Abstract

As organizations confront a continuously evolving threat landscape, advanced adversarial techniques are increasingly capable of evading traditional continuous monitoring, allowing attackers to remain concealed within environments for extended periods. Industry studies report an average detection time exceeding six months, with many compromises first discovered by third parties rather than internally. Compromise Assessment, a proactive approach to determine if an environment is or has been compromised, has emerged as a way to uncover these threats. However, existing practices remain fragmented, are often conflated with threat hunting, and continue to lack a standardized methodological foundation. Together, these issues, combined with the absence of clear CA frameworks, undermine practitioners’ ability to provide consistent and reliable assurance in answering the central question of whether an environment is or has been compromised. To address these challenges, this research introduces PROID, a novel, comprehensive, and data-driven Compromise Assessment framework. PROID integrates Threat Intelligence and Threat Hunting through a multi-layered analytical approach, combining signature-based and signature-less hunting, automated pattern recognition, and human-led analysis. In a simulated enterprise environment, PROID was tested against thirty-one MITRE ATT&CK techniques spanning ten tactics across host, network, and application layers. The framework successfully detected all thirty-one techniques, including persistence, defense evasion, and anti-forensics behaviors that other methodologies did not consistently identify. These results demonstrate PROID’s breadth of detection and its effectiveness in unifying diverse analysis methods within the framework to reach the desired goal. Beyond technical performance, PROID establishes a standardized and reproducible basis for Compromise Assessment, addressing ambiguity with threat hunting and offering organizations a practical means of conducting periodic assurance of compromise status. Its integration with incident response processes and its emphasis on scope definition and telemetry baselining make it a valuable reference model to complement real-time monitoring and strengthen organizational resilience against advanced threats.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Modern cyber advanced threat actors pursue long-term objectives such as espionage, intellectual property theft, supply-chain sabotage or establishing a hidden presence for future operations, which makes detection and containment increasingly difficult. Among these threat actors, Advanced Persistent Threats (APTs) represent organized, determined and capable adversaries that leverage sophisticated post-compromise persistence and defense evasion techniques1 to maintain access over extended periods2. The risk of these threats increases with the modern complexity of large organizations Information Technology (IT) infrastructures that could encompass a wide range of technologies and devices, creating wider attack surface and potential blind spots that challenge effective security monitoring.

The challenges posed by these persistent threats are underscored by analyses of breach detection timelines. In cybersecurity, most defensive solutions and measures aim to prevent attacks or detect them while they are in progress. Yet a significant gap persists, where some intrusions can evade detection measures or may have originated before certain security controls were implemented. This raises a critical question: how can organizations reliably uncover compromises that are already present in their environments, whether ongoing or historical? Numerous Cyber Threat Intelligence (CTI) reports3,4,5,6,7 have documented intrusions that persisted for years without detection, highlighting the urgent need for methods capable of addressing this gap.

Reports reveal the average detection time exceeds six months8,9,10, with only 33% of incidents identified internally by organizations, and the remaining 67% discovered through third-party notifications or attacker disclosures. Extended detection delays amplify financial and reputational damages, whereas early internal detection significantly mitigates these risks11,12. This prolonged attacker dwell time, the period between initial compromise and detection, emphasizes the critical need for enhanced detection mechanisms.

Real-world cases illustrate the impact of prolonged compromises. The SolarWinds Orion breach, undetected for over a year from initial compromise in September 2019, affected approximately 18,000 organizations3. Similarly, the UK Electoral Commission breach from August 2021 to October 2022 exposed personal data of about 40 million individuals4,5. Additionally, a cyber espionage campaign targeting Taiwan’s financial sector persisted for 18 months, highlighting vulnerabilities in prolonged attacks6.

These examples underscore the urgency for proactive defense practices against sophisticated cyber threats. Traditional security solutions relying on reactive detection mechanisms frequently fail against stealthy adversaries using advanced evasion methods13. Consequently, proactive cybersecurity strategies, including Threat Hunting, Continuous Monitoring, Vulnerability Assessment, Red Teaming, Cyber Threat Intelligence (CTI), and Compromise Assessment (CA), have become essential to preempt and mitigate threats before significant breaches occur.

CA is a critical element in proactive cybersecurity, significantly reducing incident detection times and minimizing organizational impact. Despite availability from various cybersecurity providers, existing CA practices lack consistency, leading to varying outcomes and reliance on subjective analyst expertise. Additionally, confusion often arises between CA and hypothesis-driven Threat Hunting methodologies. A CA primarily aims to answer, "Am I compromised, or have I been?"14 This research introduces a structured framework to provide accurate and reliable responses.

The proposed PROID framework offers comprehensive guidance covering the complete assessment lifecycle, from preparation through reporting. It includes five phases: preparation, planning, deployment, analysis, and reporting. The preparation phase establishes clear assessment contexts, stakeholder roles, and technical or legal requirements. The planning phase integrates insights from Cyber Threat Intelligence to form Threat Hunting hypotheses and defines the assessment’s scope and required tools, including integration plans for Incident Response. Deployment ensures tools are effectively implemented for data analysis. Analysis involves four comprehensive techniques: signature-based threat hunting, signature-less threat hunting, automated pattern recognition, and thorough human-led analysis. Finally, the reporting phase documents assessment findings and recommended corrective actions.

This paper begins with this framework introduction, followed by a literature review on proactive detection and incident response, clarifying distinctions between CA and Threat Hunting, and reviewing current commercial CA practices. Subsequent sections detail the PROID framework, validate its effectiveness through a simulated environment utilizing 31 MITRE ATT&CK techniques15, and conclude with recommendations for future research.

Background and related work

Proactive incident detection and response

Proactive Incident Detection and Response, which include activities such as CA and TH, have an important place in modern cybersecurity strategies. It emphasizes the active identification and mitigation of potential compromises to prevent substantial negative effects in an early stage16. The main goal of this proactive act is to address threats that remain undetected within networks for prolonged periods. Recent findings in IBM Data Breach report17 Illustrates concerning statistics about the meantime taken to detect and contain data breach incidents, where organizations are taking an average of 277 days, exposing large window that might enable adversaries to spread in the environment, deploy persistence mechanisms, understand the environment normal activities to blend in, to eventually achieve most of their objectives. Moreover, other studies illustrate a significant gap in organizations’ ability to detect their own incidents, where organizations were notified of breaches by external entities in 63% of incidents18. These findings, alongside the advanced capabilities and enduring persistence of APTs, underscore the imperative to adopt Proactive Incident Detection and Response strategies19. This approach is crucial for identifying incidents with minimized impact, effectively addressing the sophisticated nature of such threats.

Threat hunting

Threat Hunting is essential practice in proactive defense, as it enables the detection of hidden adversarial activities that evade traditional security systems. It relies on constructing hypotheses to guide analysts in exploring organizational data to uncover anomalies and behavioral patterns20,21.

Several frameworks illustrate the development of threat hunting methodologies:

-

TaHiTI (Van der Heijden et al.18) follows a hypothesis-driven structure divided into Initiate, Hunt, and Finalize phases, focusing on transforming CTI into hunting opportunities. While flexible, it may fall short against zero-day threats due to its reliance on predefined hypotheses.

-

PEAK Framework (Splunk22) defines Hypothesis-Driven, Baseline, and Model-Assisted threat hunts, incorporating both behavioral baselines and machine learning to identify anomalies. Hypothesis-driven hunts rely on a blend of research and analyst intuition to test specific threat scenarios. Baseline hunts aim to define what constitutes normal activity in an organization’s environment, helping to flag deviations that could signal threats. Model-Assisted hunts enhance these efforts by applying machine learning algorithms to detect subtle patterns across large datasets. The PEAK framework outlines structured steps to prepare for, execute, and learn from threat hunts, promoting a disciplined, repeatable process that helps organizations improve their threat detection maturity over time.

-

Behavior-Based Threat Hunting (BTH) (Bhardwaj et al.23) focuses on attacker behaviors rather than static IoCs, improving the detection of evolving threats. By analyzing behavioral patterns and leveraging threat intelligence, it identifies anomalies missed by static methods and supports ongoing enhancement of detection capabilities.

-

POIROT (Milajerdi et al.24) constructs kernel-level provenance graphs for CTI-driven detection, using audit logs to map relationships between system entities and detect malicious behavior. It translates threat intelligence into graph models that reveal hidden patterns and adversary activity, offering resilience against tactic changes and improving detection accuracy, provided the kernel remains uncompromised.

Recent systematic reviews further highlight this lack of standardization. Mahboubi et al.25a conducted a comprehensive survey of threat hunting techniques, noting that while AI-driven models and advanced analytics are increasingly integrated into hunting practices, a critical gap persists in establishing standardized, reproducible methodologies across organizations. Bhardwaj et al.26 introduced a proactive threat hunting methodology using an Elasticsearch-based SIEM to detect persistent, behavior-driven adversaries. Their work shows the value of SIEM-integrated hunting but remains tied to specific tactic.

Despite these advancements, significant challenges remain, including dependency on predefined hypotheses and limitations in scope. These issues underscore the necessity for broader, standardized methodologies that integrate diverse detection techniques to achieve more comprehensive coverage.

Compromise assessment

CA is a large-scale comprehensive proactive defense method aimed at identifying and responding to cyber threats before they manifest. Since at least 201727, cybersecurity providers have been offering this service, with a growing number now including it in their portfolios of offered services. Despite its growing adoption in the cybersecurity market, there is a notable absence of academic research on this critical assessment. In addition to the lack of academic studies, the global understanding of the service is further complicated by commercial interests, as some providers tailor the service’s definition and methodology to align with their preferred solutions and products. This has led to inconsistencies in the definition of CA and significant variations in the methodologies applied.

Compromise assessment vs. threat hunting

CA and TH serve distinct yet complementary roles in cybersecurity, with CA covering a broader scope compared to the targeted approach of TH. CA operates as a project-like endeavor, providing a periodic comprehensive review of an organization’s data and security posture to answer the question: "Am I compromised?" It includes a thorough analysis to detect any signs of past or ongoing unauthorized access or breaches. In contrast, TH, which can be performed independently or as an integral component of a larger CA project, adopts a hypothesis-driven methodology. TH focuses on identifying whether an organization is compromised by specific threats, employing continuous or ad-hoc operations based on current intelligence and known attack methodologies. Table 1 compares and distinguishes between CA and TH.

Compromise assessment practices and market overview

We reviewed publicly available methodology descriptions from eleven providers and constructed a comparison matrix, summarized in Table 2. The matrix considered the stated purpose of the assessment, the timing of execution and suggested CA position in the cybersecurity program, the scope of coverage, the depth of data examined, the role of CTI in the assessment, the relationship with threat hunting, data prerequisites, analysis modes, transparency and reproducibility.

Despite its widespread availability in the cybersecurity market since at least 201727, CA suffers from inconsistent definitions and methodologies across vendors. Some providers treat CA as a proactive, intelligence-integrated service, while others consider it a reactive measure performed post-incident. Additionally, the integration of CTI and the transition to Incident Response28 varies significantly.

As shown in the matrix in Table 2, CA practices vary widely in scope, timing, methodology, and integration with Threat Hunting and Incident Response. Some approaches treat CA as reactive and narrow, others as proactive and intelligence-driven. Variations also exist in whether Threat Hunting is included29, how Cyber Threat Intelligence is used, and the degree of automation or human analysis applied.

The PROID framework: A structured approach to compromise assessment

This section presents the PROID CA framework, developed to serve the needs of medium to large IT environments. While several Threat Hunting frameworks such as TaHiTI18, PEAK22, BTH23, and POIROT24 have been published, there is currently no publicly available, detailed framework, guideline, or methodology for conducting CAs. Existing CA practices are defined by cybersecurity services vendors, such as Mandiant30, CrowdStrike31, Kaspersky32,33, Cisco34, and Group-IB35, each applying its own proprietary approach, which leads to significant inconsistency in scope, process, and integration with other security functions. By contrast, TH frameworks, while valuable, differ in scope and methodology; as they are hypothesis-driven and focus on answering specific investigative questions, often based on pre-existing intelligence. CA, however, is driven by the environment itself, including its assets, infrastructure, and operational context define the scope, and aims to provide complete coverage of that environment to identify both ongoing and historical compromises. The PROID framework addresses this gap by offering a standardized, transparent, and repeatable methodology that integrates multiple detection techniques, incorporates all layers of Cyber Threat Intelligence36, and defines a clear five-phase lifecycle from Preparation to Reporting. This structured approach ensures comprehensive coverage, adaptability across industries, and interoperability with Incident Response processes, enabling organizations to achieve consistent, high-fidelity compromise identification where no such standard previously existed.

Building on this identified gap, the following section presents the PROID framework in detail, outlining its design principles, operational phases, and integration points with existing cybersecurity processes to demonstrate how it delivers on these contributions in practice.

Applicability and audience

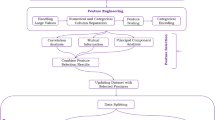

The PROID framework is designed for medium to large organizations operating regulated IT infrastructures. It supports proactive CAs as part of cybersecurity risk management37, applicable in various contexts such as regulatory compliance, infrastructure changes, or emerging threat intelligence. The framework serves CISOs, security managers, practitioners, researchers, and cybersecurity specialists. It offers strategic direction, operational guidance, technical processes, and investigative structure tailored to each role. Whether assessments are internally conducted or outsourced, PROID ensures a consistent approach to for detecting compromise and enhancing organizational resilience. Figure 1 displays an abstract structure of PROID Framework. The figure illustrates the five sequential phases—Preparation, Planning, Deployment, Analysis, and Reporting. Together, these phases highlight PROID’s emphasis on standardization, intelligence integration, and lifecycle repeatability, addressing existing gaps in Compromise Assessment (CA). The following are the five pillars of a compromise assessment.

Panel a (Preparation): Describes preparation phase activities including establishing the assessment context, identifying stakeholders, determining internal vs. external execution, gathering relevant documents, and aligning the assessment with the organization’s incident response processes and plans. The output is the Compromise Assessment (CA) initiation document, which defines objectives, roles, authorization, and communication schema.

Panel b (Planning): Describes activities for planning steps, including understanding the environment, reviewing threat intelligence, and determining required data, tools, and scope. The scope of the assessment is divided into phases, and the planning step produces an execution plan including prioritized phases based on criticality and threat relevance.

Panel c (Deployment): Shows the operational setup across each phase, covering permission handling, tool installation, configuration, and testing. It also includes the deployment of network sensors and continuous monitoring tools to support subsequent analysis. The deployment and analysis steps will be repeated with each phase of the scope of work.

Panel d (Analysis): Represents the data processing workflow: collection, parsing, enrichment, and structured analysis. It integrates three analytical techniques—signature-based detection, signature-less threat hunting, and comprehensive artifact analysis. The panel also depicts cross-phase threat correlation and behavioral analysis across multiple domains (e.g., DNS, file system, user behavior analytics activities38).

Panel e (Reporting): Highlights the final phase where documentation of progress, findings, scope coverage, and challenges is completed. This culminates in the generation of periodic update reports, an executive summary, and a comprehensive final report.

PROID phases

Preparation

PROID framework begins with a Preparation phase that generates a tightly scoped Compromise-Assessment Context Statement; this document forms the assessment’s purpose, its alignment with existing risk-governance cycles39, and the metrics against which its success will later be judged, thereby transforming the CA from a one-off activity into a managed and repeatable assessment40. This phase compels an early decision between an internal team, whose has the advantage of knowledge of local systems and lower data-exposure risk or an accredited external provider that has the advantages of independence, specialized tools41, and broader threat-intelligence. External providers can be mandated by sectoral regulators such as SAMA or PCI-DSS for high-stakes or politically sensitive engagements42,43,44. Key preparatory activities conducted include: (1) establishing the CA’s position within organizational strategy, regulatory requirements, and cybersecurity posture; (2) evaluating whether the assessment will be performed by the organization internal team or by an external provider; (3) conducting a detailed stakeholder analysis across executive, cybersecurity, technical, legal, and vendor domains; (4) collecting strategic and operational cyber threat intelligence to guide assessment planning; (5) gathering essential documents such as asset inventories, network diagrams, and recent security reports to inform scoping decisions; (6) integrating the CA with the Incident Response Plan to ensure smooth escalation and handoff procedures45; and (7) developing a communication and documentation schema to ensure clear, continuous stakeholder updates throughout the assessment lifecycle.

Planning

The Planning phase translates the contextual insight gained in Preparation into an evidence-driven blueprint for the forthcoming investigation. The assessment team begins by analyze the network diagrams, VLAN maps, asset inventories, domain and cloud configurations collected earlier, to identify and review the attack surface, mapping logical flows, security-control placement, and any security gaps. In parallel, it reviews strategic, operational, tactical and technical threat-intelligence feeds so that early knowledge of adversary intent, capability and TTPs can inform both analytic priorities and tool selection, Table 3 differentiate between the types of each of the threat intelligence. By the understanding of environment and threat landscape, analysts articulate threat hunting hypotheses drawn from intelligence clues, situational awareness of normal traffic patterns, and their accumulated domain expertise. Moreover, the team break the assessment into scope segments based on the organization unique characteristics, which can have privileged workstations, server clusters grouped by operating system and zone, network-traffic inspection points, and business-critical applications—each tagged with a risk-based criticality that governs order of execution. Phase-level prioritization is refined through the asset-inventory’s risk scores, past IR findings and penetration-test results, ensuring that high-value or historically targeted resources are examined first. Network-traffic analysis, whether full-packet capture or NetFlow should be included in every phase and culminates in a cross-cutting review once baseline behaviors are well understood. Finally, the team specifies the exact artefacts to be collected—system and security logs, user-activity records46, network traces, application telemetry—balances completeness against time, storage and connectivity constraints by defining triage levels for endpoints, inventories in-house data sources such as the Security Information and Event Management (SIEM), and selects collection, parsing, enrichment and visualization tools whose forensic soundness has been validated against anti-forensics threats. Table 4 shows common data to be selected for analysis in the CA. Moreover, the selected data will vary based on the level of investigation, if a host is suspected to be compromised, more data will be collected based on the levels of triaging shown in Fig. 2. It shows a per-phase, three-tiered approach —from mandatory lightweight artifacts to full disk and memory images—demonstrating scalable data collection that balances forensic depth with operational efficiency in Compromise Assessments. The result is a sequenced, resource-aware plan that aligns hypotheses, scope, data and tooling, setting unambiguous parameters for the subsequent execution and analysis stages of the CA. The following are the three tiers of digital evidence collection.

Panel a (Collection Level 1 – Initial Triage Collection Set): Represents the mandatory set of artifacts collected from every endpoint, focusing on high-value forensic indicators that are lightweight yet effective. These include but are not limited to binary execution records, persistence mechanisms, selective logs, shell history, and scan results from memory and disk. Each environment requires a different set of mandatory artifacts based on its threat landscape and endpoints’ type. Moreover, each phase of the assessment defines a tailored version of this initial set based on scope and intelligence inputs.

Panel b (Collection Level 2 – Advanced Triage Collection Set): Triggered selectively based on findings from the initial triage or specific threat intelligence. This level expands coverage to include larger set of system data including application logs, user activity traces, email artifacts, configuration files, and comprehensive file system metadata.

Panel c (Collection Level 3 – Full Disk & Memory Collection): Used in critical scenarios requiring maximum visibility, this level includes full disk and memory images. Due to the intensive nature and time consumption needed for this collection, it is reserved for cases where deep forensics is necessary47.

Deployment

Deploy phase focuses on setting up the necessary tools41 for the collection investigation. This phase is essential because it involves several activities to ensure the tools are ready, well-configured, and tested. Once approved, tools are installed and configured to fit the environment, ensuring compatibility and minimal disruption. To maintain assessment momentum, teams may deploy tools in phases—preparing one area while analyzing another. The phase concludes with testing and troubleshooting to verify operational reliability, ensuring readiness for accurate data acquisition in the subsequent analysis phase.

Analysis

The Analysis phase represents the core of the CA, where data collection, enrichment48, and detection activities are performed to identify evidence of current or past compromise. It is executed incrementally across defined phases of scope, ensuring completeness and focused depth of analysis. The process begins with data collection, where previously defined data is retrieved from each designated endpoint, server, or system. A tracking mechanism should be implemented to monitor collection status, identify gaps, and ensure complete coverage. Since these activities can interact with critical systems, it is important that this process occur without disrupting business operations, in coordination with IT and operations teams.

Once collected, raw data is parsed into structured, human-readable, preferably unified formats49. This involves normalizing diverse artifact types such as logs from different sources, registry entries, and file system data into a unified schema. Such normalization supports cross-source threat hunting and makes the subsequent analysis scalable across data types. Figure 3 shows the forensics artifacts parsing process. It shows the process of parsing raw system artifacts into analysis-ready data through a structured parsing and enrichment pipeline. The following are the forensic data pipeline: from raw artifacts to actionable intelligence.

Panel a (Collected System Artifacts): Represents the first step of the parsing process which is collecting various formats of raw data from endpoints during compromise assessments, including binary, EVTX, log files, databases, XML, and text artifacts.

Panel b (Artifacts Parsing): Describes the initial processing stage, where collected artifacts are matched to the appropriate parser from a predefined pool. Parsed data is then normalized using a common schema converter, resulting in a unified data structure that facilitates the analysis across different data sources.

Panel c (Data Enrichment): Shows how parsed data is enhanced with contextual metadata using public enrichment tools and local enrichment databases.

Panel d (Automated Detection and Visualization): Enriched data is forwarded to automatic detection engines for real-time alerting and to data presentation tools for visual analysis. These tools enable analysts to detect anomalies, track trends, and support decision-making with structured dashboards and reports.

Parsed data is then enriched with external intelligence and contextual metadata. Enrichment sources may include internal telemetry, threat intelligence platforms, or OSINT tools. Automated detection mechanisms are also triggered at this stage, leveraging rulesets such as YARA40, Sigma50, or Snort to scan for known malicious signatures or anomalous behavior patterns51.

The analytical process involves four distinct but complementary techniques. First, signature-based detection40,52,53,54 compares artifacts to known indicators of compromise using detection rules tailored to files, logs, memory, and network traffic. Second, signature-less threat hunting employs hypothesis-driven queries55 to validate adversary TTPs based on domain knowledge, threat intelligence, and situational awareness. Third, as illustrated in Fig. 4, the PROID methodology employs a human-led, iterative analysis process grounded in a zero-trust principle. Unlike traditional methods that search for known malicious patterns, this approach begins by assuming all system activity is untrusted. Analysts systematically identify and verify patterns of benign behavior. Once confirmed as legitimate, these patterns are excluded from the dataset. Any unverified activity undergoes contextual analysis to determine its legitimacy within the specific environment. This iterative process of eliminating known-good behavior progressively narrows the dataset to a core set of anomalous or suspicious artifacts, ensuring comprehensive attack surface coverage.

This method requires deep expertise in operating systems, networks, and the threat landscape. The final stage involves behavioral and anomaly analysis to identify deviations from established baselines over time. By focusing on the exclusion of only confirmed legitimate activity, this technique is highly effective at detecting stealthy and novel attacks that evade conventional signature-based detection.

Report

Documenting The Reporting phase concludes the assessment by documenting activities, findings, and key insights. It also serves as an ongoing communication channel throughout the process, supporting coordination with stakeholders and Incident Response teams when needed. Three types of reports are produced. The Status Update Report provides periodic updates on progress and challenges. The Final Report details findings, scope coverage, and recommendations to support long-term security improvement. The Executive Summary, either standalone or part of the final report, communicates key takeaways for senior leadership.

Experimental implementation

To validate the practical applicability and detection effectiveness of the PROID framework, a comprehensive implementation was carried out in a simulated enterprise environment designed to reflect real-world conditions. Against the simulated environment, a total of thirty-one MITRE-ATT&CK techniques15 were conducted to test PROID’s detection effectiveness and applicability compared to other methodologies.

Environment description

The environment included segmented zones typically found in modern organization, such as DMZ, internal server zone, and user endpoints, and PFSense56 firewalls for segregation. The lab hosted eleven systems: Domain Controller (Active Directory server) and one Exchange server (both on Windows Server 2019 Standard Evaluation), one MS SQL Server and one IIS Web Server (both on Windows Server 2022 Standard Evaluation), one Linux server running microservices via Docker, one ELK SIEM server (Elasticsearch 7.17.19)57, one Velociraptor Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR) server (v0.72-rc1)58, and four Windows workstations. Figure 5 presents a high-level network diagram of the simulated environment. The figure shows the network topology used to test PROID. The setup includes a Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) with an Exchange email server and IIS web server, a user zone with multiple workstations, and an internal network hosting servers such as Active Directory and SQL Server. Firewalls regulate communication between zones using allowed ports to simulate realistic network segmentation and access controls during assessment activities.

The entire simulation was hosted on VMware Workstation 17.5.1 (build 23,298,084). Endpoint telemetry employed Sysmon (Windows system monitoring tool for detailed event logging) using the SwiftOnSecurity59 configuration (sysmonconfig-export.xml). Signature scanning used Loki 0.51.0 with signature-base-2.0 YARA/Sigma rules, and Windows event-log hunting used Hayabusa 2.17.0 with the standard profile and default thresholds. Pattern mining of IIS logs employed LogMine 0.4.160 with -m 0.4. In LogMine, -m controls maximum distance (clustering granularity): lower values split more aggressively (finer clusters) and higher values merge more (coarser clusters). We selected 0.4 as a moderate setting to keep structurally similar HTTP requests together while preserving rare or anomalous sequences relevant to compromise indicators.

Simulated attacks

We executed 31 MITRE ATT&CK techniques15 spanning ten adversary tactics, such as Credential Access, Persistence, Lateral Movement, and Exfiltration, to provide a diverse challenge set for evaluation. Offensive actions were issued from controlled Windows 10 and Kali Linux 2024.161 hosts inside the lab. Atomic Red Team62 is an open-source library of reproducible cybersecurity attacks, aligned with the MITRE ATT&CK framework and was used to emulate several techniques in our simulated attacks. The simulated attacks were selected with a broad coverage across MITRE ATT&CK tactics and techniques, spanning Initial Access, Execution, Persistence, Privilege Escalation, Defense Evasion, Credential Access, Discovery, Lateral Movement, Command and Control, Collection, and Exfiltration. Table 5 lists all implemented techniques.

Assessment process

The attacks were implemented first in the lab to establish ground truth across thirty-one ATT&CK techniques. This ensured that subsequent evaluation of the assessment methods proceeded against a fixed and reproducible baseline. A single set of hypotheses was then prepared from threat intelligence and situational awareness, and used as a common input to all methods under study. In other words, PROID, PEAK, and TaHiTI all started from the same hypotheses and the same telemetry so that differences in outcome could be attributed to the methods rather than to differences in environment or setup. Hypothesis validation was carried out independently within each method’s own procedure. PEAK followed its baseline and model assisted hunts in addition to hypothesis driven queries. TaHiTI followed its intelligence driven cycle from initiation through refinement to execution. PROID was executed across its five phases, applying its four analytical methods: signature-based hunting (using YARA40, Sigma, Loki53, and Hayabusa54), hypothesis-based hunting, automated pattern recognition, and human-led artifact inspection (see Figs. 6 and 7). Detections were logged separately for each method to maintain clear attribution.

During the Comprehensive Artifacts Analysis phase, several key findings emerged:

-

Sysmon Log Analysis: A review of Sysmon event logs identified the execution of a binary named phant0m.exe, a tool used to disable Windows event logging63. Elastic visualization data confirmed that active logging ceased immediately after this binary was executed, dropping from 1,482 entries to zero.

-

Master File Table (MFT) Analysis: Evidence of timestomping was detected on the file logon.aspx. Timestomping is a technique that manipulates file timestamps to evade detection. A clear discrepancy was observed between the file’s $STANDARD_INFORMATION (Created0 × 10) timestamp (February 20, 2021) and its $FILE_NAME (Created0 × 30) timestamp (April 13, 2024). This inconsistency indicates deliberate manipulation to make the file appear legitimate and obscure its true creation time.

PROID’s data-driven design allows it to adapt to the specific assessment scope, rather than relying solely on pre-selected hypotheses or cyber threat intelligence. This flexibility proved critical in practice. For instance:

-

Web Server Analysis: Automated pattern recognition applied to IIS logs identified rare request patterns consistent with a web shell, guiding analysts to contextual confirmation (Fig. 8).

-

Defense Evasion: Artifact and timeline analysis uncovered the execution of a binary (phant0m.exe) that disabled Windows event logging, exposing a subsequent gap in the event flow.

-

Anti-Forensics: File system metadata analysis revealed creation time inconsistencies (timestomping) on the logon.aspx file.

A finding was credited as a confirmed detection either when an automated rule generated an alert with supporting artifacts, or when an analyst documented evidence corroborated by multiple independent sources.

During the Behavioral and Anomaly Analysis phase, we employed the tool LogMine for pattern detection. It flagged an anomaly related to a file named test2.aspx, which subsequent analysis confirmed to be a WebShell, a malicious file uploaded to a web server to provide unauthorized remote access. LogMine identified the unusual request for this file within a sequence of automated scans, highlighting it as suspicious. This detection not only indicated potential reconnaissance but also confirmed the deployment of test2.aspx for remote code execution. LogMine’s capacity to identify behavioral deviations was instrumental in uncovering this covert threat.

Results and observations

This section reports the outcomes of the implementation. The primary objective is breadth of technique coverage, since a CA objective is to identify any compromise exists anywhere in the environment in scope. Accordingly, time to alert is an operational monitoring concern; our emphasis here is on the completeness of technique detection.

Several outcomes relate to steps that are not specified in comparable methods yet materially affect success. First, a clear and documented scope is required for careful review and selection of systems, identities, and data sources that led to clear and measurable coverage. Second, preparation produced verifiable baselines of telemetry availability, ensuring that collection pipelines were functioning as intended and aligned with the assessment objectives. Third, scoping and preparation were aligned with cyber threat intelligence and mapped to the incident response processes so that findings could be correlated and acted upon. Comparable published methodologies focus mainly on the analysis phase and do not describe these lifecycle steps in a way that allows direct comparison, so the remainder of this section concentrates on analysis outcomes.

In our implementation, PROID detected all thirty-one MITRE ATT&CK techniques exercised in the simulated environment, covering ten tactics across host, network, and application layers. Achieving this breadth required the coordinated use of diverse analytical approaches and tools, including signature-based detection, behavior driven hunting, pattern mining of application logs, and analyst led review of artifacts.

Signature-based detection was the most straightforward to implement and the fastest to alert, as expected when suitable rulesets were available and updated. With maintained Sigma and YARA content, web shells, access to LSASS memory, and extraction of NTDS data were promptly identified. Attacks detected by this pathway were also recoverable through at least one other PROID pathway, which indicates that signatures remain an efficient first line when coverage exists but are not the sole determinant of success. Signature-less threat hunting contributed to detections where fixed indicators were insufficient. Using the shared hypotheses as priors, and analyzing how each hypothesis could be validated, we issued targeted queries and performed temporal correlation across Windows Security, Sysmon, IIS, and directory telemetry to surface activity consistent with adversary tradecraft. This approach revealed remote command execution via WMI, where command prompt executed under wmiprvse.exe, a malicious scheduled task launching a binary from a public user directory, malicious service creations, and unauthorized Group Policy changes that granted elevated local privileges. These findings relied on the structure and sequence of actions rather than on a single rule, which is more dynamic in detection. Behavioral baselining and pattern mining addressed activity that blended into routine traffic. Mining of IIS logs with LogMine at m 0.4 exposed rare request shapes, parameter patterns, and response sequences that were consistent with a web shell and that had not triggered a signature. Baseline comparisons of authentication and process creation also highlighted outliers that warranted review. This pathway proved particularly useful when primary telemetry was noisy. Comprehensive human led analysis provided the final layer of assurance and was the most time-consuming stage. Analysts iteratively reviewed timelines and correlated artifacts across file system metadata, Windows event channels, IIS logs, and Velociraptor collections. The workflow emphasized careful selection of high value artifacts, verification of provenance, and the exclusion of benign patterns after verification. This process surfaced timestomping by exposing inconsistencies among file system timestamps, including divergence between NTFS Master File Table standard information and file name attributes and misalignment with surrounding log and journal records. It also confirmed execution of a binary that disabled Windows event logging by aligning a sudden drop in event volume with the corresponding process lineage and related traces on the host.

Under identical hypotheses and telemetry, PROID detected all thirty-one techniques. PEAK and TaHiTI did not consistently surface Scheduled Task T1053.005, Disable Windows Event Logging T1562.002, and Timestomp T1070.006. PEAK executed baseline and model assisted hunts with predefined queries against the same SIEM data; its detections were driven by deviations from behavioral baselines and by rule matched artifacts. In these runs, PEAK produced alerts for web shells, access to LSASS memory, and NTDS extraction, but it did not flag the logging suppression when primary events were absent, and it did not persistently identify timestomped files without manual correlation. TaHiTI followed an intelligence driven cycle in which hypotheses derived from CTI were prioritized and investigated through targeted searches; it reproduced detections where the hypothesis explicitly mapped to the technique and the expected artifacts were present, but it missed techniques that fell outside the initial hypotheses or that depended on historical artifacts rather than active indicators, including T1053.005 and T1070.006. The detailed detection comparison across methodologies is presented in Table 6. While supplementary frameworks and methodologies such as BTH and POIROT provide useful approaches, their methodologies and scope are narrower and not directly comparable to PROID’s comprehensive lifecycle.

Several practical limitations were observed during the assessment. The approach is time consuming; in our evaluation, PROID required substantially more analyst hours than the methods to which it was compared, with the human led analysis alone exceeding twelve working hours in the simulated environment. In larger organizations, the same assessment could require weeks of analysis to accurately cover a broader scope. Moreover, a key determinant of execution quality was the experience of personnel able to establish and interpret technical baselines across the systems in scope. PROID required experienced incident response and digital forensics analysts for effective implementation, especially for the human led analysis, which depends largely on the analyst’s technical knowledge. Another critical prerequisite for the success of PROID is proper assets management and visibility to ensure proper coverage.

Conclusion

The expanding digital landscape exposes organizations to increasingly sophisticated cyber threats that exploit vulnerabilities across diverse platforms. In this environment, proactive cyber defense has become an essential component of modern cybersecurity programs. This approach entails the continuous assessment of potential risks, the gathering and analysis of CTI, and the implementation of measures to identify and neutralize threats before they can cause significant damage.

While incident response is inherently reactive—initiating only after a breach is detected—CA and TH introduce a critical proactive element by actively searching for IOCs before they escalate into full-scale incidents. Although numerous frameworks and academic studies address threat hunting, a significant gap remains in the standardization of CA. The absence of widely accepted frameworks or published studies has resulted in inconsistent implementations, unclear scopes and objectives, and confusion regarding the distinction between CA and TH. This paper introduces a novel CA framework designed to address this gap by providing a detailed, standardized approach for conducting periodic and comprehensive assessments to proactively identify compromises.

The literature review examined TH as a proactive strategy, analyzing methodologies such as TaHiTI—an intelligence-driven, hypothesis-based cycle that progresses from hypothesis initiation to refinement through data analysis—and the PEAK framework, which categorizes hunting into hypothesis-driven, baseline, and model-assisted methods. The review emphasized the integral role of CTI, which provides strategic, operational, tactical, and technical insights to guide prioritization and enhance detection fidelity. It also noted that an overreliance on predefined hypotheses may limit the detection of novel threats.

Furthermore, the review analyzed current CA practices, highlighting a critical lack of standardized frameworks or academic studies. This has led to inconsistencies in the definition, methodology, and application of CA. The review clearly distinguishes CA from threat hunting: CA is a broader, artifact- and data-based evaluation designed to answer the question, “Am I compromised?”, whereas threat hunting is typically a more focused, hypothesis-driven search for specific threats. An examination of leading providers (e.g., Mandiant, CrowdStrike, Kaspersky) revealed significant methodological variations and gaps, including limited CTI integration and insufficient attention to misconfigurations, insider threats, and historical breaches. Unlike continuous threat hunting frameworks, the proposed CA framework is structured for periodic, comprehensive evaluations to detect past and present compromises across an organization’s entire system landscape.

The framework is organized into five distinct phases: Preparation, Planning, Deployment, Analysis, and Reporting. The Preparation phase establishes objectives, scope, and stakeholder alignment while integrating the assessment into the broader cybersecurity program. The Planning phase involves environmental analysis, critical asset prioritization, hypothesis generation, and tool selection. Deployment focuses on the implementation and validation of data collection tools across the defined scope. Analysis employs a multi-layered approach, integrating signature-based and signature-less hunting, automated pattern recognition, and human-led analysis to identify IOCs and malicious activity. Finally, Reporting consolidates findings and provides actionable recommendations for remediation.

The framework was validated in a simulated enterprise environment where thirty-one MITRE ATT&CK techniques were executed across ten tactics. The assessment successfully detected each technique using a combination of four analytical methods: signature-based detection, signature-less hunting, automated pattern recognition, and human-led analysis. The integration of these methods, coupled with the comprehensive scope characteristic of CA, resulted in higher detection rates than those achieved by established threat hunting methodologies like TaHiTI and PEAK. CTI was utilized to contextualize the assessment, guiding scope definition, data collection strategies, and hypothesis generation. Segmenting the analysis by endpoint groups with similar characteristics improved precision by enabling focused investigations and streamlined anomaly detection. High-risk assets—including sensitive servers, privileged workstations, and external-facing endpoints—were prioritized for in-depth analysis.

The effectiveness of the framework is influenced by analyst expertise, as human-led analysis requires the ability to establish and interpret technical baselines across diverse systems. Outcomes improve significantly with experienced incident response and digital forensics personnel. The process can be time-consuming, particularly in large environments; thus, it is recommended that assessments be carefully scoped and executed in phases aligned with network zones or asset classes. Given its strength in breadth of detection rather than speed, the framework is ideally suited as a periodic assurance activity—conducted, for example, once or twice annually—to complement daily monitoring optimized for rapid alerting.

In conclusion, the proposed CA framework addresses a critical gap in cybersecurity practice by providing a standardized methodology for proactively detecting, mitigating, and preventing intrusions. It complements existing monitoring and incident response capabilities by prioritizing comprehensive detection coverage over speed, offering organizations a practical and reproducible method to enhance their overall security resilience.

Future work and recommendations

Future work should prioritize deploying the framework in real-world environments to validate its effectiveness, address practical challenges, and assess its adaptability. PROID is designed for implementation in medium and large organizations seeking to enhance their proactive defense postures.

To improve efficiency and scalability, the automation of key components—such as data collection and analysis—should be explored. The development of custom tools could significantly enhance these processes. Furthermore, integrating artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML)64 could substantially bolster the framework’s capabilities, particularly in behavioral analysis and anomaly detection.

PROID can also be integrated within a Zero Trust architecture by leveraging identity groups, device posture assessments, and micro-segmentation maps to scope and phase CAs. Policy and access logs can enrich threat hypotheses and baseline definitions. In return, findings from PROID can inform policy engines to update risk scores, terminate sessions, isolate devices, or require step-up authentication. In practice, PROID should be scheduled as a periodic assurance activity and triggered ad hoc in response to elevated Zero Trust risk indicators.

Collaboration with industry and academic partners will be essential to foster knowledge sharing, support joint research, and develop open-source tools that advance the framework. Additionally, PROID must continuously evolve in response to emerging threats by incorporating current Cyber Threat Intelligence and adapting to adversarial tactics. Alignment with compliance requirements and industry standards will ensure seamless integration into organizational cybersecurity programs, sustaining its relevance as a cutting-edge tool for proactive defense.

A logical extension for PROID involves incorporating machine learning to enhance analytical capabilities. Unsupervised and semi-supervised models can learn baselines for hosts and applications, surfacing rare event sequences across Windows Security, Sysmon, IIS, and directory telemetry. Graph-based methods applied to process, file, and network relationships can highlight suspicious activities that are difficult to capture with rule-based detection. Temporal models can identify subtle long-term behavioral changes indicative of defense evasion, while analyst feedback can be integrated through active learning loops to refine true positives and reduce recurrent false positives. Large language models can also assist by normalizing log data, suggesting detection rules, and aiding triage through schema mapping and event cluster explanation. This integration aims to reduce PROID’s time consumption and lessen its dependence on extensive analyst experience.

Data availability

The dataset generated and analyzed during the current study are available in the Figshare repository, [https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28873358] (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28873358).

References

-Scott, J. Signature-Based Malware Detection is Dead. Institute for Critical Infrastructure Technology. (2017).

-MITRE. (2022). Groups | MITRE ATT&CKTM. Attack.mitre.org. https://attack.mitre.org/groups/.

Martínez, J. & Durán, J. M. Software supply chain attacks, a threat to global cybersecurity: SolarWinds’ case study. Int. J. Safety Sec. Eng. 11(5), 537–545 (2021).

-Thompson, B. (2023, August 8). UK Electoral Commission hacked: Voter data exposed over a year later. The Register. https://www.theregister.com/2023/08/08/uk_electoral_commission_hacked_voter/.

-Sabbagh, D. (2023, August 8). UK Electoral Commission registers targeted by hostile hackers. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2023/aug/08/uk-electoral-commission-registers-targeted-by-hostile-hackers.

-Symantec Threat Hunter Team. (2022, February 3). Antlion: Chinese APT uses custom backdoor to target financial institutions in Taiwan. Symantec Enterprise Blogs. https://www.security.com/threat-intelligence/china-apt-antlion-taiwan-financial-attacks.

-Cisco Talos. (2019, April 17). Sea Turtle: DNS hijacking abuses trust in core internet services. Talos Intelligence. https://blog.talosintelligence.com/seaturtle/#:~:text=Cisco%20Talos%20has%20discovered%20a,actor%20that%20seeks%20to%20obtain.

-Ponemon Institute. Cost of a data breach report 2023. IBM Security. (2023).

-U.S.-Saudi Business Council. (2020, January). Saudi Arabia’s emergence in cyber technology. Retrieved November 11, 2023, from https://ussaudi.org/saudi-arabias-emergence-in-cyber-technology/.

-Blumira. (2023). State of detection and response. Retrieved November 11, 2023, from https://www.blumira.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/State-of-Detection-and-Response-3.pdf.

Agrafiotis, I., Nurse, J. R., Goldsmith, M., Creese, S. & Upton, D. A taxonomy of cyber-harms: Defining the impacts of cyber-attacks and understanding how they propagate. J. Cybersecurity 4(1), tyy006 (2018).

Sharif, M. H. U. & Mohammed, M. A. A literature review of financial losses statistics for cyber security and future trend. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 15(1), 138–156 (2022).

-Radoglou-Grammatikis, P., Liatifis, A., Grigoriou, E., Saoulidis, T., Sarigiannidis, A., Lagkas, T. Sarigiannidis, P. Trusty: A solution for threat hunting using data analysis in critical infrastructures. In 2021 IEEE International Conference on Cyber Security and Resilience (CSR) IEEE. 485–490 (2021).

-Aarness, A. (2023, August 29). What are compromise assessments? - crowdstrike. crowdstrike.com. https://www.crowdstrike.com/cybersecurity-101/compromise-assessments/.

-MITRE. (n.d.). MITRE ATT&CK® for Enterprise. Retrieved August 27, 2024, from https://attack.mitre.org/matrices/enterprise.

Jadidi, Z. & Lu, Y. A threat hunting framework for industrial control systems. IEEE Access 9, 164118–164130 (2021).

-IBM Security. Cost of a Data Breach Report 2023. IBM Corporation. (2023).

-Van Os, R., Bakker, M., Bouman, R., Docters van Leeuwen, M., van der Kraan, M., & Mentges, W. (2018). TaHiTI: A threat hunting methodology. Dutch Payments Association. Retrieved November 10, 2023, from https://www.betaalvereniging.nl/wp-content/uploads/TaHiTI-Threat-Hunting-Methodology-whitepaper.pdf.

Bhardwaj, A. & Goundar, S. A framework for effective threat hunting. Netw. Secur. 2019(6), 15–19 (2019).

-Gunter, D., & Seitz, M. A practical model for conducting cyber threat hunting. Sans. org. (2018).

-Lee, R. M., & Bianco, D. Generating hypotheses for successful threat hunting. SANS Institute InfoSec Reading Room. (2016).

-Splunk Inc. (2021). PEAK Threat Hunting Framework. Splunk. Retrieved November 10, 2023, https://www.splunk.com/en_us/form/peak-threat-hunting-framework.html.

Bhardwaj, A. et al. BTH: Behavior-Based structured threat hunting framework to analyze and detect advanced adversaries. Electronics 11(19), 2992 (2022).

-Milajerdi, S. M., Eshete, B., Gjomemo, R. Venkatakrishnan, V. N. Poirot: Aligning attack behavior with kernel audit records for cyber threat hunting. In Proceedings of the 2019 ACM SIGSAC conference on computer and communications security 1795–1812 (2019).

Mahboubi, A. et al. Evolving techniques in cyber threat hunting: A systematic review. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 232, 104004 (2024).

Bhardwaj, A., Bharany, S., Almogren, A., Rehman, A. U. & Hamam, H. Proactive threat hunting to detect persistent behaviour-based advanced adversaries. Egypt. Inform. J. 27, 100510 (2024).

-SECUINFRA. (n.d.). Compromise Assessment. Retrieved March 7, 2024, from https://www.secuinfra.com/en/incident-management/compromise-assessment/.

-Rapid7. (n.d.). Compromise Assessment. Retrieved March 7, 2024, from https://www.rapid7.com/globalassets/_pdfs/product-and-service-briefs/rapid7-service-brief-compromise-assessment.pdf.

-Booz Allen Hamilton. (n.d.). Compromise Assessment. Retrieved March 7, 2024, from https://www.boozallen.com/c/solution/compromise-assessment.html.

-Mandiant - part of Google Cloud. (n.d.). Compromise Assessment. Retrieved March 7, 2024, from https://services.google.com/fh/files/misc/ds-compromise-assessment-en.pdf.

-CrowdStrike. (2023). CrowdStrike 2023 threat hunting report. Retrieved November 11, 2023, from https://go.crowdstrike.com/rs/281-OBQ-266/images/report-crowdstrike-2023-threat-hunting-report.pdf.

-Kaspersky. (n.d.). Enterprise security: Compromise assessment. Retrieved November 11, 2023, from https://www.kaspersky.com/enterprise-security/compromise-assessment.

-Kaspersky. (2023, November 17). Understanding Compromise Assessment. Retrieved March 7, 2024, from https://www.kaspersky.com/blog/understanding-compromise-assessment/49671/.

-Cisco. (2018, December 3). Compromise Assessment vs. Threat Hunting. Retrieved March 7, 2024, from https://blogs.cisco.com/security/compromise-assessment-vs-threat-hunting.

-Group-IB. (n.d.). Compromise assessment services. Retrieved November 11, 2023, from https://www.group-ib.com/services/compromise-assessment/.

Sun, N. et al. Cyber threat intelligence mining for proactive cybersecurity defense: A survey and new perspectives. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 25, 1748–1774 (2023).

Marotta, A. & McShane, M. Integrating a proactive technique into a holistic cyber risk management approach. Risk Manag. Ins. Rev. 21(3), 435–452 (2018).

-Rengarajan, R., & Babu, S. Anomaly Detection using User Entity Behavior Analytics and Data Visualization. In 2021 8th International Conference on Computing for Sustainable Global Development (INDIACom) IEEE. 842–847 (2021).

Gale, M., Bongiovanni, I. & Slapnicar, S. Governing cybersecurity from the boardroom: Challenges, drivers, and ways ahead. Comput. Secur. 121, 102840 (2022).

-Naik, N., Jenkins, P., Cooke, R., Gillett, J. Jin, Y. Evaluating automatically generated YARA rules and enhancing their effectiveness. In 2020 IEEE Symposium Series on Computational Intelligence (SSCI) IEEE. 1146–1153 (2020).

Salih, K. M. M. & Dabagh, N. B. I. Digital forensic tools: A literature review. J. Educ. Sci. 32(1), 109–124 (2023).

-Saudi Arabian Monetary Authority (SAMA). (2019, May). SAMA - Financial entities ethical red-teaming framework. Retrieved March 2, 2024, from https://uploads-ssl.webflow.com/59d28ad983887e000196f803/5fecc27919c71c17d5a10851_Financial%20Entities%20Ethical%20Red%20Teaming%20Framework.pdf.

-Saudi Arabian Monetary Authority (SAMA). (2019, December). Outsourcing rules - Revised v2 final draft. Retrieved March 1, 2024, from https://www.sama.gov.sa/en-US/RulesInstructions/FinanceRules/Outsourcing%20Rules%20-%20Revised%20v2%20Final%20Draft-Dec-2019.pdf.

-National Cybersecurity Authority. (2018). Essential cybersecurity controls. Retrieved March 3, 2024, from https://nca.gov.sa/ecc-en.pdf.

-Stevens, R., Votipka, D., Dykstra, J., Tomlinson, F., Quartararo, E., Ahern, C. Mazurek, M. L. How ready is your ready? assessing the usability of incident response playbook frameworks. In Proceedings of the 2022 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems 1–18 (2022).

-Shashanka, M., Shen, M. Y., & Wang, J. User and entity behavior analytics for enterprise security. In 2016 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data) IEEE. 1867–1874 (2016).

Breitinger, F. et al. DFRWS EU 10-year review and future directions in digital forensic research. Forensic Sci. Int.: Digital Invest. 48, 301685 (2024).

-Lee, H. W. Analysis of Digital Forensic Artifacts Data Enrichment Mechanism for Cyber Threat Intelligence. In Proceedings of the 2023 12th International Conference on Software and Computer Applications 192–199 (2023).

-Elastic. (2019, February 14). Introducing the Elastic Common Schema. Elastic Blog. Retrieved March 14, 2024, from https://www.elastic.co/blog/introducing-the-elastic-common-schema.

-SigmaHQ. (n.d.). Sigma. Retrieved March 14, 2024, from https://github.com/SigmaHQ/sigma.

-Siddiqui, M. A., Stokes, J. W., Seifert, C., Argyle, E., McCann, R., Neil, J. Carroll, J. Detecting cyber attacks using anomaly detection with explanations and expert feedback. In ICASSP 2019–2019 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP) IEEE. 2872–2876 (2019).

Kwon, H. Y., Kim, T. & Lee, M. K. Advanced intrusion detection combining signature-based and behavior-based detection methods. Electronics 11(6), 867 (2022).

-Roth, F. (n.d.). Loki: Simple IOC and YARA Scanner. Retrieved August 27, 2024, from https://github.com/Neo23x0/Loki.

-Yamato, K. (n.d.). Hayabusa: Fast event log hunting and intrusion detection. Retrieved August 27, 2024, from https://github.com/Yamato-Security/hayabusa.

-Fuchs, M. Lemon, J. Sans 2019 threat hunting survey: The differing needs of new and experienced hunters. SANS Institute Information Reading Room. (2019).

-Netgate. (n.d.). pfSense: The open source firewall and router. Retrieved January 18, 2024, from https://www.pfsense.org.

-Elastic. (n.d.). The ELK Stack: Elasticsearch, Logstash, and Kibana. Retrieved January 18, 2024, from https://www.elastic.co/what-is/elk-stack.

-Velociraptor. (n.d.). Velociraptor documentation. Retrieved August 27, 2024, from https://docs.velociraptor.app/.

-SwiftOnSecurity. (n.d.). sysmon-config: A Sysmon configuration file template [Configuration file]. GitHub. Retrieved August 20, 2025, from https://github.com/SwiftOnSecurity/sysmon-config/blob/master/sysmonconfig-export.xml.

-Hamooni, H., Debnath, B., Xu, J., Zhang, H., Jiang, G., & Mueen, A. (2016). LogMine: Fast pattern recognition for log analytics. In Proceedings of the 25th ACM International on Conference on Information and Knowledge Management 1573–1582 ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/2983323.2983358

-Kali Linux. (2024, January 23). Kali Linux 2024.1 release notes. Offensive Security. Retrieved August 25, 2025, from https://www.kali.org/blog/kali-linux-2024-1-release/.

-Red Canary. (n.d.). Atomic Red Team: A library of tests mapped to the MITRE ATT&CK framework [Code repository]. GitHub. Retrieved August 25, 2025, from https://github.com/redcanaryco/atomic-red-team.

-hlldz. (n.d.). Phant0m: Windows Event Log Killer. Retrieved August 27, 2024, from https://github.com/hlldz/Phant0m.

Lozano, M. A., Llopis, I. P. & Domingo, M. E. Threat hunting architecture using a machine learning approach for critical infrastructures protection. Big Data Cognitive Comput. 7(2), 65 (2023).

-BlackBerry. (n.d.). Compromise Assessment. Retrieved March 7, 2024, from https://www.blackberry.com/us/en/services/compromise-assessment.

-BlackBerry. (2020). Compromise Assessment. Retrieved March 7, 2024, from https://www.blackberry.com/us/en/pdfviewer?file=/content/dam/blackberry-com/asset/enterprise/pdf/ds-spark-compromise-assessment.pdf.

-Cisco. (2022). Compromise Assessment. Retrieved March 7, 2024, from https://talosintelligence.com/resources/191.

-Cobalt. (2023, March 6). Compromise Assessment: A Comprehensive Guide. Retrieved March 7, 2024, from https://www.cobalt.io/blog/compromise-assessment-a-comprehensive-guide.

-KPMG. (2019). Compromise Assessment Cyber Defense Services. Retrieved March 7, 2024, from https://assets.kpmg.com/content/dam/kpmg/ch/pdf/compromise-assessment-factsheet.pdf.

-Palo Alto Networks. (n.d.). Unit 42 Managed Threat Hunting. Retrieved March 7, 2024, from https://www.paloaltonetworks.com/apps/pan/public/downloadResource?pagePath=/content/pan/en_US/resources/datasheets/unit42-ds-managed-threat-hunting.

-Palo Alto Networks. (n.d.). Compromise Assessment. Retrieved March 7, 2024, from https://www.paloaltonetworks.com/apps/pan/public/downloadResource?pagePath=/content/pan/en_US/resources/datasheets/compromise-assessment.

Acknowledgements

This paper is derived from a research grant funded by the Research, Development, and Innovation Authority (RDIA)—Kingdom of Saudi Arabia—with grant number (13325-psu-2023-PSNU-R-3-1-EF). Also, the authors would like to thank Prince Sultan University for their support. Additionally, the authors would like to acknowledge the support of Prince Sultan University for paying the Article Processing Charges (APC) of this publication.

Funding

Prince Sultan University

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.A.A. wrote the entire manuscript. F.A., A.A.A. (Ahmed), and N.A. reviewed the manuscript and provided corrections and suggestions for several sections.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alkhalaf, A.A., Alruwaili, F.F., El-Latif, A.A.A. et al. Proactive identification of cybersecurity compromises via the PROID compromise assessment framework. Sci Rep 15, 39102 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24936-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24936-2