Abstract

Oilfield-produced water is a major environmental concern due to elevated concentrations of dissolved metals, notably Sr, which can form insoluble scales as SrSO₄ and facilitate the co-precipitation of naturally occurring radioactive materials. In this study, for the first time, a biosurfactant extracted from Malva sylvestris leaves, rich in saponins, was explored as a green and biodegradable agent for Sr removal from highly saline produced water collected in western Iran. Batch experiments investigated the effect of temperature (25 °C and 60 °C) and biosurfactant concentration (0.006, 0.015, and 0.024 g/mL) on removal efficiency. The removal mechanism is primarily attributed to coordination between Sr ions and the deprotonated carboxylate groups in saponin molecules, forming stable Sr–saponin complexes. Elevated temperature enhances this process through increased molecular mobility, partial dehydration of Sr2⁺ hydration shells, and favorable thermodynamic shifts, as indicated by Van’t Hoff analysis. Increasing biosurfactant concentration supplies more active binding sites and improves selectivity over competing cations such as Ca2⁺ and Mg2⁺. Time-dependent experiments further revealed that complexation starts after 2 days, and complete sedimentation was observed at the end of the test (day 5). The absence of further Sr reduction between days 5 and 10 indicates the long-term stability of the complexes and their resistance to re-dissolution. A peak Sr removal efficiency of 63.6% was achieved at 60 °C and 0.024 g/mL with no significant change in the pH of the aqueous phase, demonstrating the potential of M. sylvestris for stable and efficient Sr removal from real oilfield produced water. This approach provides a novel, sustainable, and cost-effective alternative to conventional synthetic chemicals for produced water treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Oilfield-produced water is a complex mixture comprising connate water and injected water, which is co-produced during hydrocarbon extraction1. With increasing global demand for fossil fuels and the natural decline in reservoir pressure over time, oilfields are becoming more mature and less productive under primary recovery2. Secondary and enhanced oil recovery (EOR) methods are employed to sustain production, such as water flooding to maintain reservoir pressure, or injecting fluids (water and chemicals) that alter the properties of reservoir rock and fluids to improve oil recovery. As a result, the volume of produced water is expected to rise continuously, potentially reaching 600 million barrels per day, which is twice the amount reported in 20193. Methods of produced water disposal include reinjection into reservoirs for improved recovery, surface discharge after toxicity reduction, and beneficial reuse for agricultural irrigation, livestock/wildlife watering, or potable water supply following proper treatment2. Under stringent environmental regulations, treated produced water with reduced Total Dissolved Solids (TDS) can be discharged into the environment only if it meets specific regulatory thresholds for TDS and other contaminants4. A wide range of contaminants, including chemicals, organic compounds, dissolved and dispersed solids, and heavy metals that are difficult to remove, can damage water resources5. Certain metals, such as strontium(Sr), are present at elevated concentrations and exhibit a distinct tendency to persist within ecosystems for prolonged durations, unlike other substances6. In the Qaidam Basin of China, OPW has Sr concentrations exceeding 100 mg L−17 while in seawater it is only about 7 mg L−18. Reducing the possibility of strontium sulfate (SrSO4) scale formation during underground injection might be achieved by selectively removing Sr from produced water9. The scales cause formation blockage and challenges in oil and gas extraction10,11,12. The environmental impact of SrSO₄ precipitation lies in its role in co-precipitating naturally occurring radioactive materials (NORM), such as radium (Ra). This occurs during produced water injection, transfer, and treatment processes. This can lead to the generation of radioactive waste, which poses challenges for disposal and long-term environmental safety13.

Various treatment methods can be combined and applied to reduce the toxicity level, based on components and water quality14. Methods such as physical15,16,17, chemical18,19,20,21, electrochemical22,23,24, biological25,26,27, and membrane28,29,30 treatments have effectively extracted contaminants31. The efficiency, required reagents, and operational limitations of these methods vary considerably. To provide a clear overview, previous studies on Sr removal from oilfield effluents are summarized in Table 1, highlighting the reported removal efficiencies, applied techniques, and required equipment and chemicals. The reviewed literature underscores the need for cost-effective and environmentally benign alternatives. Chemical methods are favored for their efficiency in removing metals from sludge due to their simple operation processes and short operation times. However, high removal efficiency requires large reagent dosages, leading to high processing costs. Furthermore, these reagents could contribute to secondary pollution affecting both groundwater and soil32. Eco-friendly chemical treatment refers to the use of environmentally benign chemicals or biologically derived agents, such as biosurfactants (natural surfactants)33,34,35, natural coagulants36,37, biomaterials38,39, and Hydrogels40,41 to remove contaminants from produced water with minimal ecological impact. The biosurfactants offer significant potential for improving sustainable produced water treatment processes due to their biodegradable nature, low environmental toxicity, lower carbon footprints, and effectiveness in a wide range of pH and temperature values42,43,44. Saponins are amphiphilic, glycosidic, and heat-stable compounds in the cells of a wide variety of plant leaves that behave as surface-active molecules in the fluid interface due to the presence of both polar (sugar) and nonpolar (steroid or triterpene) groups45,46. The kind of plant, the quantity of sugars, and the chemical composition of the steroid ring all affect the saponin structures47. Biosurfactants are composed of a hydrophilic glycoside combined with a lipophilic derivative that form insoluble complexes with both organics and many cations, so that they can be used as important agents for produced water treatment46,48,49. The efficiency of biosurfactant production is primarily determined by the development of an efficient process that employs low-cost materials and achieves high product yield50. In this study, Malva sylvestris, a self-seeding and low-cost wild plant, was selected as a natural source of biosurfactants for produced water treatment. It is a small, annual plant with hollow stems and a height of up to 0.5 m, from the Malvaceae family, which is often classified as a weed on farms51. Its abundance and low economic value make it an attractive candidate for sustainable applications. Notably, Malva sylvestris leaves contain bioactive compounds, including saponins, which possess surface-active properties beneficial for water remediation processes52. Ramavandi et al.51 used the powdered form of Malva sylvestris to study the effects of pH, adsorbent dose, the metal concentration, and contact time to remove (over 96%) of Hg from aqueous solutions. Salahandish et al.53 declared that the metal concentration and temperature have the most and least influence on the removal of lead (Pb2+) ions from aqueous solutions, respectively.

Several plant-derived biosurfactants have been previously investigated for the removal of heavy metals, particularly for Pb, Hg, and Cd removal49,60,61,62,63, However, to the best of our knowledge, no study has yet reported the application of biosurfactants for the removal of Sr from water. For example, Tang et al. 64 reported over 70% removal efficiency of Pb2⁺ using saponin extracted from tea leaves under optimized pH and concentration conditions. Similarly, Gao et al.65 demonstrated saponin-assisted removal of radioactive metals with removal efficiencies exceeding 80%. For the first time, this study aimed to identify the optimal conditions for the removal of Sr, an alkaline earth metal, from highly saline-produced water collected from an oilfield in Iran using a biosurfactant derived from Malva sylvestris leaves. Unlike previous works, this study systematically evaluates the effects of biosurfactant concentration, temperature, and contact time on Sr removal, while also assessing the time-dependent stability of the formed complexes. The application of Malva sylvestris, an underutilized and locally abundant plant, as a sustainable extractant for Sr removal from oilfield produced water introduces a novel, green, and cost-effective treatment pathway that aligns with waste valorization and circular economy practices.

Materials and methods

This section describes sample collection, biosurfactant extraction, analytical methods, and batch Sr-removal experiments. Subsections provide step-by-step procedures to ensure reproducibility.

Oilfield produced water collection

Produced water samples were collected from an oilfield located in western Iran and filled in high-density polyethylene bottles (Fig. 1a). In order to ensure the consistency and representativeness of the water composition for further analysis, the sample was gathered under monitored conditions. The samples were kept from freezing during transit. No other pretreatment was applied. After 24h, the sample was delivered to the laboratory. The water sample employed in this study was the same as that used in our previous research on chemical removal of Sr21. Utilizing the same sample enables a direct comparison between chemical precipitation and biosurfactant-based complexation approaches under identical water quality conditions. As shown in Fig. 1b, the water is clear, and the physicochemical characteristics of the produced water are shown in Table 2. Inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrometer (ICP-OES, VISTA-PRO, Varian Inc., USA) was used to measure the ions concentration. The pH of the solution was reported as 6.5 at ambient temperature using Sentek pH meter.

Biosurfactant extraction and characteristics

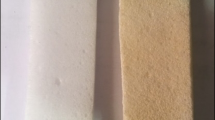

The biosurfactant was extracted from the leaves of Malva sylvestris collected from Tehran, Iran, in January (Fig. 2a). The freshly collected leaves were washed with deionized water to remove surface dust and impurities, cut into small pieces, and dried in an oven (Binder, model FED 115) at 80 °C for three consecutive days to eliminate moisture and volatile organic compounds (Fig. 2b). The dried leaves were then mixed with deionized water at a concentration of 0.03 g/mL and maintained at 80 °C for 3 days, during which the aqueous medium gradually turned light brown, indicating the release of water-soluble metabolites (Fig. 2c). After cooling, the leaf residues were separated using Whatman filter paper No. 42 (Fig. 2d). To confirm the presence of saponins, the filtrate was shaken manually in a glass vial, which generated a stable foam layer (Fig. 2e). Finally, the aqueous extract was left to evaporate at ambient temperature under sterile conditions (Fig. 2f), producing a dry powder of biosurfactant (Fig. 2g), which was stored in airtight containers for subsequent experiments.

Steps of biosurfactant extraction from Malva sylvestris leaves. (a) Fresh leaves as collected; (b) dried leaves at 80 °C for 3 days; (c) extraction in deionized water at 80 °C (0.03 g mL−1) for 3 days; (d) filtered extract; (e) foam formation upon shaking (evidence of saponins); (f) Solution water vaporization; (g) dried biosurfactant powder.

FTIR and NMR spectroscopy

Since the surfactant was extracted in the lab, it was necessary to study its functional groups and chemistry using FTIR and NMR spectroscopy. FTIR analysis was performed using a Frontier (Bruker, Germany) spectrometer to identify the functional groups present in the biosurfactant. The spectra were collected in the range of 4000–400 cm−1 at room temperature. The process of FTIR analysis involves exposing samples to infrared radiation, which affects the atomic vibrations of a molecule in the extracted biosurfactant powder and causes specific energy transmission66. Proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR) spectra were acquired on a VARIAN INOVA 500 MHz spectrometer to elucidate the functional groups of the biosurfactant. The sample was dissolved in deuterated chloroform (CDCl3), and spectra were recorded at room temperature. Chemical shifts (δ) were reported in parts per million (ppm) relative to the residual solvent signal. The principle of 1H NMR is based on the interaction of hydrogen nuclei with an applied external magnetic field. When exposed to a radiofrequency pulse, the hydrogen nuclei resonate at characteristic frequencies depending on their electronic environment. These differences in resonance appear as distinct chemical shifts in the spectrum, which allow the identification of hydrophobic aliphatic chains, carboxyl groups, and other functional moieties present in the biosurfactant.

Strontium removal experiments

Three different biosurfactant concentrations (0.006, 0.015, and 0.024 g/mL) were prepared by dissolving the extracted saponin-rich surfactant in produced water (Fig. 3). The solutions were homogenized using a vortex mixer (IKA Vortex Genius 3, Germany) for 5 min to ensure complete dispersion of the biosurfactant. Each mixture was then transferred into sealed glass vials to minimize evaporation and contamination. The vials were incubated under two different temperature conditions, 25 °C and 60 °C, for a period of 5 days without further agitation to allow the biosurfactant–metal complexes to form and settle. After the settling period, the supernatant was carefully separated from the precipitated complexes using a syringe. The properties of the six prepared samples are summarized in Table 3. Finally, the concentration of residual Sr ion in each supernatant sample was determined using ICP-OES, following standard calibration protocols with appropriate quality control samples.

Results and discussion

This section presents and interprets the main findings of the study. First, spectroscopic analyses (FTIR and 1H NMR) were performed to confirm the molecular structure of the extracted biosurfactant and to identify its functional groups. Then, the strontium removal performance of the biosurfactant was systematically investigated under different operational conditions, including temperature, surfactant concentration, and contact time. In addition, the effects of biosurfactant complexation on the pH of the solution and the long-term stability of the formed Sr–saponin complexes were evaluated. Finally, the environmental significance of strontium removal from produced water is discussed in the context of regulatory considerations.

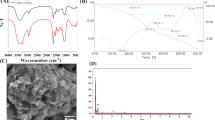

Spectroscopic characterization

To confirm the molecular structure of the extracted biosurfactant and to identify its functional groups, FTIR and 1H NMR spectroscopy were performed as complementary analytical techniques. The spectrum result “transmission versus wavenumber” data is demonstrated in Fig. 4 for FTIR. The characteristic equations were used to obtain the hydroxyl, carbonyl, alcohol, and aliphatic indexes (Table 4). In addition, there is a gas phase absorption peak from CO2, which is a typical artifact in FTIR spectra and does not interfere with the main functional group assignments. The presence of strong absorption bands in the carbonyl and aliphatic regions confirms that the biosurfactant contains both hydrophilic and hydrophobic moieties, consistent with its amphiphilic nature.

To further confirm the molecular structure of the biosurfactant, 1H NMR spectroscopy was carried out. The chemical shifts obtained provide complementary insights into the presence of aliphatic chains, hydroxyl groups, and other functional groups identified by FTIR. The 1H NMR spectrum of the extracted biosurfactant is shown in Fig. 5. The signals observed between 1.0 and 1.3 ppm correspond to hydrogens attached to the aliphatic carbon chain, representing the hydrophobic fraction of the molecule. In contrast, the signals detected between 2.5 and 4.2 ppm provide strong evidence for the presence of hydroxyl groups, which contribute to the hydrophilic nature of the compound. A distinct peak near 4.0 ppm can be attributed to secondary alcohol groups, further supporting the amphiphilic character of the biosurfactant. Additionally, the downfield resonance observed at around 11 ppm is characteristic of carboxyl protons, confirming the presence of –COOH groups77,78,79. These results, in combination with the FTIR findings, validate the presence of both hydrophobic and hydrophilic functional moieties, consistent with the structural features expected for saponin.

Strontium removal

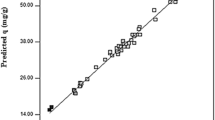

The Sr-Saponin complex was prepared by directly combining the metal-containing aqueous solution and the leaf-derived surfactant. At near-neutral pH, the carboxyl groups in saponin molecules predominantly exist in their deprotonated carboxylate (–COO−) form, which initially promotes electrostatic attraction with Sr ions; this interaction is subsequently stabilized through coordinating covalent bonding involving oxygen donor atoms, leading to complex formation80,81,82. The FTIR analysis revealed characteristic peaks corresponding to asymmetric and symmetric stretching vibrations of the –COO− group, confirming the presence of this functional group in the structure of biosurfactant derived from Malva sylvestris. The schematic illustration of the coordination complex is shown in Fig. 6. The observations of this study are consistent with previous reports on the formation of metal–biosurfactant complexes. For instance, aqueous extracts of Olea europaea and Citrus aurantium were shown to form insoluble coordination complexes with divalent metal ions such as Pb2⁺, Cd2⁺, Zn2⁺, and Co2⁺ through direct complexation with the saponin functional groups (–COO−), followed by precipitation after a certain setting time83. Biosurfactants such as rhamnolipids have been reported to form stable complexes with Pb(II) through coordination of their –COO− groups, highlighting their potential for heavy metal removal81. Similarly, in the present work, the biosurfactant extracted from Malva sylvestris initially dissolved completely in water, while visible precipitates appeared only after several days of interaction with Sr ions. This delayed precipitation behavior further confirms that the mechanism is not simple surface adsorption. In typical adsorption processes, insoluble adsorbents provide surface sites, and ion uptake occurs almost immediately after contact. In contrast, in the present system, the biosurfactant was completely dissolved at the beginning, and visible precipitates only appeared after 2 days, which clearly indicates that Sr removal proceeded through gradual complexation with the –COO− groups of the saponins, followed by precipitation of the formed complexes. Furthermore, an ion-exchange mechanism is unlikely because the –COO− groups are integral parts of the saponin structure and cannot be displaced81. After 5 days of adding the surfactant, the amount of solid complexes in each sample is shown in Fig. 7. The volume of the complexes depends on the setting time, the type of plant, the type and concentration of metal, and pH48,51. In addition, as reported in Table 5, the temperature and concentration significantly influenced Sr removal, with optimal conditions found at 60 °C and a concentration of 0.024 g/mL. Moreover, in the sample prepared with a surfactant concentration of 0.012 g/mL and a reaction temperature of 25 °C, the formed solid complex was not visually detectable to the naked eye. The maximum Sr removal efficiency (63.6%) was achieved at a temperature of 60 °C and the biosurfactant concentration of 0.024 g/mL. The initial concentration of Sr in the produced water, based on which all removal efficiencies were calculated, was 629.4 mg/L, as reported in Table 2. The observed efficiency is promising, especially considering the high concentration of TDS, Na⁺, Ca2⁺, and Mg2⁺ in the produced water sample. High ionic strength can screen the electrostatic interactions between saponin molecules and target Sr ions, reducing the effective binding efficiency and altering the overall dynamics of biosorption processes84. Divalent cations such as Ca2⁺ and Mg2⁺ can significantly compete with Sr ions for binding to –COO− groups in the availability of active sites on the biosurfactant. Moreover, Ca2⁺ often has a lower energy barrier for replacing its hydration shell with carboxylate groups compared to Sr ions, enabling it to more easily occupy coordination sites and potentially reduce the efficiency of Sr removal in high-salinity environments85. While ionic strength and cationic competition are general factors influencing strontium separation, in this study, surfactant concentration and temperature were specifically investigated as the key operational parameters, leading to distinct removal efficiencies under different conditions. The effect of increasing surfactant concentration and temperature on Sr removal efficiency is discussed in the following.

Effect of the temperature

The Sr removal experiments were proceeding at 25 °C and 60 °C. At all surfactant concentrations, the maximum removal occurred at the 60 °C. The increase in temperature was found to enhance the complexation efficiency between the biosurfactant derived from Malva sylvestris leaves and Sr ions. Many chemical and thermodynamic factors can be implicated in this behavior. Higher temperatures typically result in more molecular motion, which makes it easier for metal ions to collide with the –COO− groups of the saponins more frequently58,86,87. Both exothermic and endothermic reactions may experience a shift in chemical equilibrium in response to temperature changes. Since the equilibrium is shifted toward complex creation at higher temperatures, the complexation process seems to be endothermic. The endothermic character of the interaction is further supported by the Van’t Hoff equation (Eq. 1)88, which states that the equilibrium constant increases as temperature rises89. A simplified Van’t Hoff analysis was performed using the removal efficiencies at 60 °C (T1) and 25 °C (T2) for a constant biosurfactant concentration (0.024 g/mL) where K is the equilibrium constant, T is the temperature in Kelvin, and R is the gas constant (8.314 J/mol K). By approximating the removal percentage as proportional to K, the estimated enthalpy change (ΔH°) was found to be approximately + 308 J/mol, indicating a mildly endothermic reaction. This positive value suggests that increasing the temperature of a solution increases the solubility of the ionic compounds, improving the likelihood of complexation, aligning with the observed trend of improved removal efficiency at elevated temperatures90. Increasing the temperature can also enhance the stability of the resulting Sr–saponin complexes due to favorable enthalpic and entropic contributions to the complexation process91,92. Stronger complexation at higher temperatures helps drive the equilibrium forward, leading to more efficient precipitation and removal. Additionally, the surfactant structure may undergo minor conformational changes as a result of temperature, increasing the accessibility and reactivity of binding sites51.

As the final effect, elevated temperatures can also assist in partially dehydrating the Sr ions’ hydration shell, which is typically composed of tightly bound water molecules93. Therefore, the improved removal efficiency at 60 °C can be attributed not only to enhanced molecular motion and thermodynamic favorability but also to increased accessibility of reactive sites under thermal activation. Overall, temperature plays a key role in facilitating Sr–saponin complexation by improving both the kinetics and thermodynamic feasibility of the process. These findings are consistent with the quantitative data in Fig. 5 and Table 4.

Effect of the surfactant concentration

To investigate the influence of biosurfactant dosage, three concentrations (0.006, 0.015, and 0.024 g/mL) were examined for their Sr removal performance. The progressive improvement in Sr2⁺ removal with increasing surfactant dosage is clearly supported by the experimental data, where a nearly threefold increase in efficiency was observed from the lowest to the highest concentration (see Table 4). The enhancement of Sr ion adsorption with an increased biosurfactant concentration is mainly attributed to the greater number of active binding sites (–COO− groups) available for complexation with Sr ions51. Le Chatelier’s principle can also be used to explain how complexation efficiency rises as surfactant concentration increases. The equilibrium changes in favor of the forward reaction as the concentration of free surfactant rises, promoting complex formation. Additionally, at lower concentrations, biosurfactant molecules may form micellar aggregates less efficiently or be insufficient to overcome competition from other divalent cations such as Ca2⁺ and Mg2⁺, which are abundant in the produced water. In contrast, higher biosurfactant concentrations are more capable of outcompeting these ions, improving selectivity and affinity toward Sr ions 94,95.

Effect of the contact time on complexation and stability

Upon initial addition to the produced water, the Malva sylvestris-derived biosurfactant, as an amphiphilic molecule, was completely dissolved, forming a homogeneous solution96. Over the first two days, Sr–saponin complexes began to form, with a portion remaining suspended in the aqueous phase while another fraction settled as precipitates. By day five, nearly all complexes had sedimented, and the supernatant became clear. Figure 8 shows the visual appearance of Sample 1 at the initial time, days 2, 3 and 5, illustrating the gradual formation and sedimentation of Sr–saponin complexes. The observed behavior indicates that the removal process involves initial dissolution of the biosurfactant, followed by complexation, colloidal suspension, and eventual precipitation of stable Sr–saponin complexes. Initially, the complexes remained suspended as colloidal particles, which slowed their immediate precipitation. Over time, the aggregation and growth of particle size increased, leading to gradual sedimentation. This mechanism explains the observed time-dependent decrease in Sr concentration in the supernatant, with near complete settling reached at the end of day 5 (Fig. 9).

Visual observation of Sr–saponin complex formation at different times: (a) Reaction Initialization time—complete dissolution of the biosurfactant in produced water; (b) Day 2—partial sedimentation with suspended complexes visible; (c) Day 5—complete precipitation of Sr–saponin complexes, leaving a clear supernatant.

Temperature plays a key role in both the kinetics and thermodynamics of complex formation. Based on the Arrhenius principle, higher temperatures provide more energy to the reactants, allowing more molecules to overcome the activation energy barrier required for the reaction to occur97. Increasing the concentration of the Malva sylvestris-derived biosurfactant enhances the rate of Sr–saponin complexation. This effect is attributed to the higher availability of biosurfactant molecules, which provide more active binding sites to interact with Sr ions, thereby accelerating complex formation98,99.

The stability of the formed Sr–saponin complexes was evaluated based on both the visual observation of the settled complexes and the Sr concentration in the supernatant over time. The removal tests were conducted over a 5-day period, during which the complexes had fully precipitated. To further evaluate stability, an additional ICP measurement was performed on day 10, which showed no significant increase in Sr concentration (within ± 1% experimental uncertainty, likely due to measurement error), confirming that the complexes remained stable without redissolution. This stability can be attributed to the strong coordination between Sr ions and the –COO− groups of the saponins, which form robust complexes resistant to dissociation under the experimental conditions.

Effect of the complexation on pH

The initial pH of the produced water was measured at 6.5. After the addition of the Malva sylvestris-derived biosurfactant, the pH decreased by approximately 0.2 units in the samples at room temperature which is reported in Table 6. This reduction can be attributed to the deprotonation of the –COO− groups present in the saponins, which coordinate with Sr ions during the complexation process100. The slight drop in pH thus provides indirect evidence for the binding interaction between Sr ions and saponin molecules. After the complexation and subsequent precipitation equilibrated (within 5 days), the pH remained stable, indicating that no significant re-dissolution of the complexes occurred.

Environmental relevance and regulatory considerations

The discharge of Sr-rich produced water into the environment can lead to contamination of surface and groundwater, adversely affecting flora, fauna, and human health101,102. Although regulatory limits for Sr in produced water are not universally established, high Sr concentrations contribute significantly to TDS, which are strictly monitored by international guidelines. Two of the most influential organizations guiding produced water management are the International Association of Oil & Gas Producers (IOGP) and the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). The IOGP issues best-practice recommendations for reducing contaminants and TDS in industrial effluents, promoting environmental safety and operational feasibility in the oil and gas sector103. Similarly, the EPA establishes legally binding frameworks for wastewater discharge and injection through programs such as NPDES and UIC, aiming to protect aquatic resources and maintain ecological balance104. Therefore, effective removal of Sr from produced water is crucial not only to mitigate its direct toxic effects but also to ensure compliance with environmental standards and to reduce the overall ecological footprint of oil and gas operations.

Conclusion

Oilfield produced water contains a variety of toxic metals that can adversely affect both environmental and reservoir systems, among which Sr is of particular concern. The effective removal of Sr is both a technical necessity and an environmental imperative due to its high concentrations, potential to precipitate as scale within reservoir pores, and its role in the co-precipitation of naturally occurring radioactive elements. In this study, Malva sylvestris leaves (which contain saponins, characterized by FTIR and 1H NMR spectroscopy) were used as a novel and green biosurfactant for removing Sr from produced water of an oilfield in the west of Iran. The removal mechanism involves electrostatic coordination of Sr ions with deprotonated carboxylate groups in saponins, leading to the formation and precipitation of Sr–saponin complexes. Thermodynamic analysis suggests the complexation process is mildly endothermic (ΔH° ≈ + 308 J/mol), favoring higher temperatures, which also promote partial dehydration of Sr ions’ hydration shells and enhance kinetic accessibility of binding sites. Increased biosurfactant concentrations improve removal by providing additional active sites and counteracting the competitive effects of abundant divalent cations like Ca2⁺ and Mg2⁺. Batch experiments revealed the effect of contact time on Sr removal, showing that complexation progresses over several days, with maximum removal achieved after 5 days, and no redissolution of complexes observed over 10 days, indicating high stability. The concentration of Sr in the produced water was monitored over time, and the pH of the solution showed negligible variations throughout the treatment. The highest removal efficiency (63.6%) was achieved at 60 °C and 0.024 g/mL, demonstrating the potential of plant-derived biosurfactants in the sustainable treatment of produced water. The application of natural surfactants in water treatment highlights the importance of replacing harmful chemical substances with environmentally friendly alternatives that are also more cost-effective. Given the high concentration of Sr in the produced water sample, its removal contributes to achieving compliance with TDS limits and reducing potential environmental impact. As produced water treatment plays a crucial role in environmental conservation, further research should focus on optimizing the process of removing contaminants and minimizing the ecological impact of extraction agents in practical applications.

Data availability

The data used and analyzed in this study are available at Amirkabir University of Technology and Tarbiat Modares University. Access to the data can be granted upon reasonable request to the corresponding authors.

References

Jiménez, S., Micó, M., Arnaldos, M., Medina, F. & Contreras, S. State of the art of produced water treatment. Chemosphere 192, 186–208 (2018).

Amakiri, K. T., Canon, A. R., Molinari, M. & Angelis-Dimakis, A. Review of oilfield produced water treatment technologies. Chemosphere 298, 134064 (2022).

Garside, M. Daily Demand for Crude Oil Worldwide from 2006 to 2020 (in Million Barrels) (Statista, Rechtsanwalt Maximilian Conrad Raabestr, 2019).

Veil, J. A., Puder, M. G. & Elcock, D. A White Paper Describing Produced Water from Production of Crude Oil, Natural Gas, And Coal Bed Methane (Argonne National Lab, 2004).

Samuel, O. et al. Oilfield-produced water treatment using conventional and membrane-based technologies for beneficial reuse: A critical review. J. Environ. Manag. 308, 114556 (2022).

Cozzarelli, I. M. et al. Environmental signatures and effects of an oil and gas wastewater spill in the Williston Basin, North Dakota. Sci. Total Environ. 579, 1781–1793 (2017).

Liu, C., Yu, X., Ma, C., Guo, Y. & Deng, T. Selective recovery of strontium from oilfield water by ion-imprinted alginate microspheres modified with thioglycollic acid. Chem. Eng. J. 410, 128267 (2021).

Ryu, J. et al. Strontium ion (Sr2+) separation from seawater by hydrothermally structured titanate nanotubes: Removal vs. recovery. Chem. Eng. J. 304, 503–510 (2016).

Shafer-Peltier, K. et al. Removing scale-forming cations from produced waters. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 6, 132–143 (2020).

Ambrose, H. & Kendall, A. Understanding the future of lithium: Part 1, resource model. J. Ind. Ecol. https://doi.org/10.1111/jiec.12949 (2019).

Binmerdhah, A. Scale Formation in Oil Reservoir during Water Injection at High-Barium and High-Salinity Formation Water (2008).

Binmerdhah, A. & Yassin, A. Scale Formation Due to Water Injection in Malaysian Sandstone Cores. Am. J. Appl. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3844/ajassp.2009.1531.1538 (2009).

Zhang, T., Gregory, K., Hammack, R. & Vidic, R. Co-precipitation of radium with barium and strontium sulfate and its impact on the fate of radium during treatment of produced water from unconventional gas extraction. Environ. Sci. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1021/es405168b (2014).

Varjani, S., Joshi, R., Srivastava, V. K., Ngo, H. H. & Guo, W. Treatment of wastewater from petroleum industry: Current practices and perspectives. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 27, 27172–27180 (2020).

Bennett, M. A. & Williams, R. A. Monitoring the operation of an oil/water separator using impedance tomography. Miner. Eng. 17, 605–614 (2004).

Tang, S. et al. Preparation and flotation-flocculation performance evaluation of hydrophobic modified PEI for produced water treatment. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 12, 114940 (2024).

Omar, K. & Vilcaez, J. Removal of toxic metals from petroleum produced water by dolomite filtration. J. Water Process Eng. 47, 102682 (2022).

Duangchan, K., Mohdee, V., Punyain, W. & Pancharoen, U. Mercury elimination from synthetic petroleum produced water using green solvent via liquid-liquid extraction: experimental, effective solubility behaviors and DFT investigation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 11, 109296 (2023).

Chen, W. et al. Recovery of Li⁺ from oilfield produced water using La₂O₃-coated lithium ion-sieves. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 13, 116177 (2025).

Costa Louzada, T. C. et al. New insights in the treatment of real oilfield produced water: Feasibility of adsorption process with coconut husk activated charcoal. J. Water Process. Eng. 54, 104026. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwpe.2023.104026 (2023).

Talebi, M., Rezaei, A. & Rafiei, Y. Application of sodium carbonate and sodium sulfate for removal of lithium and strontium from oilfield produced water. Sci. Rep. 15, 1–9 (2025).

de Oliveira Campos, V. et al. Electrochemical treatment of produced water using Ti/Pt and BDD anode. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 13, 7894–7906 (2018).

Khorram, A. G. et al. Electrochemical-based processes for produced water and oily wastewater treatment: A review. Chemosphere 338, 139565 (2023).

Bai, Y. et al. Advanced treatment of high-temperature heavy oil produced water by electrocoagulation for reuse: Mechanism, performance and pilot-scale test. J. Water Process Eng. 68, 106531. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwpe.2024.106531 (2024).

Yasin, A., Salman, S. & Al-Mayaly, I. Bioremediation of polluted water with crude oil in South Baghdad power plant. Iraqi J. Sci. 55, 113–122 (2014).

Ibrahim, A. N., Hafiz, M. H. & Abdulrazzak, I. A. Treatment of Crude Oil Spills in Water Resources by Using Biological Method. Eng. Technol. J. 37 (2019).

Al-Kaabi, M. A., Zouari, N., Da’na, D. A. & Al-Ghouti, M. A. Adsorptive batch and biological treatments of produced water: Recent progresses, challenges, and potentials. J. Environ. Manag. 290, 112527 (2021).

Siagian, U. W. et al. From waste to resource: Membrane technology for effective treatment and recovery of valuable elements from oilfield produced water. Environ. Pollut. 340, 122717 (2023).

Esham, M. I. M., Ahmad, A. L., Othman, M. H. D. & Adam, M. R. A comprehensive review on low-cost & eco-friendly ceramic hollow fiber membranes for oilfield-produced water treatment: Innovation, efficiency, challenges and future prospects. J. Water Process Eng. 68, 106591 (2024).

Kusworo, T. D. et al. Superior photocatalytic and self-cleaning performance of PVDF-TiO₂@NH₂-MIL-125(Ti)/PVA membranes for efficient produced water treatment. J. Water Process Eng. 72, 107415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwpe.2025.107415 (2025).

Ghafoori, S. et al. New advancements, challenges, and future needs on treatment of oilfield produced water: A state-of-the-art review. Sep. Purif. Technol. 289, 120652 (2022).

Tang, J., He, J., Liu, T. & Xin, X. Removal of heavy metals with sequential sludge washing techniques using saponin: Optimization conditions, kinetics, removal effectiveness, binding intensity, mobility and mechanism. RSC Adv. 7, 33385–33401. https://doi.org/10.1039/C7RA04284A (2017).

Xia, M., Wang, S., Chen, B., Qiu, R. & Fan, G. Enhanced solubilization and biodegradation of HMW-PAHs in water with a pseudomonas Mosselii-released biosurfactant. Polymers 15, 4571 (2023).

Silva, I. A. et al. Production and application of a new biosurfactant for solubilisation and mobilisation of residual oil from sand and seawater. Processes 12, 1605 (2024).

Csutak, O. et al. Candida parapsilosis CMGB-YT biosurfactant for treatment of heavy metal- and microbial-contaminated wastewater. Processes 12, 1471. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr12071471 (2024).

Lourduraj, A., Kishore, U., Veerendra, K. & Srinivas, P. Eco-friendly water purification: Harnessing natural coagulants for sustainable treatment. Int. J. Sci. Res. Comput. Sci. Eng. Inf. Technol. 11, 3037–3047. https://doi.org/10.32628/CSEIT25112776 (2025).

Nisar, N., Koul, B. & Koul, B. Application of Moringa oleifera Lam. Seeds in wastewater treatment. Plant Arch. 21, 2408–2417 (2021).

Thamer, B. M., Al-Aizari, F. A. & Abdo, H. S. Activated carbon-incorporated tragacanth gum hydrogel biocomposite: A promising adsorbent for crystal violet dye removal from aqueous solutions. Gels 9, 959 (2023).

Wen, X. et al. Large-scale converting waste coffee grounds into functional carbon materials as high-efficient adsorbent for organic dyes. Biores. Technol. 272, 92–98 (2019).

Ni, A. et al. Eco-friendly photothermal hydrogel evaporator for efficient solar-driven water purification. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 647, 344–353 (2023).

Huang, Z., Wu, Q., Liu, S., Liu, T. & Zhang, B. A novel biodegradable ??-cyclodextrin-based hydrogel for the removal of heavy metal ions. Carbohydr. Polym. 97, 496–501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.04.047 (2013).

Tripathy, D. B. Biosurfactants: Green frontiers in water remediation. ACS ES&T Water 4, 4721–4740 (2024).

Satpute, S., Banat, I., Dhakephalkar, P., Banpurkar, A. & Chopade, P. B. Biosurfactants, bioemulsifiers and exopolysaccharides from marine microorganisms. Biotechnol. Adv. 28, 436–450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biotechadv.2010.02.006 (2010).

Deravian, B. & Mulligan, C. N. Sustainable recovery of critical minerals from wastes by green biosurfactants: A review. Molecules 30, 2461 (2025).

Rezaei, A., Karami, S., Karimi, A. M., Vatanparast, H. & Sadeghnejad, S. New molecular and macroscopic understandings of novel green chemicals based on Xanthan Gum and bio-surfactants for enhanced oil recovery. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-63244-z (2024).

Shi, J. et al. Saponins from Edible legumes: Chemistry, processing, and health benefits. J. Med. Food 7, 67–78. https://doi.org/10.1089/109662004322984734 (2004).

Rao, V. & Sung, M.-K. Saponin as anticarcinogens. J. Nutr. 125, 717S-724S. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/125.3_Suppl.717S (1995).

Abed-El-Aziz, M. & Madbouly, H. A. Investigations on green preparation of heavy metal saponin complexes. J. Water Environ. Nanotechnol. 2, 103–111 (2017).

Gao, L. et al. Behavior and distribution of heavy metals including rare earth elements, thorium, and uranium in sludge from industry water treatment plant and recovery method of metals by biosurfactants application. Bioinorg. Chem. Appl. 2012, 173819. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/173819 (2012).

Santos, D. et al. Synthesis and evaluation of biosurfactant produced by Candida lipolytica using animal fat and corn steep liquor. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 105, 43–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petrol.2013.03.028 (2013).

Ramavandi, B., Rahbar, A. R. & Sahebi, S. Effective removal of Hg2+ from aqueous solutions and seawater by Malva sylvestris. Desalin. Water Treat. 57, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/19443994.2015.1136695 (2016).

Batiha, G. et al. The phytochemical profiling, pharmacological activities, and safety of malva sylvestris: a review. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 396, 3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00210-022-02329-w (2022).

Salahandish, R., Ghaffarinejad, A. & Norouzbeigi, R. Rapid and efficient lead (II) ion removal from aqueous solutions using Malva sylvestris flower as a green biosorbent. Anal. Methods https://doi.org/10.1039/C5AY02681D (2016).

Finklea, H., Lin, L.-S. & Khajouei, G. Electrodialysis of softened produced water from shale gas development. J. Water Process Eng. 45, 102486 (2022).

Patil, A., Nanda, J. & Waikar, J. In SPE International Conference on Oilfield Chemistry? D021S009R010 (SPE).

Jang, E., Jang, Y. & Chung, E. Lithium recovery from shale gas produced water using solvent extraction. Appl. Geochem. 78, 343–350 (2017).

Mansour, M. S., Abdel-Shafy, H. I., El Tony, M. M. & El Azab, W. I. Hybrid resin composite membrane for oil & gas produced water treatment. Egypt. J. Pet. 31, 83–88 (2022).

Talebi, M., Rezaei, A. & Rafiei, Y. Application of sodium carbonate and sodium sulfate for removal of lithium and strontium from oilfield produced water. Sci. Rep. 15, 18895 (2025).

Esmaeilirad, N., Terry, C., Kennedy, H., Li, G. & Carlson, K. Optimizing metal-removal processes for produced water with electrocoagulation. Oil Gas Facil. 4, 087–096 (2015).

Saleem, H. & Banat, F. Regeneration and reuse of bio-surfactant to produce colloidal gas aphrons for heavy metal ions removal using single and multistage cascade flotation. J. Clean. Product. (2018).

Yuan, X.-Z., Meng, Y.-T., Zeng, G., Fang, Y. & Shi, J. Evaluation of tea-derived biosurfactant on removing heavy metal ions from dilute wastewater by ion flotation. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Aspects 317, 256–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2007.10.024 (2008).

Aryanti, N., Nafiunisa, A., Giraldi, V. & Buchori, L. Separation of organic compounds and metal ions by micellar-enhanced ultrafiltration using plant-based natural surfactant (Saponin). Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 8, 100367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscee.2023.100367 (2023).

Liu, Z. et al. Recent advances in the environmental applications of biosurfactant saponins: A review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2017.11.021 (2017).

Tang, J., He, J., Liu, T. & Xin, X. Removal of heavy metals with sequential sludge washing techniques using saponin: Optimization conditions, kinetics, removal effectiveness, binding intensity, mobility and mechanism. RSC Adv. 7, 33385–33401 (2017).

Gao, L. et al. Behavior and distribution of heavy metals including rare earth elements, thorium, and uranium in sludge from industry water treatment plant and recovery method of metals by biosurfactants application. Bioinorg. Chem. Appl. 2012, 173819 (2012).

Kirk-Othmer. Kirk-Othmer Concise Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology, 2 Volume Set. (Wiley, 2007).

Socrates, G. Infrared and Raman Characteristic Group Frequencies: Tables and Charts (Wiley, 2004).

Wang, W., Izarova, N. V., van Leusen, J. & Kögerler, P. A phosphonate–lanthanoid polyoxometalate coordination polymer:{Ce 2 P 2 W 16 O 60 L 2} n zipper chains. CrystEngComm 23, 5989–5993 (2021).

Dovbeshko, G. et al. Surface enhanced IR absorption of nucleic acids from tumor cells: FTIR reflectance study. Biopolym. Orig. Res. Biomol. 67, 470–486 (2002).

Wu, J. G. et al. Distinguishing malignant from normal oral tissues using FTIR fiber-optic techniques. Biopolym. Orig. Res. Biomol. 62, 185–192 (2001).

Li, J., Guo, J. & Dai, H. Probing dissolved CO2 (aq) in aqueous solutions for CO2 electroreduction and storage. Sci. Adv. 8, eabo0399 (2022).

Nandiyanto, A. B. D., Oktiani, R. & Ragadhita, R. How to read and interpret FTIR spectroscope of organic material. Indones. J. Sci. Technol. 4, 97–118 (2019).

Wood, B. R. et al. FTIR microspectroscopic study of cell types and potential confounding variables in screening for cervical malignancies. Biospectroscopy 4, 75–91 (1998).

Stuart, B. H. Infrared Spectroscopy: Fundamentals and Applications (Wiley, 2004).

Pavia, D. L., Lampman, G. M., Kriz, G. S. & Vyvyan, J. R. Introduction to Spectroscopy (2015).

FTIR Analysis - Interpret your FTIR data quickly, <https://unitechlink.com/ftir-analysis/> (2023).

Fulmer, G. R. et al. NMR chemical shifts of trace impurities: common laboratory solvents, organics, and gases in deuterated solvents relevant to the organometallic chemist. Organometallics 29, 2176–2179 (2010).

al., M. e. Spectroscopy of Carboxylic Acids and Nitriles; https://chem.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Organic_Chemistry/Organic_Chemistry_(Morsch_et_al.)/20%3A_Carboxylic_Acids_and_Nitriles/20.08%3A_Spectroscopy_of_Carboxylic_Acids_and_Nitriles

da Rocha Junior, R. B. et al. Application of a low-cost biosurfactant in heavy metal remediation processes. Biodegradation 30, 215–233 (2019).

Ochoa-Loza, F. J., Artiola, J. F. & Maier, R. M. Stability constants for the complexation of various metals with a rhamnolipid biosurfactant. J. Environ. Qual. 30, 479–485 (2001).

Hari, O. & Upadhyay, S. K. Rhamnolipid–metal ions (CrVI and PbII) complexes: Spectrophotometric, conductometric, and surface tension measurement studies. J. Surfactants Deterg. 24, 281–288 (2021).

Hogan, D. E., Curry, J. E., Pemberton, J. E. & Maier, R. M. Rhamnolipid biosurfactant complexation of rare earth elements. J. Hazard. Mater. 340, 171–178 (2017).

Abed El Aziz, M., Ashour, A., Madbouly, H., Melad, A. S. & El Kerikshi, K. Investigations on green preparation of heavy metal saponin complexes. J. Water Environ. Nanotechnol. 2, 103–111 (2017).

Aranda-García, E., Chávez-Camarillo, G. M. & Cristiani-Urbina, E. Effect of Ionic strength and coexisting ions on the biosorption of divalent nickel by the acorn shell of the Oak Quercus crassipes Humb. & Bonpl. Processes 8, 1229 (2020).

Hamm, L. M., Wallace, A. F. & Dove, P. M. Molecular dynamics of ion hydration in the presence of small carboxylated molecules and implications for calcification. J. Phys. Chem. B 114, 10488–10495 (2010).

Chen, S., Dong, K., Xia, C., Kong, L. & Tang, Y. In AIP Conference Proceedings. 020058 (AIP Publishing LLC).

Wu, J. F., Tai, C. Y., Yang, W. K. & Leu, L. P. Temperature effects on the crystallization kinetics of size-dependent systems in a continuous mixed-suspension mixed-product removal crystallizer. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 30, 2226–2233 (1991).

Jr, I. Interpretation and Significance of the Alternative Formulation of Van’t Hoff Equation. Acad. J. Chem. (2018). https://doi.org/10.32861/jac.41.01.03

Hoff, J. H. Lois de l’équilibre chimique dans l’état dilué, gazeux ou dissous. [Une propriété générale de la matière diluée. Conditions électriques de l’équilibre chimique.] Par J.H. Van ‘t Hoff. Mémoire présenté à l’Académie roy. des sciences de Suède, le 14 octobre 1885. (P.A. Norstedt och söner, 1886).

Nwanak, S. Impact of temperature on the solubility of ionic compounds in water in Cameroon. J. Chem. 3, 42–51 (2024).

Samadfam, M., Niitsu, Y., Sato, S. & Ohashi, H. Complexation thermodynamics of Sr (II) and humic acid. Radiochim. Acta 73, 211–216 (1996).

Liu, M. et al. Contribution of surface functional groups and interface interaction to biosorption of strontium ions by Saccharomyces cerevisiae under culture conditions. RSC Adv. 7, 50880–50888 (2017).

Driesner, T. & Cummings, P. T. Molecular simulation of the temperature-and density-dependence of ionic hydration in aqueous SrCl2 solutions using rigid and flexible water models. J. Chem. Phys. 111, 5141–5149 (1999).

Hong, J.-J., Yang, S.-M., Lee, C.-H., Choi, Y.-K. & Kajiuchi, T. Ultrafiltration of divalent metal cations from aqueous solution using polycarboxylic acid type biosurfactant. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 202, 63–73 (1998).

Chen, Y. et al. Preparation of porous composite phase Na super ionic conductor adsorbent by in situ process for ultrafast and efficient strontium adsorption from wastewater. Metals 13, 677 (2023).

Santos, D. K. F., Rufino, R. D., Luna, J. M., Santos, V. A. & Sarubbo, L. A. Biosurfactants: Multifunctional biomolecules of the 21st century. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 17, 401 (2016).

Arrhenius, S. Über die Dissociationswärme und den Einfluss der Temperatur auf den Dissociationsgrad der Elektrolyte. Z. Phys. Chem. 4, 96–116 (1889).

Kim, H. S. & Tondre, C. On a possible role of microemulssons for achieving the separation of Ni2+ and Co2+ from their mixtures on a kinetic basis. Sep. Sci. Technol. 24, 485–493 (1989).

Kamio, E., Miura, H., Matsumoto, M. & Kondo, K. Extraction mechanism of metal ions on the interface between aqueous and organic phases at a high concentration of organophosphorus extractant. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 45, 1105–1112 (2006).

Gudiña, E. J., Teixeira, J. A. & Rodrigues, L. R. Biosurfactants produced by marine microorganisms with therapeutic applications. Mar. Drugs 14, 38 (2016).

Srikhumsuk, P., Peshkur, T., Renshaw, J. C. & Knapp, C. W. Toxicological response and bioaccumulation of strontium in Festuca rubra L. (red fescue) and Trifolium pratense L. (red clover) in contaminated soil microcosms. Environ. Syst. Res. 12, 15 (2023).

Kalingan, M., Rajagopal, S. & Venkatachalam, R. Effect of metal stress due to strontium and the mechanisms of tolerating it by Amaranthus caudatus Linn. Biochem. Physiol 5 (2016).

Guidelines for waste management focusing on areas with limited infrastructure. https://www.iogp.org/bookstore/product/guidelines-for-waste-management-focusing-on-areas-with-limited-infrastructure/.

NPDES Regulations. https://www.epa.gov/npdes/npdes-regulations?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank every person who helped perform the analyses required to complete this project, including Amirkabir University of Technology and the people at the Lab at the University of Tarbiat Modares. The authors also thank Mr.Talebi for helping collect the produced water sample.

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.T.: Methodology, Conceptualization, Data analysis, Writing, and Editing; A.R.: Methodology, Conceptualization, Data analysis, and Resources. Y. R.: Methodology, Conceptualization, Supervision, and Review.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Talebi, M., Rezaei, A. & Rafiei, Y. Eco-friendly removal of strontium from produced water of an oilfield in western Iran using biosurfactant derived from Malva sylvestris leaves. Sci Rep 15, 40804 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24590-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24590-8