Abstract

Reverse osmosis (RO) technology, as a mainstream method of water treatment, is widely used worldwide for water resource acquisition. However, in the context of the current global effort to achieve carbon neutrality, its carbon footprint has gradually attracted attention. The aim of this study is to systematically assess the carbon footprint of the RO water treatment process during its full life cycle and to explore the carbon reduction potential of the RO water treatment process under different decarbonization scenarios. To analyze RO’s carbon footprint in different applications, this study constructed a life cycle model of the RO water treatment process under the business model, calculating footprints for seawater reverse osmosis (SWRO), brackish water reverse osmosis (BWRO), and reclaimed water reuse. Results showed carbon footprints of 3.258, 2.868, and 3.083 kg CO₂-eq/m³ for the three applications, with operational power as the main carbon source, followed by chemical use, membrane production, and disposal. The carbon footprint of the three applications can be reduced by up to 93.23%, 87.81%, and 51.12% by predicting the grid structure, waste recycling and disposal methods, and energy consumption after process operation optimization. Sensitivity analyses of key process variables showed that the carbon footprint was more sensitive to influent temperature, system energy recovery, and influent salinity than membrane product life. Thus, the study recommends a comprehensive strategy involving renewable energy, energy efficiency improvements, and operational optimization to lower RO’s carbon footprint and support carbon neutrality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Water resources, energy, and climate change are three main challenges facing the world today1. As the global population grows and industrialization accelerates, freshwater resources become increasingly scarce. In 2015, the United Nations released the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 2030 in which 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were formulated, of which ensuring clean water sources and sanitation (SDGs 6) and actively addressing climate change (SDGs 13) have become the core issues of global development2. Water scarcity is being exacerbated by increased climate change. Rising global temperatures, sea level rise, and the frequency of extreme weather events are threatening the sustainable supply of freshwater resources3. Currently, according to the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and the World Health Organization (WHO), more than two billion people worldwide are facing water stress, and it is difficult to meet their daily needs reliably4. In this context, the innovation and application of water treatment technology have become one of the key initiatives to cope with the water crisis5.

Reverse osmosis (RO) water treatment technology utilizes the principle of reverse osmosis to effectively remove dissolved salts and pollutants in water through the membrane separation process6. As an efficient water treatment technology, it has been widely used in the fields of reverse osmosis desalination(SWRO), brackish water reverse osmosis(BWRO), and reclaimed water reuse, which has greatly alleviated the pressure of water scarcity7. SWRO technology has shown great potential in water-scarce coastal and arid areas, helping hundreds of millions of people to obtain a stable supply of fresh water8. BWRO technology has been widely used in inland areas and some coastal areas to provide fresh water suitable for drinking and agricultural irrigation by treating water sources with low salinity9. The application of reclaimed water reuse technology in municipal wastewater treatment offers new possibilities for the sustainable management of water resources by recycling wastewater to meet industrial, agricultural, and municipal water needs10. However, despite the remarkable success of RO technology in freshwater supply, the high energy consumption in its operation is still one of the main obstacles to its further diffusion, especially in the SWRO process11. This high energy consumption directly leads to the emission of large amounts of greenhouse gases (GHG), which will exacerbate global climate change, leading to an increase in global temperatures and causing various natural disasters such as heavy rainfall and rising sea levels12, and has become an environmental challenge for the promotion of the application of RO technology on a global scale13. On the other hand, the emission of GHGs and the intensification of climate change will also lead to the increasingly serious problem of water insecurity14. To respond to the challenge of global climate change, the United Nations Climate Change Conference adopted the Paris Agreement, which specifies the goal of “limiting global average warming to no more than 2 °C above pre-industrial levels and making every effort to limit it to no more than 1.5°C”15. Countries around the world have been enacting measures and actively taking actions to reduce carbon emissions to mitigate climate change16. As of September 2023, more than 150 countries and regions around the world have proposed carbon neutrality goals, with most of them are expected to achieve carbon neutrality by 205017. China proposed the goal of achieving peak CO2 emissions before 2030 and carbon neutrality before 2060 at the United Nations General Assembly in September 202018. Therefore, developing low-carbon water treatment processes of RO is crucial for achieving collaborative freshwater supply and mitigating climate change.

RO technology has demonstrated high efficiency and flexibility19, whether it is extracting fresh water from high-salinity seawater or treating brackish water and sewage20. With the continuous development of RO membrane materials and energy recovery device technology, the energy consumption of the RO process has been significantly improved. Nevertheless, RO process due to the construction of the system, the production of membranes, the operation of the energy consumption, maintenance, and membrane replacement, and other aspects of the greenhouse gas emissions cannot be ignored21. However, existing research focuses more on how to improve the service life of membranes, reduce membrane pollution, and improve the efficiency of energy recovery and other technical issues22,23,24,25,26, the systematic study of the carbon footprint of the whole life cycle of the RO process under different water quality conditions for different applications is still relatively limited. With the carbon neutrality targets proposed by many countries and regions around the world, the future energy decarbonization process is bound to have a far-reaching impact on the carbon footprint of the RO process. Therefore, a systematic assessment of the carbon footprint of the RO membrane water treatment process throughout its life cycle, especially the potential for carbon reduction under different future scenarios for different applications, is an important direction to push the water treatment technology toward sustainable development.

According to the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), life cycle assessment (LCA) is a method for aggregating and assessing the potential environmental impacts of all the inputs and outputs of a product or service system over the entire period of its life cycle27. The life cycle is defined as the process that begins with the extraction of resources for the production of a variety of raw materials, continues through the production of a variety of intermediate raw materials and energy sources, the production of the product, its transportation, its distribution, and its use, and ends with its disposal or regeneration28. Using the LCA method to account for the full life cycle environmental impacts of a product can effectively avoid the transfer of environmental problems between different life cycle stages and different types of environmental impacts. Based on the LCA, it is also possible to identify the main sources of impacts during the product’s life cycle, and then propose corresponding strategies to reduce environmental impacts29. Calculating the carbon footprint using LCA methods refers to assessing the environmental impact of the product’s full life cycle process in terms of climate change, quantifying the GHG emissions of the product from cradle to grave, and providing data support for the green and low-carbonization of the product’s production process30.

However, existing studies on RO systems have made strides in LCA, including cradle-to-grave analyses. For instance, the energy and environmental performance of SWRO was assessed by Raluy et al. (2006); brackish and seawater systems in California were evaluated by Stokes and Horvath (2006); and end-of-life options for RO membranes were compared by Lawler et al. (2015). More recent studies, such as the one that adopted detailed inventory modeling of RO wastewater reuse, were conducted by Zhou et al. (2022).Nonetheless, significant gaps remain. Most existing LCA studies are static, lack scenario modeling for future decarbonization, and provide insufficient granularity in membrane production and end-of-life treatment modeling. Moreover, comparative analysis across multiple applications (SWRO, BWRO, reclaimed water reuse) under evolving energy and waste disposal systems is rare. Therefore, this study aims to develop a comprehensive cradle-to-grave LCA model incorporating production, use, and disposal phases of RO systems under evolving energy contexts in China, with application-specific modeling and scenario-based sensitivity analysis.

In this study, we used the LCA method to quantify the full life cycle carbon footprints of three typical ROapplications - SWRO, BWRO, and reclaimed water reuse - covering all stages from membrane production to operation and maintenance to final disposal of the membranes. Meanwhile, we analyzed the impact of different operational variables (e.g., membrane lifetime, influent water quality, energy recovery rate, etc.) on carbon emissions, to identify the key factors affecting the carbon footprint. Lastly, through scenario analysis, we also explored the trends and reduction potentials of the carbon footprints of the three water treatment applications in the context of future decarbonization of the power grid, the use of waste recycling and disposal methods, and the optimization of process operations. Our study would provide a scientific basis and suggestions for the decarbonization design of water treatment processes, and achieving carbon neutrality.

Materials and methods

Based on ISO 14,040 and 14,044 standards31,32, the LCA study mainly includes four steps: Goal and Scope Definition, Life Cycle Inventory (LCI), Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCI), and Interpretation. The simplified flowchart of each step of carbon footprint calculation using the LCA method is shown in Fig. 1.

Goal and scope definition

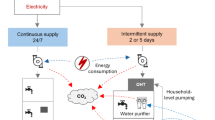

The objective of this study is to quantitatively assess the full life cycle carbon footprint of three typical RO water treatment applications: SWRO, BWRO and reverse osmosis reclaimed water reuse. To make the carbon footprint calculations comparable, the functional unit of this study is defined as the production of 1 m³ of desalinated water that meets the Chinese Class III surface water environmental quality standards (GB 3838 − 2002). This level of water quality is applicable for general industrial use and secondary contact recreational water, and is adopted as a representative midpoint standard for RO-based water treatment applications. The scope of the study was primarily focused on the core aspects within the full life cycle of the RO process. However, due to the challenges in data collection and the complexity of calculation, while maintaining the concept of the full life cycle as the overarching framework, we have specified the particular elements that are not considered in the detailed carbon footprint calculations for the sake of practicality and feasibility — namely, the carbon footprint contributions arising from product transportation, sales, waste management, and asset-based products, which are not included in this specific analysis. Therefore, the RO process system boundary was divided into three main stages according to its life cycle: membrane product production, operation and maintenance, and membrane product disposal.

Membrane products mainly include two parts: membrane sheet and membrane module33, and the source of carbon footprint in the production stage includes raw materials and power consumption. The RO process flow generally includes water intake, pre-treatment, RO water treatment and post-treatment34, and at the same time, to reduce the impact of membrane contamination on the rate of desalination, the RO membrane is maintained by pharmaceutical cleaning. The water intake process mainly involves pumping the feedwater through pump to the the feedwater pool. After taking the water will be pre-treatment, mainly including coagulation, clarification, and filtration or through ultrafiltration membrane35. SWRO process mainly through the high-pressure pump pressurized pre-treatment water, so that it through the RO membrane, at the same time, in order to recover the energy of the RO membrane effluent water, generally equipped with energy recovery devices. To ensure that the effluent water quality and concentrated brine meet the discharge standards, the two types of effluent after desalination are considered to be post-treatment with the addition of pharmaceuticals. The waste treatment stage is mainly for the treatment of membrane products, according to the relevant literature, the current domestic solid waste is mainly treated by incineration or landfill36, so this study considers that the carbon footprint of the waste stage is the carbon footprint generated by the incineration and landfill disposal of the membrane sheet and membrane module37. Based on the above-defined system boundary and process-related unit process analysis, the quantitative boundary of the RO process life cycle carbon footprint is shown in Fig. 2.

Life cycle Inventory(LCI)

The life cycle inventory (LCI) phase aims to establish a quantitative foundation for evaluating the environmental performance of the RO water treatment process. By analyzing the RO process flow and the full life cycle model of the RO process, the inputs to the RO process include the influent base stream and product streams such as electricity, membrane products, chemicals, and filtration media, and the output product streams are mainly desalinated water, concentrated brine, and waste membranes.

The water parameters mainly include the water quality and quantity parameters of feed water, desalinated water, and concentrated brine, and the operation parameters mainly include the operation time, design capacity, and other parameters. Carbon footprint-related data acquisition was carried out according to the results of the inventory analysis, and the consumption of each inventory substance was collected through literature or field research.

Life cycle impact assessment (LCIA)

The life cycle impact assessment (LCIA) phase involves converting the material and energy flows gathered in the LCI into impact results, using carbon emission factors. Carbon footprint factor data were quoted from the Ecoinvent database, the carbon footprint factor data for O&M phase consumables are presented in Table A3 in Appendix A. For the lack of carbon footprint factor data of membrane products and some chemicals in the database, the carbon footprint of membrane upstream production was deduced by collecting the inventory data of membrane module and chemical production and the carbon footprint data of the upstream production of the listed substances through further retrospective research, and the carbon footprint of the waste disposal of membrane products was derived through similar substitution. In this study, the IPCC 2021 GWP 100a method was adopted to quantify greenhouse gas emissions. The GWP values used are CO₂ = 1, CH₄ = 27.2, N₂O = 273. The list of substances in the life cycle of the RO process and its analysis are shown in Table 1. Data on the carbon footprint factors of processes and substances associated with the membrane production stage are presented in Table A1 and A2, and data on the carbon footprint factors of processes and substances associated with the membrane disposal stage are presented in Table A4.

The carbon emission factors were obtained from the ecoinvent database (version 3.8, cut-off system model), ensuring consistency and regional applicability for China.

Firstly, the carbon footprint of each life cycle stage was calculated, and the full life cycle carbon footprint was calculated by accumulation.

The replacement cycle of RO membrane is generally 3 ~ 5 years, assuming that the replacement cycle of RO membrane T = 4 years, the RO membrane product production stage of materials and energy converted to daily consumption can be calculated by the Eq. (1), Eq. (2):

where, mi (kg/day) is the converted daily consumption of various raw materials required for the production of membrane products, mi’ (kg/unit) is the consumption of different raw materials needed for the production of each membrane products, i is the type of raw materials used for the production of membranes, Z is the number of membrane products used in desalination plants, we1 (kwh/day) is the converted daily electricity consumption for the production of membrane products, and w’e1 (kwh/unit) is the electricity consumption for the production of each membrane products.

The carbon footprint of the production stage of membrane module can be calculated using Eq. (3):

where, CFp (kg CO2-eq/m³) is the carbon footprint generated by membrane production, ki is (kg CO2-eq/kg) is the carbon footprint factor of different raw materials for membrane production, ke1 (kg CO2-eq/Kwh) is the electricity carbon footprint of the membrane plant, and Q (m³) is the daily freshwater production.

The carbon footprint of the operation and maintenance phase can be calculated according to Eq. (4):

where CFO (kg CO2-eq/m³) is the carbon footprint generated in the operation and maintenance stage, wo (Kwh) is the power consumption of the desalination plant, ke (kg CO2-eq/Kwh) is the power carbon footprint factor in the location of the desalination plant, CF1 (kg CO2-eq/m³) is the carbon footprint in the pretreatment stage. CF2 (kg CO2-eq/m³) is the membrane cleaning carbon footprint.

The carbon footprint of the waste treatment stage is calculated as shown in Eq. (5):

where CFw (kg CO2-eq/m³) is the carbon footprint generated by waste disposal, mn (kg) is the amount of waste generated, kn (kg CO2-eq/kg) is the carbon footprint factor of various wastes, and n is the type of waste.

Therefore, the carbon footprint of 1 m³ fresh water produced by desalination plants can be calculated from Eq. (6):

Definition of different RO process applications

To investigate the carbon footprint of different RO water treatment applications, three typical applications were defined in this study: SWRO, BWRO, and reclaimed water reuse. Each application represents the main application direction of RO technology under different water quality conditions and operating environments. The carbon footprint accounting for these three applications is based on the same model structure and adjusted for their respective characteristics to ensure the accuracy and scientificity of the calculations.

To better compare the three RO process applications (SWRO, BWRO, and Reclaimed-Water Reuse), we include Table 2 below(The representative values listed in the table do not imply a single fixed configuration for each application but serve as baseline anchors for our scenario and sensitivity analysis. The precise modifications applied in each scenario or sensitivity run are documented in Appendix B), which summarises the representative operating parameters and key constraints (feed salinity, pressure, specific energy consumption, recovery, pretreatment).

SWRO is the basic application for constructing the LCA model of the RO water treatment process, and SWRO mainly treats seawater with high salinity (about 35 g/L). The process accounted for in this study is a single-membrane SWRO process, the flow of the SWRO process is as shown in the Fig.A2(a) in Appendix A, in which firstly, the feedwater enters the feedwater pool, which is subsequently pumped by the feedwater pump to the coagulation and sedimentation tank, where coagulants, flocculants, and other pre-treatment chemicals are added for sedimentation treatment. After the precipitation, the water flows to the multi-media filter, and horizontal filter for further filtration, and is then pressurized by a high-pressure pump. The pressurized water enters the RO membrane group for RO treatment, thus obtaining desalinated water and generating concentrated brine simultaneously. This process is equipped with an energy recovery device for energy recovery and the RO membrane needs to use membrane cleaning chemicals to clean.

BWRO process is suitable for treating low salinity water, such as low salt concentration seawater or brackish groundwater. The operating pressure of the process is lower than that of the SWRO process. The flow of the BWRO process is as shown in the Fig.A2(b) in Appendix A, after the feedwater flows into the feedwater pool, it is pumped by the feedwater pump to the multi-media filter, activated carbon filter, and security filter several times filtration, and at the same time, it is added with a variety of pre-treatment agents such as biocide, coagulant, scale inhibitor, reductant and so on. The filtered water is pressurized by a high-pressure pump and then enters the RO membrane group for RO treatment to obtain desalinated water while producing a by-product of concentrated brine. This process also has an energy recovery unit for energy recovery and requires the use of membrane-cleaning chemicals to clean the RO membrane. Therefore, the carbon footprint calculation for the BWRO process refers to the SWRO calculation process, but with modified parameters such as energy consumption, operating pressure, and influent salinity based on SWRO’s LCA model.

The reclaimed water reuse process is mainly applied to municipal or industrial wastewater treatment and is suitable for wastewater sources with high pollutant content, low salinity, and low operating pressure. The process flow is shown in the Fig.A2(c) in Appendix A. After the feedwater enters the feedpool, it is pumped by the feedwater pump to the self-cleaning filter for preliminary filtration, and pre-treatment chemicals are added at the same time. Then, the water flows to the UF membrane group for ultrafiltration treatment, and the ultrafiltration water enters the security filter and is then pressurized by the high-pressure pump. The pressurized water enters the RO membrane group for RO treatment, which results in desalinated water and concentrated brine. In this process, membrane-cleaning chemicals are required to clean the UF and RO membranes. Its carbon footprint calculation was based on the carbon footprint calculation process and model of the SWRO process but adjusted in terms of influent water composition, pre-treatment requirements, and operating parameters.

Scenario analysis

To comprehensively assess the future carbon footprint trends and emission reduction potentials of RO membrane-based water treatment systems, this study constructs four scenario models based on plausible pathways of power sector decarbonization, membrane recycling development, and operational optimization. These scenarios are intended to capture the combined or isolated effects of upstream electricity decarbonization and downstream waste management improvements on the life cycle carbon emissions of RO systems. The carbon footprint results calculated in Sect. 2.2 and 2.3 serve as the baseline scenario in this study, representing the current technological and power structure conditions, which provide the reference point against which the decarbonization and optimization effects of future scenarios are evaluated. By applying these scenarios to three representative applications—SWRO, BWRO, and reclaimed water reuse—this study aims to provide a multi-dimensional evaluation of system-level responses to external environmental and technological changes.

The scenario design builds upon a consistent baseline condition reflecting the current status of China’s power grid and RO system configurations. On this basis, four future-oriented scenarios are developed: Scenario I models the decarbonization pathway of China’s power system driven by increased renewable energy penetration; Scenario II incorporates carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) deployment into thermal power generation, representing an enhanced electricity decarbonization trajectory; Scenario III focuses on the development of resource recovery technologies for spent RO membranes and the implementation of circular economy practices; and Scenario IV further assumes that operational optimization of RO systems can reduce electricity demand without compromising performance.

Electricity consumption is the main source of the carbon footprint of the RO system, and carbon neutrality of the power system will promote the gradual carbon reduction and decarbonization of the RO system. Currently, China has adopted many green policies to reduce the carbon emissions of the country and the power sector38, among which energy transition and the application of CCUS technology are important means to achieve the gradual carbon reduction and decarbonization of the power grid39. In this study, we refer to the relevant literature on the study of the optimal development path for the share of renewable energy in the power generation structure40, collate and predict the power structure aiming at carbon neutrality in 2030–2060, and calculate the change of China’s electric power carbon footprint through the weighted average derivation, and then assess the change of the carbon footprint of the RO process under this scenario (Scenario I). In addition, thermal power generation can further reduce its carbon footprint through CCUS technology, and the carbon footprint of electricity and the change in the carbon footprint of the RO process was projected based on the forecasts of the proportion of CCUS technology applied to thermal power generation from 2030 to 2060 following relevant studies (Scenario II). The carbon footprints of power generation from different energy sources and thermal power combined with CCUS technology are shown in Table A5, the energy structure of the power system and the projected share of thermal power combined with CCUS are shown in Tables A6 and A8, and the final projected changes in the carbon footprint of electricity are shown in Table A7 (ScenarioⅠ) and Table A9 (Scenario Ⅱ).

Scenario III considers a resource recovery scenario for spent membrane modules. It is assumed that RO membrane modules are processed using closed-loop recycling41. When the degradation of the desalination rate and water production rate of the waste membrane is within a certain range42, two disposal methods are considered: reuse after cleaning and chemical oxidation repair for use as porous membranes43. When the membrane products cannot meet the conditions of reuse and direct recycling, the membrane products are considered to be disassembled and disposed of44, in which the waste membrane sheet part of the direct incineration means, the recyclable plastic part of the membrane shell part of the closed-loop recycling by mechanical recycling45, and the other cannot be recycled part of the membrane shell landfill and incineration disposal46, the relevant treatment dispositions are listed in Table A10. According to the literature research, with the improvement and upgrading of process technology and membrane products, the renewable recycling rate of waste membrane products from 2030 to 2060 is predicted to be 40%, 50%, 60%, and 70%, respectively, and at the same time, the study assumes that 50% of the recyclable waste membrane products are reusable waste membranes47. For the disassembled film shell portion, the study considers the recycling rate of plastic waste in China as an analogy to the recycling of film shells48. Under China’s carbon neutrality target, China’s plastic recycling rate is predicted to be 30%, 40%, 50%, and 60% respectively from 2030 to 206049. The relevant carbon footprint data were obtained from the Ecoinvent database and related literature, and the reference data are shown in Table A11 in Appendix A. Based on the above research and prediction data and database data, the carbon footprint generated from waste treatment was calculated according to the EU Product Environmental Footprint (PEF50%−50%) method allocation.

Based on Scenario III, Scenario IV assumes that the RO process can be operationally optimized to reduce power consumption in operation. In industrial RO systems, excessive operating pressure is often used to ensure treatment quality, and operational optimization enables a reduction in energy consumption without compromising treatment efficiency. This study assumes a 30% reduction in operational power consumption through operational optimization in the future to assess the potential emission reduction contribution of operational optimization to the carbon footprint of the RO process.

Sensitivity analysis

Building upon the carbon footprint results of the baseline scenario, this section conducts a sensitivity analysis to explore how variations in key parameters may affect the life cycle emissions of RO systems. The baseline scenario serves as the reference framework, reflecting the current grid structure, membrane technology, and operational practices, against which the influence of changes in individual factors is evaluated. In this study, a sensitivity analysis was conducted for the SWRO process. Since key process variables such as influent water temperature, energy recovery rate, membrane life cycle, and influent salt concentration have a significant impact on the carbon footprint of the RO process and there is a large degree of uncertainty in the actual operation of these parameters, this study adopts a sensitivity analysis methodology to provide an in-depth analysis of these variables. Among them, key operating variables such as feed water temperature, energy recovery rate, membrane life cycle, and feed water salt concentration are significantly sensitive to the three processes of SWRO, BWRO, and reclaimed water reuse, this study analyze the sensitivity of the above variables, to provide scientific reference for optimizing similar RO processes and carbon reduction strategies.

Specifically, the influent water temperature affects the viscosity of water and the permeability of the membrane, which in turn has a direct impact on the energy consumption and carbon footprint of the system; the energy recovery rate determines the efficiency of energy recovery from high-pressure wastewater, and different recovery rates significantly affect the energy efficiency and carbon emission level of the system; the membrane life cycle directly affects the frequency of replacement of membranes and the consumption of materials, and since the membrane life is affected by a variety of factors in actual operation, the uncertainty will have a significant impact on the carbon footprint of the system. Uncertainty will have a long-term impact on the carbon footprint of the system; the salt concentration of the influent water affects the operating pressure and energy consumption of the system, and a higher salt concentration requires higher pressure to achieve desalination, thus increasing energy consumption and carbon emissions. Therefore, through sensitivity analysis, the most sensitive factors to the carbon footprint can be identified, which provides a scientific basis for process optimization and the formulation of emission reduction strategies.

In the course of the sensitivity analyses, this study first determined the baseline parameter values used in the carbon footprint calculations as reference points. Then, different adjustment ranges were set for each key variable: the influent temperature parameter varied between − 80% and + 80% from the baseline value, and the energy recovery rate, membrane life cycle, and influent salt concentration parameters fluctuated between − 60% and + 60%.

In addition, the above sensitivity analyses were applied to a carbon-neutral scenario in 2060 to predict the extent of the potential impact of different parameter changes on the carbon footprint of the process in a carbon-neutral context.

Results and discussion

Carbon footprint analysis of different applications

Based on the IPCC methodology, the whole life cycle carbon footprints of the three applications, SWRO, BWRO, and reclaimed water reuse, were quantitatively assessed. The data for the calculation are shown in the Appendix B. The results, as shown in Table 3, show that the main source of the carbon footprint of the three different RO applications is the operation and maintenance phase, and the high electricity consumption and electricity carbon footprint in this phase are important factors for the carbon footprint of the RO process.

The total life cycle carbon footprint of SWRO in the baseline scenario is 3.258 kg CO2-eq/m3 of desalinated water, of which the carbon footprints of the membrane product production stage, operation and maintenance stage, and RO unit end-of-life disposal stage are 0.007, 3.248, and 0.003 kg CO2-eq/m3 of desalinated water, respectively. The carbon footprint of the operation and maintenance stage accounts for 99.69% of the full life cycle carbon footprint, and the electricity consumption generated by the RO system to offset the osmotic pressure of the brine is the main source of the carbon footprint. It has been suggested that the introduction of a renewable energy-based electricity supply can effectively mitigate the high carbon footprint of the operation and maintenance phase50. According to the results, the membrane product production and disposal stage contributes relatively little to the carbon footprint per unit of product water. Still, some relevant researchers have pointed out that reducing the carbon footprint of the membrane product production and disposal stage by extending the membrane life and recycling waste membranes is of great significance in promoting the RO process to achieve a net emission51.

The carbon footprint of BWRO is 2.868 kg CO2-eq/m3 of product water, of which the carbon footprint of the operation and maintenance phase accounts for 99.65%. Brackish water has a lower salt concentration than natural seawater, requires less salt separation and removal, and requires a lower osmotic pressure to operate the desalination plant, so the energy consumption of BWRO is lower than that of SWRO. In addition, since the composition of seawater is more complex than that of brackish water, the type and dosage of chemicals used in the desalination process of brackish water are different. Despite the relatively low energy consumption of BWRO, future studies need to focus on how to further reduce carbon emissions, such as optimizing the lifetime of the membrane modules and improving the desalination efficiency of the membranes, in order to continuously reduce the carbon footprint of the BWRO process.

In the baseline scenario, the full life cycle carbon footprint of reclaimed water reuse is 3.083 kg CO2-eq/m3 product water, of which the O&M phase accounts for 99.58%. Unlike the above two applications, the operation and maintenance phase of water reuse consumes more chemicals, so its chemical carbon footprint is relatively high, accounting for about 45.64% of the carbon footprint in the operation and maintenance phase. This result highlights the significant impact of chemical use on the carbon footprint of reclaimed water reuse processes. In recent years, the optimization of chemicals in reclaimed water reuse processes has become one of the key research priorities to reduce the overall carbon footprint52. Through the introduction of new low-carbon chemicals or the use of intelligent chemical management systems, the amount of chemical dosage can be significantly reduced while safeguarding water quality, thus reducing carbon emissions during the operation and maintenance phase.

For the above three different RO water treatment applications, the main source of carbon footprint is the electricity consumption during operation, therefore, designing low-energy systems for the relevant applications is crucial for the progressive decarbonization of the desalination industry. In addition, despite the relatively small carbon footprint of the membrane production and disposal stages, further environmental benefits are expected to be realized at these stages by extending the lifetime of the membranes, increasing the membrane recycling rate, and reducing carbon emissions from raw materials used in the membrane manufacturing process. These measures can further advance the process of reducing the carbon footprint of the entire life cycle of the RO process and support the sustainable development of water treatment technologies (Table 3).

Carbon footprint analysis under different future scenarios

As the proportion of renewable energy in the power system gradually increases and the overall power structure tends to be decarbonized, the carbon footprints of the three RO applications show a significant downward trend in Scenario Ⅰ. Specifically, in the baseline scenario, the carbon footprints of all three RO applications are projected to decline rapidly by 2030 as the share of renewable energy rises and the power system is gradually decarbonized; the downward trend slows down relatively between 2030 and 2060 (Fig. 3). By 2060, the carbon footprints of the three RO applications, SWRO, BWRO, and reclaimed water reuse, show a downward trend of 84.69%, 79.77%, and 46.44% (Fig. 4), respectively, compared to the baseline scenario. In this scenario, although the total carbon footprint is reduced, the carbon footprint of the three applications is still mainly derived from electricity consumption during the operation phase. This suggests that while continuing to promote decarbonization of the power system, further optimization of the energy consumption structure of the RO applications is required to achieve a more comprehensive carbon reduction.

In Scenario II, the decarbonization of the power system is further increased and the carbon footprint of the three RO applications is further reduced. Compared to Scenario I, the carbon footprint of Scenario II is further reduced (Fig. 3). By 2060, the decreasing trend of the carbon footprints of the three applications is 93.23%, 87.81%, and 51.12%, respectively. At the same time, the share of energy consumption in the operation phase in the total carbon footprint of the three applications decreases significantly, from 98.93%, 93.17%, and 54.24% in the baseline scenario to 84.12%, 43.96% and 6.38% (Fig. 4), respectively. This significant reduction potential suggests that the carbon footprint reduction potential of the RO process is even more substantial, driven by the decarbonization of the power system. It also implies that the use of cleaner power and CCUS with thermal power technologies play a key role in further reducing carbon emissions.

The carbon footprint of Scenario III increases compared to Scenarios I and II. The carbon footprint reductions of the three RO applications are relatively small in this scenario, with the downward trend of the carbon footprints of SWRO, BWRO, and reclaimed water reuse only 0.23%, 0.27%, and 0.15% (Fig. 3). In addition, the share of energy consumption in the operation phase has increased, at 99.17%, 93.43%, and 54.32% (Fig. 4), respectively. Due to the low level of decarbonization of the power system in this scenario, the carbon footprint reduction effect of the RO process is limited. This suggests that if the power system fails to achieve a large-scale grid-connected transition to renewable energy and CCUS with thermal power, it will be difficult to significantly reduce the overall carbon emissions from the RO process, and energy consumption during the operation phase will remain the main source of carbon emissions. Therefore, in this scenario, further optimizing the energy efficiency of the RO process itself will be an important way to reduce the carbon footprint.

The reduction potential of Scenario IV lies between Scenarios I and III. Through operational optimization measures, the carbon footprints of SWRO, BWRO, and reclaimed water reuse are reduced by 29.92%, 28.22%, and 16.42% respectively in this scenario (Fig. 3). Although operational optimization can reduce carbon emissions to some extent, such reductions are relatively limited compared to Scenario II(Fig. 4). This suggests that operational optimization still contributes to emissions reductions in the context of a decarbonized power system, but it is difficult to compare with the carbon footprint reductions resulting from a full low-carbon power transition. Potential measures for operational optimization include improving the overall energy efficiency of the RO system, improving the performance of the membrane modules, reducing the energy consumption of the system, and optimizing the cleaning and maintenance applications to further enhance system efficiency and reduce the carbon footprint.

Taken together, the degree of decarbonization of the power system plays a crucial role in reducing the carbon footprint of the RO process. According to the scenario analysis, the carbon footprints of SWRO, BWRO, and reclaimed water reuse can be reduced by up to 93.23%, 87.81%, and 51.12%, respectively, with the support of a power system that achieves full decarbonization. In addition, in other scenarios, although measures such as operation optimization and membrane device recycling can also produce emission reductions, their potential is relatively limited, the detailed carbon footprint situation is shown in Fig.A3. Therefore, adopting green power or improving energy efficiency to reduce system energy consumption is a top priority to drive the RO process to achieve carbon reductions, and the carbon footprint of the RO process can be further reduced by recycling discarded membrane devices, optimizing operational variables, and other applications53.

Carbon footprint sensitivity analysis of process variables

The carbon footprint sensitivity analysis results of inlet water temperature are shown in Fig. 5(a). When the temperature rises by 60%, the carbon footprint of the baseline scenario and carbon neutral scenario in 2060 will decrease by 10.41% and 10.15%, respectively. When the temperature decreased by 60%, the carbon footprint of the two scenarios increased by 13.88% and 13.53%, respectively. This is because properly increasing the inlet water temperature can improve the separation efficiency, reduce the energy consumption of the RO system, and then affect the carbon footprint of the desalination process. According to the carbon footprint change data, the change in inlet water temperature can have a certain impact on the carbon footprint of the system, but this impact will not change significantly with the low carbonization of the RO system.

The carbon footprint sensitivity analysis results of the system energy recovery rate are shown in Fig. 5 (b). When the system energy recovery rate decreases, the system carbon footprint increases, and the change range of the carbon footprint in the baseline scenario is larger than that in the carbon-neutral scenario in 2060. When the change rate of energy recovery increases by 60%, the carbon footprint of the system decreases. The carbon footprint under the two scenarios was reduced by 12.83% and 9.93%, respectively. When the energy recovery rate is reduced by 60%, the changing trend of carbon footprint is more obvious, and the carbon footprint under the two scenarios increases by 40.89% and 37.85% respectively. This is because the energy recovery rate is negatively correlated with the system energy consumption and positively correlated with the salt content of the water produced. However, the impact of the system energy consumption on the carbon footprint is greater than that of the water produced on the carbon footprint, so the final result shows that the carbon footprint is negatively correlated with the energy recovery rate. According to the sensitivity analysis data, the reduction of energy recovery rate has a high sensitivity to the carbon footprint of the system, but its sensitivity does not change significantly with the decarbonization of the RO system.

The carbon footprint sensitivity analysis results of the membrane product life are shown in Fig. 5(c). Extending the membrane life cycle can reduce the carbon footprint of the desalination process. When the membrane service life is increased by 60%, the carbon footprint of the baseline scenario and the 2060 scenario can be reduced by 0.1% and 0.6%, respectively. According to the carbon footprint calculation formula in Sect. 2, the change in the membrane product replacement cycle has an impact on the water volume of the product during the membrane life cycle, which in turn has an impact on the carbon footprint generated by the membrane product. In the baseline scenario, due to the low contribution of the carbon footprint of membrane products to the carbon footprint of the desalination process, changes in the lifetime of membrane products under the baseline scenario have less impact on the carbon footprint of desalination than in the 2060 scenario.

The carbon footprint sensitivity analysis results of influent salt concentration are shown in Fig. 5 (d). When influent salt concentration increases by 60%, the carbon footprint of SWRO in the baseline scenario and the 2060 scenario increases by 40.99% and 39.8%, respectively. This is because an increase in influent salt concentration leads to an increase in the power consumption of the desalination system, which in turn leads to an increase in the carbon footprint. In addition, according to Fig. 5 (d), it can be seen that the change rates of carbon footprint under the baseline scenario and carbon neutral scenario are the same, and both will have a significant impact on the carbon footprint of the system.

There are many factors affecting the carbon footprint of the SWRO process. Through sensitivity analysis of various process variables, factors with high sensitivity can be found based on synthesizing various process variables, and the coupling design of optimal operating parameters can be carried out54. According to the carbon footprint sensitivity analysis of the above four process variables, compared with the change of membrane product life, the carbon footprint of SWRO is more sensitive to feed water temperature, system energy recovery rate, and feed water salt content. In the RO system, the energy material consumption and water production per unit of product water are determined by a variety of process variables. Therefore, the life cycle assessment model can be applied to the future desalination process design process, to maximize the optimization of the process and promote the process to achieve carbon emission reduction.

Future prospects

The data sources of this study are field research data and database data. RO water treatment will have different processes and operating parameters according to different influent water quality and desalination water requirements and other treatment conditions, so the use of a representative single research data will have a certain deviation from the data of different processes, such as pre-treatment process, the type of chemical dosage, dosage, etc. The carbon footprint data of each consumable substance in the calculation process are from the database, and their time, location, and technical representativeness are low compared with the data of direct measurement. In addition, according to the system boundary, some of the emissions with a lower percentage are not calculated, which will also have an impact on the accuracy of the data. Therefore, the accuracy and representativeness of the data can be improved through further more extensive and specific upstream research and field studies. The data of decarbonization scenarios can be predicted by more specific calculations to improve the accuracy of the data on the carbon footprint of electricity and the carbon footprint of the waste recycling process.

Based on the above calculations, the electricity consumption during the operation of three typical RO applications, SWRO, BWRO, and reclaimed water reuse, is the main source of their carbon footprint. When the electricity carbon footprint is reduced, the carbon footprint of RO applications can be reduced by up to 90% or more. Therefore, reducing electricity consumption through technological improvements as well as lowering the carbon footprint of electricity is an important means of achieving significant reductions in the carbon footprint of RO water treatment applications50. When the power sector is continuously decarbonized, the main source of carbon footprint is still electricity consumption, but the carbon footprint of membrane device production and waste disposal process has increased, therefore, based on continuous decarbonization of the power grid, accelerating the waste recycling of membrane products can further reduce the carbon footprint of the RO water treatment process.

In this study, the degree of influence of different process variables on the carbon footprint of the SWRO process was investigated through sensitivity analyses, and the process variable factors with the highest to the lowest sensitivity were influent salinity, energy recovery, influent temperature, and membrane product life, in descending order. The design of process technology solutions usually requires a combination of process parameters and operating conditions. A sensitivity analysis of a single process parameter and operating condition can be used to effectively assess its impact on the system and thus help to propose the best technical optimization.

Moreover, future research should also address several environmental issues that were not included in the current system boundary. Although this study evaluated the carbon footprint of membrane manufacturing, it did not explicitly account for solvent emissions from membrane fabrication or cleaning processes, due to the lack of specific emission factors and process-level LCI data. These emissions, while potentially small in terms of carbon equivalents, may contribute to local air pollution or occupational exposure risks. In reclaimed water reuse scenarios—particularly those involving industrial wastewater—the rejected brine may contain a variety of pollutants such as heavy metals, nitrates, fluorides, and persistent organic compounds, which could pose serious risks to freshwater and marine ecosystems if not properly treated. Furthermore, although incineration of end-of-life membranes was assessed for greenhouse gas emissions, the potential release of toxic substances (e.g., arsenic, chromium, lead) and environmental impacts of residual ash were not considered. To improve the environmental integrity of RO life cycle assessments, future research should incorporate additional impact categories—such as human toxicity, freshwater and marine ecotoxicity, and chemical persistence—into the LCA framework. This will enable a more complete understanding of the environmental trade-offs across all life cycle stages of RO systems, particularly under industrial application scenarios and large-scale membrane management.

Conclusions

In this study, life cycle modeling and carbon footprint accounting of RO water treatment applications were carried out, and the carbon footprints of three typical RO applications, SWRO, BWRO, and reclaimed water reuse, were calculated. Under the baseline scenario, the carbon footprints of SWRO, BWRO, and reclaimed water reuse were 3.258, 2.868, and 3.077 kgCO2-eq/m3 product water, respectively, with the carbon footprints generated by the operation stage accounting for 99.69%, 99.65%, and 99.77%, and those generated by the electricity consumption during the operation stage accounting for 98.93% and 93.17%, 54.24%. The decarbonization potential of the three RO processes is particularly significant in Scenario II, where the carbon footprint of SWRO, BWRO, and reclaimed water reuse can be reduced by up to 93.23%, 87.81%, and 51.12% as the proportion of renewable energy sources in the power system increases and CCUS technology becomes more widespread.

In addition to internal scenario comparisons, this study also includes an external comparison with previously published carbon footprint data. Appendix Table A12 presents a comparison between the carbon footprints of RO applications in this study and those reported in a representative previous study. The SWRO carbon footprint calculated in this study is 3.258 kg CO₂-eq/m³, which is close to the 3.25 kg CO₂-eq/m³ reported in the literature, indicating consistency across studies despite differences in modeling assumptions. No comparative values were available for BWRO and reclaimed water reuse in the referenced study. Compared with thermal desalination technologies, such as MSF (10.50 kg CO₂-eq/m³) and MED (6.00 kg CO₂-eq/m³), the RO-based processes in this study show a significantly lower carbon footprint, highlighting the environmental advantages of membrane-based desalination under current and future decarbonization scenarios.

To reduce carbon emissions, it is recommended to start from two aspects: on the one hand, in the current scenario, energy saving in the operation phase needs to be realized by improving energy efficiency and adopting energy-saving technologies, thus reducing the carbon footprint; On the other hand, the adoption of energy sources with a low-carbon structure, such as the active promotion of renewable electricity and the application of CCUS thermal power, should be actively promoted to improve the energy structure and contribute to a greater degree of decarbonization of the RO process. In addition, the synergistic optimization of multiple process variables and operating parameters is crucial for process design. Achieving a balance between different parameters, process energy consumption, plant production, and end-of-life disposal in a low-carbon design to minimize greenhouse gas emissions over the full life cycle of the process will be a key direction for the sustainable development of future desalination technologies.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information files. Should any raw data files be needed in another format they are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Adeel, Z. A renewed focus on water security within the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Sustain. Sci. 12, 891–894. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-017-0476-7 (2017).

Velis, M., Conti, K. I. & Biermann, F. Groundwater and human development: synergies and trade-offs within the context of the sustainable development goals. Sustain. Sci. 12, 1007–1017. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-017-0490-9 (2017).

Ai, C., Zhao, L., Han, M., Liu, S. & Wang, Z. Mitigating water imbalance between coastal and inland areas through seawater desalination within China. J. Clean. Prod. 371, 133418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.133418 (2022).

Li, X. & Yang, H. Y. A global challenge: clean drinking water. Glob Chall. 5, 2000125. https://doi.org/10.1002/gch2.202000125 (2021).

Gude, V. G. Desalination and water reuse to address global water scarcity. Reviews Environ. Sci. Bio/Technology. 16, 591–609. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11157-017-9449-7 (2017).

Zubair, M. M., Saleem, H. & Zaidi, S. J. Recent progress in reverse osmosis modeling: an overview. Desalination 564 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2023.116705 (2023).

Kumar, S. P. et al. Overview on reverse osmosis technology for water treatment. ACADEMICIA: Int. Multidisciplinary Res. J. 11, 657–663 (2021).

Eke, J., Yusuf, A., Giwa, A. & Sodiq, A. The global status of desalination: an assessment of current desalination technologies, plants and capacity. Desalination 495 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2020.114633 (2020).

Leon, F., Ramos, A. & Perez-Baez, S. O. Optimization of energy Efficiency, operation Costs, carbon footprint and ecological footprint with reverse osmosis membranes in seawater desalination plants. Membr. (Basel). 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes11100781 (2021).

Elbana, M., Puig-Bargués, J., Pujol, J. & de Cartagena, F. R. Preliminary planning for reclaimed water reuse for agricultural irrigation in the Province of Girona, Catalonia (Spain). Desalination Water Treat. 22, 47–55. https://doi.org/10.5004/dwt.2010.1523 (2010).

Munoz, I. & Fernandez-Alba, A. R. Reducing the environmental impacts of reverse osmosis desalination by using brackish groundwater resources. Water Res. 42, 801–811. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2007.08.021 (2008).

Xue, N. et al. Carbon footprint analysis and carbon neutrality potential of desalination by electrodialysis for different applications. Water Res. 232, 119716. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2023.119716 (2023).

Stokes, J. R. & Horvath, A. Energy and air emission effects of water supply. Environ. Sci. Technol. 43, 2680–2687. https://doi.org/10.1021/es801802h (2009).

Liu, Z. et al. Near-Real-Time carbon emission accounting technology toward carbon neutrality. Engineering 14, 44–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eng.2021.12.019 (2022).

van Soest, H. L., den Elzen, M. G. J. & van Vuuren, D. P. Net-zero emission targets for major emitting countries consistent with the Paris agreement. Nat. Commun. 12, 2140. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-22294-x (2021).

Nabernegg, S., Bednar-Friedl, B., Muñoz, P., Titz, M. & Vogel, J. National policies for global emission reductions: effectiveness of carbon emission reductions in international supply chains. Ecol. Econ. 158, 146–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2018.12.006 (2019).

Gohar, A. A. & Cashman, A. A methodology to assess the impact of climate variability and change on water resources, food security and economic welfare. Agric. Syst. 147, 51–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2016.05.008 (2016).

Liu, L., Wang, X. & Wang, Z. G. Recent progress and emerging strategies for carbon peak and carbon neutrality in China. Greenh. GASES-SCIENCE Technol. 13, 732–759. https://doi.org/10.1002/ghg.2235 (2023).

Nurjanah, I., Chang, T. T., You, S. J., Huang, C. Y. & Sean, W. Y. Reverse osmosis integrated with renewable energy as sustainable technology: A review. Desalination 581, 117590. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2024.117590 (2024).

Feria-Díaz, J. J., Correa-Mahecha, F., López-Méndez, M. C., Rodríguez-Miranda, J. P. & Barrera-Rojas, J. Recent desalination technologies by hybridization and integration with reverse osmosis: A review. WATER 13 https://doi.org/10.3390/w13101369 (2021).

Rodríguez-Calvo, A., Silva-Castro, G. A., Osorio, F., González-López, J. & Calvo, C. Reverse osmosis seawater desalination: current status of membrane systems. Desalination Water Treat. 56, 849–861. https://doi.org/10.1080/19443994.2014.942378 (2015).

Arjmandi, M. et al. Caspian seawater desalination and Whey concentration through forward osmosis (FO)-reverse osmosis (RO) and FO-FO-RO hybrid systems: experimental and theoretical study. J. WATER PROCESS. Eng. 37 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwpe.2020.101492 (2020).

Sun, J. J., Chen, S. Q., Dong, Y. A., Wang, J. F. & Nie, Y. Removal of hardness and silicon by precipitation from reverse osmosis influent: process optimization and economic analysis. J. WATER PROCESS. Eng. 55 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwpe.2023.104147 (2023).

Thummar, U. G. et al. Highly water permeable ‘reverse osmosis’ polyamide membrane of folded nanoscale film morphology. J. WATER PROCESS. Eng. 55 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwpe.2023.104110 (2023).

Wang, H. T., Ao, D., Lu, M. C. & Chang, N. Alteration of the morphology of polyvinylidene fluoride membrane by incorporating MOF-199 nanomaterials for improving water permeation with antifouling and antibacterial property. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 67, 1807–1817. https://doi.org/10.1002/jccs.202000055 (2020).

Wang, H. T. et al. Enhancement of hydrophilicity and the resistance for irreversible fouling of polysulfone (PSF) membrane immobilized with graphene oxide (GO) through chloromethylated and quaternized reaction. Chem. Eng. J. 334, 2068–2078. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2017.11.135 (2018).

Vince, F., Aoustin, E., Bréant, P. & Marechal, F. LCA tool for the environmental evaluation of potable water production. Desalination 220, 37–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2007.01.021 (2008).

Raluy, G., Serra, L. & Uche, J. Life cycle assessment of MSF, MED and RO desalination technologies. Energy 31, 2361–2372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2006.02.005 (2006).

Zhou, J., Chang, V. W. & Fane, A. G. Life cycle assessment for desalination: a review on methodology feasibility and reliability. Water Res. 61, 210–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2014.05.017 (2014).

Ameen, F., Stagner, J. A. & Ting, D. S. K. The carbon footprint and environmental impact assessment of desalination. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 75, 45–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207233.2017.1389567 (2017).

International Organization for Standardization. Environmental management-life cycle assessment-principles and framework. ISO 14040. Geneva: International Organization for Standardization; (2006).

Standard, I. Environmental management-Life Cycle assessment-Requirements and Guidelines Vol. 14044 (ISO, 2006).

Lawler, W. et al. Towards new opportunities for reuse, recycling and disposal of used reverse osmosis membranes. Desalination 299, 103–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2012.05.030 (2012).

Cherif, H. & Belhadj, J. in Sustainable Desalination Handbook 527–559 (2018).

Kavitha, J., Rajalakshmi, M., Phani, A. R. & Padaki, M. Pretreatment processes for seawater reverse osmosis desalination systems—A review. J. Water Process. Eng. 32 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwpe.2019.100926 (2019).

Guo, Y. et al. Environmental life-cycle assessment of municipal solid waste incineration stocks in Chinese industrial parks. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 139, 387–395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2018.05.018 (2018).

Hu, W. et al. Spatiotemporal carbon footprint analysis of bottled water production by ultrafiltration and reverse osmosis. J. Water Process. Eng. 64 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwpe.2024.105576 (2024).

Zhang, H., Zhang, X. & Yuan, J. Driving forces of carbon emissions in china: a provincial analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. Int. 28, 21455–21470. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-11789-7 (2021).

Zou, P., Chen, Q., Yu, Y., Xia, Q. & Kang, C. Electricity markets evolution with the changing generation mix: an empirical analysis based on China 2050 high renewable energy penetration roadmap. Appl. Energy. 185, 56–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2016.10.061 (2017).

Xiao, K., Yu, B., Cheng, L., Li, F. & Fang, D. The effects of CCUS combined with renewable energy penetration under the carbon peak by an SD-CGE model: evidence from China. Appl. Energy. 321 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2022.119396 (2022).

García-Pacheco, R. et al. Transformation of end-of-life RO membranes into NF and UF membranes: evaluation of membrane performance. J. Membr. Sci. 495, 305–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.memsci.2015.08.025 (2015).

Pontié, M. & Old RO membranes: solutions for reuse. Desalination Water Treat. 53, 1492–1498. https://doi.org/10.1080/19443994.2014.943060 (2014).

Tavares, T., Tavares, J., Leon-Zerpa, F. A., Penate-Suarez, B. & Ramos-Martin, A. Assessment of processes to increase the useful life and the reuse of reverse osmosis elements in cape Verde and Macaronesia. Membr. (Basel). 12 https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes12060613 (2022).

Pontié, M., Awad, S., Tazerout, M., Chaouachi, O. & Chaouachi, B. Recycling and energy recovery solutions of end-of-life reverse osmosis (RO) membrane materials: A sustainable approach. Desalination 423, 30–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2017.09.012 (2017).

Ould Mohamedou, E., Penate Suarez, D. B., Vince, F., Jaouen, P. & Pontie, M. New lives for old reverse osmosis (RO) membranes. Desalination 253, 62–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2009.11.032 (2010).

Pontié, M. & Old RO membranes: solutions for reuse. Desalination Water Treat. 53, 1492–1498. https://doi.org/10.1080/19443994.2014.943060 (2015).

Landaburu-Aguirre, J. et al. Fouling prevention, Preparing for re-use and membrane recycling. Towards circular economy in RO desalination. Desalination 393, 16–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2016.04.002 (2016).

Yang, Y. et al. Recycling of composite materials. Chem. Eng. Process. 51, 53–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cep.2011.09.007 (2012).

Xue, N. et al. Carbon footprint analysis and carbon neutrality potential of desalination by electrodialysis for different applications. Water Res. 232 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2023.119716 (2023).

Do Thi, H. T., Pasztor, T., Fozer, D., Manenti, F. & Toth, A. J. Comparison of desalination technologies using renewable energy sources with life Cycle, PESTLE, and Multi-Criteria decision analyses. Water 13 https://doi.org/10.3390/w13213023 (2021).

Lawler, W., Alvarez-Gaitan, J., Leslie, G. & Le-Clech, P. Comparative life cycle assessment of end-of-life options for reverse osmosis membranes. Desalination 357, 45–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2014.10.013 (2015).

Gui, Z., Qi, H. & Wang, S. Study on carbon emissions from an urban water system based on a life cycle assessment: A case study of a typical Multi-Water County in china’s river network plain. Sustainability 16 https://doi.org/10.3390/su16051748 (2024).

Yuan, Y. et al. Deduction of carbon footprint for membrane desalination processes towards carbon neutrality: A case study on electrodeionization for ultrapure water Preparation. Desalination 559 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2023.116648 (2023).

Loganathan, P., Naidu, G. & Vigneswaran, S. Mining valuable minerals from seawater: a critical review. Environ. Science: Water Res. Technol. 3, 37–53. https://doi.org/10.1039/c6ew00268d (2017).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFC3206400, 2023YFE0101000), National Natural Science Foundation (42301181, 42407181), Key Research and Development Program of Shandong Province (2022CXGC020416).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Menghan Zhang: Conceptualization, Date Curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing-Original Draft. Shuling Yu: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project Administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. Cong Shi: Conceptualization, Funding Acquisition, Project Administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Haitao Wang: Conceptualization, Funding Acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Na Chang: Conceptualization, Funding Acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

41598_2025_24518_MOESM2_ESM.xlsx

Supplementary Material 2 Appendix A: This appendix is an extended support material for the carbon footprint assessment of the reverse osmosis water treatment process, mainly including the specific carbon footprint calculation process, detailed definitions of different reverse osmosis water treatment processes and their respective process flow diagrams, the scenario analysis process and the underlying data, and the carbon footprints of a variety of reverse osmosis water treatment process applications under different scenarios. Appendix B: Carbon Footprint Accounting Raw Data.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, M., Yu, S., Shi, C. et al. Carbon footprint analysis and carbon neutrality potential of desalination by reverse osmosis for different applications basd on life cycle assessment method. Sci Rep 15, 40842 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24518-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24518-2