Abstract

Bronchiectasis is a complex, heterogeneous inflammatory chronic respiratory disease with an unknown etiology. In the context of increasingly severe drug resistance, there is an urgent need to explore new treatment strategies. Apigenin is a natural flavonoid compound with significant anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities. This study aims to investigate the material basis and related pharmacological mechanisms of apigenin in the treatment of bronchiectasis using network pharmacology and molecular docking technology. The components and related targets of apigenin were searched using the TCMSP database. The SMILES numbers of each component of apigenin were obtained from the PubChem database, and the targets of each component were predicted using SwissTargetPrediction. All targets of the apigenin components were integrated. Targets related to bronchiectasis were retrieved and integrated from the GeneCards, TTD, and OMIM databases. The intersection targets of apigenin and bronchiectasis were identified using Venny 2.1.0 software. A protein-protein interaction (PPI) network was constructed and analyzed for topology using the String database platform and Cytoscape 3.10.3 software to screen out the main core targets. Gene Ontology (GO) functional enrichment analysis and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis were performed on the intersection targets using the David database. The binding activity between apigenin and the main core targets was tested using molecular docking technology. A total of 166 targets of apigenin and 2018 targets of bronchiectasis were screened, with 54 intersection targets identified between apigenin and bronchiectasis. The main core targets for apigenin in treating bronchiectasis were AKT1, MMP9, PARP1, SRC, and PTGS2. GO functional enrichment and KEGG pathway analyses yielded 380 GO entries (P < 0.05) and 111 signaling pathways (P < 0.05). These included 247 biological process entries, 35 cellular component entries, and 98 molecular function entries, primarily involving the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, Chemokine signaling pathway, Lipid and atherosclerosis, Pathways in cancer, among others. Molecular docking results indicated that the binding energies between apigenin and these five core targets: AKT1, MMP9, PARP1, SRC, and PTGS2 were − 8.3 kcal/mol, -9.6 kcal/mol, -9.0 kcal/mol, -7.8 kcal/mol and − 8.8 kcal/mol, respectively, suggesting favorable binding activity between apigenin and the main core targets. Conclusion: From the perspective of network pharmacology and molecular docking technology, this study links apigenin to bronchiectasis at the molecular level for the first time. It systematically reveals the potential of apigenin to treat bronchiectasis through multiple targets and pathways. This provides a theoretical basis for in-depth exploration of the mechanism of apigenin in treating bronchiectasis and lays a foundation for subsequent experimental validation and clinical translation.

Similar content being viewed by others

1. Introduction

Bronchiectasis is a chronic respiratory disease characterised by permanent bronchial dilatation evidenced at chest computed tomography (CT)1, with important geographical variation in causes, severity and outcomes2. The main clinical manifestations of bronchiectasis are chronic cough, expectoration of large amounts of purulent sputum, and/or recurrent hemoptysis3. In the last few decades, bronchiectasis has rapidly moved from being a rare or orphan disease to a global problem, with a large-scale trend towards increasing incidence and prevalence4. Global data indicate a bronchiectasis prevalence rate of 680 per 100,000 population5. In China, the prevalence of bronchiectasis is significantly higher among individuals aged ≥ 40 years, reaching 1,200 per 100,000 population6, posing a substantial threat to human health. Bronchiectasis leads to a considerable economic burden for healthcare systems and patients7,8. Consequently, due to its significant socioeconomic burden, bronchiectasis has become a chronic airway disease attracting increasing concern9. Bronchiectasis is an inflammatory disease associated with an imbalance between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory signaling. This imbalance leads to the recruitment of inflammatory cells and ultimately establishes a self-perpetuating cycle of inflammation10,11. The goals of bronchiectasis treatment are to alleviate the symptom burden, improve quality of life, reduce acute exacerbations, and prevent disease progression12.

Currently, the clinical treatment of bronchiectasis primarily focuses on managing acute exacerbations, often employing symptomatic treatments such as antimicrobial agents, expectorants, and bronchodilators. However, conventional monotherapy often yields suboptimal results. Furthermore, long-term antibiotic use in patients can easily lead to the emergence and colonization of drug-resistant bacteria, or result in superinfections, significantly increasing adverse drug reactions. This leads to poor long-term efficacy and increased difficulty in achieving clinical cure. Therefore, there is an urgent need for new treatment strategies. Globally, more people are switching to herbal therapy for inflammatory-mediated illnesses. Herbal treatments work through various methods, including immunological control, antioxidant action, suppression of nuclear factor-kappa B and leukotriene B4, and antiplatelet activity13. Natural products (NPs) have historically served as a crucial source for drug discovery, particularly in areas such as oncology and infectious diseases. Compared to synthetic molecules, NPs possess distinctive characteristics including diverse scaffolds, complex structures, higher molecular weight, and greater hydrophilicity. These attributes present both opportunities and challenges for drug discovery14. Over the past two decades, NPs have played a significant role in drug discovery, with numerous clinical drugs being derived from natural compounds. Recent studies have highlighted the potential plant-based treatments for disease, including anti-cancer agents from African lettuce and Brucea javanica. A classic example is Artemisinin, which is isolated from the plant Artemisia annua. NPs and their derivatives constitute a substantial proportion of pharmaceuticals that have advanced through clinical trials15,16. Toxicological studies have further indicated that NPs and their derivatives generally exhibit lower toxicity profiles compared to synthetic drugs, suggesting their potential prioritization in drug development programs17. Within this context, NPs have garnered substantial research interest as promising therapeutic candidates.

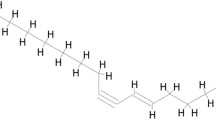

Apigenin is a 4,5,7-trihydroxyflavone, and is a small-molecule edible flavonoid compound derived from plants of the Apiaceae family18. Apigenin can be found in significant quantities in vegetables, fruit, herbs, cereals, and herbal drinks19. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) database has inventoried the flavonoid content of 506 food products that include apigenin19. Particularly rutabaga and fresh parsley, at levels of 3850 mg/kg and 2154.6 mg/kg, respectively20, Other common sources include guava, mulberry leaf, belimbi fruit, onions, grapefruit, oranges, and chamomile20,21,22. Numerous studies reported in the literature have confirmed the beneficial properties of apigenin, including: Anti-inflammatory23、Antiviral24、Antibacterial25、Antioxidant26、Anticancer/Anti-metastatic27、Antihypertensive28 effects. Research has demonstrated that apigenin can mitigate lung injury by scavenging free radicals and modulating oxidative stress. In a silica-induced lung injury model, apigenin (25 µM) exhibited pulmonary protective effects comparable to those of medicinal plant extracts, effectively restoring oxidative stress marker levels29. A meta-analysis indicated that the immunomodulatory properties of apigenin may hold therapeutic potential for various lung injury diseases, though its clinical efficacy requires further validation through more reliable preclinical models and clinical settings30. Although the aforementioned studies have revealed the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects of apigenin, there is a lack of direct research focusing on the relationship between apigenin and bronchiectasis. The therapeutic potential of apigenin for this specific disease and its underlying molecular mechanisms remain largely unexplored. Therefore, this study employs network pharmacology combined with molecular docking technology to investigate the material basis and pharmacological mechanisms of apigenin in the treatment of bronchiectasis, thereby providing essential scientific and theoretical foundations for its further development and utilization.The technical procedures undertaken in this study are presented as a flowchart (Fig. 1).

Materials and methods

Acquisition of apigenin-related targets

The keyword “apigenin” was entered into the TCMSP database (https://www.tcmsp-e.com/) (access date: March 2025) to obtain its Mol ID and corresponding molecular name. The molecular name was input into the PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) (access date: March 2025) to retrieve the SMILES number. These SMILES number was subsequently submitted to the SwissTargetPrediction database (http://swisstargetprediction.ch/) (access date: March 2025) for target prediction. Targets with a probability score > 0 were selected and compiled31. The corresponding UniProt IDs for the target proteins were identified. Using the ID Mapping tool within UniProt (https://www.uniprot.org/) (access date: March 2025), UniProt IDs were converted to gene symbols. The resulting gene symbols were then consolidated and duplicates were removed, yielding the final set of potential drug targets for apigenin.

Acquisition of bronchiectasis-related targets

The keyword “bronchiectasis” was systematically queried across three disease genetics databases: GeneCards (https://www.genecards.org/) (access date: March 2025)、Therapeutic Target Database (TTD) (https://db.idrblab.net/ttd/) (access date: March 2025)、Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) (https://omim.org/) (access date: March 2025). Targets from the GeneCards database were filtered to include the top 2000 entries based on relevance score32,33, while all targets identified from the TTD and OMIM databases were collected. These targets were then systematically organized, sorted, and deduplicated to establish the potential disease targets for bronchiectasis.

Prediction of apigenin targets for bronchiectasis

The Venny 2.1.0 online software (https://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/index.html) was utilized to obtain the targets of apigenin and those of bronchiectasis. The intersection of these two sets of targets was determined. The targets within this intersection are considered the potential therapeutic targets for apigenin in the treatment of bronchiectasis.

Construction of protein-protein interaction (PPI) network and topological analysis

STRING (https://cn.string-db.org/) is an online bioinformatics database that aims to provide information on gene and protein interactions. The intersecting targets were imported into the STRING database (access date: March 2025), with the screening condition set at “minimum required interaction score ≥ 0.4”16,34. The TSV file was then downloaded and saved. Finally, the PPI network was visualized and the “apigenin-bronchiectasis” multidimensional network was constructed using Cytoscape software (version 3.10.3). In the network illustration, nodes symbolized active constituents and target genes, while edges illustrated interactions between them35. Topological analysis was performed using the Mcode and cytoHubba plug-ins to screen for core targets16.

GO functional enrichment and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis

To explore the potential biological functions and major signaling pathways of apigenin in the treatment of bronchiectasis, the DAVID database (https://davidbioinformatics.nih.gov/) (access date: April 2025) was used to perform Gene Ontology (GO) functional enrichment analysis and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis on the common targets of apigenin and bronchiectasis. A significance level of P < 0.05 was established, and the enrichment results were sorted based on P-value in ascending order. The significantly different enrichment results were identified and the enrichment results were output separately, including the top 10 biological functions of GO enrichment (biological process, molecular function, and cellular component) and the top 15 KEGG signaling pathways.

Molecular docking

Molecular docking was performed between the core targets screened in 2.4 and apigenin. The structures of apigenin and the core target proteins were obtained from the PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) (access date: April 2025) and the PDB database (https://www.rcsb.org/) (access date: April 2025). The protein structures were processed to remove water molecules using Pymol 3.0.3 software. The proteins and ligands were then prepared using Autodocktools 1.5.7. Molecular docking was carried out using Autodock Vina 1.1.2 software. The chemical bond analysis of the docking results was performed using ligplot + 1.4.2 software, and the results were visualized using Pymol 3.0.3 software.

Ethics approval

All data used in this study were obtained from publicly accessible databases, and no ethical issues were involved.

Results

Prediction results of apigenin active molecules and potential binding targets

Fifty-three active molecules were obtained from the TCMSP database. The SMILES numbers of these identified active molecules were retrieved from the PubChem database. Target prediction for the active components was performed using SwissTargetPrediction, yielding a total of 1,039 targets. After screening and deduplication, 166 apigenin targets were ultimately identified.

Bronchiectasis-related targets

The keyword “Bronchiectasis” was searched in the GeneCards, TTD, and OMIM databases, yielding 2,783, 4, and 142 disease targets, respectively. The top 2,000 targets by relevance score from GeneCards were combined with all targets from TTD and OMIM, resulting in 2,146 disease targets. After deduplication, 2,018 disease targets related to bronchiectasis were ultimately obtained.

Intersection analysis of apigenin-related target genes and bronchiectasis-related targets

Using the Venny 2.1.0 online software, the targets of apigenin and the targets of bronchiectasis were input separately, and the intersection was taken. A total of 54 common targets were obtained (Fig. 2).

Construction of the PPI network of common targets and topological analysis results

The shared targets of apigenin and bronchiectasis were uploaded to the STRING database for PPI network analysis (Fig. 3), yielding 54 nodes and 385 interaction edges. Each node represents a common target, with larger nodes indicating higher degree values; edges denote protein–protein interactions, and thicker edges indicate stronger interactions. The analysis results were then imported into Cytoscape 3.10.3 software to construct the apigenin-bronchiectasis-target network (Fig. 4). This network comprises 56 nodes (54 target nodes, one drug node, and one disease node) connected by 108 edges. Topological parameters calculated with the Network Analyzer plug-in revealed an average neighbor connectivity of 3.857, network heterogeneity of 2.502, network density of 0.070, and a network centralization of 0.945. These parameters indicate that the proteins in the network are not uniformly connected but are instead dominated by a few key hub proteins, which aligns with the core targets subsequently identified through Mcode and cytoHubba analyses. From a biological perspective, this suggests that the therapeutic effect of apigenin on bronchiectasis may not be achieved through broad, dispersed regulation. Instead, it likely acts precisely on these centrally located, highly influential core targets within the network, thereby efficiently coordinating the functions of the entire cellular signaling network. Furthermore, the relatively high average node degree (3.857) implies that most targets are connected to multiple partners, reflecting the inherent multifunctionality and robustness of biological systems. The network heterogeneity (2.502) further confirms that the distribution of node connectivity in the network is uneven, with a small number of nodes exhibiting exceptionally high connectivity. In the figure, triangles symbolize the drug node, circles represent the disease node, and diamonds denote the common targets shared by apigenin and bronchiectasis. Each edge signifies an interaction between apigenin and its target, as well as the relationship between the target and bronchiectasis.

Topological analysis of the PPI network was performed using the Mcode and cytoHubba plug-ins to screen for the main target genes after taking the intersection. The targets screened by the Mcode plug-in were: ABCB1, AKT1, CDK1, GSK3B, IKBKB, KIT, MAPK3, MET, MMP2, MMP9, MPO, PARP1, PLG, PRKDC, PTGS2, SRC, SYK. The top ten targets in each of the MCC, MNC, and EPC modes of the cytoHubba plug-in were selected. The main targets in the MCC mode were: TP53, AKT1, EGFR, TNF, SRC, MMP9, PTGS2, PARP1, ABCB1, MMP2. The main targets in the MNC mode were: TP53, EGFR, TNF, AKT1, SRC, PTGS2, MMP9, PARP1, MAPK3, GSK3B. The main targets in the EPC mode were: TP53, TNF, EGFR, AKT1, SRC, MMP9, PARP1, MAPK3, PTGS2, GSK3B. The intersection of the targets in the MCC, MNC, EPC, and Mcode modes yielded the main target genes: AKT1, MMP9, PARP1, SRC, PTGS2.

GO functional enrichment and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of the intersection targets

GO functional enrichment and KEGG pathway analyses were performed on the 54 common targets shared between apigenin-related targets and bronchiectasis-related targets. A total of 380 GO terms (P < 0.05) and 111 signaling pathways (P < 0.05) were obtained. Among these, 247 terms were associated with biological processes, primarily involving chromatin remodeling, negative regulation of apoptotic process, signal transduction, positive regulation of transcription by RNA polymerase II, response to xenobiotic stimulus, protein phosphorylation, peptidyl-serine phosphorylation, DNA damage response, inflammatory response, and insulin receptor signaling pathway. 35 terms were related to cellular components, mainly including plasma membrane, cytoplasm, cytosol, nucleus, membrane, nucleoplasm, extracellular exosome, protein-containing complex, extracellular space, and extracellular region. 98 terms were linked to molecular functions, predominantly involving protein binding, ATP binding, identical protein binding, protein kinase activity, enzyme binding, protein serine/threonine kinase activity, protein serine kinase activity, kinase activity, histone H3Y41 kinase activity, and histone H2AXY142 kinase activity. The top ten entries were selected for visualization (Fig. 5). KEGG enrichment analysis identified a total of 111 signaling pathways, with the top 15 pathways displayed in the bubble chart of Fig. 6.

Molecular docking results

The PDB files corresponding to the obtained core targets were downloaded, which are: AKT1 (PDB ID: 8UW9), MMP9 (PDB ID: 8K5Y), PARP1 (PDB ID: 7KK5), SRC (PDB ID: 8JN8), PTGS2 (PDB ID: 5F19). Molecular docking was performed between apigenin and each of the above five core targets, and the results are shown in Table 1. The absolute value of the binding energy reflects the strength of the binding ability. The ranking of the absolute values is: MMP9|−9.6|> PARP1|−9.0|> PTGS2|−8.8|> AKT1|−8.3|> SRC|−7.8|. It can be seen that the above five core targets bind tightly with apigenin. This indicates that apigenin has a good binding ability with the above targets in bronchiectasis. The molecular docking is shown in Fig. 7.

Discussion

Bronchiectasis has become one of the main components of chronic respiratory diseases. In recent years, the prevalence of bronchiectasis has become the third highest among chronic airway diseases36. Respiratory diseases not only severely affect the quality of life of patients but may also lead to a series of complications and even death. Bacterial, fungal, or viral infections are important drivers of acute exacerbations of bronchiectasis, especially in the context of increasing drug resistance37. Therefore, given the limitations of antibiotic therapy, researchers are now seeking more effective and less adverse treatments. Dietary phytochemicals, such as flavonoids, have the advantage of low toxicity, can reduce multidrug resistance38,39, and have significant therapeutic effects in various disease models24. In addition, like other dietary flavonoids, apigenin has the advantages of being inexpensive and easily accessible39,40. Although other flavonoids (such as quercetin and luteolin) have been extensively studied in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or asthma41,42, similar network pharmacology or experimental research specifically targeting bronchiectasis remains highly limited.

In this study, through network pharmacology analysis of the common action targets between apigenin and bronchiectasis, it was found that there were 54 core targets shared by apigenin and bronchiectasis. After PPI network analysis and topological analysis, five main core targets were finally screened: AKT1, MMP9, PARP1, SRC, PTGS2. AKT1 is one of the three closely related AKT kinases (AKT1, AKT2, and AKT3), which can regulate many processes including cell metabolism, proliferation, growth, and angiogenesis43,44,45,46. AKT1 is a serine/threonine kinase and a multifunctional protein47. These proteins can be phosphorylated by phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K), and the AKT/PI3K pathway is a key component of many signaling pathways, involved in the growth regulation of almost all cells. MMP9 is a member of the matrix metalloproteinase family and is involved in biological processes such as cytokine mediation, neutrophil migration, and macrophage differentiation, it is mainly synthesized and secreted by inflammatory cells (such as macrophages and T lymphocytes)48. MMP9 is involved in many basic biological processes, such as development, angiogenesis, apoptosis, inflammation, and cancer. Its expression and activity have a wide range of effects on the regulation of physiological and pathological processes in the body. For many diseases, MMP9 is not only a powerful biomarker but also a potential therapeutic target49,50. MMP9 can participate in the regulation of inflammatory cell infiltration by degrading type IV collagen51. There is evidence that MMP9 is involved in the pathophysiology of bronchiectasis52. TAYLOR et al.53 found that MMP9 levels are elevated in bronchiectasis. Compared with healthy controls, MMP9 is significantly increased in patients with bronchiectasis and is particularly elevated during exacerbations of the disease54. PARP1 is a nuclear enzyme that plays a crucial role in DNA repair and is also involved in various biochemical activities in the body, such as signal transduction and inflammation55. Under inflammatory stimulation, PARP1 is activated and participates in the regulation of the production and release of inflammatory factors. Studies have shown that PARP1 is involved in the activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway56, PARP1 regulates the expression of several NF-κB dependent cytokines, chemokines, adhesion molecules, inducible nitricoxide synthase (iNOS), which play a critical role in manifestation of inflammatory cycle57,58,59,60. And the NF-κB signaling pathway plays an important role in resisting infections by invading pathogens61. Src kinase was one of the first tyrosine kinase oncogenes to be discovered and is the protein most closely related to human diseases such as cancer and inflammation62. The regulation of neutrophil functions by Src kinase mainly includes ROS production, adhesion-dependent degranulation, NETs formation, integrin activation, and migration to sites of infection63,64. In addition, Src kinase is a protein involved in intracellular signaling of the acute inflammatory response, and the phosphorylation of Src kinase is a major factor in the expression and production of inflammatory mediators, mainly participating in the activation of inflammatory cells and the increase of vascular endothelial cell permeability62. Numerous studies have shown that inhibiting Src kinase has preventive and therapeutic effects on acute inflammatory responses, confirming that Src kinase plays a key role in macrophage-mediated inflammatory responses63,64. PTGS2, also known as cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2), plays a crucial role in regulating the body’s inflammatory response. It is a key enzyme in prostaglandin biosynthesis and can promote the expression of prostaglandins under the stimulation of inflammatory cytokines in the body65,66. PTGS2 plays a key role in regulating inflammatory responses by producing prostaglandins, which play an important role in regulating vascular tone, thrombosis, inflammation, and pain67,68. In summary, the five core targets identified in this study play pivotal roles in inflammation-related processes. Therefore, we hypothesize that apigenin may alleviate bronchitis by modulating the levels of inflammatory factors.

Persistent airway inflammation is a pathophysiological hallmark of bronchiectasis69. Consequently, core targets associated with bronchial inflammation may help identify molecular pathways relevant to apigenin treatment. This process involves the participation of various inflammatory cells, including neutrophils, macrophages, eosinophils, lymphocytes, and epithelial cells52. Under inflammatory stimulation, inflammatory cells such as neutrophils release reactive oxygen species (ROS), which can further activate inflammatory cells and promote the release of inflammatory mediators. This cascade leads to amplified and sustained inflammatory responses, resulting in further damage and destruction of the bronchial wall.

Through GO and KEGG enrichment analysis, we have identified several biological processes, cellular components, molecular functions, and signaling pathways closely related to bronchiectasis in apigenin. During the process of bronchiectasis, cells are subjected to various stimuli such as inflammatory responses, DNA damage responses, negative regulation of apoptotic processes, signal transduction, and protein phosphorylation. These processes can damage the cell membrane, proteins, and DNA, and affect the activity of inflammation-related protein kinases, protein binding, and enzyme binding. KEGG analysis revealed that most molecular pathways are associated with infectious and non-infectious immune activation, relating to inflammation or immune responses. The KEGG enrichment results indicated that some significantly enriched pathways such as Pathways in cancer, MicroRNAs in cancer, Gastric cancer, Human papillomavirus infection, Human T-cell leukemia virus 1 infection, and Human cytomegalovirus infection are not classical pathological pathways of bronchiectasis. This reflects the characteristic “multi-target, multi-pathway” nature of network pharmacology analysis, wherein an active compound acts on its entire known set of targets in the human body, many of which are molecular switches shared by multiple diseases. We interpret the emergence of these pathways not as direct evidence that apigenin treats cancer or viral infections, but rather as an indication that the core molecular mechanisms encompassed by these pathways also play significant roles in bronchiectasis. Taking cancer pathways as an example: many cancer-related pathways (such as the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway) are fundamentally core cellular signal transduction pathways. Existing studies have clearly indicated that while the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway has been established as a key oncogenic pathway in cancers such as lung cancer70, its mechanism of action in bronchiectasis differs. In bronchiectasis, this pathway is more involved in inflammation regulation rather than cell proliferation, for instance, by influencing IL-1β release and neutrophil function71,72. The intersection with cancer signaling pathways offers new perspectives for understanding the heterogeneity of bronchiectasis73. Taking viral infection pathways as an example: viruses activate growth factor receptors (GFR) and downstream pathways such as mTOR through phosphorylation-mediated modification of host proteins, and these pathways may serve as potential drug targets74. Viruses evade immune attacks and promote inflammatory responses by regulating interferon signaling, cytokine profiles (e.g. IL-17), and dendritic cell maturation75.Viruses such as HIV and HTLV-1 evade immunity and promote clonal expansion of infected cells by modulating host signaling pathways (e.g. Tax/HBZ gene expression)76,77. Therefore, we hypothesize that the significant activity of apigenin against bronchiectasis is associated with its anti-inflammatory and anti-infective effects.

Evidence indicates that apigenin modulates multiple signaling pathways involved in inflammation, oxidative stress, and cell death; these commonly include inhibition of the NF-κB signaling cascade, nitric-oxide synthase, and COX-2 activity19. Apigenin can reduce airway inflammatory responses by inhibiting the activation and infiltration of these inflammatory cells, suppressing the NF-κB signaling pathway, and reducing the production of inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β78,79. The NF-κB signaling pathway plays an important role in inflammatory responses and immune regulation. The NF-κB signaling pathway is crucial for resisting infections by invading pathogens. The activated of NF-κB and its downstream inflammation-related genes, which are involved in the regulation of chronic inflammation61. Apigenin can exert its effects through multiple mechanisms, including inhibiting oxidases, modulating redox signaling pathways (such as NF-κB, Nrf2, MAPK, etc.), enhancing the endogenous antioxidant system, metal chelation, and free radical scavenging26. The PI3K-AKT pathway plays a central regulatory role in inflammatory diseases. By modulating downstream signaling molecules such as NF-κB, Nrf2, and Foxo1, it influences the release of inflammatory factors, oxidative stress responses, and apoptotic processes. Activation of this pathway promotes the production of pro-inflammatory mediators (e.g. IL-1β, TNF-α)80,81,82, while suppressing antioxidant pathways (e.g. Nrf2)83, thereby fostering a pro-inflammatory microenvironment. Nrf2, as a downstream transcription factor regulated by the PI3K-AKT pathway, is a key transcription factor in controlling redox balance and suppressing inflammatory responses84. Oxidative stress is a critical factor in the pathogenesis of bronchiectasis. Traditional Chinese medicine has been shown to regulate oxygen free radicals in bronchiectasis, inhibit peroxidation reactions, and protect bronchial epithelial cells. Many Nrf2 activators can effectively inhibit oxidative stress and have been widely developed for the treatment of inflammatory diseases, such as EGCG, astaxanthin, and curcumin85. Kim et al.86 demonstrated that apigenin can enhance the body’s antioxidant capacity by increasing the levels of SOD, GSH-Px, and CAT. Furthermore, the KEGG enrichment analysis also identified indirectly related pathways such as “Lipid and atherosclerosis”, it does not imply that apigenin directly treats cardiovascular diseases. Rather, it reveals core molecular mechanisms shared across different diseases. Studies have shown that patients with bronchiectasis are at a high risk for cardiovascular diseases and that bronchiectasis is an independent risk factor for ischemic stroke87,88, The chronic inflammatory state in bronchiectasis may promote atherosclerosis, as evidenced by a significantly increased carotid intima-media thickness (CIMT) in severe bronchiectasis patients, indicating elevated subclinical atherosclerosis risk89. Chronic systemic inflammation and oxidative stress represent the shared pathological basis connecting these two conditions. Key molecules enriched in these indirectly related pathways such as NF-κB, TNF-α, and various oxidative stress-related genes also function as core components of the inflammatory network in bronchiectasis. Apigenin exhibits strong capabilities in suppressing NF-κB signaling and scavenging reactive oxygen species, with its target profile covering these shared molecular elements. Thus, the emergence of these indirectly associated pathways systemically validates the rationale for apigenin’s potential therapeutic effect on bronchiectasis through the modulation of fundamental inflammatory processes. This demonstrates that both directly and indirectly related pathways are intrinsically linked to a classic, shared inflammatory regulatory signaling network, collectively forming the core anti-inflammatory mechanism through which apigenin intervenes in bronchiectasis.

Molecular docking technology was employed to conduct molecular docking between apigenin and the core target proteins of bronchiectasis. The binding energy values indicated that the active components have good binding activity with the receptors. It is generally believed that when the binding energy between the receptor protein and the ligand small molecule is less than − 5 kcal/mol, there is good binding activity, and when it is less than − 7 kcal/mol, there is strong binding activity. The molecular docking results in this study showed that the binding energies between the core target proteins AKT1, MMP9, PARP1, SRC, and PTGS2 and apigenin were all less than − 7 kcal/mol. This indicates that apigenin has good binding ability with the above core target proteins of bronchiectasis and can form stable complexes to exert therapeutic effects on bronchiectasis. Among them, MMP9 had the highest binding activity with apigenin, indicating the strongest binding ability between the two.

Although the primary findings of this study are based on computational predictions derived from network pharmacology and molecular docking, and despite employing strategies such as cross-validation across multiple databases and mutual confirmation through various algorithms to enhance reliability, these results remain in the hypothesis-generating stage. We emphasize that the ultimate validity of these computational predictions must be verified through a series of rigorous in vitro and in vivo experiments. Nevertheless, the conclusions of this study can provide insights and directions for subsequent experimental validation and lay a foundation for future experimental verification and clinical translation. However, in the practical application of apigenin, researchers still face a series of challenges and problems. The first is the bioavailability of apigenin. Due to its poor absorption in the gastrointestinal tract, its oral bioavailability is low, which limits its clinical application. To improve the bioavailability of apigenin, some studies have begun to try to use nanotechnology and drug delivery systems to improve it. Several approaches to improve its solubility, including different delivery systems (liposomes, polymeric micelles, nanosuspension, and so on)90,91, showed how solid dispersion for enhancing the solubility and dissolution of drugs with poor water solubility improved stability as well as dosing91; in particular, different injectable nanosized drug delivery systems have been developed, suggesting that nanocapsules may be a good approach to prolong apigenin’ pharmacological activity92.

Conclusion

In summary, this study is the first to systematically investigatethe potential molecular mechanisms of apigenin in the treatment of bronchiectasis from the perspectives of network pharmacology and molecular docking. Our data demonstrate that Apigenin may exert its therapeutic effects on bronchiectasis by acting on targets such as AKT1, MMP9, PARP1, SRC, and PTGS2, and regulating signaling pathways such as PI3K/AKT, Pathways in cancer, and Lipid and atherosclerosis etc. This study reveals that apigenin may intervene in the pathogenesis of bronchiectasis through multi-target and multi-pathway mechanisms, thereby providing a theoretical foundation for subsequent research on apigenin in the treatment of bronchiectasis.

Future perspectives

This study suggests that apigenin may be a promising therapeutic agent for bronchiectasis. Future research should include in vivo studies, clinical trials, and further investigation into the mechanisms of action of apigenin. Additionally, developing suitable formulations, exploring combination therapies, and securing patent protection are critical steps in drug development. Finally, investigating the synergistic effects of apigenin with other natural compounds could enhance its therapeutic potential.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

References

Aliberti, S. et al. Criteria and definitions for the radiological and clinical diagnosis of bronchiectasis in adults for use in clinical trials: international consensus recommendations. Lancet Respir Med. 10, 298–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00277-0 (2022).

Chalmers, J. D. et al. Bronchiectasis in europe: data on disease characteristics from the European bronchiectasis registry (EMBARC). Lancet Respir Med. 11, 637–649. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(23)00093-0 (2023).

Polverino, E. et al. European respiratory society guidelines for the management of adult bronchiectasis. Eur. Respir J. 50, 1700629. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00629-2017 (2017).

Chalmers, J. D. Bronchiectasis from 2012 to 2022. Clin. Chest Med. 43, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccm.2021.12.001 (2022).

Wang, L., Wang, J., Zhao, G. & Li, J. Prevalence of bronchiectasis in adults: a meta-analysis. BMC Public. Health. 24, 2675. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-19956-y (2024).

Choi, H. et al. Bronchiectasis in asia: a review of current status and challenges. Eur. Respir Rev. 33, 240096. https://doi.org/10.1183/16000617.0096-2024 (2024).

Roberts, J. M. et al. The economic burden of bronchiectasis: A systematic review. Chest 164, 1396–1421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2023.06.040 (2023).

Goeminne, P. C. & Vanfleteren, L. E. G. W. Bronchiectasis economics: spend money to save money. Respiration 96, 399–402. https://doi.org/10.1159/000490550 (2018).

Guan, W. J., Han, X. R., de la Rosa-Carrillo, D. & Martinez-Garcia, M. A. The significant global economic burden of bronchiectasis: a pending matter. Eur. Respir J. 53, 1802392. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.02392-2018 (2019).

Keir, H. R. & Chalmers, J. D. Pathophysiology of bronchiectasis. Semin Respir Crit. Care Med. 42, 499–512. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0041-1730891 (2021).

Watt, A. P. et al. Neutrophil apoptosis, Proinflammatory mediators and cell counts in bronchiectasis. Thorax 59, 231–236. https://doi.org/10.1136/thx.2003.008037 (2004).

Choi, H., McShane, P. J., Aliberti, S. & Chalmers, J. D. Bronchiectasis management in adults: state of the Art and future directions. Eur. Respir J. 63, 2400518. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00518-2024 (2024).

Triantafyllidi, A., Xanthos, T., Papalois, A. & Triantafillidis, J. K. Herbal and plant therapy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Ann. Gastroenterol. 28, 210–220 (2015).

Lyu, Y. L. et al. Biological activities underlying the therapeutic effect of quercetin on inflammatory bowel disease. Mediators Inflamm 2022, 5665778. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/5665778 (2022).

Atanasov, A. G., Zotchev, S. B., Dirsch, V. M. & Supuran, C. T. Natural products in drug discovery: advances and opportunities. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 20, 200–216. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41573-020-00114-z (2021).

Sabarathinam, S. Unveiling the therapeutic potential of Quercetin and its metabolite (Q3OG) for targeting inflammatory pathways in crohn’s disease: A network Pharmacology and molecular dynamics approach. Hum. Gene. 43, 201372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humgen.2024.201372 (2025).

Domingo-Fernández, D. et al. Natural products have increased rates of clinical trial success throughout the drug development process. J. Nat. Prod. 87, 1844–1851. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jnatprod.4c00581 (2024).

Imran, M. et al. Apigenin as an anticancer agent. Phytother Res. 34, 1812–1828. https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.6647 (2020).

Charrière, K. et al. Exploring the role of apigenin in neuroinflammation: insights and implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25, 5041. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25095041 (2024).

Miean, K. H. & Mohamed, S. Flavonoid (myricetin, quercetin, kaempferol, luteolin, and apigenin) content of edible tropical plants. J. Agric. Food Chem. 49, 3106–3112. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf000892m (2001).

Salehi, B. et al. The therapeutic potential of apigenin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 1305. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20061305 (2019).

Shukla, S. & Gupta, S. Apigenin: a promising molecule for cancer prevention. Pharm. Res. 27, 962–978. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11095-010-0089-7 (2010).

Chen, P. et al. Apigenin exhibits anti-inflammatory effects in LPS-stimulated BV2 microglia through activating GSK3β/Nrf2 signaling pathway. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 42, 9–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923973.2019.1688345 (2020).

Lee, I. G., Lee, J., Hong, S. H. & Seo, Y. J. Apigenin’s therapeutic potential against viral infection. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed). 28, 237. https://doi.org/10.31083/j.fbl2810237 (2023).

Zhu, L., Zhang, H., Zhang, X., Xia, L. & Zhang, J. Research progress on antisepsis effect of apigenin and its mechanism of action. Heliyon 9, e22290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e22290 (2023).

Kashyap, P., Shikha, D., Thakur, M. & Aneja, A. Functionality of apigenin as a potent antioxidant with emphasis on bioavailability, metabolism, action mechanism and in vitro and in vivo studies: A review. J. Food Biochem. 46, e13950. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfbc.13950 (2022).

Yan, X., Qi, M., Li, P., Zhan, Y. & Shao, H. Apigenin in cancer therapy: anti-cancer effects and mechanisms of action. Cell. Biosci. 7, 50. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13578-017-0179-x (2017).

Zhu, Z. Y., Gao, T., Huang, Y., Xue, J. & Xie, M. L. Apigenin ameliorates hypertension-induced cardiac hypertrophy and down-regulates cardiac hypoxia inducible factor-lα in rats. Food Funct. 7, 1992–1998. https://doi.org/10.1039/c5fo01464f (2016).

Wang, Y. et al. Apigenin exerts chemopreventive effects on lung injury induced by SiO2 nanoparticles through the activation of Nrf2. J. Nat. Med. 76, 119–131. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11418-021-01561-7 (2021).

Rahimi, A., Alimohammadi, M., Faramarzi, F., Alizadeh-Navaei, R. & Rafiei, A. The effects of apigenin administration on the Inhibition of inflammatory responses and oxidative stress in the lung injury models: a systematic review and meta-analysis of preclinical evidence. Inflammopharmacology 30, 1259–1276. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10787-022-00994-0 (2022).

Cai, M. et al. Insights into Diosgenin against inflammatory bowel disease as functional food based on network Pharmacology and molecular Docking. Heliyon 10, e37937. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e37937 (2024).

Lu, D., Huang, L. & Weng, C. Unveiling the novel Anti - Tumor potential of Digitonin, a steroidal Saponin, in gastric cancer: A network Pharmacology and experimental validation study. Drug Des. Devel Ther. 19, 2653–2666. https://doi.org/10.2147/DDDT.S504671 (2025).

Gu, Y. et al. Therapeutic effect of Shikimic acid on heat Stress-Induced myocardial damage: assessment via network Pharmacology, molecular Docking, molecular dynamics Simulation, and in vitro experiments. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 17, 1485. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph17111485 (2024).

Zhou, J. et al. Network Pharmacology combined with experimental verification to explore the potential mechanism of naringenin in the treatment of cervical cancer. Sci. Rep. 14, 1860. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-52413-9 (2024).

Shannon, P. et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 13, 2498–2504. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.1239303 (2003).

Nigro, M., Laska, I. F., Traversi, L., Simonetta, E. & Polverino, E. Epidemiology of bronchiectasis. Eur. Respir Rev. 33, 240091. https://doi.org/10.1183/16000617.0091-2024 (2024).

Mac Aogáin, M., Dicker, A. J., Mertsch, P. & Chotirmall, S. H. Infection and the Microbiome in bronchiectasis. Eur. Respir Rev. 33. https://doi.org/10.1183/16000617.0038-2024 (2024).

Hazafa, A., Rehman, K. U., Jahan, N. & Jabeen, Z. The role of polyphenol (Flavonoids) compounds in the treatment of cancer cells. Nutr. Cancer. 72, 386–397. https://doi.org/10.1080/01635581.2019.1637006 (2020).

Kopustinskiene, D. M., Jakstas, V., Savickas, A. & Bernatoniene, J. Flavonoids as anticancer agents. Nutrients 12, 457. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12020457 (2020).

Abid, R. et al. Pharmacological properties of 4’, 5, 7-Trihydroxyflavone (Apigenin) and its impact on cell signaling pathways. Molecules 27, 4304. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27134304 (2022).

Zhou, L. et al. Luteolin alleviates oxidative stress in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease induced by cigarette smoke via modulation of the TRPV1 and CYP2A13/NRF2 signaling pathways. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25, 369. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25010369 (2023).

Ding, K. et al. The therapeutic potential of Quercetin for cigarette smoking-induced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a narrative review. Ther. Adv. Respir Dis. 17, 17534666231170800. https://doi.org/10.1177/17534666231170800 (2023).

Rönnstrand, L. Signal transduction via the stem cell factor receptor/c-Kit. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 61, 2535–2548. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-004-4189-6 (2004).

Nicholson, K. M. & Anderson, N. G. The protein kinase B/Akt signalling pathway in human malignancy. Cell. Signal. 14, 381–395. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0898-6568(01)00271-6 (2002).

Hers, I., Vincent, E. E. & Tavaré, J. M. Akt signalling in health and disease. Cell. Signal. 23, 1515–1527. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cellsig.2011.05.004 (2011).

Heron-Milhavet, L., Khouya, N., Fernandez, A. & Lamb, N. J. Akt1 and Akt2: differentiating the Aktion. Histol. Histopathol. 26, 651–662. https://doi.org/10.14670/HH-26.651 (2011).

Duggal, S. et al. Defining the Akt1 interactome and its role in regulating the cell cycle. Sci. Rep. 8, 1303. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-19689-0 (2018).

Vafadari, B., Salamian, A. & Kaczmarek, L. MMP-9 in translation: from molecule to brain physiology, pathology, and therapy. J. Neurochem. 139 Suppl 2, 91–114. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnc.13415 (2016).

Huang, H. Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) as a cancer biomarker and MMP-9 biosensors: recent advances. Sens. (Basel). 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/s18103249 (2018).

Gajewska, B. & Śliwińska-Mossoń, M. Association of MMP-2 and MMP-9 polymorphisms with diabetes and pathogenesis of diabetic complications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 10571. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms231810571 (2022).

Kolaczkowska, E., Arnold, B., Opdenakker, G. & Gelatinase B/MMP-9 as an inflammatory marker enzyme in mouse zymosan peritonitis: comparison of phase-specific and cell-specific production by mast cells, macrophages and neutrophils. Immunobiology 213, 109–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imbio.2007.07.005 (2008).

Chalmers, J. D. et al. Neutrophilic inflammation in bronchiectasis. Eur. Respir Rev. 34, 240179. https://doi.org/10.1183/16000617.0179-2024 (2025).

Taylor, S. L. et al. Matrix metalloproteinases vary with airway microbiota composition and lung function in non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 12, 701–707. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201411-513OC (2015).

Guan, W. J. et al. Sputum matrix metalloproteinase-8 and – 9 and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 in bronchiectasis: clinical correlates and prognostic implications. Respirology 20, 1073–1081. https://doi.org/10.1111/resp.12582 (2015).

Alemasova, E. E. & Lavrik, O. I. Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation by PARP1: reaction mechanism and regulatory proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, 3811–3827. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkz120 (2019).

Vuong, B. et al. NF-κB transcriptional activation by TNFα requires phospholipase C, extracellular signal-regulated kinase 2 and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1. J. Neuroinflammation. 12, 229. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-015-0448-8 (2015).

Zerfaoui, M. et al. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 is a determining factor in Crm1-mediated nuclear export and retention of p65 NF-kappa B upon TLR4 stimulation. J. Immunol. 185, 1894–1902. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1000646 (2010).

Hassa, P. O. & Hottiger, M. O. The functional role of poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase 1 as novel coactivator of NF-kappaB in inflammatory disorders. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 59, 1534–1553. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-002-8527-2 (2002).

Rosado, M. M., Bennici, E., Novelli, F. & Pioli, C. Beyond DNA repair, the immunological role of PARP-1 and its siblings. Immunology 139, 428–437. https://doi.org/10.1111/imm.12099 (2013).

Naura, A. S. et al. Reciprocal regulation of iNOS and PARP-1 during allergen-induced eosinophilia. Eur. Respir J. 33, 252–262. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00089008 (2009).

Hoesel, B. & Schmid, J. A. The complexity of NF-κB signaling in inflammation and cancer. Mol. Cancer. 12, 86. https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-4598-12-86 (2013).

Okutani, D., Lodyga, M., Han, B. & Liu, M. Src protein tyrosine kinase family and acute inflammatory responses. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 291, L129–L141. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajplung.00261.2005 (2006).

Wang, Z., Rui, T., Yang, M., Valiyeva, F. & Kvietys, P. R. Alveolar macrophages from septic mice promote polymorphonuclear leukocyte transendothelial migration via an endothelial cell Src kinase/NADPH oxidase pathway. J. Immunol. 181, 8735–8744. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.181.12.8735 (2008).

Farley, K. S. et al. Effects of macrophage inducible nitric oxide synthase in murine septic lung injury. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 290, L1164–L1172. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajplung.00248.2005 (2006).

Hellmann, J. et al. Atf3 negatively regulates Ptgs2/Cox2 expression during acute inflammation. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 116–117, 49–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2015.01.001 (2015).

Ruan, Z., Wang, S., Yu, W. & Deng, F. LncRNA MALAT1 aggravates inflammation response through regulating PTGS2 by targeting miR-26b in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Int. J. Cardiol. 288, 122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2019.04.015 (2019).

Hata, A. N. & Breyer, R. M. Pharmacology and signaling of prostaglandin receptors: multiple roles in inflammation and immune modulation. Pharmacol. Ther. 103, 147–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2004.06.003 (2004).

Smyth, E. M., Grosser, T., Wang, M., Yu, Y. & FitzGerald, G. A. Prostanoids in health and disease. J. Lipid Res. 50 Suppl, 423–S428. https://doi.org/10.1194/jlr.R800094-JLR200 (2009).

Perea, L., Faner, R., Chalmers, J. D. & Sibila, O. Pathophysiology and genomics of bronchiectasis. Eur. Respir Rev. 33, 240055. https://doi.org/10.1183/16000617.0055-2024 (2024).

Zhang, B., Leung, P. C., Cho, W. C. S., Wong, C. K. & Wang, D. Targeting PI3K signaling in lung cancer: advances, challenges and therapeutic opportunities. J. Transl Med. 23, 184. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-025-06144-8 (2025).

Perea, L. et al. Airway IL-1β is related to disease severity and mucociliary function in bronchiectasis. Eur. Respir J. 64, 2301966. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01966-2023 (2024).

Giam, Y. H., Shoemark, A. & Chalmers, J. D. Neutrophil dysfunction in bronchiectasis: an emerging role for immunometabolism. Eur. Respir J. 58, 2003157. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.03157-2020 (2021).

Johnson, E., Long, M. B. & Chalmers, J. D. Biomarkers in bronchiectasis. Eur. Respir Rev. 33, 230234. https://doi.org/10.1183/16000617.0234-2023 (2024).

Klann, K. et al. Growth factor receptor signaling Inhibition prevents SARS-CoV-2 replication. Mol. Cell. 80, 164–174e164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2020.08.006 (2020).

Catanzaro, M. et al. Immune response in COVID-19: addressing a Pharmacological challenge by targeting pathways triggered by SARS-CoV-2. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 5, 84. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-020-0191-1 (2020).

Shichijo, T. & Yasunaga, J. I. Human T-cell leukemia virus type I: modulation of viral gene expression and perturbation of host signaling pathways lead to persistent infection. Curr. Opin. Virol. 73, 101480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coviro.2025.101480 (2025).

Bakhanashvili, M. The role of tumor suppressor p53 protein in HIV-Host cell interactions. Cells 13, 1512. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells13181512 (2024).

Desmet, C. et al. Selective Blockade of NF-kappa B activity in airway immune cells inhibits the effector phase of experimental asthma. J. Immunol. 173, 5766–5775. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.173.9.5766 (2004).

Barnes, P. J. Inflammatory endotypes in COPD. Allergy 74, 1249–1256. https://doi.org/10.1111/all.13760 (2019).

Jia, X. et al. Quercetin attenuates Pseudomonas aeruginosa-induced acute lung inflammation by inhibiting PI3K/AKT/NF-κB signaling pathway. Inflammopharmacology 32, 1059–1076. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10787-023-01416-5 (2024).

Guo, X., Pan, X., Wu, J., Li, Y. & Nie, N. Calycosin prevents IL-1β-induced articular chondrocyte damage in osteoarthritis through regulating the PI3K/AKT/FoxO1 pathway. Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. Anim. 58, 491–502. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11626-022-00694-7 (2022).

Zhang, S. et al. Network pharmacology, molecular docking, and experimental verification reveal the mechanism of Yi-Shen-Hua-Shi granules treating acute kidney injury. J. Ethnopharmacol. 343, 119320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2025.119320 (2025).

Sun, X., Chen, L. & He, Z. PI3K/Akt-Nrf2 and Anti-Inflammation effect of macrolides in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Curr. Drug Metab. 20, 301–304. https://doi.org/10.2174/1389200220666190227224748 (2019).

Barnes, P. J. Oxidative stress-based therapeutics in COPD. Redox Biol. 33, 101544. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2020.101544 (2020).

Ahmed, S. M. U., Luo, L., Namani, A., Wang, X. J. & Tang, X. Nrf2 signaling pathway: pivotal roles in inflammation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 1863, 585–597. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbadis.2016.11.005 (2017).

Kim, J. K. & Park, S. U. Recent insights into the biological functions of apigenin. EXCLI J. 19, 984–991. https://doi.org/10.17179/excli2020-2579 (2020).

Chen, Y. F. et al. Bronchiectasis and increased risk of ischemic stroke: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 12, 1375–1383. https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S126102 (2017).

Navaratnam, V. et al. Bronchiectasis and the risk of cardiovascular disease: a population-based study. Thorax 72, 161–166. https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-208188 (2016).

Kwok, W. C. et al. Severe bronchiectasis is associated with increased carotid intima-media thickness. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 24, 457. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-024-04129-x (2024).

Al Shaal, L., Shegokar, R. & Müller, R. H. Production and characterization of antioxidant apigenin nanocrystals as a novel UV skin protective formulation. Int. J. Pharm. 420, 133–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.08.018 (2011).

Vo, C. L. N., Park, C. & Lee, B. J. Current trends and future perspectives of solid dispersions containing poorly water-soluble drugs. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 85, 799–813. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpb.2013.09.007 (2013).

Karim, R. et al. Development and evaluation of injectable nanosized drug delivery systems for apigenin. Int. J. Pharm. 532, 757–768. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2017.04.064 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Key Research Program of Guangxi Science and Technology Department (grant number AB21196010); Joint Project on Regional High-Incidence Diseases Research of Guangxi Natural Science Foundation under Grant No.2023GXNSFBA026146; the Health and Family Planning Commission of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, Self-funded Projects (grant No.Z-A20240492、Z-A20240515); National Science Foundation of China (grant numbers 82104499, 82160783,82560016); Bethune Charitable Foundation (BCF-QYWL-HX-2025-12).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Haizhu Huang, Jiahui Han. Formal analysis: Haizhu Huang, Jiahui Han, Chongxi Bao. Methodology: Haizhu Huang, Jiahui Han, Yanping Liu, Qinzhe Zhang, Yun Jiang. Software: Haizhu Huang, Jiahui Han, Yue Zhou. Validation: Haizhu Huang, Jiahui Han, Shaochu Zheng. Visualization: Haizhu Huang, Jiahui Han, Yanping Liu. Writing - original draft: Haizhu Huang, Jiahui Han, Yanping Liu, Qinzhe Zhang, Cao Qing, Wei Lu, Xiaopu Wu, Liangming Zhang. Writing-review & editing: Haizhu Huang, Jiahui Han, Jinliang Kong, Jing Luo. Data curation: Haizhu Huang, Jiahui Han, Chuanlin Zhou, Shaochu Zheng. Funding acquisition: Jinliang Kong, Jing Luo.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, H., Han, J., Liu, Y. et al. Exploring the molecular mechanism of apigenin in treating bronchiectasis based on network pharmacology and molecular docking. Sci Rep 15, 39161 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24377-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24377-x