Abstract

Microfluidic experiments often require precise flow control, but commercial pumps and pressure regulators are costly and can limit accessibility. We introduce a calibration-based strategy that links channel geometry with predictable relationships between pressure drop (Δp) and flow rate (Q), enabling stable operation of microfluidic systems using only pressurized syringes and inexpensive tubing. Silicon–glass microfluidic chips with systematically varied channel dimensions were fabricated and tested to quantify how width, depth, and length affect hydrodynamic resistance. The results revealed consistent geometry-dependent scaling of Δp and Q, with experimental values closely matching theoretical predictions. This calibration framework allows researchers to pre-determine safe operating conditions for syringe-driven flow, preventing chip failure and connector leakage while providing reliable flow control without specialized equipment. Beyond lowering system cost, the method highlights how chip geometry dictates achievable flow regimes, offering a design tool for laboratories where commercial pumps are unavailable.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Microfluidics is a rapidly growing field that manipulates fluids at microliter or picoliter scales within channels1 or systems with micrometer and nanometer dimensions. Precise control over pressure and flow rate is critical in these systems to ensure accurate experimental conditions, reproducibility, and the proper functioning of microfluidic devices. This control is crucial in biomedical diagnostics2,3, drug delivery4, chemical synthesis5, and environmental monitoring applications6,7. The microfluidic devices used in point-of-care8,9 testing require exact control of flow rates and pressures for accurate sample manipulation, reagent mixing10, and reaction conditions. Similarly, microfluidic drug delivery systems11,12 need precise flow rate control to deliver specific dosages over set periods. Chemical synthesis in microreactors relies on stable and controlled flow rates for proper mixing and reaction kinetics, which are essential for chemical processes. Environmental monitoring applications, such as monitoring pollutants or toxins in water or air samples, depend on consistent and reliable measurements achieved through accurate flow rate control. In cellular biology, microfluidic platforms used for cell culture, sorting, and analysis need controlled flow rates to maintain cell viability and simulate physiological conditions13.

Various methods achieve precise conditions in microfluidic systems. The most common tools are syringe pumps, which deliver small fluid volumes with high accuracy14 based on syringe piston position control, typically by a stepper motor. When the user sets the flow rate, the microcontroller inside recalculates it into the motor’s rotating angle per minute, and the pump starts pumping, disregarding the pressure in the tubes. However, if the system becomes blocked, pressure builds up, potentially causing bursts. Moreover, syringe pumps can be bulky or have limited volume capacity, requiring frequent refilling or replacing syringes. Despite being moderately priced, their setup can be complex and may not be ideal for simple experiments.

Pressure controllers15 are likely the best option for precision, as they precisely regulate fluid pressure, enabling stable flow rates even with varying channel resistances. They can handle multiple channels simultaneously but require a gas supply, adding complexity and cost. These systems are significantly more expensive than syringe pumps due to their high precision and multi-channel capabilities, making them unaffordable for many scientists. Peristaltic pumps16 are the cheapest option, providing a continuous flow ideal for pumping viscous fluids or fluids with suspended particles, with the added benefit that the fluid only contacts the tubing, simplifying maintenance. However, they can introduce pulsations in the flow, which may be undesirable in applications requiring smooth flow, and their accuracy is generally lower than syringe pumps. Therefore, they are usually unsuitable for low-volume microfluidic systems but are relatively affordable.

Electroosmotic flow control allows17 for the manipulation of small volumes rapidly and is well-suited for integration with microfluidic chips. It provides uniform flow profiles but requires conductive fluids, limiting its applicability. It has been used for capillary electrophoresis, where high-voltage power supplies are typically required. However, capillary electrophoresis systems cannot be made using a Si substrate due to difficulties with Si substrate isolation, and the cost can vary widely, often reaching thousands of dollars due to the need for specialized equipment.

Costs related to pumps, accessories, tubing, and fittings often represent underestimated expenses. Prices can vary significantly, depending on the material, surface finishing, and the presence of a thread. Polyetheretherketone (PEEK) accessories are costly and usually unnecessary for applications without chemically aggressive liquids or high temperatures. Often, more affordable materials, such as silicone, poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA), polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), polyethylene terephthalate (PET), or polycarbonate, should be sufficient. Moreover, more expensive and fragile fused silica tubing may be preferred in applications requiring highly stable and pulse-free flow due to its chemical resistance and hardness, which protect the system from stretching under elevated pressure.

Precise control of pressure and flow rate is essential for reliable microfluidic operation, yet commercial pumps and regulators are often too costly or complex for many laboratories. We present a syringe-based approach that uses only inexpensive silicone tubing and hollow metal connectors to substitute for these tools. Unlike prior demonstrations of syringe-driven pressure sources, our method establishes a calibration framework that explicitly connects channel geometry with predictable flow–pressure behavior. Quantifying how width and depth dominate over length in determining flow stability allows us to provide experimentally validated limits of safe operation for syringe-driven systems.This design-oriented strategy transforms a simple, low-cost setup into a reliable calibration tool, enabling researchers to predict achievable flow regimes, prevent chip damage, and extend syringe-driven operation to applications where commercial controllers are impractical, including resource-limited laboratories, portable diagnostics, and teaching environments.

Materials and methods

Rectangular shape hydrodynamics

We first analyzed the relationship between the pressure drop (Δp) and mass flow rate (Q) in a rectangular cross-section microfluidic channel. We observed that channels with different L, W, and H dimensions corresponding to channel length, width, and depth exhibited varying hydrodynamic resistance (RH) levels, impacting the overall Δp observed. This analysis allowed us to define the ideal dimensions for controlling Q or Δp using a syringe with compressed air. According to the derived equation for hydraulic resistance, we can calculate RH as follows18:

where µ represents the dynamic viscosity of the fluid medium, and q(ε) is a shape factor defined as:

Thus, we describe the Δp by an equation:

from which we define the channel shape factor as:

Then, we can express the Q value as a function of Δp:

Here, the outcome is that given geometry having fluid with the same viscosity, the Q value is linearly proportional to the Δp, as long as the laminar flow is characterized by a Reynolds number (Re) with a value below 200019. Here, we considered laminar flow with the assumption that Re < 1000, transient flow in the range from 1000 to 2000, and turbulent flow for Re > 2000 for all cases.

We calculated the Reynolds number (Re) to characterize the flow inside fabricated structures further:

where ρ is fluid-specific mass, v is fluid medium velocity, and DH is the hydraulic diameter of the structure, calculated as:

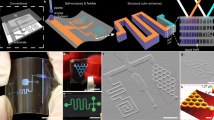

Chip design and fabrication

We used the Java-based Nanolithography Toolbox software to generate microfluidic structures (Fig. 1A)20,21. The design includes narrow microfluidic channels with varying L of (2, 4, 6, and 8) mm and W of (50, 100, 200, and 500) µm (Fig. 1B). It also includes through-holes for fluid access. Those have a diameter of 1 mm to ensure compatibility with stainless steel tubes, which have a 0.9 mm outer diameter for chip fluid control, allowing easy connection to the measuring setup.

Microfluidic channel schematic and chip layout used for investigating the relationship between a microfluidic device’s pressure drop and flow rate. (A) Cross-sectional schematic representation of the microfluidic channel with dimensions: length (L), width (W), and height (H) made of Si covered with SiO2 and glass. (B) The chip layout shows different microchannel configurations used in the experiments, varying lengths (L) and widths (W).

Our standard fabrication process uses silicon micro-machining with anodically bonded glass22,23,24. This technique employs dual deep reactive ion etching (DRIE) to form microfluidic channels and through-holes. We started with Si wafers with a diameter of ≈ 100 mm and thermally oxidized them to have a ≈ 300 nm thick SiO2 layer. The first lithography process consists of standard steps commonly used for Si-based chip fabrication: hexamethyldisilazane (HMDS) priming to enhance photoresist (PR) adhesion to the substrate, PR coating with a target thickness of 1.8 µm, pre-baking, ultraviolet light exposure, post-baking, and development, followed by SiO2 etching using reactive ion etching (RIE) and PR removal. We then used a second PR with a thickness of over 15 µm for the second lithography, followed by Si etching using DRIE to form through-holes in the Si substrate. After removing the PR, we used the SiO2 pattern in the first lithography as a mask to etch the microchannels by DRIE. Subsequently, we removed the SiO2 using a buffered oxide etch solution. After wafer cleaning, we thermally oxidized the Si to create a ≈ 5 nm SiO2 layer for defined surface termination having sufficient SiO2 thickness for surface chemistry, which still does not hinder the anodic bonding process. Finally, we anodically bonded the Si substrate to Corning glass 7440, which was developed explicitly for Si-glass bonding. The glass/Si multi-layer was then diced into individual chips using a diamond blade dicing saw25. We fabricated three wafers, each with different H values of (22.37 ± 0.41) µm, (42.50 ± 0.92) µm, and (82.26 ± 1.56) µm.

Tubing and connections are fundamental components of microfluidic chips, often representing low reliability and significantly influencing the costs of the microfluidic system. Here, we present a robust tubing approach utilizing a PMMA frame with holes to stabilize the stainless-steel tubes mounted into the Si/SiO2 chip for fluid connection. The PMMA has a milled recess to fix the Si/SiO2 chip, allowing the tubes to align with the holes in the microfluidic chip automatically. We mounted the frame with epoxy glue and stainless-steel tubes as connection ports for either silicone tubes or Luer lock termination. Both techniques are significantly cheaper than using fused silica or PEEK capillaries. Plus, the system is mechanically stabilized using the PMMA frame. We summarized the chip mounting and tubing technology in the following steps (Fig. 2).

-

(1)

We fabricated the PMMA frame using CNC machining (Fig. 2A), creating a cavity and through holes according to the chip design and ensuring a precise mounting frame for the chip.

-

(2)

We roughened the PMMA frame (Fig. 2B) to enhance the adhesion force between the chip and the PMMA, increasing the durability of the connection. Washing with propan-2-ol (known as isopropyl alcohol or IPA) and drying with compressed air is essential for optimal glue adhesion.

-

(3)

We dispensed epoxy glue, such as 3M® DP420, or a similar product with good adhesion to metal, Si, and PMMA around all ports, maintaining a distance of at least 1 mm from the hole (Fig. 2C) to avoid clogging the holes. We applied glue to larger areas without holes to improve chip adhesion to the PMMA frame.

-

(4)

Wait ≈ 10 min to allow the glue to harden partially, preventing excess glue from flowing into the channel. Then, epoxy glue mounts the chip on the bottom side of the PMMA frame (Fig. 2D).

-

(5)

Allow 24 to 48 h for the glue to harden and crosslink fully (Fig. 2E).

-

(6)

This step is optional and depends on user requirements. Install simple hollow tubes or tubes with a luer lock (Fig. 2F).

-

(7)

Use appropriate glue to mechanically fix the tubes and seal the area between them and the PMMA frame (Fig. 2G). Use the glue mentioned in point 3, then wait ≈ 48 h to ensure it reaches its maximum mechanical strength26.

-

(8)

The system is ready for experiments once the desired tubes are connected (Fig. 2H).

Fabrication process of the microfluidic device. (A) Computer numerical control (CNC) milling of holes and a recess in a PMMA substrate, forming a frame and tube holder for the Si/SiO2 microfluidic chip. (B) Cleaning and preparing the milled substrate using sandpaper, tissue, and isopropyl alcohol (IPA). (C) Applying adhesive to the milled PMMA frame using a syringe. (D) Aligning and placing a Si/SiO2 microfluidic chip over the adhesive-applied frame, followed by a ≈ 10 min curing time. (E) Allowing the assembly to cure for ≈ 24 h. (F) Setting up the cured assembly for fluid connection, with tubes and connectors in place. (G) Performing an extended 48 h curing process to ensure full adhesion and stability. (H) The final assembly of the microfluidic device is ready for experimental use.

Results and discussion

Experimental setup

We employed a setup (Fig. 3A) using two syringes each with a volume of 100 ml: one for pressurizing the system and the other for filling it with liquid, where we used DI water. Additionally, we used two reservoirs: one for filling the syringe with water and the other as an outlet for flushing the system to remove unwanted bubbles formed during flow control with pressurized air. All channels and tubing were pre-filled with DI water to avoid the system’s transient behavior when pushing out the air from the setup. Furthermore, it was essential to see that the system is bubble-free.

Testing setup and results: (A) Diagram of the experimental setup showing the air and water inlets using syringes with the volume of 100 mL, analytical balance model AS 200/X made by Radwag, and data collection system. (B) An experimental setup with the microfluidic chip and analytical balance to measure flow rate (Q) and pressure drop. (C–E) Captured mass change as a function of time for channels with different geometries. (F–H) Calculated Q as a function of channel geometry.

We filled one syringe with water at the beginning of the experiment (Phase 1). Then, we flushed the system with water from the syringe to remove bubbles (Phase 2). Then, we closed the valve between the syringes and the chip inlet tube and pressurized the system’s first part by compressing the air syringe from ≈ 100 ml to 50 ml, generating an overpressure of ≈ 100 kPa (Phase 3). The syringe was equipped with an end-stop nut to maintain identical pressure conditions across all measurements. Afterward, the valve was opened to pressurize the system, which drove water through the chip. The outflow water was continuously collected into a beaker of known initial mass, placed on a Radwag AS 200/X balance with listed 0.1 mg resolution, to determine the mass of the collected water. Repeatability was excellent because the syringe design leaves no possibility for improper settings. Also the maximum p variation is determined by the total water volume pumped through the system (2.7 mL, Fig. 3C). This expands the system volume from ≈ 50.0 ml to ≈ 55.4 ml and results in a ≈ 5.4 % pressure drop.

The last step to prepare for another cycle was to remove bubbles from the system’s inlet part before reaching the chip, allowing faster repetition of the experiments (Phase 4). A photograph of the system setup is in Fig. 3B, and the results are in Fig. 3C–H.

System settings

We divided the system into three parts to distinguish its hydraulic resistance components (RH), which consist of three components. RH-IN represents hydraulic resistance between the syringe pressurizing the system, two valves (blue and green), tubing with a length of ≈ 100 cm, and the tube-chip connector. RH-CH represents hydraulic resistance inside the chip, RH-OUT the output chip-tube connector, and the relatively short tubing between the connector and the bottle on an analytical scale. The tube between the chip outlet and the analytical balance has a length of ≈ 40 cm.

We started the experiment by pressurizing the system and flowing water through the chip to push all air bubbles out of the system. Once there were no bubbles, we started to capture mass change (Δm) as a function of time (t) on the analytical balance at a two-reading-per-second sampling rate (Fig. 3C–E). Each channel was tested three times under identical conditions to verify the experiment’s reproducibility. We then extracted the Q value by fitting a linear function to the Δm(t) data obtained from the analytical balance. Error bars shown in Figs. 3 and 4 represent the standard deviation of these repeated measurements.

We used linear regression to analyze the relationship between Q, channel geometry, and log(RH) for the plots in Figs. 3F-H and 4. We fitted the data using the general form y = a·x + b, where a represents the slope and b represents the intercept. The fitted lines represent the dependence of Q on L, W, or H, depending on the specific plot in Fig. 3. The linear fits yielded R2 values higher than 0.95 for all experiments, confirming the consistency of the measurements.

Experimental results

We measured the properties of all 16 channels fabricated in a single chip, with each channel measured three times to obtain accurate results and calculate the standard deviation for verifying the method’s accuracy. Subsequently, we plotted the measured values as a Δm(t) function. We fitted the linear part of the Δm(t) curve, where its slope directly corresponds to the Q value, providing insight into the transported volume of liquid through the channel over time. We assumed that pressure loss during the measurement would be negligible for a certain period, which was confirmed by the observed linearity of the curves across most measurements. In channels with higher Q, a more pronounced pressure drop was observed (Fig. 3C) due to faster liquid displacement and compressed air volume expansion. Based on ideal gas behavior, for an initial overpressure of ≈ 100 kPa and a Q of ≈ 10 µL·s⁻1 over 20 s, the estimated pressure decrease is below 10 %, which does not significantly affect the results. In contrast, the longest and narrowest channels exhibited very low throughput, resulting in a negligible pressure drop and a slightly curved flow profile due to transient stabilization (Fig. 3E). Most measured channels exhibited linear Δm(t) behavior throughout the measurement (Fig. 3D), indicating stable pressure and flow conditions within the evaluated timeframe.

As the fluid is displaced and replaced by air in the inlet tubing during the experiment, the RH may change. However, this effect can be considered negligible during measurements due to the low RH of the tubing compared to the overall system, where the RH-CH has a dominant contribution.

Discussion

Our work demonstrated that microfluidic channels with varying dimensions (L, W, and H) exhibited distinct RH-CH leading to Δp changes. This variability shows the importance of optimizing channel dimensions for specific applications, ensuring accurate Q control. Channels with low RH-CH values, typically having short and deep configurations, showed significantly variable Δp. Therefore, we cannot neglect the influence of RH-IN and RH-OUT, and we must consider them during hydrodynamic computing. Conversely, channels with higher RH-CH values, particularly those with the lowest H, displayed improved Q stability but reduced magnitude.

Further experimental data and calculations confirmed that the observed Q trends agree with the theoretical RH predictions. Variations in channels H and W had a more significant impact on Q than on L, which is consistent with the analytical model. However, this outcome also reflects the broader range of values tested for H (factor of 10 ×) and W, compared to a narrower range for L (factor of 4 ×). Therefore, the more negligible influence of L observed in our measurements is not necessarily a general property but a result of the tested parameter space. We proved effective in maintaining laminar flow conditions within the channels, as indicated by the calculated Re value, which was consistently below the threshold for turbulent flow. The highest achieved Re value was 1128, calculated using Eq. (7) for the channels with L, W, and H of 2000 µm, 500 µm, and 82.2 µm, respectively. This Re value is significantly lower than the turbulent flow threshold, but predicting behavior is challenging in the transient flow region. Nevertheless, the results for such channels in the transient region fit the linear function of Q over L (Fig. 3F–H), showing that the flow was still linear since we did not observe any Q decrease.

We analyzed the relationship between the 1/A1 parameter, which is related to the channel geometry, and measured values of Q, showing a linear relationship between their logarithmic values (Fig. 4A). Hence, this dependence should be considered during the design stage of microfluidic systems since it can help to determine desired parameters, such as RH, significant tubing system dimensions, and Δp, essential for the system’s stability over time. Subsequently, we focused on analyzing the relationship between RH-CH and Δp and the possibility of controlling them as described by Eq. (4)–(6). We calculated RH values for all channels, selecting the ones that do not have a marginal RH value compared to RH-IN + RH-OUT, indicating that the pressure drop across the RH-CH is entirely driven by the pressurized air in the syringe, leading to a rapid decrease in Δp. We observed a linear relationship (Fig. 4B) between Δp and log(RH-CH) for channels with low RH-CH values, another crucial factor to consider during pressure-driven microfluidic system design.

Our study demonstrates that understanding the relationship between Δp and Q enables the utilization of cost-effective syringe pumps to control fluid motion in microfluidic applications. We can optimize syringe pump settings for these applications by determining the safe range of Δp for both the chip and fluidic connections, which are typically related to the materials used for the chip, tubing, and gluing. In our setup, the system operated safely without leakage or degradation of any microfluidic system part up to ≈ 300 kPa, which defines a practical long-term operating limit for this configuration. The experimental results validated the effectiveness of the proposed microfluidic setup in controlling and measuring Q and Δp. Detailed analysis of Q, Δp, and Re values provided critical insights into the behavior of the microfluidic system, which is essential for selecting the optimal geometry for applications requiring precise Q and/or Δp control without expensive tools such as pressure-driven pumps. The methodology based on our setup allows for operating syringe pumps within safe Δp ranges, preventing damage to microfluidic chips and connections, thus enhancing the reliability and efficiency of microfluidic research.

Conclusion

This study established a calibration strategy that links microchannel geometry with predictable relationships between pressure drop (Δp) and flow rate (Q), enabling syringe-driven microfluidics to operate within safe and stable conditions for low-budget microfluidic systems. The price of all the setup components, excluding the chip, did not exceed USD 50.

We identified geometry-dependent limits that determine achievable flow regimes by systematically varying channel dimensions and validating experimental results against theoretical predictions. The results confirm that channel width and depth exert a stronger influence on Q stability than length, providing practical guidance for device design. Although the study is limited to straight rectangular channels under laminar flow, the Δp–Q calibration framework is general and can be extended to complex microfluidic systems from PDMS, PMMA, or other materials.

The proposed method goes beyond a simple demonstration of pressure–flow relationships by offering a framework to pre-determine operating ranges that prevent chip leakage or failure, thereby converting a basic syringe setup into a reliable calibration tool. This approach lowers the cost and complexity of microfluidic experiments, while also expanding accessibility to laboratories without commercial pressure controllers. It is particularly suited for resource-limited settings, portable diagnostic platforms, and educational environments where affordability and robustness are critical.

Data availability

Data will be available from the corresponding authors upon a reasonable request.

References

Weber, T. et al. Recovery and isolation of individual microfluidic picoliter droplets by triggered deposition. Sens. Actuat. B Chem. 369, 132289 (2022).

Battat, S., Weitz, D. A. & Whitesides, G. M. An outlook on microfluidics: the promise and the challenge. Lab Chip 22, 530–536 (2022).

Yang, Y., Chen, Y., Tang, H., Zong, N. & Jiang, X. Microfluidics for biomedical analysis. Small Methods 4, 1900451 (2020).

Sanjay, S. T. et al. Recent advances of controlled drug delivery using microfluidic platforms. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 128, 3–28 (2018).

Zou, L. et al. Microfluidic synthesis of magnetic nanoparticles in droplet-based microreactors. Mater. Chem. Phys. 276, 125384 (2022).

Pouyanfar, N. et al. Artificial intelligence-based microfluidic platforms for the sensitive detection of environmental pollutants: Recent advances and prospects. Trends Environ. Anal. Chem. 34, e00160 (2022).

Pol, R., Céspedes, F., Gabriel, D. & Baeza, M. Microfluidic lab-on-a-chip platforms for environmental monitoring. TrAC, Trends Anal. Chem. 95, 62–68 (2017).

Liu, D. et al. Integrated microfluidic devices for in vitro diagnostics at point of care. Aggregate 3, e184 (2022).

Xing, G., Ai, J., Wang, N. & Pu, Q. Recent progress of smartphone-assisted microfluidic sensors for point of care testing. TrAC, Trends Anal. Chem. 157, 116792 (2022).

Li, Z. et al. A review of microfluidic-based mixing methods. Sens. Actuat. A 344, 113757 (2022).

Feng, J., Neuzil, J., Manz, A., Iliescu, C. & Neuzil, P. Microfluidic trends in drug screening and drug delivery. TrAC, Trends Anal. Chem. 158, 116821 (2023).

Zhang, L., Chen, Q., Ma, Y., Sun, J. & Appl, A. C. S. Microfluidic methods for fabrication and engineering of nanoparticle drug delivery systems. Bio Mater. 3, 107–120 (2020).

Castiaux, A. D., Spence, D. M. & Martin, R. S. Review of 3D cell culture with analysis in microfluidic systems. Anal. Methods 11, 4220–4232 (2019).

Zeng, W., Jacobi, I., Beck, D. J., Li, S. & Stone, H. A. Characterization of syringe-pump-driven induced pressure fluctuations in elastic microchannels. Lab Chip 15, 1110–1115 (2015).

Zeng, W. & Fu, H. Precise measurement and control of the pressure‐driven flows for microfluidic systems. Electrophoresis 41, 852–859 (2020).

Smyth, J., Smith, K., Nagrath, S., Oldham, K. Modeling, identification, and flow control for a microfluidic device using a peristaltic pump. In 2020 American Control Conference (ACC) (2020).

Alizadeh, A., Hsu, W.-L., Wang, M. & Daiguji, H. Electroosmotic flow: From microfluidics to nanofluidics. Electrophoresis 42, 834–868 (2021).

Berthier, J. and Silberzan, P. Microfluidics for Biotechnology, Artech House (2010).

Manz, A., Neužil, P., O’Connor, J. S. and Simone, G. Microfluidics and Lab-on-a-Chip, The Royal Society of Chemistry (2020).

Balram, K. C. et al. The nanolithography toolbox. J. Res. Nat. Inst. Stand. Technol. 121, 464–475 (2016).

Zhang, H. et al. Nanolithography toolbox—Simplifying the design complexity of microfluidic chips. J. Vacuum Sci. Technol. B 38, 063002 (2020).

Liu, X. et al. Microfluidics chips fabrication techniques comparison. Sci. Rep. 14, 28793 (2024).

Feng, J., Fohlerová, Z., Liu, X., Chang, H. & Neužil, P. Microfluidic device based on deep reactive ion etching process and its lag effect for single cell capture and extraction. Sens. Actuators, B Chem. 269, 288–292 (2018).

Fohlerova, Z. et al. Rapid characterization of biomolecules’ thermal stability in a segmented flow-through optofluidic microsystem. Sci. Rep. 10, 6925 (2020).

Liu, X. et al. Determination of ionic concentration in microfluidics using electrical methods. Sens. Actuators, A Phys. 392, 116719 (2025).

3M™ Scotch-Weld™ Epoxy Adhesive DP420 Off-White, https://www.3m.com/3M/en_US/p/d/b5005321028).

Funding

This work was supported by the Czech Health Research Council (AZVČR), project No. NW25-02-00459. We also acknowledge the financial support of Grant No. TN02000017 from the Technology Agency of the Czech Republic (National Centre for Biotechnology in Veterinary Medicine), and the ERDF “Multidisciplinary research to increase application potential of nanomaterials in agricultural practice” No. CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/16_025/0007314. The authors acknowledge the CzechNanoLab project LM2023051, funded by MEYS CR, for the financial support of the measurements/sample fabrication at CEITEC Nano Research Infrastructure.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.L. fabricated the Si-glass chips, J.B. prepared the figures, J.V. and J.J. conducted the experiments, L.M. performed the data interpretation, O.Z. supervised the work and I.G. and P.N. wrote majority of the text and came with the basic work idea.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Xiaocheng Liu and Jan Brodský both are considered first authors.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, X., Brodský, J., Vírostko, J. et al. Affordable method for channel geometry–specific flow control in microfluidics without commercial pumps. Sci Rep 15, 40549 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24442-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24442-5