Abstract

The global increase in obesity is strongly associated with insulin resistance (IR) and related metabolic impairments. Asprosin (ASP), a glucogenic adipokine induced by fasting, has recently emerged as a potential biomarker of IR and abnormal body composition. However, its physiological role in obesity remains incompletely understood. To evaluate the associations between serum ASP levels, IR indices, oxidative stress markers (OS), liver function and inflammation parameters, and body composition in overweight and obese adults during a standardized 4-hour oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT). This cross-sectional study included 150 adults categorized by BMI into three groups: control (CG; BMI < 25 kg/m²), overweight (O1; BMI > 25 kg/m²), and obese (O2; BMI > 30 kg/m²). Participants underwent dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA), including visceral adipose tissue quantification, bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA), and biochemical assessment. Measurements included serum ASP, C-peptide, HbA1c, lipid profile, total oxidative capacity (TOC), total antioxidative capacity (TAC), liver transaminases (ALT, AST) and C-reactive protein (CRP). IR was assessed using HOMA-IR, QUICKI, Matsuda Index, TyG, and the composite TyG-WHR index as a proxy for hepatic IR. ASP levels were significantly higher in O1 and O2 compared with CG (p < 0.001), and in O2 compared with O1 (p < 0.01). ASP positively correlated with fat mass, TOC, HOMA-IR, TyG, TyG-WHR, ALT, and CRP, and negatively with muscle mass, total body water, resting metabolic rate, QUICKI, and Matsuda Index (p < 0.05). ASP is strongly associated with IR and adverse metabolic profiles in obesity. Its preferential correlation with hepatic IR markers (TyG-WHR, ALT, CRP) and fat mass suggests that ASP may primarily reflect liver-specific metabolic dysfunction rather than peripheral IR. These findings highlight ASP as a promising biomarker and potential therapeutic target in obesity-related metabolic disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Obesity, often termed the epidemic of the 21 st century, is a growing public health issue with rising prevalence and projections1,2,3. A key complication is insulin resistance (IR), a central factor in obesity-related cardiometabolic diseases4,5,6. The Homeostasis Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR) index, commonly used to assess IR, is linked to adipose tissue dysfunction, with abdominal fat contributing to elevated HOMA-IR values7,8,9. Visceral adiposity promotes IR via secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines and adipokines such as asprosin (ASP), disrupting insulin signaling10. Several IR markers based on biochemical and anthropometric data have been proposed11. Among these markers, the triglyceride-glucose index (TyG), calculated using fasting glucose and triglyceride levels, has emerged as a reliable, cost-effective biomarker for detecting IR12. It demonstrates superior sensitivity and specificity compared to conventional indices such as fasting insulin and HOMA-IR (7,13). Its strong correlation with the hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp, the gold standard for insulin sensitivity, underscores its clinical utility14,15,16. Other indices include QUICKI and the Matsuda Index, based on fasting or OGTT data17,18. However, no consensus exists on the most accurate index across populations. Therefore, composite indices integrating lipid–glucose interactions with anthropometric parameters have been proposed to improve detection of hepatic IR and related metabolic risk. Among these, the triglyceride–glucose waist-to-hip ratio (TyG-WHR) index, which combines the TyG index with central adiposity, has shown superior performance in identifying liver-related metabolic dysfunction and early steatosis compared with TyG alone19. Incorporating TyG-WHR into ASP research may therefore provide novel insight into whether this adipokine primarily reflects hepatic rather than peripheral IR.

ASP, a glucogenic adipokine secreted by white adipose tissue during fasting, regulates hepatic glucose release and may serve as a biomarker for IR and body composition10,20,21,22. Elevated ASP correlates with IR and is influenced by fat and lean mass, both of which modulate metabolic responses and may confound IR indices23,24,25. Integrating ASP with body composition measures may improve IR assessment. Existing literature remains inconclusive, necessitating further research on the interplay between ASP, IR, and body composition. Additionally, oxidative stress (OS) is increasingly linked to obesity, IR, and metabolic dysfunction26. Excess reactive oxygen species (ROS) promotes inflammation, insulin signaling impairment, and may enhance ASP expression, worsening metabolic outcomes27,28. Assessing OS markers alongside ASP, IR indices, and body composition could yield a more comprehensive view of metabolic health in obesity.

This study aims to evaluate ASP and OS parameters in overweight and obese individuals, focusing on muscle mass, fat mass, and resting metabolic rate (RMR). It also explores the association between ASP, OS, and IR, incorporating body composition as a confounding factor. Analyses were stratified by sex to capture potential differences. By simultaneously examining ASP levels, OS markers, and detailed body composition metrics, this research seeks to advance the understanding of obesity-related metabolic disturbances and support the development of more targeted and individualized therapeutic approaches.

Results

Biochemical profiling and measurement analysis

Glucose and insulin levels, both fasting and post-load, were elevated in the O1 group compared to controls, with further increases in the O2 group. C-peptide and HbA1c concentrations rose progressively with body mass (Table 1). All groups showed significant differences in anthropometric and body composition parameters, including BMI, fat and muscle mass, total body water (TBW), waist-to-hip ratio (WHR), VAT, adipose tissue %, RMR, and android/gynoid fat (p < 0.0001) (Table 3). Significant variations in IR indices (HOMA-IR, TyG, QUICKI-I, Matsuda-I) were also noted between groups (Table 1).

ASP levels were significantly elevated in O1 and O2 versus controls and differed between O1 and O2 (p < 0.0001). Oxidative status did not differ significantly between O1 and O2 (Table 2).

Although BMI did not differ between sexes, significant differences were observed in body composition (Table 4). Men had greater muscle mass, TBW, and RMR, whereas women exhibited higher fat mass, adipose tissue %, and gynoid fat (Table 3). In the O2 group, android fat differed significantly by sex (p < 0.0001). ASP levels were higher in women, reaching statistical significance in the O1 group only (p < 0.01) (Table 3).

Correlations

In the CG group, ASP positively correlated with fasting insulin, insulin at 60 and 120 min (OGTT), and TG levels (Table 4). In O1, ASP showed negative correlations with fasting glucose (R = − 0.23, p = 0.02), glucose at 60 min (R = − 0.23, p = 0.01), and 240 min (R = − 0.28, p = 0.0008). Positive correlations were observed with insulin at 120 min (R = 0.39, p < 0.001) and 180 min (R = 0.29, p = 0.008). In O2, ASP correlated positively with fasting insulin and insulin at 60 min post-glucose. In O1, ASP also showed a negative correlation with LDL and a positive one with HDL (Table 4). In CG, ASP correlated positively with gynoid fat and negatively with TBW and skeletal mass. In both O1 and O2, ASP correlated positively with body weight, adipose tissue %, total fat, and gynoid fat, and negatively with skeletal muscle mass, TBW, and RMR. Across all groups, ASP showed positive correlations with HOMA-IR and TyG, and negative correlations with QUICKI and Matsuda (Table 4).

In O1 and O2 groups, TOC showed moderate positive correlations with adipose tissue %, fat mass, gynoid fat, and ASP levels, and negative correlations with skeletal muscle mass, TBW, and RMR (Table 5). TAC was negatively correlated with adipose tissue % in both groups, and with fat and gynoid fat mass in O1. Positive correlations between TAC and skeletal muscle mass, TBW, RMR, and glucose at 60 min were observed in both groups. In O1, TAC also correlated positively with glucose at 240 min (R = 0.36, p < 0.05) (Table 5).

Discussion

Given the heterogeneity of previous findings, our study contributes to elucidating the potential role of ASP in metabolic dysfunction29. ASP, considered alongside measures of IR and body composition, shows potential as an early marker of metabolic dysregulation. In normal-weight subjects, it was positively linked to fasting and OGTT-induced insulin responses. Our results corroborate previous studies demonstrating elevated ASP levels in overweight and obese individuals (p < 0.0017, p < 0.0001; respectively)29,30,31. As fat tissue increases, significant relationships between ASP levels and body composition parameters emerge. Consistent with Suder A. et al. research, in our study ASP exhibited a positive correlation with increased body weight (p < 0.001), as well as adipose tissue percentage, total fat mass, and gynoid fat mass in both overweight and obese individuals (p < 0.001)32. These results support Cantay et al., who identified white adipose tissue adipocytes as the main source of ASP33. In normal-weight individuals, ASP correlated positively with gynoid fat mass and inversely with total body water and muscle mass, suggesting regional fat distribution influences ASP secretion independently of obesity. Reduced lean mass may indicate early metabolic impairment. Despite similar BMI, men and women showed distinct, sex-specific body composition patternsConsistent with literature data in our groups muscle mass was higher in men (CG: p < 0.003; O1: p < 0.0001; O2: p < 0.0001), while women had higher fat mass, % adipose tissue, and gynoid fat mass (CG: p < 0.05; O1: p < 0.0001; O2: p < 0.0001)34,35,36. Additionally, in the O2 group, statistically significant differences in android fat were noted between men and women (p < 0.0001), consistent with the research by Camilleri G. et al.37. In contrast to Mirr M. et al., although BMI was similar between men and women, we observed significantly higher ASP levels only in the overweight male group (p < 0.01)38. As noted by Li et al., ASP regulation may be modulated by sex hormones, potentially contributing to differences between men and women39. Although the study controlled for menstrual cycle phase and oral contraceptive use, the predominance of postmenopausal women suggests minimal hormonal influence. Despite similar BMI, variations in fat distribution and sex-specific features of white adipose tissue may underlie observed differences in ASP levels.Furthermore, we observed statistically significant differences in RMR between the O1 and O2 groups compared to healthy controls, as well as between the O1 and O2 groups themselves (p < 0.0001 for all comparisons). This is consistent with previous studies indicating that men typically have a higher RMR due to their greater muscle mass, which requires more energy to maintain40,41.

Beyond its association with traditional IR indices, asprosin also demonstrates significant relationships with markers of inflammation and liver function. These associations appear to vary across different metabolic states, suggesting that asprosin may reflect not only IR but also systemic inflammation and hepatic dysfunction. This aligns with previous findings indicating that ASP promotes hepatic glucose production and is linked to proinflammatory cytokine activation20,21. Taken together, these observations support the potential role of ASP as an integrated biomarker of obesity-related metabolic risk, encompassing endocrine, inflammatory, and hepatic components.

Contrary to earlier reports suggesting reduced ASP levels in advanced obesity due to inflammatory and hormonal dysregulation, our findings show consistent positive correlations of ASP with hepatic enzymes and inverse associations with CRP in overweight and obese, which reflects observations from recent studies linking ASP with liver injury, low-grade inflammation, and metabolic risk25,42,43, our findings demonstrate a positive association between ASP concentrations and increasing body mass and adiposity. Chen et al. suggested that mitochondrial dysfunction, common in obesity, may impair the physiological response to ASP and limit its role in energy metabolism44. In both O1 and O2 groups, ASP correlated negatively with skeletal muscle mass, TBW, and RMR, linking elevated ASP to greater adiposity and reduced lean mass. This supports evidence that excess adiposity promotes muscle loss and dehydration through inflammatory and hormonal pathways45. We also observed correlations between TOC, TAC, and metabolic parameters - ASP was positively associated with TOC, which in turn correlated with fat mass and gynoid fat mass, indicating links between ASP, OS, adiposity, and metabolic dysfunction28,46,47.Previous studies reported negative correlations between TAC and adiposity markers, suggesting reduced antioxidant defenses with greater fat mass due to chronic inflammation48. In contrast, our results showed positive associations of TAC with skeletal muscle mass, TBW, and RMR, supporting a protective role in maintaining lean mass and metabolic function. Although TAC did not correlate directly with ASP, it was positively linked to glucose levels in later OGTT stages, possibly reflecting enhanced glucose clearance during early metabolic disturbance. In obesity, persistent inflammation and OS may impair these defenses, driving further metabolic decline49Multiple studies have shown significant associations between ASP and IR markers in both diabetic and non-diabetic populations50,51,52. Our results reveal a heterogeneous relationship between ASP and IR indices, particularly the TyG index, across BMI groups, consistent with evidence highlighting TyG’s superiority over HOMA-IR in assessing IR7,13,53,54. In normal-BMI individuals, ASP correlated positively with HOMA-IR and negatively with QUICKI and Matsuda, supporting its link to IR, as also proposed by Rohoma et al.55. The positive association with TyG underscores ASP’s involvement in hepatic IR56,57,58. Similarly, Zhong et al. observed elevated ASP and correlations with TyG, though only in type 2 diabetes patients59.Our results extend this association to non-diabetic subjects. Nevertheless, in this study, ASP showed a negative correlation with fasting glucose as well as at 60 and 240 min during the OGTT in the O1 group. It also exhibited a positive correlation with fasting insulin and at 120 and 180 min in the O1 group, indicating its involvement in hyperinsulinemia associated with IR29,60,61. In overweight individuals, ASP was positively associated with hyperinsulinemia, supporting its role as both a marker and mediator of IR, with potential for antibody-based therapies62. In the O1 group, correlations between ASP and HOMA-IR, QUICKI, and Matsuda indices were attenuated, suggesting early alterations in metabolic regulation. By contrast, the stronger association with the TyG index indicated a persistent link to lipid metabolism and hepatic function, consistent with reports that advancing obesity shifts dysfunction from insulin sensitivity toward inflammation and lipid dysregulation63. In obese individuals, ASP correlated with fasting and 60-minute insulin, supporting a role in insulin secretion through increased glucose demand and feedback regulation64,65. Similar observations were made by Camilleri et al., who demonstrated in animal models that ASP initially enhanced insulin action and reduced resistance, but later acted as a pro-inflammatory mediator in adipose tissue, thereby exacerbating IR37,66. In the O2 group, the correlation between ASP and HOMA-IR weakens significantly, suggesting that the body may be developing resistance not only to insulin but also to the effects of ASP. This is consistent with the findings of Al-Sulaiti et al., who suggested that higher levels of ASP may be less effective in promoting insulin sensitivity in obesity due to metabolic adaptations and the presence of chronic low-grade inflammation67. However, the most notable finding in this group is the strongest correlation between ASP and TyG. Notably, in our cohort the correlation of ASP with the composite TyG-WHR index was stronger than with TyG alone, underscoring that ASP may preferentially mirror hepatic IR driven by central adiposity. In addition, we observed significant associations between ASP and liver transaminases as well as CRP. These findings suggest that circulating ASP not only reflects impaired lipid–glucose handling but also integrates signals of hepatic injury and systemic inflammation. Clinically, this combined profile is highly relevant, since patients with obesity are at increased risk of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and cardiometabolic complications, where hepatic IR, low-grade inflammation, and elevated liver enzymes often coexist. Thus, ASP’s parallel correlations with TyG-WHR, CRP, and transaminases strengthen its potential utility as a biomarker for liver-related metabolic dysfunction and may support its role in early risk stratification and therapeutic targeting. This suggests that, despite a weaker overall relationship with IR markers, ASP remains significantly involved in liver IR and dyslipidemia in individuals with obesity. This observation highlights the crucial role of ASP in metabolic dysfunction, particularly in obesity-related complications such as hypertriglyceridemia and fatty liver disease [68]. Our results suggest that TyG-WHR may serve as a more reliable indicator of liver-related IR in obese individuals, particularly when assessing ASP’s contribution to metabolic dysregulation. The stronger correlation between ASP and TyG and TyG-WHR in the O2 group suggests that, while ASP levels may be less effective at regulating insulin sensitivity, they still have a significant relationship with lipid metabolism and hepatic-related IR. This aligns with studies by Son et al., which found that TyG may better reflect IR in individuals with obesity than traditional markers like HOMA-IR13. Similarly, Kim et al. support the idea that the TyG index is particularly useful for assessing ASP’s impact on liver metabolism in obese populations, as it provides a comprehensive view of both glucose and lipid metabolism53. Clinically, the decreasing correlation between ASP and IR markers with increasing BMI suggests a diminished role of ASP in glucose and lipid regulation in advanced obesity. This may reflect metabolic adaptation and chronic low-grade inflammation. As such, ASP alone may have limited utility as a marker of IR in severe obesity. However, its consistent association with TyG highlights its potential relevance in targeting hepatic IR and dyslipidemia. To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate that asprosin is preferentially linked with hepatic IR markers, such as TyG-WHR and liver transaminases, rather than solely with peripheral insulin sensitivity, highlighting a novel mechanistic aspect of its role in obesity.

Conclusions

ASP is associated with key features of metabolic dysfunction, including increased adiposity, reduced muscle mass, and impaired insulin sensitivity. While correlated with traditional IR indices (HOMA-IR, QUICKI, Matsuda) and with the proposed composite marker TyG-WHR, these associations weakened in obesity, suggesting possible ASP resistance. In contrast, its strong correlation with the TyG and TyG-WHR index across BMI groups points to a role in hepatic IR. Associations with OS markers further support a link between metabolic inflammation and endocrine function. ASP may thus serve as a relevant marker of liver-specific metabolic impairment in obesity, warranting further investigation.

Materials and methods

Study design

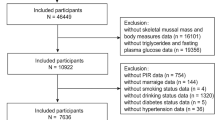

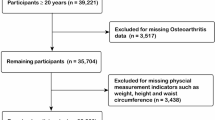

This study recruited a total of 150 participants, divided into three groups: 50 individuals with obesity (BMI > 30 kg/m²) (O2), 50 overweight individuals (BMI > 25 kg/m²) (O1), and 50 healthy volunteers with a BMI below 25 kg/m² (CG). Anthropometric measurements, including height and weight, were carefully taken using standardized instruments to ensure precision and accuracy. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as the ratio of body weight (in kilograms) to the square of height (in meters squared). To further assess metabolic function, all participants underwent an OGTT, with glucose and insulin levels measured at specified intervals: 0, 60, 120, 180, and 240 min. The samples and controls were analyzed using the blind analysis method in a single run to eliminate bias. Glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) was measured using the Bio-Rad D10 dual HbA2/F/A1c platform, employing the CE-HPLC method for high accuracy.

Body composition was assessed using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) (Lunar iDXA (GE Healthcare, Chicago, USA). Participants were non-smokers, abstinent from alcohol abuse, and free from medications (e.g., hypoglycemics, immunosuppressants) or conditions affecting oxidative stress. Eligibility was confirmed through medical history, physical examination, and documentation review. Venous blood (5.5 mL) was collected, centrifuged, and serum was aliquoted and stored at − 80 °C. The procedures were approved by the Local Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Bialystok, Poland, and written informed consent was obtained from each participant (APK.002.364.2021). All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Chemical identity

Oxidative status was evaluated by measuring total oxidative capacity (TOC) and total antioxidant capacity (TAC) using a photometric assay (PerOx TOS/TAC kit; KC5100, Germany). ASP levels were determined by ELISA (Cloud-Clone Corp., SEA332Hu). Glucose, total cholesterol (CHOL), high density cholesterol (HDL), low density cholesterol (LDL), and triglycerides (TG) were measured via enzymatic colorimetric methods (Roche C111, Switzerland). Insulin and C-peptide were assessed using electrochemiluminescence (ECLIA; Roche E411, UK), while glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) was analyzed via CE-HPLC (Bio-Rad D10 platform). All samples and controls were processed blindly in a single run to reduce bias.

IR indices were calculated as follows:

HOMA-IR = fasting glucose (mmol/l)×fasting insulin (µU/mL)/22.5.

TyG index = ln (fasting triglycerides [mg/dl]×fasting glucose [mg/dl])/2.

QUICKI Index = 1/(log(fasting insulin (µU/mL)) + log(fasting glucose (mg/dL)).

Matsuda Index = 10,000/(fasting glucose(mg/dL)×fasting insulin(µU/mL))×(glucose (mg/dL) at 120 min×insulin (µU/mL) at 120 min)

TyG-WHR index = ln (fasting triglycerides [mg/dl]×fasting glucose [mg/dl])/2 x WHR (cm)

Bioelectrical impedance analysis

The Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis (BIA) method was employed to assess body composition using the medical body analyzer INBODY 220 (Biospace, Korea). This device enables the measurement of body mass, total body water (TBW), fat mass, skeletal muscle mass, BMI and RMR.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 9.0. As data were not normally distributed (Shapiro–Wilk test), nonparametric tests were used. The Mann–Whitney (**) and Kruskal–Wallis (*) tests assessed inter-group differences (p < 0.05). Spearman correlation was applied to evaluate relationships between variables.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- IR:

-

Insulin resistance

- HOMA-IR:

-

Homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance

- TyG:

-

Triglyceride-glucose index

- TyG-WHR:

-

Triglyceride-glucose-waist-hip ratio

- QUICKI:

-

Quantitative insulin sensitivity check index

- OGTT:

-

Oral Glucose Tolerance Test

- ASP:

-

Asprosin

- OS:

-

Oxidative stress

- TOC:

-

Total oxidative capacity

- TAC:

-

Total antioxidant capacity

- ROS:

-

Reactive oxygen species

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- TBW:

-

Total body water

- RMR:

-

Resting metabolic rate

- CHOL:

-

Total cholesterol

- HDL:

-

High density lipoprotein

- LDL:

-

Low density lipoprotein

- TG:

-

Triglycerides

- HbA1c:

-

Glycated hemoglobin

- CG:

-

Control group

- O1:

-

Overweight group

- O2:

-

Obese group’

- VAT:

-

Visceral adipose tissue

- BIA:

-

Bioelectrical impedance analysis

- DXA:

-

Dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry

References

Lingvay, I., Cohen, R. V., Roux, C. W. L. & Sumithran, P. Obesity in adults. Lancet (London Engl. 404 (10456), 10456:972–987. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(24)01210-8 (2024).

Sumińska, M. et al. Historical and cultural aspects of obesity: from a symbol of wealth and prosperity to the epidemic of the 21st century. Obes. Reviews: Official J. Int. Association Study Obes. 23 (6), e13440. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.13440 (2022).

Kosmas, C. E. et al. Insulin resistance and cardiovascular disease. J. Int. Med. Res. 51 (3), 3000605231164548. https://doi.org/10.1177/03000605231164548 (2023).

Petersen, M. C. et al. Cardiometabolic characteristics of people with metabolically healthy and unhealthy obesity. Cell Metabol. 36 (4), 745–761e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2024.03.002 (2024).

Vigna, L. et al. Insulin resistance and cardiometabolic indexes: comparison of concordance in working-age subjects with overweight and obesity. Endocrine 77 (2), 231–241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12020-022-03087-8 (2022).

Tahapary, D. L. et al. Challenges in the diagnosis of insulin resistance: focusing on the role of HOMA-IR and Tryglyceride/glucose index. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 16 (8), 102581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsx.2022.102581 (2022).

Zhang, M., Hu, T., Zhang, S. & Zhou, L. Associations of different adipose tissue depots with insulin resistance: A systematic review and Meta-analysis of observational studies. Sci. Rep. 5, 18495. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep18495 (2015).

Yuan, M. et al. A novel player in metabolic diseases. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 11, 64. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2020.00064 (2020). Published 2020 Feb 19.

Muthu, M. L. & Reinhardt, D. P. Fibrillin-1 and fibrillin-1-derived Asprosin in adipose tissue function and metabolic disorders. J. Cell. Commun. Signal. 14 (2), 159–173. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12079-020-00566-3 (2020).

Jog, K. S., Eagappan, S., Santharam, R. K. & Subbiah, S. Comparison of novel biomarkers of insulin resistance with homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance, its correlation to metabolic syndrome in South Indian population and proposition of population specific cutoffs for these indices. Cureus 15 (1), e33653. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.33653 (2023).

Brito, A. D. M. et al. Predictive capacity of triglyceride-glucose (TyG) index for insulin resistance and cardiometabolic risk in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 61 (16), 2783–2792. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2020.1788501 (2021).

Son, D. H., Lee, H. S., Lee, Y. J., Lee, J. H. & Han, J. H. Comparison of triglyceride-glucose index and HOMA-IR for predicting prevalence and incidence of metabolic syndrome. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 32 (3), 596–604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2021.11.017 (2022).

Sánchez-García, A. et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the triglyceride and glucose index for insulin resistance: A systematic review. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2020 (4678526). https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/4678526 (2020).

Mohd Nor, N. S., Lee, S., Bacha, F., Tfayli, H. & Arslanian, S. Triglyceride glucose index as a surrogate measure of insulin sensitivity in obese adolescents with normoglycemia, prediabetes, and type 2 diabetes mellitus: comparison with the hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp. Pediatr. Diabetes. 17 (6), 458–465. https://doi.org/10.1111/pedi.12303 (2016).

Matsuda, M. & DeFronzo, R. A. Insulin sensitivity indices obtained from oral glucose tolerance testing: comparison with the euglycemic insulin clamp. Diabetes Care. 22 (9), 1462–1470. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.22.9.1462 (1999).

Rani, K., Patil, P., Bharti, P., Kumar, S. & Prabhala The undervalued league of insulin resistance testing: Uncovering their importance. Horm. Mol. Biol. Clin. Investig. https://doi.org/10.1515/hmbci-2023-0061 (2024).

Placzkowska, S., Pawlik-Sobecka, L., Kokot, I. & Piwowar, A. Indirect insulin resistance detection: current clinical trends and laboratory limitations. Biomed. Pap Med. Fac. Univ. Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 163 (3), 187–199. https://doi.org/10.5507/bp.2019.021 (2019).

Katz, A. et al. Quantitative insulin sensitivity check index: a simple, accurate method for assessing insulin sensitivity in humans. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 85 (7), 2402–2410. https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem.85.7.6661 (2000).

Tang, X., Zhang, K. & He, R. The association of triglyceride-glucose and triglyceride-glucose related indices with the risk of heart disease in a national. Cardiovasc Diabetol. ;24(1):54. (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-025-02621-y. Erratum in: Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2025;24(1):174. doi: 10.1186/s12933-025-02726-4.

Wang, M. et al. Serum Asprosin concentrations are increased and associated with insulin resistance in children with obesity. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 75 (4), 205–212. https://doi.org/10.1159/000503808 (2019).

Romere, C. et al. Asprosin, a Fasting-Induced glucogenic protein hormone. Cell 165 (3), 566–579. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2016.02.063 (2016).

Jahangiri, M., Shahrbanian, S. & Hackney, A. C. Changes in the level of Asprosin as a novel adipocytokine after different types of resistance training. J. Chem. Health Risks. 11 (Spec Issue), 179–188 (2021).

Ugur, K. et al. Asprosin, visfatin and subfatin as new biomarkers of obesity and metabolic syndrome. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 26 (6), 2124–2133. https://doi.org/10.26355/eurrev_202203_28360 (2022).

Kim, S. H., Kim, S. E. & Chun, Y. H. The association of plasma Asprosin with anthropometric and metabolic parameters in Korean children and adolescents. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 15, 1452277. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2024.1452277 (2024).

Masenga, S. K., Kabwe, L. S., Chakulya, M. & Kirabo, A. Mechanisms of oxidative stress in metabolic syndrome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24 (9), 7898. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24097898 (2023).

Corkey, B. E. Reactive oxygen species: role in obesity and mitochondrial energy efficiency. Philos. Trans. R Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 378 (1885), 20220210. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2022.0210 (2023).

Senyigit, A., Durmus, S., Gelisgen, R. & Uzun, H. Oxidative stress and Asprosin levels in type 2 diabetic patients with good and poor glycemic control. Biomolecules 14 (9), 1123. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom14091123 (2024).

Corica, D. et al. Asprosin serum levels and glucose homeostasis in children with obesity. Cytokine 142, 155477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cyto.2021.155477 (2021).

Zhang, Y., Zhang, Y., Yang, B., Li, S. & Jia, R. Circulating levels of Asprosin in children with obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Endocr. Disord. 24 (1), 36. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-024-01565-w (2024).

Hu, G., Si, W., Zhang, Q. & Lv, F. Circulating asprosin, irisin, and abdominal obesity in Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a case-control study. Endokrynol Pol. 74 (1), 55–62. https://doi.org/10.5603/EP.a2022.0093 (2023).

Suder, A. et al. Exercise-induced effects on Asprosin and indices of atherogenicity and insulin resistance in males with metabolic syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 985. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-51473-1 (2024).

Cantay, H., Binnetoglu, K., Gul, H. F. & Bingol, S. A. Investigation of serum and adipose tissue levels of Asprosin in patients with severe obesity undergoing sleeve gastrectomy. Obes. (Silver Spring). 30 (8), 1639–1646. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.23471 (2022).

Zaki, M., Amin, D. & Mohamed, R. Body composition, phenotype and central obesity indices in Egyptian women with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Complement. Integr. Med. 18 (2), 385–390. https://doi.org/10.1515/jcim-2020-0073 (2020).

Gažarová, M., Bihari, M., Lorková, M., Lenártová, P. & Habánová, M. The use of different anthropometric indices to assess the body composition of young women in relation to the incidence of Obesity, sarcopenia and the premature mortality risk. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19 (19), 12449. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912449 (2022).

Jensen, B. et al. Limitations of Fat-Free mass for the assessment of muscle mass in obesity. Obes. Facts. 12 (3), 307–315. https://doi.org/10.1159/000499607 (2019).

Camilleri, G. et al. Genetics of fat deposition. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 25 (1 Suppl), 14–22. https://doi.org/10.26355/eurrev_202112_27329 (2021).

Mirr, M. et al. Serum Asprosin correlates with indirect insulin resistance indices. Biomedicines 11 (6), 1568. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines11061568 (2023). Published 2023 May 28.

Li, X. et al. Plasma Asprosin levels are associated with glucose Metabolism, Lipid, and sex hormone profiles in females with Metabolic-Related diseases. Mediators Inflamm. 2018, 7375294. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/7375294 (2018).

Zurlo, F., Larson, K., Bogardus, C. & Ravussin, E. Skeletal muscle metabolism is a major determinant of resting energy expenditure. J. Clin. Invest. 86 (5), 1423–1427. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI114857 (1990).

Gitsi, E., Kokkinos, A., Konstantinidou, S. K., Livadas, S. & Argyrakopoulou, G. The relationship between resting metabolic rate and body composition in people living with overweight and obesity. J. Clin. Med. 13 (19), 5862. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13195862 (2024).

Zheng, F. et al. Intervention of Asprosin attenuates oxidative stress and Neointima formation in vascular injury. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 41 (7–9), 488–504. https://doi.org/10.1089/ars.2023.0383 (2024).

Pérez-López, F. R. et al. Asprosin levels in women with and without the polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 39 (1), 2152790. https://doi.org/10.1080/09513590.2022.2152790 (2023).

Chen, S. et al. Asprosin contributes to pathogenesis of obesity by adipocyte mitophagy induction to inhibit white adipose Browning in mice. Int. J. Obes. (Lond). 48 (7), 913–922. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-024-01495-6 (2024).

Huang, R. et al. A cross-sectional comparative study on the effects of body mass index and exercise/sedentary on serum Asprosin in male college students. PLoS One. 17 (4), e0265645. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0265645 (2022).

Kantorowicz, M. et al. Nordic walking at maximal fat oxidation intensity decreases Circulating Asprosin and visceral obesity in women with metabolic disorders. Front. Physiol. 12, 726783. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2021.726783 (2021).

Cui, J. et al. Association of serum Asprosin with metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease in older adult type 2 diabetic patients: a cross-sectional study. BMC Endocr. Disord. 24 (1), 27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-024-01560-1 (2024). Published 2024 Mar 4.

Farhangi, M. A., Vajdi, M. & Fathollahi, P. Dietary total antioxidant capacity (TAC), general and central obesity indices and serum lipids among adults: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 92 (5–6), 406–422. https://doi.org/10.1024/0300-9831/a000675 (2022).

Silvestrini, A., Meucci, E., Ricerca, B. M. & Mancini, A. Total antioxidant capacity: biochemical aspects and clinical significance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24 (13), 10978. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms241310978 (2023).

Hong, T. et al. High serum Asprosin levels are associated with presence of metabolic syndrome. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2021 (6622129). https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6622129 (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. Plasma Asprosin Concentrations Are Increased in Individuals with Glucose Dysregulation and Correlated with Insulin Resistance and First-Phase Insulin Secretion. Mediators Inflamm. :9471583. (2018). https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/9471583 (2018).

Deng, X. et al. Association between Circulating Asprosin levels and carotid atherosclerotic plaque in patients with type 2 diabetes. Clin. Biochem. 109–110, 44–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2022.04.01 (2022).

Kim, B., Kim, G. M., Huh, U., Lee, J. & Kim, E. Association of HOMA-IR versus TyG index with diabetes in individuals without underweight or obesity. Healthc. (Basel). 12 (23), 2458. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12232458 (2024).

Ozturk, D., Sivaslioglu, A., Bulus, H. & Ozturk, B. TyG index is positively associated with HOMA-IR in cholelithiasis patients with insulin resistance: based on a retrospective observational study. Asian J. Surg. 47 (6), 2579–2583. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asjsur.2024.03.004 (2024).

Rohoma, K. H., Abdellrahim, A. A., Abo Elwafa, R. A. & Moawad, M. G. Study of the relationship between serum asprosin, endothelial dysfunction and insulin resistance. Clin. Diabetol. 11 (2), 73–79. https://doi.org/10.5603/DK.a2022.0006 (2022).

Ramdas Nayak, V. K., Satheesh, P., Shenoy, M. T. & Kalra, S. Triglyceride glucose (TyG) index: A surrogate biomarker of insulin resistance. J. Pak Med. Assoc. 72 (5), 986–988. https://doi.org/10.47391/JPMA.22-63 (2022).

Xue, Y., Xu, J., Li, M. & Gao, Y. Potential screening indicators for early diagnosis of NAFLD/MAFLD and liver fibrosis: triglyceride glucose index-related parameters. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 13, 951689. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.951689 (2022).

Wang, J. et al. The diagnostic and prognostic value of the Triglyceride-Glucose index in metabolic Dysfunction-Associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD): A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 14 (23), 4969. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14234969 (2022).

Zhong, M. et al. Correlation of Asprosin and Nrg-4 with type 2 diabetes mellitus complicated with coronary heart disease and the diagnostic value. BMC Endocr. Disord. 23 (1), 61. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-023-01311-8 (2023).

Bhadel, P., Shrestha, S., Sapkota, B., Li, J. Y. & Tao, H. Asprosin and type 2 diabetes mellitus: a novel potential therapeutic implication. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents. https://doi.org/10.23812/19-244-E (2020).

Ertuna, G. N., Sahiner, E. S., Yilmaz, F. M. & Ates, I. The role of Irisin and Asprosin level in the pathophysiology of prediabetes. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 199, 110642. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2023.110642 (2023).

Mishra, I. et al. Asprosin-neutralizing antibodies as a treatment for metabolic syndrome. Elife. ;10:e63784. (2021). https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.63784 (2021).

de Paixão, B., Figueiredo, N. & Lopes, S. The impact of the obesity onset on the inflammatory and glycemic profile of women with severe obesity. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 20 (10), 976–983. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2024.04.015 (2024).

Mazur-Bialy, A. I., Asprosin, A. & Fasting-Induced Glucogenic, and orexigenic adipokine as a new promising Player. Will it be a new factor in the treatment of Obesity, Diabetes, or infertility? A review of the literature. Nutrients 13 (2), 620. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13020620 (2021). Published 2021 Feb 14.

Ovali, M. A. & Bozgeyik, I. Asprosin, a C-Terminal cleavage product of fibrillin 1 encoded by the FBN1 Gene, in health and disease. Mol. Syndromol. 13 (3), 175–183. https://doi.org/10.1159/000520333 (2022).

Lee, T., Yun, S., Jeong, J. H. & Jung, T. W. Asprosin impairs insulin secretion in response to glucose and viability through TLR4/JNK-mediated inflammation. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 486, 96–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mce.2019.03.001 (2019).

Al-Sulaiti, H. et al. Metabolic signature of obesity-associated insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. J. Transl Med. 17 (1), 348. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-019-2096-8 (2019).

Ke, F. et al. Combination of Asprosin and adiponectin as a novel marker for diagnosing non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Cytokine 134, 155184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cyto.2020.155184 (2020).

Acknowledgements

Conceptualization, M.K., A.B., E.D. A.PK., and A.J.K.; methodology, M.K., A.B., E.D., A.PK., K.S., A.A., and A.B.; software, A.B., and M.K.; validation, M.K., A.PK., and A.B.; formal analysis, M.K., A.B. and A.PK.; investigation, M.K. and A.PK.; resources, M.K., and A.B.; data curation, M.K., K.S., A.A., A.B., and A.PK.; writing—original draft preparation, M.K., A.B.; writing—review and editing, A.B., A.PK, and A.J.K.; visualization, M.K. and A.B.; supervision, A.B., A.J.K., and A.PK.; project administration, M.K. and A.B.; funding acquisition, M.K. and A.PK. All the authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was supported by the funds of the Ministry of Education and Science within the project “Excellence Initiative - Research University”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, M.K., A.B., E.D. A.PK., and A.J.K.; methodology, M.K., A.B., E.D., A.PK., K.S., A.A., and A.B.; software, A.B., and M.K.; validation, M.K., A.PK., and A.B.; formal analysis, M.K., A.B. and A.PK.; investigation, M.K. and A.PK.; resources, M.K., and A.B.; data curation, M.K., K.S., A.A., A.B., and A.PK.; writing—original draft preparation, M.K., A.B.; writing—review and editing, A.B., A.PK, and A.J.K.; visualization, M.K. and A.B.; supervision, A.B., A.J.K., and A.PK.; project administration, M.K. and A.B.; funding acquisition, M.K. and A.PK. All the authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics declarations

The procedures were approved by the Local Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Bialystok, Poland, and written informed consent was obtained from each participant (APK.002.364.2021).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kościuszko, M., Buczyńska, A., Duraj, E. et al. Associations between asprosin, insulin resistance, and oxidative stress in adults with obesity. Sci Rep 15, 40849 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24648-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24648-7

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Elevated asprosin in hypertension: evidence from an exploratory case-control study

Scientific Reports (2026)