Abstract

This study explores the potential of Carboxymethy Cellulose/Amoxicillin/Nano-Hydroxyapatite suspensions (CMC/AMX/nHA) for the treatment of dentin hypersensitivity, particularly in the context of periodontitis treatment. The CMC/AMX/nHA suspension was compared with the commonly used clinical desensitizing agent Bifluorid12 and the broad-spectrum antibiotic Minocycline Hydrochloride. Microscopic observation and antimicrobial experiments were conducted to quantitatively and qualitatively assess the ability of CMC/AMX/nHA to seal dentinal tubules and its antimicrobial properties. Additionally, a resin bonding experiment was performed to evaluate the effect of CMC/AMX/nHA on dentin bonding. The research results indicate that CMC/AMX/nHA demonstrates good biocompatibility, with excellent drug delivery capabilities, bacterial growth inhibition, and no interference with subsequent repair treatments during desensitization therapy. These findings suggest that CMC/AMX/nHA has high translational potential and may be effectively applied in clinical oral medicine.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Dentin hypersensitivity is characterized by sudden, sharp pain when dentin is exposed to stimuli such as heat, cold, airflow, touch, or chemicals, and is not attributed to any other dental conditions or diseases1. Risk factors for dentin hypersensitivity include gingival recession, especially due to improper brushing, and periodontal disease. Additionally, dietary habits and lifestyle factors can influence tooth wear and sensitivity, particularly among younger individuals. With the aging population, increased tooth wear may lead to a higher prevalence of dentin hypersensitivity2,3,4. Currently, there are multiple theories regarding the pathogenesis of dentin hypersensitivity, among which the hydrodynamic theory is widely accepted5. The hydrodynamic theory postulates that dentin hypersensitivity arises when external stimuli induce fluid movement within the dentinal tubules, leading to the activation of mechanoreceptors in the pulp and the perception of pain. Consequently, therapeutic approaches have focused on minimizing the transmission of such stimuli, modulating pulpal neural responses, and reducing overall nerve sensitivity as potential means to alleviate hypersensitivity symptoms6.

During clinical treatments such as periodontitis management and tooth preparation, dentinal tubules are often exposed, leading to dentin hypersensitivity. Currently, agents like Bifluorid12 are commonly used to alleviate sensitivity; however, their effectiveness is limited. Fluoride-based treatments aim to seal the dentinal tubules by forming a fluoride film. Unfortunately, this film is prone to wear and can be easily removed, causing a recurrence of sensitivity. Additionally, the eugenol in Bifluorid12 can scavenge free radicals but also inhibits resin polymerization, negatively affecting bonding7. Effective management of dentin hypersensitivity following periodontitis requires more than the mere occlusion of exposed dentinal tubules. Periodontal tissue loss resulting from disease progression or therapeutic interventions can lead to root surface exposure, leaving dentinal tubules vulnerable to external stimuli and bacterial contamination. Oral microorganisms and their metabolic by-products may penetrate these tubules through direct diffusion or via microleakage at the interface of restorative materials, potentially triggering pulpal inflammation and exacerbating sensitivity. Therefore, beyond physical sealing, it is imperative to inhibit bacterial ingress into the tubules to prevent further complications. A sealing material that simultaneously provides durable tubule occlusion and exhibits antimicrobial properties would be highly advantageous. Such dual-functionality not only contributes to sustained symptom relief but also plays a critical role in minimizing microbial challenges in the context of periodontal therapy. Consequently, antimicrobial activity should be considered a fundamental requirement in the development of novel dentin sealants for periodontal applications.

Nano-hydroxyapatite (nHA) has recently gained attention as a promising material for the management of dentin hypersensitivity, primarily due to its excellent biocompatibility, high surface area, and biomimetic mineralization capabilities. With particle sizes typically below 100 nm, nHA can effectively penetrate dentinal tubules, seal exposed tubule openings, and facilitate remineralization by releasing calcium ions (Ca²⁺) that interact with dentin matrix proteins8,9,10,11,12,13. These properties not only support its application in hard tissue regeneration but also enable its use as a drug delivery carrier, given its high drug-loading capacity and ability to release therapeutic agents in a controlled manner9.

In the context of periodontitis-associated dentin hypersensitivity, bacterial infiltration into exposed dentinal tubules poses an additional challenge. Periodontal pathogens such as Porphyromonas gingivalis, Actinomyces spp., Fusobacterium nucleatum, Prevotella intermedia, and Treponema denticola are known contributors to disease progression and post-treatment complications14. Among available antibiotics, Amoxicillin (AMX), a broad-spectrum β-lactam antibiotic, has demonstrated effective antimicrobial activity against P. gingivalis and other Gram-positive and Gram-negative organisms. Importantly, resistance to AMX remains relatively low, unlike the rising resistance observed for other antibiotic classes including tetracyclines and macrolides15,16,17,18.

Combining nHA with AMX provides a strategic advantage by integrating the remineralizing and tubule-sealing properties of nHA with the antimicrobial efficacy of AMX. This dual-function approach offers localized, sustained drug release at the dentin interface, potentially preventing bacterial colonization while simultaneously treating hypersensitivity. However, limited studies have investigated the synergistic application of nHA and AMX in managing dentin hypersensitivity under periodontal conditions.

Therefore, the present study aims to develop and evaluate an nHA–AMX composite material with both remineralization and antibacterial properties, specifically targeting P. gingivalis and addressing the clinical challenge of dentin hypersensitivity following periodontitis.

Carboxymethyl Cellulose (CMC) is an anionic cellulose ether obtained through the chemical modification of natural cellulose with chloroacetic acid. It exhibits excellent water solubility, emulsification, dispersion, water retention, and film-forming properties, making it valuable across various industries, including food, pharmaceuticals, and construction. In the medical field, CMC serves as a dispersant, thickener, suspending agent, and stabilizer, and is known to effectively prevent particle aggregation, maintain uniform suspensions, and support drug sustained-release19,20.Despite its limited mechanical strength and reduced stability in high-ionic or saline environments, CMC was selected in this study due to its favorable biocompatibility, aqueous solubility, and ability to uniformly disperse nano-hydroxyapatite (nHA). These features are particularly suitable for preparing localized drug delivery systems in non-load-bearing dental applications, where the mechanical demands are relatively low. By optimizing the CMC-to-nHA ratio, a stable AMX-loaded nHA suspension was successfully formulated. This composite harnesses the remineralization potential and drug-loading capacity of nHA, combined with the antibacterial effect of amoxicillin, to achieve effective dentinal tubules sealing and bacterial inhibition. The design aims to balance biological performance with sufficient stability for localized intraoral use, rather than for long-term structural reinforcement.

This study aims to investigate the potential application of a composite material composed of Carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC), Amoxicillin (AMX), and nano-hydroxyapatite (nHA) for the dual purpose of dentinal tubules occlusion and localized antibacterial therapy. By integrating the structural sealing capabilities of nHA, the antimicrobial efficacy of AMX, and the biocompatibility and gel-forming properties of CMC, the composite is expected to address both the physical and microbial factors contributing to dentin hypersensitivity, particularly in the context of periodontal disease. This research seeks to provide a scientific basis for the development of multifunctional therapeutic materials with potential clinical relevance in oral medicine.

Results

Standard calibration curve of amoxicillin (AMX)

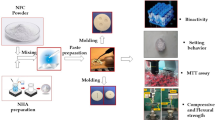

The overall experimental workflow, including material preparation and major analytical procedures, is illustrated in Fig. 1. As shown in Table 1; Fig. 2A and B, the peak area of Amoxicillin (AMX) obtained via high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) increased proportionally with increasing AMX concentration, indicating a strong linear correlation. The linear regression analysis yielded the Eq. (1):

Overview diagram of the experimental design and methodology.Schematic representation of the study workflow, including the preparation of the CMC/AMX/nHA composite material, characterization of its drug-loading and release performance, evaluation of cytocompatibility and hemocompatibility, antibacterial assays, as well as dentinal tubules sealing and bonding strength tests conducted on extracted human teeth.

AMX loading and release characterization. (A) Standard curve illustrating the relationship between Amoxicillin (AMX) concentration and peak area as measured by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). (B) Linear regression plot of AMX concentration versus peak area. The x-axis represents AMX concentration (mg/L), and the y-axis represents peak area. (C) Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectra of the respective samples, used to assess the interaction between AMX and nano-hydroxyapatite (nHA). (D) Cumulative drug release profile of AMX-loaded nHA over time, indicating the release kinetics of AMX from the composite material.

where y represents the peak area and x represents the AMX concentration (mg/L). The high correlation coefficient (R² = 0.9987) suggests excellent linearity across the tested concentration range (1–16 mg/L).

This regression equation was subsequently used to calculate the residual AMX concentration in the supernatant after loading onto nano-hydroxyapatite (nHA), which in turn was used to determine encapsulation efficiency.

Encapsulation efficiency of AMX in nHA carriers

Encapsulation efficiency (EE) refers to the percentage of a drug or active substance that is successfully loaded into a carrier system relative to the total amount of drug initially used21,22. In this study, different concentrations of AMX (1 g/L, 2 g/L, and 3 g/L) were mixed with 1 g of nano-hydroxyapatite (nHA) to determine the optimal drug-to-carrier ratio. After loading, the supernatants were collected, filtered, and analyzed using high-performance liquid chromatography to determine the concentration of unencapsulated AMX. The encapsulation efficiency was calculated using the Eq. (2):

As shown in Table 2, the 2 g/L AMX and 1 g/L nHA group exhibited the highest encapsulation efficiency. Therefore, this ratio was selected as the optimal combination for subsequent experiments.

Optimization of the CMC/nHA ratio in composite preparation

In this study, Carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) was utilized as a dispersant to suspend the water-insoluble nano-hydroxyapatite (nHA), thereby improving its dispersion stability and facilitating its adhesion to the dentin surface. This settling process plays a critical role in promoting dentin remineralization and effectively sealing dentinal tubules, which can help alleviate dentin hypersensitivity.

To identify the optimal CMC concentration for suspending nHA, three different amounts of CMC (0.5 g, 1 g, and 2 g) were each dissolved in 1 L of deionized water. Then, 1 g of nHA was added to each solution, and the suspensions were stirred and ultrasonically treated as described in Sect. 2.2.3. The degree of precipitation was visually evaluated over time to determine dispersion stability.

Based on the results summarized in Table 3, a 1:1 mass ratio of nHA to CMC exhibited the most favorable suspension characteristics and minimal precipitation within the observation period. Therefore, this ratio was selected for subsequent preparation of the composite material.

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy of composite materials

The Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectra of Amoxicillin (AMX), Nano-Hydroxyapatite (nHA), and AMX-loaded nHA were obtained to evaluate their structural characteristics. According to the Chinese Pharmacopoeia, AMX exhibits characteristic absorption bands corresponding to its functional groups. In the FTIR spectrum of pure AMX, prominent peaks were observed around 1750–1800 cm⁻¹ (β-lactam ring Carbonyl group), 3300 cm⁻¹, 1525 cm⁻¹, and 1680 cm⁻¹ (secondary amido and Carbonyl groups), and 1600 cm⁻¹ and 1410 cm⁻¹ (Carboxylate ion).

The spectrum of nHA (Fig. 2C) showed distinctive peaks at 560 cm⁻¹, 600 cm⁻¹, and 1022 cm⁻¹, which correspond to phosphate group vibrations typical of hydroxyapatite.

In the spectrum of the AMX-loaded nHA composite, the characteristic phosphate peaks of nHA remained present. Additionally, new peaks appeared at 1245 cm⁻¹ and 1770 cm⁻¹, which were not present in the spectra of either pure AMX or pure nHA. These spectral changes suggest the presence of AMX-related functional groups in the composite material.

In vitro drug release profile of CMC/AMX/nHA composite

The release rate of AMX from the CMC/AMX/nHA composite was quantitatively analyzed using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). The drug release profile over a 24-hour period is summarized in Table 4 and visualized in Fig. 2D.

The cumulative release of AMX showed a time-dependent increase during the first 8 h. At 20 min (1/3 h), the release rate was 0.30%, and at 40 min (2/3 h), it increased to 0.33%. By 1 h, the cumulative release reached 0.34%. A continued increase was observed at 2 h (0.37%) and 4 h (0.47%). At 6 h and 8 h, the release rates were 0.58% and 0.66%, respectively, indicating that the majority of the drug was released within the first 8 h. After this peak, the release rate plateaued, with values of 0.64% at 10 h, 0.65% at 12 h, and 0.65% at 24 h.

Statistical analysis using one-way ANOVA indicated a significant increase in cumulative AMX release during the first 8 h (p < 0.05). However, no statistically significant differences were observed between 8 h and subsequent time points (p > 0.05), suggesting that the release had stabilized.

These results demonstrate a biphasic drug release profile characterized by an initial rapid release phase followed by a stable plateau. This release behavior is advantageous for localized drug delivery systems, offering an early antimicrobial burst followed by sustained therapeutic levels over time.

Cytotoxicity evaluation via CCK-8 assay

The cytocompatibility of the composite materials was evaluated by measuring the proliferation of human periodontal ligament stem cells (hPDLSCs) co-cultured with CMC/nHA and CMC/AMX/nHA suspensions using the CCK-8 assay on Days 1, 2, and 3. The blank group served as the control. As shown in Table 5; Fig. 3A, all groups exhibited a time-dependent increase in OD values, indicating continuous cell proliferation.

Biocompatibility evaluation of CMC/AMX/nHA composite. (A) CCK-8 assay results showing the absorbance values of periodontal ligament stem cells cultured with different materials, indicating cell viability. (B) Hemolysis test results evaluating the blood compatibility of the composite material. (C) Live/dead staining images of periodontal ligament stem cells after 2 days of culture, assessing cytocompatibility through fluorescent labeling of viable and non-viable cells.

No significant differences in OD values were found among the groups at each time point (P > 0.05), suggesting that the incorporation of AMX and CMC did not adversely affect hPDLSC viability. However, the OD values increased significantly over time within each group (P < 0.01), demonstrating good cytocompatibility of all tested materials.

These findings indicate that both CMC/nHA and CMC/AMX/nHA composites support hPDLSC proliferation and exhibit low cytotoxicity, highlighting their potential for dentin tubule sealing and antibacterial treatment.

Live/Dead staining of periodontal ligament stem cells

Live/dead staining was performed to visually assess the cytocompatibility of the materials. After co-culture with CMC/nHA and CMC/AMX/nHA for 1, 2, and 3 days, human periodontal ligament stem cells (hPDLSCs) were stained using Calcein-AM (green, live cells) and propidium iodide (PI, red, dead cells), and imaged under a fluorescence microscope.

As shown in Fig. 3C cells in all groups displayed strong green fluorescence with minimal red fluorescence, indicating high cell viability. No obvious morphological abnormalities or increased cell death were observed in the material-treated groups compared to the blank control group at any time point.

These results visually confirm that both composite materials exhibit good biocompatibility and do not induce significant cytotoxicity in hPDLSCs over a 3-day culture period.

Hemocompatibility evaluation through hemolysis testing

To evaluate the blood compatibility of the materials, hemolysis tests were performed on both drug-loaded (CMC/AMX/nHA) and non-drug-loaded (CMC/nHA) nano-hydroxyapatite suspensions. As observed under the microscope, red blood cells in the negative control, CMC/nHA, and CMC/AMX/nHA groups retained their characteristic biconcave disc morphology with smooth, intact, and uniformly distributed membranes. In contrast, the positive control group exhibited extensive hemolysis, with most red blood cells showing signs of rupture or fragmentation, leaving only residual membrane debris.

Quantitative analysis of the hemolysis rate (Table 6; Fig. 3B showed that the CMC/nHA and CMC/AMX/nHA groups had mean hemolysis rates of 0.170% and 0.191%, respectively, both well below the 5% threshold set by the national standard for medical device safety. In comparison, the positive control group exhibited a hemolysis rate exceeding 1.6%, confirming the test’s validity. These results demonstrate that the developed composite materials possess excellent hemocompatibility and are safe for further biomedical applications.

Antibacterial activity assessed by Inhibition zone assay

As shown in Fig. 4A, filter paper disks were used to assess the antibacterial activity of the composite material against Porphyromonas gingivalis. In sample A, where the filter paper was soaked in the CMC/AMX/nHA suspension, a distinct inhibition zone was observed surrounding the disk, indicating effective antibacterial activity. In contrast, sample B, consisting of a blank filter paper under identical culture conditions, showed no inhibition zone, confirming the reliability of the medium and the absence of contamination.

Antibacterial efficacy of CMC/AMX/nHA composite against Porphyromonas gingivalis. (A) Inhibition zone measurement chart showing the antibacterial halo diameter produced by each group. (B) Quantitative analysis of bacterial colony counts in each group after co-culture. Note: “**” indicates a significant difference compared to the control group; “##” indicates a significant difference compared to the experimental group.

These results demonstrate that the CMC/AMX/nHA composite can successfully release Amoxicillin in a biologically active form, thereby inhibiting the growth of P. gingivalis. This confirms the material’s potential for localized antibacterial treatment in dental applications.

Quantitative antibacterial activity via bacterial colony counting

The antibacterial efficacy of the materials was further evaluated through bacterial colony counting after co-culture with Porphyromonas gingivalis. The number of colonies on each culture plate was quantified using ImageJ software, and the results are presented in Fig. 4B.

Compared to the control group, both the CMC/AMX/nHA composite and the Minocycline hydrochloride ointment (New Era Co., Ltd, Japan) significantly reduced the number of bacterial colonies. Notably, the CMC/AMX/nHA group exhibited antibacterial performance comparable to that of Minocycline, indicating that the incorporation of Amoxicillin into the nano-hydroxyapatite matrix provides effective suppression of P. gingivalis growth. This finding further supports the material’s potential as a localized antibacterial agent for dental applications.

Dentinal tubule occlusion assessment by SEM

As shown in Fig. 5A, the blank control group exhibited a smooth dentin surface with numerous open, round dentinal tubules, indicating its natural unsealed state. Similarly, the Minocycline Hydrochloride group showed a comparable surface morphology, with no evident mineral deposition or sealing effect. In contrast, the surfaces treated with CMC/AMX/nHA and Bifluoride 12 (VOKO GmbH, Germany) displayed partial occlusion of dentinal tubules, where barrier-like deposits covered or narrowed the tubule orifices, indicating effective but incomplete sealing. Quantitative analysis of exposed tubules per unit area (Table 7; Fig. 5B) revealed that the number of exposed dentinal tubules in the CMC/AMX/nHA group (43.4 ± 8.96) was significantly lower than that in the blank control group (297.8 ± 52.18) and the Minocycline Hydrochloride group (288.6 ± 42.47) (P < 0.001). The Bifluoride 12 group also showed a significantly reduced tubule count (96.6 ± 18.49) compared to the blank and Minocycline groups (P < 0.001), though its sealing effect was not as pronounced as that of the CMC/AMX/nHA group. No significant difference was observed between the blank and Minocycline Hydrochloride groups, confirming the latter’s inability to induce dentinal tubules occlusion. These findings indicate that both CMC/AMX/nHA and Bifluoride 12 can effectively reduce dentinal tubules exposure, with CMC/AMX/nHA demonstrating superior sealing performance.

Evaluation of dentin tubule sealing and bonding performance of CMC/AMX/nHA composite. (A) Representative SEM images of dentin disc surfaces in each group, showing differences in dentinal tubules exposure. (B) Statistical histogram of the number of exposed dentinal tubules per unit area. (C) Fluorescence-based microleakage detection diagram. (D) Bar chart showing the bonding strength of resin to dentin in each group. (E) Schematic representation of fracture modes observed after bond strength testing. (F) Distribution ratio of different fracture modes across groups. Note: Images A (a–d) are SEM micrographs at 3000× magnification; images A (e–h) are SEM micrographs at 10,000× magnification. “**” indicates a significant difference compared to the control group; “##” indicates a significant difference compared to the experimental group.

Microleakage evaluation of dentin sealing

Laser confocal microscopy was employed to assess the microleakage and adhesive penetration into dentinal tubules by visualizing Rhodamine B dye infiltration. As shown in Fig. 5C, in the blank control group, Rhodamine B fluorescence penetrated deep into the dentinal tubules, indicating substantial dye infiltration and absence of sealing.

In contrast, both the CMC/AMX/nHA and Bifluorid 12 groups exhibited partial blockage of tubules, with markedly reduced dye penetration in treated areas. This suggests that the application of desensitizing agents formed a barrier layer over some tubule openings, effectively limiting dye ingress23. However, uneven distribution or incomplete sealing allowed localized penetration in certain regions, indicating that while the sealing effect was evident, it was not uniformly achieved across the entire surface.

These observations demonstrate that the CMC/AMX/nHA composite can effectively reduce microleakage, though further optimization may be needed to achieve more consistent dentinal tubules sealing.

Bond strength of composite material to dentin

The micro-shear bond strength of dentin was evaluated for three groups: the blank control group, the CMC/AMX/nHA-treated group, and the Bifluoride 12 group. Each group included 20 samples, and results are summarized in Table 8 and illustrated in Fig. 5D.

The mean bond strengths were 23.48 ± 4.37 MPa for the blank group, 23.36 ± 4.97 MPa for the CMC/AMX/nHA group, and 14.94 ± 1.78 MPa for the Bifluoride 12 group. Statistical analysis revealed no significant difference between the CMC/AMX/nHA group and the blank group (P > 0.05), indicating that the incorporation of CMC/AMX/nHA did not impair adhesive bonding performance. In contrast, the Bifluoride 12 group exhibited a significantly lower bond strength compared to both the blank group and the CMC/AMX/nHA group (P < 0.001; F = 30.587).

These findings suggest that while Bifluoride 12 may compromise the adhesive interface, the CMC/AMX/nHA composite preserves bonding integrity and is more compatible with adhesive procedures.

Fracture pattern analysis following bond strength testing

Fracture patterns observed after the micro-shear bond strength test were categorized into three types: Mode A (adhesive failure at the bonding interface), Mode B (cohesive failure within the material or dentin), and Mode C (mixed failure). Among these, Mode A is generally considered the most representative mode for evaluating true bond strength.

As illustrated in Figs. 5E and F, more than 70% of the samples exhibited Mode A fractures across all groups, indicating that most failures occurred at the adhesive interface. This high proportion of Mode A failures suggests that the bond strength measurements in this.

study were reliable and not confounded by cohesive material failure.

Discussion

This experiment aims to utilize the significant loading capacity of Nano-Hydroxyapatite (nHA) as a carrier to deliver Amoxicillin, which can then be locally released to inhibit bacterial growth. The inhibition zone results from CMC/AMX/nHA confirm that Amoxicillin can be effectively released and inhibits the growth of Porphyromonas gingivalis (P. gingivalis). Additionally, plate count results following co-culture with P. gingivalis further demonstrate that Amoxicillin-loaded nHA exhibits antibacterial effects comparable to Minocycline Hydrochloride ointment. It is noteworthy that Bifluorid 12 contains eugenol, an aromatic oil extracted from clove, widely used as a flavoring agent in food and tea and as a topical treatment for toothaches. Eugenol possesses antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant properties24,25,26,27,28,29. However, in this experiment, Bifluorid 12 did not exhibit inhibition of P. gingivalis, and the reason for this remains unclear. It is hypothesized that the concentration may not have reached the minimum inhibitory concentration for P. gingivalis.

This study only verified the antibacterial effects of the experimental groups in vitro. However, the oral environment is a highly complex and open microecosystem30. The local microenvironment is influenced by multiple factors, such as pH, redox potential, interactions between various bacteria (e.g., symbiosis, competition, dependency, and antagonism), and the patient’s oral hygiene. These factors can affect bacterial adhesion and colonization31,32. Therefore, further in-depth studies are needed to observe the antibacterial efficacy of CMC/AMX/nHA.

Regarding dentinal tubules occlusion, during the cutting process, dentin debris may block the tubules, which may differ from the condition in dentin-sensitive patients. Hence, a dentin sensitivity model needs to be established. Typically, acid etching is used to remove the smear layer and open the dentinal tubules, using agents like 37% or 35% phosphoric acid or 17% EDTA33. Studies have shown that etching dentin with 35% phosphoric acid for 30 s results in a smear layer-free surface with clearly opened dentinal tubules under SEM, without enlargement of the tubule orifices. Therefore, 35% phosphoric acid was used in this study to establish the dentin sensitivity model34.

The most common treatment for dentin hypersensitivity and related pain is to occlude exposed dentinal tubules, thereby reducing dentin permeability and preventing rapid fluid movement. After observing the surface morphology and counting the exposed dentinal tubules in each treatment group, both Bifluorid 12 and CMC/AMX/nHA groups showed good dentinal tubules occlusion effects, while no significant differences were observed between the Minocycline Hydrochloride and control groups.

The desensitizing effect of Bifluorid 12 is achieved through its fluoride content, which forms an inorganic covering layer on the dentin surface and penetrates into the dentinal tubules to block them35. Nano-Hydroxyapatite, deposited on the surface of dentin in vitro, increases calcium ion concentration in saliva, thereby reaching a state of mineral saturation on the dentin surface, reducing demineralization, promoting remineralization, and occluding dentinal tubules to minimize irritation to the dental pulp nerves36. However, some researchers have pointed out that the state of dentinal tubules occlusion or opening may influence bonding strength in adhesive restorations37. Since both Bifluorid 12 and CMC/AMX/nHA treatments resulted in dentinal tubules occlusion, this could potentially affect the bonding strength, so bonding strength tests were conducted in this study.

The bonding strength test method measures the bonding strength on a smaller area to minimize interference from interface defects and reduce the likelihood of cohesive failure, yielding more accurate results. Micro-shear bond strength tests are widely used to assess the bonding strength of dentin adhesives and are correlated with clinical outcomes. This study tested the change in resin bonding strength after different treatments of dentin38,39.

Self-etching adhesives contain functional acidic monomers such as 10-methacryloyloxydecyl dihydrogen phosphate (10-MDP), whose chemical interaction with dental hard tissues determines the bonding interface morphology and the quality of the hybrid layer40. The bonding process to dentin involves the infiltration of the adhesive monomer into dentinal tubules and the collagen network, forming micro-mechanical locks, with the bonding force mainly originating from these micro-mechanical interlocks.

Bifluorid 12 contains fluoride ions that deposit on the dentin surface. When the pH value decreases, fluoride ions are released, inducing the formation of fluorapatite (FA) or fluorohydroxyapatite (FHA), which replace OH− and reduce acid solubility41,42. Conversely, when the pH value increases, fluoride ions contribute to the formation of minerals and promote remineralization43. However, the hydrophobic layer formed on the dentin surface may affect the quality of the hybrid layer, reducing the depth of adhesive penetration and thereby decreasing bonding strength. Additionally, eugenol, a free radical scavenger present in Bifluorid 12, may interfere with the polymerization of the resin, further impacting the bonding effect44.

Nano-Hydroxyapatite (nHA) also may reduce the depth of adhesive infiltration, but the chemical bonding between 10-MDP and calcium enhances the bonding strength45. nHA increases the surface energy of dentin, enhancing the interaction between the dentin and adhesive, improving surface wettability, and thereby increasing bonding strength46. Moreover, nHA can effectively occlude dentinal tubules, reducing microleakage47 and improving the long-term stability of restorations, thus preventing secondary caries. Therefore, nHA did not decrease the bonding strength of dentin-resin interfaces.

Although this study demonstrates the potential of nano-hydroxyapatite (nHA) in promoting dentin remineralization in an ex vivo model, several limitations must be acknowledged. Dentin is a highly complex, collagen-mineralized tissue composed of approximately 70% carbonate apatite and 30% organic components, including collagen, non-collagenous proteins (NCPs), and water. These organic constituents, particularly NCPs such as dentin matrix protein 1 (DMP1) and dentin phosphoprotein (DPP), are known to regulate nucleation and guide the organized growth of hydroxyapatite crystals48. Since this experiment was conducted in vitro using a simplified dentin model, it does not fully replicate the intricate biological interactions present in vivo, such as the roles of odontoblasts, saliva, enzymatic activity, and immune responses. Consequently, while our findings indicate that nHA-containing materials can partially occlude dentinal tubules and initiate mineral deposition, their actual performance in the oral environment remains to be validated.

Previous studies have reported similar findings regarding the bioactivity of nHA, particularly its ability to serve as a calcium and phosphate ion reservoir, facilitating mineral deposition under acidic condition49. However, most of these studies also emphasize the importance of biomimetic conditions and the presence of matrix proteins for achieving organized remineralization. Our results align with these observations but further highlight that full tubule occlusion was not achieved, which may limit the desensitization efficacy in clinical scenarios. Interestingly, the CMC/AMX/nHA group demonstrated comparable or better tubule sealing and antimicrobial effects than traditional fluoride-based desensitizers like Bifluoride 12, suggesting that this composite may provide dual benefits in managing dentin hypersensitivity and bacterial infection.

Moreover, the study did not include thermocycling or mechanical aging tests, which are crucial for assessing the long-term durability of dentin-resin bonds after desensitization. Future studies should involve animal models and long-term clinical simulations to validate these materials’ remineralization and antimicrobial capabilities under dynamic oral conditions. In particular, incorporating in vivo biofilm models and assessing the materials’ effects on dentin sensitivity and bond durability over extended periods would provide more clinically relevant evidence50. Additionally, exploring the integration of other bioactive agents may further enhance the functional remineralization capacity of these materials.

In conclusion, although the current in vitro data suggest that CMC/AMX/nHA composites offer promising biocompatibility, antibacterial activity, and potential remineralization effects, further research is essential to bridge the gap between bench and bedside. Addressing these limitations will be critical for advancing their clinical application in dentin hypersensitivity management and restorative dentistry.

Conclusion

CMC/AMX/nHA composite was successfully developed using an optimized AMX concentration (2 g/L) and an nHA-to-AMX mass ratio of 2:1 within a 1 g/100 mL CMC dispersion. This formulation ensured efficient drug loading and sustained release. The composite demonstrated dentinal tubules sealing efficacy comparable to Bifluoride 12 and antibacterial performance equivalent to Minocycline Hydrochloride. Importantly, it did not compromise resin bond strength. These results indicate that CMC/AMX/nHA is a biocompatible, antimicrobial, and restorative-compatible material with strong potential for clinical use in dentin desensitization and localized antibacterial therapy.

Materials and methods

Collection and storage of extracted teeth and periodontal tissue samples

The present study was approved by the Human Ethics Committee of the School of Stomatology and Stomatological Hospital of Southwest Medical University (Approval Number 20220806220). and performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

A total of 78 freshly extracted third molars within 6 months were selected. The extracted teeth were obtained from the Affiliated Stomatological Hospital of Southwest Medical University. The teeth were thoroughly rinsed with saline, the periodontal ligament and dental calculus were removed, and the teeth were placed in a 1% Chloramine T solution (Loster Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, Shan Tou, China) and stored in a refrigerator at 4 °C. Inclusion criteria: teeth with no caries, no hidden fractures, no history of dental treatments, and no systemic diseases. Exclusion criteria: carious teeth, teeth previously treated with resin fillings, teeth that have undergone root canal treatment, congenital syphilitic teeth, congenital enamel hypoplasia, dentin dysplasia, tetracycline-stained teeth, and fluorosis-stained teeth.

A total of 10 extracted premolars from patients aged 13–18 requiring orthodontic treatment were collected, along with the periodontal ligament tissue. The freshly extracted teeth and periodontal ligament tissues were placed in a centrifuge tube containing a collection solution (1× PBS (Solarbio, Beijing, China) supplemented with 10% penicillin and streptomycin). The samples were soaked in the solution, temporarily stored at low temperature, and promptly transported to the laboratory for further processing. Inclusion criteria: Individuals with no adverse lifestyle habits, no special medication history, no systemic diseases, no periodontal diseases, and no high-risk conditions for inducing periodontal inflammation. Exclusion criteria: Periodontitis, gingivitis, caries, serious systemic diseases, etc.

Preparation and validation of the AMX standard calibration curve

Amoxicillin (Meirui, China) powder was accurately weighed using an electronic balance(Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Serial concentrations of 1 mg/L, 2 mg/L, 4 mg/L, 8 mg/L, and 16 mg/L were prepared by dissolving the corresponding masses of Amoxicillin in deionized water under magnetic stirring until fully dissolved. Each solution was subsequently analyzed using a high-performance liquid chromatograph (HPLC) system (Agilent Technologies, Inc., USA). A standard calibration curve was established by plotting the peak area against the known concentrations of Amoxicillin, and the corresponding linear regression equation was obtained.

Determination of AMX encapsulation efficiency in nHA

Three portions of 1 g nano-hydroxyapatite (nHA) (Shark Biotech Co., Ltd, China) were weighed and added to three Amoxicillin solutions with concentrations of 1 g/L, 2 g/L, and 3 g/L, respectively. The mixtures were stirred at 500 rpm for 24 h at room temperature. After incubation, the suspensions were centrifuged using a high-speed centrifuge (Zhong Jia, Shenzhen, China), and the supernatants were collected for subsequent analysis. The resulting precipitates, consisting of Amoxicillin-loaded nano-hydroxyapatite, were transferred to a freezer at − 20 °C (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) for 4 h and then freeze-dried for 4 h to obtain dry Amoxicillin-loaded nHA powder.

The supernatants from the three preparations were filtered and analyzed using a high-performance liquid chromatograph (Agilent Technologies, Inc., USA) to determine the concentrations of unencapsulated Amoxicillin based on the previously established standard curve. The encapsulation efficiency was calculated using the Eq. (3):

The optimal ratio of Amoxicillin to nano-hydroxyapatite was determined based on the highest encapsulation efficiency, which reflected the highest percentage of Amoxicillin successfully loaded onto the nano-hydroxyapatite.

Screening for the proportion of Nano-Hydroxyapatite and carboxymethyl cellulose

Carboxymethyl Cellulose (CMC) (Huimu Biotechnology Co., Ltd, China) powders (0.5 g, 1 g, and 2 g) were each dissolved in 1 L of deionized water under magnetic stirring until completely dissolved. Subsequently, 1 g of nano-hydroxyapatite (nHA) was added to each of the three CMC solutions. The mixtures were stirred at 500 rpm for 15 min at room temperature and then subjected to ultrasonic treatment using an ultrasonic cleaner (Dekang Medical Equipment Co., LTD, China) for 30 min. The resulting nHA suspensions with different CMC concentrations were allowed to stand, and sedimentation behavior was visually observed to assess dispersion stability.

Based on the results of the encapsulation efficiency experiment, the concentration of Amoxicillin and nano-hydroxyapatite that showed the highest drug-loading efficiency was selected. Additionally, the CMC concentration that exhibited the most stable suspension (i.e., minimal sedimentation over time) was chosen. Using these optimized conditions, CMC/AMX/nHA composites were prepared by dispersing the Amoxicillin-loaded nHA into the selected CMC solution, followed by magnetic stirring and ultrasonic mixing as described above.

FTIR characterization of composite material

2.0 mg of nHA, AMX, and Amoxicillin-loaded nano-hydroxyapatite were each weighed and placed into a clean mortar. Then, 150 mg of potassium bromide (KBr) powder was added to each sample. The mixtures were thoroughly ground and homogenized into fine powders, then compressed into uniform thin pellets using a manual tablet press. The prepared KBr pellets were subsequently analyzed using a Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectrometer to investigate the chemical structures of the materials.

In vitro AMX release assay (24-hour cumulative release)

A total of 0.10 mL of CMC/AMX/nHA composite suspension was added to 100 mL of 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution and incubated at a constant temperature. Samples were collected at the following time intervals: 20 min, 40 min, 1 h, 2 h, 4 h, 6 h, 8 h, 10 h, 12 h, and 24 h. At each time point, 1.00 mL of the supernatant was carefully withdrawn, filtered through a 0.22 μm disposable syringe filter, and transferred into a liquid chromatography sampling vial (Aijiren, zhejiang, China) for analysis.

An equal volume of fresh 1× PBS was added to maintain a constant total volume. The collected samples were analyzed using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) under the same conditions as previously described. The Amoxicillin concentration was calculated based on the standard curve, and the cumulative drug release rate was determined. A drug release profile curve was then plotted to visualize the release kinetics over 24 h.

Isolation and culture of periodontal ligament stem cells

In a cell culture laminar flow cabinet (Laminar Flow Hood, Li Shen, China), the periodontal ligament tissue was cleaned with the collection solution until it turned white, and then placed in a dish containing complete medium. Using a sterile periodontal curette, the periodontal ligament tissue from the middle third of the root was scraped and placed in a centrifuge tube containing 20% FBS (Vincent Biotechnology Co., Ltd, Nan jing, China) complete medium. The tube was centrifuged at 800 rpm for 5 min using a low-speed centrifuge. The periodontal ligament tissue at the bottom was aspirated using a Pasteur pipette and transferred to the bottom of a culture flask. The culture flask was inverted, and 3 mL of complete medium containing 20% FBS was added. The flask was then placed in a 37 °C, 5% CO₂ incubator. Once the tissue adhered to the bottom of the flask, the flask was returned to its normal position. The culture medium was changed every 3 days, and the growth of cells around the tissue block was observed.

Once the primary cells reached approximately 80% confluence, the culture medium was aspirated, and the cells were washed twice with 1×PBS solution containing 1% penicillin and streptomycin. Then, 1.5 mL of 0.25% trypsin was added to digest the cells in the incubator. The digestion process was monitored under an inverted microscope. When extensive cytoplasmic retraction and cell rounding were observed, digestion was terminated. Immediately, 1.5 mL of complete medium was added to stop the digestion. The cells were gently pipetted, mixed, and transferred to a sterile centrifuge tube. The tube was sealed, balanced, and centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 5 min. The supernatant was aspirated, and a complete culture medium containing 10% FBS was added to the cell pellet. The cells were resuspended by pipetting, and mixed thoroughly, and the cell count was determined using a hemocytometer. The cells were then seeded into 25 cm² culture flasks at a density of 1 × 10⁶ cells/mL for subculture and storage.

CCK-8 cytotoxicity assay

After ultraviolet (UV) irradiation for 1 h in a sterile laminar flow cabinet, CMC/nHA and CMC/AMX/nHA were mixed with α-MEM culture medium to form suspensions. The above-mentioned subcultured periodontal ligament stem cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 2 × 10⁴ cells/well, and incubated for 24 h in a cell incubator. Once the cells adhered well, the original culture medium was discarded, and a culture medium containing CMC/nHA and CMC/AMX/nHA was added (100 µL/well, 3 replicate wells per group). After 1, 2, and 3 days of culture, the experiment was terminated, and cells were washed with PBS. Then, 100 µL of α-MEM medium and 10 µL of CCK8 solution were added to each well, followed by 1 h incubation. Absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a microplate reader.

Live/Dead cell staining of periodontal ligament stem cells

After UV irradiation for 1 h, CMC/nHA and CMC/AMX/nHA were mixed with α-MEM culture medium to form suspensions. The above-mentioned subcultured periodontal ligament stem cells were seeded into 24-well plates at a density of 3 × 10⁴ cells/well and incubated for 24 h. Once the cells adhered well, the culture medium was replaced with a medium containing CMC/nHA and CMC/AMX/nHA (500 µL/well, 3 replicate wells per group). After 1, 2, and 3 days of culture, the experiment was terminated, and the cells were washed with PBS. Then, the prepared animal cell viability/toxicity assay reagent (5 µL of 4 mM Calcein AM and 30 µL of 1.5 mM PI added to 10 mL serum-free culture medium) was added. The cells were incubated for 20 min at 37 °C in a cell culture incubator, protected from light. After staining, the cells were observed and photographed under a fluorescence microscope. Live cells were stained green, while dead cells were stained red.

Hemolysis assay for blood compatibility

A total of 20 mL of 3.2% sodium citrate solution was prepared in a sterile centrifuge tube for anticoagulation. Fresh whole blood was obtained from the heart of a healthy New Zealand white rabbit using a sterile syringe and immediately transferred into a sterile vacuum blood collection tube(Saidejie Trading Co., Ltd. ShenZhen, China) pre-filled with 3.2% sodium citrate anticoagulant (Sbibio Biotechnology Co., Ltd.,NanJing, China). The collected blood was gently inverted several times to ensure complete mixing with the anticoagulant and was promptly transported to the laboratory under cooled conditions (4 °C) within 30 min.

The blood was centrifuged at 1200 rpm for 10 min at room temperature. The plasma supernatant was carefully removed and discarded. The remaining red blood cells were washed three times with sterile 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4), centrifuging at 1200 rpm for 10 min each time. Washing was repeated until the supernatant appeared clear and free of residual plasma.

The purified red blood cells were then resuspended in PBS and stored at 4 °C for no more than 24 h prior to use in the hemolysis test. The red blood cells were subsequently divided into four experimental groups as shown in Table 9.

In each group, 500 µL of diluted red blood cell solution and 1 mL of 1xPBS solution were added. All samples were incubated in a 37 °C constant temperature shaker for 1 h. Then, the samples were centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 5 min. The supernatant was collected and transferred to a 96-well plate. The absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 545 nm using a microplate reader. The hemolysis rate was calculated using the Eq. (4), and the results were interpreted as follows: a hemolysis rate of less than 5% indicates no cytotoxicity.

Equation (4):

Preparation of P. gingivalis culture for antibacterial testing

A total of 38.5 g of BHI powder was weighed and added to 1 L of deionized water in two separate flasks, labeled as Solution A and Solution B, respectively. To Solution A, 15.0 g of agar (Beijing Dongge Boye Biotechnology Co., Ltd, BeiJing, China) was added as a solidifying agent. Both solutions were stirred to dissolve completely and then sterilized using an autoclave at 121 °C for 20 min.

After sterilization, Solution B was cooled to room temperature and stored at 4 °C until use. Solution A was poured into sterile Petri dishes before solidification to prepare solid culture plates. Once solidified, the BHI agar plates were sealed and stored at 4 °C for later use.

The cryopreserved Porphyromonas gingivalis strain (Youli Biotechnology Co., Ltd, Shen Zhen, China) was thawed at room temperature and immediately transferred into BHI liquid medium supplemented with hemin and vitamin K1. The culture was then incubated in an anaerobic culture box (Zhode Scientific Instrument Co., Ltd., China) under anaerobic conditions composed of 80% N₂, 10% H₂, and 10% CO₂ at 37 °C for 24–48 h.

Antibacterial zone of Inhibition assay

A total of 0.1 mL each of CMC/AMX/nHA and CMC/nHA formulations was prepared and dissolved in 1×PBS solution. Sterile paper discs were fully soaked in the respective solutions.

P. gingivalis suspension was evenly spread on BHI agar plates. The soaked discs were then aseptically placed onto the surface of the inoculated agar. The plates were incubated under anaerobic conditions at 37 °C for 24 h. After incubation, the diameters of the inhibition zones around the discs were measured to evaluate the antibacterial activity of the samples.

Bacterial plate counting assay

In a bacterial ultra-clean workstation, 24 dentin disc specimens prepared as described above were selected. Both sides of the specimens were subjected to ultraviolet (UV) disinfection for 30 min to avoid bacterial contamination. The specimens were then randomly divided into 4 groups, with 6 samples in each group. The grouping and treatment methods are the same as described in Table 10.

100 µL of Porphyromonas gingivalis was absorbed and resuscitated, placed in 96 Wells, and absorbance was measured at 600 nm. The OD value was 1, corresponding to 108 bacteria. Porphyromonas gingivalis were diluted to 105, then the bacteria were customized into the 24-well plate and cultured in a bacterial anaerobic incubator for 24 h.

After 24 h of incubation, the 24-well plate was removed and placed in a sterile laminar flow cabinet,. From each well, 100 µL of the culture medium was collected and serially diluted to 10⁴-fold using sterile 1×PBS. A 100 µL aliquot of each dilution was dropped onto the center of a BHI agar plate and evenly spread using a sterile spreader. The plates were then incubated anaerobically at 37 °C for 24 h. Colony-forming units (CFUs) were counted to evaluate the bacterial growth.

SEM-based assessment of dentinal tubule sealing

To prepare the specimens, 48 teeth were fixed in a Gypsum cast (Heraeus Holding GmbH, Germany) exposing the crown above the neck. With continuous cold water irrigation, a cutting machine (Longxiang Optoelectronics Technology Co., Ltd., China)was used to slice off the occlusal enamel perpendicular to the tooth axis, exposing the dentin. We then made a horizontal cut 1 mm below the exposed dentin to create a 1 mm thick dentin disc. The crown surface served as the experimental surface. These discs were polished with 800 then 600 grit sandpaper, rinsed with deionized water for 60 s, subjected to ultrasonic agitation in deionized water for 30 min, and rinsed again for 60 s to prepare the dentin disc specimens.

Twenty-four samples of the above dentin discs were selected. The experimental surface was etched with 35% phosphoric acid for 30 s to open the dentinal tubules, then rinsed with deionized water, and the surface moisture was absorbed using filter paper. The 24 samples were randomly divided into 4 groups, with 6 samples in each group. The grouping and processing methods are listed in Table 10. The samples were then placed in a 24-well plate, with 1 mL of artificial saliva (Phygene Biotechnology Co., Ltd, China) added to each well. The procedure was repeated twice a day at 12-h intervals for 14 consecutive days.

For scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis, three dentin disc samples from each group were randomly selected and subjected to gradient dehydration using ethanol solutions of 30%, 40%, 50%, 75%, 80%, and 95% (v/v), followed by two immersions in 100% anhydrous ethanol. After air-drying, all samples were sputter-coated with gold to enhance surface conductivity. SEM imaging was performed using an Inspect F50 field emission scanning electron microscope (FEI, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) at an accelerating voltage of 15 kV.

Bond strength test via universal testing machine

Thirty extracted teeth had their enamel removed from the crown to expose the smooth dentin surface, following the same method as described above. The dentin surface was then etched with 35% phosphoric acid (Heraeus Holding GmbH, Germany) for 30 s. The teeth were subsequently randomly divided into three groups for dentin surface treatment, with the grouping as Table 11.

Three dentin discs (1 mm thick) were selected from each experimental group for microleakage assessment. A 1% Rhodamine B (Yeyuan, Biotechnology Co., Ltd, China) staining solution was prepared by dissolving 1 g of Rhodamine B in 100 mL of deionized water. The samples were immersed in the staining solution under dark conditions for 1 h.

After staining, excess dye was blotted off with filter paper, and the surfaces were rinsed gently with deionized water to remove residual impurities. Each disc was then sectioned longitudinally along the tooth axis using a precision cutting machine (Longxiang Optoelectronics Technology Co., Ltd., China). The sectioned surfaces were polished with silicon carbide abrasive paper (grit #600–#800) to remove surface irregularities. Finally, the polished samples were mounted onto microscope slides and examined under a laser confocal microscope (Nikon, Japan) to evaluate dye penetration and assess microleakage.

Following successful sample preparation, resin protrusions (Filtek Z350,3 M Company, USA) were bonded to the dentin surfaces according to the standardized procedure illustrated in Fig. 1. The specific bonding protocols for each experimental group are detailed in Table 12. All bonding procedures were performed by the same trained researcher to ensure consistency and minimize operator-induced variability.

Each dentin-resin protrusion sample was fixed on one side of a custom-made jig. An orthodontic ligature wire was gently looped around the bonding interface without applying pre-load pressure, with both ends clamped using a needle holder and secured to the opposing side of the jig. The micro-shear bond strength was measured using a universal testing machine (Yinuo Biotechnology Co., Ltd,, Jinan, China) at a crosshead speed of 1 mm/min (Fig. 1).

The maximum load at failure (F, in N) was recorded when the resin protrusion fractured. The bonding area (S) was standardized as a circular region with a diameter of 1 mm (S = 0.785 mm²). The micro-shear bond strength (P, in MPa) was calculated using the Eq. (5):

Each sample was tested once, and the mean ± standard deviation was calculated across groups.

After measuring the micro shear force using a universal material testing machine, the broken ends of the resin protrusion in all samples were placed under a Stereomicroscope (Olympus, Japan), the fracture patterns were observed, and the data were recorded for analysis.

Statistical methods

The data obtained in this study were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics 26, and GraphPad Prism 9.5 was used for graphing. Experimental data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) when normally distributed. For comparing multiple groups, one-way analysis of variance (One-Way ANOVA) was used when data followed a normal distribution. If variances were homogeneous, the Bonferroni method was used for post hoc comparison; if variances were heterogeneous, Tamhane’s T2 method was used. For skewed data, non-parametric tests were applied. A P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- AMX:

-

Amoxicillin

- CMC:

-

Carboxymethyl Cellulose

- CMC/AMX/nHA:

-

Carboxymethyl Cellulose/ Amoxicillin/ Nano-hydroxyapatite

- CMC/nHA:

-

Carboxymethyl Cellulose/ Nano-hydroxyapatite

- HAP:

-

Hydroxyapatite

- HPLC:

-

High Performance Liquid Chromatography Instrument

- nHA:

-

Nano-hydroxyapatite

- P. gingivalis:

-

Porphyromonas gingivalis

- SEM:

-

Scanning electron microscope

References

Hypersensitivity, C. A. B. D. Consensus-based recommendations for the diagnosis and management of dentin hypersensitivity[J]. J. Can. Dent. Assoc. 69 (4), 221–226 (2003).

Favaro Zeola, L., Soares, P. V. & Cunha-Cruz, J. Prevalence of dentin hypersensitivity: systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. J. Dent. 81, 1–6 (2019).

Mantzourani, M. & Sharma, D. Dentine sensitivity: past, present and future[J]. J. Dent. 41 (Suppl 4), S3–17 (2013).

Wenxiang, R. et al. A National survey on dentin hypersensitivity in Chinese urban adults[J]. Chin. J. Stomatology. 45 (3), 141–145 (2010).

Aminoshariae, A. & Kulild, J. C. Current concepts of dentinal Hypersensitivity[J]. J. Endod. 47 (11), 1696–1702 (2021).

Zeola, L. F., Soares, P. V. & Cunha-Cruz, J. Prevalence of dentin hypersensitivity: systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. J. Dent. 81, 1–6 (2019).

Carvalho, C. N. et al. Effect of ZOE temporary restoration on resin-dentin bond strength using different adhesive strategies[J]. J. Esthet Restor. Dent. 19 (3), 144–153 (2007).

Szcześ, A., Hołysz, L. & Chibowski, E. Synthesis of hydroxyapatite for biomedical applications[J]. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 249, 321–330 (2017).

Mo, X. et al. Nano-Hydroxyapatite composite scaffolds loaded with bioactive factors and drugs for bone tissue Engineering[J]. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24 (2), 1291 (2023).

Fox, K., Tran, P. A. & Tran, N. Recent advances in research applications of nanophase hydroxyapatite[J]. Chemphyschem 13 (10), 2495–2506 (2012).

Behzadi, S. et al. Occlusion effects of bioactive glass and hydroxyapatite on dentinal tubules: a systematic review[J]. Clin. Oral Investig. 26 (10), 6061–6078 (2022).

Daas, I., Badr, S. & Osman, E. Comparison between fluoride and Nano-Hydroxyapatite in remineralizing initial enamel lesion: an in vitro Study[J]. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 19 (3), 306–312 (2018).

Yuan, P. et al. Effect of a dentifrice containing different particle sizes of hydroxyapatite on dentin tubule occlusion and aqueous cr (VI) sorption[J]. Int. J. Nanomed. 14, 5243–5256 (2019).

Slots, J. Selection of antimicrobial agents in periodontal therapy[J]. J. Periodontal Res. 37 (5), 389–398 (2002).

Conrads, G. et al. The antimicrobial susceptibility of Porphyromonas gingivalis: genetic Repertoire, global Phenotype, and review of the Literature[J]. Antibiot. (Basel). 10 (12), 1438 (2021).

Rams, T. E., Sautter, J. D. & van Winkelhoff, A. J. Antibiotic resistance of human periodontal pathogen Parvimonas Micra over 10 Years[J]. Antibiot. (Basel). 9 (10), 709 (2020).

Evans J, Hanoodi M, Wittler M. Amoxicillin Clavulanate[M]. 2023 Aug 16, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing.

Ho, M. H. et al. The treatment response of barrier membrane with Amoxicillin-loaded nanofibers in experimental periodontitis[J]. J. Periodontol. 92 (6), 886–895 (2021).

Mallakpour, S., Tukhani, M. & Hussain, C. M. Recent advancements in 3D Bioprinting technology of carboxymethyl cellulose-based hydrogels: utilization in tissue engineering[J]. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 292, 102415 (2021).

Javanbakht, S. & Shaabani, A. Carboxymethyl cellulose-based oral delivery systems[J]. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 133, 21–29 (2019).

Fadeyi, I. et al. Quality of the antibiotics–Amoxicillin and co-trimoxazole from Ghana, Nigeria, and the united Kingdom[J]. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 92 (6 Suppl), 87–94 (2015).

Hsu, Y. H. et al. Biodegradable drug-eluting nanofiber-enveloped implants for sustained release of high bactericidal concentrations of Vancomycin and ceftazidime: in vitro and in vivo studies[J]. Int. J. Nanomed. 9, 4347–4355 (2014).

Perdigão, J. Current perspectives on dental adhesion: (1) dentin adhesion - not there yet[J]. Jpn Dent. Sci. Rev. 56 (1), 190–207 (2020).

Chou, P. Y. et al. Fabrication of Drug-Eluting Nano-Hydroxylapatite filled Polycaprolactone nanocomposites using Solution-Extrusion 3D printing Technique[J]. Polym. (Basel). 13 (3), 318 (2021).

Vimalraj, S. et al. A combinatorial effect of carboxymethyl cellulose based scaffold and microRNA-15b on osteoblast differentiation[J]. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 93 (Pt B), 1457–1464 (2016).

Baskar, K. et al. Eggshell derived Nano-Hydroxyapatite incorporated carboxymethyl Chitosan scaffold for dentine regeneration: A laboratory investigation[J]. Int. Endod J. 55 (1), 89–102 (2022).

Luo, J. P. et al. Electropolishing influence on biocompatibility of additively manufactured Ti-Nb-Ta-Zr: in vivo and in vitro[J]. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 34 (5), 25 (2023).

Kavasi, R. M. et al. Vitro biocompatibility assessment of Nano-Hydroxyapatite[J]. Nanomaterials (Basel). 11 (5), 1152 (2021).

Sun, H. et al. Antimicrobial behavior and mechanism of clove oil nanoemulsion[J]. J. Food Sci. Technol. 59 (5), 1939–1947 (2022).

Zhu, L. et al. Calibration of a lactic-acid model for simulating biofilm-induced degradation of the dentin-composite interface[J]. Dent. Mater. 33 (11), 1315–1323 (2017).

Wu, L. et al. Insight into the effects of Nisin and cecropin on the oral microbial community of rats by High-Throughput Sequencing[J]. Front. Microbiol. 11, 1082 (2020).

AlKanderi, S., AlFreeh, M., Bhardwaj, R. G. & Karched, M. Sugar substitute stevia inhibits biofilm formation, exopolysaccharide production, and downregulates the expression of streptococcal genes involved in exopolysaccharide synthesis. Dent. J. 11 (12), 267. https://doi.org/10.3390/dj11120267 (2023).

de Melo Alencar, C. et al. Clinical efficacy of Nano-Hydroxyapatite in dentin hypersensitivity: A systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. J. Dent. 82, 11–21 (2019).

Dionysopoulos, D., Gerasimidou, O. & Beltes, C. Dentin hpersensitivity: Etiology, diagnosis and contemporary therapeutic approaches—A review in literature. Appl. Sci. 13 (21), 11632. https://doi.org/10.3390/app132111632 (2023).

Yilmaz, N. A., Ertas, E. & Orucoğlu, H. Evaluation of five different desensitizers: A comparative dentin permeability and SEM investigation in Vitro[J]. Open. Dent. J. 11, 15–33 (2017).

Pushpalatha, C. et al. Nanohydroxyapatite in dentistry: A comprehensive review[J]. Saudi Dent. J. 35 (6), 741–752 (2023).

Giriyappa, R. H. & Chandra, B. S. Comparative evaluation of self-etching primers with fourth and fifth generation dentin-bonding systems on carious and normal dentin substrates: an in vitro shear bond strength analysis[J]. J. Conserv. Dent. 11 (4), 154–158 (2008).

Sano, H. et al. Tensile properties of mineralized and demineralized human and bovine dentin[J]. J. Dent. Res. 73 (6), 1205–1211 (1994).

Kim, J. H. et al. Comparison of shear test methods for evaluating the bond strength of resin cement to zirconia ceramic[J]. Acta Odontol. Scand. 72 (8), 745–752 (2014).

Nawrocka, A. et al. Traditional microscopic techniques employed in dental adhesion Research-Applications and protocols of specimen Preparation[J]. Biosens. (Basel). 11 (11), 408 (2021).

Okuyama, K. et al. Fluoride retention in root dentin following surface coating material Application[J]. J. Funct. Biomater. 14 (3), 171 (2023).

Dai, L. L. et al. Mechanisms of bioactive glass on caries management: A Review[J]. Mater. (Basel). 12 (24), 4183 (2019).

Ortiz-Ruiz, A. J. et al. Influence of fluoride varnish on shear bond strength of a universal adhesive on intact and demineralized enamel[J]. Odontology 106 (4), 460–468 (2018).

Han, X. Y., Zhu, H. S. & Liu, Q. Y. [Effect of different treatments of dentin surface on sheer bond strength between different bonding agents and dentin][J]. Hua Xi Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 26 (2), 125–128 (2008).

Turkistani, A. et al. Evaluation of microleakage in class-II bulk-fill composite restorations[J]. J. Dent. Sci. 15 (4), 486–492 (2020).

Anil, A. et al. Nano-Hydroxyapatite (nHAp) in the remineralization of early dental caries: A scoping Review[J]. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19 (9), 5629 (2022).

Pei, D. D. et al. [Effect of a nano hydroxyapatite desensitizing paste application on dentin bond strength of three self-etch adhesive systems][J]. Zhonghua Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 52 (5), 278–282 (2017).

Dawasaz, A. A. et al. Remineralization of dentinal lesions using biomimetic agents: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis[J]. Biomimetics (Basel). 8 (2), 159 (2023).

Grocholewicz, K. et al. Effect of nano-hydroxyapatite and Ozone on approximal initial caries: a randomized clinical trial. Sci. Rep. 10 (1), 11192. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-67885-8 (2020).

Luo, W. et al. The effect of disaggregated nano-hydroxyapatite on oral biofilm in vitro. Dent. Materials: Official Publication Acad. Dent. Mater. 36 (7), e207–e216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dental.2020.04.005 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Sichuan Science and Technology Program (2022YFS0634) + (2022YFS0634-B4); Luzhou Science and Technology Bureau (2022-GYF-11 and 2022-RCM-170); Chunhui Project of The Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China (HZKY20220577); Study on the quality of dentin bonding by naringenin pretreatment (2022QN093); Effect of Nd: YAG laser combined with bioactive glass pretreatment on dentin bond strength under simulated pulpal pressure (2022Y03).

Funding

This research was funded by Sichuan Science and Technology Program (2022YFS0634) + (2022YFS0634-B4); Luzhou Science and Technology Bureau (2022-GYF-11 and 2022-RCM-170); Chunhui Project of The Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China (HZKY20220577); Study on the quality of dentin bonding by naringenin pretreatment (2022QN093); Effect of Nd: YAG laser combined with bioactive glass pretreatment on dentin bond strength under simulated pulpal pressure (2022Y03).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XL.X. and AD.L. contributed to conceptualization. AD.L. and ZH.Z. performed data curation. XL.X., AD.L., and HM.C. conducted formal analysis. L.G. acquired funding and administered the project. AD.L. and HM.C. carried out the investigation. XL.X. and AD.L. developed the methodology. L.G. and XL.X. provided resources. L.G. supervised the project. ZK.W. performed validation. L.G. contributed to visualization. XL.X. prepared the original draft, while L.G. and ZH.Z. reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Institutional review board statement

The present study was approved by the Human Ethics Committee of the School of Stomatology and Stomatological Hospital of Southwest Medical University (Approval Number 20220806220). and performed by the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiong, X., Li, A., Zhang, Z. et al. In vitro study on the bacteriostatic effect of Amoxicillin-loaded Nano-hydroxyapatite and its capability in occluding dentinal tubules. Sci Rep 15, 41211 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25128-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25128-8