Abstract

In this study, three imidazole derivatives : 2,4,5-triphenyl-1-(4-(phenyldiazenyl)phenyl)-1 H-imidazole (N1), 2-(4-chlorophenyl)-4,5-diphenyl-1-(4-(phenyldiazenyl)phenyl)-1 H-imidazole (N2), and 2-(2,4-dichlorophenyl)-4,5-diphenyl-1-(4-(phenyldiazenyl)phenyl)phenyl)-1 H-imidazole (N3), which were prepared using N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone hydrogen sulfate ionic liquid as a catalyst, were selected for detailed evaluation. The antimicrobial activities of these compounds were assessed against a panel of pathogenic microorganisms, including Gram-positive bacteria (Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus anthracoides), Gram-negative bacteria (Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae), and the fungal strain Candida albicans. The Density Functional Theory (DFT) results showed that the N3 molecule exhibited the highest stability with the largest ΔEgap (2.9546 eV) and chemical hardness, while N1 showed the highest reactivity. Frontier molecular orbital (FMO) and electrostatic potential (ESP) analyses revealed that the HOMO orbitals are delocalized over the imidazole ring and neighboring aromatic fragments, and the LUMO orbitals are spread over the phenyldiazenyl phenyl fragments. A comparative analysis suggests that while N3 is the most chemically stable, N2 demonstrates the highest potential for biological activity, consistent with experimental antimicrobial results. Both in-vitro and in-silico results revealed that the N2 molecule exhibits superior biological activity compared to N1 and N3. Molecular docking studies of N2 were performed with its target protein to explore its binding interactions with several amino acid residues, elucidating its potential antioxidant mechanism. Docking results revealed that all ligands exhibit strong binding affinities, with N1 showing the highest MolDock score and N2 demonstrating strong specificity through key hydrogen bonding and π-interactions. Molecular dynamics simulations, including RMSD, RMSF, radius of gyration (Rg), solvent-accessible surface area (SASA), and principal component analysis (PCA), further confirmed the structural stability and dynamic behavior of the protein-ligand complexes. MMPBSA binding free energy calculations indicated that N2@1AI9 forms the most stable complex, primarily driven by favorable van der Waals and electrostatic interactions. In silico ADMET analysis suggests all compounds, particularly the lead compound N2, face challenges with high lipophilicity, low solubility, and predicted drug-drug interaction risk (CYP2C19 inhibition for all; CYP3A4 and P-gp substrate for N2), yet their lack of BBB permeation supports their further development, especially for topical or intravenous use. Overall, the results suggest that N2 is a promising candidate for further development as a potential antimicrobial anti-fungal agent targeting the ergosterol biosynthesis pathway in Candida albicans.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

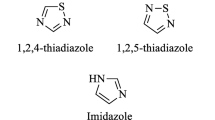

Imidazoles are of great importance in pharmacology owing to their high biological activity. These therapeutic effects make them useful for the preparation of anti-microbial, anti-allergic, anti-inflammatory, anti-cancer, anti-HIV, antioxidant, and analgesic products, etc1,2,3,4,5,6,7. This property of imidazoles has also been used to prevent microbiological corrosion8.

The imidazole nucleus presents in as a component of histidine, DNA, vitamin B12, purines, histamine, and biotin. It is also included in the structure of many natural or synthetic drugs such as cimetidine, clemizole, azomycin, nocodazole, dacarbazine, etonitazene, megazol, enviroxime, nitroso imidazole, and metronidazole2,9. The exploration of new biologically active imidazole derivatives is an area of intensive research in medicinal chemistry.

Quantum mechanical calculations, which have become an efficient and straightforward approach in recent years, make it feasible to theoretically investigate and provide property approximations of new compounds in a short time in comparison to expensive and time-constrained experimental procedures. It is possible to study important molecular orbital parameters, such as the energy of the highest occupied molecular orbital (EHOMO), the energy of the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (ELUMO), the valence band energy gap (ΔEgap), chemical hardness, chemical softness, electronegativity, chemical potential, electrophilicity index, ionization potential, and electron affinity, along with bond lengths and angle degrees with quantum chemical calculations. High stability is indicated by a high ΔEgap value. High chemical hardness and low chemical softness values are correlated with low reactivity and binding efficacy10,11,12. Electronegativity is related to electron attraction and reactivity. The high value of chemical potential (less negativity) means it is easier to donate electrons (electron donor), while a low value of chemical potential (more negative) means it is easier to accept electrons (electron acceptor). The negative chemical potential is indicative that the compound does not undergo decomposition into elements13. Electrophilicity is a predictor for the electrophilic nature of a chemical species; it measures the propensity of a molecule to accept an electron, with high values of electrophilicity characterizing superior electrophilicity in a molecule. Electrophilicity is also related to the biological activity of the substance14. The organic compounds are ranked in order of electrophilicity as follows; weak electrophiles have electrophilicity less than 0.8 eV, moderate electrophiles have electrophilicity in a range between 0.8 and 1.5 eV, and strong electrophiles have electrophilicity greater than 1.5 eV. It is common knowledge that drugs with a high electrophilic nature have potent antimicrobial and anticancer properties. Ionization potential is the energy required to remove an electron. On the other hand, a high ionization energy value denotes chemical stability15,16.

Some tetrasubstituted phenanthroimidazoles were synthesized in the presence of an ionic liquid catalyst. The catalytic effects of ionic liquid are determined and described in the optimized transition state structures. The HOMO and LUMO energy gap for 2-phenyl-1-(4-(phenyldiazenyl)phenyl)−1 H-phenanthro[9,10-d]imidazole was calculated to be 2.41 eV that confirms the stability of the synthesized imidazole derivatives17. In another source, imidazoles containing a ketone functional group were synthesized, and theoretical calculations were performed. The electrophilicity index of the compounds was calculated between 4.630 and 5.417 eV, which determines the biological activity of the compounds18.

One of the applications of imidazoles is in the field of drug design, where they can act as inhibitors or modulators of various enzymes and receptors19,20,21. For example, imidazole derivatives can inhibit sirtuins, a family of epigenetic enzymes that regulate cellular processes by removing acetyl groups from proteins. Sirtuins are involved in aging, metabolism, inflammation, and cancer and have been considered as potential therapeutic targets22. Another example is the inhibition of p38 MAP kinase, a protein kinase that mediates inflammatory and stress responses. P38MAP kinase is implicated in various diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, neurodegeneration, and COVID-19. Imidazole derivatives can interact with the ATP-binding site of p38 MAP kinase and block its activity22,23.

To design and evaluate imidazole derivatives as potential drugs, various computational and experimental methods can be used. Density functional theory can be used to calculate the electronic structure and energy of the molecules. ADME (absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion) analysis can be used to assess the pharmacokinetic profile and drug-likeness of the compounds21,24,25,26. In vitro methods involve the use of laboratory techniques and assays to test the biological activity and toxicity of the compounds26,27,28. Using hybrid in-silico and in-vitro methods, imidazole derivatives can be synthesized, screened, and optimized as potential drugs for various applications. This approach requires further attention to fulfill the existing research gap in the scope. However, further studies are needed to confirm the efficacy and safety of these compounds in-vivo. The escalating threat of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) underscores the critical need for novel therapeutic agents. This study is motivated by the urgent search for new antibiotics, particularly those effective against multidrug-resistant pathogens. We selected the imidazole scaffold for this investigation because of its proven antimicrobial properties and its potential for structural modification to enhance activity. The specific compounds (N1, N2, N3) were designed with halogen substitutions and extended aromatic systems, features known to improve penetration of microbial membranes and interaction with biological targets. This work aims to evaluate these imidazole derivatives as potential antimicrobial agents through a combination of experimental and computational approaches.

In the present work, some tetra-substituted imidazoles (N1, N2, and N3) were obtained in the presence of N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone hydrogen sulfate (NM-2-PHS) ionic liquid catalyst. The antimicrobial activity of the obtained imidazoles was studied against Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Bacillus anthracoides, and Candida albicans, and their theoretical calculations were carried out. Next, the computational studies of imidazoles were investigated through density functional theory (DFT) atomistic simulations. The energy evaluations of valence orbitals were performed to provide a comparative understanding of the electro-activity of the molecules. Finally, molecular docking in-silico experiments were conducted to validate and complement the experimental findings, offering insights into the molecular interactions and binding affinities of the compounds.

Materials and methods

Solvents and reagents were bought from Aldrich. Tetramethylsilane (TMS) was used as an internal standard, acetone-D6 and DMSO-D6 were used as solvents, and the studied compounds’ ¹H and ¹³C NMR spectra were recorded using a BRUKER-Fourier (300 MHz) spectrometer at 20 °C. Using the spectrometer LUMOS FT-IR Microscope (BRUKER Company of Germany), infrared spectra were recorded in the 600–4000 cm⁻¹ wavelength range. On the TRUSPEC MICRO instrument made by the LECO business, the elemental analysis was measured. Melting temperatures were determined using a DSC-Q-20 instrument. The antimicrobial activity was evaluated using the disk diffusion method, following the protocol described in reference29.

DFT calculations and optimizations

GaussView software30 was employed to generate all chemical structures, while the AMS2023.105 software31,32,33,34 was utilized to optimize the structures and calculate vibrational frequencies using density functional theory (DFT) at the DFT//B3LYP-D3//TZP level. These calculations confirmed that the structures corresponded to true energy minima. The analysis of frontier molecular orbitals (FMOs) included the evaluation of the HOMO, LUMO, energy gap, and reactivity indices, along with the molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) to identify reactive sites35,36. Key descriptors such as chemical hardness (η), softness (s), chemical potential (µ), and electrophilicity (ω) were derived from the HOMO and LUMO energies and are presented below.

Molecular docking analysis

Molecular docking is a widely used computational technique in molecular modeling for predicting the preferred binding orientation and interactions between a ligand and its target receptor37. Dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) is a critical enzyme in the folate metabolism pathway, playing a vital role in DNA synthesis, replication, and repair. Inhibition of DHFR disrupts these cellular processes, making it a well-established target for antifungal drug development. Previous studies have shown that imidazole-based derivatives exhibit inhibitory activity against DHFR, impacting folate metabolism or ergosterol biosynthesis, both of which are essential for fungal cell survival. Due to the structural similarities between the studied compounds (N1, N2, and N3) and known DHFR inhibitors, molecular docking studies were performed against Candida albicans DHFR (PDB ID: 1AI9) to evaluate their potential interactions and binding affinities (Fig. 1). The crystal structure of Candida albicans dihydrofolate reductase (PDB ID: 1AI9, X-ray diffraction resolution: 1.85 Å), obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB), was used for the docking analysis. The binding modes and interactions between the active compounds and the 1AI9 protein were investigated using Molegro software38. Docking was carried out using the Moldock optimizer algorithm, with parameters set to a population size of 180 and a maximum of 3000 iterations. The top 5 conformations were analyzed, and the conformation with the lowest binding energy was selected for further evaluation.

Ethics approval.

The authors declare that this study did not involve any experiments on human participants or animals requiring ethical approval.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations

GROMACS 2023-GPU was used to perform the molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to evaluate the stability of the complexes formed by N1, N2, and N3 with the target protein39. The simulations were based on the optimal docking poses selected from the receptor-ligand interaction energies derived from the docking studies. The binding interactions between these ligands and the protein were thoroughly analyzed to gain insights into their stability and interaction mechanisms.

The protein-ligand complexes were solvated in a periodic cubic box with a 10 Å solute-box edge distance, filled with TIP3P water molecules. The SwissParam server was used to generate CHARMM force field parameters for the ligands40. The system was initialized using the CHARMM36 force field in combination with the TIP3P water model41. To neutralize the system, two chloride ions (Cl⁻) were added to each protein-ligand complex.

The initial configurations for the MD simulations were derived from the prepared structures obtained from docking studies. These simulations aimed to identify the active site and analyze key protein-ligand interactions to assess the stability of the system. The simulations included equilibration for 2 nanoseconds each under NVT (constant number of particles, volume, and temperature) and NPT (constant number of particles, pressure, and temperature) ensembles, followed by a 500-nanosecond production MD simulation to further evaluate the system’s behavior42,43,44. The resulting trajectories were analyzed using VMD45. The stability of the obtained complexes was evaluated using root-mean-square deviation (RMSD), root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF), radius of gyration (Rg), and solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) analyses. These metrics provided insights into the structural dynamics, conformational changes, compactness, and solvent exposure of the protein-ligand complexes over the course of the simulation. Additionally, post-MD analyses were performed to further characterize the system. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was used to identify dominant conformational changes and collective motions. MMPBSA (Molecular Mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area) calculations were conducted to estimate binding free energies and quantify protein-ligand interactions. Furthermore, Gibbs free energy calculations were carried out to assess the thermodynamic stability of the complexes46.

In silico ADMET and drug-likeness prediction

To evaluate the potential of the top-ranked docked ligands as drug candidates, their pharmacokinetic profiles and toxicity were assessed in silico. Key parameters for drug-likeness—including lipophilicity (Log P), aqueous solubility (Log S), gastrointestinal absorption (HIA), blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability, and skin permeation—were predicted using the SwissADME web server47. These parameters were evaluated against established rules, including Lipinski’s Rule of Five48, and the filters of Ghose49 and Veber50. Additionally, a bioavailability score was calculated for each compound. To complement the ADME analysis, potential toxicity endpoints (e.g., AMES mutagenicity, hepatotoxicity) were predicted using the pkCSM web server51. This integrated computational profiling provides a crucial preliminary assessment of the compounds’ suitability for further development.

Results and discussion

Synthesis of diphenyl and phenyldiazenylphenyl-based imidazoles

The diphenyl and phenyldiazenylphenyl based tetrasubstituted imidazole compounds (N1, N2, and N3) were synthesized via a multi-component reaction as previously reported52. The synthesis was carried out using N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone hydrogen sulfate as the catalyst. The detailed synthetic procedure, reaction scheme, FT-IR, 1H and 13C NMR spectra, spectral interpretation, and elemental analysis data for N1, N2, and N3 are provided in the Supplementary Material. The structures of the compounds are presented in Fig. 2.

Chemical structures and geometrically optimized DFT models of the studies imidazole derivatives. (a) 2,4,5-triphenyl-1-(4-(phenyldiazenyl)phenyl)−1 H-imidazole (N1); (b) 2-(4-chlorophenyl)−4,5-diphenyl-1-(4-(phenyldiazenyl)phenyl)−1 H-imidazole (N2); (c) 2-(2,4-dichlorophenyl)−4,5-diphenyl-1-(4-(phenyldiazenyl)phenyl)−1 H-imidazole (N3).

Antimicrobial activities

The antimicrobial activity of the substances was studied by the disk-diffusion method according to the methodology29. Laboratory strains of Staphylococcus aureus, representative of gram-positive bacteria; Escherichia coli, representative of gram-negative bacteria; and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Bacillus anthracoides, which have high natural resistance to antibiotics; and Candida albicans, which causes opportunistic mycosis, were used as test cultures. The mentioned bacteria were cultured in meat-peptone agar, and candida in Saburo’s medium. In the research, suspensions of 24-hour test cultures, 500 million microbial cells in 1 ml of physiological solution, were used. Each microorganism suspension prepared by this method was evenly spread over the surface of the respective nutrient media by means of buffers. Thereafter, each substance (50 and 100 µg/ml solutions in DMSO) was soaked on sterile paper discs with a diameter of 6 mm and placed on nutrient media inoculated with microbes. After incubation for 24 h at 37 °C, results were recorded for the growth of microorganisms around the impregnated discs. Areas around the disk where microbes do not develop—the diameter of the sterile zones is shown in mm (Table 1).

Each compound was assessed for antimicrobial activity using the disk diffusion method, with each sample tested in five independent replicates (n = 5) against the selected microbial strains. The results, expressed as mean inhibition zone diameters ± standard deviation (mean ± SD), are summarized in Table 1. Representative data from the fifth replicate are shown in Fig. 3. The antimicrobial efficacy of the studied imidazole derivatives (N1, N2, and N3) was evaluated at concentrations of 50 and 100 µg/mL against a spectrum of clinically relevant bacteria and fungi.

Analysis of the inhibition zones revealed that compound N2 exhibited the most pronounced antimicrobial activity across the majority of tested strains at both concentrations. In particular, N2 demonstrated substantial inhibitory effects against Staphylococcus aureus (29.3 ± 0.8 mm at 100 µg/mL) and Candida albicans (32 ± 0.3 mm at 100 µg/mL), highlighting its potent antibacterial and antifungal properties. Compound N1 displayed intermediate activity, with notable inhibition of Klebsiella pneumoniae (26.8 ± 0.8 mm at 100 µg/mL) and C. albicans (30 ± 1 mm at 100 µg/mL), though its effectiveness was consistently lower than that of N2 for most pathogens. Conversely, N3 exhibited the lowest activity among the tested derivatives, particularly against Escherichia coli (12.2 ± 0.8 mm at 100 µg/mL) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (21 ± 1 mm at 100 µg/mL). Despite its comparatively weaker antibacterial performance, N3 maintained moderate antifungal activity, with inhibition of C. albicans (29.1 ± 0.7 mm at 100 µg/mL) similar to that observed for N1.

As positive controls, ciprofloxacin and fluconazole were employed to benchmark antibacterial and antifungal efficacy, respectively. Ciprofloxacin generated the largest inhibition zones for S. aureus (30 ± 1 mm), E. coli (29.1 ± 0.4 mm), and K. pneumoniae (30 ± 1 mm), and fluconazole exhibited remarkably high activity against C. albicans (31.8 ± 0.5 mm).

Collectively, the antimicrobial performance of the compounds followed the order N2 > N1 > N3, underscoring the critical influence of molecular structure on biological activity. These empirical findings are well-aligned with theoretical predictions obtained from density functional theory (DFT), molecular docking, and molecular dynamics simulations, which corroborate the superior bioactivity of N2. The integration of experimental and computational approaches thus reinforces the potential of N2 as a promising lead compound for the development of novel antimicrobial agents.

Density functional theory (DFT) study

The DFT determination of important parameters such as EHOMO, ELUMO, chemical hardness (η), chemical softness (σ), electronegativity (λ), chemical potential (µ), electrophilicity index (ω), ionization potential (I), and electron accepting power (w+), electron affinity (A) were performed and results are listed in Table 2, based on the dataset of references13,53,54,55,56,57,58,59. The optimized structures of the N1, N2, and N3 molecules are shown in Figs. 2d, e, and f.

Structural analysis revealed key conformational differences. As explained in the supplementary material (Table 3S), the N1-C3-N2 angle within the imidazole ring is larger in the N3 molecule (111.383°) compared to N1 and N2. Furthermore, the substituted phenyl fragment in the N3 molecule is significantly more torsioned, with an N1-C3-C4-C5 torsion angle of −103.31°, compared to −31.36° and − 29.63° for N1 and N2, respectively. This pronounced torsion likely influences its overall reactivity.

The frontier orbitals (HOMO and LUMO) and electron density electrostatic potential (ESP) of the studied compounds are shown in Fig. 4. The HOMO orbitals of N1 and N2 are delocalized over the imidazole ring and adjacent phenyl groups, while in N3, the delocalization is more restricted. The LUMO orbitals are consistently localized on the phenyldiazenyl phenyl fragment across all compounds, identifying it as a key electron-accepting site.

Most importantly, the calculated global reactivity descriptors provide a compelling electronic rationale for the observed trend in antimicrobial effectiveness (N2 > N1 > N3). The HOMO-LUMO energy gap (ΔEgap) is a primary indicator of chemical stability and reactivity. Compound N3, with the largest gap (2.9546 eV) and the highest chemical hardness (η = 0.109 eV), is predicted to be the most stable and least reactive molecule in the series. This high kinetic stability correlates directly with its lowest antimicrobial activity, as it is less prone to engage in charge-transfer interactions with biological targets. Conversely, the enhanced reactivity of N1 and N2 is evidenced by their lower ΔEgap values. However, the key descriptor explaining N2’s superior bioactivity is its highest electrophilicity index (ω = 0.127 eV). Electrophilicity measures a molecule’s capacity to accept electrons, a crucial process for interacting with nucleophilic sites in microbial proteins or DNA. The higher electrophilicity of N2 aligns with its greater electron affinity (A), indicating a stronger driving force for interactions with electron-rich biological macromolecules.

The N1 and N2 molecules’ HOMO orbitals are delocalized throughout the imidazole ring and the nearby phenyl and substituted phenyl fragments, as apparent in Fig. 4. On the other hand, the HOMO orbitals in the N3 molecule are mostly delocalized over the diphenyl fragment and the imidazole ring.In contrast to N3, where the delocalization is restricted to the carbon atoms C5 and C9 of the corresponding aromatic fragment, N1 and N2 exhibit HOMO orbitals that completely extend over the aromatic fragment connected to the imidazole ring at the 2-position.The LUMO orbitals are continuously delocalized over the phenyldiazenyl phenyl fragment in each of the three molecules. According to Table 2, the HOMO-LUMO gap (ΔEgap) values for the compounds N1, N2, and N3 are 2.7815 eV, 2.7963 eV, and 2.9546 eV, respectively. The higher ΔEgap value of the N3 molecule (2.9546 eV) indicates greater stability and lower reactivity compared to N1 and N2. This idea is further supported by the higher chemical hardness (η = 0.109 eV) and electronegativity (χ = 0.163 eV) values of N3, which suggest a stronger resistance to deformation and a higher tendency to attract electrons, respectively. On the other hand, N1 exhibits the lowest stability among the three compounds, as evidenced by its lower ΔEgap value (2.7815 eV) and higher chemical softness (S = 9.783 eV⁻¹), indicating greater reactivity. The electronic chemical potential (µ) values for N1, N2, and N3 are − 0.159 eV, −0.161 eV, and − 0.163 eV, respectively. These negative values suggest that all three compounds are electron acceptors and are unlikely to decompose into their constituent elements. Additionally, the electrophilicity index (ω) values for N1, N2, and N3 are 0.123 eV, 0.127 eV, and 0.122 eV, respectively. The higher electrophilicity index of N2 (0.127 eV) indicates its greater capacity to accept electrons, which correlates with its higher electron affinity (A) and electroaccepting power (w + = 0.179 eV) compared to N1 and N3. This suggests that N2 may exhibit stronger biological activity, as electrophilicity is often linked to reactivity in biological systems. The ionization potential (I) values, derived from the HOMO energies, are 5.7074 eV, 5.7907 eV, and 5.9079 eV for N1, N2, and N3, respectively. The higher ionization potential of N3 further supports its greater stability and lower reactivity. In contrast, N1 has the lowest ionization potential, indicating a higher tendency to lose electrons and thus greater reactivity. In terms of net electrophilicity, the values for N1, N2, and N3 are 0.505 eV, 0.520 eV, and 0.502 eV, respectively. The slightly higher net electrophilicity of N2 (0.520 eV) suggests it may have a stronger interaction with biological targets, which aligns with its higher electroaccepting power (w + = 0.179 eV) and electrophilicity index (ω = 0.127 eV).

Overall, the data suggests the following trends in stability and reactivity: N3 > N2 > N1. However, in terms of biological activity, the ranking is likely N2 > N1 > N3, as N2 exhibits the highest electrophilicity index and electron affinity, which are critical for interactions in biological systems. This ranking is consistent with the observed antimicrobial activities of the compounds.

The experimental antimicrobial results and theoretical DFT-based analyses exhibit a coherent trend, reinforcing each other’s findings. Experimentally, compound N2 showed the highest antimicrobial activity against a range of bacterial and fungal strains, with larger inhibition zones compared to N1 and N3, particularly against S. aureus and C. albicans. This trend is consistent with the DFT results, where N2 displayed the highest electrophilicity index (ω = 0.127 eV) and electron affinity, suggesting greater reactivity toward biological targets. While N3 had the largest HOMO-LUMO gap (ΔE = 2.9546 eV) and highest ionization potential, indicating higher chemical stability and lower reactivity, it also exhibited the lowest antimicrobial activity. In contrast, N1 and especially N2 had lower energy gaps and higher softness values, pointing to greater molecular reactivity, which aligns with their enhanced biological effects. Thus, the theoretical descriptors-especially electrophilicity, softness, and electron affinity—correlate well with the observed antimicrobial efficacy, validating the predictive value of DFT parameters for assessing bioactivity.

Molecular docking analysis

The docking results for the ligands N1, N2, and N3 with the target protein revealed that all three compounds exhibit strong binding affinities, with slight variations due to differences in their chlorine atom arrangements and molecular symmetry. N1 demonstrated the highest binding affinity, with a MolDock Score of −168.945 kcal/mol and a significant HBond energy of −5.49808, indicating strong hydrogen bonding interactions. N2 also showed excellent binding, with a MolDock Score of −161.248 kcal/mol and an HBond energy of −1.5888, while N3 displayed slightly lower but still favorable binding, with a MolDock Score of −158.961 kcal/mol and an HBond energy of −1.83895. These differences are attributed to the variations in the chlorine atom configurations and molecular symmetry of the ligands, which influence their interactions with the target protein (Table 3). Specifically, the binding of N2 to the Candida albicans target protein (PDB: 1AI9), Table 4, formed a hydrogen bond at the Asn5 site and interacted with the target through pi-anion (Glu82), pi-alkyl (Arg108), and pi-pi stacking (His129) interactions. The presence of aromatic amino acids, such as histidine (His129), in the target protein structure played a significant role in stabilizing the complex (Fig. 5; Table 3). The three-dimensional (3D) interactions between the N2 molecule and the target protein were visualized using the Discovery Studio Visualizer (Fig. 5), highlighting the strong binding affinity and specificity of N2 towards the Candida albicans target. Overall, the results suggest that all three ligands are promising candidates, with N1 being the most favorable due to its superior binding affinity and hydrogen bonding interactions, while N2 demonstrates strong specificity and interaction stability with the target protein (Fig. 5).

The findings are consistent with previous studies reporting the inhibitory effects of various compounds on 1AI9 and other enzymes in the ergosterol pathway. However, this study is the first to report the molecular docking of N2 with 1AI9, providing detailed insights into the binding mechanism and interaction features in comparison with in-vitro tests. Our work also highlights the utility of molecular docking as a fast and efficient computational tool for screening and designing inhibitors of fungal enzymes.

Despite these promising results, our study has some limitations. First, molecular docking is a theoretical approach that depends on the accuracy of input structures and docking parameters, which may not fully reflect the actual binding behavior and dynamics of N2 and 1AI9 in vivo. Second, molecular docking does not account for environmental factors such as solvent effects, temperature, and pH, which can influence binding. Third, this approach does not provide information on the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of N2, including its absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity. Therefore, further experimental validation and optimization of N2 are necessary to confirm its inhibitory activity and evaluate its potential as a drug candidate.

This study demonstrated that N2 exhibits strong binding affinity and favorable interactions with the target protein 1AI9 from Candida albicans. Molecular dynamics simulations further validated these findings, confirming the stability of the N2-1AI9 complex and supporting N2 as a potential antifungal agent, while highlighting the need for experimental validation to assess its biological relevance and therapeutic potential. While molecular docking identified N1 as having the strongest binding affinity, the interaction profile of N2-characterized by specific hydrogen bonding and π-interactions with key residues in the Candida albicans target protein-suggests a higher degree of binding specificity and complex stability. This observation is reinforced by DFT-derived electronic descriptors, with N2 exhibiting the highest electrophilicity and electron-accepting power, indicative of greater reactivity toward biological targets. Experimentally, N2 displayed superior antimicrobial efficacy, aligning well with its theoretical reactivity and interaction stability. Together, these findings illustrate how docking, quantum chemical calculations, and experimental assays can converge to highlight N2 as a lead compound, while also underscoring the complementary nature of computational and empirical approaches in rational drug design.

Molecular dynamic simulations

Molecular dynamics simulations were performed to investigate the atomic-level dynamic behavior of all protein-ligand (P-L) complexes, including N2@1AI9. The root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) values were calculated relative to the initial conformations, and the results are presented in Fig. 6 (a) and (b), which illustrates the RMSD plots for all complexes. While the RMSD plots showed initial fluctuations, most complexes stabilized after 10 ns. For instance, the N2@1AI9 complex reached equilibrium within 15 ns, maintaining an average RMSD of 0.24 nm, indicating a stable and well-preserved binding conformation. Similarly, other complexes, such as N1 and N3, exhibited stable behavior, with average RMSD values ranging from 0.2 nm to 0.28 nm. Overall, the RMSD analysis confirmed that all complexes maintained stable interactions with their respective proteins, with N2@1AI9 demonstrating the most consistent and stable behavior. These results validate the robustness of the interactions and reinforce the potential of these ligands, particularly N2, as promising candidates for further development.

To evaluate the flexibility of amino acid residues in the 1AI9 protein upon ligand binding, root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) analysis was performed. High RMSF values indicate flexible or highly dynamic regions of the protein, while low values suggest stable and rigid residues. As illustrated in Fig. 7, the majority of amino acid residues exhibited RMSF values below 0.19 nm, signifying minimal structural deviations and overall protein stability when complexed with the tested ligands (N1, N2, N3). The final average RMSF values for N1@1AI9, N2@1AI9, and N3@1AI9 were 0.11 nm, 0.10 nm, and 0.11 nm, respectively. Notably, the N1@1AI9 complex exhibited the highest fluctuation at residue 200, where the RMSF reached approximately 0.5 nm. This localized increase in flexibility suggests a potential conformational adjustment in that region, possibly due to ligand interactions or inherent structural characteristics of the protein. Despite this fluctuation, the RMSF values for most residues remained below 0.2 nm, indicating that ligand binding did not induce significant conformational instability. Additionally, as commonly observed in molecular dynamics simulations, high fluctuations were detected in the terminal regions of the protein. These fluctuations are likely attributed to their intrinsically disordered nature, as terminal residues often exhibit greater mobility due to their lack of structural constraints. Overall, these findings suggest that the tested ligands (N1, N2, N3) maintained the structural integrity of the 1AI9 protein, with minimal disruptions to residue stability. The localized flexibility observed in specific regions warrants further investigation to determine its potential impact on protein function and ligand binding affinity.

The radius of gyration (Rg) is a critical measure of protein compactness and stability during molecular dynamics simulations. In this study, Rg analysis of the N1@1AI9, N2@1AI9, and N3@1AI9 complexes revealed stable structural integrity throughout the simulation, as shown in Fig. 8. The average Rg values were 1.69 nm, 1.67 nm, and 1.69 nm for N1@1AI9, N2@1AI9, and N3@1AI9, respectively, indicating minimal fluctuations and consistent compactness. These results confirm that the protein maintained its globular conformation without significant expansion or destabilization, further supporting the stability of the ligand-protein complexes.

Other parameters were used to evaluate the stability of our complexes, including the solvent-accessible surface area (SASA). The SASA plots in Fig. 9 illustrate changes in the protein’s surface area accessible to the solvent, with average SASA values for N1@1AI9, N2@1AI9, and N3@1AI9 being 113.4 nm², 110.5 nm², and 114.2 nm², respectively. These values reflect the extent of the protein’s surface exposed to the solvent, providing insights into the dynamic behavior of the complexes. The stable SASA profiles observed for all systems indicate consistent solvent exposure and minimal conformational changes throughout the simulation. This stability suggests that the ligands did not induce significant unfolding or structural rearrangements in the protein, further confirming the structural integrity of the protein-ligand complexes. The consistent SASA values also imply that the binding of the ligands did not alter the protein’s overall hydrophobicity or surface properties, which is crucial for maintaining its functional stability in an aqueous environment (Fig. 9).

To further validate the stability and binding mechanisms of the N1@1AI9, N2@1AI9, and N3@1AI9 complexes, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and MM/PBSA (Molecular Mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area) calculations were performed.

The PCA analysis was performed to investigate the dominant collective motions of the N1@1AI9, N2@1AI9, and N3@1AI9 complexes. The PCA results, illustrated in Fig. 10, project the conformational dynamics of the protein-ligand systems onto the first two principal components (PC1 and PC2), which capture the majority of the system’s variance. The N2@1AI9 and N3@1AI9 complexes exhibited a compact cluster along PC1 and PC2, suggesting stable binding and restricted rigid interactions.

The N1@1AI9 complex showed a more dispersed trajectory, indicating moderate flexibility. The projections along eigenvector 1 (PC1) and eigenvector 2 (PC2) reveal the relative contributions of each complex to the overall conformational dynamics. For instance, the range of projections along PC1 from − 4 nm to 6 nm and PC2 from − 5 to 5 highlights the diversity of motions sampled by the protein-ligand systems. These findings provide valuable insights into the conformational flexibility and stability of the complexes, demonstrating how ligand binding influences the protein’s dynamic behavior.

Finally, the Molecular Mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area (MMPBSA) method was employed to validate the obtained results and quantify the binding free energies of the protein-ligand complexes. MMPBSA is a widely used computational approach that combines molecular mechanics (MM) for gas-phase interactions with implicit solvent models (Poisson-Boltzmann and Surface Area) to estimate binding affinities. By decomposing the binding free energy into its energetic components, such as van der Waals, electrostatic, polar solvation, and non-polar solvation contributions, MMPBSA provides detailed insights into the molecular interactions driving ligand binding. This method complements the structural and dynamic analyses (e.g., RMSD, RMSF, SASA, RG, and PCA) by offering a quantitative assessment of the stability and binding affinity of the complexes, thereby reinforcing the conclusions drawn from the molecular dynamics simulations.

The MMPBSA calculations revealed that all complexes (N1@1AI9, N2@1AI9, and N3@1AI9) exhibit similar trends in their energetic components, with variations in the magnitude of contributions. Van der Waals interactions (ΔVDWAALS) were favorable in all complexes, with values of −26.52 kcal/mol to −39.49 kcal/mol, indicating strong non-polar interactions, particularly for N2@1AI9. Electrostatic interactions (ΔEEL) also contributed favorably, with values of −409.46 kcal/mol for N2@1AI9, and − 147.61 kcal/mol for N3@1AI9, highlighting the importance of Coulombic forces, especially for N2@1AI9. However, polar solvation penalties (ΔEPB) were significant, with values of 158.23 kcal/mol for N1@1AI9, 408.21 kcal/mol for N2@1AI9, and 167.34 kcal/mol for N3@1AI9, reflecting the desolvation cost associated with binding. Non-polar solvation (ΔENPOLAR) contributed favorably, with values of −4.07 kcal/mol for N1@1AI9, −3.08 kcal/mol for N2@1AI9, and − 5.05 kcal/mol for N3@1AI9, indicating hydrophobic interactions.

Overall, the total binding free energies (ΔTOTAL) were favorable for all complexes. These results demonstrate that N2@1AI9 is the most stable complex due to its strong van der Waals interactions and manageable solvation penalties. The shared trends in energetic contributions highlight the importance of balancing gas-phase interactions and solvation effects in determining binding affinity.

The experimental assays, DFT calculations, molecular docking, and dynamics are combined to provide a thorough understanding of the stability and reactivity profiles among the different structures (N1, N2, N3) of the target molecule. DFT analysis indicates that N2 is the most electrophilic and reactive molecule, which is consistent with its higher antimicrobial activity as seen in experiments. The strong binding affinity of N2 for Candida albicans target protein 1AI9 was further validated by molecular docking. Molecular dynamics simulation supported these observations, showing that N2@1AI9 continuously had the most stability across the number of MD parameters, such as Rg, RMSD, and RMSF, indicating its little conformational disruption and robust binding conformation retention.

In silico ADME profiling

To preliminarily assess the drug-likeness and pharmacokinetic profile of the lead compound N2 in comparison with N1 and N3, in silico predictions of Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) parameters were performed using the SwissADME web server. The key parameters are summarized in Table 5.

The analysis of Lipinski’s Rule of Five indicates that all compounds present violations, primarily due to their high molecular weight (MW > 500 g/mol for N2 and N3) and high lipophilicity (Consensus Log P > 5). While this suggests potential challenges for oral bioavailability, it is not uncommon for antimicrobial agents that often possess complex structures. All compounds are predicted to have low gastrointestinal (GI) absorption. Notably, none are predicted to permeate the blood-brain barrier (BBB), which could be advantageous by reducing the risk of central nervous system-related side effects.

Regarding metabolism, all three compounds are predicted to be inhibitors of the cytochrome P450 enzyme CYP2C19, and compound N2 is additionally predicted to inhibit CYP3A4. This highlights a potential for drug-drug interactions that would need to be investigated in future studies. Compound N2 is also predicted to be a substrate for P-glycoprotein (P-gp), which may influence its distribution and excretion. The solubility predictions classify all compounds as poorly soluble.

Despite the identified challenges related to solubility and molecular size, the lead compound N2 exhibits a promising profile for further investigation as a potential antimicrobial agent, particularly for topical or intravenous administration routes where oral bioavailability is less critical. The in silico toxicity alerts (e.g., single PAINS alert) warrant consideration but do not preclude its potential. These ADMET predictions provide a crucial initial roadmap for the subsequent optimization and development of these imidazole derivatives.

Conclusions

This integrated in vitro and in silico study conclusively establishes the antimicrobial potential of the imidazole derivatives, with compound N2 emerging as the lead candidate. The clear biological activity trend (N2 > N1 > N3) was rationalized by DFT calculations, where N2’s highest electrophilicity index (ω = 0.127 eV) indicated a superior reactivity profile conducive to biological interactions. The molecular basis for N2’s pronounced antifungal effect was elucidated through docking studies, which revealed its strong binding affinity and specific interactions including hydrogen bonding with Asn5 and π-based interactions with Glu82 and His129 within the active site of Candida albicans dihydrofolate reductase (PDB: 1AI9). The stability and energetics of the N2-protein complex were further validated by molecular dynamics simulations and MM-PBSA calculations, which confirmed the robustness of the binding pose observed in docking. In silico ADMET studies provided crucial insights into the compounds’ pharmacokinetic profiles, demonstrating that while the derivatives may face limitations regarding oral bioavailability (e.g., low GI absorption and Lipinski violations), the lead compound N2 retains a promising profile, particularly supporting its potential for topical or intravenous administration in future drug development efforts. While these computational results provide a compelling mechanistic hypothesis, they underscore the need for future experimental validation, including in vivo studies. Overall, the convergent evidence from antimicrobial assays, quantum chemical descriptors, and computational modeling solidly positions N2 as a promising scaffold for the development of novel antifungal agents.

Data availability

The original data and contributions presented in this study are included in the article and its Supplementary Material. Any further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

References

Khalili, N. S. D. et al. Synthesis and biological activity of imidazole phenazine derivatives as potential inhibitors for NS2B-NS3 dengue protease, Heliyon 10 (2) (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e24202

Verma, A., Joshi, S. & Singh, D. Imidazole: having versatile biological activities. J. Chem. Vol. no. 1, 329412. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/329412 (2013). 2013/01/01 2013.

Sharma, P., LaRosa, C., Antwi, J., Govindarajan, R. & Werbovetz, K. A. Imidazoles as potential anticancer agents: an update on recent studies. Molecules 26 (14). https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26144213

Al-Ghamdi, H. A. et al. Synthesis and biological evaluation of novel imidazole derivatives as antimicrobial agents. Biomolecules 14 (9). https://doi.org/10.3390/biom14091198

Deng, C. et al. The anti-HIV potential of imidazole, oxazole and thiazole hybrids: A mini-review. Arab. J. Chem. 15(11), 104242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2022.104242 (2022).

Abdelhamid, A. A., Salah, H. A. & Marzouk, A. A. Synthesis of imidazole derivatives: Ester and hydrazide compounds with antioxidant activity using ionic liquid as an efficient catalyst. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 57(2), 676–685. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhet.3808 (2020).

Muheyuddeen, G. et al. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of novel imidazole derivatives as analgesic and anti-inflammatory agents: experimental and molecular docking insights. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 23121. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72399-8 (2024).

Ghoshal, J. & Lavanya, M. Inhibition of microbial corrosion by green inhibitors: an overview. Iran. J. Chem. Chem. Eng. 42 (2), 684–703. https://doi.org/10.30492/ijcce.2022.539832.4950 (2023).

Siwach, A. & Verma, P. K. Synthesis and therapeutic potential of imidazole containing compounds. BMC Chem. 15(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13065-020-00730-1 (2021).

Verma, C. & Quraishi, M. A. Ionic liquids-metal surface interactions: Effect of alkyl chain length on coordination capabilities and orientations. Prime Adv. Electr. Eng. Electron. Energy 2, 100070. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prime.2022.100070 (2022).

Hadigheh-Rezvan, V. Molecular structure, HOMO–LUMO, and NLO studies of some quinoxaline 1,4-dioxide derivatives: Computational (HF and DFT) analysis. Results Chem. 7, 101437 (2024).

Yolchuyeva, U. J. et al. Chemical composition and molecular structure of asphaltene in Azerbaijani crude oil: A case study of the Zagli field. Fuel 373, 132084. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2024.132084 (2024).

Choudhary, V., Bhatt, A., Dash, D. & Sharma, N. DFT calculations on molecular structures, HOMO–LUMO study, reactivity descriptors and spectral analyses of newly synthesized diorganotin(IV) 2-chloridophenylacetohydroxamate complexes. J. Comput. Chem. 40, 2354–2363. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.26012 (2019). /10/15 2019.

Parthasarathi, R., Subramanian, V., Roy, D. R. & Chattaraj, P. K. Electrophilicity index as a possible descriptor of biological activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 12(21), 5533–5543. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmc.2004.08.013 (2004).

El-Shamy, N. T. et al. DFT, ADMET and molecular Docking investigations for the antimicrobial activity of 6,6′-Diamino-1,1′,3,3′-tetramethyl-5,5′-(4-chlorobenzylidene)bis[pyrimidine-2,4(1H,3H)-dione], Molecules, 27 (3). https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27030620

Abbasov, V., Alimadatli, N., Azizov, R., Mamedov, A. & Aghamaliyeva, D. Synthesis of complexes of oleic acid with alkylamines and theoretical study of their structures. Processes Petrochem. Oil Refining 24 (4) (2023).

Abdullayev, Y. et al. Construction of new azo-group containing polycyclic imidazole derivatives: Computational mechanistic, structural, and fluorescence studies. ChemistrySelect 5(20), 6224–6229. https://doi.org/10.1002/slct.202000949 (2020).

Erdoğan, T. & Oğuz Erdoğan, F. Nucleophilic Substitution Reaction of Imidazole with Various 2-Bromo-1-arylethanone Derivatives: A Computational Study (in en). Sakarya Univ. J. Sci. 23(3), 322–332. https://doi.org/10.16984/saufenbilder.418343 (2019).

Awasthi, A., Rahman, M. A. & Bhagavan Raju, M. Synthesis, In Silico Studies, and In Vitro Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Novel Imidazole Derivatives Targeting p38 MAP Kinase. ACS Omega 8, 17788–17799. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.3c00605 (2023).

Ting-Ting, K., Cheng-Mei, Z. & Zhao-Peng, L. Recent Developments of p38αMAP Kinase Inhibitors as Antiinflammatory Agents Based on the Imidazole Scaffolds. Curr. Med. Chem. 20(15), 1997–2016. https://doi.org/10.2174/0929867311320150006 (2013).

Rasul, H. O. Synthesis, evaluation, in silico ADMET screening, HYDE scoring, and molecular docking studies of synthesized 1-trityl-substituted 1H-imidazoles. J. Iran. Chem. Soc. 20(12), 2905–2916. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13738-023-02887-7 (2023).

Dindi, U. M. R. et al. In-silico and in-vitro functional validation of imidazole derivatives as potential Sirtuin inhibitor. Front. Med. 10, 1282820. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2023.1282820 (2023).

Grimes, J. M. & Grimes, K. V. p38 MAPK inhibition: A promising therapeutic approach for COVID-19. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 144, 63–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yjmcc.2020.05.007 (2020).

Mikhaylov, A. А et al. Imidazolone-activated donor-acceptor cyclopropanes with a peripheral stereocenter. A study on stereoselectivity of cycloaddition with aldehydes. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 56(8), 1092–1096. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10593-020-02778-2 (2020).

Sadeghian, S. et al. Imidazole derivatives as novel and potent antifungal agents: Synthesis, biological evaluation, molecular docking study, molecular dynamic simulation and ADME prediction. J. Mol. Struct. 1302, 137447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2023.137447 (2024).

Hebert, S. P. & Schlegel, H. B. Computational investigation into the oxidation of guanine to form Imidazolone (Iz) and related degradation products. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 33(4), 1010–1027. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrestox.0c00039 (2020).

Zaitseva, E. R., Smirnov, A. Y., Ivanov, I. A., Mineev, K. S. & Baranov, M. S. Synthesis of 5-(aminomethylidene)imidazol-4-ones by using N, N-dialkylformamide acetals. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 56(8), 1097–1099. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10593-020-02779-1 (2020).

Kumar, S., Aghara, J. C., Manoj, A., Alex, A. T. & Joesph, A. Novel quinolone substituted Imidazol-5 (4H)-ones as Anti-inflammatory, anticancer agents: Synthesis, biological screening and molecular Docking studies. Indian J. Pharm. Educ. Res. 54 (3) (2020).

Verma, B. K., Kapoor, S., Kumar, U., Pandey, S. & Arya, P. Synthesis of new imidazole derivatives as effective antimicrobial agents. Indian J. Pharm. Biol. Res. 5 (01), 01–09 (2017).

Hanwell, M. D. et al. Avogadro: an advanced semantic chemical editor, visualization, and analysis platform. J. Cheminform. 4(1), 17. https://doi.org/10.1186/1758-2946-4-17 (2012).

Becke, A. D. Density-functional thermochemistry. I. The effect of the exchange‐only gradient correction. J. Chem. Phys. 96 (3), 2155–2160. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.462066 (1992).

Lee, C., Yang, W. & Parr, R. G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B 37(2), 785–789. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.37.785 (1988).

Parr, R. G. Density functional theory. Ann. Rev. Phys. Chem. 34(34), 631–656. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.pc.34.100183.003215 (1983).

AMS 2023, SCM, Theoretical Chemistry, Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, (2023). http://www.scm.com

Aihara, J. Reduced HOMO – LUMO gap as an index of kinetic stability for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. J. Phys. Chem. A 103(37), 7487–7495. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp990092i (1999).

Kim, K. H., Han, Y. K. & Jung, J. Basis set effects on relative energies and HOMO–LUMO energy gaps of fullerene C36. Theoretical Chem. Accounts 113(4), 233–237. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00214-005-0630-7 (2005).

Sultana, S., Hossain, A., Islam, M. & Kawsar, S. Antifungal potential of Mannopyranoside derivatives through computational and molecular Docking studies against Candida albicans 1IYL and 1AI9 proteins. Curr. Chem. Lett. 13 (1), 1–14 (2024).

Bitencourt-Ferreira, G. & de Azevedo, W. F. Molegro virtual docker for Docking. In Docking Screens for Drug Discovery (ed. de Azevedo, W. F., Jr.) 149–167 (Springer, 2019).

Abraham, M. J. GROMACS: High performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX 1, 19–25 (2015).

Vanommeslaeghe, K. et al. CHARMM general force field: A force field for drug-like molecules compatible with the CHARMM all‐atom additive biological force fields. J. Comput. Chem. 31 (4), 671–690 (2010).

Price, D. J. & Brooks, C. L. A modified TIP3P water potential for simulation with Ewald summation. J. Chem. Phys. 121 (20), 10096–10103 (2004).

Mostefai, N. et al. Identification of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and stability analysis of THC@HP-β-CD inclusion complex: A comprehensive computational study. Talanta 286, 127370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.talanta.2024.127370 (2025).

Guendouzi, A., Belkhiri, L., Houari, B., Djekoun, A. & Guendouzi, A. In-silico design of novel indole-selenide derivatives as potential P-glycoprotein inhibitors against multi-drug resistance in MCF-7/ADR Cells: 2D-QSAR, molecular docking, and dynamics simulations. ChemistrySelect 9(41), e202403304. https://doi.org/10.1002/slct.202403304 (2004).

Guendouzi, A. et al. Unveiling novel hybrids quinazoline/phenylsulfonylfuroxan derivatives with potent multi-anticancer inhibition: DFT and in silico approach combining 2D-QSAR, molecular docking, dynamics simulations, and ADMET properties. ChemistrySelect 9(43), https://doi.org/10.1002/slct.202404283 (2024).

Humphrey, W., Dalke, A. & Schulten, K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 14 (1), 33–38 (1996).

Zaki, K. et al. From farm to pharma: Investigation of the therapeutic potential of the dietary plants Apium graveolens L., Coriandrum sativum, and Mentha longifolia, as AhR modulators for Immunotherapy. Comput. Biol. Med. 181, 109051. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2024.109051.

Daina, A., Michielin, O. & Zoete, V. SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep. 7, 42717. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep42717 (2017).

Lipinski, C. A., Lombardo, F., Dominy, B. W. & Feeney, P. J. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv. Drug Deliv Rev. 46, 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00129-0 (2001).

Ghose, A. K., Viswanadhan, V. N. & Wendoloski, J. J. A knowledge-based approach in designing combinatorial or medicinal chemistry libraries for drug discovery. 1. A qualitative and quantitative characterization of known drug databases. J. Comb. Chem. 1 (1), 55–68. https://doi.org/10.1021/cc9800071 (1999).

Veber, D. F. et al. Molecular properties that influence the oral bioavailability of drug candidates. J. Med. Chem. 45 (12), 2615–2623. https://doi.org/10.1021/jm020017n (2002).

Pires, D. E. V., Blundell, T. L. & Ascher, D. B. PkCSM: predicting Small-Molecule Pharmacokinetic and toxicity properties using Graph-Based signatures. J. Med. Chem. 58 (9), 4066–4072. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00104 (2015).

Orujova, N. S., Mammadov, A. M., Jafarova, R. A., Yolchuyeva, U. J. & Ahmadbayova, S. F. Synthesis and study of Diphenyl and 4-(phenyldiazenyl) phenyl based tetrasubstituted imidazoles in the presence of ionic liquid catalysts. Process. Petrochem. Oil Refin. 24 (2) (2023).

Silvarajoo, S. et al. Dataset of theoretical molecular electrostatic potential (MEP), Highest Occupied Molecular Orbital-Lowest Unoccupied Molecular Orbital (HOMO-LUMO) band gap and experimental cole-cole plot of 4-(ortho-, meta- and para-fluorophenyl)thiosemicarbazide isomers. Data Brief 32, 106299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2020.106299 (2020).

Ayalew, M. E. DFT studies on molecular structure, thermodynamics parameters, HOMO-LUMO and spectral analysis of pharmaceuticals compound Quinoline (Benzo [b] Pyridine). J. Biophys. Chem. 13 (3), 29–42 (2022).

Abbasov, V. M. et al. green synthesis and dft calculations of 4’-(2-phenyl-1 h-phenanthro [9, 10-d] imidazol-1-yl)-[1, 1’-biphenyl]-4-amine. Process. Petrochem. Oil Refin. 26 (1) (2025).

Akash, S. et al. A drug design strategy based on molecular Docking and molecular dynamics simulations applied to development of inhibitor against triple-negative breast cancer by scutellarein derivatives. PLoS One. 18 (10), e0283271 (2023).

Parsaee, Z., Mohammadi, K., Ghahramaninezhad, M. & Hosseinzadeh, B. A novel nano-sized binuclear nickel(ii) schiff base complex as a precursor for NiO nanoparticles: synthesis, characterization, DFT study and antibacterial activity. New J. Chem. 40 (12), 10569–10583. https://doi.org/10.1039/C6NJ02642G (2016). 10.1039/C6NJ02642G vol.

Abbasov, V. M. et al. Study of the nitration reaction of 1-octene and DFT calculations. Process. Petrochem. Oil Refin. 25 (4) (2024).

Dhifaoui, S. et al. DFT studies on molecular Structure, absorption properties, NBO analysis, and Hirshfeld surface analysis of Iron(III) porphyrin complex. Phys. Chem. Res. 9 (4), 701–713. https://doi.org/10.22036/pcr.2021.272919.1886 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Khalid University for supporting this work through large group Research Project under grant number RGP2/413/46.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Nargiz S. Orujova: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Curation, Writing – Original Draft. Vagif M. Abbasov: Supervision, Project Administration, Validation, Writing – Review & Editing. Rana A. Jafarova: Investigation, Formal Analysis, Resources. Ayaz M. Mammadov: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – Review & Editing, Final Approval. Imren Bayil: Data Curation, Visualization, Technical Support. Sevda A. Muradova: Literature Review, Methodology, Writing – Review & Editing. Nabila Djadi: Software, Data Analysis, Visualization. Taha Alqahtani: Validation, Manuscript Editing, Resource Provision. Al-Anood M Al-Dies: Writing – Review & Editing, Investigation. Yayesew Amlaku Zerihun: Formal Analysis, Critical Review, Language Editing. Abdelkrim Guendouzi: Resources, Data Interpretation, Manuscript Revision. Magdi E. A. Zaki: Critical Review, Supervision, Final Review & Approval. The authors declare that consent for publication is not applicable.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Orujova, N.S., Abbasov, V.M., Jafarova, R.A. et al. In vitro, in silico, and DFT evaluation of antimicrobial imidazole derivatives with insights into mechanism of action. Sci Rep 15, 37723 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24847-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24847-2