Abstract

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is characterized by chronic inflammation of the respiratory tract and is associated with an increased risk of lung cancer. Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients with COPD have been shown to exhibit favorable responses to anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy. In the present study, we investigated T cell profiles and functions in the lung tissues of NSCLC patients with or without COPD to provide the rationale for immunotherapy of NSCLC patients with COPD. Abundant PD-1+ and Tim-3+ T cells were detected in the lung tumor tissues of NSCLC patients with COPD. On the other hand, CD103+ tissue-resident memory T (TRM) cells in non-tumor lung tissues were more abundant in NSCLC patients with than in those without COPD. Furthermore, the abundance of CD103+ TRM cells in non-tumor lung tissues correlated with IFN-γ production and COPD-related clinical parameters (pack-years smoking history and the FEV1/FVC ratio). In NSCLC patients with COPD, T cells were active participants in both the non-tumor and the lung tumor tissues, suggesting the potential response to immunotherapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is associated with an increased risk of lung cancer1,2,3,4,5,6. Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients with COPD have been shown to exhibit favorable responses to anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy7,8,9. However, T cell profiles in the lung tissues of NSCLC patients with COPD have not yet been characterized in detail. Previous studies reported the presence of IFN-γ-producing and exhausted T cells in the lung tumor tissues of NSCLC patients with COPD7,8. However, the specific characteristics of T cell subsets in the non-tumor lung tissues of these patients remain unclear.

The main risk factor for COPD is cigarette smoking10,11. COPD is characterized by chronic inflammation of the respiratory tract induced by the exposure of susceptible individuals to tobacco smoke12. Previous studies indicated the involvement of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the pathogenesis of COPD13. CD8+ T cells were detected in histological analyses of airways from patients with COPD14. CD8+ T cells mainly localize within lymphoid follicles that accumulate around the airways with the progression of COPD13. A recent single-cell transcriptomic analysis revealed the polyclonal expansion of CD8+ T cells with terminal differentiation and resident memory (TRM) phenotypes in the lung tissues of patients with mild-to-moderate COPD15.

In contrast to CD8+ T cells, the characteristics of CD4+ T cells in the lung tissues of COPD patients remain unclear. T cell cultures and a T cell receptor (TCR) repertoire analysis revealed the oligoclonal expansion of CD4+ T cells from the lung tissues of COPD patients, indicating that CD4+ T cells resided in the lung tissues of COPD secondary to antigenic stimulation16. These findings suggest the involvement of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the pathogenic changes observed in the lung tissues of patients with COPD.

To clarify T cell immunity in the lung tissues of COPD with NSCLC in the context of cancer immunotherapy, we herein investigated the characteristics of the non-tumor and lung tumor tissues of NSCLC patients with or without COPD.

Results

Patient characteristics

Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. 107 patients were enrolled in the study. Patients in the COPD group were older than those in the non-COPD group (p = 0.0081). There were more males in the COPD group than in the non-COPD group (84.6 and 45.6%, respectively). The percentage of current or ex-smokers was higher in the COPD group than in the non-COPD group (87.2 and 58.8%, respectively). No significant difference was observed in the histology, stage, and interstitial lung disease (ILD) of lung cancer between the COPD and non-COPD groups. The diagnosis of ILD was based on the current consensus guidelines17. The FEV1/FVC ratio and FEV1% predicted values correlated with pack-years smoking history (p < 0.0001 and p = 0.0001, respectively) (Supplementary Fig. 1 A). Regarding the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) stages, the Kaplan-Meier analysis showed that OS was slightly shorter in patients with GOLD 2 COPD than in the other patients (p = 0.2874) (Supplementary Fig. 1B). No significant difference was observed in adjuvant therapies between the COPD and non-COPD groups (Table 1). These results were consistent with previous findings on NSCLC patients with COPD.

Characteristics of T cells in lung tumor tissues of patients with COPD

Flow cytometry was performed to investigate T cell profiles in the tumor and non-tumor lung tissues of NSCLC patients with or without COPD. The ratio of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells did not significantly differ between the COPD and non-COPD groups, except for the percentage of CD4+ T cells in lung tumor tissues, which was lower in the COPD group than in the non-COPD group (p = 0.0144) (Supplementary Fig. 2). Regarding immune checkpoint molecules, the percentages of PD-1+ CD4+ T cells in lung tumor tissues were slightly higher in the COPD group than in the non-COPD group (p = 0.1144) (Fig. 1A). The percentages of Tim-3+ CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in lung tumor tissues were higher in the COPD group than in the non-COPD group (p = 0.0032 and 0.0032, respectively) (Fig. 1B), indicating antigen-specific T cell activity in lung tumor tissues of patients associated with COPD. A subgroup analysis specifically for adenocarcinomas also showed a similar trend (Supplementary Fig. 3). In GOLD stages of COPD, the percentages of PD-1+CD8+ T cells in lung tumor tissues were higher in the GOLD 1 group than in the GOLD 2 group (p = 0.0351) (Supplementary Fig. 4 A and 4B). The proportion of PD-1+ and Tim-3+ T cells in lung tumor tissues exhibited a significant elevation in the groups of the male, smoker, and inhaled bronchodilator administration (Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6). In the analysis of immunosuppression by Treg cells, the ratio of Treg cells (CD45RA−Foxp3hi, Foxp3+CCR8+, and CD45RA−CD25hi CD4+ T cells) in lung tissues did not significantly differ between the COPD and non-COPD groups (Fig. 2). A subgroup analysis specifically for adenocarcinomas also showed a similar trend (Supplementary Fig. 7).

T cell profiles in lung tissues of NSCLC patients with or without COPD. (A) The ratios of PD-1+ T cells in the CD4+ or CD8+ T cells of NIC or TIC were compared between NSCLC patients with or without COPD. (B) The ratios of Tim-3+ cells in the CD4+ and CD8+ T cells of NIC or TIC were compared between NSCLC patients with or without COPD. Data represent the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). The Mann–Whitney U test was used to analyze the significance of differences between samples. The p-value < 0.05 was considered to be significant. NIC, non-tumor infiltrating cells; TIC, tumor-infiltrating cells.

Regulatory T cells in lung tissues of NSCLC patients with or without COPD. (A) The ratios of CD45RA−Foxp3hi cells in the CD4+ T cells of NIC or TIC were compared between NSCLC patients with or without COPD. (B) The ratios of Foxp3+CCR8+ cells in the CD4+ T cells of NIC or TIC were compared between NSCLC patients with or without COPD. (C) The ratios of CD45RA−CD25hi cells in the CD4+ T cells of NIC or TIC were compared between NSCLC patients with or without COPD. Data represent the mean ± SEM. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to analyze the significance of differences between samples. The p-value < 0.05 was considered to be significant. NIC, non-tumor infiltrating cells; TIC, tumor-infiltrating cells.

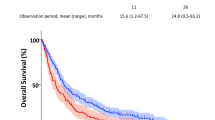

We examined T cell cytotoxicity in lung tumor tissues using the BiTE assay system (Fig. 3A). In this assay system, T cell cytotoxicity was analyzed in a co-culture of lung tumor-infiltrating cells and a tumor cell line with BiTE, which was specific for CD3 on T cells and a tumor antigen in the tumor cell line. The analysis employing the BiTE assay system demonstrated that T cell cytotoxicity in lung tumor tissues was enhanced in the GOLD 1 COPD group. However, no significant difference in T cell cytotoxicity was observed between the GOLD 2 COPD and non-COPD groups, indicating a reduction in T cell cytotoxicity in patients with more advanced stages of COPD (Fig. 3B). T cell cytotoxicity exhibited a significant elevation in the groups of the smoker and inhaled bronchodilator administration, which is related to COPD features (Supplementary Fig. 8). To combine functional analyses of T cell cytotoxicity with cytokine secretion, IFN-γ production by CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, was examined post-stimulation of bulk T cells in lung tumor tissues with PMA/ionomycin. Intratumoral T cell cytotoxicity was correlated with IFN-γ production by CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in lung tumor tissues (p = 0.0173 and 0.0083, respectively) (Fig. 3C). For NSCLC patients received anti-PD-1 therapy after recurrence, PFS was slightly longer in patients with COPD than in those without COPD (Fig. 3D). These findings suggest that T cell activity in lung tumor tissues associated with COPD was augmented by anti-PD-1 therapy.

Intratumoral T cell cytotoxicity of NSCLC patients with or without COPD. (A) The BiTE assay system that measures T cell cytotoxicity against tumor cells using the Bispecific T cell Engager (BiTE). Lung tumor-infiltrating cells were co-cultured with U251 cells and BiTE. The cytotoxicity of T cells against U251 cells was measured using the MTS assay. (B) T cell cytotoxicity in lung tumor tissues was compared among NSCLC patients with COPD (GOLD 1 and GOLD 2) and those without COPD. T cell cytotoxicity against U251 tumor cells was assessed using BiTE. Tumor-infiltrating cells (TIC) (5 × 10⁴ cells per well in 96-well flat-bottomed cell culture plates) were co-cultured with U251 cells (1 × 10⁴ cells per well in 96-well flat-bottomed plates) in the presence of BiTE (100 ng/mL) for 48 h. The cytolytic activity of T cells against U251 cells was evaluated using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)−5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)−2-(4-sulfophenyl)−2 H-tetrazolium (MTS) assay. Data represent the mean ± SEM. A one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc test was employed for comparisons to compare differences with respective values in the non-COPD group as the control. The p-value < 0.05 was considered to be significant. (C) The ratios of IFN-γ-producing cells in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells of TIC were analyzed for correlations with the T cell cytotoxicity in lung tumor tissues (n = 16). Intracellular IFN-γ staining of TIC was performed following stimulation with 50 ng/mL PMA (Sigma-Aldrich) and 1 µM ionomycin (Sigma-Aldrich) for 4 h. Relationships between paired data were examined utilizing simple linear regression analysis after log normalization. (D) Kaplan–Meier curves for the progression-free survival (PFS) of NSCLC patients with or without COPD after the initiation of anti-PD-1 therapy. PFS was evaluated using the Kaplan-Meier method, with distinctions among cohorts calculated through the Log-rank test. TIC, tumor-infiltrating cells.

CD103+ tissue-resident memory T cells in non-tumor lung tissues of patients with COPD

To elucidate the characteristics of the T cell profile in the non-tumor lung tissues of patients with COPD, the T cell markers of each T cell subset were analyzed using a flow cytometric analysis of the lung tissues of NSCLC patients with or without COPD. Data from flow cytometry were subsequently examined using Cytobank software. The FlowSOM clustering analysis was conducted using the data from flow cytometric analysis after gating CD3+ T cells. Six clusters were identified by the FlowSOM analysis, while T cells in cluster 3 increased in the COPD group (Supplementary Fig. 9 A). The viSNE analysis, a dimensionality reduction analysis using the data from flow cytometric analysis, showed that the T cell subset in cluster 3 was CD103+ T cells in the COPD group (Supplementary Fig. 9B). The CITRUS analysis, a method for the fully automated discovery of significant stratifying biological signatures using data from a flow cytometric analysis, also identified a population of several CD4+ T cell clusters that highly expressed CD103, a marker of tissue-resident memory T (TRM) cells, in the COPD group (Supplementary Fig. 9 C).

The outcomes of the flow cytometric analysis consistently demonstrated that the proportion of CD103+ CD4+ TRM cells in non-tumor lung tissues exhibited a significant elevation in the COPD group compared to the non-COPD group (p = 0.0145) (Fig. 4A and Supplementary Fig. 10). In GOLD stages of COPD, there was no significant difference in the percentages of CD103+ TRM cells between the GOLD 1 and GOLD 2 groups (Supplementary Fig. 11). The proportion of CD103+ TRM cells in non-tumor lung tissues exhibited a significant elevation in the groups of the smoker and inhaled bronchodilator administration, which is related to COPD features (Supplementary Fig. 12). Drawing insights from the T cell profiles of lung tissues derived from NSCLC patients with or without COPD, we proceeded to perform a functional assessment of T cells within these tissues. The cytokine production, encompassing IFN-γ, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and IL-2, by CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, was scrutinized post-stimulation of bulk T cells in non-tumor lung tissues with PMA/ionomycin. Although there was no significant difference in cytokine secretion of T cells in non-tumor lung tissues between the COPD and non-COPD groups (Supplementary Fig. 13), particularly noteworthy was the observed positive correlation between IFN-γ production by CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and the proportion of CD103+ cells within the CD4+ and CD8+ T cell subsets, respectively, in non-tumor lung tissues (p = 0.0066 and 0.0124, respectively) (Fig. 4B and Supplementary Fig. 14). These findings underscore a favorable association between abundant CD103+ TRM cells and IFN-γ production in the non-tumor lung tissues of NSCLC patients with COPD.

Characteristics of CD103+ TRM cells in non-tumor lung tissues of NSCLC patients with or without COPD. (A) The ratios of CD103+ cells in the CD4+ and CD8+ T cells of NIC were compared between NSCLC patients with or without COPD. Data represent the mean ± SEM. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to analyze the significance of differences between samples. The p-value < 0.05 was considered to be significant. (B) The ratios of IFN-γ-producing cells in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were analyzed for correlations with the ratios of CD103+ cells in the CD4+ and CD8+ T cells of NIC (n = 47). Intracellular IFN-γ staining of NIC was performed following stimulation with 50 ng/mL PMA (Sigma-Aldrich) and 1 µM ionomycin (Sigma-Aldrich) for 4 h. Relationships between paired data were examined utilizing simple linear regression analysis after log normalization. NIC, non-tumor infiltrating cells.

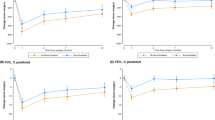

Correlations between CD103+CD4+ TRM cells and COPD-related clinical parameters

We examined the relationships between CD103+ TRM cells and smoking status and airway obstruction, which are clinical parameters related to the pathogenesis of COPD. Regarding the smoking status, the percentage of CD103+ CD4+ and CD8+ TRM cells in non-tumor lung tissues showed positive correlation with pack-years of smoking in NSCLC patients (p = 0.0141 and 0.0008, respectively) (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, the FEV1/FVC ratio showed slightly negative correlation with the percentage of CD103+CD4+ and CD8+ TRM cells in the non-tumor lung tissues of NSCLC patients (p = 0.0187 and 0.1147, respectively) (Fig. 5B). To investigate the relationship between clinical outcome and CD103+ TRM cells, we analyzed overall survival of NSCLC patients. By the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis, the cut-off values for the ratios of CD103+ in CD4+ (18.8%) and CD8+ (38.2%) T cells were calculated to differentiate NSCLC patients with COPD from those without COPD (Supplementary Fig. 15). Overall survival was slightly shorter in patients with a high CD103+/CD8+ T cell ratio (≥ 38.2%) than in those with a low CD103+/CD8+ T cell ratio (< 38.2%) (Fig. 5C and D). These results are consistent with a possible involvement of CD103+ TRM cells in the regulation of changes induced by smoking and airway obstruction in non-tumor lung tissues, which are related to the pathogenesis of COPD.

Correlations of CD103+CD4+ TRM cells with COPD-related clinical parameters. (A) Correlations of pack-years smoking history with the ratios of CD103+ cells in the CD4+ and CD8+ T cells of NIC (n = 96). Relationships between paired data were examined utilizing simple linear regression analysis after log normalization. (B) Correlations of FEV1/FVC ratio with the ratios of CD103+ cells in the CD4+ and CD8+ T cells of NIC (n = 100). Relationships between paired data were examined utilizing simple linear regression analysis after log normalization. (C) Kaplan-Meier curves for overall survival (OS) were compared between NSCLC patients with CD103+ high (≥ 18.8%) and CD103+ low (< 18.8%) ratios in CD4+ T cells of NIC. OS was evaluated using the Kaplan-Meier method, with distinctions among cohorts calculated through the Log-rank test. (D) Kaplan-Meier curves for overall survival (OS) were compared between NSCLC patients with CD103+ high (≥ 38.2%) and CD103+ low (< 38.2%) ratios in CD8+ T cells of NIC. OS was evaluated using the Kaplan-Meier method, with distinctions among cohorts calculated through the Log-rank test. NIC, non-tumor infiltrating cells.

Discussion

In the present study, we investigated T cell immunity in the lung tumor tissues of NSCLC patients with and without COPD. The percentage of PD-1+ and Tim-3+ T cells in lung tumor tissues was higher in NSCLC patients with than in those without COPD, suggesting the result of antigen-specific T cell responses in lung tumor tissues with COPD. Previous studies demonstrated that the co-expression of PD-1 and Tim-3 in tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) of patients with NSCLC and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is associated with T-cell activation, despite the elevated levels of proapoptotic markers in these cells18,19. This is consistent with a model in which coinhibitory receptors are upregulated following T-cell stimulation to mitigate excessive immune responses. Our findings indicated that T cell cytotoxicity was diminished in the GOLD 2 COPD group compared to the GOLD 1 group, suggesting a reduction in T cell cytotoxicity in patients with more advanced stages of COPD. These results are consistent with previous findings showing that NSCLC patients with COPD exhibited favorable responses to immunotherapy against cancer7,8,9. Although there are substantial baseline differences between the COPD and non-COPD groups in terms of age, sex, smoking history, and inhaled bronchodilator use, these confounders did not affect overall postoperative survival in the Cox proportional hazards model (data not shown).

We also showed that the percentage of CD103+ tissue-resident memory T (TRM) cells in non-tumor lung tissues was higher in NSCLC patients with than in those without COPD. The percentage of CD103+ TRM cells in non-tumor lung tissues positively correlated with IFN-γ production by T cells and pack-years of smoking and negatively correlated with the FEV1/FVC ratio of NSCLC patients. These results are consistent with a possible involvement of CD103+ TRM cells in pathological processes in the non-tumor lung tissues of NSCLC patients with COPD.

The previous reports indicated that CD103+ TRM cells were related to the pathogenesis of immune-related adverse events (irAEs) induced by immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs). It was reported that TRM cells dominated the inflammatory reactions associated with immune-related dermatitis and colitis induced by ICIs20,21. The results of previous studies were controversial regarding the risk of irAEs in NSCLC patients with COPD. A retrospective study of 315 NSCLC patients receiving ICIs showed that COPD was associated with an increased risk for immune-related pneumonitis22. On the other hand, another retrospective study of 61 patients who had COPD with NSCLC treated with ICIs showed that immune-related pneumonitis was similar in those with and without COPD23.

In our current study, one patient suffered from immune-related pneumonitis. The percentage of CD103+CD4+ TRM cells in non-tumor lung tissues of the patient was 27.2%, whereas the average percentage of CD103+CD4+ TRM cells was 18.7% in the NSCLC patients. The results of our present study of the abundance of CD103+ TRM cells in non-tumor lung tissues of COPD are consistent with a possible involvement of CD103+ TRM cells in the pathogenesis of irAEs for NSCLC patients with COPD. However, it was a hypothesis-generating observation, not a conclusion.

CD103 integrin is a heterodimeric transmembrane receptor. Its binding to E-cadherin, its ligand expressed on epithelial cells, has been shown to promote the accumulation and maintenance of TRM cells within tissues24. Previous studies indicated the critical role of CD103+CD8+ TRM cells in lung cancer25,26. CD103 is recruited at immune synapses between cytotoxic T lymphocytes and epithelial tumor cells, and its interaction with E-cadherin is required for the polarized exocytosis of lytic granules, leading to targeted tumor cell lysis27. In human lung tumors, CD103+CD8+ TRM cells were found to express mRNA-encoding molecules associated with the cytotoxic activities of T cells, such as IFN-γ and granzyme B28. Moreover, a retrospective cohort analysis indicated that increases in CD103+CD8+ TRM cells in lung tumor tissues were associated with better outcomes in anti-PD-1-treated NSCLC patients29. A single-cell RNA sequencing analysis also identified intratumoral CD103+CD8+ TRM cells as a predictive biomarker for anti-PD-L1 therapy in NSCLC patients30. The present study indicated that CD103+ TRM cells were characteristic of the non-tumor lung tissues of NSCLC patients with COPD. Our findings suggest that CD103+ TRM cells are activated in non-tumor lung tissues, as evidenced by their correlation with IFN-γ production. Although the relationship between COPD and CD103+ TRM cells remains unclear31, a correlation between TRM cells and chronic inflammatory diseases has been reported32. Regarding inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), TRM cells were increased in the mucosa of IBD patients and highly expressed pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IFN-γ. Intestinal CD4+ TRM cells were associated with flares in IBD33. Another study indicated that CD103+CD4+ TRM cells played an important role in the pathogenesis of severe asthma34. A single-cell transcriptome analysis of CD4+ T cells isolated from bronchoalveolar lavage samples of patients with severe asthma showed significant increases in CD103+CD4+ TRM cells, which were enriched for transcripts linked to TCR activation and cytotoxicity, and expressed high levels of transcripts encoding for pro-inflammatory non-Th2 cytokines when stimulated34. Based on these studies, the correlation of CD103+ TRM cells with COPD-related clinical parameters in the present study suggested the progression of the pro-inflammatory process in the pathogenesis of COPD. In the present study, non-tumor lung tissues with COPD included abundant CD103+ TRM cells, which positively correlated with IFN-γ production by T cells and pack-years of smoking and negatively correlated with the FEV1/FVC ratio, indicating a relationship between CD103+ TRM cells and the pathogenesis of COPD. The present study showed that NSCLC patients with higher CD103+CD8+ TRM in non-tumor lung tissues had slightly shorter OS, implicating the pathogenic role of CD103+ TRM cells for patients with COPD. On the other hand, previous reports have shown that CD103+CD8+ TRM cells often predict better ICI response in patients with NSCLC, indicating distinct characteristics of CD103⁺CD8⁺ TRM cells in lung tumor tissues compared to non-tumor lung tissues.

Several limitations need to be addressed. Significant differences existed between the COPD and non-COPD groups in baseline demographic characteristics, including age, sex, smoking history, and pharmacological interventions, which conceivably impacted T cell immunity within the lung tissues of these individuals. Aging precipitates a diminution in T cell responsiveness, for example35. The antigens recognized by TRM cells were not identified in the present study. Therefore, identifying the target antigens of CD103+ TRM cells in non-tumor lung tissues with COPD will provide insights into its pathogenesis. We analyzed limited cytokines in the current study. Additional research regarding the characteristics and functions of T cells through specific molecular pathways and cytokine networks is needed to reveal potential therapeutic targets of NSCLC patients with COPD. TRM functionality was not validated by depletion or lineage tracing (e.g., in animal models). Furthermore, a prospective study of NSCLC patients with COPD receiving ICIs is needed to address the relationship between the pre-treatment immune profile of lung tissues and the treatment outcome of ICIs including treatment efficacy and immune-related adverse events.

In conclusion, T cells were active participants in both the non-tumor and the lung tumor tissues of NSCLC patients with COPD, suggesting the potential response to immunotherapy. Further studies are needed to clarify the role of T cell immunity in the pathogenesis of NSCLC patients with COPD.

Methods

Study populations

All studies on human subjects were performed with informed consent using protocols approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Osaka University Hospital (control number 13266). The study population included NSCLC patients eligible for the surgical resection of primary lung tumors at Osaka University Hospital between May 2015 and September 2020. Patients with metastatic lung cancer were excluded from the study population. The primary endpoint of the study is to identify the T cell subset characteristic of COPD with NSCLC patients. To achieve 80% power with an alpha error of 5%, the required sample size was 19 patients in the COPD group and 43 patients in the non-COPD group. Source data comprised patients with NSCLC recruited from Osaka University Hospital. NSCLC patients with COPD were defined based on the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) guidelines, including FEV1/FVC < 0.736. The surgical resection of NSCLC was performed at Osaka University Hospital, and specimens were collected from excess clinical samples. Additional surgical sampling beyond the required surgery was not conducted. Demographic, clinical, and spirometry data were obtained within one month before surgery. Patients were followed up for 60 months for a time-to-event analysis, in which death was considered to be the event. For patients subjected to anti-PD-1 therapy after recurrence, progression-free survival (PFS) was assessed from the inception of anti-PD-1 therapy until disease progression as per RECIST version 1.1 criteria. PFS without disease progression was censored at the date of last known contact.

Sample preparation

Non-tumor lung tissue samples were collected as far away as possible from the lung tumor site. Samples were dissociated into single cells and subjected to a flow cytometry analysis within 24 h of surgery. Tumor and non-tumor lung tissues were finely minced within a 6-cm dish, subsequently undergoing digestion to yield a single-cell suspension, utilizing a Tumor Dissociation Kit for humans (Miltenyi Biotec) and gentle MACS Dissociator (Miltenyi Biotec) based on the manufacturer’s instructions. The cell suspension was put on a 70-µm nylon cell strainer (Corning) with BD Pharm Lyse (Becton Dickinson) to lyse red blood cells. Dead cells and debris were removed by centrifugation in isodensity Percoll solution (GE Healthcare) and the resulting suspension was subjected to flow cytometric analyses. The remaining cells were aliquoted and stored at −80℃ in a liquid nitrogen tank for later use in the in vitro T cell stimulation for intracellular cytokine staining.

Flow cytometric analysis

A flow cytometric analysis was performed on BD LSRFortessa X-20 (Becton Dickinson) with FACSDiva software (Becton Dickinson). Following Fc receptor blockade with the Human TruStain FcX Fc Receptor blocking solution (BioLegend), surface and intracellular marker staining procedures were carried out. Subsequently, cells were incubated with the Zombie NIR Fixable Viability Kit (BioLegend).

The antibodies used for surface marker staining are shown in Supplementary Table 1 (Supplementary Fig. 16 A).

In the intracellular staining of Foxp3, the antibodies used for cell surface staining are shown in Supplementary Table 1. After cell surface staining, cell fixation and perforation were performed with the Foxp3/Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Intracellular Foxp3 staining was conducted using APC anti-human Foxp3 (clone PCH101) (Invitrogen) (Supplementary Fig. 16B).

In the intracellular cytokine staining analysis, the antibodies used for cell surface staining are shown in Supplementary Table 1. Cell fixation and perforation were then performed with the Transcription Factor Buffer Set (Becton Dickinson) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Intracellular cytokine staining was conducted using the antibodies shown in Supplemental Table 1 (Supplementary Fig. 16 C).

In vitro stimulation for intracellular cytokine staining

Frozen cells were rapidly thawed in a 37℃ water bath and immediately used for the phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA)/ionomycin stimulation. Between 5.0 × 105 and 1.0 × 106 thawed cells were suspended in 1 mL of AIM V™ Medium (Thermo Fisher) and then added to 24-well plates. Samples were stimulated with 50 ng/ml PMA (Sigma-Aldrich), 1 µM ionomycin (Sigma-Aldrich), and a 1:1500 dilution of Protein Transport Inhibitor (BD GolgiPlug) at 37℃, 5% CO2, for 4 h. A 1:1500 dilution of Protein Transport Inhibitor was added to wells containing negative control samples (without any stimulation). Harvested cells were washed and stained with antibodies as described in the “Flow cytometric analysis” section.

T cell cytotoxicity assay

The EphA2/CD3 Bispecific T cell Engager (BiTE) was synthesized according to the methodologies outlined in our prior investigations37,38,39,40. The U251 cell line was kindly provided by Dr. Yasuko Mori from Kobe University, Japan. Authentication of the cell line was conducted via short tandem repeat profiling and mycoplasma testing at the JCRB Cell Bank in Osaka, Japan. U251 cells were plated onto 96-well flat-bottom cell culture plates (Corning) at a density of 1 × 104 cells per well in RPMI medium 1640 (Nacalai Tesque) supplemented with 10% FBS. Following a 24-hour incubation at 37 °C with 5% CO2, freshly isolated cells derived from lung tissues (5 × 104 cells) were seeded onto the plates along with 100 ng/mL of EphA2/CD3 BiTE. After a 48-hour co-culture at 37 °C with 5% CO2, non-adherent cells were meticulously removed by washing four times with RPMI medium 1640 containing 10% FBS. The remaining adherent viable tumor cells were assessed using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)−5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)−2-(4-sulfophenyl)−2 H-tetrazolium (MTS) assay (CellTiter 96 aqueous one solution cell proliferation assay, Promega), performed in triplicate. The quantification of EphA2/CD3 BiTE-mediated cytotoxicity was determined based on the reduction in viable target cells using the following formula:

Each non-treated well consisted of 1 × 104 U251 cells and 5 × 104 freshly isolated cells from lung tissues without EphA2/CD3 BiTE.

Statistical analysis

The Mann–Whitney U test was used to analyze the significance of differences between samples. A one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc test was employed for multiple comparisons to compare differences with respective values in the non-COPD group as the control. Relationships between paired data were examined utilizing simple linear regression analysis after log normalization. Regarding survival analysis, the starting point was the date of surgery. PFS and overall survival (OS) were evaluated using the Kaplan-Meier method, with distinctions among cohorts calculated through the Log-rank test. The p-value < 0.05 was considered to be significant. Statistical analyses were conducted using JMP software (SAS Institute, Inc.).

Ethics approval.

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Osaka University Hospital (IRB number 13266).

Consent to participate.

Written informed consent was obtained from participants prior to their inclusion in the study. The present study was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

Young, R. P. et al. COPD prevalence is increased in lung cancer, independent of age, sex and smoking history. Eur. Respir J. 34 (2), 380–386 (2009).

Park, H. Y. et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and lung cancer incidence in never smokers: a cohort study. Thorax 75 (6), 506–509 (2020).

Wasswa-Kintu, S., Gan, W. Q., Man, S. F., Pare, P. D. & Sin, D. D. Relationship between reduced forced expiratory volume in one second and the risk of lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax 60 (7), 570–575 (2005).

Hohberger, L. A. et al. Correlation of regional emphysema and lung cancer: a lung tissue research consortium-based study. J. Thorac. Oncol. 9 (5), 639–645 (2014).

Young, R. P. et al. Airflow limitation and histology shift in the National lung screening Trial. The NLST-ACRIN cohort substudy. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 192 (9), 1060–1067 (2015).

Hopkins, R. J. et al. Reduced expiratory flow rate among heavy smokers increases lung cancer Risk. Results from the National lung screening Trial-American college of radiology imaging network cohort. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 14 (3), 392–402 (2017).

Mark, N. M. et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease alters immune cell composition and immune checkpoint inhibitor efficacy in Non-Small cell lung cancer. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 197 (3), 325–336 (2018).

Biton, J. et al. Impaired Tumor-Infiltrating T cells in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease impact lung cancer response to PD-1 Blockade. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 198 (7), 928–940 (2018).

Shin, S. H. et al. Improved treatment outcome of pembrolizumab in patients with nonsmall cell lung cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int. J. Cancer. 145 (9), 2433–2439 (2019).

Vestbo, J. et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 187 (4), 347–365 (2013).

Barnes, P. J. et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 1, 15076 (2015).

Barnes, P. J. Immunology of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8 (3), 183–192 (2008).

Hogg, J. C. et al. The nature of small-airway obstruction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl. J. Med. 350 (26), 2645–2653 (2004).

Saetta, M. et al. CD8 + T-lymphocytes in peripheral airways of smokers with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 157 (3 Pt 1), 822–826 (1998).

Villaseñor-Altamirano, A. B. et al. Activation of CD8 + T cells in COPD lung. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. (2023).

Sullivan, A. K. et al. Oligoclonal CD4 + T cells in the lungs of patients with severe emphysema. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 172 (5), 590–596 (2005).

Raghu, G. et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (an Update) and progressive pulmonary fibrosis in adults: an official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 205 (9), e18–e47 (2022).

Datar, I. et al. Expression analysis and significance of PD-1, LAG-3, and TIM-3 in human Non-Small cell lung cancer using spatially resolved and multiparametric Single-Cell analysis. Clin. Cancer Res. 25 (15), 4663–4673 (2019).

Roussel, M. et al. Functional characterization of PD1 + TIM3 + tumor-infiltrating T cells in DLBCL and effects of PD1 or TIM3 Blockade. Blood Adv. 5 (7), 1816–1829 (2021).

Reschke, R. et al. Checkpoint Blockade-Induced dermatitis and colitis are dominated by Tissue-Resident memory T cells and Th1/Tc1 cytokines. Cancer Immunol. Res. 10 (10), 1167–1174 (2022).

Reschke, R. & Gajewski, T. F. Tissue-resident memory T cells in immune-related adverse events: friend or foe? Oncoimmunology 12 (1), 2197358 (2023).

Atchley, W. T. et al. Immune checkpoint Inhibitor-Related pneumonitis in lung cancer: Real-World Incidence, risk Factors, and management practices across six health care centers in North Carolina. Chest 160 (2), 731–742 (2021).

Zeng, Z. et al. Clinical outcomes and risk factor of immune checkpoint inhibitors-related pneumonitis in non-small cell lung cancer patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. BMC Pulm Med. 22 (1), 458 (2022).

Cepek, K. L. et al. Adhesion between epithelial cells and T lymphocytes mediated by E-cadherin and the alpha E beta 7 integrin. Nature 372 (6502), 190–193 (1994).

Damei, I., Trickovic, T., Mami-Chouaib, F. & Corgnac, S. Tumor-resident memory T cells as a biomarker of the response to cancer immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 14, 1205984 (2023).

Mami-Chouaib, F. et al. Resident memory T cells, critical components in tumor immunology. J. Immunother Cancer. 6 (1), 87 (2018).

Le Floc’h, A. et al. Alpha E beta 7 integrin interaction with E-cadherin promotes antitumor CTL activity by triggering lytic granule polarization and exocytosis. J. Exp. Med. 204 (3), 559–570 (2007).

Ganesan, A. P. et al. Tissue-resident memory features are linked to the magnitude of cytotoxic T cell responses in human lung cancer. Nat. Immunol. 18 (8), 940–950 (2017).

Corgnac, S. et al. CD103. Cell. Rep. Med. 1 (7), 100127 (2020).

Banchereau, R. et al. Intratumoral CD103 + CD8 + T cells predict response to PD-L1 Blockade. J. Immunother Cancer 9(4) (2021).

Leckie, M. J. et al. Sputum T lymphocytes in asthma, COPD and healthy subjects have the phenotype of activated intraepithelial T cells (CD69 + CD103+). Thorax 58 (1), 23–29 (2003).

Hirahara, K., Kokubo, K., Aoki, A., Kiuchi, M. & Nakayama, T. The role of CD4. Front. Immunol. 12, 616309 (2021).

Zundler, S. et al. Hobit- and Blimp-1-driven CD4. Nat. Immunol. 20 (3), 288–300 (2019).

Herrera-De La Mata, S. et al. Cytotoxic CD4 Med. (2023).

Quinn, K. M., Vicencio, D. M. & La Gruta, N. L. The paradox of aging: Aging-related shifts in T cell function and metabolism. Semin Immunol. 70, 101834 (2023).

Global strategy for the. diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. [accessed 07 Jul 2022]. Available: https://goldcopd.org/ .

Iwahori, K. et al. Engager T cells: a new class of antigen-specific T cells that redirect bystander T cells. Mol. Ther. 23 (1), 171–178 (2015).

Iwahori, K. et al. Peripheral T cell cytotoxicity predicts T cell function in the tumor microenvironment. Sci. Rep. 9 (1), 2636 (2019).

Yamamoto, Y. et al. Immunotherapeutic potential of CD4 and CD8 single-positive T cells in thymic epithelial tumors. Sci. Rep. 10 (1), 4064 (2020).

Iwahori, K. et al. Peripheral T cell cytotoxicity predicts the efficacy of anti-PD-1 therapy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients. Sci. Rep. 12 (1), 17461 (2022).

Acknowledgements

Illustrations were created using https://BioRender.com.

Funding

This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI (21K08153 and 24K11315 to KI) and a research grant from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) (24ama221340h9901 to KI).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MT: Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization. TI: Investigation, Data Curation, Formal analysis, Writing - Review & Editing. YY: Investigation, Data Curation, Formal analysis, Writing - Review & Editing. YT: Supervision, Writing - Review & Editing. YS: Supervision, Writing - Review & Editing. AK: Supervision, Writing - Review & Editing. HW: Supervision, Writing - Review & Editing. KI: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tone, M., Isono, T., Yamamoto, Y. et al. Lung tissue T cells are activated in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with non-small cell lung cancer patients. Sci Rep 15, 41209 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25141-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25141-x