Abstract

Efficient data utilization and strong privacy protection are major challenges in Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITS), particularly in complex environments with highly distributed Intelligent Connected Vehicles (ICVs). Conventional machine learning methods struggle to capture complex spatiotemporal dependencies while maintaining data privacy and locality. To overcome these limitations, we propose FedGDAN, a Federated Graph Diffusion Attention Network that combines graph neural networks (GNNs) with federated learning (FL) to enable collaborative traffic flow prediction without sharing raw data. FedGDAN models global spatiotemporal correlations across road networks and introduces an adaptive local aggregation mechanism to address non-independent and identically data distributions, thereby improving robustness and accuracy. Experiments on real-world datasets show that FedGDAN consistently outperforms state-of-the-art centralized and federated baselines, achieving 3%–10% gains in Mean Absolute Error.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, Intelligent Transportation Systems have garnered widespread attention globally. Particularly amid significant breakthroughs in artificial intelligence, deep learning methods have proven effective in enhancing traffic management1. Traffic flow prediction (TFP) constitutes a critical component of ITS, as traffic congestion severely impacts urban transportation networks. Accurate prediction of road traffic flow thus enables authorities to optimize vehicle routing and improve operational efficiency. In ITS, traffic data can be collected via various sensors—such as intelligent connected vehicles, cameras, and roadside sensors—providing real-time traffic flow information2.

Data serves as a critical driving force for advancing Intelligent Transportation Systems. The data generated by ICVs encompasses diverse and highly sensitive categories, including driver biometrics and health data, vehicle trajectory and location information, vehicle identity and user identification3. In traditional centralized Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITS), after data collection, vehicles operate in a distributed manner, transmitting data directly to roadside units (RSUs) or a central cloud for training. This approach is, in principle, complex and not well-suited to adapting to environmental changes within a short time frame. Moreover, it necessitates the transmission of large volumes of image data, resulting in substantial bandwidth consumption4. Additionally, the direct transmission of raw data makes the system more vulnerable to external attacks.

Federated learning is a distributed machine learning paradigm that enables collaborative model training while keeping data locally on each device5. It has been widely applied in Intelligent Transportation Systems, with its basic architecture illustrated in Fig. 1. Crucially, FL facilitates cross-database collaboration among transportation agencies and enterprises, integrating fragmented data resources while breaking down information silos6. Furthermore, regulatory frameworks such as the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and China’s Personal Information Protection Law impose stringent requirements on data processing7, making privacy-preserving approaches like FL increasingly essential.

Meanwhile, compared with other tasks in intelligent transportation systems, traffic flow prediction exhibits stronger temporal and spatial dependencies8. This is specifically manifested in the fact that prediction results are not only affected by the road network topology at the current location but also dynamically change with time periods, dates.Traditional time series models (e.g., ARIMA) or grid convolution methods struggle to effectively model the complex spatiotemporal dependencies under the non-Euclidean structure of road networks. However, unlike these traditional methods that fail to handle non-Euclidean road network structures, methods based on graph neural networks9 have shown outstanding performance in traffic flow prediction, thanks to their inherent ability to model complex spatial relationships in irregular network topologies.

In practical urban traffic scenarios, traffic flow data from different road segments or nodes often exhibit significant non-independent and identically distributed (Non-IID) characteristics. Such differences are reflected not only in the periodic temporal variations of traffic flow but also in the distribution disparities across different regions arising from their functional positioning and road structures10,11,12. For instance, traffic flow is highly concentrated on major roads, and there exists a correlation between the traffic flow of road segments and nearby buildings such as hospitals and schools. Therefore, the assumption that traffic flow data is independent and identically distributed is invalid in most cases.Within the federated learning framework, directly adopting a unified global model often struggles to accommodate the heterogeneous needs of various nodes, leading to a decline in prediction performance. To address this challenge, this paper introduces a personalized federated learning approach. This method can share global knowledge while adapting to the local data distribution of different nodes, thereby better capturing the diversity and spatiotemporal variability of traffic data and improving the accuracy of traffic flow prediction.

To efficiently accomplish the task of traffic flow forecasting while protecting the privacy of data in intelligent connected vehicle systems, we propose a framework called Federated Graph Diffusion Attention Network (FedGDAN). This framework integrates a graph neural network–based traffic flow prediction model into a federated learning setting. Specifically, we introduce a Graph Diffusion Attention Network (GDAN) as the local prediction model on each client, and incorporate a local adaptive aggregation mechanism within the federated learning process. In addition, differential privacy techniques are applied to protect the parameters uploaded by clients.

FedGDAN achieves distributed and efficient traffic flow prediction through a dual-layer design that combines federated learning with graph diffusion attention networks. The local adaptive aggregation mechanism allows each client to dynamically adjust the balance between its local model and the global model, thereby alleviating the negative effects caused by differences in network topologies across clients. Unlike approaches such as13, where clients must upload subgraphs for matrix alignment, our method enables clients to implicitly share their local topological information simply by transmitting model parameters. The global topological knowledge is then captured through server-side aggregation. Furthermore, by applying differential privacy to the uploaded parameters, the framework ensures that even if these parameters are intercepted during transmission or aggregation, adversaries cannot infer the clients’ original traffic data or sensitive information. This design strengthens the privacy protection barrier at the level of model parameters.

The main contributions are summarized as follows:

-

To address the problem of traffic flow prediction, this paper proposes FedGDAN, a federated learning framework that protects topological information. The framework integrates a prediction model based on a graph diffusion attention network and enables clients to share spatio-temporal information by uploading model parameters, without exchanging raw data or subgraph topologies. In this way, FedGDAN provides privacy-preserving traffic flow forecasting.

-

In the proposed federated learning (FL) framework, we introduce an Adaptive Local Aggregation (ALA) method to mitigate the Non-IID data problem across clients caused by differing traffic scenarios, thereby improving the accuracy of collaborative distributed prediction. On top of this, we further incorporate differential privacy techniques to ensure stronger protection of client data security.

-

A series of comprehensive case studies are conducted on a real-world traffic dataset to demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed FedGDAN framework.

Related work

GNN-based approaches for traffic flow prediction

In traffic flow prediction tasks, capturing spatial correlations within the data proves highly beneficial for forecasting temporal sequences14. While some studies15,16 employ Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) to model spatial dependencies in transportation networks, CNNs excel primarily at extracting local spatial features from regular grid structures. In contrast, Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) are better suited for capturing spatial dependencies within complex, non-grid topologies inherent to transportation networks17.

Therefore, to effectively model the spatiotemporal relationships in traffic networks, researchers have integrated GNNs with temporal prediction models. For example, the Temporal Graph Convolutional Network18(T-GCN) combines Graph Convolutional Networks with Gated Recurrent Units (GRU); DCRNN? integrates the diffusion convolutional network with recurrent neural networks; and AGCRN19 introduces two novel adaptive modules to enhance the capability of GCNs, further combining them with recurrent neural networks to model the spatial and temporal correlations in traffic sequences.

Although some studies have combined CNNs and GNNs for traffic data modeling20,21, these approaches tend to focus on local feature modeling. As a result, they often achieve excellent performance in short-term forecasting but may be less effective for long-term predictions. Additionally, attention mechanisms have been widely applied in traffic flow prediction. For instance, GMAN22 effectively leverages the attention mechanism to capture comprehensive spatiotemporal correlations among traffic features, and employs transform attention to mitigate discrepancies between historical and future information. The Attention-based Spatio-Temporal Graph Convolutional Network23 (ASTGCN) integrates GCNs for local spatial feature extraction with attention mechanisms to capture global spatial features. The Spatio-Temporal Graph Attention Network24 (ST-GAT) introduces a novel graph structure called the Individual Spatio-Temporal Graph (IST-graph) to facilitate accurate traffic speed prediction through IST-graph-based spatiotemporal point embeddings.

Federated learning for traffic flow prediction

Traffic flow prediction typically requires a substantial volume of traffic data, which may originate from multiple sources. As data scales increase, traditional centralized computing paradigms struggle to efficiently handle such tasks. As a distributed machine learning paradigm, federated learning offers novel solutions for traffic flow prediction. Liu et al.25. proposed a federated gated recurrent unit neural network (FedGRU) for traffic prediction, highlighting the limitations of centralized machine learning in privacy preservation and demonstrating the advantages of FL in distributed privacy-aware traffic prediction. Qi et al. Zeng et al.26. developed a multi-task FL framework incorporating hierarchical clustering to partition traffic data from individual stations into distinct clusters. This approach optimizes prediction models through collaborative training across distributed stations using localized data clusters. Zhang et al.13. integrated an attention-based spatial-temporal graph neural network (ASTGNN) model into a federated learning framework and proposed a differential privacy-based adjacency matrix protection method to safeguard topological information.Xia et al.27. employed the Louvain algorithm to partition the road network topology and adopted a two-layer Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) to capture spatial topological features of traffic data for short-term traffic flow prediction.Shen et al.28. proposed a customized spatio-temporal Transformer network to replace conventional Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) for localized personalized learning among participants, which demonstrates superior capability in capturing spatio-temporal characteristics of vehicular data. Liu et al.29. pioneered the adoption of an online learning paradigm within the Federated Learning (FL) framework for traffic flow prediction, proposing a novel forecasting methodology termed Online Spatio-Temporal Correlation-based Federated Learning (FedOSTC). This innovative approach is specifically designed to maintain superior predictive performance even under conditions of traffic flow volatility.

Our work distinctively addresses the dual challenges of topological privacy preservation and statistical heterogeneity in federated Learning. Unlike prior approaches that either focus solely on privacy13,25 or assume IID data distributions26,27,28, FedGDAN integrates a graph diffusion attention mechanism with adaptive local aggregation to simultaneously preserve spatiotemporal data and road network topology, while effectively addressing the Non-IID data problem across different clients.

Preliminary

In this section, we first define the problem of traffic prediction on graph-structured traffic networks. Subsequently, we introduce the problem of traffic prediction using graph-based deep learning models within the federated learning framework.

Traffic forecasting in transportation networks

Traffic flow prediction is a typical time series forecasting problem, which involves forecasting the traffic values at future N time points based on the traffic data at previous M time points.

In Equation (1), \(v_{t}\in \mathbb {R}^{n}\) represents the observation vector for t road segments at time n, where each element records the historical observation of a single segment. Thanks to the advancement of deep learning, capturing temporal dependencies has become relatively straightforward. At any time t, the model can provide a latent feature matrix \(H^{(t)}\), based on the observations at time t, or prior, which can then be used to predict traffic flow for the next timestamp. Assuming \({\hat{Y}}^{t + 1}\) represents the predicted value for the next timestamp and \(Y^{t + 1}\) represents the actual value, we can train the model by minimizing the L2 regularized sum of absolute errors, \(\left| \big | {\hat{Y}}^{t + 1} - Y^{t + 1} \big | \right|\).

In transportation networks, graph-structured data naturally exists. For instance, road topologies, sensor node topologies, and others can all be represented as nodes or edges within a graph. In this work, we represent a traffic network as an undirected graph \(\mathscr {G} = \left( \mathscr {V},\mathscr {E},\mathscr {A} \right)\) ,where \(\mathscr {V}\) is the set of nodes, \(\mathscr {E}\) is the set of edges, \(\mathscr {A}\,\in \,\mathbb {R}^{N \times N}\) is the adjacency matrix of, \(\mathscr {G}\), which represents the relationship between nodes, N is the number of nodes in \(\mathscr {G}\). For \(\forall v_{i},v_{j} \in \mathscr {V}\) , if \(v_{i}\) and \(v_{j}\) are connected, \(\mathscr {A}_{i,j} = 1\), otherwise \(\mathscr {A}_{i,j} = 0\). Alternatively, we can set \(\mathscr {A}_{i,j}\) to a weight \(\mathscr {W}_{i,j}\), making \(\mathscr {A}\) a weighted adjacency matrix. Graph Convolutional Networks (GCN) have gained widespread popularity in the field of graph neural networks due to their effectiveness and simplicity across a variety of graph tasks and applications. Specifically, the propagation rule for node representations at each layer of a GCN is as follows:

Here, \(\overset{\sim }{A}\ = A + I\) represents the augmented adjacency matrix of the given undirected graph \(\mathscr {G}\), incorporating self-connections to allow nodes to include their own features in the representation updates. \(I\in \,\mathbb {R}^{N \times N}\) is the identity matrix, \(\overset{\sim }{D}\) is a diagonal matrix where each entry \({\overset{\sim }{D}}_{ii} = {\sum _{j}{\overset{\sim }{A}}_{ij}}\). \(\sigma\) is an activation function, such as ReLU. \(W^{k}\in \,\mathbb {R}^{F \times F^{\prime }}\) s a layer-specific trainable linear transformation matrix, where F and \(F^{\prime }\) are the dimensions of the node representations at the k-th and (k+1)-th layers.

Traffic prediction in federated learning

In this section, we will develop a federated learning framework for transportation networks. The distinctive feature of federated learning is that it involves collaboration among two or more participants to build a shared machine learning model, with each participant using only their locally stored data for model training. In the transportation sector, such data is typically held by a limited number of organizations, such as ride-sharing companies and government departments. Each participant i trains a model on their private dataset \(D_{i} = \left\{ \left( x_{j},y_{j} \right) \right\} _{j = 1}^{m_{i}}\), where \(x_{j}\) represents a feature vector in the transportation network (such as time, location, historical traffic flow, etc.), \(y_{j}\) is the corresponding target value, and \(m_{i}\) is the total number of samples held by participant i. In this study, we assume that there is no overlap between the datasets of any two participants, \(D_{i} \cap D_{j} = \emptyset\), which is a common assumption as discussed in research25,30,31. If K participants collaborate to train a deep learning model, they ensure that \(\left\{ D_{1},\ldots ,D_{K} \right\}\) remain localized to maintain the privacy of the data. Thus, each participant has a local model \(\mathscr {G}_{i}^{*}\), and let \(\mathscr {G}^{*} = \left\{ \mathscr {G}_{1}^{*},\mathscr {G}_{2}^{*},\ldots ,\mathscr {G}_{K}^{*} \right\}\) be the collection of these local models. The local model parameters, denoted as \(\theta _{i}\), are optimized on the local data using a specific loss function \(L_{i}\):

Here, \(\mathscr {L}\) denotes the loss function. Upon completion of the training locally, the model parameters \(\theta _{i}\) are transmitted to the server. The server aggregates the local model parameters from the participants to obtain the current global model parameters \(\theta _{t}\). In each training round, participants utilize the current global model to update their local model parameters:

Methodology

This section first introduces a graph diffusion attention-based spatiotemporal graph neural network as the traffic speed prediction model for federated learning clients. Subsequently, we present our proposed client-side local adaptive technique, followed by a systematic exposition of the FL-based traffic flow prediction framework, FedGDAN.

Model framework and module

Figure 2 illustrates the proposed GDAN (Graph Diffusion Attention Network) framework, which is designed to serve as the client-side prediction model within our federated learning framework (FedGDAN) for addressing the traffic flow prediction problem. GDAN primarily consists of three components: (1) an encoder and decoder, which are responsible for encoding and decoding the prediction data; (2) a spatio-temporal embedding (STE) generator, which produces spatio-temporal embeddings to provide initial spatio-temporal information for the encoder and decoder; and (3) a transfer attention layer, which leverages historical and future STEs to refine the encoder’s output, thereby mitigating the propagation of errors. It is noteworthy that GDAN constitutes the core local model executed by each participating client (e.g., vehicle or roadside unit) during the federated learning process in FedGDAN. The following sections provide a more detailed overview of each component of GDAN.

Encoder–decoder architecture

In the multi-step prediction task of traffic flow forecasting, we adopt a sequence-to-sequence (Seq2Seq) architecture32 where both the encoder and decoder are constructed using GDAN networks. Specifically, the encoder is composed of a concat & linear layer, a graph diffusion attention module, a temporal attention module, and a residual & gated fusion layer.The input traffic flow data is first processed by a linear layer to obtain \(H_{\text {out }}^{(0)} \in R^{P \times N \times D}\), where P represents the step of historical traffic signals, N represents the number of nodes, D represents the dimension of hidden states inside the model. In the \(l^{th}\) layer encoder, the inputs consist of the output from the previous layer \(H_{out}^{(l-1)}\) and the historical spatio-temporal embedding (HSTE) \(E_{H} \in R^{P \times N \times D}\).This output is subsequently sent into two attention modules: the graph diffusion attention module and the temporal attention module. The graph diffusion attention module generates \(H_{s}^{(l)}\), representing spatial dependencies, while the temporal attention module produces \(H_{t}^{(l)}\), reflecting temporal dependencies. Finally, these outputs are fused using a residual and gated fusion layer to produce the hidden state representation \(H_{o u t}^{(l)} \in R^{P \times N \times D}\) for the current layer.

Following the encoder, the encoded features \(H_{out}^{(L)}\) are fed into a transition attention layer to obtain future representations \(H_{\text {out }}^{(L+1)} \in R^{Q \times N \times D}\), where L denotes the number of layers in both the encoder and decoder. The transformation from \(H_{{out }}^{(L+1)}\) incorporates both historical and future embeddings to mitigate errors caused by discrepancies between historical and future temporal features.

\(H_{{out }}^{(L+1)}\) serves as the input to the first decoder. The decoder maintains an identical architecture to the encoder, with the exception that it utilizes Future Spatio-Temporal Embedding (FSTE) instead of HSTE as the input to the concat & linear layer. After processing through the \(L^{th}\) decoder, the output \(H_{{out }}^{(2L+1)}\) is passed through two linear layers to generate the final prediction \(\hat{Y} \in \mathbb {R}^{Q \times N \times C}\).

Spatial–temporal embedding generator

The state of traffic is jointly influenced by spatial factors (such as road network structure and the distance between roads) and temporal factors (such as traffic patterns at different times of day). By integrating spatio-temporal information and generating effective Spatio-Temporal Embeddings (STE), the performance of prediction models can be significantly improved. The spatio-temporal embedding generator employed in this study consists of two main components: a spatial embedding generator and a temporal embedding generator. These components are responsible for producing embeddings for spatial and temporal features, respectively. The detailed structure is illustrated in Fig. 3.

To capture the spatial structural information of the traffic network, a predefined adjacency matrix generated from relative distances is first input. This matrix represents the connectivity relationships among nodes in the traffic network. In this study, the Node2Vec33 method is employed to learn such graph structures. Node2Vec generates low-dimensional representations of nodes in the graph through a random walk-based approach, thereby capturing the similarity and structural relationships between nodes. The learned node representations are then fed into two fully connected layers to generate a spatial embedding, which is denoted as \(e_{S}^{v_{i}} \in R^{D}\), here \(v_{i}\) denotes the i-th node in the traffic topology graph of intelligent connected vehicles, and D represents the dimension of the spatial embedding.

To capture temporal features, each time step is independently encoded with respect to both “time of day” and “day of the week.” These features are denoted as \(R_{T}\) and \(R_7\), respectively. By concatenating them, we obtain \(R_{T+7}\), which represents a specific moment within a week. The concatenated temporal features are then fed into a fully connected (MLP) layer, resulting in a temporal embedding \(e_{\textrm{T}} \in R^{D}\). In this model, temporal information is divided into two parts: historical and future. The historical temporal information is represented as \(e_{t_i}^{T} \in R^{D}\), where \(t_{i} \in \left\{ t_{1}, t_{2}, \ldots t_{P}\right\}\), indicating the embeddings for (P) historical time steps. The future temporal information is represented as \(e_{t_j}^{T} \in R^{D}\), where \(t_{j} \in \left\{ t_{P+1}, t_{P+2}, \ldots t_{P+Q}\right\}\) corresponding to the embeddings for (Q) future time steps.

Through a broadcast mechanism, the spatial and temporal embeddings of both historical and future time steps are aggregated, resulting in the generation of historical spatio-temporal embeddings (HSTE), denoted as \((E_H \in \mathbb {R}^{P \times N \times D})\), and future spatio-temporal embeddings (FSTE), denoted as \(E_{F} \in R^{Q \times N \times D}\).

Graph diffusion attention module

To achieve a more refined representation of traffic network topology, this paper develops a graph diffusion attention module that captures the spatial dependencies between nodes from both local and global perspectives. Conventional graph convolution operations extract features through weighted aggregation over local neighborhoods. By contrast, graph diffusion convolution integrates the concept of diffusion processes into data processing, accounting for the propagation of information across the spatial domain. This approach enables more effective modeling of the global structures inherent in the data, with its corresponding formulation presented as follows:

Where X denotes the input features, A represents the adjacency matrix, \(W^{k}\) indicates learnable parameters, and \(H^{K}\) denotes the output signals of the graph diffusion convolution.Graph diffusion convolution captures multi-level information of nodes and their neighbors by aggregating features across different orders of adjacency matrices. However, it still relies on a predefined adjacency matrix, where the weights of neighboring nodes are fixed and cannot be dynamically adjusted. Moreover, it does not account for potential relationships between nodes that fall outside the given graph structure. These limitations restrict the model’s ability to represent complex graph structures. To address this issue, this paper combines Graph Attention Networks34 (GAT) with an adaptive matrix, enabling dynamic adjustment of node relationships and improving the model’s capacity to capture intricate dependencies within the graph.

When incorporating the concept of Graph Attention Networks (GAT) into diffusion convolution, the adjacency matrix of each order \(A^k\) can be replaced by an attention weight matrix \(\alpha ^{(k)}\). The diffusion convolution operation is thus reformulated as:

Where \(\alpha ^{(k)}\) represents the attention weight between nodes at the (k)-th order, which is adaptively learned through the GAT mechanism.To better capture hidden spatial dependencies, we introduce an adaptive adjacency matrix into the model framework to account for the directional characteristics of traffic flow20. The adaptive matrix can be represented as:

Where Here, \(E_1, E_2 \in {R}^{N \times C}\) are learnable parameters initialized randomly, representing the source node embeddings and target node embeddings, \(A_{adp} \in {R}^{N \times N}\) represents the forward propagation process of traffic flow.

Therefore, the graph diffusion attention Network module can be defined as:

Where \(W_{A}^{k},W_{a d p}\) are learnable parameters, and \(H_A^{0}, H_{adp}^{0}=H^{(0)}\).The Graph Diffusion Attention Module employed in this study is illustrated in Fig. 4.

Temporal attention

The traffic condition of a given road segment is not only influenced by the states of adjacent roads, but also significantly affected by the historical traffic patterns at that particular location over time. The purpose of the temporal attention mechanism is to assign adaptive weights to historical traffic data along the time axis, thereby capturing temporal dependencies between different time steps.

To effectively model the temporal dependencies of each node across time, three matrices are constructed for each node: a query matrix Q, a key matrix K, a value matrix V. Specifically, for a given node \(v_i\) at each time step, the query, key, and value are defined as follows:

Here \(f_{t, 1},f_{t, 2},f_{t, 3}\) denote the transformation functions applied to the node features at different time steps through a shared function f. \(H_{v_{i}}^{(l)}\) represents the feature embedding of node \(v_i\) at the l-th layer.

The calculation of the similarity between the query Q and the key K followed by normalization to derive the attention weights, is performed using the attention mechanism. The formula is expressed as follows:

Here, \(\sigma\) represents the activation function, and D denotes the dimensionality of the feature space, which is utilized to scale the operation and ensure numerical stability. The dot product between \(Q_{v_i}\) and \(K_{v_i}\) quantifies the correlation between the query and the key. Subsequently, the softmax function normalizes the attention score matrix, thereby generating the attention weight matrix. This attention weight matrix is then multiplied with the value matrix \(V_{v_i}\) to compute the temporal feature \(H_{t, v_i}^{(l)}\).

Attention transformation module

To mitigate the error propagation effects caused by discrepancies between historical temporal features and predicted future temporal features, an attention transformation module is introduced between the encoder and decoder. This module models the correlation between the temporal features of each predicted timestep and those of each historical timestep. Consequently, the flow characteristics of the encoded data are transformed into representations of the future and subsequently fed into the decoder. Any correlation between the predicted temporal length and the historical temporal length is measured by the associated STE metric. The formula is described as follows:

Model parameter protection based on differential privacy

To ensure rigorous privacy guarantees while enabling collaborative traffic flow prediction in intelligent connected vehicle systems, we integrate differential privacy (DP) into the FedGDAN framework.

We adopt an honest-but-curious server threat model, in which the server faithfully follows the federated learning protocol but may still attempt to infer sensitive information about individual clients from the uploaded model parameters35. In addition, we consider the risk of adversaries intercepting model updates during communication. Without proper protection, the transmitted parameters could inadvertently reveal information about driver behaviors. To mitigate this risk, each client performs a two-step protection process before transmitting updates to the server. First, model gradients are clipped to bound the sensitivity of individual sample updates. Next, calibrated Gaussian noise is added to the clipped parameters. Only after this preprocessing step are the updates uploaded, thereby ensuring stronger privacy protection.

Our framework follows the standard definition of \((\epsilon ,\delta )\text {-}\)differential privacy,which provides a quantifiable privacy guarantee. Here, \(\epsilon >0\) quantifies the maximum distinguishability between any two neighboring datasets \(D_i\) and \(D_i^{\prime }\) with respect to all possible outputs on database X, while \(\delta\) denotes the probability that the output distribution deviates from the \(e^{\epsilon }\) bound. With a fixed \(\delta\), a larger value of \(\epsilon\) implies weaker privacy protection, since it makes the two neighboring datasets easier to distinguish, thereby increasing the risk of privacy leakage.

To enforce \((\epsilon ,\delta )\text {-}\) differential privacy, we employ the Gaussian mechanism as described in reference36. In particular, Gaussian noise sampled from \(n \sim \mathscr {N}\left( 0, \sigma ^{2}\right)\) is added to the model parameters, and the noise scale is chosen as \(\sigma \ge c \Delta s / \epsilon\), where \(c>\sqrt{2 \ln (1.25 / \delta )}\) holds for \(\epsilon \in (0,1)\). Here \(\Delta s\) represents the sensitivity of a function s, defined as \(\Delta s=\max _{\mathscr {D}_{i}, \mathscr {D}_{i}^{\prime }}\left\| s\left( \mathscr {D}_{i}\right) -s\left( \mathscr {D}_{i}^{\prime }\right) \right\|\), with s being a real-valued function. In this way, n is the additive noise applied to each data item, ensuring that the transmitted model updates satisfy rigorous differential privacy guarantees.

Adaptive local aggregation

In traditional federated learning (e.g., FedAvg), the server distributes the global model to clients, and the local model of each client is entirely overwritten by the global model, which serves as the initialization for local training. This process can be expressed as:

Here \(\Theta _{i}^{t-1}\) denotes the local model of client i in round \(t-1\), and \(\Theta ^{t-1}\) represents the global model. This approach assumes that the discrepancy between local and global tasks is minimal, allowing the global model to generalize effectively across all clients.This unified initialization paradigm essentially ignores the statistical heterogeneity between clients, resulting in a decrease in the accuracy of the FedAvg algorithm under non-IID data distribution37.

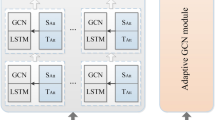

This paper introduces an improved method that employs element-wise weighted fusion of the global and local models, rather than simple overwriting, as shown in Fig. 5. Specifically, a weighted Hadamard product (element-wise multiplication) is used to combine the two models, formulated as:

In this equation, \(\odot\) denotes the Hadamard product, while \(W_{i, 1}\) and \(W_{i, 2}\) are the weighting parameters for the local and global models, respectively, subject to the constraint \(W_{i, 1}+W_{i, 2}=1\) (i.e., the weights sum to 1). If the traditional overwriting method is applied, it is equivalent to setting \(W_{i, 1}=0\) and \(W_{i, 2}=1\), meaning the global model completely replaces the local model.

Learning these weighting parameters \(W_{i, 1}\) and \(W_{i, 2}\) via gradient methods is challenging. To address this, the formulation is redefined as:

Here, \(\Theta ^{t-1}-\Theta _{i}^{t-1}\) is treated as an “update” term, while element-wise weight clipping is applied to regularize these weights:

Since the lower layers of deep neural networks typically learn more general features, while the higher layers capture task-specific representations, we introduce a method to control the scope of Adaptive Local Aggregation (ALA) using a hyperparameter p. In particular, the lower layers of the model are directly aligned with the global model, while ALA is applied only to the final linear layer of GDAN. The other layers remain frozen during the ALA process, as illustrated in Fig. 6.which effectively reduces the computation overhead. The mathematical representation is as follows:

In this equation, \(1^{\Theta _{i}-p}\) represents the constant matrix of the lower layers (with all elements initialized to 1), \(W_{i}^{p}\) denotes the weighted matrix of the upper layers, and all matrices are initialized to 1 at the beginning.

During the initialization phase, the weight value for each client i is set to 1. This implies that at the beginning of the process, the local model of the client fully relies on the parameters of the global model without any additional local adjustments. This initialization strategy simplifies the early model updates and reduces the computational complexity during initial training. Throughout the training process, the weights \(W_i^p\) are optimized using a gradient-based learning method. The update rule is expressed as follows:

In this equation, \(\eta\) represents the learning rate, \(\nabla _{W_i^p}\) is the gradient with respect to \(W_i^p\), \(L\left( \Theta _i^t, D_{i,s}^t, \Theta ^{t-1}\right)\) denotes the loss function, which is computed using the local dataset \(D_{i,s}^t\), the local model parameter \(\Theta _i^t\), and the global model parameter \(\Theta ^{t-1}\).

To minimize computational burden, during each iteration, client i does not train using the entire dataset \(D_i\) , but rather randomly selects \(s\%\) of the data samples from \(D_{i,s}\) to train \(W_i^p\). This approach reduces computational load during training, especially for clients with large datasets, thereby significantly alleviating communication and computational pressure. Aside from learning \(W_i^p\), all other parameters (including those of the global model and local model) remain frozen during training, meaning these parameters do not participate in gradient updates. This implies that during local adaptive weight updates, computational complexity is further reduced, focusing solely on the updates of \(W_i^p\).

During the training process, \(W_i^p\) is primarily trained during the initial phase (specifically in the second iteration) and tends to converge after several training rounds. Since \(W_i^p\) learns the weighting strategy between the global and local models, it effectively identifies an appropriate weighting scheme early in the training process and exhibits minimal changes in subsequent iterations, with updates becoming nearly negligible. Once \(W_i^p\) converges in the second iteration, it can be reused in subsequent iterations. This approach not only reduces computational overhead but also eliminates the need to retrain \(W_i^p\) in every iteration. For iterations where \(t>2\) only a single epoch of training is required for \(W_i^p\) to adapt to minor variations in model parameters.

In the first iteration, local adaptation is inactive because the global and local models are identical, i.e., \(\Theta _{0}=\Theta _{0}^{i}, \forall i \in [N]\) Consequently, during the first iteration, each client’s local model is directly copied from the global model without any weighting operations.

Learning process of FedGDAN

FedGDAN is a distributed traffic flow prediction algorithm based on the federated learning framework. When aggregating parameters, it utilizes the FedAvg algorithm to construct a global model. The FedAvg algorithm can be expressed as follows:

where \(\Theta _{i}^{t}\) denotes the local model parameters of client i, \(S_{t}\) represents the set of clients participating in round t, \(n_{k}\) corresponds to the local data volume of client k, \(n = \sum _{k \in S_{t}} n_{k}\) defines the aggregate data volume from participating clients in round t, and \(\Theta ^{t}\) constitutes the aggregated global model parameters.

When the global model is transmitted back to the client and the client performs local model updates, we employ an adaptive local aggregation algorithm.The training process diagram is shown in Fig. 7. The complete training workflow, as illustrated by Algorithm 1, outlines the key components of each training round in FedGDAN, which include:

-

Global Model Initialization: The server initializes the global model \(\Theta ^{0}\) and distributes it to all participating clients to provide a common starting point for training.

-

Local Model Updates: After receiving the global model \(\Theta ^{g}\), each client performs updates using the Adaptive Local Algorithm (ALA). This process involves data sampling, localized adaptive training, and parameter pruning. To protect privacy, gradients are clipped and calibrated noise is added before uploading parameters to the server.

-

Global Model Aggregation: The server gathers the updated parameters from all clients, integrates them according to the participation ratio \(\rho\), and updates the global model through weighted averaging to form the next iteration.

Experiment

Dataset description and pre-processing

This study utilizes three primary datasets: PEMSD7-m, PeMS-BAY, and METR-LA, all derived from the public transportation system in California, USA. These datasets primarily provide road traffic information.

-

PeMSD7(M) Dataset:This dataset pertains to California’s District 7, primarily covering the Los Angeles County area. It includes data collected from approximately 228 sensors, with each sensor recording data at five-minute intervals. Each sensor has captured a total of 12,671 data points.

-

PEMS-Bay Dataset:This dataset focuses on the San Francisco Bay Area and comprises data collected by approximately 325 sensors. Similar to other datasets, the sensors record data at five-minute intervals, with each sensor collecting 52,115 data points.

-

METR-LA Dataset:The METR-LA dataset provides traffic information for the Los Angeles Metropolitan Area, encompassing 207 sensors. Each sensor logs data at five-minute intervals, resulting in a total of 34,271 data points per sensor.

In this study, a traffic network’s expanded graph is represented as a directed graph \(\mathscr {G}=(\mathscr {V}, \mathscr {E}, \mathscr {A})\), where \(\mathscr {V}\) denotes the set of nodes, \(\mathscr {E}\) represents the set of edges, and \(\mathscr {A} \in \mathbb {R}^{N \times N}\) is the adjacency matrix that characterizes the relationship between nodes. Here, N denotes the number of nodes, and for any \(v_i, v_j \in V\), if \(v_i\) and \(v_j\) are connected, then \(\mathscr {A}_{ij} = 1\); otherwise, \(\mathscr {A}_{ij} = 0\). In conventional graph representations, the adjacency matrix \(\mathscr {A}\) is binary. However, to more accurately reflect the real-world dynamics of traffic networks, this paper employs a weighted adjacency matrix. The value \(\mathscr {A}_{ij}\) is assigned a weight \(W_{ij}\), which is determined based on road distance. This approach allows the weighted adjacency matrix \(\mathscr {A}\) to better capture the complexity of relationships within the traffic network.

In this context, \(\mathscr {A}_{ij}\) represents the weight of the edge between nodes \(v_i\) and \(v_j\) in the expanded traffic graph. The weight is determined based on the distance between node \(v_i\) and node \(v_j\). The parameters \(\sigma ^2\) and k are used to control the distribution and sparsity of the adjacency matrix \(\mathscr {A}\), and are respectively set to 10 and 0.5 in this study.

To better reflect the distributional differences of real-world traffic environments, this study simulates Non-IID traffic flow prediction scenarios under the federated learning framework. First, we construct input–output samples using a sliding window approach: the input consists of traffic speed observations from the past 12 time steps, and the output is the predicted speed for the next 12 time steps. To further characterize each sample, we compute a label feature by averaging the sequence across both temporal and spatial dimensions, resulting in a value that reflects the overall traffic load level at that time.

Based on this label feature, we then discretize the traffic states using binning. Specifically, all label values are divided into 5 intervals, and each sample is assigned to a corresponding bin according to its label value. This binning strategy effectively represents traffic samples at different load levels.

To further introduce heterogeneity at the client level, we employ a Dirichlet distribution \(Dir(\alpha )\) to generate sampling proportions for each client across the bins (with \(\alpha =0.5\) in this study). When \(\alpha\) is small, the distribution of samples across bins varies greatly between clients, resulting in stronger Non-IID characteristics. In contrast, larger values of \(\alpha\) yield more uniform distributions across clients, approaching the IID condition.

During sample allocation, each client receives the same total number of samples, but the internal composition strictly follows the Dirichlet-determined proportions. This approach ensures that, while maintaining balance in overall sample size, clients exhibit heterogeneous data distributions across bins, thereby reflecting realistic Non-IID characteristics. To validate the rationality of this strategy, we further examine the sample distribution differences across bins for different clients and measure the degree of Non-IID using the Jensen–Shannon Divergence (JSD). Taking the METR-LA dataset as an example, the final customer sample distribution and JSD value are shown in Figure 8.

Parameter settings

We implemented our experiments using the PyTorch framework on a Windows 11 system equipped with an NVIDIA 3060Ti GPU. All samples utilized a historical time window of 60 minutes to predict traffic conditions for the next 15 minutes, 30 minutes, and 60 minutes. Local training on client devices was conducted for one epoch, while global training consisted of 30 epochs. The random seed was set to 42, the learning rate was 0.001, the dropout rate was 0.5, the weight decay rate was 0.0005, and the Adam optimizer was employed. The loss function used for training was Mean Absolute Error.

In the federated learning setting, the number of participating clients was set to 8. To ensure data privacy, the privacy budget \(\epsilon\) was set to 20, the failure probability \(\delta\) was designated as 0.01, and the clipping threshold C was assigned a value of 20, which aligns with common practices in FL36.

The predictive performance of the model was compared across horizons of 15 minutes (H=3), 30 minutes (H=6), and 1 hour (H=12) using the metrics MAE, RMSE, and MAPE. These metrics represent the model’s effectiveness in short-term, mid-term, and long-term predictions under the 1-hour forecasting task.

Baselines

To evaluate the effectiveness of FedGDAN, this study compares FedGDAN with federated learning-based methods built upon several traditional approaches. A brief introduction to each method is as follows:

FedGRU25: A federated learning-based gated recurrent unit neural network algorithm proposed for traffic flow prediction. It updates the universal learning models through a secure parameter aggregation mechanism, eliminating the need to directly share raw data among organizations. The FedAvg algorithm is adopted within the secure parameter aggregation mechanism to reduce communication overhead during the transmission of model parameters.

FedASTGCN13: A federated learning framework integrated with an attention-based spatial-temporal graph neural network (ASTGNN) designed for traffic speed forecasting. This approach combines the ASTGNN model with federated learning to achieve traffic speed prediction.

FedGCN27: A short-term traffic flow prediction model that combines community detection-based federated learning with graph convolutional networks (GCNs). This model addresses the challenges of time-consuming training, higher communication costs, and data privacy risks associated with global GCN models as the volume of data increases.

DeFedSTTN28: A spatial-temporal transformer network proposed to replace existing graph convolutional networks for personalized local learning of each participant. Furthermore, a decentralized federated learning model is designed to fuse personalized local models for traffic speed prediction.

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of different methods in traffic flow prediction tasks, three commonly used evaluation metrics are adopted: Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), and Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE). These metrics quantify the accuracy and error of the prediction results from different perspectives, with their definitions provided as follows:

Where \(y, \hat{y}\) represent the true and predicted values, respectively, and N represents the length of the prediction window, set to \(N = 12\) for the purposes of our experiments.

Experiment results

This study presents a comprehensive evaluation of FedGDAN’s performance across three benchmark datasets, covering prediction tasks at 15-minute (short-term), 30-minute (mid-term), and 60-minute (long-term) intervals. Through systematic comparisons with four state-of-the-art models, our results demonstrate that FedGDAN consistently outperforms the baselines in all experimental settings, as summarized in Table 1. The model achieves optimal or near-optimal results in three evaluation metrics, MAE, RMSE, and MAPE, with particularly notable gains in long-term forecasting. For example, on the PeMSD7(M) dataset, FedGDAN reduces MAE by 7.1%, RMSE by 7.0%, and MAPE by 9.5% compared to the baseline FedGRU, while also maintaining substantial improvements of 4.6%, 3.7%, and 3.4% over the suboptimal FedGCN model, as depicted in Fig. 9.

FedASTGCN and FedGRU exhibit comparable performance, suggesting that the mere inclusion of sophisticated attention mechanisms offers limited advantage in federated learning contexts. Notably, FedGRU shows the weakest performance in long-term forecasting, underscoring the inherent constraints of GRU units in capturing complex spatiotemporal dependencies. Although FedGDAN delivers competitive accuracy in short-term predictions, its superiority becomes increasingly evident in long-term scenarios, highlighting the efficacy of its novel design.

Table 1d demonstrates FedGDAN’s superior robustness against data heterogeneity across different Non-IID levels controlled by parameter \(\alpha\). Under the strongest Non-IID setting, FedGDAN achieves the best performance and exhibits the smallest performance degradation as data heterogeneity increases. Its MAE increases by only 8.7% from \(\alpha =5.0\) to \(\alpha =0.1\), significantly less than other methods. This minimal performance variance confirms the effectiveness of our adaptive local aggregation mechanism in handling statistical heterogeneity.

To assess the practical viability of FedGDAN in privacy-sensitive applications, we systematically evaluated the trade-off between privacy protection strength and prediction accuracy under different differential privacy parameters. Fig. 9c illustrates the test MAE evolution across various privacy budgets compared to the non-private baseline on the PEMSD7-M dataset. A smaller \(\epsilon\) leads to a higher MAE due to increased noise injection. Specifically, the convergence curve for \(\epsilon =5\) shows the highest MAE, followed by \(\epsilon =10\) and \(\epsilon =20\).

To comprehensively evaluate the scalability of FedGDAN in practical federated learning scenarios, we conducted systematic experiments examining the impact of varying client numbers on prediction performance. As shown in Fig. 9d, the test MAE under different client configurations exhibits a consistent convergence trend. After sufficient communication rounds, all configurations achieve comparable performance, and the negligible variance among them underscores the excellent scalability and stability of the proposed FedGDAN framework.

Ablation study

To validate the importance of individual modules in our proposed model, we designed five variant models through systematic module ablation. FedNSTE (without the spatiotemporal embedding generator), FedNGDA (without the graph diffusion attention module), FedNTA (without the temporal attention module), FedNTRA (without the transformer attention module) and FedNALA (without the adaptive aggregation module). The experimental results of these variants on the PeMSD7(M) dataset for the prediction of 60 minutes are presented in Table 2.

The experimental results demonstrate that FedGDAN achieves the lowest MAE of 2.48 among all compared methods, indicating superior prediction accuracy with minimal errors. This significant performance advantage confirms that the complete FedGDAN architecture substantially outperforms its ablated variants, highlighting the crucial contribution of each module in modeling complex spatiotemporal correlations.

Particularly noteworthy are the most pronounced performance degradations observed in the FedNGDA and FedNALA variants. The substantial performance drop in FedNGDA underscores the critical importance of graph neural networks in capturing spatial dependencies within traffic networks. Meanwhile, the deteriorated performance of FedNALA reveals the essential role of adaptive aggregation strategies in handling Non-IID data distributions - a fundamental challenge in federated learning scenarios. These findings collectively validate our architectural design choices for addressing both spatial and federated learning-specific challenges in traffic prediction tasks.

Conclusion

This study proposes FedGDAN, a federated learning framework for traffic flow prediction that addresses the challenges of privacy preservation and Non-IID data in federated traffic forecasting, while effectively capturing complex spatiotemporal dependencies. FedGDAN employs an encoder–decoder architecture that integrates graph diffusion attention with temporal attention, enabling more effective extraction of spatiotemporal dependencies than conventional models. The Adaptive Local Aggregation strategy replaces conventional global model overwriting with element-wise fusion of local and global parameters, thereby alleviating Non-IID issues while minimizing computational overhead. Extensive experiments and ablation studies on three benchmark datasets demonstrate that FedGDAN consistently outperforms state-of-the-art baselines, exhibiting strong scalability, a balanced trade-off under differential privacy, and robust performance across heterogeneous data distributions.

Data availability

The data used in this study are all publicly available datasets: • PeMSD7(M): https://dot.ca.gov/programs/traffic-operations/mpr/pems-source. • PEMS-Bay: https://github.com/liyaguang/DCRNN. • METR-LA: https://github.com/liyaguang/DCRNN.

References

Zhang, J. et al. Data-driven intelligent transportation systems: A survey. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 12, 1624–1639 (2011).

Tubaishat, M., Zhuang, P., Qi, Q. & Shang, Y. Wireless sensor networks in intelligent transportation systems. Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing 9, 287–302 (2009).

Guerrero-Ibáñez, J., Zeadally, S. & Contreras-Castillo, J. Sensor technologies for intelligent transportation systems. Sensors 18, 1212 (2018).

Dimitrakopoulos, G. & Demestichas, P. Intelligent transportation systems. IEEE Vehicular Technology Magazine 5, 77–84 (2010).

McMahan, B., Moore, E., Ramage, D., Hampson, S. & Aguera y Arcas, B. Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralized data. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics (AISTATS), 1273–1282 (2017).

Liu, Y. et al. Vertical federated learning: Concepts, advances, and challenges. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 36, 3615–3634 (2024).

Gal, M. S. & Aviv, O. The competitive effects of the gdpr. Journal of Competition Law & Economics 16, 349–391 (2020).

Fang, S., Zhang, Q., Meng, G., Xiang, S. & Pan, C. Gstnet: Global spatial-temporal network for traffic flow prediction. In Proceedings of the 28th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI), 2286–2293 (2019).

Ye, J., Zhao, J., Ye, K. & Xu, C. How to build a graph-based deep learning architecture in traffic domain: A survey. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 23, 3904–3924 (2020).

Pekar, A., Makara, L. A. & Biczok, G. Incremental federated learning for traffic flow classification in heterogeneous data scenarios. Neural Computing and Applications 36, 20401–20424 (2024).

Wang, S., Yu, D., Ma, X. & Xing, X. Analyzing urban traffic demand distribution and the correlation between traffic flow and the built environment based on detector data and pois. European Transport Research Review 10, 50 (2018).

Li, P. et al. Core network traffic prediction based on vertical federated learning and split learning. Scientific Reports 14, 4663 (2024).

Zhang, C., Zhang, S., James, J. & Yu, S. Fastgnn: A topological information protected federated learning approach for traffic speed forecasting. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 17, 8464–8474 (2021).

Nagy, A. M. & Simon, V. Survey on traffic prediction in smart cities. Pervasive and Mobile Computing 50, 148–163 (2018).

Ma, X. et al. Learning traffic as images: A deep convolutional neural network for large-scale transportation network speed prediction. Sensors 17, 818 (2017).

Yu, H., Wu, Z., Wang, S., Wang, Y. & Ma, X. Spatiotemporal recurrent convolutional networks for traffic prediction in transportation networks. Sensors 17, 1501 (2017).

Chen, C. et al. Gated residual recurrent graph neural networks for traffic prediction. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 33, 485–492 (2019).

Zhao, L. et al. T-gcn: A temporal graph convolutional network for traffic prediction. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 21, 3848–3858 (2019).

Bai, L., Yao, L., Li, C., Wang, X. & Wang, C. Adaptive graph convolutional recurrent network for traffic forecasting. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 33, 17804–17815 (2020).

Wu, Z., Pan, S., Long, G., Jiang, J. & Zhang, C. Graph wavenet for deep spatial-temporal graph modeling. arXiv preprint arXiv:1906.00121 (2019).

Wu, Z. et al. Connecting the dots: Multivariate time series forecasting with graph neural networks. In Proceedings of the 26th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (KDD), 753–763 (2020).

Zheng, C., Fan, X., Wang, C. & Qi, J. Gman: A graph multi-attention network for traffic prediction. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 34, 1234–1241 (2020).

Guo, S., Lin, Y., Feng, N., Song, C. & Wan, H. Attention based spatial-temporal graph convolutional networks for traffic flow forecasting. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 33, 922–929 (2019).

Song, J. et al. St-gat: A spatio-temporal graph attention network for accurate traffic speed prediction. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management (CIKM), 4500–4504 (2022).

Liu, Y., James, J., Kang, J., Niyato, D. & Zhang, S. Privacy-preserving traffic flow prediction: A federated learning approach. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 7, 7751–7763 (2020).

Zeng, T. et al. Multi-task federated learning for traffic prediction and its application to route planning. In Proceedings of the IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), 451–457 (2021).

Xia, M., Jin, D. & Chen, J. Short-term traffic flow prediction based on graph convolutional networks and federated learning. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 24, 1191–1203 (2022).

Shen, X., Chen, J., Zhu, S. & Yan, R. A decentralized federated learning-based spatial-temporal model for freight traffic speed forecasting. Expert Systems with Applications 238, 122302 (2024).

Liu, Q., Sun, S., Liu, M., Wang, Y. & Gao, B. Online spatio-temporal correlation-based federated learning for traffic flow forecasting. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems (2024).

Feng, J., Rong, C., Sun, F., Guo, D. & Li, Y. Pmf: A privacy-preserving human mobility prediction framework via federated learning. Proceedings of the ACM on Interactive, Mobile, Wearable and Ubiquitous Technologies 4, 1–21 (2020).

Chen, M. et al. A joint learning and communications framework for federated learning over wireless networks. IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications 20, 269–283 (2020).

Sutskever, I., Vinyals, O. & Le, Q. V. Sequence to sequence learning with neural networks. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 27 (2014).

Grover, A. & Leskovec, J. node2vec: Scalable feature learning for networks. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (KDD), 855–864 (2016).

Velickovic, P. et al. Graph attention networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1710.10903 (2017).

Fredrikson, M., Jha, S. & Ristenpart, T. Model inversion attacks that exploit confidence information and basic countermeasures. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGSAC conference on computer and communications security, 1322–1333 (2015).

Wei, K. et al. Federated learning with differential privacy: Algorithms and performance analysis. IEEE transactions on information forensics and security 15, 3454–3469 (2020).

Zhao, Y. et al. Federated learning with non-iid data. arXiv preprint arXiv:1806.00582 (2018).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.H.L: Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis. B.M: review and editing. R.Z: software, validation, data curation. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Y., Mi, B. & Zeng, R. FedGDAN: Privacy-preserving traffic flow prediction via federated graph diffusion attention networks. Sci Rep 15, 41080 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24963-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24963-z