Abstract

Silicon germanium (Si1 − xGex) has emerged as a mainstream nanoelectronic material and as such its defect processes and energetics are technologically important. In semiconductor alloys the interaction of intrinsic point defects such as vacancies with dopant atoms are critical for the physical properties of the material and impact nanoelectronic device performance. Gallium (Ga) is a p-type dopant in elemental and alloys group IV semiconductors and its interaction with vacancies can impact its diffusion and electronic properties. The gallium-vacancy (GaV) defect pairs are not thoroughly investigated in Si1 − xGex random semiconductor alloys. Here we employ hybrid density functional theory (DFT) to study the electronic properties and binding energies in seven compositions of Si1 − xGex. The prediction of the prevalent GaV pair in each composition is hindered by the large number of local environments that impact in turn the energetics of the defect pairs. To overcome this, we applied the special quasirandom structures (SQS) method and considered the lowest binding energy GaV pairs to the favourable one for every respective composition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The use of alternative to SiO2 high dielectric (high-k) constant materials1,2,3 has allowed the use of higher mobility semiconductor materials (as compared to silicon (Si)) for nanoelectronic applications including Si1 − xGex and germanium (Ge)4,5,6,7,8,9.

Gallium (Ga) is a group III element and it typically acts as an acceptor atom in Si, Si1 − xGex and Ge and as such it is a typical dopant alongside boron (B) and indium (In) in p-type regions of nanoelectronic devices10,11,12. The properties of Ga dopants in group IV elemental (i.e. Si or Ge) semiconductors have been thoroughly investigated both from an experimental and theoretical perspective13,14,15,16,17,18. Conversely, there is limited information for the interaction of Ga with intrinsic defects in binary group IV semiconductors (i.e. Si1 − xGex), particularly when considering high Ge-content solid solutions.

From a theoretical viewpoint it is not straightforward to employ DFT calculations to study even simple defect clusters in random alloys and solid solutions such as Si1 − xGex. This is because the energetics of the defect clusters will depend upon the nearest neighbour environments and to calculate all the possible configurations in a large supercell that will rigorously describe these local environments is practically intractable. Conversely, the SQS method19 allows the reproduction of the vast local environments that are present in solid solutions concurrently reducing not only the number of calculations but also the supercell size as it has been demonstrated in previous studies including binary (Si1 − xGex, Sn1 − xGex) and ternary (Si1 − x−yGexSny) group IV random alloys20,21,22,23. These methods can make computationally tractable the investigation of more complicated defects such as the vacancy-gallium configurations in Si1 − xGex.

Here we employ DFT simulations to identify the energetically favourable vacancy-gallium configurations in Si1 − xGex. We focus on the study of the influence of nearest neighbour environments on the vacancy-gallium binding energies and the electronic structure.

Computational methods

We calculated the binding energies of Ga substitutional atoms with vacancies in Si1 − xGex using the plane wave DFT code CASTEP24,25. For each of the seven compositions of Si1 − xGex (x = 0.125, 0.25, 0.375, 0.5, 0.625, 0.75, 0.875) we performed 128 calculations covering all the unique distinct GaV pairs, 32 calculations for all the different Ga sites, 32 calculations for all the unique different vacancy sites and one calculation for the bulk structure (i.e. a total of 1351 calculations). The vast number of DFT calculations confined the binding energy calculations to 64-atomic site supercell that were formed by two 32-atoms SQS cells the efficacy of which was discussed in previous work26. Correlation and exchange interactions were described by employing the corrected density functional of Perdew, Burke, and Ernzerhof (PBE)27, the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) was used with ultrasoft pseudopotentials28. For the plane wave basis the level of convergence of the atomic energies was set to 0.000544 eV/atom in conjunction with a 2 × 2 × 2 Monkhorst-Pack (MP)29 k-point grid. To automate the setup of calculations we used the Defects and Impurities Setup (DIMS) tool30, whereas the visualizations were generated using the VESTA software (version 3)31.

The binding energy (\(\:{\text{E}}_{\text{b}}\left(\text{G}\text{a}\text{V}\right))\:\)of a GaV defect pair in Si1 − xGex was calculated via the following relation:

where \(\:\text{E}[\text{G}\text{a}\text{V}{]}_{\text{s}\text{u}\text{p}\text{e}\text{r}\text{c}\text{e}\text{l}\text{l}}\) is the total energy of a GaV defect in the supercell of Si1 − xGex, \(\:\text{E}[\text{S}\text{i}\text{G}\text{e}{]}_{\text{s}\text{u}\text{p}\text{e}\text{r}\text{c}\text{e}\text{l}\text{l}}\) is the total energy of the undoped supercell, \(\:\text{E}[\text{G}\text{a}{]}_{\text{s}\text{u}\text{p}\text{e}\text{r}\text{c}\text{e}\text{l}\text{l}}\) is the total energy of a single Ga atom substitutionally doped in the supercell of Si1 − xGex and \(\:\text{E}[\text{V}{]}_{\text{s}\text{u}\text{p}\text{e}\text{r}\text{c}\text{e}\text{l}\text{l}}\) is the total energy of a supercell containing a single vacancy.

CASTEP is known to require more effort to converge hybrid simulations (k-points, cutoffs, exact exchange), which can consume computational resources for systems with large atoms. This is highly improved using the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP)32,33. Due to the high computational resources required for hybrid simulations we have used VASP to simulate the partial density of states (PDOS) The projector augmented wave (PAW) method was employed as the pseudopotential approach to separate the chemically active valence electrons from the core electrons34. The PBE of the GGA is known to underestimate the electronic properties of most semiconductors. The Heyd, Scuseria, and Ernzerhof (HSE) hybrid functional, which combines elements of both Hartree–Fock and PBE was used as the exchange correlation35. A 0.25% mixing parameter and a screening parameter of 0.2 Å−1 was used for the HSE. The initial relaxed geometry from the previous relaxation was used for the PDOS simulation.

Results and discussion

Modelling silicon germanium

SQS can be described as designed small-unit-cell periodic structures, which can adequately mimic the nearest neighbour pair and multisite correlation functions of the corresponding random substitutional alloys19,20. In practical terms, as they are essentially atomistic models there is a distribution of local environments that would be present in the real random alloys. In the Si1 − xGex lattice the Si or Ge atoms are surrounded by SinGe4−n coordination shells (where n = 0 to 4) and these are the local environments around the GaV defect. Previous studies have showed that the SQS approach is appropriate to describe local environments in Si1 − xGex36,37,38. This is important as it is established that the local environments will significantly influence the dopant-defect interactions in Si1 − xGex38,39,40.

GaV defect

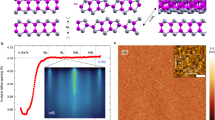

The seven 32-atom SQS Si1 − xGex cells used were derived in previous work (refer to Fig. 1 in Ref26. Here we formed 64-atomic site supercells by using two 32-atom cells. Figure 1 represents the lowest binding energy GaV defects and their nearest neighbour atoms in the different Si1 − xGex alloys considered here. For all the compositions considered here the GaV pair gained energy by at least one Ge atom being at a nearest neighbour position to the vacancy (refer to Fig. 1). This is a common feature in dopant-vacancy pairs in Si1 − xGex as it was previously demonstrated for the E-centres and NV defect pairs36,38.

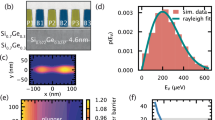

Figure 2 reports the calculated lowest and average binding energies of GaV defects with respect to the Ge content in Si1 − xGex. From this figure it is clear that there is a deviation from linearity of the lowest energy binding energies, but average binding energies are closer to linearity. In the same figure the observed range of binding energies can also be seen providing further feedback on the importance of the local atomic environment on the energetics of GaV defects. The deviation from linearity is a feature of these group IV alloys (and also III-V alloys41. In particular, it was previously shown that the binding energies of E-centres (i.e. PV and AsV), NV pairs and the diffusion properties of species facilitated by the vacancy mechanism deviate from linearity in Si1 − xGex (for example4,6,7,36,38 and references therein) and this is consistent with the GaV binding energies considered here. Of particular importance is the experimental work by Kube et al.7. investigating self-diffusion in Si1 − xGex as it considered systematically an extensive compositional (x = 0.0, 0.05, 0.25, 0.45 and 0.70) and temperature (963–1543 K) indicating that there is a deviation from linearity. The evidence from experimental and theoretical work4,6,7,36,38 on the subtle deviations irrespective of the defect issue considered point out to that it is due to the bulk material. In a previous study, Saltas et al.41. considered the validity that the deviation from linearity (Vegard’s law) in Si1 − xGex is due to inherent bulk properties. In particular, Saltas et al.42. used the cBΩ thermodynamic to study the impact of temperature and composition on self-diffusion in Si1 − xGex. Saltas et al.42. concluded that the deviations from linear behaviour can be traced to the diversification of the bulk properties of Si and Ge, and such as it is an inherent property of the host material, Si1 − xGex.

To summarize what can be derived from Figs. 1 and 2 is (a) in the most energetically favourable configurations the vacant site has always a Ge atom at a nearest neighbour site and (b) there is a significant impact of local environments on the binding energies of the GaV defect.

Figure 3 displays the partial density of states (PDOS) of the pristine Ge and Si, as well as that of the single Ge or Si vacancy in Ge or Si, respectively. Figure 4 displays the PDOS plots for Ga-doped Si1 − xGex alloys at a range of concentrations (x = 0.125, 0.25, 0.375, 0.5, 0.625, 0.75, 0.875) and GaV in Si and Ge. The participating valence orbitals of the host atoms (Si and Ge) and those of the impurity atom (Ga) were plotted for the PDOS. In other words, the atoms interacting with the dopants in the presence of a vacancy were considered. However, irrespective of the Si or Ge atoms chosen, each PDOS does not significantly differ from that of the atom nearest to the dopant and vacancy defect.

The PDOS of the pristine Ge and Si suggest the absence of mid gap states. Furthermore, the Fermi level is pinned to the valence band maximum (VBM) for the Si and few eV away from the VBM for Ge. In contrast to the pristine Ge and Si, the Fermi energy of the Si1 − xGex alloy shifted away from the VBM. When the concentration of Ge is low, the Fermi level of the Si1 − xGex alloy mimics that of the Si-vacancy. However, when the concentration of Ge is elevated, the Fermi level of the Si1 − xGex alloy mimics that of the Ge vacancy. The GaV in pure Si induced mid gap states, however, in Ge it is metallic with many ground states filling up band gap. The introduction of Ga dopant, while interacting with vacancy in the Si1 − xGex alloy leads to a significant reduction in the band gap for some concentration levels. As shown in Fig. 4, numerous mid-gap states are induced within the Si1 − xGex alloy due to the presence of Ga interacting with vacancy in the host system. The extent of this impact varies markedly with dopant concentration. At all doping levels, Ga dopant while interacting with vacancy introduces mid-gap states on both sides of the Fermi energy. These states are primarily contributed by the p-orbitals of the Ga atoms, in contrast to the s- and p-orbitals of the Si atom, which contribute less prominently. Furthermore, the p orbitals of Ge play a large role in the formation of these mid-gap states. The presence of mid-gap states significantly narrows the wide band gap of the pristine Si1 − xGex alloy, this is in contrast to the pristine Si. In more severe cases, such as for x = 0.25 (refer to Fig. 4, the Si0.75Ge0.25 alloy is transformed into a semimetal. Strong orbital hybridizations are observed across all concentration levels, arising mainly from the p orbitals of both Ge and Ga, with additional contributions from the s orbitals of Ge. While most concentrations show negligible spin polarization, the x = 0.25 concentration exhibits pronounced spin polarization effects. This suggests that Ga interacting with vacancy doping at this level may be useful for developing spin-dependent electronic devices. However, it is worth noting that at this concentration, the Si0.75Ge0.25 alloy transitions to a metallic state. Each doping level results in different electronic behavior. Interestingly, depending on the concentration, the Ga-doped with vacancy in Si1 − xGex alloy can exhibit p-type semiconductor characteristics, where the valence band lies above the Fermi level, as seen in Fig. 4. Across all concentrations studied, narrow peaks in the PDOS plots indicate highly localized electronic states in real space. These localized states suggest the presence of flat bands, which correspond to low group velocities and, consequently, reduced charge carrier mobility. For example, Ga dopant interacting with vacancy in Si1 − xGex create highly localized states, which can influence optical transitions, affect the material’s color. Overall, the PDOS analysis of Ga-doped coupled with vacancy in Si1 − xGex reveals that the defect can act as a trap for charge carriers, particularly holes, or, in more detrimental cases, degrade device performance. However, such doping can enable new functionalities, such as enhanced optical absorption, depending on the concentration.

Conclusion

In the present study we employed systematic DFT calculations and state of the art hybrid DFT to investigate GaV defects in a range of Si1 − xGex compositions. It is calculated that in the most energetically favourable configurations the vacant site has always a Ge atom at a nearest neighbour site. What is also observed is that here is a significant impact of local environments on the binding energies of the GaV defect and this is reflected upon the range of the binding energies. Importantly, for all the Si1 − xGex compositions considered here the GaV defect pairs are bound. The Ga dopant interacting with vacancy induced mid gap states in Si1 − xGex, thus, significantly reduces the band gap. At x = 0.25 (refer to Fig. 1(b)), the alloy transitions into a semimetal with notable spin polarization. Depending on the doping level, the material may exhibit p-type behaviour or metallicity.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Kim, H., Chui, C. O., Saraswat, K. C. & McIntyre, P. C. Local epitaxial growth of ZrO2 on Ge(100) substrates by atomic layer epitaxy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 83, 2647 (2003).

Kita, K. et al. Direct evidence of geo volatilization from geo2/Ge and impact of its suppression on geo2/Ge metal-insulator-semiconductor characteristics. Jpn J. Appl. Phys. 47, 2349 (2008).

Boscherini, F., D’Acapito, F., Galata, S. F., Tsoutsou, D. & Dimoulas, A. Atomic scale mechanism for the Ge-induced stabilization of the tetragonal, very high-κ, phase of ZrO2. Appl. Phys. Lett. 99, 121909 (2011).

Zangenberg, N. R., Hansen, L. & Fage-Pedersen, J. Nylandsted Larsen, A. Ge Self-Diffusion in Epitaxial Si1 – xGex Layers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 125901 (2001).

Chroneos, A. et al. Implantation and diffusion of phosphorous in germanium. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Proc. 9, 640–643 (2006).

Kilpeläinen, S. et al. Stabilization of Ge-rich defect complexes originating from E centers in Si1 – xGex:P. Phys. Rev. B. 81, 132103 (2010).

Kube, R. et al. Composition dependence of Si and Ge diffusion in relaxed Si1 – xGex alloys. J. Appl. Phys. 107, 073520 (2010).

Chroneos, A. & Bracht, H. Diffusion of n-type dopants in germanium. Appl. Phys. Rev. 1, 011301 (2014).

Igumbor, E. et al. Electronic properties and defect levels induced by n/p-type defect-complexes in ge. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Proc. 150, 106906 (2022).

Kube, R., Bracht, H., Chroneos, A., Posselt, M. & Schmidt, B. Intrinsic and extrinsic diffusion of indium in germanium. J. Appl. Phys. 106, 063534 (2009).

Feng, R. et al. Electrical and structural properties of In-implanted Si1 – xGex alloys. J. Appl. Phys. 119, 025709 (2016).

Kipke, F., Südkamp, Prüssing, J. K., Bougeard, D. & Bracht, H. Diffusion of Boron in germanium at 800–900°C revisited. J. Appl. Phys. 127, 025703 (2020).

Riihimäki, I., Virtanen, A., Kettunen, H., Pusa, P. & Räisänen, J. Diffusion properties of Ga in Si1 – xGex alloys. J. Appl. Phys. 104, 123510 (2008).

Lebegue, S. Electronic structure of superconducting gallium-doped germanium from ab-initio calculations. Phys. Stat. Sol Rapid Res. Lett. 3, 224–226 (2009).

Fiedler, J. et al. High-fluence Ga-implanted silicon -The effect of annealing and cover layers. J. Appl. Phys. 116, 024502 (2014).

Prucnal, S. et al. Superconductivity in single-crystalline aluminum- and gallium-hyperdoped germanium. Phys. Rev. Mater. 3, 054802 (2019).

Kuganathan, N., Bracht, H., Davazoglou, K., Kipke, F. & Chroneos, A. Impact of oxygen on gallium doped germanium. AIP Adv. 11, 065122 (2021).

Cheng, Y. et al. Superconductivity in Ga-doped SixGe1–x alloys through ion implantation and flash-lamp annealing. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 40, 065009 (2025).

Zunger, A., Wei, S. H., Ferreira, L. G. & Bernard, J. E. Special quasirandom structures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 65, 353–356 (1990).

Jiang, C., Wolverton, C., Sofo, J., Chen, L. Q. & Liu, Z. K. First-principles study of binary Bcc alloys using special quasirandom structures. Phys. Rev. B. 69, 214202 (2004).

Chroneos, A., Jiang, C., Grimes, R. W., Schwingenschlögl, U. & Bracht, H. Defect interactions in Sn1 – xGex random alloys. Appl. Phys. Lett. 94, 252104 (2009).

Jiang, C., Stanek, C. R., Sickafus, K. E. & Uberuaga, B. P. First-principles prediction of disordering tendencies in pyrochlore oxides. Phys. Rev. B. 79, 104203 (2009).

Murphy, S. T., Chroneos, A., Grimes, R. W., Jiang, C. & Schwingenschlögl, U. Phase stability and the arsenic vacancy defect in InxGa1–xAs. Phys. Rev. B. 84, 184108 (2011).

Payne, M. C., Teter, M. P., Allan, D. C., Arias, T. A. & Joannopoulos, J. D. Iterative minimization techniques for Ab initio total-energy calculations: molecular dynamics and conjugate gradients. Rev. Mod. Phys. 64, 1045–1097 (1992).

Segall, M. D. et al. First-principles simulation: ideas, illustrations and the CASTEP code. J. Phys. : Condens. Matter. 14, 2717 (2002).

Chroneos, A., Jiang, C., Grimes, R. W. & Schwingenschlögl, U. Special quasirandom structures for binary/ternary group IV random alloys. Chem. Phys. Lett. 493, 97–102 (2010).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Vanderbilt, D. Soft self-consistent pseudopotentials in a generalized eigenvalue formalism. Phys. Rev. B. 41, 7892–7895 (1990).

Monkhorst, H. J. & Pack, J. D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B. 13, 5188–5192 (1976).

Christopoulos, S. R. G., Papadopoulou, K. A., Konios, A. & Parfitt, D. DIMS: A tool for setting up defects and impurities CASTEP calculations. Comp. Mater. Sci. 202, 110976 (2022).

Momma, K. & Izumi, F. VESTA3 for three-dimensional visualization of crystal, volumetric and morphology data. J. Appl. Cryst. 44, 1272–1276 (2011).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for Ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B. 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Hutchinson, M. & Widom, M. VASP on a GPU: application to exact-exchange calculations of the stability of elemental Boron. Comp. Phys. Commun. 183 (7), 1422–1426 (2012).

Blochl, P. E. Projector augmented wave method. Phys. Rev. B. 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Heyd, J., Scuseria, G. E. & Ernzerhof, M. Hybrid functionals based on a screened coulomb potential. J. Chem. Phys. 118, 8207 (2003).

Christopoulos, S. R. G., Kuganathan, N. & Chroneos, A. Impact of local composition on the energetics of E-centres in Si1 – xGex alloys. Sci. Rep. 9, 10849 (2019).

Christopoulos, S. R. G., Kuganathan, N. & Chroneos, A. Electronegativity and doping in Si1 – xGex alloys. Sci. Rep. 10, 7459 (2020).

Christopoulos, S. R. G., Kuganathan, N., Sgourou, E., Londos, C. & Chroneos, A. The nitrogen-vacancy defect in Si1 – xGex alloys. Sci. Rep. 15, 10416 (2025).

Laitinen, P., Riihimäki, I. & Räisänen, J. the ISOLDE Collaboration, Arsenic diffusion in relaxed Si1 – xGex. Phys. Rev. B. 68, 155209 (2003).

Chroneos, A., Bracht, H., Jiang, C., Uberuaga, B. P. & Grimes, R. W. Nonlinear stability of E centers in Si1 – xGex: Electronic structure calculations. Phys. Rev. B. 78, 195201 (2008).

Murphy, S. T., Chroneos, A., Jiang, C., Schwingenschlögl, U. & Grimes, R. W. Deviations from vegard’s law in ternary III-V alloys. Phys. Rev. B. 82, 073201 (2010).

Saltas, V., Chroneos, A. & Vallianatos, F. Composition and temperature dependence of self-diffusion in Si1 – xGex alloys. Sci. Rep. 7, 1374 (2017).

Acknowledgements

Open access fee was paid from the Imperial College London Open Access Fund.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The contributions of the authors to this research are as follows: Authors S.-R.G.C and E.I. conducted the DFT calculations. A.C., E.I. and E.M. wrote the manuscript, and contributed to the conceptualization and design of the study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Christopoulos, SR.G., Igumbor, E., Mapasha, E. et al. Electronic structure calculations on gallium-vacancy defects in Si1-xGex. Sci Rep 15, 41265 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25115-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25115-z