Abstract

Kidney allograft fibrosis is a manifestation of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and predicts functional decline, and eventual allograft failure. This study evaluates whether spectral diffusion magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) detects early development and mild/moderate fibrosis in kidney allografts. In a prospective two-center study of kidney allografts, pathologic interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy (IFTA) was scored and eGFR was calculated from serum creatinine. Multi-b-value diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) (\({\text{bvalues}}=[0,10,30,50,80,120,200,400,800{\text{m}}{{\text{m}}^2}/{\text{s}}\)]) was post-processed with spectral diffusion, intravoxel incoherent motion (IVIM), and apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC). Relationships between imaging parameters and biological processes were measured by Mann-Whitney U-test and Spearman’s rank; diagnostic ability was measured by five-fold cross-validation univariate and multi-variate logistic regression. Quality control analyses included volunteer MRI (n = 4) and inter-observer analysis (n = 19). 99 patients were included (50 ± 13yrs, 64 M/35F, 39 IFTA = 0, 22 IFTA = 2, 20 IFTA = 4, 18 IFTA = 6, 46 eGFR ≤ 45mL/min/1.73m2, mean eGFR = 47.5 ± 21.3mL/min/1.73m2). Spectral diffusion detected fibrosis (\({\text{IFTA}}>0\)) in patients with normal/stable \({\text{eGFR}}>45{\text{ml}}/{\text{min}}/1.73{{\text{m}}^2}\) [\(\text{AUC}\,(95\%\,\text{CI}) = 0.72\,(0.56,\,0.87), \quad p = 0.007\)]. Spectral diffusion detected mild/moderate fibrosis (IFTA=2–4) [\(\text{AUC}\,(95\%\,\text{CI}) = 0.65\,(0.52,\,0.71), \quad p = 0.023\)], as did ADC [\(\text{AUC}\,(95\%\,\text{CI}) = 0.71\,(0.54,\,0.87), \quad p = 0.013\)]. eGFR, time-from-transplant, and allograft size could not. Interobserver correlation was ≥ 0.50 in 24/40 diffusion parameters. Spectral diffusion MRI showed detection of mild/moderate fibrosis and fibrosis before decline in function. It is a promising method to detect early development of fibrosis and CKD before progression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Kidney allograft interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy (IFTA) is a manifestation of chronic kidney disease (CKD)1 and is associated with allograft failure and increased patient mortality2,3. CKD progression is measured in stages by estimated glomerular filtration age (eGFR), which decreases as serum creatinine in blood increases; critically, patient outcome worsens as CKD progresses. Specifically, stage 3b (eGFR ≤ 45 ml/min/1.72m2) is associated with significantly increased risk of CKD progression, kidney failure, cardiovascular disease, and mortality. However, as kidneys can compensate for damage despite underlying progressing disease, standard-of-care laboratory measures for CKD progression may detect changes after irreversible kidney damage has significantly progressed. This diagnostic delay leads to a significant increase in the progression of CKD, kidney failure, and cardiovascular disease as time for early intervention and modified treatment regimens is lost4. However, the current reference standard of fibrosis is histopathology with an interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy score (IFTA = 0–6) which requires biopsy samples for diagnosis, staging of severity, continuous patient monitoring, as well as for studies of novel therapeutic outcome5. As such, there is use for a non-invasive imaging metric that can detect fibrosis without invasive biopsy, as well as provide information on kidney size, anatomy of the urinary system, and alternate diagnoses which biopsy and serum creatinine cannot provide. Noninvasive monitoring and subsequent early identification, diagnosis, and quantification of fibrosis could enable therapeutic interventions that may preserve kidney function, including modifications in the patient’s immunosuppressive regimen, and help screen for patients who may need further invasive biopsy.

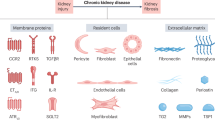

Diffusion weighted magnetic resonance imaging (DWI) is a method of non-invasive measurement of diffusion in kidneys without IV contrast, instead using diffusion weighting ‘b-values’6,7,8,9,10,11. In the kidney, there are numerous sources of water motion including motion in the tissue parenchyma, kidney tubules, and capillary perfusion in vasculature. When a range of multiple b-values are used in DWI of kidneys, there may be signal contribution from these numerous components with different diffusion coefficients. As such, in multi-b-value DWI, the signal may diverge from a standard mono-exponential into a multi-exponential with each exponential representing a different diffusion component. Multi-b-value DWI may add value to biopsy surveillance with whole kidney assessment of multiple physiological processes to assess diagnosis, disease severity, and potential salvageability. Preliminary studies investigating multi-component spectral diffusion in simulation of kidneys12,13,24, in healthy kidneys14,15, and in native kidneys with CKD16, suggest kidney allografts with reduced function and fibrosis may benefit from spectral diffusion that is sensitive to different physiologic components within a voxel.

As a step towards clinical translation, this work evaluates multi-b-value MRI for the noninvasive diagnosis and quantification of fibrosis and function in kidney allografts in a prospective two-center study. It tests multi-component spectral diffusion that allows one to three components (vascular perfusion, tubular flow, and tissue parenchyma)17, two-component intravoxel incoherent motion (IVIM18; tissue component and vascular component)8,19,20,21,22,23, and standard apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC). It then compares diagnostic ability of univariate and multiparametric logistic regression models built from these three diffusion models to those from standard clinical parameters to examine clinical relevance in early detection of fibrosis.

Results

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics

The demographics and clinical characteristics of all 99 patients (64 M/35F, 50 ± 13 y) are included in Supplement A. Comparisons between sites (Site 1: Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, Site 2: Weill Cornell Medical Center), and interobserver subset are included in Supplement A. Four volunteers (healthy controls; (1 F/3 M, 38.5 ± 11.8y) were scanned at Site 1. Right native kidneys were chosen for analysis to compare to allografts. This avoided tissue-air interface artifacts from the bowel, more prominent in the left kidney.

Example spectral diffusion

Example DWI (b = 0), T2w HASTE and corresponding example voxels with multi-b-value DWI curves and corresponding diffusion spectra are shown in Fig. 1. Diffusion model parameters (Table 1), as well as example spectral diffusion parameter maps (Fig. 2) are included in methods and materials.

Example DWI and T2 weighted HASTE images of volunteer native kidneys and allografts for each of the four classifications of function and fibrosis, labeled for each row. An example multi-b value DWI curve from a voxel in each of the rows is shown in the third column. The corresponding diffusion spectrum is shown in the fourth column, with the multi-exponential fit resulting from the spectrum plotted on top of the DWI curve in the third column. Vertical lines are shown to represent the boundaries used to separate spectral peaks (Supplement E).

Images of different \(fD\) components and ADC, superimposed on each respective b = 0 DWI from Fig. 1. These images are solely for illustration; they were not used for measurement. Unlike IVIM and ADC, spectral diffusion allows a flexible number of compartments and compartments that return 0 are indistinguishable from noise. As such, vascular and tubular images appear noisy. The trend of decreased tubular and vascular flow in diseased allografts can be seen. Note the difference in scale for the three compartments with \(f{D_{vasc}}\) having the largest range, and \(f{D_{tissue}}\) having the smallest. The rightmost column demonstrates corresponding histopathology trichrome stains for each patient with the large arrow noting glomeruli and the small arrow noting areas of fibrosis which stain blue.

Box plots showing change in diffusion measured with (a) spectral\(\:f{D}_{tubule}\), (b) IVIM \(\:f{D}^{*},\) and (c) ADC between volunteer native kidneys, and allografts with various renal functions and fibrosis scores. Kidneys were grouped ordinally by degree of renal disease as control volunteers (VC), healthy allografts (SFNF) to allografts with both impaired function and fibrosis (IFWF) as shown in the legend. Stable/healthy function is determined as eGFR > 45 ml/min/1.73m2, and ‘fibrosis’ determined as IFTA > 0. A line connecting the mean values for each group of kidneys is plotted to show the trend. As fraction f is unitless, and diffusion coefficient D is in 10-3 mm2/s the units of \(\:fD\) and \(\:f{D}^{*}\) are 10-3 mm2/s and is a proxy for flow volume per unit time.

Allografts compared to control kidneys

Patients were divided into clinical subgroups dichotomized by CKD stage 3b (“impaired” function if eGFR ≤ 45 ml/min/1.72m2) and by fibrosis (“fibrosis” if IFTA score > 0). Further detail regarding the multi-b-value DWI parameters is provided in the Post Processing Methods and Materials sections and corresponding Table 1. The boxplot in Fig. 3 shows \(\:f{D}_{tubule}\) decreasing between control kidneys, stable kidney allografts, and diseased allografts; in comparison, IVIM \(\:f{D}^{*}\), and ADC showed no significant correlation.

Detection of fibrosis

Parameters were considered significant if they returned both a Mann-Whitney U-test p < 0.05 and a cross-validated AUC p < 0.05. These significant diffusion model parameters for fibrosis are provided in Table 2; all other parameters are included in Supplement B. Spectral diffusion detected fibrosis in allografts (IFTA > 0) with \(\text{AUC}\,(95\%\,\text{CI}) = 0.69\,(0.59,\,0.81), \quad p < 0.001\) (Table 2a). Allografts with fibrosis had significantly increased \({f_{tissue}}\) and \(f{D_{tissue}}\), with reduced tubule and vascular component parameters. Mean \(f{D_{tissue}}\) [\(\text{AUC}\,(95\%\,\text{CI}) = 0.66\,(0.55,\,0.78), \quad p = 0.005\)] returned the highest univariate AUC. IVIM std D was significant, but neither IVIM nor ADC multiparametric AUCs were significant.

Spectral diffusion detected mild/moderate fibrosis in allografts (interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy score (IFTA) = 0 vs. IFTA = 1–4; Table 2b), with \(\text{AUC}\,(95\%\,\text{CI}) = 0.65\,(0.52,\,0.77), \quad p = 0.02\). Allografts with mild/moderate fibrosis had increased spectral diffusion tissue component parameters and reduced tubule and vascular component parameters. Mean \(f{D_{tissue}}\) [\(\text{AUC}\,(95\%\,\text{CI}) = 0.67\,(0.55,\,0.80), \quad p = 0.004\) again had the highest univariate AUC. IVIM tissue parameters were also significant (Table 2b), though not more so than spectral diffusion, and ADC did not have a parameter with both a significant Mann-Whitney U-test and a significant cross-validated AUC. Multiparametric spectral diffusion model was significant, but IVIM and ADC were not significant.

Only spectral diffusion detected severe fibrosis (IFTA = 0 vs. IFTA = 5-6; Table 2c) with \(\text{AUC}\,(95\%\,\text{CI}) = 0.68\,(0.52,\,0.85), \quad p = 0.026\). IVIM and ADC returned no univariate parameters with both significant Mann-Whitney U-test and cross-validated AUC, and their multiparametric models were also not significant (AUC p\(\geqslant\)0.05). Results for every parameter across all fibrosis diagnoses are included in Supplement B.

Detection of fibrosis in allografts with normal/stable function

Diffusion model parameters with both significant Mann-Whitney U-test and AUCs for detecting fibrosis in allografts with normal/stable function are shown in Table 3. Spectral diffusion detected fibrosis in allografts presenting with normal/stable function \(\text{AUC}\,(95\%\,\text{CI}) = 0.72\,(0.56,\,0.87), \quad p < 0.01\) (Table 3a). Median \(\:f{D}_{tissue}\) \(\text{AUC}\,(95\%\,\text{CI}) = 0.70\,(0.55,\,0.86), \quad p = 0.006\) had the highest univariate AUC for spectral diffusion. Both ADC and IVIM also showed an increase in the tissue component parameters in patients with fibrosis with significant univariate models, though IVIM did not return significant multi-parametric models (Table 3a).

Allografts with both impaired function and fibrosis showed increased tissue compartment heterogeneity and decreased tubule component parameters compared to healthy allografts (Table 3b). Spectral diffusion did not detect allografts with impaired function but no fibrosis; while stdev\(\:\:{D}_{tissue}\)was significant, it did not pass multiple comparisons correction. Results for every parameter across all clinical subgroups are included in Supplement C.

Multi-component \({\varvec{f}}{\varvec{D}}\) correlated with IFTA score

Spectral diffusion \(f{D_{tissue}}\) correlated positively with IFTA score in patients with normal/stable function (Spearman’s rank = 0.359, p < 0.01; Fig. 4a). \(f{D_{tubule}}\) correlated negatively with IFTA score (Fig. 4b) while \(f{D_{vasc}}\) did not achieve statistical significance (Fig. 4c). IVIM mean \(\left( {1 - f} \right)D\) and mean ADC, both alternate measures of diffusion in tissue parenchyma, also correlated positively with IFTA score (Fig. 4d-e).

Significant correlation was also seen between IFTA and \(fD_{vasc}, fD_{tubule}, fD_{tissue} \) across the entire patient cohort, i.e. not dichotomized by kidney function (Spearman’s Rank = -0.20, -0.27, +0.24, \({\text{p}}=0.045, 0.005, 0.015\) respectively). However, there was no significant correlation within the subset of patients presenting with impaired function (\({\text{p}}=0.158 - 0.521\)). Correlation was predominately in those presenting with normal/stable function.

The top row shows spectral diffusion parameters of (a) mean \(f{D_{tissue}}\), (b) mean \(f{D_{tubule}}\), and (c) mean \(f{D_{vasc}}\) correlated against Banff 2017 IFTA scores in patients presenting with normal/stable eGFR\(>45\) ml/min/1.73m2. The bottom row shows the same correlations for (d) IVIM mean \(\left( {1 - f} \right)D\), (e) mean ADC, and (f) CKD-EPI eGFR.

Diagnosis of fibrosis with clinical parameters

Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) detected fibrosis with \(\text{AUC}\,(95\%\,\text{CI}) = 0.63\,(0.52,\,0.74), \quad p = 0.027\) (IFTA=0 vs. IFTA>0; Table 4). However, eGFR could not differentiate between no fibrosis and mild/moderate fibrosis or detect fibrosis if eGFR > 45 ml/min/1.73m2. Further, eGFR showed no correlation with fibrosis within the subsets of either normal/stable eGFR (Spearman’s rank = - 0.125, p = 0.370; Fig. 4F) or impaired eGFR (Spearman’s rank = - 0.128, p = 0.520). Instead, eGFR differentiated between the severe fibrosis and mild/moderate fibrosis (Table 4) and correlated with IFTA score across all patients (Spearman’s rank = - 0.342,p < 0.01).

Allografts without fibrosis had shorter transplant intervals than those with severe fibrosis, i.e. an allograft was more likely to have developed fibrosis over time. This held true for both mean transplant interval (Table 4) and median transplant interval (allografts with no fibrosis had a median interval of 284 days, mild/moderate fibrosis with a median of 463 days, and severe fibrosis with a median of 888 days). However, transplant interval was not significant for any other comparison in this study. Allograft volume, patient age, and BMI were not significant (\({\text{p}}>0.10\)) for any comparisons.

Combined MR diffusion and eGFR

Combined spectral diffusion parameters and eGFR detected fibrosis (IFTA = 0 vs. IFTA > 0), but it did not outperform spectral diffusion alone \(\text{AUC}\,(95\%\,\text{CI}) = 0.68\,(0.58,\,0.79), \quad p < 0.01; \quad \text{DeLong}\,p = 0.58\). Spectral diffusion alone had the highest AUC for detection of mild/moderate IFTA. Inclusion of eGFR, allograft volume, Transplant-to-MRI interval, patient age, and patient BMI decreased the mean AUC, which is expected as they were not significant.

Interobserver reproducibility and SNR

Interobserver correlation ranged from poor to excellent (intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) range = 0.03–0.92) with 5/40 features returning an ICC between 0 and 0.25, 11/40 features returning an ICC between 0.25 and 0.50, 14/40 with an ICC between 0.50 and 0.75, and 10/40 with ICC above 0.75. Tissue diffusion components showed better interobserver reliability than tubular components, and IVIM and ADC demonstrated better ICC and coefficient of variation (CoV(%)) than spectral diffusion. A full table of all ICC and CoV% is included in Supplement D. The signal-to-noise ratio of the DWI b = 0 kidney allografts, after motion correction and denoising, ranged from 30 to 50.

Discussion

In this work, multi-b-value spectral diffusion was able to detect fibrosis and demonstrated good sensitivity to mild/moderate fibrosis that IVIM, ADC, eGFR, time-from-transplant, and allograft size did not. Further, spectral diffusion MRI detected fibrosis in allografts that were still presenting with normal/stable eGFR. This study expanded spectral diffusion from simulation of multi-component kidney diffusion12,24and control volunteers14,15 to clinical translation of a multi-component diffusion model that includes more aspects of renal physiology. Unlike ADC25, MR elastography26, and IVIM27, spectral diffusion separates diffusion components beyond vascular perfusion and tissue structure to provide insight into complex renal tubule physiology. Allografts showed lower tubular and tissue diffusion than volunteers, agreeing with previously observed reduced diffusion and fluid transport28. Allografts with fibrosis also had lower vascular and tubular parameters which supports detecting damaged microvasculature and tubules in fibrotic and dysfunctional kidneys29.

Across clinical comparisons, the tissue component parameters (\({f_{tissue}},~{D_{tissue}},~f{D_{tissue}},~\)IVIM D, \(\left( {1 - f} \right)D\), \(ADC\)) were the most significant for clinical diagnoses15. The fibrotic allografts had increased \(f{D_{tissue}}\), supporting correlation with increased collagen deposition. While \({D_{tissue}}\) might be expected to decrease with fibrosis due to greater diffusion restriction from collagen, the increase in signal fraction of \({f_{tissue}}\) made the product \(f{D_{tissue}}\) increase with fibrosis. This suggests \(f{D_{tissue}}\) detects fibrous allograft tissue from the greater amount of the restricted diffusion, rather than slowed diffusion. Spectral diffusion improved diagnostic ability compared to IVIM D (using a bi-exponential to remove fast diffusion contamination) or ADC with \(b>200\) (excluding low b-values dominated by fast diffusion signal). This supports advanced separation of diffusion components in kidney disease30 to remove signal contamination from the tissue diffusion component and provide signal fraction.

Spectral diffusion separated mild/moderate fibrosis from no fibrosis while eGFR, allograft size, and time-to-transplant did not. Detection of mild/moderate fibrosis is clinically important as it may allow preventative or early intervention and treatment. Spectral diffusion could be another clinical measure, in addition to proteinuria, donor-derived cell-free DNA, and creatinine, for fibrosis detection and assessment of progression31,32,33. Further, eGFR only significantly decreased once there were high levels of fibrosis, agreeing with current clinical knowledge; decreased eGFR tends to be a marker post the stage of irreversible fibrosis and considerable scarring34. In comparison, spectral diffusion detected fibrosis even when eGFR was normal/stable. This supports spectral diffusion detecting early change in microstructural diffusion patterns and not being solely an indirect and more costly measure of GFR.

Results support \(fD\) as a parameter of interest. \(fD\) of the vascular, tubule, and tissue components were significant and improved AUC values, as did IVIM \(\left( {1 - f} \right)D\). \(f{D_{tubule}}\) correlating negatively against IFTA scores supports detection of renal filtrate and tubule destruction in patients presenting with normal/stable function. Similarly, the positive correlation of \(f{D_{tissue}}\) against IFTA scores supports detecting collagen deposition with nephron degeneration and tubular injury in allografts, rather than lower ADC observed in native kidneys35. As there have been mixed results regarding reduced ADC detecting restricted diffusion in allografts, these results support \(f{D_{tissue}}\) which includes the diffusion fraction as a potential alternate, along with previously observed corticomedullar difference8,36,37.

Finally, spectral diffusion did not distinguish between fibrosis and no fibrosis for the subset with impaired function, nor between normal/stable function and impaired function for the subset with fibrosis. This highlights an important caveat: if a patient demonstrated impaired eGFR, spectral diffusion did not determine if the impaired allograft was fibrotic or not. However, detection of early fibrosis in patients presenting with normal/stable function remains clinically relevant.

We recognize several limitations. Further study is needed of spectral diffusion peak sorting, multi-component rigid models9,24,38, and parameter stability. Whole cortex segmentation rather than circular ROIs may improve coverage and interobserver reliability, at the cost of artifacts. T2 effects, corticomedullary difference, and the influence of anisotropic collecting tubules in the medulla was beyond the scope of this work in allografts, but has shown promise in CKD of native kidneys16. Longitudinal study is needed to test if spectral diffusion can be an early predictor of fibrosis and function decline, and study of immune rejection in addition to fibrosis is warranted given that this is a potentially confounding pathologic variable8. Cardiac effect, non-Gaussian diffusion, and flow effects were not corrected for39. While this study demonstrated potential clinical translation of \(fD\), validation of \(fD\) as a flow proxy may benefit from comparison to phantoms, microspheres, and flow cytometry in animal models40, and radiotracers in human studies. This study included both protocol biopsies and clinically indicated biopsies, which may introduce some bias in terms of patient selection. Comparison and combination with other fibrosis assessment metrics such as T1 imaging is worth future study. Future research on multi-b-value DWI is needed to study if it could enable earlier detection of CKD prior to decline in eGFR, inform decisions to pursue biopsy or change the medication regimen, and allow longitudinal monitoring in clinical trials of anti-fibrotic medications41,42,43.

This work supports multi-component spectral diffusion detecting fibrosis in allografts presenting with normal function as well as mild/moderate fibrosis development and correlation with fibrosis severity. Pending further study, multi-b-value diffusion MRI could be a noninvasive method of monitoring and subsequent early identification, diagnosis, and quantification of fibrosis in renal allografts.

Materials and methods

Patients

This is a prospective, IRB-approved (STUDY-21-00848 as of August 6th, 2021) HIPAA-compliant two-center study at the Icahn school of Medicine at Mount Sinai and Weill Cornell Medicine (NCT05058170) that consists of kidney transplant recipients referred for percutaneous clinically indicated biopsies due to impaired allograft function or normal/stable function undergoing percutaneous protocol biopsies due to the presence of donor specific antibodies. Patients included in the study were those enrolled from 02/2022 to 09/2024 who are > 1-month post-transplant. Informed consent was obtained, and patients underwent a non-contrast MRI protocol within 7 days of biopsy that included advanced DWI, as well as arterial spin labeling (ASL), blood oxygen level dependent imaging (BOLD), T1ρ, T1 relaxometry, and anatomical sequences (T2 HASTE, T1 in/opposed phase) that are beyond the scope of this current study. Exclusion criteria were age < 18 years, large vessel or urinary tract complication of the kidney transplant, contra-indications to MRI, or pre-existing medical conditions including a likelihood of developing seizures or claustrophobic reactions. All experiments were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and allografts were procured according to the standard of care for subjects enrolled in the study at the Icahn school of Medicine at Mount Sinai and at Weill Cornell Medicine following relevant guidelines and regulations.

Image acquisition

Patients underwent identical MR protocol with a 3T MRI (Mount Sinai: Skyra, Siemens Healthcare, Cornell: Prisma, Siemens Healthcare), set up by the same investigator at both sites, with a 16-channel body array and 32-channel spine array coils. The advanced DWI protocol was 2D coronal spoiled gradient echo-planar IVIM-DWI from the Siemens Advanced Body Diffusion works-in-progress package (WIP-990 N) with respiratory gating (by liver-dome tracking, pencil-beam navigator). Averaged and motion-corrected trace-weighted DWIs were exported directly from the scanner with ‘motion-corrected (MOCO)-averages’, ‘MOCO b-values’, ‘MOCO-3D’, ‘rescale local bias corruption’ and denoising44 selected for all 9 b-values (b-values\(=\left[ {0,~10,~30,~50,~80,~120,~200,~400,~800~s/m{m^2}} \right]\); TR/TE = 1500/58ms, voxel size = 2 × 2 × 5 mm3, 4-directions, 16 slices, 3-averages, acquisition time ~ 7–15 min). Control volunteers underwent the same protocol at Mount Sinai.

Image analysis

Six circular regions-of-interest (average ROI size: 64 ± 25 mm2) were delineated at the renal hilum on motion corrected b = 0 s/mm2 by a radiologist (Observer 1, 13 years of experience) using T2-weighted images as reference (Horos v. 3.2.1, www.horosproject.org). As kidney biopsies are restricted to the renal cortex, two cortical ROIs were drawn each at the upper pole, midpole, and lower pole, and propagated to each motion-corrected b-value (6 total ROIs per allograft, diagram in Supplement E) Voxel-wise analysis outperformed ROI-averaged signal and so is reported in this work. As signal intensity and heterogeneity is often an important biomarker, and the distributions within the ROIs were not necessarily normal, the mean, median, and standard deviation of MRI parameters were assessed.

Spectral diffusion post-processing

Spectral diffusion was analyzed by fitting voxel-wise DWI decay curves within each ROI using non-negative least squares (NNLS) in MATLAB (Mathworks Inc, 2023b). The voxel-wise signal as a function of increasing b-value were fit to 300 logarithmically spaced D values (log10(5)-log10(2200)) as an unconstrained sum of exponentials (Eq. 1)12,24,45

In Eq. (1), yi is the equation for each of the N = 9 b-values, for M=300 D values. \({y_i}\) as a function of b-value is the equation fit to the DWI decay curve. Minimizing the difference between Eq. 1 and the DWI decay curve, with Tikhonov regularization to smooth in the presence of noise, outputs a diffusion spectrum of the contributions of all 300 exponential basis vectors12. \(\lambda\) was set at 0.1 to match optimal \(\lambda \approx \frac{{\# bval}}{{SNR}}\) and reduce computation time12,24.

The resulting spectra have peaks that represent the dominant basis vectors (Fig. 1) per voxel without a priori assumption of number of peaks. Each peak returns a signal fraction f and mean diffusion coefficient D, and spectral peaks can be sorted into (1) vascular, (2) tubular, and (3) tissue parenchyma components15,24. A diffusion spectrum with three components would fit a tri-exponential equation as follows.

Voxels with \({R^2}<0.70\) were excluded from analysis. Example MR images with sample advanced DWI decay curve and spectral analysis are shown in Fig. 1. Table 1 provides parameter definitions and the physiologic processes they may represent. Further detail regarding the fitting and analysis of diffusion spectra is included in Supplement E.

IVIM and ADC post-processing

The voxel-wise DWI decay curve was fit to standard IVIM bi-exponential, \(f{e^{ - b{D^*}}}+\left( {1 - f} \right){e^{ - bD}}\), with a Bayesian-log estimation46 given priors log D mean = 6.2 ± 1 and log \({D^*}\) mean = 3.5 ± 147. A mono-exponential ADC was calculated with a least-squares linear log fit of the signal from \({\text{b}}=200,400,800{\text{s}}/{\text{m}}{{\text{m}}^2}\). This excluded IVIM effects at low b-values and non-Gaussian effects at high b-values43. Voxels with \({{\text{R}}^2}<0.70\) were excluded from analysis.

Multi-component diffusion \({\varvec{f}}{\varvec{D}}\) parameter

A parameter \(fD\) was calculated for each diffusion component as the product of the fraction and diffusion coefficient of the individual spectral peaks (e.g. \({f_{tissue}} \times {D_{tissue}}=f{D_{tissue}}\); Supplement E). In standard bi-exponential IVIM, \(f{D^*}\) has been used as a marker of blood flow in a capillary network19,20,48. In this study, \(fD\) was used as an estimate of local intravoxel ‘flow’ of every component. \(f{D_{vasc}}\) estimated the vascular motion, \(f{D_{tubule}}\) estimated tubular motion, and \(f{D_{tissue}}\) estimated total tissue diffusion in volume/time24. For the standard bi-exponential, IVIM \(f{D^*}\) and \(\left( {1 - f} \right)D\) were used to estimate the ‘flow’ of vascular and tissue components respectively. Figure 2 demonstrates \(fD\) of the three components.

Interobserver agreement

Circular ROIs (average ROI size: 78 ± 14 mm2) sampling the cortex of a subset of n = 19 allografts, chosen from each clinical subgroup blinded to images, were delineated by an independent observer (Observer 2, a medical student with 1 year of experience) blind to original ROIs and diagnoses. Interobserver agreement was calculated via ICC and CoV% for all MR parameters. ROI placement and ROI size were not standardized between the two observers, but slice selection was held constant.

Kidney volume measurement

For assessment of three-dimensional volumetric measurement of the allograft in milliliters (ml), T1 in-phase images were copied to a post-processing workstation (Vitrea core, Vital Images, Minnetonka, MN, USA). Three-dimensional reconstruction was performed using semi-automated interposition based on signal intensity differences of the allograft compared to the surrounding tissues by Observer 1.

Laboratory values and histopathology

Serum creatinine was collected at time of imaging or biopsy for measurement of eGFR calculated with race agnostic CKD-EPI 2021 criteria49. Interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy (IFTA = ci + ct) scores (range, 0–6) by pathologists were extracted from the clinical biopsy report, scored according to the Banff 2017 classification50. Other Banff diagnoses within the allograft specimens were also recorded50 (Supplement F), but inflammation/rejection is beyond the scope of this study.

Diagnostic classifications and clinical subgroups

IFTA score was used to diagnose fibrosis (no fibrosis: IFTA = 0, fibrosis: IFTA > 0), and fibrosis severity (mild/moderate: IFTA = 1–4, severe: IFTA = 5–6). Normal/stable allograft function was determined as \({\text{eGFR}} > 45{\text{ml}}/{\text{min}}/1.73{{\text{m}}^2}\), and impaired function determined as \({\text{eGFR}}\leq45{\text{ml}}/{\text{min}}/1.73{{\text{m}}^2}\). A threshold of \(45{\text{ml}}/{\text{min}}/1.73{\text{m}}^{2}\) was used to compensate for single kidney filtration. Allografts were further divided into clinical subgroups: allografts with (1) normal/stable function and no fibrosis, (2) impaired function no fibrosis, (3) normal/stable function and fibrosis, (4) impaired function and fibrosis.

Statistical analysis and machine learning

To examine a direct connection between imaging parameters and biological processes, histogram characteristics voxel-wise mean, median, and standard deviation of the cortical ROIs were analyzed with respect to laboratory values and diagnoses. Central tendency measures (mean, median) of each component’s \(fD\) were included as MR parameters. Significant parameters were determined with non-parametric Mann-Whitney U-test \(p<0.05\) as a measure of the difference between medians; mean and standard deviation of the groups is provided for relevance in clinical image analysis. The Benjamini-Hochberg procedure was applied for multiple comparisons corrections with a generous false discovery rate of 0.20, set to reduce false negatives in a novel method. Correlation of MR parameters against IFTA score was calculated with Spearman’s rank and difference between clinical subgroups determined with ANOVA.

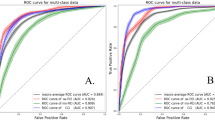

To examine diagnostic ability of imaging parameters and their direct relation to underlying physiology, univariate supervised machine learning logistic regression were built using significant histogram parameters with 5-fold cross validation. Diagnostic performance was assessed via receiver operating characteristic (ROC) and area-under-the-curve (AUC); mean AUC and 95% confidence interval (95%CI) was calculated via bootstrapping, and AUCs compared via the DeLong test. Sensitivity (SN), specificity (SP), and the optimal probability cutoff was calculated at the Youden’s J-statistic (J-stat cutoff).

To compare overall diagnostic ability, one multiparametric model was built using parameters from each sequence (spectral diffusion, IVIM, and ADC) with 5-fold cross-validation for each diagnostic classification. Histogram characteristics for the multiparametric models were chosen as parameters that had \(p<0.05\) within training sets. This reduced data leakage and model overfitting in a small preliminary dataset. All statistical analysis and machine learning was performed in Python 3.11.4 (Anaconda Inc., 2024).

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

The code developed for spectral diffusion analysis in this work is available at https://github.com/miramliu/Spectral_Diffusion.

Abbreviations

- IVIM:

-

Intravoxel incoherent motion

- IFTA:

-

Interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy

- eGFR:

-

Estimated glomerular filtration rate

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

References

Romagnani, P. et al. Chronic kidney disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 3, 1 (2017).

Mannon, R. B. et al. Inflammation in areas of tubular atrophy in kidney allograft biopsies: a potent predictor of allograft failure. Am. J. Transplant. 10 (9), 2066–2073 (2010).

Mengel, M. Deconstructing interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy: a step toward precision medicine in renal transplantation. Kidney Int. 92 (3), 553–555 (2017).

Tangri, N. et al. Patient management and clinical outcomes associated with a recorded diagnosis of stage 3 chronic kidney disease: the REVEAL-CKD study. Adv. Therapy. 40 (6), 2869–2885 (2023).

Ho, Q. Y. et al. Complications of percutaneous kidney allograft biopsy: systematic review and Meta-analysis. Transplantation 106 (7), 1497–1506 (2022).

Leung, G. et al. Could MRI be used to image kidney fibrosis? A review of recent advances and remaining barriers. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 12 (6), 1019–1028 (2017).

Elsingergy, M. M. et al. Imaging fibrosis in pediatric kidney transplantation: a pilot study. Pediatr. Transplant. 27, 5 (2023).

Bane, O. et al. Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging shows promising results to assess renal transplant dysfunction with fibrosis. Kidney Int. 97 (2), 414–420 (2020).

van Baalen, S. et al. Intravoxel incoherent motion modeling in the kidneys: comparison of mono-, bi-, and triexponential fit. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 46 (1), 228–239 (2017).

van der Bel, R. et al. A tri-exponential model for intravoxel incoherent motion analysis of the human kidney: in Silico and during Pharmacological renal perfusion modulation. Eur. J. Radiol. 91, 168–174 (2017).

Fan, M. et al. Quantitative assessment of renal allograft pathologic changes: comparisons of mono-exponential and bi-exponential models using diffusion-weighted imaging. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 10 (6), 1286–1297 (2020).

Periquito, J. S. et al. Continuous diffusion spectrum computation for diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging of the kidney tubule system. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 11 (7), 3098–3119 (2021).

Jasse, J. et al. Toward optimal fitting parameters for Multi-Exponential DWI image analysis of the human kidney: a simulation study comparing different fitting algorithms. Mathematics 12, 4 (2024).

Stabinska, J. et al. Probing renal microstructure and function with advanced diffusion MRI: concepts, applications, challenges, and future directions. J. Magn. Resonanc. Imaging (2023).

Stabinska, J. et al. Spectral diffusion analysis of kidney intravoxel incoherent motion MRI in healthy volunteers and patients with renal pathologies. Magn. Reson. Med. 85 (6), 3085–3095 (2021).

Hu, W. et al. Assessing renal interstitial fibrosis using compartmental, non-compartmental, and model-free diffusion MRI approaches. Insights into Imaging 15, 1 (2024).

Wurnig, M. C., Germann, M. & Boss, A. Is there evidence for more than two diffusion components in abdominal organs? – a magnetic resonance imaging study in healthy volunteers. NMR Biomed. 31, 1 (2017).

Le Bihan, D. et al. Separation of diffusion and perfusion in intravoxel incoherent motion MR imaging. Radiology 168 (2), 497–505 (1988).

Le Bihan, D. What can we see with IVIM MRI? NeuroImage 187, 56–67 (2019).

Federau, C. et al. Measuring brain perfusion with intravoxel incoherent motion (IVIM): initial clinical experience. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 39 (3), 624–632 (2013).

Wang, W. et al. Intravoxel incoherent motion diffusion-weighted imaging for predicting kidney allograft function decline: comparison with clinical parameters. Insights into Imaging 15, 1 (2024).

Hectors, S. J. et al. Assessment of hepatocellular carcinoma response To 90Y radioembolization using dynamic contrast material–enhanced MRI and intravoxel incoherent motion Diffusion-weighted imaging. Imaging Cancer 2, 4 (2020).

Zhang, M. C. et al. IVIM with fractional perfusion as a novel biomarker for detecting and grading intestinal fibrosis in crohn’s disease. Eur. Radiol. 29 (6), 3069–3078 (2018).

Liu, M. et al. Estimation of multi-component flow in the kidney with multi-b-value spectral diffusion. Magn. Reson. Imaging (2025).

Zhang, J. L. et al. Variability of renal apparent diffusion coefficients: limitations of the monoexponential model for diffusion quantification. Radiology 254 (3), 783–792 (2010).

Lee, C. U. et al. MR elastography in renal transplant patients and correlation with renal allograft biopsy. Acad. Radiol. 19 (7), 834–841 (2012).

Mao, W. et al. Intravoxel incoherent motion diffusion-weighted imaging for the assessment of renal fibrosis of chronic kidney disease: a preliminary study. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 47, 118–124 (2018).

Eisenberger, U. et al. Evaluation of renal allograft function early after transplantation with diffusion-weighted MR imaging. Eur. Radiol. 20 (6), 1374–1383 (2009).

Kaissling, B., LeHir, M. & Kriz, W. Renal epithelial injury and fibrosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Mol. Basis Dis. 1832 (7), 931–939 (2013).

Bane, O. et al. Renal MRI: from nephron to NMR signal. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 58 (6), 1660–1679 (2023).

Ponticelli, C. & Graziani, G. Proteinuria after kidney transplantation. Transpl. Int. 25 (9), 909–917 (2012).

Leotta, C. et al. Levels of Cell-Free DNA in kidney failure patients before and after renal transplantation. Cells 12, 24 (2023).

Bu, L. et al. Clinical outcomes from the assessing Donor-derived cell-free DNA monitoring insights of kidney allografts with longitudinal surveillance (ADMIRAL) study. Kidney Int. 101 (4), 793–803 (2022).

Boor, P. & Floege, J. Renal allograft fibrosis: biology and therapeutic targets. Am. J. Transplant. 15 (4), 863–886 (2015).

Ferguson, C. M. et al. Renal fibrosis detected by diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging remains unchanged despite treatment in subjects with renovascular disease. Sci. Rep. 10, 1 (2020).

Beck-Tölly, A. et al. Magnetic resonance imaging for evaluation of interstitial fibrosis in kidney allografts. Transplant. Direct 6, 8 (2020).

Berchtold, L. et al. Diffusion-magnetic resonance imaging predicts decline of kidney function in chronic kidney disease and in patients with a kidney allograft. Kidney Int. 101 (4), 804–813 (2022).

Jiang, K., Ferguson, C. M. & Lerman, L. O. Noninvasive assessment of renal fibrosis by magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound techniques. Translational Res. 209, 105–120 (2019).

Sigmund, E. E. et al. Cardiac phase and flow compensation effects on renal flow and microstructure anisotropy MRI in healthy human kidney. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 58 (1), 210–220 (2022).

Hammond, T. G. & Majewski, R. Analysis and isolation of renal tubular cells by flow cytometry. Kidney Int. 42 (4), 997–1005 (1992).

Thoeny, H. C. & Grenier, N. Science to practice: can Diffusion-weighted MR imaging findings be used as biomarkers to monitor the progression of renal fibrosis? Radiology 255 (3), 667–668 (2010).

Rankin, A. J. et al. Will advances in functional renal magnetic resonance imaging translate to the nephrology clinic? Nephrology 27 (3), 223–230 (2021).

Ljimani, A. et al. Consensus-based technical recommendations for clinical translation of renal diffusion-weighted MRI. Magn. Reson. Mater. Phys., Biol. Med. 33 (1), 177–195 (2019).

Kannengiesser, S. et al. Universal iterative denoising of complex-valued volumetric MR image data using supplementary information. Proc. Intl. Soc. Mag. Reson. Med. 24, 2016 (2016).

Bjarnason, T. A. & Mitchell, J. R. AnalyzeNNLS: magnetic resonance multiexponential decay image analysis. J. Magn. Reson. 206 (2), 200–204 (2010).

Neil, J. J. & Bretthorst, G. L. On the use of bayesian probability theory for analysis of exponential decay date: an example taken from intravoxel incoherent motion experiments. Magn. Reson. Med. 29 (5), 642–647 (2005).

Jerome, N. P. et al. Comparison of free-breathing with navigator‐controlled acquisition regimes in abdominal diffusion‐weighted magnetic resonance images: effect on ADC and IVIM statistics. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 39 (1), 235–240 (2013).

Federau, C. & O’Brien, K. Increased brain perfusion contrast with T2-prepared intravoxel incoherent motion (T2prep IVIM) MRI. NMR Biomed. 28 (1), 9–16 (2014).

Delgado, C. et al. A unifying approach for GFR estimation: recommendations of the NKF-ASN task force on reassessing the inclusion of race in diagnosing kidney disease. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 79 (2), 268–288e1 (2022).

Haas, M. et al. The Banff 2017 kidney meeting report: revised diagnostic criteria for chronic active T cell–mediated rejection, antibody-mediated rejection, and prospects for integrative endpoints for next-generation clinical trials. Am. J. Transplant. 18 (2), 293–307 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Siemens for providing the Advanced Body Diffusion WIP sequence with multiple variable b-values, motion correction, and denoising, as well as Dr. Mena Shenouda for advice on machine learning analysis.

Funding

This project was funded by NIH NIDDK R01DK129888 (PI: Lewis/Bane) and supported by NIH CTSA postdoctoral training grant number TL1TR004420 (Fellow: Liu).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ML was lead formal analysis, lead original draft, lead conceptualization, lead methodology. JD was supporting conceptualization, supporting data acquisition, supporting investigation, equal resources.TG was supporting formal analysis, supporting software, supporting methodology. JJ was supporting formal analysis. IB was equal project administration, equal data curation, equal project administration. SC was equal project administration, equal data curation, equal project, administration. AK was equal project administration, equal data curation, equal project administration. TC and AKD were equal project administration, equal data curation, equal project administration. SP was supporting investigation, supporting data curation. SS was supporting data acquisition, supporting data curation. IS supporting data acquisition, supporting data curation. TM was supporting data acquisition, supporting data curation. BT was supporting conceptualization, supporting investigation, supporting resources, supporting supervision. SF was supporting data acquisition, formal analysis, supporting methodology. OB was lead investigation, lead resources, lead supervision, lead funding acquisition, supporting methodology, supporting conceptualization. SL was lead investigation, lead resources, lead supervision, lead funding acquisition, supporting methodology, supporting conceptualization. All authors contributed to writing and approval of the final draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, M.M., Dyke, J., Gladytz, T. et al. Detecting early kidney allograft fibrosis with multi-b-value spectral diffusion MRI. Sci Rep 15, 40959 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24701-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24701-5