Abstract

Internet of Things (IoT) networks face increasing cyber threats that require collaborative intrusion detection across distributed environments. Existing federated learning approaches for intrusion detection have critical architectural and methodological limitations: traditional federated approaches using deep learning methods like LSTM and CNN cannot capture structural patterns as these architectures are not designed to model network graph topology, while GNN-based federated approaches can preserve structural patterns but lose temporal patterns during parameter aggregation, making both ineffective against sophisticated coordinated attacks like DDoS campaigns. Yet, detecting coordinated attacks requires understanding both structural relationships and temporal sequences across networks. This paper proposes FedGATSage, a federated learning architecture that integrates client-side Graph Attention Networks with server-side GraphSAGE through community abstraction to address both architectural and temporal limitations. The approach uses specialized detector variants for different attack types and preserves both structural and temporal attack patterns while protecting device identities through community-based embeddings. The latter aims to aggregate the information of groups of nodes at the client level before the submission to the server which reduces communication overhead by 85%. Extensive experiments on NF-ToN-IoT and CIC-ToN-IoT datasets demonstrate that FedGATSage achieves performance comparable to centralized approaches while preserving privacy, significantly outperforming existing federated solutions and successfully detecting challenging coordinated attacks that current federated methods cannot handle.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Intrusion Detection Systems (IDSs) are a key defense mechanism to protect organizational resources against cyber threats. Traditional IDSs relied on signature-based methods that identified familiar attack signatures, but were unable to address zero-day attacks and evolving attack techniques1. This weakness is especially prevalent in distributed environments like modern IoT networks, where centralized data collection creates significant privacy concerns and regulatory constraints2,3. The fundamental challenge is that organizations cannot share raw network data due to privacy regulations and competitive concerns, yet sophisticated attacks like coordinated DDoS and advanced persistent threats require understanding both network relationships and attack sequences that span multiple networks.

The development of intrusion detection methods has followed a clear evolutionary path toward increasing sophistication in response to these challenges. Early systems used rule-based signatures and statistical anomaly detection with restricted ability to adapt to rapidly increasing threats4. Subsequently, machine learning approaches transformed the field, with methods like Support Vector Machines5 and Random Forests6 improving detection through pattern learning3. This progression paved the path for deep learning structures that could discover hierarchical features autonomously from raw network flows4. Most notably, Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) have shown superior performance for network intrusion detection by modeling the inherent graph structure of network communications7,8,9. GNNs achieve exceptional effectiveness through explicit modeling of network topology, delivering state-of-the-art results on benchmark datasets like NF-ToN-IoT and CIC-ToN-IoT10,11. Two GNN variants have demonstrated exceptional performance: Graph Attention Networks (GAT) excel at identifying malicious connection patterns by differentially weighting neighbor importance12, particularly valuable for detecting attacks like backdoors, while GraphSAGE’s neighborhood sampling approach performs well on large-scale networks and allows adaptation to new attack patterns through inductive capabilities13. These complementary strengths have improved detection accuracy for complex attacks that would often be missed by traditional methods14,15.

While these centralized approaches achieved significant advances, the emergence of distributed computing environments created new requirements for privacy-preserving collaborative security. Federated learning emerged as a promising solution by enabling collaborative model training across decentralized clients without sharing raw data16,17. However, early federated approaches for intrusion detection faced critical limitations when using traditional deep learning methods like LSTM, CNN, and standard neural networks, as these architectures fundamentally cannot capture network structural patterns for they are not designed to model graph topology and device relationships18,19. These methods process sequential data or grid-like structures but fail to understand how network devices connect to each other, missing the relationship patterns that characterize sophisticated attacks like coordinated scanning and distributed intrusion campaigns. Additionally, heterogeneous data distributions across clients lead to model drift and poor convergence.

Recognizing these structural limitations, recent directions began adopting GNNs in federated settings to better capture network relationships20. Khan et al.’s work demonstrates this trend across multiple domains, including collaborative networks for smart healthcare systems with dynamic behavior aggregation, reinforcement learning-based approaches for Internet of Medical Things networks with dynamic client participation, and federated methods for consumer IoT cyber-attack detection using weighted techniques to address data imbalance21,22,23. Meanwhile, other approaches explored different privacy-preserving techniques: differential privacy methods add noise to protect sensitive information but typically degrade detection performance18,24, while secure multi-party computation approaches guarantee strong privacy but impose high computational overhead that becomes prohibitive for real-time detection25,26. Despite these advances, GNN-based federated approaches revealed additional critical limitations beyond their traditional counterparts. While GNNs can initially capture structural patterns within individual client networks, these structural patterns are lost during parameter aggregation. Consequently, the client structural knowledge gets mixed together through federated averaging at the server level. Furthermore, temporal attack patterns are also destroyed during this parameter sharing process27. When only model parameters are exchanged between clients, the time-dependent characteristics essential for detecting attacks like DDoS campaigns and coordinated scanning operations are lost, resulting in poor performance against the most threatening attack types28,29.

This dual limitation creates a fundamental research gap where existing federated intrusion detection approaches cannot simultaneously preserve both structural relationships and temporal attack evolution while maintaining meaningful privacy guarantees. Traditional federated methods cannot capture structural patterns due to architectural limitations, GNN federated methods lose both structural and temporal patterns during parameter aggregation, while privacy-preserving techniques either degrade detection performance through noise injection or impose prohibitive computational costs.To address these limitations, we propose FedGATSage, a hybrid community-based federated learning architecture that integrates client-side GAT with server-side GraphSAGE through community abstraction. Rather than sharing raw network data or just model parameters, each client detects communities (groups of densely connected devices with sparse connections to other groups) using GAT and the Louvain algorithm30, then shares only these community-level representations with the server, which constructs an overlay graph and learns global patterns using GraphSAGE. This approach preserves both structural and temporal attack patterns by maintaining the network relationship information through community embeddings while capturing attack evolution through specialized feature extraction, all without exposing individual device behaviors. Our solution is based on the strong correlation between community structure and attack patterns in datasets such as the NF-ToN-IoT and CIC-ToN-IoT datasets31,32. These datasets contain diverse attack types including both structural attacks (Backdoor, Injection) and temporal attacks (DDoS, DoS, Scanning), making them ideal for comprehensive evaluation33. Unlike existing federated approaches that focus primarily on parameter aggregation, FedGATSage simultaneously preserves privacy, maintains structural and temporal patterns, and enables specialized detection for different attack categories34,35.

The main contributions of this paper include: (1) A hybrid federated learning architecture combining client-side GAT with server-side GraphSAGE that addresses both structural and temporal pattern preservation limitations in federated intrusion detection; (2) Specialized GAT detector variants (Temporal, Content, Behavioral) with sequential training and ensemble fusion, enabling attack-type-aware detection in federated environments; (3) An enhanced federated learning method that weights client contributions based on their performance and handles different network conditions rather than standard approaches, and (4) A community abstraction technique that protects privacy by analyzing device groups rather than exposing individual device data for attack detection.

Methods

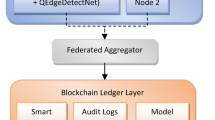

FedGATSage is presented as a federated learning solution for privacy-preserving network intrusion detection that integrates Graph Attention Networks (GAT) on the client side with GraphSAGE on the server side through community abstraction. This approach addresses the challenge of maintaining detection accuracy while preserving both structural and temporal attack patterns in distributed environments like IoT networks.

System architecture overview

Overview of the FedGATSage architecture. Network data is processed locally by clients into graphs, where communities (colored node groups) are detected and processed using GAT. Clients send community embeddings to the server, which applies GraphSAGE to generate global embeddings. Updated model parameters are then sent back to clients.

As illustrated in Fig. 1, the workflow begins with each client transforming its local network data into a graph, where nodes represent devices (IP addresses) and edges represent network connections. Each client applies a GAT model to its graph, then detects communities using the Louvain algorithm30. Communities are groups of densely connected nodes with sparse connections to other groups. Node embeddings are then aggregated into community-level representations that capture structural information while abstracting individual details.

Only these community embeddings and client-side model parameters are transmitted to the server. The server aggregates information from all clients and constructs a community-based overlay graph, where each community becomes a node and edges reflect similarity between communities. GraphSAGE is then applied to this overlay graph to capture global patterns, after which updated parameters are redistributed to clients. The federated process begins with random initialization of both GAT (client-side) and GraphSAGE (server-side). In each round, clients train locally, generate community embeddings, and send them with model parameters to the server. The server updates the global GraphSAGE model on the overlay graph, aggregates parameters, and shares them back with clients.

FedGATSage provides three key methodological advantages over existing approaches: temporal pattern preservation through flow-level abstraction maintains attack sequences essential for detecting coordinated threats, community-aware privacy preserves network relationships while protecting device identities, and specialized architecture uses three GAT variants for different attack types providing targeted detection capabilities.

Client-side processing

Client-side processing begins with converting network flow data into graph format, with network devices as nodes and network connections as edges. We extract features for each node, including traffic statistics (packet count, connection frequency), centrality measures (PageRank, degree centrality), and protocol-specific information. These features are enhanced through specialized engineering tailored to different attack types.

To model diverse attack patterns effectively, we implement three specialized GAT variants as illustrated in Fig. 2. Each variant targets different categories of network attacks:

Temporal GAT focuses on time-dependent attacks like DDoS and DoS by analyzing timing patterns, traffic bursts, and connection sequences that characterize coordinated attacks.

Content GAT targets content-based attacks like injection and XSS by examining payload characteristics, protocol usage patterns, and service targeting behaviors.

Behavioral GAT detects behavioral attacks like password attacks, backdoors, and scanning by analyzing connection behaviors, port usage patterns, and session characteristics.

Each GAT variant processes the network graph and generates node embeddings that capture attack-specific characteristics. These embeddings are combined through weighted aggregation that emphasizes the most relevant features for each nod. Moreover, the architecture of each variant consists of multiple graph attention layers with specialized attention mechanisms, gradient propagation with residual connections, and normalization layers for stable training. The general attention mechanism is expressed as:

where \(h_i^{\prime }\) is the updated representation of node i, \(\sigma\) is a non-linear activation function, \(\textbf{W}\) is a learnable weight matrix, and \(\alpha _{ij}\) are attention coefficients that determine the importance of neighbor j’s features to node i. These attention coefficients are calculated differently for each variant to prioritize relevant features for specific attack types.

The three specialized GAT variants are trained sequentially rather than jointly, allowing each detector to optimize independently for its specific attack category. Temporal GAT trains on features focusing on flow rates, duration patterns, and flag sequences; Content GAT trains on content-specific features emphasizing payload sizes, protocol patterns, and service targeting; Behavioral GAT trains on connection pattern features analyzing port usage, timing behaviors, and session characteristics.

After generating node embeddings using the specialized GAT variants, we perform community detection and embedding creation to transform these embeddings into privacy-preserving representations suitable for federated learning. Algorithm 1 details this process.

Algorithm 1 systematically transforms raw network data into privacy-preserving embeddings through six sequential steps: First, we construct a graph structure where each distinct IP address becomes a node and each network flow becomes an edge connecting source and destination IPs, while extracting basic traffic statistics and centrality measures for each device. Second, we apply the Louvain algorithm to identify communities (groups of densely connected devices) and compute community importance scores that measure how much removing each device would disrupt the community structure. Third, we use the specialized GAT variants to generate rich node embeddings that capture each device’s role in the network and its relevance to different attack types. Fourth, we create flow embeddings by combining information from both communication endpoints (source and destination nodes of each flow) using concatenation, element-wise multiplication, and absolute difference operations along with original traffic features. Fifth, we aggregate node embeddings within each community using weighted averaging and add structural metrics like internal density and clustering coefficients. Finally, we select representative flows from each attack class rather than transmitting all data, ensuring computational efficiency and additional privacy protection.

During inference, predictions from all three detectors are combined through a two-stage fusion process. We apply ensemble averaging across the three detector outputs, then employ a Random Forest classifier trained on features including raw probabilities from each detector, predicted class labels, confidence scores, and attack-type priority weights. The Random Forest learns optimal weighting strategies during training, automatically emphasizing the most relevant specialized detector for each attack instance.

Server-side processing

Upon receiving community embeddings from clients, the server constructs an overlay graph where each node represents a community from any client. The first step is determining appropriate connections between communities through similarity analysis using cosine similarity:

where \(C_i\) and \(C_j\) are the embedding vectors of communities i and j respectively. Edges in the overlay graph are created between communities whose similarity exceeds a dynamically adjusted threshold that begins at 0.7 and is progressively lowered if necessary to ensure each community has at least three connections, while not dropping below 0.3 to maintain edge quality.

The complete overlay graph construction process follows these steps:

Once the overlay graph is constructed (as illustrated in Algorithm 2) GraphSAGE is applied to learn global patterns across all client communities. GraphSAGE employs neighborhood sampling and aggregation to efficiently process the overlay graph structure:

where \(h_v^{(k)}\) is the embedding of node v at layer k, and \(\mathscr {N}(v)\) represents its neighborhood. The AGGREGATE function combines information from neighboring nodes through a mean aggregator function, enabling the model to learn patterns that span multiple communities across different clients.

Federated model aggregation and parameter redistribution

After processing the overlay graph with GraphSAGE, the server performs federated model aggregation by averaging client-side GAT model parameters with adaptive weighting based on client performance. For each client k, a weight \(w_k\) is computed as:

where \(A_k\) is the client’s local validation accuracy, \(A_{\min }\) and \(A_{\max }\) are the minimum and maximum accuracies across all clients, and \(\alpha =0.2\) is a base weight ensuring all clients contribute meaningfully. This approach addresses client heterogeneity by giving more influence to clients with better performance while ensuring all clients still contribute to the global model. The aggregated parameters are then distributed to all clients for the next federation round. For final classification decisions, each client applies its updated GAT model to local data, and predictions are made based on the edge features between nodes in the network graph. This approach enables global pattern learning while maintaining the privacy of local network data.

Results

A comprehensive evaluation of FedGATSage is presented on both the NF-ToN-IoT and CIC-ToN-IoT datasets, examining performance across different attack types, architectural configurations, and computational efficiency metrics. This evaluation focuses on comparing the proposed approach with both centralized deep learning models and alternative federated learning techniques to establish its effectiveness in balancing privacy preservation with detection capability.

Overall performance comparison

FedGATSage achieved 78.58% balanced accuracy on the NF-ToN-IoT dataset and 80.24% balanced accuracy on CIC-ToN-IoT dataset with better false negative rates (0.2234 on NF-ToN-IoT and 0.1976 on CIC-ToN-IoT) than the federated LSTM approach (0.2862 on NF-ToN-IoT and 0.2250 on CIC-ToN-IoT) indicating fewer missed attacks while maintaining reasonable false positive rates, approaching the performance of centralized models while preserving privacy. The performance gap between the federated FedGATSage approach and centralized models is remarkably small (around 3%), while maintaining strong privacy guarantees through community abstraction. Compared to state-of-the-art federated learning baselines, FedGATSage demonstrates superior performance: federated LSTM achieves 71.38% balanced accuracy versus our 78.58%, representing 7.2 percentage point improvement. More critically, our approach maintains temporal attack detection capability (DDoS F1: 0.67, DoS F1: 0.56) where existing federated methods show severe degradation in these challenging attack categories. Table 1 presents detailed performance metrics across both centralized and federated approaches for both datasets.

Attack-specific detection capabilities

FedGATSage demonstrates varying effectiveness across different types of attacks in a federated environment that preserves privacy, as shown in Fig. 3 that shows the evaluation scores for each type of attack on the NF-ToN-IoT dataset as an example.

The highest performance is observed on structural attacks, with F1 scores reaching 0.9942 and 0.9965 on Benign traffic, and 0.9750 and 0.9690 for Backdoor attacks on NF-ToN-IoT and CIC-ToN-IoT, respectively. These results indicate very few false positives or false negatives for these categories. For temporal attacks, which are typically difficult to detect in federated environments, promising detection capabilities are demonstrated. DDoS attacks achieve F1 scores of 0.6354 and 0.6672, and DoS attacks reach 0.5721 and 0.5608 on NF-ToN-IoT. This represents a significant improvement over prior federated approaches, which often failed entirely to detect such attacks. A detailed comparison of per-class performance across the NF-ToN-IoT datasets, including precision, recall, F1 score, and false negative rates is show in Table 2,

The results highlight interesting patterns in precision, recall, false positives/negatives across attack types for both NF-ToN-IoT and CIC-ToN-IoT datasets. Benign traffic and Backdoor attacks exhibit high precision and recall, effectively identifying true positives while minimizing both false positives and false negatives (FNR: 0.0215 and 0.0000 for CIC-ToN-IoT, and 0.0056 and 0.0058 for NF-ToN-IoT). DDoS attacks show high precision (0.8939) but moderate recall (0.5322), indicating strong true positive identification with some missed detections. DoS and XSS attacks have near-perfect recall (1.00 and 0.6612, respectively), but lower precision, ensuring almost no false negatives (FNR: 0.0000 and 0.3388 for CIC-ToN-IoT, and 0.0000 and 0.0010 for NF-ToN-IoT), which is valuable in security contexts. For attacks like DoS and Scanning, high recall values (1.000 and 0.9302 for CIC-ToN-IoT, 0.987 and 0.8029 for NF-ToN-IoT) with moderate precision (0.3896 and 0.7634 for CIC-ToN-IoT, 0.3896 and 0.1050 for NF-ToN-IoT) represent a design that prioritizes capturing true positives over avoiding false alarms. The confusion matrix in Fig. 4 provides insights into classification patterns and misclassifications across attack categories.

Architectural configuration analysis

Different architectural configurations were evaluated to determine the optimal placement of GNN variants in the federated setup. Table 3 shows the comprehensive performance and computational requirements of different configurations, including centralized and federated approaches.

Convergence analysis on the NF-ToN-IoT dataset showing accuracy progression over federation rounds for different architectural configurations. The GAT locally with GraphSAGE globally configuration demonstrates faster convergence and superior final performance compared to alternative setups. Similar results on the CiC-ToN-IoT dataset were observed.

The GAT locally with GraphSAGE globally configuration achieved the highest balanced accuracy (78.58% and 80.24% for NF-ToN-IoT and CIC-ToN-IoT) compared to alternative configurations. This configuration required less training time compared to the reversed configuration (GAT globally with GraphSAGE locally) for both datasets. Data transfer measurements showed approximately 10% lower volume (3.8 MB/round vs. 4.2 MB/round) for the GAT local configuration compared to the alternative, due to more efficient client-side processing and reduced parameter sizes in community embedding transfers.

For computational resources, the GAT locally with GraphSAGE globally configuration required an average of 2.4GB RAM and 35% GPU utilization during client-side processing for NF-ToN-IoT, while for CIC-ToN-IoT, it required 3.8GB RAM and 55% GPU utilization at the client side. CPU-only deployments showed the primary configuration requiring 76% less computation time than alternatives for NF-ToN-IoT, while for CIC-ToN-IoT, the primary FedGATSage configuration required slightly more total training time (7.5 hours vs. 5.5 hours for centralized GAT) but showed 12% faster training time compared to the LSTM in federated setting for CIC-ToN-IoT and approximately 27% reduction in data transfer volume when compared to GAT globally with GraphSAGE locally for NF-ToN-IoT.

GAT locally with GraphSAGE globally configuration achieved the highest final performance and required approximately 25–30% fewer federation rounds to reach performance plateaus compared to alternative setups. This trend was consistent across multiple runs and demonstrates the efficiency of this configuration in federated environments. Furthermore, experiments revealed significant heterogeneity across clients, with network sizes varying by up to 40% and attack distributions showing up to 25% variation in class prevalence. The adaptive weighting approach effectively addresses this heterogeneity, reducing the performance gap between the best and worst performing clients from 12% to just 5%. Additionally, clients with more balanced attack distributions received weights 1.8\(\times\) higher on average than those with skewed distributions, prioritizing more representative data. As shown in Fig. 5, which illustrates the convergence behavior on the NF-ToN-IoT dataset.

Specialized detector performance

As shown in Fig. 6, each GAT variant achieves optimal recall on its targeted attack types on the NF-ToN-IoT dataset, the Temporal GAT achieved perfect recall (1.0) for DoS attacks, the Content GAT demonstrated near-perfect recall (0.999) for XSS attacks, and the Behavioral GAT achieved excellent recall (0.994) for Backdoor attacks. Similar trends were observed for the CIC-ToN-IoT dataset, with each detector variant consistently capturing the majority of its specialized attack types. These high recall values highlight the detectors’ ability to identify virtually all instances of their respective attack classes–an essential requirement in operational security settings where undetected threats can have critical implications.

Comparative performance evaluations show that the specialized detector approach consistently outperforms a single generalized detector. On NF-ToN-IoT, the specialized architecture yielded a 12.5% improvement in balanced accuracy and a 14.2% increase in macro F1 score. On CIC-ToN-IoT, the improvements were similarly pronounced, with a 10.8% gain in balanced accuracy and a 12.6% rise in macro F1, further validating the benefit of tailoring architectures to attack characteristics.

Privacy-performance balance and computational efficiency

FedGATSage achieves a strong balance between privacy preservation and detection performance while maintaining computational efficiency across distributed environments. The approach ensures that raw network data never leaves client networks, with individual device identities abstracted through community aggregation, while achieving 78.58% balanced accuracy on NF-ToN-IoT and 80.24% on CIC-ToN-IoT with only a 2.8% gap compared to centralized models.

The computational efficiency analysis reveals our three-fold optimization strategy designed for practical IoT deployment. Time complexity analysis shows the computational cost per training round: client-side GAT processing requires \(O(|V| \cdot d \cdot h + |E| \cdot d \cdot h)\) operations per layer, where |V| is the number of unique IP addresses in the network, |E| is the number of network flows between devices, d is the feature dimension (typically 256), and h is the hidden layer dimension. Community detection using the Louvain algorithm requires \(O(|E| \log |V|)\) operations to identify device clusters, while server-side GraphSAGE processing requires \(O(k \cdot |F| \cdot d)\) operations where k is the neighborhood sampling size and |F| represents the number of flow embeddings after community abstraction (significantly smaller than |V|).

Space complexity analysis demonstrates memory efficiency essential for resource-constrained IoT devices. Each client stores node embeddings requiring \(O(|V| \cdot d)\) memory space (one embedding per IP address), while model parameters require \(O(L \cdot d^2)\) space where L is the number of neural network layers. The server maintains flow embeddings requiring \(O(|C| \cdot |F| \cdot d)\) memory where |C| is the number of participating clients.

Communication complexity analysis quantifies bandwidth requirements critical for IoT networks. Our approach requires transmitting \(O(|F| \cdot d)\) data per client due to community abstraction, resulting in an 85% reduction in communication overhead–from approximately 25KB to 3.2KB per client in typical networks with 100 IP addresses, where 5-7 communities effectively represent the entire network structure.

The scientific foundation for this favorable privacy-performance tradeoff is demonstrated through strong correlation patterns between attack types across communities (Fig. 7), with a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.87 (p-value: 2.39e-16). This correlation provides scientific justification for the community abstraction approach and explains why effective pattern detection is maintained while ensuring privacy.

Experimental setup

FedGATSage was evaluated on the NF-ToN-IoT and CIC-ToN-IoT datasets, covering structural, content-based, and temporal attacks. The dataset was partitioned across five simulated clients with balanced attack distributions and network heterogeneity. Client sizes varied by up to 40% and class prevalence varied by 25%. Clients processed data locally and shared community embeddings for global training. Client performance across training rounds is shown in Fig. 8.

The implementation used PyTorch 1.8.0 and PyTorch Geometric 2.0.1, with training on NVIDIA GPUs and CPU-only deployment tested. GAT models used 256 hidden dimensions, 8 attention heads, and 0.2 dropout; GraphSAGE used 256 hidden dimensions with 2-layer neighborhood sampling. Evaluation included centralized GAT, GraphSAGE, FedLSTM, a basic federated GNN, and a FedGATSage variant (GAT global, GraphSAGE local). Metrics included accuracy, balanced accuracy, macro F1 score, and computational efficiency measures.

Discussion

FedGATSage addresses the dual limitation we identified in existing federated intrusion detection approaches: traditional federated methods lose structural patterns due to architectural constraints, while GNN federated methods lose temporal patterns during parameter aggregation. Our results demonstrate that this dual-solution approach achieves near-centralized performance for network intrusion detection while preserving privacy, with a performance gap of only 2.8%. This success stems from our specialized detector architecture and community-based abstraction mechanism working collaboratively to address both architectural and aggregation challenges, validating our hypothesis that flow-level abstraction with community enhancement can maintain detection effectiveness without compromising privacy guarantees.

The architectural design choices are theoretically grounded in addressing both limitation types through complementary GNN strengths in federated environments. GAT’s selection for client-side processing addresses the architectural limitation by providing attention mechanisms that can dynamically weight neighbor importance, which is crucial for intrusion detection where malicious connections may represent only a small fraction of total network traffic. This adaptive weighting is essential for detecting attacks that exploit trust relationships within local network communities, where the significance of specific connections cannot be predetermined. Conversely, GraphSAGE’s selection for server-side processing addresses the aggregation limitation by leveraging its inductive learning capability and sampling efficiency, enabling efficient processing of dynamic overlay graphs where community embeddings from different clients create variable graph structures across federation rounds. This combination addresses the federated learning challenge of balancing local detail with global generalization, where GAT preserves local attack patterns while GraphSAGE efficiently aggregates them across the federation without destroying temporal signatures.

The community abstraction approach provides the scientific foundation for preserving both structural and temporal patterns simultaneously. Our analysis reveals a strong correlation between structural similarity and attack pattern similarity across communities, with a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.87 (p-value: 2.39e-16). This statistical relationship explains why our approach maintains detection effectiveness even when using abstracted community-level representations rather than detailed node-level data, addressing both privacy concerns and pattern preservation requirements. Communities with similar structural features tend to experience similar types of attacks because network topology reflects organizational structure, device roles, and vulnerability patterns that attackers naturally target, enabling effective temporal pattern detection across different network domains.

The computational complexity analysis reveals the practical feasibility of our dual-solution approach for real-world IoT deployment. The three-fold optimization strategy spanning time, space, and communication complexity demonstrates that FedGATSage maintains computational efficiency while addressing both architectural and aggregation limitations. This efficiency directly translates to practical deployment advantages, where convergence analysis shows that GAT-local with GraphSAGE-global configuration requires 25-30% fewer federation rounds compared to alternative arrangements. The 85% reduction in communication overhead makes it particularly suitable for bandwidth-constrained IoT environments where traditional federated learning approaches would be impractical due to excessive data transfer requirements. Furthermore, implementing specialized GAT variants for different attack types enables balanced detection capabilities across structural attacks (Backdoor, Injection) and temporal attacks (DDoS, DoS), a capability that neither traditional federated approaches nor existing GNN federated methods can achieve.

Comparison with State-of-the-Art Approaches: Our results demonstrate competitive performance compared to recent federated learning approaches for IoT intrusion detection while addressing fundamental limitations that existing methods do not solve. Recent approaches such as the optimal federated learning-based IDS achieve 95.59% accuracy on binary classification tasks using MQTT datasets36, while Tab Transformer-based federated frameworks report 98.80% accuracy on multiclass scenarios using CICIoT202337. AutoEncoder-based federated learning approaches achieve 90.93% accuracy on device-specific scenarios using N-BaIoT datasets38, and group-based federated learning methods demonstrate comparable accuracy for anomaly detection in smart home environments39. However, these approaches face the same dual limitations we identified: traditional approaches suffer from architectural constraints that prevent structural pattern capture, while GNN approaches suffer from temporal pattern destruction during parameter averaging, making them ineffective against coordinated attacks. Our specialized GAT detector variants achieve perfect recall for DoS attacks and near-perfect recall for XSS attacks through targeted architectures that preserve both structural and temporal characteristics, representing the first federated approach to successfully address both limitation types simultaneously.

However, several limitations warrant consideration for practical deployment. While FedGATSage excels at addressing both structural and temporal pattern preservation challenges, some attack types like scanning still present opportunities for enhancement, with F1-scores below 0.20. The performance variations across attack types highlight that certain attacks like DoS and XSS exhibit higher false positive rates, which may require post-processing mechanisms in critical environments. Additionally, our evaluation was conducted on static datasets, whereas real-world IoT networks are dynamic and may require sliding-window approaches for continuous adaptation to evolving threat landscapes. These limitations suggest promising research directions including adaptive community detection algorithms that dynamically adjust to changing network activities, more sophisticated overlay graph construction methods to better capture relationships between communities across heterogeneous clients, integration with complementary privacy-preserving techniques for additional security guarantees, and exploring dynamic community boundaries for better adaptation to evolving attack patterns.

Conclusion

FedGATSage represents the first federated learning approach to successfully solve both architectural and aggregation limitations that have prevented effective intrusion detection in distributed environments. By systematically addressing the dual challenge where traditional federated methods cannot capture structural patterns and GNN federated methods lose temporal patterns, our work establishes a new paradigm for privacy-preserving collaborative security that maintains detection effectiveness against sophisticated coordinated attacks.

The technical contributions advance the field through four key innovations that address fundamental limitations in federated intrusion detection. First, our hybrid federated learning architecture that strategically combines client-side GAT with server-side GraphSAGE addresses both architectural and aggregation limitations, where GAT captures local structural patterns while GraphSAGE efficiently processes global patterns without destroying temporal signatures Second, specialized GAT detector variants with ensemble fusion provide the architectural capability to capture structural patterns that traditional federated approaches fundamentally cannot model, while enabling attack-type-aware detection in federated environments. Third, our custom federated aggregation mechanism with performance-weighted averaging addresses client heterogeneity while maintaining both structural and temporal pattern preservation. Fourth, community-enhanced feature engineering enables privacy-preserving structural pattern learning across distributed networks while achieving substantial communication overhead reduction. The practical impact extends beyond performance metrics to provide the first federated solution capable of detecting sophisticated coordinated attacks that require both structural relationship understanding and temporal sequence preservation. Our community abstraction mechanism achieves an 85% reduction in communication overhead compared to node-level sharing, directly addressing the bandwidth constraints that make traditional federated learning impractical for IoT environments, while successful detection of challenging temporal attacks like DDoS campaigns addresses critical security gaps where existing federated methods fundamentally fail due to their individual limitation types. The strong correlation between community structure and attack patterns provides scientific justification for why our dual-solution approach maintains effectiveness while ensuring privacy, enabling favorable privacy-performance tradeoffs that neither traditional nor GNN federated approaches can achieve alone.

Future research directions include extending the approach to dynamic community detection for evolving networks, incorporating additional attack categories that may benefit from the dual-solution framework, and exploring integration with complementary privacy-preserving techniques for enhanced security guarantees. The successful demonstration of near-centralized performance in federated settings while maintaining privacy through systematic solution of both architectural and aggregation limitations opens new possibilities for collaborative security in distributed IoT ecosystems, particularly for organizations requiring both regulatory compliance and effective threat detection against sophisticated coordinated attacks that span multiple network domains.

Data availability

The datasets used in this study are publicly available at https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/dhoogla/nftoniot (NF-ToN-IoT) and https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/dhoogla/cictoniot (CIC-ToN-IoT). No new data were generated in this research.

Code availability

Source code is available at: https://github.com/Fouad-AlTfaily/Fed_GNN.git.

References

Anthi, E., Williams, L., Slowinska, M., Theodorakopoulos, G. & Burnap, P. A supervised intrusion detection system for smart home iot devices. IEEE Internet Things J. 6, 9042–9053. https://doi.org/10.1109/JIOT.2019.2926365 (2019).

Koroniotis, N., Moustafa, N., Sitnikova, E. & Turnbull, B. Towards the development of realistic botnet dataset in the internet of things for network forensic analytics: Bot-iot dataset. Futur. Gener. Comput. Syst. 100, 779–796. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.future.2019.05.041 (2019).

Tyagi, K., Ahlawat, A. & Chaudhary, H. Iot network security: Netflow traffic analysis and attack classification using machine learning techniques. In 2024 11th International Conference on Reliability, Infocom Technologies and Optimization, 1–8, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICRITO61523.2024.10522466 (2024).

Hwang, R.-H., Peng, M.-C., Huang, C.-W., Lin, P.-C. & Nguyen, V.-L. An unsupervised deep learning model for early network traffic anomaly detection. IEEE Access 8, 30387–30399. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2973023 (2020).

Cortes, C. & Vapnik, V. Support-vector networks. Mach. Learn. 20, 273–297 (1995).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32 (2001).

Termos, M. et al. Gdlc: A new graph deep learning framework based on centrality measures for intrusion detection in iot networks. Internet of Things 26, 101214 (2024).

Termos, M. et al. Intrusion detection system for iot based on complex networks and machine learning. In 2023 IEEE Intl Conf on Dependable, Autonomic and Secure Computing, Intl Conf on Pervasive Intelligence and Computing, Intl Conf on Cloud and Big Data Computing, Intl Conf on Cyber Science and Technology Congress (DASC/PiCom/CBDCom/CyberSciTech) 0471–0477 (IEEE, 2023).

Termos, M. et al. Enhancing iot network intrusion detection with a new graphsage embedding algorithm using centrality measures. In 10th International Conference on Internet of Things, Big Data and Security (2025).

Wu, Z. et al. A comprehensive survey on graph neural networks. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 32, 4–24. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNNLS.2020.2978386 (2021).

Zhou, J. et al. Graph neural networks: A review of methods and applications. AI Open 1, 57–81 (2020).

Velickovic, P. et al. Graph attention networks. International Conference on Learning Representations (2018).

Hamilton, W. L., Ying, R. & Leskovec, J. Inductive representation learning on large graphs. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst.30 (2017).

Liu, Z. et al. Heterogeneous graph neural networks for malicious account detection. In: Proc. 27th ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, 2077–2085 (2018).

Liu, X. et al. Graph neural networks with adaptive residual. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 34, 9720–9733 (2021).

Kairouz, P. et al. Advances and open problems in federated learning. Found. Trends Mach. Learn. 14, 1–210. https://doi.org/10.1561/2200000083 (2021).

Arbaoui, M., Brahmia, M.-E.-A., Rahmoun, A. & Zghal, M. Federated learning survey: A multi-level taxonomy of aggregation techniques, experimental insights, and future frontiers. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 15, 1–69. https://doi.org/10.1145/3678182 (2024).

Wei, K. et al. Federated learning with differential privacy: Algorithms and performance analysis. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 15, 3454–3469. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIFS.2020.2988575 (2020).

Zhao, Y. et al. Federated learning with non-iid data. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1806.00582 (2018).

Termos, M. et al. Integrating centrality measures in federated learning-based intrusion detection systems. In 2025 IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference (WCNC) 1–6 (IEEE, 2025).

Khan, I. A. et al. A novel collaborative sru network with dynamic behaviour aggregation, reduced communication overhead and explainable features. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 28, 3228–3235. https://doi.org/10.1109/JBHI.2024.3352013 (2024).

Khan, I. A. et al. Fed-inforce-fusion: A federated reinforcement-based fusion model for security and privacy protection of iomt networks against cyber-attacks. Information Fusion 101, 102002. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inffus.2023.102002 (2024).

Khan, I. A., Pi, D., Kamal, S., Alsuhaibani, M. & Alshammari, B. M. Federated-boosting: A distributed and dynamic boosting-powered cyber-attack detection scheme for security and privacy of consumer iot. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 71, 6340–6347. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCE.2024.3499942 (2025).

Dwork, C., McSherry, F., Nissim, K. & Smith, A. Calibrating noise to sensitivity in private data analysis. In Theory Cryptogr. Conf. 265–284 (Springer, 2006).

Goldreich, O. Secure multi-party computation. Manuscript. Preliminary version 78, 1–108 (1998).

Truex, S. et al. A hybrid approach to privacy-preserving federated learning. In: Proc. 12th ACM Workshop on Artificial Intelligence and Security, 1–11, https://doi.org/10.1145/3338501.3357370 (2019).

Chen, F., Li, P., Miyazaki, T. & Wu, C. Fedgraph: Federated graph learning with intelligent sampling. IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst. 33, 1775–1786. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPDS.2021.3125565 (2022).

Wu, C., Wu, F., Cao, Y., Huang, Y. & Xie, X. Fedgnn: Federated graph neural network for privacy-preserving recommendation. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2102.04925 (2021).

Liu, R. et al. Federated graph neural networks: Overview, techniques, and challenges. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 36, 4279–4295. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNNLS.2024.3360429 (2025).

Blondel, V. D., Guillaume, J.-L., Lambiotte, R. & Lefebvre, E. Fast unfolding of communities in large networks. J. Stat. Mech. Theory Exp. 2008, P10008. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-5468/2008/10/P10008 (2008).

Ghalmane, Z., Cherifi, C., Cherifi, H. & El Hassouni, M. Centrality in complex networks with overlapping community structure. Sci. Rep. 9, 10133. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-46507-y (2019).

Ghalmane, Z. et al. Extracting backbones in weighted modular complex networks. Sci. Rep. 10, 15539 (2020).

Al Tfaily, F. et al. Generating realistic cyber security datasets for iot networks with diverse complex network properties. In 10th International Conference on Internet of Things, Big Data and Security 321–328 (SCITEPRESS-Science and Technology Publications, 2025).

Wu, C. et al. Fedgnn: Federated graph neural network for privacy-preserving recommendation. arXiv:2102.04925 (2021).

Shao, Y. et al. Distributed graph neural network training: A survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 56, 1–39 (2024).

Karunamurthy, A., Vijayan, K., Kshirsagar, P. R. & Tan, K. T. An optimal federated learning-based intrusion detection for iot environment. Sci. Rep. 15, 8696. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-93501-8 (2025).

Abd Elaziz, M., Fares, I. A., Dahou, A. & Shrahili, M. Federated learning framework for iot intrusion detection using tab transformer and nature-inspired hyperparameter optimization. Front. Big Data 8, 1526480. https://doi.org/10.3389/fdata.2025.1526480 (2025).

Olanrewaju-George, B. & Pranggono, B. Federated learning-based intrusion detection system for the internet of things using unsupervised and supervised deep learning models. Cyber Secur. Appl. 3, 100068. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csa.2024.100068 (2025).

Zhang, Y. et al. Privacy-aware anomaly detection in iot environments using fedgroup: A group-based federated learning approach. J. Netw. Syst. Manage. 32, 20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10922-023-09782-9 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by Ektidar, a Lebanese project aimed at empowering youth, and CESI EAST Region.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.T.: Writing - original draft, Visualization, Validation, Software, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Z.G., M.B., H.H.: Writing - review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. A.J., M.Z.: Writing - review & editing, Validation, Supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Al Tfaily, F., Ghalmane, Z., Brahmia, M.e.A. et al. Graph-based federated learning approach for intrusion detection in IoT networks. Sci Rep 15, 41264 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25175-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25175-1