Abstract

Magnetic measurements under hydrostatic pressure (P) up to 10 kbar and x-ray diffraction measurements up to 10.7 kbar were performed for a single crystal of Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34, which is non-superconducting at ambient pressure. In this compound, we have found pressure-induced recovery of the superconducting state at Tc equal to 13.0 K for P = 10 kbar. We determined the parameters characterizing the superconducting state, including the lower and the upper critical fields, coherence length, and penetration depth, and compared them with those for Fe0.99Te0.66Se0.34. We found that the lower critical field for Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34 at 0 K and 10 kbar is comparable to the lower critical field for Fe0.99Te0.66Se0.34 at ambient pressure, while the upper critical field is significantly higher than that for Fe0.99Te0.66Se0.34 at ambient pressure. The estimated increase in superconducting carrier density and effective mass under pressure can be explained if one assumes that applied pressure leads to an increase in structural disorder in the studied material. At 10 kbar, the zero-field critical current density for Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34 is four times larger than that for Fe0.99Te0.66Se0.34 at ambient pressure. The x-ray diffraction results indicate that under pressure crystal quality apparently degrades. Comprehensive studies of the impact of pressure on the crystal structure indicate an increasing mosaicity evolution with pressure, suggesting that the pressure-induced superconductivity of Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34 originates from inhomogeneities, associated also with the superconductivity in other sulpho-iron seleno-tellurides and anti-PbO-type structures. Obviously, the pressure effect on the crystallographic structure can lead to changes in the electronic structure, which is not excluded.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The discovery of superconductivity in the layered iron chalcogenides of general formula Fe(Se, Ch), so-called ‘11-type’ compounds with Ch = S, Te, activated intense studies of metal chalcogenides, aimed at revealing the mechanism of superconductivity, means of increasing the critical temperature Tc and improved insight into the relationship between superconductivity and magnetism1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12. In the FeTe1− xSex system, at ambient pressure, the superconducting transition temperature is the highest (~ 14 K) for FeTe0.5Se0.52,5. The application of hydrostatic pressure to this compound leads to an increase of Tc as well as of the other parameters of the superconducting state, including the upper critical field (Hc2), the lower critical field (Hc1), and the critical current density (jc)13. In the case of the Fe0.99Te0.66Se0.34 compound, with lower selenium content and a slightly lower critical temperature (12.8 K) at ambient pressure than that of FeTe0.5Se0.5, we have also noticed an enhancement of all basic parameters of the superconducting state under hydrostatic pressure14.

It was shown15,16,17,18 that a small disorder in the magnetic sublattice due to substituting Fe atoms by Co, Ni, or Cu decreases Tc in the FeTe1− xSex system under ambient pressure. However, for Fe0.994Ni0.007Te0.66Se0.34 subjected to hydrostatic pressure, we observed an enhancement of all superconducting properties, similar to that in Fe0.99Te0.66Se0.3414. Thus, one can see that despite the weakening of superconducting state properties by the substitution of Ni at the Fe site or changes in the Se/Te ratio, the hydrostatic pressure leads to an improvement of superconducting state properties.

It was reported that for the single crystals substituted with Cu content exceeding 1.5 atomic %, superconductivity is completely destroyed15 and the restoration of superconductivity under pressure in Cu-doped polycrystalline FeSe with small doping levels of 3% and 4% has been found19. It was noticed that this result differs from earlier experiments on pressure-induced superconductivity in SrFe2As2 and BaFe2As2 (‘122’-type compounds)20, because superconductivity in Cu-doped FeSe was initially suppressed due to doping and next restored with pressure, whereas in the 122 compounds, initially nonsuperconducting samples become superconducting under pressure19. Reports indicated that the enlargement of the lattice parameter a accompanies the disappearance of superconductivity for small Cu doping in FeSe, while DFT calculations attribute the vanishing of the superconducting state to the enhancement of magnetism for larger lattice parameters19. It was shown that under pressure the lattice parameter a reaches its initial value, the static susceptibility is suppressed, and the superconducting state is stabilized, consistently with theoretical predictions19. It was suggested that it is worthwhile to investigate other iron arsenide superconductors within the range of stoichiometry where they are non-superconducting. Such studies allow us to determine if their superconducting properties are also sensitive to lattice parameters, as was shown for FeSe, or whether this compound is special among iron pnictide superconductors19. Zajicek et al.21 have discussed the significant impact of impurity scattering on the electronic and superconducting properties of Cu-doped FeSe. The authors concluded that the Cu impurities strongly suppress nematic and superconducting states and increase residual resistivity. The authors stated that the suppression of the superconducting state caused by Cu doping is consistent with changes of sign of s± order parameter. Moreover, compressive strain enhances superconductivity, as observed in FeSe21. Later on, it was shown that substitution of Cu in the Fe plane can change the balance among electronic phases competing in FeSe at high pressure22. When an external magnetic field is absent at low hydrostatic pressures, the nematic and superconducting phases are suppressed similarly. However, at pressures above 10 kbar, the superconducting state remains unchanged, in spite of the absence of any signature in transport properties related to a magnetic phase in a zero-magnetic field22, while the effects of copper doping on the electronic structure of Fe1− xCuxSe have been studied by Huh et al. by means of ARPES23.

Due to the best authors’ knowledge, superconducting state parameters, such as Hc1, Hc2, coherence length λ, penetration depth ξ, superconducting carrier density ns, superconducting carrier effective mass ms*, and jc, of the restored Cu-doped superconductors were not determined yet. Knowledge of superconducting state properties can shed new light on the mechanisms leading to the appearance of superconductivity.

Taking the above into account, we have decided to study the influence of hydrostatic pressure on superconducting state properties of the Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.65Se0.35 single crystal and to perform a detailed examination of crystallographic structure changes when the recovery of superconductivity under hydrostatic pressure takes place. The evolution of crystallographic changes with pressure has been presented and structural transition under pressure in the investigated pressure range was excluded. The magnetic studies were concentrated on the research performed with a maximum pressure of 10 kbar available in our experimental setup, since the main aim of our work was to investigate the possibility of the reappearance of the pressure-induced superconducting state in the compound, which is non-superconducting at ambient pressure.

Details of synthesis and experiment

Details of the synthesis of Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.65Se0.35 single crystal were described in Ref15. The studied crystal was grown using the vertical Bridgman method. Stoichiometric amounts of iron chips (3N5), tellurium powder (4 N), selenium powder (pure) and CuSe (pure) were used to grow the crystals. These materials were weighed, mixed, and kept inside a glove box in an argon atmosphere. Evacuated sealed quartz ampoules with starting materials were placed in a furnace with an axial temperature gradient of 1.6 °C mm−1. The following thermal conditions of synthesis and crystal growth were applied: heating of the ingot for 3 h at 730 °C, then increasing the temperature to 920 °C. Afterward melting, a temperature of 730 °C was kept for 3 h; next, the samples were cooled down to 500 °C at a rate of 5 °C h−1, next to 200 °C at a rate of 60 °C h−1, and finally cooled down to room temperature15. The obtained single crystal exhibits well-developed (001) natural planes, equivalent to a cleavage plane of the PbO-type structure.

The quantitative point analysis on the cleavage planes of the studied single crystals was performed using a field emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM) JEOL JSM-7600 F (20 kV incident energy) coupled with the Oxford INCA energy dispersive x-ray spectroscope (EDX). SEM/EDX analysis indicated that the average chemical composition of the matrices of investigated crystals is Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34, with an accuracy of ± 0.02, and for the reference sample, it is Fe0.99Te0.66Se0.34, also with the same accuracy15. Later in the paper we will refer to the crystals’ average composition, not to the nominal one. Our earlier papers15,24 published all the details concerning the structure of the studied samples. One of the figures in Ref15 shows a photo of the Cu-substituted crystal with a composition similar to that studied here.

The magnetic measurements were performed, with magnetic fields up to 50 kOe, using a Quantum Design SQUID magnetometer. The magnetic field was oriented parallel to the c-axis of the crystal. Hydrostatic pressure was applied using an Almax-easyLab MCell10 cell with Daphne 7373 oil25, which is considered one of the best pressure media because of the minimal decrease in pressure (in a range above 7 kbar) with a lowering temperature26. As an in situ manometer, a high-purity Sn thin wire was used. The background signal of the pressure cell was subtracted, taking into account values measured under ambient pressure for the empty pressure cell. It turns out that the background contribution has a negligible impact on obtained results. Corrections for demagnetization were applied according to Ref27.

X-ray diffraction measurements of Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34 and Fe0.99Te0.66Se0.34 crystals were completed using Xcalibur S2 Agilent diffractometers with a monochromated Mo sealed tube source (Kα radiation, λ = 0.71073 Å) and a CCD detector. Crystals were placed in a modified Merrill–Bassett Diamond-Anvil Cell (DAC)28 with diamond anvils directly mounted on Inconel supports. The Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34 and Fe0.99Te0.66Se0.34 crystals were glued separately to the culet surface together with a small ruby chip29 and placed in a 0.3 mm diameter hole of a 0.1 mm thick tungsten gasket. The chamber was filled with silicon oil (hydrostatic pressure-transmitting medium) and closed. The semi-automatic gasket-shadowing method30 was applied for DAC centering along the x-ray beam. The CrysAlisPro program suite31 was used for collecting the data, determining the matrix orientation, and initial data reduction. The lattice parameters of Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34 and Fe0.99Te0.66Se0.34 under hydrostatic pressure were determined from single-crystal X-ray diffraction data collected for both compounds at 3.5, 7.2, and 10.7 kbar (Cu-doped material), and at 2.9, 7.3, and 11.3 kbar (undoped), respectively (Table 1). The analysis confirmed that both compounds maintain their characteristic tetragonal symmetry upon compression. The lattice constants a(= b) and c, as well as the unit cell volume, show a steady decrease with increasing pressure, indicating normal compressibility without any structural phase transition.

A slight increase in the a = b parameter observed in the Cu-doped crystal at an intermediate pressure likely reflects measurement uncertainties related to sample mosaicity and limited data points rather than evidence of negative area compressibility. With data for only three pressure values available, caution is warranted when interpreting subtle anomalies; however, the general trend of lattice contraction and symmetry retention is clear. These results provide valuable structural insight into how pressure affects the crystal framework, supporting the correlation between lattice parameter changes and the pressure-induced restoration of superconductivity discussed further in this work.

Results and discussion

Figure 1 presents the temperature dependence of the magnetic susceptibility, measured in both zero-field cooling (ZFC) and field cooling warming (FCW) mode, under ambient pressure and applied hydrostatic pressure of 10 kbar, in a dc field of 10 Oe, oriented parallel to the c-axis for Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34 and at ambient pressure for Fe0.99Te0.66Se0.34. The single crystal of Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34 at ambient pressure does not reveal any indications of superconducting phase transition down to 5 K. Under an applied hydrostatic pressure of 10 kbar, the investigated compound is clearly superconducting, with Tc equal to 13 K. The critical temperature was determined as the temperature at which the zero-field cooled magnetization MZFC(T) curve deviates from a temperature-independent, constant background value. This value of the critical temperature, obtained for Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34, under hydrostatic pressure, is comparable to that for Fe0.99Te0.66Se0.34 at ambient pressure (12.8 K, see, Table 2) and slightly higher than that for Fe0.994Ni0.007Te0.66Se0.34 at ambient pressure (12 K)14,15. The superconducting transition widths for Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34 (P = 10 kbar) and for Fe0.99Te0.66Se0.34 (at ambient pressure) are practically the same, evidenced by the nearly linear dependence of the ZFC magnetic susceptibility. The Meissner effect is not complete down to 5 K for the pressurized Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34, similarly to that of Fe0.99Te0.66Se0.34 at ambient pressure. The pressure-induced appearance of the superconducting transition temperature, observed for Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34, confirms our earlier reports13,14 about the possibility of an enhancement of Tc under hydrostatic pressure, previously suppressed by substitution of transition metal atoms into the Fe-site and changes in the Se/Te ratio15. The zero field-cooled magnetic susceptibility, equal to −0.88 at 5 K for Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34 under a pressure of 10 kbar, indicates recovery of bulk superconductivity; however, we should note that within our experimental accuracy of a few percent, a perfect Meissner effect was not observed at the temperature range far below Tc under applied pressure. Very pronounced differences between ZFC and FCW curves imply strong pinning properties of the studied crystals.

The critical temperature

In our previous studies32, we noted an excellent correlation between transition temperature determined from magnetic and transport measurements conducted on the undoped compound that is the focus of the current research.

Basic parameters describing superconducting state—the upper and the lower critical fields

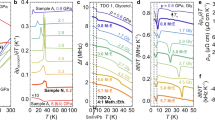

We have conducted magnetic studies under pressure on the lower and the upper critical fields, as well as the critical current density, to determine whether the trend of Tc recovery can be observed in other parameters of the superconducting state. To estimate the thermodynamic parameters of a single crystal of Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34, subjected to hydrostatic pressure, and to compare them with those of Fe0.99Te0.66Se0.34 (see, Ref14., we have estimated the temperature dependence of the upper and the lower critical fields in H || c-axis geometry (up to 50 kOe), for Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34, subjected to hydrostatic pressure of 10 kbar, and for Fe0.99Te0.66Se0.34 under ambient pressure and at applied hydrostatic pressure of 9.8 kbar. Figure 2(a) presents the temperature dependence of the magnetic moment, m, measured under 10 kbar hydrostatic pressure for several magnetic fields in the geometry H || c-axis for Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34. From these data, characteristic temperature Tc2(H = const.) was determined as the temperature at which m(T) deviates from linear temperature dependence, describing well normal state magnetic susceptibility. Using the Tc2(H) data from several magnetic fields, we were able to plot Hc2(T) dependence for the studied sample along the c-axis at a hydrostatic pressure of 10 kbar. From measurements of H||cc2, one can derive the coherence length, ξab, using the following formula:

(a) Temperature dependence of magnetic moment, measured for Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34 in the vicinity and above Tc, under an applied hydrostatic pressure of 10 kbar, shown for selected magnetic fields for H || c-axis. Inset shows raw magnetic data for all magnetic fields. (b) Temperature dependence of the upper critical field, for H || c-axis, for Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34 under applied hydrostatic pressure of 10 kbar, and for Fe0.99Te0.66Se0.34 under ambient pressure and hydrostatic pressure of 9.8 kbar.

where Φ0 is flux quantum. The same procedure was applied for processing experimental data for Fe0.99Te0.66Se0.34 under ambient pressure and at an applied hydrostatic pressure of 9.8 kbar.

Figure 2(b) shows the temperature dependence of the upper critical field for H || c-axis (H||cc2) for pressurized Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34 and for Fe0.99Te0.66Se0.34 at ambient pressure and under a hydrostatic pressure. The upper critical field values for Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34, within the range of 0–50 kOe, are slightly lower than those for Fe0.99Te0.66Se0.34 at ambient pressure (Fig. 2b). A more detailed description of the temperature dependence of the upper critical field for Fe0.99Te0.66Se0.34 at ambient pressure and at an applied pressure of 9.8 kOe is given in Ref14. For Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34, higher magnetic fields show an apparent increase in the −dH||cc2/dT slope in the linear part of the H||cc2(0) dependence. At lower fields, in the vicinity of Tc, strong curvature is observed. In the field range 10–50 kOe, we have −dH||cc2/dT = 32(3) kOe/K. This value is much larger than that for Fe0.99Te0.66Se0.34 determined at ambient and under hydrostatic pressure of 9.8 kbar (see, Table 2). Moreover, it is also larger than that noticed for a single crystal of FeTe0.5Se0.5 with a wider transition to a superconducting state13. Furthermore, for FeTe0.5Se0.5, the same shape of H||cc2(0) dependence was observed, which features a strong curvature near Tc and a significant increase in slope −dH||cc2/dT in the linear part of H||cc2(T); this behavior was attributed to the multiband nature of superconductivity13. We have determined the value of H||cc2 at 0 K for Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34, using the Werthamer-Hefland-Hohenberg approach33. According to that method, one can assume that the Hc2(0) value is proportional to Tc and to –dHc2/dT, determined in a relatively wide magnetic field range above the strong curvature of Hc2(T) near Tc. This equation indicates the value of H||cc2(0) equal to 300(40) kOe for Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34 under hydrostatic pressure of 10 kbar. Using the value of H||cc2(0), we estimate the zero-temperature coherence length ξab(0) of 3.3 nm. The upper critical field at 0 K for Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34, under P = 10 kbar, equal to 300(40) kOe (Table 2), is slightly larger than that for Fe0.99Te0.66Se0.34 under P = 9.8 kbar, equal to 240(10) kOe (Table 2). Since the coherence length is proportional to the velocity at the Fermi level and inversely proportional to Tc, according to the relation34:

In this context, νF represents the velocity at the Fermi level, and the parameter a, which was empirically determined by Pippard, is equal to 0.1534. The smaller value of ξab(0) for Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34, measured under P = 10 kbar and with a lower Tc (= 13.0 K) compared to Fe0.99Te0.66Se0.34 under P = 9.8 kbar (Tc = 17.6 K), suggests that νF is smaller for Cu-substituted Fe-Se-Te than for the parent compound. Thus, one can speculate that the decrease of velocity at the Fermi level caused by Cu substitution for Fe-Se-Te is correlated with the disappearance of superconductivity.

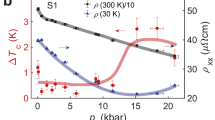

The lower critical field Hc1 was estimated according to the procedure basing on the Bean’s critical-state model to catch the beginning of flux penetration in broad range of ZFC magnetization curves, as it was introduced in35 and discussed in13,36. The dependence of magnetic moment on field was measured at various temperatures for magnetic field parallel to the c-axis of the crystal. For a given shape of the investigated crystal, the demagnetizing factor D was calculated to correct the values of the external magnetic field. The variation of the square root of a product of magnetic induction B = 4πm/V + Hint and volume of the studied crystal V as a function of the internal magnetic field Hint = Hext − DM (Hext denotes the external magnetic field) for Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34 under 10 kbar at 2 K is presented in the inset of Fig. 3(a). The lower critical field values Hc1(T) for H parallel to the c-axis for Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34 under 10 kbar and for Fe0.99Te0.66Se0.34 at ambient pressure and at an applied pressure of 9.8 kOe, presented in Fig. 3(a), were determined as the magnetic field H for which the value of (BV)1/2 plotted as a function of H at fixed T deviates from zero.

(a) Temperature dependence of Hc1 for Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34 under applied hydrostatic pressure of 10 kbar and for Fe0.99Te0.66Se0.34 under ambient pressure and hydrostatic pressure of 9.8 kbar for H || c-axis. Raw magnetic data for Cu-substituted sample was shown in the left inset. The right inset presents (BV)1/2 versus the internal magnetic field, Hint, determined at 2 K at hydrostatic pressure of 10 kbar, for Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34 for H || c-axis. (b) The lower critical field reduced temperature dependence at ambient pressure and under an applied hydrostatic pressure for H || c-axis.

One can noticed that a simpler and more common method to determine Hc1 is to track the point where the magnetic moment deviates from the linear diamagnetic response during the initial application of the external magnetic field in hysteresis loop measurements (see, for example37). The left inset of Fig. 3(a) presents the data obtained with this method. These two methods yield essentially the same Hc1 value; however, an error bar in the method using the Bean’s critical-state model appears to be smaller.

The reduced temperature dependence of Hc1 for H || c-axis (H||cc1), determined for Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34 under hydrostatic pressure of 10 kbar and for Fe0.99Te0.66Se0.34 at ambient pressure and under hydrostatic pressure of 9.8 kbar, is presented in Fig. 3(b). The Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34 sample, at non-zero temperatures, under hydrostatic pressure of 10 kbar, is characterized by smaller values of Hc1 when compared to Fe0.99Te0.66Se0.34 at ambient pressure. The result indicates a smaller value of the penetration depth for Fe0.99Te0.66Se0.34 and the superconducting carrier density for Fe0.99Te0.66Se0.34 at ambient pressure is larger than that of Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34 under hydrostatic pressure of 10 kbar. For Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34, from the data presented in Fig. 3, the extrapolated zero-temperature value of Hc1 was found to be H||cc1(0) = 37(5) Oe for P = 10 kbar (Table 2). This value is practically the same, within the experimental error, as the value of H||cc1(0) for Fe0.99Te0.66Se0.34, determined at ambient pressure. However, it should be noted that the zero-temperature value H||cc1(0) = 40(5) Oe for Fe0.99Te0.66Se0.34 at ambient pressure increases to H||cc1(0) = 190(10) Oe under a pressure of 9.8 kbar, which is five times bigger than that of Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34 for P = 10 kbar. The values of the magnetic penetration depth were extracted from the measured values of Hc1, following the basic relation38:

Here, λab denotes the magnetic penetration depth associated with the superconducting current flowing in the ab-plane, and κ||c = λab/ξab is the Ginzburg–Landau parameter. The coherence length at 0 K, ξab(0), was determined by extrapolating the value of H||cc2 to zero temperature for H || c-axis. The zero-temperature value of the magnetic penetration depths, λab(0), for pressurized Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34, equals to 495(55) nm, which is comparable to that for Fe0.99Te0.66Se0.34 at ambient pressure (455(15) nm, see, Table 2). Here again, λab(0) for Fe0.99Te0.66Se0.34 at ambient pressure decreases to 200(20) nm under a pressure of 9.8 kbar, which is about 44% of the ambient pressure value. The above similarity together with almost identical transition temperature to superconducting state indicate that an empirical relation between the zero-temperature superfluid density ρs(0) ∝ λab−2(0) and Tc is here the same as the generic for various cuprate high-Tc superconductors (Uemura plot)39. The obtained results, when correlated with those reported previously for FeTe0.5Se0.513 and Fe0.994Ni0.007Te0.66Se0.3414, show that the application of hydrostatic pressure improves the superconducting properties in the Fe-Te-Se family, originally weakened due to substitutions at the Fe-site and changes in the Se/Te ratio15.

Penetration depth within the clean-limit approximation is described by the following formula40:

In this context, ns represents the superconducting carrier density, while ms* denotes the effective mass of the superconducting carriers. The Fermi temperature for a free electron gas in three dimensions is given by the following formula41,42,43:

In this context, m* represents the carrier effective mass, while n denotes the carrier density. For the Fe-Te-Se system, which is a superconductor with low anisotropy, we can reasonably assume that the superconducting effective mass, ms*, is well approximated by the ab-plane value of effective mass, mab*. Thus, the velocity at the Fermi surface νF in the ab-plane can be approximated by:

Combining Eqs. (2), (4), and (6) one can independently estimate superconducting carrier density and effective mass concentration. Obtained results are presented in Table 2. The most important achievements can be summarized as follows:

-

superconducting carrier density for Fe0.99Te0.66Se0.34 significantly increases with increasing Tc under applied hydrostatic pressure,

-

the superconducting carrier density value for Fe0.99Te0.66Se0.34 under ambient pressure with Tc = 12.8 K is very similar to that of pressurized Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34, which has an almost identical Tc = 13 K,

-

superconducting effective mass under applied pressure for both studied samples is higher than that at ambient pressure.

The obtained results can be explained consistently if one assumes that applied pressure leads to an increase in structural disorder in the studied material, which in turn causes an increase in the superconducting carrier’s effective mass and density. The increase of the effective mass depends on the disorder introduced to the studied material only and therefore is similar for various materials subjected to very similar applied pressure. Assuming a similar increase of superconducting carrier density under pressure, one can expect that both the actual ns value under pressure as well as Tc depend on the starting value of superconducting carrier density at ambient pressure.

The critical current density

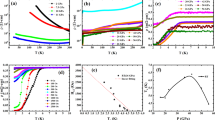

The critical current density was determined from M(H) dependences (see, Fig. 4), carried out for selected reduced temperatures, at ambient pressure and at non-zero hydrostatic pressure, using Bean’s model44,45. The following formula:

was applied to determine the critical current density, jcab46,47. Here, ΔM (in oersteds) is the width of the hysteresis loop for decreasing and increasing Hint (see, Fig. 4), a = 0.15 cm and b = 0.115 cm are the sample dimensions for Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34 in the plane perpendicular to the external magnetic field, and the units of current densities are A/cm2. Figure 5 shows how the critical current density depends on the magnetic field for both pressurized Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34 and Fe0.99Te0.66Se0.34 at ambient pressure, as well as under hydrostatic pressure; these values were calculated according to Eq. (7) at a reduced temperature of about 0.39Tc with the magnetic field orientated parallel to the c-axis. We note a larger value of the estimated critical current density for Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34 for P = 10 kbar, as compared to that for Fe0.99Te0.66Se0.34 at ambient pressure. The observed increase in jc one can attribute to the increasing effectiveness of small-sized defects present in the crystal. This improvement occurs because of two reasons: (1) a diminution of the coherence length under pressure and (2) an enhancement of the thermodynamic critical field under pressure due to the upper critical field increase.

Dependence of magnetization on magnetic field recorded at 5 K and at 6.8 K (comparable reduced temperature) for Fe0.99Te0.66Se0.34 at ambient pressure and under a hydrostatic pressure of 9.8 kbar, respectively, and for Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34 at ambient pressure and under a hydrostatic pressure of 10 kbar, recorded at 5 K. The inset shows raw magnetic data recorded as a function of an applied magnetic field.

Magnetic field dependence of the critical current density for Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34 under hydrostatic pressure of 10 kbar (Tc = 13.0 K) and for Fe0.99Te0.66Se0.34 at ambient pressure (Tc = 12.8 K) and under a hydrostatic pressure of 9.8 kbar (Tc = 17.6 K), for H || c-axis, at a reduced temperature of about 0.39Tc.

X-ray diffraction studies

The crystal structure of Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34 was identified as that of the anti-PbO type, but the quality of data was insufficient for determination of structure details. Confirmation of this phase is in agreement with the results of studies using x-ray diffraction48,49 and other methods50,51,52, confirming that the anti-PbO phase is stable in compounds with close chemical composition at pressures up to at least ∼11 kbar.

A series of high-pressure single crystal diffraction experiments were performed within DAC using an Oxford Diffraction Xcalibur Eos diffractometer on single crystals of Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34 and Fe0.99Te0.66Se0.34, glued to the culet surface of a diamond anvil and filled with silicon oil used as a hydrostatic medium. The DAC was centered on the diffractometer using the semiautomatic gasket-shadow procedure.

With increasing pressure one can noticed that the shape of diffraction spots changed: roughly circular spots turn into extended one along a direction agreeing with the run of Debye–Scherrer rings (see, Figs. 6 and 7), which is in our opinion caused by pressure-induced increase of mosaicity of the sample. For the diffraction-spot shape analysis the strong \(\:\stackrel{-}{1}\)01 (Figs. 8 and 9) and 10\(\:\stackrel{-}{1}\) reflections (Figs. 10 and 11) were selected. The quoted reflection extension was calculated, with use of contour maps (see, Figs. 8, 10, 9 and 11) at the level of 50% of peak height. We found that in the radial direction there is no peak broadening, showing that pressure has insignificant impact on chemical homogeneity of the studied crystal.

h0l layer of Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34 crystal measured at room temperature at 3.5, 7.2, and 10.7 kbar, respectively (from left to right). All data presented in the above panel were obtained for the same crystal (with the same orientation matrix) enclosed in a modified Merrill–Bassett Diamond-Anvil Cell.

10\(\:\stackrel{-}{1}\) reflection profile and contour maps of Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34 crystal measured at room temperature at 3.5, 7.2, and 10.7 kbar. The intensity scales are shown separately for each pressure points as insets. The subsequent degradation of the reflection profile and its elongation observed upon compression indicates that the crystal quality becomes inferior.

10\(\:\stackrel{-}{1}\) reflection profile and contour maps measured at room temperature at 2.9, 7.3, and 11.3 kbar for Fe0.99Te0.66Se0.34 crystal. As previously, the intensity scales are shown separately for each pressure points as insets. The crystal quality becomes inferior between 7.3 and 11.3 kbar.

We have observed that the diffraction quality of the Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34 crystal deteriorates with increasing pressure, which made reliable structure refinement and precise determination of atomic positions impossible, despite the absence of a structural phase transition under the applied pressure.

In the studied Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34 crystal, structural disorder is manifested primarily as increased mosaicity and broadening of diffraction spots under pressure. These features signal enhanced local distortions, atomic site disorder, and microstrain, which have been shown in iron chalcogenide superconductors to substantially modify their electronic and magnetic ground states. Specifically, our data indicate that the application of pressure does not induce a symmetry change but increases the degree of disorder at the microscopic level. This effect is revealed by the pressure-dependent broadening and stretching of diffraction spots and the inability to achieve precise atomic coordinates at high pressure, even though the powder patterns remain characteristic of the tetragonal symmetry. Such enhanced disorder is widely considered to affect local charge carrier density, suppress long-range magnetic order, and facilitate superconducting pairing in these materials. The positive impact of these nano- and microscale inhomogeneities in restoring superconductivity is supported not only by our results where critical current density and upper critical field are also enhanced under pressure but also by literature on iron chalcogenides and analogous systems. These studies emphasize that the interplay of disorder and electronic structure can stabilize superconductivity through the enhancement of local electronic correlations and modifications to Fermi surface topology. In summary, structural disorder under pressure promotes the emergence of superconductivity in Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34 by increasing electronic inhomogeneity and disrupting magnetic order, providing favorable conditions for Cooper pairing as reflected in enhanced superconducting and transport parameters.

Conclusions

In this work, we have studied single crystals of Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34 and Fe0.99Te0.66Se0.34 at ambient pressure and under hydrostatic pressure up to 11.3 kbar to reveal the impact of pressure on the basic parameters describing the superconducting state and on crystallographic structure changes. We have found that under hydrostatic pressure of 10 kbar, the Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34 compound, which is non-superconducting at ambient pressure down to 5 K, becomes superconducting with Tc = 13 K. This value is practically the same as for Fe0.99Te0.66Se0.34 at ambient pressure (12.8 K). The other investigated parameters of the superconducting state for Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34, including the lower and the upper critical fields, coherence length, and penetration depth, were found to be comparable to those reported for Fe0.99Te0.66Se0.34 at ambient pressure, particularly at temperatures close to 0 K. The observed increase in superconducting carrier density and effective mass under pressure can be explained if one assumes that applied pressure leads to an increase in structural disorder in the studied material. The critical current density was found to be larger for Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34, for P = 10 kbar than that for Fe0.99Te0.66Se0.34 at ambient pressure. Comparing the pressure effect on the superconducting properties of different substitutions at the Fe-site and changes in the Se/Te ratio, one can see the same trend based on an improvement of the superconducting state parameters under hydrostatic pressure, which were suppressed at ambient pressure by chemical modifications.

In conclusion, we observed that under pressure, the Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34 crystal shows increased structural disorder, visible as broader and more diffuse diffraction spots. Despite this, the overall tetragonal symmetry remains unchanged. This increased disorder appears to weaken magnetic ordering and cause local fluctuations in the electronic environment. Similar effects in related iron-based superconductors likely contribute to the restoration of superconductivity by enabling electron pairing. Supporting this idea, we observe that superconducting properties like the critical current density improve alongside these structural changes. Therefore, rather than harming superconductivity, the disorder created under pressure seems to play an important role in reactivating it in this Cu-doped material.

Hence, the observed variation in diffraction-spot shape for Fe0.975Cu0.025Te0.66Se0.34 under pressure may correlate with the enhancement of superconductive properties, which we attribute to an increase in mosaicity. The increase in mosaicity may explain the earlier observation of superconducting property variation in related sulpho-iron seleno-tellurides of anti-PbO-type structure. After lowering pressure to ambient one, all of the crystals’ parameters recovered ambient pressure values.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during this study are available on reasonable request. If anyone would like to request the data from magnetic measurements, please contact corresponding author. If anyone would like to request X-ray diffraction data, please contact D. Paliwoda (e-mail: damian.paliwoda@ess.eu).

References

Hsu, F. C. et al. Superconductivity in the PbO-type structure α-FeSe. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 14262. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0807325105 (2008).

Fang, M. H. et al. Superconductivity close to magnetic instability in Fe(Se1 – xTex)0.82. Phys. Rev. B. 78, 224503. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.78.224503 (2008).

Bao, W. et al. Tunable (δπ,δπ)-type antiferromagnetic order in α-Fe(Te,Se) superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 247001. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.247001 (2009).

Yeh, K. W. et al. Tellurium substitution effect on superconductivity of the α-phase iron Selenide. Eur. Phys. Lett. 84, 37002. https://doi.org/10.1209/0295-5075/84/37002 (2008).

Khasanov, R. et al. Coexistence of incommensurate magnetism and superconductivity in Fe1+ ySexTe1–x. Phys. Rev. B. 80, 140511. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.80.140511 (2009).

Hunte, F. et al. Two-band superconductivity in LaFeAsO0.89F0.11 at very high magnetic fields. Nature 453, 903. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature07058 (2008).

Yamamoto, A. et al. Small anisotropy, weak thermal fluctuations, and high magnetic field superconductivity in Co-doped iron pnictide Ba(Fe1 – xCox)2As2. Appl. Phys. Lett. 94, 062511. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3081455 (2009).

Khim, S. et al. Evidence for dominant Pauli paramagnetic effect in the upper critical field in single-crystalline FeTe0.6Se0.4. Phys. Rev. B. 81, 184511. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.81.184511 (2010).

Si, W. et al. Iron-chalcogenide FeSe0.5Te0.5 coated superconducting tapes for high field applications. Appl. Phys. Lett. 98, 262509. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3606557 (2011).

Mizuguchi, Y. et al. Fabrication of iron-based superconducting wire using Fe(Se,Te). Appl. Phys. Express. 2, 083004. https://doi.org/10.1143/APEX.2.083004 (2009).

Mele, P. Superconducting properties of iron chalcogenide thin films. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 13, 054301. https://doi.org/10.1088/1468-6996/13/5/054301 (2012).

Ozaki, T., Deguchi, K., Mizuguchi, Y., Kumakura, H. & Takano, Y. Transport properties of iron-based FeTe0.5Se0.5 superconducting wire. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 21, 2858. https://doi.org/10.1109/TASC.2010.2086031 (2011).

Pietosa, J. et al. Pressure-induced enhancement of the superconducting properties of single-crystalline FeTe0.5Se0.5. J. Phys. : Condens. Matter. 24, 265701. https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-8984/24/26/265701 (2012).

Pietosa, J. et al. Enhancement of superconducting state properties of Fe0.994Ni0.007Te0.66Se0.34 single crystal with increasing pressure: a correlation with pressure-induced crystallinity degradation. Supercond Sci. Technol. 33, 045004. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6668/ab6dc4 (2020).

Gawryluk, D. J. et al. Growth conditions, structure and superconductivity of pure and metal-doped FeTe1 – xSex single crystals. Supercond Sci. Technol. 24, 065011. https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-2048/24/6/065011 (2011).

Bezusyy, V. L., Gawryluk, D. J., Berkowski, M. & Cieplak, M. Z. Doping effects of Co, Ni, and Cu in FeTe0.65Se0.35 single crystals. Acta Phys. Pol. A. 121, 816. https://doi.org/10.12693/APhysPolA.121.816 (2012).

Bezusyy, V. L., Gawryluk, D. J., Malinowski, A., Berkowski, M. & Cieplak, M. Z. Influence of iron substitutions on the transport properties of FeTe0.65Se0.35 single crystals. Acta Phys. Pol. A. 126, 76. https://doi.org/10.12693/APhysPolA.126.A-76 (2014).

Bezusyy, V. L., Gawryluk, D. J., Malinowski, A. & Cieplak, M. Z. Transition-metal substitutions in iron chalcogenides. Phys. Rev. B 91, 100502(R). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.91.100502 (2015).

Schoop, L. M. et al. Pressure-restored superconductivity in Cu-substituted fese. Phys. Rev. B. 84, 174505. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.84.174505 (2011).

Alireza, P. et al. Superconductivity up to 29 K in SrFe2As2 and BaFe2As2 at high pressures. J. Phys. : Condens. Matter. 21, 012208. https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-8984/21/1/012208 (2009).

Zajicek, Z. et al. Drastic effect on impurity scattering on the electronic and superconducting properties of Cu-doped fese. Phys. Rev. B. 105, 115130. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.105.115130 (2022).

Zajicek, Z., Singh, S. J. & Coldea, A. I. Robust superconductivity and fragile magnetism induced by the strong Cu impurity scattering in the high-pressure phase of fese. Phys. Rev. Res. 4, 043123. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevResearch.4.043123 (2022).

Huh, S. et al. Cu doping effects on the electronic structure of Fe1 – xCuxSe. Phys. Rev. B. 105, 245140. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.105.245140 (2022).

Wittlin, A. et al. Microstructural magnetic phases in superconducting FeTe0.65Se0.35. Supercond Sci. Technol. 25, 065019. https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-2048/25/6/065019 (2012).

Murata, K., Yoshino, H., Yadav, H. O., Honda, Y. & Shirakava, N. Pt resistor thermometry and pressure calibration in a clamped pressure cell with the medium, Daphne 7373. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 68, 2490. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1148145 (1997).

Kamarad, J., Machatova, A. & Arnold, Z. High pressure cells for magnetic measurements – Destruction and functional tests. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 75, 5022. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1808122 (2004).

Prozorov, R. & Kogan, V. G. Effective demagnetizing factors of diamagnetic samples of various shapes. Phys. Rev. Appl. 10, 014030. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevApplied.10.014030 (2018).

Merrill, L. & Bassett, W. A. Miniature diamond anvil pressure cell for single crystal x-ray diffraction studies. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 45, 290. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1686607 (1974).

Ruby fluorescence is a standard and reliable method for pressure calibration in. diamond anvil cells at moderate pressure ranges, and its calibration is consistent with other well-known pressure gauges within a relative uncertainty of ± 2.5% (Shen, G. et al. Toward an international practical pressure scale: A proposal for an IPPS ruby gauge (IPPS-Ruby High Pressure Research 40(3), 299–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/08957959.2020.1791107 (2020)). In the ruby fluorescence method, the pressure calibration is based on the wavelength shift of the R1 fluorescence line from ruby and is accurate to within approximately ± 0.1 to ± 0.3 kbar (about 1–3%) in the pressure range between atmospheric and 120 kbar. Accuracy of measurement depends on maintaining hydrostatic conditions and proper calibration but is sufficient for typical crystallographic studies at this pressure range.

Katrusiak, A. Shadowing and absorption corrections of single-crystal high-pressure data. Z. Kristallogr. 219, 461. https://doi.org/10.1524/zkri.219.8.461.38328 (2004).

Rigaku Oxford Diffraction, CrysAlisPro Software System (Yarnton, England, 2015).

Sivakov, A. G. et al. Microstructural and transport properties of superconducting FeTe0.65Se0.35 crystals. Supercond Sci. Technol. 30, 015018. https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-2048/30/1/015018 (2017).

Werthamer, N. R., Hefland, E. & Hohenberg, P. C. Temperature and purity dependence of the superconducting critical field, Hc2. III. Electron spin and spin-orbit effects. Phys. Rev. 147, 295. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.147.295 (1966).

Chandrasekhar, B. S. In Superconductivity (Ed. Parks, R. D.) 1 (Marcel Dekker, New York, 1969).

Naito, M. et al. Temperature dependence of anisotropic lower critical fields in (La1-xSrx)2CuO4. Phys. Rev. B. 41, 4823. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.41.4823 (1990).

Bendele, M. et al. Anisotropic superconducting properties of single-crystalline FeSe0.5Te0.5. Phys. Rev. B. 81, 224520. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.81.224520 (2010).

Ren, C. et al. Temperature dependence of the lower critical field Hc1 in SmFeAsO0.9F0.1 and Ba0.6K0.4Fe2As2 iron-arsenide superconductors. Phys. C. 469, 599–605. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physc.2009.03.015 (2009).

Tinkham, M. Introduction to superconductivity (Malabar, FL, Klieger, 1975).

Uemura, Y. J. et al. Universal correlations between Tc and ns/m* (carrier density over effective mass) in high-Tc cuprate superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 62, 2317. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.62.2317 (1989).

de Gennes, P. G. Superconductivity of metals and alloys (Benjamin, New York, 1966).

Uemura, Y. J. et al. Basic similarities among cuprate, bismuthate, organic, Chevrel-phase, and heavy-fermion superconductors shown by penetration-depth measurements. Phys. Rev. Lett. 66, 2665. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.66.2665 (1991).

Uemura, Y. J. Classifying superconductors in a plot of Tc versus Fermi temperature TF. Phys. C 185–189, 733. https://doi.org/10.1016/0921-4534(91)91590-Z (1991).

Harshman, D. R. & Mills, A. P. Jr. Concerning the nature of high-T, superconductivity: survey of experimental properties and implications for interlayer coupling. Phys. Rev. B. 45, 10684. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.45.10684 (1992).

Bean, C. P. Magnetization of hard superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 8, 250. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.8.250 (1962).

Bean, C. P. Magnetization in high-field superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 36, 31. https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.36.31 (1964).

Gyorgy, E. M., van Dover, R. B., Jackson, K. A., Schneemeyer, L. F. & Waszczak, J. V. Anisotropic critical currents Ba2Y3CuO7 analyzed using an extended bean model. Appl. Phys. Lett. 55, 283. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.102387 (1989).

Wiesinger, H. P., Sauerzopf, F. M. & Weber, H. W. On the calculation of Jc from magnetization measurements of superconductors. Phys. C. 203, 121. https://doi.org/10.1016/0921-4534(92)90517-G (1992).

Gresty, N. C. et al. Structural phase transitions and superconductivity in Fe1+δSe0.57Te0.43 at ambient and elevated pressures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 16944. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja907345x (2009).

Malavi, P. S., Karmakar, S., Patel, N. N., Bhatt, H. & Sharma, S. M. Structural and optical investigations of Fe1.03Se0.5Te0.5 under high pressure. J. Phys. : Condens. Matter. 26, 125701. https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-8984/26/12/125701 (2014).

Bendele, M. et al. Effect of pressure-driven local structural rearrangement on the superconducting properties of FeSe0.5Te0.5. Phys. Rev. B. 90, 174505. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.90.174505 (2014).

Jha, R., Zargar, R. A., Hafiz, A. K., Kishan, H. & Awana, V. P. S. Superconductivity at 25 K under hydrostatic pressure for FeTe0.5Se0.5 superconductor. J. Supercond Nov Magn. 27, 1599. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10948-014-2559-3 (2014).

Shylin, S. I. et al. Pressure effect on superconductivity in FeSe0.5Te0.5. Phys. Status Solidi B. 254, 1600161. https://doi.org/10.1002/pssb.201600161 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This research was partially supported by the National Science Centre of Poland, with additional funding provided to DP through the Miniatura grant (decision No. 2018/02/X/ST3/02880).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J. Piętosa – magnetic measurements under pressure, data collection and initial article writing, preparation of Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5; Table 2. D. Paliwoda, A. Katrusiak – X ray diffraction studies, data collection and analysis, writing final version of the manuscript, preparation of Figs. 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 and 11 and Table 1. D. J. Gawryluk – synthesis of the investigated material. R. Puźniak, A. Wiśniewski – conceptualization, guidance and supervision, review of results and writing final version of the manuscript. All the authors reviewed the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pietosa, J., Puzniak, R., Paliwoda, D. et al. Superconducting state properties of Cu-substituted Fe0.99Te0.66Se0.34 exhibiting superconductivity recovered under hydrostatic pressure. Sci Rep 15, 40940 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24806-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24806-x