Abstract

Mechanized strawberry transplanting is essential for improving operational efficiency and reducing seedling damage. To address these challenges, this study designed an automatic seedling pick-up device specifically for strawberry transplanters. Firstly, a novel clamp-type picking claw was developed based on the mechanical characteristics analysis of strawberry seedlings extracted from the tray. Based on the operational principles of whole-row seedling extraction, equidistant separation, and precise placement, the structure and working mechanism of the picking-and-placing device were designed. Secondly, a dynamic model of the picking claw was established for kinematic analysis based on coupled EDEM-RecurDyn simulation. The strawberry seedling picking process was conducted to investigate the effects of needle spacing, picking acceleration, and insertion depth on the integrity ratio of the plug seedlings. Finally, an orthogonal experimental design was employed, integrating single-factor tests, analysis of variance, response surface methodology, and multi-objective optimization. The results showed that the optimal seedling picking parameters were picking acceleration of 0.26 m/s2, claw spacing of 37 mm, and insertion depth of 85 mm. With these parameters, field validation experiments demonstrated a relative error of 4.29% between the measured and predicted plug seedling integrity ratio, which confirmed the reliability of the optimized parameters. This research significantly contributes to improving plug seedling integrity during mechanical transplanting and enhances the efficiency and effectiveness of strawberry transplantation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, the strawberry industry has developed rapidly, with cultivated areas expanding continuously; it is now the second most widely cultivated and produced berry worldwide1,2. Strawberries are rich in essential nutrients and contain particularly high levels of vitamin C and folate3. Strawberry cultivation offers significantly higher economic returns than most vegetable crops, representing a high-value enterprise that substantially increases farmers’ incomes4,5. China is both the world’s largest strawberry producer and its foremost consumer6; nevertheless, the mechanization of strawberry production has progressed slowly7.As the core component of a transplanter, the seedling pick-up mechanism’s structure and operating parameters directly determine the overall operational performance of the machine8,9,10,11,12.To address these challenges, several research pathways have been explored. Zhang et al. developed a closed multi-channel pneumatic seedling-picking device integrated with a specialized tray system to address issues such as complex structure, high seedling damage, and low picking efficiency in fully automatic vegetable transplanters13; Han et al. proposed a novel seedling-extraction mechanism that combines air-jet assistance with gentle stem clamping to reduce direct gripping damage and improve transplanting efficiency14; Yang et al. developed an integrated probing-type transplanting mechanism specifically designed for potted strawberry seedlings. The mechanism employs a soil-clamp design to minimize seedling injury and was optimized based on agronomic requirements; its feasibility was verified through high-speed photography15; Xu et al. proposed a fully automatic strawberry plug seedling transplanting mechanism based on a non-circular planetary gear train driven by Hermite-interpolated pitch curves. According to the working principle of the transplanting mechanism, a kinematic theoretical model was established. Using computer-aided optimization software, a set of mechanism parameters satisfying transplanting requirements was obtained and the rationality of the design was verified via high-speed photography16; Liu et al. developed a dual-claw end-effector tailored to the large seedling size, elongated plug seedling, and arch-back orientation requirements of strawberry plug seedlings. The device integrates synchronized reorientation and variable-spacing functions. The authors noted that excessive acceleration may cause needle slippage and fracture of the lower root plug seedling, yet no further investigation of the seedling damage rate was conducted17.

While the aforementioned studies have contributed valuable mechanisms for automated transplanting, these studies exhibit several limitations that hinder their widespread application, particularly for delicate strawberry plug seedlings. Pneumatic ejection devices13 often require dedicated and complex tray systems, which increase costs and reduce operational flexibility. Stem-clamping mechanisms14 may cause damage to the fragile hypocotyls of strawberry seedlings. Although the integrated probing-type mechanism15 and the non-circular planetary gear train design16 are innovative, they involve an excessive number of components, resulting in complex structures, high manufacturing costs, and potential reliability issues under field conditions. Similarly, the dual-claw end-effector17 identified issues with acceleration-induced damage but did not quantify or optimize for the seedling integrity ratio.

Therefore, this study aims to address the aforementioned limitations by developing a cylinder-driven “plug-clamping” picking claw, which embodies three core innovations: (1) A simplified and robust electro-pneumatic architecture: Based on the principles of whole-row extraction, equidistant separation, and precise placement, this design replaces the complex multi-channel pneumatic systems13 and mechanical gear trains16 with a precisely controlled mechanism that combines sensor feedback for accuracy and pneumatic power for gripping. This hybrid approach enhances reliability and avoids the failure modes of all-pneumatic or all-mechanical systems. (2) Enhanced adaptability and inherent damage reduction: The four-needle, insert-and-grip approach clamps the substrate rather than the stem, avoiding the damage risks of the stem14 and accommodating standard trays without the need for dedicated systems13. (3) Quantified optimization for integrity: Addressing the unmet need from Liu17, the plug seedling integrity ratio is prioritized as the core metric. Through coupled EDEM-RecurDyn simulation and RSM optimization, transplanting damage is systematically minimized. The end-effector’s structural parameters were specifically designed and optimized to account for the unique morphology of strawberry seedlings, ensuring adequate clamping force while minimizing damage through theoretical modeling, coupled simulation, and experimentation.

Materials and methods

Strawberry plug seedling pulling test

This study employed a stem-clamping method to measure the pull-out force required for strawberry plug seedlings. During the test, the seedling stem was vertically secured with a stem clamp, ensuring its alignment with the horizontal plane. The bottom of the plug tray was firmly affixed to the test surface to prevent upward displacement during the pulling process.A pulling speed of 0.5 mm/s and a pull-out height of 35 mm were set, with the stem being gripped and lifted upward until the entire root plug was extracted from the plug tray. The maximum pull-out force was recorded throughout the process, and the test was repeated twelve times to ensure statistical reliability18. The experimental setup is illustrated in Fig. 1. The repeated tests are illustrated in Fig. 2a.

The test was repeated twelve times, yielding a maximum pull-out force of 3.42 N. Figure 2b presents the resulting force–displacement curve recorded during the plug extraction. The detachment process can be divided into three distinct stages: Stage I—Initial pull-out: from the onset of the test until the peak force Fmax is reached, the relationship between pull-out force and displacement is non-linear. During this phase the strawberry plug was gradually stretched; tension among the root hairs loosens the substrate. When the force attains its maximum value Fmax the seedling is released from the plug tray. If the plug remains intact and shows no visible damage, the operation is considered successful, and Fmax is defined as the detachment force. Stage II—Progressive separation: adhering roots detach progressively from the plug tray walls. As displacement increases, the pull-out force declines steadily and eventually approaches a stable value. Stage III—Complete separation: the plug is fully extracted from the tray and the pull-out force levels off, corresponding to the combined weight of the seedling and its root plug.

Design of the seedling Pick-up device for the fully automatic strawberry transplanter

A 32 plug tray was selected for this study. The center-to-center distance between adjacent cells is 65 mm, and the span of five cells (4 × 65 mm = 260 mm) matches the required row spacing for strawberry cultivation. Therefore, a staggered two-row picking pattern was adopted: the four left picking claws harvest rows 1 ~ 4, while the four right claws harvest rows 5 ~ 8. After simultaneous extraction, the eight seedlings are positioned above eight duck-foot planters, which insert them into the soil. Only four indexing motions of the tray feed mechanism are needed to transplant an entire tray.Strawberry seedlings exhibit a pronounced “arch-back” (the curved crown). To comply with agronomic practice, seedlings must be planted with the arch facing the outer side of the ridge so that the fruit hangs on both sides. This orientation improves light exposure, fruit colour, cleanliness and disease resistance, and simplifies picking19. Accordingly, during propagation, seedlings in rows 1–4 are oriented with their arch-backs toward one side of the tray, and seedlings in rows 5–8 toward the opposite side, as illustrated in Fig. 3.

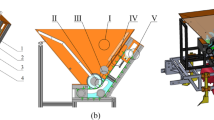

As shown in Fig. 4, the seedling pick-up device comprises the following main components: Drive motor, picking claws, strawberry seedlings, plug-tray fixture, plug tray, longitudinal tray feed mechanism, transverse tray feed mechanism, claw-spreading mechanism, Lifting track of the seedling claw, transverse tray feed mechanism, rod-less cylinder and claw lifting mechanism, etc. The eight picking claws are arranged in left and right groups; adjacent claws are connected by stainless-steel cables and are gathered or spread by the horizontal motion of a rod-less cylinder.

Working principle of the seedling-picking device: the claw lifting mechanism together with the longitudinal tray feed mechanism positions the picking claws 10 mm above the plug tray; the picking cylinders then actuate so that the picking claw grips the strawberry plug seedling. Next, the claw lifting mechanism raises the claws to a preset height, after which the rod-less cylinder spreads them to the required spacing. The picking claw is lifted by the claw-lifting mechanism and positioned above the planter, after the strawberry seedling is released into the planter, the picking claws then returns to its initial position.The picking claws first extract seedlings from rows 1 and 5, then proceed sequentially toward the rear rows.The strawberry transplanting workflow was illustrated in Fig. 5.

Structure of the Seedling pick-up device. (1) Drive motor; (2) Picking claws; (3) Strawberry seedlings; (4) Plug-tray fixture; (5) Plug tray; (6) Longitudinal tray feed mechanism; (7) Transverse tray feed mechanism; (8) Claw-spreading mechanism; (9) Lifting track of the seedling claw; (10) Transverse tray feed mechanism; (11) Rod-less cylinder; (12) Claw lifting mechanism.

Design of the strawberry seedling picking claw

Because the picking claw makes direct contact with the substrate of the plug seedling, its geometry and the clamping force it exerts on the substrate have a decisive impact on the quality of both extraction and release operations. The two most commonly adopted claw configurations in current practice are the stem-clamping type20,21 and the insert-and-grip type22,23. During insertion into the substrate, the insert-and-grip configuration is able to contract inward simultaneously, thereby applying an effective preload to the plug seedling. This feature markedly enhances overall transplanting stability. In terms of the number of picking needles, a four-needle claw provides a tighter, greater friction against the substrate than two needles or three needles designs, based on the above analysis, a four-needle gripper is employed to achieve stable and efficient seedling extraction.

As shown in Fig. 6, the picking claw consists primarily of a picking cylinder, cylinder mounting plate, upper claw needle pressure plate, claw needle mounting plate, claw needles, back plate, and claw needle limiting plate.The claw needles are fixed by the claw needle limiting plate and can rotate around the claw needle mounting plate, thereby achieving the function of clamping while inserting.To maximize picking efficiency, the claw width is set equal to the plug tray spacing-65 mm. The claw must penetrate the plug seedling without destroying the soil structure or allowing the seedling to drop. Consequently, the needles must possess both sufficient rigidity and flexibility: they must compact the soil slightly on entry while providing the grip and friction required for extraction.Needle diameter and plug seedling damage are positively correlated. After evaluating 1 mm, 2 mm, and 3 mm needles, the 1 mm needle proved too slender and prone to bending, while the 3 mm needle, though capable of extracting the plug seedling, sacrificed centering accuracy. Balancing plug seedling protection and precise positioning, a 2 mm needle was selected as optimal.

The force exerted on the plug seedling by the picking claw during transplanting significantly affects strawberry seedling establishment, so the claw’s structure must be rationally designed and its structural and operating parameters optimized to enhance transplanting quality.Because the four needle claws bear equal forces, the analysis is simplified by considering only the forces exerted by two symmetric pairs of claws on the plug seedling. Figure 7 presents the force analysis of the plug seedling at the instant the picking claw grips it and begins to pull it upward. In the figure, \(\:\theta\), L, and h denote the initial needle angle, spacing, and insertion depth when the claw is in its starting position. FN1 and FN2 are the normal support forces exerted by the needles on the plug seedling, while Ff1 and Ff2 represent the static friction forces at the contact surfaces between the needles and the plug seedling.

Assuming that the plug seedling material satisfies the assumptions of continuity, homogeneity, and isotropy in mechanics of materials, then:

To ensure successful seedling pickup, the following condition must be satisfied:

In summary, the following can be derived:

In the formula: µ is the static friction coefficient; FT is the seedling extraction force, N; Z is the total resistance force, N; FJ is the maximum cohesive force that the substrate can provide, N.

Equation (3) shows that the plug seedling can be extracted only when the extraction force FT exceeds the total resistance Z. In practice, FT is constrained by agronomic conditions; for strawberry plug seedlings, the maximum pull-out force is 3.42 N. To guarantee successful pickup, the grip force exerted by the pneumatic cylinder must therefore exceed this value, yet it must not be so large as to damage the plug seedling. Analysis reveals that the stresses on the strawberry plug seedling are governed by several factors—including the pickup-needle angle, the extraction acceleration, and the insertion depth of the needles, jointly influence the seedling-extraction process.

Simulation analysis of the seedling Pick-up process based on EDEM–RecurDyn coupling

To overcome the limitations of EDEM software, researchers have adopted a coupled simulation approach that integrates the discrete element method (DEM) with multibody dynamics (MBD)24,25, this chapter establishes a virtual prototype of the pick-up claw through EDEM–RecurDyn co-simulation. The gripping process of the plug seedling is simulated, and the structural design is optimized with the integrity ratio of the plug seedling used as the evaluation criterion, providing a theoretical basis for improving pick-up quality and device refinement.

Dynamics modeling of the picking claw based on recurdyn

In SolidWorks, the pick-up claw is fully modeled and assembled. Since the four needle claws are the critical functional elements, the claw assembly can be simplified by omitting bolts, washers, picking cylinders, and other non-essential parts. The simplified claw consists only of the back plate, upper claw needle pressure plate, claw needle mounting plate, and the four claw needles. After assembly, the model is exported in Parasolid (.x_t) format for import into RecurDyn to build the dynamic model. Within RecurDyn, the assembly must be assigned mass properties, constrained with appropriate joints, and loaded with the forces required for the simulation.

In accordance with the actual motion requirements, appropriate joints are applied between the claw components within RecurDyn. A fixed joint is imposed on the plug seedling. As no relative motion is expected among the upper claw needle pressure plate, claw needle mounting plate, and the claw needles, these parts are merged into a single rigid body. Finally, a solid-to-solid contact is defined between the back plate and the merged needle assembly to capture their mechanical interaction. A solid-to-solid contact is then defined between the back plate and the merged needle assembly. Drives of type Displacement (time) are applied to the translational joint between the claw needle mounting plate and the back plate, as well as to the translational joint between the back plate and ground.

EDEM model and contact parameter settings

The plug seedling particle model established in this study incorporates cohesive bonding between particles; the JKR model is therefore adopted to accurately capture the adhesive behavior of moist, cohesive particles26,27. To investigate the causes of plug seedling fracture during the claw-gripping process through simulation, the substrate particles must be modeled with realistic size and shape. Because the basic particle geometry in EDEM is spherical, this study adopts spherical particles as the basic model.Strawberry plug seedling substrate particles were modeled with a particle radius of 1 mm and a bond radius of 1.3 mm; the resulting particle model is illustrated in Fig. 8.

Establishment of the EDEM–RecurDyn coupled model

In RecurDyn’s External SPI module, the wall geometry is created and exported, then imported into EDEM. After launching the coupled simulation, the time step is set, the coupling interface is activated, and the co-simulation proceeds. The key DEM parameters required for the coupled simulation are listed in Table 128,29,30,31.

During the interaction with the plug seedling, the claw needles, which exhibit negligible deformation and are thus modeled as rigid bodies, are capable of rotating within the needle mounting plate and are constrained by the needle limit plate to perform the clamping and seedling grasping operation, as illustrated in Fig. 6, while the plug tray is fully fixed in the simulation to mimic its clamped state in the transplanter, ensuring no displacement during the picking process.

Results and discussion

Preliminary single-factor experiments and result analysis

During strawberry transplanting, survival rates drop sharply when the plug seedling integrity falls below 50%32; therefore, the substrate integrity ratio is chosen as the criterion for evaluating pick-up success. This ratio is defined as the mass of substrate lost during the gripping operations divided by the total initial mass of the plug seedling.To evaluate the plug seedling integrity ratio, the Grid Bin Group module in EDEM’s post-processor is employed to tally the mass of particles that have detached from the plug seedling cavity, as illustrated in Fig. 9. Record the initial plug seedling mass for this trial as m1, and designate the mass of particles that fall back into the cell cavity as m₀. The following occurrences are deemed pickup failures: the plug seedling is not extracted at all, drops during extraction if the mass of substrate detached exceeds one-third of the total plug seedling mass. The calculation is given below:

In the formula: W is the plug seedling integrity ratio, %; m1 is the initial plug seedling mass, kg; m0 is the mass of detached particles, kg.

As they are driven pneumatically, the claw needles experience different accelerations under varying air pressures. To investigate how operating parameters affect transplanting performance, single-factor simulations were conducted with needle spacing (32–40 mm), seedling-extraction acceleration (0.1–0.5 m /s2) and insertion depth (60–100 mm) as the factors and plug seedling integrity ratio as the response.

Based on existing studies and relevant literature, the single-factor experiments were defined as follows: needle spacing 32 to 40 mm, seedling extraction acceleration 0.1 to 0.5 m/s2, and insertion depth 60 to 100 mm. During the simulations, the baseline parameter set was fixed at 36 mm needle spacing, 0.3 m/s2 extraction acceleration, and 80 mm needle stroke. In each group, the experiments were replicated three times. Two factors were held constant while the third was varied to investigate its individual influence on plug seedling integrity ratio.

Analysis of the influence of needle spacing on plug seedling integrity ratio

Keeping the insertion depth at 80 mm and the extraction acceleration at 0.3 m/s2, simulations were carried out for needle spacings of 32 mm, 34 mm, 36 mm, 38 mm, and 40 mm; the results are presented in Fig. 10a.The plug seedling integrity ratio first rises and then falls as needle spacing increases, reaching its maximum at 36 mm. Simulation trials show that at 40 mm the needles overextend and damage the plug seedling, causing plug fracture, while at 32 mm the needles are so close that they cross during closure, also leading to plug seedling breakage.Therefore, the optimal needle spacing range is 34 to 38 mm.

Analysis of the influence of seedling extraction acceleration on plug seedling integrity ratio

With the needle spacing set to 36 mm and needle stroke to 80 mm, simulations were conducted at extraction accelerations of 0.1 m/s2, 0.2 m/s2, 0.3 m/s2, 0.4 m/s2, and 0.5 m/s2; the results are illustrated in Fig. 10b.

At low acceleration values, differences in plug seedling integrity ratio are negligible; however, once acceleration exceeds a certain threshold, the plug seedling integrity ratio declines markedly with further increases in acceleration. Force analysis of the picking claw indicates that, for a given plug mass, higher acceleration subjects the plug seedling to greater impact forces and increases the stress within the needle-encapsulated zone. Such abrupt extraction and deceleration readily fracture the plug seedling and thereby lower transplant quality. Consequently, the optimal acceleration range is 0.1–0.3 m/s2.

Analysis of the influence of insertion depth on plug seedling integrity ratio

With the needle spacing set at 36 mm and extraction acceleration at 0.3 m/s2, simulations were performed for insertion depths of 60 mm, 70 mm, 80 mm, 90 mm, and 100 mm; the results are shown in Fig. 10c.

During the gripping process, increasing the insertion depth enlarges the inward-contracting displacement of the claw needles, which enhances their ability to extract the plug seedling from the cavity. However, once the insertion depth exceeds a certain threshold, the plug seedling undergoes pronounced compressive deformation and the substrate particles begin to move laterally, leading to substrate loss and a marked drop in plug seedling integrity. Consequently, the optimal insertion-depth range is determined to be 70–90 mm.

Orthogonal experimental design and result analysis

Experimental design

Based on the single-factor experiments, extraction acceleration (A), needle spacing (B), and insertion depth (C) were selected as the independent variables for the response-surface design, with plug seedling integrity ratio (Y) as the response. A three-factor, three-level response-surface experiment was carried out to investigate the individual and interactive effects of these factors on plug seedling integrity. The coded levels of the experimental factors are given in Table 2.

Regression analysis of the model

Based on the experimental data, the regression model relating the plug seedling integrity ratio Y to the seedling extraction acceleration A, needle spacing B, and insertion depth C was established as:

The normal probability plot of the residuals and the comparison of actual versus predicted values for this polynomial model are shown in Fig. 11a,b respectively. The data points exhibit a linear trend, and the residual normal probability plot closely follows the expected normal distribution.The actual-versus-predicted plot indicates that most data points lie close to the diagonal line, indicating a high degree of similarity between the observed and predicted values; the baseline fit across the 17 experimental runs is therefore satisfactory.The established model effectively captures the mathematical relationship between the seedling extraction acceleration A, needle spacing B, insertion depth C, and the response variable—plug seedling integrity ratio Y. Consequently, this regression model can be reliably employed to predict and analyze the operating process of the picking claw.

An analysis of variance was performed on the fitted model for plug seedling integrity ratio; the analysis of variance results for the multiple regression model and the significance levels of each experimental factor are presented in Table 4. The results indicate that the model is highly significant (P < 0.0001), with a coefficient of determination R2 = 0.9442, an adjusted R2 = 0.9146, and a predicted R2 = 0.9239, all approaching unity. These values confirm the outstanding significance of the fitted equation and demonstrate its excellent regression performance. Linear term A, interaction BC, and quadratic terms A2, B2, and C2 exert extremely significant effects on plug seedling integrity (P < 0.01), The analysis of variance further indicates that the influence of the factors decreases in the order seedling extraction acceleration > needle spacing > insertion depth.

In conjunction with the analysis of variance, the individual effects of the experimental factors on plug seedling integrity were examined through the regression equation. Response surfaces illustrating the interactions among these factors, as derived from the fitted model, are presented in Fig. 12. The contour plots of the response surface reveal the extent to which interacting factors influence the response variable: circular contours indicate a non-significant interaction between two factors, whereas elliptical contours signify a significant interaction.

Significant interactions exist between needle spacing (B) and insertion depth (C). The interaction term BC exerts a significant effect on the response variable—plug seedling integrity (P < 0.05). The interactions AC and AB, however, are not statistically significant (P > 0.05) and thus have a relatively minor influence on the response. Based on the above data and graphical analyses, among the two-factor interactions, BC has the most significant influence on plug seedling integrity, while AB and AC have less influence, with their effects not being statistically significant.

Parameter optimization

To secure a high plug seedling integrity ratio, the optimal combination of factors was sought within the specified constraints, providing a parametric basis for subsequent field trials. Taking seedling extraction acceleration, needle spacing, and insertion depth as the optimization variables, the following mathematical optimization model was established:

The optimal parameter combination was determined to be: seedling extraction acceleration A = 0.263 m/s2, needle spacing B = 37.028 mm, and insertion depth C = 84.660 mm. Under these conditions, the model predicts a plug seedling integrity ratio of 97.518%. Considering experimental constraints, operability, and practical feasibility, the parameters were set to seedling extraction acceleration A = 0.26 m/s2, needle spacing B = 37 mm, and insertion depth C = 85 mm.

Field validation

To ensure the reliability and accuracy of the experimental results, a comprehensive error control strategy was systematically implemented. Potential sources of deviation were minimized through the pre-test calibration of all sensors and actuators, Additionally, PLC-based compensation for mechanical lag in pneumatic cylinders. Material and environmental inconsistencies were mitigated by utilizing standardized seedling trays, uniform substrate, carefully controlled seedling age, with field trials conducted under stable soil moisture and weather conditions. Furthermore, operational variability was entirely eliminated via a PLC-controlled automation system that ensured highly reproducible motion sequences throughout all experiments, thereby removing any human-induced errors.The optimized parameters—seedling extraction acceleration 0.26 m/s2, claw spacing 37 mm, and insertion depth 85 mm—were adopted as the operating settings for the picking claws. A field validation trial was subsequently conducted under these conditions. Twelve replicate runs were carried out, and the resulting data were subjected to statistical analysis; the field trial is illustrated in Fig. 13.

The validation results are given in Table 5. Statistical analysis shows a mean plug seedling integrity of 92.23% from the field trials, compared with the simulated prediction of 97.52%, yielding a relative error of 4.29%.With a relative error of less than 5% between field and simulation results, the simulation is deemed reliable and can serve as a reference for designing the seedling picking claw and setting its operating parameters.

Conclusions

To improve the seedling picking performance of the strawberry transplanter, an automatic seedling pick-up device for strawberry was developed. Operating in a continuous mode that integrates whole-row grasping, equidistant separation, and precise placement, the architecture and operating principle of the automatic seedling pick-up device were presented, followed by the development of a dynamic model for the picking claw and a comprehensive kinematic analysis.

The seedling-gripping process of the picking claw was simulated using coupled EDEM–RecurDyn; plug seedling integrity ratio served as the response variable, and single-factor experiments were conducted on seedling extraction acceleration, needle spacing, and insertion depth. The influence of each experimental factor on plug seedling integrity was systematically analyzed to delineate the optimal ranges for their respective levels. A three-factor, three-level Box-Behnken design was employed to investigate the individual and interactive effects of the factors on plug seedling integrity. Response-surface analysis revealed that the factors influencing plug seedling integrity decreased in significance in the order seedling-picking acceleration > needle spacing > insertion depth. The optimal settings were determined to be 0.26 m/s2 for acceleration, 37 mm for needle spacing, and 85 mm for insertion depth.

Field validation confirmed that the mean plug seedling integrity obtained from the trials differed by only 4.29% from the simulated prediction, demonstrating the reliability of the optimized parameters; adopting the simulation-derived settings thus effectively enhances plug seedling integrity.

Data availability

The data will be provided according to the journal’s requirements. If the journal requires data files, please contact the corresponding author Subo Tian, E-mail: tiansubo@syau.edu.cn.

References

Tao, Z., Li, K., Rao, Y., Li, W. & Zhu, J. Strawberry maturity recognition based on improved YOLOv5. Agronomy. 14, 460. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy14030460 (2024).

Ciriello, M., Pannico, A., Rouphael, Y. & Basile, B. Enhancing yield, physiological, and quality traits of strawberry cultivated under organic management by applying different non-microbial biostimulants. Plants. 14, 712. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14050712 (2025).

Hernández-Martínez, N. R., Blanchard, C., Wells, D. & Salazar-Gutiérrez, M. R. Current state and future perspectives of commercial strawberry production: A review. Sci. Hortic. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2023.111893 (2023).

Wang, X. et al. Predicting minimum temperatures of plastic greenhouse during strawberry growing in Changfeng, china: A comparison of machine learning algorithms and multiple linear regression. Agronomy. 15, 709. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15030709 (2025).

Ahn, M. G. et al. Characteristics and trends of strawberry cultivars throughout the cultivation season in a greenhouse. Horticulturae. 7, 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae7020030 (2021).

Fan, L., Yu, J., Zhang, P. & Xie, M. Prediction of strawberry quality during maturity based on hyperspectral technology. Agronomy. 14, 1450. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy14071450 (2024).

Gutiérrez, C., Serwatowski, R., Gracia, C., Cabrera, J. & Saldaña, N. Design, building and testing of a transplanting mechanism for strawberry plants of bare root on mulched soil. Span. J. Agric. Res. 7, 791–799. https://doi.org/10.5424/sjar/2009074-1093 (2009).

Ji, D. et al. Design and experimental study of a traction double-row automatic transplanter for solanum lycopersicum seedlings. Horticulturae. 10, 692. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae10070692 (2024).

Ji, D. et al. Design and experimental verification of an automatic transplant device for a self-propelled flower transplanter. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 45, 420. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40430-023-04256-0 (2023).

Khadatkar, A., Pandirwar, A. P. & Paradkar, V. Design, development and application of a compact robotic transplanter with automatic seedling picking mechanism for plug-type seedlings. Sci. Rep. 13, 1883. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-28760-4 (2023).

Jin, X. et al. Development of single row automatic transplanting device for potted vegetable seedlings. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 11, 67–75. https://doi.org/10.25165/j.ijabe.20181103.3969 (2018).

Ma, G. et al. Appl. Eng. Agric. 36, 751–766. https://doi.org/10.13031/aea.13622 (2020).

Zhang, B. et al. Design and testing of a closed Multi-Channel Air-Blowing seedling Pick-Up device for an automatic vegetable transplanter. Agriculture. 14, 1688. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture14101688 (2024).

Han, L. et al. Design and test of an efficient seedling pick-up device with a combination of air jet ejection and mechanical action. J. Agric. Eng. https://doi.org/10.4081/jae.2024.1575 (2024).

Yang, Y. Exploring the optimal design and experiment of the strawberry bowl seedling transplanting mechanism. Master Thesis, Chinese Northeast Agricultural University, Harbin, China (2021).

Xu, C., Lu, Z., Xin, L. & Zhao, Y. Optimization design and experiment of full-automatic strawberry potted seedling transplanting mechanism. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 50, 97–106 (2019).

Liu, J. et al. Design and test of end-effector for automatic transplanting of strawberry plug seedlings. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 47, 49–58 (2016).

Miao, X. et al. Analysis of influencing factors on force of picking plug seedlings and pressure resistance of plug seedlings. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 44, 27–32 (2013).

Liu, J. et al. Appl. Eng. Agric. 35, 1067–1078. https://doi.org/10.13031/aea.13236 (2019).

Li, P., Yun, Z., Gao, K., Si, L. & Du, X. Design and test of a force feedback seedling Pick-Up gripper for an automatic transplanter. Agriculture. 12, 1889. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12111889 (2022).

Liu, Z. et al. Design and testing of a seedling pick-up device for a facility tomato automatic transplanting machine. Sensors. 24, 6700. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24206700 (2024).

Li, F., Lei, J., Wang, W. & Song, B. Optimal design and experimental verification of a four-claw seedling pick-up mechanism using the hybrid PSO-SA algorithm. Span. J. Agric. Res. https://doi.org/10.5424/sjar/2022203-18065 (2022).

Han, L., Mao, H., Hu, J. & Tian, K. Development of a doorframe-typed swinging seedling pick-up device for automatic field transplantation. Span. J. Agric. Res. https://doi.org/10.5424/sjar/2015132-6992 (2015).

Liu, Z., Zheng, W., Lv, Z. & Pan, J. Optimization and experimental analysis of multi-path sweet potato transplanter device. Sci. Rep. 15, 11164. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90732-7 (2025).

Bai, H., Zeng, F., Su, Q., Cui, J. & Li, X. Study on the interaction characteristics between pot seedling and planter based on hanging cup transplanter. Sci. Rep. 15, 10031. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94962-7 (2025).

Zeng, F., Cui, J., Li, X. & Bai, H. Establishment of the interaction simulation model between plug seedlings and soil. Agronomy. 14, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy14010004 (2024).

Liu, W., Wang, Q. & Jiang, H. Design and optimisation of end effector for loose substrate grasping based on discrete element method. Biosyst. Eng. 241, 43–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2024.03.009 (2024).

Quan, W., Wu, M., Luo, H., Chen, C. & Xie, W. Soil hole opening methods and parameters optimization of pot seedling transplanting machine for rapeseed. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 36, 13–21 (2020).

Hu, J., Pan, J., Chen, F., Yao, M. & Li, J. Simulation optimization and experiment of finger-clamping seedling picking claw based on EDEM-RecurDyn. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 53, 75–85 (2022).

Zhang, X. et al. Design and experiment of end effector of seedling taking by jacking and clampling of vegetable transplanter. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 54, 115–124 (2023).

Tian, Z. et al. Design and experiment of gripper for greenhouse plug seedling transplanting based on EDM. Agronomy. 12, 1487. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy12071487 (2022).

Li, N. & Liu, J. Design of control system for elevated strawberry transplanter. J. Agric. Mech. Res. 41, 122–126 (2019).

Funding

This research was supported by Liaoning Provincial Department of Agriculture and Rural Affairs—“Xingliao Talent Program” Agricultural Expert Project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.K.: Writing—original draft, software, validation. D.J.: Supervision, investigation. S.T.: Funding acquisition, supervision. S.L.: Writing—review and editing. T.S.: Data curation. G.D.: Investigation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kang, J., Ji, D., Tian, S. et al. Design and experiment of an automatic seedling pick-up device for strawberry transplanter. Sci Rep 15, 40647 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24509-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24509-3