Abstract

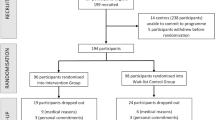

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) increases the risk of dementia. Reducing modifiable lifestyle-related risk factors can help prevent cognitive decline in patients with MCI. We examined whether a multidomain intervention using a mobile application can prevent cognitive decline in patients with MCI. The trial is designed in accordance with the CONSORT Statement. We conducted an assessor-blind, randomized controlled trial. Patients with MCI, aged over 60 years and presenting with at least one modifiable risk factor for dementia, were recruited from three dementia centers in Gangwon-do, Korea, and outpatient clinics at Chuncheon Sacred Heart Hospital. Participants were randomly assigned to either the intervention group or the control group in a 1:1 ratio. Each participant received a 52-week intervention. The intervention group used a mobile application to manage their diet and physical activity at least three times per week, while the control group received general dietary and physical activity recommendations twice a year. The primary outcome was the change in cognitive function measured based on the mini-mental state examination in the Korean version of the CERAD assessment packet (MMSE-KC) score. Between October 2020 and September 2021, 84 people were screened, and 80 participants were randomly assigned to either the control or intervention group (intervention group = 42, control group = 38). Participants in both groups underwent a post-baseline assessment and their data were included in the analysis. We found a positive effect of the multidomain intervention using a mobile application on the change in cognitive function score in the intervention group compared to the control group at the 52-week follow-up. The MMSE-KC (F = 10.6, p < .001) and modified Boston Naming test (F = 8.3, p < .01) scores were significantly higher in the intervention group than in the control group. The results suggest that a multidomain mobile application intervention could help improve cognition in patients with MCI.

The study protocol was prospectively registered with the Clinical Research Information Service (CRIS, Republic of Korea; KCT0008315) on March 16, 2023. The full trial details can be accessed at https://cris.nih.go.kr/cris/search/detailSearch.do?seq=22920.

Similar content being viewed by others

Intoduction

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) describes a condition between normal cognitive decline due to aging and pathological decline due to dementia. This condition is highly likely to progress to dementia1. However, there are limited pharmacological therapies that can prevent MCI from progressing to dementia2,3. Thus, it is essential to focus on non-pharmacological treatments to help improve patients’ quality of life.

Several systematic reviews and meta-analyses have investigated the efficacy of various non-pharmacological interventions for MCI populations. Cognitive training and stimulation have been shown to improve memory and executive function4, while physical exercise interventions, including aerobic and resistance training, have demonstrated positive effects on cognitive outcomes5,6. Additionally, lifestyle modifications such as diet and social engagement have also been explored as potential means to support cognitive health7,8.

Despite these promising findings, existing research has notable limitations. Multidomain interventions have proven effective, yet they are often conducted face-to-face9,10,11. Another critical limitation is that while multidomain interventions are believed to be more effective than single-domain interventions12, few studies have assessed their effectiveness using accessible and scalable delivery methods such as digital technology.

To address these challenges, electronic health (eHealth) interventions offer a more accessible and economically feasible solution13. Recent evidence supports the efficacy of eHealth in promoting self-management of cardiovascular risk factors and suggests that such interventions are more effective when coupled with human coaching14,15. Following this rationale, mobile applications that combine digital interventions with human feedback can support individuals in managing their lifestyle and reducing the risk of dementia. Interventions involving exercise, diet, social engagement, and cognitive activities have shown promise in reducing dementia risk and improving cognitive function in MCI patients. Despite the promising potential, there is a lack of studies specifically examining the effects of mobile-based multidomain interventions on cognitive function, and long-term follow-up research on the sustainability of cognitive benefits is also scarce.

This study aimed to investigate whether multidomain interventions using a mobile application can help maintain cognitive function in patients with MCI.

Methods

Study design and participants

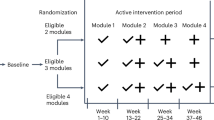

This study was a 52-week assessor-blind randomized controlled trial, conducted at Sacred Heart Hospital in Chuncheon, South Korea, recruited participants between October 2020 and September 2021. After enrollment, participants underwent a 52-week intervention period. Following the completion of the intervention, participants were followed up for an additional year. Participants were randomly assigned to either an intervention group, which received a multidomain intervention via a mobile application, or a control group, which received standard health care guidelines. Cognitive function assessments were conducted at baseline and at the 52-week follow-up.

The inclusion criteria were individuals aged over 60 years with at least one modifiable dementia risk factor. These risk factors included hypertension (systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mmHg)16, diabetes (random plasma glucose ≥ 200 mg/dL, fasting plasma glucose ≥ 126 mg/dL after 8 h of fasting, 2-hour plasma glucose ≥ 200 mg/dL during a 75 g oral glucose tolerance test, or hemoglobin A1c ≥ 6.5%)17, dyslipidemia (total cholesterol ≥ 240 mg/dL, LDL cholesterol ≥ 160 mg/dL, HDL cholesterol < 40 mg/dL, or triglycerides ≥ 200 mg/dL)18, obesity (body mass index ≥ 25 kg/m²)19, and metabolic syndrome (defined by the presence of a combination of factors, such as hypertension, high blood sugar, excess body fat around the waist [waist circumference ≥ 90 cm in men or ≥ 85 cm in women]20, and abnormal cholesterol levels)21. Additional risk factors included low education level (≤ 9 years of schooling) and physical inactivity (< 150 min of moderate-intensity activity per week, < 75 min of vigorous-intensity activity per week, or an equivalent combination of both)22. In addition, participants were required to have a z-score ≤ − 1.0 SD in at least one test of the Korean Version of the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Packet (CERAD-K) and a Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) global score of 0.5.

Exclusion criteria included a diagnosis of dementia, severe visual or hearing impairment, or communication difficulties. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before enrollment, and the study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Chuncheon Sacred Heart Hospital (CHUNCHEON 2020-09-005, 12/10/2021).

Randomization and masking

Participants were randomly assigned to either the intervention or control group using a computer-generated list of random numbers. A simple randomization method was applied, and the allocation sequence was managed by statisticians who were not involved in the study. Due to the nature of the intervention, blinding of participants was not feasible, but outcome assessors remained blind to the group assignments.

Procedures

Participants visited the hospital twice during the study period: at baseline and at the 52-week follow-up. CERAD-K was administered by trained clinical psychologists, and CERAD-K was used to assess the cognitive function of participants. The assessment packet consists of eight items: (1) verbal fluency (saying words from the animal category); (2) modified Boston naming test (naming of drawings); (3) mini-mental state examination (MMSE-KC); (4) word list memory (learning a visually presented list of 10 words through three trials); (5) word list recall (delayed word recall); (6) word list recognition (distinguishing words that have been learned previously from those that have not); (7) constructional praxis (copying figures); (8) constructional praxis recall (delayed figure recall); and (9) the trail making test (TMT)-A/B (connecting a circle within a label in a set time). A longer time to complete the TMT test indicated poor performance. These tests enabled us to assess the functional abilities of various cognitive domains: (1) general cognitive function using the MMSE-KC, (2) attention using the TMT-A test, (3) memory using word list memory, word list recall, word list recognition, and constructional praxis recall, (4) language using the modified Boston naming test, (5) visuospatial function using constructional praxis, and (6) executive function using the TMT-B test and word fluency.

Intervention

Intervention group

Multidomain interventions were conducted in the intervention group using a mobile application throughout the 52-week study period. Three interventions were administered to the intervention group: (1) Diet (2) Physical activity (3) Metabolic and vascular risk check and management. Concerning diet, participants were requested to send information regarding their diet three times a day. A nutritionist or research nurse provided feedback on the diet three times a week. Regarding physical activity, participants set their own physical activity goals. When participants achieved the target amount of activity, positive feedback was provided on the goal achievement rate and the effectiveness of the exercise. Alternatively, if the participant did not meet their target, feedback on this was provided, along with guidance to adjust the goal so that the participant could continue to use the program. Vascular and metabolic risk factors were measured at baseline through blood tests, weight measurement, and blood pressure measurement. Feedback on blood pressure and blood sugar was provided once a month or when blood pressure or blood sugar was outside the normal range as set by an internal medicine specialist (Fig. 1).

Control group

The control group intervention was conducted under the same conditions as the experimental group. The control group did not use the application and received face-to-face health management guidelines related to dementia prevention for approximately 20 to 30 min twice a year, at baseline and 52 weeks follow up. Specifically, the research team guided the participants on diet for dementia prevention, the benefits of regular physical activity, and management guidelines for preventing metabolic and vascular diseases.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the MMSE-KC score at the 52-week follow-up. The secondary outcome was the eight items included in the CERAD-K, excluding the MMSE-KC, at the 52-week follow-up: (1) Verbal fluency (score); (2) Modified Boston naming test (score); (3) Word list memory (score); (4) Constructional praxis (score); (5) Word list recall (score); (6) Word list recognition (score); (7) Constructional praxis recall (score); (8) TMT-A/B (seconds). The researchers asked the participants if they experienced any adverse events and recorded them.

Statistical analyses

To calculate the minimum sample size for the analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), we fixed the two-sided significance level at 5% and statistical power at 80%, with an effect size of 0.5 determined from a previous study23. Assuming a baseline–follow-up correlation of ρ = 0.70, the required sample size was 72 participants. Allowing for a 10% attrition rate, we set a recruitment target of 80 participants.

A χ2 test was performed to analyze the association between categorical variables, such as sex, education level, and APOE ε4 carriers. A two-sample t-test was performed if there was a mean difference between the two groups in age and MMSE-KC score, which are continuous variables. ANCOVA was performed to verify the impact of mobile multidomain interventions on the CERAD-K score at the 52-week follow-up, using the baseline measurement as a covariate.

This study used SPSS Statistics version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and R version 4.2.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) to analyze the data. Missing data were imputed using the multiple imputation chained equations (MICE) R package. For all tests, the significance level was set at 5% and two-tailed p-values are reported (Fig. 2).

Results

The demographic characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 2. There were no significant differences between the intervention group and the control group in age (p = .77), sex (p = .44), educational level (p = .44), APOE ε4 carrier status (p = .44), and MMSE-KC scores (p = .06).

Effectiveness of intervention is presented in Table 3. After adjusting for baseline measurements, analyses of intervention effectiveness revealed significant differences in MMSE-KC and modified Boston naming test scores between the intervention group and the control group at 52 weeks. The intervention group was found to have higher scores than the control group on both tests. A similar trend was seen for the TMT. However, no significant difference was found in the secondary outcomes, including verbal fluency, word list memory, constructional praxis, word list recall, word list recognition, and constructional praxis recall (Figs. 3 and 4).

There were no serious side effects associated with the intervention. Adverse events included stress and time burden, observed in 5% (4) and 3.8% (1) of participants, respectively.

A total of 9 (11.3%) individuals were lost to follow-up. The dropout rate was higher in the control group (7 participants, 77.8%) than in the intervention group (2 participants, 22.2%; p = .003). The reasons for withdrawal were health-related issues (6 participants, 67%), time burden or low motivation (2 participants, 22%), and death (1 participant, 1%) (Table S1).

Discussion

This clinical trial aimed to enhance cognitive function in patients with MCI at high risk of developing dementia through a mobile-based multidomain intervention. The mobile-based multidomain intervention was more effective at improving cognitive function than offline education was. The intervention group showed greater improvements in global cognitive function (MMSE-KC) and language function (modified Boston naming test) compared to the control group.

Prior studies have shown that multidomain interventions improve cognitive function in patients with MCI24. In this population, simultaneously modifying multiple modifiable dementia risk factors appears to be more effective than addressing single factors in isolation or training cognition alone25. On this basis, multidomain interventions are currently being implemented in MCI cohorts26. However, most of this work has relied on offline delivery, which entails spatial and temporal constraints. Using a mobile application enables investigators to remotely monitor patients’ progress and provide timely feedback at any time, allowing individuals with MCI to manage dementia risk factors in their own homes27,28. In studies of older adults at risk for cognitive decline, home-based interventions have produced cognitive training effects comparable to those of facility-based programs, with high retention in both groups—suggesting that, if adherence is maintained, home-based delivery can yield cognitive benefits similar to those achieved with offline, facility-based formats23. Multiple reports have also found that cognitive interventions delivered via mobile devices are equivalent to pencil-and-paper formats29,30. Moreover, mobile platforms permit ongoing monitoring of cognitive performance, enabling earlier detection of change and timely, tailored intervention31. Recently, mobile-based multidomain programs have also been reported to confer cognitive benefits32,33. Taken together, these observations support the effectiveness of multidomain interventions in maintaining cognitive function, with the added advantage of mobile accessibility.

In addition, we targeted patients with MCI who had risk factors for dementia but were not diagnosed with dementia. Focusing on individuals at risk of developing dementia is crucial because interventions to reduce risk are more likely to translate into cognitive benefits before extensive neurodegeneration occurs34,35. A recent meta-analysis reported that, among patients with dementia, multidomain interventions were the only approach associated with improvements in global cognition36, and accumulating evidence suggests that cognitive interventions yield diminishing returns as pathology advances34. This study demonstrated the effectiveness of improving cognitive function by providing multidomain intervention via mobile to patients with mild cognitive impairment, which is the previous stage of dementia. This is in line with the findings of prior research that demonstrated the efficacy of multidomain interventions for enhancing cognitive function prior to dementia diagnosis. This study also has notable strengths. It used a randomized controlled design, delivered the intervention over an extended 52-week period, and leveraged a mobile platform that enabled home-based access, remote monitoring, and timely feedback. Together, these features support the feasibility and potential effectiveness of mobile multidomain interventions for preventing cognitive decline in at-risk older adults.

Limitations

This study had some limitations. First, although adherence was not considered in the analysis of this study, it is important to note that digital interventions are significantly affected by adherence. Therefore, caution is needed when interpreting the data, as adherence can influence the outcomes of these interventions. Second, when implementing mobile multidomain interventions for the elderly, difficulties may arise due to limited digital literacy, and this study may be limited in that it did not reflect the digital literacy of the elderly37. Third, Although the baseline cognitive function was not statistically significant, the control group had a lower baseline score, and the small sample size may have influenced the results. Therefore, caution is required when interpreting the findings. Fourth, we did not conduct pre-study usability testing of the application, which may have introduced interface-related barriers, reduced adherence, and limited generalisability. However, this study attempted to compensate for this limitation by continuously educating the research nurse on the application and how to use smart devices effectively and on the application.

Conclusions

Our trial provides evidence that mobile multidomain interventions are an effective method for decreasing the risk of dementia in patients with MCI. Mobile technologies that support daily activities and health can compensate for decreased function owing to dementia. Additional research is required to confirm the effect of multidomain interventions on dementia prevention based on patient compliance.

Data availability

The data used in this study contain identifiable or sensitive patient information and cannot be shared publicly due to restrictions from the Ethics Committee of Chuncheon Sacred Heart Hospital. However, the dataset used and analyzed during the current study is available from the corresponding author on a reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- MCI:

-

Mild cognitive impairment

- MMSE-KC:

-

Mini-mental state examination in the Korean version of the consortium to establish a registry for Alzheimer’s disease assessment packet

- eHealth:

-

Electronic health

- CERAD-K:

-

Korean version of the consortium to establish a registry for Alzheimer’s disease assessment packet

- TMT:

-

Trail making test

- ANCOVA:

-

Analysis of covariance

- MICE:

-

Multiple imputation chained equations

References

Petersen, R. C. et al. Mild cognitive impairment: clinical characterization and outcome. Arch. Neurol. 56 (3), 303–308 (1999).

Cao, J. et al. Advances in developing novel therapeutic strategies for alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Neurodegeneration. 13, 1–20 (2018).

Cummings, J. et al. Drug development in alzheimer’s disease: the path to 2025. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 8, 1–12 (2016).

Hu, M. et al. Effects of computerised cognitive training on cognitive impairment: a meta-analysis. J. Neurol. 268 (5), 1680–1688 (2021).

Karssemeijer, E. G. A. et al. Positive effects of combined cognitive and physical exercise training on cognitive function in older adults with mild cognitive impairment o r dementia: A meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 40, pp. 75–83 .

Demurtas, J. et al. Physical activity and exercise in mild cognitive impairment and dementia: an umbrella review of intervention and observational studies. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 21 (10), 1415–1422e6 (2020).

Coelho-Júnior, H. J., Trichopoulou, A. & Panza, F. Cross-sectional and longitudinal associations between adherence to mediterranean diet with physical performance and cognitive function in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 70, 101395 (2021).

Cooper, C. et al. Modifiable predictors of dementia in mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Psychiatry. 172 (4), 323–334 (2015).

Ngandu, T. et al. A 2 year multidomain intervention of diet, exercise, cognitive training, and vascular risk monitoring versus control to prevent cognitive decline in at-risk elderly people (FINGER): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 385 (9984), 2255–2263 (2015).

Andrieu, S. et al. Effect of long-term Omega 3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation with or without multidomain intervention on cognitive function in elderly adults with memory complaints (MAPT): a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 16 (5), 377–389 (2017).

van Charante, E. P. M. et al. Effectiveness of a 6-year multidomain vascular care intervention to prevent dementia (preDIVA): a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 388 (10046), 797–805 (2016).

Salzman, T. et al. Associations of multidomain interventions with improvements in cognition in mild cognitive impairment: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open. 5 (5), e226744 (2022).

McNamee, P. et al. Designing and undertaking a health economics study of digital health interventions. Am. J. Prev. Med. 51 (5), 852–860 (2016).

Mehregany, M. & Saldivar, E. Opportunities and obstacles in the adoption of mHealth. in mHealth. pp. 7–20. (HIMSS Publishing, 2020).

Beishuizen, C. R. et al. Web-based interventions targeting cardiovascular risk factors in middle-aged and older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Med. Internet. Res. 18 (3), e5218 (2016).

Lee, S., et al. Korea hypertension fact sheet 2018. Clin. Hypertens. 24, 1–4 (2018).

Bae, J. H. et al. Diabetes fact sheet in Korea 2021. Diabetes Metabolism J. 46 (3), 417–426 (2022).

Cho, S. M. J. et al. Dyslipidemia fact sheets in Korea 2020: an analysis of nationwide population-based data. J. Lipid Atherosclerosis. 10 (2), 202 (2021).

Nam, G. E. et al. Obesity fact sheet in Korea, 2020: prevalence of obesity by obesity class from 2009 to 2018. J. Obes. Metabolic Syndrome. 30 (2), 141 (2021).

Lee, S. Y. et al. Appropriate waist circumference cutoff points for central obesity in Korean adults. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 75 (1), 72–80 (2007).

Huh, J. H. et al. Metabolic syndrome fact sheet 2021: executive report. CardioMetab. Syndr. J. 1 (2). (2021).

Strain, T. et al. National, regional, and global trends in insufficient physical activity among adults from 2000 to 2022: a pooled analysis of 507 population-based surveys with 5·7 million participants. Lancet Global Health. 12 (8), e1232–e1243 (2024).

Moon, S. Y. et al. Facility-based and home-based multidomain interventions including cognitive training, exercise, diet, vascular risk management, and motivation for older adults: a randomized controlled feasibility trial. Aging (Albany NY). 13 (12), 15898–15916 (2021).

Kulmala, J. et al. The effect of multidomain lifestyle intervention on daily functioning in older people. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 67 (6), 1138–1144 (2019).

Hafdi, M., Hoevenaar-Blom, M. P. & Richard, E. Multi-domain interventions for the prevention of dementia and cognitive decline. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 11 (11), CD013572 (2021).

Kivipelto, M. et al. A global approach to risk reduction and prevention of dementia. Alzheimers Dement. 16 (7), 1078–1094 (2020).

Ianculescu, M., Paraschiv, E. A. & Alexandru, A. Addressing mild cognitive impairment and boosting wellness for the elderly through personalized remote monitoring. Healthc. (Basel) 10 (7). (2022).

Sabbagh, M. N. et al. Early detection of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) in an At-Home setting. J. Prev. Alzheimers Dis. 7 (3), 171–178 (2020).

Marin, A. et al. Home-Based electronic cognitive therapy in patients with alzheimer disease: feasibility randomized controlled trial. JMIR Form. Res. 6 (9), e34450 (2022).

Ha, J. Y. & Park, H. J. Effects of mobile-based cognitive interventions for the cognitive function in the community-dwelling older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 104, 104829 (2023).

Mattli, R. et al. Digital multidomain lifestyle intervention for Community-Dwelling older adults: A mixed methods evaluation. Int. J. Public. Health. 70, 1608014 (2025).

Kim, J. et al. The effects of a mobile-based multidomain intervention on cognitive function among older adults. Prev. Med. Rep. 32, 102165 (2023).

Kim, Y. et al. The efficacy of a mobile-based multidomain program on cognitive functioning of residents in assisted living facilities. Public. Health Pract. (Oxf). 8, 100528 (2024).

Crous-Bou, M. et al. Alzheimer’s disease prevention: from risk factors to early intervention. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 9 (1), 71 (2017).

Sindi, S., Mangialasche, F. & Kivipelto, M. Advances in the prevention of Alzheimer’s disease. F1000Prime Rep. 7, p. 50. (2015).

Huntley, J. et al. Do cognitive interventions improve general cognition in dementia? A meta-analysis and meta-regression. BMJ open. 5 (4), e005247 (2015).

Wilson, S. A. et al. A systematic review of smartphone and tablet use by older adults with and without cognitive impairment. Innov. Aging. 6 (2), igac002 (2022).

Funding

This work was partly supported by a National Information Society Agency grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (No. 260026044211652222001010G, Big Data Platform and Network Building Project), a National Research Foundation of Korea grant funded by the Korean government (NRF-2022R1A2C1011286), the Korea government (the Ministry of Science and ICT, the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy, the Ministry of Health & Welfare, the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety, Project Number: 2710002716, RS-2023-00254839) and the Hallym University Research Fund. The funders did not influence the design of the study, data collection, analysis, or writing of the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.Y.C.: the interpretation of the data, manuscript drafting, and statistical analysis.Y.J.K.: the data acquisition, interpretation of the data, and revision of the manuscript.D.S.S.: the statistical analysis, interpretation of the data, and revision of the manuscript. M.E.A.: the conceptualization, design, and data acquisition.S.K.L.: the conceptualization and design, data acquisition, interpretation of the data, and revision of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Choi, H.Y., Kim, Y.J., Son, DS. et al. Effectiveness of a 52-week multidomain intervention to maintain cognitive function in patients with mild cognitive impairment: a randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep 15, 41141 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24865-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24865-0