Abstract

We conducted a nationwide, retrospective cohort study to quantify the risk of phenothiazine-associated retinopathy among new users of chlorpromazine (n = 35,955) and perphenazine (n = 224,790) in South Korea between January 1, 2015, and December 31, 2023. Adults without prior phenothiazine prescriptions or retinopathy who received at least one week of either drug were identified in the Health Insurance Review and Assessment database. We compared incidence rates of overall retinopathy, maculopathy, and pigmentary retinopathy/retinal degeneration before and after drug initiation, plotted cumulative incidence using Kaplan–Meier analyses, and used multivariable Cox regression to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) adjusted for age and sex. We also examined dose–response relationships across quartiles of cumulative exposure. By the end of follow-up, overall retinopathy and maculopathy occurred in 10.3% and 2.7% of chlorpromazine users and 19.5% and 6.2% of perphenazine users, respectively, with pigmentary retinopathy/retinal degeneration developed in 3.6% and 7.6%, respectively. Post- versus pre-exposure incidence rate ratios (IRRs) for overall retinopathy were 1.17 (95% CI 1.12–1.22) with chlorpromazine and 1.10 (95% CI 1.08–1.11) with perphenazine; IRRs for maculopathy were 1.18 (95% CI 1.08–1.29) and 1.11 (95% CI 1.08–1.14), indicating a modest increase in risk after initiation (all P < 0.05) Cumulative perphenazine exposure was associated with a slight increase in risk for pigmentary retinopathy/retinal degeneration (HR 1.06, 95% CI 1.02–1.11 in the highest quartile, P = 0.012), the highest chlorpromazine quartile showed reduced risks for overall retinopathy (HR 0.75, 95% CI 0.68–0.82), maculopathy (HR 0.53, 95% CI 0.44–0.63), and pigmentary retinopathy/retinal degeneration (HR 0.63, 95% CI 0.54–0.73; all P < 0.001). In multivariable models, perphenazine use (vs. chlorpromazine), older age, female sex, diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia were all significant predictors of the outcomes (all P < 0.05). These findings demonstrate that both drugs carry a modest risk of retinal toxicity—particularly perphenazine—and support the need for proactive ophthalmic screening in this population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Phenothiazines are a class of compounds first synthesized in the 1940s, characterized by a tricyclic structure combining two benzene rings and a central thiazine ring1. They are widely used as antipsychotic and antiemetic agents2,3. Key antipsychotic examples include chlorpromazine (used for schizophrenia and acute psychosis), perphenazine (used for both acute and maintenance therapy in schizophrenia), and thioridazine (often reserved for patients who do not tolerate or respond to other antipsychotics)2.

Phenothiazine-associated retinopathy is a severe and often irreversible ocular toxicity primarily linked to the antipsychotic agent thioridazine and, to a lesser extent, chlorpromazine3,4,5,6. This condition poses a significant threat to visual function, necessitating a comprehensive understanding of its underlying mechanisms, varied clinical presentation, and contemporary management strategies. It is characterized by damage predominantly to the outer retina and retinal pigment epithelium, leading to distinctive pigmentary changes and specific patterns of visual field defects4,7. Although the early stages are frequently asymptomatic, progression can lead to profound and irreversible central vision loss8. However, the true population-level burden of these adverse effects remains poorly characterized, and it is unclear whether phenothiazines other than thioridazine and chlorpromazine carry a similar risk profile. In light of these uncertainties and given that many patients requiring long-term antipsychotic therapy accumulate substantial phenothiazine exposure, the establishment of robust, real-world risk estimates is imperative.

By capturing real-world prescription records, diagnostic codes, and follow‐up data on millions of individuals, health claims databases allow the comprehensive evaluation of both incidence and temporal patterns of drug‐associated adverse events9. In South Korea, the Health Insurance Review and Assessment (HIRA) database encompasses virtually the entire (98%) population and includes detailed information on medication dispensations, comorbid diagnoses coded according to ICD‐10, and longitudinal follow‐up10. Leveraging this resource, it becomes possible to compare the rates of phenothiazine-induced retinopathy and maculopathy before versus after phenothiazine initiation, quantify cumulative incidences, and explore dose–response relationships.

In this study, we constructed a population-based cohort of phenothiazine users, specifically chlorpromazine and perphenazine users, using nationwide phenothiazine drug usage data. Our primary objectives were to quantify the risk of phenothiazine-associated retinopathy at the population level and identify the exposure-related factors that modulate this risk. By providing comprehensive real-world estimates, we aimed to determine the risk of phenothiazine-induced retinopathy and enhance clinician awareness of phenothiazine retinal toxicity. Understanding the risk of retinopathy helps balance the therapeutic benefits against vision-threatening adverse effects, especially in psychiatric patients requiring long-term therapy with high cumulative phenothiazine doses.

Methods

Participants

This nationwide, population-based, retrospective cohort study utilized the HIRA database of South Korea, which captures detailed information on the diagnoses, procedures, prescription records, visit dates, and demographic variables of approximately 50 million individuals. Disease codes in the HIRA are based on the Korean Standard Classification of Diseases (KCD) 8th revision (KCD-8), corresponding to the ICD-10 codes (Supplementary Table 1). Because HIRA captures health service utilization for nearly the entire South Korean population under the mandatory national insurance system, selection or volunteer bias is inherently minimized10. The database encompasses comprehensive data on drug exposures, longitudinal health outcomes, and potential confounding factors, making it a robust, nationwide, population-based resource that has been validated in numerous studies9,11,12,13,14.

From the HIRA claims, we identified all patients who received at least a 1-week prescription for phenothiazine prescription between January 1, 2012, and December 31, 2023. To ensure that the included individuals were incident users, defined as those first exposed during our study window, we excluded anyone with any phenothiazine claims prior to January 1, 2015. Specifically, patients with no phenothiazine prescriptions between January 1, 2012, and December 31, 2014, were assumed to be phenothiazine-naïve at the start of 2015 and thus characterized as “new users” from January 1, 2015, onward. This approach mirrors the methodologies employed in prior HIRA-based drug-toxicity studies11,12,13 and reflects long-term, continuous phenothiazine use for maintenance therapy in chronic psychiatric conditions3.

To avoid inclusion of preexisting retinopathy, we further excluded patients who underwent any fundus or macular evaluation, such as fundoscopy, optical coherence tomography, fundus autofluorescence, visual field testing, fluorescein angiography, or electroretinography— and were diagnosed with retinopathy (KCD-8/ICD-10 codes in Supplementary Table 1) before 2015. This step removed individuals with underlying retinopathy prior to 2015, while preserving the pre-phenothiazine baseline period, to calculate the pre-exposure risk of maculopathy and retinopathy between 2015 and 2023. We excluded patients treated with both chlorpromazine and perphenazine to avoid confounding, as well as those prescribed either drug for less than 1 week, ensuring that only individuals with at-risk exposure were included.

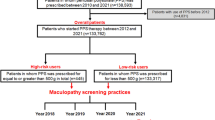

The study population after applying these inclusion and exclusion criteria is shown in Fig. 1. This study was performed in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Hanyang University Hospital (IRB File No. 2024–11-039). The need for informed consent was waived by the Institutional Review Board of Hanyang University Hospital because of the retrospective nature of the study and the use of deidentified data. The reporting adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines.

Definitions and evaluation

Currently, only three phenothiazine drugs, chlorpromazine, perphenazine, and levomepromazine, are available in the HIRA database. Some drugs, such as thioridazine, were withdrawn due to serious adverse effects (e.g., arrhythmia), while others are not reimbursed under Korea’s National Health Insurance and are thus classified as non-covered items without assigned drug codes in the HIRA database. Since chlorpromazine and perphenazine accounted for the vast majority of phenothiazine use in Korea among the three drugs available in the database (Supplementary Table 2), we selected these two as the study drugs. The date of the first prescription was defined as time zero for all time-to-event analyses in both the chlorpromazine and perphenazine groups. The cumulative dose was defined as the sum of all daily doses from the first prescription until an event (retinopathy) or censoring (end of follow-up). The duration of use (months) was determined by summing the days of supply from all prescriptions and converting the total to months.

Incident retinopathy was defined as the first appearance of KCD codes corresponding to overall retinopathy (Supplementary Table 1) in outpatient or inpatient claims. For each patient, the date of the first claim bearing any of the retinopathy codes after phenothiazine treatment initiation was considered the incident retinopathy date.

To calculate the pre-exposure retinopathy incidence, we defined the “before” period as the interval immediately preceding the first phenothiazine prescription (i.e., from January 1, 2015, to time zero—1). Any retinopathy event recorded during the window was counted based on the pre-exposure event rate. This allowed computation of incidence rate ratios (IRRs) comparing “before” versus “after” drug initiation (where the “after” period extended from time zero until retinopathy, censoring, or study end [December 31, 2023]).

Statistical analysis

We described the baseline demographics (age group and sex), primary indications for phenothiazine therapy (e.g., schizophrenia and bipolar disorder), and cumulative doses. Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation, and categorical variables as counts with percentages.

We generated Kaplan–Meier curves to estimate the cumulative incidence of retinopathy and maculopathy among phenothiazine users and to calculate person-year incidence rates for retinopathy and maculopathy before and after exposure. Multivariate Cox regression was performed to estimate the hazard ratios (HRs) for retinopathy and maculopathy after phenothiazine initiation, adjusting for age, sex, the phenothiazine drug used, duration of use, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia. All statistical tests were two-sided, with P < 0.05 indicating significance. Analyses were performed using the SAS Enterprise Guide 7.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Phenothiazine user distribution and selection of study drugs

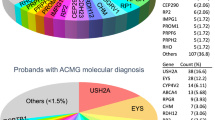

Supplementary Table 2 summarizes the nationwide number of phenothiazine users in the HIRA database over a 12-year period from January 2012 to December 2023, stratified by phenothiazine subclasses and individual drugs. Among the aliphatic phenothiazines, chlorpromazine was prescribed to 166,909 individuals, whereas levomepromazine was recorded for 10,761. Perphenazine, a piperazine phenothiazine, was the most commonly used overall, with 551,785 users nationwide. Table 1 presents the demographic and clinical characteristics of the 35,955 chlorpromazine users and 224,790 perphenazine users included in our analyses. The age-group distributions were similar between chlorpromazine and perphenazine users, except in those aged ≥ 60 years, who comprised 32.6% of the chlorpromazine cohort and 33.7% of the perphenazine cohort. Chlorpromazine users were predominantly male (61.1%), whereas perphenazine users were predominantly female (64.6%), showing a statistically significant difference (P < 0.001). Mood disorders predominated in both groups (60.6% chlorpromazine; 65.1% perphenazine), but schizophrenia, schizotypal, and delusional disorders were more common with chlorpromazine (37.8% vs. 9.9%), whereas anxiety, dissociative, stress-related, somatoform, and other nonpsychotic mental disorders were higher with perphenazine (64.9% vs. 38.3%). Chlorpromazine users had a mean duration of use of 12.2 ± 27.7 months with a mean daily dose of 90.2 ± 75.0 mg, whereas perphenazine users had 8.0 ± 17.8 months with a daily dose of 3.0 mg. Chlorpromazine and perphenazine users had comparable prevalences of diabetes mellitus (40.1% and 35.6%), hypertension (45.3% and 42.0%), and dyslipidemia (35.6% and 42.5%), although these differences were statistically significant (all P < 0.001).

Time-to-event analysis and cumulative incidences

Kaplan–Meier analysis (Fig. 2) showed a steady increase in retinopathy risk among chlorpromazine users, whereas perphenazine users had a steeper event rate, resulting in a higher cumulative incidence at equivalent times. Figure 3 shows the percentages of patients who developed overall retinopathy, maculopathy, and pigmentary retinopathy/retinal degeneration during the study period after the initiation of phenothiazine therapy. Among 35,955 chlorpromazine users, 3708 (10.3%) and 957 (2.7%) developed overall retinopathy and maculopathy, respectively. Among the 224,790 perphenazine users, 43,741 (19.5%) and 13,918 (6.2%) developed overall retinopathy and maculopathy, respectively. Pigmentary retinopathy/retinal degeneration was noted in 3.5% of chlorpromazine users and 7.9% of perphenazine users. These data highlight that perphenazine users showed higher cumulative incidences of overall retinopathy and its subtypes than chlorpromazine users.

The cumulative incidence estimates adjusted for age and sex at different intervals are presented in Table 2. At 6 months initiation, the cumulative incidences of retinopathy, maculopathy, and pigmentary retinopathy/retinal degeneration among chlorpromazine users were 1.7%, 0.4%, and 0.5%, respectively, whereas those were 2.5%, 0.6%, and 0.9%, respectively, among perphenazine users. By 1 year, cumulative incidence increased to 3.0%, 0.6%, and 0.8% in chlorpromazine users and 4.7%, 1.1%, and 1.6% in perphenazine users for overall retinopathy, maculopathy, and pigmentary retinopathy/retinal degeneration, respectively. Over the 5-year period, the cumulative incidences of overall retinopathy and maculopathy reached 17.3% and 4.4% in chlorpromazine and 35.3% and 9.9% in perphenazine users, respectively, whereas that of pigmentary retinopathy/retinal degeneration was 3.6% and 7.6% in chlorpromazine and perphenazine users, respectively.

Comparison between pre- and post-treatment risk of retinopathy

The rate of retinopathy after phenothiazine initiation was modestly higher than that during the pre-exposure period for both agents (Table 3). In chlorpromazine users, the incidence rates of overall retinopathy before and after its use were 0.32 and 0.38 per person-year, respectively, yielding an IRR of 1.17 (95% CI 1.12–1.22). The IRR of maculopathy and pigmentary retinopathy/retinal degeneration before and after its use were 1.18 (95% CI 1.08–1.29) and 1.13 (95% CI 1.05–1.22), respectively. In perphenazine users, the IRRs were 1.10 (95% CI 1.08–1.11) for overall retinopathy, 1.11 (95% CI 1.08–1.14) for maculopathy, and 1.11 (95% CI 1.08–1.14) for pigmentary retinopathy/retinal degeneration. Supplementary Table 3 presents the HRs after adjusting for age and sex, indicating that both chlorpromazine and perphenazine use were associated with an increased risk of retinopathy outcomes.

Dose–response relationship between phenothiazines exposure and adverse reactions

Figure 4 shows the adjusted ORs for overall retinopathy, maculopathy, and pigmentary retinopathy/retinal degeneration by quartile of cumulative exposure to chlorpromazine and perphenazine, using the lowest quartile as the reference. For chlorpromazine, the overall retinopathy risk decreased with increasing exposure: ORs were 0.88 (95% CI 0.81–0.96) in the second quartile, 0.74 (95% CI 0.67–0.81) in the third, and 0.75 (95% CI 0.68–0.82) in the fourth (P < 0.001). ORs for maculopathy and pigmentary retinopathy/retinal degeneration also declined across cumulative exposure quartiles: 0.74 (95% CI 0.63–0.87) and 0.79 (95% CI 0.68–0.91) in the second quartile; 0.51 (95% CI 0.43–0.62) and 0.64 (95% CI 0.54–0.74) in the third; and 0.53 (95% CI 0.44–0.63) and 0.63 (95% CI 0.54–0.73) in the fourth (both P < 0.001). However, perphenazine showed a modest trend toward higher odds ratios with increasing exposure for pigmentary retinopathy/retinal degeneration: OR 1.01 (95% CI 0.97–1.06) in the second quartile, 1.05 (95% CI 1.01–1.10) in the third, and 1.06 (95% CI 1.02–1.11) in the fourth (P = 0.012).

Multivariable analysis of factors associated with retinopathy and maculopathy

Table 4 summarizes the clinical factors associated with the risk of developing retinopathy, maculopathy, and pigmentary retinopathy/retinal degeneration using the Cox proportional hazards model. Chlorpromazine users had a significantly lower hazard of overall retinopathy than perphenazine users (HR, 0.53; 95% CI 0.51–0.55). The duration of phenothiazine use did not significantly affect the risk of overall retinopathy, maculopathy, or pigmentary retinopathy/retinal degeneration (all P > 0.05). Age was associated with a high risk for overall retinopathy (HR 1.08; 95% CI 1.07–1.09), pigmentary retinopathy/retinal degeneration (HR 1.34; 95% CI 1.32–1.37), and maculopathy (HR 1.66; 95% CI 1.63–1.69). Female sex, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia were also associated with increased risks for all outcomes (Table 4).

Discussion

This analysis revealed that among the phenothiazine antipsychotics prescribed in Korea from 2012 to 2023, chlorpromazine and perphenazine overwhelmingly accounted for nearly all usage for phenothiazine available in the HIRA database. Both chlorpromazine and perphenazine were associated with an increased risk of overall retinopathy, maculopathy, and pigmentary retinopathy/retinal degeneration after treatment, although perphenazine users exhibited higher cumulative incidences of these conditions than chlorpromazine. Multivariate analyses further identified perphenazine use, increasing age, female sex, and systemic comorbidities, such as DM, HTN, and hyperlipidemia, as significant risk factors for retinopathy outcomes.

By focusing on chlorpromazine and perphenazine, based on their nationwide use in Korea over the 12-year study period (Supplementary Table 2), we were able to capture a large cohort of users and conduct a real-world longitudinal analysis of retinopathy and maculopathy. However, despite their shared classification (phenothiazine), the chlorpromazine and perphenazine cohorts exhibited differences in demographic and clinical characteristics, which may reflect divergent prescription practices and underlying disease severities. Remarkably, chloropromazine users were predominantly male (61.1% vs. 35.4%), with a higher prevalence of schizophrenia-spectrum disorders (37.8% vs. 9.9%) and longer use (12.2 months vs. 8.0 months on average) than perphenazine users. In contrast, perphenazine was more frequently prescribed for anxiety, dissociation, stress-related, somatoform, and other nonpsychotic mental disorders (64.9% vs. 38.3%) in the predominantly female population. These baseline imbalances highlight the need for rigorous control of confounding factors, particularly sex and medical indications for phenothiazine prescriptions.

To address this, our study employed a self-controlled case-series (SCCS) design, which used each patient as their own control. This approach compared the pre- and post-exposure periods within the same individual, inherently accounting for time-invariant confounders and allowing a within-person assessment of the temporal association between phenothiazine initiation and retinopathy. For this analysis, we restricted the SCCS to individuals without prior retinal disease before 2015 and divided the observation window (2015–2023) into “before” and “after” exposure to directly estimate IRRs between the two periods. Our results showed increased IRRs for overall retinopathy, maculopathy, and pigmentary retinopathy/retinal degeneration in both chlorpromazine and perphenazine users.

However, in a nationally representative one million–person HIRA sample without phenothiazine exposure, the cumulative incidence of overall retinopathy was 2.2%, 3.7%, and 5.0% at 6 months, 1 year, and 5 years, respectively, whereas the cumulative incidence of maculopathy was 0.3%, 0.5%, and 3.1% over the same time points (Supplementary Table 4). These background estimates indicate that phenothiazine users, particularly those treated with perphenazine, exhibited a substantially higher cumulative incidence. However, direct statistical comparisons with the general population were not feasible because the data were derived from a separate HIRA database. Consequently, a head-to-head comparison with a matched non-user cohort was not possible, given the data extraction and analysis constraints. Future studies employing matched healthy controls are warranted to enable such comparisons and further contextualize the observed risks.

Our time-to-event analyses (Fig. 2) revealed a consistently increasing cumulative incidence, highlighting the gradual accumulation of phenothiazine-associated retinal toxicity. However, cumulative incidences differed markedly between chlorpromazine and perphenazine users. Chlorpromazine users experienced a smaller accrual of events, reaching a cumulative incidence of 10.3% at study end, whereas perphenazine users showed a steeper increase of 19.5% during the observation period. These differences suggest that even within the same pharmacological class, individual agents may vary in their retinal safety profiles, potentially reflecting differences in blood-retinal barrier penetration, metabolite formation, or retinal tissue affinity15.

The cumulative incidence and risk factor analyses align with chlorpromazine’s historical reputation as a relatively safer phenothiazine, whereas thioridazine, which has been largely withdrawn worldwide, is known for its high retinotoxic potential8. Although chlorpromazine, together with thioridazine, has long been recognized to cause retinal toxicity, chlorpromazine-associated retinopathy is uncommon and is generally reported only at very large doses, whereas perphenazine’s retinotoxic potential has been scarcely documented in the literature and is typically limited to isolated case reports or brief product-label mentions4,5,6,7. Previous case series and surveys of antipsychotic-treated patients have reported a substantially lower prevalence of retinal degenerative changes (e.g., approximately 4% in a recent cross-sectional series) than the 10–19% cumulative incidence we observed in our long-term phenothiazine cohorts4,5,6,7,16. Taken together, these findings indicate that phenothiazine exposure is associated with a substantial risk of retinopathy compared with other antipsychotics. Notably, perphenazine, a phenothiazine commonly used to treat diverse psychiatric diseases, has emerged as an important agent associated with retinal toxicity, demonstrating a steeper increase in the incidence of retinopathy that may exceed that observed with chlorpromazine.

Dose–response analyses yielded counterintuitive findings for chlorpromazine, wherein higher cumulative exposure quartiles were associated with lower ORs for retinopathy and maculopathy. This inverse association might reflect a depletion-of-susceptibles effect17,18, where patients inherently prone to retinal toxicity manifest changes early dose reductions or discontinuation, while long-term, high-exposure “survivors” represent those who tolerate the drug. Additional factors could include variation in monitoring intensity19, since surveillance is often most rigorous at treatment initiation given chlorpromazine’s well-known retinal risks. In contrast, the odds ratio of perphenazine maculopathy showed a modest upward trend with increasing exposure. These divergent patterns suggest that the dose-dependency of phenothiazine-induced retinal toxicity may be drug-specific, which warrants further investigation.

Our multivariate Cox models further reinforce the importance of drug- and patient-level modifiers of retinal risk. As suggested by the difference in the cumulative incidence of chlorpromazine and perphenazine, chlorpromazine with perphenazine as a reference was associated with a decreased risk of maculopathy (HR = 0.53). Age is an independent predictor of retinal toxicity, with older patients exhibiting increased susceptibility, which is also observed in other drug-induced retinopathies12,20, potentially reflecting cumulative age-related retinal thinning21 and neuronal loss interacting with phenothiazine toxicity. Female sex, diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia were all independently associated with a high risk of maculopathy and overall retinopathy, indicating synergistic effects between phenothiazine toxicity and underlying vascular or metabolic comorbidities or vulnerability to phenothiazine toxicity in patients with such conditions. These findings advocate personalized risk stratification and clinicians should consider baseline demographic and systemic risk factors when selecting antipsychotic regimens and determining screening intervals.

This study has some limitations that warrant consideration. First, our reliance on claims-based diagnostic codes may have underestimated retinopathy owing to unrecognized retinopathy. Further, we lacked access to medical records or imaging confirmation, which might have resulted in nonspecific retinopathy captured as phenothiazine-associated retinopathy. The reported cumulative incidences therefore reflect any recorded retinal or macular diagnosis in the database, rather than drug-specific toxicity, which could lead to an overestimation of phenothiazine-induced retinopathy and maculopathy. In this study, we adopted broader diagnostic categories to capture the full spectrum of phenothiazine-associated retinopathy, which remains poorly characterized, and clinicians may differ in their diagnostic labeling because of the limited awareness of its clinical patterns. However, analyses using more specific diagnostic codes for pigmentary retinopathy or retinal degeneration yielded lower incidence estimates—likely closer to the true toxicity rate—while maintaining the observed pattern of higher risk with perphenazine compared to chlorpromazine. Moreover, although the self-controlled case series design robustly adjusted for fixed confounders, time-varying covariates, such as changes in comorbid conditions or concurrent use of other potentially retinotoxic medications, which could not be controlled for in real-world studies, could still bias the risk estimates. Additionally, confounding by indication cannot be ruled out; patients with more severe psychiatric illness may receive higher chlorpromazine doses and have different healthcare utilization patterns that reduce ophthalmologic evaluations, leading to underdetection of retinopathy or maculopathy. Excluding medication users prior to 2015 may have influenced cohort definition by restricting the analysis to incident users from 2015 onward and, consequently, limiting the maximum follow-up period to 9 years. This restriction could affect the generalizability of our findings by excluding long-term users who initiated treatment before 2015. However, adopting the 2015 cutoff improved outcome ascertainment reliability because on January 1, 2015, HIRA introduced an OCT procedure code, which allowed us to confirm the capture of ophthalmic assessments (fundoscopy and OCT) used to diagnose retinopathy and maculopathy. Finally, only codes for three phenothiazine drugs, chlorpromazine, levomepromazine, and perphenazine, were available in the HIRA database, limiting the generalizability of our findings to other phenothiazine agents.

Despite these limitations, by demonstrating a significant increase in the risk of retinopathy after phenothiazine initiation and differences according to the drug, our findings support proactive ophthalmic surveillance in phenothiazine users, particularly those taking perphenazine. Future research should prioritize the integration of ophthalmic imaging data and testing to validate claims-based findings and standardized screening for early detection of retinal toxicity in phenothiazine users.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Cohen, B. M., Herschel, M. & Aoba, A. Neuroleptic, antimuscarinic, and antiadrenergic activity of chlorpromazine, thioridazine, and their metabolites. Psychiatry Res. 1, 199–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1781(79)90062-3 (1979).

Vital-Herne, J., Gerbino, L., Kay, S. R., Katz, I. R. & Opler, L. A. Mesoridazine and thioridazine: Clinical effects and blood levels in refractory schizophrenics. J. Clin. Psychiatry 47, 375–379 (1986).

Edinoff, A. N. et al. Phenothiazines and their evolving roles in clinical practice: A narrative review. Health Psychol. Res. 10, 38930. https://doi.org/10.52965/001c.38930 (2022).

Weekley, R. D., Potts, A. M., Reboton, J. & May, R. H. Pigmentary retinopathy in patients receiving high doses of a new phenothiazine. Arch. Ophthalmol. 64, 65–76. https://doi.org/10.1001/archopht.1960.01840010067005 (1960).

Mathalone, M. B. Ocular complications of phenothiazines. Trans. Ophthalmol. Soc. U K 1962(86), 77–88 (1966).

Tekell, J. L., Silva, J. A., Maas, J. A., Bowden, C. L. & Starck, T. Thioridazine-induced retinopathy. Am. J. Psychiatry 153, 1234–1235. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.153.9.1234b (1996).

Alkemade, P. P. Phenothiazine-retinopathy. Ophthalmologica 155, 70–76. https://doi.org/10.1159/000305340 (1968).

Somisetty, S., Santina, A., Sarraf, D. & Mieler, W. F. The impact of systemic medications on retinal function. Asia Pac. J. Ophthalmol. (Phila) 12, 115–157. https://doi.org/10.1097/APO.0000000000000605 (2023).

Ahn, S. J. Real-world research on retinal diseases using health claims database: A narrative review. Diagnostics https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14141568 (2024).

Kim, J. A., Yoon, S., Kim, L. Y. & Kim, D. S. Towards actualizing the value potential of Korea health insurance review and assessment (hira) data as a resource for health research: Strengths, limitations, applications, and strategies for optimal use of HIRA data. J. Korean Med. Sci. 32, 718–728. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2017.32.5.718 (2017).

Kim, J., Kwon, H. Y., Kim, J. H. & Ahn, S. J. Nationwide usage of pentosan polysulfate and practice patterns of pentosan polysulfate maculopathy screening in South Korea. Ophthalmol. Retina 8, 246–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oret.2023.10.005 (2024).

Kwon, H. Y., Kim, J. & Ahn, S. J. Drug exposure and risk factors of maculopathy in tamoxifen users. Sci. Rep. 14, 16792. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67670-x (2024).

Kwon, H. Y., Kim, J. & Ahn, S. J. Screening practices and risk assessment for maculopathy in pentosan polysulfate users across different exposure levels. Sci. Rep. 14, 11270. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-62041-y (2024).

Kim, H. K., Song, S. O., Noh, J., Jeong, I. K. & Lee, B. W. Data configuration and publication trends for the korean national health insurance and health insurance review & assessment database. Diabetes Metab. J. 44, 671–678. https://doi.org/10.4093/dmj.2020.0207 (2020).

Penha, F. M. et al. Retinal and ocular toxicity in ocular application of drugs and chemicals–part II: Retinal toxicity of current and new drugs. Ophthalmic. Res. 44, 205–224. https://doi.org/10.1159/000316695 (2010).

Balogun, M. M. & Coker, O. A. Ocular toxicity of psychotropic medications in a tertiary hospital in Lagos. Nigeria. Rom. J. Ophthalmol. 68, 99–107. https://doi.org/10.22336/rjo.2024.20 (2024).

Suissa, S. & Dell’Aniello, S. Time-related biases in pharmacoepidemiology. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 29, 1101–1110. https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.5083 (2020).

Moride, Y. & Abenhaim, L. Evidence of the depletion of susceptibles effect in non-experimental pharmacoepidemiologic research. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 47, 731–737. https://doi.org/10.1016/0895-4356(94)90170-8 (1994).

Hoffman, K. B., Dimbil, M., Erdman, C. B., Tatonetti, N. P. & Overstreet, B. M. The weber effect and the United States food and drug administration’s adverse event reporting system (FAERS): Analysis of sixty-two drugs approved from 2006 to 2010. Drug. Saf. 37, 283–294. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-014-0150-2 (2014).

Jorge, A. M. et al. Risk factors for hydroxychloroquine retinopathy and its subtypes. JAMA Netw. Open 7, e2410677. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.10677 (2024).

Alamouti, B. & Funk, J. Retinal thickness decreases with age: An OCT study. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 87, 899–901. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo.87.7.899 (2003).

Funding

This work was supported by National Research Foundation of Korea grants (NRF-RS-2025–00561352) funded by the Korean Government MSIT. Neither the sponsor nor the funding organization had any role in the design or conduct of this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors planned and designed the study. S.J.A. and J.K. wrote the main manuscript text, and prepared the figures. J.K. provided the data mining and statistical assistance. All authors acquired, analyzed and interpreted the data. J-E.C. did critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. S.J.A. obtained funding and supervised the study. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, J., Chung, JE. & Ahn, S.J. Nationwide health claims analysis of phenothiazine‐associated retinopathy risk in chlorpromazine and perphenazine users. Sci Rep 15, 40757 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24620-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24620-5