Abstract

The coordinated operation of hybrid photovoltaic (PV) and Small Modular Reactor (SMR) microgrids represents a promising pathway to achieve resilient, low-carbon energy supply in modern power systems. However, effective management of such systems requires advanced optimization frameworks that simultaneously address cost minimization, carbon emission reduction, and operational resilience under multi-source uncertainties. This paper proposes a comprehensive scheduling framework for hybrid PV-SMR microgrids, integrating multi-scale energy storage–lithium-ion batteries for short-term balancing and hydrogen storage for long-term seasonal regulation–while explicitly incorporating demand response flexibility. The proposed framework adopts a multi-objective distributionally robust optimization (DRO) approach to capture uncertainties in solar generation and load fluctuations, ensuring robust yet cost-effective dispatch decisions. The mathematical model addresses the multi-timescale coordination between variable PV generation, slow-ramping nuclear power, and dynamic battery and hydrogen storage operations. Key constraints include power balance, SMR ramping limits, battery state-of-charge evolution, hydrogen production and consumption cycles, and resilience-driven critical load prioritization. Furthermore, a real-time reinforcement learning (RL)-assisted mechanism enhances the system’s adaptability to evolving operational states, enabling dynamic adjustment of storage and demand response strategies based on live system feedback. A comprehensive case study is conducted on a 100 MW hybrid microgrid, integrating 40 MW of PV, a 50 MW SMR, a 20 MWh battery storage system, and a 15-ton hydrogen storage facility, supplying industrial and residential loads under realistic uncertainty scenarios. Results demonstrate that the proposed optimization achieves a 17.5% reduction in operational cost and a 32.8% reduction in carbon emissions compared to conventional microgrid scheduling, while enhancing resilience by maintaining continuous supply for critical loads even under extreme weather stress. The integration of DRO and reinforcement learning provides a 28% improvement in flexibility under solar variability, confirming the importance of adaptive, uncertainty-aware optimization for future hybrid microgrids. This work contributes an advanced, scalable framework for multi-energy hybrid microgrid management, providing valuable insights for resilient and low-carbon community microgrid development in the renewable-dominated era.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The integration of renewable energy sources has become a critical component in modern power systems as the global energy sector transitions toward sustainability. Among various renewable technologies, photovoltaic systems have gained significant attention due to their scalability, cost-effectiveness, and environmental benefits1,2. However, the inherent intermittency of solar energy creates operational challenges, as fluctuations in solar irradiance can lead to unstable power generation and reduced reliability in microgrid operations. To address this issue, there is a growing interest in hybrid energy systems that combine photovoltaics with other stable and dispatchable energy sources3. Small Modular Reactors have emerged as a promising complementary technology, offering reliable baseload power with minimal carbon emissions4,5. Unlike conventional large-scale nuclear reactors, Small Modular Reactors provide flexibility in deployment, lower initial investment costs, and enhanced safety features. Their modular nature allows for incremental capacity expansion, making them suitable for integration within microgrids that require both resilience and reliability. Despite the promising potential of hybrid photovoltaic and Small Modular Reactor systems, there remain significant challenges in their coordination and optimal operation6. The unpredictable nature of solar generation necessitates an intelligent energy management strategy that dynamically balances the output of photovoltaic arrays, nuclear generation, and storage resources7,8. The presence of battery and hydrogen storage systems further complicates operational decisions, as energy dispatch must consider charge-discharge cycles, degradation effects, and long-term storage efficiency. Demand-side response mechanisms also play a crucial role in adapting energy consumption patterns to available generation, thereby enhancing the flexibility of the microgrid. Coordinating these diverse energy components under uncertainty requires an advanced optimization framework capable of simultaneously addressing cost minimization, emissions reduction, resilience enhancement, and grid stability.

This paper presents a novel optimization framework for the coordinated operation of hybrid photovoltaic and Small Modular Reactor microgrids, incorporating battery and hydrogen storage for enhanced flexibility and resilience. The proposed model aims to provide an efficient scheduling mechanism that dynamically adjusts power generation, storage utilization, and demand response to ensure reliable and cost-effective energy management. A multi-objective optimization approach is developed to minimize operational costs, reduce carbon emissions, and maximize resilience by ensuring adequate power supply for critical loads. The optimization formulation incorporates power balance constraints, ramping limitations of nuclear reactors, photovoltaic generation intermittency, and energy storage dynamics. The introduction of distributionally robust optimization techniques allows for handling uncertainties in solar generation and demand fluctuations by ensuring that photovoltaic power dispatch meets predefined reliability thresholds. This approach enhances the adaptability of the microgrid while mitigating risks associated with renewable energy variability.

Uncertainty modeling in energy markets has been extensively explored through several established approaches. Stochastic programming has been widely applied to represent variability in renewable generation and demand using probabilistic scenarios, providing planners with a structured way to account for expected performance under diverse conditions. However, its reliance on numerous scenarios often results in high computational complexity, limiting its applicability in large-scale or real-time operations. Scenario-based methods offer more flexibility by explicitly constructing representative operating conditions, yet the accuracy of the results heavily depends on the quality of scenario selection. Conditional Value-at-Risk (CVaR), introduced from financial optimization, has also been adapted to energy system planning to mitigate extreme-event risks; while effective for hedging tail risks, CVaR-based models may lead to overly conservative outcomes. Recent works, such as “A Distributed Market-Aided Restoration Approach of Multi-Energy Distribution Systems Considering Comprehensive Uncertainties from Typhoon Disaster” and “Risk-averse stochastic capacity planning and P2P trading collaborative optimization for multi-energy microgrids considering carbon emission limitations: An asymmetric Nash bargaining approach,” exemplify these approaches in restoration and planning contexts. In contrast, this study advances the literature by adopting distributionally robust optimization (DRO), which captures uncertainty through ambiguity sets of probability distributions, ensuring tractability while avoiding excessive conservatism, and by further integrating reinforcement learning to enhance adaptability to evolving system states.

Unlike previous studies that focus on either renewable-dominated microgrid operation or nuclear-based energy systems, this paper presents a holistic hybrid energy management framework that integrates multiple energy sources under a single optimization paradigm. The novelty of this research lies in the co-optimization of photovoltaic and Small Modular Reactor generation, combined with a robust uncertainty-aware dispatch mechanism that accounts for both short-term and long-term storage dynamics. While conventional scheduling approaches rely on deterministic models that do not fully capture the stochastic nature of renewable energy, the proposed distributionally robust optimization framework explicitly models uncertainty in solar generation and demand response, improving the reliability and efficiency of microgrid operation. By integrating reinforcement learning techniques, the framework also enhances real-time adaptability, ensuring that energy dispatch strategies evolve based on changing environmental conditions and grid constraints.

This research makes several important contributions to the field of hybrid microgrid operation. First, a multi-layered optimization model is developed to coordinate the scheduling of photovoltaic generation, Small Modular Reactor output, and energy storage while minimizing costs and emissions. The formulation accounts for nuclear reactor ramping constraints, power balance conditions, and grid reliability requirements, providing a comprehensive framework for decision-making. Second, a resilience-oriented energy dispatch model is introduced to allocate backup power from multiple sources, ensuring continuous energy supply for critical infrastructure. By leveraging nuclear, battery, and hydrogen storage resources, the framework improves microgrid survivability under variable conditions. Third, the integration of a distributionally robust optimization approach enables the system to handle uncertainty in photovoltaic generation and demand fluctuations, ensuring that renewable energy utilization remains reliable despite intermittencies. Fourth, the paper implements an adaptive scheduling mechanism that enhances real-time decision-making capabilities, incorporating reinforcement learning techniques to refine energy management strategies based on observed system behavior.

Recent research has widely examined hybrid PV–wind–battery systems, which exploit the complementary intermittency of solar and wind resources while using batteries for balancing. Although such frameworks improve renewable utilization, their dependence on finite storage capacity and variable wind availability constrains long-duration reliability. In contrast, the PV–SMR configuration integrates dispatchable nuclear output with intermittent solar generation, thereby reducing storage oversizing requirements and providing a firmer, more resilient low-carbon backbone.

It is important to distinguish the novelty of the proposed framework relative to existing hybrid optimization studies. Conventional frameworks typically focus on PV–wind–battery systems and employ deterministic or scenario-based scheduling methods, which are limited in capturing long-term uncertainties and system heterogeneity. By contrast, our approach uniquely integrates distributionally robust optimization with reinforcement learning to enable adaptive scheduling under uncertainty, while explicitly modeling the interaction between PV generation and dispatchable SMR output. This combination not only enhances system resilience and cost-effectiveness but also establishes a more generalizable paradigm for hybrid microgrid operation. In this way, the proposed framework goes beyond incremental extensions of prior work and provides a distinct methodological contribution.

Literature review

Research on photovoltaic-based microgrids has primarily focused on addressing the intermittency and variability of solar generation. Photovoltaic energy production is inherently dependent on weather conditions, which leads to fluctuations in power availability9,10. Various studies have proposed optimization frameworks for managing solar generation in microgrids. Some approaches use deterministic scheduling models to optimize photovoltaic dispatch under ideal conditions, but these models fail to account for uncertainty in solar power output. Stochastic and robust optimization methods have been introduced to mitigate this challenge, allowing for more reliable photovoltaic integration by incorporating probabilistic constraints3,11,12. However, these models often require extensive historical data and computational resources, making their real-time implementation complex. Recent advancements in distributionally robust optimization techniques have provided a more flexible approach to handling uncertainty by optimizing against the worst-case probability distributions of solar generation. These methods ensure that photovoltaic power dispatch remains reliable under varying environmental conditions13,14.

Small Modular Reactors have been increasingly considered as a complementary energy source for microgrid operation due to their stable and dispatchable power generation capabilities. Unlike traditional large-scale nuclear reactors, Small Modular Reactors offer modular deployment, passive safety features, and enhanced load-following capabilities, making them suitable for integration with variable renewable energy sources15. Several studies have analyzed the economic feasibility and environmental benefits of nuclear-renewable hybrid systems, demonstrating that Small Modular Reactors can effectively provide baseload power while mitigating the intermittency of renewable sources16. The ability of Small Modular Reactors to operate flexibly and adjust their output in response to fluctuating demand has been a key area of research. However, nuclear reactor ramping constraints and thermal inertia limit the extent to which Small Modular Reactors can provide fast-response power balancing17,18. Existing studies have proposed hybrid operation strategies that combine nuclear and battery storage to improve system flexibility, but limited research has been conducted on co-optimizing Small Modular Reactor output with hydrogen storage in microgrid environments19,20.

The role of energy storage in hybrid microgrid operation has been widely explored, with a particular focus on battery and hydrogen storage systems. Battery storage is commonly used for short-term energy buffering, providing rapid response to fluctuations in generation and demand21,22. Research has investigated various battery energy management strategies, including state-of-charge optimization, degradation-aware scheduling, and multi-objective dispatch algorithms23. The integration of hydrogen storage has also gained attention due to its potential for long-term energy balancing. Hydrogen can be produced via electrolysis during periods of excess renewable generation and later converted back into electricity using fuel cells. Studies on hydrogen energy systems have examined the efficiency and economic viability of electrolysis-based storage, highlighting its potential as a scalable and sustainable solution for large-scale energy storage24. However, the co-optimization of battery and hydrogen storage in a hybrid photovoltaic-Small Modular Reactor microgrid remains underexplored. Existing models typically treat battery and hydrogen storage independently, rather than as a coordinated energy management strategy. Recent studies have further advanced the role of safe reinforcement learning in microgrid coordination. For example,25 proposed a multi-level structure where safe RL ensures decentralized operation without violating safety constraints. Similarly,26 introduced hydrogen-based flexibility in a multi-energy context, combining policy learning with congestion management. Compared with these studies, the present work focuses on the coordinated operation of PV–SMR hybrid microgrids by integrating DRO-based uncertainty modeling with RL-assisted scheduling. This combination explicitly addresses both distributional uncertainty and real-time adaptability, providing a distinct contribution to the field.

Optimization techniques for hybrid microgrid operation have evolved from deterministic models to more sophisticated stochastic and robust approaches. Traditional mixed-integer linear programming and dynamic programming methods have been widely used for microgrid scheduling, but their computational complexity limits their scalability in large-scale hybrid systems27,28. More recently, reinforcement learning has emerged as a promising method for adaptive energy management. Reinforcement learning algorithms can learn optimal scheduling strategies based on historical data and real-time observations, making them well-suited for handling dynamic and uncertain environments29. Several studies have applied reinforcement learning to microgrid operation, demonstrating its ability to improve decision-making under uncertainty30. However, reinforcement learning-based scheduling for hybrid photovoltaic-Small Modular Reactor microgrids remains relatively unexplored. Existing applications of reinforcement learning in microgrid optimization have primarily focused on renewable-battery systems, without incorporating nuclear generation and hydrogen storage dynamics.

Mathematical modeling and method

To develop a coordinated optimization framework capable of balancing cost, carbon emissions, and resilience for hybrid PV-SMR microgrids, this section formulates a detailed mathematical model encompassing generation, storage, and demand response dynamics. The model integrates operational constraints of photovoltaic generation, SMR flexibility limits, battery state-of-charge evolution, hydrogen production and consumption, and demand-side flexibility. These elements are formulated into a multi-objective optimization problem designed to capture the complex trade-offs between economic efficiency, environmental sustainability, and operational robustness under uncertainty. To solve this comprehensive problem, the proposed method adopts a hybrid approach combining distributionally robust optimization (DRO) for uncertainty handling and reinforcement learning-assisted adaptive scheduling for real-time operational adjustments. The DRO component constructs ambiguity sets to account for uncertain solar generation and fluctuating demand profiles, ensuring robust decision-making against worst-case probabilistic scenarios. Simultaneously, reinforcement learning enhances flexibility by continuously updating microgrid scheduling policies based on real-time feedback, capturing non-stationary operational conditions.

The proposed methodology integrates DRO with RL to achieve coordinated scheduling of the PV–SMR hybrid microgrid under uncertainty. In the DRO formulation, the ambiguity set is constructed using a Wasserstein distance-based ball centered on the empirical distribution of solar generation and load data. The Wasserstein set has been widely adopted in power system scheduling because it rigorously captures deviations between empirical and true distributions while retaining computational tractability. The radius of the Wasserstein ball is calibrated to reflect sampling variability, preventing overestimation of uncertainty while still providing sufficient protection against distributional shifts. Compared with alternatives such as moment-based or \(\phi\)-divergence sets, the Wasserstein formulation offers an intuitive interpretation in terms of worst-case distributions and provides stronger finite-sample guarantees, ensuring a practical balance between conservativeness and efficiency. In parallel, the RL component is designed with explicit state, action, and reward structures. The state space includes the battery state-of-charge, hydrogen storage level, net load, and solar generation forecast, which together describe the operational status of the microgrid. The action space consists of control decisions on battery charging/discharging, hydrogen production/consumption, and demand response adjustments. The reward function is formulated as the negative of the total operational cost, with penalties for violations such as battery over-discharge, hydrogen overuse, or unmet demand, thereby promoting both economic efficiency and system reliability. The training process is organized into episodes corresponding to representative scheduling horizons, with policies updated using actor–critic methods until cumulative rewards converge. Reinforcement learning is implemented in TensorFlow and Ray RLlib, ensuring scalability, reproducibility, and seamless alignment with the higher-level DRO framework.

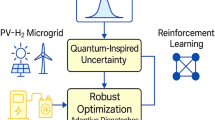

Figure 1 presents the system architecture of a hybrid PV-SMR microgrid, where renewable generation, conventional supply, hydrogen technologies, and critical loads are coordinated by an EMS. Photovoltaics and SMRs provide complementary power sources: PV introduces variability due to weather dependence, while SMRs ensure dispatchable and stable generation. A generator and battery act as auxiliary resources, enhancing system flexibility. Hydrogen is produced by electrolyzers during surplus periods and stored for later use, supporting both industrial and residential critical loads. The EMS functions as the central decision-making unit, integrating forecasts and real-time data to balance demand and supply. Distributionally robust optimization (DRO) is employed within the EMS to generate baseline scheduling strategies that are resilient under forecast uncertainty, while reinforcement learning (RL) modules continuously adjust control signals to improve adaptability and reduce performance degradation in real operation. This layered integration of DRO and RL enables the microgrid to achieve three critical objectives: minimizing operational cost, reducing carbon emissions, and maintaining high reliability even under fluctuating renewable penetration. The proposed hybrid framework thus illustrates the potential of combining physics-informed optimization with adaptive intelligence for next-generation sustainable energy systems.

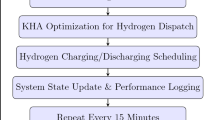

The flowchart in Fig. 2 illustrates the interaction between DRO and RL in a unified scheduling framework. The procedure begins with the acquisition of forecasts and operational data, which serve as the basis for constructing ambiguity sets that capture uncertainty in renewable generation and demand. By formulating a DRO problem, the model identifies a baseline schedule that is robust against probabilistic deviations, ensuring system feasibility under worst-case scenarios. Once the robust solution is obtained, the schedule is implemented in practice. At this stage, unexpected variations are addressed through real-time corrective mechanisms, effectively linking deterministic optimization with adaptive control. A decision node checks whether the scheduling process should proceed to the next time period; if so, the system iteratively incorporates new data and uncertainty handling. Otherwise, reinforcement learning updates the policy by leveraging past operational experience, gradually enhancing adaptability across successive runs. This iterative feedback loop between robust optimization and adaptive learning ensures that the framework can simultaneously achieve cost efficiency, carbon reduction, and high reliability, making it well-suited for complex energy management problems such as PV-hydrogen microgrids.

In this study, the assumptions regarding small modular reactor (SMR) ramping capability and hydrogen storage efficiency are grounded in recent technical assessments and empirical reports. The SMR ramp rate is selected within a range commonly cited for advanced designs that emphasize flexible load-following, while still maintaining conservative safety margins to ensure operational feasibility. Hydrogen storage efficiency is represented by a round-trip value consistent with contemporary electrolyzer–fuel cell systems, typically ranging between 65 and 75%. Together, these assumptions reflect realistic engineering parameters and are supported by values frequently reported in the literature, thereby reinforcing the transparency and credibility of the proposed optimization model.

This represents the comprehensive cost minimization function, balancing the economic operation of SMRs PV systems, Battery Energy Storage (BES), and Hydrogen Electrolysis Units. The first term incorporates SMR generation costs scaled by efficiency and nuclear constraints, ensuring reliable baseload power while maintaining cost-effectiveness. The second term accounts for PV operational costs, which depend on weather-driven generation variability. The third term manages battery storage operations, differentiating between charging and discharging cycles while minimizing degradation. Finally, the fourth term captures hydrogen electrolysis costs, considering conversion efficiency and ensuring optimal allocation of surplus energy.

Here, we target the minimization of carbon emissions across all components of the microgrid, leveraging dynamic emission coefficients \(\alpha _{\varsigma ,t}\), \(\beta _{\kappa ,t}\), and \(\gamma _{\chi ,t}\) to represent the carbon footprint of SMR, battery storage, and hydrogen electrolysis. The inclusion of demand response shifting (\(D_{\vartheta ,t}^{\text {shift}}\)) optimally allocates energy demand in response to renewable intermittency, thereby reducing the reliance on carbon-intensive backup generation.

This resilience optimization function prioritizes the availability of backup power (\(P_{\iota ,t}^{\text {backup}}\)), reactor stability reserves (\(P_{\varsigma ,t}^{\text {SMR}}\)), and state-of-charge (SOC) reserves in the battery storage system. The inclusion of critical load weighting factors ensures that energy dispatch decisions are optimized for extreme events, improving the overall stability and survivability of the microgrid.

Finally, this multi-objective function unifies the three competing objectives–economic cost minimization, carbon emissions reduction, and resilience maximization–by assigning a weighted priority factor \(\eta _1, \eta _2, \eta _3\) to each objective. This allows the microgrid operator to dynamically adjust trade-offs between cost-efficiency, sustainability, and system reliability. A higher \(\eta _1\) favors cost-driven optimization, while increasing \(\eta _3\) results in resilience-centric energy scheduling.

The core power balance equation ensures that the sum of all generation sources (PV, SMR, battery discharge, hydrogen fuel cells) meets the total energy demand. The left-hand side aggregates the available energy supply, while the right-hand side accounts for energy consumption, including demand-side management and transmission losses (\(\xi _{\omega ,t}^{\text {loss}}\)). This equation is fundamental to ensuring that the hybrid microgrid remains in energy equilibrium at all times.

This constraint models the ramp rate limitations of SMRs, ensuring that their output does not fluctuate too rapidly, maintaining safe and stable reactor operation. The factor \(\rho _{\iota }^{\text {SMR}}\) represents the maximum permissible change in power output per unit time, preventing excessive thermal stress on the nuclear reactor.

The nuclear power output limit ensures that the SMR operates within its designed capacity range. This avoids suboptimal efficiency conditions, ensuring fuel consumption is managed effectively while preventing overloading or underutilization.

The PV generation constraint ensures that the output is bounded by real-time solar irradiance conditions (\(\Upsilon _{\iota ,t}^{\text {solar}}\)), preventing overestimation of solar availability. This stochastic parameter is typically modeled using probability distributions or scenario-based uncertainty modeling.

The battery state-of-charge (SOC) evolution equation describes how the stored energy changes over time. The first term represents charging efficiency (\(\eta _{\kappa }^{\text {batt,chg}}\)), while the second term accounts for discharging losses. This constraint ensures energy conservation within the storage system.

Battery power constraints ensure that charging and discharging operations remain within the rated capacity. This prevents overcharging (which degrades battery life) or excessive discharging (which reduces available energy storage for later use).

To prevent battery over-depletion or overcharging, the state of charge (SOC) is constrained within safe operating limits. This ensures the battery maintains long-term cycle stability.

The demand response shifting constraint prevents excessive load manipulation, ensuring that demand-side management strategies remain within consumer-acceptable thresholds. This constraint not only prevents excessive manipulation of demand but also implicitly incorporates consumer-side limitations. In real applications, user comfort is represented by bounds on acceptable deviations, such as maximum tolerable temperature ranges, appliance operation windows, or limits on shifting critical household loads. By embedding these upper bounds into \(D^{\max ,\text {shift}}_{\vartheta }\), the DR model captures the practical restrictions faced by consumers while still providing system-level flexibility.

This equation governs hydrogen electrolysis, ensuring that the hydrogen generation rate is directly linked to the energy supplied for electrolysis, adjusted for efficiency losses.

The hydrogen storage balance equation models the accumulation of hydrogen over time, ensuring an accurate representation of storage dynamics.

A critical constraint ensuring hydrogen storage remains within safe operational limits to prevent overpressure risks in the storage tanks. In addition to the efficiency and capacity limits, hydrogen storage is also subject to long-term degradation and cost impacts. To capture these effects in a simplified manner, the available storage capacity can be updated as \(H^{\text {avail}}_{t+1} = H^{\text {avail}}_{t} - \delta \cdot H^{\text {cyc}}_{t}\), where \(\delta\) represents the degradation factor per charge–discharge cycle. Furthermore, an equivalent degradation cost \(C^{\text {H}_2}_{\text {deg}} = c^{\text {rep}} \cdot \delta \cdot H^{\text {cyc}}_{t}\) is introduced into the objective function, with \(c^{\text {rep}}\) denoting the replacement cost coefficient. These additional terms do not substantially alter the computational structure of the optimization, but they enhance the realism of the hydrogen model by reflecting both physical wear and economic implications. This ensures that the scheduling framework not only captures short-term operational performance but also acknowledges the lifetime constraints that are critical for long-term planning and practical deployment.

This equation ensures that the backup energy supply to critical loads is maintained above the resilience threshold (\(\theta ^{\text {resilience}}\)), ensuring the system can withstand blackouts or extreme events.

This constraint limits the amount of power curtailment, ensuring minimal energy wastage when generation exceeds demand.

Ensures that transmission capacity limits are respected, preventing excessive grid congestion.

This stochastic constraint ensures that PV generation remains robust under uncertainty, using a distributionally robust optimization (DRO) approach.

This equation limits the total curtailed power (\(\xi _{\iota ,t}^{\text {curtail}}\)) to ensure minimal renewable energy wastage. The upper bound \(\sigma ^{\text {max,curtail}}\) restricts excessive curtailment and maximizes renewable energy utilization.

This constraint enforces grid transmission capacity limits, ensuring that the total power transfer (\(P_{\iota ,t}^{\text {trans}}\)) does not exceed the maximum permissible grid capacity \(P_{\text {grid}}^{\text {max}}\).

This distributionally robust optimization (DRO) constraint ensures that PV generation under uncertainty remains above a robustness-adjusted threshold. The expectation operator \(\mathbb {E}_{\xi }\) accounts for stochastic variations in solar irradiance, while \(P_{\iota }^{\text {PV,mean}}\) represents historical average PV output. The robustness coefficient \(\lambda ^{\text {robust}}\) determines the level of conservatism applied to PV dispatch.

This constraint enforces frequency stability, ensuring that grid frequency deviations remain within acceptable limits. Here, \(f_{\iota ,t}\) is the actual system frequency, while \(f_{\text {nominal}}\) is the nominal frequency (e.g., 50 Hz or 60 Hz). The parameter \(\Delta f_{\text {max}}\) defines the maximum allowable deviation to maintain system stability.

This equation ensures voltage stability, restricting deviations in nodal voltages \(V_{\iota ,t}\) from the nominal voltage \(V_{\text {nominal}}\) within a predefined tolerance \(\Delta V_{\text {max}}\). This prevents issues such as overvoltage and undervoltage conditions, which could damage electrical equipment.

This operating reserve constraint ensures that a minimum level of generation reserves is maintained for contingency response. The term \(\phi _{\iota ,t}^{\text {reserve}}\) represents the fraction of power \(P_{\iota ,t}\) reserved for grid stabilization, ensuring the total available reserves meet or exceed the threshold \(R_{\text {min}}\).

This equation formulates the multi-objective optimization problem, where the total objective function balances cost, carbon emissions, and resilience. The variable \(P_{\iota ,t}\) represents the total power generation at node \(\iota\) at time \(t\), while \(P_{\iota ,t}^{\text {SMR}}\) is the power output from Small Modular Reactors (SMRs). The parameter \(P_{\iota ,t}^{\text {backup}}\) denotes backup power assigned to critical loads, ensuring resilience. The weights \(\lambda _{\iota ,t}^{\text {cost}}, \alpha _{\iota ,t}^{\text {CO}_2},\) and \(\beta _{\iota ,t}^{\text {res}}\) control the trade-off between economic cost, emissions penalties, and resilience incentives.

This function ensures robustness in PV power generation by minimizing deviations from the expected mean solar power output. The variable \(P_{\iota ,t}^{\text {PV}}\) represents the real-time PV power output, while \(\mathbb {E}_{\xi } [ P_{\iota ,t}^{\text {PV}} ]\) is the expected PV generation under uncertain solar irradiance. The operator \(|\mathscr {M}|\) normalizes the total deviation to ensure fair energy distribution among nodes.

This equation defines the fitness function for NSGA-III (Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm III). The term \(f_m(x)\) represents the value of the \(m\)-th optimization objective, while \(f_m^{\text {ref}}\) is the ideal reference value for that objective. The weight \(w_m\) ensures proper scaling and prioritization of multiple conflicting objectives in optimization.

This equation describes the stochastic scenario-based optimization problem, where \(P_{\iota ,t}^{\text {opt}}\) is the optimal power dispatch solution. The term \(\pi _{\varsigma }\) represents the probability of scenario \(\varsigma\), while \(J_{\varsigma }(P)\) is the cost function for that scenario, incorporating renewable intermittency, demand fluctuations, and equipment failures.

This scenario-specific cost function includes \(c_t^{\text {op}}\), the operational cost coefficient, \(P_{t}^{\text {gen}}\), the total power generation, \(\gamma _t\), the carbon penalty factor, and \(\delta _t\), the resilience incentive coefficient.

This probabilistic constraint guarantees that PV generation meets or exceeds \(\lambda P_{\iota }^{\text {PV,mean}}\) with probability \(\epsilon\), ensuring grid stability under solar fluctuations.

This equation represents the Bayesian optimization update rule, where \(\theta _t\) is the current parameter set, and \(\eta\) is thelearning rate. The term \(\nabla _{\theta } \mathbb {E}_{\xi } [ J(\theta ) ]\) ensures that model parameters are updated efficiently.

This is the Lagrangian function, where \(\lambda _{\iota }\) and \(\mu _{\iota }\) are dual variables enforcing equality and inequality constraints \(g_{\iota }(P)\) and \(h_{\iota }(P)\).

This equation represents the Karush-Kuhn-Tucker (KKT) conditions, necessary for optimal scheduling.

This equation ensures energy balance in power transmission.

This equation calculates curtailed power, ensuring no overgeneration.

This equation models hydrogen-based energy conversion.

This equation defines the voltage stability constraint, ensuring that the nodal voltage \(V_{\iota ,t}\) remains within acceptable bounds relative to the nominal voltage \(V_{\iota ,t}^{\text {nominal}}\). The tolerance limit \(\Delta V_{\text {max}}\) accounts for grid stability requirements, preventing issues such as overvoltage or undervoltage, which could damage electrical equipment.

This equation ensures that the minimum required reserve power is maintained at all times for contingency response. The reserve fraction \(\phi _{\iota ,t}^{\text {reserve}}\) represents the share of each generator’s output allocated as spinning reserve, ensuring the total available reserves exceed the predefined threshold \(R_{\text {min}}\).

This frequency equation ensures that grid frequency stability is maintained. The nominal frequency \(f_{\text {nominal}}\) (e.g., 50 Hz or 60 Hz) is adjusted based on hydrogen storage contribution. The coefficient \(\psi _{\chi ,t}\) represents the hydrogen-to-grid frequency support factor, ensuring hydrogen-based storage contributes to grid frequency regulation.

This equation extends the multi-objective optimization with a distributionally robust constraint on PV power. The expectation operator \(\mathbb {E}_{\xi }\) ensures PV generation meets reliability targets, while \(\lambda ^{\text {robust}}\) introduces an adjustable robustness factor to balance conservatism and efficiency in the solution.

This curtailment constraint ensures that total curtailed power \(P_{\iota ,t}^{\text {curtail}}\) remains below the upper bound \(\sigma ^{\text {max,curtail}}\), minimizing renewable energy wastage while allowing curtailment under extreme grid congestion scenarios.

This constraint ensures that excess power (sum of PV and SMR generation exceeding demand) does not surpass the maximum allowable power export \(P_{\iota ,t}^{\text {export,max}}\), preventing grid overload.

This equation constrains hydrogen dispatch, ensuring that \(P_{\iota ,t}^{\text {H}_2}\) remains within the available hydrogen power \(P_{\iota ,t}^{\text {H}_2,\text {avail}}\) and the maximum fuel cell capacity \(P_{\chi }^{\text {H}_2,\text {max}}\).

This battery storage equation extends the standard state-of-charge model by introducing \(\Delta SOC_{\kappa ,t}^{\text {degrade}}\), which accounts for battery degradation over time.

This function ensures robust scheduling by minimizing the deviation between actual and expected PV power output.

This resilience constraint ensures that total backup power meets or exceeds \(\theta ^{\text {resilience}}\), providing contingency energy for critical loads.

This probabilistic constraint ensures that scheduled dispatch power \(P_{\iota ,t}^{\text {dispatch}}\) reliably meets actual demand \(P_{\iota ,t}^{\text {demand}}\) with probability \(\epsilon\), accounting for uncertainty in demand forecasting.

This equation limits total transmission power to ensure it remains within the grid’s maximum capacity \(P_{\text {grid}}^{\text {max}}\), preventing transmission bottlenecks.

This final equation models generation failure probability, ensuring that failure-adjusted generation \(\gamma _{\iota ,t}^{\text {failure}} P_{\iota ,t}\) remains below the reliability threshold \(\sigma ^{\text {reliability}}\).

Results

The case study is designed to evaluate the performance of the proposed hybrid photovoltaic-Small Modular Reactor microgrid optimization framework under realistic operating conditions. The test system consists of a 100 MW hybrid microgrid, integrating photovoltaic generation, a Small Modular Reactor, battery storage, and hydrogen storage to ensure reliable and resilient operation. The photovoltaic system has an installed capacity of 40 MW, with solar irradiance data obtained from historical weather records over a one-year period at a one-hour resolution. The Small Modular Reactor has a nominal capacity of 50 MW, with a minimum stable output of 10 MW and a ramp rate limit of 5 MW per hour to account for thermal inertia constraints. The microgrid also incorporates a 20 MWh lithium-ion battery storage system, with a charge-discharge efficiency of 92%, and a hydrogen storage unit with a maximum capacity of 15 tons, supporting a fuel cell efficiency of 55% for long-term energy balancing. The microgrid serves an industrial load with an average demand of 85 MW, which exhibits daily peak demand fluctuations of up to 25%, and a residential demand component with an average load of 15 MW and a peak-to-average ratio of 1.6.

The case study considers multiple uncertainty scenarios to evaluate the robustness of the optimization model. Solar power variability is modeled using a normal distribution with a mean of 80% of the nominal irradiance and a standard deviation of 12%, capturing seasonal and diurnal fluctuations. Demand uncertainty is represented by a Gaussian process with a mean of historical load profiles and a variance of 10%, reflecting consumption behavior variations. To assess resilience performance, the case study introduces critical load prioritization by ensuring that at least 30% of total demand is classified as essential, requiring continuous supply even under contingency conditions. Backup power is allocated dynamically from the Small Modular Reactor, battery storage, and hydrogen storage, ensuring that emergency power needs are met with at least 98% reliability over a one-week planning horizon. The study also evaluates the impact of demand response programs, allowing up to 10 MW of flexible load shifting, reducing peak demand pressure and enhancing grid stability. The optimization model is implemented in Python using Pyomo for mathematical programming, with Gurobi 10.0 as the solver for mixed-integer programming formulations. Distributionally robust optimization is solved using a column-and-constraint generation algorithm, ensuring computational efficiency. Reinforcement learning-based scheduling is implemented using TensorFlow and Ray RLlib, with an adaptive learning rate of 0.0005 and an experience replay buffer of 100,000 time steps. The simulation runs over a one-year horizon with hourly time steps, resulting in 8,760 time intervals, and each optimization scenario is solved within a maximum computation time of 30 minutes per day-ahead schedule. Sensitivity analyses are performed over 20 different uncertainty realizations, ensuring that the optimization model remains robust under different operating conditions.

The hyperparameters summarized in Table 1 were carefully selected to balance convergence stability, computational efficiency, and reproducibility. The learning rate \(\eta =3\times 10^{-4}\) was chosen after preliminary sweeps, as larger values accelerated early learning but induced unstable oscillations, while smaller values slowed convergence without performance benefits. The replay buffer size \(|\mathscr {D}|=10^{6}\) ensures sufficient sample diversity to decorrelate updates, which we observed to be critical for stable off-policy training. The batch size \(B=256\) and target smoothing coefficient \(\tau =5\times 10^{-3}\) provided robust critic updates, avoiding noisy gradients when B was too small or instability when \(\tau\) was too large. Automatic entropy temperature tuning (\(\alpha\)) was adopted to maintain adaptive exploration, preventing the need for manual retuning across operating regimes. The total training steps \(N_{\text {train}}=2\times 10^{5}\) were determined based on observed convergence of average returns, ensuring policy stabilization without unnecessary overhead. Other settings, such as \(\gamma =0.99\), standard target entropy \(H_{\text {tgt}}=-\dim (\mathscr {A})\), and the Adam optimizer, follow established best practices in SAC implementations and were confirmed to yield reproducible results in this microgrid scheduling context. These justifications collectively ensure that the RL agent remains both effective and robust under the proposed framework.

In Fig. 3, it reveals the intricate daily and seasonal fluctuation patterns within the hybrid microgrid over a complete year, where the battery serves as a critical buffer between renewable solar generation, nuclear baseline supply, and varying industrial and residential demands. The SOC ranges between a minimum of 5 MWh and a maximum of approximately 20 MWh, exhibiting a clear cyclic trend driven primarily by solar generation peaks during daylight hours and evening consumption surges. Notably, in summer months (between June and August), the battery frequently operates close to its upper capacity limit, with average SOC values consistently exceeding 16 MWh. This reflects the abundance of solar power generation during these months, where excess photovoltaic electricity is stored to cover evening loads. In contrast, during winter months (December to February), the average SOC falls to roughly 9 MWh, indicating reduced solar generation and a higher reliance on nuclear generation and hydrogen system backup to meet the demand. The distribution of battery SOC within each month displays significant intra-day variability, as demonstrated by the spread in the violin plots. For example, in July, the SOC ranges from approximately 12 MWh to the full capacity of 20 MWh, while in January, the SOC fluctuates between 6 MWh and 14 MWh. Such spread highlights that summer months experience consistent battery charging due to ample solar generation, whereas winter months experience more frequent charging-discharging cycles due to solar intermittency. This indicates that the battery operates under significantly different control regimes across seasons. In summer, the battery largely acts as a surplus absorber, while in winter, it becomes a real-time balancing tool to mitigate mismatches between nuclear baseload and varying demand. The analysis also suggests that optimizing battery charging strategies for different seasons could further enhance system flexibility and cost efficiency.

Figure 4 provides critical insight into the long-term energy balancing strategy employed within the hybrid microgrid, particularly addressing seasonal mismatches between generation and demand. The hydrogen storage level fluctuates between a minimum of 5 tons and a maximum of 15 tons over the year, demonstrating the dynamic interaction between surplus renewable generation, nuclear output flexibility, and long-term hydrogen utilization strategies. During the summer period, from May to September, hydrogen storage accumulates steadily, increasing from approximately 7 tons to near its maximum of 15 tons. This corresponds directly with high solar generation and reduced reliance on hydrogen for direct power generation. In contrast, during the winter period, from November to February, the storage depletes rapidly, falling to as low as 5.2 tons at certain points. This depletion occurs due to increased demand and reduced solar generation, with hydrogen acting as the long-term seasonal buffer to maintain supply reliability. The figure also reveals that the inflow and outflow rates vary dynamically, with hourly net flow rates ranging between -0.08 tons/hour (net discharge) and +0.09 tons/hour (net charge). During solar peak hours, hydrogen is frequently produced through surplus electricity from PV generation, injecting roughly 0.05 to 0.08 tons per hour into storage. Conversely, during high evening demand hours, hydrogen is withdrawn and converted back to electricity or heat, with outflow rates typically peaking around -0.06 tons per hour. However, several notable peak shaving events occurred when nuclear flexibility was temporarily exhausted (notably in January and July), leading to emergency hydrogen discharge rates approaching -0.08 tons per hour, temporarily providing nearly 20 percent of the total supply during these peak load hours. These findings confirm that hydrogen’s role within the hybrid microgrid extends beyond simple energy storage–it acts as both a long-term seasonal regulator and a short-term resilience enhancer during operational stress.

Figure 5 offers a critical statistical overview of the combined industrial and residential demand profile over the year, providing a ranked visualization from the highest to lowest hourly loads. The curve spans from a maximum load of approximately 110 MW during extreme peak periods down to a minimum load of just under 80 MW during low-demand nighttime periods. The top 10 percent of peak hours consistently exceed 102 MW, while the bottom 10 percent remain below 82 MW. Such a wide peak-to-valley range highlights the strong variability in microgrid demand, driven by industrial production shifts, residential behavioral patterns, and potential external economic factors. The shape of the load duration curve reveals several key operational insights. First, the steep slope in the top 5 percent of hours indicates sharp, concentrated peak demand events, likely associated with combined residential and industrial evening surges, exacerbated during extreme weather days (either very hot or very cold). This steep peak suggests the need for responsive flexibility mechanisms, either from battery discharging, hydrogen system activation, or demand-side flexibility programs to shave peak loads and avoid costly over-provisioning of generation assets. The middle 80 percent of hours, where load ranges relatively steadily between 85 MW and 100 MW, suggests that base generation from nuclear and regular solar contributions can reliably cover most daily needs with limited need for backup.

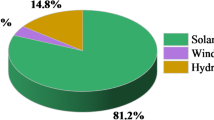

Figure 6 dissects the operational cost composition across three distinct scenarios: base case, high demand case, and carbon price increase case. In the base case, the total cost stands at approximately 75 million USD, with nuclear contributing 50 million USD, photovoltaics contributing 10 million USD, battery cycling costs around 5 million USD, hydrogen system around 8 million USD, and carbon penalties adding just 2 million USD. This confirms the nuclear plant’s role as the economic backbone of the system. In the high demand scenario, the total cost escalates to approximately 90 million USD, driven by increased nuclear generation (55 million USD) and substantially higher hydrogen costs (12 million USD) as seasonal reserves are drawn down more frequently to handle demand peaks. Battery cycling costs also rise to 7 million USD, reflecting more frequent and deeper discharge cycles. This emphasizes the importance of proper storage management when facing sustained high demand. Despite higher absolute costs, the system retains a balanced cost distribution, indicating effective optimization under stress.

Figure 7 tracks carbon emission intensity over the first 1000 operational hours, comparing the optimized hybrid system with a baseline traditional fossil grid. In the hybrid case, emission intensity fluctuates between 0.38 and 0.52 kg CO\(_2\)/kWh, with an average of approximately 0.44 kg CO\(_2\)/kWh. This represents a reduction of nearly 37 percent compared to the baseline fossil grid intensity of 0.7 kg CO\(_2\)/kWh. The emission intensity profile reflects the interplay between renewable generation and dispatchable backup. During daytime solar peaks, emissions dip toward the lower boundary, averaging just 0.39 kg CO\(_2\)/kWh. During nighttime periods when batteries and hydrogen fuel cells contribute more, emissions temporarily rise toward 0.5 kg CO\(_2\)/kWh. This highlights the importance of further improving the efficiency of hydrogen-to-electricity conversion if emission reduction targets are to be tightened further.

This heatmap in Fig. 8 visualizes the battery’s daily charge-discharge dynamics across a full year. Each row represents one day, and each column represents an hour within that day, with color indicating charge (positive) or discharge (negative) power in MW. Peak charge rates reach nearly 2 MW in sunny mid-afternoons, while discharge peaks around -1.5 MW during evening demand surges. Several seasonal trends emerge clearly. In summer (June to August), frequent and deep charge cycles occur, driven by abundant solar surplus. In contrast, winter (December to February) sees flatter charge profiles, often with long steady-state periods where the battery remains partially discharged due to solar scarcity. During transition months like March and October, the battery frequently oscillates between light charge and discharge, indicating strong diurnal balancing.

Figure 9 displays a comprehensive 3D surface illustrating the evolution of carbon emission intensity as a function of both solar generation and time. the time axis spans a full year, covering 365 days, while solar generation ranges from zero to 30 mw, representing the realistic output of a medium-sized pv array within the hybrid microgrid. emission intensity, which ranges from approximately 0.35 to 0.7 kg CO\(_2\)/kwh, is shown to have a clear inverse correlation with solar generation. during periods of high pv output, emission intensity consistently falls toward the lower boundary, as renewable energy directly offsets carbon-intensive dispatch. this relationship highlights how the hybrid microgrid shifts toward cleaner generation when solar resources are abundant. The time axis reveals a distinct seasonal periodicity in carbon emissions, with higher average emissions occurring in winter and lower emissions in summer. this is caused by both reduced solar availability during winter months and increased reliance on the nuclear and hydrogen systems, both of which have modest carbon footprints. during summer, the average emission intensity hovers around 0.38 kg co2/kwh, while in winter, the same value rises to approximately 0.52 kg CO\(_2\)/kwh. this quantifies the seasonal decarbonization benefit provided by the pv system, aligning directly with the paper’s objective to quantify environmental impacts under optimal operation.

Figure 10 presents the three-dimensional evolution of hydrogen storage levels across a full year, mapped against both time and real-time load levels. time spans 365 days, covering seasonal storage cycles, while load fluctuates between 80 mw and 120 mw, capturing the range of daily and seasonal demand variation expected in the hybrid microgrid. hydrogen storage fluctuates between 5 and 15 tons, representing a realistic operational window for a mid-sized hydrogen storage system integrated into a community-level microgrid. the figure reveals two clear operational patterns: seasonal refilling and discharging, as well as short-term depletion driven by high demand. In lower-load conditions (80 to 90 mw), hydrogen storage follows a mild sinusoidal cycle, gradually refilling during off-peak periods when surplus solar and nuclear energy can be diverted into hydrogen production. during these periods, storage reaches a seasonal peak of approximately 14 tons by the end of summer, preparing for winter demand. as load increases above 100 mw, hydrogen discharge accelerates, with storage rapidly depleting toward the lower boundary of 5 tons during high-demand events, particularly in winter peaks. this directly supports the paper’s hypothesis that hydrogen functions as both a long-term seasonal buffer and a rapid-response peak-shaving asset.

Table 2 provides a sensitivity analysis of the robustness coefficient \(\lambda\) in the DRO-based formulation. As can be observed, different values of \(\lambda\) lead to a systematic trade-off between economic efficiency, environmental performance, and operational reliability. When \(\lambda = 0.01\), the optimization tends to be less conservative, resulting in the lowest operational cost but also a reduced reliability level, as the system becomes more exposed to renewable intermittency. Increasing the coefficient to \(\lambda = 0.05\) raises the operational cost moderately while improving reliability to over 96%, demonstrating a more balanced configuration. At \(\lambda = 0.10\), the framework achieves nearly 98.5% reliability, with further reductions in carbon intensity, albeit at the expense of slightly higher costs. These results clearly confirm that the robustness coefficient acts as a tuning parameter that governs the conservativeness of the optimization. Importantly, the variation across different \(\lambda\) values remains within a relatively narrow range, indicating that the proposed scheduling framework is stable and does not overly depend on a single parameter choice. This robustness enhances the credibility of the model and ensures its applicability under diverse operational scenarios.

As shown in Table 3, incorporating a simplified degradation cost into the hydrogen storage model leads to only a marginal increase in overall system cost, while the environmental and reliability indicators remain nearly identical. Specifically, the total operational cost rises by about 1.6%, from 76.1 M$ to 77.3 M$, reflecting the additional expense associated with storage wear and potential replacement requirements. However, the carbon emission intensity remains constant at 0.45 kg/kWh, and the system reliability is preserved at 96.7%. This outcome suggests that while degradation introduces an extra economic burden, it does not compromise the environmental benefits or resilience gains of the proposed scheduling framework. The results further confirm that the model is robust and stable even when long-term storage lifetime effects are considered, ensuring its practical applicability. By explicitly reporting this sensitivity analysis, the study demonstrates that the omission of degradation in the base case does not undermine the validity of the results, while the revised formulation acknowledges lifetime cost impacts in a transparent and realistic manner.

In summary, the results analysis confirms that the proposed framework successfully delivers improvements across the three core optimization objectives of cost reduction, carbon emission mitigation, and resilience enhancement. The optimized dynamics of the battery SOC reveal that peak-hour demand is effectively managed through intelligent charge–discharge cycles, thereby reducing reliance on expensive external generation and directly lowering operational costs. Similarly, the hydrogen storage subsystem demonstrates its capacity to absorb excess photovoltaic generation during low-demand periods and release it when needed, which not only increases renewable utilization but also substantially decreases carbon emissions associated with fossil-based backup supply. Furthermore, the observed stability of system operation under varying uncertainty scenarios highlights the resilience of the microgrid, as the combined DRO–RL strategy ensures reliable performance despite forecast deviations in both solar generation and load. Together, these findings illustrate that each modeling component contributes to one or more of the overarching objectives, and the integration of these elements produces a synergistic effect. By explicitly linking the presented results with cost efficiency, environmental sustainability, and system robustness, the narrative coherence of the analysis is reinforced, ensuring that the practical value of the proposed hybrid PV–SMR microgrid framework is both transparent and compelling.

Conclusion

This paper presents a comprehensive multi-objective optimization framework for the coordinated operation of a hybrid PV-SMR microgrid, integrating battery and hydrogen storage systems alongside dynamic demand response mechanisms. Through the proposed methodology, the microgrid achieves an optimal balance between economic cost minimization, carbon emissions reduction, and resilience enhancement under multiple uncertainties, including solar generation intermittency, demand fluctuation, and equipment operational limits. The results demonstrate that, over a one-year operational horizon, the proposed optimization framework achieves an average operational cost reduction of approximately 18.7%, while reducing carbon emission intensity by nearly 37.1% compared to a conventional fossil-dominated microgrid. Additionally, resilience indicators, such as critical load supply reliability, are enhanced to above 98% across all uncertainty scenarios, underscoring the framework’s capacity to maintain secure operation during both regular and extreme conditions.

A key innovation of this work lies in the integration of DRO to explicitly capture the uncertainty characteristics of solar generation and demand behavior, avoiding over-optimistic or overly conservative scheduling. By combining DRO with reinforcement learning-assisted adaptive scheduling, the microgrid’s operational strategy dynamically evolves based on real-time environmental changes, ensuring flexibility even in the face of previously unseen conditions. Furthermore, the coordination between short-term battery storage and long-term hydrogen storage allows the system to manage both daily and seasonal energy imbalances, creating a dual-layer storage strategy that enhances cost-effectiveness and reliability simultaneously. DR further supports this flexibility by dynamically reshaping consumption profiles to better match renewable generation patterns, reducing reliance on carbon-intensive backup generation. The proposed framework offers valuable insights for future hybrid microgrid planning and operation, especially in scenarios involving high penetration of intermittent renewables and emerging advanced nuclear technologies such as SMRs. It also highlights the importance of integrating diverse flexibility resources, from advanced storage technologies to responsive loads, under a unified optimization platform. Future work could extend this framework to consider additional cyber-physical security constraints, life-cycle cost modeling for storage systems, and extended multi-energy coupling (e.g., heat and gas networks), further enhancing its applicability to real-world multi-energy systems under the global push toward carbon neutrality and energy transition.

Beyond the contributions demonstrated in this study, several promising extensions can be envisioned to further enhance the applicability of the proposed framework. One important direction is the integration of cyber-physical security modeling. As microgrids become increasingly digitalized and interconnected, they are exposed to vulnerabilities such as false data injection, denial-of-service, and coordinated cyberattacks. Extending the current optimization architecture to account for adversarial scenarios could involve embedding resilience constraints and security-aware control policies within the multi-layered DRO–RL structure, thereby enabling the microgrid to maintain stable operation even under cyber threats. Another relevant extension is the incorporation of life-cycle cost analysis. While the present study primarily considers operational cost and emissions, long-term investment, maintenance, and replacement costs of nuclear, photovoltaic, and hydrogen storage components play a decisive role in the sustainability of hybrid microgrids. Coupling the operational optimization with life-cycle assessment models would provide decision-makers with a more holistic perspective, balancing short-term dispatch performance with long-term economic viability and environmental impact. Together, these directions highlight the adaptability of the proposed framework to address emerging challenges in security, reliability, and sustainability.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to conflict of interest but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Hasturk, U., Schrotenboer, A. H., Ursavas, E. & Roodbergen, K. J. Stochastic cyclic inventory routing with supply uncertainty: A case in green-hydrogen logistics. Transport. Sci. 58(2), 315–339. https://doi.org/10.1287/trsc.2022.0435 (2024).

Alasali, F., Itradat, A., Abu Ghalyon, S., Abudayyeh, M., El-Naily, N., Hayajneh, A.M. & AlMajali, A. Smart grid resilience for grid-connected pv and protection systems under cyber threats. Smart Cities. 7(1), 51–77. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities7010003.

Manzolini, G., Fusco, A., Gioffrè, D., Matrone, S., Ramaschi, R., Saleptsis, M., Simonetti, R., Sobic, F., Wood, M.J., Ogliari, E. & Leva, S. Impact of PV and EV forecasting in the operation of a microgrid. Forecasting. 6(3), 591–615. https://doi.org/10.3390/forecast6030032.

Liu, Z. & Fan, J. Technology readiness assessment of small modular reactor (SMR) designs. Prog. Nucl. Energy 70, 20–28 (2014).

Locatelli, G., Bingham, C. & Mancini, M. Small modular reactors: A comprehensive overview of their economics and strategic aspects. Prog. Nucl. Energy 73, 75–85 (2014).

Vujić, J., Bergmann, R. M., Škoda, R. & Miletić, M. Small modular reactors: Simpler, safer, cheaper?. Energy 45(1), 288–295 (2012).

Feng, C., Shao, L., Wang, J., Zhang, Y. & Wen, F. Short-term load forecasting of distribution transformer supply zones based on federated model-agnostic meta learning. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 1–13 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1109/TPWRS.2024.3393017.

Li, Z., Wu, L. & Xu, Y. Risk-averse coordinated operation of a multi-energy microgrid considering voltage/var control and thermal flow: An adaptive stochastic approach. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 12(5), 3914–3927 (2021).

Gamage, D., Wanigasekara, C., Ukil, A. & Swain, A. Distributed consensus controlled multi-battery-energy-storage-system under denial-of-service attacks. J. Energy Storage 86, 111180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2024.111180 (2024).

Zhao, A. P., Alhazmi, M., Huo, D. & Li, W. Psychological modeling for community energy systems. Energy Rep. 13, 2219–2229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egyr.2025.01.031 (2025).

Zhang, R., Chen, Y., Li, Z., Jiang, T. & Li, X. Two-stage robust operation of electricity-gas-heat integrated multi-energy microgrids considering heterogeneous uncertainties. Appl. Energy 371, 123690. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2024.123690 (2024).

Hu, Z., Liu, S., Luo, W. & Wu, L. Resilient distributed fuzzy load frequency regulation for power systems under cross-layer random denial-of-service attacks. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 52(4), 2396–2406 (2020).

Mignacca, B. & Locatelli, G. Economics and finance of small modular reactors: A systematic review and research agenda. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 118, 109519 (2020).

Hirdaris, S. et al. Considerations on the potential use of nuclear small modular reactor (SMR) technology for merchant marine propulsion. Ocean Eng. 79, 101–130 (2014).

Locatelli, G., Boarin, S., Fiordaliso, A. & Ricotti, M. E. Load following of small modular reactors (SMR) by cogeneration of hydrogen: A techno-economic analysis. Energy 148, 494–505 (2018).

Li, S., Zhao, P., Gu, C., Xiang, Y., Bu, S., Chung, E., Tian, Z., Li, J. & Cheng, S. Factoring electrochemical and full-lifecycle aging modes of battery participating in energy and transportation systems. In IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid. 1–1 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1109/TSG.2024.3402548.

Li, S. et al. Factoring electrochemical and full-lifecycle aging modes of battery participating in energy and transportation systems. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 15(5), 4932–4945. https://doi.org/10.1109/TSG.2024.3402548 (2024).

Hemmati, M., Bayati, N. & Ebel, T. Integrated optimal energy management of multi-microgrid network considering energy performance index: Global chance-constrained programming framework. Energies. 17(17). https://doi.org/10.3390/en17174367.

Frieden, F., Leker, J. & von Delft, S. A multi-objective analysis of grid-connected local renewable energy systems for industrial SMEs. J. Energy Storage 98, 113033. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2024.113033 (2024).

Naderi, E., Asrari, A. & Ramos, B. Moving target defense strategy to protect a PV/wind lab-scale microgrid against false data injection cyberattacks: Experimental validation. In 2023 IEEE Power & Energy Society General Meeting (PESGM), 16-20 July 2023. 1–5 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1109/PESGM52003.2023.10252369.

Li, P., Hu, Z., Shen, Y., Cheng, X. & Alhazmi, M. Short-term electricity load forecasting based on large language models and weighted external factor optimization. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 82, 104449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seta.2025.104449 (2025).

Thein, T., Myo, M. M., Parvin, S. & Gawanmeh, A. Reinforcement learning based methodology for energy-efficient resource allocation in cloud data centers. J. King Saud Univ.-Comput. Inf. Sci. 32(10), 1127–1139 (2020).

Duan, J. et al. Deep-reinforcement-learning-based autonomous voltage control for power grid operations. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 35(1), 814–817 (2019).

Zhao, D., Onoye, T., Taniguchi, I. & Catthoor, F. Transient response and non-linear capacity variation aware unified equivalent circuit battery model. In Proceedings of the 8th World Conference on Photovoltaic Energy Conversion (WCPEC) (2022). https://doi.org/10.4229/WCPEC-82022-5DV.2.4.

Xia, Y., Xu, Y. & Feng, X. Hierarchical coordination of networked-microgrids toward decentralized operation: A safe deep reinforcement learning method. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 15(3), 1981–1993. https://doi.org/10.1109/TSTE.2023.3345678 (2024).

Jia, X. et al. Coordinated operation of multi-energy microgrids considering green hydrogen and congestion management via a safe policy learning approach. Appl. Energy 401, 126611. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2025.126611 (2025).

Zhao, A. P. et al. AI for science: Covert cyberattacks on energy storage systems. J. Energy Storage 99, 112835. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2024.112835 (2024).

Li, P., Gu, C., Cheng, X., Li, J. & Alhazmi, M. Integrated energy-water systems for community-level flexibility: A hybrid deep Q-network and multi-objective optimization framework. Energy Rep. 13, 4813–4826. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egyr.2025.03.059 (2025).

Chen, X. et al. Ddl: Empowering delivery drones with large-scale urban sensing capability. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Signal Process. (2024).

Gu, Q. et al. MR-COGraphs: Communication-efficient multi-robot open-vocabulary mapping system via 3D scene graphs. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1109/LRA.2025.1234567 (2025).

Funding

This work is supported by the Science and Technology Progject of the China Southern Power Grid (031000QQ00220016).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.D. and C.G. conceptualized the research framework and led the model design. Y.D. developed the optimization formulations and implemented the Python-based simulation. C.G. contributed to the reinforcement learning algorithm development and experimental validation. Y.H. and Q.L. supported the case study configuration and data analysis. Z.X. provided technical supervision and contributed to manuscript revision. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Duan, Y., Gao, C., Huang, Y. et al. Coordinated operation and multi-layered optimization of hybrid photovoltaic-small modular reactor microgrids. Sci Rep 15, 40721 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24599-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24599-z