Abstract

The clinical features of neurocristopathy-related hearing loss, and the correlation between these features and patient improvements after cochlear implantation (CI) are unknown. This study enrolled 16 children with sensorineural hearing loss due to four types of neurocristopathies, Waardenburg syndrome (WS), Noonan syndrome (NS), Kabuki syndrome (KS), and CHARGE syndrome (CS), who underwent CI. Neurodevelopmental assessment was conducted using the Gesell Developmental Schedules, ear development was evaluated using temporal bone computed tomography, and the post-CI auditory nerve response was assessed via neural response telemetry. Auditory performance was evaluated using the categories of the auditory performance scale. Genetic features were examined using whole-exome sequencing. WS/NS Groups achieved excellent auditory-speech outcomes (CAP_3 year/SIR_3 year: WS 7.3/4.0 n = 3, NS 8.0/4.0 n = 1), using Categories of Auditory Performance (CAP) and Speech Intelligibility Rating (SIR), with minimal impact from SOX10 (WS) or PTPN11 (NS) mutations on neurodevelopment. CS Group showed poor recovery (CAP_3 year/SIR_3 year: 3.3/1.8 n = 3) due to CHD7-related cochlear nerve dysplasia and central auditory deficits, Gesell_mean showed a significant positive correlation with CAP_1 year (ρ = 0.83 n = 6 p = 0.042), CAP_3 year was significantly correlated with both implantation CI_age_mon and Gesell_mean independently (ρ = 1.0, n = 3, p < 0.001). Non-CS Groups(WS/NS/KS)showed older CI_age_mon predicted higher 1-year SIR (ρ = 0.77 n = 10 p = 0.009), while structural abnormalities (abnormal_sum) trended toward worse 3-year SIR (ρ=-0.79 n = 5). The integration of genetic, ear structure, and neurodevelopmental assessments can assist in clinical decision making for CI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since 1974, diseases resulting from the abnormal development of neural crest cells (NCCs) and their derivatives have been collectively termed neurocristopathies (NCPs)1. These diseases account for 1/3 of all congenital disabilities. NCCs are multipotent stem cells that can migrate throughout the embryo during the early stages of vertebrate embryonic development2. The development of NCCs is strictly regulated by genes; any abnormal regulation can disrupt NCC development, leading to embryonic malformations that ultimately cause NCPs. NCPs can occur in multiple body parts, affecting a single organ or multiple organs simultaneously, resulting in complex diseases. Surgical correction is the primary treatment for external malformations, while hearing aids and ventilation therapy are used for patients with hearing loss and breathing difficulties. Treatment of NCP-related tumors has advanced to include targeted drug therapy and low-dose chemotherapy.

Gene and stem-cell therapy are also promising treatment options for NCPs3,4. The pathogenic factors of NCPs include gene mutations and abnormal epigenetic modifications within the genetic regulatory network of NCCs, as well as environmental teratogenic factors. Studies using mouse models have revealed that multiple regulatory pathways, including the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP), Wnt, fibroblast growth factor (FGF), and Notch signaling pathways, are involved in the formation of NCCs2. The migration of NCCs is also tightly regulated by various signals5.

NCC derivatives include structures in the outer, middle, and inner ear. Consequently, developmental abnormalities of the ear are a typical feature of NCPs. These abnormalities include underdeveloped or absent external ears (microtia or anotia), aural atresia, and hearing loss6. Abnormal neural crest development can affect ear structure development and cause hearing impairments, including conductive hearing loss due to middle ear structural abnormalities and sensorineural hearing loss due to inner ear malformations7. The pathology of hearing loss involves multiple components, such as the cochlear vestibular ganglion, glial cells, stria vascularis melanocytes, cochlear hair cells, and spiral ganglion cells8. The incidence of hearing impairment in NCPs is high, and the impairment can range from mild to profound in severity9. Clinical experience in diagnosing and treating NCP-related hearing loss is limited, and treatment decisions regarding the use of cochlear implantation (CI) are particularly challenging because the effectiveness of CI lacks sufficient clinical evidence.

The clinical features of different NCPs often overlap, yet vary in genetic origin. NCPs with the same phenotype can arise from disruptions to different developmental processes in various types of NCCs. Conversely, NCPs with different phenotypes may result from mutations in the same gene across different developmental stages of NCCs. Patients with NCPs exhibit phenotypic heterogeneity and etiological homogeneity, posing a substantial challenge to the study of pathogenic mechanisms in NCPs. Notably, Waardenburg syndrome (WS), Noonan syndrome (NS), Kabuki syndrome (KS), and CHARGE syndrome (CS) are four distinct NCPs that are all closely associated with hearing loss. These disorders display some overlap in clinical manifestations yet have no direct genetic correlation. They can cause conductive, sensorineural, and mixed hearing loss, as well as central auditory processing disorders. Importantly, the hearing impairment in these NCPs exhibit gene-specific manifestations.

Whether children with profound deafness can benefit from cochlear implantation (CI) remains a critical clinical concern. Therefore, in this study, we analyzed and compared the clinical and genetic features of NCP-related hearing loss in children with WS, NS, KS, and CS. Patient follow-ups were conducted to assess objective auditory nerve electrophysiology data and auditory/speech evaluations after CI. We believe our findings will provide a basis for developing audiological intervention strategies for these patients.

Methods

Clinical assessment

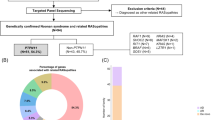

This retrospective observational study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shanghai Children’s Hospital (ethics approval number: 2025R058-E01). We reviewed patients with a diagnosis of NCP-related hearing loss who were evaluated at the Department of Otolaryngology between December 2013 and December 2023. Inclusion criteria comprised (1) confirmed diagnosis of neurocristopathy-related hearing loss, (2) chronological age < 18 years old, and (3) completion of at least 12 months of follow-up. Patients with congenital metabolic disorders were excluded. A total of 25 cases were initially enrolled, with 5 cases excluded and 4 cases lost to follow-up, resulting in 16 cases ultimately included in the study. Sample size calculation was performed using G*Power 3.1. Given the constraints of our retrospective study design with a small sample size (n = 16), the analysis was adequately powered (80% power at α = 0.05) to detect only large effect sizes (Cohen’s d > 1.0), while smaller effects may have gone undetected. Clinical and imaging features were evaluated by experienced otolaryngologists, pediatricians, radiologists, and audiologists.

For each patient, we collected the following data: gender, CI_age_mon, type of disease (WS, NS, KS, and CS), type of mutation, and phenotypic features. Auditory steady state response, acoustic immittance, auditory brainstem responses, and distortion product otoacoustic emission were used for the hearing assessment. Ear structure was assessed through high-resolution computed tomography (CT). The assessment focused primarily on the middle and inner ear. All children included in the study received a cochlear implant with Cochlear implants: Cochlear™CI512/CI622 (Cochlear Ltd., Australia) or MED-EL Sonata/Concerto/Synchrony (MED-EL GmbH, Austria). Neural response telemetry was performed intraoperatively using Neural Response Telemetry, NRT (Cochlear Custom Sound EP Advanced) or Real-Time Tracking, ART (MED-EL MAESTRO). Developmental evaluation used the Gesell Developmental Schedules (GDS), which were administered by trained clinicians in a standardized, child-friendly environment. Performance was systematically documented in five domains: gross motor, fine motor, adaptive, language, and personal-social. Age-appropriate tasks were selected based on the child’s corrected age, and behaviors were scored through structured play and clinician observation. Raw scores were converted to Developmental Quotients (DQ) for each domain. The DQ scores were interpreted as: normal range ≥ 85, mild delay 70–84, and significant delay < 70. The Gesell_mean represents the arithmetic average of the DQ scores across the five domains. Auditory assessment was conducted using the categories of the auditory performance scale, and speech assessment was conducted using the speech intelligibility rating scale. Auditory (Categories of Auditory Performance, CAP) and speech (Speech Intelligibility Rating, SIR) evaluations were performed preoperatively, at 1-year post-CI, and at 3-year post-CI.

Genetic analyses

Genetic analyses were performed with whole exome sequencing (WES), or with multigene panels with Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) techniques WES or targeted gene panel analysis performed. Variants were annotated using ANNOVAR, VEP (Ensembl), or a similar approach for functional impact. Variants were classified into 5 tiers based on 28 ACMG/AMP criteria. Pathogenic support, including PVS1(Pathogenic Very Strong 1): Null variant (nonsense, frameshift) in a loss-of-function (LOF) intolerant gene. PS1/PM5: Amino acid change identical to a known pathogenic variant. PP3: Computational predictions of deleteriousness (e.g., REVEL > 0.7, CADD > 20). Benign support classification, BS1: High allele frequency in population databases. BP4: Silent/neutral predictions from multiple algorithms. False-negative control: All variants of uncertain significance (VUS) and likely benign (LB) variants in known disease-associated genes (e.g., SOX10 for Waardenburg syndrome) were re-evaluated to prevent missed diagnoses. False-positive control: All variants classified as pathogenic (P) or likely pathogenic (LP) were confirmed by Sanger sequencing to ensure reliability. Reporting Criteria: Only P/LP variants with phenotypic relevance were included in the final analysis to avoid interference from clinically irrelevant variants.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Python (v3.10) with the pandas, scikit-learn, and matplotlib libraries. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical Methods Group comparisons of CAP and SIR scores were performed using Kruskal-Wallis tests with Dunn’s post hoc correction (Bonferroni-adjusted) due to small sample sizes and non-normal distributions. Sensitivity analyses included permutation tests (Fisher-Pitman) for the original four groups. Missing data (*) were either excluded or imputed conservatively. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients were computed to assess the relationships between multiple factors and postoperative CAP/SIR scores. Statistical significance was defined at two levels: *p* < 0.05 for standard significance and *p* < 0.01 for high significance in all hypothesis testing. Any missing data points (marked as N/A or NaN in the tables) were excluded pairwise, and the sample size (n) for each specific analysis is explicitly stated in the results text and tables wherever applicable.

Results

Clinical features

This study enrolled 16 children (8 months to 4 years old) that were diagnosed with diverse phenotypes of syndromic hearing loss and underwent CI. These included six, three, one, and six cases of WS, NS, KS, and CS, respectively. Children with different types of NCP-based hearing loss exhibit unique facial features: the iris of children with WS were heterochromic, and there were no abnormalities in the head and facial structure; the patients with NS had protruding foreheads, widened eye distances, and downward inclination of the eye fissures; the patient with KS had cracks on the long eyelid, with a slight outward rotation of one-third of the lower eyelid and a cup-shaped ear on the right side; all the CS patient were with predominant craniofacial anomalies involving the ears and eyes. Table 1 shows the main clinical features of the 16 children, specifically highlighting the ear malformations and the degree of developmental delay. There were observable differences between the types of syndromic hearing loss. WS and NS showed mild malformations of the middle and inner ear (Figs. 1 and 2). KS (Fig. 3) primarily exhibited malformations of the outer and middle ear structures. CS (Fig. 4) showed significant malformations in the outer, middle, and inner ear and showed varying degrees of stenosis or occlusion of the cochlea in different cases (Fig. 5). Cochlear nerve canal stenosis was observed in almost every CS case. Apart from WS, the other three syndromes showed clear craniofacial malformations, growth delay, and varying degrees of neurodevelopmental delay. Gesell scores were below the normal value of 85. Among the syndromes, WS and NS exhibited mild symptoms, KS showed more pronounced symptoms, and CS cases were the most severe.

Ear CT scans in CHARGE syndrome(CS) cases. (a-c) Developmental abnormalities in the middle and inner ear of CS, including underdeveloped semicircular canals, vestibular malformations, an abnormal facial nerve course, a narrow internal auditory canal, and cochlear apical–middle turn hypoplasia. (d) Ossicular chain abnormalities.

Genetic features

We analyzed the genetic test results of 16 cases of syndromic hearing loss. Table 2 shows the mutated genes and key loci and pathways affecting neural crest development.

Post-CI benefits

Most electrodes responded well after CI in KS, NS, and WS cases. In contrast, CS cases showed an overall poor neural response after implantation. Only some electrodes responded, and this occurred only at high stimulation levels. One CS case showed no response to neural response telemetry (Table 3). We summarized and analyzed the auditory and speech evaluation results for the 16 children with syndromic hearing loss. Postoperative auditory and speech scores significantly improved in the KS, NS, and WS groups. In contrast, postoperative outcomes for the CS group showed minimal auditory and speech benefits. Only one postoperative CS case showed significant improvement in auditory scores and slight speech improvement.

Comparison of CAP and SIR following CI in patients with four groups

The comparison of post-CI auditory and speech perception outcomes across four distinct neurocristopathy-associated deafness subtypes revealed the following findings. Group Differences showed (Fig. 6): WS Group: Highest CAP/SIR scores (clustered at upper range). CS Group: Lowest scores (bottom-left clustering). NS Group: Intermediate distribution, overlapping partially with both WS and CS. KS Case (n = 1): Positioned near WS range (CAP = 6.0), suggesting potential WS-like outcomes (but limited by sample size). Due to the small sample size and numerous missing values, only descriptive trend comparisons could be performed, and preliminary intergroup trends should be interpreted with caution. Subjects in the WS and NS groups achieved CAP score improvements of over 6 points and SIR score improvements of 3 points within three years, reaching a high level of performance. The magnitude of improvement in the WS and NS groups was far greater than that in the CS group. With only a single subject’s data, the effect of the KS strategy was intermediate between the WS/NS and CS groups. The CS group demonstrated the least ideal outcomes(Table 4). The extremely small sample size-particularly in the NS group (n = 3, with only one 3-year data point) and the KS group (n = 1)-renders any statistical conclusion unreliable. Furthermore, the extensive missing data, with over half of the subjects lacking 3-year follow-up, may introduce serious bias. Consequently, valid statistical comparisons among the four groups were not feasible, and the current analysis remains purely descriptive.

Distribution of Post-CI CAP/SIR Scores Across Neurocristopathy Subtypes. Scatter plot comparing cochlear implantation (CI) outcomes among four neurocristopathy-related deafness subtypes: Waardenburg syndrome (WS, n = 3), Noonan syndrome (NS, n = 1), Kabuki syndrome (KS, n = 1), and CHARGE syndrome (CS, n = 4). Each point represents an individual patient’s CAP (Categories of Auditory Performance) and SIR (Speech Intelligibility Rating) scores at 3-year post-CI follow-up.

Distinct predictors of auditory-speech outcomes between CS group and WS/NS/KS group

Based on the analysis results in Sect. “Comparison of CAP and SIR following CI in patients with four groups”, differences in CAP/SIR scores were observed between the CS group and the other three groups. The samples were further divided into two groups for analysis: the CS group (n = 6) and the non-CS group (WS/NS/KS groups, n = 10). The analysis focused on the correlation between CAP (Categories of Auditory Performance) and SIR (Speech Intelligibility Rating) outcomes (at 1-year and 3-year post-implantation) and relevant variables (CI_age_mon: CI implantation age in months; gender_male: male = 1; Gesell_mean: average Gesell developmental score; abnormal_sum: total number of middle ear and neural structural abnormalities). Results for the CS group: Gesell_mean showed a significant positive correlation with CAP_1 year (p = 0.042), Age and Gesell_mean also demonstrated significant correlations with CAP_3 year (p < 0.05), while no predictors reached significance for SIR outcomes. Non-CS group results show: CI_age_mon showed a significant positive correlation with SIR_1 year (p = 0.009). No other significant correlations were observed, though abnormal_sum demonstrated a negative trend with SIR_3 year (p = 0.111, marginal significance). A positive but non-significant correlation was found between Gesell_mean and CAP_3 year.For details, see Table 5.

Discussion

Waardenburg syndrome (WS), Noonan syndrome (NS), Kabuki syndrome (KS), and CHARGE syndrome (CS) are classic neurocristopathies (NCPs) frequently associated with severe sensorineural hearing loss. Each syndrome involves distinct gene mutations that disrupt neural crest cell development through different mechanisms, leading to variable cochlear implantation (CI) outcomes.

In WS, mutations in genes such as PAX3, EDN3, EDNRB, MITF, and SOX10 impair melanocyte development, consequently affecting stria vascularis function in the cochlea10,11,12,13. However, all six WS children in this cohort exhibited normal cochlear structure and auditory nerve morphology, achieving excellent CAP/SIR scores at 3 years post-implantation. Although the two SOX10-mutation carriers showed slightly lower preoperative Gesell Developmental Scores (GDS), their auditory-speech rehabilitation outcomes were comparable to other WS children, suggesting minimal neurodevelopmental impact of this mutation.

NS is primarily caused by PTPN11 mutations that disrupt the Ras/MAPK pathway14,15,16,17,18. Although sensorineural hearing loss is not a typical manifestation of NS, all three PTPN11-mutated children in this study demonstrated significant auditory-speech improvement post-CI. Imaging revealed no notable structural abnormalities, and GDS scores (85) were only marginally below normal, consistent with previous reports supporting CI efficacy in NS patients19,20.

KS is mainly attributed to KMT2D mutations and presents with heterogeneous craniofacial and cognitive phenotypes21,22,23. The single KS case in this study exhibited mild external ear malformations and moderate developmental delay (per GDS scores) but showed remarkable post-CI improvement. Over 5 years of follow-up, this patient maintained progressive and stable gains in auditory-speech function, suggesting that carefully selected KS patients may also benefit from CI.

CS, associated with CHD7 mutations, is characterized by inner ear malformations and central nervous system developmental defects24,25,26,27. All CS children in this cohort displayed significant neurodevelopmental delays and cochlear nerve abnormalities. Intraoperative neural response telemetry (NRT) showed partial or absent responses in most cases, with only three patients demonstrating minor auditory/speech improvements within 3 years post-CI, aligning with reports of poor CI outcomes in cochlear nerve dysplasia28. Previous studies have shown that CS children implanted before chronological age 3 with consistent device use for > 5 years achieve auditory benefits and disease-specific quality-of-life improvements, with spoken language abilities comparable to mildly affected non-CI CS children29. Our study found only one case with significant language improvement, which may reflect shorter follow-up duration and potential for further speech rehabilitation.

CI outcomes in NCPs demonstrate gene-specific stratification: Despite similar implantation CI_age_mon and preoperative hearing levels, CHD7-related CS patients showed poorer auditory-speech rehabilitation trend than WS, NS, and KS groups(Table 4), likely due to neurodevelopmental pathology differences. Mutations in SOX10 (WS), PTPN11 (NS), and KMT2D/KDM6A (KS) had minimal impact on CI efficacy, consistent with prior studies30,31,32. In contrast, CHD7 induces deficits through a dual mechanism: aberrant neural crest cell migration causes cochlear malformations (particularly cochlear nerve foraminal stenosis), while CHD7 variants impair GABAergic neuron development33, compromising central auditory pathways. This combined neurological dysfunction ultimately limits CI effectiveness.

Beyond genetic stratification, other factors differentially influenced CI outcomes. The CS group showed stronger associations with Gesell scores: the significant positive correlation between Gesell_mean and CAP_1 year (ρ = 0.83 n = 6 p = 0.042) indicated better 1-year auditory performance with higher developmental levels. CI_age_mon and Gesell scores also significantly correlated with CAP_3 year (ρ = 1.0 n = 4 p < 0.001), suggesting better rehabilitation outcomes with younger implantation age, consistent with literature emphasizing early auditory intervention in CS due to chronological age-prognosis correlation34. These perfect correlations (ρ = 1.00) are based on a very small sample (n = 4) and should be interpreted with extreme caution due to their inherent instability. However, our CS results partially conflicted with a meta-analysis35,36,37 reporting auditory improvement in all studies assessing pre- vs. post-CI hearing, whereas only 50% of our cohort improved—possibly due to shorter follow-up (mean 2 vs. 5 years) and younger implantation CI_age_mon (mean 27.3 vs. 52.8 months). Longer follow-up is needed for definitive assessment.

In non-CS groups, CI_age_mon exerted greater influence on SIR outcomes. The significant positive correlation between CI_age_mon and SIR_1 year (p = 0.009) suggested that older implantation CI_age_mon predicted better 1-year speech intelligibility, potentially reflecting higher central maturity in older children during short-term follow-up. The positive correlation between older implantation age (CI_age_mon) and better 1-year SIR outcomes in the non-CS group may reflect short-term maturational advantages in older children, allowing them to more rapidly adapt to the cochlear implant. It should not be interpreted as evidence supporting a benefit of deliberately delaying implantation. However, at 3 years, abnormal_sum showed a negative correlation with SIR_3 year (ρ=−0.79), though not statistically significant, implying that greater numbers of structural abnormalities may impair long-term speech outcomes. Gesell_mean positively but non-significantly correlated with CAP_3 year, supporting the established notion that overall neurodevelopmental status predicts CI outcomes34. In this study, any conclusions regarding Kabuki syndrome are preliminary and based on a single case, and therefore must be interpreted with great caution.

This study suggests genotype-phenotype correlations in syndromic deafness CI outcomes: SOX10 and PTPN11 primarily affect peripheral auditory structures while preserving central plasticity, whereas CHD7 compromises both cochlear development and central auditory function. KMT2D may modulate neural plasticity windows via epigenetic regulation. Therefore, CI strategies for NCP-related deafness should integrate genetic testing (causative mutations), imaging (cochlear/nerve morphology), and neurodevelopmental assessment. Study limitations include small CS sample size (n = 6) precluding CHD7 subtype analysis, single KS case requiring validation, and need for extended follow-up. Further research is warranted.

In conclusion, NCP-related hearing loss requires gene-specific counseling. Patients with NS and WS are ideal candidates for CI, while CS patients require careful evaluation. Integrating genetic testing and neurodevelopmental assessments can optimize patient selection strategies.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request with permission of Shanghai Children’s Hospital.

References

Bolande, R. P. The neurocristopathies: A unifying concept of disease arising in neural crest maldevelopment. Hum. Pathol. 5, 409–429 (1974).

Sakai, D., Dixon, J., Achilleos, A., Dixon, M. & Trainor, P. A. Prevention of treacher Collins syndrome craniofacial anomalies in mouse models via maternal antioxidant supplementation. Nat. Commun. 7, 10328 (2016).

Jones, N. C. et al. Prevention of the neurocristopathy treacher Collins syndrome through Inhibition of p53 function. Nat. Med. 14 (2), 125–133 (2008).

Cordero, D. R. et al. Cranial neural crest cells on the move: Their roles in craniofacial development. Am J Med Genet A. 155A, 270–279 (2011).

de Haan, S. et al. Ectoderm barcoding reveals neural and cochlear compartmentalization. Science 388(6742), 60–68 (2025).

Ritter, K. E. & Martin, D. M. Neural crest contributions to the ear: implications for congenital hearing disorders. Hear. Res. 376, 22–32 (2019).

Kalinousky, A. J. et al. KMT2D deficiency causes sensorineural hearing loss in mice and humans. Genes (Basel). 15 (1), 48 (2023).

Bae, C. J. & Saint-Jeannet, J. P. Induction and specification of neural crest cells: extracellular signals and transcriptional switches. Neural Crest Cells :27–49. (2013).

Szabó, A. & Mayor, R. Mechanisms of neural crest migration. Annu. Rev. Genet. 52, 43–63 (2018).

Boudjadi, S., Chatterjee, B., Sun, W., Vemu, P. & Barr, F. G. The expression and function of PAX3 in development and disease. Gene 666, 145–157 (2018).

Sánchez-Mejías, A., Fernández, R. M., López-Alonso, M., Antiñolo, G. & Borrego, S. New roles of EDNRB and EDN3 in the pathogenesis of hirschsprung disease. Genet. Med. 12, 39–43 (2010).

Lakhdar, Y. et al. The Tietz syndrome associated with cardiac malformation: A case report with literature review. Egypt. J. Otolaryngol. 37, 112 (2021).

Pingault, V., Zerad, L., Bertani-Torres, W. & Bondurand, N. SOX10: 20 years of phenotypic plurality and current Understanding of its developmental function. J. Med. Genet. 59, 105–114 (2022).

Tartaglia, M., Gelb, B. D. & Zenker, M. Noonan syndrome and clinically related disorders. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 25, 161–179 (2011).

Kontaridis, M. I. et al. Deletion of Ptpn11 (Shp2) in cardiomyocytes causes dilated cardiomyopathy via effects on the extracellular signal-regulated kinase/mitogen-activated protein kinase and RhoA signaling pathways. Circulation 117, 1423–1435 (2008).

Nakamura, T., Gulick, J., Colbert, M. C. & Robbins, J. Protein tyrosine phosphatase activity in the neural crest is essential for normal heart and skull development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 106, 11270–11275 (2009).

Tajan, M., de Rocca Serra, A., Valet, P., Edouard, T. & Yart, A. SHP2 sails from physiology to pathology. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 58, 509–525 (2015).

Zhang, Q. et al. The gain-of-function mutation E76K in SHP2 promotes CAC tumorigenesis and induces EMT via the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Mol. Carcinog. 57, 619–628 (2018).

Gao, X. et al. Congenital sensorineural hearing loss as the initial presentation of PTPN11-associated Noonan syndrome with multiple lentigines or Noonan syndrome: clinical features and underlying mechanisms. J. Med. Genet. 58, 465–474 (2021).

Yang, T. et al. Co-occurrence of sensorineural hearing loss and congenital heart disease: etiologies and management. Laryngoscope 134, 400–409 (2024).

Shpargel, K. B., Starmer, J., Wang, C., Ge, K. & Magnuson, T. UTX-guided neural crest function underlies craniofacial features of Kabuki syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 114, E9046–E9055 (2017).

Shan, Z. et al. KMT2D deficiency leads to cellular developmental disorders and enhancer dysregulation in neural-crest-containing brain organoids. Sci. Bull. (Beijing). 69, 3533–3546 (2024).

Schwenty-Lara, J., Nehl, D. & Borchers, A. The histone methyltransferase KMT2D, mutated in Kabuki syndrome patients, is required for neural crest cell formation and migration. Hum. Mol. Genet. 29, 305–319 (2020).

Okuno, H. et al. CHARGE syndrome modeling using patient-iPSCs reveals defective migration of neural crest cells harboring CHD7 mutations. eLife 6, e21114 (2017).

Williams, R. M. et al. Chromatin remodeller Chd7 is developmentally regulated in the neural crest by tissue-specific transcription factors. PLOS Biol. 22, e3002786 (2024).

Choo, D. I., Tawfik, K. O., Martin, D. M. & Raphael, Y. Inner ear manifestations in CHARGE: Abnormalities, treatments, animal models, and progress toward treatments in auditory and vestibular structures. Am. J. Med. Genet. C Semin Med. Genet. 175, 439–449 (2017).

Sanosaka, T. et al. Chromatin remodeler CHD7 targets active enhancer region to regulate cell type-specific gene expression in human neural crest cells. Sci. Rep. 12, 22648 (2022).

Buchman, C. A. et al. Cochlear implantation in children with labyrinthine anomalies and cochlear nerve deficiency: implications for auditory brainstem implantation. Laryngoscope 121, 1979–1988 (2011).

Vesseur, A. et al. Influence of hearing loss and cognitive abilities on Language development in CHARGE syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 170, 2022–2030 (2016).

Qin, F., Guo, S., Yin, X., Lu, X. & Ma, J. Auditory and speech outcomes of cochlear implantation in patients with Waardenburg syndrome: a meta-analysis. Front. Neurol. 15, 1372736 (2024).

Yang, K. S., Tsai, M. H., Hwang, C. F., Lin, L. H. & Yang, C. H. Cochlear implantation in a patient with Noonan syndrome and enlarged cochlear apertures. Laryngoscope Epub ahead of print. (2025).

Vesseur, A., Cillessen, E. & Mylanus, E. Cochlear implantation in a patient with Kabuki syndrome. J. Int. Adv. Otol. 12 (1), 129–131 (2016).

Jamadagni, P. et al. Chromatin remodeller CHD7 is required for GABAergic neuron development by promoting PAQR3 expression. EMBO Rep. 22 (6), e50958 (2021).

McKinney, S. Cochlear implantation in children under 12 months of age. Curr. Opin. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 25 (5), 400–404 (2017).

Amin, N., Sethukumar, P., Pai, I., Rajput, K. & Nash, R. Systematic review of cochlear implantation in CHARGE syndrome. Cochlear Implants Int. 20 (5), 266–280 (2019).

Monshizadeh, L., Hashemi, S. B., Rahimi, M. & Mohammadi, M. Cochlear implantation outcomes in children with global developmental delay. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 162, 111213 (2022).

Kral A. Pathophysiology of hearing loss : Classification and treatment options. HNO. 65(4), 290–297.(2017).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the participants who shared their time and experiences for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. The study was conceptualized by Kun Ni. Data analysis was performed by Jia Fang. Reagents and other essential materials were contributed by Wenyan Fan and Fang Chen. The study was supervised by Xiaoyan Li. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Kun Ni and Jia Fang. The manuscript was reviewed and edited by Xiaoyan Li and Wen Lu. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript and have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted following the guidelines of the Ethics Committee of Shanghai Children’s Hospital and was approved for human research (approval number: 2025R058-E01). All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. For participants under the chronological age of 16 (or the legal chronological age of consent in your country), informed consent was obtained from their parents or legal guardians.

Consent for publication

The patients consent for publication of this study and accompanying images. Parents/guardians provided consent for publication of de-identified data and images.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ni, K., Fang, J., Fan, W. et al. Analysis of the clinical features of neurocristopathy-related hearing loss and how these relate to outcomes after cochlear implantation. Sci Rep 15, 41227 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25126-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25126-w