Abstract

Image fusion is a pivotal technology that effectively integrates multimodal image information to obtain clearer imaging, and it has wide applications in fields such as environmental monitoring, reconnaissance, and night vision. However, the majority of extant fusion methods neglect the issue of image degradation caused by inclement weather conditions in real-world scenarios. This results in a deficiency of clarity and detail representation of fused images in complex environments. The proposed method is an adaptive multimodal image fusion technique that is suitable for extreme scenarios, and it solves the imaging problem when the scene is affected by degraded interference. Firstly, a pre-enhancement module based on physical parameters is utilised to adaptively enhance the degraded image. The primary objective is to execute preliminary filtration of deleterious interference in the input degraded image. Subsequently, a gate-based sparse expert mixing mechanism was introduced, guided by degraded text descriptions generated by large visual-language models. This method facilitates the establishment of a dynamically sparse network structure, thereby enabling the overall model to manage complex and diverse input degradation information with greater flexibility. Finally, in order to enhance fusion performance to an even greater extent, a composite loss function has been devised. This function incorporates pixel-level loss, gradient loss, reconstruction loss and mutual information loss, thereby effectively improving the modal discrimination and detail retention ability of the fused image. The experimental results demonstrate that the proposed method significantly outperforms mainstream methods on multiple public datasets and in degraded scenarios such as smog, low light, and overexposure, demonstrating superior performance in terms of image clarity and quantitative metrics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Multimodal image fusion is an important research direction in computer vision1. This technique integrates complementary information from different sensors or imaging configurations to generate fused images with richer details and higher contrast. Due to hardware limitations, images captured by a single sensor or under specific imaging conditions frequently contain only partial information about a given scene2.. For example, visible images capture scene textures and details through reflected light, providing rich visual information under adequate illumination. However, in low-light environments, the ability of visible images to present details is limited-object boundaries and features are often difficult to distinguish3.. In contrast, infrared images are formed by sensing thermal radiation from the scene, remaining unaffected by ambient lighting and relying primarily on the thermal properties of objects. As such, they have clear advantages in nighttime or low-visibility conditions, enabling distinct thermal source identification. However, infrared images typically have lower contrast, insufficient detail resolution, and lack the rich texture information of visible images, which can hinder advanced vision tasks such as detection and segmentation. By fusing infrared and visible images, their respective advantages can be effectively combined: the fused image retains the rich texture and color of visible imagery while enhancing visibility in low-light environments, thereby improving the overall image quality. Owing to its outstanding capability for information integration and strong visual performance, image fusion has been widely applied in remote sensing4, medical imaging5, target detection6, and other fields.

In recent years, deep learning (DL) methods has driven significant innovation in the field of image fusion. Autoencoders (AEs)7, convolutional neural networks (CNNs)8 and generative adversarial networks (GANs)9 are the mainstream approaches in this domain. Deep learning can automatically learn and extract complex data features, achieving more efficient and accurate multimodal information fusion. For instance, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) are widely used for feature extraction to get rich spatial information in complex scenes and thereby enhancing the detail representation capability of fused images10. And generative adversarial networks (GANs) can effectively improve image quality while reducing artifacts and noise that may arise during the fusion process through adversarial training11.

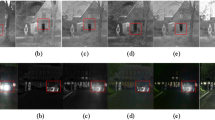

However, most existing image fusion methods are designed for ideal conditions source images and fail to adequately account for the commonly occurring problem of image degradation in real-world scenarios12. As shown in Fig. 1(a), the fused image often lacks satisfactory clarity when negative interference information is present in the scene. Although some studies have attempted to improve the quality of source images through preprocessing techniques, but these approaches typically separate the preprocessing and fusion stages. This separation results in insufficient coordination between the cascaded tasks, which can lead to error accumulation and low efficiency13.

On the other hand, some studies have attempted to construct end to end fusion models, and training them specifically for certain types of degradation in order to get the handling of degraded images during the fusion process, but their applicability remains limited for the complexity of degradation in real-world applications14. Image degradation in real scenes is highly uncertain and diverse, images captured at different times may be subject to markedly different types of degradation. For example, daytime visible images are prone to overexposure caused by strong light interference, whereas nighttime images are generally affected by low illumination and increased noise. Even at the same moment, different modalities may simultaneously suffer from multiple combined degradations, such as the coexistence of low brightness and reduced contrast. Relying on a single-task model with dedicated training would require building multiple image restoration models for different degradation combinations under such circumstances, which would significantly increase system deployment complexity and computational resource consumption. It would also raise the burden of model switching and management, because it is difficult to meet the requirements of efficient fusion in rapidly changing environments15. Moreover, due to the uncontrollable nature of image degradation, even images affected by the same type of degradation can vary greatly in severity. For severely degraded images, more intensive restoration and enhancement operations are required. But for lightly degraded images, applying a uniform fusion strategy may lead to over-restoration16. The fusion requirements of each image often differ according to its inherent characteristics. Consequently, it is necessary to develop fusion methods that can dynamically adapt to the severity of degradation, so as to produce more accurate and adaptive fusion results.

To address the above issues, we propose an adaptive multimodal image fusion method for extreme scenarios. Built upon a deep neural network, the method integrates a gated mixture-of-experts (MoE) mechanism and leverages scene degradation descriptions generated by a vision–language large model, enabling comprehensive representation of the complementary information between visible and infrared images in the feature space. Unlike traditional approaches, our model not only achieves efficient multimodal information fusion at intermediate feature layers but also incorporates mutual information loss along with multiple auxiliary loss functions, effectively enhancing the discriminability and detail representation of the fused images. Specifically, the method first performs physics-parameter-based pre-enhancement separately on the visible and infrared images. Then employs a routing mechanism to dynamically allocate expert networks based on the content and degradation severity of the input images, allowing the fusion strategy to adapt to different types and levels of degradation while balancing detail preservation and robustness. In terms of loss design, we adopt a combination of pixel-level loss, gradient loss, reconstruction loss, and other auxiliary losses to ensure that the fused results outperform single-modality images in both visual quality and structural integrity. Our approach eliminates the need to train separate models for different degradation types, it achieves adaptive handling of complex and variable degradation scenarios through a unified end-to-end framework, significantly simplifying system deployment and reducing computational resource consumption. As shown in Fig. 1(b), our method delivers a level of clarity in degraded scenarios that conventional methods fail to achieve. Overall, our contributions can be summarized as follows:

1. We pioneer the integration of CLIP-generated degradation description vectors into multimodal image fusion, introducing a gated mixture-of-experts mechanism for dynamic expert selection, which significantly enhances adaptability in degraded environments.

2. We propose a physical-parameter pre-enhancement module that incorporates real-world physical degradation patterns into deep models, substantially improving perceptual robustness under extreme conditions.

3. We design a composite loss function that balances low-level image quality and high-level semantic consistency, thereby achieving superior fusion performance across diverse scenarios.

Related work

In this section, we review image fusion, image fusion in degraded scenes and the mix of expert (MoE) techniques.

Deep learning–based multimodal image fusion methods

With the rapid development of deep learning technology, deep neural networks have gradually become the mainstream approach for handling complex visual tasks. Deep learning–driven image fusion methods can be broadly categorized into techniques based on convolutional neural networks (CNNs), generative adversarial networks (GANs), and transformers, each demonstrating unique advantages in different application scenarios.

Xu et al.17 employed a multi-layer convolutional structure combined with a channel selection mechanism to develop a multimodal image fusion model whose performance far surpasses that of traditional statistical methods. Xu et al.18 proposed U²Fusion, which integrates dense networks with information metrics to adaptively assess the importance of different modal images. Generative adversarial networks (GANs), through the adversarial interplay between discriminator and generator, can produce more refined fused images. Ma et al.19 were among the first to introduce GANs into image fusion tasks, where the discriminator supervises the generator to produce fused images with richer texture. Subsequent research further adopted dual-discriminator architectures to distinguish subtle differences between fused images and source images, such as in DDcGAN20. With the introduction of the self-attention mechanism, transformer models have achieved breakthroughs in image fusion. Wang et al.21 combined residual blocks with transformer networks to significantly improve fusion quality. Zhao et al.22 proposed a dual-branch transformer network capable of effectively handling multimodal image fusion.

In summary, deep learning based methods can automatically learn the intrinsic features and representations of data, enabling the extraction of high-level image features and overcoming the limitations of traditional approaches. These methods are capable of preserving more detail information during feature extraction and fusion, fully exploiting the complementary information between different modalities, and significantly enhancing the quality and diagnostic value of fused images.

Degraded image fusion methods

Despite the significant progress achieved by deep learning–based multimodal image fusion methods, but image degradation remains a critical challenge to be addressed. To tackle this issue, many recent studies have begun exploring ways to address degradation during the fusion process.

Early solutions for mitigating the effects of multiple degradations often adopted two stage method. For example, RDMFuse23 decouples illumination and reflectance of visible images through Retinex decomposition. Although this approach can alleviate low-light issues, but it is ineffective against noise and resolution degradation. As the development of deep learning, recent years have seen the emergence of a series of end to end models that jointly perform degradation suppression and cross-modal feature fusion within a single network. The detail-preserving and robust DAFusion24 is primarily characterized by its degradation-aware module, which dynamically identifies and suppresses various degradations to achieve simultaneous restoration and fusion. Aimed at providing clear and information-rich fusion results, even under extreme low-light and noisy conditions, the proposed Text-IF25 integrates semantic text prompts into a transformer backbone and enables fine-grained regulation of degradation suppression via text–vision interaction. In addition, DRMF26 leverages conditional diffusion priors and a composable diffusion module to simulate complex degradation distributions and jointly learn composite fusion rules.

Despite the significant progress made by the aforementioned all-in-one methods, most of them rely on synthetic quadruplet datasets or single-modality restoration corpora. As a result, they are prone to overfitting or performance degradation in real-world scenarios involving cross-modal combined degradations and domain shifts. In addition, the lack of an explicit modality–degradation decoupling mechanism limits their adaptability to novel types of degradation. To address these challenges, Section Method of this paper presents the overall fusion architecture of our proposed method, which performs degradation classification and expert routing at the feature level to achieve flexible decoupling and recombination along both modality and quality dimensions, thereby enhancing scalability and robustness.

Mixture of Experts

Mixture of Experts (MoE)6 is a deep learning architecture that improves computational efficiency by selectively activating only a subset of experts.

Recently years, the application of MoE in the field of computer vision has attracted widespread attention particularly in vision transformers (ViTs). V-MoE27 is a sparsified architecture which proposed a method to improve computational efficiency by replacing part of the dense feed-forward layers with MoE layers. Patcher28 introduced a vision transformer architecture combined with MoE to enhance segmentation accuracy. \(\hbox {M}^{3}\)ViT29 achieves efficient multitask learning through model–accelerator co-design, which integrates MoE layers into the ViT backbone to activate task-specific experts during training, and activating only the sparse expert paths relevant to the current task during inference.

These studies demonstrate the wide-ranging applications of MoE in computer vision. The introduction of MoE not only improves computational efficiency but also maintains high performance in complex vision tasks. In this study, the MoE will be extended to make it suitable for multimodal image fusion under multi-degradation scenarios.

Method

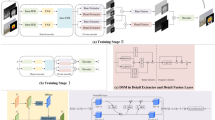

To address the unpredictable degradation commonly found in real-world images, we propose a novel degradation guided mixture-of-experts fusion network. Our framework consists of three main module. Prior Knowledge–Based Image Enhancement (PKDM) is employed to preliminarily remove degradations in the image, while the Degradation-Aware Guidance Module (DAGM) generates scene degradation vectors. And the Degradation-Guided Mixture of Experts (DGME) then utilizes the generated vectors from DAGM to guide the MoE to enhance the sparsity of the model.

Prior knowledge–based image enhancement (PKDM)

This section normalizes source images affected by various types of degradation to a more stable feature space through a series of differentiable transformations, thereby reducing the input variance that downstream MoE network need to process. The overall structure of PKDM is shown in Fig. 2.

Sequential enhancement of visible images

A visible image \(I_{\text {vis}} \in {\mathbb {R}}^{H \times W \times 3}\) will be processed through three main modules which is dehazing, low-light enhancement and deraining. The output of each module is fused with the input via a learnable weight which enables adaptive control over the enhancement strength.

Dehazing module: A CNN network \(N_{\text {dehaze}}\) is used to predict the global atmospheric light A and the scene transmission map t(x) for \(I_{\text {vis}}\). The dehazed image \(I_{\text {vis,d}}\) can be obtained:

where x denotes the pixel coordinate, \(t_0\) denotes a small positive constant which is used to clip t(x) to avoid instability caused by division by values close to zero.

Low-light enhancement module: This module adopts an iterative enhancement strategy. A CNN network \(N_{\text {lle}}\) predicts a series of parameters \(\{ R_k \}_{k=1}^N\) and enhances \(I_{\text {vis},1}\) iteratively. Let \(N = 8\):

Here, \(I_{\text {vis},L}^{(0)} = I_{\text {vis},d}\). \(\sigma (\cdot )\) is the Sigmoid function, which maps the parameter values to the range (0, 1). This iterative process ensures a gradual and stable improvement in image brightness and contrast.

Deraining module: This module aims to remove rain streaks from the image. A CNN sub-network \(N_{\text {derain}}\) is trained to predict the background (i.e., rain-free image) \(B_{\text {rain}}\). The final enhanced visible image \(I_{\text {vis}}'\) from this module is directly given by:

In our implementation, the outputs of the enhancement modules are not simply connected. Instead, We utilize a learnable weighted residual connection to fuse the output of each enhancement into the target feature stream:

Here, \(\text {Enhance}(\cdot )\) denotes an enhancement operation (e.g., dehazing), and \(\omega\) is a learnable scalar weight. This design ensures the preservation of the intensity flow path from input to output and avoids lossing intensity information. In addition, by reducing reliance on the enhancement modules (when \(\omega\) approaches \(-1\) and the enhancement effect is weak), it enables adaptive control of the enhancement strength.

Structural enhancement of infrared images

Although infrared images \(I_{\text {ir}} \in {\mathbb {R}}^{H \times W \times 1}\) are generally insensitive to illumination, they often suffer from low contrast and blurred texture details. To enhance their structural information for improved subsequent fusion, we introduce a learnable sharpening filter. This process performs residual addition based on the Laplacian of the image:

Here, \({\mathcal {L}}(\cdot )\) denotes a fixed 3\(\times\)3 convolution-based Laplacian operator, which is used to extract high-frequency edge information from the image. The sharpening strength parameter \(\lambda\) is not a fixed hyperparameter, but a learnable scalar. This allows the network, during end-to-end training, to determine the optimal sharpening strength for the current task based on the overall loss.

After this complete pre-enhancement process, we obtain a higher-quality and more feature-consistent infrared image \(I_{\text {ir}}' \in {\mathbb {R}}^{H \times W \times 1}\) and visible image \(I_{\text {vis}}' \in {\mathbb {R}}^{H \times W \times 3}\). For ease of subsequent network processing, the single-channel infrared features are duplicated across three channels, resulting in \(I_{\text {ir}}' \in {\mathbb {R}}^{H \times W \times 3}\), which is then fed into the following processing pipeline.

Degradation-aware guidance module (DAGM)

This module extracts the degradation status information directly from the image content, generating a global guidance vector \(d_{\text {deg}}\). The overall structure of DAGM is shown in Fig. 3.

Degradation-Aware Guidance Based on LoRA-CLIP: The CLIP image encoder \({\mathcal {E}}_{clip}\) was fine-tuned with Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA, which updates only about 2–3% of the parameters of the CLIP vision model) prior to training larger models, because the representation capacity of small models is limited. We use this approach to adjust CLIP attention to degradation features with few parameters. Thus, the module enhances the image and extracts high-level features as follows:

Here, \(P_{\text {clip}}(\cdot )\) represents the standard preprocessing in CLIP, which includes resizing the image to fixed 224\(\times\)224 pixels and make it normalized. This process ensures that the single-channel infrared image \(I_{\text {ir}}\) matches the input requirements for the CLIP model. \({\mathcal {E}}_{clip}(\cdot )\) denotes our fine-tuned LoRA-CLIP encoder. The encoded features \(f_{\text {vis}}\) and \(f_{\text {ir}} \in {\mathbb {R}}^{d_{\text {clip}}}\) (with \(clip=512\)) represent the encoder output. These vectors not only contain spatial information but also represent the entire content of the image in a global manner.

Guidance Vector Generation: The extracted feature vectors are first multiplied element-wise. After that, a two-layer MLP is applied to reduce the dimension and merge the information. the result is the degradation vector \(d_{\text {deg}} \in {\mathbb {R}}^{d_{\text {text}}}\) (with \(text=512\)).

This vector, as a global and compact scene state descriptor, will be used to guide the subsequent MoE network

Degradation-guided mixture of experts (DGME)

The DGME module receives two inputs: the feature map \(F \in {\mathbb {R}}^{H \times W \times C}\) from the previous layer, and the global degradation vector \(d_{\text {deg}} \in {\mathbb {R}}^{d_{\text {text}}}\) generated in Section Degradation-Aware Guidance Module (DAGM). The overall structure of DGME is shown in Fig. 4. The overall structure is as follows, which includes two key components:

Guidance Control Mechanism: The control mechanism of the guidance is driven by the DGME strategy, which uses the global degradation vector \(d_{\text {deg}} \in {\mathbb {R}}^{d_{\text {text}}}\) to guide the fusion of the input feature map F to establish a unified expert processing strategy:

Here, the components of the route (Router Bank) are merged through a linear layer to generate \(W_g\). The main signal, which uses the global degradation vector \(d_{\text {deg}} W_g\), is normalized by the linear transformation of \(d_{\text {deg}}\), and another unique linear transformation matrix \(W_{\text {noise}}\) is used to compute N(0, 1), which represents standard Gaussian noise and helps ensure that all experts are sufficiently distributed to process different types of features. To mitigate the risk of overfitting, noise perturbation is introduced into the gating mechanism of the mixture-of-experts layer. By injecting noise during expert selection, the model avoids relying excessively on a fixed subset of experts, thereby promoting a more diverse utilization of expert networks. This stochasticity not only regularizes the learning process but also enhances the generalization ability of the model across different scenes.

Sparse Dispatcher Calculation: A sparse dispatcher based on the non-zero values of G distributes the feature map F to the active top K experts. In our work, we set \(K = 2\), where the experts are divided into three different structures (same height, same width, and different sizes). Such a model has strong ability to handle multi-scale features. Specifically, each active expert fully processes its corresponding input data. Then, the outputs from these experts are fused together. Finally, the fused result is passed back to the sparse dispatcher, which produces the final output of DGME.

Here, the operation \(\text {TopK}(\cdot )\) retains the top K values (with \(K=2\)), and after the \(\text {Softmax}\) operation, the sparse dispatcher weight \(G \in {\mathbb {R}}^{M}\) (with \(M=8\)) is formed. Then, using G and the expert layers in the expert bank, the features are processed to obtain the DGME output.

Here, \(G_e\) represents the activation weight of each expert, and \(\text {Expert}_e(F)\) denotes the processing result of the input feature F by the expert. In summary, DGME improves image reconstruction accuracy and robustness. This is achieved through its strong ability in multi-modal and multi-scale feature selection, which helps identify the most suitable expert networks. Such selection enhances image restoration precision. In addition, it also provides a more reliable feature foundation for following high-level vision tasks.

In this work, CNN is adopted to construct \(E_n\) within DGME, as it offers advantages in extracting low-level features such as edges and textures, which are particularly critical for image fusion under degraded scenes. Meanwhile, compared with Transformer or Mamba-based approaches, CNN demonstrates higher computational efficiency, making it more suitable for resource-constrained scenarios. Overall, CNN provides an efficient and practical solution, whereas introducing Transformer or Mamba architectures may enhance the quality of fused images to some extent, but at the cost of significant computational overhead.

Overall structure of the fusion network

The core fusion network follows a multi-scale mixture-of-experts design built on the U-Net framework. It adopts an encoder–decoder structure that extracts, merges, and reconstructs features at several semantic levels. The overall network structure is illustrated in Fig. 5. First, DGME utilizes the visible and infrared inputs to obtain a scene degradation vector. Next, this degradation vector is fed into DGME to generate the activation gates for the experts. Then, the visible and infrared images are initially processed by PKDM for preliminary degradation removal, after which they are passed into a dual-branch network constructed with DGME to generate the fused image, the degradation-free visible image, and the degradation-free infrared image. During training, supervision on the fused image ensures that the overall network learns the knowledge of multimodal information fusion, while supervision on the degradation-free visible and infrared images ensures that the fused image retains more information from the inputs.

At the beginning, the degraded visible and infrared images are sent into PKDM for basic enhancement. The enhanced results are then passed to the DGME module, where features are adaptively extracted. A downsampling layer is used here, which reduces the feature resolution. This step lightens the computation and at the same time enlarges the receptive field. This process is applied across four layers, while the DGME layers keep the feature shape unchanged. The downsampling layer reduces the feature resolution by half and increases the number of feature channels by a factor of 4. Both the visible and infrared branches share the same structure for feature extraction. Let the degraded visible image feature at layer 1 and the degraded infrared image feature at layer 1 be denoted as \(F_{\text {vis}}^l\) and \(F_{\text {inf}}^l\), respectively. Formally, the process can be written as:

Here, \(F^{l}_{inf} \in {\mathbb {R}}^{2^{l} \cdot \frac{H}{2^{l}} \cdot \frac{W}{2^{l}}}\) and \(F^{l}_{vis} \in {\mathbb {R}}^{2^{l} \cdot \frac{H}{2^{l}} \cdot \frac{W}{2^{l}}}\), where H and W mean the height and width of the features. After feature extraction from the visible and infrared images, the extracted multi-layer, multi-modal features are concatenated to obtain the fused features. This process can also be expressed as:

Here, \(\text {concat}()\) denotes the operation of concatenating along the channel axis. After obtaining the multi-layer fused features, they are used to form the fused image, which consists of the enhanced visible image and the enhanced infrared image. The fusion of the images is achieved through three consecutive DGME layers and downsampling layers, followed by the use of three different scales to obtain different output results. The DGME layers do not change the shape or resolution of the features, while the downsampling layers reduce the resolution of the features to half the original resolution and expand the number of feature channels by a factor of 4. The fused feature at the first layer is defined as \(F_f^1\), and the above fusion process can be formulated as:

Here, \(F^{l}_{f} \in {\mathbb {R}}^{2^{l} \cdot \frac{H}{2^{l}} \cdot \frac{W}{2^{l}}}\), where the definition of the layer number here is consistent with that in the feature extraction part. Finally, the fused features are fed into three different convolutional layers for the final channel mapping, yielding the reconstructed clean visible image, clean infrared image, and the fused image as the outputs of the overall model. Meanwhile, it should be noted that the reconstructed visible and infrared images are only used for the computation of the loss function.

Multiple loss functions

We design a multi-loss function to optimize our framework, which is defined as \(L_{\text {total}}\). This loss guides the network to adapt to the fusion strategy as well as preserve key information from the source images. The total loss itself consists of the following components: fusion quality loss, confidence preservation loss, and expert (MoE) auxiliary losses. The overall loss function is:

where \(\alpha (\cdot )\) represents the weight parameters for each loss, used to balance the significance of each term during optimization.

Fusion quality loss

This loss component directly applies to the final generated f, ensuring that both the image strength and structural details are optimized to meet high-quality standards.

Strength Loss: When solving the problem of highlighting prominent objects in the fused image(such as high-temperature regions in infrared or bright regions in visible images), we maximize the strength information in the fusion result. This loss is calculated through the L1 norm as the difference between the fused image f and the maximum pixel values in the corresponding regions of the source images (\(I'_{vis}\) and \(I'_{ir}\)):

where \(\Vert \cdot \Vert _1\) means the L1 norm, and the goal is to ensure that the fused image covers the most significant features in the target region of interest(ROI).

Gradient Loss: Similarly, we employ a comparable strategy to preserve the strongest gradient information during fusion, since gradients correspond to image edges. This loss is defined as:

where \(\nabla\) represents the Sobel gradient operator. We believe that this design preserves the essential details from each source image in the fused result.

Information preservation constraint

Reconstruction Loss: Following this idea, we added a reconstruction task because it helps prevent modality collapse, where one source image could be completely ignored. This task requires the network to be able to reconstruct the original source images \({\hat{I}}_{vis}\) and \({\hat{I}}_{ir}\) from the final fused features through an independent decoding branch. The loss function is defined as:

This design forces the network to preserve sufficient modality-specific information from the input in its intermediate layers. This ensures the completeness of the fusion. Note that the same formula works when the input modalities are extended.

Moe auxiliary loss

Considering that the MoE module itself can be effectively and stably trained, we utilize two auxiliary losses, \({\mathcal {L}}_{load}\) and \({\mathcal {L}}_{mi}\). These losses are summed over the corresponding MoE-FFN modules in the network, denoted as \(N_{moe}\).

Load Balancing Loss:This loss prevents the gating network from favouring only a few star experts, so the others still get properly trained. This issue is called expert collapse. We adopt the classical load balancing loss based on the squared coefficient of variation (CV) of the distribution of expert importance I and expert load L within a batch. For a single MoE block, the load balancing loss is defined as:

where \(\textrm{CV}()\) denotes the coefficient of variation. \({\mathcal {L}}_{load}\) is the sum of this loss over all MoE blocks.

Mutual Information Loss: The last part we need to discuss is the mutual information loss that encourages expert specialization. In our framework, the network needs to handle two different tasks: the main fusion task (\(T = t_0\)) and the auxiliary reconstruction task (\(T = t_1\)). This means our designed loss maximizes the mutual information between the expert selection variable E and the task type T(E; T), so that it encourages the model to learn distinct expert utilization strategies for different tasks. For a single MoE block, the mutual information loss is:

where I() denotes mutual information. The total mutual information loss \({\mathcal {L}}_{mi}\) is the sum of this loss over all MoE blocks in the network.

The combined auxiliary loss is expressed as:

and is added to the total loss function with a unified weight \(\alpha _{aux}\).

In addition to the noise perturbation, a load balancing loss and a mutual information loss are introduced to further reduce the risk of overfitting. The load balancing loss prevents the model from over-relying on a small subset of experts by encouraging a more uniform activation of the expert networks, thereby promoting diversity in feature learning. Meanwhile, the mutual information loss constrains the learned representations to retain informative and discriminative features while suppressing redundancy, which enhances the generalization ability of the model. Together, these losses act as regularization terms that mitigate overfitting and improve the robustness of the proposed framework.

Experiments

Experimental setup

Dataset

To comprehensively evaluate the generalization ability of the proposed method, four mainstream publicly available infrared-visible image fusion datasets are selected: MSRS, RoadScene, M3FD and LLVIP. The original images in these datasets all have varying degrees of degradation. For instance, the visible images in the LLVIP and MSRS dataset have poor brightness, some visible images in the RoadScene dataset are overexposed, and the M3FD dataset suffers from haze degradation. These datasets can adequately test the robustness of the algorithm under various degradation scenarios.

Training details

The model is implemented in PyTorch. The proposed network consists of two training stages. In the first training phase, DAGM was trained. 100 images for each of four visible light degradation types (Fog, Low Light, Overexpose, Normal) were gathered from MSRS, M3FD and RoadScene datasets, with 300 rounds and a learning rate of 1e-4. In the second phase, the overall fusion network was trained. 3000 infrared-visible pairs with manually corrected visible light degradation labels were collected, training the network for 100 rounds with a learning rate of 1e-4. A learning rate decay of 0.99 is applied on both stage1 and stage2. The batch was set to 16 in the first training phase and 4 in the second. All methods are trained and tested on the same hardware: a 15-core Intel Xeon Platinum 8474 C CPU and an NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU with 24GB RAM.

Evaluation metrics

We evaluate image fusion performance using quantitative and qualitative metrics. Key aspects include information richness (EN, SF, AG), structural fidelity (SD), and artifact suppression (QAbf). Higher EN, SF, AG, and SD indicate better fusion, while higher QAbf reflects fewer artifacts.

Comparison algorithms

To comprehensively evaluate the fusion performance of our model under complex degradation conditions, the experiments are conducted in two stages: DF stage (Direct Fusion) compares the fusion performance without any additional restoration. The baselines include the All-in-One degradation fusion algorithm Text-IF, DRFM26 and AWFusion30, as well as eight general-purpose fusion algorithms such as CAMF31, DATFuse32, DDBFusion33, MURF34, MFI35, SuperFusion36, and SwinFusion37. RF stage (Restoration and Fusion) first applies state-of-the-art (SOTA) image restoration models for different degradation types. SCI38 for low-light visible images, PrainNet39 for de-raining and LMPEC40 for deblurring. Then feeds the restored images into all the aforementioned general fusion methods for fusion. The All-in-One methods (including our proposed method) do not perform any input preprocessing and directly reuse the fusion results from the first stage for evaluation. All comparison algorithms are executed based on their official implementations and default configurations to ensure the fairness and reproducibility of the experimental results.

Comparative experiments

Comparative experiments on the LLVIP dataset

To verify the stability of the proposed method in low-light environments, qualitative comparison experiments are conducted on the low-light scene dataset LLVIP. Figures 6 and 7 show the results of the qualitative comparison on the LLVIP dataset. The scene selected in Fig. 7 is a surveillance video captured under a bridge. It can be observed that, due to insufficient brightness, the visible image barely reveals any information hidden in the darkness. The infrared image, being more robust in extreme conditions, clearly displays pedestrian information on the zebra crossing, but it fails to show the zebra crossing information and the text on the pole. CAMF reduces scene brightness, worsening the low-light problem, while DATFuse keeps the brightness but looks blurry, with the pole text almost unreadable. DDBFusion suffers from severe brightness loss and missing colors, while MURF further aggravates this issue with weak infrared information. MFI also shows heavy brightness degradation along with infrared artifacts, whereas SuperFusion produces only an average result with poorly defined text regions. Text-IF and the proposed method both have the ability to restore brightness degradation during fusion. The fusion results are not limited by brightness degradation. In extremely dark scenes, we can still achieve clear-textured results. In comparison, the proposed method shows less color shift, more vibrant colors, and overall, richer texture details.

Figure 7 presents a comparison of fusion performance in another representative scene, further demonstrating the generalization ability of our approach. The scene reflected in Fig. 7 is a nighttime road scene captured by a traffic camera. For the visible image, only a blurry zebra crossing can be seen, with little to no pedestrian information visible. The infrared image clearly shows pedestrian information but lacks color information and background details that do not emit thermal radiation. Several conventional fusion methods struggle to restore the brightness degradation in the visible image during the fusion process, which limits the performance of the fused image. Both the proposed method and Text-IF can enhance the scene brightness during the fusion process, resulting in more accurate environmental perception. In contrast, the proposed method, with the help of accurate color information, achieves better visual effects.

We conducted extensive experiments on the LLVIP dataset to compare multiple infrared and visible image fusion methods, and the performance results are summarized in Table 1. The analysis based on multiple evaluation metrics shows that the proposed method has a significant advantage in overall performance.

Comparative experiments on the M3FD dataset

The stability of the proposed approach under rainy scenarios was evaluated through comparative experiments on the M3FD dataset. Figure 8 presents the results of the visual effect comparison on the M3FD dataset. As shown in the figure, the visible image is severely disturbed by water vapor, which limits its visibility. The infrared image exhibits stable imaging in rainy conditions but lacks color information and background details that do not emit thermal radiation. During the fusion process, CAMF experiences a brightness degradation issue while DATFuse amplifies the water vapor information, which does not improve the visibility of the fused image. DDBFusion suppresses some water vapor during fusion, but the colors of the fused image suffer noticeably. MURF effectively reduces water vapor, yet restoration of degraded areas remains weak. MFI, in contrast, tends to amplify water vapor. SuperFusion neither removes nor enhances it, leading to average visual results. TextIF can restore degraded regions, but water vapor persists and noticeable artifacts remain. In brief, the proposed method effectively corrects the rain degradation information during fusion, and the fused image contains no water vapor information, with significantly enhanced infrared details and better visual effects.

An additional set of images with artificial smoke was selected for fusion performance comparison. As shown in Fig. 9(a), only nearby grass information and distant building details are visible. In the comparative experiments, other methods suffer from color loss, artifacts, or incomplete smoke removal. The proposed method, in contrast, effectively removes slight smoke in the ground area. Infrared information is well preserved, and grass colors remain clear. These results demonstrate the robustness of the proposed method under smoky conditions.

The performance comparison of the proposed method with similar approaches is summarized in Table 2, showing that it consistently outperforms existing methods across multiple quantitative metrics. Specifically, in terms of clarity (AG), the proposed method achieves 7.9315, a 25.8% improvement over the highest competing method, TextIF (6.3028), indicating a significant advantage in detail clarity in the fused image. For the information entropy (EN) metric, the proposed method achieves 7.1218, which is significantly higher than that of SwinFusion (6.3406) and TextIF (6.4684). This means the fused image have the ability to save more source image information. In terms of spatial frequency (SF) and standard deviation (SD), which reflect texture details and contrast, the proposed method achieves 22.3913 and 43.8993, far surpassing other methods (e.g., SwinFusion (14.1257 and 23.7465)), indicating that the proposed method better enhances texture details and overall contrast. Although the proposed method performs slightly lower than some competing methods on the visual information fidelity (VIF) and mutual information (MI) metrics, its overall performance remains outstanding, especially in the significant improvements in key metrics such as AG and SD. This further confirms its superiority in the infrared and visible image fusion task.

Comparative experiments on the RoadScene dataset under normal and slightly overexposed conditions

Figures 10 and 11 show how the proposed method performs in normal scenarios on the RoadScene dataset. In the daytime road scene of Fig. 10, the visible image already reveals most of the scene, and adding the infrared image brings in extra details. CAMF and DDBFusion lose some brightness, which spoils part of the visible information. DATFuse introduces noise, making the fused image a little blurry. MURF and MFI damage visible details, and SuperFusion keeps too little infrared data, so the result almost looks like the original visible image. Compare TextIF with the proposed method: both perform well, but the proposed method shows fewer odd spots and generally looks better overall.

The proposed method was also tested on a nighttime road scene from the RoadScene dataset. Figure 11 shows how the fusion works under this circumstance. In the figure, the visible image is heavily affected by glare, but the infrared image is not affected. CAMF does well in reducing the glare, and the fused image looks acceptable. DATFuse, however, adds too much noise, making the fused image look worse. DDBFusion and MURF handle the glare fairly well. MFI loses some color, so the fused image is not very vivid. SuperFusion does not reduce the glare enough, which makes the fusion result poor. Both TextIF and the proposed method deal with the glare correctly and give good results, but the proposed method has fewer issues and looks a bit better overall.

Table 3 presents their results on the RoadScene dataset. From the experimental results, it is evident that the proposed method exhibits significant advantages in several key metrics. The proposed method achieves 5.5274 AG, a 6.9% improvement over the second-best performing method, TextIF (5.1723), indicating that the fused image retains more detail. The proposed method achieves 14.2019 SF, significantly outperforming all comparison methods, especially compared to DDBFusion (10.7936) and TextIF (12.1064), with improvements of 31.5% and 17.3%, respectively. This further demonstrates its advantage in enhancing texture details. Additionally, in the standard deviation (SD) metric, the proposed method surpasses all comparison methods with a value of 51.9902, indicating its effectiveness in enhancing image contrast. EN and MI indicate similar performance between the proposed method and others. For example, EN is 7.2226, close to TextIF’s 7.4761, and MI is 2.7135, slightly lower than SuperFusion’s 3.3142. Although the VIF metric is slightly lower than TextIF (0.6535), the proposed method still stands out for its overall balanced and excellent performance.

Comparative experiments on the MSRS dataset

To further validate the generalization capability of the proposed method, we conducted experiments on the low-resolution image fusion dataset MSRS. A representative comparison is illustrated in Fig. 12. Due to the low illumination in the scenes, the visible images suffer from poor visual quality, making it difficult to observe fine details and texture information. Several conventional fusion methods fail to properly adjust the overall brightness during the fusion process, resulting in darker fused images with unsatisfactory visual quality. TextIF achieves more accurate brightness adjustment by leveraging additional textual guidance. DRFM and AWFusion also perform brightness correction, but their enhancement remains insufficient. In contrast, our method not only provides reasonable brightness adjustment but also preserves the richest texture details, as confirmed by the quantitative results reported in Table 4. However, the fused images generated by our method are less vivid in color compared to those of TextIF, since TextIF incorporates an additional color loss to regulate image colorization. Nevertheless, the introduction of color loss may reduce the robustness of the algorithm, as erroneous color predictions can cause a rapid degradation in overall visual quality, which is evident from the comparisons on the M3FD dataset.

Robustness analysis on challenging samples

To verify the robustness of the proposed method when facing complex samples, we conducted experiments on two pairs of images with typical composite degradations. The experimental results are shown in Fig. 13. In the visible images, haze, low light, and severe halo effects around headlights coexist. The cross-degradation of the visible images significantly increases the difficulty of fusion. DATFuse and SuperFusion are not immune to such interference, resulting in fused images with heavy haze and poor visual quality, which indicates weak robustness. CAMF, DDBFusion, MURF, and MFI generate fused images without introducing excessive haze, suggesting stronger robustness against interference. TextIF, DRFM, and AWFusion are fusion algorithms equipped with degradation-removal capabilities, which perform well when dealing with a single degradation type but become limited under composite degradations. In particular, DRFM completely fails to adjust brightness during fusion. In contrast, our method effectively removes haze interference during fusion and reasonably adjusts the brightness of the fused image, demonstrating superior robustness compared to similar methods. However, some shortcomings remain, such as the incomplete removal of haze around headlights. In future work, we will focus on addressing the fusion of complex degraded samples to further enhance the robustness of the proposed method.

Ablation studies

Experiments conducted on the LLVIP dataset demonstrated the effectiveness of the proposed PKDM and DGME modules. The results of the ablation experiments are shown in Fig. 14. Removing DGME from the network caused the model to struggle with balancing multiple degradation tasks, producing generally blurry fused images. Without PKDM, the model could not adjust brightness properly, resulting in unnatural colors and lighting. These results demonstrate that both modules contribute positively to the network and confirm the effectiveness of the proposed method. Table 5 presents the results of the ablation experiments on the LLVIP dataset. The data in the table is consistent with the visual comparison in Fig. 15, further validating the effectiveness of the proposed modules.

Two-stage experiments

The proposed method is capable of performing degradation restoration during the fusion process. To demonstrate that this integrated de-degradation approach is superior to the two-stage processing method of performing restoration first and then fusion, two-stage experiments were conducted on the LLVIP and M3FD datasets.

Results of the two-stage experiment on the LLVIP dataset

The SCI algorithm was used to restore low-light visible images, which were then fused with infrared images using different methods. Figure 16 shows the visual comparison. The visible image remains almost completely dark, while the infrared image stays clear. In the two-stage experiment, most algorithms brighten the scene well. Yet, the small car in the dark can only be clearly seen in the fusion result of the proposed method. This shows that brightness enhancement alone does not guarantee effective fusion. The proposed method succeeds by integrating both tasks efficiently.

Table 6 presents the quantitative results of the two-stage experiments on the LLVIP dataset. The experimental results show that the proposed method demonstrates clear advantages in most metrics. Specifically, the proposed method achieves 10.7338 AG metric, which is 38.5% higher than the second-best result, result_mfi (7.7467), fully proving its outstanding performance in detail enhancement and texture information preservation. The proposed method achieves 32.9654 SF score, significantly outperforming SwinFusion (20.1776) and SuperFusion (23.6403) by 63.3% and 39.4%, respectively, indicating an absolute advantage in the resolution of texture details. In addition, for the standard deviation (SD) metric, the proposed method reaches 59.4139, surpassing SuperFusion (58.1386) and SwinFusion (56.6406), showing that it can better enhance image contrast and make the fused image more visually striking. For the EN metric, the proposed method achieves 7.7094, ranking among the top overall results, further demonstrating the richness of information in the fused images. Although the VIF of the proposed method (0.9985) is slightly lower than that of some methods (e.g., SwinFusion at 0.7217), its overall balance and comprehensive performance highlight its superior capability in infrared and visible image fusion tasks.

Results of the two-stage experiment on the M3FD dataset

The PReNet algorithm was selected to conduct the two-stage experiment on the M3FD dataset. The visual effect comparison of the experimental results is shown in Fig. 16. The visible image contains a large amount of raindrop interference, which was removed using PReNet before fusion. The result of CAMF shows almost no raindrop information, but the fused image loses color. Although there is no raindrop interference in the DATFuse result, it amplifies the rain and fog information in the image. DDBFusion experiences brightness degradation during fusion, making the image overall darker. The brightness degradation issue is similarly severe in MURF and MFI. TextIF introduces artifacts during fusion. SuperFusion fails to fully remove the rain and fog interference during fusion. The proposed method produces a clear image with no raindrops or rain/fog interference, achieving excellent visual effects.

Table 7 presents the results of the quantitative comparison. The data in the table show that the fusion results obtained by the proposed method achieve higher AG, EN, SF, and SD, indicating that the fused images have higher clarity. Since the proposed method not only corrects degradation but also increases the distance between the original visible image and the fused image, this results in a slight decrease in VIF and MI. However, the overall performance remains among the top.

Two-stage experiments on the RoadScene dataset

The LMPEC algorithm was applied for a two-stage experiment on the RoadScene dataset. Figure 17 shows the visual comparison. In Fig. 17(a), the visible image is blurred due to overexposure. LMPEC removed the blur before further fusion experiments. CAMF loses both brightness and color in the scene. DATFuse gives a generally good result but misses line details on the ground. DDBFusion suffers from significant brightness loss, producing a dark fused image; MURF shows similar issues. MFI keeps the brightness but the fused image is somewhat blurry and lacks local texture. TextIF, SuperFusion, and the proposed method all deliver good results. Compared with the others, the proposed method preserves more infrared information and richer local textures. Table 8 confirms its advantages in quantitative metrics.

Downstream detection task experiments

To verify the effectiveness of the proposed method in detection tasks, downstream detection experiments were conducted on the M3FD dataset based on YOLOv841. The experimental results are shown in Table 9. The performance of detection using only visible images is limited due to the presence of complex factors such as rain and fog occlusion in the environment, with an mAP50 of only 70.2%, making it difficult to meet robustness requirements. Infrared images are more stable in extreme weather and low-light conditions resulting in better detection performance. The mAP50 reaches 74.4%, which is 4.2% higher than that of visible images. Infrared images, however, lack color and texture, limiting detection accuracy. The proposed method fuses visible and infrared images and corrects degradation in the visible images. When using the fused image for detection, mAP50 rises to 81.3%, 6.9% higher than infrared images alone. Precision climbs to 86.1% and Recall to 73.1%. Overall, the fused images clearly improve detection performance, demonstrating the effectiveness of the proposed fusion method.

Figure 18 compares the detection performance of different methods. The proposed fusion method effectively integrates multispectral data and suppresses interference in the visible image. The fused image contains more information, producing accurate and complete detections. This further demonstrates the effectiveness of the proposed method in multispectral detection tasks.

Analysis of CLIP

In DAGM, we utilize CLIP to generate scene degradation vectors. CLIP consists of an image encoder and a text encoder, and through large-scale data and contrastive learning, it ensures that images and their corresponding texts can be aligned in a latent space. In this work, we fine-tune the pre-trained CLIP using LoRA to establish alignment between images and degradation description texts. Existing vision-language models, such as LLaVA and BLIP, can also achieve this functionality. However, these models have significantly more parameters and capabilities, many of which are unnecessary for the proposed DAGM. For instance, BLIP can generate detailed semantic descriptions of input images, and LLaVA can produce specific image descriptors guided by additional query texts. Moreover, compared to BLIP and LLaVA, CLIP has been extensively validated in zero-shot recognition and degradation-aware tasks, making it more suitable as general prior knowledge in our fusion framework. To illustrate the advantages of CLIP in degradation scenario recognition, Table 10 presents the accuracy and parameter sizes of different vision-language models in the task of recognizing scene degradation vectors. The data show that CLIP can generate more accurate scene degradation vectors without requiring additional query texts, and it requires the fewest parameters. Furthermore, CLIP’s encoder architecture is more compatible with LoRA, facilitating parameter-efficient fine-tuning.

To further validate the effectiveness of the degradation description vectors generated by CLIP in guiding MoE expert selection, we visualized the expert activation distributions under different degradation scenarios, as shown in Fig. 19. On the left of the figure are heatmaps of expert activations for 8-layer MoE under various degradation scenarios, where the horizontal axis represents expert indices, the vertical axis represents MoE layer indices, and the color intensity indicates the activation strength of each expert at that layer. On the right are the average activation curves of each expert across all layers for the corresponding scenarios. The results show that the expert activation distributions vary significantly across different degradation scenarios. In the fog scenario, the model tends to activate mid-index experts, indicating that these experts have learned representations better suited for handling low-contrast and blurred features. In the low-light scenario, activations are primarily concentrated in the first few experts, suggesting that the model automatically selects expert branches more sensitive to insufficient illumination. In the rain scenario, specific experts in certain layers are strongly activated, reflecting the model’s capability to adaptively model striped or local noise features. In the clean scenario, expert activations are relatively uniform, indicating that the model does not bias toward any particular expert in the absence of noticeable degradation, thereby maintaining stability in feature processing.

Conclusion

To address the insufficient adaptability of traditional multimodal image fusion methods in complex degraded scenarios, this paper proposes an adaptive image fusion framework that integrates vision-language large models with a sparse mixture-of-experts mechanism. By introducing a physics-parameter-based image pre-enhancement mechanism before fusion and employing degradation description tokens generated by CLIP to guide experts’ dynamic participation in the fusion process, the proposed method achieves flexible adaptation of fusion strategies to both the type and severity of image degradation. The designed multi-loss function further improves the detail quality and structural fidelity of the fused images during the optimization process.

The experimental results validate the broad applicability and robustness of the proposed method across different modal images and complex scenarios, but the current work focuses on several specific degradation types, while images captured by sensors may involve a wider variety of degradations beyond those considered in this study. To further enhance the generalization capability, one approach is to construct a larger-scale training dataset that covers as many degradation types as possible, another approach is to employ unsupervised training strategies to improve the robustness against unknown degradations.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available in the Image-Fusion-Network repository (https://github.com/Young-spec-design/Image-Fusion-Network/releases/tag/ImageData).

References

Hu, E. J. et al. Lora: Low-rank adaptation of large language models. ICLR 1 (2), 3 (2022).

Yang, Y., Chiang, H.-Y., Li, G., Marculescu, D. & Marculescu, R. Efficient low-rank backpropagation for vision transformer adaptation. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 36, 14725–14736 (2023).

Dong, W. Low-rank rescaled vision transformer fine-tuning: A residual design approach, in: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 16101–16110 (2024).

Zhu, Y. et al. IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI). IEEE 2024, 1–5 (2024).

Fang, Z., Wang, Y., Yi, R. & Ma, L. Dropout mixture low-rank adaptation for visual parameters-efficient fine-tuning. In: European Conference on Computer Vision, pp. 369–386 (Springer, 2024).

Shazeer, N. et al. Outrageously large neural networks: The sparsely-gated mixture-of-experts layer, arXiv preprint arXiv:1701.06538 (2017).

Ma, J., Yu, W., Liang, P., Li, C. & Jiang, J. Fusiongan: A generative adversarial network for infrared and visible image fusion. Information fusion 48, 11–26 (2019).

Li, H., Wu, X.-J. & Kittler, J. Rfn-nest: An end-to-end residual fusion network for infrared and visible images. Information Fusion 73, 72–86 (2021).

Liu, Y., Chen, X., Peng, H. & Wang, Z. Multi-focus image fusion with a deep convolutional neural network. Information Fusion 36, 191–207 (2017).

Ma, J., Chen, C., Li, C. & Huang, J. Infrared and visible image fusion via gradient transfer and total variation minimization. Information Fusion 31, 100–109 (2016).

Odusami, M., Maskeliūnas, R., Damaševičius, R. & Misra, S. Explainable deep-learning-based diagnosis of alzheimer’s disease using multimodal input fusion of pet and mri images. Journal of Medical and Biological Engineering 43(3), 291–302 (2023).

Li, Q. et al. Stabilizing multispectral pedestrian detection with evidential hybrid fusion. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology 34(4), 3017–3029 (2023).

Chen, J., Yang, L., Liu, W., Tian, X. & Ma, J. Lenfusion: a joint low-light enhancement and fusion network for nighttime infrared and visible image fusion. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 73, 1–15 (2024).

Chen, X. et al. Modeling thermal infrared image degradation and real-world super-resolution under background thermal noise and streak interference. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology 34(7), 6194–6206 (2024).

Tang, L., Yuan, J. & Ma, J. Image fusion in the loop of high-level vision tasks: A semantic-aware real-time infrared and visible image fusion network. Information Fusion 82, 28–42 (2022).

Guo, W.-Z. et al. Unsupervised degradation aware and representation for real-world remote sensing image super-resolution. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 62, 1–13 (2024).

Xu, H., Zhang, H. & Ma, J. Classification saliency-based rule for visible and infrared image fusion. IEEE Transactions on Computational Imaging 7, 824–836 (2021).

Xu, H., Ma, J., Jiang, J., Guo, X. & Ling, H. U2fusion: A unified unsupervised image fusion network. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 44(1), 502–518 (2020).

Xu, H., Ma, J., Le, Z., Jiang, J. & Guo, X. Fusiondn: A unified densely connected network for image fusion. In: Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence 34, 12484–12491 (2020).

Ma, J., Xu, H., Jiang, J., Mei, X. & Zhang, X.-P. Ddcgan: A dual-discriminator conditional generative adversarial network for multi-resolution image fusion. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 29, 4980–4995 (2020).

Wang, Z., Chen, Y., Shao, W., Li, H. & Zhang, L. Swinfuse: A residual swin transformer fusion network for infrared and visible images. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 71, 1–12 (2022).

Zhao, Z. et al. Cddfuse: Correlation-driven dual-branch feature decomposition for multi-modality image fusion. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pp. 5906–5916 (2023).

Wang, X. et al. A retinex decomposition model-based deep framework for infrared and visible image fusion. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Signal Processing (2024).

Wang, X. et al. A degradation-aware guided fusion network for infrared and visible image. Information Fusion 118, 102931 (2025).

Yi, X., Xu, H., Zhang, H., Tang, L. & Ma, J. Text-if: Leveraging semantic text guidance for degradation-aware and interactive image fusion. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 27026–27035 (2024).

Tang, L. et al. Drmf: Degradation-robust multi-modal image fusion via composable diffusion prior. In: Proceedings of the 32nd ACM International Conference on Multimedia, pp. 8546–8555 (2024).

Riquelme, C. et al. Scaling vision with sparse mixture of experts. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 34, 8583–8595 (2021).

Ou, Y. et al. Patcher: Patch transformers with mixture of experts for precise medical image segmentation. In: International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, pp. 475–484 (Springer, 2022).

Fan, Z. et al. M3vit: Mixture-of-experts vision transformer for efficient multi-task learning with model-accelerator co-design. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 35, 28441–28457 (2022).

Li, X. et al. All-weather Multi-Modality Image Fusion: Unified Framework and 100k Benchmark, arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.02090v2 (2024).

Tang, L., Chen, Z., Huang, J. & Ma, J. Camf: An interpretable infrared and visible image fusion network based on class activation mapping. IEEE Transactions on Multimedia 26, 4776–4791 (2023).

Tang, W., He, F., Liu, Y., Duan, Y. & Si, T. Datfuse: Infrared and visible image fusion via dual attention transformer. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology 33(7), 3159–3172 (2023).

Zhang, Z., Li, H., Xu, T., Wu, X.-J. & Kittler, J. Ddbfusion: An unified image decomposition and fusion framework based on dual decomposition and bézier curves. Information Fusion 114, 102655 (2025).

Xu, H., Yuan, J. & Ma, J. Murf: Mutually reinforcing multi-modal image registration and fusion. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 45(10), 12148–12166 (2023).

Wang, W., Deng, L.-J. & Vivone, G. A general image fusion framework using multi-task semi-supervised learning. Information Fusion 108, 102414 (2024).

Tang, L., Deng, Y., Ma, Y., Huang, J. & Ma, J. Superfusion: A versatile image registration and fusion network with semantic awareness. IEEE/CAA Journal of Automatica Sinica 9(12), 2121–2137 (2022).

Ma, J. et al. Swinfusion: Cross-domain long-range learning for general image fusion via swin transformer. IEEE/CAA Journal of Automatica Sinica 9(7), 1200–1217 (2022).

Ma, L., Ma, T., Liu, R., Fan, X. & Luo, Z. Toward fast, flexible, and robust low-light image enhancement. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pp. 5637–5646 (2022).

Ren, D., Zuo, W., Hu, Q., Zhu, P. & Meng, D. Progressive image deraining networks: A better and simpler baseline. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition pp. 3937–3946 (2019).

Afifi, M., Derpanis, K. G., Ommer, B. & Brown, M. S. Learning multi-scale photo exposure correction. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pp. 9157–9167 (2021).

Wang, G. et al. Uav-yolov8: A small-object-detection model based on improved yolov8 for uav aerial photography scenarios. Sensors 23 (16), 7190 (2023).

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yi Li constructed the theoretical models and algorithms under the guidance of Geer Yang, experimented with the algorithms, verified the hypotheses, and wrote the main manuscript text. Donghui Li supervised the project, provided critical revisions, finalized the manuscript, and reviewed the figures for precision and clarity. Shu Fang prepared the figures, provided the hardware equipment required for the experiment, and participated in the implementation of the algorithm and the analysis of the results. Geer Yang proposed the research framework, designed the experimental plans, and oversaw the overall research progress. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Y., Li, D., Fang, S. et al. Multimodal image fusion network with prior-guided dynamic degradation removal for extreme environment perception. Sci Rep 15, 40530 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24436-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24436-3