Abstract

In recent years, coinciding with the increasing incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in children and adolescents, the global prevalence of diabetic kidney disease (DKD) and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) are rising year on year. In contrast, the mortality and morbidity due to cardiovascular disease (CVD) and stroke in people with diabetes have been declining. The precise cause of the disparate vascular outcomes in diabetes remains unexplored. To elucidate the relationship, we conducted a retrospective cohort study on the UK Biobank data. In our study, the exposure variables were the age of diabetes and hypertension diagnosis, while the outcome variables were ESRD, myocardial infarction, angina, and stroke. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression models were fitted to assess odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Model performance was evaluated using the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Sensitivity analyses were conducted on participants who developed diabetes before and after the age of 20 years and with and without female participants. Univariable logistic regression showed that compared to those diagnosed after the age of 60, the odds of ESRD for those diagnosed at ages < 20, 20–40, and 41–60 years were 5.26 (3.00 – 9.40), 7.78 (4.81 – 13.16) and 2.33 (1.50 – 3.84), respectively. Myocardial infarction and stroke did not have a statistically significant relationship with younger age of diabetes diagnosis. In those with a dual diagnosis of diabetes and hypertension, irrespective of the age of diabetes diagnosis, the age of hypertension diagnosis at age < 20, 20–40, and 41–60 years, compared to those who developed it after the age of 60 years, had a greater risk of ESRD, 2.20 (1.58 – 3.11), 5.03 (3.79 – 6.81), and 1.53 (1.16 – 2.06), respectively. After adjusting for sex and albuminuria, multivariable logistic regression model 1 showed that compared to those who developed diabetes above the age of 60, those who developed it < 20, 20–40 and 41–60 had a higher risk of ESRD, 4.71 (2.47 – 9.28), 4.67 (2.63 – 8.78), and 1.94 (1.16 – 3.49), respectively. Likewise, in model 2, when the duration of diabetes was used as the explanatory variable, each year of increased duration of diabetes increased the odds of ESRD by 2%, with an odds ratio of 1.02 (1.01–1.03). Younger onset of hypertension but not diabetes increased the odds of myocardial infarction (MI). There was no statistically significant relationship between the age of diabetes, and hypertension diagnoses with angina and stroke. Model performance was excellent, with over 80% of the data points falling below the area under the curve. Sensitivity analyses showed young-onset diabetes as a significant determinant of ESRD. Young-onset and longer-duration of diabetes increase the risk of ESRD. For those with diabetes and hypertension, a younger onset of hypertension but not diabetes may also increase the risk of MI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

End-stage renal disease (ESRD) is one of the most expensive and debilitating complications of diabetes. Over the last three decades, despite a substantial decline in cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality and morbidity in individuals with diabetes, the global burden of ESRD continues to rise1,2,3. According to the Renal Registry UK Report 2022, diabetic kidney disease (DKD) accounted for nearly 30% of the new registrants for renal replacement therapy (RRT)4. Between 2013 and 2022, the proportion of RRT initiated due to DKD rose by 4.2%, while other causes of RRT initiation either declined or remained steady5. Alarmingly, in the UK, in 2022, 8.2% of individuals with DKD requiring RRT were under the age of 54 years, despite the median age for RRT initiation being 64 years, highlighting a significant disparity in RRT initiation age between people with and without diabetes6. With an estimated annual cost of £34,000 per RRT and a significant impact on public health, DKD and its progression to ESRD is a major research priority7.

Young-onset T2DM is a distinct and more aggressive phenotype, and it does not follow a long quiescent phase of steady progression over many years observed in adult-onset T2DM. In contrast, it has unknown and complex genetic and epigenetic karyotype, compared to a well established pathway of metabolic deregulation, associated with insulin resistance in adult-onset8,9. It is a rapidly progressive condition with fast apoptosis and annual decline in pancreatic β-cell function of 20–35%, compared to ~7% in adult-onset T2DM10. Some disparate characteristics of young-onset T2DM compared to the adult-onset are – higher prevalence of obesity (95% vs 50%)11, more pronounced visceral adiposity and hepatic ectopic fat deposition12, heightened insulin signalling deregulation in skeletal muscles, interfering with glucose disposal pathway13, higher level of systemic inflammation, evidenced by an elevated level of high-sensitive C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), Tumour Necrosis Factor alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin 1 beta14,15, increased prevalence of maternal gestational diabetes and intrauterine exposure to hyperglycaemia16, and higher level of pubertal surges in the circulating insulin-antagonistic hormones such as growth hormones, corticosteroid and sex hormones17. These differences in the pathophysiology of young- onset T2DM warrants it to be treated as a distinct disease entity which may have a disparate impact on cardiovascular and renovascular outcomes, than older-onset T2DM.

Traditionally, people with DKD have been more likely to die of CVD before progressing to ESRD. For instance, a nationwide cohort study in Finland showed that the cumulative risk of death within 10 and 20 years from the diagnosis of T2DM was 34% and 64%, respectively, compared to a much lower risk of ESRD at 0.29% and 0.74%18. Multiple studies have shown that people with DKD are 10 to 40 times more likely to die of CVD rather than progressing to ESRD19,20,21. However, emerging global trends of CVD events, mortality and ESRD in people with diabetes indicate an evolving pattern, disparate from the previous norm. While all-cause and CVD mortality among people with diabetes is decreasing22, an increasing number of younger people are developing DKD and progressing to ESRD23. Whether this shift is due to the recent increase in the number of childhood and adolescent developing T2DM is unknown. This study aims to examine the impact of the age of diabetes and hypertension diagnosis on cardiovascular and renovascular outcomes in individuals with diabetes.

Methods

Study design and population

We conducted this retrospective cohort study using data from individuals who completed the UK Biobank study questionnaire. It did not differentiate between the types of diabetes. For this study, we used instance 0, which was the assessment visit. For descriptive analyses, we used the entire cohort, and for exploratory analyses, we used participants with diabetes. The inclusion criteria were self-reported diabetes (UK Biobank data field – 2443, “Diabetes diagnosed by a doctor”), and exclusion criteria were those who did not answer this question or responded as “No”. The study selection process is available in the flow chart. (Supplementary material 1 – Fig. 1). The complete coding schedule is available online (Supplementary material 4). All methods are performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

The UK Biobank is a large, population-based cohort comprising over 500,000 volunteers aged 40–69 years, recruited between 2006 and 2010 from 22 assessment centres across England, Wales and Scotland. During their assessment visits, participants provided electronic consent and completed a touchscreen-based questionnaire. The questionnaire collected extensive demographic and lifestyle information, including current and past medical history, medication use, ethnic and socioeconomic profiles, occupation, educational background, smoking status, dietary habits, exercise habits, and alcohol consumption habits. It also included the ages of diabetes, hypertension and ESRD diagnoses and the ages of starting and stopping smoking24.

Exposure and outcome variables

The population for our study consisted of individuals with diabetes. The exposure was the age at which diabetes and hypertension were diagnosed. The comparison was made among four groups based on the age of diagnosis: < 20, 20–40, 41–60, and > 60 years. The primary outcomes were ESRD, myocardial infarction (MI), angina and stroke, and the secondary outcome was urinary albumin concentration (UAC). The rationale for including hypertension diagnosis age with diabetes was that individuals who develop diabetes at a young age are at a higher risk of developing hypertension, which is an independent risk factor for ESRD25. Moreover, as a part of the metabolic syndrome, diabetes and hypertension often co-exist, and they independently and synergistically interfere with the renovascular endothelial integrity26. Those who reported any of the primary or secondary outcomes, i.e., ESRD, MI, angina, stroke and albuminuria before the onset of diabetes and hypertension, were excluded from the study. The accuracy of participants’ reported diabetes, hypertension, angina, MI, ESRD and stroke were verified by the UK Biobank and were coded on their website. A full description of the codes and their definitions is available on the UK Biobank website and is included in supplementary material 4.

Following the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcome (KDIGO) guidelines27, we defined normoalbuminuria as a UAC value of < 20 mg/dL in a spot urine sample, microalbuminuria as a UAC value of 20–200 mg/dL, and macroalbuminuria as a UAC value > 200 mg/dL. The Townsend deprivation index was used to define deprivation, and based on the index score, the cohort was divided into five quintiles from the least to the most deprived. As almost 94% of the study participants were from white backgrounds, we divided the participants into two groups: white and non-white.

Statistical analyses

By identifying individuals with diabetes and hypertension from the questionnaire, we calculated the duration of diabetes and hypertension by subtracting the age of diagnosis from the participant’s age on the assessment date. For ex-smokers, the duration of smoking was calculated by subtracting the age they stopped smoking from the age they started. For current smokers, the duration was calculated by subtracting the participant’s starting age from their current age.

The baseline characteristics of the participants were stratified into two groups: those with and without diabetes. Descriptive statistics were reported as means ± standard deviation for normally distributed numerical variables and medians with interquartile range (IQR) for non-normally distributed numerical variables. Categorical variables were presented as numbers and percentages. Statistical significance between the two groups, with and without diabetes, was assessed using the Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test for non-parametric numerical variables, an independent Student t-test for parametric numerical variables, and a Chi-squared test for categorical variables.

We selected the longitudinal cohort of eligible UK Biobank study participants with diabetes and followed them until the outcomes of interest, i.e., myocardial infarction, angina, stroke and ESRD. We also analysed the UAC value at the time of assessment visits as a composite secondary outcome marker for ESRD, CVD and stroke. Follow-up time was defined as the interval from the mean age of diabetes diagnosis to the mean age of the occurrence of the events of interest. We also used the age of hypertension diagnosis, the duration of hypertension and diabetes, smoking status, and age of starting and stopping smoking as explanatory variables for stratified analyses. In addition, we did further analyses to explore the relationship between the age of diabetes and hypertension diagnoses and the age of ESRD onset.

A Locally Estimated Scatterplot Smoothing (LOESS) method was applied to explore the UAC trend based on the age of diabetes and hypertension diagnoses and the age of starting smoking in current and ex-smokers who reported ESRD, myocardial infarction, angina and stroke. This method is a suitable method to explore the complex nonlinear relationship between the dependent variable (UAC) and independent variables (i.e., age of diabetes and hypertension diagnoses and age of starting smoking in current and ex-smokers), when a predefined functional form of the relationship is unknown. The young age of starting smoking has been attributed to albuminuria in our previous study28.

We fitted a univariable logistic regression model to assess if the age of diabetes diagnosis can predict ESRD, myocardial infarction, angina and stroke outcomes. We also conducted multivariable logistic regression models to explore the relationship between the age of onset of diabetes and hypertension and ESRD, MI and stroke outcomes. When we used hypertension diagnosis age in the model, we only selected those who reported diabetes. In these models, we did not use the age of diabetes diagnosis; instead, we focused solely on the relationship between the age of hypertension diagnosis and the outcomes of interest, individuals with a concurrent diagnosis of diabetes and hypertension.

As there is an overlapping relationship between the age of diabetes diagnosis and the duration of diabetes, we conducted two separate multivariable logistic regression analyses. To meet the logistic regression model assumptions of multicollinearity and independence, diabetes diagnosis age and duration were analysed in separate models. In model 1, diabetes diagnosis age and in model 2, diabetes duration was used as explanatory variables, while sex and albuminuria were treated as confounding variables.

As we could not distinguish between the types of diabetes from the questionnaires filled out by the respondents of UK Biobank, we conducted a sensitivity analysis excluding those who were diagnosed with diabetes below the age of 20 years. We assumed that this cohort were more likely to have Type 1 Diabetes (T1DM) than T2DM. Furthermore, we conducted a sensitivity analysis excluding females from the dataset to verify the model’s validity, thereby eliminating the influence of sex.

Model discrimination was evaluated using receiver operating characteristics (ROC) and the area under the curve (AUC). The goodness of fit (GOF) was assessed by analysing the calibration plot and Hosmer and Lemeshow GOF test. Concordance with the assumptions of the logistic regression model was assessed using the Durbin-Watson test for the independence of observation and the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) for multicollinearity. Missing data were analysed using Multiple Imputations of Chained Equation (MICE). All analyses were conducted using software R version 4.4.3.

Results

Out of a total of 497,895 eligible study participants who consented to share their data, 5.3% (n = 26,206) had diabetes. Of them, 8.3% (n = 2247) of study participants reported being on insulin, suggesting that the number of T1DM is unlikely to exceed 2247. (Supplementary material 4 – UKB data field 6143). The selection process is in the flow chart. (Supplementary material 1—Fig. 1). The mean follow-up period for people with diabetes who had ESRD, and stroke was 9 years and 11 years, respectively. The follow-up period for myocardial infarction and angina was 12 years. Thus, the total person-years of follow-up for those with ESRD were 235,854 person-years. For stroke, the follow-up period was 288,266 person-years, and myocardial infarction and angina, 314,472 person-years, totalling 838,592 person-years of follow-up. (Supplementary materials 1 – Fig. 2). Apart from age, BMI, and waist circumference, all other numerical variables had a non-parametric distribution. The distribution of numerical variables is represented in the histograms with normality lines. (Supplementary materials 1—Figs. 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9).

ESRD was reported in 0.2% (n = 875) of those without diabetes and 1.2% (n = 303) with diabetes, corresponding to a prevalence rate of ESRD of 200 per 100,000 population without diabetes and 1,200 per 100,000 population in those with diabetes. Macrovascular complications were more prevalent in people with diabetes than without. Angina was reported in 7.5% (n = 1958) of individuals with diabetes compared to 2% (n = 9220) in those without. Myocardial infarction was reported by 8.6% (n = 2250) of individuals with diabetes compared to 2% (n = 9198) in those without. Likewise, in the diabetes group, 2.9% (n = 771) had a stroke compared to 1.1% (n = 5367) in the group without diabetes. Baseline characteristics are summarised in Table 1.

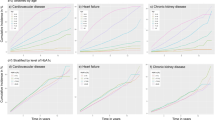

The associations between ages at diabetes and hypertension diagnoses, starting smoking, and UAC trends in individuals who developed ESRD, MI, angina or stroke were assessed using the LOESS method. In ESRD cases, UAC value peaked when diabetes was diagnosed between 15 and 30 and declined with later age of diagnosis (Fig. 1), mirroring trends by diabetes duration (Supplementary Fig. 10). In contrast, UAC values remained steady across different ages and durations of hypertension diagnosis (Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. 10). No association between UAC value and diabetes or hypertension diagnoses age was found in those with MI, angina or stroke (Supplementary Figs. 11, 12, 13).

In individuals with ESRD, UAC values had a monophasic peak in current smokers and had multiple peaks and troughs in ex-smokers based on the age of starting smoking. (Fig. 2). No such relationship was observed in those with MI, angina and stroke (Supplementary Figs. 14, 15, 16).

Scatter plot showing the trend of UAC values based on smoking starting age in current and ex-smokers ((Red line = mean, violet shade = 95% confidence intervals, black dots = UAC values, method = ’loess’ and formula = ’y ~ x’) (Peak UAC in current smokers who started smoking between 15 – 20, in ex-smokers, multiple peaks and troughs in UAC).

ESRD diagnosis age based on diabetes and hypertension diagnosis age

In people with diabetes and ESRD, the mean age of ESRD onset was 57.1 ± 6.6 years. There was a linear relationship between the age of diabetes diagnosis and the age of ESRD diagnosis, showing that the younger the onset of diabetes, the earlier the onset of ESRD. (Fig. 3).

There was a significant difference in the ESRD onset age between sexes based on the age of diabetes and hypertension diagnosis. Females who developed diabetes at an age < 20 years had ESRD at an earlier age than males. On the contrary, males who had hypertension below the age of 20 years had ESRD earlier than females. (Fig. 4).

Univariable logistic regression: ESRD, myocardial infarction, angina and stroke risk

The univariable unadjusted logistic regression model showed that the risk of ESRD is significantly higher in people with diabetes who were diagnosed before the age of 60 years. Compared to those who developed above the age of 60, those who developed diabetes at an age < 20, 20 to 40 and 41 to 60 years, the odds of ESRD were 5.26 (95% CI 3.00 – 9.40), 7.78 (95% CI 4.81 – 13.16) and 2.33 (95% CI 1.50 – 3.84), respectively. Likewise, in people with diabetes and hypertension, compared to those who developed hypertension above the age of 60, the age of diagnosis < 20, 20 to 40 and 41 to 60 years was associated with the odds of ESRD 2.20 (1.58 – 3.11), 5.03 (3.79 – 6.81), and 1.53 (1.16 – 2.06), respectively. There was no statistically significant association between the younger age of diabetes onset with myocardial infarction and stroke. (Table 2).

Adjusted multivariable regression models – ESRD and age of diabetes diagnosis

The logistic regression model was fitted to explore how the univariable model performed when the age of diabetes diagnosis, gender and albuminuria were adjusted in the model. We did not fit the age of diabetes diagnosis and the duration of diabetes in the same model because of interdependence and a violation of the assumption of logistic regression. In Model 1, we adjusted for the age at diabetes diagnosis, and in Model 2, we adjusted for diabetes duration to understand how these risk factors influence ESRD outcomes.

Model 1

In model 1, when age, sex and albuminuria were adjusted, the odds of ESRD compared to those who were diagnosed with diabetes above the age of 60, those who were diagnosed < 20, 20 to 40, and 41 to 60 were 4.71 (95% CI 2.47 – 9.28), 4.67 (95% CI 2.63 – 8.78), 1.94 (95% CI 1.16 – 3.49), respectively. Compared to people with normoalbuminuria, the odds of ESRD in those with microalbuminuria and macroalbuminuria were 3.15 (95% CI, 2.09–4.86) and 25.03 (95% CI, 16.73–38.41), respectively. There was no statistically significant difference in the odds between males and females. (Table 3).

Model 2

Model 2 showed that diabetes duration is also associated with an increased risk of ESRD. The odds of ESRD were increased with a longer duration of diabetes 1.02 (95% CI 1.01 – 1.03). Similarly, compared to those with normoalbuminuria, the odds of ESRD in those with microalbuminuria were 3.23 (95% CI, 2.14–4.98), and those with macroalbuminuria were 27.22 (95% CI, 18.22–41.74). There was no statistically significant relationship between gender and the risk of ESRD.

ESRD, diabetes diagnosis age and diabetes duration—model performance and validation

Discrimination

Both models demonstrated excellent model performance, with the area under the curve (AUC) above 80%. The concordance statistics for model 1 was 81%, and model 2 was 82%, suggesting the model’s performance in predicting true positive cases of ESRD. (Fig. 5).

Calibration

The calibration plots show the reliability of both models in predicting ESRD. The alignment of observed proportions with predicted probabilities indicates robust model performance, supporting their use in clinical decision-making processes. (Fig. 6).

Sensitivity analyses

In this sensitivity analysis, we excluded individuals who reported developing diabetes at a younger age than 20 years. This analysis aimed to elucidate the model’s performance in individuals with a diabetes diagnosis between 20 and 40 years old and between 41 and 60 years old. After excluding people who developed diabetes before age 20, the model showed a significant link between developing diabetes at ages 20–40 or 41–60 years (compared to after age 60 years) and the risk of end-stage kidney disease. (Table 4).

A further sensitivity analysis was conducted to examine model performance by excluding females from the model. It also demonstrated strong model performance and predictive value of the age of diabetes diagnosis concerning ESRD outcome. (Table 5).

Missing data and adherence to the assumptions of logistic regression

Missing data were analysed using the Multiple Imputation of Chained Equations (MICE), as plotted in Supplementary Material 2 (Fig. 17). This analysis indicated that data were likely to be missing randomly rather than systematically.

Logistic regression assumptions were examined for the independence of observation using Durbin-Watson test) and multicollinearity by Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). Both tests showed the models satisfied the assumptions (Supplementary Materials 3).

Discussion

In this large prospective cohort of UK Biobank study participants, we found that people with younger onset and longer duration of diabetes are more likely to develop ESRD than MI, angina or stroke. They are also more likely to develop ESRD at a younger age than those who developed the condition at an older age with a shorter duration of diabetes. Moreover, for those with a dual diagnosis of diabetes and hypertension, irrespective of the age of diabetes diagnosis, younger age of hypertension diagnosis age was a risk factor for ESRD and MI, but not for stroke and angina. Although we could not differentiate between the types of diabetes from the questionnaire, we carried out a sensitivity analysis excluding people who developed diabetes below the age of 20, which virtually removed people with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM). Additionally, we carried out further sensitivity analysis excluding females from the cohort. Both sensitivity analyses confirmed the higher risk of ESRD in individuals who develop diabetes below the age of 40. Albuminuria is consistently associated with ESRD, CVD, angina and stroke outcomes, which is in keeping with previous studies29,30. This study found that current smokers who began smoking before age 20 showed a steady (monophasic) rise in UAC. In contrast, ex-smokers exhibited multiple peaks and troughs. While the exact cause is unclear, this pattern may reflect repeated quit attempts or weight gain after stopping smoking. Interestingly, there has been a gender variation in the age of ESRD onset based on diabetes and hypertension diagnosis age. Females with younger onset diabetes and males with younger onset hypertension developed ESRD early. The precise cause for these observations is unknown and needs further research.

A higher risk of mortality and vascular complications in young-onset T2DM has been described in multiple previous studies. A recently published 30-year follow-up analysis of the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) showed that the standardised mortality rate in young-onset type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) (< 40 years) was 3.72 (2.98–4.64), compared to older onset (≥ 40 years), 1.54 (1.47–1.61)31. Similarly, the incidence of both micro- and macrovascular complications was reported to be higher in young-onset than older onset T2DM25,32. In the USA, the Treatment Options for Type 2 Diabetes and Adolescents and Youth (TODAY) study group has shown early onset and rapid progression of micro- and macrovascular complications in younger-onset T2DM, compared to older onset33. Earlier onset of vascular complications in young-onset T2DM patients, compared to the older-onset, is also reported in other studies34. The novelty of this study is it explored that ESRD risk in individuals with young-onset diabetes is greater than CVD, angina and stroke, and they may develop it earlier than individuals with older onset. These findings have significant clinical and public health implications.

Traditionally, people with T2DM died of CVD and stroke, and therefore, the focus of management was to prevent these complications. However, due to the massive rise in the younger onset of T2DM, people are now living longer and developing DKD at an early age, progressing to ESRD and requiring RRT for an extended period. With the advent of novel pharmacotherapies, such as glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) analogues, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors, and dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors, overall vascular complications and glycaemic control have improved. These drugs exert cardioprotective and reno-protective effects in addition to their glucose-lowering properties35. In the UK, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has recommended SGLT-2 inhibitors in people with microalbuminuria and heart failure even without T2DM36.

While these drugs are routinely used in older-onset T2DM, they are underutilised in young-onset T2DM, primarily due to suboptimal glucose-lowering action37. This disparity in the glycaemic management strategy may explain the recent surge in younger people developing DKD and ESRD. They are often treated with insulin at an early stage, which may help to achieve euglycaemia but may exacerbate vascular complications, particularly microvascular complications, due to insulin-induced frequent glycaemic oscillation leading to oxidative stress38,39. Clinical care pathways and public health policy should consider optimising management of risk factors for the emerging problem of ESRD in younger people with T2DM.

Genotypically and phenotypically, young-onset type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a distinct metabolic dysfunction and warrants a targeted management strategy than older onset disease. In contrast to a metabolic disorder initiated and maintained by insulin resistance in adult-onset T2DM, young-onset T2DM is a ß-cell dysfunction with a complex inheritance pattern, compounded by possible de novo mutation due to epigenetic factors8. A single gene mutation can disrupt glucose sensing, insulin transcription, the KATP channel for insulin release, hepatic glycogenesis and neo-glucogenesis, skeletal muscle uptake of glucose and pancreatic development40. One of the rare variants of young-onset T2DM is Maturity Onset Diabetes of the Young (MODY), an autosomal recessive condition, which is frequently misdiagnosed and mistreated41. The treatment of different types of young-onset T2DM needs a precision medicine approach, as different variant needs different therapeutic strategies42. To achieve this objective, it is necessary to develop a risk prediction model that incorporates genotypic, phenotypic, cardiometabolic, and multi-omics data, which can be used at the primary care level.

The strength of this study lies in its large dataset, which encompasses a diverse range of study participants, and its novel stratified analysis. The areas under the curve above 80% for the age of diabetes diagnosis and duration of diabetes indicate excellent discriminatory power between those who developed ESRD compared to those who did not. Similarly, the calibration plot confirmed good fitness. However, this study has several limitations. We used the questionnaire filled out by the study participants to identify cases of diabetes. It did not specify the type of diabetes. Therefore, we cannot comment on the number of type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) included in the study. However, as the number of people reported to be on insulin was 2247, the number of T1DM cases is unlikely to exceed 8.3%, which is in line with the estimated prevalence of 8% published by Diabetes UK in 202243. Furthermore, to address this limitation, we have conducted a sensitivity analysis by excluding those who developed diabetes below the age of 20 years, which reduces the chance of including people with T1DM in our models.

The study was a retrospective cohort design with limited predictive value. The age of diagnosis of diabetes and ESRD was obtained from the questionnaire and was not verified, which is open to recall bias. UK Biobank is a voluntary dataset and is not representative of real-world data; therefore, the findings may not be generalisable. Almost 94% of the UK Biobank study participants are from a white ethnic background, further limiting generalisability. Similarly, individuals from lower socioeconomic backgrounds were underrepresented in the study cohort. The findings of this study require validation using real-world, nationally representative data before being incorporated into national public health policy guidelines.

Despite the above limitations, the findings of this study indicate that the changing T2DM epidemiology may be affecting ESRD outcomes more disparately than CVD and stroke outcomes, which is of great clinical and public health importance.

The key message is that young-onset T2DM represents a distinct genetic and clinical profile compared to adult-onset T2DM. Given their higher risk of developing ESRD, early screening in this group may aid in timely detection. The rising prevalence of young-onset T2DM could be contributing to the increasing burden of ESRD in middle-aged adults. Developing a risk prediction model that integrates genetic and cardiometabolic biomarkers may help identify high-risk individuals early in the disease course.

Conclusion

Younger onset diabetes and hypertension may be the driver behind the recent surge in ESRD cases. They are more likely to develop it at a younger age, requiring RRT for a longer duration. It can also put enormous pressure on the healthcare budget and loss of productivity. Factors that predispose to young-onset diabetes should be identified and managed as a global priority.

Data availability

UK Biobank data is publicly available and can be obtained by application (www.ukbiobank.ac.uk). This is an open-access article distributed with the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license, which permits others to copy, redistribute, remix, transform and build upon this work for any purpose, provided the original work is properly cited, a link to the license is given, and an indication of whether changes were made. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

References

Yu, Y. et al. Global disease burden attributable to kidney dysfunction, 1990–2019: A health inequality and trend analysis based on the global burden of disease study. Diabetes Res. Clin. Practice 215, 111801 (2024).

Thomas, B. The global burden of diabetic kidney disease: Time trends and gender gaps. Curr. Diab. Rep. 19(4), 1–7 (2019).

Rawshani, A. et al. Mortality and cardiovascular disease in type 1 and type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 376(15), 1407–1418 (2017).

24th Renal Registry Report. https://ukkidney.org/audit-research/annual-report/24th-annual-report-data-31122020. (2022).

UK Renal Registry summary fof annual report: Analyses of adult data to the end of 2021. https://ukkidney.org/sites/renal.org/files/UK%20Renal%20Registry%20Report%202021%20-%20Patient%20Summary_0.pdf. (2023).

Renal registry UK 25th Annual report: UK Kidney Association. https://ukkidney.org/audit-research/annual-report. (2022).

Roberts, G. et al. Current costs of dialysis modalities: A comprehensive analysis within the United Kingdom. Perit. Dial. Int. 42(6), 578–584 (2022).

Kwak, S. H. et al. Genetic architecture and biology of youth-onset type 2 diabetes. Nat. Metab. 6(2), 226–237 (2024).

Srinivasan, S. & Todd, J. The genetics of type 2 diabetes in youth: Where we are and the road ahead. J. Pediatr. 247, 17–21 (2022).

Group TS. Effects of metformin, metformin plus rosiglitazone, and metformin plus lifestyle on insulin sensitivity and β-cell function in TODAY. Diabetes Care 36(6), 1749–1757 (2013).

Magliano, D. J. et al. Young-onset type 2 diabetes mellitus—Implications for morbidity and mortality. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 16(6), 321–331 (2020).

Barrett, T. et al. Rapid progression of type 2 diabetes and related complications in children and young people—A literature review. Pediatr. Diabetes 21(2), 158–172 (2020).

Samuel, V. T. & Shulman, G. I. Integrating mechanisms for insulin resistance: Common threads and missing links. Cell 148(5), 852–871 (2012).

Reinehr, T. et al. Fibroblast growth factor 21 and fetuin-A in obese adolescents with and without type 2 diabetes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 100(8), 3004–3010 (2015).

Reinehr, T. et al. Inflammatory markers in obese adolescents with type 2 diabetes and their relationship to hepatokines and adipokines. J. Pediatr. 173, 131–135 (2016).

Scholtens, D. M. et al. Hyperglycemia and adverse pregnancy outcome follow-up study (HAPO FUS): maternal glycemia and childhood glucose metabolism. Diabetes Care 42(3), 381–392 (2019).

Valaiyapathi, B., Gower, B. & Ashraf, A. P. Pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes in children and adolescents. Curr. Diabetes Rev. 16(3), 220–229 (2020).

Finne, P. et al. Cumulative risk of end-stage renal disease among patients with type 2 diabetes: A nationwide inception cohort study. Diabetes Care 42(4), 539–544 (2019).

Pálsson, R. & Patel, U. D. Cardiovascular complications of diabetic kidney disease. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 21(3), 273–280 (2014).

Collins, A. J. et al. Chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular disease in the Medicare population. Kidney Int. Suppl. 87, S24-31 (2003).

Go, A. S., Chertow, G. M., Fan, D., McCulloch, C. E. & Hsu, C. Y. Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N. Engl. J. Med. 351(13), 1296–1305 (2004).

Raghavan, S. et al. Diabetes mellitus-related all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in a national cohort of adults. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 8(4), e011295 (2019).

Nguyen, N. T. Q. et al. Chronic kidney disease, health-related quality of life and their associated economic burden among a nationally representative sample of community dwelling adults in England. PLoS ONE 13(11), e0207960 (2018).

Sudlow, C. et al. UK biobank: An open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med. 12(3), e1001779 (2015).

Al-Saeed, A. H. et al. An inverse relationship between age of type 2 diabetes onset and complication risk and mortality: The impact of youth-onset type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 39(5), 823–829 (2016).

Tsioufis, C. et al. Effects of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, obesity and other factors on kidney haemodynamics. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 12(3), 537–548 (2014).

Levey, A. S. et al. Definition and classification of chronic kidney disease: A position statement from kidney disease: Improving global outcomes (KDIGO). Kidney Int. 67(6), 2089–2100 (2005).

Debasish, K. et al. Relationship of cardiorenal risk factors with albuminuria based on age, smoking, glycaemic status and BMI: a retrospective cohort study of the UK Biobank data. BMJ Public Health 1(1), e000172 (2023).

Herrera, R. et al. Albuminuria as a marker of kidney and cardio-cerebral vascular damage. Isle of Youth Study (ISYS), Cuba. MEDICC Rev. 12(4), 20–26 (2010).

McKenna, K. & Thompson, C. Microalbuminuria: a marker to increased renal and cardiovascular risk in diabetes mellitus. Scott. Med. J. 42(4), 99–104 (1997).

Lin, B. et al. Younger-onset compared with later-onset type 2 diabetes: an analysis of the UK prospective diabetes study (UKPDS) with up to 30 years of follow-up (UKPDS 92). Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 12, 904–914 (2024).

Amutha, A. et al. Incidence of complications in young-onset diabetes: Comparing type 2 with type 1 (the young diab study). Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 123, 1–8 (2017).

Group TS. Long-term complications in youth-onset type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 385(5), 416–426 (2021).

Dart, A. B. et al. Earlier onset of complications in youth with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 37(2), 436–443 (2014).

Schernthaner, G., Mogensen, C. E. & Schernthaner, G.-H. The effects of GLP-1 analogues, DPP-4 inhibitors and SGLT2 inhibitors on the renal system. Diab. Vasc. Dis. Res. 11(5), 306–323 (2014).

SGLT2 inhibitors - heart failure and chronic kidney disease. (2025).

Strati, M., Moustaki, M., Psaltopoulou, T., Vryonidou, A. & Paschou, S. A. Early onset type 2 diabetes mellitus: an update. Endocrine 85(3), 965–978 (2024).

Zhou, J. J., Coleman, R., Holman, R. R. & Reaven, P. Long-term glucose variability and risk of nephropathy complication in UKPDS, ACCORD and VADT trials. Diabetologia 63(11), 2482–2485 (2020).

Dorajoo, S. R. et al. HbA1c variability in type 2 diabetes is associated with the occurrence of new-onset albuminuria within three years. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 128, 32–39 (2017).

Srinivasan, S. et al. The first genome-wide association study for type 2 diabetes in youth: the Progress in Diabetes Genetics in Youth (ProDiGY) Consortium. Diabetes 70(4), 996–1005 (2021).

Todd, J. N. et al. Monogenic diabetes in youth with presumed type 2 diabetes: results from the progress in diabetes genetics in youth (ProDiGY) collaboration. Diabetes Care 44(10), 2312–2319 (2021).

Dennis, J. M. Precision medicine in type 2 diabetes: Using individualized prediction models to optimize selection of treatment. Diabetes 69(10), 2075–2085 (2020).

How many people in the UK have diabetes?: Diabetes UK; https://www.diabetes.org.uk/about-us/about-the-charity/our-strategy/statistics.

Acknowledgements

The research was conducted using the UK Biobank resource under application no 61894. For the purposes of open access, the authors have applied a Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license to any arising Author Accepted Manuscript version. When appropriate, AI software Grammarly and ChatGPT were used to improve readability without any impact on the study findings and their interpretation.

Funding

This project is funded by the NIHR through a Personal Clinical Lecturer Award to the lead author (CL-2023–2024-001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DK was responsible for conceptualisation, data access, data cleaning, statistical analyses, preparing the figures and tables, and drafting the manuscript. RB, SdeL, and AS contributed to the study’s conceptualisation, data analyses, and supervision and reviewed the manuscript. MN contributed to the statistical analyses. SS, JP, BZ and SK provided clinical insights into the paper. All other co-authors read the draft and commented on it. MM helped with the epidemiology and statistics. AW and AK contributed to clinical input.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The UK Biobank received ethical approval from the Northwest Multicentre Research Ethics Committee (REC reference 11/NW/03820), and all participants provided written informed consent.

Consent for publication

All UKB study participants consented to their data being used for medical research and publication.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kar, D., Molokhia, M., Wierzbicki, A. et al. Comparative risk of end-stage renal disease, myocardial infarction and stroke in young and older onset diabetes in UK Biobank. Sci Rep 15, 39073 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24521-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24521-7