Abstract

Programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) has emerged as a key biomarker in determining both the progression and prognosis of gastric cancer (GC). Consequently, its detection through immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis is essential for guiding appropriate treatment selection. We conducted an analytical, observational study based on a five-year retrospective cohort of patients diagnosed with gastric cancer at a comprehensive oncology center in Colombia. All patients underwent immunohistochemistry (IHC) to assess PD-L1 expression and calculate the Combined Positive Score (CPS). The objective of this study was to compare the positivity detection rates between the 28-8 and 22C3 assays and to evaluate the concordance between them. A descriptive analysis of clinical and pathological variables was performed. Univariate analysis was used to determine the frequency of PD-L1 expression and CPS distribution. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was applied and stratified by PD-L1 status. Concordance between the two assays was assessed using the kappa (κ) index. A total of 175 patients diagnosed with gastric cancer (GC) and tested for PD-L1 expression were included in the study. Complete pathological and IHC data were available for 155 patients. Among them, 39.4% were tested with the 28-8 assay, and 60.6% with the 22C3 assay. PD-L1 positivity was observed in 34.4% of cases using the 28-8 assay and in 28.7% using the 22C3 assay. Among patients with available follow-up data (n = 34), PD-L1 testing was performed using the 22C3 clone, with a positivity rate of 35.3%. In the subgroup analysis of patients tested with both antibodies (n = 20), 60% were PD-L1 positive. Within this subset, 25% had a CPS of 1–4, 16.7% had a CPS of 5–9, and 58.3% had a CPS ≥ 10. For the 22C3 assay specifically, PD-L1 positivity was observed in 40% of cases, with 37.5% having a CPS of 1–4 and 62.5% a CPS ≥ 10; notably, no cases in this group had a CPS of 5–9. The concordance rate between the 28-8 and 22C3 assays was 61%, as measured by the kappa index. The 28-8 clone identified a higher proportion of patients with PD-L1 expression compared to the 22C3 antibody. However, both assays demonstrated a concordance rate of 61%. In the study population, the subgroup with a Combined Positive Score (CPS) ≥ 10 was the most prevalent, suggesting that high PD-L1 expression is relatively common and potentially clinically relevant in this cohort.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gastric cancer (GC) is a neoplastic disease of multifactorial etiology, characterized by the uncontrolled proliferation of tumor cells within the gastric mucosa1,2,3. t primarily affects men over the age of 70, particularly in Asia, Europe, and Latin America. Although the incidence has declined in North America and Western Europe over the past six decades, GC remains the fifth most common cancer worldwide, accounting for approximately 723,100 deaths annually4,5. In Colombia, as of 2022, GC was the fifth most frequent malignancy, with 13,485 prevalent cases, 2,353 new diagnoses, and 2,656 deaths reported6.

GC is often diagnosed at advanced stages, primarily due to the absence of symptoms during its early phases. This diagnostic delay significantly reduces the likelihood of curative treatment. The most common signs and symptoms of advanced GC include dysphagia, fatigue, indigestion, vomiting, weight loss, early satiety, and iron deficiency anemia7. However, these manifestations are nonspecific, contributing to delayed clinical suspicion and accounting for late-stage diagnoses in up to 80% of cases8. A definitive diagnosis requires endoscopic evaluation, tissue sampling, and histopathological analysis of biopsy specimens7.

Programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) and its ligand (PD-L1) are expressed in various malignancies, where they inhibit the immune response by suppressing CD4 + and CD8 + T lymphocyte activity and cytokine production. This immune evasion mechanism facilitates tumor proliferation. Moreover, PD-1 and PD-L1 expression levels may increase following Helicobacter pylori infection9.

The PD-1/PD-L1 axis is a key immunoregulatory pathway that sustains immune homeostasis by suppressing T cell–mediated responses. Its role within the intricate tumor microenvironment is pivotal for the development of effective immunotherapies. Comprehensive profiling of the immune, genomic, and transcriptomic landscape in cancer has enhanced understanding of why some patients respond to anti–PD-1/PD-L1 therapy while others do not. Immune checkpoint inhibitors have shown transformative efficacy across multiple malignancies, prompting ongoing research to refine patient selection, unravel resistance mechanisms, and improve biomarkers such as PD-L1 expression and tumor mutational burden (TMB). Consequently, the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway remains a cornerstone of translational and clinical oncology research10.

In recent years, programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) has emerged as a critical biomarker in oncology due to its dual role in prognosis and in predicting response to immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs). Its evaluation via immunohistochemistry (IHC) has been widely adopted in routine clinical practice across several tumor types, serving as a stratification tool for anti–PD-1/PD-L1 therapies such as nivolumab, pembrolizumab, and atezolizumab10,11.

In the context of advanced gastric cancer, PD-L1 has gained particular clinical significance. Its expression, measured using the Combined Positive Score (CPS)—which includes both tumor and immune cells—has shown predictive value in large-scale trials such as CheckMate 649, where patients with a CPS ≥ 5 derived substantial benefit from first-line chemoimmunotherapy. These findings have been reinforced by systematic reviews that demonstrate an association between high PD-L1 expression and poorer prognosis, as well as enhanced responsiveness to ICIs in several gastrointestinal malignancies, including gastric cancer10,11.

Beyond gastric adenocarcinoma, PD-L1 expression has shown therapeutic relevance in other tumor types such as non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), urothelial carcinoma, melanoma, triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), and sarcomatoid tumors. For example, in TNBC, elevated PD-L1 levels are associated with increased immune cell infiltration and enhanced sensitivity to immunotherapy12,13. In sarcomatoid tumors—including those of pulmonary and renal origin—PD-L1 is significantly overexpressed, suggesting potential clinical utility for ICIs12,13. Additionally, in broader gastrointestinal malignancies such as colorectal and hepatocellular carcinoma, PD-L1 expression has been linked to adverse clinical outcomes and response to immunotherapy, further supporting its value as a cross-cutting biomarker in oncology11.

The advent of immune checkpoint inhibitors targeting PD-1/PD-L1 has markedly improved survival outcomes in select subgroups of patients with advanced or metastatic GC. These therapies leverage the immune system to recognize and destroy tumor cells and have demonstrated more durable responses compared to conventional treatments. Studies show that patients with high PD-L1 expression or microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) tumors benefit significantly from immunotherapy, leading to the incorporation of these biomarkers into clinical decision-making. Nonetheless, challenges remain, including acquired resistance and the identification of ideal candidates for these therapies, although immunotherapy has undoubtedly renewed therapeutic optimism for patients with advanced GC14.

In this setting, it is essential to consider not only classical adenocarcinoma subtypes but also rare histological variants with distinct molecular and immunological characteristics. Tumors such as micropapillary adenocarcinoma, hepatoid adenocarcinoma, and gastroblastoma—a rare biphasic neoplasm initially described in young adults but recently observed in older patients—have been identified in recent series as expressing immunologic markers such as PD-L1. This opens potential therapeutic avenues, even within these atypical histologies15,16. In such cases, PD-L1 evaluation may contribute not only to diagnostic clarification but also to immunologic stratification, especially in advanced disease settings where immunotherapy is under consideration. Thus, expanding the diagnostic framework to include these uncommon histological subtypes—together with appropriate molecular and IHC assessment—is crucial for refining patient selection for PD-1/PD-L1–targeted therapies.

Currently, PD-L1 detection is conducted using different IHC assays, including the PD-L1 22C3 and 28-8 pharmDx clones. Comparative studies have assessed the concordance and diagnostic equivalence between these assays. Some data suggest that the 28-8 clone may yield higher CPS values and increased PD-L1 positivity; however, other studies offer contradictory findings17. Therefore, the present study aimed to describe the frequency of PD-L1 expression in a Latin American cohort of patients with GC, along with their clinical characteristics. Additionally, it sought to compare the detection rates and concordance of the 28-8 and 22C3 assays in a cohort of Colombian patients treated at a tertiary-level oncology center.

Materials and methods

A descriptive observational study was conducted on a retrospective cohort of patients diagnosed with gastric cancer (GC), as recorded in the databases of the Carlos Ardila Lülle Oncology Institute and the Department of Pathology at Fundación Santa Fe de Bogotá. Eligible patients were over 18 years of age, had a histopathologically confirmed diagnosis of GC, underwent programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression testing, and had institutional clinical follow-up for up to five years. The immunotherapy agents considered in this study were ipilimumab, nivolumab, and pembrolizumab.

For the histological analysis, specimen type (surgical specimen or biopsy) was identified only for the 20 additional patients included in the comparison of PD-L1 expression using the 28-8 and 22C3 antibody clones in tumor tissue from confirmed GC cases. This subgroup comprised 20 patients, with no exclusion criteria, including 11 resection specimens and 9 endoscopic biopsies. All samples were initially reviewed on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained slides to confirm the histopathological diagnosis and ensure the presence of sufficient tumor tissue for reliable quantitative assessment. Subsequently, the corresponding paraffin blocks were selected, and new sections were obtained for immunohistochemistry (IHC) with both antibody clones (22C3 and 28-8). Positivity was independently evaluated by two expert pathologists and one third-year pathology resident. A combined positivity score for tumor cells was calculated for each antibody, and the mean of the three observers’ readings was used for quantitative analysis. Interobserver concordance for positivity or negativity categorization was 100% in all cases.

Statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 18 and JAMOVI version 2.3.28.0. T-tests and chi-square tests were applied to compare continuous and categorical variables, respectively. For non-normally distributed variables, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test and Fisher’s exact test were used to compare medians and categorical distributions, respectively.

A descriptive analysis was conducted to evaluate clinical characteristics, oncogenic addiction marker expression, and histological findings according to Lauren’s classification of GC. Additional variables included type of treatment received, overall survival (OS), and progression-free survival (PFS). Survival outcomes were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method and stratified by PD-L1 expression status. Associations between PD-L1 expression, measured by the combined positive score (CPS; positive if ≥ 1), and survival were assessed using Spearman’s correlation and logistic regression. Concordance between assays for PD-L1 detection was evaluated using the kappa index in cases with both antibody studies available.

Results

A total of 155 patients with complete pathological information were identified, with a mean age of 60 years (SD = 13.7). The majority were male (57.4%). Regarding pathological differentiation, 47% of tumors were poorly differentiated, 20.6% were moderately differentiated, and 32.2% were unspecified. Histological characterization according to Lauren’s classification was available in 25.8% of cases. Among these, 14.8% showed signet ring cells, predominantly in female patients, while 11% exhibited an intestinal-tubular pattern.

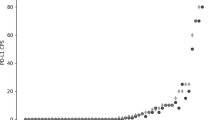

PD-L1 expression was evaluated in all patients and categorized using the Combined Positive Score (CPS), with a cutoff value of ≥ 1 considered positive. Two antibody clones were used: 28-8 (39.4% of cases) and 22C3 (60.6%). Among patients tested with the 28-8 clone, 34.4% were PD-L1 positive. CPS distribution in this group was 4.5% (CPS 1–4), 14.3% (CPS 5–9), and 28.6% (CPS ≥ 10).

In the cohort tested with the 22C3 clone, 28.7% were PD-L1 positive. Among these, 26% had a CPS 1–4, 18.5% had CPS 5–9, and 55.5% had CPS ≥ 10 (Table 1).

A total of 175 patients from a retrospective pathology database were included. These patients were either treated at the institutional cancer center or referred by their healthcare providers to other medical facilities for treatment.

Among patients with complete pathological information, 34 continued institutional follow-up and medical management, allowing for survival analysis. The mean age was 59 years (SD = 12.7), and 58.8% were male. Pathologically, 35.3% of tumors were poorly differentiated, 20.6% were moderately differentiated, and 44.1% were unspecified. Histological classification following Lauren’s criteria identified signet ring cells in 17.6% and an intestinal-tubular pattern in 3%; the remaining cases were not further classified (Table 2).

In this follow-up subgroup, PD-L1 expression was assessed exclusively using the 22C3 clone, with 35.3% of cases testing positive. Based on CPS values, 33.3% had CPS 1–4, 25% CPS 5–9, and 41.7% CPS ≥ 10.

Adjacent organ involvement was observed in 17.6% of cases and showed a significant association with PD-L1 expression (OR = 0.09; 95% CI: 0.009–0.9; p = 0.02). The peritoneum was the most frequently affected site (33.3%), followed by the cardioesophageal junction, cervical lymph nodes, round ligament, and gastrocolic ligament (each 16.6%).

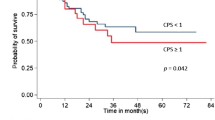

Twelve patients received immunotherapy (ipilimumab, nivolumab, or pembrolizumab), of whom 33.3% had metastatic PD-L1–positive gastric cancer. In this subgroup, the median overall survival (OS) was 14.5 months (IQR = 9–22.5). Figure 1 illustrates the Kaplan–Meier survival curves for gastric cancer patients by PD-L1 expression at 12, 36, and 60 months (HR = 2.26; 95% CI: 0.68–7.55; p = 0.18), though this result did not reach statistical significance.

Results from both Spearman’s correlation and logistic regression showed no statistically significant association between PD-L1 expression levels and clinical outcomes. Although Spearman’s correlation suggested a weak negative trend (ρ = −0.290; p = 0.097), it was not significant. Similarly, logistic regression revealed no meaningful association (β = −0.644; p = 0.394) between PD-L1 expression and survival probability.

Clone correlation

For the clone concordance analysis, an additional 20 patients were included. Each underwent immunopathological evaluation using both the 28-8 and 22C3 antibody clones to detect PD-L1 overexpression. The mean age of this subgroup was 54.2 years (SD = 24.3). Using the 28-8 clone, 60% of patients were PD-L1 positive, with CPS distributions of 25% (CPS 1–4), 16.7% (CPS 5–9), and 58.3% (CPS ≥ 10).

In contrast, with the 22C3 clone, 40% of cases were PD-L1 positive. Among these, 37.5% had CPS 1–4, and 62.5% had CPS ≥ 10; notably, no patients fell within the CPS 5–9 range.

Kappa concordance analysis showed agreement between assays in 61% of PD-L1–positive cases. However, the 28-8 clone identified a greater number of PD-L1–positive samples overall (Table 3).

Discussion

Currently, immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs)—including pembrolizumab, nivolumab, ipilimumab, durvalumab, and atezolizumab—are established therapeutic options for various advanced and metastatic tumors17. Multiple clinical studies have supported the use of these agents, such as the 22C3 pharmDx assay for pembrolizumab and the 28-8 assay for nivolumab18. The addition of ICIs to chemotherapy has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), with evidence showing a therapeutic benefit in patients with PD-L1–positive tumors, defined by a Combined Positive Score (CPS) ≥ 119,20,21.

Although prior studies have independently compared the performance of the 22C3 and 28-8 antibody clones to determine their interchangeability in detecting PD-L1 expression in gastric cancer (GC) (18), such analyses have not been conducted in Latin American populations. This is particularly important, as Latin American patients tend to present with gastric cancer at a younger age and more advanced stages, and are reported to have up to twice the risk of incidence and mortality compared to other ethnic groups22, likely due to distinct molecular profiles.

Across our analytical subgroups, gastric cancer was more frequently observed in men, representing 57% to 65% of diagnosed cases, with a higher prevalence of PD-L1 positivity. Kaplan-Meier survival curves revealed early mortality in PD-L1–positive patients (CPS > 1), with a 3-year survival rate of 34% compared to 67% in the PD-L1–negative subgroup. Although this finding did not reach statistical significance, it highlights a potentially important trend warranting further investigation. The convergence between the approaches of Spearman’s correlation and the logistic regression model—one nonparametric and the other multivariable—reinforces the interpretation that, in this cohort, the evaluated biomarker does not behave as a robust predictor of vital status or overall survival. Nevertheless, the negative direction observed in both analyses suggests a possible inverse relationship that could acquire clinical relevance in studies with larger sample sizes, adjusted models, or stratified analyses by treatment type or tumor characteristics.

Due to the small sample size, it was not possible to generate survival curves specifically for the subgroup treated with immunotherapy. However, a clinical benefit was observed, with a median overall survival (OS) of 14.5 months in patients who received immunotherapy versus 10 months in those who did not. The addition of ICIs to chemotherapy appears to confer clinical benefit in PD-L1–positive gastric cancer patients. Moreover, several clinical trials have shown that microsatellite instability (MSI) and PD-L1 expression are predictive of improved responses to immunotherapy23,24. Nonetheless, this study did not demonstrate a correlation between these two biomarkers.

To our knowledge, this is the first study of its kind conducted in a Latin American population. Our findings show that the 28-8 antibody clone demonstrated a higher sensitivity for detecting PD-L1 expression than the 22C3 clone, with an overall concordance rate of 61% between the two assays. Both clones identified a larger proportion of cases with CPS > 10—patients who have consistently shown the greatest clinical benefit from the addition of immunotherapy to chemotherapy in prior studies21,25,26. Notably, the 28-8 clone appeared more effective at identifying cases with lower CPS scores (1–4 or 5–9), whereas the 22C3 clone tended to identify positivity predominantly in the CPS > 10 range.

This study was not designed to compare the clinical efficacy of each ICI individually, nor to determine the optimal treatment strategy for specific patient subgroups. Treatment decisions in clinical practice are influenced by various factors, including drug availability, toxicity profiles, patient comorbidities, and treatment line. Consequently, further prospective studies are needed to clarify these aspects. Nonetheless, based on the present findings, it is reasonable to suggest that patients with PD-L1–positive gastric cancer may benefit from ICI-based therapy.

Several limitations must be acknowledged. The use of archived paraffin-embedded tissue samples for pathological and immunohistochemical analyses with the 28-8 and 22C3 antibodies limited the inclusion of additional patients. For future research, the use of freshly prepared paraffin blocks is recommended, as fresh samples provide better tissue integrity and more accurate assessment of PD-L1 expression, thereby enhancing the reliability of results and validity of conclusions. The small sample size and the unavailability of complete data weakened the statistical significance of the described findings; therefore, the results obtained should be interpreted with caution. The observed findings should be considered hypothesis-generating, and future research in this field is needed to validate these initial findings in Latin American populations and to determine their clinical implications in this specific population. Additionally, the limited sample size prevented further stratified statistical analyses by each subgroup.

Conclusion

The analysis of the study population indicates that the 28-8 clone identifies a greater number of patients with PD-L1 ligand expression compared to the 22C3 antibody. Nonetheless, both methods demonstrated concordance in 61% of the cases. Within the studied cohort, the subpopulation with a Combined Positive Score (CPS) greater than 10 was the most prevalent. However, due to the limited sample size, further research is warranted to confirm and validate these findings.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available, as they were obtained from medical records, laboratory results, and immunopathological studies that contain personal information of the patients involved. To protect patient confidentiality, the data cannot be openly shared. However, they are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- PD-L1:

-

Programmed cell death protein 1 ligand

- GC:

-

Gastric cancer

- IHC:

-

Immunohistochemical

- H&E:

-

Hematoxylin and eosin

- CPS:

-

Combined positive score

- MSI-H:

-

Microsatellite instability

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- ICIs:

-

Immune checkpoint inhibitors

- FDA:

-

Food and Drug Administration

References

Camargo, M. C. et al. Determinants of Epstein-Barr virus-positive gastric cancer: An international pooled analysis. Br. J. Cancer. 105(1), 38–43 (2011).

Machlowska, J., Baj, J., Sitarz, M., Maciejewski, R. & Sitarz, R. Gastric cancer: Epidemiology, risk factors, classification, genomic characteristics and treatment strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21(11) (2020).

Kim, J., Cho, Y. A., Choi, W. J. & Jeong, S. H. Gene-diet interactions in gastric cancer risk: A systematic review. World J. Gastroenterol. 20(28), 9600 (2014).

Arnold, M. et al. Global burden of 5 major types of gastrointestinal cancer. Gastroenterology 159(1), 335-349.e15 (2020).

Rawla, P. & Barsouk, A. Epidemiology of gastric cancer: Global trends, risk factors and prevention. Prz Gastroenterol. 14(1), 26–38 (2019).

Global Cancer Observatory. https://gco.iarc.fr/en (Accessed 22 Jul 2025).

Lordick, F. et al. Gastric cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 33(10), 1005–1020 (2022).

Correa, P. Gastric cancer. Overview. Gastroenterol. Clin. N. Am. 42(2), 211–217 (2013).

Fernández Montes, A. et al. Inmunoterapia en cáncer gástrico: revisión de la literatura. Revisiones en cáncer 34(1), 66–75 (2020).

Strati, A. et al. Targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 signaling pathway for cancer therapy: Focus on biomarkers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 26(3), 1235 (2025).

Oh, S. Y. et al. Soluble PD-L1 is a predictive and prognostic biomarker in advanced cancer patients who receive immune checkpoint blockade treatment. Sci. Rep. 11(1) (2021).

Patel, S. P. & Kurzrock, R. PD-L1 expression as a predictive biomarker in cancer immunotherapy. Mol. Cancer Ther. 14(4), 847–856 (2015).

Robert, C. et al. Comparative analysis of predictive biomarkers for PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in cancers: developments and challenges. Cancers 14(1), 109 (2021).

Smyth, E. C., Nilsson, M., Grabsch, H. I., van Grieken, N. C. & Lordick, F. Gastric cancer. Lancet 396(10251), 635–648 (2020).

Shin, J. & Park, Y. S. Unusual or uncommon histology of gastric cancer. J. Gastric Cancer. 24(1), 69–88 (2024).

Castri, F. et al. Gastroblastoma in old age. Histopathology 75(5), 778–782 (2019).

Yeong, J. et al. Choice of PD-L1 immunohistochemistry assay influences clinical eligibility for gastric cancer immunotherapy. Gastric Cancer 25(4), 741–750 (2022).

Ahn, S. & Kim, K. M. PD-L1 expression in gastric cancer: interchangeability of 22C3 and 28–8 pharmDx assays for responses to immunotherapy. Mod. Pathol. 34(9), 1719–1727 (2021).

Reck, M. et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for PD-L1–positive non–small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 375(19), 1823–1833 (2016).

De Castro, G. et al. Five-year outcomes with pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy as first-line therapy in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer and programmed death ligand-1 tumor proportion score ≥ 1% in the KEYNOTE-042 study. J. Clin. Oncol. 41(11), 1986–1991 (2023).

Janjigian, Y. Y. et al. First-line nivolumab plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for advanced gastric, gastro-oesophageal junction, and oesophageal adenocarcinoma (CheckMate 649): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet 398(10294), 27–40 (2021).

Wang, S. C. et al. Hispanic/Latino patients with gastric adenocarcinoma have distinct molecular profiles including a high rate of germline CDH1 variants. Cancer Res. 80(11), 2114–2124 (2020).

Negrete-Tobar, G. et al. Microsatellite instability and gastric cancer. Revista Colombiana de Cirugia. 36(1), 120–131 (2021).

Zafon, L. C. Cancer Immunotherapy and endocrinology: A new opportunity for multidisciplinary collaboration. Endocrinol. Diabetes Nutr. 64(9), 461–463 (2017).

Sun, J. M. et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for first-line treatment of advanced oesophageal cancer (KEYNOTE-590): a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet 398(10302), 759–771 (2021).

Doki, Y. et al. nivolumab combination therapy in advanced esophageal squamous-cell carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 386(5), 449–462 (2022).

Funding

The development and writing of this study were sponsored by Bristol-Myers Squibb. However, the results obtained were not influenced.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.F.B.R and J.A.M wrote the main manuscript. A.F.B.R conduct the statistical analysis. A.F.B.R prepared all the figures and tables. L.C.Z and R.L conducted the immunohistochemical studies.All the authors collected the data. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The research was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and complied with all applicable institutional, national, and international guidelines and regulations for research involving human subjects. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Hospital Universitario Fundación Santa Fe de Bogotá, under communication CCEI-15797-2023 dated October 24, 2023. The IRB determined that the study met the criteria for exemption from informed consent due to its retrospective and non-interventional design.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cantor, E.A., Bejarano-Ramírez, A.F., Zambrano, L.C. et al. PD-L1 expression in gastric cancer assessed with antibodies 28-8 and 22C3. Sci Rep 15, 41204 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25055-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25055-8