Abstract

This study aims to investigate the mediating role of anxiety in the relationship between experiential avoidance and BrainRot among teenagers, as well as the moderating effect of physical exercise on the relationship between experiential avoidance and anxiety. A cross-sectional study was conducted between February and March 2024 using convenience sampling from seven schools across five provinces in China. A total of 4058 participants (2020 boys and 2038 girls) were included, with a mean age of 13.06 ± 3.97 years. Data on experiential avoidance, BrainRot, anxiety, and physical exercise were collected using self-reported questionnaires. Correlation analyses were performed, and a moderated mediation model was constructed to examine the relationships among these variables. After controlling for participants’ grade level, age, and gender, the study found that experiential avoidance significantly predicted BrainRot among teenagers (β = 0.542, p < 0.001). This predictive effect remained significant even after incorporating anxiety as a mediating variable (β = 0.312, p < 0.001). Additionally, physical exercise moderated the relationship between experiential avoidance and anxiety (β = − 0.048, p < 0.001), indicating that physical exercise attenuated the impact of experiential avoidance on anxiety. Experiential avoidance predicts BrainRot in teenagers through anxiety, and physical exercise can mitigate this predictive relationship. It is recommended that guardians of teenagers pay closer attention to those experiencing anxiety to reduce the negative impact of adverse mental health issues and prevent the occurrence of BrainRot.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Experiential avoidance (EA) refers to the tendency of individuals to engage in avoidant behaviors related to emotional or psychological experiences. Specifically, it involves avoiding, suppressing, or escaping from unpleasant emotions, thoughts, feelings, or memories in an effort to alleviate distress. While such avoidance may provide temporary relief in the short term, it can exacerbate suffering and impede psychological adaptation and growth in the long run1. The university years are a developmental period during which emotional regulation skills are still maturing. During this stage, individuals may not have fully mastered effective emotion-regulation strategies and may lack adaptive coping mechanisms when confronted with negative emotions. As a result, they are more likely to resort to avoidance as a means of dealing with unpleasant emotional experiences2. A study on teenagers mental health revealed that approximately 40% to 50% of teenagers reported using avoidant strategies when facing negative emotions. This tendency is particularly pronounced in situations involving academic stress, social adaptation difficulties, or interpersonal conflicts, where students often choose to avoid the issue rather than confront it directly3. When teenagers employ experiential avoidance strategies, they may experience a range of adverse consequences, including increased symptoms of depression and anxiety4, reduced sleep quality5, social withdrawal and loneliness6, and diminished capacity to cope with stress7. Therefore, preventing experiential avoidance is crucial for enhancing teenagers’ physical and mental health, academic performance, and quality of interpersonal relationships. By fostering positive emotion-regulation strategies and self-regulation skills, teenagers can not only improve their academic and life adaptation abilities but also enhance their psychological resilience. This, in turn, promotes healthy social interactions and overall well-being.

The term “BrainRot” has emerged to describe the progressive deterioration of cognitive and intellectual functions resulting from the excessive consumption of low-quality internet content8,9. The Oxford University Press defines it as the decline in one’s mental or intellectual state, particularly due to the overconsumption of trivial or unchallenging online content10. BrainRot encompasses various forms of mental addictive behaviors, typically referring to the decline in cognitive and mental functions caused by excessive immersion in a particular activity or stimulus. The rapid updates, instant gratification, and intense visual stimulation of short video content make viewers prone to a continuous and inescapable state, leading to a strong dependence on such content. Thus, BrainRot can be regarded as a quintessential manifestation of short video addiction11. Recent studies have further demonstrated that prolonged exposure to rapidly updated, visually stimulating short videos significantly impairs brain functions related to attention, memory, cognitive fatigue, and executive control12. For instance, neuroscientific evidence indicates that long-term immersion in such low-quality content diminishes the brain’s ability to process complex tasks, leading to persistent attentional deficits, reduced information-processing efficiency, and the emergence of negative emotions such as anxiety13. Short video platforms, such as TikTok and Douyin, leverage algorithmic recommendations, fragmented content, and instant gratification mechanisms to keep users engaged for extended periods.

This prolonged immersion may result in decreased cognitive abilities, scattered attention, and weakened information processing capabilities. The term “BrainRot” vividly reflects the potential negative impacts of short video addiction. Short videos, typically ranging from a few seconds to several minutes, are characterized by their simplicity and directness. They attract audiences through rapid scene transitions, strong visual impacts, and humorous or sensory stimulation14. For instance, TikTok, a globally popular short video platform, now boasts over 1.677 billion registered users, with 1.1 billion active users across more than 160 countries and regions15. This substantial user base not only highlights its global influence but also underscores the profound impact of short video platforms on contemporary lifestyles and social interactions in the digital age.According to the latest Chinese report on short video development (2024), as of 2024, the number of short video users in China reached 1.05 billion, accounting for 95.5% of the total internet users, with the proportion of teenagers continuing to rise16. Based on cognitive-behavioral theory, an individual’s emotions and behaviors are influenced by their cognitions, which involve interpretations and evaluations of the environment. Experiential avoidance is a coping strategy where individuals evade painful emotions, thoughts, or situations to reduce discomfort17. However, this avoidance behavior is often temporary and may lead to more entrenched problems in the long term. Teenagers, facing academic and life stressors, may choose to avoid negative emotions, manifesting as avoidance of tasks, social interactions, or responsibilities, and instead becoming immersed in short videos18. While short videos provide immediate emotional relief, they do not address the underlying issues and may lead to the accumulation of negative emotions. This, in turn, reinforces the cycle of experiential avoidance and BrainRot19. Previous research has found a positive correlation between experiential avoidance and BrainRot. For example, a cross-sectional study involving 1591 Chinese teenagers revealed that experiential avoidance significantly predicts BrainRot. When facing negative emotions, stress, or social difficulties, teenagers tend to engage in avoidance behaviors and use internet activities to escape real-life distress61,62,63,64,65. Although this behavior offers short-term emotional comfort, it may eventually lead to excessive dependence on the internet20. Therefore, this study hypothesizes that experiential avoidance is positively correlated with BrainRot (H1).

In psychological research, anxiety is typically characterized as an emotional response marked by worry about the uncertainty of future events and potential threats21. The emergence and persistence of anxiety not only have a profound impact on an individual’s emotional health but also affect their behavioral decision-making, emotional regulation, and lifestyle choices22. A meta-analysis conducted in 2021, which included 29 studies, revealed a global prevalence rate of anxiety symptoms among teenagers at 20.5%23. Another meta-analysis conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2022, involving 25 studies with a total of 1,003,743 Chinese teenagers, found an overall prevalence rate of anxiety symptoms at 25.0%24. According to the emotional disorder model, individuals often associate anxiety and other negative emotions with painful experiences, leading them to avoid these emotions. However, this avoidance prevents the expression and release of emotions, further exacerbating emotional suppression and dysregulation, thereby intensifying anxiety symptoms25. Therefore, experiential avoidance is closely related to anxiety among teenagers. Previous research has shown that experiential avoidance positively predicts anxiety. For example, a cross-sectional study involving 124 teenagers found a significant and strong association between experiential avoidance and anxiety26. Additionally, emotion regulation theory emphasizes how individuals cope with and manage their emotions. When faced with anxiety, stress, or negative emotions, individuals typically employ various regulatory strategies, with the goal of alleviating or avoiding unpleasant emotional experiences7,66,67,68,69,70,84. In the context of anxiety, BrainRot can be regarded as a form of emotional avoidance strategy. Individuals experiencing anxiety may turn to short video consumption to temporarily escape feelings of unease or tension, as short videos can quickly capture attention and provide instant gratification. While this behavior may temporarily alleviate anxiety, it does not address the root causes and may further exacerbate emotional distress27. Therefore, anxiety is hypothesized to influence BrainRot. Previous studies have found a positive correlation between anxiety and BrainRot. For example, a cross-sectional study involving 269 teenagers revealed that individuals with higher levels of anxiety were more likely to rely on short video consumption to relieve inner unease and tension, thereby gradually increasing their dependence on short videos28. Anxiety may drive individuals to use short videos as a means of escaping real-life discomfort and stress. This avoidant use often leads to increased dependence on short videos, potentially resulting in addictive behaviors. In summary, the present study hypothesizes that anxiety mediates the relationship between experiential avoidance and BrainRot (H2).

With the increasing awareness of health, more people are paying attention to physical exercise and recognizing its positive role in disease prevention and quality of life improvement. Physical exercise refers to various organized physical exercise; aimed at enhancing strength, endurance, flexibility, and coordination, thereby promoting physical and mental health29. It typically includes aerobic exercise, strength training, flexibility exercises, and balance training, all of which are designed to improve physical fitness and help prevent or alleviate health issues. Self-efficacy, defined as an individual’s confidence in their ability to complete specific tasks, plays a crucial role in this context30. Physical exercise enhances teenagers’ self-efficacy, empowering them to face anxiety with greater confidence. When confronted with challenges and stress, teenagers may be inclined to avoid situations that induce anxiety. However, through physical exercise, they can experience a sense of control over their physical and psychological states, thereby improving their ability to cope with anxiety31. When teenagers achieve success and a sense of control through physical exercise, their self-efficacy is enhanced, leading to reduced anxiety and avoidance behaviors. Previous research has shown that physical exercise regulates anxiety levels and reduces experiential avoidance through physiological, psychological, and behavioral mechanisms. By modulating neurotransmitters, enhancing self-efficacy, improving emotional regulation, and promoting behavioral change, physical exercise helps individuals reduce their tendency to avoid emotions and enhances their ability to cope with anxiety32. These findings provide a theoretical basis for using physical exercise as an effective coping strategy in mental health interventions. In summary, this study hypothesizes that physical exercise moderates the relationship between experiential avoidance and anxiety (H3).

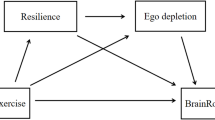

Combining the above evidence, there is a positive correlation between experiential avoidance and BrainRot, and this predictive effect can be transmitted through anxiety. Additionally, physical exercise is hypothesized to moderate the relationship between experiential avoidance and anxiety. Based on these findings, this study will construct a moderated mediation model as shown in Fig. 1.

Materials and methods

Participants

Participants were recruited using a convenience sampling method from seven primary, middle, and high schools in Hunan, Sichuan, Shaanxi, Shanxi, and Anhui provinces in October 2024. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the author’s institution prior to participant recruitment. Data were collected via an online electronic questionnaire distributed through class group chats. The first page of the questionnaire included an informed consent form, which participants were required to read and click “agree” before proceeding with the survey. Only data from participants who completed the entire questionnaire were included in the analysis. Participants who chose not to participate or withdrew during the survey were fully respected, and their decision had no impact on them. The first page of the questionnaire also outlined the survey content, data anonymity, confidentiality, and the intended use of the data. Participants typically completed the electronic questionnaire in less than 5 min. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) aged 10–18 years and enrolled in grades 5 through 12; (2) no diagnosed neurodevelopmental disorders or major psychiatric conditions, as confirmed by school health records. Exclusion criteria included: (1) questionnaire completion time under 5 min or failure to pass built-in logic consistency checks; (2) self-reported or teacher-identified difficulties in reading or comprehension that would prevent independent completion of the online survey. After applying these criteria, the final analytical sample consisted of 4058 participants, including 2020 boys (49.80%) and 2038 girls (50.20%), with a mean age of 13.06 ± 3.97 years.

Measurement tools

BrainRot

The BrainRot Scale was developed by Mao et al.33, and has been validated for use in teenager research34. This scale comprises three dimensions, namely cognitive-behavioral changes, physiological damage, and social attachment, with a total of 13 items. It employs a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Higher scores indicate a more severe degree of problematic BrainRot. In the present study, the Cronbach’s α coefficient for this scale was 0.870, indicating good internal consistency.

Experiential avoidance

This study empoyed the executive Function Scale developed by Huang Chunhui et al.35 and the experiential Avoidance Questionnaire created by Fledderus et al.36, and adapted by Cao Jing et al.37, to measure individuals’ tendency to avoid internal experiences. The questionnaire consists of seven items and utilizes a 7-point Likert scale (1 = “Never”, 7 = “Always”). A higher score on this scale indicates a greater degree of experiential avoidance, reflecting lower psychological flexibility. Cronbach’s α coefficient for anxiety in this study was 0.916, indicating good internal consistency reliability.

Anxiety

In this study, the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-2 (GAD-2) scale was used to assess anxiety levels among teenagers38. The scale consists of two items and employs a 4-point Likert rating system ranging from 1 (not at all) to 4 (nearly every day). The total score ranges from 2 to 8, with higher scores indicating more severe levels of anxiety. The Cronbach’s α coefficient for anxiety in this study was 0.809, indicating good internal consistency reliability.

Physical exercise

In this study, physical exercise was assessed using the revised physical exercise Rating Scale by Liang Deqing39. The scale comprises three subscales: exercise intensity, exercise frequency, and exercise duration. Each subscale includes one item, and the scoring is based on a 5-point Likert scale. The calculation formula for physical exercise volume is as follows: physical exercise Volume = Exercise Intensity × (Exercise Duration − 1) × Exercise Frequency. The total score ranges from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating greater physical exercise volume. The Cronbach’s α coefficient for this survey was 0.623.

Covariates

Gender, grade, and age were included as covariates in this study.

Statistical analysis

Initially, descriptive and correlational analyses of the variables were performed using SPSS version 29.0. Prior to any inferential procedures, the assumption of univariate normality for each continuous variable was examined with the Shapiro–Wilk test, supplemented by descriptive indices of central tendency (M), dispersion (SD), skewness, and kurtosis. In accordance with Kim’s (2013) guidelines40, absolute skewness < 2.0 and absolute kurtosis < 7.0 were taken as evidence that the data were sufficiently close to a normal distribution for parametric testing (Table 1). Subsequently, the SPSS macro PROCESS (models 4 and 7) was employed to construct the models with 5000 bootstrap resamples. In model 4, BrainRot was designated as the independent variable, depression as the dependent variable, and anxiety as the mediating variable. Model 7 was further applied based on model 4, with physical exercise serving as the moderating variable to examine the moderating effects on the relationship between BrainRot and anxiety. Finally, the bias-corrected bootstrap method (with 5,000 random resamples) was used to estimate the 95% confidence interval (95% CI) of the mediating effect, thereby testing the conditional indirect effect of depression and the moderating effect of physical exercise. The significance level was set at α = 0.05.

Results

Common method bias assessment

To evaluate the potential impact of common method bias, Harman’s single-factor test was employed in this study. The analysis revealed that, without principal component factor rotation, five factors had eigenvalues greater than 1. The variance explained by the first factor was 30.41%, which is below the threshold of 40%. Therefore, significant common method bias was not detected in this study.

Correlational analysis

As shown in Table 2, experiential avoidance was significantly and positively correlated with BrainRot and anxiety (r = 0.399, p < 0.01; r = 0.546, p < 0.01, respectively). Additionally, experiential avoidance exhibited a significant negative correlation with physical exercise (r = − 0.135, p < 0.01). BrainRot was positively correlated with anxiety (r = 0.314, p < 0.01) and negatively correlated with physical exercise (r = − 0.126, p < 0.01). A negative correlation was also observed between anxiety and physical exercise (r = − 0.133, p < 0.01).

Mediation model testing

Table 3 and Fig. 2 show that experiential avoidance is significantly positively correlated with teenagers BrainRot (β = 0.384, SE = 0.015, p < 0.001). This positive correlation remains significant even after including the mediating variables (β = 0.312, SE = 0.017, p < 0.01). Additionally, experiential avoidance is significantly positively correlated with teenagers anxiety (β = 0.542, SE = 0.013, p < 0.001), and anxiety is also significantly positively correlated with teenagers BrainRot (β = 0.134, SE = 0.017, p < 0.001). The proportions of the mediating effects are shown in Table 4.

Moderation analysis

After controlling for demographic variables, the results presented in Table 5, Figs. 3, and 4 show that, even after the inclusion of physical exercise, experiential avoidance remains significantly positively correlated with anxiety (β = 0.532, p < 0.001). Furthermore, physical exercise is significantly negatively correlated with anxiety (β = − 0.065, p < 0.001). Additionally, the interaction between experiential avoidance and physical exercise shows a significant negative correlation with anxiety (β = − 0.048, p < 0.001), as detailed in Table 6.

Discussion

The present study is a cross-sectional investigation exploring the relationships among BrainRot, anxiety, physical exercise, and experiential avoidance in teenagers. Additionally, it examines the mediating role of anxiety in the relationship between experiential avoidance and BrainRot, as well as the moderating effect of physical exercise on the relationship between experiential avoidance and anxiety. The findings reveal significant positive correlations among experiential avoidance, BrainRot, and anxiety, as well as a negative correlation between anxiety and physical exercise. Physical exercise is also negatively correlated with experiential avoidance, anxiety, and BrainRot. Mediation analysis indicates that experiential avoidance not only directly influences BrainRot in teenagers but also indirectly affects it through anxiety. Subsequent moderation analysis demonstrates that physical exercise attenuates the relationship between experiential avoidance and anxiety. These results collectively support the hypotheses proposed in this study. The findings highlight the importance of addressing experiential avoidance as a potential risk factor for both BrainRot and anxiety in teenagers. The mediating role of anxiety underscores the need to consider psychological distress as a pathway linking experiential avoidance to BrainRot. Furthermore, the moderating effect of physical exercise suggests that engaging in regular physical exercise may serve as a protective factor against the adverse impact of experiential avoidance on mental health. Future research should explore longitudinal designs to establish causality and investigate additional factors that may influence these relationships.

The present findings demonstrate a significant, positive association between experiential avoidance and BrainRot (β = 0.311, p < 0.001), thereby corroborating Hypothesis 1 and aligning with prior reports (β = 0.657)20,41. Notably, the standardized effect detected here is approximately twice that documented by Cheng et al. (β = 0.149) in a Chinese undergraduate sample42. Three methodological and developmental factors may account for this divergence. First, developmental stage moderates the impact of avoidance-oriented coping. Whereas Cheng et al. recruited university students (Mage ≈ 20 years), the current cohort comprised early and mid-teenagers s (grades 5–12; Mage = 13.06 ± 3.97 years) whose prefrontal regulatory circuits and coping repertoires are still maturing. Consequently, they display greater reliance on external, immediately gratifying stimuli to down-regulate negative affect, amplifying the pathway from experiential avoidance to addictive short-form video use. Second, the phenotype of addiction differed across studies. Cheng et al. employed a global Internet-addiction scale that aggregates diverse online activities (gaming, social networking, browsing), whereas we targeted short-form video engagement specifically. Platforms such as Douyin/TikTok are engineered for rapid, intermittent reinforcement (likes, auto-play, full-screen immersion) that maximizes temporal proximity between avoidance behaviour and reward, thereby potentiating the functional relation assessed here. Third, although both studies used validated psychometric instruments, cultural and linguistic nuances between mainland and Hong Kong youth may introduce measurement non-invariance. teenagers s in mainland China appear to endorse avoidance items more readily and report higher behavioural engagement with short-form videos, inflating observed regression weights. Mechanistically, the results indicate that when confronted with academic or interpersonal stress, teenagers s gravitate toward endless video streams to obtain transient mood repair. The platforms’ immediate feedback loops (view counters, personalised recommendations) furnish rapid positive reinforcement that competes successfully with slower, effortful cognitive reappraisal strategies. Over time, avoidance-motivated scrolling is strengthened through negative reinforcement (momentary relief from distress), establishing a self-perpetuating cycle of escalating use and shortened attentional tolerance for offline tasks43. Taken together, experiential avoidance emerges as a robust cognitive–emotional risk factor for short-form video addiction in youth, meriting targeted intervention (e.g., acceptance-based coping modules) in future prevention programmes. Thus, these findings support Hypothesis 1 of this study. Thus, these findings support Hypothesis 1 of this study.

The present study found a positive correlation between experiential avoidance and anxiety, consistent with previous findings26. Notably, the observed standardized regression weight (β = 0.532) exceeded the effect reported by Ådnøy et al. (β = 0.302)44. We attribute the magnitude difference to three methodological–developmental moderators. First, statistical power. Our analytic sample (N = 4058) is an order of magnitude larger than the Norwegian cohort (N = 364). Monte-Carlo work demonstrates that power ≥ 0.80 at N ≈ 3000 stabilizes regression estimates within ± 0.02 of the population parameter, thereby reducing downward bias induced by sampling error45. Second, instrument bandwidth. We administered the two-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-2), whereas Ådnøy employed the seven-item GAD-7. Longer scales parcel heterogenous facets (worry, somatic arousal, sleep disturbance), attenuating bivariate associations; brief, unidimensional screens heighten item redundancy with avoidance-oriented coping, inflating observed β coefficients. Third, developmental salience. Adolescence is characterized by rapid maturation of limbic circuitry coupled with protracted prefrontal refinement, rendering emotional regulation particularly labile8. Factors such as social pressure, family expectations, and academic demands significantly impact teenager mental health, often prompting the adoption of avoidant strategies. This age group typically lacks mature emotional expression and awareness skills, making it difficult for them to clearly identify and articulate their feelings when confronted with distress46. Individuals prone to emotional avoidance tend to ignore or evade their emotions rather than confront and adjust them, which may lead to emotional suppression and the accumulation of anxiety2.

The present findings indicate that BrainRot is significantly and positively associated with experiential avoidance, aligning with prior evidence47. Previous research has identified complex psychological mechanisms linking anxiety to BrainRot in teenagers. Anxiety not only drives teenagers to seek BrainRot as an escape mechanism through physiological and emotional regulation pathways but also exacerbates BrainRot dependence via social identification and cognitive biases28. Under the influence of anxiety, teenagers may be more inclined to use BrainRot to alleviate discomfort. Although this short-term escape may provide temporary relief, it fails to address the root causes of anxiety and may instead intensify it, creating a vicious cycle. Therefore, interventions targeting teenager anxiety, particularly those focused on cultivating healthy emotional regulation strategies and enhancing self-efficacy, could help reduce the risk of BrainRot addiction27. These findings support the hypothesis of this study that anxiety mediates the relationship between experiential avoidance and BrainRot. These findings support the hypothesis of this study that anxiety mediates the relationship between experiential avoidance and BrainRot. Second, the standardized path coefficient from anxiety to BrainRot in the current model was β = 0.134, which is noticeably smaller than the direct effect (β = 0.21) and total effect (β = 0.26) reported by Li et al. (2024) for short-video-application addiction on academic anxiety in a Chinese university sample4. Three methodological considerations may account for this discrepancy. Model complexity. The present structural model simultaneously incorporated multiple mediators (experiential avoidance → anxiety → BrainRot), moderators (gender, grade), and covariates (age, SES), thereby partitioning the explanatory power of anxiety into direct and several indirect routes. Li et al., by contrast, estimated a single-mediator model, which typically inflates the apparent direct effect. Anxiety phenotype. The GAD-2 index used here captures generalized, trait-like anxious affect, whereas Li et al. operationalized context-specific academic anxiety. Because short-form video overuse directly encroaches on study time and increases academic workload, domain-congruent anxiety scales naturally yield stronger path coefficients. Estimation framework. We employed the SPSS PROCESS macro (Model 6, 5000-bootstrap), a regression-based approach optimized for parsimonious path diagrams. Li et al. implemented full-information structural equation modeling with latent interaction terms, a procedure that can absorb measurement error into latent factors and, consequently, produce larger standardized effects. The above supports Research H2.

The present study identified a significant inverse association between physical exercise and anxiety (β = − 0.065, p < 0.01), a direction consistent with Chen et al. (β = − 0.101)48. Yet the magnitude we observed is modestly smaller. Three methodological discontinuities plausibly explain the 1. Attenuation. Instrument granularity. We assessed exercise with a concise scale indexing weekly frequency, average duration, and typical intensity. While efficient for large-scale surveys, this index omits modality diversity (moderate- vs. vigorous-intensity activities, leisure-time sport, active commuting) that may carry distinct psychobiological benefits. Chen et al. employed the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ), which samples multiple life domains (work, study, transport, recreation). Broader coverage increases reliability and, consequently, the strength of observed associations with mental-health outcomes. Sampling rigor, Our convenience sample, drawn from seven schools across five provinces, is vulnerable to selection bias and intra-cluster homogeneity. Chen et al. combined stratification, multistage clustering, and probability proportional-to-size sampling, yielding a demonstrably more representative cohort and stabilizing regression weights. Design tempo, Cross-sectional data, as used here, capture only contemporaneous covariance. Chen’s two-wave longitudinal design and three-month exercise intervention afforded stronger causal inference and allowed true score change to emerge, typically inflating standardized effects. Notwithstanding the smaller main effect, our moderation analysis revealed that physical exercise significantly buffered the link between experiential avoidance and anxiety (interaction β = –0.048, p < 0.01). teenagers reporting ≥ 3 sessions of moderate-to-vigorous activity per week exhibited a flatter avoidance–anxiety slope, corroborating recent evidence that sport participation enhances prefrontal inhibitory control and HRV-indexed emotional flexibility in psychologically vulnerable youth49. Regular physical activity may therefore operate as both a direct anxiolytic and a protective moderator, disrupting rumination cycles triggered by avoidance tendencies50. When teenagers experience anxiety or low mood due to experiential avoidance, physical exercise can serve as an effective emotional regulation strategy to restore psychological balance71. Therefore, physical exercise not only acts as a preventive and intervention measure against experiential avoidance and anxiety but also represents an essential pathway for enhancing emotional regulation capacity and mental health in teenagers72,73,74,75,76. These findings support the H3, highlighting the multifaceted benefits of physical exercise in promoting teenager well-being77,78,79,80,81,82,83.

Cross-sectional analyses revealed a significant, albeit modest, sex difference in anxiety: female participants reported higher mean levels than males (β = − 0.069, p < 0.01), replicating epidemiological surveys across cultures51. This divergence appears to be moderated by at least two psychosocial mechanisms. First, teenager females display a stronger proclivity for ruminative coping, which prolongs cortisol recovery and amplifies anticipatory worry52. Second, girls consistently endorse lower perceived social self-efficacy and fear negative interpersonal evaluation, both robust predictors of sustained anxiety symptomatology53. Conversely, males exhibited elevated scores on the BrainRot addiction index (β = 0.055, p < 0.001). Developmental research indicates that boys gravitate toward highly stimulating, game-like digital content (rapid scene cuts, amplified soundtracks, novelty-driven recommendation algorithms) that elicit phasic dopaminergic bursts in mesolimbic reward circuits54. Females, in contrast, predominantly utilize social media for relational maintenance and emotional disclosure, behaviours less compatible with compulsive, fragmentary video consumption55. Under academic or interpersonal stress, boys also default to avoidant–entertainment strategies, whereas girls mobilize social-support networks, further widening the gender gap in problematic short-form video use52,55. Age emerged as an additional risk gradient (β = 0.050, p < 0.001). Incremental scholastic demands and emerging career concerns encountered by older teenagers potentiate the use of immediate, low-cost mood-repair behaviours such as endless scrolling57. Grade level exerted a small but independent effect (β = 0.035, p < 0.05), reflecting greater smartphone ownership, discretionary screen time, and curricular pressure among senior students who deploy short-form videos as a situational escape from high-stakes examinations58,59. When these demographic moderators were simultaneously estimated within the moderated-mediation framework, the indirect effect of experiential avoidance on BrainRot via anxiety decreased from β = 0.190 reported in a single-mediator study to β = 0.13460. The contraction implies that sex, age, and grade account for appreciable heterogeneity in the avoidance → anxiety → addiction pathway. Targeted prevention protocols should therefore incorporate gender-sensitive emotional-regulation training and developmentally calibrated digital-media literacy to mitigate escalating BrainRot involvement across mid- to late adolescence.

The present study provides a comprehensive analysis of the relationships among experiential avoidance, anxiety, and BrainRot in teenagers. It extends the application of emotional regulation theory by constructing a model that elucidates how experiential avoidance contributes to BrainRot. Specifically, the study highlights the role of anxiety as a mediating factor, demonstrating how experiential avoidance exacerbates anxiety, which in turn leads to increased BrainRot. This finding offers a novel perspective on the impact of anxiety and avoidance behaviors on addictive tendencies, enriching the theoretical framework of emotional avoidance and addictive behaviors in psychology. By incorporating physical exercise as a moderating variable, the study further illustrates its effectiveness as an emotional regulation strategy. The findings suggest that fostering positive emotional regulation skills in teenagers, particularly through physical exercise to enhance self-efficacy, can reduce the risk of BrainRot. Thus, integrating physical exercise into school-based mental health programs and combining it with emotional regulation strategies could improve students’ mental health and quality of life.

Limitations

First, the cross-sectional nature of this study precludes causal inference. Although structural equation modeling provides estimates of directional pathways, the observed associations between experiential avoidance, anxiety, and BrainRot remain correlational. Whether heightened experiential avoidance precipitates addictive short-form video use, or vice versa, can only be disentangled through longitudinal or experimental designs. Second, all constructs were assessed with self-report instruments. While the scales selected exhibit satisfactory reliability and validity in Chinese teenagers, they are nonetheless vulnerable to social-desirability bias and retrospective recall error, potentially attenuating or inflating true effects. Third, convenience sampling was employed. Participants were recruited from seven well-resourced urban schools, thereby over-representing teenagers with high socioeconomic status and reliable internet access. Consequently, the prevalence of BrainRot may be underestimated, and the findings cannot be generalized to rural or socio-economically disadvantaged populations. Finally, heterogeneity across demographic subgroups (e.g., rural versus urban, high versus low physical activity) was not explored. The study was not powered for moderation analyses stratified by these factors, limiting the robustness and external validity of the conclusions. Future investigations should adopt probability sampling and purposely oversample under-represented groups to produce nationally estimable parameters.

Future directions

To redress the causal indeterminacy inherent in cross-sectional designs, future work should integrate multi-wave longitudinal panels with randomized controlled experiments. Latent growth-curve modelling and cross-lagged structural analyses can chart the temporal ordering of experiential avoidance, anxiety, and BrainRot, while brief acceptance-and-commitment or mindfulness-based interventions can isolate causal pathways through experimental manipulation. Representativeness can be improved by adopting stratified multistage cluster sampling that explicitly stratifies on region (e.g., coastal vs. interior provinces), school type (key vs. ordinary), and developmental stage (early, mid-, late adolescence). Embedding validated cognitive tasks (e.g., Stroop, delay-discounting) and passive digital-trace data (app-usage logs, clickstreams) would allow triangulation of self-reports with objective behavioural indicators, thereby mapping both the prevalence and the heterogeneity of BrainRot at the national level. Cross-cultural replication is essential. Comparative studies contrasting East-Asian collectivistic settings with Nordic individualistic welfare states could clarify how cultural norms (academic pressure, digital-media literacy curricula, outdoor-play traditions) moderate the threshold at which information overload is subjectively experienced as “low quality” and consequently pathogenic. Micro-level contextual factors also merit finer operationalisation. Future protocols should dissect physical activity along three axes—type (aerobic, resistance, mind–body), intensity (metabolic equivalents), and timing (school-day vs. weekend)—to determine which configurations most potently buffer the avoidance–anxiety–BrainRot cascade. Finally, adequately powered mega-samples (N > 15,000) should enable preregistered subgroup analyses intersecting gender, socioeconomic status, and baseline mental-health risk. Such segmentation will elucidate for whom digital-risk interventions are most cost-effective and will furnish policy-makers with precision-prevention roadmaps tailored to vulnerable youth sub-populations.

Conclusions

The present study provides a theoretical foundation for mental health interventions targeting teenagers by thoroughly examining the relationships among experiential avoidance, anxiety, and BrainRot. It also offers practical guidance for developing effective intervention strategies. The findings suggest that interventions such as physical exercise have the potential to help teenagers better regulate their emotions, mitigate the impact of negative emotions, and reduce the risk of addictive behaviors.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due our experimental team’s policy but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Wolgast, M., Lundh, L.-G. & Viborg, G. Experiential avoidance as an emotion regulatory function: An empirical analysis of experiential avoidance in relation to behavioral avoidance, cognitive reappraisal, and response suppression. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 42, 224–232 (2013).

Park, C. L. et al. Development of emotion regulation across the first two years of college. J. Adolesc. 84, 230–242 (2020).

Huang, D. Q. characteristics of college students’ cognitive emotion regulation strategies and its pedagogical implications. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi = Zhonghua Liuxingbingxue Zazhi 41, 1151–1154 (2020).

Yam, F. C., Köksal, B. & Yildirim, O. Anxiety and experiential avoidance among university students: The serial mediating role of optimism and self-compassion. J. Ration. Emot. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 43, 1 (2024).

Pantesco, E. J., Schanke, M. R. Pre-sleep arousal and poor sleep quality link experiential avoidance to depressive symptoms in young adults. J. Health Psychol. 13591053241302136 (2024).

Shi, R., Zhang, S., Zhang, Q., Fu, S. & Wang, Z. Experiential avoidance mediates the association between emotion regulation abilities and loneliness. PLoS ONE 11, e0168536 (2016).

Seligowski, A. V., Lee, D. J., Bardeen, J. R. & Orcutt, H. K. Emotion regulation and posttraumatic stress symptoms: A meta-analysis. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 44, 87–102 (2015).

Gan, Y. et al. A chain mediation model of physical exercise and BrainRot behavior among adolescents. Sci. Rep. 15, 17830 (2025).

‘brainrot’ is the new online affliction—the new york times. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/06/13/style/brainrot-internet-addiction-social-media-tiktok.html. Accessed 16 Feb 2025.

What is brain rot, the oxford university press 2024 word of the year? https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cx2n2r695nzo. Accessed 16 Feb 2025.

Qin, Y., Omar, B. & Musetti, A. The addiction behavior of short-form video app TikTok: The information quality and system quality perspective. Front. Psychol. 13, 932805 (2022).

Firth, J. A., Torous, J. & Firth, J. Exploring the impact of internet use on memory and attention processes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17, 9481 (2020).

Understanding digital dementia and cognitive impact in the current era of the internet: a review—PMC. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11499077/. Accessed 19 Sept 2025.

Xie, J. et al. The effect of short-form video addiction on undergraduates’ academic procrastination: A moderated mediation model. Front. Psychol. 14, 1298361 (2023).

Chen, Y., Zhang, W., Zhong, N. & Zhao, M. Motivations behind problematic short video use: A three-level meta-analysis. Telemat. Inform. 95, 102196 (2024).

The Development Report on China’s Short-Video Industry (2024) released. [Online] Available: https://m.bjnews.com.cn/detail/1735552574168995.html. Accessed 16 Feb 2025.

Porter JY. Cognitive-behavioral theories. In Counseling Theory: Guiding Reflective Practice, 229–252 (Sage Publications, Inc, Thousand Oaks, CA, US, 2014).

Yue, H., Yang, G., Bao, H., Bao, X. & Zhang, X. Linking negative cognitive bias to short-form video addiction: The mediating roles of social support and loneliness. Psychol. Sch. 61, 4026–4040 (2024).

Xu, Z., Gao, X., Wei, J., Liu, H. & Zhang, Y. Adolescent user behaviors on short video application, cognitive functioning and academic performance. Comput. Educ. 203, 104865 (2023).

Yi, Z., Wang, W., Wang, N. & Liu, Y. The relationship between empirical avoidance, anxiety, difficulty describing feelings and internet addiction among college students: A moderated mediation model. J. Genet. Psychol. 15, 1–17 (2025).

Cowden, R. G., Chapman, I. & Houghtaling, A. Additive, curvilinear, and interactive relations of anxiety and depression with indicators of psychosocial functioning. Psychol. Rep. 124, 627–650 (2021).

Hartley, C. A. & Phelps, E. A. Anxiety and decision-making. Biol. Psychiatry. 72, 113–118 (2012).

Racine, N. et al. Global prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents during COVID-19: A meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 175, 1142–1150 (2021).

Wang, X. & Liu, Q. Prevalence of anxiety symptoms among Chinese university students amid the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysisCOVID-19. Heliyon 8, e10117 (2022).

Hofmann, S. G., Sawyer, A. T., Fang, A. & Asnaani, A. Emotion dysregulation model of mood and anxiety disorders. Depress Anxiety 29, 409–416 (2012).

Epkins, C. C. Experiential avoidance and anxiety sensitivity: Independent and specific associations with children’s depression, anxiety, and social anxiety symptoms. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess 38, 124–135 (2016).

Zhang, L. et al. The relationship between personality and short video addiction among college students is mediated by depression and anxiety. Front Psychol. 15, 1465109 (2024).

Peng, C., Lee, J.-Y. & Liu, S. Psychological phenomenon analysis of short video users’ anxiety, addiction and subjective well-being. Int. J. Contents 18, 27–39 (2022).

Carpallo-González, M., Muñoz-Navarro, R., González-Blanch, C. & Cano-Vindel, A. Symptoms of emotional disorders and sociodemographic factors as moderators of dropout in psychological treatment: A meta-review. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 23, 100379 (2023).

Schunk, D. H. & Pajares, F. Self-efficacy theory. In Handbook of Motivation at School, 35–53(Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group, New York, 2009).

Anderson, E. & Durstine, J. L. Physical activity, exercise, and chronic diseases: A brief review. Sports Med. Health Sci. 1, 3 (2019).

Salmon, P. Effects of physical exercise on anxiety, depression, and sensitivity to stress: A unifying theory. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 21, 33–61 (2001).

Mao, Z. & Jiang, Y. Z. The relationship between extraversion, loneliness, and problematic short-video use among adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Chin. J. Health Psychol. 31(7), 700–705 (2023).

Mao, Z. & Jiang, Y. Z. The impact of neuroticism on problematic short-video use: The chain mediating role of loneliness and boredom propensity. Chin. J. Health Psychol. 31(4), 440–446 (2023).

Huang, C. H. et al. Development of the adolescent executive function scale. Chin. J. Behav. Med. Brain Sci. 23, 463–465 (2014).

Fledderus, M., Oude Voshaar, M. A. H., Ten Klooster, P. M. & Bohlmeijer, E. T. Further evaluation of the psychometric properties of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II. Psychol Assess 24, 925–936 (2012).

Cao, J., Ji, Y. & Zhu, Z. H. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II among college students. Chin. Ment. Health J. 27(11), 873–877 (2013).

Byrd-Bredbenner, C., Eck, K. & Quick, V. GAD-7, GAD-2, and GAD-mini: Psychometric properties and norms of university students in the United States. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry. 69, 61–66 (2021).

Liang, D. Q. The relationship between stress levels and physical exercise among college students. Chin. J. Psychol. Health (1994).

Kim, H.-Y. Statistical notes for clinical researchers: assessing normal distribution (2) using skewness and kurtosis. Restor. Dent. Endod. 38, 52–54 (2013).

Wang, J. et al. Physical activity moderates the mediating role of depression between experiential avoidance and internet addiction. Sci. Rep. 15, 20704 (2025).

McNicol, M. L. & Thorsteinsson, E. B. Internet addiction, psychological distress, and coping responses among adolescents and adults. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 20, 296–304 (2017).

Gao, Y. et al. Neuroanatomical and functional substrates of the short video addiction and its association with brain transcriptomic and cellular architecture. Neuroimage 307, 121029 (2025).

Ådnøy, T., Solem, S., Hagen, R. & Havnen, A. An empirical investigation of the associations between metacognition, mindfulness experiential avoidance, depression, and anxiety. BMC Psychol. 11, 281 (2023).

Fraley, R. C. & Vazire, S. The N-pact factor: Evaluating the quality of empirical journals with respect to sample size and statistical power. PLoS ONE 9, (2014).

Silvers, J. A. Adolescence as a pivotal period for emotion regulation development. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 44, 258–263 (2022).

Debra, G., Michels, N. & Giletta, M. Cognitive control processes and emotion regulation in adolescence: examining the impact of affective inhibition and heart-rate-variability on emotion regulation dynamics in daily life. Dev. Cognit. Neurosci. 70, 101454 (2024).

Li, G., Geng, Y. & Wu, T. Effects of short-form video app addiction on academic anxiety and academic engagement: The mediating role of mindfulness. Front Psychol. 15 (2024).

Chen, X. et al. The effect of physical activity on anxiety through sleep quality among Chinese high school students: evidence from cross-sectional study and longitudinal study. BMC Psychiatry 25, 495 (2025).

Lubans, D. et al. Physical activity for cognitive and mental health in youth: A systematic review of mechanisms. Pediatrics 138, e20161642 (2016).

Masklavanou, C., Triantafyllou, K., Paparrigopoulos, T., Sypsa, V. & Pehlivanidis, A. Internet gaming disorder, exercise and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: The role of symptoms of depression, anxiety and stress. Psychiatr Psychiatr. 34, 13–20 (2023).

Bao, C. & Han L. Gender difference in anxiety and related factors among adolescents. Front Public Health 12 (2025).

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. Emotion regulation and psychopathology: The role of gender. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 8, 161–187 (2012).

Hyde, J. S., Mezulis, A. H. & Abramson, L. Y. The ABCs of depression: Integrating affective, biological, and cognitive models to explain the emergence of the gender difference in depression. Psychol. Rev. 115, 291–313 (2008).

Montag, C., Lachmann, B., Herrlich, M. & Zweig, K. Addictive features of social media/messenger platforms and freemium games against the background of psychological and economic theories. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16, 2612 (2019).

Andreassen, C. S., Pallesen, S. & Griffiths, M. D. The relationship between addictive use of social media, narcissism, and self-esteem: Findings from a large national survey. Addict. Behav. 64, 287–293 (2017).

Kuss, D. J. & Griffiths, M. D. Social networking sites and addiction: Ten lessons learned. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 14, 311 (2017).

Hou, F., Bi, F., Jiao, R., Luo, D. & Song, K. Gender differences of depression and anxiety among social media users during the COVID-19 outbreak in China: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 20, 1648 (2020).

Gu, X., Hassan, N. C., Sulaiman, T., Wei, Z. & Dong, J. The impact of video game playing on Chinese adolescents’ academic achievement: Evidence from a moderated multi-mediation model. PLoS ONE 19, e0313405 (2024).

Andreassen, C. S. & Pallesen, S. Social network site addiction—an overview. Curr. Pharm. Des. 20, 4053–4061 (2014).

Liu Y, Jin Y, Chen J, Zhu L, Xiao Y, Xu L, Zhang T. Anxiety, inhibitory control, physical activity, and internet addiction in Chinese adolescents: a moderated mediation model. BMC Pediatr. 24, (1) 663. (2024).

Liu, Y. et al. The Mediating Role of Inhibitory Control and the Moderating Role of Family Support Between Anxiety and Internet Addiction in Chinese Adolescents. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. (2024).

Xiao T, Pan M, Xiao X, Liu Y. The relationship between physical activity and sleep disorders in adolescents: a chain-mediated model of anxiety and mobile phone dependence. BMC Psychol. 12, (1) 751. (2024).

Liu Y, Peng J, Ding J, Wang J, Jin C, Xu L, Zhang T, Liu P. Anxiety mediated the relationship between bullying victimization and internet addiction in adolescents, and family support moderated the relationship. BMC Pediatr. 25, (1) 8. (2025).

Wang W, Wang J, Liu Y, Deng L. Exploring the relationship between physical activity and social media addiction among adolescents through a moderated mediation model. Sci Rep.15, (1) 22209. (2025).

Wang, J., Wang, N., Liu, Y. & Zhou, Z. Experiential Avoidance, Depression, and Difficulty Identifying Emotions in Social Network Site Addiction Among Chinese University Students: A Moderated Mediation Model. Behav. Inf. Technol. (2025).

Liu Y, Yin J, Xu L, Luo X, Liu H, Zhang T. The Chain Mediating Effect of Anxiety and Inhibitory Control and the Moderating Effect of Physical Activity Between Bullying Victimization and Internet Addiction in Chinese Adolescents. J Genet Psychol. 186, (5) 397–412. (2025).

Wang J, Wang N, Qi T, Liu Y, Guo Z. The central mediating effect of inhibitory control and negative emotion on the relationship between bullying victimization and social network site addiction in adolescents. Front Psychol. 15 1520404. (2025).

Shen Q, Wang H, Liu M, Li H, Zhang T, Zhang F, Wang S, Liu Y, Deng L. The impact of childhood emotional maltreatment on adolescent insomnia: a chained mediation model. BMC Psychol. 13, (1) 506. (2025).

Liu Y, Duan L, Shen Q, Ma Y, Chen Y, Xu L, Wu Y, Zhang T. The mediating effect of internet addiction and the moderating effect of physical activity on the relationship between alexithymia and depression. Sci Rep.14, (1) 9781. (2024).

Wang J, Xiao T, Liu Y, Guo Z, Yi Z. The relationship between physical activity and social network site addiction among adolescents: the chain mediating role of anxiety and ego-depletion. BMC Psychol.13, (1) 477. (2025).

Liu, Y., Xiao, T., Zhang, W., Xu, L. & And Zhang, T. The Relationship Between Physical Activity and Internet Addiction Among Adolescents in Western China: A Chain Mediating Model of Anxiety and Inhibitory Control. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 29, 1602–1618 (2024).

Peng J, Wang J, Chen J, Li G, Xiao H, Liu Y, Zhang Q, Wu X, Zhang Y. Mobile phone addiction was the mediator and physical activity was the moderator between bullying victimization and sleep quality. BMC Public Health. 25, (1) 1577 (2025).

Shen Q, Wang S, Liu Y, Wang Z, Bai C, Zhang T. The chain mediating effect of psychological inflexibility and stress between physical exercise and adolescent insomnia. Sci Rep. 14, (1) 24348. (2024).

Liu Y, Xiao T, Zhang W, Xu L, Wang Y, Zhang T. The relationship between family support and Internet addiction among adolescents in Western China: the chain mediating effect of physical exercise and depression. BMC Pediatr. 25, (1) 397 (2025).

Yi Z, Wei L, Xu L, Pang W, Liu Y. Chain-mediation effect of cognitive flexibility and depression on the relationship between physical activity and insomnia in adolescents. BMC Psychol. 13 (1), 587 (2025).

Peng J, Liu Y, Wang X, Yi Z, Xu L, Zhang F. Physical and emotional abuse with internet addiction and anxiety as a mediator and physical activity as a moderator. Sci Rep. 15, (1) 2305 (2025).

Luo X, Liu H, Sun Z, Wei Q, Zhang J, Zhang T, Liu Y. Gender mediates the mediating effect of psychological capital between physical activity and depressive symptoms among adolescents. Sci Rep. 2025 Mar 29;15(1):10868. doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-95186-5. Erratum in: Sci Rep. 15, (1) 26073 (2025).

Jia W, Zhang X, Ma Y, Yan G, Chen Y, Liu Y. Physical exercise moderates the mediating effect of depression between physical and psychological abuse in childhood and social network addiction in college students. Sci Rep. 15, (1) 17869 (2025).

Yang L, Liu Y, Yan C, Chen Y, Zhou Z, Shen Q, Zhang F, Zhang T, Liu Z. The Relationship Between Early Warm and Secure Memories and Healthy Eating Among College Students: Anxiety as Mediator and Physical Activity as Moderator. Psychiatry. 1–20. (2025).

Yang L, Wang N, Li D, Zhao X, Wen M, Zhang Y, Liu Y. Social support and anxiety, a moderated mediating model. Sci Rep. 15, (1) 29390 (2025).

Yin J, Cheng X, Yi Z, Deng L, Liu Y. To explore the relationship between physical activity and sleep quality of college students based on the mediating effect of stress and subjective well-being. BMC Psychol. 13, (1) 932. (2025).

Peng J, Liu M, Wang Z, Xiang L, Liu Y. Anxiety and sleep hygiene among college students, a moderated mediating model. BMC Public Health. 25, (1) 3233 (2025).

Fang, J. et al. A Chain Mediation Model for Psychological Maltreatment and Adolescents Social Media Dependence. Child Abus. Rev. 34, e70069 (2025).

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the colleagues from Chengdu Sport University for providing the ethical review.

Funding

2023 Guangxi Higher Education Institutions Basic Ability Enhancement Project for Young and Middle-aged Teachers (2023KY0585). Xichang Social Sciences Association; The achievements of the planning project of the Liangshan Prefecture Ethnic Culture Research Fund (SKL202545).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jinyin Peng1245, Ziyuan Quan2456, Chuqi Yan125, Junwei Dong15, Zhiyu Chen356, Pingfan123456. 1. Conceptualization; 2. Methodology; 3. Data curation; 4. Writing—Original Draft; 5. Writing—Review & Editing; 6. Funding acquisition.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by Ethics Committee of Chengdu Physical Education University (2024–68). Informed consent was obtained from the participants and their guardians before the start of the program. We confirm that all the experiment is in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations such as the declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Clinical Trial Number

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Peng, J., Quan, Z., Yan, C. et al. Physical exercise moderated the mediating role of anxiety between experiential avoidance and the teenagers BrainRot. Sci Rep 15, 40737 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24472-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24472-z