Abstract

Plant-based systems offer a sustainable platform for production of recombinant proteins, but their utility remains limited by host RNA silencing and low yields. Potato virus X (PVX)-derived vectors have shown promise in transient expression systems; however, their efficiency can be further improved by incorporating viral suppressors of RNA silencing (VSRs). Here, we engineered optimized PVX-based expression vectors harboring heterologous VSRs (P19, P38, and NSs) from distinct plant viruses, systematically evaluating the effects of VSR type, insertion position, and transcriptional orientation. Reversing the VSR cassette orientation relative to the target gene alleviated transcriptional interference, significantly improving both target protein and VSR expression. Among the tested VSRs, NSs conferred the highest expression, followed closely by P38. The best-performing pP3-based vectors achieved GFP accumulation of up to 0.50 mg/g fresh weight (FW), representing a 3 ~ 4-fold increase compared to the parental PVX vector (0.13 mg/g FW). For vaccine antigens, maximum yields reached 0.016 mg/g FW for VP1 and 0.017 mg/g FW for S2, exceeding the parental vectors’ yields by over 100-fold. These findings highlight the potential of integrating VSRs into PVX-derived vectors to enhance transient expression of recombinant proteins in Nicotiana benthamiana, providing a robust platform for vaccine antigen production.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With growing concerns over climate change and the urgent need for sustainable manufacturing, plant-based systems have emerged as a promising alternative for the production of pharmaceutical proteins. These platforms offer advantages in terms of scalability, biosafety, and cost-effectiveness compared with traditional systems and thus are an attractive solution for environmentally conscious bioproduction1,2. Once considered a niche technology, plant molecular farming has evolved into a commercially viable platform. Early breakthroughs include expression of human serum albumin and monoclonal antibodies in transgenic tobacco3,4. A major milestone was the Food and Drug Administration’s approval of Elelyso® (taliglucerase alfa), a plant-derived glucocerebrosidase produced in carrot cells for Gaucher disease treatment, which validated the pharmaceutical potential of plant systems5,6.

Since then, plants have successfully been used to produce various viral antigens and virus-like particles. For instance, Nicotiana benthamiana was used to express the Ebola virus glycoprotein via a geminiviral vector, while alfalfa was used to produce the capsid protein VP1 of foot-and-mouth disease virus (FMDV), and both products generated protective immune responses in animal models7,8. During the COVID-19 pandemic, N. benthamiana was used to rapidly produce SARS-CoV-2 spike protein receptor-binding domain and virus-like particles within weeks of the SARS-CoV-2 genome release, and some candidates reached Phase III trials9,10. Despite these successes, plant-based platforms still face key challenges, particularly low recombinant protein yields and protein instability.

To address these limitations, transient expression systems based on plant viral vectors have been developed. First-generation vectors such as Tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) and Potato virus X (PVX) employ full-length viral genomes to establish systemic infection11,12. These systems provided a proof-of-concept for antigen production, e.g., TMV was used to express malaria epitopes in tobacco13, but have drawbacks. For example, large transgene inserts (> 1 kb) often disrupt viral replication or movement, and host RNA silencing mechanisms degrade foreign transcripts.

Second-generation “deconstructed” vectors are a major innovation that retain only essential replication elements and lack non-essential genes such as those encoding movement and coat proteins (CPs). For instance, the TMV-derived magnICON system enables high expression of complex proteins, including full-length antibodies14,15. Similarly, PVX-based vectors with deletions of CP and triple gene block (TGB) have been adapted for transient expression in tobacco protoplasts and intact plants16.

PVX is particularly well-suited for vector engineering due to its compact genome, moderate insert capacity (~ 2 kb), and well-defined molecular biology. Its genome encodes an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), three movement proteins (TGBp1–3), and a CP17. TGBp1 (p25) functions both as a movement protein and a native viral suppressor of RNA silencing (VSR), and thereby promotes degradation of Argonaute 1 (AGO1) and AGO218. However, its silencing suppression activity is weak compared with that of heterologous VSRs.

RNA silencing is a major bottleneck that hampers efficient transgene expression in plants. This antiviral defense mechanism relies on Dicer-like proteins that process double-stranded RNA into 21–24-nt small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), which are then loaded into AGO proteins to guide RNA cleavage19. To overcome this barrier, many plant viruses encode VSRs, which have become indispensable tools in molecular farming. One of the most widely used VSRs, P19 from Tomato bushy stunt virus (TBSV), sequesters siRNAs to prevent their incorporation into AGO complexes20,21. Other VSRs act through distinct mechanisms: P38 from Turnip crinkle virus (TCV) directly binds to AGO1, while NSs from Tomato zonate spot virus (TZSV) targets SGS3 for degradation via both autophagy and the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway22,23. Combinatorial use of VSRs with complementary suppression mechanisms may synergistically enhance protein expression.

In this study, we addressed the yield limitations of conventional PVX vectors by engineering a deconstructed PVX backbone to co-express heterologous VSRs. We selected P19 (TBSV), P38 (TCV), and NSs (TZSV) due to their distinct silencing suppression mechanisms, systematically evaluating the effects of VSR type, genomic position, and transcriptional orientation on expression of GFP and two structurally complex antigens (SARS-CoV-2 S2 subunit and FMDV VP1 capsid protein). We show that placing VSR cassettes in reverse orientation relative to the target gene alleviates transcriptional interference, thereby increasing expression of both the target protein and the VSR. Using this strategy, the NSs-based construct achieved the highest yields, producing up to 0.50 mg/g FW of GFP (≈ 3.8-fold higher than the parental PVX vector, 0.13 mg/g FW) and increasing vaccine antigen accumulation to 0.016 mg/g FW (VP1) and 0.017 mg/g FW (S2), each representing more than a 100-fold improvement over the parental PVX vector.

Results

Co-expression with heterologous VSRs enhances GFP expression from PVX-based vectors

To identify optimal PVX backbones for co-expression with heterologous VSRs, we constructed two previously reported PVX derivatives: pP1, which lacks CP, and pP2, which lacks both TGB and CP (Fig. 1A)24. Consistent with previous studies, GFP expression was higher from pP1 than from wild-type PVX24. By contrast, pP2 exhibited lower GFP expression than pPVX: GFP (Fig. S1). This is likely due to the absence of TGB, which is the native VSR in the PVX genome25.

Co-expression of heterologous VSRs enhances accumulation of GFP expressed from PVX-based vectors in N. benthamiana. (A) Genome organization of the original PVX vector (pPVX: GFP) and its deletion derivatives, namely, pP1:GFP (ΔCP) and pP2:GFP (ΔTGB-ΔCP). Key vector components include the Cauliflower mosaic virus 35 S promoter (35 S), RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), triple gene block (TGB), coat protein (CP), nopaline synthase terminator (NOS), T-DNA left and right borders (LB and RB), and a subgenomic promoter (SGP). (B) Schematic representation of pHREAC-based binary vectors used to co-express heterologous VSRs. The TZSV NSs-coding sequence was replaced by the TBSV P19-coding sequence (pH: P19) or the TCV P38-coding sequence (pH: P38), each under the control of the CaMV 35 S promoter and 35 S terminator (35T). (C) N. benthamiana leaves were agroinfiltrated with pPVX: GFP, pP1:GFP, or pP2:GFP and co-infiltrated with a binary vector expressing P19 (TBSV), P38 (TCV), NSs (TZSV), or an empty vector (EV) at a 1:1 ratio. GFP fluorescence was visualized under UV light at 5 dpi. Representative images from three independent experiments with at least three biological replicates (n ≥ 9) are shown. (D) Western blot analysis of total protein extracts (10 µg per sample) from infiltrated leaves using an anti-GFP antibody. Non-treated (NT) samples, serving as mock controls, were included as negative controls. The Rubisco large subunit stained with Ponceau S (PS) was used as a loading control. GFP signal intensity was quantified using ImageJ. Data represent mean ± SD from one representative experiment out of three repeats (n = 3). Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test; different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05).

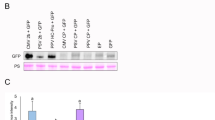

To assess which PVX derivative supports the highest expression in the presence of heterologous VSRs, we performed Agrobacterium-mediated co-infiltration using each PVX-based vector and a vector encoding one of three VSRs: P19 from TBSV (pH: P19), P38 from TCV (pH: P38), and NSs from TZSV (pH: NSs) (Fig. 1B). Under UV illumination, GFP fluorescence was markedly enhanced with all vector backbones upon co-expression of any of the three VSRs (Fig. 1C). These observations were corroborated by Western blot analysis, which confirmed that GFP accumulation closely correlated with fluorescence intensity (Fig. 1D).

Among all combinations tested, the pP2 vector yielded the highest GFP expression upon co-expression of VSRs, with co-expression of NSs yielding the most pronounced enhancement. These results suggest that strategic co-delivery of heterologous VSRs can significantly improve the expression efficiency of PVX-derived vectors in N. benthamiana.

Integration of heterologous VSRs into PVX-derived vectors

To incorporate heterologous VSRs into the PVX-derived vectors, we initially placed the VSR-coding sequences under the control of the native PVX CP subgenomic promoter within the pP1 and pP2 backbones. P38 was chosen for the initial construct because a validated anti-P38 antibody was available, enabling convenient and reliable detection by Western blotting26. However, in the resulting construct (pP1:GFP: P38), in which the PVX CP gene was replaced with P38, expression of both P38 and GFP was undetectable (Fig. S2 A, B). We then generated the pP1:GFP: P19 and pP2:GFP: P19 constructs, in which P19 was expressed under the control of the CaMV 35 S promoter instead of the PVX CP subgenomic promoter. These constructs also resulted in reduced GFP accumulation compared to the pP1 control (Fig. S2C), suggesting that direct insertion of heterologous genes into the PVX genome, particularly at the CP locus, can compromise vector integrity and suppress expression efficiency. Although constructs incorporating P38 and NSs under the 35 S promoter in the same CP-replacement configuration were also generated and tested in parallel, only the P19 data are presented here, as these experiments were completed first. The low expression observed with P19 prompted a shift in our design strategy toward configurations that would minimize disruption to the native PVX genomic architecture.

To circumvent these limitations, we repositioned the VSR expression cassettes downstream of the nopaline synthase terminator (NOS) enabling independent expression under the CaMV 35 S promoter without disrupting the PVX coding architecture (Fig. 2A). We then compared the expression levels of GFP from these constructs with those observed in co-expression experiments. The pP2P38:GFP and pP2NSs: GFP constructs, which express P38 and NSs, respectively, yielded moderately higher GFP expression than pP2:GFP alone (Fig. 2B, C). However, their expression was lower than that observed in independent co-infiltration assays. Notably, pP2P19:GFP did not improve GFP expression and was excluded from further vector development.

Construction and expression analysis of PVX-based vectors integrating heterologous VSRs in the same orientation as GFP. (A) Schematic representation of PVX-derived vectors in which heterologous VSRs (P19, P38, and NSs) were inserted in the same transcriptional orientation as GFP to generate the pP2P19:GFP, pP2P38:GFP, and pP2NSs: GFP constructs. (B) Transient expression in N. benthamiana leaves was performed by Agrobacterium-mediated infiltration. Constructs were co-infiltrated at a 1:1 ratio with an EV as the VSR control. GFP fluorescence was visualized under UV light at 5 and 7 dpi. Representative images from three independent experiments (n ≥ 9) are shown. (C) Total proteins (20 µg per sample) were extracted at 5 dpi and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using an anti-GFP antibody. NT served as mock controls. PS staining of the Rubisco large subunit was used as a loading control for Western blots. Coomassie Brilliant Blue (CBB) staining was used to visualize total proteins, including GFP. Arrowheads denote the GFP-specific band, whereas asterisks denote the P38-specific band. Data represent mean ± SD from one representative experiment of three repeats (n = 3).

Mitigation of transcriptional interference by reversing the orientation of VSR expression cassettes

Transcriptional interference, frequently observed with tandemly arranged transgenes, occurs when closely positioned expression cassettes in the same orientation disrupt each other’s transcription27,28. We hypothesized that the reduced GFP expression observed in our previous constructs was due to transcriptional interference caused by co-directional arrangement of the VSR and GFP cassettes, and that reversing the orientation of the VSR cassette could alleviate this effect.

To test this, we constructed pP3P38:GFP and pP3NSs: GFP, in which the VSR expression cassettes (P38 and NSs, respectively) were inserted in the reverse orientation relative to the GFP cassette (Fig. 3A). We then quantified P38 and NSs transcript levels in N. benthamiana leaves infiltrated with each construct by qRT-PCR. As shown in Fig. S3A, the transcript levels of P38 and NSs were substantially lower in pP2P38:GFP and pP2NSs: GFP, respectively, not only compared to their reverse-oriented counterparts (pP3P38:GFP and pP3NSs: GFP) but also relative to co-infiltration with standalone VSR-expressing vectors (pH: P38 or pH: NSs with pP2:GFP). These results support the hypothesis that transcriptional interference in the pP2 configuration suppresses VSR mRNA accumulation, thereby limiting their suppressor activity and indirectly reducing GFP expression. Although VSR expression in the pP3 constructs was higher than in pP2, the levels were still markedly lower than those from standalone VSR constructs. This suggests that, even when the expression cassette is positioned outside the main PVX genome, PVX-mediated suppression of VSR expression can still occur.

Optimization of expression by reversing the orientation of VSR expression cassettes in PVX-based vectors. (A) Schematic diagram of PVX-derived vectors in which heterologous VSRs (P38 and NSs) were inserted in the reverse orientation relative to the GFP expression cassette to generate pP3P38:GFP and pP3NSs: GFP. These constructs encode the same VSRs as their pP2 counterparts but differ in orientation. (B) Transient expression in N. benthamiana leaves was performed by Agrobacterium-mediated infiltration. Constructs were co-infiltrated with an EV at a 1:1 ratio as a VSR control. GFP fluorescence was visualized under UV light at 5 dpi. Representative images from three independent experiments (n ≥ 9) are shown. (C) Total proteins (20 µg per sample) were extracted from infiltrated leaves at 5 dpi and analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by CBB staining. NT served as mock controls. The arrowhead indicates the GFP-specific band. Band intensities were quantified using ImageJ. Data represent mean ± SD from at least three independent replicates (n = 3). Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test; different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05).

Consistent with the qRT-PCR data, Western blot analysis showed that P38 protein accumulation was markedly reduced in pP2P38:GFP-infiltrated leaves compared with both pP2:GFP + pH: P38 and pP3P38:GFP (Fig. S3B). This concordance between mRNA and protein levels further supports the role of transcriptional interference in limiting VSR expression within the pP2 backbone.

We next compared GFP accumulation from the reverse-oriented constructs (pP3P38:GFP and pP3NSs: GFP) with their same-orientation counterparts (pP2P38:GFP and pP2NSs: GFP) and with co-expression via independent VSR delivery (Fig. 3B, C). In pP3P38:GFP, P38 protein expression was partially restored compared with pP2P38:GFP, but remained much lower than in the standalone VSR expression condition. Despite this, GFP accumulation reached levels comparable to those obtained with independent co-infiltration, indicating that GFP expression does not necessarily scale proportionally with VSR protein abundance. Notably, pP3NSs: GFP outperformed even the co-infiltration condition, suggesting that orientation inversion not only mitigates transcriptional interference but can also enhance overall expression efficiency.

Enhanced expression and reduced cytotoxicity using pP3-based PVX vectors

To maximize GFP expression from the pP3P38:GFP and pP3NSs: GFP constructs, we optimized the Agrobacterium-mediated infiltration conditions and monitored the duration of transgene expression relative to that achieved using the original pPVX: GFP vector. Agroinfiltration was performed at OD600 values of 0.1, 0.2, and 0.4, and both pP3-based vectors yielded substantially higher GFP expression at OD600 values of 0.2 and 0.4 (Fig. S3B).

Importantly, necrosis, which was typically observed in leaves co-infiltrated with pP2:GFP and VSR constructs, was not observed in leaves infiltrated with pP3P38:GFP or pP3NSs: GFP (Fig. 4A; Fig. S3C), suggesting that cytotoxicity was reduced. Moreover, GFP fluorescence from pP3NSs: GFP remained stable for up to 10 days post-infiltration (dpi), indicating that expression was sustained over an extended period (Fig. 4B). Western blot analysis using an anti-GFP antibody confirmed that both pP3P38:GFP and pP3NSs: GFP yielded significantly higher levels of GFP accumulation than pPVX: GFP at all tested time points (Fig. 4C). These results demonstrate that the newly engineered hybrid vectors not only enhance protein expression but also confer improved protein stability and reduced tissue damage in N. benthamiana.

Comparison of GFP expression stability between the original PVX vector and newly developed PVX-based vectors. (A) pPVX: GFP, pP3P38:GFP, and pP3NSs: GFP were transiently expressed in N. benthamiana leaves via Agrobacterium-mediated infiltration. Each construct was co-infiltrated with an EV at a 1:1 ratio as a concentration control. Leaves were imaged under UV and white light at 7 dpi. Representative images from three independent experiments (n ≥ 9) are shown. (B) N. benthamiana leaves were agroinfiltrated with the indicated constructs, and GFP fluorescence was monitored under UV light at 3–10 dpi to evaluate expression stability. Representative images are shown; results were consistent across three independent experiments. (C) GFP accumulation was assessed by SDS-PAGE (20 µg per sample) using CBB staining and by Western blotting (10 µg per sample) using an anti-GFP antibody. NT samples served as mock controls. The arrowhead indicates the GFP-specific band. The Rubisco large subunit stained with CBB or PS served as a loading control. Band intensities were quantified using ImageJ. Data represent mean ± SD from at least three independent experiments (n = 3). Statistical significance was determined using the Student’s t-test. Asterisks denote significant differences compared with pPVX: GFP (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001).

Absolute quantification of GFP expression for standardized comparison

To enable standardized comparison of expression efficiency among PVX-based vectors, we conducted absolute quantification of GFP accumulation using purified recombinant GFP as a calibration standard. Known amounts of GFP (50–400 ng per lane) were loaded on SDS-PAGE gels to generate a calibration curve, allowing band intensities from plant-expressed samples to be converted into mg of GFP per gram of fresh weight (FW).

Using this approach, we quantified GFP levels in N. benthamiana leaves infiltrated with pP2P19:GFP, pP2P38:GFP, and pP2NSs: GFP, which yielded approximately 0.21, 0.29, and 0.42 mg/g FW, respectively (Fig. S5A). To assess the performance of the optimized pP3-based constructs, we extended the analysis to include pP3P38:GFP and pP3NSs: GFP, which accumulated 0.44 and 0.50 mg/g FW, respectively, both comparable to or exceeding that of pP2NSs: GFP (Fig. S5A).These results demonstrate that the pP3-based vectors consistently support higher levels of recombinant protein accumulation compared to earlier constructs, reflecting both improved expression efficiency and enhanced protein stability. Furthermore, by expressing yields in absolute units (mg/g FW), our system enables direct benchmarking against previously reported PVX-based platforms, providing a robust foundation for evaluating vector performance and guiding further optimization.

Production of recombinant vaccine proteins in plants using newly developed hybrid PVX-based vectors

To evaluate the utility of our hybrid PVX-based vectors for vaccine antigen production, we constructed vectors expressing the capsid protein VP1 from the type O strain of FMDV (pP3P38:VP1 and pP3NSs: VP1) and the S2 subunit of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein (pP3P38:S2 and pP3NSs: S2) (Fig. 5A). The VP1 and S2 expression cassettes were adapted from previously published designs29,30, with a BiP leader sequence from Arabidopsis thaliana fused to the N-terminus of each antigen to direct nascent polypeptides to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) for proper folding and stabilization, thereby enhancing overall accumulation levels. Additionally, a detection tag, either a cellulose-binding domain (CBD) for VP1 or a His₆ tag for S2, was fused to the C-terminus, followed by an HDEL sequence serving as an ER retention signal31. Control vectors (pPVX: VP1 and pPVX: S2) lacking heterologous VSRs were also constructed.

Enhanced expression of vaccine antigen proteins using newly developed PVX-based vectors in N. benthamiana. (A) Schematic diagram of PVX-derived vaccine vectors in which the GFP-coding sequence of pP3P38:GFP and pP3NSs: GFP was replaced with the gene encoding VP1 (BiP: VP1:CBD: HDEL) or S2 (BiP: S2:His6:HDEL). (B) Western blot analysis of soluble proteins (20 µg per sample) extracted from agroinfiltrated N. benthamiana leaves expressing VP1 or S2, which were detected using an anti-CBD or anti-His6 antibody, respectively. Band intensities were quantified using ImageJ. Data represent the mean ± SD from at least three independent experiments (n = 3). Statistical significance was determined using the Student’s t-test. Asterisks indicate significant differences compared with pPVX: VP1 or pPVX: S2 (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001). (C) To confirm antigen identity, the same membranes were stripped and reprobed with anti-CBD or anti-His₆ antibodies after initial detection with commercial anti-FMDV (VP1) and anti-S2 (S2) antibodies, respectively. Samples were collected at 3 and 5 dpi, and total soluble proteins (20 µg per sample) were separated by SDS-PAGE prior to immunodetection. The Rubisco large subunit stained with PS served as a loading control. GFP-expressing samples were included as negative controls (NC).

To compare antigen expression efficiencies, we performed Agrobacterium-mediated transient expression and analyzed protein accumulation by Western blotting using anti-CBD and anti-His6 antibodies at 3, 5, and 7 dpi (Fig. 5B). Infiltration with the hybrid pP3 vectors resulted in antigen expression levels more than 100-fold higher than those achieved by co-infiltration of pPVX constructs with VSRs. VP1 and S2 were also readily detected using anti-FMDV32 and anti-S2 antibodies (Fig. 5C), confirming their suitability as recombinant vaccine antigens. Consistent with the GFP expression results, the pP3P38 vector significantly reduced cell death compared with co-expression with P38, indicating enhanced antigen expression with decreased cytotoxicity (Fig. S4).These results confirm that the engineered PVX-based vectors are highly effective for transient expression of complex recombinant antigens in N. benthamiana, supporting their potential application in plant-based vaccine development.

To quantify vaccine protein expression, we performed quantitative analysis of VP1 and S2 proteins using purified recombinant protein standards, analogous to our approach for GFP. Using a CBD-fusion protein and S2-His6 recombinant protein as standards, we generated calibration curves to determine the absolute amounts of VP1 and S2 expressed in plant samples. At 3 dpi, Western blot analysis using anti-CBD and anti-His₆ antibodies showed maximum expression levels of approximately 0.016 mg/g FW for VP1 and 0.017 mg/g FW for S2 (Fig. S5B, C). Although these expression levels are lower than those observed for GFP, they represent meaningful yields for complex, multiepitope vaccine antigens and validate the utility of our PVX-based platform for antigen production. This quantitative analysis establishes a baseline for future optimization and highlights the platform’s potential for plant-based vaccine development.

Discussion

In this study, we engineered a novel PVX-based expression system for enhanced recombinant protein production in plants by co-expressing heterologous VSRs. We examined how VSR identity, genomic insertion site, and transcriptional orientation within the PVX backbone affect expression. When VSR cassettes were arranged in the same (virus‑sense) orientation as the target gene, expression of both the VSR and the target decreased, consistent with transcriptional interference.

To address this, we placed VSR cassettes outside the main target expression unit under independent CaMV 35 S promoters (Fig. 2A). This configuration increased GFP accumulation, with the magnitude of improvement differing among VSRs, reflecting mechanism‑specific effects. Reversing the VSR cassette orientation relative to the target gene markedly alleviated transcriptional interference, restoring or exceeding expression levels obtained by co‑infiltration with standalone VSR plasmids (Fig. 3). This conclusion is supported by qRT‑PCR and Western blot data showing higher VSR transcript and protein levels in reverse‑oriented constructs than in same‑orientation counterparts. Notably, in pP3 constructs, P38 protein recovered only partially relative to standalone VSR expression, yet GFP levels matched those seen with co-infiltration, suggesting that target expression does not scale proportionally with VSR abundance in this architecture.

The pronounced effect of suppressor orientation observed here contrasts with findings from the pEff vector system, where a forward-oriented P24 suppressor did not impair target gene expression33. Unlike pEff, which retains only essential replication elements, our PVX‑based vectors preserve much of the viral coding framework, increasing the risk of promoter occlusion and read‑through when additional cassettes are inserted in the virus‑sense orientation. Removing nonessential PVX genes, as in the pEff system, may therefore be another strategy for improving expression. These observations emphasize the need for orientation‑aware design in multi‑promoter viral vectors. They also motivate future testing of tandem 3′‑processing modules (e.g., 35 S T + Nos T) to reduce read‑through and post‑transcriptional silencing in architecturally dense contexts.

In our study, GFP expression reached up to 0.50 mg/g fresh weight (FW). This value is higher than the yields reported for early PVX–GFP constructs34 (typically 0.1–0.3 mg/g FW with co-delivered suppressors) but lower than the maximum reported for the streamlined pEff vector33 (~ 1 mg/g FW). For the two vaccine antigens, VP1 and S2, maximum yields were 0.016 and 0.017 mg/g FW, respectively, which fall within the range reported for other viral vector platforms in N. benthamiana (0.01–0.2 mg/g FW) and were achieved without co-infiltrated VSR plasmids or systemic infection under our experimental conditions. The modular design of these PVX-based vectors—allowing adjustment of VSR type, orientation, and genomic placement—provides flexibility for tailoring expression to diverse target proteins.

Differences in VSR performance likely reflect variation in their interactions with host silencing pathways and compatibility with PVX-based expression. P19 sequesters siRNAs in the cytoplasm before RISC assembly35,36, which may only partially delay silencing in systems requiring sustained subgenomic RNA transcription. By contrast, P38 from TCV binds AGO1 and blocks active RISC complexes22,36, while NSs targets SGS3, thereby reducing secondary siRNA generation23. The relatively high and stable expression observed with pP3NSs: GFP is consistent with such downstream interference. These observations suggest that VSRs acting at post-RISC or amplification stages, such as P38 and NSs, may be particularly suited for integration into PVX vectors intended for longer-term expression.

Interestingly, while optimized pP3 vectors increased GFP expression by approximately 3–4-fold relative to the parental PVX vector, VP1 and S2 levels increased by over 100-fold under our assay conditions (Fig. S5). The basis for this discrepancy remains to be fully clarified, but may involve differences in subcellular localization and post-translational processing. GFP is a soluble cytosolic protein, whereas VP1 and S2 were engineered for ER targeting. VSRs such as P38 and NSs have been reported to influence ER stress responses and ER-associated degradation pathways in certain plant–virus interactions37,38. It is therefore possible that their presence modulated the ER environment in a way that favored antigen accumulation. Further experiments will be needed to test this hypothesis, including analysis of ER stress markers and secretory pathway dynamics39.

In conclusion, while our results demonstrate a significant improvement over the parental PVX vector, further optimization is possible. Future strategies could include exploring alternative strong promoters and terminators beyond the conventional CaMV 35 S and NOS elements40,41,42, implementing host-specific codon optimization, and incorporating expression-enhancing 5′ untranslated regions (UTRs)43,44,45. The apparent limitation of excessive heterologous VSR expression in our PVX system may also help reduce plant cytotoxicity, which could be an important factor in balancing yield and plant health. A deeper mechanistic understanding of plant–virus interactions and VSR biology will be crucial for the rational design of next-generation expression systems capable of meeting the demands of diverse molecular farming applications.

Materials and methods

Growth conditions for plants and bacteria

Nicotiana benthamiana plants used in this study were originally obtained from Dr. Dinesh Kumar (University of California, Davis) and have been maintained in our laboratory as standard experimental stocks. The species identity was verified based on morphological characteristics by trained laboratory personnel. As these plants were propagated from long-established laboratory stocks and not collected from the wild, no voucher specimen was deposited and no specific collection permission was required. Plants were grown for 4–5 weeks in a controlled growth chamber at 23–25 °C under a 16-hour light/8-hour dark photoperiod prior to agroinfiltration.

Agrobacterium tumefaciens strains were cultured at 28 °C and Escherichia coli was cultured at 37 °C in LB medium supplemented with appropriate antibiotics. Bacterial cultures were incubated for 16–18 h with shaking at 180–220 rpm.

Vector construction

The PVX vector pgR106 (GenBank accession no. AY297843)46 served as the backbone for all constructs. The GFP gene, originally described by Moon et al.38, was PCR-amplified from a 35 S: GFP plasmid using primers F1/R1. The PCR product and pgR106 were digested with AscI and SalI, and ligated using T4 DNA ligase (NEB, MA, USA) to generate pPVX: GFP.

A CP-deleted construct (pP1:GFP; PVXΔCP) was generated by SalI–XhoI digestion of pPVX: GFP followed by self-ligation24. The pP2:GFP construct (PVXΔTGBΔCP) was produced using the In-Fusion Cloning Kit (Takara Bio, Tokyo, Japan). Briefly, a TGB-deleted SGP: GFP fragment (PCR-amplified from pPVX: GFP with F2/R2) was inserted into BstZ17I–XhoI-digested pPVX: GFP. This intermediate was then digested with SalI and XhoI to remove CP, followed by ligation.

For VSR expression, the NSs-coding region (TZSV NSs; GenBank # MK52140) in the pHREAC vector (Addgene #134908; gift from Dr. George Lomonossoff)47 was replaced with P19 (TBSV P19; GenBank # AJ288942); or P38 (TCV P38; GenBank # HQ589261) coding sequences to generate pH: P19 and pH: P38. P19 and P38 were amplified (primers F3/R3 and F4/R4, respectively) from a previously described binary vector38,48, digested with BamHI and EcoRI, and ligated into pHREAC.

To construct pP1:GFP: P38, an SGP: P38 fragment (amplified from pH: P38 with F5/R5) was inserted into SalI–XhoI-digested pPVX: GFP. For pP1:GFP: P19 and pP2:GFP: P19, a 35 S: P19 fragment (amplified from pH: P19 with F6/R6) was inserted into SalI–XhoI-digested pPVX: GFP and pPVXΔTGB: GFP, respectively.

Constructs pP2P19:GFP, pP2P38:GFP, and pP2NSs: GFP were generated by inserting 35 S-driven P19, P38, or NSs with a 35 S terminator into SfoI–SacI-linearized pP2:GFP via In-Fusion cloning. The full expression cassettes (35 S: P19:35T, 35 S: P38:35T, 35 S: NSs:35T) were amplified from pH: P19, pH: P38, and pH: NSs using primers F7/R7.

To generate pP3P38:GFP and pP3NSs: GFP, the pP2:GFP was linearized with SacI, and the corresponding VSR cassettes (F8/R8) were inserted using the In-Fusion Cloning Kit (Takara Bio).

For antigen expression, GFP region in pPVX: GFP, pP3P38:GFP, and pP3NSs: GFP was replaced with the VP1 capsid gene of FMDV (GenBank AEA48888) or the S2 subunit gene of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein (gifts from Dr. Hwang, POSTEC)29,30. The BiP: VP1:CBD: HDEL and BiP: S2:His₆:HDEL cassettes were amplified using F9/R9 and F10/R10, respectively, and inserted into AscI–XhoI-digested recipient vectors using T4 DNA ligase.

Final plasmids were verified by Sanger sequencing and introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 by electroporation. Primer sequences are listed in Table S1. Colony PCR using cloning or vector-specific primers was performed to confirm the presence and integrity of inserts in transformed A. tumefaciens strains.

Transient expression in N. benthamiana leaves

A. tumefaciens cells harboring recombinant vectors were harvested by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 15 min and resuspended in infiltration buffer containing 10 mM MES (pH 5.6), 10 mM MgCl2, and 200 µM acetosyringone. For standard protein expression and quantification experiments, Agrobacterium cultures were adjusted to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.4.

For co-infiltration experiments involving multiple constructs, such as a target gene construct combined with a VSR or an EV, each culture was individually adjusted to OD600 = 0.4, then mixed in equal volumes. The resulting bacterial suspension had a total OD600 of 0.4, with each strain contributing equally (OD600 = 0.2). This approach ensured a constant overall bacterial load while allowing co-expression of constructs. For cell death assays, cultures were prepared at varying OD₆₀₀ values (0.1, 0.2, and 0.4) to examine the relationship between inoculum density, GFP expression, and necrotic symptom development.

All Agrobacterium suspensions were incubated at room temperature for 3 h to induce gene expression, the bacterial suspension was infiltrated into fully expanded leaves of 4–5-week-old N. benthamiana plants using a needleless syringe. Infiltration was performed 3–4 times per plant to ensure consistent delivery.

Western blot analysis

Total proteins were extracted from agroinfiltrated N. benthamiana leaves by freezing and grinding approximately 30 mg of leaf tissue, harvested from a minimum of three individual plants per sample, in 130 µL of NP-40 lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0; 0.5 mM EDTA, pH 8.0; 150 mM NaCl; 0.5% NP-40; and a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Switzerland)) or urea lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0; 90 mM KOH; 100 mM NaH2PO4; 8 M urea; and a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche)). Lysates were incubated on ice for 20 min and centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 20 min, and the supernatants were collected. Protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford assay using bovine serum albumin as the standard.

For quantitative analysis of recombinant proteins expressed in N. benthamiana, recombinant Aequorea victoria GFP protein (Abcam), CBD-fusion protein (BioApp, Inc.44), and SARS-CoV-2 Spike S2 extracellular domain (ECD)-His recombinant protein (Sino Biological, China) were used as standards. These proteins were diluted in same extraction buffer used for plant protein samples at concentrations appropriate for standard curve generation.

Protein samples were denatured by heating at 100 °C for 5 min in 5× SDS loading buffer (60 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8; 14.4 mM 2-mercaptoethanol; 25% glycerol; 2% SDS; and 0.1% bromophenol blue) and resolved by SDS-PAGE. After electrophoresis, proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes or stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue. Membranes were blocked with EveryBlot Blocking Buffer (Bio-Rad, CA, USA) and incubated overnight at 4 °C with the following primary antibodies: anti-GFP (1:1000; Santa Cruz Biotech., CA, USA), anti-His6 (1:500; Roche, Switzerland), anti-PVX CP (1:3000; BIOREBA, Switzerland), anti-S2 (1:2000; Invitrogen, CA, USA), anti-FMDV (1:2000;32), anti-P38 (1:2000;49), and anti-CBD (1:5000; BioApp. Inc., Republic of Korea).

Following three washes with 1X PBST wash buffer (137 mM Sodium chloride, 2.7 mM Potassium chloride, 4.3 mM Sodium phosphate dibasic, 1.46 mM Potassium phosphate monobasic, 0.05% Tween 20, pH 7.4), membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies goat anti-mouse IgG H&L (Abcam, MA, UK) and goat anti-rabbit IgG H + L (Invitrogen)) diluted 1:10,000. Protein bands were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence detection solution (Cytiva, MA, USA).

RNA extraction and q-RT-PCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted from ~ 30 mg of agroinfiltrated N. benthamiana leaves, harvested at 2 dpi from at least three individual plants per sample, using the NucleoSpin RNA Plant Kit (Macherey-Nagel, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 1 µg of total RNA using oligo(dT) primers and M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen). Q-RT-PCR was performed with gene-specific primers listed in Table S1. Transcript abundance was normalized to the internal reference gene NbActin using the 2^–ΔΔCT method.

Visualization of green fluorescence

GFP fluorescence in infiltrated N. benthamiana leaves was visualized under ultraviolet (UV) light using the UVP MultiDoc-It Imaging System (254/368 nm; Analytik Jena, Germany).

Statistical analysis

All experiments were conducted with at least three independent biological replicates unless otherwise stated. Biological replicates refer to mixed samples collected from several leaves of three different N. benthamiana plants (n = 3). Each experiment was independently repeated three times, resulting in a total of at least nine samples (3 plants × 3 independent experiments). Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical comparisons between two groups were conducted using two‑tailed Student’s t‑tests. For comparisons involving more than two groups, one‑way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was applied. P‑values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Significance levels are indicated in figures as follows: *p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001. When different letters are used to denote significance, they indicate statistically significant differences at p < 0.05. Statistical analyses and calculations of mean and SD were performed using Microsoft Excel and Python 3. Assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variance were visually inspected and met for parametric tests.

Data availability

All datasets generated for this study are included in the paper/supplementary information.

Data availability

All datasets generated for this study are included in the paper/supplementary information.

References

Shanmugaraj, B., Bulaon, I., Phoolcharoen, W. & C. J. & Plant molecular farming: A viable platform for Recombinant biopharmaceutical production. Plants 9, 842 (2020).

Liu, H. & Timko, M. P. Improving protein quantity and quality—the next level of plant molecular farming. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 1326 (2022).

Sijmons, P. C. et al. Production of correctly processed human serum albumin in Transgenic plants. Bio/technology 8, 217–221 (1990).

Hiatt, A., Caffferkey, R. & Bowdish, K. Production of antibodies in Transgenic plants. Nature 342, 76–78 (1989).

Fox, J. L. First plant-made biologic approved. Nat. Biotechnol. 30, 472–473 (2012).

Tekoah, Y. et al. Large-scale production of pharmaceutical proteins in plant cell culture—the protalix experience. Plant Biotechnol. J. 13, 1199–1208 (2015).

Li, Y. et al. High expression of foot-and-mouth disease virus structural protein VP1 in tobacco chloroplasts. Plant Cell Rep. 25, 329–333 (2006).

Phoolcharoen, W. et al. Expression of an Immunogenic Ebola immune complex in Nicotiana benthamiana. Plant Biotechnol. J. 9, 807–816 (2011).

Ward, B. J. et al. Phase 1 randomized trial of a plant-derived virus-like particle vaccine for COVID-19. Nat. Med. 27, 1071–1078 (2021).

Shin, Y. J. et al. N-glycosylation of the SARS-CoV-2 receptor binding domain is important for functional expression in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 12, 689104 (2021).

Donson, J., Kearney, C., Hilf, M. & Dawson, W. Systemic expression of a bacterial gene by a tobacco mosaic virus-based vector. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 88, 7204–7208 (1991).

Chapman, S., Kavanagh, T. & Baulcombe, D. Potato virus X as a vector for gene expression in plants. Plant J. 2, 549–557 (1992).

Turpen, T. H. et al. Malaria epitopes expressed on the surface of Recombinant tobacco mosaic virus. Bio/technology 13, 53–57 (1995).

Gleba, Y., Marillonnet, S. & Klimyuk, V. Engineering viral expression vectors for plants: The ‘full virus’ and the ‘deconstructed virus’ strategies. Curr. Opin. Plant. Biol. 7, 182–188 (2004).

Santi, L. et al. Protection conferred by Recombinant yersinia pestis antigens produced by a rapid and highly scalable plant expression system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 103, 861–866 (2006).

Peyret, H. & Lomonossoff, G. P. When plant virology Met agrobacterium: The rise of the deconstructed clones. Plant Biotechnol. J. 13, 1121–1135 (2015).

Huisman, M. J., Linthorst, H. J., Bol, J. F. & Cornelissen, B. J. The complete nucleotide sequence of potato virus X and its homologies at the amino acid level with various plus-stranded RNA viruses. J. Gen. Virol. 69, 1789–1798 (1988).

Aguilar, E. et al. The P25 protein of potato virus X (PVX) is the main pathogenicity determinant responsible for systemic necrosis in PVX-associated synergisms. J. Virol. 89, 2090–2103 (2015).

Ding, S. W. & Voinnet, O. Antiviral immunity directed by small RNAs. Cell 130, 413–426 (2007).

Vargason, J. M., Szittya, G., Burgyán, J. & Hall, T. M. T. Size selective recognition of SiRNA by an RNA Silencing suppressor. Cell 115, 799–811 (2003).

Scholthof, H. B. The Tombusvirus-encoded P19: From irrelevance to elegance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 4, 405–411. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro1395 (2006).

Azevedo, J. et al. Argonaute quenching and global changes in Dicer homeostasis caused by a pathogen-encoded GW repeat protein. Genes Dev. 24, 904–915 (2010).

Chen, J. et al. The nonstructural protein NSs encoded by tomato Zonate spot virus suppresses RNA Silencing by interacting with NbSGS3. Mol. Plant Pathol. 23, 707–719 (2022).

Larsen, J. S. & Curtis, W. R. RNA viral vectors for improved Agrobacterium-mediated transient expression of heterologous proteins in Nicotiana benthamiana cell suspensions and hairy roots. BMC Biotechnol. 12, 1–11 (2012).

Chiu, M. H., Chen, I. H., Baulcombe, D. C. & Tsai, C. H. The Silencing suppressor P25 of potato virus X interacts with Argonaute1 and mediates its degradation through the proteasome pathway. Mol. Plant Pathol. 11, 641–649. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1364-3703.2010.00634.x (2010).

Moon, J. Y., Lee, J. H., Oh, C. S., Kang, H. G. & Park, J. M. Endoplasmic reticulum stress responses function in the HRT-mediated hypersensitive response in Nicotiana benthamiana. Mol. Plant. Pathol. 17, 1382–1397. https://doi.org/10.1111/mpp.12369 (2016).

Padidam, M. & Cao, Y. Elimination of transcriptional interference between tandem genes in plant cells. Biotechniques 31, 328–334 (2001).

Shearwin, K. E., Callen, B. P. & Egan, J. B. Transcriptional interference–a crash course. Trends Genet. 21, 339–345 (2005).

Song, S. J. et al. SARS-CoV‐2 Spike trimer vaccine expressed in Nicotiana benthamiana adjuvanted with alum elicits protective immune responses in mice. Plant Biotechnol. J. 20, 2298–2312 (2022).

Lee, G. et al. Oral immunization of Haemaggulutinin H5 expressed in plant Endoplasmic reticulum with adjuvant saponin protects mice against highly pathogenic avian influenza A virus infection. Plant Biotechnol. J. 13, 62–72 (2015).

Vitale, A. & Ceriotti, A. Protein quality control mechanisms and protein storage in the Endoplasmic reticulum. A conflict of interests? Plant Physiol. 136, 3420–3426 (2004).

Song, B. M., Lee, G. H., Kang, S. M. & Tark, D. Evaluation of vaccine efficacy with 2B/T epitope conjugated Porcine IgG-Fc recombinants against foot-and-mouth disease virus. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 86, 999–1007 (2024).

Mardanova, E. S. et al. Efficient transient expression of Recombinant proteins in plants by the novel pEff vector based on the genome of potato virus X. Front. Plant. Sci. 8, 247. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2017.00247 (2017).

Baulcombe, D. C., Chapman, S. & Santa Cruz, S. Jellyfish green fluorescent protein as a reporter for virus infections. Plant J. 7, 1045–1053. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-313X.1995.07061045.x (1995).

Lakatos, L. et al. Small RNA binding is a common strategy to suppress RNA Silencing by several viral suppressors. EMBO J. 25, 2768–2780 (2006).

Danielson, D. C. & Pezacki, J. P. Studying the RNA Silencing pathway with the p19 protein. FEBS Lett. 587, 1198–1205 (2013).

Adhikari, B., Verchot, J., Brandizzi, F. & Ko, D. K. ER stress and viral defense: Advances and future perspectives on plant unfolded protein response in pathogenesis. J. Biol. Chem., 108354 (2025).

Moon, J. Y., Lee, J. H., Oh, C. S., Kang, H. G. & Park, J. M. Endoplasmic reticulum stress responses function in the HRT-mediated hypersensitive response in Nicotiana benthamiana. 17 1382-1397 https://doi.org/10.1111/mpp.12369 (2016).

Mardanova, E. S. et al. Efficient transient expression of Recombinant proteins in plants by the novel pEff vector based on the genome of potato virus X. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 247 (2017).

Outchkourov, N., Peters, J., De Jong, J., Rademakers, W. & Jongsma, M. The promoter–terminator of chrysanthemum rbcS1 directs very high expression levels in plants. Planta 216, 1003–1012 (2003).

Nagaya, S., Kawamura, K., Shinmyo, A. & Kato, K. The HSP terminator of Arabidopsis Thaliana increases gene expression in plant cells. Plant Cell Physiol. 51, 328–332 (2010).

Yun, A., Kang, J., Lee, J., Song, S. J. & Hwang, I. Design of an artificial transcriptional system for production of high levels of Recombinant proteins in tobacco (Nicotiana benthamiana). Front. Plant Sci. 14, 1138089 (2023).

Kim, Y. et al. The immediate upstream region of the 5′-UTR from the AUG start codon has a pronounced effect on the translational efficiency in Arabidopsis Thaliana. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 485–498 (2014).

Park, Y. et al. Development of Recombinant protein-based vaccine against classical swine fever virus in pigs using Transgenic Nicotiana benthamiana. Front. Plant Sci. 10, 624 (2019).

Song, S. J. et al. Plant-based, adjuvant‐free, potent multivalent vaccines for avian influenza virus via Lactococcus surface display. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 63, 1505–1520 (2021).

Lu, R. et al. High throughput virus-induced gene Silencing implicates heat shock protein 90 in plant disease resistance. EMBO J. (2003).

Peyret, H., Brown, J. K. & Lomonossoff, G. P. Improving plant transient expression through the rational design of synthetic 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions. Plant. Methods. 15, 1–13 (2019).

Tian, M., Benedetti, B. & Kamoun, S. A second Kazal-like protease inhibitor from phytophthora infestans inhibits and interacts with the apoplastic pathogenesis-related protease P69B of tomato. Plant Physiol. 138, 1785–1793 (2005).

Kang, H. G., Kuhl, J. C., Kachroo, P. & Klessig, D. F. CRT1, an Arabidopsis ATPase that interacts with diverse resistance proteins and modulates disease resistance to turnip crinkle virus. Cell. Host Microbe. 3, 48–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2007.11.006 (2008).

Acknowledgements

We thank Sir David Baulcombe for providing the pGR106 vector, Dr. George Lomonossoff for providing pHREAC plasmid, Dr. Tark Dongseob for providing anti-FMDV antibody, Dr. Dinesh Kumar (University of California, Davis) for kindly providing N, benthamiana seeds that have been maintained as laboratory stocks, and Dr. Inhwan Hwang for providing the FMDV VP1 and the SARS-CoV-2 S2 clones.

Funding

This work was supported by the KRIBB Initiative Program (KGM9942522 and KGM1082511) and the Basic Research Program of the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2020R1I1A2075335 to J.M.P.) funded by the Korean government (Ministry of Science and ICT).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.M.P. conceived and supervised the study. S.K.J. and H.J.C. performed the experiments. S.K.J., H.J.C., S.H.J., and J.M.P. analyzed the data. S.K.J., H.J.C., and J.M.P. wrote the manuscript, and K.H.P. and J.M.P. revised it. All authors contributed to the work and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jung, S., Choi, H.J., Jo, S.H. et al. Engineering PVX vectors harboring heterologous VSRs to enhance Recombinant vaccine protein expression in plants. Sci Rep 15, 40330 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24470-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24470-1