Abstract

Durum wheat is highly susceptible to fungal pathogens, which poses a significant challenge in its production. The aim of this study was to evaluate the health status of European spring cultivars of durum wheat grown in southern and northern Poland, to identify T. durum genes that confer resistance to Fusarium graminearum, Blumeria graminis, and Zymoseptoria tritici, and to select cultivars that are most resistant to changing environmental conditions in the temperate climate of Central Europe. Plant health was assessed in three-year field experiments, and the tested cultivars’ sensitivity to inoculation with F. graminearum and accumulation of group B trichothecenes was analyzed in a greenhouse experiment. Resistance alleles were identified, and wheat plants’ susceptibility to Fusarium head blight (FHB), Septoria tritici blotch (STB), and powdery mildew (PM) was determined in the PCR assay. In 2018–2019, symptoms of FHB were noted sporadically under field conditions, whereas in 2020, the disease was endemic in both experimental sites. In 2020, symptoms of Fusarium leaf blight (FLB) were observed in southern Poland, and symptoms of STB were noted in the northern part of the country. The severity of PM was low, and disease symptoms were observed mainly on lower leaves in all cultivars. Fhb2, Stb1, Stb2, Stb3, Pm36, and Pm41 alleles were identified in the tested cultivars. Cultivar IS Duragold grown in the greenhouse was least susceptible to primary infection by F. graminearum and the growth of fungal hyphae on the rachis. After inoculation, DON was accumulated in spikelets in all cultivars, in particular Duramant (1582 µg/kg) and Durasol (1455 µg/kg). Almost all of the tested cultivars were susceptible or very susceptible to FHB and STB, with the exception of IS Duragold and IS Duranegra which proved to be moderately susceptible. Susceptibility to FHB was inversely correlated with plant height and positively correlated with spike density. Tall cultivars with moderately dense spikes and a shorter flowering period were less susceptible to FHB.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Durum wheat (Triticum turgidum L. subsp. durum (Desf.) van Slageren) is cultivated on around 13.5 million ha of land worldwide, which accounts for 6.2% of total area under wheat1. In the 2022–2023 season, the global production of durum wheat grain was estimated at 33.9 million tons1. In Europe, durum wheat is grown mainly in the Mediterranean Region, and it is also produced in North America, Australia, Northern Africa, Kazakhstan, and Turkey. Durum wheat grain is used mainly in the production of pasta, bulgur, and couscous, and it is widely consumed in many countries2,3,4. Heat and drought stress poses a significant risk for durum wheat production in many regions, including the Mediterranean Region4. In an era of rapid climate change, durum wheat has attracted considerable interest in Central Europe, including in Poland, where this cereal species is grown on more than 2,500 ha of land5,6. However, the introduction of durum wheat to new areas increases the risk of infections caused by virulent polyphagous pathogens of cereals.

Fungi of the genus Fusarium pose the greatest threat in cereal production. These pathogens infect cereal plants during the entire growing season and cause various diseases, including Fusarium head blight (FHB)7. This disease is caused by more than 20 species and subspecies of the genus Fusarium8, and Fusarium graminearum Schwabe (teleomorph Gibberella zeae Schwabe) is the predominant pathogen of wheat in many regions of Europe9, Asia8, and North America10. This fungus produces numerous mycotoxins that can cause gastrointestinal diseases, skin infections, and endocrine disorders in mammals11,12. Fusarium graminearum is a highly aggressive pathogen that poses the greatest threat to wheat during anthesis13,14,15. The prevalence of FHB is largely determined by wheat cultivars’ susceptibility to infection. Resistance to Fusarium spp. is a polygenic trait that is conditioned by quantitative trait loci (QTL), and symptoms of infection are strongly modified by weather. Five types of resistance associated with the physiological and biochemical properties of wheat plants have been described16,17. Type 1 resistance denotes resistance to primary infection, whereas type 2 resistance prevents the fungal pathogen from spreading along the rachis, and it is associated with the number of shriveled spikelets in a spike18. Type 3 resistance reduces the accumulation of DON in grain; type 4 resistance prevents grain infection, and type 5 resistance is associated with lower yield loss. A cultivar’s susceptibility to infection should be evaluated based on factors that affect passive immunity, including plant height, spike density, and the date and duration of anthesis, which influence the rate at which the disease spreads19.

Recent research on wheat’s genetic predisposition to FHB has focused on Fhb1, Fhb2, and Qfhs.ifa-5 A genes derived from cultivar (cv.) Sumai 3, whose QTL pyramiding effects are associated with type 2 resistance19,20,21,22. Several authors have confirmed enhanced type 3 resistance when Fhb1 locus was pyramided with QFhs.nau-2DL19,23,24. The Fhb1 gene on chromosome 3BS was frequently identified in bread wheat genomes18. The Fhb1 locus, previously reported as Qfhs.ndsu-3BS, was mapped as a single Mendelian gene in a high-resolution mapping population19,25. Fhb1 encodes the glycosyltransferase enzyme that transforms DON into the less toxic DON-3-O-glucoside19,26.

Septoria tritici blotch (STB) caused by the Zymoseptoria tritici (Roberge ex Desm.) Quaedvl. & Crous fungus is one of the most devastating wheat diseases in the world27,28. This disease affects all regions of Central Europe27, the Mediterranean Region28,29, and Asia30 where durum wheat is cultivated. Epidemics occur in wet years, and the Z. tritici hemibiotrophic pathogen is characterized by a long biotrophic stage in plant tissues31. Relatively little is known about the biology of Z. tritici development in durum wheat. A recent study conducted in Tunisia demonstrated that this pathogen can produce generative fruiting bodies (pseudothecia) as well as many generations of conidiospores in pycnidia32. In durum wheat, resistance to Z. tritici infection is conferred by 22 Stb major genes (qualitative resistance is strong, with a large effect) and 167 genome regions carrying QTL33,34,35. Durum wheat is not widely grown in Central Europe, and the Polish winter cultivars of Ceres, SM Metis, SM Tetyda, and SM Eris are relatively susceptible to Z. tritici. Further research is needed to determine the resistance of European cultivars to this pathogen36,37.

Symptoms of powdery mildew (PM) (Blumeria graminis DC. Speer f. sp. tritici) were reported in all regions of durum wheat cultivation38,39. This biotrophic pathogen colonizes leaf surfaces and significantly decreases yields. Most durum wheat cultivars are susceptible to PM39. Approximately 100 genes encoding resistance to PM in wheat have been identified and mapped to specific chromosomes or chromosome arms39,40,41. Five of these loci (Pm1, Pm3, Pm4, Pm5, and Pm8) have more than one allele conferring resistance42. Several genes encoding resistance to PM have been identified in durum wheat, including Mld, Pm 36, Pm3h, PmDR147, and Pm68. Mld is a recessive gene on chromosome 4B, and it has been combined with other PM resistance genes, such as Pm2, and used for wheat breeding39,40,43. Pm3h, a dominant resistance gene located on chromosome 1AS, probably originated from an Ethiopian durum wheat accession39,44. PmDR147 is yet another dominant gene that has been identified on 2AL in durum wheat accession DR14745. He et al.39 identified Pm68, a new PM resistance gene, on the terminal part of chromosome 2BS of Greek durum wheat landrace TRI 1796.

The normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) is widely used to assess the nutritional status of durum wheat plants46,47 and their performance in response to elevated CO2 levels48. The NDVI is also an indicator of chlorophyll content, plant vigor, and productivity47,49. This parameter is used mainly in precision agriculture to determine the nutritional status of plants, and it provides farmers with useful information about the nitrogen requirements of crops. Lower values of NDVI indicate that higher rates of N fertilizer are needed to maximize yields in areas characterized by lower productivity, whereas higher values of NDVI suggest that N fertilizer rates should be reduced to achieve consistent grain yields46. This approach delivers environmental benefits and increases crop profitability. In the work of Kizilgeci et al.47, durum wheat cv. Sena was characterized by significantly lower NDVI than cv. Svevo in the milky ripe stage, but grain yields were considerably higher in cv. Sena than in cv. Svevo under field conditions.

This article presents the results of field experiments which were conducted in 2018–2020 with the aim of: (I) evaluating the health status of European spring cultivars of durum wheat grown in southern and northern Poland, (II) identifying T. durum genes that confer resistance to infections caused by F. graminearum, B. graminis, and Z. tritici, and (III) selecting cultivars that are most resistant to pathogens under different environmental conditions in the temperate climate of Central Europe.

Materials and methods

Field experiment, sites, and weather conditions

In 2018–2020, field experiments were established in north-eastern (Bałcyny, DMS: 53° 35’ 49’’ N 19° 51’ 15’’ E) and south-eastern (Niedrzwica Kościelna, DMS 51° 5’ 28’’ N 22° 21’ 55’’ E) Poland. The soils in each experimental site were suitable for durum wheat cultivation and had similar properties. Mean daily temperatures during the growing season (March to August) differed significantly between the experimental sites. In 2018, 2019, and 2020, mean daily temperatures were determined at 12.3 °C, 12.3 °C, and 10.7 °C in Bałcyny, and at 12.3 °C, 11.6 °C, and 11.5 °C in Niedrzwica Kościelna, respectively (Fig. 1). Total precipitation in successive growing seasons reached 330.7, 370.6, and 336.7 mm in Bałcyny, and 266.5, 288.1, and 332.5 mm in Niedrzwica Kościelna, respectively. In 2019 and 2020, April was a very dry month in Bałcyny. In Niedrzwica Kościelna, precipitation levels were very high in the last ten days of May and in June of 2020. Considerable fluctuations in temperature and uneven rainfall distribution were noted in both experimental sites.

Both experiments had a split-plot design with two replications. Harvested plot area was 15 m2. In each year of the study, durum wheat was sown on the last ten days of March in Niedrzwica Kościelna and in the first ten days of April in Bałcyny. The seeding rate was 240–270 kg/ha, depending on the thousand-grain weight and the germination capacity of grain. Weeds were controlled with florasulam plus 2,4-D (Dow AgroScience/Corteva Agriscience, Poland) on the dates and at the rates recommended by the manufacturer. The trinexapac ethyl growth regulator (Syngenta, Poland) was applied according to the producer’s instructions. Phosphorus and potassium fertilizers were applied before sowing (P2O5 – 60 kg/ha, K2O – 100 kg/ha). Nitrogen fertilizers were split into three portions: 40 kg/ha applied before sowing, and 60 and 40 kg/ha top dressed during stem elongation (BBCH 30)50 and heading (BBCH 51). The spring cultivars of durum wheat that were analyzed in 2018–2020 are characterized in Table 1.

Evaluation of the health status of field-grown durum wheat plants

The health status of 14 durum wheat cultivars was assessed in field experiments established in two locations in Poland. The health status of flag leaves and spikes was evaluated in the early milk stage (BBCH 73) according to the guidelines of the European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization51, by examining 100 infected plant organs. The number of infected flag leaves and spikes was determined, and the severity of the infection was expressed as the percentage of infected leaf/spike area.

Greenhouse experiment and spike inoculation with F. graminearum

Eight durum wheat cultivars (Duralis, Durasol, Duramant, IS Duragold, IS Duranegra, Duramonte, Floradur, and Tamadur), selected as the best candidates for cultivation in Poland, were grown in a greenhouse experiment. Grain was sown into pots with a diameter of 25 cm and a height of 30 cm, filled with horticultural soil. During and after germination, temperature was maintained at 23/19°C (± 1 °C) (day/night) with a 16/8 h (day/night) photoperiod. Relative humidity during plant growth was 80%. NPK fertilizer (Azofoska, Poland, N/P2O5/K2O 13.6/6.4/19.1%) was applied three times at 2 g per pot, and the Corbel® 750EC fungicide (fenpropimorph, BASF, Poland) was applied at the beginning of tillering (BBCH 21) and in the first node stage (BBCH 31) to protect leaves against infection caused by Blumeria graminis ssp. tritici.

Spikes were inoculated with F. graminearum strain Fg3 (15ADON genotype) which had been isolated from durum wheat grain and deposited in the authors’ collection. The pathogen was identified with the use of molecular methods described by Duba et al.17. A macroconidia suspension was prepared with the use of liquid agar and carboxymethyl cellulose (CMS) according to a previously described procedure52. Fungal conidia were obtained from 7-day-old F. graminearum colonies with the use of an inoculation loop, and 200 µL aliquots of a suspension containing 106 conidia in 1 cm3 were added to the liquid medium. Flasks were shaken on a shaker Table (120 rpm; DLab, Poland) in darkness, at a temperature of 27 °C (Pol-Eco, Poland), for four days. Conidia were centrifuged (4500 rpm, 10 min, Eppendorf, Poland) and rinsed with sterile water. Rinsed conidia were diluted with sterile water to 16 × 106 in 1 cm3. The density of the conidia suspension was determined under an optical microscope (Nikon Eclipse E200, Japan) with a Thoma 50 counting chamber (Marienfeld, Germany).

The second spikelet from the top was inoculated at the beginning of anthesis (BBCH 61). The suspension of F. graminearum conidia (10 µL) was introduced between the lemma and palea at the base of each floret with the use of a micropipette (Ovation, VistaLab Technologies, USA). Plants inoculated with F. graminearum were sprayed with water for 16 h, at 30-minute intervals, with the use of an automatic sprinkler system. High humidity was maintained over a period of three days in the initial stage of the infection. Fourteen days after inoculation, trichothecene concentrations were determined in spikes.

Determination of trichothecene concentrations in durum wheat grain in the greenhouse experiment

Spikes for analyses were sampled 14 days after inoculation in the greenhouse experiment. Mycotoxin levels in spikes contaminated with F. graminearum were determined according to the procedure described by Wachowska et al.52. Spike samples of 10 g each were ground in a laboratory mill (WŻ−1, Poland). Ground samples were cleaned, and trichothecenes were isolated by gas chromatography (Hewlett Packard GC 6890) coupled with mass spectrometry (Hewlett Packard 5972 A, Waldbronn, Germany), using an HP-5MS, 0.25 mm × 30 m capillary column. Group A trichothecenes (scirpentriol (STO), H-2 toxin, T-2 toxin, and T-2 tetraol) were analyzed as trifluoracetic anhydride (TFAA) derivatives. 100 µL of TFAA was added to a dried sample. After 20 min, the reagent was evaporated to dryness under nitrogen. The residue was dissolved in 500 µL of isooctane, and 1 µL was injected onto a gas chromatograph-mass spectrometer. Group B trichothecenes (DON, NIV, 3-ADON, 15-ADON) were analyzed as trimethylsilyl ether (TMS) derivatives. The LoQ for mycotoxins was 0.1 µg/kg.

Phenotypic data analysis

The results of the phenotypic analysis of eight durum wheat cultivars grown in the greenhouse experiment were used to evaluate the correlations between susceptibility to infections caused by fungi of the genus Fusarium and the accumulation of group B trichothecenes vs. plant height and spike density. Two weeks after inoculation, spike health was evaluated according to a previously described procedure. The normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) was determined with the use of a reflectance-based device (Photon System Instruments, Czech Republic). The NDVI was measured at two points on 10 flag leaves in each biological replicate and in each cultivar. The NDVI is used in precision agriculture, and it is calculated by dividing the difference between near-infrared and red reflectance bands by their sum. Chlorophyll readily absorbs red light (low reflectance), but not near-infrared light (high reflectance and transmission)49. In the early dough stage (BBCH 83), plant height, spike length, and the number of spikelets per spike were measured in eight durum wheat cultivars grown in the greenhouse. Spike density was calculated using the following formula: SD = (n-1) × 10 ⁄ l, where SD is spike density, n is the number of spikelets per spike, and I is rachis length.

DNA extraction and quantification

Leaves were digested in liquid nitrogen, and DNA was extracted with the Bead-Beat MicroAX Gravity kit (A&A Biotechnology, Poland). DNA samples were quantified using a NanoDrop One spectrophotometer (Nanodrop Technologies) and diluted to a working concentration of 30 ng/µL.

PCR amplification and analysis of PCR products

After extraction, samples of genomic DNA were diluted to 50–100 ng/µL, and the targeted DNA fragments were amplified in an Eppendorf Gradient Mastercycler (Eppendorf, Germany). Primers specific for the genes listed in Supplementary Table S1 were used to identify resistance alleles and determine wheat plants’ susceptibility to FHB, STB, and PM. The PCR mix with a volume of 50 µL was composed of 5 µL (50–100 ng/µL) of DNA, 1 µL (10 µmol) of each primer, and 20 µL of sterile ddH2O. The PCR protocol consisted of initial denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min, 35 cycles at 94 °C for 30 s, hybridization at the temperatures given in Table S1 for 30 s and at 72 °C for 2 min, and elongation at 72 °C for 10 min. DNA fragments were separated by electrophoresis on 1.2% agarose gel at 150 V for 30 min. Nucleic bands on gels were visualized by staining with GeneFinder (Bio-V, Xiamen, Fujian, China).

Statistical analysis

The results were processed by analysis of variance (ANOVA), and the significance of differences between means was estimated with the Student-Newman-Keuls (SNK) multiple comparison test at p < 0.01. Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated. All statistical analyses were performed in the Statistica 13 program53.

Results

Health status of field-grown durum wheat plants

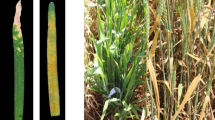

On average, symptoms of FHB were observed on 3.1%, 3.0%, and 60.5% of spikes in 2018, 2019, and 2020, respectively (Fig. 2). The significant increase in the prevalence of FHB symptoms in 2020 was caused by abundant precipitation during durum wheat flowering. In southern Poland, rainy weather persisted on nearly every day of the flowering period. In the third year of the study, the infection reached epidemic proportions, and the severity of FHB was 4.85 times higher in Niedrzwica Kościelna than in Bałcyny. Durum wheat cvs. IS Duragold, Duralis, Duramant, IS Duranegra, Durasol, Floradur, and Tamadur were less susceptible to infection by Fusarium fungi under field conditions (Table 1). In 2020, symptoms of FLB were noted on 90.5–100% of leaves in all cultivars grown in south-eastern Poland, and pathological changes were observed on 46.7–90% of leaf area on average (Fig. 3). In 2020, symptoms of STB were observed on 62.6% of flag leaves and affected 7.3% of leaf area in Bałcyny (Fig. 2). Cultivar Tessadur was least susceptible to Z. tritici infection (Fig. 4). Symptoms of PM were observed on lower leaves in all cultivars, whereas flag leaves were affected only in cvs. Floradur, Durasol, and Tamadur (Table 1).

In the greenhouse experiment, heading and anthesis were initiated on the earliest dates in cv. Duralis and on the latest dates in cv. Duramant (Table 2). Heading and flowering stages were particularly long and uneven (10 days) in cv. Durasol. The flowering stage was also relatively long in cvs. Duralis (7 days), Duramant (5 days), and Floradur (5 days). In turn, anthesis lasted only two days in cvs. IS Duragold and IS Duranegra. In the greenhouse experiment, the highest NDVI values were noted in cvs. IS Duragold and Duramonte (Table 2). Fourteen days after inoculation with F. graminearum, symptoms of FHB were observed on the spikes of all analyzed cultivars (Table 2). Cultivar IS Duragold was most resistant to primary infection by F. graminearum and the growth of fungal hyphae on the rachis (type 1 and 2 resistance) (Table 2). Cultivars Tamadur and Durasol were most severely infected by the pathogen.

Trichothecene concentrations in durum wheat grain (greenhouse experiment)

In plants inoculated with F. graminearum (15ADON genotype), DON was accumulated in the spike tissues of all durum wheat cultivars (Table 3). Deoxynivalenol concentrations were highest in cv. Duramant (1582 µg/kg) and lowest in cv. Duralis (955 µg/kg). Other group B (FUS-X, 3ADON, 15ADON, and NIV) and group A trichothecenes (STO, T2-tetraol, and HT-2) were also identified in all grain samples. In addition, high concentrations of 3ADON and 15ADON were noted in the grain of cvs. Duramant and Durasol. The results of the rank-sum test comparing the concentrations of group A and B trichothecenes with actual DON levels in the grain of eight durum wheat cultivars are presented in Fig. 5. The content of group A trichothecenes was lowest in the grain of cvs. Floradur and Duramant. The content of group B trichothecenes, in particular DON, was highest in the grain of cv. Duramant.

Detection of resistance genes

Molecular markers associated with Fhb2, Xgwm, Stb2, Stb 3, and Pm36 genes were identified in all analyzed durum wheat cultivars (Table 2, Supplementary Figure S1). Markers TaHRC-GSM-F and TaHRC-GSM-R specific for the Fhb1 gene did not amplify DNA fragments. Amplification products of Pm4b and Pm41 genes encoding resistance to PM were not identified (Table 2). The Stb1 gene was not identified in cvs. Duramonte, Floradur, and Tamadur, but it was detected in the remaining cultivars.

Correlation analysis

The health status of durum wheat plants grown in the field and in the greenhouse was bound by significant positive linear correlations with the prevalence and severity of FHB (r = 0.993 and 0.973, respectively) (Table 4). Deoxynivalenol content was bound by a non-significant positive correlation with spike density (0.911) and a non-significant negative correlation with plant height (−0.721). A significant positive correlation was also noted between NDVI and STO levels (0.962).

Discussion

The present study was undertaken to examine the suitability of spring durum wheat cultivars for commercial production in European regions where this cereal is not traditionally grown. Rapid climate change and the growing consumption of pasta and groats have increased the interest in durum wheat in Central Europe. Spring durum wheat cultivars developed in Austria, France, Slovakia, and Germany were evaluated for resistance to pathogens causing FHB, STB, and PM. During the three-year study, an FHB epidemic occurred only in 2020 in both experimental sites due to high temperature and high humidity in the flowering stage65. The study demonstrated that factors responsible for passive immunity, including plant height, spike density, and the date and duration of anthesis, played a key role in the development and/or progression of FHB. The content of DON was higher in the grain of shorter cultivars with compact spikes than in the grain of taller cultivars with loose spikes. Similar observations were previously made by Buerstmayr et al.7,18 and Mesterhazy54. According to Buerstmayr et al.7, spikes dry more rapidly and are less susceptible to infection in taller than in shorter plants, even if the difference in height is only 10 cm. Cultivars with a shorter flowering period (IS Duragold and IS Duranegra) were also less infected by Fusarium fungi. Fusarium fungi are pathogens, and wheat is most susceptible to these infectious agents during flowering13. Beccari et al.14 reported that F. poae, F. avenaceum, and F. graminearum highly aggressive produced DON and 15ADON in the early stages of infection and that the concentrations of these mycotoxins in wheat spikes peaked three days after anthesis. In the present study, the NDVI was significantly negatively correlated with spike density, the severity and prevalence of FHB, and the concentration of group A trichothecenes. However, the relationship between NDVI and the productivity of durum wheat cultivars remains insufficiently investigated in the literature47 therefore, at this stage of research, it can be assumed that NDVI cannot be used to evaluate plant health or the performance of durum wheat cultivars.

In durum wheat, resistance to FHB is a quantitative trait that is conditioned by many genes located on different chromosomes55. In this study, the markers of Fhb2 and Xgwm2 genes, but not the Fhb1 gene (syn. Qfhs.ndsu-3BS), were identified in German and Slovakian cultivars. To date, Fhb1 has been identified in several dozen studies mapping QTL in hexaploid wheat whose source of resistance to FHB was the Chinese cultivar Sumai 318. Buerstmayr et al.7 identified the Fhb1 gene in a tetraploid T. dicoccum × T. durum hybrid. They also found that the Fhb1 allele in Sumai 3 was not homologous with the allele in the tetraploid cultivar Floradur. In turn, the Fhb2 gene located on chromosome 6BS was detected in a tetraploid hybrid obtained by crossing T. durum and T. carthlicum56. In the current study and in the work of Soresi et al.55, PCR based on the Xgwm2 marker produced an amplification band with an estimated length of 200 bp, which points to the presence of an allele encoding resistance to infections caused by Fusarium spp. In a study by Soresi et al.55, the gene associated with the Xgwm2 marker was related to the proteins involved in the recognition of plant pathogens and early responses to infection, including proteins encoded by resistance (R) genes42. This group of genes includes resistance protein RPM1 which was mapped on chromosome 3AS and is activated when F. graminearum infects wheat bread with type 2 resistance originating from the FHB-resistant cv. Sumai 357,58. Several pathogenesis-related (PR) proteins, such as RPM1, participate in defense responses to FHB, but earlier, more rapid and/or higher accumulation of these transcripts was noted in resistant than in susceptible genotypes59. However, durum wheat can become infected even in the presence of genes conferring resistance to Fusarium pathogens. Durum wheat may be more susceptible to infections caused by Fusarium spp. not only because it lacks resistance genes, but also because it carries effective susceptibility factors or suppressor genes that inhibit the expression of resistance genes7.

In the present study, symptoms of STB were observed mainly in the epidemic year of 2020, when IS Duragold was most susceptible and Tessadur was least susceptible to Z. tritici infection. In 2020, symptoms of infection were observed on 60% of flag leaves on average, but the severity of the infection was significantly lower (7%) than that reported by Chedli et al.60 in Tunisia (40%). In May and June 2020, high precipitation and moderate temperatures (14–19 °C) accelerated the spread of infection. In other experiments, symptoms of STB were observed on leaves 14–21 days after infection, and the pathogen infected host plants mainly through leaf stomata31.

The alleles of Stb1, Stb2, and Stb3 genes were identified in nearly all durum wheat cultivars examined in this study (Stb1 was not identified in cvs. Duramonte, Floradur, and Tamadur). Stb1, Stb2, and Stb3 were the first STB resistance genes to be named in bread wheat33. These genes were mapped to the long arms of chromosome 5BL61, the short arm of chromosome 1BS42, and the short arm of chromosome 7AS62. An extensive study examining 236 wheat cultivars grown in the United Kingdom in the 1990 s and their phylogenetic ancestors revealed that wheat has two types of resistance to STB33,63. Qualitative resistance against pathogens with low virulence is effectively controlled by major genes, and the segregation of a qualitative gene can lead to considerable differences between resistant and susceptible groups of offspring63. Quantitative resistance is regulated by many genes, and it is usually effective against all genotypes of Z. tritici, but the segregation of minor genes that alter susceptibility to STB in the offspring, can obscure the segregation of major qualitative genes33.

Powdery mildew decreases wheat yields around the world due to the high severity of the disease, as well as the emergence of fungicide-resistant forms of B. graminis f.sp. tritici64. In the present study, this pathogen was effectively controlled with fungicides. The severity of PM was low, and symptoms of disease were observed on flag leaves in only three cultivars (Floradur, Tamadur, and Durasol). However, only the marker of the Pm36 resistance gene was identified in the studied cultivars, which implies that the emergence of fungicide-resistant populations of the pathogen in epidemic years could prevent the achievement of satisfactory yields. In the work of Blanco et al.40, this gene was introgressed from Triticum turgidum var. dicoccoides into durum wheat. The Pm36 was localized on the long arm of chromosome 5BL, and a genetic analysis of populations from resistant introgression lines confirmed the hypothesis that resistance to PM is controlled by a single dominant gene.

Conclusions

The results of this study indicate that French (RGT Aventadur, RGT Monbecur, RGT Voildur, Haristide) and German (Macrodur, Anvengur) cultivars of durum wheat may face challenges in cultivation under current climatic and phytopathological conditions in Poland due to unfavorable weather conditions and low resistance to native populations of pathogens such as Fusarium, Z. tritici, and B. graminis f.sp. tritici. The selection of taller cultivars with moderately dense spikes poses a challenge for wheat breeders. In the present study, IS Duragold and IS Duranegra were the only durum wheat cultivars that were moderately susceptible to FHB.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- 15ADON:

-

15-Acetyldeoxynivalenol

- 3ADON:

-

3-Acetyldeoxynivalenol

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- BBCH:

-

Biologische Bundesanstalt, Bundessortenamt und Chemische Industrie

- D3G:

-

Deoxynivalenol-3-glucoside

- DON:

-

Deoxynivalenol

- FHB:

-

Fusarium head blight

- FLB:

-

Fusarium leaf blight

- FUS-X:

-

Fusarenon-X

- HT-2:

-

HT-2 toxin

- LC MS/MS:

-

Liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry

- NDVI:

-

Normalized difference vegetation index

- NIV:

-

Nivalenol

- PDA:

-

Potato dextrose agar

- PM:

-

Powdery mildew

- QTL:

-

Quantitative trait loci

- SNK:

-

Student-Newman-Keuls multiple comparison test

- STB:

-

Septoria tritici blotch

- STO:

-

Scirpentriol

- T-2:

-

T-2 toxin

References

Martínez-Moreno, F., Ammar, K. & Solís, I. Global changes in cultivated area and breeding activities of durum wheat from 1800 to date: a historical review. Agronomy 12, 1135. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy12051135 (2022).

Rosentrater, K. A. & Evers, A. D. Kent’s Technology of Cereals: An Introduction for Students of Food Science and Agriculture, 900 (Woodhead Publishing, 2017).

Stone, A. K., Wang, S., Tulbek, M., Koksel, F. & Nickerson, M. T. Processing and quality aspects of Bulgur from Triticum durum. Cereal Chem. 97, 1099–1110. https://doi.org/10.1002/cche.10347 (2020).

Haugrud, A. R. P., Achilli, A. L., Martínez-Peña, R. & Klymiuk, V. Future of durum wheat research and breeding: insights from early career researchers. Plant. Genome. 18, e20453. https://doi.org/10.1002/tpg2.20453 (2025).

Wyzińska, M. & Różewicz, M. Durum wheat – crop cultivation strategies, importance and possible uses of grain. Pol. J. Agron. 44, 30–38. https://doi.org/10.26114/pja.iung.436.2021.44.05 (2021).

Suchowilska, E. et al. A comparison of phenotypic variation in Triticum durum Desf. Genotypes deposited in gene banks based on the shape and color descriptors of kernels in a digital image analysis. PLoS One. 17, e0259413. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0259413 (2022).

Buerstmayr, M. et al. Mapping of QTL for fusarium head blight resistance and morphological and developmental traits in three backcross populations derived from Triticum dicoccum × Triticum durum. Theor. Appl. Genet. 125, 1751–1765. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00122-012-1951-2 (2012).

Ji, F. et al. Occurrence, toxicity, production and detection of Fusarium mycotoxin: a review. Food Prod. Process. Nutr. 1, 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43014-019-0007-2 (2019).

Pasquali, M. et al. A European database of Fusarium graminearum and F. culmorum trichothecene genotypes. Front. Microbiol. 7, 406. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2016.00406 (2016).

Crippin, T. et al. Fusarium graminearum populations from maize and wheat in Ontario, Canada. World Mycotoxin J. 13, 355–366. https://doi.org/10.3920/WMJ2019.2532 (2020).

Gil-Serna, J., Vázquez, C. & Patiño, B. Genetic regulation of aflatoxin, Ochratoxin A, trichothecene, and Fumonisin biosynthesis: A review. Int. Microbiol. 23, 89–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10123-019-00084-2 (2020).

Merhej, J., Richard-Forget, F. & Barreau, C. Regulation of trichothecene biosynthesis in Fusarium: recent advances and new insights. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 91, 519–528. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-011-3397-x (2011).

Yoshida, M. Studies on the control of fusarium head blight of barley and wheat and Mycotoxin levels in grains based on time of infection and toxin accumulation. J. Gen. Plant. Pathol. 78, 425–426. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10327-012-0413-7 (2012).

Beccari, G. et al. Effect of wheat infection timing on fusarium head blight causal agents and secondary metabolites in grain. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 290, 214–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2018.10.014 (2019).

Siou, D. et al. Effect of wheat Spike infection timing on fusarium head blight development and Mycotoxin accumulation. Plant. Pathol. 63, 390–399. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppa.12106 (2014).

Lionetti, V. et al. Cell wall traits as potential resources to improve resistance of durum wheat against Fusarium graminearum. BMC Plant. Biol. 15, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-014-0369-1 (2015).

Duba, A., Goriewa-Duba, K. & Wachowska, U. Trichothecene genotypes analysis of Fusarium isolates from di-, tetra- and hexaploid wheat. Agronomy 9, 698. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy9110698 (2019).

Buerstmayr, H., Ban, T. & Anderson, J. A. QTL mapping and marker-assisted selection for fusarium head blight resistance in wheat: a review. Plant. Breed. 128, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0523.2008.01550.x (2009).

Ghimire, B. et al. Fusarium head blight and rust diseases in soft red winter wheat in the Southeast united states: state of the art, challenges and future perspective for breeding. Front. Plant. Sci. 11, 1080. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2020.01080 (2020).

Cuthbert, P. A., Somers, D. J. & Brulé-Babel, A. Mapping of Fhb2 on chromosome 6BS: a gene controlling fusarium head blight field resistance in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L). Theor. Appl. Genet. 114, 29–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00122-006-0439-3 (2007).

Steiner, B. et al. Breeding strategies and advances in line selection for fusarium head blight resistance in wheat. Trop. Plant. Pathol. 42, 165–174. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40858-017-0127-7 (2017).

Su, Z., Jin, S., Zhang, D. & Bai, G. Development and validation of diagnostic markers for Fhb1 region, a major QTL for fusarium head blight resistance in wheat. Theor. Appl. Genet. 131, 2371–2380. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00122-018-3159-6 (2018).

Agostinelli, A. M., Clark, A. J., Brown-Guedira, G. & van Sanford, D. A. Optimizing phenotypic and genotypic selection for fusarium head blight resistance in wheat. Euphytica 186, 115–126. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10681-011-0499-6 (2012).

Clark, A. J. et al. Identifying rare FHB-resistant segregants in intransigent backcross and F2 winter wheat populations. Front. Microbiol. 7, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2016.00277 (2016).

Cuthbert, P. A., Somers, D. J., Thomas, J., Cloutier, S. & Brulé-Babel, A. Fine mapping Fhb1, a major gene controlling fusarium head blight resistance in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L). Theor. Appl. Genet. 112, 1465–1472. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00122-006-0249-7 (2006).

Lemmens, M. et al. The ability to detoxify the Mycotoxin Deoxynivalenol colocalizes with a major quantitative trait locus for fusarium head blight resistance in wheat. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 18, 1318–1324. https://doi.org/10.1094/mpmi-18-1318 (2005).

Wachowska, U., Konopka, I., Duba, A., Goriewa, K. & Wiwart, M. The effects of various plant protection methods on the development of Zymoseptoria tritici and Cephalosporium gramineum, grain yield and protein profile. Int. J. Pest Manage. 65, 105–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/09670874.2018.1474282 (2019).

Hailemariam, B. N., Kidane, Y. G. & Ayalew, A. Epidemiological factors of septoria tritici blotch (Zymoseptoria tritici) in durum wheat (Triticum turgidum) in the highlands of Wollo, Ethiopia. Ecol. Processes. 9, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717-020-00258-1 (2020).

Ouaja, M. et al. Identification of valuable sources of resistance to Zymoseptoria tritici in the Tunisian durum wheat landraces. Eur. J. Plant. Pathol. 156, 647–661. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10658-019-01914-9 (2020).

Dalvand, M., Javad, M., Pari, S. & Zafari, D. Evaluating the efficacy of STB resistance genes to Iranian Zymoseptoria tritici isolates. J. Plant. Dis. Prot. 125, 27–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41348-017-0143-3 (2018).

Duba, A., Goriewa-Duba, K. & Wachowska, U. A review of the interactions between wheat And wheat pathogens: zymoseptoria tritici, fusarium spp. And Parastagonospora nodorum. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, 1138. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19041138 (2018).

Hassine, M. et al. Sexual reproduction of Zymoseptoria tritici on durum wheat in Tunisia revealed by presence of airborne inoculum, fruiting bodies and high levels of genetic diversity. Fungal Biol. 123, 763–772. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.funbio.2019.06.006 (2019).

Brown, J. K. M., Chartrain, L., Lasserre-Zuber, P. & Saintenac, C. Genetics of resistance to Zymoseptoria tritici and applications to wheat breeding. Fungal Genet. Biol. 79, 33–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fgb.2015.04.017 (2015).

Yang, N., McDonald, M. C., Solomon, P. S. & Milgate, A. W. Genetic mapping of Stb19, a new resistance gene to Zymoseptoria tritici in wheat. Theor. Appl. Genet. 131, 2765–2773. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00122-018-3189-0 (2018).

Ferjaoui, S. et al. Deciphering resistance to Zymoseptoria tritici in the Tunisian durum wheat landrace accession ‘Agili39’. BMC Genom. 23, 372. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-022-08560-2 (2022).

Rachoń, L., Szumiło, G. & Bobryk-Mamczarz, A. Susceptibility of selected winter wheat genotypes to fungal diseases in relation to the level of cultivation technology (in Polish, english summary, tables). Agron. Sci. Ann. UMCS Sectio E Agricultura. LXXIII (1). https://doi.org/10.24326/asx.2018.1.3 (2018).

Lista odmian roślin rolniczych wpisanych do krajowego rejestru w Polsce. (The Polish National List of Agricultural Plant Varieties) (eds Bujak, H.) 101 (COBORU, 2023) (ISSN 1231–8299).

Gupta, V. et al. Evaluation and identification of resistance to powdery mildew in Indian wheat varieties under artificially created epiphytotic. J. Appl. Nat. Sci. 8, 565–569 (2016).

He, H. et al. Characterization of Pm68, a new powdery mildew resistance gene on chromosome 2BS of Greek durum wheat TRI 1796. Theor. Appl. Genet. 134, 53–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coi.2015.01.014 (2021).

Blanco, A. Molecular mapping of the novel powdery mildew resistance gene Pm36 introgressed from Triticum turgidum var. Dicoccoides in durum wheat. Theor. Appl. Genet. 117, 135–142. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00122-008-0760-0 (2008).

Miranda, L. M., Murphy, J. P., Marshall, D. S., Cowger, C. & Leath, S. Chromosomal location of Pm35, a novel Aegilops Tauschii derived powdery mildew resistance gene introgressed into common wheat (Triticum aestivum L). Theor. Appl. Genet. 114, 1451–1456. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00122-007-0530-4 (2007).

Li, X., Kapos, P. & Zhang, Y. NLRs in plants. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 32, 114–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coi.2015.01.014 (2015).

Bennett, F. G. A. Resistance to powdery mildew in wheat: a review of its use in agriculture and breeding programmes. Plant. Pathol. 33, 279–300. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3059.1984.tb01324.x (1984).

Srichumpa, P., Brunner, S., Keller, B. & Yahiaoui, N. Allelic series of four powdery mildew resistance genes at the Pm3 locus in hexaploid bread wheat. Plant. Physiol. 139, 885–895. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.105.062406 (2005).

Zhu, Z., Kong, X., Zhou, R. & Jia, J. Identification and microsatellite markers of a resistance gene to powdery mildew in common wheat introgressed from Triticum durum. J. Integr. Plant. Biol. 46, 867–872 (2004).

Fabbri, C., Delgado, A., Guerrini, L. & Napoli, M. Precision nitrogen fertilization strategies for durum wheat: a sustainability evaluation of NNI and NDVI map-based approaches. Eur. J. Agron. 164, 127502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eja.2024.127502 (2025).

Kizilgeci, F. et al. Normalized difference vegetation index and chlorophyll content for precision nitrogen management in durum wheat cultivars under semi-arid conditions. Sustainability 13, 3725. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073725 (2021).

Brilli, L. et al. Biochar effects on durum wheat (Triticum durum) under ambient and elevated atmospheric CO2. J. Agric. Food Res. 19, 101719. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jafr.2025.101719 (2025).

Romano, E. et al. Stability maps using historical NDVI images on durum wheat to understand the causes of Spatial variability. Precis Agric. 26, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11119-025-10222-8 (2025).

Meier, U. Phenological growth stages in. In Phenology: an Integrative Environmental Science 269–283 (Springer, 2003).

Foliar and ear diseases on cereals. EPPO Bull. 42 (3) (2012). https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com.

Wachowska, U. et al. A method for reducing the concentrations of Fusarium graminearum trichothecenes in durum wheat grain with the use of Debaryomyces hansenii. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 397, 110211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2023.110211 (2023).

Statistica (Data Analysis Software System) version 13 TIBCO Software Inc. (2017). http://statistica.io

Mesterhazy, A. Types and components of resistance to fusarium head blight of wheat. Plant. Breed. 114, 377–386. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0523.1995.tb00816.x (1995).

Soresi, D., Carrera, A. D., Echenique, V. & Garbus, I. Identification of genes induced by Fusarium graminearum inoculation in the resistant durum wheat line Langdon (Dic-3A)10 and the susceptible parental line Langdon. Microbiol. Res. 177, 53–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micres.2015.04.012 (2015).

Somers, D. J., Fedak, G., Clarke, J. & Cao, W. G. Mapping of FHB resistance QTLs in tetraploid wheat. Genome 49, 1586–1593. https://doi.org/10.1139/g06-127 (2006).

Kong, L., Ohm, H. W. & Anderson, J. M. Expression analysis of defense-related genes in wheat in response to infection by Fusarium graminearum. Genome 50, 1038–1048. https://doi.org/10.1139/g07-085 (2007).

Kugler, K. G. et al. Quantitative trait loci-dependent analysis of a gene co-expression network associated with fusarium head blight resistance in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L). BMC Genom. 14, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-14-728 (2013).

Pritsch, C., Muehlbauer, G. J., Bushnell, W. R., Somers, D. A. & Vance, C. P. Fungal development and induction of defense response genes during early infection of wheat spikes by Fusarium graminearum. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 13, 159–169. https://doi.org/10.1094/mpmi.2000.13.2.159 (2000).

Chedli, R. B. H., M’Barek, S. B., Yahyaoui, A., Kehel, Z. & Rezgui, S. Occurrence of Septoria tritici blotch (Zymoseptoria tritici) disease on durum wheat, triticale, and bread wheat in Northern Tunisia. Chil. J. Agric. Res. 78, 559–568. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-58392018000400559 (2018).

Adhikari, T. B. et al. Molecular mapping of Stb1, a potentially durable gene for resistance to Septoria tritici blotch in wheat. Theor. Appl. Genet. 109, 944–953. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00122-004-1709-6 (2004).

Goodwin, S. B. & Thompson, I. Development of isogenic lines for resistance to septoria tritici blotch in wheat. Czech J. Genet. Plant. Breed. 47, S98–S101. https://doi.org/10.17221/3262-CJGPB (2011).

Brading, P. A., Verstappen, E. C. P., Kema, G. H. J. & Brown, J. K. M. A gene-for-gene relationship between wheat and Mycosphaerella graminicola, the Septoria tritici blotch pathogen. Phytopathology 92, 439–445. https://doi.org/10.1094/phyto.2002.92.4.439 (2002).

Meyers, E., Arellano, C. & Cowger, C. Sensitivity of the U.S. Blumeria Graminis f. sp. tritici population to demethylation inhibitor fungicides. Plant. Dis. 103, 3108–3116. https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-04-19-0715-RE (2019).

Parry, D. W., Jenkinson, P. & McLeod, L. Fusarium ear blight (scab) in small grain cereals—a review. Plant. Pathol. 44, 207–238. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3059.1995.tb02773.x (1995).

Acknowledgements

This research is the result of a long-term study conducted at the Department of Genetics, Plant Breeding and Bioresource Engineering and Department of Entomology, Phytopathology and Molecular Diagnostics Faculty of Agriculture and Forestry of the University of Warmia and Mazury in Olsztyn (research topics Nos. 30.610.007-110 and 30.610.011-110). The authors express their gratitude to A. Poprawska for language editing.

Funding

The study was funded by the Minister of Science under the “Regional Initiative of Excellence” Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

UW – Writing original manuscript, Molecular analyses, MW – Writing—review & editing, Statistical analysis, ES – Data curation, Investigation, EK – Conducting field and glasshouse experiment, WG – Mycotoxin analyses, KS-S – Mycotoxin analyses, DG –Providing research material (seeds of durum cultivars), Field experiment. All authors read and approved of the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wachowska, U., Wiwart, M., Suchowilska, E. et al. Susceptibility of durum wheat to Fusarium graminearum, Blumeria graminis f.sp. tritici, and Zymoseptoria tritici in Poland. Sci Rep 15, 41235 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25121-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25121-1