284. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41418-021-00922-9 (2022).

Briken, V. et al. Living on the edge: Inhibition of host cell apoptosis by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Future Microbiol. 3, 415–422. https://doi.org/10.2217/17460913.3.4.415 (2008).

Fan, Z. et al. The potential role of RP105 in regulation of inflammation and osteoclastogenesis during inflammatory diseases. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 9, 713254. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2021.713254 (2021).

Schultz, T. E. et al. The N-terminal peptide moiety of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis 19 kDa lipoprotein harbors RP105-agonistic properties. J. Leukoc. Biol. 103, 311–319. https://doi.org/10.1002/JLB.2MA0517-190RR (2018).

Edwards, K. et al. The role of CD180 in hematological malignancies and inflammatory disorders. Mol. Med. 29, 97. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10020-023-00682-x (2023).

D’Ambrosio, C. et al. PIK3R1(W624R) is an actionable mutation in high grade serous ovarian carcinoma. Cells 9 https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9020442 (2020).

Fan, Z. et al. MiR-155 promotes interleukin-1beta-induced chondrocyte apoptosis and catabolic activity by targeting PIK3R1-mediated PI3K/Akt pathway. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 24, 8441–8451. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcmm.15388 (2020).

Etna, M. P. et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis-induced miR-155 subverts autophagy by targeting ATG3 in human dendritic cells. PLoS Pathog. 14, e1006790. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1006790 (2018).

Luo, Y. et al. Inhibitory effect of Crocin against gastric carcinoma via regulating TPM4 gene. Onco Targets Ther. 14, 111–122. https://doi.org/10.2147/OTT.S254167 (2021).

Yuan, S. M. Alpha-smooth muscle actin and ACTA2 gene expressions in vasculopathies. Braz J. Cardiovasc. Surg. 30, 644–649. https://doi.org/10.5935/1678-9741.20150081 (2015).

Ali, M. K. et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis rv0580c impedes the intracellular survival of Recombinant mycobacteria, manipulates the cytokines, and induces ER stress and apoptosis in host macrophages via NF-kappaB and p38/JNK signaling. Pathogens 10 https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens10020143 (2021).

Oh, S. M. et al. TNF-alpha-mediated ER stress causes elimination of Mycobacterium fortuitum reservoirs by macrophage apoptosis. FASEB J. 32, 3993–4003. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.201701407R (2018).

Lande, R. et al. IFN-alpha beta released by Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected human dendritic cells induces the expression of CXCL10: selective recruitment of NK and activated T cells. J. Immunol. 170, 1174–1182. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.170.3.1174 (2003).

Prabhakar, S. et al. Inhibition of response to alpha interferon by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 71, 2487–2497. https://doi.org/10.1128/IAI.71.5.2487-2497.2003 (2003).

L’Abbate, C. et al. TGF-beta-mediated sustained ERK1/2 activity promotes the Inhibition of intracellular growth of Mycobacterium avium in epithelioid cells surrogates. PLoS One. 6, e21465. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0021465 (2011).

Barisch, C. et al. Breaking fat! How mycobacteria and other intracellular pathogens manipulate host lipid droplets. Biochimie 141, 54–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biochi.2017.06.001 (2017).

Llibre, A. et al. Host immune-metabolic adaptations upon mycobacterial infections and associated co-morbidities. Front. Immunol. 12, 747387. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.747387 (2021).

Chang, T. Y. et al. MiRNome traits analysis on endothelial lineage cells discloses biomarker potential Circulating MicroRNAs which affect progenitor activities. BMC Genom. 15, 802. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-15-802 (2014).

Sehgal, M. et al. IFN-alpha-induced downregulation of miR-221 in dendritic cells: implications for HCV pathogenesis and treatment. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 35, 698–709. https://doi.org/10.1089/jir.2014.0211 (2015).

Terasawa, K. et al. Sustained activation of ERK1/2 by NGF induces microRNA-221 and 222 in PC12 cells. FEBS J. 276, 3269–3276. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07041.x (2009).

Aguilo, N. et al. Bim is a crucial regulator of apoptosis induced by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Cell. Death Dis. 5, e1343. https://doi.org/10.1038/cddis.2014.313 (2014).

Luo, S. et al. BCL2L11/BIM: a novel molecular link between autophagy and apoptosis. Autophagy 9, 104–105. https://doi.org/10.4161/auto.22399 (2013).

Fang, Y. et al. Arsenic trioxide as a novel anti-glioma drug: a review. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 25, 44. https://doi.org/10.1186/s11658-020-00236-7 (2020).

Huang, W. et al. A candidate for lung cancer treatment: arsenic trioxide. Clin. Transl Oncol. 21, 1115–1126. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12094-019-02054-6 (2019).

Biswas, T. et al. A novel non-radioactive primase-pyrophosphatase activity assay and its application to the discovery of inhibitors of Mycobacterium tuberculosis primase DnaG. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, e56. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gks1292 (2013).

Ilic, S. et al. DnaG Primase-a target for the development of novel antibacterial agents. Antibiot. (Basel). 7 https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics7030072 (2018).

Barrett, T. et al. NCBI GEO: mining tens of millions of expression profiles–database and tools update. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, D760–765. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkl887 (2007).

Davis, S. et al. GEOquery: a Bridge between the gene expression omnibus (GEO) and BioConductor, Bioinformatics, 23 1846–1847, (2007). https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btm254

Stelzer, G. et al. The genecards suite: from gene data mining to disease genome sequence analyses. Curr. Protoc. Bioinf. 54 https://doi.org/10.1002/cpbi.5 (2016). 1 30 31–31 30 33.

Liberzon, A. et al. The molecular signatures database (MSigDB) hallmark gene set collection. Cell. Syst. 1, 417–425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cels.2015.12.004 (2015).

Ritchie, M. E. et al. Limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, e47. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkv007 (2015).

Mandrekar, J. N. Receiver operating characteristic curve in diagnostic test assessment. J. Thorac. Oncol. 5, 1315–1316. https://doi.org/10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181ec173d (2010).

Yu, G. Gene ontology semantic similarity analysis using gosemsim. Methods Mol. Biol. 2117, 207–215. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-0716-0301-7_11 (2020).

Kanehisa, M. et al. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/28.1.27 (2000).

Yu, G. et al. ClusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS 16, 284–287. https://doi.org/10.1089/omi.2011.0118 (2012).

Subramanian, A. et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 102, 15545–15550. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0506580102 (2005).

Zhou, J. et al. Protein function prediction based on Ppi networks: network reconstruction vs edge enrichment. Front. Genet. 12, 758131. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2021.758131 (2021).

Szklarczyk, D. et al. STRING v11: protein-protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D607–D613. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gky1131 (2019).

Shannon, P. et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 13, 2498–2504. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.1239303 (2003).

Chen, Y. et al. MiRDB: an online database for prediction of functional MicroRNA targets. Nucleic Acids Res. 48 https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkz757 (2020). D127-D131.

Li, J. H. et al. StarBase v2.0: decoding miRNA-ceRNA, miRNA-ncRNA and protein-RNA interaction networks from large-scale CLIP-Seq data. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D92–97. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkt1248 (2014).

Zhou, K. R. et al. ChIPBase v2.0: decoding transcriptional regulatory networks of non-coding RNAs and protein-coding genes from ChIP-seq data. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, D43–D50. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkw965 (2017).

Zhang, Q. et al. hTFtarget: A comprehensive database for regulations of human transcription factors and their targets. Genomics Proteom. Bioinf. 18, 120–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gpb.2019.09.006 (2020).

Davis, A. P. et al. Comparative toxicogenomics database (CTD): update 2021. Nucleic Acids Res. 49 https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkaa891 (2021). D1138-D1143.

Newman, A. M. et al. Robust enumeration of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat. Methods. 12, 453–457. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.3337 (2015).

Chen, B. et al. Profiling tumor infiltrating immune cells with CIBERSORT. Methods Mol. Biol. 1711, 243–259. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-7493-1_12 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge contributions from the GEO, GeneCards, MSigDB, miRDB, ENCOR1, CHIPBase, HTFtarget and CTD databases for providing their platforms. This work was supported by grants from the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (2025JJ80543) and the Scientific Research Project of Hunan Provincial Health Commission (20254080).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Jianhua Pan: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft; Aifeng Liu: Data curation, Software, Validation, Funding acquisition; Sifang Xiao: Visualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing; Xiaohua Ma: Conceptualization, Resources, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pan, J., Liu, A., Xiao, S. et al. Identification of apoptosis-related genes as potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets in cystic fibrosis patients progressing to pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial disease. Sci Rep 15, 40925 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24346-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24346-4