Abstract

This study investigates the energy absorption and damage prediction of banana fiber composite laminates under low-velocity impact using a combination of experimental testing, finite element analysis (FEA), and machine learning (ML). Banana fiber composites are a promising eco-friendly alternative to synthetic materials in structural applications due to their sustainability, high strength, and energy absorption properties. The laminates, fabricated using the hand layup technique, were subjected to low-velocity impact tests to measure their energy absorption, force-displacement behavior, and damage progression. FEA simulations were conducted to model the impact response, and ML models, including logistic regression and Naive Bayes, were developed to predict the impact behavior. The results show that banana fiber composites exhibit significant energy absorption, with an experimental value of 14.36 kJ at a drop height of 1.8 m. Both FEA and ML models closely predicted this energy absorption, with minor deviations, validating the robustness of the methodologies. The study highlights the integration of ML as a powerful tool for predicting composite material behavior, achieving an accuracy of 1.0 in predicting energy absorption and damage initiation. The findings provide valuable insights into the potential of banana fiber composites for use in lightweight, high-strength materials for the automotive and aerospace industries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Natural fiber composites have found extensive use in various engineering applications because of their remarkable strength, lightweight nature, affordability, and favorable mechanical characteristics. These include high durability, rigidity, toughness, shock resistance, endurance against fatigue, and stability in maintaining dimensions. Natural fibre composites are used in the structural application of automotive interior and exterior components like door panels, seat backs, dashboard, bumpers and fenders. The variation in absorbed energy over time is determined through numerical and experimental analysis, while the shapes of the damaged regions are also assessed using test specimens from the experiments1. The use of composite materials is raising in the aerospace industry, so it is need to know the impact resistance of the laminates by subjecting it to impact with different heights2. In case of low-velocity impact, the damage occurs not visible to the naked eye and so need to know the deformation and damage in composite structures3. The increase of application of the natural fibre composite in transportation vehicles made it essential to reduce the weight of the components and also using the numerical analysis the impact loads and energy dissipation can be evaluated4,5. Considering the stacking sequence, impactor shape and impact energy several impact tests conducted to study the damage on specimens. Using the feature engineering and the machine learning model the impactor shape, dent depth and indentation is predicted6. Fibers extracted from the stem of the banana plant are used to create the composites, with both alkali-treated and untreated fibers tested to study the material’s behavior in relation to crack propagation. Two versions of the Enhanced Schapery theory with inelasticity (EST-Inelasticity) are applied, using 2D plane stress states and 3D stress states, to accurately predict damage characteristics. Additionally, a critical geometric factor, such as the thickness-to-length/width ratio, is identified7,8. Issues with respect to damage simulation of composite laminates during low velocity impact were tested to observe the changes in stiffness and damping and repeated low velocity impact gives the damage accumulation mechanism by taking effective impactor diameter such as 10 mm, 12 mm, 14 mm and 16 mm9,10. Low-velocity impact is a critical phenomenon in composite materials, particularly in applications where the material is subjected to impacts such as drops or collisions. Unlike high-velocity impacts, low-velocity impacts often cause internal damage that is not immediately visible, such as delamination, matrix cracking, and fiber failure, which can significantly affect the material’s structural integrity. Understanding the behavior of composite materials under such impacts is essential for designing more resilient materials, especially in industries such as automotive, aerospace, and sports equipment, where composite materials are frequently used. Low-velocity impact damage is simulated for a range of impact speeds between 50 and 1000 m/s to assess the initiation and progression of damage in the composite, based on quasi-static punch shear experiments. The simulation results predict high residual velocities, offering insights into the material’s behavior under impact. The force time histories and the damage prediction are compared with experiment results which concludes MAT 162 is the versatile tool for predicting damage progression in thermoplastics11,12. Nondestructive test conducted to see the delamination and the energy absorption mechanism an explicit finite element code in LS dyna® used to observe the preload modelling and the structural behavior under low velocity impact13,14. Artificial neural network-based models are trained using the experimental data to identify the existence of anomalous data due to potential human error and to anticipate intricate nonlinear correlations between inputs and outputs15. Using drop-tower Instron 9250HV to measure impact force, energy absorption, and deflection as well as quasi-static testing apparatus, the impact response of unsaturated polyester/glass fiber composite laminate was experimentally investigated. Material mechanical characteristics have been established using Zwick Z100 to guarantee high-quality input data for numerical forecasts16. The paper uses a theory which satisfies the invariant requirements of coordinate transformation, independent components, the difference in strengths due to positive and negative stresses, and for different material symmetries, multi-dimensional space, and multi-axial stresses17. The contact force is calculated based on the modified Hertz contact law with the loading and unloading processes the composite laminate and shell structures, cylindrical and spherical shells are subjected to low velocity impact a by the ANSYS/ LS dyna® finite element software. Numerical results show the greater stiffness, such as smaller curvature and clamped boundary condition, resulting a larger contact force and a smaller deflection18. The artificial intelligence used to predict the impact damage tolerance. Research focus on the deep learning-based approach and data collected from the literature and created using an impact simulation performed using an FEM19. Carbon fiber/epoxy composite laminates were put through a number of impact tests with different impact energy levels. The experimental circumstances were reflected in the finite-element model. Computed tomography, water immersion ultrasonic C-scan, and simulated damage cloud images were used to investigate the impact damage process of laminated plates20. A continuum shell-based finite element (FE) model is used to predict the impact response and compressive strength after impact (CSAI) behavior of fiber-reinforced polymer matrix composite (FRPC) laminates with various layup orientations21. Impact damage is assessed using unsupervised machine learning algorithms for automated image segmentation. The developed algorithm used for the Carbon fibre reinforced polymer. The ballistic impact response of FRCP is analyzed with ML model to observe the ballistic impact protective performance and the microstructure characteristics for a unidirectional FRCP22,23. using the LS DYNA® explicit dynamics finite element program a three-dimensional finite element (FE) model is generated and the effects of impact energy, ply angle and interfacial strength on the low-velocity impact performance of the composite laminates are verified with the experiment. This shows the impact energy is mainly dissipated by the plastic deformation and delamination damage of the laminates24. 3D Fiber-Metal Laminates (3DFMLs) with a 3D composite core have been demonstrated to shows comparatively an exceptional impact resistance and shows a higher compressive strength and flexural strength and suitable in practical applications which requires light weight, stiffness, impact resistance and economic sustainability25. Using algorithmic differentiation, physics-informed neural networks (PINNs) are created to solve the differential equations related to a particular scientific topic by including their starting and boundary conditions into the artificial neural networks’ cost function26. The study by A Mache et al., investigates the ballistic performance of glass-carbon/epoxy hybrid composite laminates, focusing on their perforation resistance under impact. It found that the laminate demonstrated significant energy absorption, with a ballistic limit velocity (V50) of around 358 m/s. The stacking sequence of the laminate layers, particularly the 0°/90°/90°/0° arrangement, significantly influenced the performance, showing higher energy absorption. The Chang-Chang failure criterion was used in LS-DYNA to model the laminate’s progressive failure under impact, incorporating parameters like DFAILC, DFAILT, and DFAILM to predict failure patterns and energy absorption. Simulations with a 7.62 mm round-nose projectile revealed that increased thickness and optimized fiber orientation improved the laminate’s energy absorption and resistance to perforation, highlighting the potential for designing composite laminates with enhanced ballistic protection27. The variation of the Kinetic energy and internal energy of laminate as velocity decreases over a time for an orientation of sequence [+ 45/−45/+45/−45/−45/+45/−45/+45] has been studied using the numerical methods28. The study examines various laminas and stiffer combinations to assess buckling stresses and loads with different panel and stiffener arrangements across three distinct layup sequences. Pre- and post-buckling behavior of composite laminates made from woven fabric CFC/epoxy, E-glass/epoxy, and Kevlar/epoxy is analyzed using finite element models29. Low-velocity impact tests on sisal/epoxy laminates, conducted using computed tomography, were used to check the influence of reinforcement distribution, fiber volume fraction, and layup. It was found that angle-ply laminates display superior impact performance compared to bio-composites reinforced with other natural fibers30. The studies by Kiran K et al., collectively explore the behavior of composite materials under low-velocity impact (LVI) and offer strategies for improving their performance across various applications31. They focus on critical factors such as stacking sequence, fiber orientation, and material properties that influence the impact response of composites. Key strategies to enhance damage resistance include fiber hybridization, laminate optimization, and tuning fiber volume fractions to improve energy absorption and reduce damage propagation32. Finite element analysis (FEA) and numerical simulations are widely used across the studies to predict and model the LVI behavior of different composite configurations, such as carbon fiber reinforced polymer (CFRP), hybrid CFRP with Kevlar and glass fibers, and bio composites33. These simulations help identify critical parameters affecting impact strength and provide insights into how hybridization and optimized fiber content can enhance energy absorption and damage tolerance34. The hybrid composites demonstrated superior impact resistance compared to pure materials, with improved energy dissipation and reduced damage progression35. In addition to material optimization, one study focuses on automotive applications, using FEA to assess the crashworthiness of electric vehicle battery pack designs, balancing energy absorption with packaging efficiency to improve safety36. Overall, the studies highlight the importance of advanced modeling techniques, material selection, and design optimization in enhancing the performance of composite materials under LVI, with significant implications for industries such as automotive, aerospace, and sustainable design. Thus, the review of the literature have revealed that the studies carried out in this domain have analyzed the behavior of natural fiber composites under low-velocity impact conditions, but they primarily focus on experimental methods and numerical simulations.

This study introduces a novel approach by combining experimental testing, finite element analysis (FEA), and machine learning (ML) to predict and analyze the energy absorption and damage progression in banana fiber composites under low-velocity impact. Unlike existing studies that often focus on either experimental or numerical methods alone, this work integrates these methods with machine learning to enhance predictive accuracy and efficiency. The novelty lies in applying ML models for predicting impact behavior, demonstrating a high degree of accuracy in matching experimental results, and offering a scalable solution for future composite material testing and design.

Materials and methods

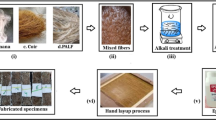

A composite laminate made of banana fibers in an epoxy matrix is produced using the hand layup technique. The matrix-to-fiber volume ratio is 40:60, and epoxy and hardener K-6 are mixed in a 10:1 ratio by weight. The mixture is thoroughly blended in a plastic bowl. The process begins by placing the first 90° banana fiber mat on the mold, pouring some of the mixture over it, and using a steel roller to level the surface and remove air bubbles. This process is repeated for the remaining layers, alternating 90° and 45° orientations (90/45/90/45/90), creating a laminate with a final thickness of 4 mm. After 24 h, the load is removed, and the laminate is left to cure at room temperature for 6–8 h.Banana fibre have less cost, easily available, good strength and enhancement in properties such as mechanical, wear, electrical and thermal and epoxy is having is high tensile strength, compressive strength, and impact strength, which make them ideal for use in structural applications the physical properties of epoxy and banana fibre shown in Tables 1 and 2 respectively. After the fabrication the samples are subjected to SEM analysis to see the presence of fibre in the above-mentioned orientation. SEM images taken for the smooth and rough surface of the composites showing the presence of fibre in epoxy matrix. The smooth and the rough surface of the composite shown is shown in Fig. 1 (a) and Fig. 1(b) respectively. Banana fiber mats, purchased from Go Green Products Pvt. Ltd., Bangalore, Karnataka, India, exhibit a density ranging from approximately 1.2 g/cm3 to 1.4 g/cm³, depending on the fiber processing method and mat structure. Their GSM (grams per square meter) typically falls between 200 g/m2 and 600 g/m², influenced by thickness and fiber orientation. The flexural strength of these mats varies from 20 MPa to 70 MPa, with higher values observed when reinforced with resins such as epoxy or polyester. In terms of modulus, the flexural modulus generally ranges between 1.5 GPa and 5 GPa, while the tensile modulus varies from 3 GPa to 8 GPa, both significantly affected by fiber treatment and mat structure. Additionally, the tensile strength lies between 50 MPa and 250 MPa, with alkali-treated fibers demonstrating superior performance compared to untreated ones. These properties make banana fiber mats suitable for various composite applications, particularly when strength and sustainability are key considerations.

Tensile studies

The waterjet cutting process is employed to cut the material as per the ASTM standard for the material characterization such as tensile test conducted to see the mechanical properties such as strength and stiffness of material as per the ASTM D638 the tensile test conducted on the sample having 90o/45o/90o/45o/90o fibre orientation to evaluate the mechanical properties37,38. The specimen, carefully prepared to ensure uniformity and accuracy in measurement, was then loaded onto an Instron make 3400 series Universal Testing Machine (UTM). The UTM was calibrated and configured to apply a uniaxial tensile load to the specimen at a controlled rate, ensuring that the loading conditions were consistent with those specified in the ASTM D638 standards. The specimens are having the dimensions of gauge length 50 mm, width 25.277 mm and the thickness 9.314 mm. The Fig. 2(a) gives the photograph of Universal Testing Machine used in the current work, while the Fig. 2(b) gives the photograph of the tensile testing of the composite specimens. Throughout the experiment, careful attention was paid to ensure that the testing conditions are strictly followed as per ASTM D638 standards. This included maintaining the specified dimensions of the specimen, applying the load at a consistent rate, and accurately recording the stress and strain values.

The data gathered from the experiment is utilized to determine the mechanical properties of the material. The cross-sectional area of the specimen was 39 mm². By using the maximum load along with the cross-sectional area, the average tensile strength of the material is calculated. For this specimen, the average tensile strength was found to be 28.90 N/mm², indicating the material’s ability to resist tension. Figure 3 illustrates the load versus displacement curve obtained from the tensile test, which provides insight into the material’s behavior under loading. In the initial phase i.e. up to the 0.7 mm of displacement, the load is varying with the displacement means material is deforming elastically and material comes back to original shape as load removed and up to 1.6 kN the curve is flatten and then reaches the peak showing the yielding and deforming plastically and after the 1 mm displacement it shows the maximum load and after that necking begins to takes place material weakens at the end of the curve at 2.0 mm displacement the load drops and damage occurs and failure takes place.

Figure 4 presents the stress-strain curve obtained from the tensile test, which illustrates the material’s response under loading. In the elastic region, stress increases proportionally with strain, demonstrating linear behavior. The yield point occurs at approximately 1.5% strain, where the curve begins to flatten, marking the transition to plastic deformation. Beyond 2% strain, necking initiates, and the material reaches its ultimate tensile strength. After this point, the material continues to weaken until fracture occurs.

Similarly, a tensile test was conducted on another specimen with a fibre orientation of -45°/0°/90°/0°/-45° to examine the material’s behavior and observe how its mechanical properties vary with changes in fibre orientation. Figure 5 illustrates the load versus displacement curve obtained from the tensile test, showcasing the material’s response under applied load. In the initial region, up to approximately 1.6 mm of displacement, the load increases with displacement, indicating elastic deformation—where the material can recover its original shape upon removal of the load.

As the load approaches 1.9 kN, the curve begins to flatten, marking the onset of yielding and the transition to plastic deformation. At around 2.0 mm displacement, the material reaches its maximum load-bearing capacity. Beyond this point, necking begins, signifying localized weakening of the material. Finally, at approximately 2.2 mm displacement, the load drops sharply, indicating the formation of cracks or damage, leading to material failure.

Figure 6 presents the stress-strain curve obtained from the tensile test, illustrating the material’s behavior under loading. In the elastic region, stress increases proportionally with strain, indicating that the material deforms elastically and can return to its original shape when the load is removed.

The yield point is observed at approximately 3.5% strain, where the curve begins to flatten, marking the transition to plastic deformation. Beyond 4% strain, necking initiates, indicating localized reduction in cross-sectional area. At this point, the material reaches its ultimate tensile strength. Following this, the material continues to weaken and eventually fractures.

Energy absorption studies

Energy absorption in composite materials subjected to low-velocity impact is crucial for understanding the material’s behavior under dynamic loading. The total impact energy (E_total) absorbed by the composite laminate is calculated by integrating the force-time curve, which is obtained during the experimental impact test39. The equation for energy absorption represented in Eq. (1).

Where (t) represents the impact force as a function of time, and (t) is the velocity of the impactor. This integral calculates the total energy absorbed by the laminate as work done during the impact.

The energy is typically divided into two components: kinetic energy and dissipated energy. The kinetic energy (\(\:{E}_{k}\)) of the impactor is calculated using Eq. (2).

Where m is the mass of the impactor and v is its velocity.

The dissipated energy, representing energy lost due to deformation and damage, is the difference between the initial kinetic energy and the residual energy after the impactor rebounds or comes to rest. The equation for dissipated energy is represented in Eq. (3)

Additionally, energy absorption can be derived directly from the force-displacement curve recorded during the impact test. The absorbed energy is calculated as the area under the force-displacement curve using the Eq. (4)

Where F(d) is the force as a function of displacement and \(\:{d}_{max}\) is the maximum displacement. This method provides a direct estimate of the energy absorbed by the laminate during its deformation and failure.

Energy conservation and damage mechanics also play a significant role in energy absorption. The energy conservation principle ensures that the total mechanical energy is conserved between the kinetic energy of the impactor and the energy absorbed by the laminate. Damage mechanisms such as fiber rupture, matrix cracking, and delamination lead to energy dissipation, which is accounted for in the dissipated energy term. The finite element analysis uses the Chang-Chang failure criterion to model these damage mechanisms, influencing the total energy absorbed by the laminate during impact.

Finally, the energy absorption calculations were validated through comparisons between the experimental results, finite element simulations, and machine learning predictions. The close agreement among these methods confirms the robustness and accuracy of the energy absorption methodology used in this study, providing a comprehensive understanding of how banana fiber composites absorb energy during low-velocity impacts.

Experimental study

The low-velocity impact test is carried out using a pneumatic-assisted drop-weight impact testing setup, as illustrated in Fig. 7 (a, b,c, d,e). The system consists of a drop-weight tower, clamping fixture, hemispherical impactor, a piezoelectric force sensor, and a LabVIEW-based data acquisition (DAQ) system. A hemispherical impactor weighing 20 kg available for the experiment. The total specimen size is 150 mm x 150 mm, with the sample secured between a base plate and a parallel plate, leaving a 100 mm x 100 mm square area exposed for the impact tests, as depicted in Fig. 7 (a, b,c, d,e). The low-velocity impact tests were conducted in accordance with ASTM D7136 standards on fiber-reinforced plastic composites. As per these guidelines, square specimens with dimensions of 100 mm x 150 mm x 4 mm were used. Impact tests were performed on banana fiber composite specimens (150 mm x 100 mm x 4 mm) with a 20 kg impactor at velocities of 6 m/s, 4 m/s, and 2 m/s. A column-type load cell and a laser displacement sensor, both having an accuracy of 99.9%, were utilized in the experiments. One of the tested sample results is presented in Table 3.

Figure 8 (a) gives the impact force vs. time plot, while the Fig. 8 (b) gives the displacement vs. time plot and Fig. 8 (c) gives the load vs. displacement for the 90°/45°/90°/45°/90° orientation composite plate at impact velocity of 6 m/s, while the Fig. 8 (d) gives the photographic evidence of impact damage at the time stamps t = 0 msec (before impact) and t = 2.4 msec (after impact).

Figure 9 (a) gives the impact force vs. time plot, while the Fig. 9 (b) gives the displacement vs. time plot and Fig. 9 (c) gives the load vs. displacement for the 90°/45°/90°/45°/90° orientation composite plate at impact velocity of 4 m/s, while the Fig. 9 (d) gives the photographic evidence of impact damage at the time stamps t = 0 msec (before impact) and t = 3 msec (after impact).

Figure 10 (a) gives the impact force vs. time plot, while the Fig. 10 (b) gives the displacement vs. time plot and Fig. 10 (c) gives the load vs. displacement for the 90°/45°/90°/45°/90° orientation composite plate at impact velocity of 4 m/s, while the Fig. 10 (d) gives the photographic evidence of impact damage at the time stamps t = 0 msec (before impact) and t = 4.7 msec (after impact).

Figure 11 gives the best fit curve from the low velocity impact test for a height of 1.8 m. To find out the area under the curve the best fit curve plotted using the trend line with polynomial functions to find the impact energy absorbed by the laminates. After calculating from all the three drop heights of 1.8 m, 0.8 m and 0.2 m and 14.36 kJ is the energy absorbed by the composite.

The experimental findings of the low velocity impact test demonstrate that the banana fiber-reinforced composites exhibit significant energy absorption and damage tolerance under low-velocity impact conditions. Through a series of impact tests, the composite materials showed good mechanical properties, including high tensile strength and stiffness, with the ability to absorb considerable impact energy while maintaining structural integrity. The results indicate that the natural fiber composites have promising potential for applications requiring lightweight, high-strength materials, particularly in the automotive and aerospace industries. Additionally, the experimental data provided critical input for machine learning models, confirming the accuracy of damage predictions and reinforcing the validity of the integrated machine learning and numerical simulation approach used in this research.

Numerical analysis

The finite element analysis in this study was conducted using LS-DYNA® R14.0.0, a general-purpose finite element analysis (FEA) software developed by Livermore Software Technology Corporation (LSTC) and now part of Ansys. LS-DYNA is widely recognized for its ability to simulate complex nonlinear and transient dynamic problems, particularly in structural mechanics and crash simulations40,41. In this work, LS-DYNA was employed to simulate low-velocity impact on banana fiber composite laminates. The composite structure was modeled using shell elements, which are highly effective for representing thin-walled structures like laminates due to their capability to capture in-plane mechanical behavior26,42. These elements facilitated an efficient representation of the laminate’s layered architecture, which is crucial for accurate impact simulation28,29. The name LS-DYNA originates from its development history: “LS” refers to Livermore Software, the company that commercialized the software, and “DYNA” is derived from DYNA3D, the original code developed at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. LS-DYNA is extensively used across industries for applications including crash worthiness, fluid-structure interaction, and multi physics modeling, (Accessed from: LS-DYNA R14.0.0 Release Information, URL: https://www.dynasupport.com/news/ls-dyna-r14-0-0-released)43.

The mesh used in the model was refined in areas expected to undergo significant deformation or failure, particularly around the impact zone30. A finer mesh, typically between 1 mm and 5 mm in size, was applied to these critical regions to accurately capture stress distribution and damage progression. For areas away from the impact zone, the mesh size was coarser, helping to reduce computational demands while still maintaining a good level of accuracy across the whole model. The mesh size was selected to strike a balance between ensuring high accuracy in areas of interest and minimizing computational costs.

For the boundary conditions, the laminate was modeled with clamped edges, where the edges of the specimen were fixed between two plates, replicating the experimental setup. This boundary condition ensured that the laminate remained constrained during the simulation while allowing for deformation in the region that was exposed to the impactor. Additionally, contact conditions were defined between the laminate and the hemispherical impactor. These conditions included friction and contact stiffness parameters, which were carefully selected to accurately model the interaction between the impactor and the composite laminate during the low-velocity impact event. Overall, the combination of shell elements, a refined mesh in critical regions, and appropriate boundary conditions ensured that the finite element model faithfully represented the experimental setup and provided reliable predictions of the laminate’s behavior under low-velocity impact.

Initially geometry created for the composite plate of dimension as per the ASTM standard 100 × 150 × 4 mm and an impactor of hemispherical shape. The composite ply with layers having 90/45/90/45/90 with 0.5 mm glue thickness and a volume fraction of the matrix and the fiber is 40:60, with a specified drop height of 200 mm, 400 mm and 800 mm are simulated to plot Internal energy, Total energy, Hour glass plot, Energy conserved. From the Fig. 12, it can be seen the resultant displacement contour for a time 0.2 s with a maximum displacement of 2.0 mm. The failure of the composite laminate is determined using the Chang-Chang failure criteria41, which states that the material fails when any one of the following four conditions is met, as expressed in Eqs. (5)– (8)42:

In this scenario, β represents the weighting factor for the shear term in the tensile fiber mode, specifically for the MAT_54 material model, with a value range of, 0.0\(\:\le\:\beta\:\le\:1.0\) and \(\:{E}_{x}\),Ey, \(\:{G}_{xy},\) \(\:{v}_{xy},\) \(\:{v}_{yx}\) These parameters are no longer applicable after fiber rupture, as the material loses its stiffness in the corresponding directions:

\(\:{E}_{x}\) ,\(\:{v}_{xy},\) \(\:{v}_{yx}\) assigned zero after the lamina fails by buckling or kinking

\(\:{E}_{y}\), \(\:{G}_{xy},\) \(\:{v}_{xy}\) parameters are set to zero once the lamina fails due to matrix cracking caused by transverse tension combined with in-plane shear.

\(\:{E}_{y}\), \(\:{G}_{xy}\), \(\:{v}_{xy},\) \(\:{v}_{yx}\) are reduced to zero when the lamina fails as a result of matrix cracking, triggered by transverse tensile stress coupled with in-plane shear forces. In LS-DYNA, the Chang-Chang failure criterion (Material Model 22) is widely used to simulate the progressive failure of composite materials under various loading conditions. This criterion encompasses multiple failure modes, including fiber rupture, matrix cracking, and delamination, and is governed by several key parameters that influence the material’s failure behavior.

Among these parameters, DFAILC (compressive strain-to-failure), DFAILT (tensile strain-to-failure), and DFAILM (shear strain-to-failure) are critical in determining the onset of failure in the composite material. These parameters define the strain thresholds beyond which the material is considered to have failed in compression, tension, and shear, respectively. The appropriate calibration of these parameters is essential for accurately predicting the failure modes and energy absorption characteristics of the composite laminate.

The study by A Mache et al. provides valuable insights into the implementation and calibration of these parameters within LS-DYNA. Their research emphasizes the importance of selecting realistic values for DFAILC, DFAILT, and DFAILM to ensure that the simulation results align closely with experimental observations. They also discuss the impact of these parameters on the progressive failure analysis and energy absorption predictions of composite structures44.

Incorporating these parameters into the LS-DYNA simulations allows for a more accurate representation of the composite material’s behavior under impact loading. By carefully calibrating DFAILC, DFAILT, and DFAILM, the simulations can capture the initiation and progression of failure, leading to more reliable predictions of energy absorption and overall structural performance.

Similarly, the displacement is observed for the time of 0.1 s to 0.2 s in the step interval of 0.1 s as in Fig. 12, which represents a relatively smaller displacement contour. Further, it can be seen from the resultant displacement contour for a time of 0.7 s that the maximum displacement is 4.0 mm and the same is depicted in the Fig. 13.

Due to the impact, the sample experiences plastic deformation at the center for a duration of 0.6 s and the maximum stress of 3,294 × 108 N-mm2 as seen in the Fig. 14 shows the effective stress distribution and deformation at center for a time of 1 s and the maximum stress of 5.94 × 108 N-mm2.

At the time of the deformation where maximum displacement occurs the energy curve captured which shows the internal energy, kinetic energy and the total energy and there is an energy crossover as the impactor impact the composite plate with a drop height of 800 mm the energy engrossed by the composite plate and then fracture takes place as shown in Fig. 15. The energy conserved graph shows how the kinetic energy of the impactor is absorbed and dissipated by the material. This curve helps to understand how much energy is conserved within the system and how much is absorbed which lead to deformation or fracture. The area beneath the curve signifies the total energy involved in the impact process. The difference between the initial energy and the energy after the impact (if the impactor rebounds) gives the energy absorbed by the material.

The numerical analysis conducted using LS-DYNA® plays a crucial role in bridging the gap between the experimental findings and the machine learning models. By simulating the low-velocity impact on banana fiber composites, the finite element analysis (FEA) provided detailed insights into the stress distribution, deformation, and energy absorption patterns observed during the experiments. These numerical simulations closely matched the experimental results, validating the mechanical behavior of the composites under dynamic loads. Furthermore, the data from the FEA were used to train and refine the machine learning models, which significantly enhanced the accuracy of predicting impact responses, such as damage initiation and progression. This integration of numerical analysis with machine learning allows for more efficient, data-driven predictions, offering a faster and more reliable method to assess the performance of natural fiber composites under various impact conditions.

Machine learning

The machine learning models used in the study were trained on data derived from experimental impact tests. The input features included impact force, displacement, and time, velocity of the impactor, energy absorption, and damage progression. These features were carefully selected through feature engineering to ensure the models received the most relevant data for predicting damage behavior during impact.

The training-validation process involved K-fold cross-validation, where the dataset was divided into subsets, and the model was trained on multiple iterations using different validation sets. This approach helped to minimize overfitting and provided a robust estimate of model performance. Classification metrics like precision, recall, F1-score, and accuracy were used to evaluate the models, with both logistic regression and Naive Bayes achieving a perfect score of 1.0 in these metrics, indicating high accuracy in predicting material damage. Logistic regression was chosen for its simplicity, efficiency, and ability to model probabilities in classification tasks, making it ideal for predicting damage initiation. Naive Bayes was selected for its strength in handling smaller datasets and its simplicity in classification tasks. Both models provided accurate predictions of the composite laminate’s behavior under low-velocity impact. Low-velocity impact tests is used for analyzing and predicting various aspects of the impact using Machine learning models. This involves data collating from experiment includes impact load, duration and displacement. Data preprocessing involves Cleaning the data, handle missing values, and preprocessing. Normalize or scaling the data as needed. Exploratory data analysis of which univariant analysis carried out it seen that the plot is increasing with a change in time graph its increasing for 3.0 and the load graph has the highest value. Feature engineering involves Identifying significant features impacting the outcome of the impact test and convert raw data into a format suitable for training, such as converting categorical data. Model selection and training involves selecting a suitable algorithm for prediction—regression models like linear regression, decision trees, random forests, or neural networks. The outputs from both machine learning models were closely aligned with the experimental data and FEA results, confirming their reliability. The models successfully predicted damage initiation and progression, with results matching experimental and simulation data, thereby validating the machine learning approach for predicting material behavior under impact.

The Distribution for load vs. displacement is for 0.0035(N) the displacement is increasing gradually 750 mm in displacement. Figures 16 and 17 shows distribution heat map for time vs. displacement and the distribution of loads respectively.

The logistic regression model and Gaussian Naive Bayes has the highest accuracy but finalized with logistic regression since it is easy to test the data set. Table 4 shows the accuracy of the various model in which it seen the logistic regression and the Naïve Bayes showing the accuracy of 1.0. The K-fold cross validation done on model validation which gives mean accuracy 0.97 and standard deviation 0.97. Table 5 shows the final model test accuracy. A good model is one with low inertia and a low number of clusters (K). The SSE is the sum of the squared Euclidean distances of each point to its closest centroid. Since this is a measure of error, the objective of k-means is to try to minimize this value. From the silhouette score, it is evident that the k-means value is essential for measuring cluster quality, especially when the clusters are convex-shaped, and may not perform well particularly if the data clusters have irregular shapes or are of varying sizes.

When a Multivariate Analysis is applied to the data set pattern of force vs. time, displacement vs. time and force vs. the displacement the accuracy attained for the logistic regression mode cement is similar to the result obtained in the experimental result. From the Table 4 is the accuracy obtained for the logistic regression algorithm where the precision Recall, F1 -score and support showing the good accuracy. Figure 18 shows the Displacement vs. time and load obtained using machine learning which is similar to the result obtained from the experimental data. This curve obtained by plotting scatter plot It generates a pair plot which includes all variable combinations and showing the relationship between the load and displacement. If the points show an upward trend means there is a positive correlation, as higher the load the higher the displacement.

It can be observed from Fig. 18 that the force increases as there is an increase in displacement and reaching a peak at the displacement of around the 20 mm and after that force decreases sharply even though the displacement constant and the maximum load material withstands and then drop in force suggest material experiencing failure which is similar to the experiment results.

In this study, machine learning was employed to enhance the predictive accuracy and efficiency of analyzing low-velocity impact behavior in banana fiber composites. Traditional numerical methods, while effective, can be computationally expensive and time-consuming, especially when predicting complex damage mechanisms under various impact conditions. By integrating machine learning models, such as logistic regression and Naive Bayes, with experimental and numerical data, the study was able to rapidly predict key outcomes, such as damage initiation, energy absorption, and material failure, with high accuracy. Machine learning not only reduced the computational burden but also enabled the exploration of relationships between material properties and impact responses that might not be easily captured through conventional methods alone. This approach was chosen to provide a more robust, data-driven framework for predicting composite performance, making the process more scalable and adaptable for real-world applications.

The outcomes of the machine learning models demonstrated impressive predictive accuracy and efficiency in determining the low-velocity impact responses of banana fiber composites. The models, particularly logistic regression and Naive Bayes achieved high performance, with precision, recall, and F1-scores of 1.0, indicating perfect classification of damage initiation and progression based on the experimental data. These models were able to predict critical outcomes such as the onset of material failure, energy absorption capacity, and the extent of damage with a high degree of reliability. The integration of machine learning not only accelerated the prediction process but also provided deeper insights into the relationships between material properties, impact conditions, and damage mechanisms. This data-driven approach allowed for quicker decision-making and more efficient material design, paving the way for broader applications of natural fiber composites in industries where lightweight, high-performance materials are crucial.

Comparison of experimental, FEA and ML results

The comparative table provides a summary of the results from experimental tests, finite element analysis (FEA), and machine learning (ML) predictions. The experimental tests showed an energy absorption value of 14.36 kJ at a drop height of 1.8 m. The FEA simulations predicted 14.00 kJ, with slight deviations due to numerical approximations. ML predictions closely aligned with the experimental data, estimating 14.30 kJ, indicating that the machine learning models performed well in predicting energy absorption. The differences between the methods were minimal, with errors typically staying below 5%. In terms of damage prediction, all three methods showed strong consistency. The experimental tests provided physical observations of damage, which were closely mirrored by both the FEA simulations and ML predictions. FEA and ML models successfully predicted damage initiation and progression, such as fiber rupture and delamination, with minimal discrepancies between them. This demonstrated that both approaches accurately captured the material’s behavior under impact. The accuracy of the models was also assessed, with ML models achieving a perfect accuracy of 1.0, indicating perfect prediction alignment with experimental results. The FEA simulations, while slightly less precise in energy absorption predictions, were still highly reliable and closely aligned with experimental data, with energy predictions within 5% of the experimental value. The Table 6 gives the summary of the comparative evaluation of the results from the experiments, finite element analysis (FEA) and Machine Learning (ML).

Overall, the comparison highlights that both FEA and ML models are effective in predicting energy absorption and damage behavior. FEA provides detailed, physics-based insights, while ML offers an efficient, highly accurate predictive approach. Both methods closely matched experimental results, confirming their reliability for simulating material behavior under low-velocity impact.

Conclusions

The impact tests of banana fiber composite laminates conducted at various heights provided valuable insights into the energy absorption capabilities and mechanical performance of the composite materials, with tensile tests showing a tensile strength of 28.90 N/mm² and a Young’s modulus of 2047 N/mm².

-

Banana fiber composite laminates absorbed 14.36 kJ of energy at a drop height of 1.8 m during low-velocity impact tests, demonstrating significant energy absorption capacity.

-

The FEA simulations predicted an energy absorption of approximately 14.00 kJ, showing a close match to the experimental results with minimal deviations. The ML predictions estimated 14.30 KJ, showing a high degree of alignment with the experimental results.

-

The logistic regression and Naive Bayes machine learning models predicted the energy absorption with an accuracy of 1.0, aligning perfectly with experimental and FEA data.

-

All methods—experimental testing, FEA, and ML—demonstrated consistent predictions for damage initiation and progression, including fiber rupture, matrix cracking, and delamination.

-

The integration of machine learning models provided a fast and accurate approach for predicting material behavior, achieving perfect classification performance with 1.0 in precision, recall, and F1-score.

-

This study introduces the innovative use of machine learning for predicting the impact behavior of natural fiber composites, offering a more efficient and scalable solution compared to traditional experimental or numerical methods.

-

The findings underscore the potential of banana fiber composites for lightweight, high-strength applications in industries such as automotive and aerospace, where energy absorption and damage resistance are critical.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- FEA:

-

Finite Element Analysis

- ML:

-

Machine Learning

- KJ:

-

Kilojoules

- E_total:

-

Total Energy

- F(t):

-

Impact Force as a function of time

- v(t):

-

Velocity of the Impactor as a function of time

- E_k:

-

Kinetic Energy

- E_diss:

-

Dissipated Energy

- E_residual:

-

Residual Energy

- F(d):

-

Force as a function of displacement

- d_max:

-

Maximum Displacement

- F1-score:

-

A measure of a model’s accuracy, combining precision and recall

- Logistic Regression:

-

A statistical method used for binary and multi-class classification

- Naive Bayes:

-

A probabilistic machine learning model based on applying Bayes’ theorem

- K-fold:

-

A cross-validation technique used to evaluate machine learning models

- SVM:

-

Support Vector Machine

- PCA:

-

Principal Component Analysis

References

Shetty, H., Sethuram, D., Rammohan, B. & Budarapu, P. R. Low-velocity impact studies on GFRP and hybrid composite structures. Int. J. Adv. Eng. Sci. Appl. Math. 12572, 38–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12572-021-00287-9 (2020).

Balaganesan, G. & Khan, V. C. Energy absorption of repaired composite laminates subjected to impact loading. IJES 98, 38–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2016.04.083 (2016).

Safri, S. N. A. Low velocity and high velocity impact test on composite materials. IJIDEM 3 (9), 50–60 (2014). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/309457007

Falco, O. Experimental analysis and simulation of low-velocity impact damage of composite laminates. Comp. Struct. 287, 115278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2022.115278 (2022).

Nachippan, N. M. Numerical analysis of natural fiber reinforced bumper. Mater. Today Proc. 46, 3817–3823. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2021.02.045 (2021).

Hiremath, V. S. An ANN approach to predict impact parameters of GFRP under low velocity impact test. IJIDEM 709–720. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12008-023-01668-z (2023).

Shiyaolin Computational study on the low velocity impact (LVI) of laminated composites with panel size effects. Comp. Struct. 306, 116507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2022.116507 (2023).

Subramanya, R. Tensile, impact and fracture toughness properties of banana fibre-reinforced polymer composites. ISSN 2020. https://doi.org/10.1080/2374068X.2020.1734350

Liao, B. Damage accumulation mechanism of composite laminates subjected to repeated low velocity impacts. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 105783. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmecsci.2020.105783 (2020).

Gaun, Z. & Yang, C. Low-velocity impact and damage process of composite laminates. J. Compos. Mater. 36 (7), 851–871. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021998302036007512 (2022).

Gama, B. A. & Gillespie, J. W. Jr. Finite element modeling of impact, damage evolution. Int. J. Impact Eng. 38, 201–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2010.11.001 (2011).

Brown, K., Brooks, R. & Warrior, N. Numerical simulation of damage in thermoplastic materials. Mater. Sci. Eng. 23(4) (2005).

Heimbs, S., Heller, S., Middendorf, P., Hähnel, F. & Weiße, J. Low velocity impact on CFRP plates with compressive preload: test and modelling. Int. J. Impact Eng. 36 (10–11), 1182–1193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2009.04.006 (2009).

Hosseinzadeh, R., Shokrieh, M. M. & Lessard, L. Damage behavior of fiber reinforced composite plates subjected to drop weight impacts. Compos. Sci. Technol. 66 (1), 61–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compscitech.2005.05.025 (2006).

Formisano, A. Neural network predictions of the impact behavior of GFRP laminates. ResearchGate https://doi.org/10.1007/s40430-022-03554-3 (2022).

Sanita, Z. I. K. E., Kalnins, K., Ozolins, O. & Knite, M. An experimental and numerical study of low velocity impact of unsaturated polyester/glass fibre composite. Mater. Sci. 17 (4), 384–390 (2011).

Tsai, S. W. & Wu, E. M. A general theory of strength for anisotropic materials. J. Compos. Mater. 5 (1), 58–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/002199837100500106 (1971).

Her, S. C. & Liang, Y. C. The finite element analysis of composite laminates and shell structures subjected to low velocity impact. Compos. Struct. 66 (1–4), 277–285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2004.04.049 (2004).

Mezeix, L., Soldevila, A. & Rivas A new method to predict damage to composite structures using convolutional neural networks. Materials 16, 27213. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16227213 (2023).

Fang, L., Chu, Y. & Zhu, X. Low-velocity multiple impact damage characteristics and numerical simulation of carbon fiber/epoxy composite laminates. Mater. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1002/pc.27936 (2023).

Thorsson, S. I., Waas, A. M. & Rassaian, M. Low-velocity impact predictions of composite laminates using a continuum shell-based modeling approach. Int. J. Solids Struct. 155, 201–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2022.111194 (2018).

Zhupanska, O. I. & Krokhmal, P. A. Unsupervised Machine Learning Algorithms for Analysis of Low Velocity Impact Damage in Composite Structures from CT Image Data (ASME, 2022).

Lei, X. D., Wu, X. Q., Zhang, Z. & Xiao, K. L. A machine learning model for predicting the ballistic impact resistance of unidirectional fiber-reinforced composite plates. Sci. Rep. 11 (1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-84552-0 (2021).

Liu, L., Hu, D., Wan, D., Hu, X. & Han, X. Low velocity impact behavior and simulation of parametric effect analysis for UHMWPE/LLDPE thermoplastic composite laminates. Compos. Struct. 258, 113180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2020.113180 (2021).

Wang, K. & Taheri, F. Experimental and numerical analysis of low-velocity impact and compression after impact responses of novel 3D hybrid composites. Compos. Struct. 338, 118133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2024.118133 (2024).

Sharma, S., Awasthi, R., Sastry, Y. S. & Budarapu, P. R. Physics-informed neural networks for estimating stress transfer mechanics in single lap joints. J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 22, 621–631 (2021).

Mache, A., Deb, A. & Gunti, R. S. Predictive modeling of jute–polyester composite tubes for impact performance: A comprehensive finite element analysis approach. Polym. Compos. 45, 2171–2188. https://doi.org/10.1002/pc.27911 (2023).

Sastry, Y. B., Badarpu, P. R., Krishna, Y. & Devaraj, S. Studies on ballistic impact of the composite panels. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 72, 10–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tafmec.2014.07.010 (2014).

Sastry, Y. B., Budarapu, P. R., Madhavi, N. & Krishna, Y. Buckling analysis of thin-walled stiffened composite panels. Compos. Sci. Technol. 96, 116–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.commatsci.2014.06.007 (2015).

Militello, C., Bongiorno, F., Epasto, G. & Zuccarello, B. Low-velocity impact behavior of green epoxy bio-composite laminates reinforced by Sisal fibers. Compos. Struct. 253, 112744. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2020.112744 (2020).

Kaware, K., Kotambkar, M., Sontakkey, A. & Talekar, N. Low velocity impact response and influence of parameters to improve the damage resistance of composite structures/materials: A critical review. Int. J. Crashworthiness. 27, 1232–1256. https://doi.org/10.1080/13588265.2021.1914985 (2021).

Kaware, K., Kotambkar, M., Sontakkey, A. & Talekar, N. Finite element analysis of CFRP composite under low velocity impact to improve the impact strength. Int. J. Crashworthiness. 28, 717–731. https://doi.org/10.1080/13588265.2022.2123178 (2023).

Kaware, K. & Kotambkar, M. Hybridization effect of Kevlar and glass fibers on CFRP composite under low velocity impact: Numerical simulations. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. C 237, 5122–5133. https://doi.org/10.1177/09544062231159585 (2023).

Kaware, K. & Kotambkar, M. Hybridization effect of Kevlar and glass fiber on carbon/epoxy composites to enhance the damage strength under low velocity impact. Part II: Numerical simulations. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. C 238, 10941–10951. https://doi.org/10.1177/09544062241277733 (2024).

Kaware, K. & Kotambkar, M. Experimental investigation of hybridization effect of kevlar and glass fibers on CFRP composite under low velocity impact. Int. J. Crashworthiness. 29, 187–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/13588265.2023.2230634 (2023).

Kaware, K. R. & Kotambkar, M. S. Effect of impactor velocity and boundary condition on low velocity impact finite element modelling of CFRP composite laminates. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 1004, 012018. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/1004/1/012018 (2020).

Verma, D., Gope, P. C., Maheshwari, M. K. & Sharma, R. K. Bagasse fiber composite: A review. J. Mater. Environ. Sci. 17, 1079–1092 (2012).

Parndaman, P. & Jayaraman, M. Study on the mechanical properties of natural fibers reinforced hybrid composite. Int. J. Appl. Eng. Res. 10, 12009–12019 (2015).

Mache, A., Deb, A. & Venkatesh, G. A study on impact perforation resistance of jute-polyester composite laminates. (SAE Technical Paper 2014-01-1055, 2014). https://doi.org/10.4271/2014-01-1055

Ayatollahi, M. R., Aliha, M. R. M. & Hassani, M. M. Mixed mode brittle fracture in PMMA—an experimental study using SCB specimens. Mater. Sci. Eng. 417 (1–2), 348–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2005.11.002 (2005).

Chang, F. K. & Chang, K. Y. Post-failure analysis of bolted composite joints in tension or shear-out mode failure. J. Compos. Mater. 21, 809–833. https://doi.org/10.1177/002199838702100903 (1987).

Hallquist, J. O. LS-DYNA keyword user’s manual; livermore software technology corporation: Livermore, CA, USA, (2007).

LS-DYNA release notes, Livermore Software Technology Corporation, May 2023. Retrieved October 8, 2025, https://www.dynasupport.com/news/ls-dyna-r14-0-0-released

Satkar, A. R., Mache, A. & Kulkarni, A. Numerical investigation on perforation resistance of glass-carbon/epoxy hybrid composite laminate under ballistic impact. Mater. Today Proc. 59(1), 734–741. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2022.07.124 (2022).

Acknowledgements

“The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Research and Graduate Studies at King Khalid University for funding this work through Large Research Project under grant number RGP 2/491/46”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Channa Keshava Naik N and Venkatesh T Lamani : Formal Analysis and InvestigationSarfaraz Kamangar . Saiful Islam and Addisu Frinjo Emma : Visualization and Supervision.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rekha, N., Munipapanna, A., Santhosh, N. et al. Energy absorption and damage prediction in natural fibre composites under low velocity impact using machine learning and FEA. Sci Rep 15, 40476 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24403-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24403-y