Abstract

The usual macroscopic Cooper pairs systems, the superconductors, very weakly interact with the visible light since self-existing superconducting currents screen the light penetration into the samples. However, the superinsulators whose superinsulating behavior is caused by localization of Cooper pairs demonstrate significant interaction with light. As a result, superinsulating films, in particular, the NbTiN films, offer a remarkable and unique platform for constructing high sensitivity light detector working at superlow millikelvin temperatures. Irradiating the NbTiN film with a visible light when the film is in the insulating state results in the emergence of a measurable current through this NbTiN-based insulator. It was found that this light-induced current depends on the radiation intensity and thus opens an opportunity for high precision measurements of the light intensity. The induced current disappears with an increase of temperature and light wavelength.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Macroscopic systems containing Cooper pairs, the superconductors, usually weakly react to external light radiation, since the reaction of the normal carriers to the light, for which the destruction of Cooper pairs is necessary, is shunted by superconducting currents. The superinsulating films1,2,3, that are the novel systems containing Coper pairs, are an excellent object opening opportunities for studying the interaction of Cooper pairs with the light because the light-induced destruction of Cooper pairs in superinsulators leads to several easily observable effects. Most important effect is the appearance of charge carriers above the energy gap, which allows a non-zero current to flow even through the samples with an immeasurably large resistance. This results in the formation of a conducting layer, which significantly changes the non-linear transport in the superinsulator.

The superinsulating state forms at ultra-low temperatures in the vicinity of the well-studied superconductor-insulator transition (SIT)1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18. One of the observed characteristics of the superinsulating state is the hyperactivation temperature dependences of the resistance of films located near the superconductor-insulator transition1,2,3. It was found that both these states, insulating and superinsulating, are characterized by a critical magnetic field \(B_\textrm{cr}\) and a threshold voltage \(V_\textrm{th}\) above which insulator becomes a metal. Also, in superinsulating films, a critical transition temperature in thin TiN and NbTiN films was observed to be the Berezinskii-Kosterlitz-Thouless charge transition temperature, \(T_\textrm{BKT}\)19. Recently, it was found that the destruction of the superinsulating state under the influence of a voltage greater than \(V_\textrm{th}\), i. e. the appearance of a measurable current, occurs in a time of about several microseconds20,21. It is assumed that in both, the insulating and superinsulating states, an energy gap in the density of states is formed, which is reminiscent to the emergence of such a gap in conventional insulators and semiconductors. In this case, the Cooper pairs, due to emerging of which the formation of this gap does occur, are localized and cannot transfer charge. Basing on these observations, one can expect the emergence of free charge carriers under the influence of an external radiation both due to the transfer of normal electrons to the conduction band and due to the destruction of Cooper pairs. Our paper presents for the first time the results of such an experimental study of the response of the superinsulating Nb\(_{0.67}\)Ti\(_{0.33}\)N film to a constant laser radiation in the optically visible range.

Samples

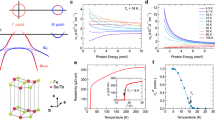

We execute the experimental study of the Nb\(_{0.67}\)Ti\(_{0.33}\)N films grown by an atomic layer deposition at a temperature of 350\(^{\circ }\)C. Details of the film production are given in19. The film thicknesses were decreased from \(d = 10\) nm to \(d = 8-9\) nm by plasma etching. As we shown previously this is critical thickness for realization disorder driven superconductor-insulator transition at low temperatures15. The low-temperature properties of the films are studied in the samples fabricated by a photolithography in the form of Hall bridges that are 50 \(\mu\)m wide. The distance between the voltage contacts is 450 \(\mu\)m, the distance between the current contacts is 2.5 mm. Low-temperature experiments are carried out in a \(^3\)He/\(^4\)He dilution cryostat. To measure the resistance of the fabricated structure, a two-point connection scheme is used at an alternating voltage of \(V\approx 100\) \(\mu\)V having a low frequency of about \(f=1\) Hz with using lock-in amplifier SR830. The number of squares between current contacts is determined by comparing the measurements of the temperature dependence of resistance using the two-point and four-point schemes in the temperature range of 4.2 - 77 K. In this temperature range, the sheet resistance does not depend on the distance between the contacts. The four-point measurement scheme used voltage contacts with a distance of 450 \(\mu\)m between them (film wide is 50 \(\mu\)m). Figure 1 shows the temperature dependence of the resistance per square for the chosen NbTiN films. All films show insulating behavior of the resistance below 3 K. Analysis of the current-voltage dependencies shows that at temperatures below 150 mK, a superinsulating state with a threshold behavior of the current-voltage dependencies is in all samples. Note that threshold voltage increased with increasing disorder of sample from 90 mV to 4 V. Simultaneously, the voltage induced transition from the superinsulating to the normal state is blurred (see18). To determine the response to the radiation, a uniform illumination of the sample obtained with lasers with wavelengths of 457, 514, and 850 nm is used. Homogeneous illumination was ensured by scattering the laser beam on a metal reflector. The current arising in the circuit is measured using a low-noise SR570 preamplifier and an Agilent 34420a nanovoltmeter, to check the measurement results was used Keithley SourceMeter 6430. In addition, an analysis is made of the effect of a contact resistance at the point of soldering the contacts using indium contact on the superinsulator. For this purpose, a control superinsulating samples were manufacture. In a superconducting film using an electron-beam lithography and plasma-chemical etching we create local area with small thickness, where superinsulating state is appear. Thus, the contacts were soldered using indium to the superconducting film, which seamlessly transitioned into the superinsulator. Measurements of superinsulators created in this way showed no differences between their properties and the properties of superinsulators without superconducting contacts. So, we found that properties of superinsulator do not depend on type of contacts.

Results

At the first stage of the experiment, we consider the evolution of the superinsulating state under the action of an external radiation with a wavelength corresponding to visible light. In particular, Figs. 2 and 3 show the current-voltage characteristics for two different type of superinsulator measured at a temperature of 20 mK and different radiation levels. The main difference between these two types of superinsulators is the threshold behavior of the current-voltage dependences. Superinsulators with a low degree of disorder demonstrate a sharp threshold behavior, while in superinsulators with a high degree of disorder, a smooth threshold behavior of the current-voltage dependences is observed. In both cases, a change in the behavior of the current-voltage dependences from a power law to a linear one with increasing light power is observed, which is characteristic of the BKT charge transition. Note that 1 nW of power at the input to the cryostat approximately corresponds to 10 photons per second per sample area. The assessment is carried out using a semiconductor detector. Let’s start with a first type of superinsulator with a low degree of disorder (see Fig. 3a). An increase in the radiation power from 0 to 1 \(\mu\)W leads to a decrease in the threshold voltage. In the power range of 1–4 \(\mu\)W, a change in the nature of the current-voltage characteristics at voltages below the threshold from a power to a linear one is observed. Then, at a light power level of 128-256 \(\mu\)W, the threshold behavior is suppressed and the current-voltage characteristics of insulators appear. A subsequent increase in the light power leads to an increase in the film conductivity and then to the destruction of the insulator state, which is expressed in the linearization of the current-voltage characteristics. Increasing disorder to a value at which the type of superinsulator changes to the second does not lead to a qualitative change in the evolution of current-voltage characteristics (see Fig. 3b). At the same time, the threshold values of light power necessary for the destruction of the superinsulating state decrease with an increase in the degree of disorder of the superinsulator. At first glance this behavior is similar to the temperature destruction of a Cooper insulator. However, the destruction/restoration time of the superinsulator and insulator states under the action of light appears to be about 40-50 \(\mu\)s, see the inset in Fig. 2, which is over several orders of magnitude less than the destruction/restoration time of the superinsulator state under the action of temperature and an order of magnitude greater than the destruction time of the superinsulator state by an electric field, observed earlier20,21. In addition, there is a significant difference in the behavior of the current-voltage dependences at temperatures near the BKT transition and under the influence of light. Moreover, special measurements have shown that the temperature of the sample under the influence of light exceeds 200 mK at radiation power levels above 128 \(\mu\)W, which is almost two orders of magnitude higher than the radiation power required to destroy the superinsulating state. For clarity, we have added symbols to Fig. 3 showing the behavior of the current-voltage dependence near the BKT transition by temperature. It is evident that, unlike the light-induced BKT transition, the temperature transition occurs simultaneously with the blurring of the threshold behavior of the current-voltage dependence. Apparently, this is due to the fact that the superinsulating state is destroyed in a thin layer near the film surface, which leads to the linearization of the measured current-voltage dependence, despite the fact that most of the sample remains superinsulating.

Current-voltage characteristics of sample I1 at a temperature of 20 mK under illumination with light of a wavelength of 850 nm of different power levels. At a light power level above 4 mW, the current-voltage characteristics become linear, which corresponds to the destruction of the insulating state. The inset shows the time process of destruction/restoration of the superinsulator state under the action of radiation with a power of 1 mW. I(0) is current at zero-voltage.

Current-voltage characteristics in a double logarithmic scale at a temperature of 20 mK under illumination with light of a wavelength of 850 nm of different power levels for two different type of superinsulator. Symbols are shown current-voltage dependencies at temperatures near \(T_\textrm{BKT}\) without light. The solid straight lines show the calculated power dependences of current on voltage with different exponents. I(0) is current at zero-voltage. (a) Superinsulator with sharp threshold behavior. At a light power level of 1–4 \(\mu\)W, a change in the nature of the current-voltage characteristics at voltages below the threshold from a power to a linear one is observed. At a light power level of 128–256 \(\mu\)W, suppression of the threshold behavior is observed. (b) Superinsulator with soft threshold behavior. At a light power level of 0.5–1 \(\mu\)W, a change in the nature of the current-voltage characteristics at voltages below the threshold from a power to a linear one is observed.

Thus, it can be assumed that under the action of light not only the destruction of the coherent state of localized Cooper pairs occurs, but also the destruction of the Cooper pairs themselves.

Current through six NbTiN insulator films at 20 mK induced by light pulses. For samples I1, I2, I4, I5, I6 are shown only at wavelength 850 nm. For sample I3 are shown at wavelengths 457, 514, and 850 nm. Solid lines are shown change in the exponent in power dependence of induced current from light power.

In the next series of experiments, no voltage sources connected to the sample are used, and the sample is cooled to a temperature of 20 mK. It is found that switching on external radiation resulted in a measurable current flow. When the radiation is switched off, the current returns to its initial value, see Fig. 4, which do not change over time. Increasing the radiation intensity , i.e., power, to 4 mW resulted in an increase in the amplitude of the current flowing through the system. Analysis of the obtained dependence of the current on the power shows that the current= depends on the radiation power in a power-law manner (see Fig. 5). Moreover, the exponent changes at an intensity above 256 \(\mu\)W. At the same time, an extended region of current relaxation appears in the current dependence on time after switching off the illumination. The length of this region increases with increasing light power. Similar power-law dependences of the photocurrent on the radiation intensity were observed, for example, in topological insulators22. With an increase in the radiation power above 4 mW, the current growth stops and, moreover, with prolonged irradiation, a sharp decrease in the current value occurred down to negative values. In other words, the current changes its direction. Note that this corresponds to the region of light power, at which the linearization of the current-voltage dependencies occurs. The analysis of the current-voltage dependencies shows that at a radiation power above 256 mW, the sample begins to heat up. Apparently, this heating first leads to a change in the exponent in the dependence of the current on the light intensity, and then, upon reaching the destruction temperatures of the Cooper insulator, to a decrease in the current up to the appearance of its negative values. Note that prolonged illumination of the sample with light with a power level above the critical one ultimately leads to the zeroing of the observed current. At the same time, since the process of heating the sample takes much more time than the generation of charge carriers, then immediately after turning on the light at any values of its intensity, we first observe a positive current value, which then decreases within a few minutes. Note that increasing the disorder in the film, i.e. moving it away from the disorder driven superconductor-insulator transition, leads to a decrease of the light-induced current. This agrees well with the model of Cooper pair destruction, since the farther the film is from the superconductor-insulator transition, the fewer Cooper pairs it contains.

These results pose the following questions:

-

1.

Is the observed current really the current flowing through the sample, or is there only a light induced electric field in the system, which generates the current flowing through the internal resistor of the current amplifier and the charging capacitor? To answer this question, we carry out comparative measurements over a long period of time at sensitivities of \(10^{-8}\) and \(10^{-9}\) of the current amplifier, corresponding to resistors of 10 k\(\Omega\) and 1 M\(\Omega\), respectively, see SI figure 1. The obtained current values do not differ and do not change over time with an accuracy of up to the noise of the circuit, which indicates that the direct current flows directly through the sample, meaning that the sample does not work as a capacitor. This is also consistent with the destruction of the superinsulating state under the influence of light as shown in the Fig. 2.

-

2.

The next fundamental question is: What does the direction of the current depend on? To determine the parameters that define the direction of the current, the comparative measurements are carried out with different contact arrangements, as well as with the inclusion of additional voltage sources, the voltages of which exceeds the parasitic voltages in the measuring circuit. Experiments show that the direction of the photocurrent is determined only by the location of the contacts and does not depend on the external voltage sources, see SI figure 2. Thus, the direction of the photocurrent is apparently determined by the internal structure of the studied film.

-

3.

And the final fundamental question is: Is the photocurrent a property of the film or it arises due to the contaminants on its surface? To resolve this problem, a series of experiments are conducted with the introduction of a number of the contaminants. These experiments show that the surface contaminants lead to a weakening of the photocurrent with a simultaneous increase in the overheating of the system under study, see SI figure 3.

As a next step, we investigate the evolution of the photocurrent with a change in the wavelength of light. A decrease of the radiation wavelength to 457 nm does not cause qualitative changes in the current-voltage dependences and photocurrent, while a quantitative comparison is hard due to an unclear dependence of the reflection/absorption coefficients of the NbTiN film on the light wavelength (see Fig. 5). If the value of the cryostat heating by the light radiation is used as a normalizing parameter, the photocurrent value and characteristic threshold values of light power turn out to be practically independent of the wavelength in the range from 457 to 850 nm. When using nearly infrared radiation with a wavelength of more than 2000 nm, no photocurrent was recorded at any radiation power levels that do not lead to physical heating of the system. The destruction of the superinsulating and insulating states with an increase in the infrared radiation power coincided with the temperature heating of the system. Thus, the photocurrent is apparently associated with the destruction of Cooper pairs, and not with the transition of normal electrons through the energy gap. In this case, the energy of the forbidden band formed by localized Cooper pairs does not exceed 0.6 eV.

An increase of temperature in the range of 0.02–0.4 K does not lead to a sufficient decrease in the photocurrent. Then, at temperatures above 0.4 K, the photocurrent decreases until it practically disappears at temperatures above 1 K. Note that by a decrease in the photocurrent we mean both its decrease at a fixed radiation power and the maximum possible photocurrent in the system. In addition, with an increase in temperature, a decrease in the value of the light power is observed, corresponding to the maximum photocurrent. In the Fig. 6 which represents a limiting case, the photocurrent is shown at different levels of visible light power at a temperature of 1.2 K. When the light is turned on, the short-term current surges are observed, indicating some processes occurring in the system. However, a measurable current with a negative amplitude is observed only at light powers less than 4 \(\mu\)W, which agrees well with the practically linear form of the current-voltage dependence at such temperatures and the previous results in Fig. 3. Also, such a behavior is well explained within the framework of the hypothesis about the connection of photocurrent with the destruction of Cooper pairs by photons of the visible spectrum, in the case when the heterogeneity arising in the system is associated precisely with the heterogeneity of the superconducting gap, and not with structural heterogeneities in the sample. For a better understanding of the processes occurring, it is necessary to create and study superinsulators with controlled heterogeneity.

Conclusion

Our experiments established that the irradiation of strongly disordered NbTiN films with scattered coherent light of the visible spectrum leads to the appearance of a photovoltaic effect at temperatures corresponding to the appearance of a superinsulator state and an insulator state with Cooper pairing. That is, to the flow of measurable current even in the presence of a superinsulating phase. A sharp change in the nature of the photocurrent outside the region of existence of an insulator with Cooper pairing is demonstrated. It is shown that an increase in the radiation power leads to the destruction of both, the superinsulating and insulating states. An assumption is made about the causality of these effects by the presence of localized Cooper pairs in the system and their destruction under the action of light of the visible spectrum. An estimate is made of the global forbidden energy band caused by the localization and synchronization of Cooper pairs.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Vinokur, V. M. et al. Superinsulator and quantum synchronization. Nature 452, 613 (2008).

Burdastyh, M. V. et al. Dimension effects in insulating NbTiN disordered films and the asymptotic freedom of Cooper pairs. JETP Lett. 109, 795 (2019).

Ovadia, M. et al. Evidence for a finite-temperature insulator. Sci. Rep. 5, 13503 (2015).

Ovadia, M., Sacépé, B. & Shahar, D. Evidence for a finite-temperature insulator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 176802 (2009).

Shalnikov, A. I. Superconducting thin films. Nature 142, 74 (1938).

Strongin, M., Thompson, R. S., Kammerer, O. F. & Crow, J. E. Destruction of superconductivity in disordered near-monolayer films. Phys. Rev. B 1, 1078 (1970).

Gold, A. Dielectric properties of a disordered Bose condensate. Phys. Rev. A 33, 652 (1986).

van der Zant, H. S. J., Fritschy, F. C., Elion, W. J., Geerligs, L. J. & Mooij, J. E. Field-induced superconductor-to-insulator transitions in Josephson-junction arrays. Phys. Rev. Lett. 69, 2971 (1992).

Goldman, A. M. & Marković, N. Superconductor-insulator transitions in the two-dimensional limit. Phys. Today 51, 39 (1998).

Krämer, A. & Doniach, S. Superinsulator phase of two-dimensional superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 81, 3523 (1998).

Altshuler, B. L., Kravtsov, V. E., Lerner, I. V. & Aleiner, I. L. Jumps in current-voltage characteristics in disordered films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 176803 (2009).

Gantmacher, V. F. & Dolgopolov, V. T. Kvantovyi fazovyi perekhod sverkhprovodnik –izolyator. UFN 180, 3 (2010).

Feigelman, M. V., Ioffe, L. B., Kravtsov, V. E. & Cuevas, E. Fractal superconductivity near localization threshold. Ann. Phys. 325, 1390 (2010).

Goldman, A. M. Superconductor-insulator transitions. Intern. J. Mod. Phys. B 24, 4081 (2010).

Burdastyh, M. V. et al. Superconductor-insulator transition in NbTiN films. JETP Lett. 106(11), 749–753 (2017).

Diamantini, M. C., Trugenberger, C. A. & Vinokur, V. M. Confinement and asymptotic freedom with Cooper pairs. Comm. Phys. 1, 77 (2018).

Diamantini, M. C., Trugenberger, C. A. & Vinokur, V. M. Topological gauge theory of the superconductor-insulator transition, in Topological Phase Transitions and New Developments. World Scientific 197, 14223 (2019).

Diamantini, M. C. et al. Direct probe of the interior of an electric pion in a Cooper pair superinsulator. Comm. Phys. 3, 142 (2020).

Mironov, AYu. et al. Charge Berezinskii-Kosterlitz-Thouless transition in superconducting NbTiN films. Sci. Rep. 8, 4082 (2018).

Durakov, D. E., Derebezov, I. A., Vinokur, V. M. & Mironov, A. Y. Specific features of the destruction of a superinsulating state by voltage pulses in NbTiN films. JETP Lett. 114, 76 (2001).

Mironov, A., Diamantini, M. C., Trugenberger, C. A. & Vinokur, V. M. Relaxation electrodynamics of superinsulators. Sci. Rep. 12, 19918 (2022).

Huang, S.-M. et al. Highly responsive photoconductance in a Sb\(_2\)SeTe\(_2\) topological insulator nanosheet at room temperature. RSC Adv. 7, 39057 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to T. Proslie for providing initial films for the experiments and to M. C. Diamantini and C. A. Trugenberger for nice and fruitful discussions.

Funding

The work was supported by Terra Quantum AG.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.M. and V.V. conceptualized manuscript, A.M. carried out experiments, A.M. and V.V. wrote and reviewed manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mironov, A., Vinokur, V. Light-induced current in Cooper pair insulators in NbTiN films. Sci Rep 15, 41074 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24907-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24907-7